Leveraging PLS Regression in 3D-QSAR Modeling for Advanced MCF-7 Breast Cancer Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression in three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling for the discovery of novel inhibitors targeting the...

Leveraging PLS Regression in 3D-QSAR Modeling for Advanced MCF-7 Breast Cancer Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression in three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling for the discovery of novel inhibitors targeting the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of 3D-QSAR, details the critical role of PLS regression in building robust predictive models, and offers practical guidance for model optimization and troubleshooting. By synthesizing recent case studies and methodological advances, the content also covers rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses with other computational techniques, serving as a valuable resource for accelerating the design of potent and selective anti-breast cancer agents.

Foundations of 3D-QSAR and PLS Regression for MCF-7 Breast Cancer Research

The MCF-7 cell line, established in 1973 by Dr. Soule and colleagues at the Michigan Cancer Foundation, represents one of the most pivotal in vitro models in breast cancer research [1]. This cell line was isolated from the pleural effusion of a 69-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer who had undergone multiple treatments, including mastectomy and hormone therapy [1]. A landmark discovery in 1973 revealed that MCF-7 cells expressed the estrogen receptor (ER), fundamentally shaping our understanding of hormone-responsive breast cancers and establishing this cell line as the cornerstone for studying ER-positive breast cancer biology [1]. The subsequent demonstration in 1975 that the anti-estrogen tamoxifen inhibited MCF-7 growth—an effect reversible by estrogen—further cemented its utility for testing endocrine therapies [1].

Over more than four decades of continuous use, MCF-7 has generated more practical knowledge for patient care than any other breast cancer cell line [1]. Its enduring relevance stems from its ability to model luminal A molecular subtype characteristics, being ER-positive and progesterone receptor (PR)-positive, while exhibiting poorly aggressive and non-invasive behavior in its parental form [1]. This review comprehensively details the MCF-7 cell line's characteristics and its indispensable role in modern drug discovery, with particular emphasis on its application in 3D-QSAR modeling utilizing PLS regression analysis.

Molecular and Phenotypic Characterization of MCF-7

Core Molecular Profile

MCF-7 cells exhibit a well-defined molecular signature that makes them particularly suitable for breast cancer research and drug discovery. As estrogen-sensitive cells, their proliferation depends on 17β-estradiol (E2) stimulation [1]. They express high levels of ERα transcripts with comparatively lower expression of ERβ, and demonstrate strong PR expression in the parental line [1]. Beyond nuclear hormone receptors, MCF-7 cells express moderate levels of plasma membrane-associated growth factor receptors, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) [1].

These cells maintain features of differentiated mammary epithelium, expressing epithelial markers such as E-cadherin, β-catenin, and cytokeratin 18, while remaining negative for mesenchymal markers like vimentin and smooth muscle actin [1]. They also maintain expression of intercellular junction proteins including claudins and zona occludens protein 1 (ZO-1), but are notably CD44-deficient [1]. This molecular profile creates a defined system for investigating hormone-responsive breast cancer pathways and testing targeted therapies.

Heterogeneity and Cellular Plasticity

Despite often being treated as a uniform entity, the MCF-7 line actually comprises numerous individual phenotypes with variations in gene expression profiles, receptor expression, and signaling pathways [1]. This heterogeneity manifests cytogenetically as extensive aneuploidy, with chromosome numbers ranging from 60 to 140 across different variants [1]. This genetic instability enables the emergence of sub-lines under selective pressures, mirroring the clinical development of anti-estrogen therapy resistance in breast cancer patients [1].

Recent research demonstrates that MCF-7 cells can undergo significant phenotypic changes when exposed to different microenvironmental conditions. Successive co-culture with hematopoietic cells and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells induces stable morphologic, behavioral, and gene expressional changes, including reduced E-cadherin and estrogen receptor α, along with loss of progesterone receptor [2]. This plasticity enables the study of cancer cell heterogeneity during breast cancer progression and metastasis.

Table 1: Key Molecular Characteristics of MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Line

| Feature Category | Specific Characteristic | Expression/Status in MCF-7 |

|---|---|---|

| Hormone Receptors | Estrogen Receptor α (ERα) | High expression [1] |

| Estrogen Receptor β (ERβ) | Low expression [1] | |

| Progesterone Receptor (PR) | Strong in parental line [1] | |

| Growth Factor Receptors | EGFR (HER1) | Moderate expression [1] |

| HER2 | Present [1] | |

| IGF-IR | Responsive to signaling [1] | |

| Epithelial Markers | E-cadherin | Positive [1] |

| β-catenin | Positive [1] | |

| Cytokeratin 18 | Positive [1] | |

| Mesenchymal Markers | Vimentin | Negative [1] |

| Smooth Muscle Actin | Negative [1] | |

| Other Markers | CD44 | Deficient [1] |

| Claudins/ZO-1 | Positive [1] |

MCF-7 in Modern Drug Discovery Paradigms

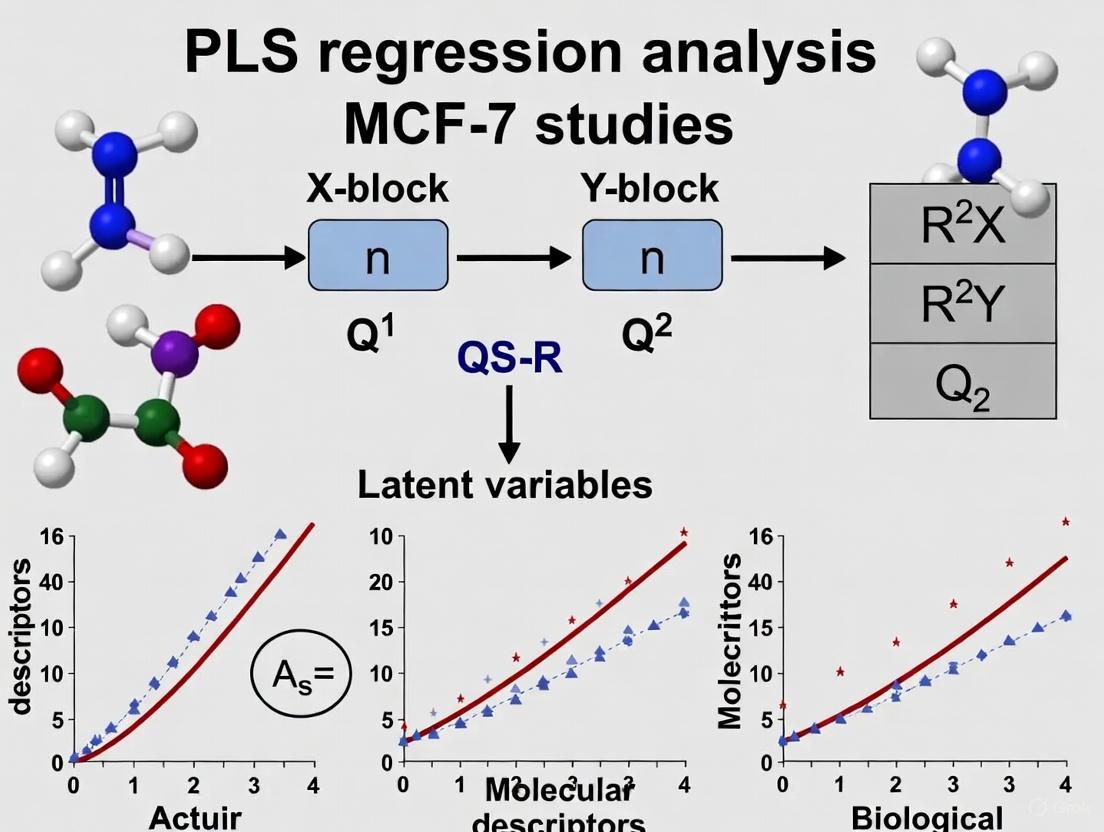

3D-QSAR and PLS Regression Analysis

Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling represents a powerful computational approach in breast cancer drug discovery, with MCF-7 serving as the primary biological validation system. This methodology quantitatively correlates the three-dimensional molecular structures of compounds with their biological activities against MCF-7 cells, typically measured as half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) values converted to pIC₅₀ (-log IC₅₀) for modeling [3] [4]. The core computational technique employed in these analyses is Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, which effectively handles the multidimensional nature of 3D molecular descriptors while mitigating issues of collinearity [4].

The typical 3D-QSAR workflow begins with molecular alignment, where compounds are spatially superimposed based on their predicted pharmacophoric features [5]. Subsequently, molecular field descriptors are calculated using either Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) or Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) methodologies [3]. These descriptors capture essential steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding properties that influence biological activity. Recent studies have demonstrated robust 3D-QSAR models with high predictive power, including CoMFA (Q² = 0.62, R² = 0.90) and CoMSIA (Q² = 0.71, R² = 0.88) models for tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives, validated through external validation (R²ext = 0.90 and R²ext = 0.91, respectively) [3].

The application of these models has successfully identified novel inhibitor candidates with significant binding affinities and robust stabilities, as confirmed through molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and binding free energy calculations [3]. For natural products like maslinic acid analogs, 3D-QSAR modeling has yielded excellent statistical parameters (r² = 0.92, q² = 0.75), enabling virtual screening of potential analogs and identification of compound P-902 as a promising hit against multiple targets including AKR1B10, NR3C1, PTGS2, and HER2 [4].

Diagram 1: 3D-QSAR Workflow with PLS Regression

Advanced Cell Culture Models: 3D Spheroid Systems

Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture models have significant limitations in replicating the physiological microenvironment of solid tumors. To address this, three-dimensional (3D) spheroid culture systems have been developed for MCF-7 cells, creating more clinically relevant models for drug screening [6]. These tumoroids exhibit drug resistance profiles more closely resembling solid tumors, making them particularly valuable for preclinical drug development [6].

A recently developed protocol enables robust MCF-7 spheroid growth using U-bottom, clear, cell-repellent surface 96-well plates [6]. The methodology involves seeding 500-5,000 cells per well in phenol red-free DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.01 mg/ml bovine insulin, 10 nM estradiol, and standard antibiotics [6]. Critical technical aspects include careful medium exchange every two days and minimal disturbance during handling. Under these conditions, MCF-7 cells form single spheroids per well that can be maintained for over 30 days, with spheroid volume increasing over a hundred-fold [6].

Notably, drug sensitivity profiles differ significantly between 2D and 3D cultures. Research using 3D MCF-7 spheroids suggests that estrogen sulfotransferase, steroid sulfatase, and the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor may play critical roles in spheroid growth, while estrogen receptors α and β may have diminished importance in this context [6]. This model system enables more physiologically relevant assessment of compound efficacy and has potential for personalized cancer drug development using patient-derived tumor tissues [6].

Table 2: Experimental Systems for MCF-7 in Drug Discovery

| System Type | Key Features | Applications in Drug Discovery | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Monolayer Culture | Standard adherent growth; High-throughput capability | Primary compound screening; Mechanism of action studies | [1] |

| 3D Spheroid Culture | Physiologically relevant microenvironment; Gradient conditions | Advanced efficacy assessment; Resistance mechanism studies | [6] |

| Co-culture Systems | Interaction with bystander cells (HSCs, MSCs) | Metastasis and heterogeneity studies; Microenvironment interactions | [2] |

| Computational 3D-QSAR | Structure-activity relationship modeling; Virtual screening | Lead identification and optimization; Activity prediction | [3] [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard MCF-7 Cell Culture Protocol

Materials Required:

- MCF-7 human breast cancer cells (ATCC HTB-22)

- Low glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM)

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS)

- 2 mM glutamine

- 0.01 mg/ml insulin

- 1% penicillin/streptomycin mix

- T75 culture flasks

- Incubator maintained at 37°C with 5% CO₂

Procedure:

- Seed MCF-7 cells in T75 flasks at a density of 1×10⁶ cells/flask in complete medium [1].

- Culture cells in low glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 0.01 mg/ml insulin, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin [1].

- Maintain cultures at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO₂.

- Renew culture medium twice weekly.

- Passage cells weekly at a sub-cultivation ratio of 1:3 using standard trypsinization procedures [1].

3D Spheroid Culture Protocol for Drug Screening

Materials Required:

- U-bottom, clear, cell-repellent surface 96-well plates (e.g., Greiner Bio-One)

- Phenol red-free DMEM medium (Life Technologies)

- Fetal bovine serum (Quality Biological Inc.)

- 100× penicillin/streptomycin solution

- 100× glutamine solution

- 0.01 mg/ml bovine insulin

- 10 nM estradiol

Procedure:

- Expand MCF-7 cells using standard 2D culture conditions to generate sufficient cell numbers [6].

- Prepare single-cell suspension and seed 500-5,000 cells per well in 200 μL of complete medium into U-bottom 96-well plates [6].

- Centrifuge plates at 1000 RPM for 5 minutes to encourage cell aggregation at the well bottom.

- Carefully transfer plates to incubator and maintain at 37°C with 5% CO₂ without disturbance.

- Every two days, carefully remove 150 μL of medium (approximately 75%) using a 200 μL multichannel pipette held at a 90° angle to the well, and replace with fresh pre-warmed medium [6].

- For drug treatment studies, add compounds after each medium change, using appropriate vehicle controls.

- Monitor spheroid growth and morphology regularly using microscopy, measuring spheroid diameter and calculating volume using the formula: V = 4/3πr³.

- Culture can be maintained for over 30 days with careful handling and regular medium exchange [6].

3D-QSAR Model Development Protocol

Materials Required:

- SYBYL-X 2.1 software (Certara) or equivalent molecular modeling platform

- Dataset of compounds with known MCF-7 inhibitory activities (IC₅₀ values)

- Computational resources for molecular dynamics simulations

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Collect a series of compounds with experimentally determined IC₅₀ values against MCF-7 cells. Convert IC₅₀ to pIC₅₀ (-log IC₅₀) for QSAR analysis [3].

- Molecular Structure Preparation: Build 3D structures of all compounds and optimize geometries using appropriate force fields (e.g., Tripos force field) [3].

- Molecular Alignment: Select the most active compound as template and align all molecules to this template using field-based or feature-based alignment methods [3] [5].

- Descriptor Calculation: Calculate 3D field descriptors using CoMFA (steric and electrostatic fields) and/or CoMSIA (additional hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor fields) [3].

- PLS Model Development: Use Partial Least Squares regression to correlate molecular descriptors with biological activity. Determine optimal number of components using cross-validation [4].

- Model Validation: Validate model using leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation and external test set validation. Acceptable models should have q² > 0.5 and r² > 0.8 [4] [5].

- Model Application: Use validated model to predict activities of virtual compounds and guide lead optimization efforts.

Diagram 2: Experimental-Digital Workflow Integration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MCF-7 Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | Low glucose DMEM with phenol red-free option | Supports MCF-7 growth while eliminating estrogenic effects of phenol red | [1] [6] |

| Culture Supplements | Fetal Bovine Serum (10%), Insulin (0.01 mg/mL) | Provides essential growth factors and hormones | [1] [6] |

| Hormone/Inhibitors | 17β-estradiol, Tamoxifen, ICI 182,780 | Modulates estrogen signaling pathways; positive/negative controls | [1] [6] |

| 3D Culture Systems | U-bottom low attachment plates, Extracellular matrix hydrogels | Enables spheroid formation mimicking tumor microenvironment | [6] |

| Viability Assays | MTT, WST-1, Resazurin reduction assays | Quantifies cell viability and compound cytotoxicity | [5] |

| Computational Tools | SYBYL, Forge, Molecular docking software | Enables 3D-QSAR modeling and virtual screening | [3] [4] |

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

The application of MCF-7 cells in drug discovery continues to evolve with emerging technologies. Recent advances include the development of novel nanocarrier systems for targeted drug delivery, such as silver nanoparticle-paclitaxel (AgNPs@PTX) conjugates that demonstrate enhanced cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells (IC₅₀ = 1.7 μg/mL) compared to single agents [7]. These approaches address limitations of conventional chemotherapy by improving solubility, permeability, and targeted delivery while reducing systemic toxicity.

Another significant advancement involves understanding cellular plasticity in response to microenvironmental signals. Research demonstrates that serotonin (5-HT) signaling can modulate breast cancer cell behavior, promoting aggressive features through downregulation of hormone receptors and HER2, effectively inducing a triple-negative-like phenotype in MCF-7 cells [8]. This phenotypic plasticity underscores the importance of microenvironmental factors in cancer progression and therapeutic response.

The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation represents the most promising future direction. As 3D-QSAR models become increasingly sophisticated through machine learning approaches and more diverse training sets, their predictive accuracy for MCF-7 cytotoxicity continues to improve. These computational tools, combined with physiologically relevant 3D culture models and high-content screening approaches, create a powerful platform for accelerating breast cancer drug discovery and development.

Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) represents a pivotal computational methodology in modern ligand-based drug design, enabling researchers to correlate the three-dimensional molecular properties of compounds with their biological activity [9]. In the context of breast cancer research, particularly against the MCF-7 cell line—a well-characterized estrogen receptor alpha (ER-α) positive model derived from human breast adenocarcinoma—3D-QSAR techniques have become indispensable for developing novel therapeutic agents [5]. Unlike traditional QSAR that utilizes computed molecular descriptors, 3D-QSAR methodologies analyze spatial molecular interaction fields, providing visual contours that guide medicinal chemists in optimizing compound structures for enhanced potency [3] [10].

The foundational principle of 3D-QSAR rests on the concept that a compound's biological activity is dependent on its interaction with a specific biological target, mediated through its electrostatic, steric, and hydrophobic properties arranged in three-dimensional space [9]. For breast cancer targets such as aromatase (PDB: 3S7S) or ER-α (PDB: 4XO6), understanding these spatial relationships is crucial for designing effective inhibitors [11] [10]. This application note details the core methodologies of Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), framed within a Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression analysis context for MCF-7 breast cancer research.

Theoretical Foundations of CoMFA and CoMSIA

Molecular Fields and Interaction Energies

CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) operates on the principle that biological activity correlates with interaction energies between a target receptor and probe atoms positioned around the molecules in a dataset [3] [12]. The methodology computes steric fields using a Lennard-Jones potential function and electrostatic fields using a Coulombic potential function [10]. These fields are calculated at regularly spaced grid points surrounding the aligned molecules, creating a data matrix where each row represents a compound and each column represents the interaction energy at a specific grid point.

CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis) extends beyond CoMFA by incorporating additional molecular fields and employing a Gaussian-type distance-dependent function to avoid singularities at molecular surfaces [3] [13]. CoMSIA typically evaluates five similarity indices: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields [11] [10]. The inclusion of hydrophobic and explicit hydrogen bonding fields often makes CoMSIA models more interpretable in medicinal chemistry applications, particularly for breast cancer targets where these interactions play crucial roles in ligand-receptor recognition [10].

Alignment Rules and Molecular Superposition

Molecular alignment constitutes the most critical step in both CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses, as the resulting models are highly sensitive to the relative orientation and conformation of the molecules in the dataset [3] [5]. Several alignment strategies are employed in practice:

- Pharmacophore-based alignment: Uses common chemical features identified from active molecules [5].

- Database alignment: Aligns molecules to a predefined template structure, often the most active compound [3] [10].

- Docking-based alignment: Utilizes binding conformations obtained from molecular docking into the target protein's active site [12].

For MCF-7 inhibitors, the selection of appropriate alignment rules must consider the binding mode to relevant targets such as ER-α or aromatase [3] [10]. A robust alignment should place pharmacophoric features in consistent orientations across all molecules in the dataset.

Comparative Analysis of CoMFA and CoMSIA Descriptors

Table 1: Field Descriptors in CoMFA and CoMSIA Methodologies

| Field Type | CoMFA | CoMSIA | Physical Basis | Role in MCF-7 Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steric | Yes | Yes | Lennard-Jones potential | Optimal bulky groups prevent receptor binding [3] |

| Electrostatic | Yes | Yes | Coulombic potential | Charge complementarity with target [11] |

| Hydrophobic | No | Yes | Hydrophobic interactions | Critical for cell permeability and aromatase binding [10] |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | No | Yes | Donor ability | Targets receptor H-bond acceptors [5] |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | No | Yes | Acceptor ability | Targets receptor H-bond donors [5] |

Statistical Foundation in PLS Regression

Both CoMFA and CoMSIA utilize Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to handle the high-dimensional, collinear field data generated during analysis [12] [9]. PLS reduces the original variables (interaction energies at grid points) to a smaller number of latent variables that maximize the covariance between the molecular fields and biological activity [12]. The optimal number of components is determined through cross-validation, typically using the leave-one-out method, to prevent overfitting and ensure model robustness [3] [10].

The statistical quality of 3D-QSAR models is evaluated using several key parameters:

- Q²: Cross-validated correlation coefficient, indicating predictive ability (should be >0.5 for robust models)

- R²: Non-cross-validated correlation coefficient, measuring model fit (should be >0.8)

- R²pred: External validation correlation coefficient, assessing prediction for test set compounds [3] [10]

Table 2: Representative Statistical Parameters from Recent MCF-7 3D-QSAR Studies

| Compound Class | Method | Q² | R² | R²pred | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine | CoMFA | 0.62 | 0.90 | 0.90 | [3] |

| Tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine | CoMSIA | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.91 | [3] |

| Thioquinazolinone | CoMSIA | 0.669 | 0.989 | 0.936 | [10] |

| Pyrazole-benzimidazole | CoMSIA | N/R | N/R | N/R | [13] |

| 1,4-quinone and quinoline | CoMSIA | N/R | N/R | N/R | [11] |

N/R = Not specifically reported in the search results

Experimental Protocol for 3D-QSAR Model Development

Dataset Preparation and Molecular Modeling

A typical workflow for developing 3D-QSAR models against MCF-7 breast cancer cells involves several methodical steps:

Step 1: Data Collection and Preparation

- Collect a series of compounds with experimentally determined inhibitory activities (IC₅₀ values) against MCF-7 cells [3] [10].

- Convert IC₅₀ values to pIC₅₀ (-logIC₅₀) for use as the dependent variable [3].

- Divide the dataset into training set (typically 70-80% of compounds) for model building and test set (20-30%) for external validation [3] [10].

Step 2: Molecular Structure Optimization

- Sketch molecular structures using modeling software such as SYBYL or Maestro [3] [5].

- Geometry optimization using appropriate force fields (e.g., Tripos force field) with Gasteiger-Hückel partial atomic charges [3] [10].

- Conformational analysis to identify lowest energy conformations or biologically relevant conformers [5].

Step 3: Molecular Alignment

- Select a template molecule, typically the most active compound [3] [10].

- Align all molecules using a consistent rule (pharmacophore-based, database, or docking-based) [5].

- Verify alignment quality through visual inspection and statistical metrics.

Figure 1: 3D-QSAR Model Development Workflow

Field Calculation and PLS Analysis

Step 4: Field Calculation and Data Table Construction

- For CoMFA: Calculate steric and electrostatic fields using a sp³ carbon probe atom with +1 charge on a 2Å grid [3].

- For CoMSIA: Calculate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor fields with attenuation factor of 0.3 [3] [10].

- Construct data table with pIC₅₀ values as dependent variable and field values as independent variables.

Step 5: PLS Regression and Model Validation

- Perform PLS regression with cross-validation to determine optimal number of components [3] [12].

- Validate model using external test set to calculate R²pred [3] [10].

- Assess model robustness through various statistical metrics including standard error of estimate and F-value [10].

Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Resource | Application in 3D-QSAR | Relevance to MCF-7 Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | SYBYL-X (Certara) [3] | Structure building, optimization, CoMFA/CoMSIA | Standard platform for 3D-QSAR development |

| Molecular Modeling | Maestro (Schrödinger) [5] | Pharmacophore modeling, molecular alignment | Phase module for pharmacophore-based alignment |

| Docking Software | AutoDock, GOLD | Binding mode prediction for alignment | Docking-based alignment for protein targets |

| ADMET Prediction | SwissADME, pkCSM | Drug-likeness and toxicity screening | Prioritize compounds with favorable profiles [3] [10] |

| Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER | Molecular dynamics simulations | Validate stability of designed complexes [3] |

Application in Breast Cancer MCF-7 Research: Case Studies

Tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine Derivatives

A recent study demonstrated the successful application of 3D-QSAR for designing tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives as MCF-7 inhibitors [3]. The researchers developed both CoMFA (Q² = 0.62, R² = 0.90) and CoMSIA (Q² = 0.71, R² = 0.88) models with excellent predictive capabilities, confirmed through external validation (R²ext = 0.90 and 0.91 respectively) [3]. The contour maps revealed that:

- Electrostatic fields: Negative charge near specific substituents enhances activity

- Steric fields: Bulky groups at certain positions improve receptor binding

- Hydrophobic fields: Hydrophobic substituents at defined regions increase potency

These insights guided the design of six candidate inhibitors with predicted superior activity, subsequently validated through molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations targeting ER-α (PDB: 4XO6) [3].

Thioquinazolinone Derivatives as Aromatase Inhibitors

Another study focused on thioquinazolinone derivatives as aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer treatment [10]. The optimal CoMSIA model demonstrated strong statistical values (Q² = 0.669, R² = 0.989, R²pred = 0.936), with field contributions of electrostatic (18.8%), hydrophobic (27.3%), hydrogen bond donor (23.8%), and hydrogen bond acceptor (30.1%) [10]. The contour maps provided specific guidance for molecular modifications:

- Hydrogen bond acceptors: Near specific ring positions crucial for activity

- Hydrophobic groups: At defined molecular regions enhance binding

- Electrostatic properties: Positive potential near substituents improves potency

The study designed new compounds based on these insights and verified their binding modes through molecular docking with aromatase (PDB: 3S7S) [10].

Figure 2: Drug Design Workflow Using 3D-QSAR Results

Advanced Applications and Integration with Other Methods

Multi-Method Validation Approaches

Contemporary 3D-QSAR studies for breast cancer research increasingly integrate multiple computational and experimental approaches to validate findings:

- Molecular Docking: Verifies binding modes suggested by 3D-QSAR contours and identifies key protein-ligand interactions [3] [10].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Assesses complex stability over time (typically 100 ns) and calculates binding free energies using MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA methods [3] [13].

- ADMET Predictions: Evaluates drug-likeness, pharmacokinetic properties, and potential toxicity of designed compounds before synthesis [3] [10].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Free Energy Landscape (FEL): Provides additional insights into molecular stability and conformational space [13].

This integrated approach ensures that compounds designed using 3D-QSAR guidance not only exhibit predicted high activity but also possess favorable drug-like properties and binding stability, accelerating the discovery of effective MCF-7 inhibitors for breast cancer treatment [3] [13] [10].

Why PLS Regression is the Gold Standard for 3D-QSAR Model Development

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression stands as the cornerstone statistical method for developing robust three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) models in drug discovery. This protocol details the application of PLS regression within 3D-QSAR frameworks, specifically contextualized for breast cancer research utilizing MCF-7 cell line assays. We provide comprehensive methodologies for building, validating, and interpreting CoMFA and CoMSIA models, including detailed workflows for molecular alignment, descriptor calculation, and model validation. The documented protocols leverage proven applications in designing latrunculin-based actin inhibitors and aromatase-targeting compounds, providing researchers with standardized procedures for implementing this powerful analytical approach in their anti-breast cancer drug development campaigns.

In the field of computer-aided drug design, 3D-QSAR methodologies have emerged as essential tools for correlating the three-dimensional structural properties of compounds with their biological activity. Unlike traditional 2D-QSAR that utilizes molecular descriptors invariant to conformation, 3D-QSAR incorporates spatial and electrostatic properties, providing superior insights into structure-activity relationships [14]. The Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) represent the most widely adopted 3D-QSAR approaches, generating thousands of highly correlated descriptors from molecular interaction fields [15].

PLS regression serves as the fundamental statistical engine for analyzing these complex descriptor matrices. As a variation of principal component regression, PLS projects the original variables into a smaller set of latent variables that maximize the covariance between predictor and response blocks [12]. This capability makes PLS uniquely suited for 3D-QSAR applications where the number of independent variables (grid points) significantly exceeds the number of observations (compounds) and where substantial multicollinearity exists among descriptors [12] [16]. The robustness of PLS in handling such challenging datasets has established it as the gold standard for 3D-QSAR model development across diverse therapeutic areas, including breast cancer research targeting MCF-7 proliferation pathways.

Theoretical Foundations and Advantages of PLS

Mathematical Principles of PLS Regression

PLS regression operates by simultaneously projecting the variable matrix X (3D-field descriptors) and the response vector Y (biological activities) to new coordinates, maximizing the explained variance in both spaces. The algorithm identifies linear combinations of the original variables (latent variables or components) that successively maximize the covariance between X and Y. This approach differs fundamentally from principal component analysis (PCA), which only considers the variance in the X-space without regard to the response variable [16].

The PLS model can be represented as: X = TP′ + E and Y = UQ′ + F where T and U are the score matrices for X and Y, P and Q are the loading matrices, and E and F are the error terms. The inner relationship between the score vectors is established through U = TD + H, where D is a diagonal matrix and H represents the residuals [16].

Comparative Advantages for 3D-QSAR

Table 1: Key Advantages of PLS Regression in 3D-QSAR

| Advantage | Technical Rationale | Impact on Model Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Handling Multidimensional Descriptors | Capable of analyzing datasets where variables >> samples (e.g., thousands of grid points vs. dozens of compounds) [12] | Enables comprehensive 3D-field analysis without dimensionality reduction |

| Managing Correlated Variables | Effectively handles inter-descriptor correlations inherent in CoMFA/CoMSIA grids [12] | Prevents instability in coefficient estimates |

| Reducing Overfitting Risk | Latent variable selection based on cross-validation minimizes chance correlations [12] [16] | Enhances model predictivity for new chemical entities |

| Integration with Cross-Validation | Compatible with leave-one-out (LOO) and leave-multiple-out (LMO) validation techniques | Provides robust q² metrics for model selection |

The theoretical superiority of PLS for 3D-QSAR was demonstrated in a study of latrunculin-based actin inhibitors, where models developed with PLS regression achieved exceptional statistical quality (q² = 0.621-0.659, r² = 0.938-0.965) [12]. These models successfully predicted the antiproliferative activities against MCF-7 breast cancer cells for an external test set of five compounds, validating the practical utility of the PLS approach.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Comprehensive Workflow for 3D-QSAR with PLS

The following diagram illustrates the standardized workflow for developing validated 3D-QSAR models using PLS regression:

Data Collection and Preparation Protocol

Objective: Assemble a structurally diverse dataset with consistent biological activity data.

- Compound Selection: Curate 20-50 congeneric compounds with measured IC₅₀ values against MCF-7 breast cancer cells [12] [17]. Ensure structural diversity while maintaining a common scaffold to assume similar binding modes.

- Activity Data: Express biological activity as pIC₅₀ (-logIC₅₀) to create a linearly correlated response variable [12]. All activity data should be generated under uniform experimental conditions (e.g., consistent assay protocols, incubation times, and passage numbers for MCF-7 cells).

- Training/Test Sets: Apply Kennard-Stone algorithm or similar approach to divide compounds into training (70-80%) and external test sets (20-30%) [16] [17].

Molecular Modeling and Alignment Protocol

Objective: Generate bioactive conformations and align molecules in 3D space.

- 3D Structure Generation: Convert 2D structures to 3D coordinates using cheminformatics tools (RDKit, OpenBabel) [14].

- Conformation Optimization: Perform geometry optimization using molecular mechanics (UFF, MMFF94s) or semi-empirical quantum mechanical methods (AM1, PM3) [14].

- Molecular Alignment:

- Pharmacophore-Based: For targets with known active site structure (e.g., aromatase in breast cancer), use docking-derived poses from software like AutoDock Vina or GOLD [18] [17].

- Ligand-Based: For targets with unknown structure, employ maximum common substructure (MCS) or field-based alignment methods [14].

- Reference Compound: Select the most active compound or one with confirmed bioactive conformation as alignment template [17].

3D Descriptor Calculation and PLS Implementation

Objective: Calculate molecular interaction fields and build PLS regression models.

- CoMFA Field Calculation:

- CoMSIA Field Calculation:

- Implement same grid parameters as CoMFA

- Calculate similarity indices for steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor fields using Gaussian-type distance functions [14]

- PLS Regression Implementation:

- Data Preprocessing: Apply block-scaling to balance steric/electrostatic field contributions and column-wise standardization (unit variance) [14]

- Component Selection: Determine optimal number of latent variables through leave-one-out cross-validation, selecting components where q² is maximized [12]

- Model Fitting: Develop final model using optimal components on entire training set without cross-validation [12]

Model Validation Protocol

Objective: Establish statistical robustness and predictive power of 3D-QSAR models.

- Internal Validation:

- Calculate cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) using leave-one-out procedure

- Acceptable threshold: q² > 0.5 for predictive models [16]

- Compute non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (r²) and standard error of estimate

- External Validation:

- Robustness Assessment:

Table 2: Statistical Benchmarks for Validated 3D-QSAR Models

| Statistical Parameter | Acceptable Threshold | Excellent Performance | Application in MCF-7 Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| q² (LOO cross-validation) | > 0.5 | > 0.6 | Latrunculin study: q² = 0.621-0.659 [12] |

| r² (non-cross-validated) | > 0.8 | > 0.9 | Latrunculin study: r² = 0.938-0.965 [12] |

| Standard Error of Estimate | Minimized relative to activity range | < 0.3 log units | Critical for predicting antiproliferative potency |

| r²pred (external test set) | > 0.6 | > 0.7 | Successfully predicted 5 external compounds [12] |

| Components | Avoid overfitting | Optimal q² plateau | Typically 4-7 components for CoMFA/CoMSIA |

Research Reagent Solutions for MCF-7 3D-QSAR

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines & Assays | MCF-7 (HTB-22) human breast adenocarcinoma cells [12] [19] | Standardized cellular model for determining antiproliferative IC₅₀ values |

| Biological Assays | MTT proliferation assay [12] | Quantification of cell viability and compound cytotoxicity |

| Computational Chemistry | SYBYL [12], Open3DQSAR [18] | Commercial and open-source platforms for CoMFA/CoMSIA analysis |

| Molecular Modeling | RDKit [14], AutoDock Vina [17] | 3D structure generation, optimization, and docking studies |

| Statistical Analysis | PLS implementation in SYBYL [12], scikit-learn (Python) | Core regression algorithm for model development |

| Chemical Libraries | Thiosemicarbazone, 1,2,4-triazole derivatives [17] | Structurally diverse compounds for building robust QSAR models |

Application in Breast Cancer MCF-7 Research

The integration of PLS-based 3D-QSAR models has demonstrated significant impact in anti-breast cancer drug discovery. In a seminal study investigating latrunculin-based actin inhibitors, researchers developed CoMFA and CoMSIA models using PLS regression that accurately predicted antiproliferative activities against MCF-7 cells [12]. The models successfully guided structural optimization by identifying critical steric and electrostatic features contributing to potency, particularly the importance of the C-17 lactol hydroxyl group for interacting with arginine 210 in actin [12].

More recently, PLS-driven 3D-QSAR approaches have been applied to aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer treatment, with studies incorporating both ligand-based and structure-based design elements [17]. These models successfully correlated structural features of thiosemicarbazone and triazole derivatives with aromatase inhibition, providing visual contour maps that guided the design of novel compounds with predicted enhanced activity [17]. The robust statistical foundation provided by PLS regression enabled researchers to confidently prioritize synthetic targets for experimental validation.

Advanced Implementation Strategies

Integration with Docking Studies

Combining 3D-QSAR with molecular docking creates a powerful synergistic approach for drug design. The docking poses provide biologically relevant alignment rules based on protein-ligand interactions, while 3D-QSAR contour maps interpret the resulting models in chemical terms [18] [17]. This combined methodology was successfully applied in designing TRPV1 channel antagonists, where docking into the cryo-EM structure (PDB: 8GFA) provided the alignment for subsequent CoMFA analysis [18].

Handling Alignment-Sensitive Scenarios

Molecular alignment remains the most critical step in traditional CoMFA implementations. When dealing with structurally diverse datasets, consider these advanced approaches:

- Docking-Based Alignment: Use consensus docking poses from multiple algorithms to establish alignment rules [17]

- Field-Based Alignment: Implement field-fit techniques that optimize superposition based on similarity of molecular fields rather than atom positions [14]

- Multiple Conformation Approaches: Incorporate several low-energy conformations per compound to account for flexibility [18]

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Issue: Low q² despite high r²

- Potential Cause: Overfitting due to excessive latent variables

- Solution: Re-evaluate optimal component number using cross-validation; consider bootstrapping for more robust component selection

Issue: Poor external prediction accuracy

- Potential Cause: Test compounds outside applicability domain of training set

- Solution: Implement applicability domain assessment using leverage and standardization approaches; expand structural diversity of training set

Issue: Inconsistent contour map interpretation

- Potential Cause: Suboptimal alignment of molecules with divergent binding modes

- Solution: Validate alignment strategy with known crystal structures or through docking studies; consider receptor-based alignment when protein structure available

PLS regression has firmly established itself as the statistical foundation for 3D-QSAR model development due to its unique ability to handle the high-dimensional, multicollinear datasets generated by CoMFA and CoMSIA methodologies. The protocols outlined in this document provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing PLS-based 3D-QSAR in breast cancer drug discovery, with specific application to MCF-7 targeted therapies. Through proper implementation of alignment strategies, descriptor calculation, and validation protocols, researchers can develop robust predictive models that significantly accelerate the design and optimization of novel anti-breast cancer agents. The continued integration of these approaches with structural biology and machine learning techniques promises to further enhance their predictive power and utility in drug development campaigns.

In the field of computational drug design, particularly in the development of therapeutics for breast cancer, Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression serves as the statistical backbone for Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) models. These models connect the molecular features of compounds to their biological activity against specific targets, such as the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. The reliability of these models is paramount, as they guide the synthesis and testing of new drug candidates. Evaluating this reliability hinges on understanding key statistical metrics: the coefficient of determination (R²) for explanatory power and the predictive squared correlation coefficient (Q²) for predictive capability. A robust 3D-QSAR model must demonstrate high values for both R² and Q², indicating it not only fits the training data well but can also accurately predict the activity of novel compounds, thereby accelerating the discovery of effective anti-cancer agents [20] [3].

Core Statistical Metrics: Definitions and Interpretations

The Coefficient of Determination (R²)

R², or the coefficient of determination, is a fundamental metric that quantifies the goodness-of-fit of a regression model. It measures the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable (e.g., biological activity pIC₅₀) that is predictable from the independent variables (e.g., 3D molecular field descriptors) [21] [22].

Mathematical Definition: R² is calculated as 1 minus the ratio of the residual sum of squares (RSS) to the total sum of squares (TSS). ( R^2 = 1 - \frac{RSS}{TSS} = 1 - \frac{\sum(yi - \hat{y}i)^2}{\sum(yi - \bar{y})^2} ) Where ( yi ) is the observed value, ( \hat{y}_i ) is the predicted value, and ( \bar{y} ) is the mean of observed values [20] [22].

Interpretation: R² values range from 0 to 1. An R² of 1 indicates the model explains all the variability of the response data around its mean, while an R² of 0 indicates the model explains none of the variability. In 3D-QSAR studies for MCF-7, a high R² signifies that the molecular descriptors effectively capture the structural features responsible for biological activity [23] [21].

The Predictive Squared Correlation Coefficient (Q²)

Q², often referred to as the goodness of prediction, is a metric derived from cross-validation that assesses the predictive power of a model on new, unseen data [20].

Mathematical Definition: Q² is calculated as 1 minus the ratio of the predictive residual sum of squares (PRESS) to the total sum of squares (TSS). ( Q^2 = 1 - \frac{PRESS}{TSS} = 1 - \frac{\sum(yi - \hat{y}{i, PRESS})^2}{\sum(yi - \bar{y})^2} ) Where ( \hat{y}{i, PRESS} ) is the predicted value for the i-th observation when the model is built without it (as in Leave-One-Out cross-validation) [20].

Interpretation: Like R², Q² ranges from 0 to 1, though it can be negative if the model predictions are worse than simply using the mean activity. A high Q² value is critical in 3D-QSAR, as it confirms the model's utility in predicting the activity of newly designed compounds before they are synthesized and tested biologically [20] [3].

Comparative Analysis of R² and Q²

The critical distinction between R² and Q² lies in their evaluation of model performance: R² measures fit to existing data, while Q² measures prediction of new data [20]. In practice, a model's R² is always higher than its Q². A large gap between R² and Q² often indicates overfitting, where the model is too complex and describes noise in the training data rather than the underlying relationship. A robust and predictive model is characterized by high values for both R² and Q², with the difference between them being minimal [20] [24].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of R² and Q² in PLS-based 3D-QSAR

| Metric | Evaluates | Calculation Basis | Interpretation in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² (Goodness-of-Fit) | Model's fit to training data | Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) | How well the model explains the activity of the training set compounds. |

| Q² (Goodness-of-Prediction) | Model's predictive ability | Predictive Residual Sum of Squares (PRESS) | How well the model predicts the activity of a external test set or new compounds. |

Application in Breast Cancer MCF-7 Research: A Quantitative Review

The application of R² and Q² in validating 3D-QSAR models for MCF-7 breast cancer research is well-documented in recent literature. The following table summarizes quantitative data from key studies, demonstrating the role of these metrics in practice.

Table 2: Summary of R² and Q² Values from Recent 3D-QSAR Studies on MCF-7 Inhibitors

| Study Compound / Class | Model Type | R² (Training) | Q² (Validation) | External Validation (R²pred) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives | CoMFA | 0.90 | 0.62 | 0.90 | [3] |

| Tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives | CoMSIA | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.91 | [3] |

| Maslinic acid analogs | PLS Regression | 0.92 | 0.75 | Not Specified | [24] [25] |

| Thioquinazolinone derivatives | CoMSIA | Significant values reported | Significant values reported | Significant ( R^2_{pred} ) reported | [10] |

Interpretation of Case Studies:

- The studies on tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives showcase robust and predictive models. The CoMSIA model, for instance, with an R² of 0.88 and a Q² of 0.71, demonstrates a strong balance between explanation and prediction. The high external validation correlation coefficient (R²pred of 0.91) further confirms the model's utility for screening new potential inhibitors [3].

- The Maslinic acid analogs study presents a high R² (0.92) and a strong Q² (0.75), indicating an excellent model. This LOO-validated PLS model was successfully used to screen a large compound library, leading to the identification of a best hit, compound P-902, for further investigation [24] [25].

- These examples underscore that a Q² value above 0.5 is generally considered indicative of a predictive model in chemometrics and QSAR studies, while R² values above 0.8 or 0.9 reflect a strong explanatory model [3] [24].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol 1: Standard Procedure for PLS-based 3D-QSAR Model Development and Validation

This protocol outlines the key steps for building and validating a 3D-QSAR model using PLS regression, ensuring reliable R² and Q² metrics.

Dataset Preparation and Curation

- Activity Data: Collect experimental biological data (e.g., IC₅₀) for a series of compounds against the MCF-7 cell line. Convert IC₅₀ values to pIC₅₀ (pIC₅₀ = -logIC₅₀) for use as the dependent variable [3].

- Data Splitting: Randomly divide the dataset into a training set (typically ~80%) for model building and a test set (the remaining ~20%) for external validation. The test set must be kept blind during model development [3] [10].

Molecular Modeling and Alignment

- Structure Construction: Sketch or build the 3D structures of all compounds using molecular modeling software (e.g., SYBYL-X) [3] [10].

- Geometry Optimization: Minimize the energy of each molecule using a specified force field (e.g., Tripos force field) and assign partial atomic charges (e.g., Gasteiger-Hückel) [3].

- Molecular Alignment: Align all molecules onto a common template, typically the most active or a hypothesized most rigid molecule, using a method like the

distillmodule in SYBYL. This is a critical step for the meaningful calculation of 3D descriptors [3] [10].

Descriptor Calculation and PLS Regression

- Field Calculation: Calculate 3D molecular field descriptors. For CoMFA, compute steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields. For CoMSIA, additional fields like hydrophobic, hydrogen-bond donor, and acceptor may be used [3] [10].

- Model Building: Subject the field descriptors to PLS regression to derive the QSAR model, relating the molecular fields to the biological activity (pIC₅₀).

Internal Validation and Q² Calculation

- Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation: Systematically remove one compound from the training set, build the model with the remaining compounds, and predict the activity of the removed compound. Repeat for every compound in the training set [24].

- Calculate Q²: Compute PRESS from the prediction errors during LOO and then calculate Q² using the formula in Section 2.2 [20] [24].

External Validation and Model Application

- Predict Test Set: Use the final model, built on the entire training set, to predict the activities of the blinded test set compounds.

- Calculate R²pred: Calculate the predictive R² (R²pred) for the test set to externally validate the model's power [3] [10].

- Design New Compounds: Utilize the model's contour maps to guide the design of new compounds with predicted high activity. Synthesize and test these compounds to experimentally validate the model's predictions [3].

Protocol 2: Statistical Significance Testing for R² and Q²

This protocol ensures the statistical robustness of the reported metrics.

- Permutation Testing: To confirm the model is not based on chance correlation, repeat the model building process multiple times (e.g., 100 times) with randomly shuffled activity data (Y-scrambling). The R² and Q² of the true model should be significantly higher than those from the scrambled models [10].

- Assessment of Difference (R² - Q²): A small difference (e.g., < 0.3) between R² and Q² generally indicates a robust model without severe overfitting. A larger gap warrants investigation into model complexity or data overfitting [20] [24].

- Bootstrapping: Perform bootstrapping analysis (repeated sampling with replacement from the training set) to estimate the confidence intervals for the PLS regression coefficients and the R²/Q² metrics, providing a measure of their stability [22].

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for 3D-QSAR model development and validation, highlighting the roles of R² and Q² at key stages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevance to R²/Q² |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL-X Software | A comprehensive molecular modeling environment used for structure building, energy minimization, molecular alignment, and CoMFA/CoMSIA analysis. | Provides the platform for generating the PLS regression models and automatically calculates R² and Q² during analysis [3] [10]. |

| Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation Algorithm | A resampling procedure used to estimate the predictive performance of a model. | This algorithm is the standard method for generating the PRESS statistic, which is required for the calculation of Q² [20] [24]. |

| Training and Test Sets | A curated dataset of compounds with known biological activity, split into subsets for model building and validation. | The training set is used to calculate R². The test set is held back for external validation, providing the final, most rigorous test of predictive power (R²pred) [3] [10]. |

| PLS Regression Algorithm | A statistical method that projects predicted variables and observable variables to a new space, ideal for handling correlated descriptors in QSAR. | The core algorithm that establishes the relationship between molecular structures and activity. It directly generates the model statistics, including R² [20] [26]. |

This application note details a computational protocol for developing and validating a three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) model. The model is designed to predict the anticancer activity of tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives against the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. The workflow integrates Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) with Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to elucidate critical structural features governing biological activity. This provides a rational basis for designing novel, potent inhibitors [3] [27].

Breast cancer, particularly the MCF-7 cell line, represents a major focus in oncology research. The tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffold has been identified as a promising core structure due to its diverse biological activities, including significant antitumor properties. This scaffold is a bioisostere of quinazoline and has been used as a central framework in developing compounds that potentially inhibit cancer cell proliferation [3].

The primary objective of this case study is to establish a predictive 3D-QSAR model. This model links the three-dimensional molecular properties of a series of derivatives to their half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) against MCF-7 cells. The resulting model serves as a valuable tool for in silico screening and optimization of new candidate molecules before costly synthetic and biological testing [3].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

Dataset Curation and Preparation

- Data Source: A dataset of 29 tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives with known experimental IC₅₀ values against the MCF-7 cell line was compiled from published literature [3].

- Activity Conversion: IC₅₀ values (in molar units) were converted to pIC₅₀ using the formula pIC₅₀ = -log(IC₅₀), which serves as the dependent variable in the QSAR model [3].

- Dataset Division: The dataset was randomly partitioned into a training set (24 compounds) for model development and a test set (5 compounds) for external validation of the model's predictive power [3].

- Structure Preparation: All molecular structures were sketched in 2D and converted into 3D models. Energy minimization was performed using the Tripos force field with Gasteiger-Hückel partial atomic charges in SYBYL-X.2.1 software to obtain stable, low-energy conformations [3].

Molecular Alignment

Molecular alignment is a critical step in 3D-QSAR. The most active compound in the series (3z, pIC₅₀ = 7.0) was selected as the template structure. All other molecules in the dataset were aligned to this template based on their common core structure using the "distill" module in SYBYL 2.1 software to ensure a consistent frame of reference for field calculations [3].

3D-QSAR Model Development and PLS Regression

- Descriptor Calculation: The aligned molecules were placed within a 3D grid. The CoMFA and CoMSIA fields were calculated at each grid point.

- PLS Regression Analysis: The relationship between the calculated molecular field descriptors (independent variables) and the pIC₅₀ values (dependent variable) was modeled using the Partial Least Squares (PLS) algorithm. This technique is ideal for handling data where the number of variables exceeds the number of observations and where variables are highly correlated [3] [4]. The model's complexity (number of latent variables) was optimized to avoid overfitting.

Model Validation

The robustness and predictive ability of the 3D-QSAR models were rigorously assessed using the following methods [3]:

- Internal Validation: Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation was performed on the training set, yielding cross-validated correlation coefficients (Q²).

- External Validation: The model's predictive power was tested by predicting the activity of the five compounds in the external test set that were not used in model building.

- Statistical Metrics: The quality of the model was evaluated using the non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (R²) and standard error of estimate.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of the 3D-QSAR modeling process.

Key Results and Model Statistics

The established 3D-QSAR models demonstrated high statistical quality and robust predictive ability, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Statistical Parameters of the Developed 3D-QSAR Models [3]

| Model | Cross-Validated Correlation Coefficient (Q²) | Non-Cross-Validated Correlation Coefficient (R²) | Number of Components | Standard Error of Estimate | External Validation Correlation (R²ext) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | 0.62 | 0.90 | 6 | 0.28 | 0.90 |

| CoMSIA | 0.71 | 0.88 | 6 | 0.31 | 0.91 |

The contour maps generated from the models provide visual guidance for molecular design. For example:

- CoMFA Steric Fields: Green contours near a specific substituent position indicate regions where bulky groups enhance activity, while yellow contours show where bulky groups are detrimental.

- CoMFA Electrostatic Fields: Blue contours indicate regions where electropositive groups are favorable, whereas red contours show where electronegative groups boost activity [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR

| Item Name / Software | Function in the Protocol | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL-X | Integrated software suite for molecular modeling, structure building, alignment, and 3D-QSAR analysis. | Used for energy minimization (Tripos force field), molecular alignment (distill module), and CoMFA/CoMSIA calculations [3]. |

| PLS Regression | Core statistical algorithm used to correlate 3D molecular field descriptors with biological activity. | Implemented within SYBYL; optimal number of components is critical to avoid model overfitting [3] [4]. |

| Tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine core | The central chemical scaffold upon which derivatives are designed and synthesized. | Acts as a bioisostere for quinazoline; known for antitumor, antimicrobial, and antiviral activities [3]. |

| MCF-7 Cell Line Assay | In vitro biological assay to determine the potency (IC₅₀) of compounds against breast cancer. | Provides the experimental activity data (pIC₅₀) used as the dependent variable for building the QSAR model [3]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation | Advanced simulation technique to study the stability and dynamics of protein-ligand complexes over time. | Used in subsequent studies (e.g., 100 ns simulations) to validate docking poses and binding stability [3] [28]. |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | In silico software to predict Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity. | Used to evaluate the drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic properties of newly designed compounds before synthesis [3] [4]. |

Advanced Applications and Protocol Extension

The validated 3D-QSAR model is not an endpoint but a starting point for a more comprehensive drug discovery campaign.

Virtual Screening and Molecular Design

The model can be used to screen virtual libraries of compounds by predicting their pIC₅₀ values. Furthermore, the 3D contour maps provide a clear guide for rational drug design:

- To increase potency, introduce substituents that match the favorable steric (green) and electrostatic (blue/red) regions indicated by the model.

- To avoid reducing potency, eliminate groups that fall into unfavorable (yellow) regions [3].

Integration with Molecular Docking

To understand the binding mode of these derivatives, molecular docking was performed against the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) crystal structure (PDB code: 4XO6). Docking studies help visualize key interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts, between the ligand and the active site of the protein, providing a structural basis for the observed activity [3].

Binding Stability Assessment using MM/GBSA and MD

The binding affinities predicted by docking can be refined using the Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) method to calculate binding free energies. Subsequently, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., for 100 ns) can be run to assess the stability of the protein-ligand complex under dynamic, physiological-like conditions and to confirm that the binding pose is maintained over time [3] [28].

The relationship between these advanced techniques is summarized in the following workflow.

A Step-by-Step Workflow: Building and Applying Your 3D-QSAR Model with PLS

The development of robust 3D-QSAR models for breast cancer MCF-7 research hinges critically on two preliminary computational procedures: rigorous dataset curation and precise molecular alignment. These foundational steps determine the quality of the molecular descriptors fed into Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression analysis, ultimately governing the predictive power and reliability of the resulting models [9] [17]. In the context of anti-breast cancer drug discovery, these protocols ensure that computational predictions regarding compound activity against MCF-7 cell lines translate effectively to experimental validation, thereby accelerating the identification of promising therapeutic candidates [29].

Dataset Curation Protocol

Data Collection and Standardization

The initial phase involves assembling a structurally diverse yet mechanistically consistent set of compounds with experimentally determined activities against MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines.

- Data Sourcing: Retrieve biological activity data (typically IC50 values) from reliable public databases such as the NPACT database , which specializes in naturally occurring plant-derived anticancer compounds with associated cell line activities [29]. The MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line is frequently used as a model system in such studies [29].

- Activity Value Standardization: Convert concentration values (e.g., IC50 in µM) to a uniform negative logarithmic scale (pIC50) using the formula: pIC50 = -log10(IC50 × 10⁻⁶) [30]. This transformation linearizes the relationship between concentration and biological response for subsequent PLS regression analysis.

- Structure Standardization: Curate and standardize all molecular structures by:

Data Pretreatment and Division

- Descriptor Calculation and Filtering: Calculate molecular descriptors using software such as PaDEL Descriptor. Subsequently, preprocess the generated descriptor matrix to remove constants and near-constant values, reducing noise and computational burden [30].

- Dataset Division: Partition the curated dataset into training and test sets using algorithms such as the Kennard-Stone method. This approach ensures the training set spans the entire chemical space of the dataset, while the test set provides a robust external validation cohort [30]. A typical split allocates approximately 70-80% of compounds for training and 20-30% for testing [29] [30].

Table 1: Key Validation Parameters for Robust QSAR Models

| Parameter | Category | Acceptance Threshold | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² | Internal Validation | > 0.6 | Measures goodness-of-fit of the model [29]. |

| Q²loo | Internal Validation | > 0.5 | Evaluates model robustness via leave-one-out cross-validation [29]. |

| R²pred | External Validation | > 0.5 | Assesses predictive power on an external test set [30]. |

| CCC | External Validation | > 0.8 | Concordance Correlation Coefficient; measures agreement between observed and predicted values [29]. |

The following workflow outlines the complete dataset curation and model building process, highlighting the initial critical steps.

Molecular Alignment Strategies

Molecular alignment, the process of superimposing molecules in 3D space based on a common reference framework, is a critical step for 3D-QSAR techniques like CoMFA and CoMSIA. The chosen strategy directly influences the contour maps and the subsequent interpretation of structural features affecting activity [11] [17].

Common Alignment Methodologies

- Pharmacophore-Based Alignment: This method aligns molecules based on common pharmacophoric features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings) believed to be essential for interaction with the biological target [9].

- Database Alignment: A common practice involves using a pre-defined template or a selected active molecule from the dataset as a reference for alignment. For instance, a high-activity compound (e.g., "molecule 4" in one study) is chosen, and all other structures are aligned onto its scaffold to ensure consistency [17].

- Ligand-Based Alignment (Common Substructure): Molecules are superimposed based on a shared common substructure or scaffold. This is particularly effective for congeneric series of derivatives, such as thiosemicarbazone or imidazol-5-ones, where a core structure is maintained [17] [30].

Practical Alignment Protocol

- Template Selection: Identify and energy-minimize the most active compound or a representative template molecule from the dataset using computational methods (e.g., Density Functional Theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-31G* level is commonly used for geometric optimization) [30].

- Structural Preparation: Prepare all molecules in the dataset by generating low-energy 3D conformations. It is crucial to consider the biologically active conformation if known.

- Superimposition: Align all molecules onto the selected template based on the chosen strategy (common substructure or pharmacophore points). Software like Spartan or functionality within 3D-QSAR packages (e.g., SYBYL) is typically used for this step [11] [30].

- Validation: Visually inspect the alignment to ensure meaningful overlap of critical functional groups. A poor alignment will lead to statistically insignificant or uninterpretable 3D-QSAR models.

The alignment process establishes the common frame of reference necessary for extracting comparative molecular field descriptors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Dataset Curation and Molecular Alignment

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| NPACT Database | Database | Source of curated natural products with anti-MCF-7 activity data [29]. |

| PubChem/ChemSpider | Database | Repositories for retrieving standardized molecular structures [29]. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Descriptor Calculator | Calculates molecular descriptors from chemical structures for QSAR [29] [30]. |

| Spartan | Molecular Modeling | Used for quantum mechanical geometry optimization of molecules prior to alignment and descriptor calculation [30]. |

| ChemDraw | Chemical Drawing | Creates and converts 2D chemical structures to 3D formats for further processing [30]. |

| SYBYL (CoMFA/CoMSIA) | 3D-QSAR Platform | Performs molecular alignment, field calculation, and PLS regression analysis to build the 3D-QSAR models [11] [17]. |

| Data Pre-treatment GUI | Data Preprocessing | Removes constant and redundant descriptors to improve model quality and stability [30]. |

In modern computer-aided drug design (CADD), the ability to quantify and model the three-dimensional interactions between a potential drug molecule and its biological target is paramount [31]. Molecular field descriptors are computational representations that numerically capture key aspects of a molecule's shape and interaction potential, providing a cornerstone for Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) studies [14]. These methodologies are particularly vital in targeted cancer therapy research, such as in the discovery of novel anti-proliferative agents against the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line [13] [4]. By correlating these calculated molecular fields with experimentally determined biological activity, researchers can build predictive models that guide the rational design of more potent and selective drug candidates. This application note details the protocols for calculating steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic field descriptors and their subsequent processing via Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression analysis, framing the discussion within the critical context of breast cancer drug discovery.

Molecular Field Descriptors: Core Concepts and Calculations

Molecular field descriptors map a molecule's spatial interaction properties by probing its 3D structure. The table below summarizes the three primary fields used in 3D-QSAR.

Table 1: Core Molecular Field Descriptors in 3D-QSAR

| Field Type | Physical Significance | Probe Atom/Group | Representation in Contour Maps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steric | Molecular bulk and van der Waals repulsion/attraction [32] [14]. | sp³ Carbon atom [33] [14]. | Green: Favorable bulky groupsYellow: Unfavorable bulky groups [14]. |

| Electrostatic | Local positive or negative electrostatic potential [32] [14]. | Charged atom (e.g., H⁺ with +1 charge) [33] [14]. | Blue: Favorable positive chargeRed: Favorable negative charge [14]. |

| Hydrophobic | Propensity for hydrophobic interactions [14] [4]. | Hypothetical hydrophobic probe [14]. | Yellow: Favorable hydrophobic groupsWhite: Unfavorable hydrophobic groups. |

These descriptors form the basis of established 3D-QSAR methodologies like Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) [33] [14]. While CoMFA classically calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) potentials on a 3D lattice, CoMSIA extends this by using Gaussian-type functions to evaluate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields, which often produces more interpretable models and is less sensitive to minor molecular misalignments [14].

Experimental Protocol: Calculation Workflow

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for calculating molecular field descriptors and building a 3D-QSAR model with PLS regression, contextualized for a study on MCF-7 breast cancer cell inhibitors [13] [4].

Data Collection and Preparation

- Activity Data: Assemble a congeneric series of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀ or MIC values) against the MCF-7 cell line [14] [4]. All data must be acquired under uniform experimental conditions to minimize noise and bias.

- Dataset Division: Divide the dataset into a training set (typically ~80%) for model construction and a test set (typically ~20%) for external validation of the model's predictive power [33] [4].

- Structure Preparation: Convert 2D molecular structures into 3D formats using cheminformatics tools like ChemBio3D [4] or RDKit [14]. Geometry-optimize the 3D structures using molecular mechanics (e.g., Tripos force field, UFF) or quantum mechanical methods to achieve a realistic, low-energy conformation [33] [14].

Molecular Alignment

Molecular alignment is a critical step that assumes all compounds share a similar binding mode to the target.

- Method Selection: Use a common substructure for rigid alignment or a flexible alignment algorithm [14] [34].

- Protocol: In software such as SYBYL-X or Forge, align all molecules onto a chosen template, often the most active compound in the series, based on their maximum common substructure (MCS) or a pre-defined pharmacophore [14] [34]. This ensures all molecules are placed in a common 3D coordinate system.

Field Descriptor Calculation

With aligned molecules, calculate the field descriptors within a defined 3D grid that encompasses all molecules.

- Grid Setup: Create a 3D grid with a spacing of 1.0 or 2.0 Å extending beyond the dimensions of all aligned molecules [33].

- Descriptor Generation:

- For CoMFA: At each grid point, calculate steric (Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (Coulomb potential) interaction energies using a probe atom [33] [14].

- For CoMSIA: Calculate similarity indices for steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields using a Gaussian function at each grid point [14]. A sp³ carbon atom with a +1 charge is a typical probe [33].

- Energy Truncation: Set reasonable cutoffs (e.g., 30 kcal/mol) for steric and electrostatic energies to prevent singularities and improve model stability [33].

The workflow from data preparation to model building is visualized in the following diagram.

Model Building with PLS Regression

The generated field descriptors serve as the independent variables (X-matrix), while the biological activity (e.g., pIC₅₀ = -logIC₅₀) is the dependent variable (Y-matrix) [33] [4].

- Rationale for PLS: PLS regression is the standard method for 3D-QSAR as it effectively handles the high dimensionality and multicollinearity inherent in the descriptor matrix (where the number of grid points far exceeds the number of compounds) [35] [14].

- Protocol Execution:

- Software: Use the PLS module in 3D-QSAR software like SYBYL-X [33] or Forge [4].

- Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation: Perform LOO cross-validation on the training set to determine the optimal number of latent variables (also called principal components) that maximizes the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) and minimizes overfitting [33] [4]. A Q² > 0.5 is generally considered acceptable [33].

- Final Model Construction: Using the optimal number of components, build the final PLS model on the entire training set to obtain the conventional correlation coefficient (R²) and standard error of estimate (SEE) [33].

Model Validation and Interpretation

- Validation: Assess the model's predictive power by predicting the activity of the external test set. A predictive correlation coefficient (R²ₚᵣₑ𝒹) greater than 0.6 indicates a robust model [33].

- Interpretation via Contour Maps: The PLS model coefficients are visualized as 3D contour maps around a reference molecule [14]. These maps highlight regions where specific molecular fields are favorably or unfavorably linked with biological activity, providing clear, visual guidance for medicinal chemists to design improved analogs [14] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function / Application in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Software Suites | SYBYL-X [33], Forge (Cresset) [4], Discovery Studio [34] | Integrated platforms for molecular modeling, alignment, field calculation, and PLS analysis. |

| Cheminformatics Libraries | RDKit [14], ChemBio3D [4] | Open-source and commercial tools for 2D to 3D structure conversion and molecular manipulation. |

| Statistical & ML Libraries | Scikit-learn (Python) [36] | Provides PLSRegression class and other tools for model building and validation outside specialized suites. |

| Target & Compound Data | MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Line Assays [13] [4] | Provides essential experimental biological activity data (e.g., IC₅₀) for model training and validation. |