Integrating QSAR and Molecular Docking for Breast Cancer Drug Discovery: A Computational Guide

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integrated application of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling and molecular docking in breast cancer research.

Integrating QSAR and Molecular Docking for Breast Cancer Drug Discovery: A Computational Guide

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integrated application of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling and molecular docking in breast cancer research. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of these computational methods, details their synergistic workflow in identifying and optimizing drug candidates against targets like Tubulin, ERα, and Topoisomerase IIα. It further addresses critical challenges in model accuracy and validation, explores advanced techniques like molecular dynamics for troubleshooting, and discusses the essential role of experimental correlation in translating computational predictions into viable therapeutics. The content synthesizes current methodologies to offer a practical framework for enhancing the efficiency and success rate of anti-breast cancer drug development.

The Foundation of QSAR and Docking in Breast Cancer Research

Breast cancer remains a formidable global health challenge, characterized by significant molecular and clinical diversity. It is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women worldwide, and its heterogeneity profoundly impacts treatment efficacy and patient survival [1]. This diversity manifests through various pathologies, histological variations, and clinical outcomes, necessitating a move away from one-size-fits-all therapeutic approaches [2]. The disease is classified into multiple subtypes—including hormone receptor-positive (ER+/PR+), HER2-positive, and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)—each with distinct molecular drivers, treatment responses, and prognostic profiles [3]. The aggressive nature of TNBC, defined by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 expression, is particularly problematic as it constitutes 16% of all breast cancer cases and is unresponsive to conventional endocrine therapies or HER2-targeted agents [2].

The problem is further compounded by tumor heterogeneity and treatment resistance. According to a "Big Bang" model of tumor growth, spatial heterogeneity arises from consecutive mutations in different generations of cancer cells within a single tumor [1]. This intra-tumoral heterogeneity means that even if a targeted therapy eradicates all "sensitive" cells, a sub-population may survive and trigger a relapse. Additionally, cancer cell plasticity enables adaptation to molecularly targeted drugs through point mutations and the activation of alternative pathways, leading to acquired resistance [1]. Current therapeutic strategies, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and hormone therapy, are tailored to the patient's specific disease profile, yet controlling this complex tumor continues to present a global challenge for researchers [3].

The Limitations of Current Therapeutic Approaches

Despite advances in breast cancer management, several critical limitations persist in conventional treatment modalities, highlighting the urgent need for more sophisticated, targeted approaches.

Resistance to Conventional Therapies

The development of resistance, both inherent and acquired, represents a major hurdle in breast cancer treatment. Hormone therapies targeting estrogen receptors, while critical for ER+ breast cancer, often face resistance challenges. For instance, exemestane, one of the most potent aromatase inhibitors, encounters problems of resistance and side effects, limiting its long-term efficacy [4]. Similarly, chemotherapy, which remains the primary treatment modality for TNBC, shows limited effectiveness, with approximately only 20% of metastatic TNBCs responding effectively to standard paclitaxel or anthracycline-based regimens [2].

The heterogeneity of molecular drivers in breast cancer, especially in TNBC, means that targeting a single pathway often proves insufficient. This heterogeneity suggests a need for combinatorial therapies to target more than one molecular driver simultaneously, yet most current clinical trials combine chemotherapy with a molecularly targeted drug rather than targeting multiple molecular pathways concurrently [1].

Toxicity and Side Effects of Standard Treatments

Existing breast cancer medications are associated with significant side effects that impact patient quality of life and treatment adherence. These include gastrointestinal reactions, bone marrow suppression, and myocardial structural damage [5]. Hormone therapy can result in menopausal-like symptoms such as hot flashes, which can be severe enough to compromise treatment continuity [6]. The substantial burden of these adverse effects underscores the necessity for developing better-tolerated therapeutic options that maintain efficacy while minimizing collateral damage to healthy tissues.

Key Molecular Targets in Breast Cancer Pathogenesis

Advancing targeted therapies requires a deep understanding of the molecular pathways driving breast cancer progression. Several key targets have emerged as promising candidates for therapeutic intervention.

Table 1: Promising Molecular Targets for Breast Cancer Therapy

| Molecular Target | Biological Function | Breast Cancer Relevance | Therapeutic Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatase | Enzyme essential in estrogen biosynthesis | Critical for estrogen-sensitive breast cancer; promotes cancer cell proliferation | Aromatase inhibitors (e.g., exemestane) [4] |

| c-Met RTK | Receptor tyrosine kinase involved in cell migration and metastasis | Overexpressed in 20-30% of breast cancer cases and ~52% of TNBC; linked to lower survival | c-Met inhibitors (e.g., dasatinib analogs) [2] |

| Survivin | Member of inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAP) | Overexpressed in various cancers including breast cancer; undetectable in normal cells | siRNA delivery to silence expression [1] |

| TAARs (Trace amine-associated receptors) | G-protein-coupled receptors | Upregulated in basal-like and HER2+ subtypes; associated with mTOR pathway | TAAR antagonists [1] |

| PI3K/AKT Pathway | Intracellular signaling pathway important for cell cycle | Mutated in ~40% of hormone receptor-positive breast cancers | PI3K/AKT inhibitors (e.g., capivasertib) [1] [6] |

| Circulating Proteins (TLR1, A4GALT, SNUPN, CTSF) | Various functions in immune response and cellular processing | Identified through Mendelian randomization as causally linked to BC risk | Monoclonal antibodies, protein-targeting therapies [5] |

Beyond these specific targets, several key signaling pathways have been implicated in breast cancer pathogenesis and represent promising intervention points. The c-Met/HGF signaling pathway orchestrates cytoskeleton protein dynamics, remodeling, and reorganization, serving as the predominant molecular mechanism in HGF-induced cancer cell migration and metastasis [2]. Other crucial pathways include PARP1, mTOR, TGF-β, Notch signaling, Wnt/β-catenin, and Hedgehog pathways, all of which contribute to the complex molecular landscape of breast cancer [2].

Diagram 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Breast Cancer. This diagram illustrates the major signaling pathways implicated in breast cancer pathogenesis, showing how extracellular signals transduce into intracellular proliferation and survival mechanisms.

QSAR and Molecular Docking: Computational Approaches for Targeted Therapy Development

Computational methods have emerged as powerful tools for addressing the challenges in breast cancer drug discovery, offering more efficient and targeted approaches to therapeutic development.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR modeling represents a data-driven approach in ligand-based drug discovery that establishes correlations between numerical biological activities and molecular fingerprints of compounds [3]. This methodology facilitates virtual screening of extensive datasets for early drug design, structural optimization, predictive toxicology, and risk assessment [2]. QSAR models vary based on molecular descriptors, including 2-dimensional QSAR, 3-dimensional QSAR, and 4-dimensional QSAR approaches [3].

Recent advances have incorporated machine learning and deep learning algorithms to enhance QSAR predictive capabilities. Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) have achieved an impressive R² (Coefficient of Determination) of 0.94 with an RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) value of 0.255, demonstrating superior performance in developing structure-activity relationships with strong generalization capabilities [3]. These models are particularly valuable for predicting the biological activity of novel molecules based on structural information, thereby accelerating the drug discovery process.

Molecular Docking in Virtual Screening

Molecular docking methodology explores the behavior of small molecules in the binding site of a target protein, predicting the orientation of ligands when bound to a protein receptor [7]. This approach employs shape and electrostatic interactions to quantify binding affinity, with van der Waals interactions, Coulombic interactions, and hydrogen bond formation playing important roles in determining binding potential [7]. The sum of these interactions is approximated by a docking score, which represents the potentiality of binding and helps identify promising drug candidates.

Modern docking strategies have evolved from rigid-body approaches to flexible docking algorithms that account for ligand and receptor flexibility. While rigid-body docking produces a large number of docked conformations with favorable surface complementarity, flexible docking algorithms not only predict the binding mode of a molecule more accurately but also its binding affinity relative to other compounds [7]. These advanced approaches have become indispensable in virtual screening trials, enabling researchers to identify potential therapeutics with greater precision and efficiency.

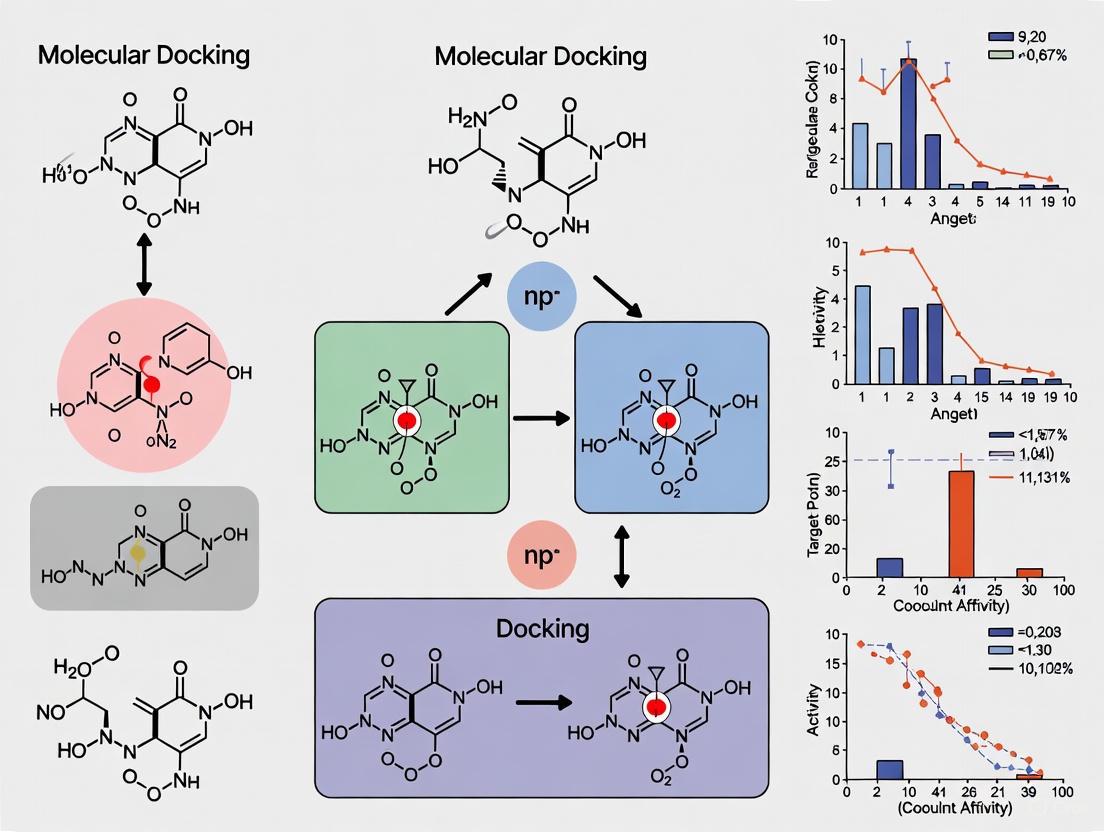

Diagram 2: Computational Drug Discovery Workflow. This diagram outlines the integrated computational approach combining QSAR modeling and molecular docking for targeted breast cancer therapy development.

Experimental Protocols for Targeted Therapy Development

Integrated QSAR Model Development Protocol

Dataset Curation: Collect a structurally diverse chemical series of known inhibitors. For breast cancer research, datasets may include naturally occurring plant-based scaffolds (e.g., terpene and its derivatives/analogs) against specific targets like c-Met [2]. Biological activities are typically collected as half maximal inhibitory concentration values (IC50 μM).

Molecular Descriptor Calculation: Calculate molecular descriptors using software such as the Padelpy library in Python. These descriptors quantitatively represent a molecule and can include topological, geometric, electronic, and physicochemical characteristics [3].

Data Pre-processing: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality and minimize noise, retaining 95% of the explained variance from the initial data. Address outliers through Boxcox, yeojohnsons, and logarithmic transformations to ensure normal distribution. Perform data encoding and standardization using libraries like Scikit-learn [3].

Model Training: Employ regression-based machine learning algorithms including Random Forest (RF), Extra Gradient Boost (XGB), Ridge Regression, k-Nearest Neighbours (kNN), LASSO Regression, Elastic Net Regression, CART, Stochastic Gradient Descent Regressor (SGD), Support Vector Regressor (rbf-SVR), Wider Neural Network (WNN), and Deep Neural Network (DNN) [3].

Model Validation: Partition the preprocessed dataset into training, testing, and validation sets in a 60:20:20 ratio. Validate model performance using metrics like R² (Coefficient of Determination), RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), MSE (Mean Square Error), and Fold Cross-validation scores [3].

Molecular Docking and Dynamics Protocol

Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., aromatase, c-Met) from the Protein Data Bank. Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands. Add hydrogen atoms and assign partial charges using appropriate force fields.

Binding Site Identification: Utilize cavity detection programs or online servers such as GRID, POCKET, SURFNET, PASS, and MMC to detect putative active sites within proteins [7].

Ligand Preparation: Sketch or obtain 3D structures of ligand molecules. Optimize geometry using molecular mechanics or quantum chemical calculations. Assign appropriate atomic charges and determine rotatable bonds.

Docking Simulation: Perform docking using programs such as AutoDock Vina, GOLD, or Glide. For flexible docking, allow rotation around rotatable bonds in the ligand and potentially side chains in the binding site. Generate multiple binding poses and rank them according to scoring functions [7] [8].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: Confirm binding stability through MD simulations (typically 100 nanoseconds). Calculate critical parameters including root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuations (RMSF), solvent accessible surface area (SASA), and radius of gyration (RoG). Evaluate changes in hydrogen bonds and distance between ligand and protein centers of mass [4].

Binding Affinity Calculation: Perform Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) calculations to assess binding free energy and validate docking results [4].

ADMET Profiling Protocol

Absorption Prediction: Evaluate compounds using the Rule of Five to assess oral bioavailability. Key parameters include hydrogen bond donors (<5), hydrogen bond acceptors (<10), molecular weight (<500), and log P (<5) [2].

Distribution Assessment: Predict blood-brain barrier penetration and plasma protein binding using in silico models.

Metabolism Evaluation: Identify potential sites of metabolism and predict metabolites using specialized software.

Excretion Prediction: Estimate clearance rates and elimination pathways.

Toxicity Screening: Assess mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, hepatotoxicity, and cardiotoxicity risks using computational models [2].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Targeted Breast Cancer Therapy Development

| Research Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide, MOE-Dock, FlexX | Predicts ligand-receptor binding orientation and affinity [7] [8] |

| QSAR Modeling Tools | PaDEL descriptors, Scikit-learn, Deep Neural Networks | Correlates molecular structure with biological activity [3] [2] |

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Provides 3D structural information for target proteins [7] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM | Simulates behavior of protein-ligand complexes over time [4] |

| Cancer Cell Lines | MDA-MB-231 (TNBC), MCF-7 (ER+) | In vitro models for validating anti-cancer activity [2] |

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL, GDSC2 (Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer) | Sources of compound bioactivity data for model training [3] [2] |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | SwissADME, admetSAR, ProTox-II | Predicts pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles [4] [2] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The landscape of targeted therapy development for breast cancer is rapidly evolving, with several promising approaches emerging from recent research.

Novel Therapeutic Modalities

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent a growing frontier in targeted breast cancer therapy. These sophisticated compounds act as "Trojan horses," seeking out and targeting cancer cells with a highly toxic payload that releases within the cell [9]. The SERIES study is evaluating patients with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-low metastatic breast cancer who have been treated with one ADC (trastuzumab deruxtecan) and then receive another (sacituzumab govitecan), representing one of the first prospective trials to study how ADCs work when given sequentially [9].

PROteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) offer another innovative approach. Vepdegestrant is the first PROTAC to be tested in phase 3 clinical trials for breast cancer. Like a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD), vepdegestrant eliminates the estrogen receptor from breast cancer cells, but unlike fulvestrant (which requires injections), it is a pill that can be taken orally [6]. Results from the phase 3 VERITAC-2 trial showed that vepdegestrant delayed ESR1 mutant metastatic breast cancer progression by 2.9 months compared to the SERD fulvestrant [6].

Mutation-Specific Targeting

Approximately 40% of hormone receptor-positive breast cancers harbor mutations in the PIK3CA gene. The mutated protein arising from PIK3CA mutations promotes cancer cell growth. RLY-2608 is a novel drug that specifically blocks the mutant protein from driving cancer growth while sparing the normal protein, potentially resulting in fewer unwanted side effects [6]. Early results showed that RLY-2608 combined with fulvestrant led to a median of 10.3 months before participants' metastatic breast cancer progressed, with a phase 3 trial scheduled to begin in 2025 [6].

Biomarker-Driven Treatment Strategies

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis through liquid biopsies is emerging as a valuable tool for guiding breast cancer treatment. Results from the PREDICT-DNA (TBCRC 040) trial showed that participants with detectable ctDNA after completing neoadjuvant chemotherapy were more likely to experience breast cancer recurrence than those without detectable ctDNA [6]. This information may be used to identify patients who need more aggressive treatment to reduce recurrence risk.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is also making inroads into breast cancer risk assessment. A new AI-based risk-assessment technology was recently granted FDA authorization specifically for predicting five-year breast cancer risk directly from a screening mammogram, representing a significant advancement in early detection capabilities [6].

The development of targeted therapies for breast cancer addresses the fundamental challenges posed by the disease's heterogeneity and resistance mechanisms. Through integrated computational approaches combining QSAR modeling, molecular docking, ADMET predictions, and molecular dynamics simulations, researchers can more efficiently identify and optimize promising drug candidates. These strategies enable a move away from conventional one-size-fits-all treatments toward personalized approaches that account for individual molecular profiles.

The continued evolution of targeted therapies—including antibody-drug conjugates, PROTACs, mutation-specific inhibitors, and biomarker-driven treatment strategies—holds considerable promise for improving outcomes for breast cancer patients. As these innovative approaches advance through clinical validation, they offer the potential for more effective, less toxic treatments that can overcome resistance mechanisms and provide lasting benefit to patients across the spectrum of breast cancer subtypes.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) is a computational methodology that employs mathematical models to correlate the biological activity of chemical compounds with their structural and physicochemical features [10]. This approach is founded on the principle that molecular structure determines properties, which in turn govern biological activity. In the pharmaceutical industry, QSAR serves as a pivotal component of computer-aided drug design (CADD), enabling researchers to predict compound activity, prioritize synthesis candidates, and optimize lead compounds more efficiently and cost-effectively than traditional wet-lab high-throughput screening alone [10].

The foundational concept of QSAR has evolved significantly since its early observations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The roots of QSAR can be traced back approximately 100 years to observations by Meyer and Overton that the narcotic properties of anesthetizing gases and organic solvents correlated with their solubility in olive oil [10]. A critical advancement came with the introduction of Hammett constants in the 1930s, which quantified the electronic effects of substituents on chemical reaction rates [10]. However, QSAR formally began in the early 1960s with the seminal work of Hansch and Fujita, who developed multiparameter equations incorporating substituent electronic properties and lipophilicity (logP), and Free and Wilson, who introduced a method quantifying the additive contributions of substituents at different molecular positions [10].

In the context of breast cancer research, QSAR provides a powerful strategy for addressing the persistent challenges of drug resistance, toxicity, and the need for more effective therapeutics [11] [12]. By establishing quantitative relationships between chemical structures and their anti-cancer activities, researchers can rationally design novel compounds with improved potency and selectivity against specific breast cancer targets, such as estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and tubulin [12] [13].

Fundamental Theoretical Concepts

The Pharmacophore Concept

A central concept in QSAR and drug design is the pharmacophore, defined as the essential geometric arrangement of atoms or functional groups in a molecule that is responsible for its biological activity through binding to a biomacromolecule [10]. The pharmacophore represents the critical molecular features that are common to all active molecules interacting with a particular target. In biochemistry, the specific region on a biomacromolecule where binding occurs is termed the binding site, while the portion of the interface area belonging to the drug is called the biophore [10]. Chemical groups that support the pharmacophore conformationally but are not part of the interface area are referred to as linkers or spacers [10].

Chemical Space and Molecular Descriptors

Chemical space is a theoretical concept representing the multidimensional domain defined by the chemical variation within a series of compounds [10]. A compound's position in this space determines its biological activity, and QSAR models typically focus on specific regions of chemical space where predictions are most reliable [10]. To navigate this space quantitatively, researchers utilize molecular descriptors - numerical representations of molecular structures and properties. These descriptors can be categorized into several types:

- Electronic descriptors: Quantify electronic properties relevant to molecular interactions, such as energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital (EHOMO), energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (ELUMO), absolute electronegativity (χ), and dipole moment (μm) [13].

- Topological descriptors: Derived from molecular connectivity, these include molecular weight (MW), Balaban Index (J), Wiener Index (WI), and number of rotatable bonds (NROT) [13].

- Physicochemical descriptors: Represent physical and chemical properties like octanol-water partition coefficient (LogP), water solubility (LogS), and polar surface area (PSA) [13].

Table 1: Key Categories of Molecular Descriptors in QSAR

| Descriptor Category | Representative Descriptors | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic | EHOMO, ELUMO, Electronegativity (χ), Dipole moment (μm) | Governs charge transfer interactions, binding affinity, and chemical reactivity |

| Topological | Molecular weight, Balaban Index (J), Wiener Index (WI) | Encodes molecular size, shape, branching, and structural complexity |

| Physicochemical | LogP, LogS, Polar Surface Area (PSA) | Influences solubility, permeability, and absorption characteristics |

| Geometrical | Molecular volume, Surface area, Shape coefficients | Affects steric complementarity with biological targets |

The selection of appropriate descriptors is critical for developing robust QSAR models. Descriptors should provide unique, non-redundant information about biological activity and exhibit low multicollinearity [13]. For instance, in a study on 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives as tubulin inhibitors for breast cancer therapy, absolute electronegativity (χ) and water solubility (LogS) were identified as significantly influencing inhibitory activity [13].

QSAR Methodology and Workflow

The development of a validated QSAR model follows a systematic workflow encompassing multiple critical stages, from data collection through model deployment. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive process:

Data Collection and Curation

QSAR modeling begins with assembling a library of chemical compounds with reliably measured biological activities [10]. For breast cancer research, this typically involves compounds tested against specific breast cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7) or molecular targets (e.g., ERα, tubulin). Biological activities are commonly expressed as half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) or inhibition constant (Ki), which are often transformed to logarithmic scale (pIC50 = -logIC50, pKi = -logKi) to reduce data dispersion and enhance linearity [12] [13]. To ensure data quality, compounds with multiple activity measurements may use median values to represent the biological activity [14].

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Data Pretreatment

Following data collection, molecular descriptors are calculated using specialized software tools. Common programs include PaDEL descriptor [12], Gaussian for quantum chemical descriptors [13], and ChemOffice for topological descriptors [13]. The resulting descriptor matrix often requires pretreatment to remove non-informative descriptors (those with constant or near-constant values) and reduce dimensionality [12]. Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) may be employed to transform original variables into orthogonal principal components that capture most of the variance in the data [10] [13].

The dataset is then divided into training and test sets, typically in ratios of 70:30 or 80:20 [12] [13]. The training set builds the model, while the test set provides an external validation of its predictive power. Proper division ensures both sets adequately represent the chemical space covered by the entire dataset.

Model Building Approaches

Multiple statistical and machine learning techniques are available for constructing QSAR models:

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR): A traditional approach that constructs linear relationships between descriptors and biological activity [13].

- Genetic Function Approximation (GFA): An evolutionary algorithm that generates multiple model forms and selects optimal combinations of descriptors [12].

- Evolutionary Programming (EP) Methods: Population-based search algorithms that explore descriptor space through mutation operations to identify optimal descriptor combinations [15].

The model building process aims to derive a mathematical equation that optimally correlates the selected molecular descriptors with the biological activity. For example, a penta-parametric QSAR model for 1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole derivatives achieved strong performance metrics (R²train = 0.896, Q²CV = 0.816, R²test = 0.703), indicating the predominant influence of molecular size, shape, and symmetry on cytotoxic effects against MCF-7 breast cancer cells [12].

Model Validation and Applicability Domain

Model validation is crucial to ensure reliability and predictive power. Key validation techniques include:

- Internal validation: Assesses model performance on the training data, using metrics like correlation coefficient (R²) and cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²CV) [12].

- External validation: Evaluates prediction accuracy for the test set not used in model building (R²test) [12].

- Statistical measures: Include mean squared error (MSE), Fisher's criteria (F), and significance level (p-value) [13].

The applicability domain defines the chemical space where the model provides reliable predictions. Models are typically valid only for compounds structurally similar to those in the training set [10]. Both qualitative SAR and quantitative QSAR models have distinct characteristics; comparative studies have shown that qualitative SAR models often demonstrate higher balanced accuracy (0.80-0.81) for classification tasks, while QSAR models provide continuous activity predictions with R² values around 0.59-0.64 for specific antitargets [14].

Integration with Complementary Computational Methods

In modern drug discovery, QSAR is rarely used in isolation. It is typically integrated with other computational approaches to provide comprehensive insights into drug-target interactions, particularly in breast cancer research.

Molecular Docking

Molecular docking predicts how small molecules interact with target macromolecules to form stable complexes [11]. It serves as a complementary approach to QSAR by providing structural insights into binding interactions. Docking protocols typically involve:

- Preparation of the protein target (e.g., removal of water molecules, addition of hydrogen atoms)

- Definition of the binding site and grid box

- Docking of ligand molecules using search algorithms

- Evaluation of binding poses using scoring functions [12]

For example, in a study of 1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole derivatives, molecular docking against ERα identified compounds with binding affinities superior to tamoxifen, an approved breast cancer drug [12].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations extend the static picture provided by docking to study the dynamic behavior of drug-target complexes over time [11]. By applying Newton's laws of motion to all atoms in the system, MD simulations can:

- Assess the stability of ligand-receptor complexes

- Identify conformational changes during binding

- Provide more accurate binding free energy estimates through methods like Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) [12]

In breast cancer drug design, MD simulations have demonstrated stable binding of potential therapeutics to targets like ERα and tubulin, with root mean square deviation (RMSD) values around 0.29 nm indicating tight binding conformations [12] [13].

ADMET Predictions

ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling predicts the pharmacological behavior and safety profiles of potential drug candidates [12]. QSAR models can be developed specifically for ADMET properties to filter out compounds with undesirable characteristics early in the drug discovery process. This is particularly important for avoiding interactions with antitargets - proteins associated with adverse drug reactions when inhibited [14].

Table 2: Integrated Computational Methods in Modern QSAR-Based Drug Discovery

| Method | Primary Function | Complementary Role to QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Predicts binding orientation and affinity | Provides structural context for QSAR observations; validates proposed activity mechanisms |

| Molecular Dynamics | Simulates temporal evolution of drug-target complexes | Assesses binding stability and conformational changes; refines binding affinity predictions |

| DFT Calculations | Computes electronic structure properties | Provides quantum mechanical descriptors for QSAR; elucidates reactivity and charge transfer |

| ADMET Prediction | Forecasts pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles | Filters promising candidates identified by QSAR; ensures drug-like properties |

Experimental Protocols in QSAR Modeling

Protocol 1: Development of a Robust QSAR Model

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing a validated QSAR model based on recent studies of anti-breast cancer agents [12] [13]:

Data Compilation: Collect structures and corresponding biological activities (e.g., IC50 values against MCF-7 cells) for a congeneric series of compounds from databases like PubChem or ChEMBL. A minimum of 20-30 compounds is typically required for meaningful model development.

Structure Optimization: Perform geometry optimization of all compounds using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., MMFF) followed by quantum chemical methods such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-31G* level to obtain energetically stable conformations [12] [13].

Descriptor Calculation: Calculate molecular descriptors using appropriate software. Electronic descriptors (EHOMO, ELUMO, electronegativity) may be computed with Gaussian software [13], while topological descriptors (MW, LogP, PSA) can be obtained with PaDEL descriptor or ChemOffice [12] [13].

Data Pretreatment and Division: Remove non-informative (constant or near-constant) descriptors. Divide the dataset into training and test sets using algorithms like Dataset Division GUI in a 70:30 or 80:20 ratio, ensuring both sets adequately represent the chemical space [12] [13].

Model Building: Employ variable selection techniques such as Genetic Function Approximation (GFA) or stepwise Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) to construct models correlating descriptors with biological activity. Select the optimal model based on statistical significance and mechanistic interpretability.

Model Validation: Validate models using both internal (cross-validation, Q²) and external (test set prediction, R²test) methods. The model should meet acceptable thresholds (e.g., R² > 0.6, Q² > 0.5) to be considered predictive [12].

Protocol 2: Integrated QSAR-Docking-MD Approach for Breast Cancer Drug Design

This protocol describes a comprehensive computational strategy for designing novel breast cancer therapeutics [12]:

Virtual Screening: Perform molecular docking of known active compounds against breast cancer targets (e.g., ERα, tubulin) using software like AutoDock or PyRx. Compare binding affinities with reference drugs (e.g., tamoxifen) to identify promising scaffolds.

QSAR Modeling: Develop a validated QSAR model as described in Protocol 1. Use the model to guide structural modifications for enhanced potency.

Lead Optimization: Design new analogs based on QSAR predictions and structural insights from docking. Prioritize compounds predicted to have higher activity than the lead compound.

Binding Affinity Assessment: Dock the designed compounds against the target and calculate binding free energies using MM/GBSA methods for more accurate affinity predictions [12].

Stability Evaluation: Conduct molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns) of the top-ranking ligand-receptor complexes to assess stability through RMSD, root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and other trajectory analyses [12] [13].

ADMET Profiling: Predict pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties of promising candidates using specialized software. Select compounds with favorable drug-like properties for further experimental validation.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for QSAR Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Primary Function in QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | PaDEL Descriptor [12], Gaussian [13], ChemOffice [13] | Generates molecular descriptors from chemical structures |

| Structure Optimization | Spartan [12], Gaussian [13] | Performs energy minimization and conformational analysis |

| Statistical Analysis & Modeling | Material Studio [12], XLSTAT [13] | Builds and validates QSAR models using various algorithms |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock [12], PyRx [12] | Predicts ligand-receptor binding modes and affinities |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Simulates dynamic behavior of drug-target complexes |

| Chemical Databases | PubChem [12], ChEMBL [14], Protein Data Bank [12] | Provides chemical structures, bioactivity data, and protein structures |

| Data Pretreatment | WSP Data Pretreatment Tool [12] | Filters non-informative descriptors from datasets |

QSAR represents a powerful paradigm for linking chemical structure to biological activity through quantitative mathematical models. Its core principles - that molecular properties determine biological activity and that these relationships can be captured through appropriate descriptors - continue to drive innovative drug discovery approaches. In breast cancer research, QSAR has evolved from a standalone technique to an integral component of comprehensive computational workflows that incorporate molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and ADMET profiling. This integrated approach enables the rational design of novel therapeutic agents with improved potency, selectivity, and safety profiles. As computational methods advance and chemical/biological datasets expand, QSAR methodologies will continue to play a crucial role in addressing the persistent challenge of breast cancer through more efficient and targeted drug discovery.

Molecular docking has emerged as a fundamental methodology in modern drug design, providing a computational approach to forecast atomic-level interactions between small molecules (ligands) and biological targets, typically proteins [16]. This process enables researchers to virtually screen how potential drug candidates bind to specific target proteins involved in diseases such as breast cancer [16]. In the context of breast cancer research—where breast cancer remains the most prevalent cancer among women and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths—molecular docking serves as a critical tool for identifying and optimizing therapeutic compounds in a rapid, cost-effective manner [11] [16]. The significance of molecular docking extends across multiple facets of drug discovery, including binding affinity prediction, where docking software calculates the strength of interaction between a ligand and protein; binding mode analysis, which reveals the precise orientation and conformation of the ligand when attached to the protein; and virtual screening, which enables efficient computational screening of large compound libraries [16].

When integrated with Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, molecular docking becomes particularly powerful for breast cancer drug discovery. QSAR models predict the physicochemical properties and biological activities of molecules based on their chemical structures, even in the absence of experimental data [17]. The combination of these computational techniques allows researchers to prioritize compounds for synthesis and biological testing, significantly accelerating the drug development pipeline against targets such as estrogen receptor (ER), HER2, CDKs, and other key players in breast cancer pathophysiology [11]. This integration represents a paradigm shift in anticancer drug development, moving from traditional trial-and-error approaches to targeted, rational drug design.

Theoretical Foundations of Molecular Docking

Fundamental Principles and Energy Considerations

At its core, molecular docking aims to predict the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target protein receptor, forming a stable complex [18]. The underlying principle involves searching for ligand conformations and orientations within the protein's binding site that minimize the free energy of the system [18]. The binding free energy (ΔG) represents the primary quantitative output of docking simulations, with more negative values indicating stronger binding affinity [16]. This theoretical framework operates on the assumption that the correct binding pose will correspond to the global minimum on the complex's energy landscape, though in practice, identifying this minimum poses significant computational challenges.

The search algorithm and scoring function represent the two fundamental components of any molecular docking workflow [18]. Search algorithms explore the conformational and orientational space of the ligand within the defined binding site, employing techniques such as systematic torsional searches, genetic algorithms, or Monte Carlo methods to generate plausible binding poses [18]. The scoring function then evaluates and ranks these generated poses based on estimated binding affinity, utilizing force field-based, empirical, or knowledge-based approaches to approximate the thermodynamic favorability of each protein-ligand configuration [18]. The accuracy of both conformational sampling and binding affinity prediction directly determines the practical utility of docking results in experimental design.

Key Methodologies and Search Strategies

Molecular docking methodologies have evolved to address various computational challenges and biological scenarios. Rigid-body docking treats both receptor and ligand as fixed structures, considering only rotational and translational degrees of freedom—this approach is computationally efficient but limited in accounting for molecular flexibility [18]. Flexible ligand docking allows conformational changes in the ligand while keeping the receptor rigid, representing the most common approach that balances accuracy and computational cost [18]. The most advanced flexible receptor docking methods incorporate limited receptor flexibility through side-chain rotations or ensemble docking, though these approaches remain computationally intensive [18].

Popular search algorithms include systematic searches that exhaustively explore torsional angles; stochastic methods like Monte Carlo that use random changes to escape local minima; and genetic algorithms that apply evolutionary principles of mutation and selection to optimize ligand pose [18]. Each method presents distinct trade-offs between computational efficiency and thoroughness of conformational sampling, with the optimal choice depending on the specific biological context and available computational resources.

Computational Workflow and Methodologies

The molecular docking process follows a structured workflow encompassing target preparation, ligand preparation, docking execution, and post-docking analysis. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive pipeline:

Target Preparation

The initial step involves preparing the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, typically obtained from experimental sources such as X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy [11]. Critical preprocessing steps include adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, optimizing side-chain conformations, and removing water molecules except those participating in key binding interactions [18]. The binding site must be precisely defined, either based on known experimental data regarding the active site or through computational detection of surface cavities likely to accommodate ligand binding [18]. For breast cancer targets like estrogen receptor or topoisomerase IIα, this often involves using crystal structures complexed with known inhibitors to guide binding site selection [17].

Ligand Preparation

Ligand preparation encompasses generating three-dimensional structures from two-dimensional representations, energy minimization to achieve stable conformations, and enumerating possible tautomers, protonation states, and stereoisomers at physiological pH [17]. Proper ligand preparation ensures comprehensive sampling of possible bioactive configurations during docking simulations. For naphthoquinone derivatives studied as topoisomerase IIα inhibitors in breast cancer research, this step is particularly crucial as different tautomeric forms can significantly impact binding interactions and predicted affinity [17].

Docking Execution and Post-Docking Analysis

The actual docking process involves the search algorithm generating multiple ligand poses within the binding site, followed by scoring function evaluation [18]. Following docking execution, post-docking analysis identifies consensus poses across different scoring functions, examines specific protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking, salt bridges), and clusters similar binding modes to prioritize candidates for further investigation [17]. For breast cancer drug discovery, this analysis often focuses on interactions with key residues in targets like HER2 or CDKs that are known to be critical for inhibitory activity [11].

Performance Comparison of Docking Methodologies

Software and Scoring Function Evaluation

Multiple studies have conducted comparative evaluations of docking programs to assess their relative performance in virtual screening scenarios. The table below summarizes key findings from a comprehensive assessment of three widely-used docking programs when applied to the same protein targets and ligand sets:

Table 1: Performance comparison of molecular docking software in virtual screening

| Docking Program | Average Enrichment Performance | Key Strengths | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glide XP | Consistently superior enrichments | Novel terms in scoring function, enhanced pose prediction | Computational intensity, parameter sensitivity |

| GOLD | Intermediate performance, outperforms DOCK | Genetic algorithm optimization, reliable binding mode prediction | Variable performance across target classes |

| DOCK | Lower average performance | Computational efficiency, extensive customization options | Lower pose accuracy in comparative studies |

This comparative analysis revealed that the Glide XP methodology consistently yielded enrichments superior to alternative methods, while GOLD generally outperformed DOCK on average [18]. Importantly, the study also demonstrated that docking into multiple receptor structures can decrease docking error when screening diverse sets of active compounds, highlighting the value of accounting for receptor flexibility [18].

Validation Against Experimental Data

A critical assessment of molecular docking predictions specifically examined the correlation between computed Gibbs free energy (ΔG) and in vitro cytotoxicity data (IC₅₀ values) obtained from MCF-7 breast cancer cell studies [16]. Contrary to theoretical expectations, findings demonstrated no consistent linear correlation between ΔG values and IC₅₀ across analyzed compounds and targets [16]. This discrepancy arises from several intertwined factors, including variability in protein expression within cell-based systems, compound-specific characteristics such as permeability and metabolic stability, and methodological limitations of docking approaches that rely on rigid receptor conformations and simplified scoring functions [16].

Table 2: Factors contributing to discrepancies between docking predictions and experimental results

| Factor Category | Specific Limitations | Impact on Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Methodological Limitations | Rigid receptor approximation, simplified scoring functions, inadequate solvation models | Inaccurate binding affinity predictions, incorrect pose identification |

| Biological Complexity | Intracellular metabolism, transport limitations, protein expression variability | Poor correlation between computed ΔG and cellular IC₅₀ values |

| Compound Characteristics | Membrane permeability, metabolic stability, off-target effects | Discrepancy between binding affinity and observed cytotoxicity |

| System Preparation | Incorrect protonation states, missing cofactors, inadequate water modeling | Reduced reliability of predicted protein-ligand interactions |

Nevertheless, when experimental and computational systems are uniformly controlled, a measurable and meaningful correlation between ΔG and IC₅₀ can be demonstrated [16]. This underscores the importance of standardized conditions and careful interpretation of docking results within appropriate biological contexts.

Integration with QSAR in Breast Cancer Research

Combined Computational Workflow

The integration of molecular docking with QSAR modeling represents a powerful combined approach for breast cancer drug discovery. The synergy between these methods creates a comprehensive computational pipeline that leverages the strengths of both techniques. QSAR models establish mathematical correlations between molecular structures and biological activities, enabling the prediction of anticancer potency for novel compounds before synthesis [17]. When combined with molecular docking, which provides atomic-level insights into binding interactions, researchers can simultaneously optimize for both binding affinity and compound properties related to bioavailability and toxicity [17].

In practice, this integrated workflow begins with QSAR modeling to identify structural features correlated with enhanced activity against breast cancer targets, followed by molecular docking to understand the structural basis for these activity relationships and suggest further modifications [17]. For example, in studies of naphthoquinone derivatives as topoisomerase IIα inhibitors, robust QSAR models were constructed using Monte Carlo optimization to predict pIC₅₀ values, with molecular docking then employed to elucidate interactions with the active site and explain the superior activity of specific derivatives [17]. This combined approach provides both predictive power and mechanistic understanding, facilitating more rational drug design.

Experimental Validation and ADMET Profiling

For computational predictions to have translational value, integration with experimental validation is essential. Following docking studies and QSAR analysis, promising compounds should undergo in vitro testing against breast cancer cell lines such as MCF-7 to determine experimental ICâ‚…â‚€ values [16] [17]. Additionally, ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling provides critical data on pharmacokinetic properties, bioavailability, and elimination profiles [17]. Modern integrated studies often include molecular dynamics simulations to validate the stability of ligand-receptor complexes under physiologically relevant conditions, with simulations typically running for 100-300 nanoseconds to assess conformational stability and interaction persistence [17].

The combination of these computational and experimental approaches creates a robust framework for advancing breast cancer drug candidates. For instance, in the development of topoisomerase IIα inhibitors, this integrated strategy has identified key molecular features responsible for enhanced activity, including specific functional groups that form critical hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues ASP479 and GLN778 in the binding site [17]. Such insights guide medicinal chemists in designing more potent and selective inhibitors for experimental evaluation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of molecular docking studies requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table outlines essential components of the molecular docking toolkit:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for molecular docking

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | Glide, GOLD, DOCK, AutoDock | Pose generation and scoring, virtual screening |

| Protein Structure Resources | PDB, AlphaFold predicted models | Source of 3D protein structures for docking |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, PubChem, in-house collections | Sources of small molecules for virtual screening |

| Structure Preparation Tools | Schrödinger Protein Preparation Wizard, MOE | Hydrogen addition, bond order assignment, energy minimization |

| Visualization & Analysis | PyMOL, Chimera, Discovery Studio | Results visualization, interaction analysis |

| Supplementary Tools | CORAL software, MD simulation packages | QSAR model development, dynamics validation |

The selection of appropriate tools depends on the specific research objectives, with integrated platforms like Schrödinger providing comprehensive workflows from preparation through analysis, while standalone tools may offer advantages for specific applications or customization [18] [17].

Molecular docking represents an indispensable computational methodology in breast cancer drug discovery, providing atomistic insights into receptor modulation, drug resistance, and rational therapeutic design [11]. When integrated with QSAR modeling and experimental validation, docking simulations significantly accelerate the identification and optimization of potential therapeutics against key breast cancer targets including ER, HER2, CDKs, microtubule-binding sites, and emerging regulators [11]. Despite persistent challenges in clinical adoption due to issues of accuracy, validation, and interpretability, ongoing methodological advances continue to enhance the reliability and applicability of docking predictions [11].

Future developments will likely focus on incorporating artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches to improve scoring functions and conformational sampling [11] [19]. Additionally, more sophisticated treatment of receptor flexibility through ensemble docking and molecular dynamics simulations will better capture the dynamic nature of protein-ligand interactions [11] [17]. The integration of large language models and AlphaFold-predicted structures promises to expand docking applications to targets without experimental structures [19]. As these computational methodologies mature and validation against experimental data improves, molecular docking will continue to play an increasingly central role in the rational design of targeted therapies for breast cancer treatment.

Breast cancer's clinical and molecular heterogeneity necessitates the development of targeted therapies directed against specific proteins that drive tumor growth and progression. Computational approaches, including Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling and molecular docking, have become indispensable tools for identifying and optimizing compounds that interact with these key targets. These in silico methods enable researchers to predict biological activity, visualize atomic-level interactions, and rationalize drug design, thereby accelerating the discovery of novel anti-breast cancer agents [10] [20]. The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation creates a powerful pipeline for translating theoretical models into tangible therapeutic strategies.

This guide provides a technical overview of critical protein targets in breast cancer, detailing their biological roles, significance in specific subtypes, and utility in structure-based drug design. We present standardized computational methodologies for studying these targets, summarize key experimental protocols for biological validation, and catalog essential research reagents. The focus is on creating a practical resource that bridges computational predictions with experimental workflows, framed within the context of understanding molecular docking in QSAR for breast cancer research.

Key Breast Cancer Targets for Computational Screening

Table 1: Primary Protein Targets for Anti-Breast Cancer Computational Studies

| Target Protein | PDB ID Examples | Biological Role in Breast Cancer | Therapeutic Significance | Associated Breast Cancer Subtypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen Receptor α (ERα/ESR1) | 6VJD, 7LD3 | Nuclear hormone receptor; regulates proliferation gene transcription [21] [22] | Primary target for endocrine therapy (SERMs, SERDs); mutations (e.g., ESR1) confer resistance [21] [20] | Luminal A, Luminal B [23] [20] |

| Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2/ERBB2) | 7JXH | Receptor tyrosine kinase; drives proliferative and survival signaling [24] | Target for monoclonal antibodies (trastuzumab), TKIs (lapatinib); antibody-drug conjugates (T-DM1, DS-8201) [25] [20] | HER2-enriched [23] [25] |

| Aromatase (CYP19A1) | 6ME6 | Cytochrome P450 enzyme; catalyzes estrogen biosynthesis [24] | Target for aromatase inhibitors (letrozole, exemestane) to reduce estrogen levels in postmenopausal women [23] [24] | Hormone Receptor-Positive (Luminal) [23] |

| Progesterone Receptor (PR/PGR) | 2W8Y | Nuclear hormone receptor; collaborates with ERα in proliferation [21] | Prognostic marker; co-target with ERα in multitarget drug design [21] | Luminal A, Luminal B [23] |

| Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase (PARP10) | Information Missing | Involved in DNA repair mechanisms [24] | PARP inhibition causes synthetic lethality in BRCA-deficient cells; target for TNBC [24] [20] | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) [20] |

| Tubulin | Information Missing | Cytoskeletal protein; essential for cell division and mitosis [25] | Target for antimitotic chemotherapies (paclitaxel) [25] | All subtypes, particularly TNBC [25] |

| Protein Kinase MYT1 (PKMYT1) | Information Missing | Cell cycle regulator kinase; inhibits CDK1 [24] | High levels correlate with CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance; siRNA-mediated knockdown can restore sensitivity [24] | Estrogen Receptor-Positive (ER+) [24] |

Table 2: Emerging and Secondary Targets for Advanced Studies

| Target Protein | PDB ID Examples | Biological Role in Breast Cancer | Therapeutic Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRC Kinase | Information Missing | Non-receptor tyrosine kinase; regulates proliferation, survival, migration, and invasion [22] | Potential target for overcoming multidrug resistance; identified via network pharmacology [22] |

| Stimulator of Interferon Genes (STING) | Information Missing | Innate immune sensor; activates anti-tumor immunity [24] | Immunotherapeutic target; agonists may promote tumor microenvironment inflammation [24] |

| Melatonin Receptor 2 (MT2) | Information Missing | G-protein coupled receptor; regulates circadian rhythm and cell proliferation [24] | Agonists may induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation [24] |

| Adenosine A1 Receptor | 7LD3 | G-protein coupled receptor; modulates immune and metabolic responses [26] | Identified via bioinformatics screening; stable binding of ligands correlates with antitumor activity [26] |

Integrated Computational Workflows for Target Screening and Validation

The standard pipeline for computer-aided drug design (CADD) in breast cancer integrates multiple computational techniques, from initial target identification to final lead optimization. This workflow leverages both structure-based and ligand-based design principles, increasingly enhanced by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) modules [20].

Figure 2: Integrated Computational Drug Discovery Workflow

Molecular Docking and Dynamics Protocols

Molecular Docking Protocol for Target-Ligand Interaction Analysis

Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., ERα PDB: 6VJD) from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands. Add hydrogen atoms, assign bond orders, and optimize side-chain conformations for residues in the binding pocket. Perform energy minimization using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., AMBER99SB-ILDN) to relieve steric clashes [26] [21].

Ligand Preparation: Draw or retrieve the 2D structure of the candidate ligand from databases like PubChem. Convert to 3D structure and perform geometry optimization using density functional theory (DFT) methods, such as with the LanL2DZ basis set. Confirm the optimized structure has no imaginary frequencies [21]. Generate multiple conformational isomers for flexible docking.

Docking Simulation: Define the binding site coordinates based on the known active site or the position of a co-crystallized native ligand. Utilize docking software such as AutoDock Vina, Molegro Virtual Docker, or Discovery Studio. Set docking parameters to account for ligand flexibility and limited protein side-chain flexibility. Run multiple docking simulations and cluster the resulting poses by root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) [24] [26].

Pose Analysis and Scoring: Select the top-ranked poses based on the docking scoring function (e.g., LibDockScore, ΔG binding affinity in kcal/mol). Analyze key interactions—hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking, and halogen bonds—using visualization tools like Discovery Studio Visualizer or MolSoft ICM Browser. Rescore promising complexes using more advanced scoring functions or MM-GBSA calculations [24] [26].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Protocol for Binding Stability

System Setup: Place the docked protein-ligand complex in a simulation box (e.g., cubic) with a minimum 0.8 nm distance between the complex and the box boundary. Solvate the system using an explicit solvent model, such as TIP3P water molecules. Add counterions (e.g., Naâº, Clâ») to neutralize the system's net charge [26] [22].

Energy Minimization and Equilibration: Perform energy minimization (e.g., 5000 steps of steepest descent) to remove atomic clashes. Conduct a two-phase equilibration: first, an NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) for 100 ps to stabilize the temperature at 298.15 K; second, an NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) for 100 ps to stabilize the pressure at 1 bar [26].

Production MD Run: Execute an unrestrained production MD simulation for a sufficient timeframe (typically 50-200 ns) using a time step of 2 fs. Maintain constant temperature and pressure using algorithms like Berendsen or Parrinello-Rahman coupling. Save trajectory coordinates every 10-100 ps for subsequent analysis [21] [22].

Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the saved trajectories using tools like GROMACS or VMD. Calculate key metrics to assess complex stability:

- Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the structural stability of the protein and ligand over time.

- Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies flexible regions of the protein.

- Radius of Gyration (Rg): Assesses the overall compactness of the protein.

- Hydrogen Bond Occupancy: Quantifies the persistence of specific protein-ligand interactions [26] [22].

QSAR and Pharmacophore Modeling

QSAR Modeling Workflow:

- Data Set Curation: Compile a library of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., ICâ‚…â‚€ or pICâ‚…â‚€ values) against the target of interest. Ensure chemical diversity and a sufficient number of compounds (typically >30) for model reliability [21] [10].

- Descriptor Calculation and Selection: Compute a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors (electronic, thermodynamic, topological) for all compounds. Use statistical methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and multiple correlation analyses to select the most relevant, non-redundant descriptors that correlate with biological activity [21] [10].

- Model Building and Validation: Apply regression or machine learning algorithms to construct a mathematical model correlating descriptors with activity. The model must be rigorously validated using internal (e.g., leave-one-out cross-validation, Q²) and external validation (a test set of compounds not used in training) to ensure its predictive power and avoid overfitting [10].

Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- Ligand-Based Approach: Align a set of known active compounds and identify common chemical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, ionizable groups) essential for binding and activity. Use this spatial arrangement to create a model for virtual screening of compound libraries [26] [10].

Experimental Validation of Computational Predictions

Table 3: Key Experimental Assays for Validating Computational Findings

| Assay Type | Protocol Summary | Key Outcome Measures | Relation to Computational Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Cytotoxicity (MTT/MTS) | Seed MCF-7 (ER+) or MDA-MB-231 (TNBC) cells in 96-well plates. Treat with serially diluted compound for 48-72 hrs. Add MTT reagent, incubate, and solubilize formazan crystals. Measure absorbance at 570 nm [16] [26]. | IC₅₀ Value: Concentration inhibiting 50% of cell growth. Validates predicted binding affinity (ΔG) from docking [16] [26]. | Lower IC₅₀ should correlate with more negative (favorable) predicted ΔG values. Discrepancies highlight limitations of simplified docking models [16]. |

| Apoptosis Assay (Annexin V/PI) | Treat cells with candidate compound. Harvest cells, stain with Annexin V-FITC and Propidium Iodide (PI). Analyze by flow cytometry to distinguish live (Annexin Vâ»/PIâ»), early apoptotic (Annexin Vâº/PIâ»), late apoptotic (Annexin Vâº/PIâº), and necrotic (Annexin Vâ»/PIâº) populations [22]. | Percentage of cells in early and late apoptosis. Confirms activation of cell death pathways by the compound. | Supports mechanism of action suggested by target engagement (e.g., if target is involved in apoptosis regulation). |

| Cell Migration Assay (Wound Healing/Scratch) | Create a uniform "wound" in a confluent cell monolayer. Wash away debris and add medium with/without compound. Capture images at 0, 24, and 48 hours at the same location. Measure the change in wound width over time [22]. | Percentage of wound closure over time. Indicates anti-migratory (potential anti-metastatic) effect. | Complements binding predictions to targets involved in metastasis (e.g., SRC kinase) [22]. |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation | Incubate cells with compound and a fluorescent ROS-sensitive dye (e.g., DCFH-DA). Measure fluorescence intensity using a microplate reader or flow cytometry. Increased fluorescence indicates higher intracellular ROS levels [22]. | Fold-change in fluorescence intensity relative to untreated control. Indicates oxidative stress induction as a mechanism. | Can validate predictions related to compounds that modulate mitochondrial function or induce oxidative stress. |

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Breast Cancer Studies

| Reagent / Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software for Molecular Modeling | Molegro Virtual Docker, AutoDock Vina, Discovery Studio, GROMACS, VMD | Perform molecular docking, virtual screening, molecular dynamics simulations, and trajectory analysis [24] [26]. |

| Target Prediction & Bioinformatics Tools | SwissTargetPrediction, STITCH, GeneCards, OMIM, STRING, Venny | Identify potential protein targets for a compound and find common targets between breast cancer and a drug candidate [26] [22]. |

| Cell Lines for In Vitro Validation | MCF-7 (ERâº, PRâº), MDA-MB-231 (TNBC), T-47D (ERâº, PRâº), BT-474 (HER2âº) | Model different breast cancer subtypes for cytotoxicity, apoptosis, migration, and other phenotypic assays [16] [26] [22]. |

| Key Chemical Reagents & Assay Kits | MTT/MTS reagent, Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Kit, DCFH-DA dye, Matrigel for invasion assays | Enable experimental validation of computational predictions through cell-based assays measuring viability, death, and other metrics [22]. |

| Public Databases & Repositories | Protein Data Bank (PDB), PubChem, Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Provide 3D protein structures for docking and chemical information/structures of small molecules [26]. |

The strategic integration of computational and experimental approaches provides a powerful framework for advancing breast cancer drug discovery. Focusing on well-validated, subtype-specific targets like ERα, HER2, and aromatase, as well as emerging targets such as PKMYT1 and STING, allows researchers to design more precise and effective therapeutic strategies. Adherence to standardized computational protocols for docking, dynamics, and QSAR modeling ensures the generation of reliable, reproducible data that can effectively guide experimental efforts. As the field evolves, the incorporation of AI and multi-omics data into these workflows promises to further enhance the predictive accuracy and therapeutic impact of computational drug design, ultimately contributing to more personalized and effective treatments for breast cancer patients.

A Practical Workflow: From Data Curation to Integrated QSAR-Docking Analysis

Within the strategic framework of computer-aided drug design (CADD) for breast cancer, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a powerful, ligand-based predictive tool. Its fundamental premise is that the biological activity of a compound is a direct function of its molecular structure [10]. The initial step of curating and preparing a congeneric dataset is therefore the critical foundation upon which all subsequent modeling, including molecular docking studies, is built. A robust, well-prepared dataset enables researchers to derive a reliable mathematical model that connects molecular descriptors to a biological endpoint, such as inhibition of the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) or tubulin in breast cancer cells [12] [13]. This model can then be used to predict the activity of novel compounds, prioritize the most promising candidates for synthesis, and provide insights into the structural features essential for anti-cancer activity, thereby streamlining the drug discovery pipeline.

Data Collection and Sourcing

The first operational stage involves the systematic gathering of biological activity data and chemical structures for a set of compounds that have been tested against a specific breast cancer-related target or cell line.

Researchers typically source data from publicly available biochemical databases and scientific literature. Key repositories include:

- PubChem BioAssay: A primary source for data on the biological activities of small molecules. For instance, a study on 1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole derivatives extracted 44 compounds with reported in vitro cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells from this database (AID: 1244541) [12].

- NPACT Database: A specialized database containing naturally occurring plant-derived compounds with established anticancer activities and associated cell line profiles (e.g., MCF-7) [27].

- GDSC2 (Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer) Database: Provides extensive data on drug sensitivity, including combinational therapy responses across numerous cancer cell lines, which can be used for developing novel combination QSAR models [3].

- Scientific Literature: Peer-reviewed publications remain a vital source for curated datasets of congeneric series, such as the 32 derivatives of 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one with inhibitory efficacy against MCF-7 cells [13].

Activity Data and Endpoints

The biological activity, often reported as the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), must be converted into a format suitable for linear regression analysis. This is typically done by calculating the negative logarithm of the IC50 value in molar units (pIC50 = -log IC50) to reduce data dispersion and achieve a more linear relationship with structural parameters [12] [27] [13].

Table 1: Key Public Databases for Breast Cancer QSAR Data

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Key Features | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem BioAssay [12] | Small molecule bioactivities | Large repository of HTS data; contains structures and IC50 values. | Sourcing 1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole derivatives active against MCF-7. |

| NPACT [27] | Natural anti-cancer products | Curated plant-derived compounds with anti-cancer activity. | Building a model for natural inhibitors of the MCF-7 cell line. |

| GDSC2 [3] | Drug sensitivity & combination | Data on monotherapy and combinational therapy across cell lines. | Developing a combinational QSAR model for breast cancer. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | 3D Protein Structures | Not a source of compound data, but essential for obtaining the target protein structure for subsequent molecular docking. | Retrieving the structure of ERα (5GS4) or HER2 (3PP0) [12] [27]. |

Data Curation and Preprocessing

Once collected, the raw data must undergo rigorous curation to ensure homogeneity, reliability, and consistency, which are prerequisites for a statistically significant QSAR model.

Standardization and Cleaning

- Removal of Duplicates and Inorganics: Repeated compounds, salts, inorganics, and organometallics are identified and removed to prevent bias [27].

- Structure Standardization: All molecular structures are standardized, which may include neutralizing charges, removing counterions, and generating canonical tautomers [27].

- Activity Data Curation: When multiple activity values exist for a single chemical, the lowest IC50 value (representing the highest potency) is often selected under a "worst-case scenario" principle to enhance model robustness [27]. Measurements reported as "nominal concentrations" are excluded.

Chemical Space and Congenericity Assessment

A congeneric series is a set of compounds sharing a common core scaffold but differing in their substituents. Ensuring that the dataset occupies a relevant and constrained chemical space is vital for the model's applicability. Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are used to visualize the distribution of compounds and identify any significant outliers that fall outside the main chemical space of interest [3] [28]. This step confirms the congenericity of the dataset and helps define the model's applicability domain.

Molecular Geometry Optimization

Before molecular descriptors can be calculated, the 3D geometry of each compound must be optimized to its lowest energy conformation, representing its most stable state in a biological environment.

A common and robust protocol involves a cascading optimization approach:

- Initial Minimization: Using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., MMFF) for a rapid preliminary optimization [12].

- Quantum Mechanical Refinement: Further optimization using Density Functional Theory (DFT) methods. A standard setup employs the B3LYP hybrid functional and the 6-31G* basis set, as performed for 1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole derivatives [12]. Other studies may use the 6-31G(p,d) basis set for higher accuracy [13]. This step provides high-quality geometries and electronic properties essential for certain descriptor types.

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations of a compound's structural and physicochemical properties. They serve as the independent variables in a QSAR model.

Descriptor Calculation

Software tools like PaDEL Descriptor [12] [27] [3] and ChemOffice [13] are widely used to calculate thousands of 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors. Additionally, quantum chemically computed electronic descriptors (e.g., HOMO/LUMO energies, dipole moment, absolute electronegativity) are calculated from the DFT-optimized structures using software like Gaussian [13].

Descriptor Selection and Data Pretreatment

The initial descriptor pool is often excessively large and contains redundant or non-informative variables. A rigorous preprocessing workflow is applied:

- Removal of Non-Informative Descriptors: Descriptors with zero variance, constant values, or high pairwise correlation are filtered out. Tools like the WSP data pretreatment tool from the DTC-Lab can be used for this purpose [12].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are employed to transform the remaining descriptors into a smaller set of orthogonal (uncorrelated) Principal Properties (PPs) that explain most of the variance in the original data [3] [28]. This reduces the risk of model overfitting.

Table 2: Categories of Molecular Descriptors in QSAR Studies

| Descriptor Category | Description | Key Examples | Relevance to Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topological [3] [13] | Based on molecular graph theory. | Wiener Index, Balaban Index, Molecular Topological Index. | Related to molecular size, branching, and shape. |

| Geometric [3] | Derived from 3D molecular geometry. | Principal Moments of Inertia, Molecular Surface Area. | Influences binding to the protein's active site. |

| Electronic [12] [13] | Describe electron distribution. | HOMO/LUMO energies, Dipole Moment (μm), Absolute Electronegativity (χ). | Critical for predicting reaction mechanisms and binding interactions. |

| Physicochemical [13] | Fundamental physical and chemical properties. | logP (lipophilicity), logS (water solubility), Molecular Weight (MW), Polar Surface Area (PSA). | Determines drug-likeness and ADMET properties. |

Dataset Division for Modeling and Validation

The final curated dataset of compounds and their descriptors must be divided into subsets to build and validate the QSAR model.

The standard practice is to split the data into a training set and a test set. Common split ratios include:

- 70:30 or 80:20 (Training:Test) [12] [13].

- The split should be performed in a randomized manner to avoid bias and ensure both sets are representative of the overall chemical space and activity range [13].

- Specialized tools like the Dataset Division GUI from the DTC laboratory can be used to perform this division [12]. For machine learning-based QSAR, a third validation set (e.g., 60:20:20 for Train:Test:Validation) may be created to fine-tune hyperparameters [3].

The training set is used to build the model, while the test set, which the model has never seen during training, is used to evaluate its predictive power on new, external compounds.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for curating and preparing a congeneric compound dataset for a QSAR study in breast cancer research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for Dataset Curation and Preparation

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Dataset Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| PubChem / NPACT / GDSC2 [12] [27] [3] | Online Database | Primary sources for chemical structures and associated biological activity data (IC50) against breast cancer targets. |

| PaDEL Descriptor [12] [27] [3] | Software | Calculates a comprehensive set of 1D and 2D molecular descriptors directly from chemical structures. |