Optimizing PLS Components for Robust 3D-QSAR Model Validation in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Partial Least Squares (PLS) components to enhance the predictive power and reliability of 3D-QSAR models.

Optimizing PLS Components for Robust 3D-QSAR Model Validation in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Partial Least Squares (PLS) components to enhance the predictive power and reliability of 3D-QSAR models. It covers the foundational role of PLS regression in correlating 3D molecular descriptors with biological activity, detailed methodologies for model construction and component number determination, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls and improving model performance, and rigorous internal and external validation techniques based on established statistical criteria. By synthesizing best practices and recent advancements, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to build more trustworthy and actionable QSAR models, thereby accelerating rational drug design.

The Core Principles: Understanding PLS Regression in 3D-QSAR

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression serves as a critical computational tool in chemometrics and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) studies, particularly when analyzing high-dimensional 3D molecular descriptors. This technical guide explores the theoretical foundation of PLS regression and its practical application in handling correlated descriptor matrices common in 3D-QSAR modeling. Through troubleshooting guides and FAQs, we address specific experimental challenges researchers face during model development, component optimization, and validation procedures. The content is framed within the broader thesis of optimizing PLS components to enhance predictive accuracy and interpretability in 3D-QSAR model validation research, providing drug development professionals with practical methodologies for robust model construction.

Technical Foundations: PLS Regression and 3D Molecular Descriptors

Understanding PLS Regression

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression represents a dimensionality reduction technique that addresses critical limitations of ordinary least squares regression, particularly when analyzing high-dimensional data with multicollinear predictors. Developed primarily in the early 1980s by Scandinavian chemometricians Svante Wold and Harald Martens, PLS has become particularly valuable in chemometrics for handling datasets where the number of descriptors exceeds the number of compounds or when predictors exhibit strong correlations [1] [2].

The fundamental objective of PLS is to construct new predictor variables, known as latent variables or PLS components, as linear combinations of the original descriptors. Unlike similar approaches such as Principal Component Regression (PCR), which selects components that maximize variance in the predictor space, PLS specifically chooses components that maximize covariance between predictors and the response variable [3]. This characteristic makes PLS particularly suitable for predictive modeling in QSAR studies, as it focuses on components most relevant to biological activity.

The PLS algorithm operates iteratively, extracting one component at a time. For the first component, the algorithm computes covariances between all predictors and the response, normalizes these covariances to create a weight vector, then constructs the component as a linear combination of the original predictors [2]. Subsequent components are built to be orthogonal to previous ones while continuing to explain remaining covariance. This process generates a reduced set of mutually independent latent variables that serve as optimal predictors for the response variable.

Mathematically, the PLS regression model can be represented as: X = ZVᵀ + E (decomposition of predictor matrix) y = Zb + e (response prediction) where Z represents the matrix of PLS components, V contains loadings, b represents regression coefficients for the components, and E and e denote residuals [2].

3D Molecular Descriptors in QSAR

In 3D-QSAR studies, molecular descriptors are derived from the three-dimensional spatial structure of compounds, providing detailed information about stereochemistry and interaction potentials. These descriptors differ fundamentally from traditional 0D-2D descriptors (such as molecular weight or atom counts) by capturing geometrical properties that influence biological activity through steric and electronic interactions [4] [5].

The most common 3D molecular descriptors used in PLS-based QSAR studies include:

- Steric fields: Represent regions of molecular bulk that may create favorable or unfavorable interactions with biological targets, typically calculated using Lennard-Jones potentials [5]

- Electrostatic fields: Map charge distributions and electrostatic potentials around molecules, usually computed via Coulomb potentials [5]

- Hydrophobic fields: Characterize lipophilicity patterns across molecular surfaces

- Hydrogen-bonding fields: Identify potential donor and acceptor sites for hydrogen bonding

These descriptors are typically calculated by placing each aligned molecule within a 3D grid and computing interaction energies with probe atoms at numerous grid points. This process generates an extensive matrix of highly correlated descriptors that far exceeds the number of compounds in typical QSAR datasets, creating an ideal application scenario for PLS regression [5].

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Descriptors in QSAR/QSPR Studies

| Descriptor Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 0D descriptors | Basic molecular properties | Molecular weight, atom counts, bond counts |

| 1D descriptors | Fragment-based properties | HBond acceptors/donors, Crippen descriptors, PSA |

| 2D descriptors | Topological descriptors | Wiener index, Balaban index, connectivity indices |

| 3D descriptors | Geometrical properties | 3D-WHIM, 3D-MoRSE, surface properties, COMFA fields |

| 4D descriptors | 3D coordinates + conformations | JCHEM conformer descriptors, crystal structure-based descriptors |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard 3D-QSAR Workflow with PLS Regression

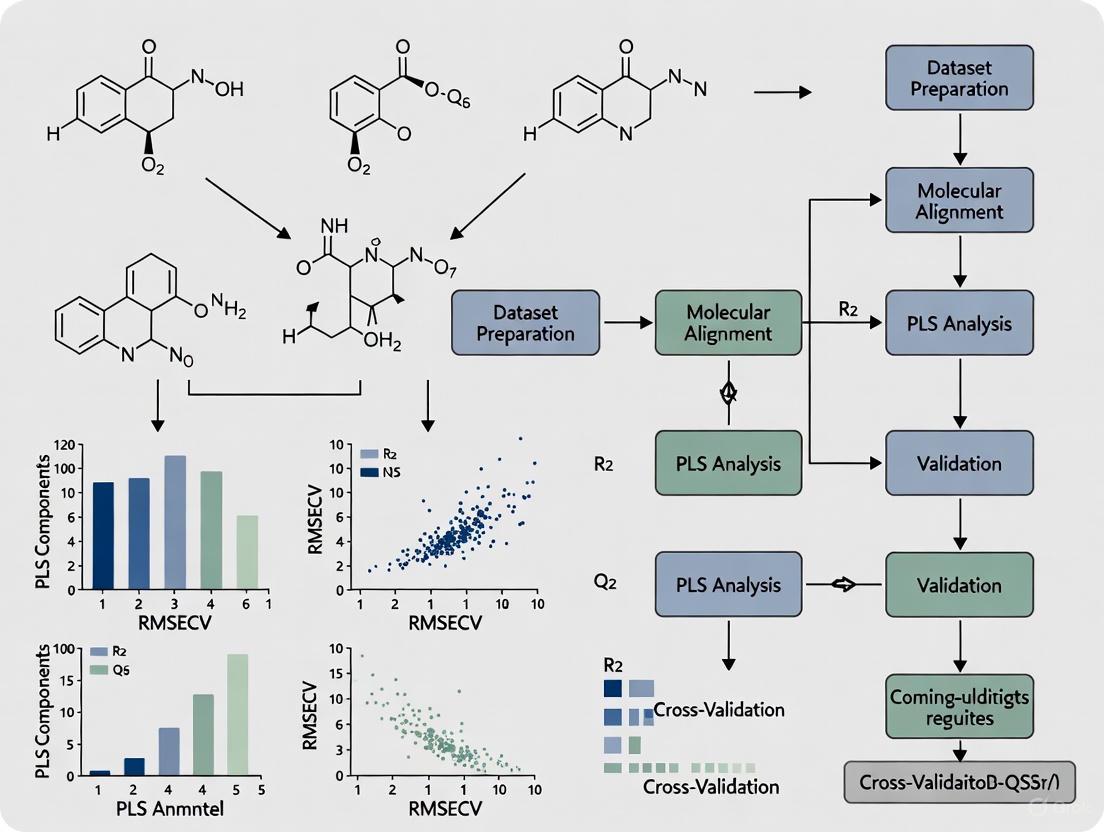

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing 3D-QSAR models using PLS regression, integrating both model building and validation phases:

PLS Component Optimization Procedure

Optimizing the number of PLS components represents a critical step in model development to balance model complexity with predictive power. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach:

Step 1: Data Preprocessing Standardize both predictor and response variables to mean-centered distributions with unit variance. This ensures that variables measured on different scales contribute equally to the model [6].

Step 2: Initial Model Fitting

Fit a PLS model with the maximum number of components (up to the number of predictors). In R, this can be implemented using the plsr() function from the pls package:

Step 3: Cross-Validation Perform k-fold cross-validation (typically 5-10 folds) to evaluate model performance with different numbers of components. Record the Root Mean Squared Error of Prediction (RMSEP) for each component count [6].

Step 4: Optimal Component Selection Identify the number of components that minimizes the cross-validated RMSEP. As shown in Table 2, the optimal balance typically occurs when adding more components does not significantly improve predictive performance.

Step 5: Model Validation Validate the final model with the selected number of components using an external test set not used during model development. Calculate performance metrics including R² (goodness of fit) and Q² (predictive ability) [1] [5].

Table 2: Example Cross-Validation Results for PLS Component Selection

| Number of Components | Test RMSEP | R² (Training) | Q² (Cross-Validation) | Variance Explained in X | Variance Explained in Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40.57 | 0.6866 | 0.7184 | 68.66% | 71.84% |

| 2 | 35.48 | 0.8927 | 0.8174 | 89.27% | 81.74% |

| 3 | 36.22 | 0.9582 | 0.8200 | 95.82% | 82.00% |

| 4 | 36.74 | 0.9794 | 0.8202 | 97.94% | 82.02% |

| 5 | 36.67 | 1.0000 | 0.8203 | 100.00% | 82.03% |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Q1: My PLS model shows excellent fit but poor predictive performance. What might be causing this overfitting and how can I address it?

A: Overfitting typically occurs when the model contains too many components relative to the number of observations or when descriptors with minimal predictive value are included. Implement the following solutions:

- Apply rigorous descriptor selection: Use genetic algorithms for descriptor selection to eliminate irrelevant variables that contribute to noise rather than signal [1]. The genetic algorithm approach implemented in MFTA software can reduce descriptor count by 5-10 fold while maintaining or improving predictivity.

- Optimize component count: Determine the optimal number of PLS components through cross-validation rather than using the maximum possible. The optimal number typically corresponds to the minimum in cross-validated error (Figure 1).

- Increase validation rigor: Replace leave-one-out cross-validation with more robust k-fold cross-validation (k=5-10) or repeated double cross-validation, as LOOCV may overestimate predictivity [1] [7].

Q2: How should I handle highly correlated 3D descriptors in my PLS model?

A: Unlike traditional regression, PLS regression is specifically designed to handle correlated predictors. However, extreme correlation can still cause instability. Consider these approaches:

- Retain correlated descriptors: PLS components are linear combinations of original descriptors, and the method is robust to correlations between them [1] [3].

- Apply variance-based filtering: Remove descriptors with near-zero variance that provide no meaningful information [1].

- Standardize descriptors: Ensure all descriptors are standardized (mean-centered and scaled to unit variance) before model building to prevent dominance by high-variance variables [6].

Q3: What is the difference between Q² and R² in PLS model validation, and which should I prioritize?

A: These metrics serve distinct purposes in model evaluation:

- R² (coefficient of determination): Measures how well the model explains variance in the training data. High R² indicates good fit but does not guarantee predictive power.

- Q² (cross-validated R²): Assesses predictive performance on data not used in model building. Calculated as 1 - (PRESS/SSY), where PRESS is the prediction error sum of squares and SSY is the total sum of squares of Y [1].

Prioritize Q² as the primary metric for model selection, as it better indicates real-world predictive performance. A robust QSAR model should have Q² > 0.5, with values above 0.7 considered excellent [7] [5].

Q4: How can I interpret the contribution of individual molecular descriptors in a PLS model when the model uses latent variables?

A: Although PLS models use latent variables, you can trace back the contribution of original descriptors through several methods:

- Variable Importance in Projection (VIP): Calculate VIP scores that quantify each descriptor's contribution across all components. Descriptors with VIP > 1.0 are generally considered significant [3].

- Regression coefficients: Transform the PLS model back to original descriptor space to obtain standardized regression coefficients that indicate the direction and magnitude of each descriptor's effect [1].

- Contour maps: For 3D-QSAR models, visualize coefficient values spatially to identify regions where specific molecular features (steric bulk, electronegativity) enhance or diminish activity [5].

Q5: What are the common pitfalls in molecular alignment for 3D-QSAR, and how do they affect PLS models?

A: Molecular alignment represents one of the most critical and challenging steps in 3D-QSAR. Common issues include:

- Incorrect bioactive conformation: Using low-energy conformations rather than putative bioactive conformations can misalign key functional groups. Solution: Employ docking studies or pharmacophore modeling to guide conformation selection [5].

- Inconsistent alignment: Slight variations in alignment can dramatically alter descriptor values. Solution: Use robust alignment methods like maximum common substructure (MCS) or field-based alignment [5].

- Diverse binding modes: Assuming identical binding modes for structurally diverse compounds. Solution: For highly diverse datasets, consider alignment-independent descriptors or cluster compounds by suspected binding mode.

Alignment errors manifest in PLS models as poor predictive performance and inconsistent structure-activity relationships, as the mathematical model cannot compensate for fundamental spatial misrepresentation of molecular features.

Advanced Troubleshooting: Optimization of PLS Components

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for optimizing PLS components during model building, addressing the core thesis of component optimization in validation research:

Q6: How do I determine if I need more PLS components in my model?

A: Evaluate these diagnostic indicators:

- Cross-validation metrics: Add components until the cross-validated Q² reaches a plateau or begins to decrease. The optimal number typically occurs at the "elbow" point where additional components provide diminishing returns [1] [6].

- RMSEP plot: Plot Root Mean Squared Error of Prediction against component count. The minimum point indicates the optimal number (see Table 2 for example).

- Variance explanation: Monitor the percentage of Y-variance explained. While X-variance continues to increase with additional components, the relevant Y-variance typically plateaus.

Q7: What is the relationship between the number of descriptors, number of compounds, and optimal PLS components?

A: The optimal number of PLS components should be significantly less than both the number of compounds and the number of descriptors. As a general guideline:

- Minimum observations: 5-10 compounds per PLS component to ensure model stability [1]

- Component limit: The maximum number of meaningful PLS components cannot exceed the number of compounds in the training set

- Descriptor reduction: For datasets with thousands of descriptors (common in 3D-QSAR), apply feature selection before PLS to reduce the descriptor set to 50-100 most relevant variables [7]

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for 3D-QSAR with PLS Regression

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in PLS-based QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sybyl-X | Commercial Software | Molecular modeling and 3D-QSAR | CoMFA and CoMSIA analysis, molecular alignment, PLS regression [8] [5] |

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics | Molecular descriptor calculation | 2D/3D descriptor generation, maximum common substructure alignment [5] |

| alvaDesc | Commercial Descriptor Package | Molecular descriptor calculation | Calculation of >4000 molecular descriptors for QSAR modeling [4] |

| Dragon | Commercial Software | Molecular descriptor calculation | Calculation of 5,270 molecular descriptors for LINUX and WIN platforms [4] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Open-source Software | Molecular descriptor calculation | Calculation of 2D and 3D descriptors based on CDK library [4] |

| R pls package | Open-source Statistical Package | PLS regression analysis | Model building, cross-validation, component optimization [6] |

| Open3DQSAR | Open-source Tool | Pharmacophore modeling | Molecular interaction field calculation for 3D-QSAR [4] |

Table 4: Critical Statistical Metrics for PLS Model Validation

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² (Coefficient of Determination) | R² = 1 - (SSres/SStot) | Goodness of fit for training data | > 0.7 for reliable models |

| Q² (Cross-validated R²) | Q² = 1 - (PRESS/SStot) | Predictive ability on unseen data | > 0.5 (acceptable), > 0.7 (excellent) |

| RMSEP (Root Mean Square Error of Prediction) | RMSEP = √(∑(yᵢ-ŷᵢ)²/n) | Average prediction error | Lower values indicate better performance |

| VIP (Variable Importance in Projection) | VIP = √(p∑(SSbₕwₕ²)/∑SSbₕ²) | Contribution of each original variable | Variables with VIP > 1.0 are significant |

| SEE (Standard Error of Estimate) | SEE = √(SSres/(n-p-1)) | Precision of regression coefficients | Lower values indicate better precision |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary advantage of using PLS over Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) in QSAR? PLS is specifically designed to handle data where the number of molecular descriptors exceeds the number of compounds and when these descriptors are highly correlated (multicollinear) [9] [10]. Unlike MLR, which becomes unstable or fails under these conditions, PLS creates a set of orthogonal latent variables (components) that maximize the covariance between the predictor variables (X) and the response variable (Y) [11] [12]. This makes it particularly suitable for QSAR models built from a large number of correlated 2D or 3D molecular descriptors [9] [13].

2. My 3D-QSAR model is overfitting. How can PLS help? Overfitting often occurs when a model has too many parameters relative to the number of observations. PLS combats this through dimensionality reduction. It extracts a small number of latent components that capture the essential variance in the descriptor data that is relevant for predicting biological activity [9]. The key is to optimize the number of PLS components, typically using cross-validation techniques to find the point that maximizes predictive performance without modeling noise [9] [14].

3. How do I determine the optimal number of PLS components for my model? The optimal number of components is found through cross-validation [9] [14]. A common method is k-fold cross-validation:

- Split your training set into k subsets (e.g., 5 folds).

- Train the PLS model on k-1 folds using a provisional number of components.

- Predict the held-out fold and calculate the error.

- Repeat this process until each fold has been left out once.

- Calculate the overall cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) and standard error.

- Repeat for different numbers of components.

- The number of components that gives the highest Q² value (or lowest error) is considered optimal [9]. This process is automated in many software packages like

rQSAR[14].

4. What are the key statistical metrics for validating a PLS-based QSAR model? A robust PLS-QSAR model should be evaluated using both internal and external validation metrics, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics for PLS-QSAR Models

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| R² | Coefficient of determination for the training set | Goodness-of-fit for the training data [8] [13]. |

| Q² | Cross-validated correlation coefficient | Estimate of the model's predictive power and robustness [8] [13]. |

| SEE | Standard Error of Estimate | Measures the accuracy of the model for the training set [8]. |

| F Value | Fisher F-test statistic | Significance of the overall model [8]. |

| R²Test | Coefficient of determination for an external test set | The most reliable measure of a model's predictive ability on new data [9] [15]. |

5. Can PLS capture non-linear structure-activity relationships? Standard PLS is a linear method. However, several non-linear extensions have been developed to overcome this limitation, as shown in the table below [10].

Table 2: Common Non-Linear Extensions of PLS

| Method | Key Feature | Application in QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Kernel PLS (KPLS) | Maps data to a high-dimensional feature space using kernel functions [10]. | Suitable for complex, non-linear relationships [10]. |

| Neural Network-based NPLS | Uses neural networks to extract non-linear latent variables or for regression [10]. | Captures intricate, hierarchical patterns in data [10]. |

| PLS with Spline Transformation | Uses spline functions for piecewise linear regression [10]. | Provides flexibility and good interpretability [10]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Predictive Performance on External Test Set A model with good internal cross-validation statistics (Q²) may still perform poorly on new, unseen compounds. This is a sign of limited generalizability.

- Potential Cause 1: The model is built on molecular descriptors that are not sufficiently relevant to the biological activity, or it lacks key descriptors.

Solution: Perform rigorous feature selection before PLS modeling. Use methods like Genetic Algorithms (GA) [12] or filter methods based on correlation to identify and retain the most informative descriptors. This improves model interpretability and can enhance predictive performance [9].

Potential Cause 2: The model's Applicability Domain (AD) is not well-defined, and predictions are being made for compounds structurally different from the training set.

- Solution: Define the applicability domain of your model. This can be based on the leverage of compounds or their distance in the descriptor space. Clearly state that predictions for compounds outside this domain are unreliable [9].

Problem: Unstable Model - Small Changes in Data Lead to Large Changes in Results Model instability undermines its reliability for virtual screening or chemical design.

- Potential Cause: High leverage from outliers or an insufficient number of training compounds relative to the complexity of the structure-activity relationship.

- Solution:

- Check for Outliers: Analyze the model's residuals and leverage (Hat values) to identify influential compounds that may be distorting the model. Investigate these compounds for potential errors in structure or activity data [9].

- Increase Training Set Size and Diversity: If possible, curate a larger and more chemically diverse training set that adequately represents the chemical space of interest [9].

- Use Robust PLS Variants: Consider methods like Genetic Partial Least Squares (G/PLS), which combines genetic algorithm-based variable selection with PLS regression to build more stable and predictive models [12].

Problem: Difficulty Interpreting the PLS Model in a Chemically Meaningful Way While PLS is a "grey box" model, it should still offer insights into the Structural Features influencing activity.

- Potential Cause: Relying solely on the model's regression coefficients, which can be difficult to interpret when descriptors are correlated.

- Solution:

- Analyze Variable Importance in Projection (VIP): The VIP score measures the contribution of each descriptor to the PLS model. Focus on descriptors with a VIP score > 1.0, as these are the most relevant for explaining the activity [13].

- Visualize Contour Maps (for 3D-QSAR): If using 3D-QSAR methods like CoMFA or CoMSIA, the PLS coefficients can be visualized as 3D contour maps around a molecular scaffold. These maps intuitively show regions where specific chemical features (e.g., steric bulk, electropositive groups) increase or decrease biological activity [8].

Experimental Protocol: Developing and Validating a PLS-based 3D-QSAR Model

The following workflow, based on a recent study on MAO-B inhibitors [8], details the key steps for building a robust PLS model within a 3D-QSAR framework.

Figure 1: PLS-based 3D-QSAR Model Development Workflow

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Dataset Curation and Preparation

- Curate a set of molecules with known biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀, pIC₅₀) [9] [8].

- Standardize chemical structures: remove salts, normalize tautomers, define protonation states [9].

- For 3D-QSAR, generate low-energy 3D conformers for each compound. A common approach is to use the global minimum of the potential energy surface [15].

Molecular Alignment and Descriptor Calculation

- Align all molecules to a common template or a active reference molecule in the database. This is a critical step for 3D-QSAR methods like CoMFA and CoMSIA [8].

- Calculate 3D molecular field descriptors (e.g., steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic) using software such as Sybyl-X [8]. This generates a high-dimensional matrix (X) of molecular descriptors.

Data Set Partitioning

- Divide the dataset into a training set (typically ~80%) for model building and a test set (~20%) for external validation. Use methods like the Kennard-Stone algorithm to ensure the test set is representative of the chemical space covered by the training set [9].

PLS Model Construction and Cross-Validation

- Use the training set to build the initial PLS model, which finds latent variables that maximize covariance between the molecular fields (X) and biological activity (Y) [11] [8].

- Perform leave-one-out (LOO) or k-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal number of PLS components. The model with the highest cross-validated correlation coefficient (q² or Q²) is selected [8]. The statistical results from a published MAO-B inhibitor study are shown below.

Table 3: Exemplary PLS Model Statistics from a 3D-QSAR Study [8]

| Model | q² | r² | SEE | F Value | Optimal PLS Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMSIA | 0.569 | 0.915 | 0.109 | 52.714 | Reported as part of the model |

External Model Validation

Model Interpretation and Deployment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 4: Key Software Tools for PLS-QSAR Modeling

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Use Case in PLS-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Sybyl-X | Molecular Modeling Suite | Performing 3D-QSAR (CoMFA, CoMSIA) and generating 3D molecular field descriptors for PLS regression [8]. |

| rQSAR (R Package) | Cheminformatics & Modeling | Building QSAR models using PLS, MLR, and Random Forest directly from molecular structures and descriptor tables [14]. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Descriptor Calculation Software | Generating a wide range of 1D and 2D molecular descriptors from chemical structures for input into PLS models [9]. |

| DRAGON | Molecular Descriptor Software | Calculating thousands of molecular descriptors for QSAR modeling; often used with PLS for variable reduction [13]. |

| COMSIA Method | 3D-QSAR Methodology | A specific 3D-QSAR technique that relies on PLS regression to correlate molecular similarity fields with biological activity [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why does the total variance explained by all my PLS components not add up to 100%?

This is an expected behavior of Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, not an error in your model. Unlike Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which creates components with orthogonal weight vectors to maximize explained variance in the predictor variable (X), PLS creates components with non-orthogonal weight vectors to maximize covariance between X and the response variable (Y) [16]. Because these weight vectors are not orthogonal, the variance explained by each PLS component overlaps, and the sum of variances for all components will be less than the total variance in the original dataset [16]. A robust PLS model for prediction does not require the components to explain 100% of the variance in X.

FAQ 2: How many PLS components should I select for a robust 3D-QSAR model?

Selecting the optimal number of components is critical to avoid overfitting. The goal is to find the point where adding more components no longer significantly improves the model's predictive power [3].

A standard methodology is to use k-fold cross-validation [5] [9]. The detailed protocol is:

- Define a range of component numbers to test (e.g., 1 to 10).

- For each number of components (

n) in this range, perform k-fold cross-validation on the training set. - Build a PLS model with

ncomponents on k-1 folds and predict the held-out fold. - Calculate the mean squared error (MSE) or the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) for each

n. - Plot the performance metric (e.g., MSE) against the number of components.

- Select the number of components where the MSE is minimized or where the Q² value is maximized. Adding more components beyond this point typically leads to overfitting [3].

FAQ 3: What is the practical difference between a latent variable in PLS and a principal component in PCA?

Both are latent variables, but they are constructed with different objectives, which has direct implications for 3D-QSAR.

The table below summarizes the key differences:

| Feature | PLS (Partial Least Squares) | PCA (Principal Component Analysis) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Maximize covariance with the response (Y) [3]. | Maximize variance in the descriptor data (X). |

| Model Role | Used for supervised regression; components are directly relevant to predicting activity [17]. | Used for unsupervised dimensionality reduction; components may not be relevant to activity. |

| Output | A predictive model linking X to Y. | A transformed, lower-dimensional representation of X. |

In 3D-QSAR, PLS is preferred because it directly uses the biological activity data (Y) to shape the latent variables, ensuring they are relevant for prediction [5] [18].

FAQ 4: My 3D-QSAR model has a high R² but poor predictive ability. What might be wrong?

This is a classic sign of overfitting. Your model has memorized the noise in the training data instead of learning the generalizable structure-activity relationship.

Troubleshooting steps include:

- Reduce Model Dimensionality: You may be using too many PLS components. Re-run the cross-validation to ensure the optimal number of components is selected [3].

- Check Applicability Domain: The new compounds you are predicting may fall outside the chemical space of the compounds used to train the model. The model's predictions for these compounds are unreliable [9].

- Validate the Alignment: For 3D-QSAR methods like CoMFA, a poor molecular alignment is a primary source of error and can lead to non-predictive models [5].

Experimental Protocol: Building and Validating a 3D-QSAR Model

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing a 3D-QSAR model using PLS regression.

1. Data Collection and Preparation

- Assemble a Dataset: Collect a series of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) measured under uniform conditions [5].

- Calculate 3D Descriptors:

- Generate a low-energy 3D conformation for each molecule [5].

- Align all molecules to a common reference frame based on a putative bioactive conformation [5].

- Calculate 3D molecular field descriptors using a method like CoMFA (steric and electrostatic fields) or CoMSIA (additional fields like hydrophobic, H-bond donor/acceptor) [5] [8].

2. Model Building and Optimization

- Split Data: Divide the dataset into a training set (for model building) and an independent test set (for final validation) [9].

- Perform Feature Selection (Optional): Use Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores from a preliminary PLS model to identify and retain only the most relevant descriptors [3].

- Determine Optimal PLS Components:

- Use the k-fold cross-validation method described in FAQ 2 on your training set.

- The optimal number of components is identified by the model with the highest cross-validated Q² value [5].

3. Model Validation and Interpretation

- Build Final Model: Construct the final PLS model using the optimal number of components on the entire training set.

- External Validation: Use the held-out test set to evaluate the model's predictive power. Report R² and RMSE for the test set predictions [19] [8].

- Interpret Contour Maps: Visualize the 3D-QSAR model as contour maps. These maps show regions where specific molecular properties (steric bulk, positive charge, etc.) are favorable or unfavorable for biological activity, providing a guide for chemical modification [5].

3D-QSAR Model Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The following table lists key software tools and their functions for 3D-QSAR modeling.

| Tool Name | Function in 3D-QSAR | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Sybyl-X | A comprehensive molecular modeling suite used for structure building, geometry optimization, molecular alignment, and performing CoMFA/CoMSIA studies [5] [8]. | [5] [8] |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. Used for generating 2D and 3D molecular structures, calculating 2D descriptors, and performing maximum common substructure (MCS) searches for alignment [5] [20]. | [5] [20] |

| MATLAB (plsregress) | A high-level programming platform. Its plsregress function is used to perform PLS regression and calculate the percentage of variance explained (PCTVAR) by each component [21]. |

[21] |

| scikit-learn / OpenTSNE | Python libraries for machine learning. scikit-learn provides PCA and other utilities, while OpenTSNE offers efficient implementations of t-SNE for chemical space visualization [20]. | [20] |

The 3D-QSAR Design-Iterate Loop

The Critical Link Between PLS Components and Model Predictivity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental role of PLS components in a 3D-QSAR model? PLS components are latent variables that serve as the foundational building blocks of a 3D-QSAR model. They are linear combinations of the original 3D molecular field descriptors (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, etc.) that are constructed with a specific goal: to maximize the covariance between the predictor variables (X) and the biological activity response (y). Unlike methods like Principal Component Regression (PCR) that only consider the variance in X, PLS explicitly uses the response variable y to guide the creation of components, ensuring they are relevant predictors of biological activity [22] [23].

2. How does the number of PLS components directly impact model predictivity? Selecting the optimal number of PLS components is critical to balancing model fit and predictive ability.

- Too few components lead to underfitting, where the model is too simple to capture the essential structure-activity relationship, resulting in high prediction errors for both training and new compounds [22].

- Too many components lead to overfitting, where the model starts to fit the noise in the training data rather than the underlying trend. While it may perfectly predict the training set, its performance will drop significantly when applied to new, unseen test data [22]. A robust model achieves a low estimated prediction error on an external test set, which is typically found at an intermediate, optimal number of components [23].

3. What are the key statistical metrics for validating a PLS-based 3D-QSAR model? A valid 3D-QSAR model should be evaluated using a suite of metrics, not just a single one [24]. The most common are:

- q² (Q²): The cross-validated coefficient of determination (e.g., from Leave-One-Out validation). It estimates the model's predictive power from the training process. A value above 0.5 is generally considered acceptable [8] [25].

- r² (R²): The conventional coefficient of determination for the training set. It measures the goodness-of-fit [8] [25].

- r²pred: The coefficient of determination for an external test set. This is the most reliable measure of a model's real predictive power for new compounds [25].

- SEE (or S): The Standard Error of Estimate, which indicates the average accuracy of the predictions [8].

The following table summarizes benchmark values from a robust 3D-QSAR study on steroids using the CoMSIA method:

Table 1: Benchmark Validation Metrics from a CoMSIA Study on Steroids [25]

| Metric | Reported Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| q² | 0.609 | Good internal predictive ability |

| r² | 0.917 | Excellent fit to the training data |

| SEE (S) | 0.33 | Low estimation error |

| Optimal Number of Components | 3 | Model of optimal complexity |

4. My model has a high R² but poor predictive power for new compounds. What is the most likely cause? This is a classic sign of overfitting [22]. Your model has likely been trained with too many PLS components, causing it to memorize the training data, including its experimental noise, instead of learning the generalizable structure-activity relationship. To fix this, you must re-evaluate your model using cross-validation or an external test set to find the optimal, lower number of components that minimizes the prediction error for new data [24] [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: How to Determine the Optimal Number of PLS Components

Detailed Protocol: The most statistically sound method for choosing the number of components is cross-validation (CV). The following workflow, which can be implemented in tools like R or Python, is recommended [22] [23]:

Figure 1: The workflow illustrates the process of determining the optimal number of PLS components through cross-validation, starting from data preparation, iterating through different component numbers, performing cross-validation to calculate MSEP, and finally selecting the number with the lowest MSEP for model building and validation.

- Prepare Data: Split your dataset into a training set and a separate, external test set. The test set will be used for final validation only.

- Iterate Component Numbers: For a reasonable range of component numbers (e.g., 1 to 10 or 15), perform k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 10-fold) on the training set.

- Calculate MSEP: For each number of components, calculate the Mean Squared Prediction Error (MSEP) across all cross-validation folds.

- Plot and Identify Minimum: Plot the MSEP values against the number of components. The optimal number is the one that minimizes the MSEP. Sometimes, a parsimonious choice is the number of components where the MSEP curve first plateaus or is not significantly worse than the minimum.

- Build and Validate: Build your final model on the entire training set using the optimal number of components. Finally, assess its predictivity using the held-out external test set by calculating r²pred [23].

Issue 2: Low q² and r²pred Values After Model Construction

A model with low predictive power (q² and r²pred < 0.5) indicates fundamental issues. Follow this diagnostic flowchart to identify and resolve the problem.

Figure 2: This decision tree helps diagnose the root cause of a model with low predictive power (low q² and r²pred), guiding the user to check for issues in data quality, molecular alignment, descriptor selection, and the final model validation step.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Data Quality Problem: The biological activity data may come from inconsistent experimental assays or have a narrow range, making it difficult to find a meaningful correlation [5]. Solution: Re-check and curate your input data, ensuring all activities were measured under uniform conditions and cover a wide enough potency range.

- Poor Molecular Alignment: In 3D-QSAR, the alignment of molecules is a critical and sensitive step. An incorrect alignment, which does not reflect the true bioactive conformations, will produce meaningless field descriptors [5]. Solution: Re-visit your alignment strategy. Use a robust maximum common substructure (MCS) algorithm or docked conformations to achieve a pharmacologically relevant alignment [5].

- Insufficient Molecular Descriptors: The chosen molecular fields (e.g., only steric and electrostatic) might not capture the key interactions governing binding affinity. Solution: Consider using the extended fields available in methods like CoMSIA, which include hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond donor and acceptor fields, to provide a more holistic view of the interactions [25] [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key computational tools and methods for developing and validating 3D-QSAR models.

| Tool/Method | Type | Primary Function in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Sybyl (Tripos) | Proprietary Software Suite | The historical industry standard for performing CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses, providing integrated tools for alignment, field calculation, and PLS regression [25]. |

| Py-CoMSIA | Open-Source Python Library | A modern, open-source implementation of CoMSIA that increases accessibility and allows for customization of the 3D-QSAR workflow [25]. |

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics Library | Used for generating 3D molecular structures from 2D representations, energy minimization (using UFF), and identifying maximum common substructures (MCS) for alignment [5]. |

| PLS Regression | Statistical Algorithm | The core multivariate regression method used to correlate 3D field descriptors with biological activity and build the predictive model [5] [22]. |

| Cross-Validation (e.g., LOOCV, 10-fold) | Validation Technique | A crucial method for estimating the predictive performance of a model during training and for selecting the optimal number of PLS components without overfitting [22] [23]. |

| Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) | 3D-QSAR Method | An advanced 3D-QSAR technique that uses Gaussian functions to calculate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields, often providing more interpretable and robust models than its predecessor, CoMFA [25] [26]. |

A Step-by-Step Guide to Building and Optimizing Your PLS 3D-QSAR Model

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the minimum data point requirements for calculating valid 3D descriptors and building reliable 3D-QSAR models? A sufficient number of data points is critical for a robust model. The absolute minimums are guided by the complexity of the molecular shape you are trying to fit [27].

- Cylinder: 5 points

- Cone: 6 points

- Sphere: 4 points

- Plane: 3 points

Using only the absolute minimum points will result in a measured shape error of zero, which is not realistic. It is recommended to densely measure features with more points to capture true shape variations for effective fitting in your 3D-QSAR studies [27].

Q2: My dataset contains both continuous (e.g., IC50) and categorical (e.g., active/inactive) biological activity data. How should I structure this for analysis? You must first determine the nature of your data, as this dictates the visualization and analysis approach [28]. Biological activity data typically falls into these categories:

- Quantitative Data (IC50, pIC50): These are ratio-level data. They have an absolute zero (no activity) and you can meaningfully calculate ratios (e.g., a 10 nM IC50 is ten times more potent than a 100 nM IC50).

- Qualitative/Categorical Data (Active/Inactive): These are nominal or ordinal data. For example, classifying compounds as "Active," "Inactive," or "Intermediate" represents an ordinal scale.

For 3D-QSAR, pIC50 (-logIC50) is the preferred continuous variable because it linearizes the relationship with binding energy [29].

Q3: What is the recommended color palette for visualizing different data types in my 3D-QSAR results? Using color palettes aligned with your data type prevents misinterpretation [28].

- Table 1: Recommended Color Palettes for Biological Data Visualization

| Data Type | Example | Recommended Palette | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential | pIC50 values (low to high) | Viridis | Shows ordered data from lower to higher values. Luminance increases monotonically. |

| Diverging | Residuals (negative vs. positive) | ColorBrewer Diverging | Highlights deviation from a median value (e.g., mean activity). |

| Qualitative | Different protein targets | Tableau 10 | Distinguishes between categories with no inherent order. |

These palettes are perceptively uniform and friendly to users with color vision deficiencies [28].

Q4: How do I handle errors related to "feature direction" or "polar axis" during 3D descriptor alignment? This error arises when the alignment of your molecules does not match the polar coordinate system defined by your 3D-QSAR software [27]. To resolve this:

- Ensure all molecules are aligned such that their dominant axes are nominally parallel to the polar axis defined by the common framework.

- The benchmark reference frame must define a clear polar origin. Check that your alignment protocol correctly establishes this axis.

- If your molecules are coaxial with the alignment axis, a radial (diameter-based) tolerance zone might be more appropriate than a polar one [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Correlation or Poor Model Performance During 3D-QSAR Validation Poor performance can stem from issues in data curation, descriptor calculation, or model optimization.

Potential Cause 1: Incorrect or Inconsistent Biological Activity Data.

- Solution: Implement a rigorous data curation protocol.

- Protocol: Standardize activity measures (e.g., consistently use pIC50 over IC50). Identify and handle outliers using statistical methods (e.g., Z-scores). Verify that all data points are from comparable experimental assays (e.g., same cell line, pH, incubation time).

Potential Cause 2: Inadequate Constraint of Molecular Conformation and Alignment.

- Solution: Ensure your molecular alignment protocol properly constrains all degrees of freedom.

- Protocol: The benchmark reference frame used for aligning molecules must fully define the orientation. If the software reports that the "benchmark reference frame must define a clear polar origin," review your alignment rules. As noted in troubleshooting guides, "Ensure the benchmark reference frame defines a clear polar axis" [27].

Potential Cause 3: Suboptimal Number of PLS Components.

- Solution: Systematically determine the optimal number of PLS components to avoid overfitting or underfitting.

- Protocol: Use cross-validation (e.g., leave-one-out or group cross-validation). The optimal number of components is typically indicated by the number that gives the minimum cross-validated standard error of prediction. A scree plot of the cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) against the number of components can visually identify the point where adding more components no longer significantly improves the model.

Problem: "Feature点数过少, 无法有效拟合" (Insufficient Feature Points for Effective Fitting) This error indicates that a molecular feature or descriptor does not have enough data points to define its 3D shape uniquely [27].

- Potential Cause: The molecular structure or the field around it has been sampled with too few points for the software to perform a reliable fit.

- Solution:

- Increase the density of points used to represent the molecular structure or its interaction fields.

- For complex, nearly symmetric surfaces, ensure the benchmark reference frame uses other benchmarks to constrain the uncertain degrees of freedom [27].

- Refer to the minimum point requirements in FAQ #1 as a baseline and exceed them where possible.

Problem: "特征方向必须与其对应的极坐标公差带匹配" (Feature Direction Must Match Polar Tolerance Zone) This error is related to the incorrect orientation of molecules or their descriptors relative to the defined alignment axis [27].

- Potential Cause: The theoretical (THEO) direction of the molecular feature or the entire molecule is not parallel to the polar axis established by the benchmark reference frame.

- Solution:

- Check the nominal orientation of your aligned molecules in the software.

- Ensure the alignment protocol correctly constrains the primary molecular axis to the polar axis of the system. The software expects that "all molecular features must nominally be parallel to the polar axis defined by the benchmark reference frame" [27].

- If the issue persists, review the fundamental alignment rules in your molecular spreadsheet.

The Scientist's Toolkit

- Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR

| Item | Function in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|

| Curated Bioactivity Database (e.g., ChEMBL) | Provides publicly available, standardized bioactivity data (e.g., IC50, Ki) for model building and validation. |

| Molecular Spreadsheet Software (e.g., Sybyl) | The core environment for storing molecular structures, calculated descriptors, and biological activity data, and for performing statistical analysis. |

| 3D-QSAR Software with CoMFA/CoMSIA | Enables the calculation of steric, electrostatic, and other molecular interaction fields (MIFs) that form the 3D descriptors for the model [29]. |

| Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock Vina) | Used to generate a common alignment hypothesis for molecules by docking them into a protein's active site, which can then be used for 3D descriptor calculation. |

| Geometry Optimization Software (e.g., Gaussian) | Used to calculate the minimal energy 3D conformation of each molecule, which is a critical first step before alignment and descriptor calculation [29]. |

Workflow and Troubleshooting Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for data preparation and the key troubleshooting checkpoints.

3D-QSAR Data Prep and Troubleshooting

When a troubleshooting step is triggered (e.g., a "Descriptor Error"), the following detailed logic path should be followed to resolve the issue.

Resolving 3D Descriptor Calculation Errors

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is molecular alignment considered the most critical step in CoMFA/CoMSIA studies? Molecular alignment is the foundation of CoMFA/CoMSIA because these methods are highly alignment-dependent [30]. The three-dimensional fields (steric, electrostatic, etc.) that are calculated and correlated with biological activity are entirely determined by the spatial orientation of the molecules. An incorrect alignment introduces significant noise into the descriptor matrix, leading to models with little to no predictive power. The signal in a 3D-QSAR model primarily comes from the alignments themselves [31].

Q2: What are the common methods available for aligning molecules? Several methods are commonly used for molecular alignment, each with its own strengths:

- Atom-Based Superimposition: This method involves atom-to-atom pairing between molecules, typically aligning a common structural core or pharmacophore [32].

- Field and Shape-Guided Alignment: This approach uses molecular fields (steric and electrostatic) and overall molecular shape to find the optimal superposition, often resulting in a more biologically relevant alignment than rigid atom-based methods [31].

- Field Fit Procedure: This technique minimizes the differences in the calculated steric and electrostatic fields between various molecules to achieve an optimal alignment [33].

Q3: I have an outlier in my model with poor predictive activity. Should I realign it to improve the fit? No. This is a common but critical error. You must not alter the alignment of any molecule based on the output of the model (i.e., its predicted activity) [31]. Doing so biases the model by making the input data (the alignments) dependent on the output data (the activities), which invalidates the model's statistical validity and predictive power. Alignment must be fixed before running the QSAR analysis, and activities should be ignored during the alignment process.

Q4: What is the key difference in the fields calculated by CoMFA and CoMSIA? The key difference lies in the potential functions used:

- CoMFA uses Lennard-Jones (steric) and Coulombic (electrostatic) potentials. These potentials can be very steep near the molecular surface, leading to singularities and requiring the user to define arbitrary cutoff limits [30] [32].

- CoMSIA uses a Gaussian-type distance dependence for all its fields (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, H-bond donor, H-bond acceptor). This results in much "softer" potentials without singularities, which avoids the issues of cutoffs and steep gradients [30] [34].

Q5: How do the interpretation of CoMFA and CoMSIA contour maps differ? The contour maps provide different guides for design:

- CoMFA maps indicate regions in space around the aligned molecules where interactions with a putative receptor environment are favored or disfavored [30].

- CoMSIA maps highlight regions within the area occupied by the ligand skeletons that require a specific physicochemical property for high activity. This is often a more direct guide for modifying the ligand structure itself [30] [34].

Troubleshooting Guide

Poor Model Predictivity (q²orr²pred)

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

Low cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) and poor predictive r² for the test set. |

Incorrect or inconsistent molecular alignment. This is the most common source of failure. | Re-check all alignments visually and based on chemical intuition. Use multiple reference molecules to constrain the alignment of the entire set [31]. |

| The chosen bioactive conformation is incorrect for one or more molecules. | Re-visit conformational analysis. If available, use experimental data (e.g., X-ray crystallography, NMR) or docking poses to inform the bioactive conformation [32]. | |

| The dataset is non-congeneric or molecules have different binding modes. | Ensure all compounds act via the same mechanism. Consider splitting the dataset into more congeneric subsets. |

Unstable or Fragmented Contour Maps

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Contour maps are fragmented, disconnected, and difficult to interpret chemically. | Using standard CoMFA with its steep potential fields, which are sensitive to small changes in atom position. | Switch to CoMSIA. The Gaussian functions used in CoMSIA produce smoother, more contiguous, and more interpretable contour maps [30] [34]. |

| The molecular alignment is too rigid, not accounting for plausible flexibility in binding. | Ensure the alignment reflects a plausible pharmacophore. Using field-based or field-fit alignment can sometimes produce more coherent maps than rigid atom-based alignment. |

Model Overfitting

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

High r² for the training set but very low r² for the test set, often with too many PLS components. |

The number of PLS components is too high relative to the number of molecules. | Use cross-validation to determine the optimal number of components. The component number that gives the highest q² and lowest Standard Error of Prediction (SEP) should be selected. |

| Inadvertent bias introduced during alignment by tweaking based on activity. | Strictly follow the protocol of finalizing all alignments before any model processing or analysis, without considering activity values [31]. |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Workflow for Molecular Alignment and 3D-QSAR

The following diagram illustrates the critical, multi-step workflow for a robust CoMFA/CoMSIA study, emphasizing the iterative alignment process that must be completed before model building.

Detailed Methodology for Robust Alignment

This protocol expands on the "Check All Alignments" step from the workflow above.

Objective: To achieve a consistent, biologically relevant alignment for a congeneric series of compounds prior to CoMFA/CoMSIA analysis. Principle: Use a combination of substructure and field-based alignment, iteratively refined with multiple reference molecules to ensure the entire dataset is well-constrained [31].

Procedure:

- Initial Setup:

Primary Alignment:

- Align the entire dataset to the single template molecule. Use a substructure alignment algorithm to ensure the common core of the series is perfectly overlaid.

- Subsequently, employ a field-based alignment (or "Maximum" scoring mode) to optimize the orientation of substituents based on steric and electrostatic similarity [31].

Iterative Checking and Refinement:

- Visually inspect every molecule in the aligned set. Pay special attention to molecules with substituents that point into regions not occupied by the initial template.

- For any molecule that appears poorly aligned (e.g., a ring system is flipped, a chain is pointing in the wrong direction), do not simply manually adjust it. Instead:

- Select a representative of the poorly-aligned group and manually tweak its alignment to a chemically sensible orientation, ignoring its biological activity.

- Promote this molecule to a reference.

- Re-align the entire dataset against the now multiple references (the original template plus the new ones), again using substructure and field-based alignment.

- Repeat this process until all molecules in the dataset are aligned in a consistent and chemically logical manner. For most datasets, 3-4 reference molecules are sufficient to constrain all others [31].

Pre-QSAR Freeze:

- Once satisfied with the alignment, freeze the molecular coordinates. This is the final alignment that will be used for all subsequent steps.

- Crucial: Do not modify the alignment after this point, regardless of initial model outcomes [31].

Protocol for CoMSIA Field Calculation

Objective: To calculate the five similarity indices fields used in a Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis. Principle: A common probe atom is placed at each point on a lattice surrounding the aligned molecules, and similarity indices are calculated using a Gaussian function to avoid singularities [30] [35].

Procedure:

- Grid Box Creation: Place the aligned molecules in the center of a 3D lattice. The grid should typically extend 2.0 Å beyond the molecular dimensions in all directions. A standard grid spacing of 2.0 Å is often used [30].

- Probe Definition: A common probe atom with a radius of 1.0 Å and charge of +1.0 is used. Its hydrophobicity and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor properties are typically set to 1 [30].

- Field Calculation: Calculate the five CoMSIA similarity fields at each grid point using the Gaussian function for the following properties [30] [35]:

- Steric (van der Waals interactions)

- Electrostatic (Coulombic interactions)

- Hydrophobic

- Hydrogen Bond Donor

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor

- Model Building: The calculated field energies serve as descriptors. Use the Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression method to correlate these descriptors with the biological activity data and build the predictive model [30] [36].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential computational tools and methodological components for conducting CoMFA/CoMSIA studies.

| Item Name | Function / Role in Experiment | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL-X | Integrated molecular modeling software suite. | A commercial platform that provides comprehensive tools for CoMFA and CoMSIA, including structure building, minimization, alignment, and statistical analysis [35]. |

| OpenEye Orion | Software for 3D-QSAR model building and prediction. | A modern implementation that uses shape and electrostatic featurization, machine learning, and provides prediction error estimates [37]. |

| Cresset Forge/Torch | Software for ligand-based design and 3D-QSAR. | Specializes in field-based molecular alignment and similarity calculations, which are foundational for its 3D-QSAR implementations [31]. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Statistical regression method. | The standard algorithm for correlating the thousands of field descriptors (X-matrix) with biological activity (Y-matrix) in CoMFA/CoMSIA. It handles collinear data and is a reduced-rank regression method [30] [36]. |

| Gaussian Potential Function | Mathematical function for calculating molecular fields. | Used in CoMSIA to compute similarity indices. Provides a "softer" potential than CoMFA, avoiding singularities and producing more interpretable contour maps [30] [34]. |

| Lennard-Jones & Coulomb Potentials | Mathematical functions for calculating molecular fields. | Traditional potentials used in CoMFA to compute steric and electrostatic fields, respectively. They can be sensitive to small changes in atom position [32]. |

Determining the Optimal Number of PLS Components Using Cross-Validation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary purpose of cross-validation in a PLS-based 3D-QSAR model? The primary purpose is to determine the optimal number of PLS components (latent variables) to use in the final model, thereby ensuring its predictive accuracy and generalizability for new, unseen compounds. Cross-validation helps avoid both underfitting (too few components, model is too simple) and overfitting (too many components, model is too adapted to calibration data and performs poorly on new data) [22].

2. What is the key statistical metric for selecting the optimal number of components during cross-validation? The key metric is the cross-validated correlation coefficient, denoted as Q² (or q²). The optimal number of components is typically the one that maximizes the Q² value [1]. Sometimes, the component number just before the Q² value plateaus or begins to decrease is selected to enforce model parsimony.

3. What is the difference between Leave-One-Out (LOO) and repeated double cross-validation (rdCV)?

- Leave-One-Out (LOO): A single compound is excluded from the training set, a model is built with the remaining compounds, and the activity of the excluded compound is predicted. This is repeated until every compound has been excluded once [38] [1]. While common, it may sometimes overestimate the model's predictivity [1].

- Repeated Double Cross-Validation (rdCV): A more robust and cautious strategy. It involves an outer loop to estimate the prediction error for test sets and an inner loop to optimize the model complexity (i.e., the number of PLS components) for each outer training set. This process is repeated multiple times to ensure stability [22].

4. My model has a high fitted correlation coefficient (R²) but a low cross-validated Q². What does this indicate? A high R² coupled with a low Q² is a classic sign of overfitting. The model has too many components and has learned the noise and specific details of the training set instead of the underlying structure-activity relationship. This leads to poor performance when predicting new compounds. You should reduce the number of PLS components in your model [22] [1].

5. How does variable selection impact the optimal number of PLS components? Including a large number of irrelevant or noisy descriptors can destabilize the PLS solution and lead to a model that requires more components to capture the true signal. Applying variable selection (e.g., using genetic algorithms) to reduce descriptors to a relevant subset often results in a model with a lower optimal number of components, improved stability, and higher predictivity (Q²) [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unstable or Poor Q² Values

Problem: The Q² value from cross-validation is low, does not converge, or changes dramatically with small changes in the number of components.

Solution:

- Verify Data Pre-processing: Ensure your biological activity data (e.g., IC50) is measured under uniform conditions and is accurate. Confirm that molecular structures are correctly built and optimized, and that the molecular alignment is pharmacologically relevant [5].

- Check for Outliers: Identify and investigate compounds that are consistently poorly predicted during cross-validation. These outliers may have erroneous activity data or possess a unique binding mode not captured by the model [25].

- Increase Validation Rigor: Switch from a simple LOO cross-validation to a more robust method like repeated double cross-validation (rdCV) or use multiple random test sets. This provides a more reliable and cautious estimate of the optimal number of components and model performance [22].

- Implement Variable Selection: Use a genetic algorithm or other feature selection methods to eliminate noisy, irrelevant, or constant descriptors. This can significantly improve the Q² and stabilize the model [1].

Issue 2: Selecting the Correct Number from a Q² Plot

Problem: The Q² plot shows multiple local maxima or a very shallow peak, making it difficult to choose the definitive optimal number of components.

Solution:

- Apply the "One Standard Error" Rule: Calculate the standard error of the Q² estimates. Often, selecting the least complex model (fewer components) whose Q² is within one standard error of the maximum Q² value is a good practice. This promotes a simpler, more robust model.

- Examine the Validation Plot: The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for evaluating cross-validation results to select the optimal number of components.

- Prioritize Parsimony: When in doubt, choose the model with fewer components. A simpler model is generally more interpretable and more likely to be generalizable. For example, in a 3D-QSAR study on oxadiazole antibacterials, an optimal number of 5 or 6 components was chosen based on the highest q² value [38].

Comparative Analysis of Cross-Validation Methods

The table below summarizes the characteristics of different cross-validation methods used to determine the optimal number of PLS components.

| Method | Key Feature | Advantage | Disadvantage | Reported Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leave-One-Out (LOO) | Sequentially excludes one compound, models the rest, and predicts the excluded one [1]. | Simple to implement; efficient for small datasets. | Can overestimate predictivity; potentially unstable estimates [22] [1]. | Standard CoMFA/CoMSIA models (e.g., oxadiazole antibacterials [38]). |

| Repeated Double CV (rdCV) | Nested loop: outer loop estimates test error, inner loop optimizes components for each training set [22]. | Provides a more reliable and cautious performance estimate; robust against overfitting. | Computationally intensive. | Rigorous evaluation of QSPR models for polycyclic aromatic compounds [22]. |

| Test Set Validation | Dataset is split once into a training set (for model building) and a test set (for final validation) [38]. | Provides a straightforward assessment of predictive power on unseen data. | Dependent on a single, potentially unlucky, data split; does not directly optimize component number. | 3D-QSAR on oxadiazoles (25-molecule test set) [38]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Procedure for Determining PLS Components via LOO-CV

This protocol outlines the common steps for using Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation in 3D-QSAR studies, as implemented in software like Sybyl or Py-CoMSIA [38] [25].

1. Objective: To establish the optimal number of latent variables (PLS components) for a 3D-QSAR model that maximizes the predictive ability for new compounds.

2. Materials and Software:

- A dataset of compounds with known biological activities (e.g., IC50, pMIC).

- Pre-calculated 3D molecular field descriptors (e.g., from CoMFA or CoMSIA).

- Software with PLS and cross-validation capabilities (e.g., Sybyl, Py-CoMSIA [25], R packages

plsorchemometrics[22]).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Import the aligned molecules and their calculated 3D field descriptors (steric, electrostatic, etc.) into the modeling software.

- Step 2: Initiate the PLS regression analysis with the LOO cross-validation option.

- Step 3: Set the maximum number of components to test (e.g., 10-15). The software will then:

a. For a given number of components

A, repeatedly build a model using (N-1) compounds. b. Predict the activity of the one omitted compound. c. Calculate the Predicted Residual Sum of Squares (PRESS) for all N cycles: ( PRESS = \sum (y{actual} - y{predicted})^2 ) [1]. - Step 4: The software computes the cross-validated ( R^2 ), or ( Q^2 ), for each component count

Aas: ( Q^2 = 1 - \frac{PRESS}{SS} ) where ( SS ) is the total sum of squares of the activity values' deviations from the mean [1]. - Step 5: Identify the number of components that yields the highest Q² value. This is considered the optimal number for the final model.

Protocol 2: Advanced Validation Using Repeated Double Cross-Validation (rdCV)

This protocol describes a more rigorous method for model optimization and validation, recommended for high-stakes applications [22].

1. Objective: To obtain a stable and reliable estimate of the optimal number of PLS components and the model's prediction error, minimizing the risk of over-optimism.

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Outer Loop. Split the entire dataset into ( k ) segments (folds). For each unique fold as the test set:

- Step 2: Inner Loop. Use the remaining (k-1) folds as the training set. On this training set, perform another cross-validation (e.g., LOO) to determine the optimal number of components,

A_opt, that gives the best Q². - Step 3: Using this

A_opt, build a PLS model on the entire (k-1) training folds. - Step 4: Predict the compounds in the held-out test fold and calculate the prediction errors.

- Step 2: Inner Loop. Use the remaining (k-1) folds as the training set. On this training set, perform another cross-validation (e.g., LOO) to determine the optimal number of components,

- Step 5: Repeat the entire process (e.g., 100-1000 times) with different random segmentations of the data into ( k ) folds to ensure stability.

- Step 6: The overall model performance is estimated from the pooled predictions of all test sets across all repetitions. The distribution of the selected

A_optfrom the inner loops indicates the stable optimal number of components.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and their functions used in PLS component optimization for 3D-QSAR.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in PLS Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| R Software Environment [22] | Open-source Programming Language | Provides a flexible platform for statistical computing; packages like pls and chemometrics offer PLS regression and cross-validation routines. |

| Sybyl (Tripos) [38] [25] | Commercial Software Suite | The classic platform for CoMFA/CoMSIA studies; includes integrated tools for molecular alignment, field calculation, PLS, and LOO cross-validation. |

| Py-CoMSIA [25] | Open-source Python Library | A modern, accessible implementation of CoMSIA; allows for calculation of similarity indices and building of PLS models with cross-validation. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) [1] | Computational Method | Used for variable selection prior to PLS; optimizes descriptor subset to maximize Q², leading to more robust models with fewer components. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) [22] [1] | Regression Algorithm | The core method that handles correlated descriptors and projects them into latent variables (components), the number of which is optimized by cross-validation. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: In my 3D-QSAR model, how should I interpret a regression coefficient for a specific region in the contour map? A1: Regression coefficients in 3D-QSAR models, such as those from PLS-based methods like L3D-PLS, link molecular structure to biological activity [39]. A positive coefficient in a region indicates that introducing bulky or electrostatically favorable groups at that location is likely to increase the compound's biological activity. Conversely, a negative coefficient suggests that introducing groups there may decrease activity. These coefficients are visually represented in contour maps, where different colors (e.g., green for favorable, red for unfavorable) show these structural requirements [39].

Q2: What does a VIP Score less than 0.8 tell me about a specific field descriptor in my model? A2: The Variable Importance in the Projection (VIP) score measures a descriptor's contribution to the model's predictive power [40]. A VIP score below 0.8 generally indicates that the descriptor is unimportant for predicting biological activity [40]. You can consider excluding such descriptors from future models to simplify the model and potentially improve its interpretability and robustness.

Q3: My contour map seems to contradict the VIP scores. Which one should I trust for lead optimization? A3: This is not necessarily a contradiction but rather a view of different information. Use them in conjunction:

- VIP Scores tell you which descriptors are most important globally for the model's predictive power [40].

- Contour Maps and Regression Coefficients show where in 3D space specific structural features impact activity (steric, electrostatic) and in what direction [39].

For lead optimization, prioritize modifying structures in the high-impact regions identified by the contour map, especially those associated with descriptors that have high VIP scores. This ensures you are focusing on changes that the model deems most critical for activity.

Q4: What is the optimal number of PLS components to use in my 3D-QSAR model to avoid overfitting? A4: The optimal number of PLS components is determined through cross-validation [40] [22]. The standard method is to use a Leave-one-out cross-validation process. A PRESS Plot is used to find the point where the root mean PRESS is at a minimum. The number of components at this minimum is the optimal number [40]. Using more components than this will lead to overfitting, where the model fits the training data well but performs poorly on new, test compounds [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Predictive Accuracy of the 3D-QSAR Model A model that performs well on training data but poorly on test data is likely overfitted.

- Potential Cause 1: Too many PLS components were used in the model [22].

- Solution: Re-evaluate the number of components using repeated double cross-validation (rdCV). Use the number of components where the prediction error for the test sets is minimized [22].

- Potential Cause 2: The molecular alignment of your compound set is incorrect or suboptimal.

- Solution: Revisit the ligand alignment protocol. The accuracy of methods like L3D-PLS is dependent on pre-aligned molecular datasets [39]. Ensure the bioactive conformation and a consistent frame of reference are used.

- Potential Cause 3: The chemical space of your training set is too narrow or does not represent the test set.

- Solution: Curate your training set to ensure it is congeneric and covers a broad, relevant chemical space. The model cannot reliably extrapolate to entirely new chemotypes [41].

Problem 2: Interpreting Complex Contour Maps with Ambiguous Regions It can be difficult to derive clear design rules when contour maps are crowded or show conflicting guidance.

- Potential Cause: The model is being influenced by multiple, correlated steric and electrostatic fields.

- Solution:

- Refer to VIP Scores: Identify the most important field descriptors (VIP > 0.8) and focus your interpretation on those regions [40].

- Analyze Regression Coefficients: Look at the numerical regression coefficients for the specific grid points in the ambiguous region. The magnitude and sign of the coefficient will clarify the direction and strength of the effect [39].

- Use the Model Prospectively: Design a few test compounds based on your interpretation and use the model to predict their activity. This iterative process helps validate your hypotheses.

- Solution:

Problem 3: High Variation in Model Performance with Small Changes in the Dataset The model's performance is unstable when compounds are added or removed.

- Potential Cause 1: The dataset is too small, or the model complexity is too high relative to the number of compounds.

- Solution: For building a stable model, a sufficient number of compounds is necessary. If working with a small dataset, use simpler models with very few components and consider methods like L3D-PLS which are designed for small datasets [39].

- Potential Cause 2: The presence of outliers or errors in the experimental activity data.

- Solution: Rigorously check the quality of the input data. Ensure molecular structures are correct (e.g., stereochemistry) and that the experimental biological data is reliable. Remove or correct any identified outliers [41].

Key Quantitative Data in 3D-QSAR with PLS

The following tables summarize critical metrics and thresholds for interpreting and validating your PLS-based 3D-QSAR models.

Table 1: Interpreting Key PLS Model Outputs

| Output | Description | Interpretation Guide | Common Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficients | Indicates the magnitude and direction of a field descriptor's effect on biological activity [39]. | Positive: Favorable for activity. Negative: Unfavorable for activity. | N/A (Relative magnitude is key) |

| VIP Score | Measures a variable's importance in explaining the variance in both predictors (X) and response (Y) [40]. | VIP ≥ 0.8: Important variable. VIP < 0.8: Unimportant variable [40]. | 0.8 |

| R² / Q² | R²: Goodness-of-fit. Q²: Goodness-of-prediction from cross-validation [22]. | High R² & Q² (e.g., >0.6) indicate a robust model. Large gap between R² and Q² suggests overfitting [22]. | > 0.6 (Field dependent) |

| Optimal PLS Components | The number of latent variables that minimizes prediction error [40] [22]. | Determined via cross-validation; look for the minimum in a PRESS plot [40]. | N/A (Data dependent) |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR Modeling

| Item | Function in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|