Integrating 3D-QSAR and AI for Advanced ADMET Prediction in Cancer Drug Design

This article explores the integration of three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling and Artificial Intelligence (AI) for predicting the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties of anticancer drug...

Integrating 3D-QSAR and AI for Advanced ADMET Prediction in Cancer Drug Design

Abstract

This article explores the integration of three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling and Artificial Intelligence (AI) for predicting the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties of anticancer drug candidates. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of 3D-QSAR techniques like CoMFA and CoMSIA, their application in rational drug design for targets such as Tubulin and Topoisomerase IIα, and the transformative role of Machine Learning in enhancing ADMET prediction accuracy. The content also addresses methodological challenges, optimization strategies, and validation protocols to ensure model robustness. By synthesizing insights from recent case studies and technological advances, this review serves as a comprehensive guide for leveraging computational tools to accelerate the development of safer and more effective cancer therapies.

The Critical Role of ADMET and 3D-QSAR in Modern Cancer Drug Discovery

The development of new cancer therapies remains one of the most challenging endeavors in pharmaceutical science, characterized by exceptionally high failure rates that demand innovative solutions. Oncology drug development suffers from an alarming attrition rate, with an estimated 97% of new cancer drugs failing in clinical trials and only approximately 1 in 20,000-30,000 compounds progressing from initial development to marketing approval [1]. This staggering rate of failure significantly outpaces the already low average success rates across other therapeutic areas, where less than 10% of new drug entities ultimately reach the market [1] [2]. The magnitude of this challenge underscores the critical importance of addressing fundamental inefficiencies in the drug development pipeline, particularly through enhanced predictive capabilities in early-stage compound evaluation.

The financial and temporal investments in drug development are substantial, with estimates exceeding $2.8 billion dedicated to the study and development of new drug entities, often requiring over a decade to bring a single successful drug to market [3] [1]. This investment frequently yields minimal return due to the high failure rates, creating an unsustainable model that ultimately impedes patient access to novel therapies. The root causes of this attrition are multifaceted, encompassing poor drug efficacy, unacceptable toxicity profiles, suboptimal pharmacokinetic properties, and inadequate target engagement [4] [1]. Within this challenging landscape, the accurate prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties has emerged as a crucial frontier in improving developmental outcomes, offering the potential to identify potential failures earlier in the process when resources can be more effectively allocated toward promising candidates.

Quantitative Analysis of Drug Attrition Rates

A comprehensive analysis of drug development success rates reveals both the profound challenges in oncology and emerging trends that may inform future strategies. The dynamic clinical trial success rate (ClinSR) has shown concerning trends, declining since the early 21st century before recently plateauing and demonstrating slight improvement [2]. This modest recovery suggests that evolving development approaches may be beginning to address systemic inefficiencies.

Table 1: Clinical Trial Success Rates (ClinSR) and Attrition Patterns in Drug Development

| Development Stage | Success Rate | Key Contributing Factors | Potential Improvement Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Oncology Drug Development | ~3% approval rate [1] | Poor efficacy, toxicity, resistance mechanisms, tumor heterogeneity [3] [1] | Enhanced target validation, improved preclinical models, biomarker-driven selection |

| Early-Phase Trial Screen Failures | 21.7-26.4% of consented patients [5] | Radiological findings (29.2%), biological criteria (23.8%), clinical deterioration (22.3%) [5] | Optimized referral processes, updated eligibility criteria, preliminary screening assessments |

| Anti-COVID-19 Drugs | Extremely low ClinSR [2] | Compressed development timelines, limited understanding of disease mechanisms | Traditional development paradigms despite emergency context |

| Drug Repurposing | Lower than expected success rate [2] | Inadequate understanding of new disease context, suboptimal dosing regimens | Enhanced mechanistic understanding in new indications |

Analysis of screen failure rates in early-phase trials provides additional insight into inefficiencies within the development process. Across three comprehensive cancer centers in France, 21.7-26.4% of patients who provided consent for early-phase trials ultimately failed to enroll [5]. The primary reasons for these screen failures were radiological findings (29.2%), particularly newly discovered brain metastases; biological criteria (23.8%), mainly vital organ dysfunction; and clinical deterioration (22.3%) [5]. Importantly, current eligibility criteria were found to exclude 47.5% of patients who were still alive at 6 months, raising questions about the accuracy of these criteria for patient selection in early-phase trials designed to evaluate drug tolerance and activity [5].

Table 2: Analysis of Screen Failures in Early-Phase Oncology Trials

| Screen Failure Category | Frequency (%) | Specific Reasons | Potential Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiological | 29.2% | New brain metastases (n=27), non-measurable disease (n=17), absence of target for mandatory biopsy (n=8) [5] | Updated imaging prior to referral, modernized response criteria |

| Biological | 23.8% | Vital organ dysfunction (n=34), non-vital laboratory abnormalities [5] | Earlier screening labs, protocol-specific waivers for non-critical values |

| Clinical | 22.3% | Serious/potentially life-threatening events, past medical history exclusions [5] | Comprehensive pre-screening assessments, updated comorbidity policies |

| Performance Status Deterioration | 11.9% | ECOG performance status decline between consent and screening [5] | Reduced screening timeline, interim status assessments |

The Role of ADMET Prediction in Addressing Attrition

Inadequate pharmacokinetic profiles and unanticipated toxicity account for a substantial proportion of drug candidate failures, highlighting the critical importance of robust ADMET prediction early in the development process. The integration of ADMET assessment within quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) frameworks represents a transformative approach to identifying potential liabilities before significant resources are invested in compound development. Recent advances in computational methodologies have enabled increasingly sophisticated prediction of these essential properties, allowing researchers to prioritize compounds with a higher probability of clinical success [6] [7] [8].

The fundamental premise of integrating ADMET prediction in 3D-QSAR cancer drug design is the establishment of quantitative relationships between molecular structure and pharmacokinetic/toxicological outcomes. In the development of 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives as tubulin inhibitors for breast cancer therapy, researchers employed ADMET profiling alongside QSAR modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations to comprehensively evaluate potential candidates [8]. This integrated computational approach identified specific descriptors such as absolute electronegativity and water solubility as significant influencers of inhibitory activity, achieving a predictive accuracy (R²) of 0.849 [8]. Similarly, in the design of anti-breast cancer agents based on 1,4-quinone and quinoline derivatives, ADMET properties were determined to assess the drug-candidate potential of newly designed ligands, with only one compound (ligand 5) emerging as sufficiently promising for experimental testing [6].

The application of these principles to natural product drug discovery has further demonstrated the power of integrated ADMET prediction. In studies of natural products from the NPACT database with activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines, researchers developed statistically robust QSAR models (R² = 0.666-0.669, Q²Fn = 0.686-0.714) that informed virtual screening of the COCONUT database for novel natural inhibitors [7]. Subsequent ADMET evaluation, molecular docking against human HER2 protein, and molecular dynamics simulations identified two compounds (4608 and 2710) as the most promising candidates based on their binding stability and pharmacological properties [7].

Experimental Protocols: ADMET-Centric 3D-QSAR in Oncology Drug Design

Protocol 1: Development of Robust 3D-QSAR Models with ADMET Integration

Objective: To establish validated 3D-QSAR models that incorporate ADMET parameters for predicting anti-cancer activity and pharmacokinetic profiles.

Materials and Reagents:

- Chemical dataset of known active/inactive compounds

- Computational chemistry software (Gaussian 09W, ChemOffice)

- Molecular descriptor calculation tools (PaDEL Descriptor)

- Statistical analysis package (XLSTAT or equivalent)

Procedure:

Dataset Curation and Preparation

- Collect compound structures and corresponding biological activity data (e.g., IC₅₀ against specific cancer cell lines) from validated databases such as NPACT [7]

- Convert IC₅₀ values to pIC₅₀ (-log IC₅₀) for QSAR analysis [8]

- Apply rigorous curation to remove duplicates, incorrect structures, and standardize representation

- Divide dataset using an 80:20 ratio for training and test sets to ensure robust validation [8]

Molecular Geometry Optimization and Descriptor Calculation

- Optimize molecular geometries using density functional theory (DFT) with B3LYP functional and 6-31G(p,d) basis set [8]

- Calculate electronic descriptors (Eₕₒₘₒ, Eₗᵤₘₒ, dipole moment, absolute electronegativity) using Gaussian 09W [8]

- Compute topological descriptors (molecular weight, logP, logS, polar surface area) using ChemOffice software [8]

- Generate additional descriptors using PaDEL Descriptor software for comprehensive structural representation [7]

Model Development and Validation

- Apply principal component analysis (PCA) to identify the most relevant descriptors and reduce dimensionality [8]

- Develop QSAR models using multiple linear regression (MLR) with descendant selection and variable removal [8]

- Validate models using both internal (R², Q²ₗₒₒ) and external validation (Q²Fₙ, CCCₑₓₜ) criteria [7] [8]

- Ensure statistical significance with correlation coefficients (R² > 0.8), Fisher's criteria (F), and low mean squared error (MSE) [8]

ADMET Integration and Compound Prioritization

- Predict key ADMET properties including water solubility (LogS), octanol-water partition coefficient (LogP), metabolic stability, and toxicity parameters [6] [8]

- Integrate ADMET predictions with QSAR activity models to establish multi-parameter optimization criteria

- Apply the integrated model for virtual screening of compound libraries to identify promising candidates [7]

Protocol 2: Comprehensive ADMET Profiling in Virtual Compound Screening

Objective: To implement a standardized protocol for virtual ADMET profiling of candidate compounds within a 3D-QSAR framework.

Materials:

- Curated compound library in appropriate digital format (SDF, MOL2)

- ADMET prediction software (OpenADMET, admetSAR, or equivalent)

- Molecular dynamics simulation software (GROMACS, AMBER)

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

Physicochemical Property Profiling

- Calculate fundamental physicochemical parameters including molecular weight, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, rotatable bonds, topological polar surface area (TPSA) [8]

- Predict lipophilicity (LogP) using consensus algorithms to ensure accuracy

- Estimate solubility (LogS) using quantitative predictive models [8]

Pharmacokinetic Parameter Prediction

- Predict intestinal absorption using PSA and LogP-based models

- Estimate blood-brain barrier penetration potential for CNS activity or toxicity assessment

- Simulate plasma protein binding using structure-based and machine learning approaches

- Predict metabolic stability and identify potential metabolic soft spots [6]

Toxicity Risk Assessment

Integration with 3D-QSAR and Validation

- Correlate ADMET predictions with 3D-QSAR activity models

- Establish acceptable ADMET parameter ranges for lead compounds

- Prioritize compounds satisfying both potency and ADMET criteria

- Validate predictions with limited experimental testing for key candidates

Advanced Preclinical Models for ADMET Validation

The transition from computational prediction to experimental validation requires sophisticated preclinical models that faithfully recapitulate human physiology. Advanced model systems have emerged that bridge the gap between traditional in vitro assays and in vivo responses, providing more clinically relevant data on compound behavior.

Table 3: Advanced Preclinical Models for ADMET and Efficacy Assessment

| Model System | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | High-throughput cytotoxicity screening, drug combination studies, initial efficacy assessment [4] | Reproducible, cost-effective, suitable for high-throughput applications [4] | Limited tumor heterogeneity representation, inadequate tumor microenvironment [4] |

| Organoids | Disease modeling, drug response investigation, immunotherapy evaluation, safety/toxicity studies [4] | Preserve phenotypic and genetic features of original tumor, more predictive than cell lines [4] | Complex and time-consuming to create, incomplete tumor microenvironment [4] |

| Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) Models | Biomarker discovery, clinical stratification, drug combination strategies [4] | Preserve tumor architecture and microenvironment, most clinically relevant preclinical model [4] | Expensive, resource-intensive, time-consuming, ethical considerations [4] |

| Integrated Multi-Stage Approach | Comprehensive biomarker hypothesis generation and validation [4] | Leverages advantages of each model type, builds robust pipeline for clinical translation [4] | Requires significant coordination and resources across platforms [4] |

The FDA's recent announcement regarding reduced animal testing requirements for monoclonal antibodies and other drugs, with acceptance of advanced approaches including organoids, underscores the growing importance of these human-relevant systems [4]. This regulatory evolution acknowledges the improved predictive value of these models and their potential to accelerate development while reducing costs.

Artificial Intelligence in ADMET and 3D-QSAR Modeling

Artificial intelligence has emerged as a transformative technology in drug discovery, particularly in enhancing the predictive accuracy of ADMET properties and 3D-QSAR models. AI approaches, including machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and natural language processing (NLP), are being integrated across the drug development pipeline to improve success rates by processing large datasets, identifying complex patterns, and making autonomous decisions [3] [1].

Machine learning techniques, particularly supervised learning algorithms such as support vector machines (SVMs), random forests, and deep neural networks, have demonstrated significant success in predicting bioactivity and ADMET properties [9]. These approaches enable the identification of complex, non-linear relationships between molecular structures and pharmacological outcomes that may elude traditional statistical methods. Deep learning architectures, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), have further enhanced predictive capabilities by automatically learning relevant features from raw molecular data [3] [9].

Generative models such as variational autoencoders (VAEs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) have shown particular promise in de novo molecular design, enabling the generation of novel compounds with optimized ADMET profiles [9]. These approaches can explore chemical space more efficiently than traditional high-throughput screening, focusing on regions with higher probabilities of success. Reinforcement learning (RL) methods further refine this process by iteratively proposing molecular structures and receiving feedback based on multiple optimization parameters, including potency, selectivity, and ADMET properties [3] [9].

The integration of AI into ADMET prediction has yielded tangible advances in development efficiency. Companies such as Insilico Medicine and Exscientia have reported AI-designed molecules reaching clinical trials in record times, with one example progressing in just 12 months compared to the typical 4-5 years [3]. Similar approaches are being applied specifically to oncology projects, highlighting the potential of these technologies to address the particular challenges of cancer drug development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ADMET-Centric 3D-QSAR

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Chemistry Software | Gaussian 09W, ChemOffice [8] | Molecular geometry optimization, electronic descriptor calculation | Use DFT/B3LYP/6-31G(p,d) for optimal accuracy in quantum chemical calculations [8] |

| Descriptor Calculation Tools | PaDEL Descriptor [7] | Computation of molecular descriptors for QSAR modeling | Supports 2D and 3D descriptors; enables high-throughput screening of compound libraries |

| Statistical Analysis Packages | XLSTAT [8] | Development and validation of QSAR models, principal component analysis | Provides comprehensive statistical tools for model optimization and validation |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER [6] [7] | Simulation of drug-target interactions, binding stability assessment | 100 ns simulations recommended for adequate stability assessment [6] [7] |

| ADMET Prediction Platforms | OpenADMET, admetSAR | Prediction of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity | Use consensus approaches from multiple platforms for improved prediction accuracy |

| Specialized Cell Line Panels | CrownBio's cell line database [4] | Initial efficacy screening, biomarker correlation studies | Includes >500 genomically diverse cancer cell lines for comprehensive profiling [4] |

| Organoid Biobanks | CrownBio's organoid database [4] | Disease modeling, drug response investigation, toxicity assessment | Preserves phenotypic and genetic features of original tumors [4] |

| PDX Model Collections | CrownBio's PDX database [4] | Preclinical efficacy validation, biomarker discovery | Considered gold standard for preclinical research; preserves tumor microenvironment [4] |

The integration of ADMET prediction within 3D-QSAR modeling frameworks represents a paradigm shift in addressing the critical challenge of high attrition rates in oncology drug development. By frontloading ADMET assessment in the discovery process, researchers can identify potential liabilities earlier, prioritize compounds with higher probabilities of clinical success, and ultimately reduce the costly late-stage failures that have plagued oncology drug development. The combined power of advanced computational modeling, sophisticated preclinical systems, and artificial intelligence creates an unprecedented opportunity to transform the efficiency and success of cancer therapeutic development.

Future directions in this field will likely focus on the continued refinement of multi-parameter optimization algorithms that simultaneously balance potency, selectivity, and ADMET properties. The integration of multi-omics data into predictive models will further enhance their clinical relevance, while human-on-a-chip and microphysiological systems may provide even more sophisticated platforms for experimental ADMET validation. As these technologies mature, they hold the promise of fundamentally reshaping oncology drug development, potentially reversing the trend of high attrition rates and accelerating the delivery of effective therapies to cancer patients.

In the modern paradigm of cancer drug design, efficacy is only one part of the equation. A compound's success is equally dependent on its Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties, which collectively define its pharmacokinetic and safety profile [10]. Historically, a significant number of clinical failures have been attributed to unfavorable ADMET characteristics, underscoring the critical need for their early assessment in the drug discovery pipeline [10] [11]. Within cancer research, particularly in projects utilizing 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling, integrating ADMET prediction has become indispensable for optimizing lead compounds and reducing late-stage attrition [12] [8]. This Application Note details the practical integration of ADMET evaluation within 3D-QSAR-driven cancer drug discovery, providing structured data, definitive protocols, and essential tools for research scientists.

Core ADMET Properties in Cancer Drug Design

The following table summarizes the key ADMET properties, their definitions, and their specific significance in the context of developing oncology therapeutics.

Table 1: Key ADMET Properties and Their Role in Cancer Drug Design

| Property | Definition | Significance in Cancer Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Absorption | The process by which a drug enters the systemic circulation from its site of administration [10]. | While IV administration is common, oral bioavailability is increasingly desired for patient convenience and chronic dosing [10]. |

| Distribution | The reversible transfer of a drug between the bloodstream and various tissues [10]. | Influences drug concentration at the tumor site. High plasma protein binding (e.g., to HSA or AAG) can restrict distribution [10]. |

| Metabolism | The enzymatic conversion of a drug into metabolites [10]. | Impacts exposure and duration of action. Inhibition of Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes is a major source of drug-drug interactions [10]. |

| Excretion | The removal of the drug and its metabolites from the body [10]. | Renal and biliary/hepatic are primary routes. Transporters like P-gp can affect elimination and contribute to resistance [10]. |

| Toxicity | The potential of a drug to cause harmful effects [10]. | Includes organ-specific toxicity, genotoxicity (e.g., Ames test), and cardiotoxicity (e.g., hERG channel inhibition) [13]. |

Integrated Computational Protocols for 3D-QSAR and ADMET

The synergy between 3D-QSAR and ADMET modeling allows for the simultaneous optimization of a compound's potency and its pharmacokinetic profile. Below are detailed protocols for conducting these analyses.

Protocol 1: Developing a 3D-QSAR Model with ADMET Outlook

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a 3D-QSAR model with an emphasis on generating insights applicable to ADMET optimization [14] [12] [8].

Dataset Curation and Biological Activity

- Collect a series of compounds (typically 30-50) with known experimental biological activity (e.g., IC50 or MIC) against the cancer target of interest [14] [8].

- Convert the activity values to pIC50 (or pMIC) using the formula: pIC50 = -log10(IC50) for use as the dependent variable in the model [14] [8].

- Divide the dataset into a training set (≈80%) for model building and a test set (≈20%) for external validation [12] [8].

Molecular Modeling and Alignment

- Sketch and optimize the 3D structures of all compounds using software like SYBYL-X or Gaussian with a standardized method (e.g., Tripos force field or DFT/B3LYP/6-31G) [12] [8].

- Perform molecular alignment, which is a critical step. A common method is rigid body alignment based on a common scaffold or a putative pharmacophore [12].

Field Calculation and Model Generation

- Calculate molecular interaction fields using Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) [14] [12].

- For CoMFA, compute steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields. For CoMSIA, additional fields like hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and acceptor can be used [14] [12].

- Use the Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression method to correlate the field descriptors with the biological activity and generate the statistical model [12].

Model Validation and Interpretation

- Validate the model using Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation to determine the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²). A Q² > 0.5 is generally considered acceptable [12].

- Calculate the non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (R²) and assess the predictive R² for the test set [12].

- Interpret the contour maps (e.g., green/yellow for favorable/unfavorable steric, blue/red for favorable/unfavorable electrostatic) to guide structural modifications for enhanced potency [12].

Protocol 2: Predicting and Analyzing ADMET Properties

This protocol describes the use of computational tools to evaluate the ADMET profile of compounds, either during or after the 3D-QSAR analysis [8] [13] [15].

Descriptor Calculation

- Calculate key physicochemical and topological descriptors for your compound set. Essential descriptors include:

In Silico ADMET Prediction

Data Integration and Compound Prioritization

- Compile the ADMET predictions and physicochemical data into a unified table.

- Filter compounds based on desirable ADMET profiles. For instance, apply rules like Lipinski's Rule of Five to prioritize compounds with drug-like properties [12] [15].

- Correlate favorable and unfavorable ADMET traits with structural features identified in the 3D-QSAR contour maps. This integrated analysis provides a powerful strategy for designing new analogs with balanced potency and pharmacokinetics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Successful implementation of the protocols above relies on a suite of computational tools and resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated 3D-QSAR and ADMET Studies

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL-X | Software Suite | Industry-standard platform for molecular modeling, alignment, and performing CoMFA/CoMSIA studies [12]. |

| Gaussian 09W | Software | Performs quantum mechanical calculations (e.g., DFT) to compute electronic descriptors for QSAR [8]. |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio | Software Suite | Provides comprehensive tools for calculating ADMET descriptors, predictive toxicity (TOPKAT), and analyzing QSAR models [13]. |

| AutoDock Vina/InstaDock | Software | Conducts molecular docking simulations to predict binding modes and affinities of compounds to target proteins [17] [12]. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software | Generates a wide range of molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures for QSAR and machine learning [17]. |

| SwissADME / ADMETlab 3.0 | Web Server | Provides fast, user-friendly predictions of key pharmacokinetic and physicochemical properties [16]. |

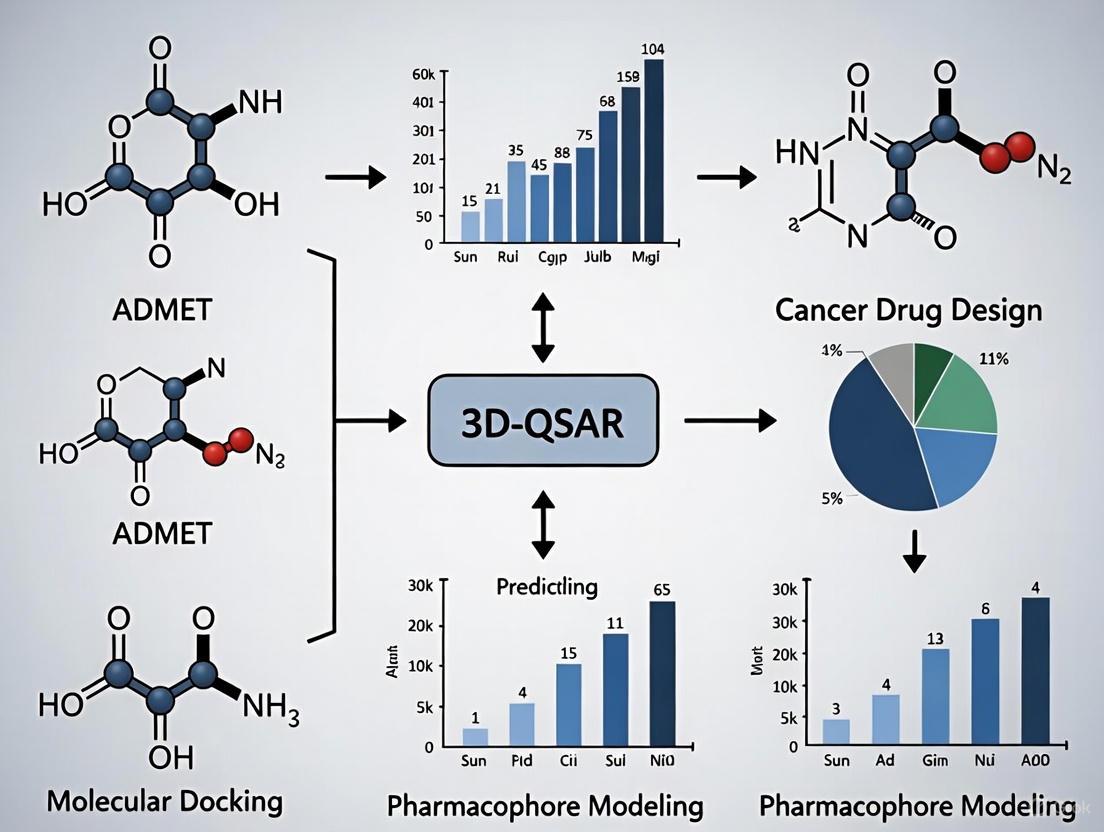

Visualizing the Workflow: From Chemical Structure to Optimized Candidate

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow combining 3D-QSAR modeling and ADMET prediction in cancer drug design.

Integrated 3D-QSAR and ADMET Workflow

Advanced Frontiers: AI and Federated Learning in ADMET Prediction

The field of ADMET prediction is being transformed by artificial intelligence (AI). Advanced deep learning models, such as the MSformer-ADMET, utilize a fragmentation-based approach for molecular representation, achieving superior performance across a wide range of ADMET endpoints by effectively modeling long-range dependencies [18]. Furthermore, the challenge of limited and heterogeneous data is being addressed through federated learning. This technique allows multiple pharmaceutical organizations to collaboratively train machine learning models on their distributed, proprietary datasets without sharing the underlying data, significantly expanding the model's chemical space coverage and predictive robustness for novel compounds [11]. The integration of AI-augmented PBPK models also shows great promise, enabling the prediction of a drug's full pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile directly from its structural formula early in the discovery stage [16].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of computational medicinal chemistry, mathematically linking a chemical compound's structure to its biological activity or properties [19]. While traditional 2D-QSAR utilizes molecular descriptors derived from two-dimensional structures, Three-Dimensional QSAR (3D-QSAR) has emerged as a pivotal advancement that incorporates the essential spatial characteristics of molecules. These techniques are particularly valuable in cancer drug discovery, where understanding the intricate interactions between potential drug candidates and their biological targets is crucial for designing effective therapeutics with optimized ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties [20].

The fundamental principle underlying 3D-QSAR is that biological activity correlates not only with chemical composition but profoundly with three-dimensional molecular structure, including steric (shape-related) and electrostatic (charge-related) features. This approach operates on the concept that a ligand's interaction with a biological target depends on its ability to fit spatially and electronically into a binding site [21]. In the context of cancer research, 3D-QSAR enables researchers to systematically explore structural requirements for inhibiting specific oncology targets, thereby guiding the rational design of novel anticancer agents with improved potency and selectivity.

Among various 3D-QSAR methodologies, Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) have become the most widely adopted and validated approaches. These techniques have demonstrated significant utility across multiple cancer types, including breast cancer [22] [8] [23], chronic myeloid leukemia [24], and osteosarcoma [25], providing medicinal chemists with powerful tools to accelerate anticancer drug development while reducing reliance on costly synthetic experimentation.

Theoretical Foundations of CoMFA and CoMSIA

Core Conceptual Framework

The CoMFA methodology, introduced in the 1980s, is founded on the concept that molecular interaction fields surrounding ligands constitute the primary determinants of biological activity. This approach assumes that the non-covalent interaction between a ligand and its receptor can be approximated by steric and electrostatic forces [21]. In practice, CoMFA characterizes molecules based on their steric (van der Waals) and electrostatic (Coulombic) potentials sampled at regularly spaced grid points surrounding the molecules. These potentials are calculated using probe atoms and are correlated with biological activity through Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, generating a model that visualizes regions where specific structural modifications would enhance or diminish biological activity [24].

CoMSIA emerged as an extension and refinement of CoMFA, addressing some of its limitations by introducing Gaussian-type distance dependence and additional molecular field types. While CoMFA utilizes Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials that can exhibit sharp fluctuations near molecular surfaces, CoMSIA employs a smoother potential function that avoids singularities and provides more stable results [26]. Beyond the steric and electrostatic fields shared with CoMFA, CoMSIA typically incorporates hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields, offering a more comprehensive description of ligand-receptor interactions [26].

Comparative Analysis of CoMFA and CoMSIA

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between CoMFA and CoMSIA Approaches

| Feature | CoMFA | CoMSIA |

|---|---|---|

| Field Types | Steric, Electrostatic | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, Hydrogen Bond Donor, Hydrogen Bond Acceptor |

| Potential Function | Lennard-Jones, Coulomb | Gaussian-type |

| Distance Dependence | Proportional to 1/r^n | Exponential decay |

| Grid Calculations | Probe atom interactions at grid points | Similarity indices calculated at grid points |

| Results Stability | Sensitive to molecular orientation | Less sensitive to alignment |

| Contour Maps | Sometimes discontinuous | Generally smooth and interpretable |

The selection between CoMFA and CoMSIA depends on the specific research context. CoMFA often provides models with high predictive ability for congeneric series, while CoMSIA can capture more complex interactions through its additional fields and may be more suitable for structurally diverse datasets [26]. In cancer drug design, both techniques have demonstrated excellent predictive capabilities, with recent studies reporting statistically robust models with correlation coefficients (R²) often exceeding 0.85-0.90 and cross-validated coefficients (Q²) above 0.5 [26] [25] [24].

Computational Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Workflow for 3D-QSAR Analysis

The development of robust 3D-QSAR models follows a systematic workflow encompassing multiple critical stages. Adherence to this protocol ensures the generation of statistically significant and predictive models that can reliably guide cancer drug design efforts.

Figure 1: Standard workflow for developing 3D-QSAR models using CoMFA and CoMSIA methodologies.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Dataset Compilation and Preparation

- Compound Selection: Curate a structurally diverse set of 20-100 compounds with consistent, quantitatively measured biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) against the cancer target of interest [25] [24]. The activities are typically converted to pIC₅₀ (-logIC₅₀) for analysis.

- Training/Test Set Division: Implement a rational division (typically 80:20 ratio) to ensure the test set represents the structural diversity and activity range of the training set [8]. Random sampling based on system time or activity-based sorting followed by regular interval selection are common approaches [25].

Step 2: Molecular Modeling and Conformational Analysis

- Structure Building: Construct molecular structures using chemoinformatics software (ChemDraw, Sybyl-X, HyperChem) [26] [25].

- Geometry Optimization: Perform molecular mechanics (MM+ force field) for preliminary optimization followed by semi-empirical (AM1 or PM3) or DFT (B3LYP/6-31G) methods for precise geometry optimization [25] [8].

- Conformational Analysis: Identify the bioactive conformation through systematic search, molecular dynamics, or by extracting from crystallographic complexes when available [27].

Step 3: Molecular Alignment

- Atom-Based Fit: Align molecules based on common substructure or pharmacophore using RMSD atom fitting [24].

- Field Fit: Use the field points themselves to guide alignment [21].

- Database Alignment: Align to a known active compound or native ligand [26]. This step is critically important as alignment quality directly impacts model performance.

Step 4: Field Calculations and Descriptor Generation

- CoMFA Field Calculation:

- Place aligned molecules in a 3D grid (typically 2.0 Å spacing)

- Calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) potentials using sp³ carbon and +1 charge probes

- Set energy cutoffs (30 kcal/mol) to avoid extreme values [24]

- CoMSIA Field Calculation:

- Calculate five similarity fields: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, hydrogen bond acceptor

- Use Gaussian-type distance dependence with attenuation factor (typically 0.3) [26]

Step 5: Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis

- Variable Preprocessing: Apply standard scaling (Coefficient × STDEV) to field values [24]

- PLS Regression: Correlate field variables with biological activity while addressing multicollinearity

- Optimal Component Determination: Use cross-validation (leave-one-out or leave-group-out) to identify components maximizing Q² [26] [24]

Step 6: Model Validation and Evaluation

- Internal Validation: Assess using cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²), conventional correlation coefficient (R²), standard error of estimate (SEE), and F-value [26]

- External Validation: Predict test set activities and calculate predictive R² (R²pred) [8]

- Robustness Testing: Apply Y-randomization to confirm model non-randomness [23]

Application to ADMET Property Prediction in Cancer Research

The integration of 3D-QSAR with ADMET profiling represents a powerful strategy in cancer drug design, enabling simultaneous optimization of both efficacy and safety profiles. Recent studies have successfully implemented this integrated approach:

Table 2: 3D-QSAR Applications in Cancer Drug Discovery with ADMET Integration

| Cancer Type | Target | Compound Series | Key ADMET Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Tubulin (Colchicine site) | 1,2,4-Triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives | Absolute electronegativity (χ) and water solubility (LogS) significantly influence activity; optimized compounds showed favorable pharmacokinetic profiles | [8] |

| Breast Cancer | Aromatase | Heterocyclic derivatives | QSAR-ANN models combined with ADMET prediction identified candidate L5 with improved metabolic stability | [23] |

| Chronic Myeloid Leukemia | Bcr-Abl | Purine derivatives | CoMFA/CoMSIA guided design of compounds with enhanced potency against T315I mutant and reduced cytotoxicity | [24] |

| Breast Cancer | Topoisomerase IIα | Naphthoquinone derivatives | ADMET screening of 2300 compounds identified 16 promising candidates; molecular dynamics confirmed stability | [22] |

In practice, 3D-QSAR models can directly predict ADMET-related properties by using pharmacokinetic parameters (e.g., solubility, permeability, metabolic stability) as the dependent variable instead of biological activity. This application is particularly valuable in cancer drug design, where therapeutic windows are often narrow and toxicity concerns are paramount.

Successful implementation of 3D-QSAR studies requires access to specialized software tools and computational resources. The following table summarizes key components of the 3D-QSAR research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Resources | Primary Function | Application in Protocol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | ChemDraw, HyperChem, Sybyl-X | Structure building, preliminary optimization | Steps 1-2: Compound construction and geometry optimization | [26] [25] |

| Quantum Chemical | Gaussian 09W, AM1, PM3 methods | High-level geometry optimization, electronic property calculation | Step 2: Precise molecular structure optimization | [8] |

| 3D-QSAR Specific | CORAL, COMSIA/Sybyl, CODESSA | Descriptor calculation, model development | Steps 3-5: Field calculation, PLS analysis, model generation | [22] [25] |

| Molecular Descriptors | PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, RDKit | Calculation of diverse molecular descriptors | Alternative descriptor sources for comparative modeling | [19] |

| Docking & Dynamics | AutoDock, GROMACS, AMBER | Protein-ligand interaction analysis, binding stability assessment | Post-QSAR validation of designed compounds | [22] [8] |

| Statistical Analysis | XLSTAT, inbuilt PLS in QSAR packages | Statistical correlation, model validation | Step 6: Model validation and statistical analysis | [8] |

Case Study: 3D-QSAR in Breast Cancer Tubulin Inhibitor Design

A recent investigation on 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives as tubulin inhibitors for breast cancer therapy exemplifies the integrated application of 3D-QSAR in oncology drug discovery [8]. This study developed robust QSAR models achieving a predictive accuracy (R²) of 0.849, identifying absolute electronegativity and water solubility as critical determinants of inhibitory activity. The subsequent molecular docking revealed compound Pred28 with exceptional binding affinity (-9.6 kcal/mol) to the tubulin colchicine site, while ADMET profiling confirmed favorable pharmacokinetic properties.

The research workflow incorporated:

- 3D-QSAR Model Development: Using a dataset of 32 compounds with anti-MCF-7 activity

- Descriptor Selection: Combining electronic (EHOMO, ELUMO, electronegativity) and topological (LogP, LogS, polar surface area) descriptors

- Model Validation: Rigorous internal and external validation following OECD principles

- Molecular Dynamics: 100 ns simulations confirming complex stability (RMSD 0.29 nm)

- ADMET Integration: Comprehensive pharmacokinetic prediction guiding compound selection

This case demonstrates how 3D-QSAR serves as the central component in a multi-technique computational framework, efficiently bridging structural optimization with pharmacological profiling in cancer drug design.

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives in Cancer Therapeutics

The continuing evolution of 3D-QSAR methodologies promises enhanced capabilities for anticancer drug development. Emerging trends include:

- 4D-QSAR Approaches: Incorporating ensemble sampling of multiple ligand conformations to account for flexibility [20]

- QSAR-ANN Integration: Combining 3D-QSAR with artificial neural networks to capture non-linear structure-activity relationships [23]

- Hybrid QSAR-Docking Models: Leveraging both ligand-based and structure-based design principles [22] [24]

- Multi-Target QSAR: Developing models that simultaneously optimize activity against multiple cancer targets while maintaining favorable ADMET profiles

These advanced applications position 3D-QSAR as an increasingly indispensable component of integrated cancer drug discovery platforms, potentially accelerating the development of novel therapeutics with optimized efficacy and safety profiles.

Why 3D-QSAR is Uniquely Suited for Modeling Ligand-Receptor Interactions

Abstract Within the paradigm of cancer drug design, predicting ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties is crucial for lead optimization. This application note posits that 3D-QSAR (Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship) is uniquely suited for modeling the foundational event of this process: ligand-receptor interactions. By explicitly incorporating the spatial and electronic fields of molecules, 3D-QSAR provides a superior framework for understanding and predicting biological activity, thereby directly informing ADMET characteristics. We detail the protocols and experimental rationale for employing 3D-QSAR in this context.

1. Introduction: The 3D-QSAR Advantage in ADMET Prediction Traditional 2D-QSAR relies on molecular descriptors derived from a compound's topological structure, which often fail to capture the stereoelectronic complementarity essential for ligand-receptor binding. In cancer drug design, where targets are often kinases, GPCRs, or nuclear receptors, this spatial recognition is paramount. 3D-QSAR techniques, such as Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), model biological activity as a function of interaction fields (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, etc.) surrounding a set of aligned molecules. This directly mirrors the physical reality of the receptor binding pocket, making it exceptionally powerful for predicting binding affinity—a key driver of many ADMET properties.

2. Application Notes: Correlating 3D Fields with ADMET Endpoints The following table summarizes how specific 3D-QSAR field contributions can be mapped to critical ADMET parameters in oncology drug discovery.

Table 1: Mapping 3D-QSAR Field Contributions to ADMET Properties

| ADMET Property | Relevant 3D-QSAR Field | Correlation & Rationale | Exemplary Statistical Output (Hypothetical Dataset) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption (Caco-2 Permeability) | Hydrophobic (CoMSIA) | Positive contribution in specific regions indicates enhanced passive transcellular diffusion. | q² = 0.72, R² = 0.88, Hydrophobic Contour: 45% |

| hERG Channel Inhibition (Cardiotoxicity) | Electrostatic (CoMFA/CoMSIA) | Presence of negative electrostatic potential near a basic nitrogen correlates with hERG binding. | q² = 0.68, R² = 0.85, Electrostatic Contour: 60% |

| CYP3A4 Inhibition (Metabolism) | Steric & Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Bulky groups in defined regions block access; H-bond acceptors coordinate heme iron. | q² = 0.65, R² = 0.82, Steric Contour: 30%, H-Bond Acceptor: 25% |

| Plasma Protein Binding (Distribution) | Hydrophobic & Electrostatic | Extensive hydrophobic fields increase binding to albumin; negative charges to α1-acid glycoprotein. | q² = 0.70, R² = 0.86, Hydrophobic Contour: 50% |

3. Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard CoMFA/CoMSIA Workflow for Kinase Inhibitor Design This protocol outlines the steps for developing a 3D-QSAR model to predict the inhibitory activity (IC₅₀) of a congeneric series of kinase inhibitors, with simultaneous assessment of hERG liability.

I. Ligand Preparation & Conformational Analysis

- Data Curation: Compile a dataset of 40-50 compounds with experimentally determined IC₅₀ values against the target kinase and hERG. Ensure a ~4 log unit spread in activity.

- Structure Preparation: Draw or import all 2D structures into a molecular modeling suite (e.g., Schrödinger Maestro, SYBYL-X). Generate plausible 3D geometries using a force field (e.g., MMFF94s).

- Energy Minimization: Optimize each structure to a gradient convergence of 0.05 kcal/mol·Å.

- Partial Charge Assignment: Calculate Gasteiger-Marsili or AM1-BCC partial charges.

II. Molecular Alignment (The Critical Step)

- Select a Template: Choose the most active and rigid molecule as the template for alignment.

- Common Substructure Alignment: Identify a common pharmacophore or scaffold present in all molecules. Superimpose all molecules onto this scaffold of the template.

- Database Alignment: Save the aligned molecule set for CoMFA/CoMSIA analysis.

III. Field Calculation & PLS Analysis

- CoMFA Setup: Place aligned molecules in a 3D grid (2.0 Å spacing). A sp³ carbon probe with a +1 charge calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields.

- CoMSIA Setup (Optional): Calculate similarity indices for steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor fields (probe radius 1.0 Å, attenuation factor 0.3).

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis: The software correlates the field values (independent variables) with the pIC₅₀ values (dependent variable). Use Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation to determine the optimal number of components (ONC) and calculate q².

- Model Generation: Run a conventional analysis using the ONC to generate the final model with R², standard error of estimate, and F-value.

IV. Model Validation & Visualization

- External Validation: Predict the activity of a test set of 10-15 compounds not used in model building. Calculate predictive R² (R²pred).

- Contour Map Analysis: Visualize the CoMFA/CoMSIA steric (green/yellow) and electrostatic (blue/red) contour maps around the template. Green contours indicate regions where bulky groups increase activity; blue contours indicate regions where positive charge increases activity.

4. Visualizing the 3D-QSAR Workflow and ADMET Integration

Title: 3D-QSAR-ADMET Workflow

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for 3D-QSAR in Cancer Drug Discovery

| Item / Solution | Function / Rationale | Example Vendor / Product |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Suite | Integrated platform for ligand preparation, alignment, force field calculation, and 3D-QSAR analysis. | Schrödinger Maestro, OpenEye Orion, BIOVIA Discovery Studio |

| Crystallographic Protein Database (PDB) | Source of high-resolution receptor structures for guiding molecular alignment and validating contour maps. | RCSB Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) |

| Standardized Bioassay Data | Curated datasets of IC₅₀, Ki, etc., for model training and validation. Critical for a robust model. | ChEMBL, PubChem BioAssay |

| Force Field Parameters | Set of mathematical functions and constants for calculating molecular energy and geometry. | MMFF94s, OPLS4, GAFF |

| PLS Analysis Toolkit | Statistical engine for correlating thousands of field variables with biological activity. | Integrated within major modeling suites (e.g., SYBYL) |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Accelerates computationally intensive steps like conformational search and cross-validation. | Local or cloud-based Linux clusters |

The integration of three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling with Artificial Intelligence (AI) represents a paradigm shift in computational drug discovery, particularly within oncology research. This powerful synergy is transforming the design and optimization of cancer therapeutics by enhancing predictive accuracy while simultaneously addressing the critical pharmacokinetic and safety profiles essential for clinical success [28]. Traditional 3D-QSAR approaches, including Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), establish correlations between the spatial and electrostatic properties of molecules and their biological activity [24]. When augmented by AI algorithms, these models gain unprecedented capability to navigate complex chemical spaces and identify novel compounds with optimized target affinity and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties [29] [9]. This application note details protocols and case studies demonstrating the effective confluence of these technologies in cancer drug design, providing researchers with practical frameworks for implementation.

Computational Methodologies and Workflows

Integrated 3D-QSAR and AI Protocol

The following workflow outlines a standardized protocol for leveraging integrated 3D-QSAR and AI in cancer drug discovery projects. This methodology has been validated across multiple kinase inhibitor development programs [24] [23].

Protocol 1: Integrated Model Development and Validation

Step 1: Compound Selection and Preparation

- Select a structurally diverse dataset of 50-100 compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) [24].

- Prepare all molecular structures using molecular mechanics force fields (MMFF94 or OPLS4) for energy minimization.

- Perform molecular alignment using common scaffold-based or field-based methods to ensure consistent orientation within the molecular grid.

Step 2: 3D-QSAR Model Construction

- Calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) field energies at grid points surrounding the aligned molecules.

- Apply Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate field descriptors with biological activity.

- Validate models using leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation and external test sets (minimum q² > 0.5, R² > 0.8) [24].

Step 3: AI-Enhanced Feature Optimization

- Extract contour maps highlighting regions where steric bulk or specific electrostatic charges enhance or diminish activity.

- Use these pharmacophoric patterns as feature inputs for graph neural networks (GNNs) or random forest algorithms [28] [9].

- Implement automated machine learning (AutoML) platforms such as DeepAutoQSAR to optimize descriptor selection and model architecture [30].

Step 4: Virtual Compound Design and Screening

- Apply trained AI models to generate novel virtual compounds or screen large chemical libraries (>10⁶ compounds).

- Prioritize candidates based on predicted activity and synthetic accessibility scores.

- Output top candidates for synthesis and biological validation.

ADMET Integration Protocol

Early integration of ADMET prediction is crucial for reducing late-stage attrition in oncology drug development [31] [32].

Protocol 2: AI-Driven ADMET Profiling

Step 1: Multi-Endpoint ADMET Prediction

Step 2: ADMET Risk Scoring

- Implement integrated risk assessment algorithms that combine multiple ADMET parameters into unified risk scores [31].

- Apply "soft" thresholding where predictions falling in intermediate ranges contribute fractional amounts to the overall risk score.

- Calculate specific risk components (AbsnRisk, CYPRisk, TOXRisk) and combine into a comprehensive ADMETRisk score [31].

Step 3: Multi-Parameter Optimization

- Employ AI-based consensus scoring to balance potency predictions with ADMET profiles [9] [32].

- Use reinforcement learning to iteratively refine compound structures toward optimal activity-ADMET trade-offs.

- Apply explainable AI (XAI) methods (SHAP, LIME) to identify structural features driving both activity and toxicity predictions [28].

Case Study: Bcr-Abl Inhibitors for Leukemia Therapy

A recent investigation developed novel Bcr-Abl inhibitors to combat imatinib resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia, demonstrating the power of integrated 3D-QSAR and AI methodologies [24].

Experimental Implementation

- Dataset: 58 purine-based Bcr-Abl inhibitors with experimentally determined IC₅₀ values

- 3D-QSAR Models: CoMFA and CoMSIA with steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields

- Statistical Validation: CoMFA (q² = 0.62, R² = 0.98); CoMSIA (q² = 0.59, R² = 0.97) [24]

- AI Integration: Molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations to validate binding modes

- ADMET Profiling: Comprehensive toxicity and pharmacokinetic assessment including plasma protein binding and metabolic stability

Key Quantitative Results

Table 1: Experimental Results for Selected Designed Purine Derivatives [24]

| Compound | Bcr-Abl IC₅₀ (μM) | Cellular GI₅₀ (μM) | Selectivity Index | ADMET Risk Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7a | 0.13 | 0.45 | 12.3 | 2.1 |

| 7c | 0.19 | 0.30 | 15.8 | 1.8 |

| 7e | 0.42 | 13.80 | 4.2 | 3.5 |

| Imatinib | 0.33 | 0.85 | 8.5 | 2.8 |

Table 2: Predicted ADMET Properties for Lead Compounds [31] [24]

| Property | 7a | 7c | Imatinib | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Permeability | 22.5 | 25.8 | 18.3 | >15 |

| hERG Inhibition | Low | Low | Medium | Low |

| CYP3A4 Inhibition | Moderate | Low | High | Low |

| Hepatotoxicity | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Plasma Protein Binding (%) | 88.2 | 85.6 | 92.5 | <95 |

| Human Absorption (%) | 75.4 | 82.1 | 98.3 | >70 |

The 3D-QSAR contour maps revealed critical structural requirements: favorable steric bulk near the C2 position, electron-donating groups at the C6 phenylamino fragment, and limited hydrophobicity at the N9 substituent [24]. These insights directly informed the AI-driven design of compounds 7a and 7c, which exhibited superior potency and selectivity compared to imatinib, particularly against resistant cell lines expressing the T315I mutation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Integrated 3D-QSAR/AI Research

| Tool Category | Representative Solutions | Key Functionality |

|---|---|---|

| 3D-QSAR Platforms | SYBYL, Open3DQSAR | CoMFA, CoMSIA, molecular field calculation, pharmacophore mapping |

| AI/ML Modeling | DeepAutoQSAR [30], Chemprop [33], Receptor.AI [32] | Automated machine learning, graph neural networks, multi-task learning |

| ADMET Prediction | ADMET Predictor [31], ADMETlab 3.0 [33], ProTox 3.0 [33] | Prediction of 175+ ADMET properties, risk assessment, species-specific modeling |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, Desmond, OpenMM | Binding mode validation, free energy calculations, conformational sampling |

| Cheminformatics | RDKit, KNIME [28], PaDEL | Descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, data preprocessing |

Workflow Visualization

Integrated 3D-QSAR and AI Workflow

AI-Driven ADMET Assessment Pathway

The strategic integration of 3D-QSAR modeling with artificial intelligence represents a transformative advancement in cancer drug design. This synergistic approach enables researchers to simultaneously optimize for target potency and drug-like properties, significantly improving the efficiency of the lead discovery and optimization process. The protocols and case studies presented herein provide a practical framework for implementing these methodologies, with particular emphasis on addressing the critical challenge of ADMET prediction in oncology research. As AI technologies continue to evolve and experimental datasets expand, this confluence promises to further accelerate the development of safer, more effective cancer therapeutics.

A Practical Workflow: Applying 3D-QSAR and ML for ADMET Optimization

In modern cancer drug design, the prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties has become a critical determinant of success, with approximately 40-45% of clinical attrition still attributed to ADMET liabilities [11] [34]. Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling represents a sophisticated computational approach that transcends traditional 2D methods by incorporating the spatial characteristics of molecules, thereby providing more accurate predictions of their biological activity and pharmacological properties [35] [36]. When strategically integrated with ADMET prediction platforms, 3D-QSAR forms a powerful framework for prioritizing drug candidates with optimal efficacy and safety profiles early in the discovery pipeline [34].

The significance of robust 3D-QSAR modeling is particularly evident in oncology drug development, where success rates remain well below the already low 10% average for new chemical entities [1]. This application note provides a comprehensive protocol for constructing, validating, and implementing 3D-QSAR models within the context of cancer drug discovery, with emphasis on ADMET property prediction to reduce late-stage failures.

Dataset Curation and Preparation

Compound Selection and Activity Data

The foundation of any predictive 3D-QSAR model lies in the quality and relevance of the training dataset. For cancer drug design, select compounds with:

- Consistent biological activity data (IC₅₀, EC₅₀, or Kᵢ) obtained from uniform experimental assays targeting relevant oncology targets (e.g., aromatase for breast cancer [23] or Mcl-1 for leukemia [37])

- Structural diversity covering multiple chemotypes and scaffolds to ensure broad applicability domain

- Potency range spanning at least 3-4 orders of magnitude to capture meaningful structure-activity relationships [38]

Table 1: Activity Data Preparation Standards

| Parameter | Requirement | Processing Method |

|---|---|---|

| Activity Values | Experimentally consistent IC₅₀/Kᵢ | Convert to pIC₅₀ or pKᵢ (-log10) [38] |

| Value Range | Minimum 3-order magnitude spread | Logarithmic transformation |

| Data Source | Homogeneous assay conditions | Curate from single source or normalize cross-dataset |

Molecular Modeling and Conformation Generation

Accurate 3D molecular representation is essential for meaningful steric and electrostatic field analysis:

- Structure Building: Construct initial 3D structures using molecular modeling software (ChemDraw, Sybyl-X [35] or Schrodinger Suite [38])

- Geometry Optimization: Perform energy minimization using molecular mechanics force fields (MMFF94 or OPLS4) to obtain low-energy conformations [38]

- Conformational Sampling: Generate representative ligand conformations considering biological flexibility requirements [35]

Molecular Alignment

Molecular alignment is the most critical step in 3D-QSAR model development, directly determining model interpretability and predictive power:

- Identify a rigid reference compound with high activity and structural similarity to other dataset members

- Extract common substructure or pharmacophoric features shared across the dataset

- Align all molecules using flexible ligand alignment algorithms [38] or crystallographic pose-based alignment when receptor structure is available

Model Building and Validation

Field Calculation and Descriptor Generation

Modern 3D-QSAR approaches utilize sophisticated field calculation methods:

- Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA): Calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) potentials at grid points surrounding aligned molecules [35]

- Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA): Extends beyond CoMFA to include hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and acceptor fields [35]

- Machine Learning-Enhanced 3D-QSAR: Incorporate 3D descriptors into ML algorithms (Random Forest, SVM, Multilayer Perceptron) for improved predictive performance [36]

Statistical Modeling and Validation

Robust model validation is essential for ensuring predictive reliability:

Table 2: 3D-QSAR Model Validation Parameters and Benchmarks

| Validation Type | Statistical Metric | Acceptance Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation | q² (LOO cross-validation) | > 0.5 | Good predictive ability |

| Goodness of Fit | r² (conventional) | > 0.8 | High explanatory power |

| Model Stability | F-value | Higher = better | Statistical significance |

| Standard Error | SEE | Lower = better | Model precision |

| External Validation | Predictive r² (r²pred) | > 0.6 | Good external predictivity |

The model development process should yield statistically significant parameters, such as those demonstrated in a recent neuroprotective drug study where the CoMSIA model achieved q² = 0.569 and r² = 0.915 [35], or in anticancer research where models underwent "rigorous internal and external validations based on significant statistical parameters" [23].

Machine Learning Integration in 3D-QSAR

Machine learning algorithms significantly enhance traditional 3D-QSAR approaches:

- Algorithm Selection: Implement Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), or Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) based on dataset characteristics [36] [39]

- Feature Importance Analysis: Employ SHAP analysis or similar methods to identify key descriptors influencing predictions [39]

- Model Interpretation: Combine predictive power with mechanistic insights into structure-activity relationships [39]

Recent studies demonstrate that "3D-QSAR models, which employ algorithms such as random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), and multilayer perceptron (MLP), outperform the VEGA models in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, and selectivity" [36].

ADMET Integration in Cancer Drug Design

ADMET Prediction Workflow

Incorporate ADMET prediction seamlessly into the 3D-QSAR workflow:

- Early-Stage Screening: Prioritize compounds with favorable predicted ADMET profiles before synthesis [34]

- Multi-Parameter Optimization: Balance potency against ADMET properties using desirability functions or scoring algorithms

- Hit-to-Lead Expansion: Guide structural modifications to improve problematic ADMET characteristics while maintaining efficacy

Key ADMET Endpoints for Cancer Drugs

Focus computational ADMET prediction on endpoints most relevant to oncology candidates:

- Metabolic Stability (human liver microsomal clearance) [11]

- Membrane Permeability (Caco-2/MDR1-MDCKII models) [11]

- Solubility (critical for formulation and bioavailability) [11]

- hERG Inhibition (cardiotoxicity risk assessment)

- CYP450 Inhibition (drug-drug interaction potential) [34]

Machine learning-based ADMET prediction platforms such as ADMETlab 2.0 provide integrated solutions for these endpoints, demonstrating that "ML-based models have demonstrated significant promise in predicting key ADMET endpoints, outperforming some traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models" [34].

Experimental Protocol: 3D-QSAR Model Development

Required Materials and Software

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | Schrodinger Suite, Sybyl-X, ChemDraw | Compound building, optimization, conformational analysis [35] [38] |

| 3D-QSAR Software | Open3DALIGN, ROCS, Phase | Molecular alignment, field calculation, model building [35] |

| Machine Learning | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, Keras | Implementation of RF, SVM, MLP algorithms [36] [39] |

| ADMET Platforms | ADMETlab 2.0, pkCSM, PreADMET | Prediction of pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties [34] |

| Validation Tools | KNIME, Python/R scripts | Statistical validation, applicability domain assessment |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Phase I: Data Preparation (1-2 Days)

- Curate dataset of 30-50 compounds with consistent biological activity data [38]

- Convert activity values to pIC₅₀ or pKᵢ using the formula: pIC₅₀ = -log₁₀(IC₅₀) [38]

- Divide dataset using activity-stratified partitioning into:

- Training set (70-80% for model building)

- Test set (20-30% for external validation) [40]

- Generate 3D structures and optimize geometry using molecular mechanics force fields [35]

- Perform molecular alignment using a common substructure or pharmacophore hypothesis [38]

Phase II: Model Construction (2-3 Days)

- Calculate interaction fields using CoMFA/CoMSIA approaches with default grid spacing (2Å)

- Extract 3D molecular descriptors for machine learning-enhanced models [36]

- Apply partial least-squares (PLS) analysis with leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation for traditional 3D-QSAR [35]

- Train machine learning models using training set compounds and descriptors

- Optimize model parameters through grid search or genetic algorithms

Phase III: Validation and Application (1-2 Days)

- Assess internal validation through q² and other statistical parameters [35]

- Evaluate external predictivity using the test set compounds

- Define applicability domain to identify compounds within model scope [39]

- Deploy model for virtual screening of novel compounds

- Integrate ADMET predictions for comprehensive candidate prioritization [34]

Advanced Applications in Cancer Drug Discovery

Federated Learning for Enhanced ADMET Prediction

Recent advances in federated learning address the critical challenge of data diversity in ADMET prediction:

- Cross-organization collaboration: Train models on distributed proprietary datasets without data sharing [11]

- Expanded applicability domain: Improved prediction for novel scaffolds and chemical space [11]

- Heterogeneous data integration: Superior models even with varied assay protocols and compound libraries [11]

Studies demonstrate that "federated models systematically outperform local baselines, and performance improvements scale with the number and diversity of participants" [11], making this approach particularly valuable for predicting ADMET properties of novel anticancer scaffolds.

Case Study: Anticancer Drug Discovery Pipeline

A recent integrative computational strategy for breast cancer drug discovery exemplifies the power of combining 3D-QSAR with ADMET prediction:

- Initial 3D-QSAR and ANN modeling identified 12 novel drug candidates (L1-L12) targeting aromatase [23]

- Virtual screening techniques prioritized one hit (L5) showing significant potential compared to reference drug exemestane [23]

- Subsequent stability studies and pharmacokinetic evaluations reinforced L5 as an effective aromatase inhibitor [23]

- Retrosynthetic analysis proposed feasible synthesis routes for the prioritized candidate [23]

This case highlights how 3D-QSAR serves as the foundational element in a comprehensive computer-aided drug design pipeline, efficiently funneling candidates from virtual screening to experimental validation.

Robust 3D-QSAR modeling, strategically integrated with ADMET prediction, represents a transformative approach in cancer drug discovery. By following the detailed protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can develop predictive models that not only elucidate critical structure-activity relationships but also simultaneously address the pharmacokinetic and safety considerations that ultimately determine clinical success. The continued evolution of these computational methods—particularly through machine learning enhancement and federated learning approaches—promises to further accelerate the identification of viable anticancer candidates with optimal efficacy and safety profiles.

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women globally, with over 2.3 million new cases diagnosed annually [8]. The development of more effective therapeutic agents with minimal side effects represents a critical challenge in oncology drug discovery. Tubulin, a pivotal protein in cancer cell division, has emerged as a promising molecular target for anticancer therapy [8] [41]. Specifically, inhibitors targeting the colchicine binding site (CBS) of tubulin disrupt microtubule dynamics, thereby inhibiting mitosis and cell proliferation [41].

The 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one scaffold has recently gained significant attention as a privileged structure for designing novel tubulin inhibitors [8] [41]. These derivatives serve as cisoid restricted combretastatin A4 analogues, where the 1,2,4-triazin-3(2H)-one ring replaces the olefinic bond while maintaining essential pharmacophoric features of colchicine binding site inhibitors [41]. This case study explores the integration of 3D-QSAR modeling and ADMET profiling within a comprehensive computational framework to design and optimize 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives as potent tubulin inhibitors for breast cancer therapy, contextualized within a broader thesis on ADMET property prediction in 3D-QSAR cancer drug design research.

Computational Workflow and Methodologies

Integrated Computational Workflow

The drug discovery process for triazine-based tubulin inhibitors employs a multi-stage computational approach that systematically integrates molecular modeling, predictive analytics, and simulation techniques. The workflow progresses from initial compound design through to the identification of optimized lead candidates, with ADMET considerations embedded throughout the process.

Dataset Curation and Chemical Space Analysis

The foundation of robust QSAR modeling relies on comprehensive dataset curation. Studies have utilized datasets of 32-35 novel 1,2,4-triazin-3(2H)-one derivatives with experimentally determined inhibitory efficacy against breast cancer cell lines (typically MCF-7) [8] [41]. The biological activity values (IC50) are converted to pIC50 (-log IC50) to ensure normal distribution for modeling purposes. The dataset is typically divided using an 80:20 ratio, where 80% of compounds form the training set for model development and 20% constitute the test set for external validation [8]. This division strategy balances comprehensive model training with adequate external validation capability.

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection

Molecular descriptors quantitatively characterize structural features influencing biological activity. Calculations encompass two primary descriptor categories:

Electronic Descriptors: Computed using quantum mechanical methods (Gaussian 09W) with Density Functional Theory (DFT) at B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level [8]. Key descriptors include:

- Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital Energy (EHOMO)

- Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital Energy (ELUMO)

- Dipole Moment (μm)

- Absolute Electronegativity (χ)

- Absolute Hardness (η)

Topological Descriptors: Calculated using ChemOffice software [8]:

- Molecular Weight (MW)

- Octanol-Water Partition Coefficient (LogP)

- Water Solubility (LogS)

- Polar Surface Area (PSA)

- Hydrogen Bond Donors/Acceptors (HBD/HBA)

- Number of Rotatable Bonds (NROT)

Descriptor selection employs statistical analysis (Variance Inflation Factor) combined with biological reasoning to eliminate multicollinearity and retain chemically meaningful parameters [8].

3D-QSAR Model Development

Three-dimensional QSAR approaches, particularly Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), establish correlations between molecular fields and biological activity. The methodology includes:

Molecular Alignment: Structures are sketched (SYBYL 2.0), energy-minimized (Tripos force field), and aligned using the distill alignment technique with the most active compound as template [42].

Field Calculation: CoMSIA computes steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor descriptors using a charged sp³ carbon probe atom on a 3D grid (2Å spacing) [42] [43].

Model Construction: Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression correlates CoMSIA descriptors with pIC50 values. Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation determines the optimal number of components (N) and cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) [42] [43].

ADMET Profiling Protocol

ADMET properties are predicted using computational tools (e.g., SwissADME) to evaluate drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic profiles [44]. Key parameters include:

- Absorption: Caco-2 permeability, HIA (Human Intestinal Absorption)

- Distribution: Plasma Protein Binding, Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration

- Metabolism: CYP450 Enzyme Inhibition

- Excretion: Total Clearance

- Toxicity: hERG Inhibition, Ames Mutagenicity, Hepatotoxicity

Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulations

Molecular Docking: Performed using AutoDock Vina or similar tools to predict binding modes and affinities at the tubulin colchicine binding site [8] [44]. The protocol includes protein preparation (removal of co-crystallized ligands, addition of hydrogens), ligand preparation (energy minimization), grid box definition, and docking simulation.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Conducted using GROMACS or AMBER for 100ns to evaluate complex stability [8] [44]. Analysis includes:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD)

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF)

- Radius of Gyration (Rg)

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA)

- Hydrogen bond analysis

Results and Discussion

3D-QSAR Model Performance and Validation

The developed 3D-QSAR models demonstrated excellent predictive capability for tubulin inhibitory activity. Statistical validation metrics confirm model robustness and reliability for prospective compound design.

Table 1: Validation Metrics for 3D-QSAR Models of Triazine Derivatives

| Validation Parameter | Reported Value | Statistical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| R² (Determination Coefficient) | 0.849-0.967 [8] [42] | High explained variance in biological activity |

| Q² (LOO Cross-Validation) | 0.717-0.814 [42] [43] | Excellent internal predictive capability |

| R²Pred (External Validation) | 0.722-0.832 [42] [43] | Strong predictive power for new compounds |

| Standard Error of Estimation | Not specified | Measure of model precision |

| Optimal Components (N) | Dataset-dependent [42] | Prevents model overfitting |

The high R² values (0.849-0.967) indicate that the models explain approximately 85-97% of the variance in tubulin inhibitory activity [8] [42]. The Q² values exceeding 0.7 demonstrate robust internal predictive capability, while R²Pred values above 0.72 confirm excellent external predictability for novel compounds [42] [43].

Key Molecular Descriptors and Structural Insights

Contour map analysis from CoMSIA models reveals critical structural requirements for tubulin inhibition:

Steric Fields: Bulky substituents at the C5 position of triazine ring enhance activity, particularly 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl groups that occupy a deep hydrophobic pocket in the tubulin binding site [41].

Electrostatic Fields: Positive regions near methoxy groups indicate favorable interactions with electron-rich protein residues, while negative regions near the triazine carbonyl group suggest favorable interactions with hydrogen bond donors in the binding site [41].

Hydrophobic Fields: Hydrophobic substituents on both phenyl rings (particularly 3,4,5-trimethoxy pattern) significantly enhance activity through interactions with non-polar residues (Leu242, Leu255, Val318) in the colchicine binding site [41].

Hydrogen-Bonding Fields: The triazine-3(2H)-one carbonyl serves as critical hydrogen bond acceptor, while the NH group can function as hydrogen bond donor, mimicking interactions of native colchicine with tubulin [41].

ADMET Profiling of Triazine Derivatives