Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling with LigandScout: A Comprehensive Workflow for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to ligand-based pharmacophore modeling using LigandScout, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling with LigandScout: A Comprehensive Workflow for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to ligand-based pharmacophore modeling using LigandScout, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of extracting essential chemical features from a set of known active ligands to create a 3D pharmacophore model. The scope includes a detailed, step-by-step methodological workflow for building and applying models in virtual screening, practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing model quality, and rigorous techniques for validating model performance and comparing it to other computational methods. The integration of these four intents offers a complete framework for leveraging LigandScout to efficiently identify novel hit compounds in the drug discovery pipeline.

Understanding Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: Core Concepts and Prerequisites

The pharmacophore concept stands as one of the most enduring and fundamental frameworks in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. It provides an abstract representation of the molecular features essential for a compound to elicit a specific biological response through interactions with a biological target. According to the modern IUPAC definition, a pharmacophore is "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1]. This definition emphasizes that a pharmacophore is not a specific molecule or functional group, but rather an abstract concept that captures the common molecular interaction capacities of a group of compounds toward their target structure [2]. This article traces the historical evolution of this concept, details its contemporary applications in computational drug discovery, and provides specific experimental protocols for ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, with particular emphasis on workflows utilizing LigandScout software within a broader thesis research context.

Historical Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept

The conceptual foundation of the pharmacophore was laid by Paul Ehrlich in the late 19th century, who defined it as "a molecular framework that carries (phoros) the essential features responsible for a drug's (pharmacon) biological activity" [3]. Although Ehrlich himself used the term "toxophore" rather than "pharmacophore" in his 1898 paper to describe the features of a molecule responsible for biological effects, his work established the core principle that specific chemical groups are responsible for binding and subsequent biological effects [4]. For many years, the origin of the pharmacophore concept was erroneously credited to Ehrlich due to a misattribution, while the modern term was actually popularized by Lemont B. Kier in a series of publications between 1967 and 1971 [5] [4]. The concept underwent a critical transformation in 1960 when F. W. Schueler extended it beyond specific chemical groups to spatial patterns of abstract features in his book "Chemobiodynamics and Drug Design," forming the basis for the contemporary IUPAC definition [4]. This evolution reflects a shift from thinking about concrete chemical groups to abstract patterns of features responsible for molecular recognition.

Table: Historical Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept

| Time Period | Key Contributor | Conceptual Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Late 19th Century | Paul Ehrlich | Introduced precursor concept of "toxophore" as features responsible for biological effects [4] |

| 1960 | F. W. Schueler | Extended concept to spatial patterns of abstract features, moving beyond specific chemical groups [4] |

| 1967-1971 | Lemont B. Kier | Popularized the term "pharmacophore" in modern sense through publications [5] |

| 1998 | IUPAC | Formalized standard definition as "ensemble of steric and electronic features" [1] |

| 2015 | IUPAC | Reaffirmed and updated definition in computational drug design terminology [1] |

Core Features and Methodological Foundations

Essential Pharmacophore Features

A pharmacophore model consists of a three-dimensional arrangement of chemical features that a ligand must possess to effectively bind to its biological target. These features represent the key interaction points between the ligand and the target protein's active site. The core features include [5]:

- Hydrophobic areas (H): Represent regions of the molecule that participate in hydrophobic interactions, often corresponding to aliphatic chains or aromatic ring systems.

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA): Atoms that can act as acceptors in hydrogen bond formation, typically oxygen or nitrogen atoms with lone electron pairs.

- Hydrogen bond donors (HBD): Groups containing a hydrogen atom bonded to an electronegative atom (like O-H or N-H) that can donate a hydrogen bond.

- Aromatic rings (AR): Planar ring systems that can participate in cation-π or π-π stacking interactions.

- Positively/negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI): Functional groups that can carry positive or negative charges under physiological conditions, enabling electrostatic interactions.

These features need to match different chemical groups with similar properties to identify novel ligands, making pharmacophore models powerful tools for scaffold hopping and virtual screening [5].

Pharmacophore Model Development Workflow

The standard workflow for developing a ligand-based pharmacophore model involves several methodical stages [5]:

- Training Set Selection: A structurally diverse set of known active molecules is selected, ideally including both active and inactive compounds to define essential features.

- Conformational Analysis: For each molecule in the training set, a set of low-energy conformations is generated, which should include the potential bioactive conformation.

- Molecular Superimposition: Multiple low-energy conformations of the molecules are superimposed to identify the best spatial alignment of common pharmacophore features.

- Feature Abstraction: The aligned molecular structures are transformed into an abstract representation using generalized pharmacophore features (e.g., hydrogen-bond donors, hydrophobic areas).

- Model Validation: The pharmacophore hypothesis is validated by testing its ability to discriminate between known active and inactive compounds, often using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling with LigandScout: Protocols and Applications

Experimental Protocol: Ligand-Based Model Generation

Purpose: To create a validated ligand-based pharmacophore model using LigandScout for virtual screening of novel bioactive compounds. Software Requirement: LigandScout 4.3 or higher [6]. Input Materials: A set of 10-30 known active compounds with demonstrated activity against the target of interest, along with decoy molecules for validation.

Procedure:

- Training Set Preparation:

- Collect 3D structures of known active compounds in SDF or MOL2 format.

- Ensure structural diversity while maintaining comparable potency ranges (ideally within 2 log units of IC50/Ki values).

- Include known inactive compounds (or decoys) for model validation.

Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- Import all active compounds into LigandScout.

- Access the "Create Pharmacophore from Ligands" function.

- Adjust algorithm parameters: set feature tolerance to 1.5-2.0 Å, energy threshold to 20 kcal/mol above global minimum.

- Run the multiple alignment and feature detection algorithm.

- Generate 10-15 alternative pharmacophore hypotheses.

Model Selection and Validation:

- Evaluate generated models using built-in ROC curve analysis.

- Select the model with the highest area under curve (AUC) value (≥0.7 indicates acceptable discrimination) [6].

- Validate model specificity using a test set of active and inactive compounds not included in training.

- Manually refine features if necessary, removing redundant or poorly positioned features.

Virtual Screening Application:

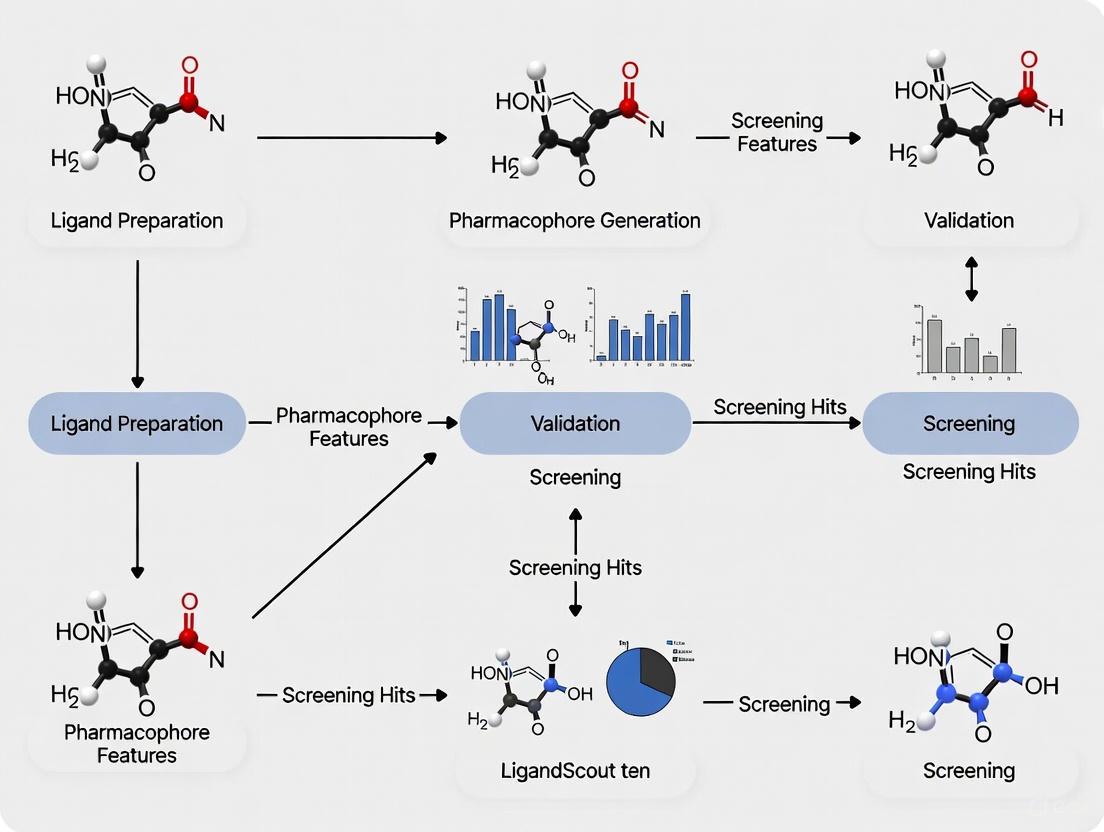

Diagram 1: Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening workflow

Case Study: Dual Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Discovery

A 2020 study demonstrated the application of ligand-based pharmacophore modeling for identifying dual tyrosine kinase inhibitors of EGFR and VEGFR2 [6]. Researchers developed separate pharmacophore models for each target using LigandScout 4.3. The EGFR pharmacophore consisted of one hydrophobic group, three aromatic rings, two hydrogen bond acceptors, and one hydrogen bond donor, while the VEGFR2 model contained one hydrophobic group, one aromatic ring, one hydrogen bond acceptor, and one hydrogen bond donor [6]. Sequential screening of the ZINC database with both models identified 6,896 compounds satisfying both pharmacophore requirements. Subsequent molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations refined these to two promising compounds (ZINC16525481 and ZINC38484632) that demonstrated stable binding interactions with both targets [6]. This case highlights the power of pharmacophore approaches for multi-target drug discovery.

Case Study: 17β-HSD2 Inhibitor Identification

In a 2014 study, ligand-based pharmacophore models were constructed to identify novel inhibitors of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (17β-HSD2), a target for osteoporosis treatment [7]. Three complementary pharmacophore models were developed based on common chemical features of known active compounds. These models successfully retrieved 87% of active compounds from a test set while excluding inactive compounds. Virtual screening of the SPECS database (containing 202,906 compounds) followed by Lipinski filtering identified 1,381 druglike hits [7]. Experimental validation of 29 selected compounds revealed 7 active inhibitors with low micromolar IC50 values, demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach for scaffold hopping and lead identification.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software Platform | Pharmacophore model generation, validation, and virtual screening | [6] |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | Source of purchasable compounds for virtual screening | [8] [6] |

| SPECS Database | Compound Library | Commercial database of diverse chemical structures | [7] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Structural Database | Source of 3D protein structures for structure-based modeling | [2] |

| Known Active Compounds | Chemical Structures | Training set for ligand-based model development | [7] [6] |

Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Virtual Screening and Scaffold Hopping

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents one of the primary applications of pharmacophore models in drug discovery. By using a pharmacophore as a query to search large chemical databases, researchers can identify structurally diverse compounds that share the essential features required for biological activity [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for scaffold hopping - identifying novel core structures (scaffolds) that maintain similar biological activity to known active compounds [9]. Successful scaffold hopping can lead to compounds with improved pharmacokinetic properties, reduced toxicity, or the ability to circumvent existing patents [9]. Traditional methods for scaffold hopping utilize molecular fingerprinting and structural similarity searches, while modern AI-driven approaches employ graph neural networks and generative models to explore broader chemical spaces [9].

Integration with Structure-Based Methods and Molecular Docking

While ligand-based approaches rely solely on known active compounds, structure-based pharmacophore modeling utilizes 3D structural information of the target protein, typically from X-ray crystallography or homology models [2] [3]. These complementary approaches can be integrated to enhance the reliability of virtual screening. In practice, pharmacophore models often serve as pre-filters before more computationally intensive molecular docking simulations [6]. This hierarchical approach significantly reduces the number of compounds subjected to docking while maintaining sensitivity for identifying true active compounds. The combination of pharmacophore screening and molecular docking has proven effective in numerous drug discovery campaigns, including the identification of novel antimicrobial compounds targeting DNA gyrase [8] and dual inhibitors of tyrosine kinases [6].

Diagram 2: Integrated drug discovery screening workflow combining multiple computational approaches

The pharmacophore concept has evolved significantly from Ehrlich's early ideas to the sophisticated computational tools used in modern drug discovery. The IUPAC definition now provides a standardized framework for understanding and applying this fundamental concept. Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, particularly when implemented using tools like LigandScout, offers a powerful methodology for identifying novel bioactive compounds through virtual screening and scaffold hopping. The integration of pharmacophore approaches with other computational techniques such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations creates a robust pipeline for accelerating drug discovery. As AI-driven molecular representation methods continue to advance, pharmacophore modeling will likely remain a cornerstone of computational drug design, enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space and identification of therapeutic agents for challenging drug targets.

In the landscape of computational drug discovery, researchers primarily utilize two methodological paradigms: structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD). While structure-based methods rely on the availability of the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, ligand-based strategies infer binding characteristics and biological activity from the structural and physicochemical properties of known active molecules [10]. This application note delineates the specific scenarios where a ligand-based approach is not merely an alternative, but the most rational and effective choice. This is particularly pertinent within a workflow utilizing LigandScout for advanced pharmacophore modeling, where the chemical information from active ligands can be transformed into powerful, predictive three-dimensional queries for virtual screening [7] [11] [12].

The core principle underpinning LBDD is the "molecular similarity principle," which posits that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [12]. This principle enables researchers to build predictive models even in the absence of direct structural information about the biological target, making LBDD an indispensable tool in the early stages of drug discovery.

Key Scenarios for Selecting a Ligand-Based Approach

The decision to employ a ligand-based approach is strategic and should be guided by the specific context of the research project and the available data. The following scenarios represent conditions where LBDD is particularly advantageous.

Table 1: Scenarios Favoring a Ligand-Based Approach

| Scenario | Rationale | Recommended LBDD Method |

|---|---|---|

| No 3D protein structure available | SBDD is not feasible without a protein structure from X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, or a reliable homology model [10]. | Pharmacophore modeling, QSAR [10] [13]. |

| Target is structurally elusive or difficult to model | For membrane proteins (e.g., GPCRs) or highly flexible targets where obtaining a stable structure is challenging [12]. | Molecular similarity search, QSAR, pharmacophore modeling. |

| Requirement for high-speed virtual screening | LBDD methods like similarity searching and pharmacophore screening are computationally faster, allowing for the rapid filtering of large libraries [10] [12]. | 2D/3D similarity screening, pharmacophore screening. |

| Availability of abundant ligand structure-activity data | When a set of known active (and inactive) compounds is available, this data can be leveraged to build robust predictive models [10] [13]. | QSAR, Pharmacophore modeling. |

| Scaffold hopping to discover novel chemotypes | To identify structurally diverse compounds that retain biological activity, thereby helping to overcome patent limitations or improve drug-like properties [9]. | 3D pharmacophore screening, shape-based similarity. |

Ligand-based approaches are not only a fallback when structural data is missing but a primary choice for specific objectives. A primary scenario is the absence of a reliable 3D protein structure. When the target's structure is unknown, experimentally undetermined, or predicted with low confidence (e.g., via homology modeling), SBDD methods like molecular docking cannot be reliably applied [10]. In such cases, LBDD becomes the foundational computational strategy.

Furthermore, LBDD excels in scaffold hopping, a process aimed at discovering new core structures (scaffolds) that retain the biological activity of a known lead compound [9]. This is crucial for designing novel chemical entities that circumvent existing patents or for optimizing lead compounds to improve their pharmacokinetic and safety profiles. Because pharmacophore models capture the essential, abstract features necessary for bioactivity—such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors and hydrophobic regions—they can identify molecules with different backbone structures that still fulfill these fundamental interaction criteria [9] [6].

Finally, the speed and scalability of many LBDD methods make them ideal for the initial screening of ultralarge chemical libraries. Techniques like 2D fingerprint similarity searching or pharmacophore screening can rapidly prioritize a manageable number of candidates from millions of compounds, which can subsequently be processed with more computationally intensive structure-based methods [10] [12] [14]. This sequential integration optimizes resource allocation in virtual screening campaigns.

Integrating Ligand-Based and Structure-Based Methods

While powerful on its own, LBDD often reveals its full potential when integrated with SBDD in a combined virtual screening workflow. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both paradigms to improve the efficiency and success rate of hit identification [12].

A common and effective strategy is the sequential approach, where a large compound library is first filtered using a fast ligand-based method, and the resulting subset is then analyzed with a more computationally demanding structure-based technique [10] [12]. For instance, a pharmacophore model can reduce a multi-million compound library to a few thousand hits, which are then subjected to molecular docking. This workflow balances speed with the detailed insight provided by protein-ligand interactions, ensuring that computational resources are focused on the most promising candidates [12].

Diagram: Sequential Virtual Screening Workflow

An alternative is the parallel screening approach, where both LBDD and SBDD are run independently on the same library. The results are then combined using a consensus scoring framework, which favors compounds that are ranked highly by both methods [10] [12]. This approach mitigates the inherent limitations of each method; for example, a true active might be missed by docking due to an inaccurate scoring function but recovered by a ligand-based similarity search.

Practical Application: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling with LigandScout

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for constructing and validating a ligand-based pharmacophore model using LigandScout software, a key component of the research workflow.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout Software | Advanced platform for creating and exploiting structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore models for virtual screening [6] [11]. | Core software for model building, optimization, and screening. |

| OMEGA Conformer Generator | Integrated tool for generating representative, energy-optimized 3D conformations for each input ligand [11]. | Essential for exploring ligand flexibility during model creation. |

| ZINC Database | A free public resource of commercially available compounds for virtual screening [6]. | Typical compound library screened against the pharmacophore model. |

| DUD-E Server | Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced; generates decoy molecules with similar physical properties but dissimilar chemical structures to actives [11]. | Used for model validation and benchmarking. |

| MMFF94 Force Field | A widely used force field for molecular mechanics energy minimization and conformational analysis [11]. | Used for 3D structure optimization of input ligands. |

Protocol: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation & Validation

Objective: To generate a validated ligand-based pharmacophore model from a set of active compounds and use it for virtual screening.

Materials and Software:

- LigandScout software (e.g., version 4.3 or higher) [6] [11].

- A set of 2-5 known active compounds with nanomolar inhibition activity [7] [11].

- A computer with sufficient RAM (≥ 8 GB recommended) for processing compound libraries.

Methodology:

Input Ligand Preparation:

Conformational Sampling:

- Use the OMEGA conformer generator within LigandScout to generate an ensemble of conformations for each active compound. Set parameters to generate a maximum of 500 unique conformations per molecule, with an RMS threshold for duplicate conformers of 0.4 Å [11]. This step is critical for capturing the flexible nature of the ligands.

Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- In the ligand-based module, dynamically align the generated conformations of the training set compounds.

- The software will produce multiple merged pharmacophore models. Select the model with the highest inbuilt score (e.g., >0.90), which combines pharmacophore fit and atom shape overlap [11]. The model will consist of features like Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA), Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD), Hydrophobic areas (H), and Aromatic Rings (AR), potentially with exclusion volumes (XVOL) [7].

Model Validation (Critical Step):

- To ensure the model can distinguish active from inactive compounds, perform a validation screening against a set of decoys.

- Use the DUD-E server to generate ~50 decoys per active compound by inputting the SMILES strings of the actives. Decoys have similar physicochemical properties but distinct 2D structures [11].

- Screen this validation set (actives + decoys) with your pharmacophore model. A good model will retrieve a high proportion of the known actives while excluding most decoys. Optimize the model's features (e.g., making some optional, adjusting tolerance radii) to maximize this enrichment [7] [11].

Virtual Screening:

- Apply the validated pharmacophore model to screen a large database of purchasable compounds (e.g., the ZINC database, SPECS database) [7] [6].

- The screening will output a "hit list" of compounds that match the pharmacophore features. These virtual hits are predicted to be active and can be prioritized for further computational analysis (e.g., molecular docking) or experimental testing [7] [6] [12].

Diagram: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Case Study: Discovery of 17β-HSD2 Inhibitors

A study aimed at discovering novel inhibitors for 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 (17β-HSD2) for osteoporosis treatment provides a compelling example of a successful ligand-based virtual screening campaign [7].

- Scenario: The 3D structure of 17β-HSD2 was unavailable, necessitating a ligand-based approach.

- Method: Researchers constructed multiple ligand-based pharmacophore models based on the common chemical features of structurally diverse known inhibitors. These models were refined to recognize active compounds from a test set while filtering out inactives [7].

- Validation: The combined models correctly identified 87% of the active compounds (sensitivity of 0.87) from the test set without retrieving any inactive compounds, demonstrating high specificity [7].

- Outcome: The models were used to screen the SPECS database (~202,900 compounds). From 29 compounds selected for experimental testing, 7 showed low micromolar inhibitory activity, with the most potent having an IC₅₀ of 240 nM. This highlights the power of the approach to identify novel, potent, and selective inhibitors from a large chemical space without any protein structural information [7].

Ligand-based approaches are a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, offering a powerful and often indispensable strategy for identifying and optimizing lead compounds. The decision to employ this methodology is strongly justified in scenarios where protein structural data is lacking, when high-speed screening is required, or when the project goal is scaffold hopping to explore novel chemical space. When integrated into a structured workflow using tools like LigandScout for pharmacophore modeling, and when combined with structure-based insights where possible, ligand-based drug design provides a robust pathway from chemical information to novel bioactive compounds, streamlining the early drug discovery pipeline.

In the field of computer-aided drug discovery, a pharmacophore is defined as the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger its biological response [15]. These features include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic areas (H), and aromatic rings (Ar) [15]. In ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, which is employed when the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable, these features are derived from the structural alignment and analysis of known active compounds [15]. This application note details the role of these essential features within a LigandScout workflow, providing validated protocols for their identification and application in virtual screening.

The following table summarizes the core pharmacophore features, their geometric properties, and functional roles in molecular interactions.

Table 1: Essential Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature | Symbol | Geometric Representation | Functional Role in Binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | HBA | Vector (Directional) | Forms electrostatic interactions with hydrogen bond donors in the protein target, often with backbone or side-chain NH groups [15]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | HBD | Vector (Directional) | Forms electrostatic interactions with hydrogen bond acceptors in the protein target, such as carbonyl oxygen atoms [15]. |

| Hydrophobic Area | H | Sphere (Volume) | Drives binding through van der Waals interactions and desolvation effects, often with aliphatic or aromatic side chains [15]. |

| Aromatic Ring | Ar | Sphere or Plane (Volume) | Enables π-π stacking, cation-π, and amide-π interactions with protein residues like phenylalanine, tyrosine, or histidine [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Protocol 1: Common Feature Pharmacophore Generation with LigandScout

This protocol describes the generation of a shared-feature pharmacophore model using multiple known active ligands, a common step in lead identification and optimization [8] [16].

Step 1: Training Set Selection and Preparation

- Objective: Curate a set of known active compounds with diverse structures but common biological activity.

- Procedure:

- Identify and select 3-5 known active compounds. For example, in a study on fluoroquinolone antibiotics, Ciprofloxacin, Delafloxacin, Levofloxacin, and Ofloxacin were used [8].

- Retrieve their 3D structures in SDF (Structure Data File) format from databases like PubChem [16].

- Import the SDF files into LigandScout.

Step 2: Conformational Analysis

Step 3: Common Feature Pharmacophore Generation

- Objective: Identify and model the spatial arrangement of chemical features common to all active compounds.

- Procedure:

- Initiate the "create Ligand-based pharmacophore" process in LigandScout [16].

- Based on chemical structure alignment, the software will generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses.

- Select the model with the highest pharmacophoric fitting score and the best coverage of key features (HBA, HBD, H, Ar) [8] [16].

- Use the "merged features" option to consolidate features across different conformers and ligands. A robust model is often indicated by a high Goodness-of-Hit (GH) score (e.g., 0.739) [16].

- For increased selectivity, consider adding exclusion volumes to define regions in space that are occupied by the receptor and thus forbidden for ligands [17].

Protocol 2: Virtual Screening with a Validated Pharmacophore Model

This protocol uses a generated pharmacophore model to screen large compound libraries and identify novel hit candidates.

Step 1: Database Preparation

Step 2: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

- Objective: Identify compounds that match the essential chemical features of the pharmacophore model.

- Procedure:

- Use the pharmacophore as a 3D search query to screen the database.

- The software will return a list of "hits" that fit the model. For example, a study screened 160,000 compounds and identified 25 initial hits with high fit scores (97.85 to 116) and low RMSD values (0.28 to 0.63) [8].

Step 3: Post-Screening Analysis

- Objective: Filter and prioritize hits for further investigation.

- Procedure:

- Apply drug-likeness filters such as Lipinski's Rule of Five to assess the oral bioavailability potential of the hits [8].

- Analyze the physicochemical properties and scaffold of the top hits to ensure novelty and desired properties.

- Subject the filtered hits to molecular docking against the target protein (if structure is available) to evaluate binding pose and affinity, using the original active compound (e.g., Ciprofloxacin) as a control [8].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening using LigandScout.

Diagram 1: Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and screening workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table lists essential software tools and databases used in a typical ligand-based pharmacophore modeling workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Workflow | Access/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Primary platform for generating and analyzing ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore models, and performing virtual screening [16] [18] [17]. | Commercial (Inte:Ligand) |

| PubChem | Database | Public repository to retrieve 2D and 3D structural information (SDF files) of known active compounds for the training set [16]. | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| ZINC/ ZINCPharmer | Database & Tool | A publicly available database of commercially compounds, integrated with the Pharmit web server for pharmacophore-based screening [8] [16]. | https://zincpharmer.csb.pitt.edu/ |

| Pharmit | Online Tool | An interactive online platform for pharmacophore-based and shape-based virtual screening of large compound libraries [19]. | https://pharmit.csb.pitt.edu |

| OMEGA | Software (Conformational Generator) | Integrated within LigandScout to generate a representative ensemble of low-energy 3D conformations for each ligand in the training set [17]. | Part of LigandScout |

The table below summarizes quantitative results from two recent studies that successfully applied the described workflow to identify novel antimicrobial compounds.

Table 3: Case Study Applications of the Pharmacophore Workflow

| Study Target | Training Set Ligands | Key Pharmacophore Features | Screening Results | Top Identified Candidate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics [8] | Ciprofloxacin, Delafloxacin, Levofloxacin, Ofloxacin | Hydrophobic, HBA, HBD, Aromatic rings [8] | 25 hits from 160,000 compounds; Docking scores: -7.3 to -7.4 kcal/mol [8] | ZINC26740199 (Docking: -7.4 kcal/mol; passed drug-likeness) [8] |

| Cephalosporin Antibiotics [16] | Cephalothin, Ceftriaxone, Cefotaxime | HBA, HBD, Aromatic rings, Hydrophobic, Negative ionizable [16] | 7 promising candidates identified; Model GH Score: 0.739 [16] | Molecule 23 & Molecule 5 (Superior binding to PBP) [16] |

In the ligand-based pharmacophore modeling workflow, the assembly and curation of a training set of active ligands is a critical foundational step that profoundly influences the success and predictive power of the resulting model. Within the LigandScout framework, a pharmacophore represents a three-dimensional arrangement of chemical features—such as hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic areas, and aromatic rings—essential for a ligand's biological activity [20] [21]. When structural data for the biological target is unavailable, deriving these models from a set of known active ligands becomes the primary strategy [22]. The quality, diversity, and representativeness of the training set directly determine the model's ability to identify genuine actives during virtual screening while avoiding false positives. This protocol details the systematic procedure for constructing a robust training set, a prerequisite for generating a shared-feature pharmacophore in LigandScout that accurately captures the essential interaction patterns required for binding.

Theoretical Foundations of Training Set Composition

A well-curated training set should embody several key principles to ensure the derived pharmacophore model is both discriminating and generalizable.

Principles of Training Set Selection

- Activity and Selectivity: All ligands selected for the training set must demonstrate confirmed biological activity against the target of interest. Preferably, quantitative activity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) should be available to prioritize the most potent compounds for model generation [23].

- Structural Diversity: The set must encompass a broad range of core scaffolds and chemical classes. This diversity ensures the resulting model identifies the essential common features responsible for activity, rather than memorizing specific structural motifs. As demonstrated in a study on fluoroquinolone antibiotics, using diverse ligands like Ciprofloxacin, Delafloxacin, Levofloxacin, and Ofloxacin helps in mapping a comprehensive pharmacophore [8].

- Feature Representativeness: The chosen ligands must collectively present all the chemical features hypothesized to be critical for target interaction. A comprehensive pharmacophore model typically accounts for hydrogen-bond donors (HBD), hydrogen-bond acceptors (HBA), hydrophobic regions (Hy), aromatic rings (Ar), and ionizable groups [21] [24].

Table 1: Key Chemical Features in Pharmacophore Modeling and Their Descriptions

| Pharmacophore Feature | Atomic/Functional Group Representatives | Role in Molecular Recognition |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Carbonyl oxygen, Nitrogens in heterocycles, Ethers | Forms hydrogen bonds with donor groups on the target protein. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Primary and secondary amines, Amides, Hydroxyls | Forms hydrogen bonds with acceptor groups on the target protein. |

| Hydrophobic (Hy) | Alkyl chains, Cycloalkanes, Aromatic rings | Engages in van der Waals interactions and desolvation. |

| Aromatic Ring (Ar) | Phenyl, Pyridine, Other heteroaromatic rings | Enables π-π and cation-π interactions. |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Primary, secondary, or tertiary amines (when protonated) | Engages in electrostatic interactions with negatively charged residues. |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Carboxylic acids, Tetrazoles, Phosphates | Engages in electrostatic interactions with positively charged residues. |

The Shared Feature Pharmacophore Model

LigandScout excels at creating a shared-feature pharmacophore from multiple aligned ligands [20]. This process involves superimposing the bioactive conformations of the training set ligands and identifying the spatial consensus of their chemical features. The final model is an abstraction of the indispensable interaction points common to all active compounds, effectively filtering out noise from individual ligand structures. This approach was central to a study that identified potential antimicrobial compounds by modeling shared features of fluoroquinolone antibiotics [8]. Advanced protocols for generating consensus models from large ligand sets, such as those using the ConPhar tool, further enhance model robustness by systematically integrating features from numerous ligand-target complexes [19].

Experimental Protocol: Assembling and Curating the Training Set

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for preparing a training set suitable for ligand-based pharmacophore modeling in LigandScout.

Step 1: Ligand Sourcing and Data Collection

Objective: To gather a comprehensive set of known active ligands from reliable data sources.

- Procedure:

- Query Public Databases: Extract structures and associated activity data from specialized chemical databases such as:

- Literature Mining: Collect compounds and their activity data from peer-reviewed publications relevant to the target of interest. For example, a study on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors started with 4,643 known inhibitors from the literature [23].

- Internal Compound Libraries: If available, include data from proprietary corporate or academic screening collections.

Technical Note: When exporting structures, ensure you retrieve the correct stereochemistry, as this significantly impacts 3D conformation and molecular alignment. Save the initial compound list in a standard format such as SDF or MOL2.

Step 2: Conformational Analysis and Generation

Objective: To generate a representative set of low-energy conformations for each ligand in the training set, as the bioactive conformation is typically unknown.

- Procedure:

- Select a Conformation Generation Method:

- Employ Conformer Generation Software: Use tools integrated within LigandScout or external applications like OMEGA, CONFGEN, or the conformer generation functions in MOE to produce an ensemble of conformers for each ligand.

- Set Generation Parameters:

- Energy Window: A common setting is 10-20 kcal/mol above the calculated global minimum energy to ensure coverage of biologically relevant conformations.

- Maximum Conformer Count: Limit the number of conformers per molecule (e.g., 50-100) to balance computational cost and coverage.

- Use RMSD Clustering: Apply a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) threshold to cluster and select diverse conformers, avoiding redundant structures.

Step 3: Ligand Alignment and Final Training Set Preparation

Objective: To align the generated conformers and select the optimal conformation for each ligand to represent its putative bioactive pose.

- Procedure:

- Molecular Alignment: Use the alignment algorithms within LigandScout, which are based on pharmacophoric feature points rather than chemical structure, to superimpose the training set molecules [20].

- Select a Representative Conformation: For each ligand, choose the conformation that best fits the emerging consensus of features from the aligned set. This often requires iterative refinement.

- Finalize the Training Set: The output of this step is a set of pre-aligned ligands in their putative bioactive conformations, saved in a format compatible with LigandScout (e.g., SDF). This curated set is now ready for pharmacophore model generation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Data Resources for Training Set Curation

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Training Set Curation |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software Platform | Creates 3D pharmacophores from aligned ligand sets; performs virtual screening [20] [21]. |

| ZINC Database | Chemical Database | Public source of commercially available compounds for virtual screening and training set assembly [8] [24]. |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity Database | Manually curated repository of bioactive molecules with quantitative data for selecting potent ligands. |

| PyMOL | Molecular Visualization | Aligns protein-ligand complexes and analyzes binding poses for structure-informed curation [19]. |

| ConPhar | Informatics Tool | Generates consensus pharmacophore models from extensive sets of ligand-target complexes [19]. |

| Pharmit | Online Tool | Interactive pharmacophore tool used to generate pharmacophore JSON files for further processing [19]. |

Quality Control and Validation

A rigorously curated training set must be validated before proceeding to pharmacophore generation.

Assessment of Training Set Composition

- Chemical Space Analysis: Employ techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or t-SNE on molecular descriptors (e.g., ECFP4 fingerprints) to visualize the structural diversity of the training set. The set should cover a broad chemical space, as demonstrated in the creation of the LigPhoreSet dataset [24].

- Pharmacophore Feature Audit: Manually verify that the aligned training set ligands collectively present a consistent and logical pattern of key features (HBA, HBD, Hy, etc.). The spatial arrangement should be sterically plausible.

Key Performance Metrics

- Fit Score and RMSD: When the model is generated, evaluate its quality by examining the fit scores and RMSD values of the training ligands to the model. A good model will have high fit scores and low RMSD values for its training compounds. For example, a successful virtual screening study reported fit scores from 97.85 to 116 and RMSD values from 0.28 to 0.63 for their top hits [8].

- Model Robustness: A robust training set enables the creation of a model that performs well in virtual screening, successfully identifying known active compounds not included in the training set (decoy set) while ranking them highly.

The meticulous assembly and curation of a training set of active ligands is an indispensable first step in the ligand-based pharmacophore modeling workflow. By adhering to the principles of activity, diversity, and feature representativeness, and by rigorously following the experimental protocol outlined herein, researchers can construct a high-quality training set. This foundation enables LigandScout to generate a pharmacophore model that accurately encapsulates the essential molecular interactions required for biological activity. Such a model is a powerful tool for streamlining virtual screening campaigns, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel lead compounds in drug development.

LigandScout is a specialized software platform for molecular modeling and design, developed by Inte:Ligand GmbH, which enables researchers to create three-dimensional (3D) pharmacophore models from structural data [20]. At its core, LigandScout provides a complete definition of 3D chemical features—such as hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, lipophilic areas, and positively or negatively ionizable chemical groups—that describe the interactions between a bound small organic molecule (ligand) and the surrounding binding site of a macromolecule [20]. The software is utilized primarily in drug design to predict new lead structures, exemplified by its successful application in predicting biological activity of novel HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors [20].

A key advancement is LigandScout Remote, an interface that seamlessly integrates high-performance computing (HPC) and cloud resources into the desktop application [25] [26]. This technology handles necessary data conversion and network communication transparently, eliminating traditional HPC usability barriers and allowing scientists to leverage powerful computing resources directly from the familiar LigandScout graphical interface without command-line expertise [25] [27].

Table 1: Key Capabilities of LigandScout

| Capability Category | Specific Features | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Automatic creation of 3D pharmacophores from protein-ligand complexes (SB) or sets of active molecules (LB); Advanced handling of co-factors, ions, and water molecules [28] [29]. | Identifies essential chemical interactions for virtual screening and drug design [20]. |

| Virtual Screening | Uses pharmacophores as filters for screening compound databases; Includes high-performance alignment algorithms [28]. | Rapid identification of potential hit compounds from large libraries (e.g., 202,906 molecules) [7]. |

| Molecular Alignment | Pattern-matching based alignment algorithm using pharmacophoric feature points [20]. | Superimposes molecules based on interaction patterns rather than chemical structure. |

| HPC Integration | LigandScout Remote for transparent access to cluster computing resources [25] [26]. | Accelerates computationally intensive tasks like large virtual screens without manual file handling. |

Experimental Protocols for Pharmacophore Modeling

LigandScout supports two primary approaches for creating pharmacophore models: Structure-Based (SB) and Ligand-Based (LB). The following protocols detail the methodologies for both, as applied in published research.

Structure-Based (SB) Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

This protocol is used when an experimentally determined 3D structure of the macromolecule (e.g., from PDB) is available [29].

- Input Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target macromolecule in complex with a ligand from a database such as the PDB.

- Automatic Pharmacophore Generation: The LigandScout algorithm automatically tags the key chemical features of the ligand that are interacting with residues of the receptor protein [29].

- Exclusion Volume Generation: An ensemble of exclusion volume spheres is generated to represent the shape of the protein's active site, which defines spatial regions that should not be occupied by a potential inhibitor [29].

- Model Validation: The generated model is typically validated by screening a set of known active and inactive compounds to assess its ability to discriminate between them.

Ligand-Based (LB) Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

This protocol is employed when the 3D structure of the target is unknown, and the model is derived from a set of known active ligands. The workflow below illustrates this multi-step process.

Detailed Steps:

- Data Set Curation: Gather known active and inactive compounds. Divide them into a training set (e.g., 75% of actives and inactives) and a test set (the remaining 25%) [29].

- Cluster Analysis: Cluster the active compounds in the training set using the i-cluster tool within LigandScout (default parameters: cluster_dis = 0.4 with average method) [29]. This groups molecules with similar structural properties.

- Conformational Generation: For each cluster, generate multiple low-energy conformations for each ligand using the ICON algorithm provided in LigandScout [29].

- Pharmacophore Creation and Ranking:

- Feature Alignment: The common features of the highest-ranking pharmacophores are aligned to all conformations of the next molecule in the set. This process iterates until all molecules in the cluster are processed, resulting in a final consensus LB-pharmacophore model for that cluster [29].

Pharmacophore Model Optimization Protocol

After generating SB or LB models, they must be refined and optimized for virtual screening.

- Initial Screening: Use the pharmacophore to screen the training set with the "Max. number of omitted features" parameter set to 0 [29].

- Identify Non-Essential Features:

- If the initial screening yields a high Positive Predictive Value (PPV), perform a second screening with "Max. number of omitted features" set to 1 [29].

- This helps identify features that are not critical for activity. These features can then be removed or set to "optional".

- Validation and Iteration:

- Perform a third screening with the modified pharmacophore (omitted features set back to 0).

- If the PPV increases, the change is validated. If it decreases, the pharmacophore is reverted, and other features are investigated [29].

- This protocol is repeated until three core pharmacophoric features are retained or no further non-essential features can be identified [29].

- Remove Redundancy: To create a concise and efficient screening library, redundant pharmacophores (those that do not retrieve unique hits) are identified and removed [29].

LigandScout Remote: Interface for High-Performance Computing

LigandScout Remote is designed to overcome the traditional usability barriers associated with HPC clusters [25]. It integrates these resources directly into the LigandScout desktop application, handling data conversion and network communication transparently [26]. This allows scientists to run large-scale virtual screens on HPC clusters or cloud resources (like Amazon Web Services) without manual preparation and transfer of input data or gathering of results, combining the usability of a local graphical application with the performance of HPC [25] [27].

Case Study: Application in Identifying 17β-HSD2 Inhibitors

A research study successfully used LigandScout's ligand-based pharmacophore modeling for virtual screening to discover inhibitors of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 (17β-HSD2), a target for osteoporosis treatment [7].

Table 2: Summary of Ligand-Based Virtual Screening Campaign for 17β-HSD2 Inhibitors

| Parameter | Description / Value |

|---|---|

| Target | 17β-HSD2 (for osteoporosis treatment) [7]. |

| Method | Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling with 3 complementary models [7]. |

| Training Set | Structurally diverse known active compounds (e.g., 5, 6, 7, 8) [7]. |

| Test Set | 15 active and 30 inactive compounds [7]. |

| Virtual Screen | SPECS database (202,906 compounds) [7]. |

| Screening Hits | Model 1: 573 hits; Model 2: 825 hits; Model 3: 318 hits (1,716 total, 1,381 after druglikeness filtering) [7]. |

| Experimental Validation | 29 compounds tested in vitro; 7 showed low micromolar IC₅₀ values [7]. |

| Most Potent Hit | Compound 12 (IC₅₀ = 240 nM) [7]. |

Experimental Workflow and Outcome:

- Model Construction: Three restrictive pharmacophore models were built, each based on the common chemical features of two training compounds [7].

- Model Validation: The models were validated against a test set containing 15 active and 30 inactive compounds. The combined models correctly identified 13 of the 15 active compounds (sensitivity of 0.87) without retrieving any false positives (no inactive compounds) [7].

- Virtual Screening: The models screened a large commercial database. The hit lists were filtered using a modified Lipinski rule to ensure druglikeness, yielding 1,381 unique candidates [7].

- Hit Identification: From the virtual hits, 29 compounds were biologically evaluated. This led to the identification of 7 new inhibitors with low micromolar potency, demonstrating the effectiveness of the LigandScout-generated pharmacophores [7].

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software for Pharmacophore Modeling with LigandScout

| Item / Resource | Function / Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| LigandScout Software | Primary platform for creating, visualizing, and optimizing SB/LB pharmacophore models, and performing virtual screens [20] [28]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of 3D structural data for proteins and protein-ligand complexes, essential for structure-based pharmacophore modeling [29]. |

| Compound Databases | Commercial or in-house libraries of small molecules for virtual screening (e.g., SPECS database used in the case study) [7]. |

| i-cluster Tool | Integrated tool within LigandScout for clustering active training compounds to generate representative LB-pharmacophores [29]. |

| ICON Algorithm | The conformational analysis engine within LigandScout used to generate bioactive conformations of ligands for LB modeling [29]. |

| LigandScout Remote | Interface module for transparently accessing HPC or cloud resources to accelerate computationally intensive virtual screens [25] [26]. |

| Active/Inactive Compound Sets | Curated sets of known molecules with defined activity against the target; crucial for both model training and validation [7] [29]. |

A Step-by-Step LigandScout Workflow: From Model Generation to Virtual Screening

The initial phase of constructing a robust ligand-based pharmacophore model is the meticulous preparation of a training set and the subsequent conformational analysis of its constituent molecules. This foundational step determines the model's ability to accurately capture the essential three-dimensional chemical features required for biological activity. The training set comprises known active compounds against the target of interest, and the quality of their selection directly influences the pharmacophore hypothesis generated. Following selection, conformational analysis explores the flexible space of each molecule to ensure that bioactive conformations are represented, enabling the identification of common features across structurally diverse ligands. This protocol details the best practices for executing these critical first steps within the context of a comprehensive ligand-based pharmacophore modeling workflow, leveraging the capabilities of the LigandScout software platform.

Training Set Preparation

Criteria for Training Set Selection

The selection of an appropriate training set is paramount for developing a predictive pharmacophore model. The compounds should be chosen based on several key criteria to ensure the model captures a wide yet relevant chemical space.

- Structural Diversity: The training set should encompass a broad range of core scaffolds or chemotypes. This diversity ensures the resulting model identifies fundamental interaction features critical for binding, rather than features specific to a single chemical class. For instance, a study on TGR5 agonists explicitly selected nine representative agonists with diverse scaffolds to form the training set for common feature pharmacophore generation [30].

- Potency: Compounds should ideally exhibit a range of high to moderate activity (e.g., IC50 or Ki values) to aid in the development of quantitative models or to prioritize features from highly active compounds. In practice, many studies curate training sets from compounds with proven, potent activity. For example, a model for carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors was built using seven chemically active compounds with IC50 values of less than 50 nM [31].

- Consistent Bioassay Data: All selected compounds should have been evaluated in the same or highly comparable biological assays to ensure consistency in the activity data [30].

The size of the training set can vary but typically ranges from a handful to several dozen compounds. A model for topoisomerase I inhibitors used 29 CPT derivatives as a training set [32], whereas a model for 17β-HSD2 inhibitors was built using common features from only two training compounds that were selected for their structural diversity and potency [7].

Data Curation and Preparation

Before model generation, the 2D structures of the training set compounds must be curated and prepared.

- Structure Representation: Collect and draw the 2D structures of all selected compounds in a molecular editing environment.

- Standardization: Standardize the structures by adjusting protonation states to a relevant physiological pH (e.g., 7.4), removing counterions, and adding explicit hydrogens.

- Energy Minimization: Perform a preliminary energy minimization on the 2D structures using a suitable force field (e.g., MMFF94) to correct any unrealistic bond lengths or angles. This step produces clean, consistent 3D structures as a starting point for subsequent conformational analysis.

Table 1.1: Summary of Training Set Selection from Various Studies

| Target Protein | Training Set Size | Key Selection Criteria | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topoisomerase I | 29 compounds | Diverse derivatives of Camptothecin | [32] |

| hCA IX | 7 compounds | Potent inhibitors with IC50 < 50 nM | [31] |

| TGR5 | 9 compounds | Diverse scaffolds and high potency | [30] |

| 17β-HSD2 | 2 compounds | Structural diversity and high potency | [7] |

| FAK1 | 20 antagonists | Known active compounds from ChEMBL | [33] |

Conformational Analysis

The goal of conformational analysis is to generate a representative ensemble of low-energy 3D conformations for each molecule in the training set. This is critical because the pharmacophore model is derived from the 3D orientation of chemical features, and the bioactive conformation of a flexible ligand is often unknown.

Protocol for Conformational Generation

The following protocol can be applied within LigandScout or other molecular modeling suites to perform a comprehensive conformational analysis.

- Input Prepared Structures: Import the curated and energy-minimized 3D structures of the training set compounds into the software.

- Set Conformational Generation Parameters:

- Method: Use the "best conformer generation" method or a similar stochastic search algorithm [30].

- Energy Threshold: Set an energy threshold above the global minimum, typically 10 kcal/mol, to include relevant low-energy conformations while excluding high-energy, unrealistic ones [30] [34].

- Maximum Conformations: Define an upper limit for the number of conformations generated per molecule to manage computational cost. A common setting is 200 conformations per compound [30]. For more complex, flexible molecules, this number may be increased.

- Execute Conformational Analysis: Run the conformational generation algorithm. The software will systematically explore rotatable bonds and generate a set of conformers that fall within the specified energy window.

- Output: The result is a multi-conformer database for the entire training set, where each compound is represented by an ensemble of 3D structures.

This ensemble is the direct input for the common feature pharmacophore generation algorithm in the next step of the workflow. The algorithm will analyze these multiple conformations of multiple active compounds to find the best spatial arrangement of common chemical features.

Table 1.2: Key Parameters for Conformational Analysis

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generation Method | Best/Stochastic Search | Explores rotatable bonds to sample conformational space. | [30] |

| Energy Threshold | 10 kcal/mol | Filters out high-energy, unrealistic conformers. | [30] [34] |

| Maximum Conformations | 200 | Balances computational cost with conformational coverage. | [30] |

| Force Field | MMFF94 | Used for energy calculation and minimization during generation. | Implied in data preparation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1.3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Training Set Preparation and Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use in Protocol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) | Source of known active compounds and associated bioactivity data (IC50, Ki). | Curating a training set of potent, diverse inhibitors for a new target. | [33] |

| Molecular Editing Software (e.g., ChemDraw) | Creation, visualization, and 2D representation of chemical structures. | Drawing and initially cleaning the structures of selected training set compounds. | - |

| LigandScout Software | Integrated platform for structure and ligand-based drug design. | Performing conformational analysis and subsequent pharmacophore model generation. | [6] [33] |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides computational power for demanding conformational searches on large training sets. | Generating 200 conformers for each of 50 compounds in the training set. | - |

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram visualizes the sequential protocol for training set preparation and conformational analysis.

Within a comprehensive ligand-based pharmacophore modeling workflow, the generation of the pharmacophore model and the creation of a robust hypothesis represent a critical inflection point. This step transforms structural data of known active compounds into an abstract, three-dimensional query that encapsulates the essential steric and electronic features required for biological activity. Using LigandScout software, this process leverages advanced algorithms to detect common chemical features from a set of pre-aligned ligands, creating a model that can discriminate between active and inactive compounds for virtual screening campaigns [29] [35]. The precision of this phase directly influences the success of subsequent virtual screening and lead optimization efforts.

Theoretical Foundation

A pharmacophore is formally defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [35]. In practical terms, it represents the key molecular interactions a ligand must form with its target, divorced from the underlying chemical scaffold.

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling operates on the principle that compounds sharing similar biological activities will interact with the target through a common set of molecular features. The modeling process in LigandScout identifies these conserved features—including hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic regions (H), and aromatic rings (AR)—and their precise three-dimensional arrangement [36] [35]. This approach is particularly valuable when the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable, as it relies solely on the structural and chemical properties of known active ligands.

Experimental Protocol

Preparation of Training and Test Sets

The initial phase requires careful curation of compound data to ensure model reliability:

- Data Collection and Curation: Gather structures of known active compounds, ideally with associated IC₅₀ or Ki values. Inactive compounds should also be collected to assess model selectivity [34]. For the 17β-HSD2 inhibitor study, researchers categorized compounds as active or inactive based on specific IC₅₀ thresholds [7].

- Training/Test Set Division: Split the data so that 75% of active compounds and 75% of inactive compounds form the training set. The remaining 25% of each category is reserved as an independent test set for model validation [29].

- Conformational Sampling: Generate multiple 3D conformers for each compound using LigandScout's ICON algorithm to explore conformational space and represent potential bioactive conformations [29]. The maximum number of conformations can be adjusted based on ligand flexibility.

Ligand Clustering and Alignment

- Cluster Analysis: Use LigandScout's i-cluster tool with default parameters (cluster distance = 0.4 with average method) to group training set actives based on structural similarity [29]. This ensures diverse chemical scaffolds are represented in model generation.

- Molecular Alignment: LigandScout employs flexible alignment algorithms to superimpose compounds from the same cluster, identifying the optimal spatial overlap of key functional groups [36].

Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation

- Feature Identification: For each cluster, LigandScout automatically identifies and maps common pharmacophoric features across the aligned conformations [29] [35]. The algorithm ranks molecular alignments using multiple scoring functions and creates intermediate pharmacophores for each compound.

- Model Building: The software processes molecules iteratively, aligning common features to all conformations of subsequent molecules until all compounds in the cluster are processed, resulting in a final pharmacophore hypothesis [29].

Model Optimization and Validation

- Iterative Refinement: Screen the generated pharmacophore against the training set with "Max. number of omitted features" set to 0. If the positive predictive value (PPV) is high but recall is low, perform additional screenings with the parameter set to 1 to identify non-essential features that can be set as optional [29].

- Feature Adjustment: Manually review and adjust feature tolerances, exclusion volumes, and optional features based on screening performance. The goal is to retain only features critical for biological activity while maximizing the retrieval of active compounds [7] [29].

- Validation: Assess model performance using the independent test set. Calculate statistical metrics including sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1 score to quantify predictive power [36]. For the 17β-HSD2 inhibitors, researchers achieved high sensitivity (0.87) while retrieving no inactive compounds from the test set [7].

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for pharmacophore generation and hypothesis creation in LigandScout:

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 1: Common Pharmacophore Features in LigandScout and Their Chemical Significance

| Feature Type | Chemical Group | Role in Molecular Recognition | Geometric Tolerance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Carbonyl oxygen, Nitro groups, Sulfoxide | Forms hydrogen bonds with donor groups on protein | 1.0 - 1.5 |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Amine groups, Hydroxyl groups, Amides | Forms hydrogen bonds with acceptor groups on protein | 1.0 - 1.5 |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Alkyl chains, Aromatic rings, Steroid skeletons | Participates in van der Waals interactions with hydrophobic protein pockets | 1.2 - 1.8 |

| Aromatic Ring (AR) | Phenyl, Pyridine, Other heterocyclic rings | Enables π-π stacking and cation-π interactions | 1.5 - 2.0 |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Carboxylic acids, Tetrazoles, Phosphates | Forms salt bridges with positively charged residues | 1.5 - 2.0 |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Primary amines, Guanidines, Amidines | Forms salt bridges with negatively charged residues | 1.5 - 2.0 |

Table 2: Performance Metrics from Validated Pharmacophore Models in Published Studies

| Study Target | Sensitivity | Specificity | Enrichment Factor | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17β-HSD2 Inhibitors [7] | 0.87 | 1.00 | >20 | PMC4111740 |

| EGFR Inhibitors [6] | 0.75 | 0.82 | 15.3 | IJMS21207779 |

| A2a Antagonists [34] | 0.81 | 0.79 | 12.7 | MOLECULES23123094 |

| CYP450 3A4 Inhibitors [34] | 0.76 | 0.85 | 14.2 | MOLECULES23123094 |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Function in Workflow | Implementation in LigandScout |

|---|---|---|

| Active Compound Set | Provides structural basis for feature identification | Curated from databases (ChEMBL, PubChem) with activity data [34] |

| Inactive Compound Set | Enables specificity assessment and model validation | Collected from same sources as actives but with no measurable activity [29] |

| ICON Algorithm | Generates representative 3D conformations | Default conformer generator in LigandScout [29] |

| i-cluster Tool | Groups compounds by structural similarity | Implements hierarchical clustering with adjustable distance metrics [29] |

| Pharmacophore Feature Definitions | Standardizes chemical feature recognition | Based on SMARTS patterns and molecular interaction capabilities [34] |

| Exclusion Volumes | Represents steric constraints of binding site | Automatically generated from protein structure or manually added [7] |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Addressing Common Challenges

Handling Conformational Flexibility: When dealing with flexible ligands, increase the maximum number of conformations generated during the conformational analysis stage. This ensures adequate sampling of the conformational space and increases the probability of identifying the bioactive conformation [29] [36].

Balancing Specificity and Sensitivity: If the model retrieves too many false positives (low specificity), increase feature constraints and reduce optional features. Conversely, if the model misses known actives (low sensitivity), consider setting less critical features as optional or increasing distance tolerances [7] [36].

Managing Structural Diversity: When working with structurally diverse ligands that may bind through different interaction patterns, generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses—one for each distinct cluster of compounds [29]. This multi-model approach can capture complementary aspects of ligand-target interactions.

Advanced Optimization Techniques

Feature Weighting: Assign higher weights to features that consistently appear across active compounds but are absent in inactives. This enhances model discrimination power during virtual screening [7].

Exclusion Volume Placement: Strategically place exclusion volume spheres to represent protein atoms that would cause steric clashes, improving the model's ability to reject false positives [7]. In the 17β-HSD2 study, models incorporated 54-56 exclusion volumes to define binding site boundaries [7].

Multi-Conformer Models: For highly flexible binding sites, consider developing multiple pharmacophore models representing different receptor conformations to account for protein flexibility and induced-fit effects [36].

Core Components of a Pharmacophore Model

A pharmacophore model is an abstract representation of the steric and electronic features essential for a molecule to interact with a biological target and trigger or block its biological response [37]. In ligand-based modeling, this 3D arrangement is derived from the common chemical features shared by a set of known active molecules [7] [37]. Interpreting these models correctly is crucial for their successful application in virtual screening and drug design. The primary components can be categorized into three main groups: chemical features, spatial constraints, and exclusion volumes.

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Functional Significance

| Feature Type | Chemical Groups Represented | Role in Molecular Recognition |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Carbonyl oxygen, nitrogen in aromatics, ether oxygen [37] | Forms hydrogen bonds with donor groups on the protein target (e.g., backbone NH) [8] [37] |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Amine group, hydroxyl group, amide NH [37] | Forms hydrogen bonds with acceptor groups on the protein target (e.g., backbone C=O) [8] [37] |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Alkyl chains, aliphatic or aromatic rings [37] | Engages in van der Waals interactions with hydrophobic pockets on the protein surface [7] [37] |

| Aromatic Ring (AR) | Phenyl, pyridine, other aromatic systems [8] | Facilitates π-π stacking or cation-π interactions with protein residues [7] |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Carboxylic acid, tetrazole, sulfonamide [16] | Participates in ionic or charged interactions with positively charged residues (e.g., Lys, Arg) [16] |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Primary amine, guanidine, pyridine [38] | Participates in ionic or charged interactions with negatively charged residues (e.g., Asp, Glu) [38] |

Spatial constraints are defined by the location and tolerances (radii) of the pharmacophore features in three-dimensional space [7]. A compound is considered a "hit" only if it can adopt a conformation that positions its corresponding chemical functionalities within the allowed tolerance radii of all essential model features [38].

Exclusion volumes (XVols) are steric constraints that represent regions in space occupied by the protein's binding pocket wallscitation:6]. Any molecule that maps the chemical features but has atoms that sterically clash with these defined volumes is predicted to be inactive, as it would experience unfavorable van der Waals repulsionscitation:1] [37].

Experimental Protocol for Model Interpretation and Validation

This protocol details the steps for interpreting a generated ligand-based pharmacophore model, assessing its quality, and preparing it for virtual screening using LigandScout and related tools.

Visual Inspection and Feature Analysis

Objective: To qualitatively verify the chemical logic and spatial arrangement of the pharmacophore model. Procedure:

- Load the Model: Open the generated pharmacophore model (e.g., a shared features pharmacophore, SFP) in LigandScout [16].

- Align with Training Set: Superimpose the model with the aligned conformers of the training set compounds used to generate it [37]. Visually confirm that the model's features correspond to the common functional groups present in the training molecules.

- Analyze Feature-Function Relationship: For each feature, identify its potential role in target binding. For instance, in a model for fluoroquinolone antibiotics, the presence of HBAs and HBDs is critical for interacting with the DNA gyrase enzyme [8].

- Review Exclusion Volumes: Examine the placement of exclusion volumes. These should logically represent the boundaries of the binding pocket as inferred from the training ligands [37].

Theoretical Validation using a Test Set

Objective: To quantitatively assess the model's ability to distinguish known active compounds from inactive ones [37]. Procedure:

- Curate a Test Set: Compile a dataset containing:

- Actives: A set of known active compounds not used in the training set. These should be experimentally confirmed (e.g., via enzyme activity assays) and structurally diverse [37].

- Inactives/Decoys: A larger set of confirmed inactive compounds or computer-generated decoys with similar 1D properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP) but different 2D topologies [37]. Tools like the Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced (DUD-E) can be used for this purpose [37]. A recommended active-to-decoy ratio is 1:50 [37].

- Perform Virtual Screening: Screen the test set against the pharmacophore model in LigandScout.

- Calculate Quality Metrics: Analyze the hit list to compute standard validation metrics [37]:

- Sensitivity: The proportion of known active compounds correctly retrieved by the model.

- Specificity: The proportion of inactive compounds correctly excluded by the model.

- Enrichment Factor (EF): The enrichment of active molecules in the hit list compared to a random selection.

- Goodness of Hit (GH) Score: A composite metric that balances the recall of actives and the rejection of inactives. A GH score of 0.7-1.0 is generally considered excellent [16].

- Area Under the Curve of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC-AUC): A measure of the overall classification performance.

Table 2: Key Quality Metrics for Pharmacophore Model Validation

| Metric | Formula/Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives) | Ability to identify active molecules. Closer to 1 (or 100%) is better [7]. |

| Specificity | True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives) | Ability to exclude inactive molecules. Closer to 1 (or 100%) is better [7]. |

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | (Hitssactive / Ntotal) / (Nactive / Ntotal) | Measures how much the model enriches actives in the hit list versus random screening. Higher is better [37]. |

| Goodness of Hit (GH) | Combines recall of actives and the false positive rate into a single score (0 to 1). | A score above 0.7 indicates a high-quality model with strong predictive power [16]. |

Model Refinement and Optimization

Objective: To improve model performance based on validation results. Procedure:

- Analyze False Positives/Negatives: Examine compounds that were incorrectly classified. If false positives (inactives that are hits) share certain features, consider adding an exclusion volume in that region or making an overrepresented feature optional [7].

- Adjust Feature Definitions: Modify the tolerance radii of features or redefine the specific chemical groups they represent to better reflect the structure-activity relationships (SAR) of the training set [37].

- Set Features as Optional: If a feature is not present in all highly active training compounds, it can be set as "optional." The model will then match compounds that map either all mandatory features or all mandatories plus a user-defined number of the optional ones [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Databases for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Model Interpretation/Validation |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [37] [16] | Software | Primary tool for advanced pharmacophore model generation, visualization, and screening. Used for creating shared-feature models and performing virtual screening [16]. |