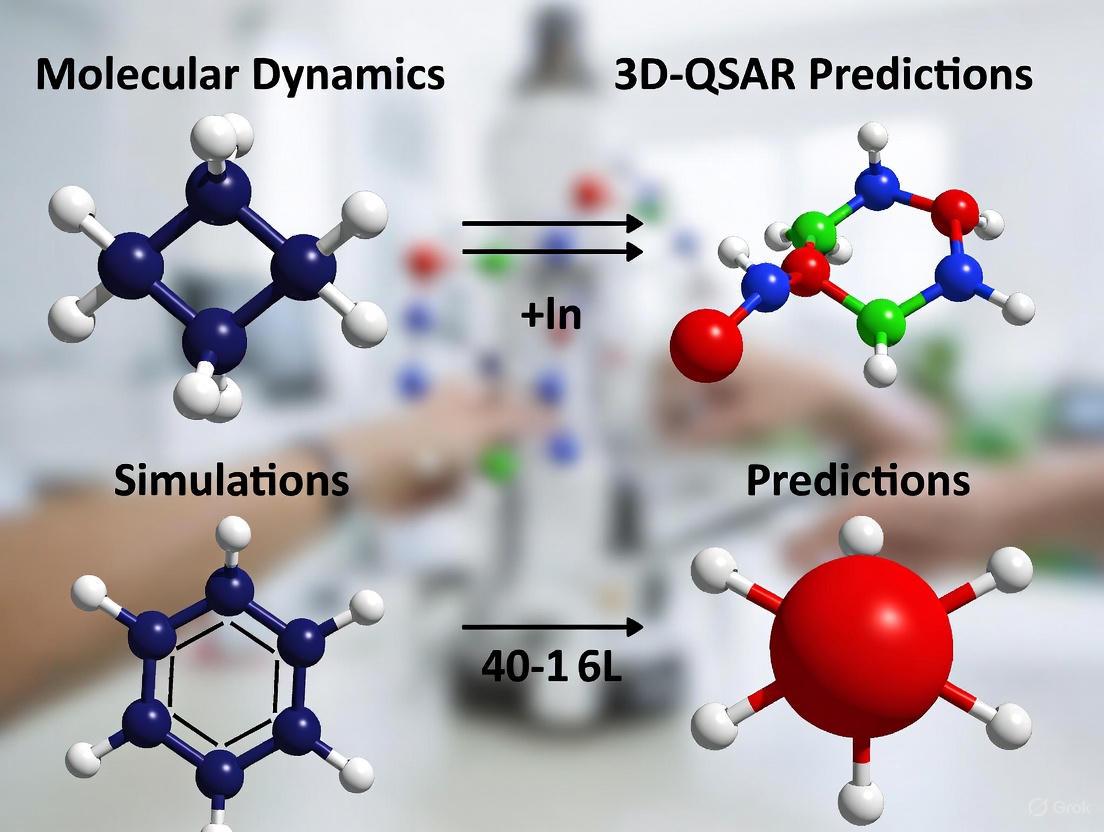

Integrating Molecular Dynamics Simulations to Validate and Enhance 3D-QSAR Predictions in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the integrated use of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to validate and refine 3D-Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) predictions.

Integrating Molecular Dynamics Simulations to Validate and Enhance 3D-QSAR Predictions in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the integrated use of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to validate and refine 3D-Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) predictions. It covers the foundational principles of both methodologies, outlines a practical workflow for their synergistic application, and addresses key challenges in model interpretation and optimization. Through illustrative case studies and a discussion of validation protocols, the content demonstrates how this combined computational approach provides dynamic, mechanistic insights that surpass the static predictions of 3D-QSAR alone, ultimately leading to more reliable and efficacious drug candidate design.

Understanding the Synergy: 3D-QSAR and Molecular Dynamics in Modern Drug Design

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery. The evolution from classical QSAR to three-dimensional (3D-QSAR) methods marks a significant paradigm shift from treating molecules as simple collections of descriptors to analyzing them as complex three-dimensional entities with specific shapes and interaction fields. 3D-QSAR has emerged as a natural extension to classical Hansch and Free-Wilson approaches, which exploits the three-dimensional properties of the ligands to predict their biological activities using robust chemometric techniques [1]. This approach considers the molecule as a 3D object with a specific shape and interaction fields (regions of positive/negative charge, steric bulk, etc.) around it, providing a more realistic representation of molecular interactions in biological systems [2].

The integration of 3D-QSAR within broader drug discovery pipelines, particularly when combined with molecular dynamics simulations, creates a powerful framework for validating predictions and understanding the dynamic behavior of protein-ligand complexes. This combination allows researchers to move beyond static snapshots of binding interactions toward a more comprehensive understanding of conformational flexibility and binding stability under physiologically relevant conditions [3] [4].

Fundamental Principles of 3D-QSAR

Core Theoretical Concepts

The fundamental principle underlying all QSAR formalism is that differences in structural properties are responsible for variations in biological activities of compounds [1]. While classical 2D-QSAR methods use numeric descriptors of molecules that are invariant to conformation, 3D-QSAR derives descriptors directly from the spatial structure of the molecule [2]. This fundamental distinction enables 3D-QSAR to capture essential steric and electronic features that govern molecular recognition and binding.

The theoretical foundation rests on several key principles:

- Molecular Similarity: Structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities

- Field Analysis: Molecular interactions can be quantified through steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields

- Alignment Dependency: Accurate spatial alignment of molecules is crucial for meaningful comparison of their interaction fields

- Conformational Dependency: Biological activity is influenced by the three-dimensional conformation that molecules adopt when binding to their targets

Comparison of 2D vs. 3D-QSAR Approaches

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between 2D and 3D-QSAR Approaches

| Feature | 2D-QSAR | 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representation | Flat structures, topological descriptors | 3D structures, spatial descriptors |

| Descriptors Used | logP, molar refractivity, topological indices | Steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic fields |

| Conformational Sensitivity | Insensitive to conformation | Highly dependent on bioactive conformation |

| Alignment Requirement | Not required | Critical step in model development |

| Information Content | Global molecular properties | Local interaction properties |

| Visualization Capability | Limited to structure-activity trends | 3D contour maps guiding structural modifications |

Methodological Framework and Protocols

Standard 3D-QSAR Workflow

The development of a robust 3D-QSAR model follows a systematic workflow encompassing multiple critical stages. The diagram below illustrates this comprehensive process from data collection to model application.

Data Collection and Preparation Protocol

Protocol 3.2.1: Compound Selection and Activity Data Curation

Compound Selection Criteria:

- Select 20-50 compounds with structurally related scaffolds but varying substituents

- Ensure sufficient diversity in substituents to cover a range of electronic, steric, and hydrophobic properties

- Include compounds with a wide range of biological activities (ideally spanning 2-3 orders of magnitude in IC₅₀, Kᵢ, or equivalent metrics)

Activity Data Requirements:

Dataset Division:

- Divide compounds into training set (80-85%) and test set (15-20%)

- Ensure test set compounds represent the structural and activity space of the training set

- Use rational selection methods (e.g., Kennard-Stone, sphere exclusion) rather than random selection

Molecular Modeling and Alignment Protocol

Protocol 3.3.1: 3D Structure Generation and Optimization

Structure Generation:

- Convert 2D representations to 3D coordinates using tools like RDKit or Sybyl [2]

- Generate multiple conformers for each compound using systematic search or stochastic methods

- Select lowest energy conformer or putative bioactive conformation for alignment

Geometry Optimization:

- Perform molecular mechanics optimization using universal force field (UFF) or similar [2]

- For higher accuracy, apply quantum mechanical methods (semi-empirical or DFT)

- Ensure convergence criteria are properly set (energy gradient < 0.05 kcal/mol·Å)

Molecular Alignment:

- Identify common substructure or pharmacophore using maximum common substructure (MCS) or Bemis-Murcko scaffolds [2]

- Superimpose molecules to a reference compound based on atomic correspondence

- Validate alignment quality through visual inspection and RMSD calculations

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building

Protocol 3.4.1: Field-Based Descriptor Calculation

Grid Generation:

- Create a 3D grid that encompasses all aligned molecules with 1-2 Å extension in all directions

- Set grid spacing to 1-2 Å for optimal resolution and computational efficiency

Interaction Field Calculation:

- CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis): Calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields using a probe atom at each grid point [2]

- CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis): Compute similarity indices for steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor fields using Gaussian-type functions [2]

Table 2: Comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA Descriptor Methods

| Characteristic | CoMFA | CoMSIA |

|---|---|---|

| Field Types | Steric and electrostatic | Steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor |

| Probe Atoms | sp³ carbon with +1 charge | Various probe atoms for different fields |

| Distance Dependence | Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials | Gaussian-type distance dependence |

| Alignment Sensitivity | Highly sensitive to molecular alignment | More robust to small alignment variations |

| Contour Maps | Steric (green/yellow) and electrostatic (blue/red) | Multiple contour types for different interactions |

| Applicability | Best for congeneric series with reliable alignment | Suitable for structurally diverse datasets |

- Model Building Algorithms:

- Apply Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate field descriptors with biological activity [2]

- Use cross-validation (leave-one-out or leave-group-out) to determine optimal number of components

- Validate model performance using external test set predictions

Advanced AI-Enhanced 3D-QSAR Protocols

Protocol 3.5.1: Machine Learning Integration in 3D-QSAR

Descriptor Enhancement:

Machine Learning Algorithms:

- Implement random forest (RF) for robust, non-linear relationship modeling [6]

- Apply support vector machines (SVM) for high-dimensional descriptor spaces [6]

- Utilize multilayer perceptron (MLP) neural networks for complex, hierarchical patterns [6]

- Employ graph neural networks (GNNs) for direct learning from molecular graphs [5] [7]

Consensus Modeling:

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Software | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | Sybyl-X, RDKit, ChemDraw | 3D structure generation and optimization | Force field optimization, conformer generation, geometry minimization [3] [2] |

| 3D-QSAR Analysis | COMSIA, CoMFA, OpenEye's 3D-QSAR | Field calculation and model development | Steric/electrostatic field computation, PLS regression, contour map generation [4] [8] |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock, GOLD, Glide | Binding mode prediction and alignment guidance | Protein-ligand docking, binding pose prediction, scoring functions [3] [4] |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Validation of 3D-QSAR predictions and stability assessment | Simulation of temporal evolution, binding free energy calculations, stability analysis [3] [4] |

| ADMET Prediction | SwissADME, pkCSM, PreADMET | Pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiling | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity prediction [5] [4] |

| Quantum Chemistry | Gaussian, ORCA, GAMESS | Electronic property calculation and descriptor generation | DFT calculations, molecular orbital analysis, electrostatic potential maps [4] |

Integration with Molecular Dynamics for Validation

MD Simulation Protocol for 3D-QSAR Validation

Protocol 5.1.1: Molecular Dynamics Validation of 3D-QSAR Predictions

System Preparation:

- Build protein-ligand complexes for top predicted compounds and reference molecules

- Solvate systems in appropriate water model (TIP3P, SPC) with counterions for neutrality

- Apply force field parameters (GAFF, CGenFF) for small molecules compatible with protein force field

Simulation Parameters:

- Perform energy minimization using steepest descent and conjugate gradient algorithms

- Equilibrate system with positional restraints on protein and ligands (NVT and NPT ensembles)

- Run production MD simulations for 100-200 ns with 2 fs time step at 300K [3] [4]

- Employ periodic boundary conditions and particle mesh Ewald for long-range electrostatics

Trajectory Analysis:

- Calculate RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) to assess complex stability (fluctuations between 1.0-2.0 Å indicate stable binding) [3]

- Compute RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) to identify flexible regions

- Analyze hydrogen bonding patterns and interaction persistence throughout simulation

- Perform principal component analysis to identify essential dynamics

Binding Free Energy Calculations:

- Apply MM-PBSA/GBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann/Generalized Born Surface Area) methods

- Conduct energy decomposition to identify key residue contributions [3]

- Calculate per-residue decomposition to validate 3D-QSAR contour map interpretations

Case Study: Integrated 3D-QSAR/MD Workflow for MAO-B Inhibitors

A recent study on novel 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamides as monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors demonstrates the powerful integration of 3D-QSAR with molecular dynamics validation [3]. The researchers developed a 3D-QSAR model with excellent predictive ability (q² = 0.569, r² = 0.915) and identified compound 31.j3 as the most promising candidate. Subsequent MD simulations confirmed the stability of the MAO-B-31.j3 complex, with RMSD values fluctuating between 1.0 and 2.0 Å, indicating stable binding. Energy decomposition analysis further revealed the contribution of key amino acid residues to binding energy, validating the steric and electrostatic features identified in the original 3D-QSAR model [3].

Applications and Advanced Implementation

Contemporary Applications in Drug Discovery

Modern 3D-QSAR applications span diverse therapeutic areas and target classes:

- Neurodegenerative Disease Drug Discovery: Development of MAO-B inhibitors for Parkinson's disease treatment using COMSIA-based 3D-QSAR models [3]

- Antidiabetic Agent Development: Design of novel α-glucosidase inhibitors through CoMFA and CoMSIA modeling with MD validation [4]

- Cancer Therapeutics: Identification of aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer treatment using 3D-QSAR combined with molecular docking and ADMET prediction [9]

- Endocrine Disruptor Screening: Prediction of estrogen receptor-binding activity of small molecules using machine learning-based 3D-QSAR models [6]

Best Practices and Implementation Guidelines

Model Quality Assessment:

- Ensure cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) > 0.5 for predictive models

- Maintain conventional correlation coefficient (r²) > 0.8 for model fit

- Achieve predictive r² for test set (r²ₜₑₛₜ) > 0.6 for external validation [4]

- Report standard error of estimate and F-value for model significance

Regulatory Compliance:

- Adhere to OECD principles for QSAR validation: defined endpoint, unambiguous algorithm, defined domain of applicability, appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity

- Document all parameters and procedures for reproducibility

- Provide applicability domain characterization for reliable predictions

Troubleshooting Common Issues:

- Poor Predictive Ability: Revisit molecular alignment, consider alternative bioactive conformations, or apply different descriptor sets

- Overfitting: Reduce descriptor dimensionality, increase training set size, or apply more stringent cross-validation

- Inconsistent Contour Maps: Verify alignment consistency, check for outliers, or explore alternative field calculation methods

The integration of 3D-QSAR with molecular dynamics simulations represents a powerful paradigm in modern drug discovery, enabling both predictive modeling and dynamic validation of compound interactions. This synergistic approach facilitates the rational design of novel therapeutic agents with optimized binding characteristics and improved pharmacological profiles.

The Role of Molecular Dynamics in Capturing Dynamic Biomolecular Processes

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in structural biology and computational drug discovery, providing atomic-level insight into the dynamic biomolecular processes that static structures cannot capture. By predicting the motion of every atom in a molecular system over time, MD simulations reveal how proteins and other biomolecules function, interact with ligands, and undergo conformational changes [10]. The integration of MD with other computational methods, particularly three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling, creates a powerful framework for validating and refining predictive models of biological activity [11] [12] [13]. This integration is crucial for translating static structural predictions into dynamically validated drug candidates, significantly enhancing the reliability of computational screening in the drug development pipeline.

Integrating MD Simulations with 3D-QSAR Workflows

The Complementary Computational Workflow

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, particularly 3D-QSAR approaches like Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), establishes a correlation between the three-dimensional structural features of compounds and their biological activity [11] [12]. However, these models typically rely on a single, static conformation of each molecule. MD simulations address this limitation by providing a dynamic validation of the binding modes and conformational stability predicted by QSAR and molecular docking.

The standard integrated workflow proceeds through several key stages:

- 3D-QSAR Model Development: A predictive model is built using a set of compounds with known activities.

- Activity Prediction & Compound Design: The model predicts activities of novel compounds and guides the design of new candidates.

- Binding Pose Assessment: Molecular docking predicts how these new compounds interact with the target protein.

- Dynamic Validation: MD simulations validate the stability of the docked complexes under physiologically relevant conditions [14] [11] [12].

This workflow ensures that compounds identified as promising by static models are rigorously tested for the stability of their protein-ligand interactions through dynamic simulation.

Protocol for MD Validation of 3D-QSAR Predictions

The following protocol outlines the key steps for using MD simulations to validate potential inhibitors identified through a 3D-QSAR screening campaign.

Step 1: System Preparation

- Obtain the initial coordinates for the protein-ligand complex from molecular docking studies. The ligand is typically the candidate compound identified via 3D-QSAR [14] [11].

- Place the solvated complex in a simulation box with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P water model) and add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system and achieve a physiological salt concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl).

- Assign a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA) to the protein, ligand, and ions [15].

Step 2: Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Perform energy minimization (typically 5,000-50,000 steps) using a steepest descent algorithm to remove any steric clashes introduced during system setup.

- Conduct a two-phase equilibration:

- NVT Ensemble: Heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) using a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover) and run for 50-100 ps while restraining the heavy atoms of the protein-ligand complex.

- NPT Ensemble: Release the restraints and equilibrate the system for 100-500 ps using a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) to achieve the correct density (1 atm pressure) [15].

Step 3: Production MD Simulation

- Run an unrestrained production simulation for a duration sufficient to capture relevant biological processes. For validating a binding pose, simulations of 100 ns to 300 ns are commonly used [14] [12].

- Use a time step of 2 fs, enabled by constraining bonds involving hydrogen atoms.

- Save the atomic coordinates to a trajectory file at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-100 ps) for subsequent analysis.

Step 4: Trajectory Analysis

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Calculate the backbone RMSD of the protein and the heavy-atom RMSD of the ligand to assess the overall stability of the complex and the ligand's binding pose.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Analyze per-residue fluctuations to identify flexible regions of the protein and check if key binding residues remain stable.

- Hydrogen Bonds and Interactions: Monitor the number and stability of specific hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts between the ligand and the protein throughout the simulation [14] [12].

- Binding Free Energy Calculations: Employ methods like Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) to compute the binding free energy, providing a quantitative measure of ligand affinity that validates the 3D-QSAR prediction [12].

Case Studies in Drug Discovery

Identification of MCF-7 Breast Cancer Inhibitors

A seminal study demonstrated this integrated approach by identifying naphthoquinone derivatives as inhibitors of topoisomerase IIα for breast cancer therapy [14]. Six QSAR models were developed using Monte Carlo optimization, which screened 2,300 naphthoquinones. After ADMET filtering, 16 promising compounds were selected for docking. The top candidate, compound A14, was subjected to a 300 ns MD simulation. The simulation confirmed the complex's stability, showing that compound A14 maintained key interactions with the target, thus validating the QSAR predictions and underscoring its potential as a lead compound [14].

Design of MAO-B Inhibitors for Neurodegenerative Diseases

In neurodegenerative disease research, 3D-QSAR (CoMSIA), molecular docking, and MD were used to design new 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives as monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors [11]. The most promising compound, 31.j3, demonstrated a stable binding mode in MD simulations, with RMSD values fluctuating between 1.0 and 2.0 Å, indicating high conformational stability. Energy decomposition analysis further revealed the key residues contributing to binding through van der Waals and electrostatic interactions, dynamically validating the structural features highlighted by the 3D-QSAR model [11].

Development of Anti-Breast Cancer Aromatase Inhibitors

Another study on anti-breast cancer agents designed 1,4-quinone and quinoline derivatives using 3D-QSAR (CoMFA and CoMSIA) and molecular docking [12]. The binding stability of the designed ligands to the aromatase enzyme (3S7S) was confirmed through 100 ns MD simulations. The analysis of RMSD, RMSF, and H-bond parameters, complemented by MM-PBSA calculations, identified ligand 5 as the most promising candidate due to its stable binding profile, leading to its recommendation for experimental testing [12].

Table 1: Key Metrics from MD Simulations in Case Studies

| Case Study | Target Protein | Simulation Duration | Key Stability Metrics | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 Inhibitors [14] | Topoisomerase IIα | 300 ns | Stable RMSD; maintained key interactions | Compound A14 validated as lead |

| MAO-B Inhibitors [11] | Monoamine Oxidase B | Not Specified | RMSD: 1.0-2.0 Å | Compound 31.j3 confirmed stable |

| Aromatase Inhibitors [12] | Aromatase (3S7S) | 100 ns | Stable RMSD/RMSF; favorable MM-PBSA | Ligand 5 selected for testing |

Visualization of Workflows and Processes

Integrated 3D-QSAR and MD Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential, iterative process of integrating 3D-QSAR modeling with MD simulations for dynamic validation in drug discovery.

Key Biomolecular Processes Captured by MD

MD simulations provide critical insights into several dynamic processes that are fundamental to understanding protein-ligand interactions at an atomic level.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful execution of integrated 3D-QSAR and MD studies relies on a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR and MD Simulations

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR Modeling | Sybyl-X [11] | Builds 3D-QSAR models (CoMFA/CoMSIA). | Used to correlate 3D molecular fields with biological activity for predictive design. |

| CORAL [14] | Develops QSAR models using Monte Carlo optimization. | Employs SMILES-based descriptors to predict activity endpoints. | |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock, GOLD, Surflex | Predicts the binding pose and affinity of ligands within a protein's active site. | Generates initial protein-ligand complex structures for MD simulation. |

| MD Simulation & Analysis | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Performs molecular dynamics simulations. | Open-source and commercial software for running production MD; includes energy minimization, equilibration, and trajectory analysis tools. |

| VMD, PyMOL | Visualizes and analyzes MD trajectories. | Critical for inspecting structural stability, interactions, and creating publication-quality figures. | |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA | Provides empirical parameters for calculating potential energy in MD. | The physical model defining atomic interactions; choice depends on the system and software [15]. |

| Hardware | GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) [10] | Accelerates MD calculations. | Makes simulations on biologically relevant timescales (100s of ns) accessible. |

Molecular Dynamics simulations provide the critical link between static predictions and dynamic reality in computational drug discovery. By validating 3D-QSAR models, MD simulations confirm the stability of predicted binding modes, quantify interaction strengths, and ultimately prioritize the most promising lead compounds with a higher probability of experimental success. The continued development of more accurate force fields, faster hardware, and robust automated protocols will further solidify the role of MD as an indispensable component of the modern drug design and validation toolkit.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, particularly three-dimensional QSAR (3D-QSAR), represents one of the most important computational tools in pharmaceutical discovery pipelines. These methods analyze the quantitative relationship between chemical structures and their biological activities using physicochemical or structural parameters [16]. The 3D-QSAR approaches, including Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), introduce three-dimensional structural information to study structure-activity relationships, indirectly characterizing non-bonded interactions between molecules and biomacromolecules [17]. However, these methods provide only a static snapshot of molecular interactions, failing to capture the dynamic nature of biological systems that is crucial for accurate drug design.

While 3D-QSAR models demonstrate impressive statistical parameters in development (typically requiring R² > 0.9 and Q² > 0.5 for internal validation [18]), these metrics alone cannot guarantee predictive reliability for novel compounds. The inherent limitation of these static approaches lies in their treatment of proteins as rigid entities and their inability to account for the temporal evolution of ligand-receptor complexes. This application note establishes the critical scientific rationale for supplementing static 3D-QSAR predictions with Molecular Dynamics (MD) validation, providing detailed protocols for implementation within drug discovery workflows.

The Critical Gap: When 3D-QSAR Predictions Require Experimental Validation

Fundamental Limitations of 3D-QSAR Methodology

3D-QSAR techniques operate on the principle that biological activity correlates with molecular interaction fields surrounding compounds. These methods consider ligand properties calculated in their bioactive conformation, making them theoretically more suitable than classic 2D approaches for studying ligand-receptor interactions [19]. However, several fundamental assumptions limit their predictive accuracy:

- Static Binding Mode Assumption: 3D-QSAR assumes a single, dominant binding conformation without accounting for protein flexibility or alternative binding modes [19] [16].

- Limited Solvation Effects: Implicit solvation models fail to capture specific water-mediated interactions critical to binding.

- Entropic Considerations: These methods largely ignore entropic contributions to binding free energy.

- Time-Independent Properties: 3D-QSAR cannot observe the time evolution of complex stability or interaction persistence.

Statistical Validation Isn't Enough: The Deception of Good Numbers

Robust 3D-QSAR models must meet stringent statistical criteria including:

- Internal validation: Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation with q² > 0.5 [18]

- External validation: R²pred > 0.5 for test set predictions [18]

- Golbraikh and Tropsha criteria: R² > 0.6, 0.85 < k < 1.15, and [(R² - R₀²)/R²] < 0.1 [20] [18]

However, these statistical parameters alone cannot confirm model validity [20]. A comprehensive analysis of 44 published QSAR models revealed that employing the coefficient of determination (r²) alone could not indicate the true validity of a QSAR model, and established validation criteria have specific advantages and disadvantages that must be considered [20]. This underscores that statistical validation represents a necessary but insufficient condition for establishing predictive reliability.

Table 1: Case Studies Demonstrating 3D-QSAR Prediction Gaps Resolved by MD Validation

| Study Focus | 3D-QSAR Results | MD Validation Insights | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAO-B Inhibitors [11] | CoMSIA model with q²=0.569, r²=0.915 predicted IC₅₀ values | MD simulations (100 ns) revealed binding stability, key residue contributions through energy decomposition | Identified stable binding conformation not apparent in static analysis |

| Anti-Breast Cancer Agents [12] | CoMSIA/SEA model indicated electrostatic, steric, H-bond fields significant | 100 ns MD simulations with RMSD, RMSF, SASA, MM-PBSA showed only one designed compound maintained stable binding | Prevented false positive from static prediction alone |

| Ovarian Cancer (AKT1) [21] | 3D-QSAR model with R²=0.822, Q²=0.613 identified potential inhibitors | MD simulations revealed stability issues in physiological conditions, identified taxifolin as truly promising | Uncovered dynamic instability not detected in static approach |

| mIDH1 Inhibitors [17] | CoMFA (R²=0.980, Q²=0.765) and CoMSIA (R²=0.997, Q²=0.770) models built | MD simulations with FEL, Rg, SASA, PSA identified C2 with highest binding free energy (-93.25 ± 5.20 kcal/mol) | Revealed compounds with superior binding properties beyond QSAR predictions |

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Capturing Biological Reality

The Dynamic View of Molecular Interactions

Molecular Dynamics simulations address the fundamental limitations of static approaches by modeling the temporal evolution of molecular systems. MD incorporates:

- Protein flexibility and side-chain rearrangements

- Explicit solvation with water molecules and ions

- Temperature and pressure controls mimicking physiological conditions

- Time-dependent phenomena such as hydrogen bond formation/breakage

MD simulations provide atomic-level insights into biological processes by solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system, typically at femtosecond resolution, over simulation timescales ranging from nanoseconds to microseconds [11] [12].

Complementary Strengths: 3D-QSAR and MD Integration

The integration of 3D-QSAR and MD creates a powerful synergistic workflow:

- 3D-QSAR: Rapidly screens large chemical spaces, identifies critical molecular features, and predicts activity trends

- MD Simulations: Validate binding stability, identify specific atomic interactions, and calculate binding free energies

This combination is particularly valuable for studying mutant protein targets where structural alterations significantly impact dynamics and binding. For example, in ovarian cancer research, MD simulations revealed how a W80R point mutation in AKT1 affected flavonoid binding stability, information inaccessible to static 3D-QSAR methods [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard 3D-QSAR Model Development with CoMFA/CoMSIA

Purpose: To develop predictive 3D-QSAR models for initial activity prediction and pharmacophore mapping.

Materials and Software:

- Molecular Modeling Suite (Sybyl-X, Schrodinger Maestro): For compound building, optimization, and alignment

- Quantum Chemical Software (Gaussian 09): For geometry optimization at DFT level (e.g., M06-2X/6-31G(d,p)) [19]

- Descriptor Calculation Tools (Dragon Software): Generate structural and physicochemical descriptors [19]

- Statistical Analysis Package (QSARINS): For genetic algorithm variable selection and model validation [19]

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation: Collect 30-50 compounds with consistent experimental activity measurements (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) [17]. Ensure structural diversity while maintaining a common scaffold.

- Molecular Alignment: Perform substructure or pharmacophore-based alignment using the most active compound as template [17].

- Descriptor Calculation and Selection:

- Calculate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding field descriptors

- Apply genetic algorithm (population size: 300, mutation rate: 65) for descriptor selection [19]

- Remove cross-correlated descriptors (r ≥ 0.85)

- Model Development:

- Model Application: Predict activities of novel designed compounds and generate contour maps for structure optimization.

Protocol 2: Molecular Dynamics Validation of 3D-QSAR Predictions

Purpose: To validate the stability and binding mechanisms of 3D-QSAR-predicted active compounds through nanosecond-scale simulations.

Materials and Software:

- MD Simulation Engine (GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD): For running dynamics simulations

- Force Field Parameters (CHARMM36, AMBER ff14SB, OPLS-AA): Determine atom interactions and energetics

- Visualization Software (VMD, PyMol): For trajectory analysis and figure generation

- Free Energy Calculation Tools (MM-PBSA, MM-GBSA): For binding affinity quantification

Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain protein structure from PDB or homology modeling

- Parameterize ligands using antechamber/GAFF

- Solvate in explicit water (TIP3P) with neutralizing ions (0.15 M NaCl)

- Energy Minimization:

- Perform steepest descent minimization (5,000 steps) until Fmax < 1000 kJ/mol/nm

- Equilibration Phases:

- NVT equilibration (100 ps, 300 K, Berendsen thermostat)

- NPT equilibration (100 ps, 1 bar, Parrinello-Rahman barostat)

- Production MD:

- Run unrestrained simulation (50-100 ns) with 2 fs time step

- Apply periodic boundary conditions and PME for electrostatics

- Trajectory Analysis:

- Calculate RMSD (backbone stability), RMSF (residue flexibility), Rg (compactness)

- Monitor hydrogen bonds and interaction persistence

- Perform energy decomposition to identify key residue contributions [11]

- Binding Free Energy Calculations:

- Apply MM-PBSA/GBSA on 100-500 evenly spaced frames from stable trajectory region

- Calculate van der Waals, electrostatic, polar, and non-polar solvation components

Table 2: Key Parameters for MD Validation of 3D-QSAR Predictions

| Validation Metric | Target Range | Interpretation | Computational Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD (Protein Backbone) | < 2.0-3.0 Å | System stability and equilibration | GROMACS, CPPTRAJ |

| RMSF (Residue) | < 1.5 Å (core), < 3.0 Å (loops) | Regional flexibility and binding effects | VMD, Bio3D |

| Hydrogen Bonds | Consistent count (±1-2) | Specific interaction maintenance | VMD, MDAnalysis |

| Radius of Gyration (Rg) | Stable fluctuations < 0.5 Å | Global structural compactness | GROMACS |

| MM-PBSA Binding Energy | Negative value (more negative = better) | Quantitative binding affinity | MMPBSA.py, g_mmpbsa |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) | Stable with minor fluctuations | Burial of hydrophobic surfaces | GROMACS, VMD |

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR and MD Workflows

| Reagent/Software Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Suites | Sybyl-X, Schrodinger Maestro, OpenBabel | Compound building, optimization, conformational analysis, and alignment for 3D-QSAR |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Gaussian 09, ORCA, GAMESS | Geometry optimization and electronic property calculation at DFT/ab initio levels |

| Descriptor Calculation Tools | Dragon Software, PaDEL-Descriptor | Generation of structural, topological, and physicochemical descriptors for QSAR |

| Statistical Analysis Software | QSARINS, SIMCA, R | Model development, variable selection, and statistical validation |

| MD Simulation Engines | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM | Running molecular dynamics simulations with various force fields |

| Force Field Parameters | CHARMM36, AMBER ff14SB, OPLS-AA, GAFF | Defining atomistic interactions, bonding, and non-bonded parameters |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | VMD, PyMol, MDAnalysis, CPPTRAJ | Visualization, measurement, and analysis of MD trajectories |

| Free Energy Calculators | MMPBSA.py, g_mmpbsa, WHAM | Binding free energy calculations from MD trajectories |

Workflow Integration: From Static Prediction to Dynamic Validation

The sequential application of 3D-QSAR and MD simulations creates a powerful workflow for rational drug design. The process begins with 3D-QSAR to rapidly explore chemical space and identify promising candidates, followed by MD validation to confirm binding stability and mechanism.

Integrated 3D-QSAR and MD Validation Workflow

This integrated approach efficiently leverages the strengths of both methodologies: the high-throughput screening capability of 3D-QSAR and the biological fidelity of MD simulations. The workflow ensures that only compounds demonstrating both favorable predicted activity and stable binding dynamics advance to resource-intensive experimental stages.

The integration of Molecular Dynamics simulations with 3D-QSAR predictions represents a paradigm shift in computational drug design, moving beyond static structural approximations to embrace the dynamic reality of biological systems. This approach addresses fundamental limitations of standalone 3D-QSAR methods, providing critical insights into:

- Temporal stability of ligand-receptor complexes

- Specific interaction mechanisms at atomic resolution

- Energetic contributions of individual residues to binding

- Structural adaptations and conformational changes upon binding

As MD methodologies continue to advance with specialized hardware, enhanced sampling algorithms, and machine learning integration, the accessibility and timescales of simulations will further improve. The scientific community increasingly recognizes that comprehensive validation protocols combining multiple computational approaches provide the most reliable path to efficient therapeutic development. For research teams investing in computational drug discovery, the 3D-QSAR/MD validation framework represents not merely an enhancement, but an essential component of robust, predictive molecular design.

This application note details the critical components for constructing reliable computational models in drug design, framed within a research context that utilizes molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to validate 3D-QSAR predictions. We provide a structured overview of key molecular descriptors and force fields, followed by a standardized protocol for their application.

Table of Key Molecular Descriptor Classes

Table 1: Categories of molecular descriptors critical for building accurate machine learning and QSAR models.

| Descriptor Class | Key Examples | Description | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Interatomic Descriptors | Coulomb Matrix, Inverse Interatomic Distances [22] | Encodes all pairwise atomic interactions within a molecule, providing a complete global representation. | Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) for molecular dynamics [22] |

| Reduced/Feature-Selected Descriptors | Automatized Reduced Descriptors [22] | A minimized set of features selected automatically from a global descriptor to maintain accuracy while improving computational efficiency. | Efficient MLFFs for large, flexible molecules like peptides and DNA [22] |

| 3D-QSAR Field Descriptors | Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) Fields [11] | Describes 3D molecular fields (steric, electrostatic, etc.) surrounding aligned molecules in a dataset. | 3D-QSAR models for predicting biological activity (e.g., IC50) [11] |

Force fields are computational models that describe the potential energy of a system of atoms and molecules, enabling the calculation of forces for molecular dynamics simulations [23]. The basic functional form for an additive force field is:

( E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{nonbonded}} )

Where:

- ( E{\text{bonded}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{dihedral}} ) [23]

- ( E{\text{nonbonded}} = E{\text{electrostatic}} + E_{\text{van der Waals}} ) [23]

Experimental Protocol: Integrating 3D-QSAR and MD Simulations for Model Validation

The following protocol describes a workflow for developing a predictive model and validating its binding modes using molecular dynamics simulations, as applied in studies of Monoamine Oxidase-B (MAO-B) and Thyroid Peroxidase (TPO) inhibitors [11] [24].

Workflow Diagram: 3D-QSAR & MD Validation Pipeline

Phase 1: 3D-QSAR Model Development & Validation

Compound Dataset Curation

Structure Optimization and Conformer Generation

- Use software like ChemDraw and Sybyl-X to build and optimize 3D molecular structures [11].

- Generate low-energy conformers for each compound.

Molecular Docking and Alignment

3D-QSAR Model Construction

Model Validation

- Internal Validation: Use the Leave-One-Out (LOO) method to obtain cross-validated correlation coefficient ((q^2)). A robust model typically has (q^2 > 0.5) [18].

- External Validation: Predict the activity of the test set compounds. A model with high predictive power should have a predictive (R^2) ((R^2_{\text{pred}})) > 0.5 and a low mean absolute error (MAE) [18].

Phase 2: Model Exploitation and MD Validation

Design and Virtual Screening

- Design novel derivatives based on the 3D-QSAR contour maps.

- Use the validated model to predict the activities of the newly designed compounds [11].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Setup

- Select the top-scoring compound(s) from docking and QSAR prediction.

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in an explicit water box (e.g., TIP3P water model) and add ions to neutralize the system.

- Use a force field such as CHARMM36, GAFF, or a Neural Network Potential (NNP) to describe atomic interactions [25] [26].

- Employ software like NAMD (integrated in BIOVIA Discovery Studio) or GROMACS for simulations [26].

MD Simulation Execution

- Energy-minimize the system to remove steric clashes.

- Gradually heat the system to the physiological temperature (e.g., 310 K) under an NVT ensemble.

- Equilibrate the system with pressure coupling (NPT ensemble) to achieve correct density.

- Run a production MD simulation for a sufficient duration (e.g., 100 ns to 1 µs) to assess stability [11] [27] [24].

Trajectory Analysis and Binding Free Energy Calculation

- Stability Analysis: Calculate the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone and ligand. Fluctuations between 1.0-2.0 Å indicate a stable complex [11].

- Interaction Analysis: Identify key residue interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) that persist during the simulation.

- Energy Decomposition: Perform energy decomposition analysis (e.g., using MM/GBSA) to reveal the contribution of specific residues to binding, highlighting the role of van der Waals and electrostatic interactions [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key software, force fields, and computational tools required for the described protocols.

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Sybyl-X | Molecular modeling and 3D-QSAR software suite. | Used for structure optimization, molecular alignment, and CoMSIA model construction [11]. |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio | Software providing simulation and analysis tools. | Used for MD simulations leveraging integrated CHARMm and NAMD engines [26]. |

| CHARMM Force Field | A family of all-atom force fields for proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. | Used to parametrize the protein and standard organic molecules during MD setup [26]. |

| CGenFF | CHARMM General Force Field for drug-like molecules. | Used to generate parameters for novel ligands [26]. |

| Neural Network Potential (NNP) | Machine-learning-based force field for high accuracy. | Can be used in MD protocols for more precise prediction of material properties (e.g., thermal stability) [25]. |

| GAFF (General AMBER Force Field) | A force field for organic molecules, parameters often derived via DFT. | Used to describe radiometal-chelator complexes in MD simulations [27]. |

| Water Models (e.g., TIP3P) | Explicit solvent models representing water molecules. | Used to solvate the protein-ligand complex in a biologically relevant environment [26]. |

Statistical Validation Criteria for 3D-QSAR Models

For a 3D-QSAR model to be considered reliable and predictive, it must meet several statistical criteria as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Key statistical parameters for evaluating the quality of 3D-QSAR models [18].

| Validation Type | Parameter | Threshold for a Predictive Model |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation | LOO cross-validated (q^2) | > 0.5 |

| Internal Validation | Non-cross-validated (r^2) | > 0.9 |

| External Validation | Predictive (R^2) ((R^2_{\text{pred}})) | > 0.5 |

| External Validation | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | ≤ 0.1 × training set activity range |

A Practical Workflow: Integrating MD Simulations into Your 3D-QSAR Pipeline

Building and Validating a Predictive 3D-QSAR Model (e.g., CoMSIA)

This application note provides a detailed protocol for building and validating a predictive Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) model, specifically using the Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) method. Within the broader context of a research thesis integrating molecular dynamics simulations, a robust 3D-QSAR model serves as the critical initial step for identifying and optimizing potential lead compounds in drug discovery [28] [12]. The model establishes a quantitative relationship between the three-dimensional molecular interaction fields of a compound set and their corresponding biological activities, enabling the prediction of activities for novel compounds and providing visual guidance for rational molecular design [2]. The subsequent validation of these predictions through molecular dynamics simulations ensures their reliability and biological relevance, creating a powerful combined computational approach.

The entire process, from data preparation to model application, follows a structured workflow to ensure the generation of a statistically robust and predictive model. The following diagram outlines the key stages of this protocol:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Data Collection and Curation

The foundation of a reliable 3D-QSAR model is a high-quality, consistent dataset.

- Activity Data: Assemble a congeneric series of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀, EC₅₀, pIC₅₀). A minimum of 20-30 compounds is typically required for meaningful statistical analysis [2]. The pIC₅₀ value (-logIC₅₀) is often used as the dependent variable to linearize the relationship with free energy changes [18].

- Data Integrity: All biological activity data must be acquired under uniform experimental conditions to minimize noise and systematic bias [2]. The dataset should be divided into a training set (typically ~80% of compounds) for model construction and a test set (the remaining ~20%) for external validation of predictive ability [18] [12].

Molecular Modeling and Alignment

This step transforms 2D molecular structures into their bioactive 3D conformations and aligns them for comparative analysis.

- 3D Structure Generation: Convert 2D structures into 3D coordinates using molecular modeling software (e.g., Sybyl, MOE, RDKit) [11] [2].

- Geometry Optimization: Minimize the energy of the initial 3D structures using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., Tripos, OPLS_2005, UFF) or quantum mechanical methods to achieve realistic, low-energy conformations [28] [2].

- Molecular Alignment: This is a critical step that significantly impacts model quality. Align all molecules onto a common 3D reference frame based on a presumed bioactive conformation. Common strategies include:

- Pharmacophore-Based Alignment: Superimpose molecules based on key pharmacophoric features.

- Database Alignment: Use the structure of a potent compound or a common scaffold (e.g., Bemis-Murcko scaffold) as a template for alignment [2].

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS): Identify and align the largest common substructure shared across the dataset [2].

CoMSIA Descriptor Calculation

The CoMSIA method characterizes molecules based on their similarity to a probe atom at regularly spaced grid points surrounding the aligned molecules. Unlike CoMFA, CoMSIA uses Gaussian-type functions to avoid singularities and offers additional field types [2].

- Protocol: Using CoMSIA module in software like Sybyl, calculate five distinct molecular interaction fields:

- Steric (S): Represents van der Waals interactions and molecular bulk.

- Electrostatic (E): Represents Coulombic potential.

- Hydrophobic (H): Characterizes lipophilicity.

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (D): Represents the ability to donate a hydrogen bond.

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (A): Represents the ability to accept a hydrogen bond.

- A probe atom (typically a sp³ hybridized carbon with a +1 charge) is placed at each grid point, and the similarity indices are computed using a Gaussian function, which makes the calculation less sensitive to minor alignment deviations compared to CoMFA [2].

Model Building with Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression

The high number of CoMSIA descriptors (independent variables) relative to the number of compounds requires a dimensionality reduction technique.

- Protocol: Employ the Partial Least Squares (PLS) algorithm to correlate the CoMSIA descriptors (X-matrix) with the biological activity data (Y-matrix, e.g., pIC₅₀) [18] [2].

- Cross-Validation: Perform Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation with the training set to determine the optimal number of components (ONC) that maximizes predictive ability while minimizing the risk of overfitting. The ONC is the number of latent variables that yields the highest cross-validated correlation coefficient, q² [18].

- Final Model: A final model is then generated using the optimal number of components on the entire training set, yielding the conventional correlation coefficient, r² [18].

Model Validation and Interpretation

A model must be rigorously validated before it can be used for prediction.

- Internal Validation: Assess the model's self-consistency and internal predictive ability.

- External Validation: This is the gold standard for evaluating predictive power. Use the model to predict the activity of the external test set compounds that were not used in model building [18] [12].

- Contour Map Analysis: Visualize the CoMSIA results by generating 3D contour maps. These maps highlight regions in space where specific molecular properties favor or disfavor biological activity, providing a powerful tool for medicinal chemists [2]. For example:

- Green contours: Regions where bulky groups increase activity.

- Yellow contours: Regions where bulky groups decrease activity.

- Blue contours: Regions where electropositive groups increase activity.

- Red contours: Regions where electronegative groups increase activity.

The following diagram summarizes the key stages and decision points in the model validation process:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 1: Essential Software and Tools for 3D-QSAR Modeling

| Tool/Software | Type | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Sybyl-X [11] | Commercial Software Suite | Integrated environment for molecular modeling, CoMFA/CoMSIA analysis, PLS regression, and contour map visualization. |

| Open3DALIGN [2] | Open-Source Tool | Automated molecular alignment, a critical and often challenging step in the 3D-QSAR workflow. |

| RDKit [28] [2] | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Python library used for 2D to 3D structure conversion, geometry optimization, and maximum common substructure (MCS) alignment. |

| Python/Scikit-learn [28] | Programming Environment | Custom scripting for data preprocessing, advanced machine learning model building, and hyperparameter tuning beyond traditional PLS. |

| GROMACS/AMBER | Molecular Dynamics Software | Used in the broader thesis context for validating 3D-QSAR predictions via molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations. |

Application in a Thesis Integrating Molecular Dynamics Simulations

In a thesis focused on molecular dynamics (MD) to validate 3D-QSAR predictions, the CoMSIA model serves as the starting point for a multi-stage computational investigation.

- Prediction and Design: The validated CoMSIA model is used to predict the activity of virtual compounds and guide the design of new derivatives with improved predicted potency [12] [29]. The contour maps provide specific structural guidance, such as suggesting the introduction of a bulky hydrophobic group in a green-contoured region.

- Molecular Docking: The highest-ranked newly designed compounds are then subjected to molecular docking studies to predict their binding mode and key interactions with the target protein's active site [11] [12].

- Molecular Dynamics Validation: This is the core validation step in the thesis context. The top ligand-receptor complexes from docking are simulated using MD (e.g., for 100 ns) to assess the stability of the predicted binding poses under dynamic, physiological-like conditions [11] [12]. Key analyses include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Confirms the overall stability of the protein-ligand complex.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies flexible regions in the protein upon ligand binding.

- Hydrogen Bond Analysis: Quantifies persistent key interactions.

- MM-PBSA/GBSA Calculations: Estimates the binding free energy, providing a quantitative measure of binding affinity that can be correlated with the 3D-QSAR predictions [12]. A stable MD trajectory with a favorable computed binding energy provides strong corroborative evidence for the 3D-QSAR model's prediction.

Case Studies and Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes the performance of CoMSIA models from recent literature, demonstrating the typical outputs and benchmarks of a successful study.

Table 2: Exemplary Performance Metrics from Published 3D-QSAR CoMSIA Studies

| Study Focus | Statistical Parameters | Outcome and Validation |

|---|---|---|

| MAO-B Inhibitors [11] | q² = 0.569, r² = 0.915, SEE = 0.109, F = 52.714 | The model guided the design of new derivatives, with the top compound showing stable binding in MD simulations (RMSD 1.0-2.0 Å). |

| LSD1 Inhibitors [29] | q² = 0.728, r² = 0.982, Rₚᵣₑ𝒹² = 0.814 | The model demonstrated high predictive power for an external test set, leading to the design of novel inhibitors with predicted nanomolar activity. |

| Anti-Breast Cancer Agents [12] | CoMSIA/SEA model identified key electrostatic, steric, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields. | The model was used to design new compounds, with the top candidate subjected to 100 ns MD simulations confirming binding stability via RMSD, RMSF, and MM-PBSA. |

| Antioxidant Peptides (ML-enhanced) [28] | Traditional PLS: R² = 0.755, R²test = 0.575GB-RFE/GBR: R² = 0.872, R²test = 0.759 | Highlights the potential of machine learning (Gradient Boosting) to build more predictive CoMSIA models compared to traditional PLS, mitigating overfitting. |

The transition from a static, predictive Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model to a dynamic, physiologically relevant molecular simulation is a critical step in modern computational drug discovery. While 3D-QSAR models provide invaluable insights into the structural and electrostatic features governing biological activity, they operate on a static representation of reality. Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations bridge this gap, offering a temporal dimension that can validate QSAR predictions by revealing the stability, conformational flexibility, and fundamental binding mechanics of a ligand-receptor complex. This protocol details the systematic preparation of molecular systems for MD, ensuring that the dynamic validation of QSAR hypotheses is built upon a robust and reliable foundation. The process is framed within a broader research thesis aiming to correlate 3D-QSAR contour maps with dynamic binding interactions observed over multi-nanosecond timescales.

Preparing the Ligand-Receptor Complex for Dynamics

The initial setup of the ligand-receptor complex is paramount, as errors introduced at this stage can propagate and compromise the entire simulation. This phase involves translating the most promising QSAR predictions into a three-dimensional, fully parameterized system solvated in a biologically relevant environment.

Initial System Construction and Optimization

The journey from QSAR to MD begins with the construction and energetic refinement of the molecular components.

- Ligand Preparation: The most active compounds identified from the QSAR model, typically in 2D format, must be converted into accurate 3D structures. This can be achieved using chemical drawing software like ChemDraw Ultra 8.0, after which the 3D geometries are energetically minimized. Common protocols use the MM2 and MOPAC algorithms with a root-mean-square (rms) gradient of 0.001 to ensure stable starting conformations [30].

- Receptor Preparation: The 3D structure of the target protein is obtained from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB). This structure must be prepared by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states at physiological pH, and fixing any missing residues. Software suites like Sybyl-X and BIOVIA Discovery Studio offer specialized tools for this purpose [3] [26].

- Complex Assembly: The optimized ligand is docked into the protein's active site to form the initial complex. Docking engines such as CDOCKER can be used for flexible ligand docking and pose refinement [26]. The resulting docked pose, which should be consistent with the steric and electrostatic fields of the 3D-QSAR model, serves as the starting point for MD system preparation.

Force Field Parameterization and Solvation

A physically accurate simulation requires that all system components be described by a suitable force field and placed in an explicit solvent environment.

- Force Field Assignment: A molecular mechanics force field defines the potential energy functions and parameters for the system. The protein and standard residues are typically assigned parameters from well-established force fields like CHARMm36 or CGenFF available within Discovery Studio [26]. For novel ligand molecules, tools like the MATCH method are used to assign atom types and partial charges that are consistent with the chosen force field.

- Solvation and Ionization: The ligand-receptor complex is then placed in an explicit solvent box, such as the TIP3P water model. The size of the box should ensure a sufficient buffer (e.g., 10 Å) between the solute and the box edges to prevent artificial self-interaction. To mimic physiological ionic strength, ions (e.g., Na⁺ and Cl⁻) are added to the system, often replacing solvent molecules to achieve a neutral net charge. Discovery Studio provides fast explicit aqueous solvation methods, including the option to add counter-ions, suitable for very large systems [26].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for System Preparation and Simulation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Software/Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Software | Constructs, visualizes, and optimizes 2D/3D molecular structures. | ChemDraw Ultra 8.0 [30], Sybyl-X [3] |

| Force Field | Defines potential energy functions for molecular interactions. | CHARMm, CHARMm36, CGenFF [26] |

| Parameterization Tool | Assigns force field atom types and charges for novel ligand molecules. | MATCH [26] |

| Solvation Tool | Embeds the solute in an explicit solvent box and adds ions for physiological realism. | BIOVIA Discovery Studio [26] |

| Simulation Engine | Performs the energy minimization, equilibration, and production MD simulations. | NAMD, OpenMM (via drMD) [31] [26] |

| Analysis Suite | Analyzes MD trajectories to compute properties like RMSD, RMSF, and binding free energy. | BIOVIA Discovery Studio [26] |

Workflow for System Preparation and Simulation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from the initial QSAR model to the final production MD simulation, highlighting the critical preparation steps.

A Practical Protocol: From a QSAR Prediction to an MD-Ready System

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step application note for preparing a molecular system, using a hypothetical PfDHODH inhibitor identified from a QSAR study as an example [30].

System Setup and Minimization

Objective: To construct, parameterize, and energetically minimize a stable complex of a 3,4-Dihydro-2H,6H-pyrimido[1,2-c][1,3]benzothiazin-6-imine derivative bound to PfDHODH, ready for equilibration.

Materials:

- Software: BIOVIA Discovery Studio [26] or the drMD pipeline [31].

- Force Field: CHARMm36 [26].

- Ligand: The 2D structure of the QSAR-identified lead compound (e.g., Compound 31 from [30]).

- Receptor: The crystal structure of PfDHODH (e.g., PDB ID 6EFD).

Methodology:

- Ligand Preparation: Convert the 2D ligand structure into a 3D model. Subject it to energy minimization using the MM2/MOPAC algorithms until an rms gradient of 0.001 is reached, generating a stable low-energy conformation [30].

- Receptor Preparation: Load the PfDHODH structure. Use the protein preparation tools to add hydrogen atoms, predict residue pKa values for correct protonation states, and remove crystallographic water molecules unless they are part of a known catalytic mechanism.

- Complex Formation: Dock the minimized ligand into the PfDHODH active site using the CDOCKER protocol [26]. Select the top-ranked pose that best aligns with the steric and electrostatic requirements of the founding QSAR model for subsequent steps.

- System Building: Use the "Solvate" module to embed the protein-ligand complex in a cubic box of TIP3P water molecules, maintaining a minimum distance of 10 Å from the box edges. Add Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions to a concentration of 0.15 M and neutralize the system.

- Energy Minimization: Run a two-stage minimization protocol to relieve any atomic clashes introduced during solvation and system building:

- Stage 1: Minimize only the positions of the hydrogen atoms (500 steps Steepest Descent).

- Stage 2: Minimize the entire system (1000 steps Steepest Descent followed by 1000 steps Conjugate Gradient).

Equilibration and Production

Objective: To gradually bring the minimized system to the target temperature and pressure, and then run a production simulation for data collection.

Methodology:

- System Heating: Under NVT conditions (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature), gradually heat the system from 0 K to 310 K over 100 ps, using a Langevin thermostat. Restrain the heavy atoms of the protein and ligand to allow the solvent to equilibrate around the solute.

- Density Equilibration: Switch to NPT conditions (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) and run a 200 ps simulation at 310 K and 1 atm, using a Langevin barostat. Keep the restraints on the protein and ligand heavy atoms.

- Unrestrained Equilibration: Perform a final 500 ps NPT simulation with all restraints removed, allowing the entire system to relax. Monitor the potential energy, temperature, and density of the system until they stabilize, indicating equilibrium has been reached.

- Production MD: Launch an unconstrained production simulation in the NPT ensemble at 310 K and 1 atm for a duration sufficient to capture the biological phenomenon of interest (e.g., 100 ns to 1 µs). Configure the simulation to save trajectory frames every 10-100 ps for subsequent analysis.

Table 2: Key Parameters for MD Simulation Stages

| Simulation Stage | Ensemble | Duration | Temperature Control | Pressure Control | Restraints on Protein/Ligand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Minimization | N/A | ~2500 steps | N/A | N/A | None |

| System Heating | NVT | 100 ps | Langevin (0 K → 310 K) | N/A | Heavy atoms |

| Density Equilibration | NPT | 200 ps | Langevin (310 K) | Langevin (1 atm) | Heavy atoms |

| Unrestrained Equilibration | NPT | 500 ps | Langevin (310 K) | Langevin (1 atm) | None |

| Production MD | NPT | 100+ ns | Langevin (310 K) | Langevin (1 atm) | None |

Expected Outcomes and Analysis for QSAR Validation

A successfully prepared and simulated system will yield a stable trajectory that can be analyzed to validate QSAR predictions.

- Stability Metrics: The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone and the ligand should converge and fluctuate within a stable range (e.g., 1-3 Å), indicating the complex has reached a stable conformational state. For instance, a well-prepared PfDHODH-inhibitor complex should show RMSD values remaining within an acceptable range, indicating stable interactions [30].

- Interaction Analysis: The simulation trajectory should be analyzed for the formation and persistence of key hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and salt bridges. The specific amino acids involved in these interactions, as identified in the molecular docking study, should remain engaged throughout the simulation, providing dynamic evidence for the binding mode predicted by the static models.

- Free Energy Calculations: Advanced techniques like Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) or free energy perturbation (FEP), available in packages like Discovery Studio [26], can be used to calculate the binding free energy. A strongly negative ΔGbind provides quantitative validation of the ligand's potency, which was initially predicted qualitatively by the QSAR model.

Within the framework of a thesis focused on validating 3D-QSAR predictions, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a critical bridge between static structural models and biological reality. While 3D-QSAR can predict biological activity from ligand structure, and molecular docking can generate putative binding poses, MD simulations provide the means to rigorously test the stability and physical plausibility of these predicted complexes over time in a near-physiological environment [24] [32]. Running and monitoring these simulations effectively is therefore essential for assessing whether a computationally designed or identified ligand remains bound to its target, a key determinant of its potential efficacy as a drug candidate. This protocol details the practical steps for executing and monitoring MD simulations to evaluate binding stability, a cornerstone for establishing a credible link between QSAR predictions and experimental outcomes.

Key Concepts and Relevance to 3D-QSAR Validation

The integration of MD simulations into a 3D-QSAR workflow addresses a fundamental limitation of static modeling: the lack of dynamic and entropic considerations. The primary objectives of this step are:

- Pose Stability Validation: To determine if the docking pose predicted for a potent ligand (as suggested by 3D-QSAR) is stable over the simulation time or undergoes significant conformational changes that would invalidate the initial model.

- Binding Affinity Corroboration: To provide qualitative and quantitative insights into binding strength through the analysis of interaction persistence, energy calculations, and the compactness of the complex.

- Identification of Critical Interactions: To uncover key residue-specific interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and salt bridges, that sustain the binding and may not be fully apparent in the static docking pose [32] [33].

As demonstrated in a study on flavonoids as Bcl-2 family protein inhibitors, a reliable 3D-QSAR model (with R² and Q² of 0.91 and 0.82, respectively) was followed by MD simulations. These simulations confirmed that residues like Phe97, Tyr101, Arg102, and Phe105 formed stable hydrophobic interactions with the most active ligands, thereby validating and providing a structural basis for the QSAR predictions [32].

Experimental Protocol

System Setup and Minimization

A properly prepared system is a prerequisite for a stable and meaningful MD simulation.

- Solvation: Place the protein-ligand complex (from docking) in a simulation box (e.g., a cubic or rectangular box) and solvate it with explicit water molecules, such as the TIP3P water model. The box size should ensure a minimum distance of, for example, 10-12 Å between the solute and the box edges.

- Neutralization: Add ions (e.g., Na⁺ or Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's net charge. Additional ions can be added to mimic physiological salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization to remove any steric clashes or unfavorable contacts introduced during the solvation and ionization process. This is typically done in two steps:

- Minimize the positions of the solvent molecules and ions while restraining the heavy atoms of the protein-ligand complex.

- Perform a full minimization of the entire system without restraints.

- Tools like CHARMM-GUI [34] and BIOVIA Discovery Studio [26] can automate much of this setup process, ensuring best practices are followed.

Equilibration

Gradually relax the minimized system and bring it to the desired temperature and density.

- Heating: Heat the system from a low initial temperature (e.g., 0 K or 100 K) to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K for biological systems) over 50-100 ps while applying positional restraints to the protein and ligand heavy atoms. This allows the solvent to equilibrate around the solute.

- Density Equilibration: Run a short simulation (e.g., 100-500 ps) at constant temperature and pressure (NPT ensemble) to adjust the density of the system to the correct value, still with restraints on the solute.

Production MD Simulation

This is the main simulation phase where data for analysis is collected.

- Run Unrestrained Simulation: Initiate a production run with all restraints removed. The length of this simulation depends on the system and scientific question, but for initial binding stability assessment, a range of 100 ns to 1000 ns is common in contemporary studies [24] [33] [35].

- Configure Parameters: Use an integration time step of 2 fs. Maintain temperature and pressure using algorithms like Langevin dynamics or Nosé-Hoover, and Parrinello-Rahman barostat, respectively. Trajectory coordinates should be saved at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-100 ps) for subsequent analysis.

Simulation Monitoring in Real-Time

It is crucial to monitor simulations as they run to detect instabilities or errors early. Key metrics to track in real-time include:

- Potential Energy: Should be stable and negative, indicating a properly functioning simulation.

- Temperature and Pressure: Should fluctuate around their set-point averages.

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): The RMSD of the protein backbone and the ligand heavy atoms relative to the starting structure can be calculated on-the-fly. A plateau in RMSD suggests the system has reached a stable state, whereas continuous large drifts may indicate unfolding or unstable binding.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Per-residue RMSF can be monitored to identify regions of high flexibility.

Table 1: Essential Real-Time Monitoring Metrics and Their Interpretation

| Metric | Description | Target/Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Potential Energy | Total potential energy of the system. | Should be stable and negative. |

| Temperature | Average kinetic energy of the system. | Should fluctuate around the set value (e.g., 310 K). |

| Pressure | Internal pressure of the system. | Should fluctuate around the set value (e.g., 1 bar). |

| Protein Backbone RMSD | Measures structural drift of the protein. | Should plateau, indicating convergence. |

| Ligand Heavy Atoms RMSD | Measures stability of the ligand in the binding pocket. | A low, stable value indicates stable binding. |

Post-Simulation Analysis for Binding Stability

After completing the production run, a comprehensive analysis of the trajectory is performed to assess binding stability.

Trajectory Analysis

- Overall Stability: Calculate the RMSD of the protein's Cα atoms and the ligand's heavy atoms over the entire trajectory relative to the starting structure. A stable complex will show a plateau in both RMSDs after an initial equilibration period.

- Local Flexibility: Calculate the RMSF for each residue. This helps identify flexible loops and regions. Importantly, it can show if residues in the binding site become more or less flexible upon ligand binding.

- Binding Site Compactness: Monitor the Radius of Gyration (Rg) of the protein, which measures its overall compactness. A stable fold will have a relatively constant Rg. The Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) of the binding pocket can also indicate stability, with a stable complex showing minimal fluctuation in SASA.

- Specific Interactions:

- Hydrogen Bonds: Count the number of hydrogen bonds between the protein and ligand over time. Persistent H-bonds are often critical for stable binding.

- Hydrophobic Contacts & Salt Bridges: Analyze the persistence of non-polar contacts and ionic interactions, which are key drivers of binding affinity.

Energetic and Advanced Analysis

- Binding Free Energy Calculation: Use methods like Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) or MM/PBSA to estimate the binding free energy of the complex. Although absolute values can have significant error, the relative ranking of ligands often correlates well with experimental data [33]. As demonstrated in a study on DNA topoisomerase-IA, MM/GBSA revealed a significantly stronger binding free energy for a complex stabilized by Mg²⁺ compared to Na⁺, with a net difference of -404.2 kcal/mol [33].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): PCA can be used to identify the large-scale, collective motions dominating the simulation. A study on topoisomerase showed that the presence of the correct metal ion (Mg²⁺) led to a 37% reduction in these conformational motions, indicating enhanced stability [33].

- Umbrella Sampling: For a more rigorous quantification, umbrella sampling can be used to calculate the potential of mean force (PMF) and obtain the absolute binding free energy. This was used in a study of the antibiotic oritavancin to characterize its binding to peptidoglycan, showing the enhanced binding was due to increased hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions [35].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Post-Simulation Analysis of Binding Stability

| Analysis Type | Metric | Indication of Stable Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Structural | Protein/Ligand RMSD | Low value that plateaus over time (e.g., ~2.5-3.2 Å for protein [33]). |

| Ligand RMSF | Low fluctuations for ligand atoms, especially those making key interactions. | |

| Energetic | MM/GBSA Binding Energy | A large, negative value (e.g., -404.2 kcal/mol for a stable system vs. a control [33]). |

| Interactions | Hydrogen Bond Count | Consistent number of specific H-bonds maintained throughout the simulation (e.g., >20 vs. ~15 in a less stable system [33]). |

| System Properties | Radius of Gyration (Rg) | Stable value, indicating no major unfolding or compaction. |

| SASA (Binding Pocket) | Low fluctuation, indicating a consistently buried binding interface. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for running and analyzing MD simulations to assess binding stability, integrating the setup, production, and analysis phases detailed in this protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Tools for MD Simulations

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM-GUI [34] | Web-based platform | Interactive input generator for MD simulations. | Streamlines system setup (solvation, ionization) for various simulation packages (CHARMM, NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, etc.). |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio [26] | Commercial Software Suite | Integrated environment for simulation and analysis. | Provides access to simulation engines (CHARMm, NAMD), GaMD for enhanced sampling, and tools for binding energy calculations (MM/GBSA). |

| AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD [34] [26] | MD Simulation Engines | Core programs to run energy minimization and MD simulations. | High-performance engines that execute the calculations defined in the input files prepared during setup. |