Ligand-Based Drug Design in Oncology: AI-Driven Approaches, Applications, and Future Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern ligand-based drug design (LBDD) and its critical role in oncology drug discovery.

Ligand-Based Drug Design in Oncology: AI-Driven Approaches, Applications, and Future Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern ligand-based drug design (LBDD) and its critical role in oncology drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of LBDD, detailing key methodologies like Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, pharmacophore modeling, and AI-enhanced virtual screening. The content addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, offers insights into validating LBDD models, and compares its effectiveness with structure-based approaches. By synthesizing current trends and real-world case studies, this article serves as a practical guide for leveraging LBDD to accelerate the development of novel cancer therapeutics.

The Principles and Power of Ligand-Based Design in Oncology

In the relentless pursuit of effective oncology therapeutics, ligand-based drug design (LBDD) stands as a cornerstone methodology for initiating discovery when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unavailable or incomplete. This approach facilitates the development of pharmacologically active compounds by systematically studying the chemical and structural features of molecules known to interact with a biological target of interest [1]. Within oncology, this is particularly valuable for targeting novel oncogenic drivers or resistant cancer phenotypes where structural data may be scarce. The fundamental hypothesis underpinning LBDD is that similar molecules exhibit similar biological activities; therefore, understanding the essential features of a known active compound enables the rational design or identification of novel chemical entities with comparable or improved therapeutic properties [1]. This paradigm allows researchers to navigate the vast chemical space efficiently, focusing on regions more likely to yield bioactive compounds against cancer targets.

The strategic importance of LBDD has been magnified by contemporary challenges in oncology research, including the need to overcome drug resistance and the pursuit of targeting previously "undruggable" oncoproteins. Modern LBDD has evolved from simple analog generation to sophisticated computational approaches that can extract critical pharmacophoric patterns and quantify structure-activity relationships from increasingly complex chemical datasets [2]. As the field of anticancer agents has expanded to include targeted therapies, immunomodulators, and protein degraders, LBDD methodologies have adapted to address diverse mechanism-of-action categories, from traditional cytotoxic agents to modern modalities like PROTACs and molecular glues [2]. The integration of artificial intelligence with classical LBDD principles is now reshaping the oncology drug discovery landscape, enabling the extraction of deeper insights from known active compounds and accelerating the path to novel clinical candidates [3].

Foundational Methodologies and Current Approaches

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR represents one of the most established and powerful methodologies in ligand-based drug design. This computational approach quantitatively correlates the physicochemical properties and structural descriptors of a series of compounds with their biological activity, creating a predictive model that can guide lead optimization [1]. The general QSAR methodology follows a systematic workflow: (1) identification of ligands with experimentally measured biological activity; (2) calculation of molecular descriptors representing structural and physicochemical properties; (3) discovery of correlations between these descriptors and the biological activity; and (4) statistical validation of the model's stability and predictive power [1]. The molecular descriptors function as a chemical "fingerprint" for each molecule, encoding features critical for biological activity, which may include electronic, steric, hydrophobic, or topological characteristics.

Advanced QSAR implementations have incorporated increasingly sophisticated statistical and machine learning techniques to handle complex biological data. Traditional linear methods include multivariable linear regression (MLR), principal component analysis (PCA), and partial least squares (PLS) analysis [1]. For capturing non-linear relationships often present in biological systems, neural networks and Bayesian regularized artificial neural networks (BRANN) have demonstrated significant utility [1]. A critical aspect of robust QSAR modeling is rigorous validation through both internal methods (e.g., leave-one-out cross-validation) and external validation using test sets not included in model development [1]. When properly validated, QSAR models provide medicinal chemists with actionable insights into which structural modifications are most likely to enhance potency, selectivity, or other desirable pharmacological properties for anticancer agents.

Pharmacophore Modeling and Molecular Similarity

Pharmacophore modeling embodies the essential concept of identifying the spatial arrangement of molecular features necessary for a compound to interact with its biological target. A pharmacophore model abstractly represents these critical features—such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, and charged groups—without explicit reference to specific chemical structures [1] [4]. This abstraction enables the identification of structurally diverse compounds that share the fundamental elements required for bioactivity, effectively facilitating scaffold hopping in drug discovery. Pharmacophore models can be derived either directly from a set of known active ligands (ligand-based) or from protein-ligand complex structures when available (structure-based) [5].

In practice, pharmacophore models serve as powerful 3D queries for virtual screening of compound databases. A recent study targeting telomerase inhibitors for cancer therapy demonstrated this approach, where researchers generated a pharmacophore model from oxadiazole derivatives that exhibited five distinct features: two hydrophobic and three aromatic rings [4]. This model was subsequently used to screen the ZINC database, identifying compounds with similar pharmacophore features and good fitness scores for further investigation through molecular docking and dynamics simulations [4]. Complementing pharmacophore approaches, molecular similarity methods utilize various molecular descriptors and fingerprinting techniques to calculate chemical similarity, operating under the similar property principle that structurally similar molecules are likely to have similar biological properties [5]. These ligand-based methods have proven particularly valuable in the early stages of oncology drug discovery for identifying novel starting points from extensive chemical libraries.

Table 1: Key Ligand-Based Drug Design Methods and Applications

| Method | Core Principle | Common Applications in Oncology | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR | Quantifies relationship between molecular descriptors and biological activity | Lead optimization for potency, ADMET prediction, toxicity assessment | Provides quantitative guidance for structural modification |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Identifies essential 3D structural features required for bioactivity | Virtual screening for novel chemotypes, scaffold hopping, target identification | Enables identification of structurally diverse active compounds |

| Molecular Similarity | Calculates structural or property similarity to known actives | Compound library screening, lead expansion, side effect prediction | Rapid screening of large chemical libraries |

| Machine Learning Classification | Uses algorithms to distinguish active vs. inactive compounds | High-throughput virtual screening, multi-parameter optimization | Can handle complex, high-dimensional data |

Integrating Machine Learning and AI in Modern Workflows

The incorporation of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) has fundamentally transformed ligand-based drug design from a primarily heuristic approach to a data-driven predictive science. ML algorithms can identify complex, non-linear patterns in chemical data that may not be apparent through traditional methods, enabling more accurate prediction of biological activity and optimization of multiple drug-like properties simultaneously [6] [3]. In contemporary workflows, supervised ML approaches are frequently employed to distinguish between active and inactive molecules based on their chemical descriptor profiles, significantly accelerating the virtual screening process [6]. For instance, in a study aimed at identifying natural inhibitors of the αβIII tubulin isotype for cancer therapy, researchers used ML classifiers to refine 1,000 initial virtual screening hits down to 20 high-priority active natural compounds, dramatically improving the efficiency of the discovery pipeline [6].

The application of deep generative models represents a particularly advanced frontier in AI-driven ligand-based design. These models learn the underlying distribution of known bioactive compounds and can generate novel molecular structures that conform to the same chemical and pharmacological patterns [7]. Language-based models such as REINVENT process molecular representations (e.g., SMILES strings) and use reinforcement learning to optimize generated molecules toward desired property profiles defined by scoring functions [7]. While traditionally dependent on ligand-based scoring functions, which can bias generation toward previously established chemical space, recent innovations incorporate structure-based approaches like molecular docking to guide exploration toward novel chemotypes with potentially superior properties [7]. This integration of ligand-based generative AI with structural considerations exemplifies the evolving sophistication of computational oncology drug discovery, enabling the navigation of chemical space with unprecedented efficiency and creativity.

Experimental Protocols and Practical Implementation

Protocol 1: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

Objective: To identify novel telomerase inhibitors for cancer therapy using ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening [4].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Training Set Compilation: Curate a structurally diverse set of known active compounds (e.g., oxadiazole derivatives with reported telomerase inhibitory activity) from scientific literature.

- Pharmacophore Model Generation: Use molecular modeling software (e.g., Schrödinger Phase) to generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses based on the conformational and feature analysis of the training set compounds.

- Model Validation & Selection: Validate generated hypotheses by screening against a test dataset of known actives and decoys. Select the model with best enrichment (e.g., a five-feature model with two hydrophobic and three aromatic rings) [4].

- Database Screening: Employ the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC) using tools like ZINCPharmer.

- Hit Identification & Filtering: Select molecules that match the pharmacophore features with high fitness scores for subsequent molecular docking studies.

- ADMET Prediction: Evaluate pharmacokinetics and toxicity profiles of top hits using tools like pkCSM and SwissADME to identify promising candidates with favorable properties [4].

- Experimental Validation: Subject the final selected hit compounds to in vitro and in vivo biological testing to confirm telomerase inhibitory activity and anticancer efficacy.

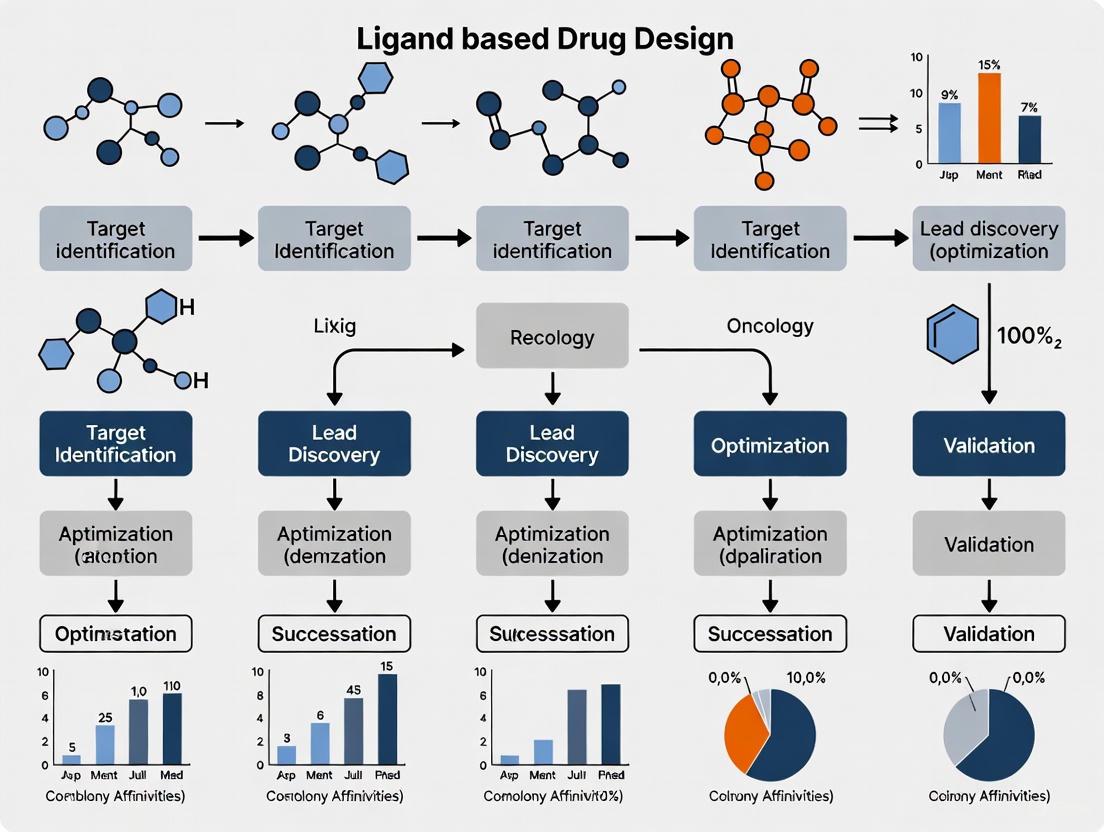

Diagram 1: Pharmacophore virtual screening workflow for novel telomerase inhibitors.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Enhanced Screening for Anti-Tubulin Agents

Objective: To identify natural inhibitors targeting the 'Taxol site' of human αβIII tubulin isotype using a combination of structure-based and ligand-based machine learning approaches [6].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Compound Library Preparation: Retrieve natural compounds (e.g., 89,399 from ZINC database) and prepare structures (energy minimization, format conversion to PDBQT).

- Initial Structure-Based Virtual Screening: Perform high-throughput molecular docking against the target site (e.g., 'Taxol site' of αβIII-tubulin) using software such as AutoDock Vina to generate initial hit list based on binding energy.

- Training Data Curation for ML: Prepare two training datasets: (1) known Taxol-site targeting drugs as active compounds, and (2) non-Taxol targeting drugs as inactive compounds. Generate decoys using Directory of Useful Decoys - Enhanced (DUD-E) server [6].

- Molecular Descriptor Calculation: Calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints for both training sets and virtual screening hits using software like PaDEL-Descriptor, which generates 797 descriptors and 10 fingerprint types [6].

- Machine Learning Classifier Training: Train supervised ML models (e.g., using 5-fold cross-validation) on the training data to distinguish active from inactive compounds based on their descriptor profiles.

- Hit Refinement with ML: Apply the trained ML classifier to the initial virtual screening hits to identify compounds with high probability of activity, substantially narrowing the candidate list (e.g., from 1,000 to 20 compounds) [6].

- Comprehensive Biological Property Evaluation: Subject ML-refined hits to ADME-T (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) and PASS (Prediction of Activity Spectra for Substances) analysis to evaluate drug-likeness and potential biological activities.

- Binding Confirmation and Stability Assessment: Perform molecular dynamics simulations (100+ ns) with analysis of RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and SASA to evaluate complex stability and binding modes of top candidates.

- Binding Affinity Quantification: Calculate binding free energies (e.g., using MM-PBSA) to rank final candidates by predicted binding affinity.

Diagram 2: Machine learning-enhanced screening workflow for anti-tubulin agents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ligand-Based Drug Design

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ZINC Natural Compound Database, CAS Content Collection | Source of compounds for virtual screening | Provides chemically diverse starting points for discovery [6] [8] |

| Molecular Modeling Software | Schrödinger Phase, Open-Babel, PyMol | Pharmacophore generation, structure preparation, visualization | Creates and applies 3D chemical feature models [6] [4] |

| Descriptor Calculation Tools | PaDEL-Descriptor, Chemistry Development Kit | Generates molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Converts chemical structures to numerical data for ML [6] |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Python Scikit-learn, REINVENT, Custom ML scripts | Builds classification models, generative molecule design | Distinguishes actives from inactives, generates novel structures [6] [7] |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, Glide, Smina | Structure-based virtual screening, binding pose prediction | Evaluates protein-ligand complementarity and binding affinity [6] [7] |

| Molecular Dynamics Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, Desmond | Simulates dynamic behavior of protein-ligand complexes | Assesses binding stability and calculates free energies [6] [4] |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | pkCSM, SwissADME, PASS | Predicts pharmacokinetics, toxicity, activity spectra | Evaluates drug-likeness and safety profiles early in discovery [6] [4] |

Case Studies in Oncology Drug Discovery

Case Study 1: Overcoming Taxol Resistance in Cancer Therapy

A compelling application of integrated ligand- and structure-based approaches addressed the significant challenge of taxane resistance in various carcinomas, particularly associated with overexpression of the βIII-tubulin isotype [6]. Researchers initiated this discovery campaign by screening 89,399 natural compounds from the ZINC database against the 'Taxol site' of αβIII-tubulin using structure-based virtual screening, identifying 1,000 initial hits based on binding energy [6]. The critical innovation involved applying machine learning classifiers trained on known Taxol-site targeting drugs (actives) versus non-Taxol targeting drugs (inactives) to refine these hits to 20 high-priority compounds [6]. Subsequent ADME-T and PASS biological property evaluation identified four exceptional candidates—ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, ZINC08952607, and ZINC03847075—that exhibited both favorable drug-like properties and notable predicted anti-tubulin activity [6].

Comprehensive molecular dynamics simulations (assessed via RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and SASA analysis) revealed that these natural compounds significantly influenced the structural stability of the αβIII-tubulin heterodimer compared to the apo form [6]. Binding energy calculations further demonstrated a decreasing order of binding affinity: ZINC12889138 > ZINC08952577 > ZINC08952607 > ZINC03847075, providing quantitative support for compound prioritization [6]. This case exemplifies how modern ligand-based design, enhanced by machine learning, can leverage known active compounds (Taxol-site binders) to identify novel chemotypes capable of targeting resistant cancer phenotypes, offering a promising foundation for developing therapeutic strategies against βIII-tubulin overexpression in carcinomas.

Case Study 2: AI-Driven De Novo Design for Dopamine Receptor D2

A groundbreaking study compared ligand-based and structure-based scoring functions for deep generative models focused on Dopamine Receptor D2 (DRD2), a target relevant to certain cancer types [7]. Researchers utilized the REINVENT algorithm, which employs a language-based generative model with reinforcement learning to optimize molecule generation toward desired property profiles [7]. The study revealed that using molecular docking as a structure-based scoring function produced molecules with predicted affinities exceeding those of known DRD2 active compounds, while also exploring novel physicochemical space not biased by existing ligand data [7]. Importantly, the structure-based approach enabled the model to learn and incorporate key residue interactions critical for binding—information inaccessible to purely ligand-based methods [7].

This case demonstrates the powerful synergy that emerges when generative AI models are guided by structural insights, particularly for targets where ligand data may be limited or where novel chemotypes are desired to overcome intellectual property constraints or optimize drug-like properties. The approach has direct applications in early hit generation campaigns for oncology targets, enriching virtual libraries toward specific protein targets while maintaining exploration of novel chemical space [7]. This represents an evolution beyond traditional similarity-based methods, enabling the discovery of structurally distinct compounds that nonetheless fulfill the essential interaction requirements for target binding and modulation.

The future of ligand-based drug design in oncology is intrinsically linked to advancing artificial intelligence methodologies and their integration with complementary structural approaches. Current trends indicate a shift toward hybrid models that simultaneously leverage both ligand information and structural insights, overcoming limitations inherent in either approach used in isolation [5] [7]. As noted in recent research, "the combination of structure- and ligand-based methods takes into account all possible information" [5], with sequential approaches being particularly successful in prospective virtual screening campaigns. The emerging paradigm utilizes ligand-based methods for initial broad screening and structure-based techniques for deeper mechanistic investigation and optimization [5].

The remarkable acceleration of generative AI in de novo molecule design points toward increasingly sophisticated applications in oncology drug discovery [9] [3]. Recent developments include AI models like BInD (Bond and Interaction-generating Diffusion model) that can design drug candidates tailored to a protein's structure alone—without needing prior information about binding molecules [9]. This technology considers the binding mechanism between the molecule and protein during the generation process, enabling comprehensive design that simultaneously satisfies multiple drug criteria including target binding affinity, drug-like properties, and structural stability [9]. As these technologies mature, they promise to further compress the oncology drug discovery timeline while increasing the success rate of identifying viable clinical candidates.

In conclusion, leveraging known active compounds through sophisticated ligand-based design methodologies remains a powerful strategy for oncology drug discovery, particularly when enhanced by modern machine learning and structural insights. As these approaches continue to evolve and integrate, they offer the potential to systematically address ongoing challenges in cancer therapy, including drug resistance, toxicity, and the targeting of previously intractable oncogenic drivers. The strategic combination of ligand-based pattern recognition with structural validation represents the most promising path forward for discovering novel therapeutic agents in the relentless fight against cancer.

In the field of oncology research, where the precise three-dimensional structure of a therapeutic target is often unavailable, ligand-based drug design (LBDD) provides a powerful alternative path to drug discovery. LBDD methodologies rely on the analysis of known active molecules to deduce the structural and chemical features responsible for biological activity, enabling the identification and optimization of new drug candidates [10] [11]. The core principle underpinning these approaches is the similarity-property principle, which posits that molecules with similar structures are likely to exhibit similar biological properties and activities [10]. This principle is particularly valuable in cancer research for tasks such as scaffold hopping to circumvent patent restrictions or to improve the drug-like properties of existing leads.

Three primary methodologies constitute the foundation of LBDD: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR), pharmacophore modeling, and similarity searching. These techniques are not mutually exclusive; rather, they form an integrated toolkit that researchers can use to efficiently navigate the vast chemical space and prioritize the most promising compounds for synthesis and biological testing [10] [11]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these three core methodologies, detailing their theoretical bases, standard protocols, and applications within modern oncology drug discovery pipelines, with a special emphasis on recent advances driven by artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR)

Theoretical Foundations and Evolution

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling is a computational methodology that establishes a mathematical relationship between the chemical structure of compounds and their biological activity [10] [12]. The fundamental hypothesis is that the variance in biological activity among a series of compounds can be correlated with changes in their numerical descriptors representing structural or physicochemical properties [12]. A QSAR model takes the general form: Activity = f(physicochemical properties and/or structural properties) + error [12].

The roots of QSAR date back to the 19th century with observations by Meyer and Overton, but it formally began in the early 1960s with the seminal work of Hansch and Fujita, who extended Hammett's equation to include physicochemical properties [10]. The classical Hansch equation is: log(1/C) = b₀ + b₁σ + b₂logP, where C is the concentration required for a defined biological effect, σ represents electronic properties (Hammett constant), and logP represents lipophilicity [10]. This established the paradigm of using multiple descriptors to predict activity, a concept that has evolved dramatically with the advent of modern machine learning techniques.

Essential Steps in QSAR Modeling

The construction of a robust QSAR model follows a systematic workflow comprising several critical stages [12]:

- Data Set Selection and Preprocessing: A congeneric series of compounds with reliable, consistently measured biological activity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) is assembled. The activity values are typically converted to a logarithmic scale (e.g., pIC₅₀, pKi) to normalize the distribution.

- Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Extraction: Numerical representations of molecular structures are computed. These can be 1D (e.g., molecular weight), 2D (e.g., topological indices), 3D (e.g., molecular shape), or even 4D descriptors that account for conformational flexibility [13]. Quantum chemical descriptors (e.g., HOMO-LUMO energy) are also used [13].

- Variable Selection: To avoid overfitting, dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), or Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) are employed to identify the most relevant descriptors [10] [13].

- Model Construction: A statistical or machine learning algorithm is applied to correlate the selected descriptors with the biological activity.

- Model Validation and Evaluation: The model's predictive power and robustness are rigorously assessed using internal cross-validation, external validation with a test set, and data randomization (Y-scrambling) to rule out chance correlations [12].

Table 1: Common Molecular Descriptors in QSAR Modeling

| Descriptor Category | Description | Example Descriptors | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D Descriptors | Global molecular properties | Molecular Weight, logP, Number of H-Bond Donors/Acceptors | Preliminary screening, ADMET prediction |

| 2D Descriptors | Topological descriptors from molecular connectivity | Molecular Connectivity Indices, Graph-Theoretic Indices | Large-scale virtual screening |

| 3D Descriptors | Based on 3D molecular structure | Molecular Surface Area, Volume, Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) | Lead optimization, understanding steric/electrostatic requirements |

| 4D Descriptors | Incorporate conformational flexibility | Ensemble-averaged properties | Improved realism for flexible ligands |

| Quantum Chemical | Electronic structure properties | HOMO/LUMO energies, Dipole Moment, Partial Charges | Modeling electronic effects on activity |

Classical and Machine Learning Approaches

QSAR modeling has evolved from classical statistical methods to advanced machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms.

Classical QSAR relies on methods like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Partial Least Squares (PLS). These models are valued for their interpretability and are still used in regulatory toxicology (e.g., REACH compliance) and for preliminary screening [13]. However, they often struggle with highly nonlinear relationships in complex data [13].

Machine Learning in QSAR has significantly enhanced predictive power. Standard algorithms include:

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Effective in high-dimensional descriptor spaces.

- Random Forests (RF): Robust against overfitting and provide built-in feature importance ranking.

- k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN): A simple, instance-based learning method [13].

Modern developments focus on improving interpretability using methods like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to elucidate which molecular descriptors most influence the model's predictions [13].

Deep Learning QSAR utilizes architectures such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) that operate directly on molecular graphs, or Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) that process SMILES strings, to automatically learn relevant feature representations without manual descriptor engineering [13] [14]. This is particularly powerful for large and diverse chemical datasets.

The following diagram illustrates the standard QSAR workflow, integrating both classical and ML approaches:

Pharmacophore Modeling

Definition and Core Concepts

A pharmacophore is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [11]. In simpler terms, it is an abstract model of the key functional elements of a ligand and their specific spatial arrangement that enables bioactivity. The most common pharmacophoric features include [11]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA)

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD)

- Hydrophobic (H)

- Positively/Negatively Ionizable (PI/NI)

- Aromatic Ring (AR)

Pharmacophore modeling is a powerful tool for scaffold hopping, as it focuses on interaction capabilities rather than specific atomic structures, allowing for the identification of chemically diverse compounds that share the same biological mechanism [15] [16].

Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Approaches

Pharmacophore models are generated using one of two primary approaches, depending on the available input data.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling This approach requires the 3D structure of the target protein, often from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or computational predictions (e.g., AlphaFold2) [11]. The workflow involves:

- Protein Preparation: Adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and optimizing the structure.

- Binding Site Detection: Identifying the key ligand-binding pocket using tools like GRID or LUDI [11].

- Feature Generation: Analyzing the binding site to map potential interaction points (e.g., where a H-bond donor on a ligand would interact with a H-bond acceptor on the protein).

- Model Refinement: Selecting the most critical features for bioactivity and potentially adding exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints [11].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling When the 3D structure of the target is unknown, models can be built from a set of known active ligands. The process involves:

- Ligand Selection and Conformational Analysis: Selecting a diverse set of active molecules and generating their low-energy 3D conformers.

- Molecular Alignment/Superimposition: Overlaying the molecules to find their common pharmacophoric elements.

- Hypothesis Generation: Deriving a pharmacophore model that represents the common spatial arrangement of features shared by all active ligands.

- Model Validation: Testing the model's ability to discriminate between known active and inactive compounds.

Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPHAR)

An advanced extension is Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPHAR), which builds quantitative models using pharmacophores as input rather than molecules [16]. This method aligns input pharmacophores to a consensus (merged) pharmacophore and uses the alignment information to construct a predictive model. QPHAR is especially useful with small datasets, as the high level of abstraction helps avoid bias from overrepresented functional groups, thereby improving model generalizability [16].

Applications and Case Study: TransPharmer

Pharmacophore models are extensively used in virtual screening to filter large compound libraries and identify novel hits [11]. They also play critical roles in lead optimization, multitarget drug design, and de novo drug design.

A state-of-the-art application is TransPharmer, a generative model that integrates ligand-based interpretable pharmacophore fingerprints with a Generative Pre-training Transformer (GPT) framework for de novo molecule generation [15]. TransPharmer conditions the generation of SMILES strings on multi-scale pharmacophore fingerprints, guiding the model to focus on pharmaceutically relevant features. It has demonstrated superior performance in generating molecules with high pharmacophoric similarity to a target and has been experimentally validated in a prospective case study for discovering Polo-like Kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibitors [15]. Notably, one generated compound, IIP0943, featuring a novel 4-(benzo[b]thiophen-7-yloxy)pyrimidine scaffold, exhibited potent activity (5.1 nM), high selectivity, and submicromolar activity in inhibiting HCT116 cell proliferation [15]. This showcases the power of pharmacophore-informed generative models to achieve scaffold hopping and produce structurally novel, bioactive ligands in oncology.

The logical flow of pharmacophore modeling and its applications is summarized below:

Similarity Searching

Principles and Molecular Representations

Similarity searching is a foundational LBDD method based on the similarity-property principle: molecules that are structurally similar are likely to have similar biological properties [10]. The core task is to quantify molecular similarity, which is typically achieved by comparing molecular representations or fingerprints. Common fingerprint types include:

- Structural Key Fingerprints: Predefined lists of substructures (e.g., MACCS keys).

- Hashed Fingerprints: Bit strings generated from the presence of molecular paths (e.g., Extended Connectivity Fingerprints - ECFP).

- Pharmacophore Fingerprints: Encode the spatial relationships between pharmacophoric features [15] [10].

Similarity is quantified using metrics such as the Tanimoto coefficient, which is the most widely used measure for binary fingerprints.

Application in Oncology Research

In an oncology drug discovery pipeline, similarity searching is typically employed after one or more lead compounds have been identified. Researchers use the lead compound as a query to search large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL) to find structurally similar molecules [10] [6]. This approach serves several purposes:

- To find readily available analogs for initial SAR exploration.

- To prioritize compounds from an in-house library for high-throughput screening.

- To expand a congeneric series around a newly discovered hit.

A key advantage is its simplicity and computational efficiency, allowing for the rapid screening of millions of compounds.

Integrated Protocols and Research Toolkit

Representative Experimental Protocol

The following is a condensed protocol illustrating how these LBDD methods can be integrated into a unified workflow for identifying inhibitors against a cancer target, such as the human αβIII tubulin isotype [6].

Aim: To identify natural inhibitors of the 'Taxol site' of the human αβIII tubulin isotype using an integrated computational approach.

Methodology:

- Data Set Curation:

- Active Compounds: Collect known Taxol-site targeting drugs (e.g., from ChEMBL or literature) to form the active set.

- Inactive Compounds/Decoys: Generate decoy molecules with similar physicochemical properties but dissimilar topologies using the Directory of Useful Decoys - Enhanced (DUD-E) server [6].

- Screening Library: Retrieve natural compounds from the ZINC database (~90,000 compounds) for virtual screening [6].

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS):

- Prepare the 3D structure of the αβIII tubulin isotype (e.g., via homology modeling).

- Define the binding site around the 'Taxol site'.

- Perform high-throughput molecular docking (e.g., using AutoDock Vina) of the screening library.

- Select the top 1,000 hits based on binding energy for further analysis [6].

Machine Learning-Based Classification:

- Calculate molecular descriptors (e.g., using PaDEL-Descriptor) for the training set (active/inactive compounds) and the test set (top 1,000 hits from SBVS).

- Train a supervised ML classifier (e.g., Random Forest) on the training set to distinguish between active and inactive molecules.

- Apply the trained model to the test set to identify ML-predicted active compounds. This step refined the 1,000 hits down to 20 high-confidence candidates [6].

ADMET and Biological Property Prediction:

- Evaluate the 20 shortlisted compounds for drug-like properties using ADMET prediction tools.

- Predict biological activity spectra (e.g., using PASS prediction).

- Select the top 4 compounds (ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, ZINC08952607, ZINC03847075) based on favorable ADMET profiles and predicted activity [6].

Validation with Molecular Dynamics (MD):

- Perform molecular docking and MD simulations (e.g., for 100 ns) on the final hits to assess the stability of the ligand-protein complexes and calculate binding free energies using methods like MM/PBSA [6].

Conclusion: The study identified four natural compounds with significant binding affinity and structural stability for the αβIII tubulin isotype, demonstrating a viable pipeline for discovering anti-cancer agents against a resistant target [6].

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Databases for LBDD in Oncology

| Category | Resource Name | Description and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ZINC Database | A freely available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening [6]. |

| ChEMBL | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, containing bioactivity data [16]. | |

| Descriptor Calculation & Feature Selection | PaDEL-Descriptor | Software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures [6]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit with capabilities for descriptor calculation, fingerprinting, and QSAR modeling [13]. | |

| DRAGON | A commercial software for the calculation of thousands of molecular descriptors [13]. | |

| QSAR & Machine Learning | scikit-learn | An open-source Python library providing a wide range of classical ML algorithms (SVM, RF, etc.) for model building [13]. |

| KNIME | An open-source platform for data analytics that integrates various cheminformatics and ML nodes for building predictive workflows [13]. | |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | LigandScout | Software for creating structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models and performing virtual screening [16]. |

| Phase (Schrödinger) | A comprehensive tool for developing 3D pharmacophore hypotheses and performing pharmacophore-based screening [16]. | |

| Similarity Searching & Docking | AutoDock Vina | A widely used open-source program for molecular docking and virtual screening [6]. |

| Open-Babel | A chemical toolbox designed to interconvert chemical file formats, crucial for preparing screening libraries [6]. |

The ligand-based drug design methodologies of QSAR, pharmacophore modeling, and similarity searching form a complementary and powerful toolkit for addressing the complex challenges in oncology research. While this guide has detailed their individual principles and protocols, their true strength lies in their integration. As demonstrated in the representative protocol, these methods can be chained together to create a robust pipeline that efficiently moves from target hypothesis to a shortlist of experimentally testable, high-confidence drug candidates.

The ongoing integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is profoundly transforming these classical approaches. AI-enhanced QSAR models offer superior predictive power, pharmacophore-informed generative models like TransPharmer enable the de novo design of novel scaffolds, and sophisticated similarity metrics powered by deep learning are improving the accuracy of virtual screening [15] [13] [14]. For the oncology researcher, mastering these core LBDD methodologies and their modern, AI-driven implementations is no longer optional but essential for accelerating the discovery of the next generation of precise and effective cancer therapeutics.

The Role of Molecular Descriptors and Conformational Sampling

Molecular descriptors and conformational sampling constitute foundational elements in modern ligand-based drug design (LBDD), particularly within oncology research where efficient lead optimization is critical. Molecular descriptors provide quantitative representations of chemical structures and properties, enabling the correlation of structural features with biological activity through quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling. Conformational sampling explores the accessible three-dimensional space of molecules, which is essential for accurately determining their bioactive conformations and for pharmacophore modeling. This technical guide examines advanced methodologies in molecular descriptor computation, conformational analysis techniques, and their integrated application in anticancer drug discovery, with specific protocols and resources to facilitate implementation by computational researchers and medicinal chemists.

Ligand-based drug design represents a crucial computational approach when the three-dimensional structure of the biological target is unavailable. Instead of relying on direct target structural information, LBDD infers binding characteristics from known active molecules that interact with the target [1] [17]. This approach has become indispensable in oncology drug discovery, where rapid identification and optimization of lead compounds against validated targets can significantly impact development timelines.

The fundamental hypothesis underlying LBDD is that similar molecules exhibit similar biological activities [1]. This principle enables researchers to identify novel chemotypes through scaffold hopping and optimize lead compounds based on quantitative structure-activity relationship models. In oncology applications, where molecular targets often include kinases, nuclear receptors, and various signaling proteins, LBDD provides valuable insights for compound optimization even when structural data for these targets remains limited.

Molecular Descriptors: Fundamentals and Applications

Definition and Significance

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations of molecular structures and properties that encode chemical information into a quantitative format suitable for statistical analysis and machine learning algorithms [1]. These descriptors serve as molecular "fingerprints" that correlate structural and physicochemical characteristics with biological activity, forming the basis for predictive modeling in drug discovery.

The primary objective of descriptor-based analysis is to establish mathematical relationships between chemical structure and pharmacological activity, enabling medicinal chemists to prioritize compounds for synthesis and biological evaluation [1]. In oncology research, this approach is particularly valuable for optimizing potency, selectivity, and ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) properties of anticancer agents.

Classification and Types of Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors can be categorized based on their dimensionality and the structural features they encode, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Descriptors with Applications in Oncology Drug Discovery

| Descriptor Type | Representation | Key Features | Oncology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D Descriptors | Global molecular properties | Molecular weight, logP, rotatable bonds, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors | Preliminary screening, ADMET prediction |

| 2D Descriptors | Structural fingerprints | Substructure keys, path-based fingerprints, circular fingerprints | High-throughput virtual screening, similarity searching |

| 3D Descriptors | Spatial molecular representation | Molecular shape, potential energy fields, surface properties | Pharmacophore modeling, 3D-QSAR, conformational analysis |

| Quantum Chemical Descriptors | Electronic distribution | HOMO/LUMO energies, molecular electrostatic potential, partial charges | Reactivity prediction, covalent binder design, metalloenzyme inhibitors |

Descriptor Selection and Optimization Strategies

Effective QSAR modeling requires careful selection of molecular descriptors to avoid overfitting and ensure model interpretability. Several statistical approaches are employed for descriptor selection:

- Multivariable Linear Regression (MLR): Systematically adds or eliminates molecular descriptors to identify the optimal combination that correlates with biological activity [1].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Reduces descriptor dimensionality by transforming possibly redundant variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components [1].

- Partial Least Squares (PLS): Combines features of MLR and PCA, particularly advantageous when dealing with multiple dependent variables or more descriptors than observations [1].

- Genetic Algorithms: Employ evolutionary operations to select descriptor subsets that maximize predictive performance while minimizing redundancy [1].

- Bayesian Regularized Neural Networks: Utilize a Laplacian prior to automatically prune ineffective descriptors during model training [1].

For oncology applications, domain knowledge should guide initial descriptor selection, incorporating features relevant to anticancer activity such as hydrogen bonding capacity for kinase inhibitors, aromatic features for intercalating agents, and specific structural alerts for toxicity prediction.

Conformational Sampling: Methodologies and Protocols

Theoretical Basis and Significance

Conformational sampling refers to the computational process of exploring the accessible three-dimensional arrangements of a molecule by rotating around its flexible bonds [11]. This procedure is fundamental to ligand-based drug design because the biological activity of a compound depends not only on its chemical structure but also on its ability to adopt a conformation complementary to the target binding site.

The challenge of conformational sampling escalates significantly with molecular size and flexibility. For macrocyclic peptides and other constrained structures common in oncology therapeutics, the number of accessible conformers grows exponentially due to increased degrees of freedom, making exhaustive conformational sampling both computationally challenging and critically important for accurate predictions [17].

Conformational Sampling Techniques

Multiple computational approaches have been developed to address the conformational sampling problem, each with specific strengths and limitations:

Systematic Search Methods exhaustively explore the conformational space by incrementally rotating each rotatable bond through defined intervals. While comprehensive for small molecules, this approach becomes computationally prohibitive for compounds with numerous rotatable bonds.

Stochastic Methods, including Monte Carlo simulations and genetic algorithms, randomly sample conformational space through random changes to dihedral angles or molecular coordinates. These methods efficiently explore diverse conformational regions but may miss energetically favorable conformations.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations model the time-dependent evolution of molecular structure by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion. MD provides insights into conformational dynamics and flexibility but requires substantial computational resources for adequate sampling of relevant timescales [18].

Umbrella Sampling enhances sampling along specific reaction coordinates by applying bias potentials that constrain the system to predefined regions of conformational space. This method is particularly valuable for studying transitions between conformational states and calculating associated free energy changes [18] [19].

Protocol: Conformational Sampling for Pharmacophore Modeling

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach to conformational sampling for pharmacophore generation in ligand-based drug design:

Molecular Preparation

- Generate 3D structures from 2D representations using programs like CORINA or OMEGA

- Assign proper protonation states corresponding to physiological pH (7.4)

- Perform initial geometry optimization using molecular mechanics force fields (MMFF94, GAFF)

Conformational Exploration

- Apply a systematic or stochastic search algorithm to generate diverse conformers

- Set energy window threshold to 10-15 kcal/mol above the global minimum to include biologically relevant conformations

- Implement redundancy checking using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) criteria (typically 0.5 Å)

Conformer Selection and Analysis

- Cluster similar conformations using hierarchical or k-means clustering based on torsion angles or atomic coordinates

- Select representative conformers from each cluster for subsequent analysis

- Evaluate conformational coverage using spatial parameters relevant to molecular recognition

Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation

- Identify common chemical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, aromatic rings, ionizable groups) across active conformations

- Define spatial relationships between features using distance and angle constraints

- Validate the pharmacophore model using known inactive compounds to eliminate false positives

Integrated Workflows in Oncology Drug Discovery

Combined Ligand-Based and Structure-Based Approaches

Modern drug discovery increasingly leverages both ligand-based and structure-based methods in complementary workflows, as illustrated in Figure 1. This integrated approach maximizes the utility of available chemical and structural information, particularly valuable in oncology where target information may be incomplete.

Figure 1: Integrated drug discovery workflow combining ligand-based and structure-based approaches

Machine Learning-Enhanced QSAR Modeling

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have significantly enhanced QSAR modeling capabilities [20] [21]. Traditional ML models require explicit feature engineering and descriptor selection, while DL algorithms can automatically learn relevant feature representations from raw molecular input.

The integration of wet laboratory experiments, molecular dynamics simulations, and machine learning techniques creates a powerful iterative framework for QSAR model development [21]. Molecular dynamics provides mechanistic interpretation at atomic/molecular levels, while experimental data offers reliable verification of model predictions, creating a virtuous cycle of model refinement and validation.

Protocol: QSAR Model Development and Validation

A robust QSAR modeling workflow involves multiple stages to ensure predictive reliability:

Data Curation

- Collect biological activity data (IC50, Ki, EC50) for a congeneric series with adequate chemical diversity

- Apply rigorous curation to remove duplicates, errors, and compounds with uncertain activity measurements

- Divide dataset into training (70-80%), validation (10-15%), and test sets (10-15%) using rational splitting methods

Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing

- Compute relevant 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors using software such as Dragon or RDKit

- Remove descriptors with low variance or high correlation to reduce dimensionality

- Apply appropriate data scaling (autoscaling, range scaling) to normalize descriptor values

Model Building

- Select appropriate algorithm based on dataset size and complexity (PLS for linear relationships, random forest or neural networks for non-linear patterns)

- Implement feature selection using genetic algorithms, recursive feature elimination, or Bayesian methods

- Optimize hyperparameters through grid search or Bayesian optimization with cross-validation

Model Validation

- Perform internal validation using k-fold cross-validation (typically 5-10 folds) and calculate Q²

- Apply external validation using the held-out test set to assess predictive performance

- Utilize Y-randomization to confirm model robustness against chance correlations

- Define applicability domain to identify compounds for which predictions are reliable

Model Interpretation and Application

- Identify critical molecular descriptors and their relationship to biological activity

- Utilize the model to predict activity of virtual compounds and prioritize synthesis candidates

- Iteratively refine the model as new experimental data becomes available

Computational Tools and Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of molecular descriptor analysis and conformational sampling requires specialized software tools and computational resources. Table 2 summarizes essential resources for establishing a computational drug discovery pipeline in oncology research.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Descriptor Analysis and Conformational Sampling

| Tool Category | Software/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | Dragon, RDKit, PaDEL | Compute 1D-3D molecular descriptors | QSAR model development, similarity assessment |

| Conformational Sampling | OMEGA, CONFLEX, MacroModel | Generate representative conformer ensembles | Pharmacophore modeling, 3D-QSAR, shape-based screening |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Simulate temporal evolution of molecular structure | Conformational dynamics, binding mechanism studies |

| Machine Learning | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, DeepChem | Build predictive QSAR models | Activity prediction, toxicity assessment, property optimization |

| Visualization & Analysis | PyMOL, Chimera, Maestro | Molecular visualization and interaction analysis | Result interpretation, hypothesis generation |

Applications in Oncology Drug Discovery

Molecular descriptors and conformational sampling techniques have enabled significant advances in anticancer drug development across multiple target classes:

Kinase Inhibitor Design: 3D-QSAR models combining steric, electrostatic, and hydrogen-bonding descriptors have guided the optimization of selective kinase inhibitors, minimizing off-target effects while maintaining potency against oncology targets.

Epigenetic Target Modulation: For targets such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) and bromodomain-containing proteins, conformational sampling of flexible linkers has been crucial in designing effective protein-domain binders with improved cellular permeability.

PROTAC Design: The development of proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) benefits extensively from conformational sampling to model the ternary complex formation between the target protein, E3 ligase, and bifunctional degrader molecule [22].

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): Descriptor-based approaches optimize the chemical properties of warhead molecules, linker stability, and conjugation chemistry to improve therapeutic index and reduce systemic toxicity [22] [23].

Molecular descriptors and conformational sampling represent cornerstone methodologies in ligand-based drug design with profound implications for oncology research. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, the integration of these techniques with experimental data and structural biology will continue to enhance their predictive accuracy and utility. The ongoing development of machine learning approaches, particularly deep learning architectures that operate directly on molecular graphs or 3D structures, promises to further revolutionize this field by enabling more accurate activity predictions and efficient exploration of chemical space. For oncology researchers, mastery of these computational techniques provides powerful tools to accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel therapeutic agents against challenging cancer targets.

The development of new oncology treatments is critically important, with cancer affecting one in three to four people globally and projected to reach 35 million new cases annually by 2050 [24]. However, the drug discovery process remains extraordinarily challenging, with success rates for cancer drugs sitting well below 10% and an estimated 1 in 20,000-30,000 compounds progressing from initial development to marketing approval [24]. Ligand-based drug design (LBDD) represents a powerful computational approach that accelerates oncology drug discovery by leveraging known bioactive compounds, particularly when three-dimensional target protein structures are unavailable. This whitepaper examines the technical methodologies, advantages, and experimental protocols of LBDD, demonstrating how it enhances efficiency in hit identification, reduces resource expenditure, and enables targeting of previously "undruggable" proteins through integration with emerging technologies.

Ligand-based drug design is a computational methodology employed when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown or difficult to obtain [20] [25]. Instead of relying on direct structural information of the target, LBDD infers critical binding characteristics from known active molecules that bind and modulate the target's function [17]. This approach has become indispensable in oncology research, where many therapeutic targets lack experimentally determined structures due to technical challenges such as membrane protein complexity or conformational flexibility [25].

The fundamental premise of LBDD is the "similarity principle" – structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [17]. By quantitatively analyzing the chemical features, physicochemical properties, and spatial arrangements of known active compounds, researchers can build predictive models to identify new chemical entities with enhanced therapeutic potential for cancer treatment. LBDD serves as a strategic starting point in early-stage drug discovery when structural information is sparse, with its inherent speed and scalability making it particularly attractive for initial hit identification campaigns [17].

Key Methodologies in Ligand-Based Drug Design

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR modeling employs statistical and machine learning methods to establish mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors and biological activity [17] [20]. These models quantitatively correlate structural features of compounds with their pharmacological properties, enabling prediction of activity for novel compounds before synthesis.

Experimental Protocol: QSAR Model Development

- Data Curation: Collect chemical structures and corresponding bioactivity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) for a series of compounds with known activity against the oncology target.

- Molecular Descriptor Calculation: Generate numerical representations of molecular structures using descriptors such as:

- Physicochemical properties (logP, molecular weight, polar surface area)

- Electronic parameters (HOMO/LUMO energies, partial charges)

- Topological descriptors (molecular connectivity indices)

- 3D-field descriptors (molecular shape, electrostatic potentials)

- Feature Selection: Identify the most relevant descriptors contributing to biological activity using statistical methods (genetic algorithms, stepwise regression).

- Model Building: Apply machine learning algorithms (multiple linear regression, partial least squares, random forest, support vector machines) to establish the mathematical relationship between descriptors and activity.

- Model Validation: Assess predictive performance using cross-validation and external test sets to ensure robustness and prevent overfitting.

Recent advances in 3D-QSAR methods, particularly those grounded in causal, physics-based representations of molecular interactions, have improved their ability to predict activity even with limited structure-activity data [17]. Unlike traditional 2D-QSAR models that require large datasets, these advanced 3D-QSAR approaches can generalize well across chemically diverse ligands for a given target [17].

Pharmacophore Modeling

A pharmacophore model abstractly defines the essential steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition at a therapeutic target [25]. It captures the key interactions between a ligand and its target without reference to explicit molecular structure.

Experimental Protocol: Pharmacophore Model Development

- Ligand Set Selection: Choose a structurally diverse set of known active compounds with varying potency levels.

- Conformational Analysis: Generate representative conformational ensembles for each ligand to account for flexibility.

- Molecular Superimposition: Align compounds based on common chemical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, charged groups).

- Feature Abstraction: Identify the conserved spatial arrangement of features responsible for biological activity.

- Model Validation: Test the model's ability to discriminate between known active and inactive compounds, then use it for virtual screening of compound libraries.

Similarity-Based Virtual Screening

Similarity-based virtual screening compares candidate molecules against known active compounds using molecular fingerprints or 3D shape descriptors [17]. This technique rapidly identifies potential hits from large chemical libraries by measuring structural similarity to established actives.

Experimental Protocol: Similarity-Based Virtual Screening

- Reference Compound Selection: Choose one or more confirmed active compounds with desired activity profile.

- Molecular Representation: Encode reference and database compounds using appropriate descriptors:

- 2D fingerprints (ECFP, FCFP, MACCS keys)

- 3D shape descriptors (ROCS, Phase Shape)

- Electrostatic potential maps

- Similarity Calculation: Compute similarity metrics (Tanimoto coefficient, Euclidean distance, cosine similarity) between reference and database compounds.

- Compound Ranking: Prioritize compounds based on similarity scores for further experimental testing.

Successful 3D similarity-based virtual screening requires accurate ligand structure alignment with known active molecules [17]. Additionally, alignments of multiple known active compounds can help generate a meaningful binding hypothesis for screening large compound libraries [17].

Comparative Advantages of Ligand-Based Approaches

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Drug Discovery Approaches in Oncology

| Parameter | Ligand-Based Design | Structure-Based Design | Traditional Experimental Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Requirements | Weeks to months for virtual screening | Months for structure determination plus screening | 6-12 months for HTS campaigns |

| Cost Implications | Significant reduction in synthetic and screening costs | Moderate reduction, requires structural biology resources | High costs for compounds and screening (>$1-2 million per HTS) |

| Structural Dependency | No protein structure required | High-quality 3D structure essential | No structural information needed |

| Success Rates | Improved hit rates through enrichment | Variable, dependent on structure quality | Typically <0.01% hit rate in HTS |

| Chemical Space Coverage | Can explore 10⁶-10⁹ compounds virtually | Limited by docking computation time | Typically 10⁵-10⁶ compounds physically screened |

| Resource Requirements | Moderate computational resources | High computational and experimental resources | High laboratory and compound resources |

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics of Ligand-Based Design Methods

| Method | Typical Application | Data Requirements | Enrichment Factor | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-QSAR | Lead optimization, property prediction | 20-50 compounds with activity data | 5-20x | Struggles with novel chemical scaffolds |

| 3D-QSAR | Scaffold hopping, novel hit identification | 15-30 aligned active compounds | 10-50x | Dependent on molecular alignment |

| Pharmacophore Screening | Virtual screening, scaffold hopping | 5-15 diverse active compounds | 10-100x | Sensitive to conformational sampling |

| Similarity Searching | Hit identification, library design | 1-5 known active compounds | 5-30x | Limited by reference compound choice |

Speed and Efficiency Advantages

Ligand-based approaches significantly accelerate early-stage oncology drug discovery by leveraging existing chemical and biological knowledge. The computational nature of these methods enables rapid evaluation of millions of compounds in silico before committing to synthetic efforts [17]. This virtual screening capability is particularly valuable in oncology, where chemical starting points are needed quickly for validation of novel targets emerging from genomic and proteomic studies.

The sequential integration of ligand-based and structure-based methods represents an optimized workflow for hit identification [17]. Large compound libraries are first filtered with rapid ligand-based screening based on 2D/3D similarity to known actives or via QSAR models. The most promising subset then undergoes more computationally intensive structure-based techniques like molecular docking [17]. This two-stage process improves overall efficiency by applying resource-intensive methods only to a narrowed set of candidates, making it particularly advantageous when time and resources are constrained [17].

Cost-Efficiency and Resource Optimization

The substantial cost reductions afforded by LBDD stem from several factors. By prioritizing compounds computationally, LBDD dramatically reduces the number of molecules that require synthesis and experimental testing [26]. This optimization is crucial in oncology research, where biological assays involving cell lines, primary tissues, or animal models are exceptionally resource-intensive.

Traditional high-throughput screening campaigns typically test hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds at significant expense, with success rates generally below 0.01% [20]. In contrast, virtual screening using LBDD methods can enrich hit rates by 10-100 fold, enabling researchers to focus experimental efforts on the most promising candidates [17]. This efficiency is particularly valuable for academic research groups and small biotech companies with limited screening budgets.

Capabilities When Target Structures Are Unavailable

LBDD provides a powerful solution for one of the most significant challenges in oncology drug discovery: targeting proteins that resist structural characterization [25]. Many important cancer targets, including various membrane receptors and protein-protein interaction interfaces, are difficult to study using structural methods like X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM due to challenges with expression, purification, or crystallization [25].

Even when structural information becomes available later in the discovery process, ligand-based approaches continue to provide value through their ability to infer critical binding features from known active molecules and excel at pattern recognition and generalization [17]. This complementary perspective often reveals structure-activity relationships that might be overlooked in purely structure-based approaches.

Integration with Advanced Technologies

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Enhancements

Machine learning has revolutionized LBDD by enabling the extraction of complex patterns from molecular structures that may not be captured by traditional QSAR approaches [20]. Deep learning algorithms, particularly graph neural networks and chemical language models, can automatically learn feature representations from raw molecular data with minimal human intervention [20] [27].

The DRAGONFLY framework exemplifies this advancement, utilizing interactome-based deep learning that combines graph neural networks with chemical language models for ligand-based generation of drug-like molecules [27]. This approach capitalizes on drug-target interaction networks, enabling the "zero-shot" construction of compound libraries tailored to possess specific bioactivity, synthesizability, and structural novelty without requiring application-specific reinforcement or transfer learning [27].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ligand-Based Drug Design

| Research Tool | Function | Application in Oncology |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases (ChEMBL, ZINC, PubChem) | Source of chemical structures and bioactivity data | Provides known active compounds for model building |

| Molecular Descriptors (ECFP, CATS, USRCAT) | Numerical representation of molecular features | Enables QSAR modeling and similarity searching |

| Machine Learning Platforms (scikit-learn, DeepChem) | Implementation of ML algorithms for model development | Builds predictive models for anticancer activity |

| 3D Conformational Generators (OMEGA, CONFIRM) | Samples accessible 3D shapes of molecules | Essential for 3D-QSAR and pharmacophore modeling |

| Similarity Metrics (Tanimoto, Tversky) | Quantifies structural resemblance between molecules | Ranks database compounds for virtual screening |

Synergy with Targeted Protein Degradation

LBDD has found particular utility in the emerging field of targeted protein degradation (TPD), which employs small molecules to tag undruggable proteins for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system [26]. This approach provides a means to address previously untargetable proteins in oncology, offering a new therapeutic paradigm [26].

For degrader design, LBDD helps identify appropriate ligand warheads for both the target protein and E3 ubiquitin ligase, even when structural information about the ternary complex is unavailable. The optimal linker connecting these warheads can be designed using QSAR approaches that correlate linker properties with degradation efficiency [26].

Experimental Validation and Case Studies

The practical utility of LBDD in oncology is demonstrated by its successful application in various drug discovery programs. The DRAGONFLY framework has been prospectively validated through the generation of novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) ligands, with top-ranking designs chemically synthesized and exhibiting favorable activity and selectivity profiles [27]. Crystal structure determination of the ligand-receptor complex confirmed the anticipated binding mode, validating the computational predictions [27].

In comparative studies, DRAGONFLY demonstrated superior performance over standard chemical language models across the majority of templates and properties examined [27]. The framework consistently generated molecules with enhanced synthesizability, novelty, and predicted bioactivity for well-studied oncology targets including nuclear hormone receptors and kinases [27].

Diagram 1: Ligand-Based Drug Design Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the sequential process of LBDD application in oncology, from initial data collection to experimental validation.

Diagram 2: Core Advantages of LBDD. This diagram highlights the key benefits of ligand-based approaches in oncology drug discovery.

Ligand-based drug design represents a sophisticated computational approach that addresses critical challenges in oncology drug discovery. By leveraging known bioactive compounds, LBDD accelerates hit identification, optimizes resource allocation, and enables targeting of proteins that resist structural characterization. The integration of LBDD with machine learning and emerging modalities like targeted protein degradation further expands its utility in developing novel cancer therapeutics. As these computational methodologies continue to evolve alongside experimental technologies, LBDD will play an increasingly vital role in advancing precision oncology and delivering innovative treatments to cancer patients.

Modern LBDD Workflows: From AI Screening to Clinical Candidates

Integrating AI and Machine Learning for Enhanced Virtual Screening

Virtual screening has become an indispensable tool in modern oncology drug discovery, dramatically accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic candidates. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has transformed this field from a relatively simplistic molecular docking exercise into a sophisticated, predictive science. Within ligand-based drug design—an approach critical for targets with poorly characterized or unknown 3D structures—AI enhances the ability to decipher complex relationships between chemical structure and biological activity. This is particularly vital in oncology, where the need for effective, targeted therapies is urgent. By leveraging AI, researchers can now sift through millions of compounds in silico to identify promising hits with a higher probability of success in preclinical and clinical stages, thereby reducing costs and development timelines [3] [28].

The traditional drug discovery process is notoriously lengthy, often exceeding a decade, and costly, with investments frequently surpassing $1-2.6 billion per approved drug [3]. AI-driven virtual screening confronts these challenges directly by introducing unprecedented efficiency and predictive power. In the specific context of ligand-based design for oncology, these technologies excel by learning from existing data on bioactive molecules. They can identify subtle, non-linear patterns in chemical data that are often imperceptible to human researchers, enabling the prediction of anti-cancer activity, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic properties prior to synthesis or testing [29] [28]. This capability is reshaping the early discovery pipeline, making the search for new cancer treatments more rational, data-driven, and effective.

Core AI Methodologies in Virtual Screening

The application of AI in virtual screening encompasses a diverse set of methodologies, each suited to particular tasks and data types. Understanding these core techniques is essential for deploying them effectively in oncology-focused ligand-based drug design.

Table 1: Core AI and ML Methodologies in Virtual Screening

| Methodology | Key Function | Application in Virtual Screening | Representative Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Learns a mapping function from labeled input data to outputs. | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, prediction of binding affinity/IC50, toxicity, and ADMET properties. | Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Deep Neural Networks [29] [28] |

| Unsupervised Learning | Discovers hidden patterns or intrinsic structures in unlabeled data. | Chemical clustering, diversity analysis, dimensionality reduction of chemical libraries, identification of novel compound classes. | k-means Clustering, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [29] |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Models complex, non-linear relationships using multi-layered neural networks. | Direct learning from molecular structures (SMILES, graphs), de novo molecular design, advanced bioactivity prediction. | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [29] [3] |

| Generative Models | Learns the underlying data distribution to generate new, similar data instances. | De novo design of novel molecular structures with optimized properties for specific oncology targets. | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [29] |

A pivotal advancement is the development of quantitative pharmacophore activity relationship (QPhAR) modeling. Unlike traditional QSAR, which uses molecular descriptors, QPhAR utilizes abstract pharmacophoric features—representations of steroelectronic molecular interactions—as input for building predictive models. This abstraction reduces bias toward overrepresented functional groups in small datasets and enhances the model's ability to generalize, facilitating scaffold hopping to identify structurally distinct compounds with similar interaction patterns [30] [16]. This method has been validated on diverse datasets, demonstrating robust predictive performance even with limited training data (15-20 samples), making it highly suitable for lead optimization in drug discovery projects [16].

Experimental Protocols for AI-Enhanced Virtual Screening

Implementing a successful AI-driven virtual screening campaign requires a methodical, multi-stage workflow. The following protocols detail the key steps, from data preparation to experimental validation.

Protocol 1: QSAR Model Development and Validation for Anti-Breast Cancer Agents

This protocol is adapted from a study designing quinazolin-4(3H)-ones as breast cancer inhibitors [31].

Data Set Curation and Preparation

- Compound Selection: A series of 35 quinazolin-4(3H)-one derivatives with known experimental half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values against breast cancer cell lines were sourced from literature.

- Activity Representation: Biological activities (IC50 in µM) were converted to pIC50 (-log IC50) for analysis.

- Structure Optimization: 2D structures were sketched using ChemDraw software and converted to 3D formats. Geometry optimization was performed using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with a B3LYP/6-31G* basis set in Spartan v14.0 to obtain the most stable conformers.

Descriptor Calculation and Data Preprocessing

- Descriptor Calculation: Optimized 3D structures were used to compute molecular descriptors using the PADEL descriptor toolkit.

- Data Pretreatment: Calculated descriptors were pretreated to remove constants and highly correlated variables, reducing noise and redundancy.