Integrating 3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking for Novel Tubulin Inhibitors: A Computational Framework for Anticancer Drug Design

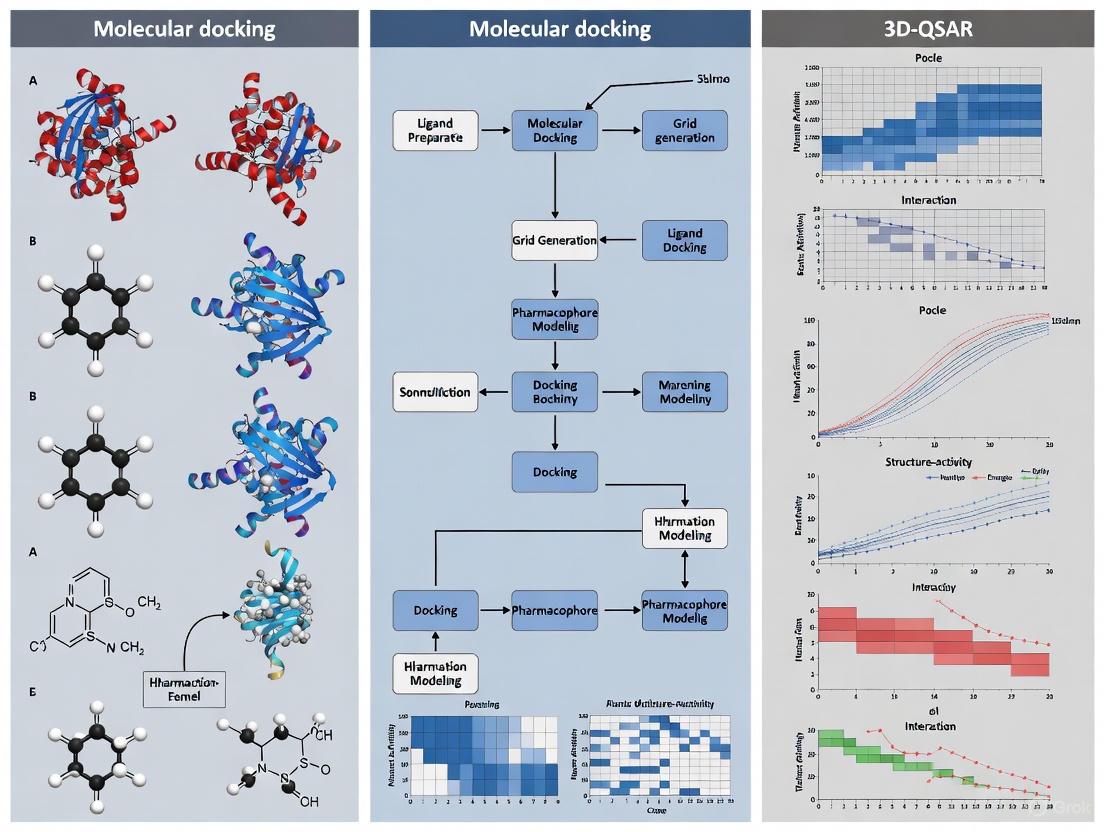

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the integrated application of 3D-QSAR and molecular docking for designing potent tubulin inhibitors.

Integrating 3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking for Novel Tubulin Inhibitors: A Computational Framework for Anticancer Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the integrated application of 3D-QSAR and molecular docking for designing potent tubulin inhibitors. It covers the foundational principles of tubulin as a anticancer target and 3D-QSAR methodology, detailed protocols for model development and virtual screening, strategies for troubleshooting common computational challenges, and robust validation techniques using molecular dynamics and binding free energy calculations. By synthesizing recent advances and practical applications, this work serves as a strategic framework for accelerating the discovery of novel tubulin-targeting anticancer agents through computational approaches.

Tubulin as a Therapeutic Target and 3D-QSAR Fundamentals

The Critical Role of Tubulin in Cancer Cell Division and Mitosis

Microtubules, hollow cylindrical filaments of the cytoskeleton, are dynamic structures composed of α/β-tubulin heterodimers and are fundamental to multiple cellular processes, most notably cell division or mitosis [1]. During mitosis, the rapid assembly and disassembly of microtubules facilitate the formation of the mitotic spindle, a complex apparatus essential for the faithful segregation of chromosomes into two daughter cells [1]. The critical role of microtubules in mitosis has established the tubulin protein as a major target for anticancer drug discovery [2]. Disrupting the delicate dynamics of tubulin polymerization and depolymerization leads to mitotic arrest and, ultimately, the death of rapidly dividing cancer cells [3]. Furthermore, emerging research on the "tubulin code"—a mechanism combining diverse tubulin isotypes with post-translational modifications (PTMs)—has revealed its significant implications for chromosomal instability, a hallmark of human cancers implicated in tumor evolution and metastasis [4] [1].

The Tubulin Code in Mitotic Fidelity and Cancer

The "tubulin code" is a conceptual framework that describes how the generation of microtubule diversity in cells is regulated by the expression of different α/β-tubulin isotypes and a range of post-translational modifications (PTMs) [4] [1]. This code plays a crucial functional role in mitosis, particularly in ensuring accurate chromosome segregation.

- Generation of Microtubule Diversity: The tubulin code involves several key PTMs, including:

- Detyrosination/Tyrosination: The catalytic removal and re-addition of the C-terminal tyrosine on α-tubulin, a cycle critical for guiding chromosome movement [1].

- Acetylation: Modification of α-tubulin at lysine 40, enriched on stable spindle microtubules [1].

- Polyglutamylation: The addition of glutamate chains to the C-terminal tails of both α- and β-tubulin [1].

- A Navigation System for Chromosomes: The tubulin code directly regulates the activity of motor proteins during mitosis. Specifically, detyrosinated α-tubulin serves as a recognition signal for the kinesin-7 motor protein CENP-E, guiding peripheral chromosomes along stable spindle microtubules toward the metaphase plate [1]. Conversely, the microtubule minus-end-directed motor dynein shows a preference for tyrosinated microtubules, which are more dynamic [1]. This opposing guidance system is essential for proper chromosome congression.

- Implications for Cancer: Alterations in the expression of tubulin isotypes and their associated PTMs have been documented in human cancers [4] [1]. These alterations can lead to errors in chromosome segregation, promoting chromosomal instability, which fuels tumor evolution and metastasis. The concept of an emerging "cancer tubulin code" suggests that specific tubulin modification patterns could have diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic relevance [4] [1].

The following diagram illustrates the key PTMs of the tubulin code and their role in the mitotic spindle during cell division.

Integrating Molecular Docking and 3D-QSAR in Tubulin Inhibitor Research

The integration of computational methodologies is a powerful strategy for streamlining the discovery and optimization of novel tubulin inhibitors. Combining 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling with molecular docking provides a comprehensive workflow that links ligand-based and structure-based drug design.

3D-QSAR Modeling: Pharmacophore Generation and Validation

3D-QSAR models correlate the biological activity of compounds with their three-dimensional structural and physicochemical properties. The following protocol outlines the key steps for developing a robust 3D-QSAR model for tubulin inhibitors, based on studies of quinoline and combretastatin analogues [3] [2].

- Data Set Curation and Ligand Preparation

- Objective: Select a set of known tubulin inhibitors with measured inhibitory activity (e.g., IC₅₀ against a cancer cell line like MCF-7 or A2780) [3] [5].

- Procedure:

- Calculate the pIC₅₀ value (pIC₅₀ = -logIC₅₀) for each compound to be used as the dependent variable in the model [3] [5].

- Divide the data set randomly into a training set (typically ~80% of compounds) for model generation and a test set (the remaining ~20%) for external validation [3] [5].

- Sketch the 3D structures of all compounds and subject them to energy minimization using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., MMFF94 or OPLS_2005) [3] [2].

- Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation

- Objective: Identify the common three-dimensional arrangement of chemical features responsible for biological activity.

- Procedure:

- Categorize training set ligands as "active" or "inactive" based on an activity threshold (e.g., pIC₅₀ > 5.5 for active, pIC₅₀ < 4.7 for inactive) [3].

- Generate multiple conformations for each ligand.

- Use software (e.g., Schrodinger's Phase module) to develop pharmacophore hypotheses based on chemical features like hydrogen bond acceptors (A), donors (D), and aromatic rings (R) [3].

- Score and rank hypotheses using a survival score. A high-quality hypothesis, such as the AAARRR model identified for quinolines, should exhibit strong statistical correlation [3].

- Model Validation

- Objective: Ensure the model is statistically robust and has predictive power for new compounds.

- Procedure:

- Internal Validation: Perform Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation on the training set to calculate the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²). A Q² > 0.5 is generally considered indicative of a model with good predictive ability [6] [2].

- External Validation: Use the test set, which was not used in model building, to calculate the predictive R² (R²Pred) [6] [7].

- Statistical Checks: Assess the model's non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (R²), Fisher value (F), and standard error of estimate (SEE) [3] [2].

Table 1: Representative Statistical Parameters from Published 3D-QSAR Models on Tubulin Inhibitors

| Compound Class | Model Type | N | R² | Q² | R²Pred | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylindole derivatives | CoMSIA/SEHDA | 33 | 0.967 | 0.814 | 0.722 | [6] [7] |

| Combretastatin A-4 analogues | CoMFA | 23 | 0.974 | 0.724 | - | [2] |

| Cytotoxic Quinolines | Pharmacophore (AAARRR.1061) | 62 | 0.865 | 0.718 | - | [3] |

| 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives | MLR-QSAR | 32 | 0.849 | - | - | [5] |

N: Number of compounds in the dataset. R²: Non-cross-validated correlation coefficient. Q²: Leave-One-Out cross-validation coefficient. R²Pred: Predictive R² for an external test set.

Molecular Docking: Predicting Binding Poses and Affinities

Molecular docking predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) within a protein's binding site.

- Protein and Ligand Preparation

- Objective: Obtain optimized structures for the target protein and ligands.

- Procedure:

- Obtain the 3D structure of tubulin from a protein data bank (e.g., PDB ID: 1SA0, 5JVD). The colchicine binding site is a common target for novel inhibitors [2] [8].

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and removing water molecules, except those critical for binding.

- Prepare the ligand structures by energy minimization and generating possible tautomers and protonation states at physiological pH.

- Docking Simulation and Analysis

- Objective: Identify the ligand's binding mode and estimate its binding energy.

- Procedure:

- Define the docking grid around the binding site of interest (e.g., the colchicine binding site at the α/β-tubulin interface) [8].

- Run the docking algorithm (e.g., Glide, AutoDock Vina) to generate multiple pose predictions for each ligand.

- Analyze the top-ranked poses based on the docking score (reported in kcal/mol) and examine key interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts, with tubulin residues (e.g., Asn101, Thr145, Leu248, Ala316, Lys352) [3] [2] [5].

Table 2: Example Docking Scores of Novel Inhibitors from Recent Studies

| Compound / Study | Target | Docking Score (kcal/mol) | Key Interacting Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pred28 (1,2,4-triazine derivative) | Tubulin (Colchicine site) | -9.6 | Not Specified [5] |

| STOCK2S-23597 (Quinoline derivative) | Tubulin (Colchicine site) | -10.95 | Forms 4 hydrogen bonds [3] |

| New Phenylindole derivatives | CDK2 / EGFR / Tubulin | -7.2 to -9.8 | Multiple hydrophobic and H-bond interactions [6] [7] |

| Combretastatin A-4 (Reference) | Tubulin (Colchicine site) | ~ -8.0 | Asn101, Leu248, Ala316 [2] |

Advanced Simulation and Experimental Validation Protocols

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations for Stability Assessment

MD simulations assess the stability and dynamics of the tubulin-inhibitor complex under physiologically relevant conditions, providing insights beyond static docking poses.

- System Setup and Equilibrium

- Objective: Create a solvated and neutralized system for simulation.

- Procedure:

- Use the best-docked pose from the previous step as the starting structure.

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in a water box (e.g., TIP3P water model) and add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's charge and emulate physiological ion concentration [9].

- Apply periodic boundary conditions.

- Energy-minimize the system and gradually heat it to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) under constant volume (NVT) and then constant pressure (NPT) ensembles to equilibrate the system's density [10] [8].

- Production Run and Trajectory Analysis

- Objective: Run the simulation and analyze the stability of the complex.

- Procedure:

- Run a production MD simulation for a sufficient duration (typically ≥100 ns) [6] [5].

- Analyze the trajectory by calculating:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the stability of the protein and ligand backbone. A stable complex will reach a plateau [5] [8].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies flexible regions of the protein [8].

- Ligand-protein interactions: Monitors the persistence of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts over the simulation time [10] [8].

- Calculate the binding free energy using methods like MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA to obtain a more accurate estimate of the binding affinity [2] [10].

The workflow below summarizes the integrated computational and experimental validation process for tubulin inhibitor development.

Experimental Validation of Tubulin Inhibition

Computational predictions require experimental validation to confirm biological activity.

- In Vitro Tubulin Polymerization Assay

- Objective: Determine the direct effect of the candidate compound on tubulin assembly into microtubules.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a solution of purified tubulin protein in a suitable buffer.

- Add the test compound (at various concentrations), a vehicle control, and reference agents (e.g., colchicine as an inhibitor, paclitaxel as a promoter).

- Initiate polymerization by increasing the temperature and monitor the increase in absorbance at 340 nm over time due to light scattering from the forming microtubules [2].

- Calculate the IC₅₀ value, the concentration of the compound that inhibits 50% of tubulin polymerization.

- Cell-Based Cytotoxicity Assays

- Objective: Evaluate the antiproliferative effect of the compound on cancer cell lines.

- Procedure:

- Culture relevant cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7 breast cancer, A2780 ovarian carcinoma).

- Treat cells with a range of concentrations of the test compound for a defined period (e.g., 48-72 hours).

- Assess cell viability using a standard assay like the MTT assay, which measures mitochondrial activity in living cells.

- Calculate the IC₅₀ value for cell growth inhibition [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Tubulin Research and Inhibitor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Tubulin Protein | In vitro biochemical assays, including tubulin polymerization kinetics. | Porcine brain, bovine brain, or recombinant human tubulin. |

| Cancer Cell Lines | Evaluation of compound cytotoxicity and antiproliferative activity. | MCF-7 (breast cancer), A2780 (ovarian cancer), HeLa (cervical cancer). |

| Reference Tubulin Inhibitors | Positive controls for biochemical and cellular assays. | Colchicine (destabilizer), Paclitaxel (stabilizer), Combretastatin A-4 (destabilizer). |

| Crystallized Tubulin Structures | Structural templates for molecular docking and MD simulations. | PDB IDs: 1SA0 (with DAMA-colchicine), 5JVD (with TUB092), 3J6G (with paclitaxel). |

| Molecular Modeling Software | 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and visualization. | SYBYL (CoMFA, CoMSIA), Schrodinger Suite, AutoDock Vina, GROMACS. |

| Antibodies for PTMs | Detection and localization of tubulin code components in cells. | Anti-detyrosinated tubulin, Anti-acetylated tubulin (K40), Anti-tyrosinated tubulin. |

Tubulin's critical function in mitosis makes it a perennially validated target for cancer chemotherapy. The integration of modern computational approaches—specifically, 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations—provides a powerful, rational framework for accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel tubulin inhibitors. This integrated protocol enables researchers to move efficiently from initial compound screening and activity prediction to detailed mechanistic studies of binding and stability. Furthermore, the growing understanding of the tubulin code opens new avenues for developing more precise cancer therapeutics and diagnostics. The experimental validation of computationally designed compounds remains the crucial step in translating these in-silico insights into tangible advances in cancer treatment.

Tubulin, a heterodimeric protein composed of α- and β-subunits, serves as the fundamental building block of microtubules—dynamic cytoskeletal filaments essential for numerous cellular processes including cell division, intracellular transport, and maintenance of cell shape [11]. The polymerization of αβ-tubulin heterodimers into protofilaments and their subsequent lateral association forms hollow, cylindrical microtubules [12]. This dynamic assembly and disassembly process, known as dynamic instability, is precisely regulated in normal cells but becomes a critical vulnerability in rapidly dividing cancer cells [11]. Consequently, therapeutic agents that disrupt microtubule dynamics have emerged as cornerstone treatments in medical oncology, inducing mitotic arrest and ultimately triggering apoptosis in malignant cells [13] [12].

Tubulin possesses several distinct binding sites for small molecules, with the colchicine, vinca alkaloid, and taxane sites representing the most extensively characterized and therapeutically exploited [13] [11]. Microtubule-targeting agents are broadly classified into two categories based on their mechanisms of action: microtubule-stabilizing agents (MSAs), such as taxanes, which promote tubulin polymerization, and microtubule-destabilizing agents (MDAs), including vinca alkaloids and colchicine-site inhibitors, which prevent microtubule assembly [12]. The following sections provide a detailed examination of these three key binding sites, their characteristic inhibitors, and the integration of advanced computational methods in modern drug discovery efforts.

Comprehensive Analysis of Tubulin Binding Sites

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Major Tubulin Binding Sites

| Binding Site | Ligand Examples | Cellular Effect | Therapeutic Applications | Resistance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxane Site | Paclitaxel, Docetaxel, Cabazitaxel | Microtubule Stabilization, Mitotic Arrest | Breast, Ovarian, Lung, Prostate Cancers | P-gp Overexpression, βIII-tubulin Isoform |

| Vinca Alkaloid Site | Vinblastine, Vincristine, Vinorelbine | Microtubule Depolymerization, Mitotic Spindle Disruption | Hematological Malignancies, Solid Tumors | P-gp Overexpression, Altered Tubulin Isoforms |

| Colchicine Site | Colchicine, Combretastatin A-4, Verubulin | Microtubule Destabilization, Vascular Disruption | Investigational (Gout, FMF for Colchicine) | Potentially Overcomes P-gp Resistance |

Taxane Binding Site

The taxane-binding site is located on the inner surface of β-tubulin within the microtubule polymer [13]. Agents binding to this site, including paclitaxel, docetaxel, and cabazitaxel, function as microtubule-stabilizing agents (MSAs) [12] [11]. They promote tubulin polymerization and stabilize the resulting microtubules against depolymerization, thereby suppressing dynamic instability [13] [12]. This stabilization interferes with the normal reorganization of microtubules required for chromosome segregation during mitosis, leading to cell cycle arrest at the metaphase/anaphase transition and ultimately inducing apoptosis in rapidly dividing cancer cells [11].

Taxanes have demonstrated significant clinical efficacy across various malignancies. Paclitaxel and docetaxel are widely used in the treatment of breast, ovarian, and lung cancers, while cabazitaxel is employed in prostate cancer therapy [12]. Despite their clinical success, taxanes face limitations including poor water solubility, dose-limiting toxicities (particularly neurotoxicity), and susceptibility to multidrug resistance (MDR) mechanisms [12]. The most common form of clinical resistance involves overexpression of the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) drug efflux pump, which decreases intracellular drug concentrations [13] [11]. Additionally, resistance can arise from β-tubulin mutations and overexpression of specific β-tubulin isotypes, particularly class III β-tubulin [13].

Vinca Alkaloid Binding Site

The vinca-binding domain is situated at the interface between two tubulin heterodimers, distinct from the intra-dimer taxane site [13] [12]. Vinca alkaloids, including vinblastine, vincristine, and vinorelbine, bind to this site with high affinity and function as microtubule-destabilizing agents (MDAs) [13] [11]. These inhibitors prevent tubulin assembly into microtubules by interacting at the growing tip of microtubules and suppressing microtubule dynamics [13]. This disruption leads to the formation of abnormal mitotic spindles unable to properly segregate chromosomes, resulting in mitotic arrest and apoptosis [11].

Vinca alkaloids were among the first tubulin-targeting agents to be used clinically and have significantly improved outcomes in hematological malignancies and certain solid tumors [11]. Vincristine exhibits particular potency against hematological cancers, while vinblastine and vinorelbine are used against various solid tumors [12] [11]. Similar to taxanes, their clinical utility is limited by neurotoxicity and the development of resistance primarily mediated by P-gp overexpression [12]. Additionally, alterations in tubulin isotype expression and mutations in tubulin itself contribute to resistance against this class of agents [11].

Colchicine Binding Site

The colchicine-binding site is located at the intradimer interface between α- and β-tubulin subunits [13] [12]. Unlike the taxane and vinca sites, this site remains clinically underexploited for cancer therapy despite extensive research [12]. Colchicine, a natural product from Colchicum autumnale, was the first identified tubulin destabilizing agent that binds to this site [13]. It exerts its effects by inducing conformational changes in tubulin dimers that prevent their assembly into microtubules [13]. Although colchicine itself is not used as an anticancer agent due to its narrow therapeutic window and significant toxicity (including neutropenia and gastrointestinal upset), it has FDA approval for treating gout and familial Mediterranean fever [13] [12].

Numerous colchicine binding site inhibitors (CBSIs) have been investigated as potential anticancer agents, including combretastatin A-4 (CA-4), verubulin, and various synthetic derivatives [13] [12] [2]. These compounds offer several potential advantages: they often circumvent P-gp-mediated multidrug resistance, retain efficacy against tumors overexpressing class III β-tubulin, and exhibit potent vascular disrupting activity (VDA) by targeting tumor vasculature [13] [12]. The structural motif common to many CBSIs is an "aromatic ring – bridge – aromatic ring" configuration exemplified by colchicine itself [12].

Table 2: Selected Colchicine Binding Site Inhibitors in Development

| Compound Name | Structural Class | Development Status | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA-4P (Fosbretabulin) | Combretastatin Analog | Phase II/III Clinical Trials | Vascular Disrupting Agent, Orphan Drug Status for Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer |

| Verubulin (MPC-6827) | Quinazoline Derivative | Phase II (Discontinued) | High Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration, Neurotoxicity Concerns |

| AVE8062 (Ombrabulin) | Combretastatin Analog | Phase III Clinical Trials | Improved Water Solubility, Efficacy Against Taxane-Resistant Cells |

| OXi4503 | Combretastatin A-1 Diphosphate | Phase I Clinical Trials | Dual Tubulin and Vascular Targeting |

Structural analyses reveal that the colchicine site can be divided into three zones: Zone 1 (mainly formed by α-tubulin residues) interacts with the tropone ring of colchicine; Zone 2 (a hydrophobic pocket in β-tubulin) accommodates the A ring of colchicine; and Zone 3 (buried deeper in the β subunit) provides additional binding interactions [12]. CBSIs like verubulin share similar binding modes, with their aromatic systems occupying analogous positions and forming extensive hydrophobic interactions with residues including βCys239, βLeu248, βAla250, and βLys352 [12].

Integration of Molecular Docking and 3D-QSAR in Tubulin Inhibitor Research

The integration of computational methodologies has revolutionized modern tubulin inhibitor discovery, enabling more efficient and targeted drug development. The synergy between molecular docking and three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has proven particularly valuable in optimizing compound design and understanding binding interactions at tubulin's various sites.

Molecular Docking for Binding Mode Analysis

Molecular docking simulations predict how small molecules orient themselves within binding pockets of target proteins, providing atomic-level insights into binding conformations, interaction types, and binding affinities [5]. In tubulin research, docking studies have elucidated key interactions between inhibitors and specific residues in the colchicine, vinca, and taxane sites [12] [2]. For example, docking analyses revealed that verubulin's quinazoline ring occupies space corresponding to colchicine's A and B rings, while its methoxybenzene moiety overlaps with colchicine's C ring, forming hydrophobic interactions with β-tubulin residues without direct contact with α-tubulin [12]. Similarly, docking studies of novel 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives identified compound Pred28 with a high docking score of -9.6 kcal/mol, suggesting strong binding affinity to the colchicine site [5].

3D-QSAR for Activity Prediction

3D-QSAR techniques, including Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), correlate biological activity with three-dimensional structural and electronic features of compounds [3] [2]. These methods generate contour maps that highlight regions where specific chemical modifications would enhance or diminish biological activity [3] [7]. For instance, in a 3D-QSAR study of combretastatin A-4 analogues, both CoMFA and CoMSIA models demonstrated high predictive ability with correlation coefficients (r²) of 0.974 and 0.976, respectively, and cross-validated coefficients (q²) of 0.724 and 0.710 [2]. Another study on cytotoxic quinolines identified an optimal six-point pharmacophore model (AAARRR.1061) comprising three hydrogen bond acceptors and three aromatic rings, showing high correlation (R² = 0.865) and predictive power (Q² = 0.718) [3].

Integrated Workflow and Validation

The combined application of docking and 3D-QSAR creates a powerful iterative workflow for tubulin inhibitor optimization [3] [2]. Docking provides reliable binding conformations for 3D-QSAR alignment, while 3D-QSAR results guide structural modifications that can be validated through subsequent docking studies [2]. This integrated approach is further strengthened with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which assess the stability of protein-ligand complexes over time and calculate binding free energies [5] [2]. For example, in the development of phenylindole derivatives as multitarget inhibitors, 100ns MD simulations confirmed complex stability with low root mean square deviation (RMSD) values, validating docking predictions [7].

Diagram 1: Integrated Computational Workflow for Tubulin Inhibitor Development. This workflow illustrates the iterative cycle of computational methods and experimental validation in modern tubulin-targeted drug discovery.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Molecular Docking Protocol for Tubulin-Colchicine Site

Objective: To predict binding modes and affinities of novel compounds at the tubulin-colchicine binding site.

Workflow:

Protein Preparation:

- Obtain tubulin structure (e.g., PDB ID: 1SA0) from Protein Data Bank.

- Remove crystallographic water molecules and co-crystallized ligands.

- Add hydrogen atoms and optimize protonation states using MolProbity or similar tools.

- Perform energy minimization using AMBER or OPLS forcefields.

Ligand Preparation:

- Sketch 2D structures of compounds using ChemDraw or similar software.

- Generate 3D conformations and minimize energy using MMFF94 or GAFF forcefields.

- Assign Gasteiger-Hückel or AM1-BCC partial charges.

Grid Generation:

- Define binding site using colchicine as reference (center coordinates: x=35.5, y=9.5, z=70.2).

- Set grid box dimensions (e.g., 60×60×60 points with 0.375Å spacing).

Docking Execution:

- Utilize AutoDock Vina, Glide, or GOLD software.

- Set exhaustiveness parameter to 20-50 for thorough sampling.

- Generate 20-50 poses per compound.

Analysis:

- Cluster poses by root-mean-square deviation (RMSD < 2.0Å).

- Identify key interactions with residues: βCys241, βLeu255, βLys352, βAsn258, βVal318.

- Select top-ranked pose based on scoring function and interaction consistency.

Key Considerations: Validate protocol by re-docking native ligand (RMSD < 2.0Å from crystal structure). Include known inhibitors (e.g., colchicine, CA-4) as positive controls.

3D-QSAR Modeling Protocol (CoMFA/CoMSIA)

Objective: To develop predictive 3D-QSAR models for tubulin inhibitor activity.

Workflow:

Dataset Curation:

- Collect 20-50 compounds with known tubulin polymerization inhibition (IC50) or cytotoxicity (IC50).

- Convert IC50 to pIC50 (-logIC50) for linear regression.

- Divide dataset: 70-80% training set, 20-30% test set.

Molecular Alignment:

- Identify common core structure (e.g., cis-stilbene for CA-4 analogs).

- Perform database alignment using RMSD atom fitting or pharmacophore-based alignment.

Field Calculation:

- CoMFA: Calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields using sp³ carbon probe with +1 charge.

- CoMSIA: Calculate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen-bond donor, and hydrogen-bond acceptor fields using common probe.

Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis:

- Apply leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation to determine optimal components.

- Build final model with non-cross-validated PLS regression.

- Evaluate model quality: q² > 0.5, r² > 0.8, low standard error.

Contour Map Analysis:

- Visualize sterically favored/disallowed regions (green/yellow).

- Identify electropositive/electronegative favored regions (blue/red).

- Correlate contour regions with structural features for design.

Validation: Use external test set (R²pred > 0.6), y-randomization, and domain applicability analysis.

Tubulin Polymerization Inhibition Assay

Objective: To experimentally evaluate compounds for inhibition of tubulin polymerization in vitro.

Materials:

- Purified tubulin (>97% pure, cytosolic)

- GPEM buffer: 1 mM GTP, 1 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 M PIPES, pH 6.8

- Test compounds dissolved in DMSO (<1% final concentration)

- 96-well plates, UV-Vis spectrophotometer or fluorescence plate reader

- Temperature-controlled spectrophotometer

Procedure:

- Prepare reaction mixture containing 2 mg/mL tubulin, 1 mM GTP in GPEM buffer.

- Add test compounds (0.1-100 µM range) or controls (colchicine as positive control, DMSO as negative control).

- Transfer to pre-warmed (37°C) 96-well plates.

- Immediately monitor turbidity at 350 nm every 10-30 seconds for 30-40 minutes.

- Calculate percentage inhibition relative to DMSO control.

- Determine IC50 values using non-linear regression of concentration-response data.

Data Analysis: Compare initial rates, maximum absorbance, and area under the polymerization curve. Perform statistical analysis with n≥3 replicates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Tubulin Binding Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Application/Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purified Tubulin | >97% purity, cytosolic, lyophilized | In vitro polymerization assays, binding studies | Cytoskeleton Inc., Sigma-Aldrich |

| Colchicine | ≥95% purity, reference standard | Positive control for binding site competition | Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris |

| Combretastatin A-4 | ≥98% purity, crystalline | Reference CBSI for biochemical assays | Abcam, Cayman Chemical |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | ≥97% purity, suitable for cell culture | Microtubule stabilization control | Sigma-Aldrich, MedChemExpress |

| Vinblastine Sulfate | ≥95% purity, cell culture tested | Vinca site reference inhibitor | Tocris, Selleck Chemicals |

| GTP | ≥95% purity, sodium salt | Tubulin polymerization cofactor | Sigma-Aldrich, Roche |

| PIPES Buffer | ≥99% purity, molecular biology grade | Tubulin polymerization assay buffer | Thermo Fisher, Sigma-Aldrich |

| Pre-coated ELISA Plates | High-binding, clear flat-bottom | Tubulin binding ELISAs | Corning, Thermo Fisher |

| Anti-β-Tubulin Antibody | Monoclonal, validated for WB/IF | Detection of tubulin in cellular assays | Cell Signaling, Abcam |

Emerging Directions and Novel Binding Sites

Beyond the classical binding sites, recent research has identified novel pharmacological sites on tubulin, expanding opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Gatorbulin-1 (GB1), a marine-derived cyclodepsipeptide, targets a distinct seventh binding site at the tubulin intradimer interface [14]. This site is structurally different from the colchicine, vinca, and taxane sites, with GB1 making extensive contacts and hydrogen bonds with both α- and β-chains of tubulin [14]. Structure-activity relationship studies of gatorbulin analogs revealed that the hydroxamate moiety in the N-methyl-alanine residue is critical for activity, while other structural features including C-hydroxylation of asparagine and methylation at C-4 of proline are functionally relevant [14].

The maytansine site, which partially overlaps with the vinca site, has gained prominence through the development of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) such as trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla) and polatuzumab vedotin (Polivy) [12] [11]. Additionally, the ninth binding site—the tumabulin site—was recently discovered at the interface between α1-tubulin, β1-tubulin, and RB3 [12]. These novel sites offer opportunities to overcome resistance mechanisms that limit current tubulin-targeting therapies and may provide improved therapeutic windows through unique binding modes and mechanisms of action.

The colchicine, vinca alkaloid, and taxane binding sites on tubulin represent clinically validated targets for cancer therapy, each with distinct mechanisms of action and therapeutic profiles. While taxanes and vinca alkaloids have established roles in clinical oncology, colchicine-site inhibitors offer promising avenues for overcoming multidrug resistance and targeting tumor vasculature. The integration of molecular docking and 3D-QSAR modeling has significantly advanced tubulin inhibitor development, enabling rational design of compounds with optimized binding interactions and pharmacological properties. Emerging discoveries of novel binding sites further expand the therapeutic potential of tubulin-targeting strategies. As computational methods continue to evolve alongside structural biology, the integration of these approaches will undoubtedly yield next-generation tubulin inhibitors with enhanced efficacy and reduced toxicity profiles for cancer treatment.

Application Notes

Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) represents a pivotal advancement in computational drug design, moving beyond traditional 2D descriptors to incorporate the spatial and electrostatic properties of molecules. These techniques are particularly valuable in the rational design of tubulin inhibitors, a prominent class of anticancer agents. By correlating the three-dimensional molecular field characteristics of compounds with their biological activity, 3D-QSAR models provide visual contour maps that guide medicinal chemists in optimizing structural features to enhance potency.

The integration of 3D-QSAR with molecular docking creates a powerful synergistic workflow in tubulin research. While docking offers a detailed, atomic-level view of ligand-protein interactions within defined binding sites like colchicine or taxane sites, 3D-QSAR delivers a quantitative and predictive model of how structural modifications influence activity across a congeneric series. This combination is exceptionally suited for addressing challenges such as drug resistance mediated by βIII-tubulin isotype overexpression, enabling the design of next-generation inhibitors with improved binding affinity and selectivity [15] [16].

Core 3D-QSAR Methodologies and Their Application to Tubulin

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA)

CoMFA is a seminal 3D-QSAR technique that models biological activity based on steric and electrostatic molecular interaction fields. A probe atom is used to sample the space around a set of aligned molecules, and the resulting field energies are correlated with activity using Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression.

In practice, for a series of tubulin inhibitors such as colchicine analogues or phenylindole derivatives, CoMFA contour maps visually highlight regions where:

- Increased steric bulk (green contours) may enhance activity.

- Decreased steric bulk (yellow contours) may be favorable.

- Positive electrostatic potential (blue contours) is associated with higher activity.

- Negative electrostatic potential (red contours) is associated with higher activity [17] [18].

Table 1: Key Statistical Parameters for Validating 3D-QSAR Models

| Parameter | Description | Threshold for a Valid Model |

|---|---|---|

| R² | Non-cross-validated correlation coefficient | > 0.6 [17] |

| Q² (LOO) | Leave-One-Out cross-validated correlation coefficient | > 0.5 [17] [7] |

| SEE | Standard Error of Estimate | Should be low |

| F-value | Fisher F-test value for statistical significance | Should be high [3] |

| N | Optimal Number of Components from PLS | - |

| R²ₚᵣₑ𝒹 | Predictive R² for an external test set | > 0.5 [17] |

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA)

CoMSIA extends beyond CoMFA by evaluating additional physicochemical properties, offering a more nuanced view of ligand-receptor interactions. In addition to steric and electrostatic fields, CoMSIA typically includes:

- Hydrophobic fields: Identify regions where hydrophobic interactions boost activity.

- Hydrogen Bond Donor/Acceptor fields: Pinpoint optimal locations for H-bond interactions.

A robust CoMSIA model for 2-phenylindole derivatives as tubulin inhibitors demonstrated high reliability, with a non-cross-validated R² of 0.967 and a cross-validated Q² of 0.814 [7]. The inclusion of hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding fields often makes CoMSIA models more interpretable for optimizing tubulin inhibitors, which frequently engage in complex hydrophobic and polar interactions within the binding pocket.

Pharmacophore Modeling

A pharmacophore is an abstract model that defines the essential steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target. It represents the supramolecular interaction pattern rather than a specific chemical structure. For instance, a study on cytotoxic quinolines identified a six-point pharmacophore hypothesis, AAARRR.1061, consisting of three hydrogen bond acceptors (A) and three aromatic rings (R). This model exhibited a high correlation (R² = 0.865) and was successfully used for virtual screening to identify novel tubulin inhibitor candidates [3].

Table 2: Representative 3D-QSAR and Pharmacophore Models in Tubulin Inhibitor Research

| Compound Class | Target / Activity | Model Type | Key Features / Descriptors | Statistical Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxic Quinolines [3] | Tubulin Inhibitors | Pharmacophore (AAARRR.1061) | 3 H-bond Acceptors, 3 Aromatic Rings | R² = 0.865, Q² = 0.718 |

| 2-Phenylindole Derivatives [7] | MCF-7 Breast Cancer | CoMSIA | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-Bond Donor/Acceptor | R² = 0.967, Q² = 0.814 |

| Colchicine Analogues [19] | Tubulin-Colchicine Site | 3D-QSAR | Steric and Electrostatic Fields | R² = 0.9438, Q² = 0.8915 |

| 1,2,4-Triazine-3(2H)-one [5] | Tubulin-Colchicine Site | QSAR (MLR) | Absolute Electronegativity (χ), Water Solubility (LogS) | R² = 0.849 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing a CoMFA/CoMSIA Model for Tubulin Inhibitors

This protocol outlines the key steps for constructing a robust 3D-QSAR model using CoMFA and CoMSIA methodologies, tailored for a series of tubulin inhibitors.

Step 1: Data Set Curation and Preparation

- Compound Selection: Compile a dataset of compounds with known experimental biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀ for tubulin polymerization inhibition or cytotoxicity against a relevant cancer cell line). A typical dataset should include 20-50 molecules with a wide and continuous range of activity values [7] [5].

- Activity Conversion: Convert IC₅₀ values to pIC₅₀ (pIC₅₀ = -logIC₅₀) for a more linear correlation with free energy changes.

- Training and Test Sets: Randomly divide the dataset into a training set (≈80%) for model development and a test set (≈20%) for external validation [5]. Ensure both sets are representative of the structural and activity range.

Step 2: Molecular Modeling and Alignment

- Geometry Optimization: Sketch 3D structures and perform energy minimization using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., Tripos or OPLS) with assigned atomic charges (e.g., Gasteiger-Hückel) [7].

- Molecular Alignment: This is the most critical step. Align all molecules based on a common scaffold or a putative pharmacophore. For tubulin inhibitors binding to a specific site like colchicine, the most active compound is often used as a template for aligning the dataset using the "distill" method in SYBYL or similar software [7].

Step 3: Field Calculation and PLS Analysis

- Grid Generation: Create a 3D cubic grid with a spacing of 2.0 Å that encompasses all aligned molecules [17] [7].

- Field Calculation:

- CoMFA: Calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields using an sp³ carbon probe with a +1 charge.

- CoMSIA: Calculate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor fields using the respective probes.

- PLS Regression: Use the Partial Least Squares (PLS) algorithm to correlate the field descriptors with the biological activity (pIC₅₀). First, perform Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation to determine the optimal number of components (ONC) that gives the highest Q². Then, perform a non-cross-validated regression with this ONC to generate the final model with R² and standard error of estimate (SEE) [17] [7].

Step 4: Model Validation

Robust validation is essential to ensure the model's predictive power.

- Internal Validation: Q² > 0.5 is generally considered statistically significant [17].

- External Validation: Predict the activity of the test set compounds and calculate the predictive R² (R²ₚᵣₑ𝒹). R²ₚᵣₑ𝒹 > 0.5 indicates a good predictive model [17] [20].

- Additional Checks: Perform Y-randomization to rule out chance correlation and define the Applicability Domain (APD) to identify the model's scope [20].

Protocol 2: Generating a Common Pharmacophore Hypothesis

This protocol describes the process of identifying a common set of chemical features shared by active tubulin inhibitors.

Step 1: Conformational Analysis and Feature Mapping

- Ligand Preparation: Generate a diverse set of low-energy conformers for each molecule in the dataset (e.g., a maximum of 100 conformers per molecule) [3].

- Activity Classification: Categorize compounds as "active" or "inactive" based on a predefined activity threshold (e.g., pIC₅₀ > 5.5 for active, pIC₅₀ < 4.7 for inactive) [3].

- Feature Identification: Define potential pharmacophore features such as Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (A), Hydrogen Bond Donor (D), Hydrophobic (H), Positively Charged (P), Negatively Charged (N), and Aromatic Ring (R) [3] [20].

Step 2: Hypothesis Generation and Scoring

- Hypothesis Generation: The software (e.g., Phase in Schrödinger) develops common pharmacophore hypotheses that are present in the active compounds but absent in the inactive ones.

- Hypothesis Scoring: Rank the generated hypotheses using a scoring function (e.g., Survival Score) that considers the alignment of vectors, volumes, and how well the hypothesis reflects the activity data. Select the top-ranked hypothesis (e.g., AAARRR.1061 for quinolines) for further studies [3].

Step 3: Pharmacophore-Based 3D-QSAR and Virtual Screening

- 3D-QSAR Model Building: Use the selected pharmacophore to align the molecules and build a 3D-QSAR model using PLS, similar to the CoMFA/CoMSIA process.

- Database Screening: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, IBScreen) to identify novel hit compounds that match the essential feature arrangement [3] [15].

Workflow for Integrated 3D-QSAR and Docking

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR in Tubulin Research

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function in Workflow | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maestro (Schrödinger) [3] | Integrated Suite | Ligand preparation (LigPrep), conformational analysis, and pharmacophore modeling (Phase). | Preparing a set of quinoline derivatives for 3D-QSAR [3]. |

| SYBYL [7] | Molecular Modeling | Structure building, energy minimization, CoMFA/CoMSIA analysis, and molecular alignment. | Developing a CoMSIA model for 2-phenylindole derivatives [7]. |

| Gaussian 09W [5] | Quantum Chemistry | Calculating electronic descriptors (e.g., HOMO/LUMO energies) for QSAR using DFT methods. | Computing absolute electronegativity for 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives [5]. |

| AutoDock Vina/InstaDock [15] | Molecular Docking | Predicting binding poses and affinities of hits within the tubulin binding site (e.g., colchicine site). | Screening natural compounds against the βIII-tubulin isotype [15]. |

| Open Babel [15] | Cheminformatics | File format conversion for large compound libraries during virtual screening. | Converting SDF files from ZINC database to PDBQT format for docking [15]. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor [15] | Descriptor Calculation | Generating molecular descriptors and fingerprints for machine learning-based QSAR. | Creating features for ML classifiers to identify active tubulin inhibitors [15]. |

| GROMACS/AMBER [15] [5] | Molecular Dynamics | Simulating the stability of tubulin-ligand complexes over time using RMSD, RMSF, Rg, SASA. | Confirming the stable binding of a hit compound over 100 ns simulation [5]. |

Key Molecular Descriptors for Tubulin Inhibitor Activity Prediction

The rational design of tubulin inhibitors represents a crucial strategy in anticancer drug development, particularly for overcoming limitations of conventional therapies such as drug resistance and systemic toxicity [21]. The integration of molecular docking with three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has emerged as a powerful computational framework for identifying and optimizing novel tubulin-targeting agents [22]. This protocol details the key molecular descriptors and experimental methodologies essential for predicting tubulin inhibitor activity within this integrated framework, providing researchers with a structured approach to accelerate anticancer drug discovery.

Molecular descriptors quantitatively characterize structural and physicochemical properties that govern biological activity. For tubulin inhibitors, these descriptors help elucidate critical binding interactions with various tubulin sites, including the colchicine, vinca alkaloid, and taxane binding domains [21] [22]. The accurate prediction of inhibitor potency relies on identifying optimal combinations of steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding features that complement these binding pockets.

Key Molecular Descriptors for Tubulin Inhibition

Experimental Data Compilation

Table 1 summarizes the primary molecular descriptors identified as critical predictors of tubulin inhibition activity across multiple compound classes, as derived from comprehensive QSAR studies.

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptors for Tubulin Inhibitor Activity Prediction

| Descriptor Category | Specific Descriptors | Structural Interpretation | Impact on Tubulin Inhibition | Representative Compound Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Features | Three hydrogen bond acceptors (A), Three aromatic rings (R) [3] | Defines spatial arrangement for complementary binding | High correlation with activity (R² = 0.865) [3] | Cytotoxic quinolines [3] |

| Electronic Properties | Absolute electronegativity (χ) [5] | Overall electron-attracting ability | Higher electronegativity increases activity | 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives [5] |

| Topological Descriptors | Chi1n, HeavyAtomCount, HeavyAtomMolWt [23] [24] | Molecular branching, size, and complexity | Optimal values enhance binding affinity | Phenanthrene analogs [23] [24] |

| Solubility & Hydrophobicity | Water solubility (LogS), EState_VSA8 [23] [5] | Polar surface area, hydrogen bonding capacity | Moderate hydrophobicity improves cellular uptake | 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives [5] |

| Surface Property Descriptors | VSAdon, SMRVSA5 [25] | Polarizability, hydrogen bond donor capacity | Enhances tubulin polymerization inhibition | Diarylsulphonylurea derivatives [25] |

Structural Interpretation of Key Descriptors

The AAARRR.1061 pharmacophore model identified for cytotoxic quinolines exemplifies optimal spatial arrangement for tubulin binding, consisting of three hydrogen bond acceptors and three aromatic rings with specific distance and angular relationships [3]. This model demonstrated high statistical significance with a correlation coefficient (R²) of 0.865 and cross-validation coefficient (Q²) of 0.718, indicating robust predictive capability for tubulin inhibitory activity [3].

Electronic descriptors such as absolute electronegativity (χ) directly influence binding affinity through charge-transfer interactions with tubulin binding site residues [5]. For 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives, higher electronegativity correlates strongly with enhanced inhibitory activity against breast cancer cell lines [5].

Topological descriptors including Chi1n and HeavyAtomCount capture aspects of molecular shape and complexity that complement the structural dimensions of tubulin binding pockets [23] [24]. In phenanthrene analogs, these descriptors showed significant correlation with anti-proliferative activity in HepG2 liver cancer cells, facilitating virtual screening of potent candidates [23].

Integrated QSAR and Molecular Docking Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational pipeline for tubulin inhibitor activity prediction:

Dataset Preparation and Molecular Optimization

Procedure:

- Compound Selection: Compile a structurally diverse dataset of known tubulin inhibitors with corresponding experimental bioactivity values (IC₅₀) [3] [5]. For the 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives study, 32 compounds with pIC₅₀ values ranging from 3.460 to 4.963 were selected [5].

- Training-Test Set Division: Implement an 80:20 ratio for splitting compounds into training and test sets using randomized selection to ensure representative chemical space coverage [5].

- Structure Optimization: Generate 3D molecular structures using builder modules in molecular modeling software (e.g., Maestro, SYBYL) [3] [7]. Perform energy minimization using appropriate force fields (e.g., OPLS_2005, Tripos molecular mechanics) with implicit solvation models [3] [7].

- Conformer Generation: Generate multiple low-energy conformers for each compound (maximum 100 conformers) to account for flexible binding orientations [3].

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and QSAR Modeling

Procedure:

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute 2D and 3D molecular descriptors using computational packages such as Gaussian (for electronic descriptors), ChemOffice (for topological descriptors), and MOE QuaSAR module (for surface area descriptors) [5] [25].

- Descriptor Selection: Apply statistical methods including principal component analysis (PCA) and stepwise variable selection to identify the most relevant, non-collinear descriptors [5].

- Model Development: Employ multiple linear regression (MLR) or partial least squares (PLS) analysis to construct QSAR models correlating descriptors with biological activity [3] [5].

- Model Validation: Validate models using leave-one-out cross-validation (Q²), external test set prediction (R²Pred), and Y-randomization testing to ensure robustness and avoid overfitting [3] [20].

Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

Procedure:

- Pharmacophore Generation: Develop pharmacophore hypotheses using active compound alignments, identifying critical features including hydrogen bond acceptors (A), donors (D), hydrophobic groups (H), and aromatic rings (R) [3] [20].

- Hypothesis Validation: Evaluate hypotheses based on survival scores, vector alignment, and statistical correlation with activity values [3].

- Virtual Screening: Screen compound databases (e.g., IBScreen, Aldrich Market Select) against validated pharmacophore models to identify novel potential inhibitors [3] [23].

- Activity Prediction: Apply developed QSAR models to predict activity of screened compounds and prioritize candidates for further analysis [23].

Molecular Docking and Binding Mode Analysis

Procedure:

- Protein Preparation: Obtain tubulin structure from Protein Data Bank (e.g., 1SA0). Remove native ligands, add hydrogen atoms, and optimize side-chain orientations using protein preparation workflows [3] [22].

- Binding Site Definition: Define specific binding sites (colchicine, vinca alkaloid, or taxane sites) based on crystallographic data [21] [22].

- Docking Protocol: Perform molecular docking using software such as Glide, GOLD, or AutoDock with appropriate scoring functions [3] [23]. Validate docking accuracy by re-docking native ligands and calculating RMSD values (target < 2.0 Å) [20].

- Interaction Analysis: Identify key binding interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking) between compounds and tubulin residues [3] [26].

ADMET Prediction and Molecular Dynamics

Procedure:

- ADMET Profiling: Predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties using in silico tools such as QikProp or SwissADME [23] [5]. Evaluate key parameters including LogP, LogS, polar surface area, and blood-brain barrier permeability [23].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Conduct MD simulations (100-200 ns) using GROMACS or AMBER to evaluate complex stability under physiological conditions [23] [5]. Analyze root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and binding free energies [5].

- Candidate Prioritization: Integrate all computational analyses to select promising tubulin inhibitors with optimal activity predictions, favorable binding modes, and suitable ADMET profiles for experimental validation [23] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Tubulin Inhibitor Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Application in Protocol | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Suites | Maestro (Schrödinger) [3], SYBYL [7], MOE [25] | Structure preparation, pharmacophore modeling, QSAR analysis | Integrated environments for drug discovery, force field-based minimization, conformational sampling |

| Descriptor Calculation | Gaussian [5], ChemOffice [5] | Electronic and topological descriptor computation | DFT calculations, topological index computation, property prediction |

| Docking & Simulation | Glide [3], GROMACS [23], AMBER | Molecular docking, dynamics simulations | High-throughput virtual screening, explicit solvation models, binding free energy calculations |

| Statistical Analysis | XLSTAT [5], SYSTAT [25] | QSAR model development, statistical validation | Multiple linear regression, principal component analysis, cross-validation methods |

| Compound Databases | IBScreen [3], Aldrich Market Select [23] | Virtual screening of novel compounds | Commercially available compounds, diverse chemical libraries, purchasable molecules |

The integration of molecular docking with 3D-QSAR modeling provides a powerful strategy for identifying key molecular descriptors that predict tubulin inhibitor activity. The experimental protocol outlined herein enables systematic characterization of critical structural and physicochemical properties governing tubulin binding, facilitating the rational design of novel anticancer agents with optimized potency and selectivity. By implementing this comprehensive computational pipeline, researchers can efficiently prioritize promising tubulin inhibitors for synthetic efforts and experimental validation, accelerating the discovery of next-generation microtubule-targeting therapeutics.

Data Set Curation and Preparation for Reliable Model Development

In the context of a broader thesis on integrating molecular docking with three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling for tubulin inhibitor research, the critical foundation lies in the meticulous curation and preparation of high-quality data sets. Tubulin remains a validated target for cancer therapy, with its inhibitors playing a crucial role in disrupting microtubule dynamics and cancer cell proliferation [5] [22]. The reliability of any subsequent computational model—whether molecular docking, 3D-QSAR, or molecular dynamics simulations—is fundamentally dependent on the initial data set quality. This protocol outlines standardized procedures for assembling, curating, and preparing tubulin inhibitor data sets to ensure robust and predictive model development.

Data Collection and Sourcing

The initial phase involves systematic gathering of tubulin inhibitor data from diverse sources to ensure comprehensive coverage and structural diversity. Researchers should prioritize experimentally validated tubulin inhibitors with published biological activity measurements.

Table 1: Exemplar Data Sets in Tubulin Inhibitor Research

| Data Set Description | Compound Count | Biological Activity | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives | 32 | pIC50 (3.460–4.963) against MCF-7 breast cancer cell line | [5] |

| Styrylquinoline derivatives | 43 | IC50 (4.12-5.95 µM) converted to pIC50 | [27] |

| Assembled tubulin-microtubule system inhibitors | 851 | pIC50 values across multiple cancer cell lines | [28] |

Activity Data Standardization

Consistent activity data representation is essential for reliable model development. Convert all half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values to pIC50 using the standard formula:

This transformation linearizes the relationship between concentration and binding affinity, improving model performance in subsequent QSAR analyses.

Compound Curation Protocols

Structure Standardization

- Representation: Draw all compound structures using standardized chemical drawing software such as Sybyl [27].

- Optimization: Perform geometry optimization using appropriate force fields (e.g., Tripos force field with convergence threshold of 0.01 kcal/mol) [27].

- Validation: Visually inspect all structures to ensure correct stereochemistry and tautomeric forms.

Data Set Division

Implement rigorous data set splitting to enable model validation:

- Training Set: Allocate 80% of compounds for model development [5].

- Test Set: Reserve 20% of compounds for external validation [5].

- Randomization: Apply randomized splitting to avoid potential biases related to data entry order [5].

Molecular Descriptor Computation

Electronic Descriptors

Compute quantum chemical descriptors using Density Functional Theory (DFT):

- Software: Employ Gaussian 09W program with DFT/B3LYP functional and 6-31G (p, d) basis set [5].

- Key Descriptors: Calculate highest occupied molecular orbital energy (EHOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy (ELUMO), dipole moment (μm), total energy (TE) [5].

Derived Properties: Determine absolute hardness (η), absolute electronegativity (χ), and reactivity index (ω) using established equations [5]:

η = (ELUMO - EHOMO)/2 χ = (ELUMO + EHOMO)/2 ω = μ²/2η

Topological Descriptors

Calculate physiochemical and topological descriptors using specialized software:

- Software: Utilize ChemOffice software 16.0 or equivalent [5].

- Key Descriptors: Include molecular weight (MW), hydrogen bond acceptors/donors (NHA, NHD), octanol-water partition coefficient (LogP), water solubility (LogS), polar surface area (PSA), and number of rotatable bonds (NROT) [5].

3D-QSAR Specific Preparation

Molecular Alignment

Proper molecular alignment is critical for 3D-QSAR model development:

- Template Selection: Identify a reference compound with high activity as an alignment template (e.g., compound 22 in styrylquinoline studies) [27].

- Alignment Method: Use common substructure or atom-based fitting methods to superimpose all compounds [27].

- Validation: Visually inspect aligned structures to ensure pharmacophore-relevant orientation.

Conformational Analysis

- Energy Minimization: Optimize all structures using appropriate force fields prior to alignment [27].

- Active Conformation: Select the biologically relevant conformation based on experimental evidence or docking poses.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Software | Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian 09W | Quantum chemical calculations | Electronic descriptor computation [5] |

| ChemOffice | Topological descriptor calculation | 2D molecular property calculation [5] |

| Sybyl | Molecular modeling and alignment | 3D-QSAR model development [27] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Tubulin structure source | Molecular docking target (e.g., PDB ID: 4O2B) [27] |

| XLSTAT | Statistical analysis | QSAR model development and validation [5] |

Quality Control and Validation

Data Set Validation

- Structural Diversity: Assess chemical space coverage using principal component analysis (PCA) or t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) [5] [28].

- Activity Range: Verify that both training and test sets cover the entire activity range present in the full data set.

- Outlier Detection: Identify and investigate compounds with unusual structural features or extreme activity values.

Model Validation Techniques

- Y-randomization: Perform randomization tests to confirm model robustness by scrambling activity values and demonstrating model failure under these conditions [27].

- Applicability Domain: Define the chemical space boundaries where the model provides reliable predictions.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Data Set Curation Workflow for Tubulin Inhibitor Modeling

Diagram 2: Computational Preparation Pipeline

Robust data set curation and preparation form the foundation for developing reliable computational models in tubulin inhibitor research. By adhering to these standardized protocols—encompassing systematic data collection, structural standardization, comprehensive descriptor computation, rigorous validation, and appropriate data set division—researchers can establish high-quality data sets suitable for integrated molecular docking and 3D-QSAR studies. This meticulous approach to data preparation ensures that subsequent models will provide meaningful insights into tubulin-inhibitor interactions and facilitate the rational design of novel therapeutic agents with optimized pharmacological profiles.

Integrated Computational Workflow: From Model Building to Virtual Screening

Developing Robust 3D-QSAR Models with High Predictive Power (q² > 0.7)

The integration of computational methodologies has become a cornerstone in modern drug discovery, significantly accelerating the identification and optimization of lead compounds. Within the specific context of tubulin inhibitor research—a critical area in developing anticancer agents—Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling serves as a powerful ligand-based drug design approach. When robustly constructed and validated, these models can predict the biological activity of novel molecules with high accuracy, guiding synthetic efforts and reducing experimental costs. This protocol details the establishment of a 3D-QSAR model with a cross-validated coefficient (q²) exceeding 0.7, a benchmark indicating high predictive power, and frames the process within a broader strategy that integrates molecular docking for tubulin inhibitor development [15] [29].

The fundamental principle of 3D-QSAR is to correlate the three-dimensional molecular fields of a set of compounds with their measured biological activities. Unlike traditional QSAR, which uses global molecular descriptors, 3D-QSAR considers the spatial and electrostatic characteristics of molecules, providing a more nuanced understanding of steric and electronic requirements for binding to a biological target like tubulin [30]. For tubulin inhibitors, which often bind to specific sites such as the colchicine or taxol site, understanding these requirements is paramount for designing potent and selective agents [15]. Recent studies on natural inhibitors of the human αβIII tubulin isotype have successfully leveraged structure-based drug design alongside machine learning, underscoring the value of advanced computational pipelines in this field [15].

Application Notes: Core Principles and Workflow

The 3D-QSAR Concept and Its Relevance to Tubulin Research

3D-QSAR models quantitatively describe how modifications to a molecule's structure, particularly in three-dimensional space, affect its biological activity. The model's output is often visualized as contour maps that highlight regions where specific molecular properties (e.g., steric bulk, electropositive character) would favorably or unfavorably influence activity. This is exceptionally valuable for optimizing tubulin inhibitors, as it provides visual, atom-level guidance for medicinal chemists [30].

For instance, a steric contour map might show a green favored region near a specific substituent of a tubulin inhibitor, suggesting that enlarging a group in that area could enhance binding affinity by filling a hydrophobic pocket in the tubulin protein. Conversely, a yellow disfavored region would warn against introducing bulky groups that might cause steric clashes [30]. This direct, interpretable feedback is crucial for the rational design of next-generation inhibitors.

The Integrated Workflow: From Data Collection to Model Application

A robust 3D-QSAR study is not an isolated event but part of a larger, iterative drug discovery cycle. For tubulin inhibitors, this often begins with the cloning, expression, and purification of the tubulin protein, followed by high-throughput screening to identify initial hit compounds with anti-tubulin activity. The subsequent workflow for a 3D-QSAR study is methodical and consists of several critical, interconnected stages, as outlined below [30] [29]:

Protocol: A Step-by-Step Methodology

This protocol provides a detailed guide for each stage of the 3D-QSAR workflow, with a focus on achieving a predictive model (q² > 0.7) for tubulin inhibitors.

Data Collection and Curation

Objective: To assemble a high-quality, congeneric dataset of tubulin inhibitors with reliably measured biological activities.

- Compound Selection: Compile a series of 30-50 compounds that are structurally related but incorporate sufficient diversity in their substituents. This ensures a meaningful structure-activity relationship can be derived. The compounds should be confirmed tubulin inhibitors, targeting a specific binding site (e.g., colchicine site) to ensure a consistent mechanism of action [30] [29].

- Biological Activity Data: Collect half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) values from uniform, cell-based or biochemical assays. All data should be obtained under consistent experimental conditions to minimize noise and systemic bias. Convert IC₅₀ values to logarithmic scale (pIC₅₀ = -logIC₅₀) for modeling [30] [31].

- Dataset Division: Randomly split the dataset into a training set (≈80%) for model construction and a test set (≈20%) for external validation. The test set should never be used in any part of the model building process [32].

Molecular Modeling and Conformational Analysis

Objective: To generate representative, low-energy 3D structures for each molecule in the dataset.

- Structure Construction: Draw 2D structures of all compounds using software like ChemDraw or BIOVIA Draw [31] [32].

- 3D Geometry Optimization: Convert 2D structures into 3D coordinates using tools like RDKit or Sybyl. Subject the initial 3D structures to geometry optimization to adopt realistic, low-energy conformations. This can be achieved using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., Universal Force Field - UFF) or higher-level quantum mechanical methods for greater accuracy [30].

Molecular Alignment

Objective: To superimpose all molecules in a common 3D frame that reflects their bioactive conformation at the tubulin binding site.

- Alignment Strategy: This is the most critical and challenging step. The assumption is that all compounds share a similar binding mode.

- Atom-Based Fit: Align molecules based on a common scaffold or a known pharmacophore, often derived from a high-resolution co-crystal structure of a lead compound with tubulin [30].

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS): Use algorithms to identify the largest substructure shared among the dataset molecules and align based on this MCS [30].

- Software Tools: Utilize functions like

AllChem.ConstrainedEmbed()in RDKit or the alignment modules in commercial software like Sybyl to achieve precise spatial congruence [30].

Descriptor Calculation using CoMFA and CoMSIA

Objective: To compute 3D molecular field descriptors that numerically represent the steric and electrostatic environments of the aligned molecules.

- Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA): Place the aligned molecules within a 3D grid. A probe atom (typically an sp³ carbon with a +1 charge) is used to calculate steric (Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (Coulombic potential) interaction energies at each grid point. This results in a large table of descriptor values for each molecule [30] [31].

- Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA): As an alternative or complementary approach, CoMSIA calculates similarity indices using Gaussian-type functions. It typically evaluates five fields: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor and acceptor. CoMSIA is often more robust to minor alignment errors and can provide more interpretable insights [30] [31].

Table 1: Key 3D-QSAR Techniques and Descriptors

| Technique | Descriptor Fields | Key Characteristics | Sensitivity to Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | Steric, Electrostatic | Calculates interaction energies on a 3D grid; classic, widely used method. | Highly sensitive |

| CoMSIA | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-Bond Donor, H-Bond Acceptor | Uses Gaussian functions; avoids singularities; provides additional interaction insights. | Moderately sensitive |

Model Building and Validation

Objective: To derive a statistically significant mathematical model and rigorously validate its predictive power.

- Statistical Method: Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate the thousands of 3D descriptors with the pIC₅₀ values. PLS reduces the dimensionality of the descriptor data by projecting them onto a smaller set of latent variables that have the highest covariance with the activity [30].

- Internal Validation: Perform leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation to determine the optimal number of components and calculate the cross-validated correlation coefficient, q². A q² > 0.7 is considered a threshold for a model with high predictive power [30] [31].

q² = 1 - PRESS/SSYwhere PRESS is the sum of squared prediction errors and SSY is the sum of squared deviations of the observed activities from their mean. - External Validation: Use the withheld test set to calculate the external predictive metrics, notably R²ₜₑₛₜ and RMSEₜₑₛₜ, which assess the model's ability to predict truly novel compounds [32].

- Statistical Checks: The model should also be evaluated for goodness-of-fit (R² > 0.8) and low standard error of estimate (SEE) [31].

Table 2: Key Statistical Metrics for 3D-QSAR Model Validation

| Metric | Formula/Description | Target Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| q² | q² = 1 - PRESS/SSY | > 0.7 | Indicates high internal predictive ability via cross-validation. |

| R² | R² = 1 - RSS/TSS | > 0.8 | Measures goodness-of-fit of the model to the training data. |

| SEE | Standard Error of Estimate | As low as possible | Measures the accuracy of the model's predictions for the training set. |

| R²ₜₑₛₜ | R² for the test set predictions | > 0.6 | Measures the model's predictive power for external compounds. |

| RMSEₜₑₛₜ | Root Mean Square Error for the test set | As low as possible | Measures the average prediction error for external compounds. |

Model Interpretation and Compound Design

Objective: To translate the statistical model into visual, chemically intelligible guidance for designing new tubulin inhibitors.

- Contour Map Analysis: Visualize the CoMFA or CoMSIA results as 3D contour maps. These maps are overlaid on a reference molecule.

- Steric Fields: Green contours indicate regions where increased bulk enhances activity; yellow contours indicate regions where bulk is detrimental [30].

- Electrostatic Fields: Blue contours indicate regions where positive charge is favored; red contours indicate regions where negative charge is favored [30].

- Rational Design: Based on the contour maps, propose new derivatives of your lead tubulin inhibitor. For example, if a green steric contour is observed near a phenyl ring, consider synthesizing analogs with larger hydrophobic substituents at that position [30].

The following diagram illustrates the logical process of interpreting contour maps to design new compounds, which are then synthesized and tested, creating a feedback loop for model refinement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for 3D-QSAR Modeling

| Category | Tool/Resource | Specific Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics & Modeling | RDKit, Open Babel | File format conversion; basic molecular descriptor calculation [15] [30]. |

| 3D-QSAR & Molecular Alignment | Sybyl/X | Comprehensive suite for molecular modeling, conformational analysis, alignment, and running CoMFA/CoMSIA studies [31]. |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock Vina | To perform molecular docking studies for integrating structure-based insights or guiding alignment [15] [33]. |

| Database | ZINC Database | Source of purchasable compound structures for virtual screening [15]. |

| Statistical Analysis & Scripting | R, Python (scikit-learn) | For data preprocessing, statistical analysis, and custom machine learning scripts [15]. |

Molecular Docking Protocols for Tubulin Binding Site Characterization

Molecular docking has become an indispensable tool in structural biology and computer-aided drug design, providing critical insights into ligand-receptor interactions. For tubulin research, docking protocols enable the characterization of small molecule binding to distinct sites on the tubulin heterodimer, facilitating the development of novel anticancer and antiparasitic agents [34]. This protocol details the integration of molecular docking with three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) studies, creating a powerful framework for rational drug design targeting tubulin. The synergy between these methods allows researchers to not only predict binding poses but also understand the structural and electrostatic features governing biological activity, thereby accelerating the identification and optimization of tubulin inhibitors [3] [2].

Tubulin possesses several well-characterized binding sites, including the taxane, vinca alkaloid, and colchicine sites, each with distinct structural properties and therapeutic implications [35] [36]. Colchicine-binding site inhibitors (CBSIs) have recently gained significant attention due to their potential to overcome multidrug resistance and their antiangiogenic properties [37]. The protocol presented herein emphasizes characterization of this pharmacologically relevant site while providing principles adaptable to other tubulin binding pockets.

Theoretical Background and Significance

Microtubules, composed of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers, are dynamic cytoskeletal components essential for vital cellular processes including mitosis, intracellular transport, cell signaling, and maintenance of cell shape [37] [2]. Their critical role in cell division makes them prominent targets for anticancer therapy, with microtubule-targeting agents broadly classified into microtubule-stabilizing agents (e.g., taxanes) and microtubule-destabilizing agents (e.g., vinca alkaloids, colchicine site binders) [37].

The βIII-tubulin isotype has emerged as a particularly important target, as its overexpression in various carcinomas (e.g., ovarian, breast, lung cancers) is closely associated with resistance to taxane-based chemotherapy [15]. This relationship underscores the necessity of isotype-specific targeting strategies in overcoming treatment resistance. Molecular docking approaches enable the characterization of compound interactions with specific tubulin isotypes, guiding the development of agents capable of circumventing resistance mechanisms.