Liquid Biopsy Workflow for Cancer Monitoring: A Comprehensive Guide for Precision Oncology and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the liquid biopsy workflow for cancer monitoring, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of circulating biomarkers, including ctDNA, CTCs, and epigenetic markers. The content details advanced methodological approaches from sample collection to data analysis, addresses key challenges in sensitivity and standardization, and presents recent validation studies and comparative performance data. By synthesizing current evidence and future directions, this guide aims to support the integration of liquid biopsy into clinical trial design and precision oncology strategies, enabling non-invasive, real-time tumor dynamics monitoring.

Liquid Biopsy Workflow for Cancer Monitoring: A Comprehensive Guide for Precision Oncology and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the liquid biopsy workflow for cancer monitoring, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of circulating biomarkers, including ctDNA, CTCs, and epigenetic markers. The content details advanced methodological approaches from sample collection to data analysis, addresses key challenges in sensitivity and standardization, and presents recent validation studies and comparative performance data. By synthesizing current evidence and future directions, this guide aims to support the integration of liquid biopsy into clinical trial design and precision oncology strategies, enabling non-invasive, real-time tumor dynamics monitoring.

The Foundation of Liquid Biopsy: Core Biomarkers and Biological Principles for Cancer Monitoring

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) refers to small fragments of tumor-derived DNA found in biofluids such as blood, carrying tumor-specific genomic alterations. It represents a dynamic snapshot of tumor burden and heterogeneity, with a short half-life of approximately 16 minutes to several hours, enabling real-time monitoring of disease [1].

Table 1: Key Analytical Technologies for ctDNA Detection

| Technology | Key Feature | Reported Sensitivity | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Variant (SV) Assays | Detects tumor-specific rearrangements; avoids PCR errors [2]. | Parts-per-million (e.g., VAF < 0.01%) [2] | MRD, early recurrence detection |

| Nanomaterial-based Electrochemical Sensors | Uses graphene/MoSâ‚‚ for label-free impedance sensing; rapid results [2]. | Attomolar (within 20 mins) [2] | Point-of-care diagnostics |

| PhasED-Seq | Targets multiple SNVs on the same DNA fragment [2]. | High sensitivity for low VAF [2] | MRD detection |

| Fragmentomics & Size Selection | Enriches shorter ctDNA fragments (90-150 bp) vs. longer non-tumor cfDNA [2]. | Several-fold increase in abundance [2] | Enhances all NGS-based assays |

| Error-Corrected NGS (e.g., CAPP-Seq, TEC-Seq) | Uses UMIs and duplex sequencing to filter sequencing artifacts [1]. | ~0.01% VAF [1] | Profiling, therapy selection, MRD |

Protocol 1: ctDNA Analysis for Treatment Response Monitoring

- Sample Collection: Collect 10-20 mL of peripheral blood into cell-free DNA blood collection tubes (e.g., Streck, PAXgene). Centrifuge within 2-6 hours to separate plasma, followed by a second high-speed centrifugation to remove residual cells [2] [1].

- cfDNA Extraction: Isolate cfDNA from plasma using commercial silica-membrane or magnetic bead-based kits (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit). Quantify yield using fluorometry [1].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing:

- For tumor-informed MRD: Perform whole-genome sequencing (WGS) on tumor tissue to identify patient-specific somatic variants (SNVs, SVs). Design a custom hybrid-capture panel or multiplex PCR assay targeting these variants [2] [1].

- For tumor-agnostic profiling: Use a targeted NGS panel for common cancer driver genes (e.g., KRAS, EGFR, PIK3CA).

- Incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) during library construction to enable error correction [1].

- For increased sensitivity, perform biomechanical or enzymatic size selection to enrich for shorter DNA fragments [2].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process sequencing data with a pipeline that includes UMI consensus building, alignment, variant calling, and error suppression (e.g., using AI-based methods) to distinguish true low-frequency variants from noise [2] [1].

Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)

Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) are intact, rare cells shed from primary or metastatic tumors into the bloodstream. Their analysis provides insights into metastatic potential, allowing for functional characterization and protein expression analysis [3] [4].

Table 2: Key Analytical Technologies for CTC Isolation and Analysis

| Technology/Platform | Principle | Key Application | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| CellSearch | FDA-cleared; immunomagnetic enrichment (EpCAM+) [3]. | Prognosis in metastatic breast, prostate, CRC [3]. | Established prognostic biomarker |

| Microfluidic Labyrinth | Antigen-independent; exploits cell size/deformability [4]. | Enumeration & scRNA-seq in DCIS [4]. | Investigational; risk stratification |

| AR-V7 Testing | Detects androgen receptor splice variant in CTCs [3]. | Therapy selection in mCRPC [3]. | Predictive biomarker |

| scRNA-seq | Molecular profiling of single CTCs [4]. | Clonal evolution, EMT assessment [4]. | Research & biomarker discovery |

Protocol 2: CTC Enrichment and Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

- Sample Collection & Shipping: Draw 20-30 mL of peripheral blood into specialized preservative tubes (e.g., CellSave for enumeration, CellRescue for functional analysis). For multi-site studies, ship overnight at ambient temperature [4].

- CTC Enrichment (via Labyrinth):

- Process blood samples through the microfluidic Labyrinth device. This device uses inertial focusing and label-free sorting based on cell size and rigidity, separating CTCs from >95% of white blood cells [4].

- CTC Enumeration & Staining:

- Immunofluorescence staining: Identify CTCs as nucleated (DAPI+), epithelial (pancytokeratin, panCK+), and leukocyte-deficient (CD45-) cells [4].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing:

- Pool enriched cells and load onto a single-cell platform (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium Flex). Generate barcoded, sequence-ready libraries per the manufacturer's protocol [4].

- In parallel, process a matched formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue scroll for scRNA-seq to enable comparison between CTCs and the primary tumor [4].

- Downstream Analysis: Perform bioinformatic analyses for clustering, differential expression, pathway analysis (e.g., EMT, immunoregulatory pathways), and clonal relationship inference [4].

Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous, lipid bilayer-enclosed nanoparticles released by cells, including exosomes and microvesicles. They carry a diverse molecular cargo (proteins, lipids, DNA, various RNA species) reflective of their cell of origin, and play critical roles in cell-cell communication within the tumor microenvironment [5].

Table 3: Biomarker Cargo of Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer

| EV Cargo Type | Example Biomarkers | Potential Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins | EGFR, PD-L1, Glypican-1 [5] | Diagnosis, therapy monitoring |

| microRNA (miRNA) | miR-21, miR-141 [5] | Early detection, prognosis |

| Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA) | MALAT1, HOTAIR [5] | Disease progression, metastasis |

| Circular RNA (circRNA) | cir-ITCH, CDR1as [5] | Biomarker panels |

| DNA | gDNA, mtDNA fragments [5] | Mutational profiling |

Protocol 3: EV Isolation and Cargo Analysis from Plasma

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge blood plasma (2,000 × g for 20 min) to remove cells and debris. Collect the supernatant for EV isolation.

- EV Isolation: Use one of the following methods, noting that standardization is a key challenge in the field [5]:

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Separates EVs from soluble proteins based on size. Preserves EV integrity and function.

- Ultracentrifugation: The historical gold standard; involves high-speed centrifugation to pellet EVs.

- Precipitation Kits: Polymer-based kits that co-precipitate EVs. Can be user-friendly but may co-precipitate non-EV material.

- Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Determines EV particle size distribution and concentration.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Visualizes EV morphology.

- Western Blot: Detects presence of EV marker proteins (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81) and absence of negative markers (e.g., GM130).

- Cargo Profiling:

- RNA Analysis: Extract total RNA from EVs. For miRNA, use specific RT-qPCR panels or small RNA sequencing. For other RNAs, use RNA sequencing.

- Protein Analysis: Perform proteomic analysis via mass spectrometry or multiplex immunoassays (e.g., Luminex) to identify tumor-associated proteins [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for Liquid Biopsy Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA BCT Tubes | Stabilizes nucleated cells & cfDNA for extended storage/transport. | Preserves sample integrity in multi-center trials [4]. |

| Silica-Membrane/ Magnetic Bead Kits | Efficient isolation of high-quality cfDNA from plasma. | Input material for all downstream ctDNA assays [1]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcodes for error correction in NGS. | Essential for distinguishing true low-frequency variants [1]. |

| Hybrid-Capture or PCR Panels | Target enrichment for sequencing. | Tumor-informed MRD detection & tumor-agnostic profiling [2] [1]. |

| EpCAM-Coated Magnetic Beads | Immuno-affinity capture of epithelial CTCs. | CTC enumeration using CellSearch system [3]. |

| Microfluidic Labyrinth Chip | Label-free, size-based enrichment of CTCs. | Isolation of viable CTCs for functional studies & scRNA-seq [4]. |

| Fixation/Permeabilization Buffers | Prepare cells for intracellular & nuclear staining. | Enables AR-V7 detection in CTCs from mCRPC [3]. |

| Single-Cell Library Prep Kits | Generate barcoded NGS libraries from single cells. | Molecular profiling of CTCs & matched tumor tissue [4]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Columns | Isolate intact EVs from biofluids based on size. | Preparation of pure EV samples for downstream cargo analysis [5]. |

| EV Lysis Buffer | Break lipid bilayer to release intravesicular content. | Required for RNA/protein extraction from isolated EVs [5]. |

| Bayothrin | Bayothrin (Transfluthrin) | Bayothrin (Transfluthrin) is a chiral pyrethroid insecticide for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human or veterinary use. |

| Ondansetron-13C,d3 | Ondansetron-13C,d3, MF:C18H19N3O, MW:297.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) refers to the fraction of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in the bloodstream that originates from tumor cells. As a cornerstone of liquid biopsy, ctDNA provides a non-invasive window into tumor biology, enabling researchers and clinicians to assess tumor burden, genetic heterogeneity, and treatment response in real-time. The biological properties of ctDNA—including its origins, shedding mechanisms, and rapid clearance—underpin its value as a dynamic biomarker in cancer research and clinical development. This document details the core biology of ctDNA and provides standardized protocols for its study, supporting its integration into robust liquid biopsy workflows for cancer monitoring.

Biological Foundations of ctDNA

Cellular Origins and Mechanisms of Release

ctDNA is released into the bloodstream primarily through apoptosis and necrosis of tumor cells [1] [6]. During apoptosis, controlled enzymatic cleavage results in short DNA fragments, while necrosis releases longer, more variable fragments due to uncontrolled cell death.

- Primary Source: The majority of ctDNA originates from tumor cells undergoing programmed cell death (apoptosis) [1] [6].

- Fragment Characteristics: ctDNA fragments typically exhibit a characteristic size profile of 90–150 base pairs, which is often shorter than the cfDNA derived from healthy cell apoptosis [2] [6]. This size difference can be leveraged in laboratory assays to enrich for tumor-derived material.

- Influencing Factors: The amount of ctDNA shed is influenced by tumor vascularity and biological aggressiveness. Tumors with greater vascular invasion tend to release more ctDNA [6]. The concentration of ctDNA in plasma generally correlates with tumor burden, though this relationship can vary significantly across cancer types and individual patients [1].

Half-Life and Clearance Dynamics

A critical property of ctDNA is its remarkably short half-life in circulation, which enables near real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics.

- Clearance Rate: The half-life of ctDNA is estimated to be between 16 minutes and 2.5 hours [1] [7]. This rapid clearance allows researchers to observe molecular changes in the tumor landscape within hours of an intervention.

- Clearance Mechanisms: ctDNA is rapidly eliminated from the bloodstream by liver macrophages (Kupffer cells) and through degradation by circulating nucleases [6].

Table 1: Key Biological Characteristics of ctDNA

| Biological Feature | Description | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Origin | Apoptosis and necrosis of tumor cells [1] [6] | Reflects tumor cell turnover rate |

| Typical Fragment Size | 90–150 base pairs [2] [6] | Enables size-selection enrichment strategies |

| Half-Life in Circulation | 16 minutes to 2.5 hours [1] [7] | Allows for real-time disease monitoring |

| Clearance Mechanism | Phagocytosis by liver macrophages and degradation by circulating nucleases [6] | Physiological processes that limit detection windows |

Figure 1: ctDNA Lifecycle. This diagram illustrates the release of ctDNA into the bloodstream primarily through apoptosis and necrosis of tumor cells, followed by its rapid clearance via hepatic macrophages and circulating nucleases.

Quantitative Assessment of ctDNA in Research

Prognostic Value Across the Treatment Continuum

The presence and concentration of ctDNA at key clinical timepoints provide powerful prognostic information across multiple cancer types.

Table 2: Prognostic Value of ctDNA at Different Timepoints (Meta-Analysis Data from Esophageal Cancer) [8]

| Timepoint of ctDNA Detection | Hazard Ratio (HR) for Progression-Free Survival | Hazard Ratio (HR) for Overall Survival |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (After diagnosis, before treatment) | HR = 1.64 (95% CI: 1.30–2.07) | HR = 2.02 (95% CI: 1.36–2.99) |

| Post-Neoadjuvant Therapy (After therapy, before surgery) | HR = 3.97 (95% CI: 2.68–5.88) | HR = 3.41 (95% CI: 2.08–5.59) |

| During Follow-up (Monitoring phase) | HR = 5.42 (95% CI: 3.97–7.38) | HR = 4.93 (95% CI: 3.31–7.34) |

Key findings from this meta-analysis indicate that a positive ctDNA test is associated with a poorer prognosis throughout the patient's treatment journey, and the prognostic value of ctDNA status increases over time, from baseline through follow-up [8]. Furthermore, ctDNA-based detection can predict clinical recurrence an average of 4.53 months earlier (range: 0.98–11.6 months) than conventional radiological imaging [8].

Experimental Protocols for ctDNA Analysis

Pre-Analytical Phase: Blood Collection and Plasma Processing

The pre-analytical phase is critical for preserving ctDNA integrity, as improper handling can lead to contamination from genomic DNA released by lysed blood cells.

Protocol: Blood Collection and Plasma Separation

- Blood Draw: Collect venous blood using cfDNA BCT blood collection tubes (e.g., from Streck, Qiagen, or Roche), which contain preservatives to stabilize nucleated blood cells and prevent lysis. This allows for sample storage and transport at room temperature for up to 7 days [6]. If using conventional EDTA tubes, process the blood within 2–6 hours of collection [6].

- Plasma Separation: Perform a two-step centrifugation protocol.

- First Centrifugation: Centrifuge the blood tube at 800–1,600 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from blood cells.

- Plasma Transfer: Carefully transfer the supernatant (plasma) to a new tube, avoiding the buffy coat and cell pellet.

- Second Centrifugation: Centrifuge the plasma again at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove any remaining cellular debris.

- Storage: Aliquot the purified plasma and store at -80°C until cfDNA extraction is performed.

Analytical Phase: ctDNA Detection and Quantification

Protocol: Tumor-Informed ctDNA Detection using NGS

This protocol uses next-generation sequencing (NGS) for highly sensitive detection of ctDNA, informed by prior sequencing of tumor tissue.

- DNA Extraction: Extract total cfDNA from plasma using commercial kits (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit). Quantify the yield using fluorometry.

- Tumor Tissue Sequencing: For the tumor-informed approach, first sequence the patient's tumor tissue (e.g., from a biopsy or resection) using Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) to identify patient-specific somatic mutations (SNVs, indels) [9].

- Custom Panel Design: Design a custom NGS panel targeting ~150 personalized somatic variants identified from the tumor tissue [9].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from the plasma cfDNA using the custom panel. Incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to tag individual DNA molecules before amplification, enabling bioinformatic correction of PCR and sequencing errors [1].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process the sequencing data through a pipeline that includes:

- UMI Consensus Calling: Group reads originating from the same original DNA molecule to create a consensus sequence and eliminate random errors.

- Variant Calling: Identify somatic variants present in the plasma cfDNA.

- Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) Calculation: Determine the fraction of DNA molecules in the plasma that carry the tumor-specific mutation.

- Result Interpretation: A positive ctDNA signal is defined by the detection of tumor-specific mutations above the assay's limit of detection (LOD), which for advanced assays can be as low as 0.002% VAF [9].

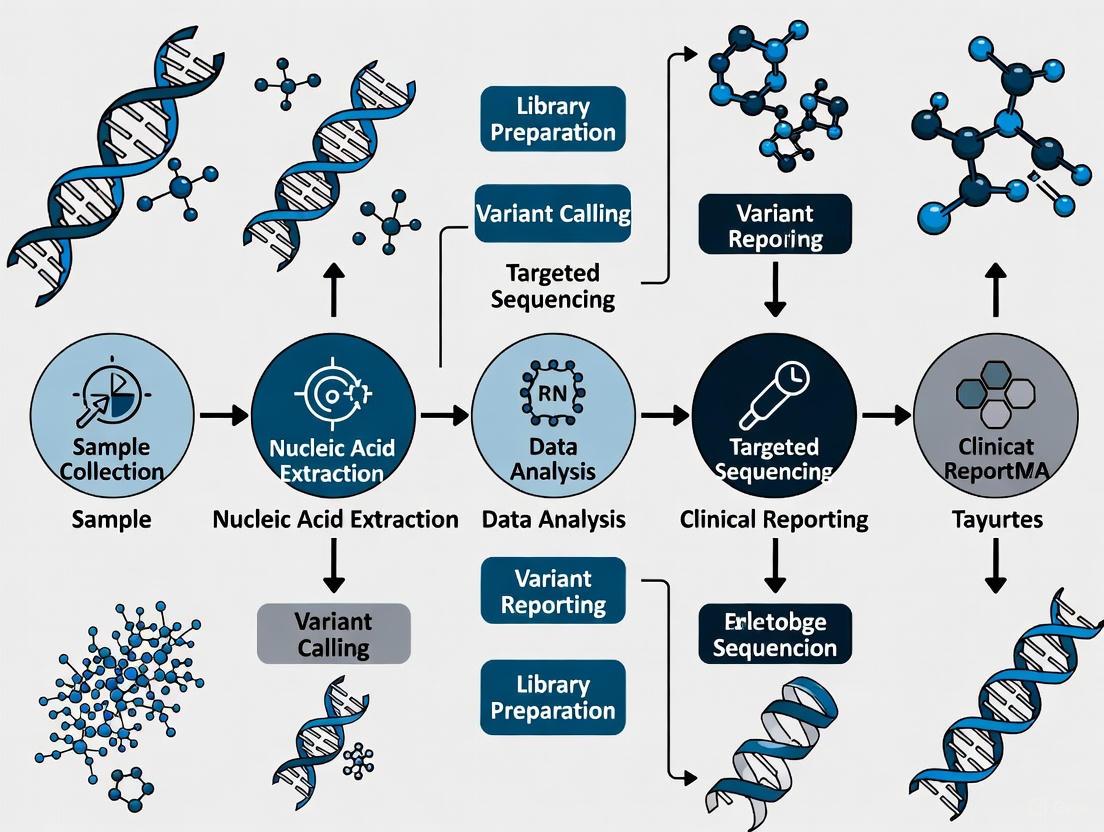

Figure 2: Tumor-Informed ctDNA Analysis Workflow. The process begins with blood draw and plasma processing, followed by cfDNA extraction. A custom sequencing panel is designed based on mutations found in tumor tissue WES. Plasma cfDNA is then sequenced using this panel, and data is analyzed with UMI-error correction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ctDNA Analysis

| Reagent / Platform | Primary Function | Key Feature in Research |

|---|---|---|

| cfDNA BCT Tubes (Streck, Qiagen, Roche) [6] | Stabilizes blood cells during storage/transport | Prevents genomic DNA contamination; enables multi-day shipping |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [1] | Molecular barcoding of DNA fragments | Enables error correction and accurate quantification of low-frequency variants |

| Custom Target Enrichment Panels (e.g., VIGIL) [9] | NGS panel for targeted sequencing | Allows highly sensitive (LOD ~0.002%) tumor-informed ctDNA tracking |

| Methylation-Specific Assays (e.g., Northstar Response) [10] | Quantifies ctDNA via cancer-associated methylation | Tumor-naive approach; tracks abundant epigenetic changes |

| Digital PCR (dPCR/ddPCR) [1] [7] | Absolute quantification of known mutations | High sensitivity for tracking specific mutations without NGS |

| Imiquimod-d9 | Imiquimod-d9, MF:C14H16N4, MW:249.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Abemaciclib metabolite M18 hydrochloride | Abemaciclib metabolite M18 hydrochloride, MF:C25H29ClF2N8O, MW:531.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The fundamental biology of ctDNA—its origin from apoptotic tumor cells, its characteristic fragment size, and its rapid clearance from the bloodstream—makes it an exceptionally powerful tool for cancer monitoring in research and drug development. The protocols and tools detailed in this document provide a framework for implementing robust ctDNA analysis, paving the way for advancements in minimal residual disease detection, therapy response monitoring, and the development of novel cancer therapeutics.

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are cancer cells that detach from primary or metastatic tumors and enter the bloodstream, serving as crucial mediators of cancer metastasis. As a key component of liquid biopsy, CTC analysis provides a minimally invasive approach for cancer diagnosis, prognosis assessment, treatment monitoring, and understanding metastasis mechanisms. This application note examines the technical challenges in CTC isolation and detection, explores established and emerging methodologies, and discusses the clinical validation and implementation of CTC enumeration across various cancer types. We present standardized protocols for CTC analysis using both commercial and research platforms, along with practical considerations for integrating CTC assessment into cancer management workflows.

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are cancer cells that shed from primary and metastatic tumor sites into the bloodstream or lymphatic system [11] [12]. First identified by Ashworth in 1869, CTCs have emerged as a critical biomarker in oncology, providing insights into tumor biology and metastasis [11] [13]. As seeds of metastasis, CTCs undergo a complex cascade involving dissemination, survival in circulation, extravasation, and colonization of distant organs [13]. The detection and analysis of CTCs offer a real-time, minimally invasive "liquid biopsy" that can complement or potentially replace traditional tissue biopsies in certain clinical scenarios [11] [14].

CTCs exhibit remarkable heterogeneity, with subpopulations undergoing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process that enhances cell motility and invasiveness [11] [13]. During EMT, CTCs often downregulate epithelial markers such as EpCAM and upregulate mesenchymal markers like vimentin and twist, complicating their detection [13] [14]. Additionally, CTCs can display stem-like properties, interact with various blood components (platelets, neutrophils), and form clusters, all of which contribute to their metastatic potential and survival in the harsh circulatory environment [11] [12].

The clinical significance of CTCs has been demonstrated across multiple cancer types. In metastatic breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers, CTC enumeration has prognostic value and can inform treatment decisions [3]. Regulatory approvals, including the FDA clearance of the CellSearch system for metastatic breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers, have established CTCs as clinically relevant biomarkers [3]. Recent expert consensus confirms the clinical utility of CTCs for prognosis and treatment monitoring in metastatic breast and prostate cancers, including AR-V7 testing in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer for therapy selection [3].

Challenges in CTC Isolation and Detection

The isolation and detection of CTCs present significant technical challenges primarily due to their extreme rarity and heterogeneity within blood samples.

Table 1: Key Challenges in CTC Detection and Potential Solutions

| Challenge | Explanation | Potential Solutions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rarity | As few as 1 CTC per billion blood cells; fewer than 1 CTC per 10 mL in early-stage cancer | Efficient enrichment methods; depletion of unwanted cells; processing large blood volumes | [11] [12] |

| Heterogeneity | Phenotypic and genotypic variations; marker expression differences (e.g., EpCAM downregulation during EMT) | Multiple biomarkers; combined size- and label-based approaches; label-free detection | [11] [13] |

| Complex Blood Environment | Non-specific binding from blood cells and plasma proteins creates high background noise | Antifouling surfaces; improved surface-cell interaction; dual-selective ligands | [11] |

| Low Viability of Captured CTCs | Shear stress during isolation causes apoptosis/necrosis; delays in processing affect downstream analysis | Gentle capture via microfluidics; low-shear designs; integrated culture systems | [11] |

| Clinical Implementation | Rapid processing needed; short storage times; logistical hurdles; high device costs | Preservative tubes; automated capture and analysis; standardized protocols | [11] [3] |

Biological and Technical Complexities

The rarity of CTCs represents a fundamental detection challenge, with concentrations as low as 1-10 CTCs per milliliter of whole blood amid approximately 10 million leukocytes and 5 billion erythrocytes [11]. This scarcity necessitates highly sensitive detection methods and efficient enrichment strategies. Furthermore, CTCs display considerable heterogeneity in size, shape, surface marker expression, and mechanical properties, complicating their isolation using standardized parameters [11] [12].

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process particularly impacts detection efficiency. As CTCs undergo EMT, they downregulate epithelial markers such as EpCAM, which forms the basis of many capture technologies [13]. This biological plasticity can lead to false negatives when relying solely on epithelial markers for detection. Physical properties of CTCs, including larger size (typically 12-25 μm compared to 8-12 μm for leukocytes) and increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, provide alternative separation parameters but also show considerable variability across cancer types and individuals [11] [12].

The blood microenvironment further complicates CTC detection through non-specific binding of blood cells and plasma proteins, creating background noise that obscures signal detection. Additionally, maintaining CTC viability post-capture remains challenging but crucial for downstream functional analyses and culture [11].

Established CTC Enumeration Methods and Clinical Validation

CTC enumeration has achieved the highest level of clinical validation in metastatic cancers, with technologies now incorporated into clinical practice for specific indications.

Table 2: Clinical Applications of CTC Enumeration Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Clinical Utility | Evidence Level | Regulatory Status | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic Breast Cancer | Prognosis, treatment monitoring | High | FDA-cleared (CellSearch) | [3] |

| Metastatic Prostate Cancer | Prognosis, treatment monitoring; AR-V7 for therapy selection | High | FDA-cleared (CellSearch) | [3] |

| Metastatic Colorectal Cancer | Prognosis | High | FDA-cleared (CellSearch) | [3] [15] |

| Early-Stage Breast Cancer | Minimal residual disease detection (promising) | Moderate | Investigational | [3] [16] |

| Other Solid Tumors | Prognosis, treatment monitoring | Variable | Investigational | [3] |

Clinically Validated Platforms and Technologies

The CellSearch system represents the first and only FDA-cleared technology for clinical CTC enumeration in metastatic breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers [3] [17]. This system uses immunomagnetic enrichment with anti-EpCAM antibodies followed by fluorescent staining for cytokeratins (CK 8, 18, 19), CD45 (leukocyte marker), and DAPI (nuclear stain) to identify and enumerate CTCs [17]. Clinical studies have consistently demonstrated that elevated CTC counts (≥5 CTCs/7.5 mL blood in breast cancer) correlate with poorer progression-free and overall survival [3].

Beyond enumeration, molecular characterization of CTCs provides additional clinical value. In metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, detection of the AR-V7 splice variant in CTCs predicts resistance to androgen receptor signaling inhibitors and helps guide therapy selection toward taxane-based chemotherapy [3]. Similarly, HER2 status assessment in CTCs from breast cancer patients can inform targeted therapy decisions, particularly when tissue biopsy is unavailable or discordant [3].

Recent international expert consensus confirms that CTCs have established clinical utility in metastatic breast and prostate cancers, while their application in other settings remains investigational [3]. The consensus emphasizes the need to shift from simple enumeration to phenotypic and molecular characterization while integrating CTC analysis with other liquid biopsy components like cell-free DNA for comprehensive cancer monitoring [3].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for CTC isolation, enumeration, and characterization using established platforms and emerging technologies.

Protocol: CTC Enumeration Using CellSearch System

Principle

The CellSearch system isolates and enumerates CTCs from whole blood through immunomagnetic enrichment targeting epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), followed by immunofluorescent staining to identify nucleated cells expressing epithelial markers but lacking leukocyte markers [17].

Materials and Reagents

- CellSearch Circulating Tumor Cell Kit (includes staining reagents, capture beads, and sample tubes)

- CellSave Preservative Tubes (10 mL)

- CellSearch AutoPrep System

- CellSearch Analyzer II

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Isopropanol (70%)

- Deionized water

Procedure

Blood Collection and Storage: Collect 10 mL peripheral blood into CellSave tubes. Invert tubes gently 8-10 times to mix preservative. Store at room temperature and process within 96 hours of collection.

Sample Preparation: Place sample tube into CellSearch AutoPrep system along with necessary reagents. The system automatically performs:

- Plasma separation by centrifugation

- Immunomagnetic enrichment with ferrofluid nanoparticles conjugated with anti-EpCAM antibodies

- Transfer of labeled cells to a cartridge chamber

- Permeabilization and staining with fluorescent antibodies:

- Phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-cytokeratin (CK 8,18,19) antibodies

- Allophycocyan-conjugated anti-CD45 antibody

- 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear stain

Image Acquisition and Analysis: The prepared cartridge is transferred to the CellSearch Analyzer, which:

- Scans the entire cartridge surface using a semi-automated fluorescence microscope

- Captures images in four fluorescence channels

- Identifies potential CTCs based on predefined criteria:

- DAPI positive (nucleated)

- Cytokeratin positive (epithelial origin)

- CD45 negative (non-hematopoietic)

- Morphologically consistent with tumor cells

Interpretation and Enumeration: A trained technician reviews the system-identified events to confirm CTC classification. CTCs are defined as nucleated cells expressing cytokeratin but lacking CD45. Results are reported as number of CTCs per 7.5 mL of blood.

Quality Control

- Process control samples with each batch to ensure proper system performance

- Monitor antibody fluorescence intensity and magnetic capture efficiency

- Maintain standardized imaging and analysis parameters

Protocol: Microfluidic CTC Capture Using Chip-Based Platforms

Principle

Microfluidic CTC isolation utilizes precisely engineered chips containing microstructures or patterns that enhance interactions between CTCs and capture surfaces, either through affinity-based methods (antibody-functionalized surfaces) or size-based separation [11].

Materials and Reagents

- Microfluidic chip (e.g., HB-Chip, graphene oxide chip, or similar)

- Syringe pump with precise flow control

- Antibodies for surface functionalization (e.g., anti-EpCAM, anti-HER2)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)

- Fixation solution (4% paraformaldehyde)

- Permeabilization buffer (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS)

- Fluorescently labeled antibodies for characterization

- Vacuum-driven tubing and connectors

Procedure

Chip Preparation and Functionalization:

- Clean chip surface with 70% ethanol followed by PBS

- Incubate with selected capture antibodies (10-50 μg/mL in PBS) for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C

- Block non-specific binding sites with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour

- Rinse with PBS to remove unbound antibodies

Blood Sample Preparation:

- Collect peripheral blood in anticoagulant tubes (EDTA or citrate)

- Dilute blood 1:1 with PBS containing 1% BSA

- Filter through 40 μm cell strainer to remove large aggregates

Microfluidic Processing:

- Load prepared chip onto microscope stage if real-time monitoring is desired

- Connect chip to syringe pump using appropriate tubing

- Prime chip with PBS at low flow rate (0.5 mL/hour)

- Introduce diluted blood sample at optimized flow rate (1-2 mL/hour)

- Wash with 10-15 mL PBS at 1 mL/hour to remove unbound cells

On-Chip Staining and Analysis:

- Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes if intracellular staining required

- Stain with fluorescent antibodies for identification (e.g., anti-cytokeratin, anti-CD45)

- Counterstain with DAPI for nucleus visualization

- Image directly on chip using fluorescence microscopy

Cell Recovery (if needed for downstream analysis):

- For live cell recovery: introduce enzyme solution (e.g., trypsin) to release captured cells

- Collect effluent in small volumes and centrifuge to concentrate cells

- Plate for culture or process for molecular analysis

Quality Control

- Validate chip efficiency using spiked tumor cell lines before patient samples

- Monitor flow rates consistently to ensure reproducible performance

- Include negative controls (healthy donor blood) to assess non-specific binding

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CTC Isolation and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-EpCAM Antibodies | Immunoaffinity capture of epithelial CTCs | CellSearch system; magnetic bead-based isolation; microfluidic chip coating | [11] [17] |

| Anti-CD45 Antibodies | Negative selection; leukocyte depletion | Negative enrichment strategies; identification of hematopoietic contamination | [17] |

| Cytokeratin Antibodies (CK 8,18,19) | CTC identification via intermediate filament proteins | Immunofluorescence staining for CTC confirmation | [17] |

| DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) | Nuclear staining for cell identification | Distinguishing nucleated cells from debris; viability assessment | [17] |

| CellSave Preservative Tubes | Blood collection and stabilization | Maintains CTC integrity for up to 96 hours post-collection | [15] |

| Immunomagnetic Beads | Magnetic separation of labeled cells | Positive (EpCAM+) or negative (CD45+) enrichment of CTC populations | [17] |

| Microfluidic Chips | Miniaturized platforms for CTC capture | HB-Chip; graphene oxide chips; size-based isolation devices | [11] |

| Membrane Filters (Polycarbonate) | Size-based separation of CTCs | Isolation by Size of Epithelial Tumor cells (ISET) | [14] |

| (Rac)-OSMI-1 | (Rac)-OSMI-1, MF:C28H25N3O6S2, MW:563.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Teicoplanin A2-5 | Teicoplanin A2-5, MF:C89H99Cl2N9O33, MW:1893.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

CTC Metastasis Pathway and Detection Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate key biological and technical aspects of CTC analysis.

CTC Metastasis Cascade

CTC Detection Workflow

CTC analysis represents a transformative approach in cancer management, bridging basic research and clinical application. While significant progress has been made in standardization and validation of CTC enumeration for prognostic applications in metastatic cancers, ongoing research focuses on expanding clinical utility through molecular characterization, integration with other liquid biopsy components, and technological innovations enhancing detection sensitivity. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide a foundation for implementing CTC analysis in cancer research and clinical practice, with the potential to significantly impact personalized cancer care through non-invasive monitoring of disease progression and treatment response.

Liquid biopsy represents a transformative, minimally invasive approach in oncology, enabling real-time detection and monitoring of cancer through the analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and other blood-borne biomarkers [18]. Among the most promising analytical targets are epigenetic markers, particularly DNA methylation and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which provide critical insights into tumor heterogeneity, evolution, and therapeutic response [18] [19]. These epigenetic alterations often emerge early in tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout disease progression, making them ideal biomarkers for early cancer detection, prognosis assessment, and monitoring minimal residual disease (MRD) [20] [19].

The integration of epigenetic markers with advanced detection technologies and artificial intelligence is paving the way for individualized, dynamically guided oncology care, moving beyond the capabilities of traditional tissue biopsies [18] [21]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for investigating these emerging epigenetic markers within the context of a comprehensive liquid biopsy workflow for cancer monitoring research.

Emerging Epigenetic Marker Profiles

DNA Methylation Biomarkers

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-position of cytosine within CpG dinucleotides, predominantly in CpG islands located in gene promoter regions [18] [20]. In cancer, aberrant methylation patterns include hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and global hypomethylation that can lead to genomic instability [18] [20]. The stability of DNA methylation patterns in circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and their early emergence in carcinogenesis make them particularly valuable for clinical applications [20] [19].

Table 1: DNA Methylation Biomarkers in Cancer Detection and Monitoring

| Cancer Type | Methylation Biomarkers | Sample Type | Clinical Application | Performance Characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | SHOX2, RASSF1A, PTGER4 | Plasma, Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid | Early detection, diagnosis | Detection of early-stage disease | [22] |

| Colorectal Cancer | SDC2, SEPT9, SFRP2 | Plasma, Stool | Early screening, monitoring | Sensitivity: 86.4%, Specificity: 90.7% | [22] |

| Breast Cancer | TRDJ3, PLXNA4, KLRD1, KLRK1 | PBMCs, Plasma | Early detection | Sensitivity: 93.2%, Specificity: 90.4% | [22] |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | SEPT9, BMPR1A, PLAC8 | Plasma | Detection and monitoring | Correlates with tumor burden | [22] |

| Pan-Cancer | Multi-gene methylation panels | Plasma | Multi-cancer early detection | High specificity (98.5%), variable sensitivity | [16] [23] |

Non-Coding RNA Biomarkers

Non-coding RNAs represent a diverse class of regulatory RNAs that include microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and other subtypes [24] [25]. These molecules are remarkably stable in biofluids due to protection within extracellular vesicles, lipoprotein complexes, or protein complexes, making them excellent biomarker candidates [24] [25]. They play crucial roles in cancer progression through regulation of gene expression at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels.

Table 2: Non-Coding RNA Biomarkers in Liquid Biopsy

| RNA Category | Representative Biomarkers | Cancer Type | Biological Function | Clinical Utility | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | miR-21, miR-34a, miR-205-5p | Multiple cancers | Oncogenic, tumor suppressive | Treatment response monitoring, prognosis | [18] [25] |

| lncRNA | HOTAIR, MALAT1, NEAT1 | Multiple cancers | Chromatin remodeling, metastasis | Disease progression, metastasis detection | [18] [25] |

| circRNA | Various tissue-specific | Multiple cancers | miRNA sponges, regulatory functions | Early detection, monitoring | [24] [25] |

| OncRNA | T3p, lung cancer-emergent oncRNAs | Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | Cancer-emergent small RNAs | Early detection (94% sensitivity) | [21] |

| piRNA | Various | Germ cell tumors, somatic cancers | Transposon silencing, gene regulation | Emerging diagnostic potential | [24] |

Experimental Protocols

DNA Methylation Analysis Workflow

Sample Collection and Processing

Protocol: Blood Collection and Plasma Separation for Methylation Analysis

- Collect peripheral blood (10-20 mL) in EDTA or Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes to prevent nucleases degradation [20] [26].

- Process within 2-6 hours of collection: centrifuge at 800-1600 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [20].

- Transfer supernatant to fresh tubes and perform a second centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove residual cells [20] [26].

- Store plasma at -80°C until cfDNA extraction. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles.

cfDNA Extraction and Bisulfite Conversion

Protocol: cfDNA Isolation and Bisulfite Treatment

- Extract cfDNA from 1-5 mL plasma using commercial kits (QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit) with carrier RNA to improve recovery [22] [26].

- Quantify cfDNA using fluorometric methods (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay); expected yield: 5-50 ng from 1 mL plasma [26].

- Convert 10-50 ng cfDNA using bisulfite treatment kits (Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation, Qiagen EpiTect Fast DNA Bisulfite) following manufacturer protocols [22] [26].

- Critical Step: Optimize conversion conditions to minimize DNA fragmentation while ensuring complete conversion (>99% efficiency) [22].

Methylation Detection and Analysis

Protocol: Targeted Methylation Sequencing

- For genome-wide analysis: Use Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) or Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) for discovery phases [20] [22].

- For clinical validation: Employ targeted approaches like bisulfite sequencing with custom panels or methylation-specific PCR [20] [19].

- Library preparation: Use kits compatible with bisulfite-converted DNA (Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq DNA Library Kit) with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to reduce PCR duplicates [22] [26].

- Sequencing: Minimum 50,000x coverage for targeted panels; appropriate spike-in controls (EpiCypher SNAP controls) for quality monitoring [26].

- Bioinformatics: Align to bisulfite-converted reference genome; use specialized tools (Bismark, MethylKit) for methylation calling; account for cfDNA fragmentation patterns [20] [22].

Non-Coding RNA Analysis Workflow

Sample Collection and RNA Stabilization

Protocol: Blood Collection for ncRNA Analysis

- Collect blood in PAXgene Blood RNA tubes or EDTA tubes with RNA stabilization additives [24] [25].

- Process within 2 hours for EDTA tubes; PAXgene tubes can be stored for up to 5 days at room temperature.

- For plasma separation: Follow similar protocol as for DNA methylation analysis with addition of RNase inhibitors to collection tubes [24] [21].

- For serum samples: Allow blood to clot for 30 minutes at room temperature before centrifugation [25].

RNA Extraction from Biofluids

Protocol: Cell-free RNA Extraction

- Extract total cell-free RNA from 0.5-4 mL plasma/serum using commercial kits (miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit, exoRNeasy Maxi Kit for exosomal RNA) [24] [21].

- Critical Consideration: Include spike-in synthetic RNAs (e.g., cel-miR-39) for normalization and quality control [24] [26].

- Elute in 14-30 µL nuclease-free water; store at -80°C.

- Quantify using capillary electrophoresis (Agilent Bioanalyzer Small RNA Kit) to assess RNA integrity; expected profile shows predominant small RNA fragments (<200 nt) [21].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Protocol: Small RNA Sequencing

- Use 1-10 ng total RNA for library preparation with specialized small RNA kits (NEBNext Small RNA Library Prep Set) [24] [21].

- Include unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to account for PCR amplification bias and enable accurate quantification [21] [26].

- Size selection (140-160 bp for miRNAs, variable for other ncRNAs) using gel electrophoresis or magnetic beads [24].

- Sequence on appropriate platforms (Illumina NextSeq, NovaSeq) with minimum 5-10 million reads per sample for adequate coverage [21].

Bioinformatics Analysis

Protocol: ncRNA Data Analysis

- Quality control: FastQC, MultiQC with adapter trimming [21].

- Alignment: Map to reference genome (GRCh38) with specialized aligners (STAR, Bowtie) accounting for small RNA species [21].

- Quantification: Count reads for known ncRNAs using miRBase, NONCODE, circBase databases [24] [21].

- Novel ncRNA discovery: Use specialized tools (CPC2, FEELnc) for identifying unannotated transcripts [21].

- Differential expression: DESeq2, edgeR with appropriate multiple testing correction [21] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Epigenetic Liquid Biopsy Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Manufacturer Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes, PAXgene Blood RNA tubes | Streck, Qiagen, BD | Preserve nucleic acid integrity during storage and transport |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit | Qiagen, Norgen Biotek | Optimized for low-abundance cfDNA/cfRNA from biofluids |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation Kit, EpiTect Fast DNA Bisulfite Kit | Zymo Research, Qiagen | Critical for DNA methylation analysis; conversion efficiency >99% |

| Library Preparation Kits | Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq, NEBNext Small RNA Library Prep | Swift Biosciences, NEB | Designed for bisulfite-converted DNA or small RNA inputs |

| Spike-in Controls | SNAP Spike-in Controls, synthetic RNA spike-ins | EpiCypher, Lexogen | Quality control and normalization standards |

| Target Enrichment Panels | Custom methylation panels, ncRNA capture panels | Agilent, IDT, Twist Bioscience | Focus sequencing power on clinically relevant targets |

| Quality Control Kits | Bioanalyzer RNA/DNA kits, Qubit assays | Agilent, Thermo Fisher | Essential for input quantification and quality assessment |

| Rock2-IN-2 | Rock2-IN-2|Selective ROCK2 Inhibitor | Bench Chemicals | |

| Usp7-IN-3 | Usp7-IN-3, MF:C29H31F3N6O3, MW:568.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications and Integrated Analysis

Multi-Omics Integration in Liquid Biopsy

The combination of DNA methylation and ncRNA biomarkers provides complementary information that enhances diagnostic sensitivity and specificity [18] [26]. DNA methylation offers information about the tissue of origin and tumor suppressor silencing, while ncRNAs reflect real-time regulatory activity and cellular communication [18] [24].

Protocol: Integrated Multi-Omic Analysis

- Process parallel aliquots of the same blood sample for DNA methylation and ncRNA analysis [26].

- Utilize multi-task generative AI models (e.g., Orion) to integrate methylation and ncRNA data while accounting for technical confounders [21].

- Implement cross-validation strategies to assess model performance and generalizability to independent datasets [21].

Clinical Validation and Implementation

For successful translation of epigenetic biomarkers into clinical practice, rigorous validation is essential [20] [23].

Protocol: Analytical Validation

- Determine limit of detection (LOD) using dilution series of methylated DNA or synthetic ncRNA spikes in normal plasma [20] [26].

- Assess precision through repeatability (within-run) and reproducibility (between-run, between-operator, between-laboratory) experiments [20].

- Establish reference ranges using appropriate control populations matched for age, sex, and comorbidities [20].

- For in vitro diagnostic applications, follow FDA, CE-IVD, or other relevant regulatory guidelines [23].

Epigenetic markers in cfDNA, particularly DNA methylation and non-coding RNAs, represent powerful tools for cancer detection and monitoring through liquid biopsy. The protocols outlined herein provide a framework for implementing these analyses in research settings, with potential for translation into clinical practice. As detection technologies continue to advance and computational methods become more sophisticated, these epigenetic biomarkers are poised to play an increasingly important role in personalized oncology, enabling earlier detection, better monitoring, and more tailored therapeutic interventions.

Comparative Analysis of Biomarker Properties and Clinical Applications

Biomarkers are defined as measurable characteristics that serve as indicators of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an exposure or intervention [27]. According to the joint FDA-NIH Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools (BEST) resource, biomarkers are categorized into seven primary classes based on their clinical application: diagnostic, monitoring, pharmacodynamic/response, predictive, prognostic, safety, and susceptibility/risk biomarkers [27] [28]. This classification system provides a critical framework for understanding how different biomarkers contribute to disease management and therapeutic development.

The discovery and validation of biomarkers, particularly from high-dimensional genomic data, typically employs feature selection techniques to identify the most discriminating features for a given classification task [29]. Effective biomarkers share essential characteristics including high sensitivity and specificity, reproducibility across different laboratories and over time, ease of measurement, affordability, consistency across diverse populations, correlation with disease severity, and the ability to provide adequate lead time for early intervention [30]. Furthermore, reliable biomarkers should demonstrate a dynamic response to treatment and possess a clear mechanistic link to the disease process [30].

Table 1: BEST Resource Biomarker Classification Framework

| Biomarker Category | Primary Function | Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | Detect or confirm presence of a disease or condition [27] | Identify individuals with a disease subtype; redefine disease classification [27] |

| Monitoring | Assess status of disease or medical condition serially [27] | Track chronic diseases (e.g., HbA1c in diabetes); measure exposure to medical products [27] |

| Pharmacodynamic/Response | Indicate biological response to therapeutic intervention [28] | Assess pharmacological effects; guide dose selection in early clinical development [28] |

| Predictive | Identify likelihood of response to specific treatment [27] | Select patients for targeted therapies; avoid ineffective treatments and associated toxicity [27] |

| Prognostic | Identify likelihood of clinical event or disease progression [28] | Inform long-term disease management strategies; assess natural history of disease [28] |

| Safety | Indicate likelihood of adverse event or toxicity [27] [28] | Monitor drug safety; detect organ damage or physiological stress [27] |

| Susceptibility/Risk | Identify potential for developing disease or condition [27] | Stratify populations for screening; implement preventive measures for high-risk individuals [27] |

Biomarker Applications in Liquid Biopsy for Cancer Monitoring

Liquid biopsy represents a transformative approach in oncology that analyzes tumor-derived components from bodily fluids, primarily blood, offering a minimally invasive alternative to traditional tissue biopsies [31] [32]. This technology enables serial sampling to monitor tumor evolution, therapeutic response, and emerging resistance mechanisms over time [31]. The continuous perfusion of blood through tumors allows for the collection of various cancer components, including circulating tumor cells (CTCs), circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), tumor-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs), tumor-educated platelets (TEPs), and circulating cell-free RNA (cfRNA) [31]. These analytes provide complementary information about tumor heterogeneity, mutation profiles, and clonal evolution that is crucial for personalized cancer management.

Liquid biopsy offers significant advantages over tissue biopsy, including minimal invasiveness, rapid turnaround time, accessibility for serial sampling, and the ability to capture tumor heterogeneity more comprehensively [31] [32]. The clinical applications of liquid biopsy in cancer management encompass early detection and screening, prognosis assessment, monitoring treatment response, identifying minimal residual disease (MRD), detecting early relapse, and guiding treatment decisions by identifying actionable mutations [31]. Current research efforts focus on optimizing pre-analytical and analytical processes to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of liquid biopsy platforms, with numerous clinical trials underway to validate its utility in various cancer types [31].

Table 2: Analytical Components in Liquid Biopsy and Their Clinical Applications

| Liquid Biopsy Component | Description | Primary Cancer Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) | Tumor-derived fragmented DNA in circulation [31] [32] | Detection of actionable mutations; monitoring treatment response; identifying resistance mechanisms [31] [32] |

| Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) | Intact tumor cells shed into bloodstream [31] [32] | Prognostic stratification; monitoring metastatic potential; understanding tumor heterogeneity [31] [32] |

| Tumor Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) | Membrane-bound vesicles containing proteins, nucleic acids [31] | Analyzing proteomic and genomic signatures; monitoring tumor progression and response [31] |

| Circulating Cell-Free RNA (cfRNA) | RNA molecules including miRNAs, lncRNAs [31] | Early detection; monitoring tumor progression; understanding regulatory mechanisms [31] |

| Tumor-Educated Platelets (TEPs) | Platelets containing tumor-derived biomolecules [31] | Detecting cancer biomarkers; monitoring progression and metastasis [31] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Analysis in Liquid Biopsy

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Isolation and Analysis

The isolation and analysis of ctDNA requires meticulous pre-analytical procedures to ensure sample integrity and analytical sensitivity. Blood samples should be collected in specialized tubes containing stabilizers to prevent white blood cell lysis and contamination of ctDNA with genomic DNA from hematopoietic cells. Within 4-6 hours of collection, plasma must be separated through a two-step centrifugation protocol: initial centrifugation at 1,600-2,000 × g for 10-20 minutes at 4°C to obtain plasma, followed by a second centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove remaining cellular debris [31]. The resulting plasma can be stored at -80°C until DNA extraction.

ctDNA extraction should be performed using commercially available kits optimized for cell-free DNA, with quality control measures including fluorometric quantification and fragment size analysis to confirm the characteristic 166 bp nucleosomal pattern. For mutation detection, digital PCR (dPCR) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels provide the required sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants in a background of wild-type DNA [31]. For dPCR, the protocol involves designing specific probes for target mutations, partitioning the sample into thousands of individual reactions, amplification, and fluorescence reading to absolutely quantify mutant allele frequency. For NGS-based approaches, unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) should be incorporated during library preparation to correct for amplification biases and sequencing errors, enabling accurate quantification of variant allele frequencies down to 0.1% in some applications [31].

Circulating Tumor Cell (CTC) Enrichment and Characterization

CTC analysis begins with blood collection in preservative tubes to maintain cell viability, with processing recommended within 24-48 hours. CTC enrichment typically employs either label-dependent approaches using antibodies against epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) or other epithelial markers, or label-free methods leveraging physical properties such as size, density, or electrical characteristics [31]. Immunomagnetic separation provides high purity but may miss epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitioned (EMT) CTCs that have downregulated epithelial markers, while size-based filtration methods preserve all CTC subtypes but may have lower purity.

Following enrichment, CTC characterization typically involves immunocytochemical staining for positive markers (e.g., cytokeratins) and negative markers (e.g., CD45) to confirm epithelial origin and exclude hematopoietic cells. Molecular analysis of CTCs may include whole transcriptome analysis, targeted RNA sequencing, or single-cell DNA sequencing to explore heterogeneity and identify therapeutic targets [31]. For functional characterization, ex vivo culture of CTCs or patient-derived xenograft models can provide insights into drug sensitivity and resistance mechanisms, though these approaches are technically challenging and low-throughput.

Extracellular Vesicle (EV) Isolation and Cargo Analysis

EV isolation requires careful consideration of the trade-offs between yield, purity, and functionality. Differential ultracentrifugation remains the most widely used method, involving sequential centrifugation steps to remove cells and debris (300 × g for 10 minutes, 2,000 × g for 20 minutes, 10,000 × g for 30 minutes) followed by high-speed centrifugation (100,000 × g for 70-120 minutes) to pellet EVs [31]. Alternative approaches include density gradient centrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography, polymer-based precipitation, and immunoaffinity capture using antibodies against EV surface markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81).

For cargo analysis, EV membranes must be lysed using detergent-based buffers or repeated freeze-thaw cycles to release internal contents. RNA extraction should be performed using phenol-chloroform methods or commercial kits specifically validated for small RNA species, with quality assessment using bioanalyzer systems to confirm the presence of small RNAs including miRNAs. Protein analysis typically involves mass spectrometry-based proteomics or immunoassays for specific protein biomarkers. Emerging techniques for direct EV analysis without lysis include nanoparticle tracking analysis for size and concentration determination, and single-EV analysis methods using advanced flow cytometry or imaging techniques [31].

Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Liquid Biopsy Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Cell-free DNA BCT tubes, EDTA tubes with preservatives | Stabilize blood samples; prevent contamination from hematopoietic cell genomic DNA [31] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, Maxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma Kit | Isolate high-quality ctDNA/cfRNA; maintain fragment integrity for downstream analysis [31] |

| Library Preparation Kits | AVENIO ctDNA Library Preparation Kits, QIAseq Targeted DNA Panels | Prepare sequencing libraries with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) for NGS applications [31] |

| PCR Reagents | ddPCR Supermix for Probes, TaqMan Genotyping Master Mix | Enable sensitive mutation detection and absolute quantification in digital PCR applications [31] |

| CTC Enrichment Kits | CellSearch CTC Kits, MACS MicroBead Kit | Islect and enumerate circulating tumor cells from peripheral blood [31] |

| EV Isolation Reagents | ExoQuick-TC, Total Exosome Isolation Reagent | Precipitate or capture extracellular vesicles from plasma and other biofluids [31] |

| Immunoassay Reagents | ELISA kits, Luminex multiplex panels | Quantify protein biomarkers in serum/plasma; enable high-throughput screening [31] |

Workflow Visualization

Liquid Biopsy Workflow Overview

Biomarker Relationships and Technologies

Advanced Methodologies and Clinical Applications in Liquid Biopsy Workflows

Liquid biopsy has emerged as a transformative tool in cancer research and management, offering a minimally invasive means to repeatedly sample tumor-derived genetic material. The analytical phase of liquid biopsy, particularly the analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA), has advanced significantly with the advent of highly sensitive molecular techniques. However, the pre-analytical phase—encompassing blood collection, processing, and cfDNA extraction—remains a critical source of variability that can profoundly impact downstream analytical results and their clinical interpretation. In fact, studies indicate that pre-analytical errors contribute to 60-70% of total laboratory errors [33]. This application note provides a detailed protocol and critical considerations for standardizing the pre-analytical workflow for cfDNA-based cancer monitoring research, ensuring reliable and reproducible results.

Blood Collection and Initial Processing

Blood Collection Tube Selection

The choice of blood collection tube is the first critical decision point in the liquid biopsy workflow, as it determines sample stability, allowable processing timeframes, and potential sources of contamination. The table below compares the performance characteristics of commonly used tubes based on recent studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Blood Collection Tubes for Liquid Biopsy

| Tube Type | Additive/Mechanism | Recommended Time to Plasma Processing | Relative cfDNA Yield (0h) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K2EDTA/K3EDTA | Chelating agent | <1-2 hours [34] [35] | 2.41 ng/mL [34] | Standard tube, multi-purpose, no special handling required | Short stability window, risk of genomic DNA contamination from leukocyte lysis |

| Streck | Chemical crosslinking [36] [34] | Up to 7 days at RT [34] | 2.74 ng/mL [34] | Excellent stability at room temperature, prevents leukocyte lysis | Lower plasma volume recovery (mean=3.48mL) [34], specific centrifugation conditions |

| PAXgene | Biological apoptosis prevention [36] [34] | Up to 14 days at RT [36] | 1.66 ng/mL [34] | Good stability, compatible with DNA and RNA preservation | 49.4% increase in cfDNA yield over 7 days [34] |

| Norgen | Osmotic cell stabilization [36] [34] | Up to 30 days at RT [36] | 0.76 ng/mL [34] | Longest stability, compatible with DNA and RNA preservation | Lowest initial cfDNA yield, requires single centrifugation only [34] |

Plasma Processing Protocol

Proper plasma processing is essential to prevent contamination by genomic DNA from lysed leukocytes. The following protocol is optimized for cfDNA preservation and purity:

Materials

- Selected blood collection tubes (from Table 1)

- Centrifuge with swing-out rotor and temperature control

- Sterile pipettes and aerosol-resistant tips

- Polypropylene tubes for plasma storage (e.g., Eppendorf Safe-Lock tubes)

- -80°C freezer for plasma storage

Method

Initial Centrifugation:

Plasma Transfer:

- Carefully transfer the upper plasma layer to a fresh polypropylene tube using a sterile pipette, avoiding the buffy coat and platelet layer.

- Leave approximately 0.5 cm of plasma above the buffy coat to prevent cellular contamination.

Secondary Centrifugation:

- Centrifuge the transferred plasma at 6000 × g for 10 minutes at 20°C [35].

- This step removes residual cells and platelets that could contaminate the cfDNA with genomic DNA.

Plasma Aliquoting and Storage:

- Transfer the supernatant to fresh tubes in small aliquots (recommended: 0.5-1 mL) to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Store plasma at -80°C within 30 minutes of the second centrifugation [35].

Critical Considerations

- Processing Time: K2EDTA tubes show significant increases in cfDNA concentration over time (7.39 ng/mL at 48h, 68.19 ng/mL at 168h) due to leukocyte lysis, emphasizing the need for rapid processing [34].

- Centrifugation Conditions: The number of centrifugation steps affects yield. For K2EDTA, Norgen, and PAXgene tubes, a single centrifugation yields higher cfDNA concentrations than double centrifugation [34].

- Temperature Control: Maintain consistent temperature during processing (typically 20°C) to prevent cell lysis.

cfDNA Extraction Methods

Comparison of Extraction Technologies

Multiple cfDNA extraction technologies are available, each with different binding chemistries, efficiencies, and size selectivities. The recovery efficiency and characteristics of these methods directly impact downstream analysis sensitivity, particularly for detecting low-frequency mutations in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA).

Table 2: Performance Comparison of cfDNA Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | Technology | Relative Yield | Processing Time | Size Selectivity | Automation Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (QiaS) | Spin column (silica membrane) [35] | Highest yield [35] | Standard (∼1-2 hours) | Broad range (50-800 bp) [35] | Limited (vacuum manifold) [35] |

| PHASIFY MAX | Liquid-phase (aqueous two-phase system) [37] | 60% increase vs. QiaS [37] | Standard | Enhanced recovery of small fragments [37] | No |

| PHASIFY ENRICH | Liquid-phase with size selection [37] | 35% decrease vs. QiaS [37] | Standard | Enriches fragments <500 bp [37] | No |

| Magnetic Bead with DMS | Magnetic beads with homobifunctional crosslinker [38] | 56% increase vs. QiaS [38] | Rapid (10 minutes) [38] | Preferentially binds small DNA fragments | Yes |

| MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit (TFiM) | Magnetic beads (silica) [35] | Moderate yield [35] | Standard | Broad range | Yes [35] |

| NucleoSpin Plasma XS (MNaS) | Spin column [35] | Lowest yield [35] | Standard | Small input volume (240μL) | No |

Detailed cfDNA Extraction Protocol: QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit

This protocol represents the current gold standard for manual cfDNA extraction, providing high yield and reproducibility [35]. The procedure is optimized for 1-4 mL of plasma as starting material.

Materials

- QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen)

- Water bath or heating block (set to 60°C)

- Microcentrifuge

- Vacuum manifold (QIAvac 24 Plus) with vacuum pump

- Proteinase K

- Carrier RNA

- Ethanol (96-100%)

- Buffer ACL

- Buffer ACB

- Wash Buffer AW1

- Wash Buffer AW2

Method

Lysis Procedure:

- Thaw frozen plasma samples at room temperature or in a refrigerator overnight.

- Prepare lysis buffer (Buffer ACL) with 1 μg carrier RNA per 1 mL plasma to enhance recovery of low-abundance cfDNA.

- In a 15 mL conical tube, add plasma (1-4 mL), then add Proteinase K solution (volume = 1/10 plasma volume), and Buffer ACL (volume = 4/5 plasma volume).

- Vortex for 30 seconds to mix thoroughly.

- Incubate at 60°C for 30 minutes to digest proteins and nucleases.

Binding Conditions Setup:

- Add Binding Buffer ACB (volume = 9/5 plasma volume) to the lysate.

- Vortex for 30 seconds and incubate on ice for 5 minutes to optimize DNA binding conditions.

- The final mixture volume will range from 1.85 mL (for 0.5 mL plasma) to 3.70 mL (for 1 mL plasma).

cfDNA Binding to Silica Membrane:

- Assemble the spin column with extender on the QIAvac 24 Plus manifold.

- Apply the mixture to the spin column and apply vacuum until all liquid passes through the membrane.

- This step binds cfDNA to the silica membrane while contaminants pass through.

Wash Steps:

- Add 600 μL of Wash Buffer AW1 to the column and apply vacuum.

- Add 600 μL of Wash Buffer AW2 to the column and apply vacuum.

- Add 250 μL of ethanol (96-100%) to the column and apply vacuum to dry the membrane completely.

Elution:

- Place the column in a clean 2 mL collection tube and centrifuge at full speed (≥20,000 × g) for 3 minutes to remove residual ethanol.

- Transfer the column to a new 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Apply 20-80 μL of Buffer AVE (elution buffer) to the center of the membrane.

- Incubate at room temperature for 3-5 minutes.

- Centrifuge at full speed for 1 minute to elute the cfDNA.

Storage:

- Store isolated cfDNA at -20°C in DNA LoBind tubes to prevent adsorption and degradation.

Protocol Modifications for Other Methods

For PHASIFY Methods [37]:

- The PHASIFY MAX method utilizes a series of aqueous two-phase systems (ATPSs) that partition cfDNA into specific phases based on optimized electrostatic, hydrophilic/hydrophobic, and excluded-volume interactions.

- The PHASIFY ENRICH method incorporates an additional size-selection step using ATPS components that preferentially precipitate large molecular weight DNA (>500 bp), enriching for smaller cfDNA fragments.

For Magnetic Bead with DMS Method [38]:

- This rapid method utilizes dimethyl suberimidate (DMS) as a homobifunctional crosslinker that binds cfDNA through covalent or electrostatic bonding.

- The DMS-DNA complexes are then captured by amine-conjugated magnetic beads, washed, and eluted under alkaline conditions (pH 10.3) to break the crosslinking.

Quality Control and Normalization

Assessment of Extraction Efficiency and Purity

Robust quality control is essential to ensure cfDNA quality and suitability for downstream applications such as droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) or next-generation sequencing (NGS).

Quantification Methods

- Fluorometric Methods (Qubit): Provide sensitive, DNA-specific quantification but no size information [35].

- qPCR Assays: Offer high sensitivity and the ability to assess fragment size distribution through amplification of targets of different lengths [34].

- Bioanalyzer/TapeStation: Provide fragment size distribution profiles, confirming the expected nucleosomal pattern (peaks at ∼166 bp) and assessing genomic DNA contamination [36] [35].

Assessment of Contaminating Genomic DNA

- Long vs. Short qPCR Assays: Compare amplification of short targets (∼60-80 bp, representative of cfDNA) versus long targets (>200 bp, indicative of high molecular weight genomic DNA) [34].

- Capillary Electrophoresis: Visualize the size distribution profile; a prominent high molecular weight fraction indicates genomic DNA contamination [34].

Spike-in Controls for Normalization

- Synthetic spike-in controls, such as the 180 bp CEREBIS (Construct to Evaluate the Recovery Efficiency of cfDNA extraction and Bisulphite modification) fragment, can be added to samples before extraction to determine and normalize for extraction efficiency [39].

- Studies show extraction efficiencies are method-specific: 84.1% (± 8.17) for the QIAamp kit in plasma, 58.7% (± 11.1) for the Zymo Urine Kit, and 30.2% (± 13.2) for the Q Sepharose protocol [39].

Technical and Biological Variability

Understanding sources of variability is crucial for experimental design and data interpretation:

- Technical Variability: The largest proportion of technical variance in plasma cfDNA extraction is attributed to intra-extraction variability and ddPCR measurement triplicates [39].

- Biological Variability: In both plasma and urine, inter-individual variability comprises the largest proportion of total variance, substantially exceeding technical variability [39].

- Normalization Strategies: For urinary cfDNA, creatinine normalization reduces variability, while CEREBIS-based extraction efficiency normalization shows benefit primarily when comparing different extraction methods [39].

Workflow Visualization

Liquid Biopsy Pre-analytical Workflow: This diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow from blood collection to downstream analysis, highlighting critical decision points at each stage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for cfDNA Analysis

| Category | Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection | K2EDTA/K3EDTA Tubes | Standard blood collection for immediate processing | Process within 1-2 hours to prevent gDNA contamination [33] [35] |

| Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT | Blood collection with preservative for delayed processing | Enables room temperature storage for up to 7 days [36] [34] | |

| PAXgene Blood ccfDNA Tubes | Blood collection with apoptosis inhibition | Compatible with DNA and RNA analysis, 14-day stability [36] | |

| cfDNA Extraction | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit | Silica-membrane based cfDNA extraction | Highest yield, spin-column technology [35] |

| PHASIFY MAX/ENRICH Kits | Liquid-phase extraction using aqueous two-phase systems | Enhanced recovery of small fragments, size-selection capability [37] | |

| MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit | Magnetic bead-based extraction | Amenable to automation, moderate yield [35] | |

| DMS (Dimethyl Suberimidate) | Homobifunctional crosslinker for bead-based extraction | Rapid processing (10 minutes), 56% higher efficiency than QIAamp [38] | |

| Quality Control | Qubit Fluorometer with dsDNA HS Assay | Fluorometric quantification of cfDNA | DNA-specific quantification, sensitive to 10 pg/μL [35] |

| Bioanalyzer/TapeStation with High-Sensitivity DNA Kit | Fragment size distribution analysis | Confirms nucleosomal pattern, detects gDNA contamination [36] [35] | |

| CEREBIS Spike-in Control | Synthetic DNA fragment for extraction efficiency normalization | 180 bp fragment mimics mononucleosomal cfDNA [39] | |

| Downstream Analysis | Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Absolute quantification of rare mutations | High sensitivity for low-frequency variants [37] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Comprehensive mutation profiling | Requires high-quality, pure cfDNA with minimal gDNA contamination [40] | |

| PROTAC EED degrader-1 | PROTAC EED degrader-1, MF:C55H60FN11O8S, MW:1054.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| ATX inhibitor 5 | ATX inhibitor 5, MF:C22H18ClF3N6O, MW:474.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The pre-analytical phase of liquid biopsy testing represents a critical determinant of success in cancer monitoring research. Standardization of blood collection, processing, and cfDNA extraction protocols is essential to minimize technical variability and ensure reproducible, reliable results. Key considerations include:

- Tube Selection: Match collection tubes to logistical constraints, prioritizing preservative tubes when immediate processing is not feasible.

- Processing Conditions: Adhere to standardized centrifugation protocols and processing timelines to prevent genomic DNA contamination.

- Extraction Method Selection: Choose extraction methods based on required yield, fragment size selectivity, and downstream application needs.

- Quality Control: Implement rigorous QC measures including spike-in controls for normalization and multiple assessment methods to verify cfDNA quality and quantity.

By adhering to these detailed protocols and considerations, researchers can significantly reduce pre-analytical variability, enhancing the sensitivity and reliability of liquid biopsy applications in cancer research and drug development.

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP) Assays for Actionable Variant Detection

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP) represents a next-generation sequencing (NGS) approach that uses a single assay to assess hundreds of cancer-related genes simultaneously. In the context of liquid biopsy workflows, CGP enables the minimally invasive detection of actionable variants from circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and other blood-based biomarkers, providing crucial insights for cancer monitoring research [41] [42]. Liquid biopsy focuses on the analysis of circulating tumor biomarkers from bodily fluids such as blood, offering a dynamic window into tumor heterogeneity and evolution without the need for invasive tissue sampling [43]. This approach is particularly valuable for tracking cancer progression, monitoring therapeutic responses, and detecting minimal residual disease (MRD) through serial sampling [42] [43].

Table 1: Key Biomarkers in Liquid Biopsy for Comprehensive Genomic Profiling

| Biomarker | Description | Role in CGP | Approximate Abundance in Blood |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) | Fragmented DNA released from tumor cells into circulation | Detection of somatic mutations, CNVs, fusions; monitoring tumor burden | 0.1-1.0% of total cell-free DNA [42] |

| Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) | Intact tumor cells shed into bloodstream | Analysis of whole genomes, transcriptomes; functional studies | ~1 CTC per 1 million leukocytes [42] |