Molecular Docking in Cancer Research: A Comprehensive Guide to Target Discovery and Drug Design

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular docking's transformative role in modern cancer research and drug discovery.

Molecular Docking in Cancer Research: A Comprehensive Guide to Target Discovery and Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular docking's transformative role in modern cancer research and drug discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of how computational docking predicts interactions between small molecules and cancer-related protein targets. The scope spans from core methodologies and search algorithms to practical applications in targeting specific cancers like breast cancer and disrupting cancer stem cell metabolism. It further addresses critical challenges in clinical translation, validation strategies to enhance predictive accuracy, and the emerging integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning to overcome current limitations. This resource synthesizes the full spectrum of docking applications, offering both a primer for newcomers and advanced insights for seasoned practitioners in the field of computational oncology.

The Foundation of Molecular Docking in Oncology: From Basic Principles to Cancer Target Identification

Molecular docking has become an indispensable tool in modern computational drug discovery, providing critical insights into intermolecular interactions. In the context of cancer research, it enables scientists to rapidly identify and optimize potential therapeutic compounds by predicting how small molecules bind to cancer-related protein targets, thus accelerating the development of targeted therapies.

Core Principles and Definition

At its core, molecular docking is a computational method that predicts the preferred orientation and conformation of a small molecule (a ligand) when bound to a larger macromolecular target (a receptor, typically a protein) to form a stable complex [1]. The process simulates a natural biological event where molecules interact within cells within seconds to form stable complexes that are crucial for signal transduction and other cellular processes [1].

The primary goal is to predict the binding pose (the three-dimensional orientation of the ligand in the binding site) and the binding affinity (the strength of the interaction), which helps researchers identify compounds likely to exhibit favorable binding energies, making them potential drug candidates [1]. This is particularly valuable in cancer research for understanding receptor dynamics, protein-ligand interactions, and biomolecular pathways involved in cancer progression [2].

Key Methodological Approaches

Molecular docking methodologies can be broadly classified based on how they treat the flexibility of the interacting molecules. The choice of approach involves a trade-off between computational cost and predictive accuracy.

Classification of Docking Methods

The table below summarizes the main types of molecular docking approaches.

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Docking Methods

| Method Type | Flexibility Considered | Key Characteristics | Common Algorithms/Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid Docking [1] | Neither ligand nor receptor | Treats both molecules as static, fixed shapes. Computationally efficient but less accurate as it ignores internal degrees of freedom. | Early DOCK algorithms |

| Flexible Ligand Docking [1] | Ligand only | Accounts for the conformational flexibility of the ligand, which is crucial for accurate pose prediction. More computationally demanding than rigid docking. | AutoDock, AutoDock Vina, GOLD |

| Flexible Receptor Docking (Induced Fit) | Receptor side chains or full backbone | Allows for conformational changes in the receptor upon ligand binding, providing a more realistic simulation. Highly computationally intensive. | GLIDE, MOE, Schrödinger Suite |

The Docking Workflow

A standard molecular docking protocol involves several sequential steps, each critical for obtaining reliable results:

- Ligand Preparation: The small molecule's structure is optimized, which includes adding hydrogens, assigning partial charges, and minimizing its energy to ensure a realistic starting conformation [1].

- Receptor Preparation: The protein structure, often obtained from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB), is prepared by adding hydrogen atoms, correcting residue protonation states, and removing water molecules (unless they are critical for binding) [1]. The quality of the receptor structure significantly influences the docking results [1].

- Binding Site Identification: The specific region on the receptor where the ligand is expected to bind must be defined. This can be a known active site (e.g., the ATP-binding pocket in kinases) or predicted using computational methods [3].

- Pose Generation (Search Algorithm): The docking algorithm generates a large number of possible ligand conformations and orientations within the defined binding site. This is typically achieved using various search strategies [1]:

- Genetic Algorithms: Mimic natural selection to evolve populations of ligand poses toward an optimal solution (used in GOLD).

- Monte Carlo Methods: Randomly sample ligand conformations and accept or reject them based on a probabilistic criterion.

- Fragment-Based Methods: Build ligand poses within the binding site by connecting small molecular fragments (used in FlexX).

- Pose Scoring and Ranking (Scoring Function): Each generated pose is evaluated and assigned a score representing its predicted binding affinity. Scoring functions generally fall into three categories [1]:

- Force Field-Based: Calculate energy based on molecular mechanics terms (van der Waals, electrostatic).

- Empirical: Use parameterized functions derived from experimental binding affinity data.

- Knowledge-Based: Derive potentials from statistical analyses of atom-pair frequencies in known protein-ligand complexes.

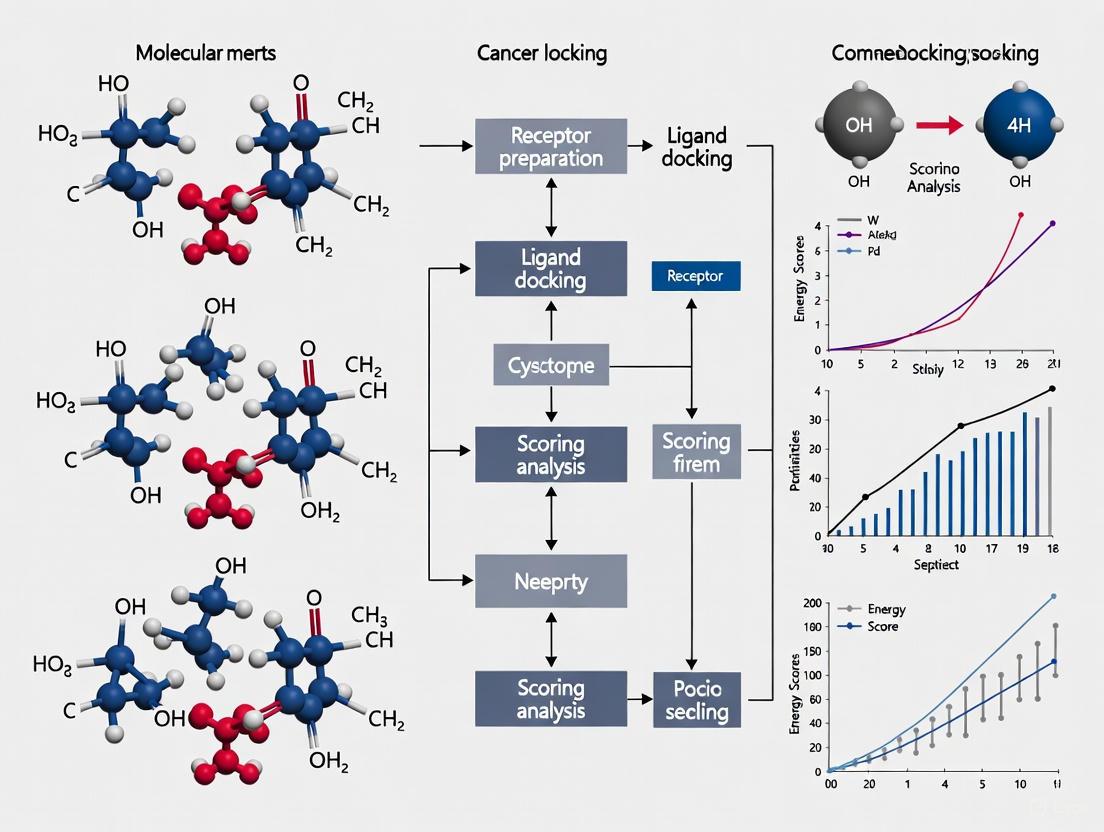

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for a molecular docking simulation, highlighting the key preparatory and computational stages.

Successful molecular docking relies on a suite of software tools, databases, and computational resources. The table below catalogs the essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Docking

| Category | Item/Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Tools | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, GLIDE, MOE [1] | Core docking programs for pose prediction and scoring. |

| GROMACS, Desmond [4] [3] | Molecular dynamics software for simulating the stability and dynamics of docked complexes. | |

| PyMol, VMD [3] | 3D visualization tools for analyzing protein-ligand interactions and simulation trajectories. | |

| Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, essential for obtaining receptor coordinates. |

| PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL [1] | Databases of small molecule structures and their biological activities for ligand sourcing and virtual screening. | |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster [3] | Necessary for running computationally intensive docking and molecular dynamics simulations. |

| NVIDIA Quadro/GeForce GPUs [3] | Graphics processing units that accelerate molecular visualization and certain calculation steps. |

Applications in Cancer Research: A Case Study on Breast Cancer

Molecular docking plays a transformative role in oncology, particularly in the development of targeted therapies for breast cancer. It is frequently integrated with other computational and experimental methods in a multidisciplinary strategy that may include omics technologies, bioinformatics, and network pharmacology [5].

A representative study by Bao et al. investigated the natural compound Formononetin (FM) for liver cancer treatment. The workflow exemplifies a modern, integrated approach [5]:

- Target Screening: Network pharmacology was used to screen the action targets of FM.

- Data Analysis: Differentially expressed genes in liver cancer were analyzed using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database.

- Molecular Docking: Docking simulations evaluated how well FM binds to its predicted targets.

- Validation: The stability of FM binding to a key target, glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), was confirmed through metabolomics and molecular dynamics simulation.

- Experimental Confirmation: Laboratory tests finally showed that FM induces ferroptosis, inhibiting liver cancer progression [5].

Another study focused on identifying therapeutic targets for breast cancer combined bioinformatics, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Researchers screened 23 compounds and identified the adenosine A1 receptor as a key target. After molecular docking and MD simulations confirmed stable binding for a lead compound (Compound 5), a novel molecule (Molecule 10) was rationally designed. This molecule exhibited potent antitumor activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells with an IC₅₀ value of 0.032 µM, significantly outperforming the positive control 5-FU [3].

Figure 2: An integrated computational and experimental workflow for anti-cancer drug discovery, demonstrating the role of molecular docking within a broader pipeline.

Advanced Protocols: Integrating Docking with Molecular Dynamics

While docking provides a static snapshot, integrating it with Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations offers a dynamic view of the binding process and stability, addressing a key limitation of docking alone [6]. The following protocol is adapted from recent studies on breast cancer biomarkers and serine/threonine kinases [4] [6] [3].

Detailed Protocol for MD Simulation of a Docked Complex

Objective: To assess the stability and dynamic interactions of a pre-docked protein-ligand complex (e.g., Berberine bound to BCL-2) over a simulated timeframe.

Materials & Software:

- Software: GROMACS 2020.3 or Desmond [3] [4].

- Force Fields: AMBER99SB-ILDN for proteins [3]; GAFF for small molecules [3].

- Initial Structure: The coordinates of the best-docked pose from your molecular docking run.

Methodology:

System Setup:

- Place the docked complex in the center of a cubic box with a minimum distance of 0.8 nm between the complex and the box edge.

- Solvate the system with a water model, such as TIP3P [3].

- Add ions (e.g., Na⁺ or Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's net charge and simulate a physiological ion concentration.

Energy Minimization:

- Run an initial energy minimization step (e.g., using steepest descent algorithm) to relieve any steric clashes or strained geometry introduced during system building. This ensures the system starts from a stable, low-energy state.

Equilibration:

- Perform a two-step equilibration in the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles.

- During a 150 ps simulation, gently restrain the heavy atoms of the protein-ligand complex, allowing the solvent and ions to relax around them. Maintain temperature at 298.15 K and pressure at 1 bar using thermostats (e.g., Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover) and barostats [3].

Production MD Run:

- Conduct an unrestricted MD simulation for a defined period (e.g., 100 ns) [4] using a time step of 0.002 ps (2 fs). This step captures the natural dynamics of the complex without restraints.

Trajectory Analysis:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Calculate the RMSD of the protein backbone and the ligand relative to the starting structure. A stable or convergent RMSD profile indicates a stable complex [4] [3].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Analyze RMSF to determine the flexibility of individual protein residues. This can identify regions that become more rigid or flexible upon ligand binding.

- Hydrogen Bond Analysis: Quantify the number and occupancy of hydrogen bonds between the ligand and the protein throughout the simulation. Persistent interactions indicate key binding residues [4].

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite its utility, molecular docking faces several challenges that impact its clinical adoption. Accuracy and validation remain significant hurdles, as docking protocols can misidentify binding sites, generate inconsistent poses, or produce high docking scores that fail during subsequent MD simulations or experimental testing [2]. The accuracy of these tools can vary dramatically, with reported accuracies ranging from 0% to over 90% [2].

A major limitation is the treatment of flexibility and solvation. Traditional docking often struggles to fully account for the conformational flexibility of the receptor and the complex role of water molecules in binding [2] [6]. Furthermore, scoring functions are not always reliable for predicting absolute binding affinities, leading to potential false positives and negatives [2] [1].

The future of molecular docking lies in its integration with advanced computational techniques. The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is set to revolutionize the field by improving scoring functions, enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space, and facilitating de novo molecular design [5] [2] [1]. Emerging trends also point toward the use of more sophisticated hybrid quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) methods for modeling critical interactions like covalent bonding and charge transfer, as well as the application of these tools for designing complex molecules such as PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) that induce targeted protein degradation [6]. As these methods mature, they will further solidify molecular docking's role as a cornerstone of rational drug design in cancer therapeutics and beyond.

The pursuit of targeted cancer therapies represents a paradigm shift from conventional cytotoxic treatments to the strategic disruption of specific molecular entities that drive oncogenesis. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical exploration of six critical cancer targets—Estrogen Receptor (ER), Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2), Cyclin-Dependent Kinases 4/6 (CDK4/6), Murine Double Minute 2 (MDM2), Poly (ADP-ribose) Polymerase 1 (PARP1), and Cancer Stem Cell (CSC) markers—within the context of modern computational drug discovery. Molecular docking has emerged as a pivotal structure-based computational technique that accelerates the identification and optimization of inhibitors against these targets by predicting ligand-receptor interactions with minimal free energy, thereby forming a crucial component of the oncology drug development pipeline [7] [8].

Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) and Their Markers

Biological and Clinical Significance

Cancer stem cells constitute a highly plastic, therapy-resistant subpopulation within tumors that drives tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and relapse [9]. These cells demonstrate remarkable self-renewal capacity and ability to create heterogeneous tumor cell populations, leading to intratumoral complexity that complicates treatment approaches [9] [10]. CSCs evade conventional therapies through multiple mechanisms including enhanced DNA repair, drug efflux pumps, quiescence, and interactions with their microenvironment [9]. Their ability to survive treatment and persist in a dormant state frequently causes cancer recurrence, as even a few remaining CSCs can regenerate tumors, often in more aggressive forms [9] [10].

Key CSC Markers and Isolation Challenges

CSC identification relies heavily on cell surface markers, though these markers vary significantly across tumor types and lack universal specificity. Table 1 summarizes prominent CSC markers, their functions, and associated malignancies.

Table 1: Key Cancer Stem Cell Markers and Characteristics

| Marker | Marker Type | Primary Functions | Associated Cancers |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | Surface marker | Cell adhesion, migration, metastasis activation | Breast, prostate, lung [8] |

| CD133 | Surface marker | Plasma membrane organization, lipid structure conservation | Brain, colon, breast, prostate [9] [10] |

| ALDH | Intracellular enzyme | Detoxification, differentiation regulation, retinoic acid production | Breast, lung, ovarian [10] |

| CD34+/CD38- | Surface marker combination | Leukemia initiation, self-renewal | Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) [9] [10] |

| LGR5 | Surface receptor | Wnt signaling regulation, stemness maintenance | Gastrointestinal cancers [9] |

A significant challenge in CSC research is the absence of universal biomarkers. Markers such as CD44 and CD133 are not exclusive to CSCs and are often expressed in normal stem cells or non-tumorigenic cancer cells [9]. Furthermore, CSC phenotypes demonstrate considerable plasticity, transitioning between states in response to environmental stimuli such as hypoxia, inflammation, or therapeutic pressure [9] [10]. This dynamic nature suggests CSCs represent a functional state rather than a fixed subpopulation, necessitating context-specific approaches for their identification and targeting [9].

Estrogen Receptor (ER)

Biological Role and Significance in Cancer

The Estrogen Receptor is a nuclear transcription factor that exists in two primary subtypes, ERα and ERβ, which play crucial roles in regulating differentiation, growth, and metabolic homeostasis [11]. Upon activation by its natural ligand 17β-estradiol, ER undergoes conformational changes, dimerizes, and translocates to the nucleus where it binds to Estrogen Response Elements (EREs) in target gene promoters, recruiting co-activators or co-repressors to modulate transcription [11]. ERα signaling particularly drives proliferation in hormone-responsive breast cancers, making it a prognostic marker and therapeutic target [11].

Molecular Docking Applications and Experimental Protocols

Molecular docking studies have revealed how selective compounds differentially target ER subtypes. Research demonstrates that the phytoestrogen genistein exhibits higher affinity for ERβ compared to ERα, with docking analyses showing that while genistein-ERα interaction requires less energy (-216.18 kJ/mol versus -213.62 kJ/mol for ERβ), the genistein-ERβ interaction forms two hydrogen bonds and four hydrophobic bonds with amino acid residues Lys304, Val485, Met296, Thr299, Val485, and Leu490, resulting in a more stable and effective interaction [11].

Table 2: Molecular Docking Interactions of Estrogen Receptor Ligands

| Ligand | Receptor | Binding Energy | Key Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17β-estradiol | ERα | -218.31 kJ/mol | Hydrophobic bonds with ARG261, PHE310, LEU311 [11] |

| Genistein | ERα | -216.18 kJ/mol | No stable bonds formed [11] |

| 17β-estradiol | ERβ | -207.90 kJ/mol | Hydrophobic bonds with MET296, THR299, LYS300, ASP303, VAL485 [11] |

| Genistein | ERβ | -213.62 kJ/mol | 2 hydrogen bonds, 4 hydrophobic bonds with LYS304, VAL485, MET296, THR299, VAL485, LEU490 [11] |

Experimental Protocol for ER Docking:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain ERα (GI: 11907837) and ERβ (GI: 2970564) sequences from NCBI. Generate 3D structures using SWISS-MODELLER via homology modeling and validate with Ramachandran Plot analysis [11].

- Ligand Preparation: Retrieve ligand structures (genistein CID: 5280961, 17β-estradiol CID: 5757) from PubChem. Convert SDF files to PDB format using OpenBabel software [11].

- Docking Computation: Perform docking simulations using HEX 8.0 software with a three-stage protocol: rigid-body energy minimization, semi-flexible repair, and finishing refinement in explicit solvent [11].

- Interaction Analysis: Visualize results with Discovery Studio 4.1 and LigPlot+. Analyze hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces. Perform pharmacophore analysis to identify residues involved in interactions [11].

Diagram 1: ERβ-Genistein-eNOS Transcriptional Activation Pathway. Genistein selectively binds ERβ, recruiting eNOS which translocates to the nucleus and activates genes regulating apoptosis (BCLX, Casp3), proliferation (CyclinD1), and telomere activity (hTERT) [11].

HER2 (Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2)

Biological Role and Significance in Cancer

HER2 is a receptor tyrosine kinase responsible for approximately 20% of breast cancer cases and is associated with aggressive disease progression [12]. HER2 overexpression has also been linked to adenocarcinomas of the ovary, endometrium, cervix, and lung [12]. When overexpressed, HER2 forms heterodimers with other EGFR family members, activating downstream signaling pathways including PI3K/AKT and MAPK that drive uncontrolled proliferation, survival, and metastasis [12] [13].

Molecular Docking Applications and Experimental Protocols

Virtual screening of natural compound libraries against HER2 has identified promising inhibitors with potential therapeutic value. Studies screening 80,617 natural compounds from the ZINC database identified top candidates ZINC43069427 and ZINC95918662 with binding energies of -11.0 kcal/mol and -8.50 kcal/mol respectively, superior to control compound Lapatinib (-7.65 kcal/mol) [12]. Similarly, alkaloids from Mitragyna speciosa (Korth.), Mitragynine and 7-Hydroxymitragynine, demonstrated binding energies of -7.56 kcal/mol and -8.77 kcal/mol with HER2, interacting with key residues including Leu726, Val734, Ala751, Lys753, Thr798, and Asp863 [13].

Experimental Protocol for HER2 Docking:

- Protein Preparation: Obtain HER2 crystal structure (PDB ID: 3PP0) from Protein Data Bank. Repair missing side chains using Swiss-PDB Viewer and save in PDB format [12].

- Compound Screening: Download natural compound libraries in SDF format. Apply Lipinski's Rule of Five and additional filters (Ghose, Veber, Egan, Muegge) using SWISS-ADME server to select drug-like compounds [12].

- Docking Validation: Validate docking protocol by redocking control ligands (Lapatinib, Afatinib, Sapitinib) against HER2 active site. Confirm common interactions with residues Leu726, Val734, Ala751, Lys753, Thr798, Gly804, Arg849, Leu852, Thr862, and Asp863 [12].

- Multiple Ligand Docking: Conduct docking simulations using AutoDock in PyRx environment. Set grid box of 25×22×19Å around the active site. Analyze RMSD, lowest energy conformers, and hydrogen bond interactions [12].

- Molecular Dynamics: Perform 50ns MD simulations using GROMACS v5.1 with SPC water model and GROMOS96 53a6 force field. Analyze RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and SASA to evaluate complex stability [12].

CDK4 and CDK6

Biological Role and Significance in Cancer

Cyclin D-dependent kinases CDK4 and CDK6 regulate progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle in a retinoblastoma protein (Rb)-dependent manner [14]. Upon activation by D-type cyclins, CDK4/6 phosphorylates Rb, leading to release of E2F transcription factors that initiate S-phase entry [14]. This cell cycle checkpoint is frequently dysregulated in cancer, making CDK4/6 attractive therapeutic targets. FDA approval of palbociclib in combination with letrozole for breast cancer treatment validates CDK4/6 as clinically relevant targets [14].

MDM2

Biological Role and Significance in Cancer

MDM2 (HDM2 in humans) is the primary cellular inhibitor of the p53 tumor suppressor, forming an autoregulatory feedback loop [15]. MDM2 binds p53's transactivation domain, exports it from the nucleus, and functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase to promote proteasomal degradation [15]. In approximately 50% of cancers retaining wild-type p53, MDM2 overexpression effectively inhibits p53 function, enabling unchecked proliferation [15].

Molecular Docking Applications

The structural basis of MDM2-p53 interaction is well characterized, with a hydrophobic surface pocket in MDM2 accommodating four key hydrophobic residues in p53 (Phe19, Leu22, Trp23, and Leu26) [15]. This defined interaction interface has enabled structure-based design of small-molecule inhibitors including Nutlins (cis-imidazoline derivatives) and spiro-oxindoles (MI-63, MI-219) that disrupt the MDM2-p53 interaction [15]. These inhibitors bind MDM2 with high affinity (Ki = 36 nM for Nutlin-3; 5 nM for MI-219), activating p53 pathway in tumor cells and inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis without genotoxic effects [15].

Diagram 2: MDM2-p53 Regulatory Loop and Therapeutic Intervention. p53 transactivates MDM2, which in turn degrades and inhibits p53. Small-molecule inhibitors block this interaction, stabilizing p53 and activating tumor suppressor functions [15].

PARP1

Biological Role and Significance in Cancer

PARP1 plays a pivotal role in DNA damage repair, particularly in the base excision repair (BER) and single-strand break repair (SSBR) pathways [16]. Upon detecting DNA damage, PARP1 catalyzes poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of target proteins, recruiting DNA repair proteins to damage sites [16]. PARP inhibitors (PARPis) trap PARP1 on DNA, preventing repair and causing replication fork collapse that leads to double-strand breaks [16]. In BRCA-mutated cancers deficient in homologous recombination repair, PARP inhibition creates synthetic lethality, providing a therapeutic window [16].

Advancements in Targeting Approaches

Current clinically approved PARPis inhibit both PARP1 and PARP2, but emerging evidence indicates that PARP2 inhibition contributes to hematological toxicity while synthetic lethality in BRCA-mutated cancers depends primarily on PARP1 [16]. This has prompted development of next-generation PARP1-selective inhibitors with improved safety profiles and reduced toxicity [16]. These selective inhibitors maintain efficacy while potentially addressing limitations of current PARPis, including toxicity, resistance development, and lack of optimal combination partners [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Target Identification and Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| SWISS-MODELLER | Protein 3D structure prediction via homology modeling | Generating 3D structures of ERα, ERβ, and eNOS for docking studies [11] |

| HEX 8.0 Software | Protein-ligand docking simulations | Determining binding orientations and energies of genistein with ER subtypes [11] |

| AutoDock/PyRx | Multiple ligand docking against target receptors | High-throughput screening of natural compound libraries against HER2 [12] |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulations | Evaluating stability of protein-ligand complexes over 50ns simulations [12] |

| SWISS-ADME Server | Pharmacokinetic prediction and drug-likeness screening | Applying Lipinski's Rule of Five and other filters to compound libraries [12] |

| ZINC Database | Repository of commercially available compounds | Source of 80,617 natural compounds for virtual screening [12] |

| Discovery Studio | Visualization and analysis of molecular interactions | Examining hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions in protein-ligand complexes [11] |

The strategic targeting of ER, HER2, CDK4/6, MDM2, PARP1, and CSC markers represents a sophisticated approach to modern oncology drug development. Molecular docking serves as an indispensable computational bridge between target identification and therapeutic implementation, enabling rapid screening and optimization of potential inhibitors against these well-validated targets. As structural biology and computational methodologies continue to advance, the integration of molecular docking with experimental validation will remain fundamental to developing next-generation cancer therapeutics with enhanced specificity and reduced off-target effects. The ongoing challenge remains in addressing tumor heterogeneity, plasticity, and resistance mechanisms—particularly in CSC populations—which will require increasingly sophisticated multi-target approaches and combination therapies.

Molecular docking has emerged as an indispensable computational technique in modern structure-based drug discovery, playing a pivotal role in the development of targeted cancer therapies. This method computationally predicts the optimal binding orientation and affinity of small molecule ligands to their biomolecular targets, primarily proteins [7]. The fundamental premise of docking lies in simulating the molecular recognition process that occurs when a potential drug compound interacts with a specific protein binding site, enabling researchers to identify and optimize compounds with enhanced specificity for cancer-related targets while minimizing off-target effects that contribute to toxicity [7].

The growing importance of molecular docking stems from its ability to revolutionize cancer treatment by accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic agents and improving clinical outcomes [7]. As an interdisciplinary tool that integrates principles from structural biology, computational chemistry, and bioinformatics, docking provides researchers with a powerful means to screen vast chemical libraries in silico, significantly reducing the time and resources required for initial drug discovery phases [7]. By facilitating the rational design of compounds that precisely target cancer-promoting proteins, molecular docking represents a paradigm shift from traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies toward more selective treatment approaches that exploit the unique molecular vulnerabilities of cancer cells.

Computational Methodologies and Workflows

Fundamental Principles and Algorithms

Molecular docking operates on the principle of predicting the binding conformation and association strength between two molecules through computational sampling and scoring. The process involves systematically positioning the ligand (potential drug compound) within the binding site of the target protein and evaluating the interaction using scoring functions that estimate the binding free energy [7]. These scoring functions typically incorporate various energy terms, including van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, desolvation penalties, and entropy changes, to rank potential binding poses and predict binding affinities [17].

The docking workflow generally follows a sequential process beginning with target and ligand preparation, followed by conformational sampling, pose prediction, and scoring. Advanced docking algorithms employ various search methods, including systematic searches, stochastic algorithms like genetic algorithms or Monte Carlo simulations, and fragment-based approaches to efficiently explore the vast conformational space of the ligand-receptor complex [17]. The accuracy of these predictions is critically dependent on the quality of the input structures, the parameterization of the scoring function, and appropriate treatment of solvent effects and molecular flexibility.

Technical Workflow for Molecular Docking

The following diagram illustrates the standard computational workflow for molecular docking studies in cancer drug discovery:

Key Software and Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Software Tools for Molecular Docking in Cancer Research

| Software/Tool | Primary Function | Key Features | Application in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [18] | Molecular docking | Fast gradient optimization, empirical scoring function | Predicting ligand binding to cancer targets like kinases |

| PyMOL [18] [19] | Molecular visualization | Structure analysis, binding pose visualization | Analyzing protein-ligand interactions post-docking |

| AutoDock Tools [19] | Preparation & parameterization | File format conversion, charge calculation | Preparing protein and ligand structures for docking |

| GROMACS [19] | Molecular dynamics | Simulation of biomolecular systems | Validating docking stability over time |

| OpenEye Toolkits [17] | High-throughput docking | Large-scale virtual screening | Screening compound libraries against multiple cancer targets |

| SWISS-ADME [20] | Pharmacokinetic prediction | ADMET property profiling | Evaluating drug-likeness of candidate compounds |

Application in Targeted Cancer Therapy Development

Enhancing Therapeutic Specificity

Molecular docking significantly enhances therapeutic specificity through precise target engagement prediction. By computationally modeling interactions at atomic resolution, researchers can design compounds that selectively bind to mutated or overexpressed proteins in cancer cells while sparing normal cellular counterparts [7]. This approach is particularly valuable for targeting specific oncogenic drivers, such as kinases, transcription factors, and regulatory proteins that maintain the malignant phenotype [21].

A compelling example of this specificity emerges from studies on Bcl-2 inhibitors for cancer therapy. Research on 1,3,5-trisubstituted-1H-pyrazole derivatives demonstrated how molecular docking confirmed high binding affinity to Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein frequently overexpressed in various cancers [21]. The docking results revealed key hydrogen bonding interactions that enabled structure-based optimization of these compounds, resulting in enhanced specificity for Bcl-2 and subsequent activation of apoptotic pathways in cancer cells [21]. Similarly, in ovarian cancer research, docking studies with columbianetin acetate (a compound from Angelica sinensis) identified specific interactions with core targets including ESR1, GSK3B, and JAK2, providing mechanistic insights for its selective anti-cancer effects [18].

Toxicity Reduction Strategies

The predictive capability of molecular docking directly contributes to toxicity reduction in cancer therapy by identifying and eliminating compounds with potential off-target effects early in the drug discovery pipeline. By screening candidate molecules against both intended targets and structurally similar off-target proteins, researchers can prioritize compounds with cleaner interaction profiles, thereby minimizing adverse effects associated with promiscuous binding [7] [17].

Integrating ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling with docking studies further enhances toxicity prediction. For instance, in the development of 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives as tubulin inhibitors for breast cancer therapy, comprehensive computational analyses including QSAR modeling and ADMET prediction were combined with molecular docking to identify compounds with optimal efficacy and safety profiles [20]. This integrated approach allowed researchers to evaluate not only binding affinity to tubulin but also potential toxicity risks, enabling the selection of candidates with reduced likelihood of causing adverse effects in subsequent clinical development [20].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Docking Results in Recent Cancer Drug Discovery Studies

| Study Focus | Cancer Type | Key Targets | Best Docking Score (kcal/mol) | Experimental Validation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbianetin acetate [18] | Ovarian cancer | ESR1, GSK3B, JAK2 | Favorable binding confirmed | In vitro cell proliferation and apoptosis assays | Frontiers in Oncology (2025) |

| 1,3,5-trisubstituted-1H-pyrazole [21] | Multiple cancers | Bcl-2 | High affinity through hydrogen bonding | Cytotoxicity tests (IC50: 3.9-35.5 μM), DNA damage assessment | RSC Advances (2025) |

| 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives [20] | Breast cancer | Tubulin (Colchicine site) | -9.6 (Pred28 compound) | Anti-proliferative activity on MCF-7 cells | Scientific Reports (2024) |

| Acrylamide exposure [19] | Breast cancer | EGFR, FN1, JUN, COL1A1 | Stable binding confirmed | Molecular dynamics (200 ns), immunohistochemistry | Scientific Reports (2025) |

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Standardized Docking Protocol for Cancer Targets

A comprehensive molecular docking study follows a rigorous, multi-step protocol to ensure reliable and reproducible results. The following methodology represents a consolidated approach adapted from recent high-impact cancer drug discovery studies [18] [19]:

Target Protein Preparation: Retrieve the three-dimensional crystal structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). Remove water molecules, ions, and native ligands using molecular visualization software such as PyMOL. Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define atom types using preparation tools like AutoDock Tools. Save the processed protein structure in PDBQT format for docking simulations [18].

Ligand Compound Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of small molecule ligands from databases such as PubChem or TCMSP. Optimize geometry using density functional theory (DFT) with B3LYP functional and 6-31G basis set when precise electronic properties are required [20]. Add hydrogen atoms, calculate Gasteiger charges, and define rotatable bonds. Export ligands in PDBQT format following the same parameterization as the target protein [19].

Binding Site Definition and Grid Generation: Identify the binding site coordinates from co-crystallized ligands or through computational binding site prediction algorithms. Define a grid box large enough to accommodate ligand flexibility while centered on the binding site. Typical grid dimensions of 60×60×60 points with 0.375 Å spacing provide sufficient resolution for comprehensive sampling [18].

Docking Execution and Parameters: Perform docking simulations using validated programs such as AutoDock Vina or OpenEye suite. Apply search parameters that balance computational efficiency with thorough conformational sampling, such as 50-100 independent docking runs per ligand with an exhaustiveness value of 32-64 [17]. For high-throughput virtual screening, implement hierarchical protocols with rapid initial filtering followed by more rigorous refinement of top hits [17].

Post-Docking Analysis: Cluster resulting poses by root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and select representative conformations from each cluster. Analyze protein-ligand interactions, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and π-π stacking. Calculate binding energies and rank compounds based on docking scores. Visualize optimal binding poses using molecular graphics software [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Docking-Guided Experimental Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Experimental Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Cell Lines [18] [20] | MCF-7 (breast), A2780 (ovarian), A549 (lung), PC-3 (prostate) | In vitro cytotoxicity assessment | Validating anti-proliferative effects of docked compounds |

| Cell Viability Assays [18] | CCK-8, MTT, colony formation | Quantifying cell proliferation and IC50 determination | Dose-response analysis of top-ranked compounds from docking |

| Apoptosis Assays [21] | Caspase-3 activation, Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, Annexin V staining | Measuring programmed cell death induction | Confirming mechanism predicted by docking to apoptotic targets |

| Protein Expression Analysis [19] | Western blot, immunohistochemistry, ELISA | Evaluating target protein modulation | Verifying engagement with intended docking targets |

| DNA Damage Assessment [21] | Comet assay, γH2AX staining | Detecting genotoxic stress | Identifying unintended toxicity of docked compounds |

| Molecular Dynamics Systems [19] | GROMACS with Amber-ff99SB force field | Simulating protein-ligand complex stability | Validating docking poses over extended timescales (100-200 ns) |

Case Studies in Cancer Drug Discovery

Columbianetin Acetate for Ovarian Cancer

A recent investigation exemplified the power of integrating network pharmacology with molecular docking to elucidate the mechanism of columbianetin acetate (CE) in ovarian cancer treatment [18]. The study initially identified 55 potential CE-ovarian cancer interaction targets using database mining, followed by PPI network construction which revealed eight key targets: ESR1, GSK3B, JAK2, MAPK1, MDM2, PARP1, PIK3CA, and SRC [18]. Further refinement based on expression, prognostic, and diagnostic values established ESR1, GSK3B, and JAK2 as core targets.

Molecular docking demonstrated strong binding capabilities between CE and these core targets, with favorable binding energies and stable interaction patterns [18]. Subsequent in vitro validation using SKOV3 and A2780 ovarian cancer cell lines confirmed that CE significantly inhibited proliferation and metastasis while promoting apoptosis. Mechanistic studies revealed that CE exerted these anti-cancer effects primarily through inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/GSK3B pathway, corroborating the predictions from computational analyses [18]. This case study illustrates how molecular docking can guide experimental validation to confirm multi-target mechanisms of natural products in cancer therapy.

Targeting Tubulin for Breast Cancer Therapy

In breast cancer research, molecular docking played a pivotal role in developing novel 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives as tubulin inhibitors [20]. The study integrated QSAR modeling, ADMET profiling, and molecular docking to identify compounds with optimal binding to the tubulin colchicine site. Docking results revealed that the most promising compound (Pred28) achieved an exceptional docking score of -9.6 kcal/mol and formed critical interactions with tubulin residues [20].

Molecular dynamics simulations over 100 ns further validated the stability of the tubulin-compound complex, with the Pred28 complex demonstrating the lowest RMSD (0.29 nm) and favorable RMSF values, indicating a tightly bound conformation [20]. This comprehensive computational approach enabled researchers to prioritize the most promising candidates for synthesis and experimental testing, significantly accelerating the drug discovery timeline while maximizing the likelihood of therapeutic success.

Molecular docking has firmly established itself as a cornerstone technology in targeted cancer therapy development, providing an efficient computational framework for achieving therapeutic specificity and reducing toxicity. By enabling precise prediction of ligand-target interactions at the atomic level, docking guides researchers in designing compounds that selectively engage cancer-specific targets while minimizing off-target effects [7]. The integration of docking with complementary computational approaches such as QSAR modeling, ADMET prediction, and molecular dynamics simulations creates a powerful paradigm for rational drug design that continues to transform oncology drug discovery [17] [20].

As computational capabilities advance, the future of molecular docking in cancer research points toward more sophisticated integration with artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, enhanced treatment of molecular flexibility, and more accurate scoring functions that better correlate with experimental binding affinities [17]. Furthermore, the growing application of docking in personalized oncology, where patient-specific mutations are incorporated into target structures, holds promise for developing tailored therapeutic strategies. Despite the remarkable progress, the ultimate validation of docking predictions remains grounded in rigorous experimental testing, emphasizing the continued importance of integrating computational and experimental approaches in the ongoing battle against cancer.

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) is a foundational resource for structural biology, serving as the single global archive for three-dimensional structural data of biological macromolecules [22]. Established in 1971, it has grown from just seven protein structures to housing over 244,000 experimentally-determined structures as of late 2025, including proteins, nucleic acids, and their complexes with small-molecule ligands [22] [23]. For researchers in cancer research, particularly those employing molecular docking approaches, the PDB and associated ligand databases provide indispensable resources for understanding molecular interactions at the atomic level, enabling rational drug design and discovery [8] [24].

Molecular docking has emerged as a powerful computational approach in cancer therapeutics, allowing researchers to predict how small molecules interact with target proteins [8]. This method is particularly valuable for targeting cancer stem cells (CSCs), which are implicated in therapeutic resistance and tumor recurrence [8]. The success of docking studies depends critically on access to high-quality structural data for both macromolecular targets and their ligands, making the PDB ecosystem an essential component of modern computational oncology workflows.

The Protein Data Bank: Architecture and Access

Organizational Structure and Global Partnership

The PDB is managed by the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB) partnership, an international consortium that ensures the archive remains globally accessible and consistently maintained [25] [22] [23]. Founding members include the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) in the United States, Protein Data Bank in Europe (PDBe), and Protein Data Bank Japan (PDBj) [22]. These partners jointly oversee data deposition, processing, validation, and distribution through a unified framework, with RCSB PDB serving as the designated "Archive Keeper" responsible for safeguarding the data [23].

This distributed model allows researchers to deposit structures through regional sites while maintaining a consistent, globally synchronized archive. The wwPDB partners are committed to the FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) principles, ensuring that data can be effectively used by the international research community [23]. All data in the PDB are freely available under the CC0 Public Domain Dedication, with no usage restrictions or licensing barriers [22].

Content and Growth Trends

The PDB archive has experienced exponential growth since its inception, reflecting advances in structural biology methodologies [23]. The archive's composition reflects evolving experimental methods in structural biology, with significant shifts occurring in recent years.

Table 1: PDB Holdings by Experimental Method (as of November 2025)

| Experimental Method | Structures | Percentage | Typical Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | 198,931 | 81.4% | ~2.0 Å |

| Electron Microscopy | 29,978 | 12.3% | 1.5-4.0 Å |

| NMR Spectroscopy | 14,623 | 6.0% | N/A |

| Integrative/Hybrid | 379 | 0.2% | Varies |

| Other Methods | 379 | 0.2% | Varies |

Source: Adapted from PDB content statistics [22]

Recent trends show substantial growth in structures determined by electron microscopy (3DEM), which increased approximately six-fold in just four years [23]. This method is particularly valuable for studying large macromolecular complexes that are difficult to crystallize. Meanwhile, the complexity of structures in the archive continues to increase, with growing numbers of polymer chains and ligands per structure, reflecting a shift toward more biologically relevant assemblies [23].

Data Formats and Access Tools

The PDB originally used a fixed-column-width format limited to 80 characters per line, reflecting its historical roots in punch card computing [22]. The archive has since transitioned to the more robust macromolecular Crystallographic Information File (mmCIF) format as its standard, with PDBML (an XML representation) also available [22]. These modern formats can better represent the complexity of contemporary structural biology data.

Researchers can access PDB data through multiple channels:

- Web Portals: The RCSB PDB website (rcsb.org) provides sophisticated search capabilities, visualization tools, and analytical resources [26]

- Programmatic APIs: Data can be accessed computationally via RESTful APIs for integration into analytical pipelines [26] [27]

- File Downloads: Bulk data downloads are available for large-scale analysis [22]

Visualization of PDB structures can be accomplished using numerous free and commercial software packages, including Jmol, PyMOL, UCSF Chimera, and others that provide interactive 3D molecular graphics [22].

Ligand Databases in the PDB Ecosystem

The Chemical Component Dictionary

At the heart of ligand information in the PDB is the Chemical Component Dictionary (CCD), a comprehensive repository of small molecules found in PDB structures [28] [27]. The CCD contains detailed chemical information for each unique ligand, including:

- Standardized chemical names and synonyms

- Molecular formulas and weights

- Structural representations (2D and 3D)

- Chemical descriptors (SMILES, InChI)

- Chemical taxonomy and classification

- Geometric and energetic parameters

As of 2025, the CCD contains over 48,000 unique chemical components, representing one of the most extensive collections of biologically relevant small molecules [28]. Each component is assigned a unique three-character identifier (e.g., "ATP" for adenosine triphosphate) that is used consistently across the PDB archive.

Accessing Ligand Data

The primary interface for accessing ligand information has historically been Ligand Expo, which provides search tools to find chemical components, identify structures containing specific small molecules, and download 3D structures of ligands [27]. However, RCSB PDB has announced that Ligand Expo will be retired in 2025, with users encouraged to transition to RCSB.org and wwPDB services for ligand data [27].

Current methods for accessing ligand data include:

- Chemical Search: The RCSB PDB Advanced Search interface supports searching by chemical ID, name, formula, or descriptors [27]

- Similarity Search: 2D chemical similarity searching based on SMILES, InChI, or molecular sketching [27]

- Programmatic Access: GraphQL and REST APIs for retrieving chemical component data computationally [27]

- Bulk Download: Complete sets of CCD definitions are available for download in SDF/MOL format [27]

These resources enable researchers to find ligands of interest, analyze their structural contexts, and retrieve standardized chemical information for use in docking studies and other computational approaches.

Specialized Ligand Databases

Several specialized resources have been developed to facilitate analysis of ligand-binding sites and interactions:

- PDB-Ligand: A database that provides automated classification of ligand-binding structures, enabling comparative analysis of how the same ligand binds to different proteins or homologous proteins in different environments [29]

- PDBeChem: Offers comprehensive search facilities for finding chemical components and determining which structures contain them [28]

- PDBsum: Provides graphic overviews of PDB entries with integrated information about ligand interactions [22]

These resources are particularly valuable for understanding binding site flexibility, conserved interaction patterns, and structure-activity relationships in drug discovery.

Molecular Docking in Cancer Research: Methods and Applications

Fundamentals of Molecular Docking

Molecular docking is a computational technique that predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (receptor) [8] [24]. In cancer research, this approach enables virtual screening of compounds against cancer-related targets, helping prioritize candidates for experimental testing [8]. The docking process consists of two main components:

- Search Algorithm: Explores possible orientations and conformations of the ligand in the binding site

- Scoring Function: Estimates the binding affinity of each predicted pose

Table 2: Molecular Docking Search Algorithms

| Algorithm Type | Subtypes | Key Features | Example Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic | Conformational Search, Fragmentation, Database Search | Explores conformational space systematically | FlexX, DOCK, FLOG |

| Stochastic | Monte Carlo, Genetic Algorithm, Tabu Search | Uses random sampling and optimization | AutoDock, MCDOCK, GOLD |

Source: Adapted from molecular docking methodologies [24]

Scoring functions fall into four main categories: force field-based (which calculate physical interactions), empirical (which use parameterized interactions), knowledge-based (which derive potentials from structural databases), and consensus (which combine multiple approaches) [24].

Experimental Protocol for Molecular Docking

A typical molecular docking workflow in cancer research involves several standardized steps, as demonstrated in studies targeting receptors like HER2 and EGFR in breast cancer [30]:

Step 1: Target Preparation

- Retrieve the 3D structure of the target protein from the PDB (e.g., HER2 receptor PDB code: 3PP0) [30]

- Remove unnecessary ligands, water molecules, and cofactors

- Add hydrogen atoms and compute partial charges

- Model missing loops or residues using tools like CHARMM-GUI [30]

- Define the binding site coordinates based on known ligand positions or predicted active sites

Step 2: Ligand Preparation

- Obtain or draw the 2D structure of the candidate ligand using chemical drawing software (e.g., BIOVIA Draw) [30]

- Generate 3D coordinates and optimize geometry using molecular mechanics or quantum chemical methods (e.g., Gaussian with PM3 method) [30]

- Assign proper torsion angles and flexible bonds for docking

- Generate multiple conformations for flexible ligands

Step 3: Docking Execution

- Select appropriate docking software (e.g., AutoDock, Vina, GOLD)

- Configure search parameters and scoring functions

- Run multiple docking simulations to ensure comprehensive sampling

- Cluster results and select representative poses

Step 4: Analysis and Validation

- Analyze binding modes and interaction patterns (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, salt bridges)

- Estimate binding energies and rank compounds

- Validate docking protocols by redocking known ligands and comparing with experimental structures

- Select top candidates for further experimental testing

This protocol enables researchers to efficiently screen natural compounds like camptothecin against cancer targets, identifying promising candidates for further development [30].

Applications in Cancer Stem Cell Targeting

Molecular docking plays a particularly valuable role in developing therapies targeting cancer stem cells (CSCs), which are implicated in therapeutic resistance and tumor recurrence [8]. CSCs often exhibit distinct metabolic phenotypes and signaling pathways that can be targeted using specific small molecules [8]. Docking approaches help identify compounds that interfere with CSC-specific processes by:

- Targeting surface markers unique to CSCs (e.g., CD44, CD133) [8]

- Disrupting signaling pathways that maintain stemness (e.g., Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog)

- Interfering with metabolic adaptations in CSCs

- Overcoming drug resistance mechanisms

The ability to model interactions at the atomic level provides insights that can guide the design of more effective CSC-targeted therapies, potentially addressing challenges of treatment resistance and metastasis [8].

Diagram 1: Molecular docking workflow for cancer target identification. This standardized protocol enables systematic screening of compounds against cancer-related proteins.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Docking Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function in Research | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Databases | RCSB PDB, PDBe, PDBj | Provide experimental 3D structures of targets | rcsb.org, pdbe.org, pdbj.org |

| Ligand Databases | CCD, PDBeChem, PDB-Ligand | Offer chemical information for small molecules | www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe-srv/pdbechem/ |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide, DOCK | Perform molecular docking simulations | autodock.scripps.edu, www.ccp4.ac.uk |

| Visualization Tools | PyMOL, Chimera, Jmol | Enable 3D visualization of structures and complexes | pymol.org, cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera |

| Structure Preparation | CHARMM-GUI, MolProbity | Prepare and validate structures for docking | charmm-gui.org, molprobity.biochem.duke.edu |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS | Provide parameters for energy calculations | charmm.org, ambermd.org |

Source: Compiled from multiple references [26] [24] [22]

The Protein Data Bank and its associated ligand databases provide an indispensable infrastructure for modern cancer research, particularly in the field of molecular docking and rational drug design. The continued growth and curation of these resources, coupled with advancing computational methods, offers unprecedented opportunities for developing targeted cancer therapies. As structural biology methodologies evolve, with increasing contributions from cryo-EM and integrative approaches, the PDB archive will continue to expand in both size and complexity, providing richer data for understanding cancer at the molecular level. For researchers focused on challenging targets like cancer stem cells, these resources offer pathways to overcome therapeutic resistance and develop more effective treatments. The integration of structural data with computational approaches represents a powerful strategy in the ongoing effort to combat cancer through targeted molecular interventions.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications: From Docking Algorithms to Cancer Case Studies

Molecular docking has emerged as an indispensable tool in computational oncology, providing atomic-level insights into the interactions between potential therapeutic compounds and their biomolecular targets. In the relentless fight against cancer, where drug resistance and off-target effects present significant challenges, structure-based drug design offers a pathway to more specific and effective treatments. Docking simulations enable researchers to predict how small molecules, such as drug candidates, bind to cancer-related proteins including kinases, cell cycle regulators, and apoptosis-related targets, thereby facilitating the rational design of targeted therapies [8] [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing cancer stem cells (CSCs), a subpopulation implicated in tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance [8]. The utility of docking extends beyond conventional organic compounds to include metal-based anticancer agents, such as ruthenium complexes, which have shown promise but present unique challenges for computational modeling due to the complexity of their interactions and the need for specialized force fields [31]. This technical guide examines four cornerstone docking software packages—AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide, and MOE—evaluating their practical application in cancer drug discovery through performance metrics, experimental protocols, and implementation frameworks.

Core Docking Software Characteristics

The selection of an appropriate docking program requires careful consideration of multiple factors, including sampling algorithms, scoring functions, usability, and computational efficiency. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the four featured software packages:

Table 1: Core Docking Software for Cancer Research Applications

| Software | Developer | Sampling Algorithm | Scoring Functions | Key Features in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | The Scripps Research Institute | Stochastic (Genetic Algorithm) | Vina, Vinardo, AutoDock4 | Fast execution; suitable for virtual screening of large compound libraries; handles metal coordination [31] [32] |

| GOLD | CCDC | Genetic Algorithm | GoldScore, ChemScore, ASP, ChemPLP | High accuracy in pose prediction; effective for metallodrug docking [31] [33] |

| Glide | Schrödinger | Systematic search (Monte Carlo) | GlideScore (SP, XP) | Superior performance in binding mode prediction; high enrichment in virtual screening [33] |

| MOE | Chemical Computing Group | Multiple methods | London dG, Affinity dG, Alpha HB | Integrated drug discovery platform; includes pharmacophore modeling, QSAR, and molecular dynamics [34] [35] |

Performance Metrics in Practical Applications

Benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of docking software under specific conditions. A comprehensive evaluation of five popular molecular docking programs, including GOLD, AutoDock, and Glide, assessed their ability to correctly predict the binding modes of co-crystallized inhibitors in cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, relevant targets in cancer and inflammation research [33]:

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Docking Software for Binding Pose Prediction

| Software | Success Rate (RMSD < 2 Å) | Virtual Screening Enrichment (AUC) | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glide | 100% | 0.61-0.92 (AUC) | Exceptional pose prediction accuracy; robust scoring function | Higher computational cost; commercial license required |

| GOLD | 82% | Not specified in study | Good performance with metallocomplexes; flexible handling | Commercial license required |

| AutoDock | 59% | Not specified in study | Free availability; custom parameters for metals | Lower success rate in pose prediction |

| MOE | Not benchmarked in study | Not benchmarked in study | All-in-one work environment; medicinal chemistry tools | Performance varies with chosen parameters |

The exceptional performance of Glide in reproducing experimental binding modes (100% success rate) highlights its robustness for precise binding mode analysis [33]. In virtual screening applications, which aim to identify active compounds from large chemical libraries, all tested methods demonstrated utility in enriching active COX inhibitors, with area under the curve (AUC) values ranging from 0.61 to 0.92 [33]. This capability is particularly valuable in early-stage cancer drug discovery for prioritizing candidate molecules for experimental validation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Docking Workflow

A systematic approach to molecular docking ensures reproducible and biologically relevant results. The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps common to most docking experiments in cancer research:

Receptor Preparation Protocol

The accuracy of docking simulations depends heavily on proper receptor preparation. For cancer-related targets such as kinases, growth factor receptors, or cell cycle proteins, the following steps are crucial:

- Structure Retrieval: Obtain high-resolution crystal structures of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Structures with bound inhibitors often provide the most relevant conformational states for docking [35] [33].

- Structure Refinement: Remove water molecules, cofactors, and original ligands, except for those functionally important for binding (e.g., structural metals or catalytic water molecules) [32].

- Hydrogen Addition and Protonation States: Add hydrogen atoms and assign appropriate protonation states to acidic and basic residues using tools like REDUCE or MOE's Protonate3D [32] [35]. For metal-containing systems, special attention must be paid to the coordination geometry [31].

- Energy Minimization: Perform limited energy minimization to relieve steric clashes while maintaining the overall protein structure.

Ligand Preparation Protocol

Proper ligand preparation ensures accurate representation of the chemical space and conformational sampling:

- Source Compounds: Obtain 3D structures from reliable sources such as PubChem, ZINC, or in-house compound libraries. The SDF format is preferred over PDB for small molecules as it contains essential bond information [32].

- Protonation and Tautomer Generation: Assign correct protonation states at physiological pH and generate relevant tautomers using tools like Molscrub or MOE's Ligand Preparation module [32].

- Conformational Sampling: Generate multiple low-energy conformations for flexible ligands, particularly those with rotatable bonds and ring systems.

- File Format Conversion: Convert prepared ligands to appropriate formats for docking (e.g., PDBQT for AutoDock Vina) [32].

Binding Site Definition and Grid Generation

Accurate definition of the binding site is critical for focused docking:

- Binding Site Identification: Define the binding site using experimental data from co-crystallized ligands or computational methods like MOE's Site Finder [35].

- Grid Parameter Configuration: Set up a search space box large enough to accommodate ligand flexibility but constrained to biochemically relevant regions. For example, in AutoDock Vina, box size and center coordinates can be specified in a configuration file [32]:

- Grid Map Calculation: Precalculate affinity maps for efficient energy evaluation during docking simulations. In AutoDock Vina, this can be done using the

mk_prepare_receptor.pyscript with the-goption to generate grid parameter files [32].

Docking Execution and Parameters

Execution parameters should be optimized based on the specific research question:

- Exhaustiveness Setting: For AutoDock Vina, increase exhaustiveness (e.g., to 32) for more comprehensive conformational sampling, particularly with challenging ligands like the anticancer drug imatinib [32].

- Pose Generation and Clustering: Generate multiple poses per ligand (typically 10-50) and cluster similar conformations to identify representative binding modes.

- Scoring Function Selection: Choose appropriate scoring functions based on the target-ligand system. For example, Glide offers Standard Precision (SP) and Extra Precision (XP) modes, with XP providing more rigorous scoring for virtual screening [33].

Implementation in Cancer Research

Application Workflow in Oncology Drug Discovery

The implementation of docking software in cancer research follows a structured pathway from target identification to lead optimization, as illustrated in the following diagram:

Research Reagent Solutions for Docking Experiments

Successful implementation of docking protocols requires both computational and experimental reagents. The following table outlines essential components for docking experiments in cancer research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Docking in Cancer Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Docking Experiments | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structures | Crystal structures from PDB (e.g., 1IEp for c-Abl kinase) [32] | Provides 3D atomic coordinates of cancer targets for docking | Structures with bound inhibitors often yield better results; resolution < 2.5 Å preferred |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, PubChem, NCI Diversity Set, FDA-approved drugs [36] | Source of small molecules for virtual screening against cancer targets | Pre-filter based on drug-likeness (Lipinski's Rule of 5) and cancer relevance |

| Preparation Tools | MEKO, ADFR Suite, MOE LigPrep [32] [34] | Prepares receptor and ligand structures for docking calculations | Correct protonation states critical for accurate binding predictions |

| Validation Resources | PDBbind, Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) [33] | Benchmarking datasets for validating docking protocols | Essential for establishing confidence in virtual screening results |

Case Study: Docking of Metal-Based Anticancer Complexes

The application of docking software to metal-based anticancer drugs presents unique challenges and opportunities. Ruthenium-based complexes such as [Ru(η6-p-cymene)Cl2(pta)] (rapta-C) have shown promising antimetastatic properties, but their mechanism of action involves complex interactions with multiple biological targets [31]. Docking studies have helped identify potential protein targets for these complexes, including cathepsin B (CatB), kinases, topoisomerase II (TopII), and histone deacetylase (HDAC7) [31]. Successful docking of these metal-containing ligands requires:

- Parameterization of Metal Centers: Custom force field parameters to properly handle ruthenium coordination geometry and interaction potentials [31].

- Geometry Optimization: Pre-optimization of metal complexes using quantum chemical methods such as DFT at the PBE0 level with appropriate basis sets [31].

- Target Selection: Focus on cancer-relevant targets suggested by experimental evidence, such as CatB for antimetastatic activity [31].

Comparative studies using AutoDock, GOLD, and Glide have shown strong correlations in predicted binding sites for ruthenium complexes, though significant disparities exist in complex ranking, particularly with Glide [31]. This highlights the importance of using multiple docking approaches for metallodrug development.

AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide, and MOE each offer distinct advantages for molecular docking in cancer research. Glide demonstrates superior performance in binding pose prediction, while AutoDock Vina provides a robust free alternative for virtual screening. GOLD offers balanced performance for both organic and metal-containing compounds, and MOE delivers an integrated environment for end-to-end drug discovery. The selection of appropriate software depends on specific research goals, target characteristics, and available resources. As molecular docking continues to evolve, integration with molecular dynamics simulations and machine learning approaches will further enhance its predictive power in developing targeted cancer therapies. For researchers in the field, a multimodal approach that combines the strengths of different docking packages with experimental validation offers the most promising path toward advancing oncology drug discovery.

In the field of cancer research, the discovery of new therapeutic drugs is a complex and resource-intensive endeavor. Molecular docking has emerged as a pivotal computational technique that predicts how small molecules, such as drug candidates, bind to a target protein receptor [2]. This process relies fundamentally on search algorithms to efficiently explore countless possible binding configurations and identify the most favorable ones. These algorithms are sophisticated computational methods designed to navigate the vast conformational space of a ligand within a protein's binding site, a high-dimensional landscape where the orientation, torsion, and flexibility of the molecule must be optimized [33]. The choice of search strategy directly impacts the accuracy of the predicted binding pose and the estimated binding affinity, which are critical for identifying promising anti-cancer compounds. Within the context of a broader thesis on molecular docking in cancer research, understanding these core algorithms—systematic, stochastic, and deterministic—is essential for appreciating how modern computational tools accelerate the drug discovery pipeline, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective and targeted cancer therapies [37] [2].

Classification and Core Principles of Search Algorithms

Search algorithms in molecular docking can be broadly categorized based on their underlying approach to exploring the solution space. The following table summarizes the three primary types.

Table 1: Core Types of Search Algorithms in Molecular Docking

| Algorithm Type | Fundamental Principle | Key Characteristics | Common Examples in Docking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic | Explores the search space in an exhaustive, methodical manner according to a fixed plan [33]. | Predictable, complete; performance can be hindered by the "curse of dimensionality" with highly flexible ligands. | Incremental Construction (e.g., FlexX) [33], Fragment-Based Methods |

| Stochastic | Incorporates random elements or probabilities to guide the search, mimicking natural processes [38] [39]. | Non-deterministic; can escape local optima; does not guarantee global optimum but often finds good solutions efficiently. | Genetic Algorithms (GA) [38], Simulated Annealing (SA) [38], Particle Swarm Optimization |

| Deterministic | Employs rigorous mathematical models to find the global best solution with theoretical guarantees [39]. | Guarantees optimal results (given sufficient time); can be computationally demanding for large, complex problems. | Branch-and-Bound, Cutting Plane Methods, Interval Analysis [39] |

The distinction between stochastic and deterministic optimization is particularly critical. Deterministic optimization aims to find the global best result, providing theoretical guarantees, and is well-suited for problems with exploitable features [39]. In contrast, stochastic optimization employs processes with random factors, which means it does not guarantee the global optimum but can find a good solution in a controllable amount of time, making it ideal for complex problems with large search spaces [39].

Detailed Breakdown of Algorithmic Approaches

Systematic Search Algorithms

Systematic algorithms operate on the principle of exhaustive enumeration. They decompose the ligand into fragments and systematically rebuild it within the binding site, or they exhaustively rotate all rotatable bonds in a methodical sequence [33]. A prime example is the FlexX docking program, which uses a incremental construction approach [33]. The major advantage of systematic methods is their completeness; given sufficient time, they will explore the entire conformational space. However, this becomes their primary drawback when dealing with ligands possessing many rotatable bonds, as the number of possible conformations grows exponentially, leading to prohibitive computational costs [33].

Stochastic Search Algorithms

Stochastic algorithms introduce randomness to navigate the search space more broadly and avoid becoming trapped in local energy minima. Two prominent examples are Simulated Annealing and Genetic Algorithms.

Simulated Annealing (SA) is inspired by the physical process of annealing in metallurgy [38]. It starts with a high "temperature" parameter, allowing it to accept solutions that are worse than the current solution. This probability of accepting inferior solutions decreases as the "temperature" cools over iterations, allowing the algorithm to narrow in on a low-energy (good) solution. A key feature is its hill-climbing property, which enables it to escape local optima early in the search process [38].

Genetic Algorithms (GA) are based on the principles of Darwinian evolution [38]. Instead of a single candidate solution, GA operates on a population of designs (individuals). Each individual represents a possible ligand conformation and orientation. These individuals are evaluated with a fitness function (the scoring function), and the fittest are selected to "reproduce." New individuals are created through operations like crossover (combining parts of two parents) and mutation (random perturbations) [38]. This process repeats over generations, ideally leading to a population of high-quality binding poses.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Docking Programs Utilizing Different Search Algorithms

| Docking Program | Primary Search Algorithm Type | Performance (Pose Prediction < 2Å RMSD) | Key Application in Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glide | Not Explicitly Stated | 100% [33] | Benchmarking against COX-1/COX-2 enzymes |

| GOLD | Genetic Algorithm (Stochastic) [38] | 82% [33] | Benchmarking against COX-1/COX-2 enzymes |

| AutoDock | Simulated Annealing / Genetic Algorithm (Stochastic) | 59% [33] | Benchmarking against COX-1/COX-2 enzymes |

| FlexX | Incremental Construction (Systematic) [33] | Not explicitly stated in results | Benchmarking against COX-1/COX-2 enzymes |

Deterministic Optimization Methods

Deterministic optimization algorithms are designed to find the globally optimal solution by exploiting the mathematical structure of the problem [39]. They are classified as either "complete" (able to find the global optimum with indefinite time) or "rigorous" (able to find the global optimum in finite time) [39]. These methods, such as branch-and-bound and cutting-plane algorithms, are powerful for well-defined problems like Linear Programming (LP) or Integer Programming (IP) [39]. However, in the context of molecular docking, the extremely complex, high-dimensional, and non-linear nature of the energy landscape often makes the application of purely deterministic methods computationally challenging. They are more often used in specific sub-problems or in hybrid approaches.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Pose Prediction using Stochastic Search

This protocol is based on benchmarking studies that evaluated docking programs for predicting ligand binding to cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, relevant in cancer and inflammation [33].

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D crystal structure of the target protein (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank, https://www.rcsb.org/). Remove redundant chains, water molecules, and cofactors. Add missing hydrogen atoms and assign correct protonation states. The heme molecule must be added to structures if it is missing but required for function [33].

- Ligand Preparation: Draw or obtain the 3D structure of the small molecule ligand. Assign correct bond orders and optimize its geometry using energy minimization methods, potentially with quantum chemical calculations like Density Functional Theory (DFT) for higher accuracy [40].

- Define the Search Space: Delineate the binding site on the protein, typically a box or sphere centered on the known catalytic site or the bound crystallized ligand.

- Configure Algorithm Parameters: