Molecular Alignment in 3D-QSAR: A Comparative Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of molecular alignment methodologies central to 3D-QSAR, a critical technique in modern computer-aided drug design.

Molecular Alignment in 3D-QSAR: A Comparative Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of molecular alignment methodologies central to 3D-QSAR, a critical technique in modern computer-aided drug design. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores foundational principles, from the role of molecular interaction fields (MIFs) and the probe concept to the crucial impact of alignment on model predictability. The review systematically compares manual, automated, and alignment-independent techniques, offering practical insights for method selection, troubleshooting common pitfalls, and validating models through statistical and prospective applications. By synthesizing traditional approaches with emerging trends, including AI integration, this guide serves as a strategic resource for optimizing 3D-QSAR workflows to enhance the efficiency and success of lead optimization and scaffold hopping in drug discovery projects.

The Cornerstone of 3D-QSAR: Understanding Why Molecular Alignment Matters

In modern drug discovery, understanding the interaction between a receptor and its ligand is a fundamental step in the rational design of new therapeutic agents. This process is inherently three-dimensional, as the biological receptor does not perceive a ligand as a simple set of atoms and bonds, but rather as a specific three-dimensional shape that carries a complex distribution of molecular forces [1]. This article will explore the principle of three-dimensional perception within the context of 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) studies, with a specific focus on comparing the manual and automated molecular alignment methods that are critical to this process.

The 3D Basis of Molecular Recognition

Molecular binding is a three-dimensional event. The affinity of a ligand for its receptor is determined by the interplay of intermolecular forces—such as steric bulk, electrostatic potential, and hydrogen bonding—that depend entirely on the relative spatial orientation of the two molecules [1].

The receptor perceives a ligand through these interaction forces. At long distances, the electrostatic field, which can be calculated using Coulomb's law, guides the initial approach of the ligand. At shorter ranges, steric forces, often described by a Lennard-Jones potential, become dominant, controlling the final binding step by determining which shapes can fit without clash and where bulky groups might be accommodated [1]. This is why 3D-QSAR methods move beyond simple molecular descriptors (like logP) and instead represent molecules by calculating the values of these steric and electrostatic fields at numerous points in the space surrounding them [2] [1].

Visualizing Molecular Interaction Fields

To operationalize this principle, 3D-QSAR methods use the concept of Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs). A MIF is measured by placing a conceptual "probe" atom (e.g., an sp3 carbon with a +1 charge for electrostatic fields) at various points on a 3D lattice or grid surrounding the molecule. The interaction energy between the molecule and the probe is calculated at each grid point, mapping out the regions of favorable and unfavorable interactions [1]. These fields can be visualized as iso-potential surfaces, providing researchers with an intuitive, three-dimensional map of the molecular forces that a receptor would "feel" [1].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for generating these critical molecular interaction fields.

Comparing Molecular Alignment Methodologies in 3D-QSAR

A critical step in 3D-QSAR is molecular alignment—the superimposition of all molecules in a dataset within a shared 3D reference frame that reflects their putative bioactive conformations [2]. The quality of this alignment directly impacts the model's predictive power. The two primary approaches, manual and automated alignment, were directly compared in a seminal study using 113 flexible cyclic urea inhibitors of HIV-1 protease [3].

Manual vs. Automated Alignment: An Experimental Comparison

The following table summarizes the key findings from this comparative study, which utilized Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) models.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Manual vs. Automated Alignment in 3D-QSAR (HIV-1 Protease Inhibitor Study) [3]

| Metric | Manual Alignment | Automated Alignment | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best Cross-Validated R² (q²) | Statistically higher values | 0.649 | Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation on training set |

| Best Predictive R² | 0.754 | 0.754 | Predictive power on an external test set of inhibitors |

| Model Robustness | Lower | More robust | Ability to generalize predictions to new, unseen compounds |

| Alignment Basis | Known X-ray structures | Molecular docking into the target protein (HIV-1 PR) | Docked poses agreed with X-ray structural information |

| Key Identified Interactions | Hydrogen bonds with Gly48, Gly48', Asp30 backbone | Hydrogen bonds with Gly48, Gly48', Asp30 backbone | Both methods identified the same critical receptor-ligand interactions |

Key Insight: While manual alignment can yield models with slightly higher internal statistical scores, automated alignment based on molecular docking can produce more robust models for predicting the activities of an external inhibitor set [3]. This is a significant advantage in real-world drug discovery, where the goal is to predict the activity of novel compounds.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, this section outlines the core methodologies for the alignment and modeling techniques discussed.

Protocol 1: Manual Alignment for 3D-QSAR

The traditional manual approach relies heavily on researcher intuition and known structural data [2].

- Template Selection: Choose a reference molecule, often a high-affinity ligand with a experimentally determined (e.g., X-ray) 3D structure in its bioactive conformation.

- Common Substructure Identification: Identify the largest common substructure (e.g., a scaffold or pharmacophore) shared across the data set [2].

- Superimposition: Manually align all other molecules in the dataset onto the reference template by fitting the atoms of the common substructure. This is often done using visualization software.

- Field Calculation: With all molecules in a common orientation, proceed to calculate steric and electrostatic fields on a surrounding grid.

Protocol 2: Automated Docking-Based Alignment

This structure-based method leverages computational docking to define alignment [3] [4].

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target receptor (e.g., from Protein Data Bank). Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and defining the binding site.

- Ligand Preparation: Generate low-energy 3D conformations for all ligands in the dataset and assign correct ionization states at physiological pH [5].

- Molecular Docking: Use a docking program (e.g., Glide) to predict the binding pose of each ligand within the defined binding site of the receptor. A grid box (e.g., 20 Å x 20 Å x 20 Å) is typically centered on the binding site [5].

- Pose Extraction and Alignment: Extract the highest-ranked docking pose for each ligand. These poses, all situated within the same receptor frame, automatically constitute the aligned dataset for subsequent 3D-QSAR analysis [3] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software for 3D-QSAR

Table 2: Key Research Tools and Resources for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in 3D-QSAR | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sybyl (Tripos) | Software Suite | Molecular modeling, geometry optimization, and running classic 3D-QSAR methods like CoMFA and CoMSIA [2]. | Generating steric and electrostatic field descriptors from an aligned molecule set. |

| Schrödinger Suite (Glide) | Software Suite | Protein and ligand preparation, and high-performance molecular docking for automated alignment [5]. | Predicting the binding pose of a novel ligand in a receptor with a known crystal structure (e.g., Sigma1 receptor [5]). |

| GRID | Software | A structure-based program for calculating interaction fields using a wide variety of chemical probes [1]. | Identifying "hot spots" in a protein binding site that favor interactions with specific chemical groups (e.g., carbonyl oxygen, amine). |

| RDKit | Open-Software | Cheminformatics toolkit for converting 2D structures to 3D, conformer generation, and identifying maximum common substructures (MCS) [2]. | Automating the initial generation of 3D conformers for a large dataset of compounds. |

| QSAR Toolbox | Free Software | Profiling chemicals, finding analogues, and filling data gaps via read-across and (Q)SAR models [6]. | Screening a new chemical for potential endocrine disruption by profiling it against a database of known thyroid peroxidase (TPO) inhibitors [6]. |

The fundamental principle that receptors perceive ligands in three dimensions through their shape and interaction fields is the cornerstone of 3D-QSAR. The choice of molecular alignment method is critical for building predictive models. Evidence shows that while manual alignment can provide models with high internal consistency, automated docking-based alignment produces more robust models for predicting the activity of external compounds [3]. This makes automated methods highly valuable, particularly when a well-characterized protein structure is available. The integration of these alignment strategies with powerful computational tools allows researchers to translate the abstract concept of 3D perception into concrete, predictive models that accelerate rational drug design.

In the field of three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) research, Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs) and the probe concept together form the foundational framework for comparing molecular properties and predicting biological activity. MIFs are three-dimensional interaction maps that describe the intermolecular interactions expected to form around target molecules [7]. The core principle underpinning MIF generation is the probe concept—the use of specific chemical groups to quantitatively measure the interaction potential around molecules of interest [1].

The biological activity of a ligand depends substantially on its affinity for its receptor, a process that occurs in three-dimensional space [1]. Since receptors perceive ligands not as collections of atoms but as shapes carrying complex interaction forces, MIFs provide a crucial computational approach to quantify these forces when the receptor structure is unknown [1]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of MIF methodologies, probe types, and their applications in modern drug discovery, with particular emphasis on their role in comparing molecular alignment methods within 3D-QSAR research.

Theoretical Foundations: How MIFs and Probes Work

Basic Principles of Molecular Interaction Fields

Molecular Interaction Fields represent a computational method based on the analysis and comparison of three-dimensional molecular fields (steric, electrostatic, etc.) generated in the space surrounding chemical compounds [1]. The primary objective is to establish a statistical correlation between these fields and biological activities [1]. Unlike classical 2D-QSAR, which describes molecular properties using parameters independent of spatial coordinates (e.g., logP, molar refractivity), 3D-QSAR represents properties as sets of values of (x,y,z) functions measured at numerous locations in the surrounding space [1]. This fundamental difference results in significantly more molecular descriptors being available in 3D-QSAR compared to classical approaches.

The generation of MIFs relies on the systematic calculation of interaction energies between a target molecule and a probe positioned at numerous grid points within a three-dimensional lattice surrounding the molecule [1] [7]. This lattice-based sampling enables the computationally efficient characterization of spatial interaction patterns. The resulting interaction energy values at these grid points serve as descriptors for constructing quantitative models or visual contour maps that highlight regions of favorable or unfavorable interactions [7].

The Probe Concept: Measuring Molecular Fields

The probe concept is central to MIF generation, founded on the principle that a molecular interaction field can only be measured using an appropriate "receiver" capable of interacting with it [1]. Similar to how a compass detects Earth's magnetic field, molecular interaction fields require specialized probes for their detection and quantification.

Probes are chemical entities—ranging from single atoms to functional groups or entire molecules—that are systematically positioned at grid points surrounding the target structure [1]. At each point, the interaction energy between the target and the probe is calculated using potential energy functions, creating a comprehensive map of interaction potentials [1]. The selection of appropriate probes is crucial, as they must match the field type being measured (e.g., van der Waals probes for steric fields, charged probes for electrostatic fields) [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Probe Types and Their Applications in MIF Generation

| Probe Type | Chemical Representation | Primary Field Measured | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Atom | Carbon sp³ | Steric field | Mapping molecular shape and steric hindrance [1] |

| Charged Atom | Carbon sp³ with +1 charge | Electrostatic field | Mapping electrostatic potential and charge distribution [1] |

| Functional Groups | CH₃, NH₂, CONH₂, OH | Specific functional interactions | Hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions [1] |

| Whole Molecules | H₂O, NH₃⁺, COO⁻ | Complex interaction patterns | Solvation effects, ionic interactions [1] |

| Halogenated Probes | Chlorobenzene, Bromobenzene, Iodobenzene | Halogen bonding potential | σ-hole interactions in drug design [7] |

Key Methodologies and Probe Systems

Established MIF Generation Approaches

Several computational methodologies have been developed for generating and analyzing MIFs, each with distinctive probe systems and applications:

GRID Method: Developed by Peter Goodford in 1985, GRID was the first program based on MIF calculations [1]. This structure-based approach systematically explores binding sites by calculating interaction energies between a protein and various probes at each grid point [1]. The GRID force field employs a 6-4 potential function, which provides smoother energy calculations compared to the Lennard-Jones 6-12 potential used in early CoMFA methods [8]. The methodology offers dozens of specialized probes including single atoms, water, methyl groups, amine nitrogen, carbonyl oxygen, carboxylate, hydroxyl, and various metal cations (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca⁺⁺, Fe⁺⁺, Fe⁺⁺⁺, Zn⁺⁺, Mg⁺⁺) [1].

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA): As the first validated 3D-QSAR approach, CoMFA correlates biological activity with interaction energy contributions at every grid point surrounding a set of aligned molecules [8]. The method typically employs steric (Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (Coulombic potential) probes [1]. CoMFA has become a prototype for 3D-QSAR methods and remains widely used despite the development of more advanced techniques [8].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA): An extension of CoMFA, CoMSIA calculates molecular similarity indices from similarity fields and uses them as descriptors encoding steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding properties [8]. This approach addresses some limitations of CoMFA by using a Gaussian function that avoids singularities and provides better differentiation of steric and electrostatic contributions.

Specialized Probe Developments

Recent methodological advances have focused on developing specialized probes for specific interaction types:

Halogen Bonding Probes: Conventional molecular mechanics models often fail to properly characterize halogen bonds due to their directional nature and the presence of σ-holes on halogen atoms [7]. Quantum mechanical (QM) calculations have emerged as the most reliable method for describing these interactions [7]. Recent research has employed chlorobenzene, bromobenzene, and iodobenzene as probes to map halogen-bond-formable areas around target molecules [7]. These QM-derived probes accurately reproduce the anisotropic nature of halogen interactions, which is crucial for modern structure-based drug design where halogenated compounds are increasingly common [7].

Knowledge-Based Approaches (SuperStar): The SuperStar method employs an alternative, empirical approach to generating 3D interaction maps using IsoStar—a knowledge-based library of intermolecular interactions constructed from the Cambridge Structural Database and Protein Data Bank [7]. Rather than calculating interaction energies, SuperStar predicts statistical probabilities of interactions around target molecules based on experimental data from crystal structures [7]. This approach provides complementary information to energy-based MIF calculations.

Table 2: Comparison of Major MIF Methodologies and Their Probe Systems

| Methodology | Probe Systems | Energy Functions | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRID [1] [8] | Extensive library: single atoms, functional groups, metal cations, molecular fragments | 6-4 potential function | Smooth energy calculations; diverse probe library; well-validated for active site analysis | Computational intensity for large systems |

| CoMFA [1] [8] | Standard steric and electrostatic probes (e.g., sp³ carbon, charged atoms) | Lennard-Jones (6-12) and Coulomb potentials | Established methodology; intuitive interpretation; high predictive ability | Sensitivity to molecular alignment; singularities near van der Waals surfaces |

| CoMSIA [8] | Similar to CoMFA with additional hydrophobic and H-bond probes | Gaussian-type distance-dependent functions | No singularities; better steric/electrostatic differentiation; additional field types | More parameters to optimize; potentially overfitted models |

| QM-MIF [7] | Halogenated benzene derivatives (Cl, Br, I) | Quantum mechanical (ωB97X-D, MP2) with BSSE correction | Accurate description of anisotropic interactions; reliable for halogen bonding | Extremely computationally intensive; limited to small systems without approximations |

| SuperStar [7] | Statistical distributions from database | Knowledge-based potentials from crystallographic data | Experimental basis; no force field parameterization required | Limited to well-represented interactions in databases |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard MIF Generation Protocol

The generation of Molecular Interaction Fields follows a systematic computational workflow:

Molecular Preparation: Target molecules are prepared with proper geometry optimization, protonation states, and conformation selection. For 3D-QSAR studies, molecules are typically aligned based on a common scaffold or pharmacophoric features [8].

Grid Definition: A three-dimensional lattice is superimposed around the target molecule(s), defining regularly spaced grid points where interaction energies will be calculated [1]. The grid dimensions and spacing are optimized to balance computational efficiency with adequate spatial resolution (typically 1-2 Å between grid points) [1].

Probe Selection: Appropriate probes are selected based on the chemical interactions of interest. Standard probes include steric (van der Waals), electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donors/acceptors [1].

Energy Calculation: At each grid point, the interaction energy between the target and the probe is calculated using appropriate potential functions:

Data Analysis: The resulting energy matrices are analyzed using statistical methods, primarily Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, to correlate field values with biological activities [8].

Advanced Protocol for Halogen Bond MIFs

Recent research has developed specialized protocols for mapping halogen bonding interactions using QM-based approaches [7]:

Diagram 1: Workflow for QM-Based Halogen Bond MIF Generation

Spherical Grid Setup: Define spherical grid points around the target molecule (e.g., N-methylacetamide as a protein main chain model) with radial points from 2-7 Å at 0.5 Å intervals, and polar/azimuth angles from 0°-180°/0°-360° at 10° intervals [7].

Probe Positioning: Place halogenated benzene probes (chlorobenzene, bromobenzene, iodobenzene) at each grid point with the halogen atom positioned directly on the point and the C-X bond axis aligned toward the target carbonyl oxygen [7].

QM Energy Calculation: Perform quantum mechanical calculations at the ωB97X-D/aug-cc-pVDZ-PP level for bromobenzene/iodobenzene systems or MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ for chlorobenzene systems, including counterpoise correction for basis set superposition error [7].

Energy Normalization: Normalize interaction energies to values between 0-1 based on the most stable energy encountered, setting repulsive interactions to 0 [7].

Function Approximation: Derive approximation functions Eₓ(r) for the MIFs using linear combinations of Gaussian functions to enable practical application to protein systems [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Probes

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Probes for MIF Studies

| Reagent/Probe Type | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Steric Probes | sp³ Carbon atom | Maps steric hindrance and molecular shape | CoMFA, GRID studies of congeneric series [1] |

| Electrostatic Probes | +1 Charged carbon sp³ | Maps electrostatic potential around molecules | Identifying charge-assisted binding interactions [1] |

| Hydrogen Bond Probes | Carbonyl oxygen, amine nitrogen, hydroxyl group | Characterizes H-bond donor/acceptor properties | Predicting specific protein-ligand interactions [1] |

| Halogen Bond Probes | Chlorobenzene, Bromobenzene, Iodobenzene | Maps σ-hole interactions and directional preferences | Design of halogenated drugs with improved affinity [7] |

| Solvation Probes | Water molecule | Models hydrophobic effects and solvation/desolvation | Predicting binding thermodynamics and solubility [1] |

| Hydrophobicity Probes | DRY probe (in GRID) | Characterizes hydrophobic interaction regions | ADMET profiling and membrane permeability prediction [8] |

| Metal Coordination Probes | Na⁺, K⁺, Ca⁺⁺, Zn⁺⁺ cations | Maps metal-binding regions in proteins | Metalloenzyme inhibitor design and toxicology assessment [1] |

| Knowledge-Based Probes | Statistical distributions from crystallographic databases | Empirical interaction potentials from structural data | Complementary validation of force-field based MIFs [7] |

Comparative Analysis of Probe Performance

Field Type Comparisons and Applications

Different probe types generate distinct field information that illuminates various aspects of molecular recognition:

Steric Fields: Generated using van der Waals probes (typically carbon sp³), steric fields map shape complementarity and steric hindrance effects [1]. The repulsive component dominates at short distances due to electronic cloud interpenetration, while weak attractive dispersion forces operate at longer ranges [1]. These fields are particularly important for understanding selectivity issues in drug design.

Electrostatic Fields: Calculated using Coulomb's law with charged probes, electrostatic fields capture long-range charge-charge and dipole-dipole interactions that often guide initial ligand approach to binding sites [1]. Since the electrostatic potential decays with 1/r distance dependence (compared to 1/r¹² for steric repulsion), electrostatic effects operate over much longer distances than steric effects [1].

Hydrogen Bonding Fields: Specialized probes containing hydrogen bond donors (e.g., amine nitrogen) or acceptors (e.g., carbonyl oxygen) map the directionality and strength of hydrogen bonding interactions [1]. These fields are crucial for understanding specific molecular recognition in biological systems.

Halogen Bonding Fields: Using halogenated benzene probes, these fields capture the anisotropic nature of halogen atoms, particularly the σ-hole region along the C-X bond axis where favorable interactions with electron donors occur [7]. The strength of these interactions follows the trend I > Br > Cl > F, correlating with σ-hole size and polarizability [7].

Methodological Performance in Predictive Modeling

The effectiveness of different MIF approaches varies significantly across application domains:

Traditional CoMFA vs. Modern Methods: While CoMFA remains widely used, newer approaches like L3D-PLS (CNN-based Partial Least Squares) have demonstrated superior performance in certain applications. In 30 publicly available pre-aligned molecular datasets, L3D-PLS outperformed traditional CoMFA, highlighting the potential of machine learning approaches to extract more meaningful features from molecular interaction fields [9].

Computational Efficiency Considerations: Standard molecular mechanics-based MIF calculations offer practical computation times suitable for high-throughput screening, while QM-based approaches provide higher accuracy at substantially increased computational cost [7]. The development of approximation functions for QM-level MIFs represents a promising approach to balancing accuracy and efficiency [7].

Alignment Sensitivity: A significant limitation of many MIF approaches is their sensitivity to molecular alignment, with small alignment variations potentially causing substantial changes in field patterns and resulting QSAR models [8]. Methods like GRIND (Grid-Independent Descriptors) attempt to address this by using alignment-independent descriptors derived from MIFs [8].

Molecular Interaction Fields and the probe concept continue to evolve as essential tools in computational drug discovery. The integration of MIF methodologies with other computational approaches—particularly molecular docking and machine learning—represents a powerful trend in modern drug design [8]. As the field advances, we observe several promising developments: the creation of more specialized probes for under-represented interaction types, improved QM/MM hybrid approaches for accurate yet efficient field calculations, and the incorporation of deep learning architectures to extract complex patterns from high-dimensional MIF data [7] [9].

The continued refinement of MIF methodologies and probe systems will enhance our ability to compare molecular properties, predict biological activities, and ultimately accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic agents. For researchers engaged in 3D-QSAR studies, thoughtful selection of appropriate probes and MIF generation methods remains crucial for obtaining meaningful, predictive models that effectively guide chemical optimization efforts.

The Critical Impact of Alignment on Predictive Model Accuracy and Interpretability

In the field of 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling, molecular alignment is a foundational step that critically influences the predictive accuracy and interpretability of computational models. This guide objectively compares different molecular alignment methods, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their methodological selections.

Quantitative Comparison of Alignment Method Performance

Experimental data from diverse studies demonstrate that the choice of alignment strategy directly impacts key model performance metrics, including predictive correlation (R²) and computational efficiency.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Different Molecular Alignment Strategies in 3D-QSAR

| Alignment Method | Dataset / Context | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Advantages | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-to-3D Direct Conversion (No Alignment) | 146 Androgen Receptor Binders [10] | R²Test = 0.61; Achieved in 3-7% of the time required by other methods [10]. | High speed; Avoids alignment subjectivity; Suitable for fairly inflexible substrates [10]. | May not be suitable for highly flexible molecules; Conformations not systematically reproducible [10]. |

| Bioactive Conformation (from PDB) | 461 Structures across 6 protein-ligand series [11] | Models combining 2D + 3D descriptors performed best, coding complementary molecular properties [11]. | Represents physiologically relevant binding geometry; High information content for descriptors [11]. | Dependent on availability of high-quality crystal structures; Does not account for protein flexibility. |

| Energy-Minimized Global Minimum | 146 Androgen Receptor Binders [10] | R²Test = 0.56 to 0.61 (range) [10]. | Provides consistent, reproducible geometries based on molecular thermodynamics [10]. | Computationally intensive; The global minimum may not represent the bioactive conformation [10]. |

| Template-Based Alignment | 146 Androgen Receptor Binders [10] | Performance was inferior to the 2D>3D model for the dataset studied [10]. | Can enforce a presumed biologically relevant orientation based on a known active molecule [2]. | Highly sensitive to the choice of template; Incorrect template leads to model failure [2]. |

| Consensus Predictions (Aggregate Models) | 146 Androgen Receptor Binders [10] | Consensus R²Test = 0.65 (superior to any single conformation method) [10]. | Mitigates risk of poor performance from any single, incorrect conformation strategy [10]. | Highest computational cost; Requires building and validating multiple models [10]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Alignment Methods

The quantitative data in Table 1 were generated through rigorous experimental designs. Below are detailed methodologies for key alignment approaches cited in this guide.

Protocol 1: 2D-to-3D Direct Conversion and 3D-QSDAR Modeling

This protocol outlines the alignment-independent technique used in the androgen receptor binder study [10].

- Data Curation: A diverse dataset of 146 compounds with known binding affinity (log(RBA)) for the androgen receptor was assembled. Structural diversity was ensured, encompassing steroids, pesticides, phenols, and other classes [10].

- Conformation Generation: 2D structures were directly converted to 3D coordinates using molecular mechanics as implemented in Jmol, without further energy optimization or alignment. These are referred to as "2D > 3D" structures [10].

- Descriptor Calculation (3D-QSDAR Fingerprint): A unique "fingerprint" was constructed for each molecule from the NMR chemical shifts of all carbon atom pairs (X- and Y-axes) and the inter-atomic distances between each pair (Z-axis). This fingerprint represents electronic and steric qualities [10].

- Grid Generation and Binning: The 3D-SDAR parametric space was tessellated into regular grids (binning). For a given molecule, descriptors were generated based on the number of fingerprint elements belonging to each bin [10].

- Model Building and Validation: An ensemble modeling PLS algorithm performing multiple training/hold-out test randomization cycles was used to build averaged "composite" models. Predictive performance was evaluated on external test sets, yielding the R²Test values [10].

Protocol 2: Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) with Rigorous Alignment

This protocol details the standard workflow for alignment-dependent 3D-QSAR methods, such as CoMFA [2].

- Data Collection and 3D Structure Generation: A homogenous dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC50) is assembled. 2D structures are converted to 3D and geometry-optimized using force fields (e.g., UFF) or quantum mechanical methods to achieve low-energy conformations [2].

- Molecular Alignment:

- Template Selection: A known active compound or a maximum common substructure (MCS) is chosen as a template, assuming a shared binding mode [2].

- Superposition: All molecules are systematically superimposed onto the template within a shared 3D coordinate system. This can be achieved using algorithms like RMSD fitting to the MCS [2].

- Descriptor Calculation (Field Analysis): A 3D grid is created to encompass all aligned molecules. A probe atom (e.g., sp³ carbon with +1 charge) is placed at each grid point, and steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies with each molecule are calculated [2].

- Model Building and Visualization: Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is used to correlate the field descriptors with biological activity. The model is visualized as 3D contour maps, showing regions where specific steric or electrostatic features enhance or diminish activity [2].

Protocol 3: Building a Model Using Bioactive Conformations from PDB

This protocol describes the curation of a dataset with experimentally determined bioactive conformations for a robust comparison of 2D vs. 3D descriptors [11].

- Dataset Curation: The Protein Data Bank (PDB) was mined for sets of protein-ligand complexes sharing the same protein, with uniform activity data reported. This resulted in a carefully curated dataset of 461 structures across six series [11].

- Ligand Conformation Extraction: The 3D structure of each ligand was extracted directly from its protein-ligand complex crystal structure. This conformation is defined as the "bioactive conformation" [11].

- Descriptor Calculation and Modeling: For each ligand in its bioactive conformation, multiple classes of descriptors were computed: 2D descriptors, 3D descriptors, and a combination of 2D+3D descriptors. Models were built using multiple machine learning algorithms (k-Nearest Neighbors, Random Forest, Lasso Regression) [11].

- Validation: Model performances were rigorously evaluated on external test sets, which were derived from the parent dataset either randomly or in a rational manner [11].

Workflow Visualization: 3D-QSAR Model Building and Alignment

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and pathways in a 3D-QSAR workflow, highlighting the role of molecular alignment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful 3D-QSAR studies rely on a suite of software tools and computational resources for structure handling, alignment, and model building.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions for 3D-QSAR

| Item / Software | Function in 3D-QSAR | Relevance to Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| Sybyl-X | Comprehensive molecular modeling suite. | Used for structure optimization, molecular alignment, and performing CoMFA/CoMSIA studies [12]. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used for 2D to 3D structure conversion, maximum common substructure (MCS) search, and scaffold-based alignment [2]. |

| Jmol | Open-source Java viewer for 3D chemical structures. | Can be used for basic 2D to 3D molecular structure conversion without energy minimization [10]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. | Source of bioactive conformations of ligands for alignment or model validation [11]. |

| Select KBest | Feature selection algorithm. | Used to identify the most relevant 2D or 3D descriptors from a large pool before model building, improving model robustness [13]. |

| PLS Regression | Statistical method (Partial Least Squares). | Standard technique for building the QSAR model, capable of handling the high number of correlated 3D descriptors generated [2] [10]. |

In three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling, molecular alignment constitutes the foundational step that significantly determines the success and predictive power of the resulting models. Unlike traditional 2D-QSAR methods that utilize numerical descriptors derived from molecular graphs, 3D-QSAR techniques incorporate the spatial orientation and three-dimensional characteristics of molecules, making the alignment process—the superposition of molecules in a shared 3D coordinate system—a critical determinant of model quality [2] [14]. The central challenge lies in reproducing the putative bioactive conformation and orientation that molecules adopt when interacting with their biological target, a process that requires careful consideration of molecular flexibility, conformational space, and pharmacophoric features [15].

The sensitivity of 3D-QSAR to alignment quality stems from its direct impact on molecular field calculations. Techniques such as Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) generate descriptors by measuring interaction energies or similarity indices at grid points surrounding the aligned molecules [16] [2]. Incorrect alignments introduce noise into these descriptors, compromising the model's ability to capture genuine structure-activity relationships. As noted by experts, "The majority of the signal is in the alignments, so you need to get those right. If your alignments are incorrect your model will have limited or no predictive power" [14]. This review systematically categorizes and evaluates the predominant alignment methodologies employed in contemporary 3D-QSAR research, providing a structured framework for selecting appropriate strategies based on specific research contexts.

Manual and Knowledge-Driven Alignment Methods

Core Scaffold Alignment

The most traditional alignment approach relies on identifying and superimposing common structural frameworks present across molecules in a dataset. This method is particularly effective for congeneric series where compounds share a recognizable rigid core, such as the steroid nucleus used in the seminal CoMFA study [17] [15]. The process typically involves selecting a reference molecule—often the most active compound or one with confirmed bioactive conformation—and aligning all other molecules to it by fitting atoms of the common scaffold [2] [14].

Manual alignment can be enhanced through maximum common substructure (MCS) identification, which algorithmically determines the largest shared structural fragment across molecules, even when explicit scaffolds are not immediately apparent [2]. This approach accommodates greater chemical diversity while maintaining a rational basis for superposition. Tools like RDKit's AllChem.ConstrainedEmbed() can generate 3D conformations that match scaffold atoms to a reference, ensuring consistent orientation across molecules [2]. Although this method reduces subjectivity compared to purely visual alignment, it remains dependent on the assumption that the common substructure defines the primary binding orientation.

Structure-Based Alignment Using Crystallographic Data

When experimental structural information is available, alignment based on protein-ligand complexes provides a biologically relevant reference frame. This approach utilizes crystallographic data of ligand-receptor complexes to derive template conformations for alignment [18] [15]. For example, in a 3D-QSAR study on NAMPT inhibitors, researchers used molecular docking to generate alignments based on predicted binding modes, which "produce an appropriate inhibitor conformation and alignment that yields 3D-QSAR models of comparable statistical quality as manual alignment" [18].

The principal advantage of structure-based alignment lies in its biological plausibility, as it explicitly accounts for complementarity with the target binding site. However, this method requires either experimental complex structures or reliable homology models, which may not be available for all targets. Additionally, the approach assumes consistent binding modes across the entire compound series, which may not hold for structurally diverse ligands.

Field-Based and Similarity-Driven Alignment Approaches

Field-Based Similarity Searching (FBSS)

Field-based methods represent a significant advancement in alignment techniques by utilizing molecular property fields rather than atomic positions as the basis for superposition. The FBSS algorithm positions molecules to maximize the similarity of their steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields [17] [19]. This approach recognizes that structurally diverse molecules may share similar interaction potential with biological targets despite different atomic connectivity.

The methodology involves positioning each molecule at the center of a 3D grid and calculating molecular field values at each grid point [17]. Similarity between molecules is then computed using metrics such as Carbo similarity indices or Hodgkin similarity indices [17]. Comparative studies demonstrate that "the QSAR models resulting from the FBSS alignments are broadly comparable in predictive performance with the models resulting from manual alignments" [17] [19], validating the utility of this automated approach.

Gaussian Field-Based Alignment

Modern implementations of field-based alignment often employ Gaussian functions to calculate molecular similarity, offering several advantages over traditional potential-based methods. Gaussian functions produce continuous molecular similarity maps that avoid the abrupt, non-physical cutoffs observed in some CoMFA models [16] [20]. This continuity makes the alignment process less sensitive to minor conformational variations and grid positioning [16].

In practice, Gaussian field-based alignment computes steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields using Gaussian-type functions [20]. For example, Schrödinger's Field-based QSAR tool employs "Gaussian-based electrostatic, steric, hydrogen bond donor (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and hydrophobic potential fields" for molecular alignment and subsequent QSAR model development [20]. The smooth nature of these fields enhances alignment stability, particularly for datasets with significant conformational flexibility.

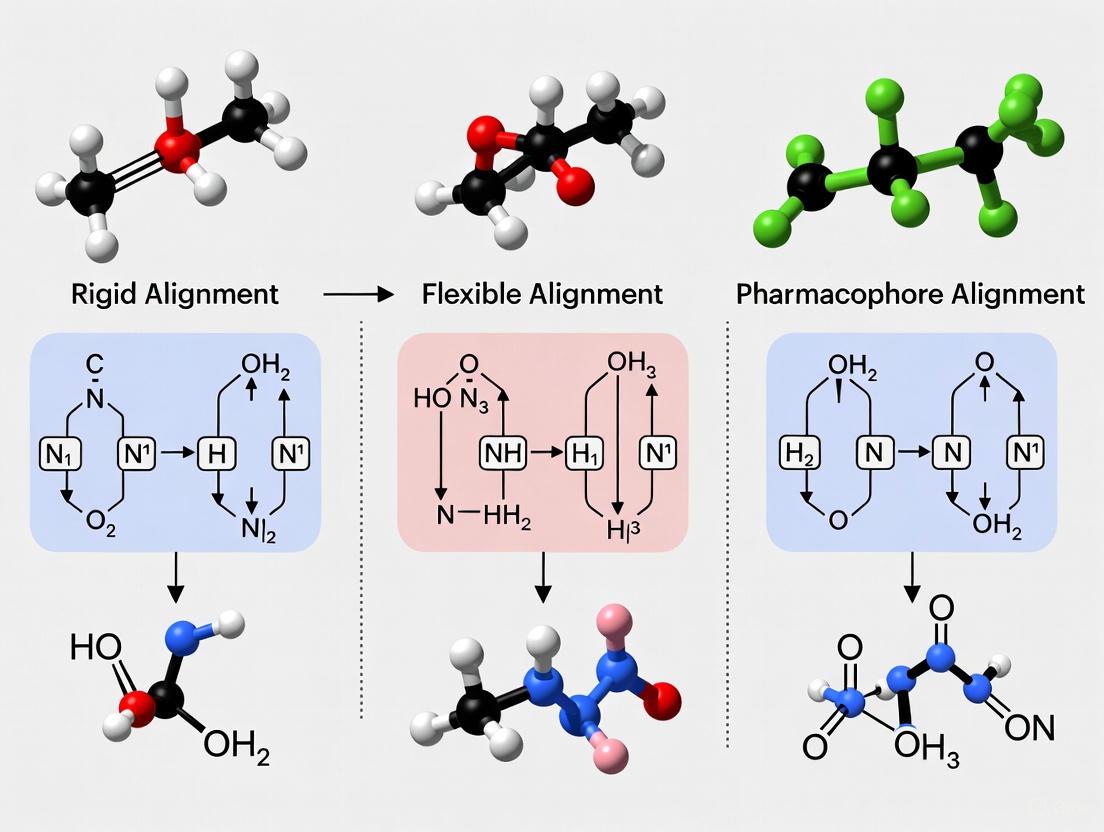

Figure 1: Workflow for Field-Based Molecular Alignment. This process generates multiple conformers, calculates molecular fields, and optimizes their similarity to produce aligned molecules for 3D-QSAR analysis.

Automated and Algorithmic Alignment Strategies

Pharmacophore-Based Automated Alignment

Pharmacophore-based automation represents a sophisticated approach that eliminates manual intervention by identifying common three-dimensional pharmacophoric features across active molecules. Tools like AutoGPA automatically generate "pharmacophore queries" – common 3D arrangements of features such as hydrogen bond acceptors, donors, hydrophobic areas, and charged groups – that induce optimal overlay of bioactive molecules [15]. The software exhaustively searches for pharmacophore queries that distinguish actives from inactives and uses these for both conformation selection and molecular alignment [15].

The AutoGPA workflow involves multiple stages: generating low-energy conformations for each molecule, assigning pharmacophore features to each conformation, identifying common 3D pharmacophore arrangements, and selecting the alignment that produces the best 3D-QSAR model statistics [15]. Validation studies demonstrate that this automated approach can achieve predictive performance comparable to manual methods, with the significant advantage of objectivity and reproducibility. In one case study, AutoGPA generated models with q² = 0.76 and r² = 0.91, outperforming traditional CoMFA while requiring no prior knowledge of bioactive conformations [15].

Alignment-Independent 3D-QSAR Methods

For specific applications, alignment-independent techniques offer an alternative that bypasses the alignment challenge entirely. 3D-Spectral Data-Activity Relationship (3D-SDAR) represents one such method that uses NMR chemical shifts and interatomic distances to create unique molecular "fingerprints" without requiring molecular superposition [10]. This technique tessellates the 3D-SDAR space into regular grids, converting fingerprint information into descriptors that capture both electronic and steric properties while remaining inherently alignment-free [10].

Surprisingly, studies comparing 3D-SDAR models built from carefully energy-minimized conformations versus simple 2D-to-3D converted structures found that the latter "produced R²Test = 0.61" and "was superior to energy-minimized and conformation-aligned models and was achieved in only 3–7% of the time required using the other conformation strategies" [10]. This suggests that for certain nuclear receptor targets, where strong activities are produced by fairly inflexible substrates, simplified approaches can yield satisfactory results with dramatically reduced computational overhead.

Comparative Analysis of Alignment Methodologies

Performance Metrics Across Alignment Strategies

The effectiveness of alignment methods can be quantitatively assessed through statistical parameters of resulting 3D-QSAR models, including cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²), conventional correlation coefficient (r²), and predictive performance on external test sets. The table below summarizes comparative performance data for different alignment strategies applied to various biological systems.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Different Alignment Methods in 3D-QSAR Studies

| Alignment Method | Biological System | q² | r² | Test Set Prediction r² | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field-Based Similarity Searching (FBSS) | Steroids (CBG) | 0.65 | 0.89 | Comparable to manual | [17] |

| Field-Based Similarity Searching (FBSS) | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors | 0.55 | 0.94 | Comparable to manual | [17] |

| Pharmacophore-Based (AutoGPA) | PDK1 inhibitors | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.65 | [15] |

| Docking-Based Alignment | NAMPT inhibitors | - | 0.84 | 0.85 | [18] |

| 2D-to-3D Conversion (3D-SDAR) | Androgen receptor binders | - | - | 0.61 | [10] |

Strategic Selection Guidelines

Choosing an appropriate alignment strategy requires careful consideration of multiple factors, including dataset characteristics, available structural information, and computational resources. The following guidelines emerge from comparative studies:

- For congeneric series with rigid cores: Manual scaffold-based alignment often suffices, particularly when supported by crystallographic data or reliable docking poses [2] [14].

- For structurally diverse datasets: Field-based or pharmacophore-based automated methods generally outperform manual approaches by identifying non-obvious yet biologically relevant superpositions [17] [15].

- When binding mode consistency is uncertain: Consensus approaches utilizing multiple alignment strategies or conformation-independent methods may provide more robust models [10] [14].

- For large-scale screening applications: Simplified 2D-to-3D conversion or alignment-free methods offer practical efficiency with acceptable predictive performance for specific target classes [10].

Notably, the pursuit of optimal alignment must be disciplined to avoid statistical overfitting. As cautioned by experienced practitioners, "you must not change the X data while paying attention (either directly or indirectly) to the Y data (the activities)" [14]. Alignment refinement based on model statistics constitutes circular reasoning and produces invalid models with artificially inflated performance metrics.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Molecular Alignment in 3D-QSAR Research

| Tool/Software | Alignment Approach | Key Features | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schrödinger Field-Based QSAR | Gaussian field-based | Five molecular field types (steric, electrostatic, HBD, HBA, hydrophobic); docking-based alignment | Commercial |

| Py-CoMSIA | User-defined | Open-source Python implementation; compatible with RDKit for conformer generation | Open-source [16] |

| AutoGPA | Pharmacophore-based | Automatic pharmacophore elucidation; conformation selection and alignment | Commercial [15] |

| FBSS | Field-based similarity | Field-based molecular similarity optimization; automated alignment | Research implementation [17] |

| Cresset Forge/Torch | Field-based and scaffold-based | Combined substructure and field similarity alignment; multiple reference molecules | Commercial [14] |

| 3D-QSDAR | Alignment-independent | Uses NMR chemical shifts and interatomic distances; no molecular superposition required | Research implementation [10] |

Molecular alignment remains both a challenge and opportunity in 3D-QSAR modeling. While manual methods continue to offer intuitive appeal for congeneric series, automated approaches based on field similarity and pharmacophore perception provide robust alternatives that reduce subjectivity and accommodate chemical diversity. Emerging open-source implementations such as Py-CoMSIA promise to increase accessibility to advanced 3D-QSAR methodologies [16], while alignment-independent techniques offer practical solutions for specific applications where traditional alignment proves problematic.

The critical consideration across all methodologies is maintaining alignment objectivity—the superposition must reflect plausible binding modes without being unduly influenced by activity data. As the field advances, integration of machine learning with physics-based alignment methods may further enhance predictive performance while reducing manual intervention. Regardless of methodological innovations, the foundational principle endures: in 3D-QSAR, alignment quality ultimately determines model success, making thoughtful selection and execution of alignment strategies essential for meaningful structure-activity insights.

A Practical Guide to 3D-QSAR Alignment Techniques and Their Real-World Applications

In the realm of three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) studies, the alignment of molecules is a critical step that predates the extraction of meaningful biological insights. Two predominant ligand-based methodologies—pharmacophore mapping and common scaffold alignment—serve as foundational approaches for superimposing molecules based on distinct principles. Pharmacophore mapping involves the spatial alignment of molecules based on their essential functional features—such as hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, and hydrophobic regions—rather than their atomic backbone. This method abstracts a molecule into a set of steric and electronic features necessary for its biological interaction [21] [22]. In contrast, common scaffold alignment relies on identifying and superimposing a shared, often rigid, structural framework or maximum common substructure (MCS) present across a set of active compounds [23]. The choice between these methodologies directly influences the predictive power and interpretability of subsequent 3D-QSAR models, guiding researchers in understanding the key structural determinants of biological activity for drug discovery.

Methodological Principles and Experimental Protocols

Core Concepts of Pharmacophore Mapping

A pharmacophore is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [21]. This approach distills molecular recognition into a three-dimensional arrangement of abstract features representing interaction types, moving beyond specific functional groups. The core features include:

- Hydrogen-bond donors (HBD) and acceptors (HBA): Represented as vectors indicating the direction of potential hydrogen bonds.

- Hydrophobic (H) and Aromatic (AR) features: Representing areas for van der Waals and dispersion interactions.

- Charged features: Positively (PO) or negatively (NE) charged centers for electrostatic interactions.

- Exclusion volumes (XVol): Representing regions where steric clashes would prevent binding, thereby mimicking the topology of the binding pocket [21] [22].

The experimental workflow for pharmacophore model generation follows two primary approaches: structure-based and ligand-based. Structure-based pharmacophore modeling utilizes experimentally determined protein-ligand complexes (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or NMR stored in the Protein Data Bank) to extract the interaction pattern directly from the binding site [21]. Software tools like Discovery Studio and LigandScout can generate pharmacophore features directly from the binding site topology, even in the absence of a bound ligand [21]. Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, conversely, addresses the absence of a known receptor structure by identifying common feature patterns from a set of active, conformationally diverse ligands. This method requires the alignment of multiple active compounds to identify their shared pharmacophoric elements [22].

Core Concepts of Common Scaffold Alignment

Common scaffold alignment, often implemented through Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) algorithms, operates on the principle that structurally similar compounds, particularly those sharing a core framework, are likely to exhibit similar biological activities. This methodology involves:

- Identification of a shared structural core: The algorithm identifies the largest common chemical substructure present across all or most molecules in the dataset.

- Conformational sampling: Generating biologically relevant, low-energy 3D conformations for each molecule, typically within a specified energy window (e.g., 2.5 kcal/mol) [23].

- Structural superposition: Aligning molecules by fitting their identified common scaffold, often using rigid-body rotations and translations to minimize the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between matched atoms [23].

The MCS alignment is particularly valuable when working with congeneric series of compounds—molecules derived from a common chemical scaffold with variations at specific substituent positions. The quality of the alignment is highly sensitive to the accuracy of the conformational analysis and the correctness of the identified common substructure.

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the comparative workflows for pharmacophore mapping and common scaffold alignment, highlighting their distinct logical pathways from input data to final 3D-QSAR model input.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Virtual Screening Performance

Virtual screening represents a critical application where the performance of alignment methods can be quantitatively evaluated. The table below summarizes key performance metrics reported for pharmacophore-based and scaffold-based approaches.

Table 1: Virtual Screening Performance Comparison

| Method | Application Context | Reported Hit Rate | Enrichment Factor | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Mapping | Various target-based screening campaigns [21] | 5-40% | Significantly higher than random screening | Identifies structurally diverse hits (scaffold hopping) |

| Common Scaffold/Similarity | Conventional similarity searching [24] | Typically <1% for random selection; varies with similarity threshold | Lower than pharmacophore methods | Effective for lead optimization in congeneric series |

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening consistently demonstrates superior hit rates compared to traditional methods. For instance, while random screening or simple similarity searching typically yields hit rates below 1% (e.g., 0.55% for glycogen synthase kinase-3β, 0.075% for PPARγ), pharmacophore-based approaches routinely achieve hit rates between 5-40% in prospective studies [21]. This significant enhancement stems from the method's ability to capture essential interaction patterns rather than structural similarity alone.

Predictive Accuracy in 3D-QSAR Modeling

The alignment method directly impacts the statistical quality and predictive power of resulting 3D-QSAR models. Recent studies comparing different alignment strategies in specific drug discovery contexts reveal distinct performance patterns.

Table 2: 3D-QSAR Model Performance with Different Alignment Rules

| Alignment Method | Target | Statistical Performance (q²/r²) | Key Advantages | Reference Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore-Based | SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors [23] | q² = 0.81, r² = 0.71 (Field 3D-QSAR) | Identifies key interaction regions; explains activity cliffs | Field 3D-QSAR model [23] |

| Common Scaffold (MCS) | SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors [23] | High predictive accuracy (model dependent) | Works well with congeneric series; intuitive alignment | MCS-based alignment in Flare [23] |

| Knowledge-Guided Diffusion (DiffPhore) | Generalized pharmacophore mapping [25] [26] | State-of-the-art pose prediction | Handles flexibility; incorporates directional constraints | DiffPhore framework [25] |

In a direct comparison study on SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) inhibitors, both alignment methods produced robust 3D-QSAR models. The pharmacophore-based Field 3D-QSAR model demonstrated strong predictive power with a q² of 0.81 and r² of 0.71, comparable to the best common scaffold-based models [23]. However, the pharmacophore approach offered the distinct advantage of visualizing regions where electrostatic and steric effects strongly influenced activity, thereby providing clearer guidance for molecular optimization.

Scaffold Hopping Potential

Scaffold hopping—the identification of novel core structures with similar biological activity—represents a critical test for the ability of alignment methods to transcend structural similarity. Pharmacophore mapping excels in this domain because it focuses on functional requirements rather than structural frameworks. By abstracting molecules to their essential features, pharmacophore models can identify structurally distinct compounds that fulfill the same interaction pattern [24]. In contrast, common scaffold alignment, by its nature, prioritizes structural conservation and is less suited for scaffold hopping unless the common substructure is defined very loosely, potentially at the cost of alignment quality. Modern AI-driven molecular representation methods that build upon pharmacophore principles have further enhanced scaffold hopping capabilities by enabling more flexible exploration of chemical space [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of pharmacophore mapping and scaffold alignment requires specialized software tools and computational resources. The table below catalogues key solutions utilized in the field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Alignment

| Tool/Solution | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [21] | Software | Structure-based & ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Virtual screening, binding site analysis |

| Discovery Studio [21] | Software | Pharmacophore model generation from binding sites | CADD, structure-based design |

| Flare [23] | Software | MCS alignment and Field 3D-QSAR | Molecular docking, 3D-QSAR studies |

| AncPhore [25] [26] | Software | Pharmacophore tool for dataset generation | Creation of 3D ligand-pharmacophore pairs |

| DiffPhore [25] [26] | AI Framework | Knowledge-guided diffusion for pharmacophore mapping | Binding pose prediction, virtual screening |

| Cresset Field 3D-QSAR [23] | Methodology | 3D-QSAR using molecular field points | Activity prediction, lead optimization |

| DUD-E [21] | Database | Curated decoys for model validation | Virtual screening benchmarking |

| ZINC20 [25] [26] | Compound Database | Commercially available compounds for screening | Virtual screening library source |

These tools represent the technological infrastructure supporting advanced molecular alignment research. For instance, DiffPhore exemplifies the cutting-edge integration of artificial intelligence with traditional pharmacophore concepts, leveraging knowledge-guided diffusion frameworks for improved 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping [25] [26]. Similarly, the Cresset Field 3D-QSAR method utilizes molecular field points derived from the Cresset XED force field as descriptors for QSAR models, enabling the capture of electrostatic and steric properties critical for biological activity [23].

The comparative analysis of pharmacophore mapping and common scaffold alignment reveals a complementary relationship rather than a competitive one between these foundational 3D-QSAR alignment methods. Common scaffold alignment demonstrates particular strength when working with congeneric series where a shared structural framework exists, enabling intuitive alignment and straightforward structure-activity relationship interpretation. Its performance excels in lead optimization contexts where incremental structural modifications are explored. Conversely, pharmacophore mapping offers superior versatility for scaffold hopping, target fishing, and cases with structurally diverse actives, as its feature-based abstraction captures essential interaction patterns independent of specific molecular frameworks. The emergence of AI-enhanced approaches like DiffPhore, which incorporates knowledge-guided diffusion models for pharmacophore mapping, further extends the capabilities of this paradigm by better handling conformational flexibility and directional constraints [25] [26]. The strategic selection between these methodologies should be guided by the structural diversity of the compound set, the specific drug discovery objective (lead identification vs. optimization), and the availability of structural information about the biological target.

In the field of computational drug design, Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) studies serve as a pivotal methodology for correlating the spatial characteristics of molecules with their biological activity. These approaches, including Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), rely on a fundamental prerequisite: the accurate spatial alignment of ligand molecules within a common coordinate system. The success and predictive power of the resulting models are profoundly influenced by the quality of these molecular overlays. For decades, researchers have faced the challenge of generating these alignments, often resorting to time-consuming manual methods that introduce subjectivity and require significant expert intervention. This comparison guide examines two automated solutions to this challenge: the Field-Based Similarity Searching (FBSS) method and the Steric and Electrostatic Alignment (SEAL) method, providing an objective analysis of their performance, underlying algorithms, and practical applications in contemporary drug discovery pipelines.

Theoretical Foundations: How FBSS and SEAL Approach the Alignment Problem

Core Principles of Field-Based Similarity Searching (FBSS)

The FBSS method operates on the principle that molecular recognition and binding are governed not by atomic positions per se, but by the molecular interaction fields surrounding the ligand. These fields represent the spatial distribution of properties critical to binding, such as steric bulk and electrostatic potential. The FBSS algorithm quantifies similarity by calculating the cosine coefficient between the field values of two molecules positioned within a three-dimensional grid, effectively measuring the congruence of their respective molecular landscapes [17]. This field-based approach offers a significant advantage: it can suggest non-obvious alignments that might be overlooked by manual methods focused on common substructures, thereby providing novel insights into structure-activity relationships.

Core Principles of Steric and Electrostatic Alignment (SEAL)

In contrast, the SEAL method employs a different strategy to achieve optimal molecular superposition. It utilizes a genetic algorithm to maximize an objective function that simultaneously optimizes the overlay of both steric and electrostatic potentials between molecules [17]. The objective function in SEAL is based on the formulation of similarity indices using Gaussian functions, which allow for the rapid evaluation of molecular similarity without the explicit use of a 3D grid. This method seeks a global solution to the alignment problem by efficiently exploring the conformational and orientational space, aiming to find the best mutual fit of the molecular fields of two or more structures.

Comparative Performance Analysis: FBSS vs. SEAL and Manual Methods

To objectively evaluate the practical utility of FBSS and SEAL, their performance must be examined against traditional manual alignments and against each other based on established benchmarks and validation datasets.

Statistical Performance in 3D-QSAR Modeling

The ultimate validation of any alignment method lies in the quality and predictive power of the 3D-QSAR models it produces. Research utilizing several literature datasets provides quantitative evidence for assessing these methods.

Table 1: Statistical Comparison of 3D-QSAR Models from Different Alignment Methods

| Alignment Method | Dataset(s) | QSAR Method | Predictive q² | Internal r² | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBSS | Steroids, 5 other literature sets | CoMFA, CoMSIA | 0.6 - 0.8 (comparable to manual) [17] | 0.91 - 0.96 (comparable to manual) [17] | Fully automated; suggests non-obvious alignments; good starting point |

| SEAL | Information from general context | Maximizes Steric/Electrostatic Overlay | Not explicitly stated in search results | Not explicitly stated in search results | Optimizes steric/electrostatic fit simultaneously; Gaussian functions for speed |

| Manual (Reference) | Classic steroids, other benchmarks | CoMFA, CoMSIA | ~0.6 - 0.8 [17] | ~0.91 - 0.96 [17] | Leverages expert knowledge; can be time-consuming and subjective |

Experimental data confirms that FBSS-generated alignments produce 3D-QSAR models with predictive performance (q²) and internal consistency (r²) that are broadly comparable to those derived from manual alignments [17]. For instance, on a series of steroids and other literature datasets, FBSS enabled CoMFA and CoMSIA models with q² values in the range of 0.6-0.8 and r² values reaching 0.91-0.96, matching the standards set by painstaking manual methods [17]. This demonstrates that automation does not necessitate a sacrifice in model quality.

Key Differentiating Factors in Methodology and Application

While both are automated, fundamental differences in their algorithms lead to varying strengths.

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of FBSS and SEAL

| Feature | FBSS (Field-Based Similarity Searching) | SEAL (Steric and Electrostatic Alignment) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Driver | Field similarity (Cosine coefficient) [17] | Similarity indices with Gaussian functions [17] |

| Algorithm Type | Field-based similarity calculation | Genetic algorithm optimizing an objective function [17] |

| Key Innovation | Application of database similarity searching to QSAR alignment | Simultaneous optimization of steric and electrostatic overlay [17] |

| Main Advantage | Can reveal non-obvious, field-based similarities | Efficiently finds a global optimum for field overlap |

| Typical Use Case | Initial automated screening and model generation | Finding an optimal alignment based on field congruence |

A critical insight from these comparisons is that FBSS serves not as a outright replacement for expert-driven manual alignment, but as a powerful complementary tool [17]. Its primary value lies in two scenarios: first, as an initial screening mechanism to rapidly determine if a dataset is amenable to 3D-QSAR analysis before investing significant manual effort; and second, as a source of novel alignment hypotheses that can inspire and guide subsequent, more detailed manual analyses [17].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for benchmarking, this section outlines the standard experimental procedures used to validate automated alignment methods like FBSS.

Standard Workflow for FBSS Validation in 3D-QSAR

The following diagram illustrates the sequential steps involved in a typical validation study for an automated alignment method.

1. Literature Dataset Curation: The process begins with the selection of well-characterized datasets from the published literature. These datasets must include experimental biological activity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Kᵢ) and ideally pre-defined training and test sets. Common benchmarks include the classic steroid dataset with binding affinity for corticosteroid-binding globulin and other sets relevant to targets like the farnesoid X receptor and opioid receptors [17] [27] [28].

2. Generate Molecular Conformations: Low-energy 3D conformations for each molecule in the dataset are generated. This often involves structure optimization using software like Sybyl-X [12].

3. Apply FBSS for Automated Alignment: The FBSS program is used to superpose all molecules in the dataset onto a chosen reference molecule. The alignment is driven by the optimization of the similarity of their molecular fields (steric and electrostatic) [17].

4. Perform 3D-QSAR (CoMFA/CoMSIA): The aligned molecule set is used as input for a 3D-QSAR analysis. The molecules are placed in a 3D grid, and their interaction fields are sampled. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is then used to derive the quantitative model linking the field values to the biological activity [17] [12].

5. Validate Model Statistically: The model is validated internally (e.g., using leave-one-out cross-validation to obtain q²) and externally by predicting the activity of the withheld test set compounds [27] [28]. A model with q² > 0.5 and a low standard error is generally considered predictive.

6. Compare with Manual Alignment: The final and crucial step is to compare the statistical performance and contour maps of the automated model with those from a model based on a manual alignment performed by domain experts [17].

Advanced Integration with Machine Learning

Recent advancements have begun to merge traditional 3D-QSAR with modern machine learning (ML) techniques. For example, after generating alignments and 3D molecular field descriptors, researchers can use algorithms like Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) to build the predictive model instead of, or in comparison with, traditional PLS [29]. One study on estrogen receptor binding found that such ML-based 3D-QSAR models outperformed traditional 2D-QSAR models in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, and selectivity [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of FBSS, SEAL, and related 3D-QSAR workflows requires a suite of specialized software tools and conceptual "reagents."

Table 3: Essential Resources for Field-Based Molecular Alignment and 3D-QSAR

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Alignment/QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| FBSS Program | Software Module | Performs the field-based similarity calculations and automated molecular superposition [17]. |

| SEAL Algorithm | Software Algorithm | Maximizes the steric and electrostatic overlay between molecules using a genetic algorithm [17]. |

| Sybyl-X/Sybyl | Molecular Modeling Suite | Provides the environment for molecule construction, conformation optimization, and running CoMFA/CoMSIA analyses [12]. |

| CoMFA/CoMSIA | 3D-QSAR Methodology | Correlates molecular interaction fields (steric, electrostatic, etc.) with biological activity after alignment [17] [12]. |

| Molecular Field Descriptors | Computational Descriptor | Quantitative 3D grids of steric/electrostatic properties that drive FBSS alignment and form the variables for QSAR [17]. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Statistical Method | The regression technique used to relate the numerous field descriptors to biological activity in classical 3D-QSAR [17]. |

The drive toward automation in molecular alignment, exemplified by methods like FBSS and SEAL, represents a significant advancement in 3D-QSAR. The experimental evidence clearly demonstrates that these automated methods are no longer just conceptual shortcuts but are robust, reliable tools capable of producing predictive models that rival those derived from expert manual alignments. Their value in increasing throughput, reducing subjectivity, and generating novel structural insights is undeniable.

The future of this field lies in the continued refinement of these methods and their integration with other cutting-edge technologies. The application of more sophisticated machine learning algorithms for analyzing molecular field data is already showing promise [29]. Furthermore, the integration of alignment and 3D-QSAR within broader drug discovery workflows—including molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and advanced cheminformatics—will further cement their role as indispensable tools for the modern computational chemist [12]. As these tools become more accessible and user-friendly, their adoption will continue to grow, accelerating the rational design of novel therapeutic agents.

Shape-based molecular alignment is a foundational technique in modern computer-aided drug design that enables the comparison of molecules based on their three-dimensional steric and electrostatic properties rather than their two-dimensional topological structure. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying structurally diverse compounds that share similar biological activities, a process known as scaffold hopping. Unlike traditional 2D methods that rely on molecular graphs and substructure matching, 3D shape-based techniques can discover non-intuitive similarities between chemically distinct compounds by examining their volumetric characteristics and functional group orientations.

The application of shape-based alignment has revolutionized virtual screening by allowing researchers to identify potential drug candidates that would be missed by conventional similarity searches. This capability is especially crucial in early drug discovery when expanding chemical space exploration or designing novel patentable chemotypes is required. Tools like ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) exemplify this methodology, using Gaussian-based shape representations and solid-body optimization to maximize volume overlap between molecules at speeds that make large-scale virtual screening practical [30]. The underlying principle posits that molecules adopting similar shapes and chemical feature distributions in 3D space are likely to interact with the same biological targets, even when their 2D structures appear quite different.

Fundamental Principles of Shape-Based Alignment

Molecular Shape Representation

Shape-based alignment tools employ different mathematical models to represent and compare molecular volumes:

Gaussian-Based Models: ROCS utilizes a Gaussian description of molecular shape that approximates hard-sphere volumes while enabling rapid similarity calculations. This approach represents molecules as collections of overlapping Gaussian functions centered on atomic positions, creating a smooth molecular surface that facilitates efficient volume overlap computation [30] [31]. The Gaussian method is parametrized to reproduce hard-sphere volumes while offering computational advantages for optimization.

Hard-Sphere Models: Alternative implementations like Schrödinger's Shape Screening represent structures as sets of hard atomic van der Waals spheres, with one sphere for each heavy atom and polar hydrogen. This approach computes overlap as the sum of pairwise atomic overlaps, ignoring intersections among three or more atoms to maximize calculation speed [32].

Chemical Feature Encoding ("Color" Force Fields)

Beyond pure shape, advanced shape-based methods incorporate chemical feature matching to improve biological relevance:

Feature-Based Scoring: ROCS extends shape matching with "color" force fields that encode chemical properties including hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups. These features are incorporated into the superposition scoring function, facilitating identification of compounds similar in both shape and key interaction capabilities [30] [33].

Pharmacophore Representation: Schrödinger's Shape Screening can alternatively represent structures as pharmacophore sites encoding hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic regions, ionizable functions, and aromatic rings, with each site represented by a 2Å hard sphere [32].

Similarity Scoring Metrics

The quantification of molecular similarity employs several specialized metrics:

Volume Overlap: The fundamental shape similarity measure compares the shared volume between two aligned structures relative to their total volume, typically expressed as

Shape Similarity = V_A∩B / V_A∪Bor normalized variants thereof [32].Composite Scoring: ROCS provides multiple scoring predicates including Tanimoto Combo (sum of shape and color Tanimoto scores), Fit Tversky, and Ref Tversky, allowing researchers to prioritize different aspects of molecular similarity for specific applications [33].