Optimized RNA Extraction from FFPE Samples for Reliable qPCR: A Complete Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on extracting high-quality RNA from Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues for accurate qPCR analysis.

Optimized RNA Extraction from FFPE Samples for Reliable qPCR: A Complete Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on extracting high-quality RNA from Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues for accurate qPCR analysis. Covering foundational challenges to advanced optimization strategies, it details how factors like fixation chemistry, storage time, and extraction methodology impact RNA yield, purity, and integrity. The content systematically evaluates commercial kits, outlines robust protocols for cDNA synthesis and gene expression analysis, and presents rigorous validation frameworks to ensure data reliability in translational cancer research and clinical applications.

Understanding FFPE RNA Challenges: Degradation, Cross-linking, and Quality Assessment

The Fundamental Chemistry of Formalin Fixation and RNA Cross-linking

Formalin fixation, the standard method for preserving clinical tissue samples, presents a significant paradox for molecular biology: while it creates a stable morphological archive, it chemically modifies and compromises nucleic acids. This whitepaper examines the fundamental chemistry of formaldehyde-induced cross-linking, focusing on its impact on RNA within the context of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples. We detail the biochemical mechanisms underlying RNA-protein and RNA-RNA cross-links, explain how these modifications impede successful RNA extraction and quantification, and present optimized experimental protocols to overcome these challenges for reliable qPCR analysis. Understanding these chemical principles is essential for developing robust RNA extraction methodologies from FFPE tissues, enabling researchers to leverage vast archival sample repositories for transcriptional profiling in research and drug development.

Formalin fixation has served as the cornerstone of pathological tissue preservation for decades, creating stable FFPE blocks that maintain tissue architecture at room temperature. The process involves submerging tissue in formalin, an aqueous solution of formaldehyde (FA), which penetrates cells and reacts with biological macromolecules including proteins, DNA, and RNA. While this process preserves morphological information essential for histological diagnosis, it introduces extensive biochemical modifications that complicate subsequent molecular analyses, particularly RNA extraction.

The primary value of FFPE samples for research, especially in oncology, lies in their ubiquity and association with long-term clinical outcome data. Archival FFPE samples represent an invaluable resource for biomarker discovery and validation studies because they are routinely collected in clinical practice and can be linked to detailed patient records [1]. However, the very chemical reactions that confer preservation stability also fragment and cross-link RNA, making it challenging to obtain high-quality RNA for downstream applications like qPCR and RNA sequencing [2] [3]. Consequently, understanding formalin fixation chemistry is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for researchers aiming to extract biologically meaningful gene expression data from these sample types.

The Biochemistry of Formaldehyde Cross-linking

Fundamental Reaction Mechanisms

Formaldehyde, the smallest and most reactive aldehyde, functions as an effective cross-linking agent due to its high electrophilicity and small molecular size, enabling penetration throughout cellular compartments. Its reactivity primarily targets nucleophilic functional groups in biological macromolecules, including amino groups in nucleic acid bases and side chains of amino acids such as lysine, cysteine, histidine, tryptophan, and arginine [4].

The cross-linking process occurs through a two-step mechanism:

- Methylol Adduct Formation: A nucleophilic group (e.g., the primary amine from adenine or lysine) attacks the electrophilic carbonyl carbon of formaldehyde, forming an unstable methylol adduct (R-NH-CH₂-OH).

- Methylene Bridge Formation: The methylol adduct can rapidly dehydrate to form a reactive Schiff base (R-N=CH₂), which then reacts with a second nearby nucleophile (e.g., from a protein or another RNA molecule) to form a stable methylene bridge (R-NH-CH₂-N-R') [4].

Table 1: Nucleophilic Targets for Formaldehyde in Biological Systems

| Macromolecule | Reactive Groups | Primary Reaction Products |

|---|---|---|

| RNA | Exocyclic amines of adenine, guanine, cytosine | Methylol adducts, RNA-protein cross-links, RNA-RNA cross-links |

| Protein | Side chains of lysine, arginine, cysteine, histidine, tyrosine | Methylol adducts, protein-protein cross-links |

| DNA | Exocyclic amines of adenine, guanine, cytosine | Methylol adducts, DNA-protein cross-links, interstrand cross-links |

For RNA, these reactions result in two particularly detrimental consequences: (1) RNA-protein cross-links that physically trap RNA within protein complexes, and (2) RNA fragmentation due to the alkaline conditions often encountered during tissue processing. The formation of methylene bridges between RNA and surrounding proteins is the principal reason why RNA is difficult to extract quantitatively from FFPE samples [4] [5].

Mass Spectrometry Insights into Cross-link Chemistry

Recent advances in mass spectrometry (MS) have refined our understanding of formaldehyde cross-linking chemistry. Surprisingly, when analyzing structured proteins, the dominant reaction product adds 24 Da (two carbon atoms) to the total mass of two cross-linked peptides, rather than the 12 Da (one carbon atom) expected from a classic methylene bridge [5].

This 24 Da addition is now understood to be a dimerization product of two formaldehyde-induced amino acid modifications. MS/MS fragmentation patterns reveal that this cross-link cleaves symmetrically, producing a mass addition of 12 Da on each peptide. Lysine and arginine residues are the most prevalent participants in this reaction, though aspartic acid, tyrosine, and other residues also contribute significantly [5]. This revised mechanism enhances our ability to interpret cross-linking data and understand the molecular constraints imposed by formalin fixation.

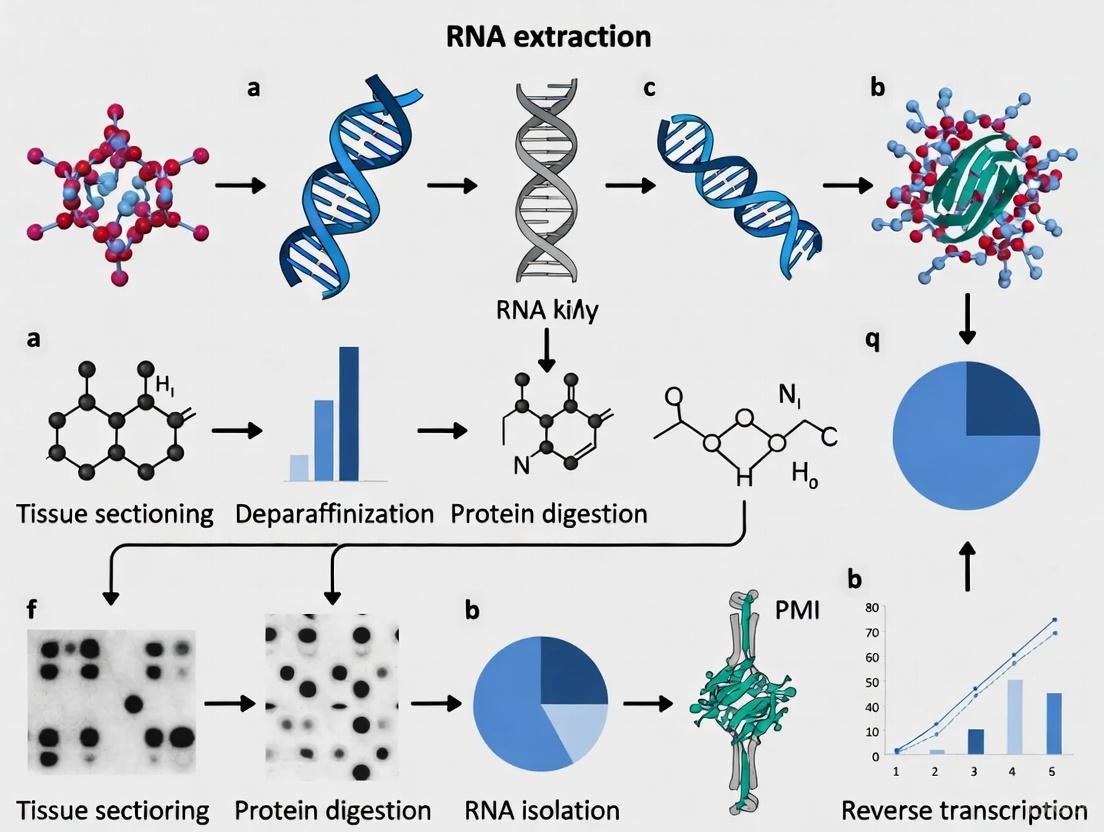

Diagram 1: Formaldehyde cross-linking involves a two-step reaction mechanism that results in stable methylene bridges between macromolecules.

Impact on RNA Integrity and Extraction from FFPE Samples

Chemical Consequences for RNA

The chemical modifications inflicted during formalin fixation have profound implications for RNA integrity:

- Fragmentation: RNA undergoes extensive strand breakage during fixation and storage. The DV200 metric (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides) is a critical quality indicator, with values below 30% indicating samples that may be unsuitable for many downstream applications [1] [3].

- Cross-linking: Covalent bonds formed between RNA and proteins create a physical barrier to extraction, effectively reducing yield by trapping RNA within an insoluble matrix.

- Base Modification: Chemical alteration of nucleotide bases (e.g., methylol adducts on adenine) can interfere with enzyme binding during reverse transcription and qPCR, leading to inaccurate quantification and potential sequence artifacts [4].

The extent of these damages is influenced by pre-analytical variables including fixation time, formalin pH and concentration, tissue size, and storage conditions of both blocks and sections. While FFPE blocks themselves are stable for decades, cut sections may experience antigenic degradation over time, though one proteomic study found no significant effect on protein identifications from sections stored for up to 48 weeks at either room temperature or -80°C [6].

Quantitative Assessment of RNA Quality

RNA extracted from FFPE samples is typically fragmented, as reflected in DV200 values. A comparative study of extraction kits found that quality scores varied significantly across different kits and tissue types [1]. The Promega ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA Miniprep System provided the best combination of both quantity and quality across tested tissue samples (tonsil, appendix, and lymphoma lymph nodes), while the Roche kit systematically provided better quality recovery than other kits [1].

Table 2: RNA Quality and Quantity Metrics from FFPE Extraction Studies

| Study / Sample Type | Extraction Method | Concentration Range | DV200 Range | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSCC FFPE Samples [3] | PureLink FFPE RNA Isolation Kit | >130 ng/µL | 30% - 50% | All samples met minimum quality thresholds for library prep despite degradation. |

| Melanoma FFPE Samples [2] | Not specified | 25 ng/µL - 374 ng/µL | 37% - 70% | No samples showed DV200 < 30%; all were usable for RNA-seq protocols. |

| Multi-tissue Comparison [1] | 7 Commercial Kits | Variable by kit and tissue | Variable by kit and tissue | Promega kit yielded highest quantity; Roche kit yielded superior quality. |

Experimental Protocols for RNA Analysis from FFPE Samples

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

Optimized RNA extraction from FFPE samples requires specialized protocols designed to reverse formalin cross-links while minimizing further RNA degradation:

Deparaffinization and Digestion Protocol [1] [7]:

- Cut 4-6 sections of 5-20 µm thickness from the FFPE block. Studies found that using six 8µm sections provided sufficient RNA yield without compromising quality [3].

- Deparaffinize using xylene, d-limonene, or commercial deparaffinization solutions. AutoLys M tubes combined with automated systems like KingFisher Duo provided effective deparaffinization with higher yield and consistency, particularly for small samples [7].

- Proteinase K Digestion: Incubate samples with proteinase K (typically 0.2 mg/mL) at 56°C for several hours to overnight to digest proteins and reverse cross-links. Some protocols incorporate Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER) by heating samples in citrate or Tris-EDTA buffer to further break cross-links [1].

- RNA Purification: Use silica membrane columns or magnetic beads to bind and wash RNA. Commercial kits like MagMAX FFPE DNA/RNA Ultra Kit are optimized for this purpose [7].

- Elution: Elute RNA in nuclease-free water or TE buffer.

Quality Assessment:

- Quantity: Measure RNA concentration using fluorescence-based methods (e.g., Qubit RNA HS Assay), as spectrophotometry (Nanodrop) may overestimate due to contaminants.

- Quality: Determine the DV200 index using a fragment analyzer or Bioanalyzer. Samples with DV200 > 50% are considered good quality, 30-50% are moderate quality, and <30% are heavily degraded [3].

- Functionality: For qPCR applications, include a test amplification of a control gene with varying amplicon lengths to assess degradation level and amplification efficiency.

Library Preparation Strategies for Sequencing

For comprehensive gene expression analysis, RNA sequencing library preparation from FFPE samples requires specialized approaches:

- rRNA Depletion: This method uses probes to remove abundant ribosomal RNAs, enriching for messenger RNA. However, with highly fragmented FFPE RNA, this approach may yield insufficient material for sequencing [3].

- Exome Capture: This approach involves preparing a cDNA library followed by target enrichment using hybridization probes. A comparative study on oral squamous cell carcinoma FFPE samples found that exome capture significantly outperformed rRNA depletion in library output concentration (p < 0.001) and generated more usable sequencing data from low-quality RNA [3].

Table 3: Comparison of Library Preparation Methods for FFPE-Derived RNA

| Parameter | rRNA Depletion | Exome Capture |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Removal of ribosomal RNA | Hybridization-based capture of coding regions |

| RNA Input | Higher (e.g., 750 ng) | Lower (e.g., 100 ng) |

| Best For | High-quality RNA (DV200 > 50%) | Low to moderate quality RNA (DV200 30-50%) |

| % mRNA Reads | Variable, often lower for FFPE | Higher (89.4% - 94.1% reported) [3] |

| Advantages | Broad transcriptome coverage | Higher specificity, better for degraded samples |

| Disadvantages | Inefficient with fragmented RNA | More complex workflow, sequence bias |

Diagram 2: Optimized workflow for RNA extraction from FFPE samples includes deparaffinization, digestion, quality control, and library preparation choices based on RNA quality.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Successful RNA analysis from FFPE samples requires carefully selected reagents and methods to overcome challenges posed by formalin fixation:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for FFPE RNA Analysis

| Reagent/Method | Function | Example Products | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deparaffinization Agents | Paraffin wax removal | Xylene, d-Limonene, commercial oils | d-Limonene is less hazardous than xylene; AutoLys M tubes effective in automated systems [7] |

| Lysis & Digestion Buffers | Reverse cross-links, digest proteins | Proteinase K, proprietary lysis buffers | Combination of enzymatic digestion and heat treatment most effective [1] |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Bind, wash, elute RNA | Promega ReliaPrep, Roche High Pure, MagMAX FFPE, PureLink FFPE | Selection depends on tissue type, sample size, and desired yield/quality balance [1] [7] [3] |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Evaluate RNA integrity | DV200, RQS (RNA Quality Score) | DV200 >30% essential for successful library prep; fluorescence-based quantification preferred [1] [3] |

| Library Prep Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries | NEBNext Ultra II, SMARTer Stranded | Exome capture superior for low-quality FFPE RNA [2] [3] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | cDNA synthesis | Thermostable, processive enzymes | Selected enzymes can overcome modified bases and cross-links for qPCR |

The fundamental chemistry of formalin fixation involves a complex series of reactions that create methylene bridges between RNA and proteins, severely impacting RNA integrity and extractability. These chemical modifications—including fragmentation, base alterations, and cross-linking—present significant but surmountable challenges for gene expression analysis from FFPE samples. Understanding these underlying mechanisms enables researchers to select appropriate countermeasures at each stage, from optimized extraction and quality control to judicious choice of library preparation methods. As mass spectrometry and other analytical techniques continue to refine our knowledge of formalin chemistry, further improvements in RNA recovery from these invaluable archival resources will enhance translational research capabilities, particularly in oncology and personalized medicine. By applying the principles and protocols outlined in this whitepaper, researchers can more effectively leverage the vast biobanks of FFPE samples for robust qPCR-based gene expression studies, bridging the gap between historical pathology specimens and modern molecular analysis.

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues represent an invaluable resource for biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, particularly in oncology. However, the RNA derived from these archival samples is subject to extensive degradation and chemical modification, posing significant challenges for downstream molecular analyses such as qPCR and RNA sequencing. This technical guide comprehensively outlines the primary sources of RNA degradation in FFPE tissues, drawing upon recent scientific literature to detail the molecular mechanisms of damage, standardized methods for RNA quality assessment, and optimized experimental protocols for RNA extraction and analysis. By synthesizing current evidence and providing practical recommendations, this review aims to equip researchers with the knowledge necessary to reliably utilize FFPE-derived RNA, thereby unlocking the vast potential of archival tissue banks for gene expression research.

Archival FFPE tissues represent one of the most abundant resources for retrospective clinical and research studies, with over a billion samples stored worldwide in hospital archives and tissue banks [1]. The ability to analyze gene expression from these specimens using techniques such as qPCR and RNA sequencing has transformative potential for understanding disease mechanisms, identifying biomarkers, and advancing drug development. However, the process of formalin fixation and paraffin embedding, along with subsequent long-term storage, introduces substantial challenges for nucleic acid preservation [8] [9].

RNA is particularly susceptible to degradation in FFPE tissues due to a combination of chemical modifications, fragmentation, and cross-linking. Formaldehyde fixation leads to nucleic acid fragmentation through hydrolysis of phosphodiester bonds and creates abasic sites via hydrolysis of N-glycosylic bonds [10]. Furthermore, formalin introduces methylol groups to nucleotides and creates methylene bridges between amino groups, leading to both intramolecular RNA modifications and RNA-protein cross-links that significantly impact downstream enzymatic processes [9] [10]. These alterations substantially reduce the ability of conventional molecular techniques to quantify mRNA accurately, making it difficult to analyze gene expression using fixed tissues [9].

Despite these challenges, methodological advances in RNA extraction, quality assessment, and analysis have made FFPE-derived RNA increasingly viable for research applications. This guide systematically addresses the key sources of RNA degradation in archival FFPE tissues and provides evidence-based strategies for mitigating these effects, with particular emphasis on optimization for qPCR-based research.

Molecular Mechanisms of RNA Degradation in FFPE Tissues

Chemical Modifications from Formalin Fixation

The formalin fixation process initiates a series of chemical modifications that profoundly impact RNA integrity. Formaldehyde reacts with RNA nucleotides through several mechanisms: addition of mono-methylol groups to bases, formation of methylene bridges between amino groups, and induction of strand breaks [9] [10]. These modifications occur because formaldehyde preferentially reacts with amino and imino groups of nucleic acid bases, particularly adenine and guanine, creating unstable methylol derivatives that can further react to form cross-links with proteins or other nucleic acids [10].

The cross-linking between RNA and proteins represents a particularly significant challenge, as it creates a physical barrier that limits the accessibility of RNA to enzymatic manipulation during extraction and subsequent molecular analyses [10]. These cross-links must be reversed through enzymatic digestion or heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) to liberate RNA fragments for analysis [1]. Proteinase K is commonly employed for this purpose, as it digests proteins and assists in breaking down the cross-links formed by formalin fixation [1].

RNA Fragmentation Processes

RNA isolated from FFPE specimens is substantially degraded to fragments typically under 300 nucleotides in length [9]. This fragmentation occurs through two primary mechanisms: hydrolysis of phosphodiester bonds in the RNA backbone and cleavage at abasic sites created by formalin modification [10]. The fragmentation pattern is not random, with certain RNA regions becoming more susceptible to degradation based on sequence composition and secondary structure.

The extent of fragmentation increases with the duration of formalin fixation. Prolonged fixation (longer than 48 hours) causes extensive degradation, cross-linking, and irreversible modifications to the RNA, resulting in reduction of quantifiable mRNA molecules [9]. This relationship underscores the importance of standardizing fixation protocols across samples to minimize variability in RNA quality.

Oxidative Damage During Storage

Long-term storage of FFPE tissues introduces additional RNA degradation through oxidative mechanisms. Exposure to oxygen during storage leads to oxidative deamination of bases, particularly affecting cytosine and adenine residues [11]. This process is accelerated by higher storage temperatures and exposure to light, making storage conditions a critical factor in preserving RNA integrity [11].

The storage of thin FFPE sections (typically 5-20μm) is especially problematic, as the increased surface area exposes RNA to greater environmental impacts, resulting in additional oxidative damage [11]. This effect is particularly relevant for clinical laboratories that pre-cut sections for future analyses, as the practice significantly compromises RNA quality compared to storing intact blocks.

Table 1: Major RNA Degradation Mechanisms in FFPE Tissues

| Degradation Mechanism | Chemical Process | Impact on RNA | Resulting Artifacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formalin Modification | Addition of methylol groups to nucleotides | Base alteration and miscoding | Reduced reverse transcription efficiency |

| Cross-linking | Methylene bridges between RNA and proteins | Physical trapping of RNA fragments | Inaccessible RNA targets; biased representation |

| Hydrolytic Fragmentation | Hydrolysis of phosphodiester bonds | RNA backbone cleavage | Short fragments (<300 nt); loss of full-length transcripts |

| Abasic Site Formation | Hydrolysis of N-glycosylic bonds | Loss of nucleotide bases | Strand breaks at abasic sites |

| Oxidative Damage | Oxidative deamination of bases | Base modifications and strand breaks | Sequence artifacts; reduced amplifiability |

Critical Factors Affecting RNA Quality in FFPE Tissues

Pre-analytical Variables: Fixation and Processing

Tissue processing conditions represent a major determinant of final RNA quality. The duration of formalin fixation significantly impacts RNA integrity, with longer fixation times leading to progressively greater degradation [9]. Standardization of fixation protocols is therefore essential for generating comparable results across samples. The size of tissue specimens also influences fixation efficiency, with larger blocks requiring longer fixation times that may exacerbate RNA degradation.

The chemical environment during fixation plays an important role in RNA preservation. Buffered formalin solutions (typically 10% neutral buffered formalin) provide better RNA preservation compared to unbuffered alternatives by maintaining a stable pH that minimizes acid-catalyzed hydrolysis [1]. The temperature during fixation and processing should be carefully controlled, as elevated temperatures can accelerate degradation processes.

Storage Conditions and Temporal Effects

Storage conditions for both FFPE blocks and tissue sections significantly impact RNA stability. A systematic evaluation of storage temperatures demonstrated that RNA integrity is best preserved at lower temperatures (-80°C > -20°C > 4°C > 24°C), with both total RNA concentration and the amount of long RNA fragments decreasing at higher storage temperatures [11]. This relationship highlights the importance of proper storage for maintaining RNA quality.

The age of FFPE blocks correlates with RNA degradation, though this relationship is not always linear [12]. Chemical modifications continue to occur gradually during storage, with older specimens typically exhibiting more extensive fragmentation. However, studies have successfully extracted usable RNA from blocks stored for up to 20-32 years, demonstrating that even decades-old material can yield valuable molecular data with appropriate methodologies [8] [13].

For tissue sections, storage with protective paraffin coating (paraffin dipping) provides superior preservation compared to uncoated sections, particularly for long-term storage [14]. This protective barrier minimizes exposure to oxygen and humidity, reducing oxidative damage and hydrolytic degradation.

Tissue-Specific Variability

Different tissue types exhibit varying susceptibilities to RNA degradation during FFPE processing. A systematic comparison of RNA recovery from tonsil, appendix, and lymphoma tissues demonstrated significant variability in both the quantity and quality of RNA obtained, even when using identical extraction methods and processing protocols [1]. This tissue-specific variability may reflect differences in intrinsic RNase content, cellular composition, lipid content, and tissue density that affect fixative penetration and processing.

Tissues with high endogenous RNase activity (such as pancreas and spleen) typically show more rapid degradation unless fixation occurs promptly after collection. Similarly, tissues with high lipid content may exhibit delayed fixative penetration, leading to ongoing autolytic processes before fixation is complete. These factors necessitate consideration of tissue-specific optimization when working with diverse sample types.

Table 2: Impact of Storage Conditions on RNA Quality Metrics

| Storage Condition | Effect on RNA Concentration | Effect on DV200 Values | Effect on Fragment Size Distribution | Recommended Practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact FFPE Blocks (RT) | Minimal decrease over years | Gradual decline with age | Progressive fragmentation | Store in climate-controlled environment with stable temperature and humidity |

| Uncoated Sections (4°C) | Moderate decrease over months | Significant decline after 36 weeks | Rapid fragmentation of long molecules | Limit section storage time; use within 6 months |

| Paraffin-coated Sections (4°C) | Minimal decrease over months | Stable for at least 36 weeks | Good preservation of fragments >200 nt | Apply protective paraffin coating for long-term storage |

| Sections (-80°C) | Minimal decrease | Highly stable | Optimal preservation of size distribution | Recommended for valuable or irreplaceable samples |

Quality Assessment and Metrics for FFPE-Derived RNA

RNA Integrity and Fragment Size Analysis

Quality assessment of FFPE-derived RNA requires specialized approaches, as conventional metrics developed for intact RNA are often inadequate. The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) commonly used for fresh frozen samples has limited utility for FFPE-RNA, as degraded samples typically yield very low RIN values (often 1.2-2.5) that do not necessarily correlate with analytical utility [10] [13].

The DV200 metric (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides) has emerged as a more reliable quality indicator for FFPE samples [8] [10] [12]. This metric provides a practical assessment of RNA fragment size distribution that better predicts downstream performance in qPCR and sequencing applications. For severely degraded samples with DV200 < 30%, the DV100 metric (percentage of fragments >100 nucleotides) may offer better discrimination for quality assessment [8].

Electropherogram visualization provides additional qualitative information beyond numerical metrics. The presence of high-molecular-weight species may indicate incomplete reversal of cross-links, while a smooth size distribution without distinct peaks suggests thorough extraction of fragmented RNA [10]. Visual inspection can thus complement quantitative metrics in determining RNA suitability for specific applications.

Functional Quality Assessment

Functional assessment through qPCR represents a critical complementary approach to physical RNA quality metrics. Amplification efficiency for specific target genes provides a direct measure of RNA suitability for gene expression analysis [9] [10]. This functional assessment is particularly important because chemical modifications from formalin fixation can inhibit reverse transcription and PCR amplification even when adequate RNA fragmentation is present.

When designing qPCR assays for FFPE-derived RNA, amplicon length represents a crucial consideration. Several studies have demonstrated that shorter amplicons (typically <100 bp) significantly increase detection sensitivity and reproducibility [9]. Designing assays to target the 3'-UTR of mRNA molecules can further enhance detection, as this region is often better preserved in degraded RNA [9].

The use of reference genes for normalization requires careful validation in FFPE samples, as degradation patterns may affect reference and target genes differently. Reference genes should demonstrate stable expression across sample groups and show minimal influence of degradation on measured expression levels [10].

Methodological Approaches for RNA Analysis from FFPE Tissues

RNA Extraction Optimization

The choice of RNA extraction method significantly impacts both the quantity and quality of RNA recovered from FFPE tissues. Systematic comparisons of commercial extraction kits have demonstrated substantial variability in performance, with different kits exhibiting strengths in RNA yield, quality, or both [1] [15]. Silica-based methods represent the most common approach, though paramagnetic beads-based methods have also shown excellent performance [1] [15].

Modifications to standard extraction protocols can enhance RNA recovery. Extending tissue lysis time (up to 10 hours) improves the efficiency of cross-link reversal, reducing high-molecular-weight species that represent incompletely liberated RNA [10]. Incorporating a heating step (70°C) during extraction increases RNA yields, potentially by further reversing formaldehyde adducts, without compromising quality metrics [10].

Deparaffinization represents another critical step where methodological choices impact RNA quality. While xylene has traditionally been used for this purpose, the environmentally friendly alternative d-limonene has demonstrated equivalent effectiveness while offering practical safety advantages [11].

Library Preparation Strategies for Sequencing

For RNA sequencing applications, the choice of library preparation method significantly influences data quality from FFPE-derived RNA. Methods that utilize random primers for cDNA synthesis generally outperform those relying on oligo-dT priming, as the poly-A tails necessary for oligo-dT priming are often degraded or modified in FFPE-RNA [8]. Total RNA sequencing approaches that incorporate ribosomal RNA depletion rather than poly-A selection typically provide more comprehensive transcriptome coverage from degraded samples [8] [2].

The required input RNA amount represents another important consideration, particularly for precious clinical samples with limited material. Recent methodological advances have enabled reliable sequencing from increasingly small RNA inputs, with some kits producing high-quality data from as little as 5-10ng of total RNA [2]. This capability is particularly valuable for samples where macrodissection or microdissection has been employed to isolate specific tissue regions.

qPCR Optimization Strategies

qPCR analysis of FFPE-derived RNA requires specific optimization to address the challenges of fragmentation and chemical modification. The most critical factor is designing short amplicons (typically 50-100 bp) to accommodate the fragmented nature of the RNA [9]. One study demonstrated successful mRNA quantification using amplicons as short as 24 nucleotides, highlighting the potential for extreme miniaturization of assay design [9].

Incorporating a pre-amplification step can enhance sensitivity for low-abundance targets, though this introduces additional variability that must be carefully controlled [9]. The use of random hexamers rather than gene-specific primers for reverse transcription improves coverage of degraded transcripts, as fragmentation sites that would prevent extension of a gene-specific primer may be bypassed with random priming [9].

RNA quantity and quality normalization present special challenges for FFPE samples. While spectrophotometric quantification is commonly used, fluorescence-based methods generally provide more accurate measurements for degraded RNA [13]. Some researchers advocate normalization approaches based on the mean expression of multiple reference genes rather than relying solely on RNA quantity metrics [10].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Recommended RNA Extraction Protocol

Based on comparative studies of extraction methods, the following protocol represents a robust approach for obtaining high-quality RNA from FFPE tissues:

Sectioning: Cut 5-20μm sections from FFPE blocks using a microtome. For best results, use freshly cut sections rather than stored sections when possible. Collect sections in nuclease-free tubes.

Deparaffinization: Add 1mL of xylene or d-limonene to the sections, vortex thoroughly, and incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes. Centrifuge at maximum speed for 5 minutes and carefully remove the supernatant. Repeat once with fresh xylene/d-limonene.

Ethanol Wash: Add 1mL of absolute ethanol to the pellet, vortex, and centrifuge at maximum speed for 5 minutes. Remove the supernatant completely. Air-dry the pellet for 5-10 minutes to residual ethanol.

Proteinase K Digestion: Resuspend the deparaffinized pellet in appropriate lysis buffer containing 1-2mg/mL Proteinase K. Incubate at 56°C for 10-16 hours with agitation to reverse cross-links and digest proteins.

RNA Isolation: Proceed with RNA isolation using a silica-column based method according to manufacturer's instructions. Include optional DNase digestion step to remove genomic DNA contamination.

Elution: Elute RNA in nuclease-free water rather than TE buffer, as EDTA can interfere with downstream enzymatic reactions.

Quality Assessment: Determine RNA concentration using fluorescence-based methods and assess RNA fragment size distribution using a bioanalyzer or fragment analyzer to calculate DV200 values.

Quality Control Workflow

RNA Quality Assessment Workflow for FFPE Tissues

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for FFPE RNA Analysis

| Reagent/Kits | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Considerations for FFPE Tissues |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen), miRNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen), ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA Miniprep (Promega) | Simultaneous DNA/RNA extraction, optimized for cross-link reversal | Consider yield/quality trade-offs; Promega kit showed best quantity/quality ratio in comparative studies [1] |

| Deparaffinization Reagents | Xylene, d-Limonene | Paraffin wax removal | d-Limonene offers environmental and safety advantages with comparable efficacy [11] |

| DNase Treatment Kits | RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen), TURBO DNase (Thermo Fisher) | Genomic DNA removal | Critical for accurate gene expression analysis; include on-column or in-solution treatment |

| Quality Assessment Kits | RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent), High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent) | RNA fragment size analysis | Essential for calculating DV200 metrics; requires bioanalyzer or fragment analyzer instrumentation |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher) | cDNA synthesis from degraded RNA | Use random hexamers rather than oligo-dT primers for better coverage of fragmented RNA |

| qPCR Master Mixes | TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Thermo Fisher), SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) | Quantitative PCR amplification | Optimized for short amplicons; TaqMan assays may offer better specificity for degraded samples |

Archival FFPE tissues represent an invaluable resource for biomedical research, particularly in molecular pathology and oncology. While RNA degradation presents significant challenges for gene expression analysis, understanding the key sources of this degradation enables researchers to implement appropriate countermeasures at each stage from tissue collection through molecular analysis. Through optimized RNA extraction methods, appropriate quality assessment metrics, and targeted analytical approaches such as short-amplicon qPCR assays, reliable gene expression data can be obtained from even highly degraded specimens. The continued refinement of these methodologies will further enhance the research utility of the vast archives of FFPE tissues available worldwide, enabling retrospective studies with long-term clinical outcome data that would otherwise not be feasible.

The analysis of gene expression from Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) samples represents a cornerstone of modern biomedical research, particularly in oncology and retrospective clinical studies. These archival tissues provide an invaluable resource for understanding disease progression and prognosis [16]. However, the chemical processes of formalin fixation induce nucleic acid modifications—including oxidation, cross-linking, and fragmentation—that profoundly compromise RNA integrity [16] [10]. This degradation poses significant challenges for downstream applications such as qPCR, where RNA quality directly impacts data reliability and experimental reproducibility.

For researchers working with FFPE samples for qPCR research, assessing RNA quality is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of experimental success. The choice of quality assessment method must align with the specific challenges posed by FFPE-derived RNA and the technical requirements of qPCR. Traditional quality measures developed for fresh or frozen tissues often fail to accurately represent the integrity of FFPE-derived RNA, necessitating specialized metrics and interpretive frameworks [17] [18]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the three fundamental RNA quality metrics—RIN, DV200, and absorbance ratios—within the specific context of FFPE sample research for qPCR applications.

Essential RNA Quality Metrics: Principles and Applications

RNA Integrity Number (RIN)

The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is an algorithm-based assessment of RNA quality developed for the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. This automated approach assigns RNA a integrity value from 1 (completely degraded) to 10 (perfectly intact) based on the entire electrophoretic trace of the RNA sample, with particular attention to the ribosomal RNA regions [19].

Mechanism and Interpretation: The RIN algorithm employs a combination of features from the electropherogram, including the total RNA ratio, 28S peak height, 28S area ratio, and the relationship between the 18S and 28S areas to the "fast region" (small fragments) [19]. In intact RNA from fresh or frozen tissues, the 28S:18S ribosomal ratio is approximately 2:1, yielding RIN values typically above 8.0 [17] [19]. However, formalin fixation fragments RNA and disrupts this ratio, making standard RIN interpretation problematic for FFPE samples [10] [18].

Limitations for FFPE Samples: Research demonstrates that RIN values alone do not adequately discern between low and high quality FFPE RNA or reliably predict qPCR success [18]. The fragmentation pattern of FFPE RNA differs fundamentally from fresh RNA degradation, with formalin-induced cross-links creating atypical electrophoregram profiles that compromise RIN accuracy [10].

DV200 Metric

The DV200 metric represents the percentage of RNA fragments longer than 200 nucleotides and has emerged as a more reliable quality indicator for FFPE-derived RNA [16] [18]. This metric directly addresses the fragmentation issue central to FFPE RNA quality assessment.

Principle and Measurement: DV200 is calculated from the size distribution of RNA fragments separated by capillary electrophoresis on platforms like the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. The metric quantifies the proportion of RNA molecules of sufficient length for downstream applications, with higher values indicating better preservation [16]. Studies have validated that DV200 shows stronger correlation with sequencing and qPCR outcomes from FFPE samples compared to RIN [18].

Quality Thresholds and Applications: For the NanoString nCounter platform, a robust and reliable gene expression analysis requires FFPE samples with DV200 values greater than 30% [16]. Illumina recommends that samples with DV200 below 70% require at least twice the normal RNA input for sequencing library preparation, while samples with DV200 below 30% should not be sequenced at all [18]. Research indicates that DV100 (percentage of fragments >100 nucleotides) values above 80% provide the best indication of successful gene detection in whole transcriptome studies [18].

Absorbance Ratios (A260/A280 and A260/A230)

Ultraviolet absorbance spectroscopy provides rapid assessment of RNA purity by detecting contaminants that compromise downstream reactions including qPCR [17].

A260/A280 Ratio: This ratio evaluates protein contamination, with optimal values of 1.8–2.2 indicating pure RNA [17]. Values below 1.8 suggest residual protein or guanidine salts from the extraction process, which can inhibit reverse transcriptase and PCR enzymes [17].

A260/A230 Ratio: This ratio assesses contamination from organic compounds such as phenol, guanidine, or ethanol, with values greater than 1.7 generally considered acceptable [17]. Low A260/A230 ratios indicate contaminants that may interfere with cDNA synthesis and qPCR amplification [17].

Limitations: Absorbance ratios provide no information about RNA integrity or fragmentation state [17]. Even severely degraded RNA samples can yield optimal absorbance ratios if purified effectively, making them insufficient standalone metrics for FFPE RNA quality [17].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of RNA Quality Metrics for FFPE Samples

| Metric | What It Measures | Optimal Range (FFPE) | Primary Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIN | Overall RNA integrity based on electrophoretic trace | >7.0 (if measurable) [19] | Initial quality screening; fresh/frozen RNA | Limited reliability for FFPE samples [18] |

| DV200 | % of fragments >200 nucleotides | >30% (minimal) [16]; >70% (good) [18] | FFPE-specific quality assessment; input normalization | Requires specialized equipment (Bioanalyzer/TapeStation) |

| A260/A280 | Protein contamination | 1.8–2.2 [17] | Purity assessment; detection of enzyme inhibitors | Does not detect RNA fragmentation [17] |

| A260/A230 | Organic compound contamination | >1.7 [17] | Detection of reverse transcription inhibitors | Does not detect RNA fragmentation [17] |

Experimental Protocols for RNA Quality Assessment

DV200 Determination Using Bioanalyzer

The following protocol outlines the standardized procedure for assessing RNA quality from FFPE samples using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, a critical workflow for determining DV200 values [16] [10].

Sample Preparation:

- Extract total RNA from FFPE tissue sections (10μm thickness) using specialized kits designed for FFPE tissues (e.g., Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE kit or Cell Data Sciences RNAstorm FFPE RNA extraction kit) [16].

- Determine RNA concentration using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop 2000). Record A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios for purity assessment [16].

- Dilute RNA samples to appropriate concentrations (typically 1-5 ng/μL) depending on the specific Bioanalyzer chip being used [10].

Bioanalyzer Procedure:

- Prepare the RNA Pico Chip according to manufacturer specifications: Prime the chip with gel-dye mix using the provided syringe [10].

- Load 1 μL of RNA marker into the designated wells [10].

- Pipette 1 μL of each RNA sample into separate sample wells, followed by 1 μL of RNA marker in each well [10].

- Vortex the chip for 1 minute using the provided IKA vortexer [10].

- Insert the chip into the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument and run the analysis using the RNA Pico program [10].

Data Interpretation:

- The software generates an electrophoretogram and calculates the DV200 value automatically [16].

- Visually inspect the electrophoretogram: high-quality FFPE RNA shows a relatively flat size distribution with fragments spanning 100-1000 nucleotides, while poor-quality samples show predominant short fragments (<200 nucleotides) [10].

- Use the DV200 value to determine RNA input requirements for downstream qPCR applications [16].

Absorbance Ratio Measurement Protocol

Spectrophotometric assessment of RNA purity provides critical information about contaminants that may inhibit qPCR reactions [17].

Sample Preparation:

- Isolate RNA from FFPE samples using specialized kits that effectively remove paraffin and reverse formalin cross-links [16] [15].

- Elute RNA in nuclease-free water or TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) to maintain stable pH for accurate A260/A280 ratios [17].

- For samples with very low yields, consider fluorescent dye-based quantification methods (e.g., Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA Assay) with greater sensitivity [17].

Measurement Procedure:

- Initialize the spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) and establish baseline correction with the appropriate blank solution (typically the RNA elution buffer) [17].

- Apply 1-2 μL of RNA sample to the measurement pedestal and perform absorbance scanning from 320nm to 230nm [17].

- Record the following measurements: RNA concentration (derived from A260), A260/A280 ratio, and A260/A230 ratio [17].

- Clean the measurement surfaces thoroughly between samples to prevent carryover contamination [17].

Troubleshooting:

- Low A260/A280 (<1.8): Repeat purification with proteinase K treatment or additional phenol-chloroform extraction [17].

- Low A260/A230 (<1.7): Implement additional wash steps with 70% ethanol during RNA purification or consider ethanol precipitation to remove guanidine salts [17].

Integrated Quality Assessment Workflow for FFPE Samples

Diagram 1: RNA Quality Assessment Workflow for FFPE Samples. This integrated approach combines purity, integrity, and functional assessments to ensure reliable qPCR results.

Research Reagent Solutions for FFPE RNA Quality Control

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for RNA Quality Assessment

| Reagent/Equipment | Primary Function | Example Products | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFPE RNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid isolation with cross-link reversal | Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE kit; Cell Data Sciences RNAstorm FFPE RNA extraction kit [16] | Include proteinase K digestion; optimized for fragmented RNA |

| Microspectrophotometers | RNA concentration and purity measurement | NanoDrop 2000 [16] | Requires minimal sample volume (1-2 μL); provides A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios |

| Capillary Electrophoresis Systems | RNA integrity and fragment size analysis | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA Pico chips [16] [10] | Essential for DV200 calculation; different chips for varying concentration ranges |

| Fluorometric Quantitation Kits | Highly sensitive RNA quantification | QuantiFluor RNA System; Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA Assay [17] | More sensitive than absorbance methods; useful for low-yield samples |

| qPCR QC Assays | Functional assessment of RNA quality | Reference gene amplification with 5' vs 3' amplicon comparison [10] | Evaluates amplification efficiency; detects reverse transcription inhibitors |

The reliable assessment of RNA quality from FFPE samples requires an integrated approach that combines multiple complementary metrics. While RIN provides valuable information for intact RNA, its utility for FFPE samples is limited, making DV200 the preferred integrity metric for formalin-fixed materials [18]. Absorbance ratios remain essential for detecting contaminants that inhibit enzymatic reactions in qPCR workflows [17].

For researchers conducting qPCR studies with FFPE samples, the following strategic approach is recommended: (1) begin with spectrophotometric analysis to ensure sample purity; (2) proceed to fragment analysis (DV200) to determine RNA integrity and appropriate input amounts; (3) implement functional QC using qPCR with control genes to verify amplifiability [10] [18]. This multi-layered quality assessment strategy maximizes the value of precious FFPE samples and ensures the generation of reliable, reproducible gene expression data for drug development and clinical research applications.

Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissue samples represent an invaluable resource for biomedical research, particularly in oncology and drug development, with over a billion specimens archived worldwide [1] [13]. These archives, often linked to extensive clinical data, provide unprecedented opportunities for retrospective studies and biomarker discovery. The ability to extract quality RNA from these specimens for downstream applications like qPCR and next-generation sequencing has become a critical component of modern translational research. However, the utility of FFPE-derived RNA is profoundly influenced by pre-analytical variables that occur during tissue collection, processing, and storage. This technical guide examines the impact of three fundamental pre-analytical factors—fixation time, storage duration, and tissue type—within the broader context of optimizing RNA extraction methods from FFPE samples for qPCR research, providing evidence-based recommendations for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Impact of Fixation Time on RNA Quality and Quantity

Formalin fixation preserves tissue architecture by creating methylene bridges between proteins and nucleic acids, but this process simultaneously compromises RNA integrity. The duration of formalin exposure represents a critical determinant in the quality of recoverable RNA for molecular analyses.

Experimental Evidence on Fixation Duration

A controlled investigation examined the effects of 24-hour versus 72-hour formalin fixation on RNA parameters using matched tissue samples. Despite significantly reduced RNA quality in formalin-fixed tissues compared to fresh frozen controls, the study demonstrated that RT-qPCR values remained comparable across all groups (P value = 0.00002) [20]. This finding confirms that while extended fixation damages RNA integrity, the remaining fragments can still yield reliable qPCR results, which is particularly relevant for clinical samples with standardized fixation protocols.

The molecular degradation mechanism involves formaldehyde-induced cross-linking and RNA fragmentation, which occurs progressively during fixation. While short fixation periods (24 hours) cause moderate fragmentation, extended fixation (72 hours) significantly reduces amplifiable fragment lengths, though the impact on targeted qPCR assays targeting short amplicons may be minimal [20] [21].

Practical Recommendations for Fixation

Standardized fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 18-48 hours is recommended as the optimal window for balancing morphological preservation and molecular integrity [1] [22]. This timeframe minimizes over-fixation artifacts while maintaining RNA in a state suitable for subsequent qPCR analysis.

Effects of Storage Duration on FFPE RNA Integrity

The long-term storage potential of FFPE blocks makes them particularly valuable for retrospective studies, yet storage duration introduces additional considerations for RNA quality.

Quantitative Assessment of Storage Impacts

A systematic evaluation of FFPE breast tissue specimens revealed a significant inverse correlation between storage time and RNA yield (r = -0.38, P = 0.01) [23]. This progressive degradation occurs despite the protective paraffin embedding, suggesting that slow oxidative damage and residual nuclease activity continue even in archived blocks.

However, practical applications demonstrate that properly stored FFPE blocks can retain usable RNA for extended periods. Studies have successfully extracted viable RNA from specimens stored for 10-20 years, though with expected reductions in quality metrics [13]. The DV200 values (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides) show marked decline with increasing storage duration, falling to a median of just 18.65% in long-term archived specimens [13].

Storage Condition Recommendations

Optimal preservation requires storage at stable room temperature (not exceeding 25°C) with protection from humidity and light [1] [22]. Under these conditions, FFPE blocks can yield serviceable RNA for qPCR analysis even after decades of storage, making them viable for long-term retrospective studies.

Tissue-Type Specific Considerations in RNA Recovery

Different tissue types present unique challenges for RNA extraction due to variations in cellular composition, endogenous nuclease levels, and structural properties.

Comparative Performance Across Tissues

A comprehensive evaluation of seven commercial RNA extraction kits across three tissue types (tonsil, appendix, and lymph node with B-cell lymphoma) revealed significant disparities in both quantity and quality of recovered RNA [1]. Despite standardized processing protocols, tissue-specific factors influenced extraction efficiency, with the Promega ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA miniprep system demonstrating superior performance for the tested tissue types in both yield and quality metrics.

The structural and biochemical composition of different tissues affects how formalin penetrates and fixes the tissue, subsequently influencing RNA preservation. Tissues with high lipid content or dense connective tissue elements may require protocol modifications to ensure adequate yields [1].

Implications for Experimental Design

Researchers should conduct pilot extractions when working with new tissue types to establish baseline expectations for RNA yield and quality. The DV200 metric provides a valuable quality indicator, with values >50% considered good, 30-50% acceptable for targeted applications, and <30% indicating heavily degraded samples [13] [3].

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Pre-analytical Variables on RNA from FFPE Samples

| Pre-analytical Variable | Experimental Conditions | Impact on RNA Yield | Impact on RNA Quality | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation Time | 24 hours vs. 72 hours in formalin | Satisfactory quantity in both groups | Significantly reduced quality in both vs. fresh frozen, but RT-qPCR still comparable | [20] |

| Storage Duration | 1-3 years vs. <1 year | Significant inverse correlation (r = -0.38, P = 0.01) | Progressive degradation; DV200 declines with time | [23] |

| Storage Duration | 1-20 years | Average yield: 401.8 ng/cm² tissue; no significant correlation with storage time | Median DV200: 18.65% (wide variation: 1.48%-71.47%) | [13] |

| Tissue Type | Tonsil, appendix, B-cell lymphoma lymph node | Significant variation across tissue types despite identical processing | Quality differences observed; performance kit-dependent | [1] |

Table 2: RNA Quality Thresholds for Downstream Applications

| Quality Metric | High Quality | Moderate Quality | Low Quality | Unacceptable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV200 Value | >70% | 50-70% | 30-50% | <30% |

| Recommended Applications | All NGS applications, microarray | Targeted NGS, qPCR arrays | qPCR (short amplicons) | Not recommended for molecular analysis |

| RIN Value | >7 | 5-7 | <5 | Not applicable for FFPE |

Detailed Experimental Methodology for Assessing Pre-analytical Variables

RNA Extraction and QC Protocol

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for evaluating pre-analytical variables in FFPE tissues:

Tissue Processing and Sectioning:

- Cut tissue specimens into approximately 0.5 × 1 × 1 cm blocks [1]

- Fix in 10% neutral buffered formalin for standardized durations (18-48 hours recommended) [22]

- Process through graded alcohols (50%, 70%, 90%, 100%) for 45 minutes each [20]

- Clear in xylene grades (50%, 90%, 100%) for 30 minutes each [20]

- Embed in paraffin using standard histological protocols

- Section at 5-20 µm thickness depending on extraction method [20] [22]

RNA Extraction Using TRIzol Method:

- Deparaffinize sections with xylene (2-3 repetitions) [20]

- Rehydrate through graded ethanol series (100%, 90%, 70%, 50%, 30%) [20]

- Add 500 µL TRIzol reagent and store at -80°C overnight [20]

- Homogenize at 4-8 RPM at 4°C [20]

- Add 100 µL chloroform, vortex vigorously, and centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C [20]

- Transfer aqueous phase to new tubes, add equal volume isopropanol and 1 µL glycogen [20]

- Centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C [20]

- Wash pellet with 80% ethanol in DEPC water, air-dry, and resuspend in DEPC water [20]

Quality Assessment:

- Quantify RNA using Nanodrop spectrophotometer [20] [22]

- Assess quality using Agilent TapeStation for RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or DV200 values [20] [13]

- For qPCR applications, prioritize DV200 over RIN for quality assessment [13]

cDNA Synthesis and qPCR Optimization

cDNA Synthesis:

- Use 5 µg mRNA for cDNA conversion [20]

- Include DNase I treatment (0.5 µL enzyme + 0.5 µL buffer) at 37°C for 10 minutes [20]

- Add random hexamers (1 µL) and dNTPs (1 µL), incubate at 65°C for 5 minutes [20]

- Add 5x prime buffer (4 µL), mRNase inhibitor (0.5 µL), and reverse transcriptase (1.0 µL) [20]

- Consider gene-specific primers for reverse transcription to improve qPCR sensitivity [24]

qPCR Optimization:

- Design primers to generate short amplicons (≤161 bp) for degraded RNA [23]

- Validate primer specificity with melting curve analysis [23]

- Use SYBR Green or TaqMan chemistry with appropriate controls

- Normalize data using stable reference genes (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin) [20]

Visualizing Pre-analytical Variable Impacts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Relationship between pre-analytical variables and RNA quality parameters, highlighting how fixation time, storage duration, and tissue type collectively influence RNA yield and quality, ultimately determining suitability for downstream applications.

Diagram 2: Optimized workflow for RNA extraction from FFPE samples and subsequent qPCR analysis, highlighting key steps for overcoming challenges posed by pre-analytical variables including overnight protein digestion and use of gene-specific primers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for FFPE RNA Extraction and qPCR

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | PureLink FFPE RNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen), ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA Miniprep (Promega), AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen) | Nucleic acid isolation from FFPE tissues | Promega kit showed best quantity/quality ratio in systematic comparisons [1] |

| Deparaffinization Agents | Xylene, proprietary oils (kit-specific) | Paraffin removal from tissue sections | Xylene effective but requires proper ventilation; proprietary alternatives safer [1] |

| Digestion Enzymes | Proteinase K | Digests cross-linked proteins to release RNA | Overnight digestion significantly increases RNA yield [24] |

| Reverse Transcriptase Kits | RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit | cDNA synthesis from extracted RNA | Gene-specific primers improve qPCR detection sensitivity [24] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green, TaqMan assays | Target amplification and detection | SYBR Green with melt curve analysis verifies specificity [23] |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Agilent TapeStation, Nanodrop, Qubit Fluorometer | RNA quantity and quality measurement | DV200 more meaningful than RIN for FFPE samples [13] |

The reliability of RNA extracted from FFPE samples for qPCR research is fundamentally influenced by pre-analytical variables including fixation time, storage duration, and tissue type. Evidence indicates that while extended formalin fixation beyond 24-48 hours and prolonged storage reduce RNA integrity, these challenges can be mitigated through optimized protocols including extended proteinase K digestion, appropriate RNA extraction methods, and targeted qPCR approaches using short amplicons. Tissue-specific variations necessitate validation of extraction protocols for different sample types. By systematically addressing these pre-analytical factors through the methodologies and recommendations outlined in this guide, researchers can maximize the utility of invaluable FFPE archives for robust gene expression analysis in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Practical RNA Extraction and qPCR Workflows: From Kit Selection to Amplification

Systematic Comparison of Commercial FFPE RNA Extraction Kits

Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissue samples represent one of the most valuable resources for biomedical research, with over a billion samples stored in hospitals and tissue banks worldwide [1]. These samples are routinely used for diagnostic purposes in oncology and other fields. However, extracting high-quality RNA from FFPE samples remains technically challenging due to formalin-induced cross-linking, fragmentation, and other chemical modifications that occur during the fixation and preservation process [1] [15]. These challenges can negatively impact the reliability of downstream applications such as RT-qPCR and next-generation sequencing (NGS).

The development of commercial RNA extraction kits specifically designed for FFPE samples has made the process more straightforward and reproducible. Nevertheless, these kits vary considerably in their efficiency for different tissue types in terms of both the quantity and quality of RNA recovered [1] [25]. This systematic comparison aims to provide researchers with evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate RNA extraction methods for their FFPE samples, particularly in the context of qPCR research.

Comparative Performance of Commercial Kits

Experimental Design and Methodology

A comprehensive study directly compared seven commercially available RNA extraction kits using identical FFPE samples from three different tissue types: tonsils from patients with tonsillitis, appendices from patients with appendix inflammation, and lymph nodes from patients with B-cell lymphoma [1] [26]. The study employed a rigorous experimental design where 20 µm thick slices were systematically distributed across collection tubes to avoid regional biases in cell type or abundance. Each of the seven kits was used according to the manufacturer's instructions, with each sample tested in triplicate, resulting in a total of 189 extractions [1].

The kits evaluated in this systematic comparison included:

- RNeasy FFPE (Qiagen)

- ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA Miniprep System (Promega)

- Norgen FFPE RNA Purification (Norgen Biotek)

- GenElute FFPE RNA Purification (Sigma-Aldrich)

- PureLink FFPE RNA Isolation (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

- AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE (Qiagen)

- High Pure FFPET RNA Isolation (Roche) [26]

RNA quantity was assessed using spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 8000), while RNA quality was evaluated using two metrics: RNA Quality Score (RQS) and DV200, both measured using a nucleic acid analyzer (Perkin Elmer) [1]. The RQS is an integrity metric on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 representing intact RNA and 1 representing highly degraded RNA. The DV200 represents the percentage of RNA fragments longer than 200 nucleotides, with higher values indicating better sample quality [1] [25].

Quantitative and Qualitative Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics across the seven evaluated extraction kits:

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Metrics of Commercial FFPE RNA Extraction Kits

| Extraction Kit | Maximum Yield Performance | Mean RQS | Mean DV200 (%) | Quality × Quantity Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ReliaPrep FFPE (Promega) | Best for all tonsils, all lymph nodes, and 1/3 appendices | High | High | Significantly higher than all other kits (P<0.002) |

| PureLink FFPE (Thermo Fisher) | Best for 2/3 appendix specimens | Highest overall mean RQS | High | High |

| High Pure FFPET (Roche) | Moderate | High | Highest overall DV200 | High |

| RNeasy FFPE (Qiagen) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE (Qiagen) | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| GenElute FFPE (Sigma-Aldrich) | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Norgen FFPE (Norgen Biotek) | Low | Low | Low | Low |

The Promega ReliaPrep kit provided significantly higher RNA quantity than all other kits when all specimen types were considered together (P<0.00001 to P<0.01 depending on the comparison) [26]. In terms of quality, the PureLink FFPE RNA Isolation Kit had the highest mean RQS when all specimens were considered, significantly outperforming the ReliaPrep system (P<0.01) [26]. For DV200 values, the High Pure FFPET RNA Isolation Kit yielded the highest mean percentage of fragments >200 nucleotides, though the difference was not significant when compared to the ReliaPrep system [26].

When all factors (yield, RQS, and DV200) were considered together, the Roche High Pure FFPET RNA Isolation Kit was identified as the most consistent performer, though the Roche, Thermo Fisher, and Promega kits all performed well [26]. However, the Promega ReliaPrep system yielded a significantly higher quality × quantity score (relative yield × DV200) than any other kit evaluated (P<0.002 for all comparisons) [26].

Tissue-Specific Variations in Kit Performance

The study revealed notable tissue-specific variations in kit performance. While the Promega ReliaPrep kit provided the maximum RNA recovery for all three tonsil specimens and all three lymph node specimens, for two of the three appendix specimens, the Thermo Fisher PureLink kit performed better than other kits [1] [26]. This finding highlights that optimal kit selection may depend on the specific tissue type being studied, possibly due to differences in RNAse activity across various tissue types [25].

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Performance Variations of Top-Performing Kits

| Tissue Type | Best Yield Performance | Best RQS Performance | Best DV200 Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tonsil | ReliaPrep (Promega) | PureLink (Thermo Fisher) for 2/3 specimens | High Pure (Roche), PureLink (Thermo Fisher), and ReliaPrep (Promega) showed comparable high DV200 |

| Appendix | PureLink (Thermo Fisher) for 2/3 specimens | High Pure (Roche) for 1/3 specimens, comparable RQS for PureLink and High Pure for others | High Pure (Roche) for 2/3 specimens |

| Lymph Node | ReliaPrep (Promega) | High Pure (Roche) for 1/3 specimens, comparable RQS for ReliaPrep and High Pure for others | High Pure (Roche) and ReliaPrep (Promega) showed highest DV200 |

Protocol Modifications and Optimization Strategies

Kit-Specific Protocol Adjustments

Research indicates that protocol modifications beyond the manufacturer's recommendations can significantly improve RNA yield and quality. A study comparing four RNA extraction methods on FFPE cardiac tissue found that simple adjustments to wash steps and incubation times markedly enhanced outcomes [25].

For the Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE kit, modifying the ethanol wash step after deparaffinization from a single wash to three sequential washes (twice in 96-100% ethanol and once in 70% ethanol) with 2-minute centrifugation at each step improved RNA quality as measured by DV200 values [25]. Similarly, for the CELLDATA RNAstorm kit, extending the lysis incubation time from 2 hours to 24 hours at 72°C significantly increased the proportion of extracts with DV200 values above 30% [25].

Another study utilizing the RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation kit (Ambion) found that adding an extra washing step with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) after sample rehydration with absolute ethyl alcohol significantly improved both RNA quantity and quality, leading to better amplification success in downstream PCR applications [27].

Impact of Extraction Methods on Downstream Applications

The choice of RNA extraction method significantly impacts the success of downstream applications like qPCR and RNA sequencing. Research has demonstrated that RNA extraction methodology affects both preanalytical quality metrics and sequencing-based gene expression results [15]. Studies have found that silica-based and isotachophoresis-based extraction procedures show differences in uniquely mapped reads, detectable genes, duplicate read fractions, and representation of complex genetic elements like the B-cell receptor repertoire [15].

For qPCR applications specifically, implementing gene-specific reverse transcription instead of whole transcriptome priming improved sensitivity by a considerable 4.0-fold increase (equivalent to 2.0 PCR cycles earlier detection) [28]. Targeted cDNA preamplification provided the most substantial improvement in qPCR sensitivity, enabling earlier detection by an average of 172.4-fold (7.43 PCR cycles) [28]. These optimization strategies are particularly valuable when working with FFPE samples where RNA quantity and quality are often limiting factors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for FFPE RNA Extraction and Analysis

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K | Digests proteins and assists in breaking crosslinks formed by formalin fixation | Widely used enzyme in FFPE RNA extraction protocols [1] |

| Xylene | Deparaffinization of FFPE tissue sections | Used when deparaffinization solution not included in kit [1] [25] |

| DNase I | Degrades genomic DNA during RNA extraction | Prevents DNA contamination in downstream applications [25] |

| RNAse Inhibitors | Prevents RNA degradation during processing | Essential for maintaining RNA integrity [28] |

| MS2 Phage RNA | Control for assessing specificity in preamplification | Helps identify non-specific amplification products [28] |

| Specific Enzymes/Buffers | Reverse formalin crosslinks (e.g., sodium borohydride) | Breaks formaldehyde crosslinks by reducing Schiff bases [1] |

Experimental Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for systematic comparison of FFPE RNA extraction kits:

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for FFPE RNA Extraction Kit Comparison

The decision pathway for selecting an optimal FFPE RNA extraction method can be visualized as follows:

Figure 2: Decision Pathway for FFPE RNA Extraction Method Selection

Based on the systematic comparison of seven commercial FFPE RNA extraction kits, the following recommendations can be made for researchers conducting qPCR studies:

For maximum RNA yield: The Promega ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA Miniprep System provides significantly higher RNA recovery than other kits, particularly for tonsil and lymph node tissues.

For optimal RNA quality: The Thermo Fisher PureLink FFPE RNA Isolation Kit delivers the highest mean RNA Quality Score (RQS), while the Roche High Pure FFPET RNA Isolation Kit yields the highest DV200 values.

For balanced performance: The Promega ReliaPrep system provides the best combined quality × quantity score, making it an excellent choice when both high yield and good quality are important.

For protocol optimization: Consider implementing modified wash steps (for Qiagen kits) or extended lysis incubation (for CELLDATA kits) to improve RNA quality metrics.

For tissue-specific studies: Evaluate kit performance with your specific tissue type, as performance variations across different tissues were observed.

For downstream qPCR applications: Implement gene-specific reverse transcription and targeted cDNA preamplification to significantly improve detection sensitivity when working with FFPE-derived RNA.

The optimal choice of extraction kit ultimately depends on the specific research requirements, tissue type, and downstream applications. Researchers are encouraged to validate selected methods with their own FFPE samples before committing to large-scale studies.

Step-by-Step Optimized RNA Extraction Protocol for FFPE Tissues

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues represent an invaluable resource for biomedical research, particularly in retrospective studies that correlate molecular findings with long-term clinical outcomes [29] [10]. These archives contain vast amounts of pathologically significant specimens from diverse patient populations, offering unprecedented opportunities for biomarker discovery and validation [30] [31]. However, the formalin fixation and paraffin embedding processes introduce significant challenges for nucleic acid extraction, especially for RNA. Formaldehyde creates methylol groups and methylene bridges that cross-link nucleic acids and proteins, while paraffin embedding at elevated temperatures causes RNA aggregation and fragmentation [32] [33]. These chemical modifications result in highly fragmented RNA, typically degraded to less than 300 base pairs, with poor yields that hinder downstream applications like qPCR and next-generation sequencing [32] [33].

Despite these challenges, methodological advances have demonstrated that reliable gene expression analysis from FFPE tissues is achievable with proper optimization [29] [10] [31]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive, optimized protocol for RNA extraction from FFPE samples, specifically framed within the context of preparing high-quality template for qPCR-based research. By implementing these standardized procedures, researchers can unlock the potential of invaluable archival specimens for robust molecular analysis.

Critical Factors Affecting RNA Quality from FFPE Tissues

Pre-Analytical Variables

Multiple pre-analytical factors significantly impact the quantity and quality of RNA obtainable from FFPE tissues. The pre-fixation period (time between tissue collection and formalin immersion) is critical, as biochemical degradation begins within minutes of hypoxia [33]. Fixation conditions including duration, temperature, and formalin concentration must be controlled; extended fixation beyond 24-48 hours progressively destroys nucleic acids through cross-linking [33]. Archiving time also influences RNA quality, showing a negative correlation with RNA integrity, though proper experimental design can overcome this effect, with samples up to 10 years old successfully yielding amplifiable RNA for qPCR [29].

Tissue processing methods before fixation substantially impact outcomes. Specimens stored refrigerated for extended periods before fixation or fixed without proper slicing showed lower success rates in downstream applications [29]. The paraffin embedding process itself has been identified as a major contributor to RNA damage, with heating RNA in hydrocarbon solvent at 60°C for 1 hour causing significant reduction in amplifiable RNA and creating high-molecular-weight aggregates [32].

Comparative Analysis of RNA from Different Stabilization Methods

Understanding how FFPE-derived RNA compares to other stabilization methods informs realistic expectations for downstream applications:

Table 1: RNA Quality Metrics Across Stabilization Methods

| Stabilization Method | Average RIN | Amplifiable Fragment Size | Suitability for qPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNAlater | 7.6 | >400 bp | Excellent |

| Snap Freezing (SF) | 5.2 | ~400 bp | Good |

| SF with OCT | 8.1 | >400 bp | Excellent |

| FFPE | 1.4 | <300 bp | Limited (requires optimization) |

Data adapted from comparative studies on human lung tissue [34]. FFPE-derived RNA consistently shows the lowest RNA Integrity Number (RIN) values, reflecting extensive fragmentation. Despite this, with proper targeting of short amplicons (<100 bp), reliable qPCR results can be obtained [34].

Optimized Step-by-Step RNA Extraction Protocol

Tissue Section Preparation and Deparaffinization

Sectioning: Cut 4-6 sections of 10-20 μm thickness from FFPE blocks using a microtome. For small lesions, additional sections may be necessary to obtain sufficient material [29] [31]. Place sections into RNase-free 1.5-2.0 mL microtubes.

Deparaffinization: Add 1 mL xylene to each tube. Vortex vigorously and incubate at 50°C for 5 minutes. Centrifuge at maximum speed for 5 minutes and carefully discard supernatant. Repeat this process once to ensure complete paraffin removal [33].

Washing and Rehydration: Add 1 mL absolute ethanol to the pellet, vortex, and centrifuge for 5 minutes. Discard supernatant and repeat with 85% and 70% ethanol sequentially. After the final ethanol wash, dry the pellet completely at room temperature or in a 37°C incubator for 10-15 minutes [33].

PBS Washing (Critical Enhancement): Resuspend the pellet in 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), vortex, incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes, and centrifuge at full speed for 5 minutes. This step removes potential PCR inhibitors and formalin residues, significantly improving subsequent amplification efficiency [33].

Protein Digestion and RNA Extraction

Proteinase K Digestion: Digest the tissue pellet using 200-400 μg/mL Proteinase K in the appropriate buffer supplied with the extraction kit. Incubate at 60°C for 30 minutes, followed by overnight incubation at 60°C [24]. This extended digestion is crucial for reversing formalin-induced cross-links and efficiently releasing RNA from the tissue matrix.

Optional Homogenization (Yield Enhancement): For particularly fibrous or difficult tissues, employ mechanical disruption using a microHomogenizer (mH) device. Integrate two cycles of two-minute homogenization at 6 volts after the Proteinase K digestion step. This approach can increase RNA yield approximately 3-fold while maintaining RNA quality [30].

RNA Isolation: Isolate RNA using commercial kits specifically designed for FFPE tissues (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy FFPE Kit or MasterPure Complete RNA Purification Kit). The MasterPure kit has demonstrated superior yields for renal tumor tissues [24]. Follow manufacturer protocols with these modifications: