How Computer-Aided Drug Design is Accelerating the Anticancer Drug Discovery Timeline

This article explores the transformative role of Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) in expediting the development of novel anticancer therapies.

How Computer-Aided Drug Design is Accelerating the Anticancer Drug Discovery Timeline

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) in expediting the development of novel anticancer therapies. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how CADD methodologies—from virtual screening and AI-powered predictions to molecular dynamics—are fundamentally reshaping a traditionally lengthy and costly process. The content covers foundational principles, key computational techniques, strategies for overcoming implementation challenges, and real-world validation through case studies and clinical trial outcomes, ultimately framing CADD as an indispensable tool for improving efficiency and success rates in oncology drug discovery.

The Pressing Need and Foundational Shift: Why CADD is Revolutionizing Anticancer Drug Discovery

The Global Cancer Burden and the Imperative for Accelerated Discovery

Cancer presents a critical and growing global health crisis. According to the World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), an estimated 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million deaths occurred in 2022, with approximately 53.5 million people alive within 5 years of a cancer diagnosis [1]. The lifetime risk of developing cancer is approximately 1 in 5 people, with about 1 in 9 men and 1 in 12 women dying from the disease [1]. Looking ahead, the burden is projected to increase dramatically, with over 35 million new cancer cases predicted in 2050, representing a 77% increase from 2022 estimates [1]. This escalating burden, coupled with the inadequacies of present-day therapies and the emergence of drug-resistant cancer strains, has created an urgent need for more efficient drug discovery paradigms [2].

Table 1: Global Cancer Burden: Key Statistics (2022)

| Metric | Figure | Context |

|---|---|---|

| New Cases | 20 million | Estimated global incidence [1] |

| Deaths | 9.7 million | Estimated global mortality [1] |

| 5-Year Prevalence | 53.5 million | People alive post-diagnosis [1] |

| Lifetime Risk (Incidence) | ~1 in 5 | Global average [1] |

| Projected 2050 Cases | 35+ million | 77% increase from 2022 [1] |

This landscape creates an undeniable imperative to accelerate anticancer drug discovery. Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) emerges as a transformative force in this endeavor, bridging the realms of biology and technology to rationalize and expedite the discovery process [3]. By utilizing computational algorithms on chemical and biological data to simulate and predict how drug molecules interact with their biological targets, CADD significantly truncates the traditional drug discovery timeline and offers a powerful response to the global cancer challenge [3] [4].

The Quantitative Burden: Key Epidemiological Data

Leading Cancers and Mortality

The global cancer burden is not uniformly distributed across cancer types. Data from IARC's Global Cancer Observatory, covering 185 countries and 36 cancer types, reveals that ten types of cancer collectively comprise around two-thirds of new cases and deaths globally [1]. The most common cancer types in 2022 are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Most Common Cancers and Deaths Worldwide (2022)

| Rank | Cancer Type (Incidence) | New Cases | % of Total | Cancer Type (Mortality) | Deaths | % of Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lung | 2.5 million | 12.4% | Lung | 1.8 million | 18.7% |

| 2 | Female Breast | 2.3 million | 11.6% | Colorectal | 900,000 | 9.3% |

| 3 | Colorectal | 1.9 million | 9.6% | Liver | 760,000 | 7.8% |

| 4 | Prostate | 1.5 million | 7.3% | Female Breast | 670,000 | 6.9% |

| 5 | Stomach | 970,000 | 4.9% | Stomach | 660,000 | 6.8% |

The re-emergence of lung cancer as the most common cancer is likely related to persistent tobacco use in Asia [1]. Significant differences in incidence and mortality exist between sexes. For women, breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and leading cause of cancer death, whereas for men, it is lung cancer [1].

Disparities and Projected Growth

Striking inequities in the cancer burden are evident when analyzed by the Human Development Index (HDI). For example, in countries with a very high HDI, 1 in 12 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime and 1 in 71 women die of it. By contrast, in countries with a low HDI, while only 1 in 27 women is diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime, 1 in 48 women will die from it [1]. This highlights that women in lower HDI countries are 50% less likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer than women in high HDI countries, yet they are at a much higher risk of dying of the disease due to late diagnosis and inadequate access to quality treatment [1].

The projected growth in cancer cases to 2050 will also not be felt evenly across countries. While high HDI countries are expected to experience the greatest absolute increase in incidence (an additional 4.8 million new cases), the proportional increase is most striking in low HDI countries (142% increase) and medium HDI countries (99%) [1]. Likewise, cancer mortality in these countries is projected to almost double in 2050 [1]. In the United States, for 2025, the American Cancer Society projects 2,041,910 new cancer cases and 618,120 cancer deaths [5]. These disparities and projections underscore the urgent need for more efficient and accessible therapeutic solutions.

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, transitioning the process from being largely empirical to becoming more rational and targeted [3]. CADD utilizes computer algorithms on chemical and biological data to simulate and predict how a drug molecule will interact with its target—usually a protein or DNA sequence in the biological system [3]. This can range from understanding the drug’s molecular structure to forecasting pharmacological effects and potential side effects. The core of CADD is subdivided into two main categories: structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD) [3].

Key Techniques and Methodologies in CADD

The effectiveness of CADD arises from a plethora of sophisticated computational techniques and methodologies that work in concert to identify and optimize potential drug candidates [3].

Molecular Modeling and Dynamics: At the heart of CADD lies molecular modeling, which encompasses techniques used to model the behavior of molecules, often creating three-dimensional models of proteins and ligands [3]. Methods like molecular dynamics (MD) simulations forecast the time-dependent behavior of molecules, capturing their motions and interactions over time using tools like GROMACS, ACEMD, and OpenMM [3]. Recently developed AI/ML-driven tools like AlphaFold2, trRosetta, Robetta, and ESMFold have dramatically accelerated the accuracy and speed of protein structure prediction, which is foundational for SBDD [3].

Molecular Docking and Virtual Screening: Docking involves predicting the orientation, position, and binding affinity of a drug molecule when it binds to its target protein [3]. This is achieved with advanced tools such as AutoDock Vina, AutoDock GOLD, Glide, and SwissDock [3]. Virtual screening, a complementary approach, involves sifting through vast compound libraries to identify potential drug candidates that are likely to bind to a specific drug target, using tools like DOCK and ChemBioServer [3].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): QSAR modeling explores the relationship between the chemical structure of molecules and their biological activities [3]. Through statistical methods, QSAR models can predict the pharmacological activity of new compounds based on their structural attributes, enabling chemists to make informed modifications to enhance a drug’s potency or reduce its side effects [3].

Table 3: Key CADD Techniques and Representative Software Tools

| Technique | Description | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Predicts ligand orientation & binding affinity at target site. | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide, SwissDock [3] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Simulates time-dependent behavior of molecular systems. | GROMACS, NAMD, CHARMM, ACEMD, OpenMM [3] |

| Virtual Screening | Rapidly evaluates large compound libraries for hits. | DOCK, LigandFit, ChemBioServer [3] |

| QSAR | Relates chemical structure to biological activity statistically. | Various statistical and machine learning models [3] |

| Structure Prediction | Predicts 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences. | AlphaFold2, trRosetta, ESMFold, I-TASSER [3] |

CADD in Action: Targeting VEGFR-2 in Cancer

The process of designing a novel VEGFR-2 inhibitor exemplifies the power and precision of the CADD pipeline. VEGFR-2 is a significant target in cancer treatment, as its inhibition disrupts angiogenesis, impeding tumor growth and survival [6]. The rationale for targeting VEGFR-2 is strong, as its over-expression is linked to greater resistance to cancer medications, increased angiogenesis, and reduced apoptosis [6].

Experimental Protocol for VEGFR-2 Inhibitor Development

The development of a novel theobromine derivative (T-1-MBHEPA) as a VEGFR-2 inhibitor showcases a complete CADD workflow, from in silico design to in vitro and in vivo validation [6].

Rational Structure-Based Design: The ATP binding pocket of VEGFR-2 comprises four distinct regions crucial for ligand binding: the hinge region, the gatekeeper region, the DFG motif region, and the allosteric pocket [6]. The T-1-MBHEPA molecule was designed with specific moieties to target each region: a xanthine moiety for the hinge region, an N-phenylacetamide moiety for the gatekeeper region, a formyl hydrazone group for the DFG motif, and a 3-methylphenyl moiety as a hydrophobic tail for the allosteric pocket [6].

Computational Stability and Reactivity Assessment: Density Functional Theory (DFT) computations were first performed to indicate T-1-MBHEPA's stability and reactivity [6].

Molecular Docking Studies: The evaluation of T-1-MBHEPA against VEGFR-2 was conducted using MOE 2019 software to predict its binding orientation and affinity within the ATP binding pocket [6].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Binding Free Energy Calculations: The stability of the VEGFR-2_T-1-MBHEPA complex was evaluated by running a 100-ns classical unbiased MD simulation in GROMACS. This was complemented by Molecular Mechanics-Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) calculations to estimate the binding free energy, and Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP) analysis to characterize specific interaction types [6].

ADMET Profiling: The Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) profiles of T-1-MBHEPA were studied in silico to predict its drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic properties before any semi-synthesis [6].

Experimental Validation:

- In vitro Biochemical Assay: T-1-MBHEPA inhibited VEGFR-2 with an IC₅₀ value of 0.121 ± 0.051 µM, comparing favorably to the reference drug sorafenib (IC₅₀ = 0.056 µM) [6].

- In vitro Anti-proliferative Activity: The compound inhibited the proliferation of HepG2 (liver) and MCF7 (breast) cancer cell lines with IC₅₀ values of 4.61 and 4.85 µg/mL, respectively [6].

- Apoptosis Assay: T-1-MBHEPA significantly increased the percentage of apoptotic MCF7 cells, with early apoptosis rising from 0.71% to 7.22% and late apoptosis from 0.13% to 2.72% [6].

- In vivo Toxicity Assessment: Oral treatment with T-1-MBHEPA did not show toxicity on the liver function (ALT and AST) and kidney function (creatinine and urea) levels in mice, indicating a promising initial safety profile [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CADD-Driven Discovery

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| VEGFR-2 Protein | The purified target protein for biochemical inhibition assays (IC₅₀ determination) [6]. |

| Human Cancer Cell Lines (e.g., MCF7, HepG2) | In vitro models for evaluating anti-proliferative activity and selectivity [6]. |

| Sorafenib | Reference control compound (standard VEGFR-2 inhibitor) for benchmarking new candidates [6]. |

| Annexin V / Propidium Iodide (PI) | Fluorescent dyes used in flow cytometry to distinguish early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells [6]. |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) Software | Integrated software suite for molecular modeling, docking, and simulation [6]. |

| GROMACS Package | Open-source software for performing molecular dynamics simulations [6]. |

| Cell Viability Assay Kits (e.g., MTT/MTS) | Colorimetric assays to quantify cell proliferation and determine IC₅₀ values [6]. |

The success of CADD is heavily dependent on access to high-quality, well-annotated data. Several major initiatives provide open and controlled-access data that are indispensable for computational drug discovery. The following diagram and table summarize key resources available from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Data Catalog and other consortia.

Table 5: Essential Data Resources for CADD in Cancer Research

| Resource Name | Data Type | Key Description |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Data Commons (GDC) [7] | Genomics | A unified data repository enabling data sharing across cancer genomic studies in support of precision medicine. |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [7] | Genomics | A comprehensive effort to accelerate the understanding of the molecular basis of cancer through genome analysis technologies for over 30 cancer types. |

| Cancer Genome Characterization Initiative (CGCI) [7] | Genomics | Applies advanced sequencing to identify novel genetic abnormalities in both adult and pediatric cancers. |

| Imaging Data Commons (IDC) [7] | Imaging | A cloud-based repository of cancer imaging data, image annotations, and analysis results. |

| Clinical & Translational Data Commons (CTDC) [7] | Clinical | Provides access to clinical and translational data from NCI-funded clinical trials and correlative studies. |

| NCI-60 Human Tumor Cell Lines [7] | Drug Discovery | A panel of 60 diverse human cancer cell lines used to screen over 100,000 chemical compounds and natural products. |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) [7] | Epidemiology | Collects and publishes cancer incidence and survival data from population-based cancer registries covering ~50% of the U.S. population. |

The global cancer burden is immense, growing, and marked by significant inequities. The projected rise to over 35 million new cases annually by 2050 underscores a critical and urgent need for accelerated therapeutic discovery [1]. Computer-Aided Drug Design stands as a pivotal and transformative response to this imperative. By leveraging computational power, advanced algorithms, and vast biological datasets, CADD rationalizes and expedites the drug discovery pipeline, as demonstrated by the successful development of targeted agents like VEGFR-2 inhibitors [6] [4]. The continued integration of CADD with emerging technologies—such as more sophisticated AI and machine learning, quantum computing for complex simulations, and immersive technologies for molecular visualization—promises to further redefine the future of anticancer drug discovery [3]. To overcome the challenges ahead, sustained investment in computational methods, robust data sharing platforms, and a commitment to training the next generation of computational biologists will be essential. By embracing these advanced tools and collaborative approaches, the scientific community can translate the imperative for accelerated discovery into tangible improvements in cancer care and patient survival worldwide.

The journey of bringing a new drug from concept to clinic is a notoriously arduous, expensive, and inefficient process, characterized by a high failure rate. This bottleneck is particularly pronounced in oncology, where the complex biology of cancer introduces additional layers of challenge. Current statistics paint a stark picture: the average development time for a new drug is 10–15 years, with costs estimated at approximately $2.6 billion [8]. The overall success rate for new drug entities reaching the market is less than 10% [9] [8]. In the specific field of oncology, this rate is even more dismal, with an estimated 97% of new cancer drugs failing in clinical trials. This translates to a mere 1 in 20,000–30,000 drugs progressing from initial development to marketing approval [9].

The high attrition rate is primarily due to insufficient efficacy and safety concerns identified during clinical phases [8]. Furthermore, cancer is a complex disease involving interconnected biological pathways that are difficult to target effectively with classical methods. Many potential targets, such as transcription factors or proteins involved in large protein-protein interactions, are often classified as "undruggable" because they lack well-defined binding sites for small molecules [8]. These factors collectively contribute to a model that is unsustainable, demanding innovative approaches to reduce costs, accelerate timelines, and improve success probabilities.

Quantitative Analysis of the Drug Discovery Bottleneck

The following tables summarize the key quantitative challenges that define the traditional drug discovery paradigm, providing a clear picture of the inefficiencies that Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) aims to address.

Table 1: Overall Drug Discovery and Development Metrics

| Metric | Value | Context & Source |

|---|---|---|

| Average Timeline | 10-15 years | From initial discovery to regulatory approval [8]. |

| Total Cost | ~$2.6 billion | Includes both direct and indirect costs [8]. |

| Overall Success Rate | <10% | Less than 10% of drug candidates entering clinical trials reach the market [9] [8]. |

| Clinical Trial Phase | ~14.6 years | The traditional path to a new drug [10]. |

Table 2: Oncology-Specific Challenges and Failure Rates

| Metric | Value | Context & Source |

|---|---|---|

| Oncology Drug Failure Rate | 97% | The vast majority of new cancer drugs fail during clinical trials [9]. |

| Attrition Rate | 1 in 20,000-30,000 | The number of drugs that progress from initial development to marketing approval [9]. |

| Major Cause of Failure | Insufficient Efficacy & Safety | The primary reasons for drug development failure are lack of desired therapeutic effect and toxicity [8]. |

The Classical Modalities and Their Limitations

The traditional drug discovery pipeline is a multi-stage process that, while yielding life-saving treatments, is inherently riddled with inefficiencies.

Target Identification and Validation

The process often begins with the identification of a therapeutic target, such as a protein with a key role in cancer progression. Whole genomic analysis reinforced with functional studies like gene knockout and high-throughput screening (HTS) using CRISPR-Cas9 have been instrumental in finding novel oncogenic vulnerabilities [8]. However, not all identified proteins are "druggable." A protein must exhibit a well-defined binding pocket where a small molecule can bind with high affinity and specificity. Many promising targets, especially those involved in protein-protein interactions, lack these characteristics, making them intractable with conventional approaches [8].

Hit Identification and Lead Optimization

Once a target is validated, the search for a chemical "hit" begins. This typically relies on high-throughput screening (HTS) of large libraries of chemical compounds against the target [8]. This process is expensive, time-consuming, and often yields hits with poor pharmacokinetic properties. The subsequent lead optimization phase involves chemically modifying these hits to enhance properties like potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetics while minimizing toxicity [8]. This stage involves a slow, iterative cycle of synthesis and testing, heavily reliant on medicinal chemistry intuition and often taking several years.

Preclinical and Early Clinical Development

Successful lead candidates then proceed to preclinical research, where their safety and efficacy are tested in cell-based and animal models. Candidates that pass this stage are filed as an Investigational New Drug Application (IND) before entering clinical trials [9] [11]. Phase I trials in oncology primarily focus on safety and identifying the maximum tolerated dose (MTD), often using classical designs like the "3 + 3" escalation design [8]. These designs are time-consuming, do not adequately account for patient heterogeneity, and can expose patients to subtherapeutic doses for extended periods, providing limited data for subsequent trial phases [8].

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) as a Strategic Response

CADD represents a paradigm shift, leveraging computational power and theoretical chemistry to navigate the drug discovery bottleneck more intelligently and efficiently. CADD uses computational methods to simulate the structure, function, and interactions of target molecules with ligands to screen, design, and optimize potential drug compounds [12]. The primary goal is to reduce the number of experimental candidates, thereby slashing research costs and development cycles while improving the precision of hit identification [12].

CADD encompasses two primary approaches:

- Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD): Leverages the three-dimensional structural information of a macromolecular target (e.g., a protein) to identify key binding sites and design drugs that can interact with them [12]. Techniques include molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and free-energy calculations.

- Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD): Used when the 3D structure of the target is unknown. It studies the structure-activity relationships (SARs) of known ligands to guide drug optimization and novel drug design. Key methods include quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and pharmacophore modeling [12].

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) has given rise to AI-driven drug discovery (AIDD), an advanced subset of CADD that uses algorithms to learn from large datasets, identify patterns, and make predictions with unprecedented speed and accuracy [9] [12].

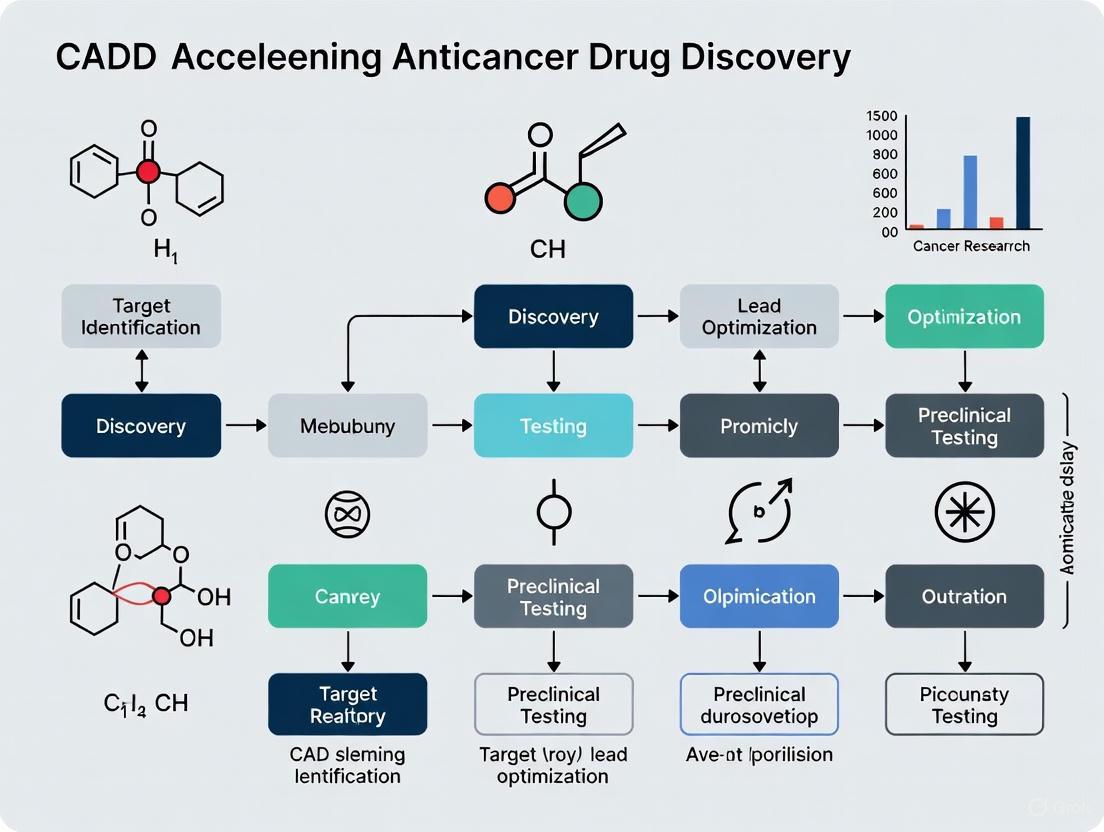

Diagram 1: Traditional vs. CADD-Accelerated Workflow. This diagram contrasts the high-attrition traditional drug discovery process with the more efficient, computationally-guided CADD pathway.

Detailed CADD Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

AI-Enhanced Target Identification and Validation

Objective: To identify and prioritize novel, druggable oncology targets from complex biological data. Methodology:

- Multiomics Data Analysis: AI models, particularly deep learning networks, are trained on vast datasets from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to uncover hidden patterns and novel oncogenic vulnerabilities [8].

- Network-Based Approaches: AI algorithms analyze biological networks to identify key nodes (proteins/genes) whose disruption would most significantly impact cancer cell survival [8].

- Druggability Assessment: Tools like AlphaFold, which predicts protein 3D structures with high accuracy from amino acid sequences, are used to assess whether a target has a well-defined binding pocket suitable for drug binding [8] [12].

Structure-Based Virtual Screening and Lead Optimization

Objective: To rapidly identify and optimize lead compounds that bind strongly and specifically to the target. Methodology:

- Molecular Docking:

- Protein Preparation: The 3D structure of the target protein (from X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, or AlphaFold prediction) is prepared by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and defining the binding site.

- Ligand Library Preparation: A virtual library of millions of compounds is prepared, generating plausible 3D conformations for each.

- Docking Simulation: Each compound is computationally "docked" into the binding site, sampling multiple orientations and conformations.

- Scoring: A scoring function ranks the compounds based on their predicted binding affinity [12].

- Fragment-Based Screening (e.g., SILCS Method):

- FragMap Generation: The target protein is surrounded by small molecular fragments (e.g., benzene, propane) in a computer simulation.

- Mapping: Software maps how these fragments cling to the protein's surface, revealing hot spots for different chemical interactions.

- Lead Assembly: The FragMaps are used to screen millions of compounds or to rationally design larger molecules by linking fragments that bind to adjacent hot spots [13]. This method provides a more efficient starting point than HTS.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Modern CADD

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function in CADD |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold | Software/AI Model | Predicts the 3D structure of proteins with high accuracy, aiding in druggability assessment and SBDD when experimental structures are unavailable [8] [12]. |

| SILCS (Site Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation) | Software Suite/Platform | Generates fragment-based binding maps (FragMaps) of target proteins to guide the design and optimization of lead compounds with high binding affinity [13]. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock, Glide) | Software | Automates the process of predicting how a small molecule (ligand) binds to a protein target and scores its binding affinity [12]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD) | Software | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing insights into the stability of drug-target complexes and binding kinetics [12]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Hardware | Provides the vast computational power (CPUs/GPUs) required for running complex simulations, virtual screens, and AI model training [13]. |

AI-Driven De Novo Drug Design and ADMET Prediction

Objective: To generate novel, drug-like molecules from scratch and predict their pharmacokinetic and toxicological properties early in the process. Methodology:

- Generative AI Models: Techniques like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) are used to explore vast chemical spaces and generate novel molecular structures that satisfy desired properties (e.g., potency, solubility) [12] [14].

- ADMET Prediction: AI/ML models are trained on large chemical and biological datasets to predict Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET). This allows for the early elimination of compounds with poor pharmacokinetic or safety profiles, a major cause of late-stage failure [9] [15].

Impact and Outcomes: CADD in Action

The implementation of CADD and AI is demonstrating tangible benefits in reducing the drug discovery bottleneck. AI-enabled workflows are projected to save up to 40% of time and 30% of costs in the discovery phase for complex targets [10]. By some estimates, 30% of new drugs could be discovered using AI by 2025 [10].

A compelling case study comes from the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy's CADD Center. Their collaboration with biochemist Paul Shapiro led to the development of a drug for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), dubbed GEN-1124. Using CADD methodologies, the project took just five years to advance from a weak starting compound to an investigational drug in humans, compared to the typical 10 to 15 years [13].

Furthermore, AI-driven platforms like Insilico Medicine's have shown the ability to reduce discovery timelines even more dramatically, taking a molecule from target identification to candidate in a few months, and into clinical trials in approximately one year [10]. These examples underscore CADD's potential to not only cut costs but also to deliver life-saving therapies to patients much faster.

Diagram 2: CADD Impact on Key Metrics. This diagram visualizes the positive impact of CADD on the primary challenges of traditional drug discovery: time, attrition, and cost.

The traditional drug discovery pipeline, plagued by excessive costs, protracted timelines, and unacceptable failure rates, represents a significant bottleneck in delivering new cancer therapies to patients. The statistics are clear: a process taking over a decade, costing billions, and failing more than 90% of the time is unsustainable. Computer-Aided Drug Design, supercharged by artificial intelligence and machine learning, is emerging as a transformative solution to this challenge. By enabling smarter target identification, rapid virtual screening, de novo molecular design, and early prediction of compound failure, CADD introduces a new era of data-driven efficiency. As these computational methodologies continue to evolve and integrate into the pharmaceutical R&D landscape, they hold the definitive promise of breaking the traditional bottleneck, accelerating the discovery of innovative anticancer drugs, and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Defining Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) and its Core Principles

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) represents a transformative force in modern therapeutics, defined as the use of computational techniques and software tools to discover, design, and optimize new drug candidates [16]. This interdisciplinary field integrates bioinformatics, cheminformatics, molecular modeling, and simulation to accelerate drug discovery processes, reduce costs, and improve the success rates of new therapeutics [16]. The core principle underpinning CADD is the utilization of computer algorithms on chemical and biological data to simulate and predict how a drug molecule will interact with its biological target—typically a protein or nucleic acid [3].

The emergence of CADD marks a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical research, transitioning drug discovery from largely empirical, trial-and-error methodologies to a more rational and targeted process [3]. This shift is particularly crucial in anticancer drug discovery, where the complexity of cancer biology demands highly specific therapeutic interventions. By enabling researchers to predict drug-target interactions, binding affinities, and pharmacological properties in silico before synthesis and clinical testing, CADD provides a powerful framework for addressing the high failure rates and escalating costs associated with conventional drug development [16].

Core Principles and Methodological Framework of CADD

CADD methodologies are broadly categorized into two complementary approaches: structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD). The selection between these approaches depends primarily on the availability of structural information for the biological target or known active compounds.

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)

SBDD leverages knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of the biological target, obtained through experimental methods like X-ray crystallography or Cryo-EM, or via computational predictions [3]. The central premise is that a drug's biological activity stems from its molecular recognition and binding complementarity with the target structure. With the increasing availability of protein structures and advancements in proteomics, SBDD has become the dominant CADD approach, holding approximately 55% of the market share in 2024 [16]. This dominance reflects its critical role in developing drugs with greater specificity and selectivity, particularly in oncology where targeting specific oncogenic drivers is essential.

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD)

When the three-dimensional structure of the biological target is unavailable, LBDD offers an alternative strategy. Instead of relying on target structure, LBDD focuses on known active compounds (ligands) and their pharmacological profiles to design new drug candidates [3]. By analyzing the structural and physicochemical properties of active molecules, LBDD establishes quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models that predict the biological activity of novel compounds [3]. The availability of large ligand databases and the cost-effectiveness of not requiring complex structural determination software make LBDD a rapidly growing segment, expected to achieve the highest compound annual growth rate in the CADD market [16].

The following workflow illustrates how these core principles integrate into a comprehensive CADD pipeline for anticancer drug discovery:

Key Computational Techniques in CADD

Molecular Modeling and Dynamics

At the heart of CADD lies molecular modeling, which encompasses computational techniques to model the behavior of molecules, particularly proteins and ligands [3]. This involves creating three-dimensional models of molecular structures to provide insights into their structural and functional attributes. Recent AI/ML-driven tools like AlphaFold2, trRosetta, Robetta, and ESMFold have dramatically accelerated protein structure prediction [3]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations extend these capabilities by forecasting the time-dependent behavior of molecules, capturing their motions and interactions over time using tools like GROMACS, ACEMD, and OpenMM [3].

Docking and Virtual Screening

Molecular docking involves predicting the preferred orientation and position of a drug molecule when bound to its target protein, estimating the binding affinity crucial for drug design [3]. Virtual screening complements docking by computationally sifting through vast compound libraries to identify potential drug candidates [3]. These techniques employ specialized tools with distinct advantages:

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Docking and Virtual Screening

| Tool | Application | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Predicting binding affinities and orientations | Fast, accurate, easy to use | Less accurate for complex systems [3] |

| AutoDock GOLD | Predicting binding, especially for flexible ligands | Accurate for flexible ligands | Requires license, can be expensive [3] |

| Glide | Predicting binding affinities and orientations | Accurate, integrated with Schrödinger tools | Requires Schrödinger suite (expensive) [3] |

| SwissDock | Predicting binding affinities and orientations | Easy to use, accessible online | Less accurate for complex systems [3] |

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR)

QSAR modeling explores the relationship between chemical structures and biological activities using statistical methods [3]. These models predict pharmacological activity of new compounds based on structural attributes, enabling informed modifications to enhance drug potency or reduce side effects. In anticancer applications, researchers have used similarity ensemble approaches and k-nearest neighbors QSAR models to identify active molecules targeting specific oncoproteins [3].

CADD's Role in Accelerating Anticancer Drug Discovery

Addressing the Oncology Discovery Challenge

The conventional drug discovery process typically consumes 12-15 years and costs approximately $2.6 billion, with a disheartening 90% failure rate in clinical trials and only about 10% probability of success for candidates entering trials [16] [17]. In oncology specifically, the rising prevalence of cancer and demand for novel therapies has positioned cancer research as the dominant application segment for CADD, holding approximately 35% of the market share in 2024 [16].

CADD addresses these challenges through multiple acceleration mechanisms:

- Hit Identification: Virtual screening of millions of compounds against cancer targets in days versus years for experimental high-throughput screening [3] [16]

- Lead Optimization: Predicting ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties computationally before synthesis [16]

- Target Validation: Assessing the "druggability" of newly identified cancer targets through computational analysis [18]

Quantitative Impact on Discovery Timelines

The integration of CADD, particularly with AI/ML enhancements, has demonstrated dramatic reductions in discovery timelines. A Deloitte 2024 survey found that 62% of biopharma executives believe AI could cut early discovery timelines by at least 25% [17]. Remarkably, AI-designed molecules have entered Phase I trials within just 12 months of program initiation—a dramatic acceleration compared to traditional approaches [17].

Table 2: CADD Market Segmentation Highlighting Anticancer Applications (2024)

| Segment | Leading Category | Market Share | Growth Category | Projected CAGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Structure-Based Drug Design | ~55% | Ligand-Based Drug Design | Highest [16] |

| Technology | Molecular Docking | ~40% | AI/ML-Based Design | Highest [16] |

| Application | Cancer Research | ~35% | Infectious Diseases | Fastest [16] |

| End-User | Pharmaceutical & Biotech Companies | ~60% | Academic & Research Institutes | Fastest [16] |

Integrated AI Platforms: The Next Frontier

The convergence of CADD with artificial intelligence represents the most significant recent advancement in accelerating anticancer discovery. Platforms like AIDDISON exemplify this integration, combining AI/ML and CADD to generate thousands of viable molecules using similarity searches, pharmacophore screening, and generative models [17]. These systems then apply property-based filtering, molecular docking, and shape-based alignment to prioritize molecules with the highest probability of biological activity and optimal ADMET profiles [17].

The true acceleration comes from seamless integration with synthesis planning tools like SYNTHIA, which enables researchers to immediately assess synthetic accessibility of promising molecules [17]. This integration bridges the critical gap between virtual molecular design and practical laboratory synthesis, significantly reducing the iteration cycles between design and testing.

Experimental Protocols in CADD

Standard Structure-Based Drug Discovery Protocol

Objective: Identify novel inhibitors for a cancer target using structure-based approaches.

Methodology:

Target Preparation:

- Obtain 3D structure of target protein from PDB or via homology modeling using MODELLER, SWISS-MODEL, or AlphaFold2 [3]

- Add hydrogen atoms, optimize hydrogen bonding networks, and assign partial charges

- Define binding site residues based on known ligand interactions or computational prediction

Ligand Preparation:

- Curate compound library from databases (ZINC, ChEMBL, in-house collections)

- Generate 3D conformations, optimize geometry, and assign appropriate charges

- Filter for drug-likeness using Lipinski's Rule of Five and cancer-specific ADMET properties

Molecular Docking:

- Perform docking simulations using AutoDock Vina, GOLD, or Glide [3]

- Apply consensus scoring where possible to improve prediction reliability

- Cluster results based on binding poses and interaction patterns

Post-Docking Analysis:

- Visualize top-ranking poses for key interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking)

- Calculate binding energies and rank compounds for further evaluation

- Select top 50-100 candidates for in vitro testing

CADD-Guided Lead Optimization Protocol

Objective: Optimize potency and selectivity of a hit compound against a kinase target while maintaining favorable pharmacokinetics.

Methodology:

Structural Analysis:

- Identify key interactions between initial hit and target binding site

- Determine regions amenable to chemical modification using molecular dynamics simulations

Analog Design:

- Generate analog libraries using scaffold hopping and functional group replacement

- Apply QSAR models to predict potency improvements

- Use AIDDISON-like generative models to explore chemical space [17]

ADMET Prediction:

- Calculate physicochemical properties (logP, polar surface area, solubility)

- Predict metabolic stability using cytochrome P450 binding models

- Assess potential cardiotoxicity (hERG channel binding) and genotoxicity

Synthetic Feasibility Assessment:

- Evaluate synthetic accessibility using SYNTHIA retrosynthesis analysis [17]

- Prioritize compounds balancing optimal properties with synthetic tractability

Successful implementation of CADD in anticancer discovery requires access to specialized computational tools and databases. The following table catalogs essential resources:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CADD in Anticancer Discovery

| Tool/Database | Type | Function in Anticancer Discovery | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Structure Prediction | Predicts 3D structures of cancer targets with experimental accuracy | Open Source [3] |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular Docking | Screens compound libraries against cancer targets to identify binders | Open Source [3] |

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics | Simulates drug-target interactions over time to assess binding stability | Open Source [3] |

| AIDDISON | AI-Driven Design | Generates novel molecular structures optimized for cancer targets | Commercial [17] |

| SYNTHIA | Retrosynthesis | Plans feasible synthetic routes for designed anticancer compounds | Commercial [17] |

| ClinVar | Variant Database | Assesses pathogenicity of cancer-associated genetic variants | Public [19] |

| ChEMBL | Compound Database | Provides bioactivity data for known anticancer compounds | Public [3] |

Computer-Aided Drug Design has evolved from a specialized tool to a central pillar of modern anticancer drug discovery. By integrating structural biology, computational chemistry, and increasingly artificial intelligence, CADD provides a systematic framework for addressing the profound challenges of oncology drug development. The core principles of structure-based and ligand-based design, implemented through sophisticated computational techniques, enable researchers to navigate complex chemical and biological spaces with unprecedented efficiency.

As CADD continues to advance through improved algorithms, integration with AI-driven platforms, and enhanced computational infrastructure, its role in accelerating anticancer discovery will only expand. The future of CADD in oncology lies not in replacing medicinal chemists and pharmacologists, but in empowering them to ask bolder questions, test more ambitious hypotheses, and ultimately deliver transformative cancer therapies to patients with greater speed and precision.

The Synergy of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning with CADD

The escalating global burden of cancer, projected to reach 35 million new cases annually by 2050, demands a transformative approach to drug discovery [9]. Traditional oncology drug development faces a critical challenge, with an estimated 97% of new cancer drugs failing in clinical trials, a success rate "well below 10%" [9]. This high attrition rate, coupled with timelines often exceeding a decade and costs surpassing $2.3 billion, underscores the pressing need for innovation [17]. Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) has long served as a computational cornerstone, employing methods like molecular docking and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling to rationalize and accelerate discovery [3]. Today, the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is revolutionizing CADD, creating a synergistic partnership that dramatically enhances the prediction, optimization, and prioritization of novel anticancer therapeutics [20] [11]. This whitepaper explores how the fusion of AI/ML with established CADD methodologies is reshaping the anticancer drug discovery pipeline, offering a powerful strategy to compress timelines, reduce costs, and improve the success rate of oncology drug development.

The CADD Foundation and the AI/ML Revolution

CADD operates through two primary, complementary approaches: structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD) [3]. SBDD relies on the three-dimensional structure of a biological target, typically a protein, to design molecules that fit into its binding sites. Key techniques include molecular docking, which predicts the orientation and affinity of a small molecule bound to a protein target, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which model the time-dependent behavior of the drug-target complex [3] [21]. In contrast, LBDD is employed when the target structure is unknown but data on active molecules exists. It utilizes methods like QSAR modeling, which correlates chemical structure features with biological activity through statistical models [3] [21].

While powerful, traditional CADD faces limitations, including high computational costs for methods like MD and a reliance on sometimes-oversimplified statistical models in QSAR [20]. The integration of AI, particularly its subfields of ML and Deep Learning (DL), is overcoming these constraints. AI can be defined as the field of creating machines or programs capable of performing tasks that require human intelligence, such as reasoning and problem-solving [9]. ML employs algorithms to learn patterns from data and make predictions, while DL uses complex neural networks to handle large, complex datasets like multi-omics data or histopathology images [22].

The synergy emerges as AI/ML augments core CADD capabilities. AI models enhance virtual screening by rapidly pre-filtering million-compound libraries, identify complex, non-linear patterns in QSAR that escape traditional statistics, and power generative AI to design novel molecular structures from scratch [20] [22]. This transforms CADD from a tool for simulating known interactions to an engine for discovering and optimizing new chemical matter with desired properties.

Table 1: Core CADD Techniques and Their AI/ML Enhancements

| CADD Technique | Traditional Approach | AI/ML Enhancement | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Literature mining, pathway analysis | Multi-omics data integration using ML to uncover hidden oncogenic drivers and novel targets [22] [11]. | Identifies previously overlooked therapeutic vulnerabilities. |

| Virtual Screening | Molecular docking of compound libraries | ML pre-screening and re-scoring of docking results; AI-powered tools like SILCS FragMaps for rapid binding site analysis [20] [13]. | Reduces screening time from days to minutes; improves hit rates. |

| QSAR | Statistical models (e.g., linear regression) | Deep Learning models (e.g., CNNs, GNNs) that discern complex, non-linear structure-activity relationships [20]. | Higher prediction accuracy for potency and selectivity. |

| de novo Drug Design | Fragment-based assembly | Generative AI models (VAEs, GANs) to create novel chemical structures with optimized properties [17] [22]. | Explores vast chemical space beyond known compounds. |

| ADMET Prediction | Isolated computational models | End-to-end AI frameworks that predict pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and synthesizability simultaneously [23] [17]. | Reduces late-stage attrition due to poor drug-like properties. |

AI-Enhanced Methodologies and Workflows

The integration of AI/ML into CADD is not a single step but a pervasive enhancement across the entire drug discovery workflow. Below are detailed methodologies that exemplify this synergy.

AI-Augmented Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

Traditional virtual screening relies on docking software like AutoDock Vina or Glide to rank compounds by predicted binding affinity [3]. AI enhances this by learning from both structural and ligand data to improve the identification of true hits.

Protocol: AI-Driven Virtual Screening

- Target Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the oncology target (e.g., PARP1) from experimental sources (X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM) or AI-based prediction tools like AlphaFold2 [3] [21].

- Library Preparation: Curate a large-scale (10^6 - 10^9 compounds) virtual library from databases like ZINC. Pre-filter for drug-likeness using rules like Lipinski's Rule of Five.

- AI Pre-screening: Employ a pre-trained ML classifier (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) to predict the likelihood of biological activity. This rapidly narrows the library to a more manageable subset of high-probability candidates.

- High-Throughput Docking: Perform molecular docking on the AI-prioritized subset using tools like SMINA or GNINA [23].

- AI Re-scoring: Apply a separate ML scoring function to the docking poses. These models, trained on large datasets of protein-ligand complexes, often provide a more accurate ranking of binding affinities than classical scoring functions [23].

- Visualization & Analysis: Use tools like the SILCS platform to generate "FragMaps" – visual maps of the binding site that show favorable regions for different chemical groups – to guide lead optimization of the top-ranked hits [13].

Generative AI for de novo Molecular Design

Generative AI moves beyond screening to the creation of novel molecular entities. Models like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can learn the chemical grammar of bioactive compounds and generate new, valid structures [21] [22].

Protocol: Generative Molecular Design for a Novel Kinase Inhibitor

- Data Curation: Assemble a training set of known kinase inhibitors from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL). Represent molecules as SMILES strings or molecular graphs.

- Model Training: Train a generative model (e.g., a GAN) on the curated dataset. The generator learns to produce new molecule structures, while the discriminator learns to distinguish between model-generated and real kinase inhibitors.

- Conditional Generation: Condition the model to generate molecules with specific properties, such as high predicted affinity for a HER2 mutant and low predicted affinity for off-target kinases to minimize side effects [20].

- In silico Validation: Run the generated molecules through a predictive pipeline:

- Activity Prediction: Use a DL-based QSAR model to predict IC50 values against the target.

- ADMET Prediction: Use AI platforms like AIDDISON to forecast pharmacokinetics and toxicity profiles [17].

- Synthetic Accessibility: Assess feasibility using retrosynthesis tools like SYNTHIA to ensure the molecules can be practically synthesized [17].

- Iterative Optimization: Use reinforcement learning to optimize the generated leads, iteratively improving compounds based on multiple predicted parameters (potency, solubility, etc.) [22].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of AI and CADD in anticancer drug discovery, from initial data input to final candidate selection.

AI-Driven ADMET and Property Prediction

A significant cause of clinical failure is unfavorable pharmacokinetics or toxicity. AI frameworks now integrate ADMET prediction early in the discovery process. Tools like DrugAppy use proprietary AI models trained on public datasets to predict key parameters such as permeability, metabolic stability, and drug-drug interactions [23]. This allows for the prioritization of compounds with a higher probability of clinical success.

Case Study: Validating the Integrated Workflow

The DrugAppy framework provides a compelling case study of this synergy in action for anticancer target discovery [23]. This end-to-end deep learning framework integrates AI algorithms with computational chemistry methodologies.

Objective: To identify novel inhibitors for two oncology targets: PARP1 (involved in DNA repair) and the TEAD family of proteins (key effectors in the Hippo signaling pathway).

Experimental Workflow & Results:

- High-Throughput Virtual Screening: Used SMINA and GNINA for structure-based screening of large compound libraries.

- Molecular Dynamics: Employed GROMACS for MD simulations to validate binding stability and interactions.

- AI-Predictive Modeling: Used both public and proprietary AI models to predict activity, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties.

- Experimental Validation: The top-ranked compounds were synthesized and tested in vitro.

Outcome: The workflow successfully identified:

- For PARP1, two novel molecules with activity comparable to the established drug Olaparib.

- For TEAD4, a compound that outperformed the reference inhibitor IK-930 in vitro.

This study demonstrates that the AI/CADD synergy can not only match but surpass the activity of existing inhibitors, validating the platform's ability to accelerate the discovery of high-quality lead compounds [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of an AI-enhanced CADD pipeline requires a suite of computational tools and platforms. The table below details key resources that form the core of a modern computational drug discovery laboratory.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Enhanced CADD

| Tool/Platform Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow | Application in Anticancer Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 [3] [21] | AI Structure Model | Predicts 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences with high accuracy. | Provides reliable models for oncology targets with unknown experimental structures. |

| AIDDISON [17] | AI-Powered SaaS Platform | Integrates AI/ML and CADD for molecule generation, virtual screening, and ADMET prediction. | Accelerates hit-to-lead optimization for kinase inhibitors, etc.; bridges design and synthesis. |

| SYNTHIA [17] | Retrosynthesis Software | Plans feasible synthetic routes for AI-designed molecules. | Ensures novel anticancer compounds (e.g., from generative AI) can be synthesized in the lab. |

| SILCS [13] | CADD Suite | Performs fragment-based mapping of binding sites (FragMaps) and virtual screening. | Identifies key interactions for targeting difficult cancer proteins (e.g., KRAS). |

| GROMACS [3] [23] | Molecular Dynamics | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Validates binding stability and mechanism of action for drug-target complexes. |

| AutoDock Vina [3] | Docking Software | Predicts ligand binding modes and affinities. | Standard tool for structure-based virtual screening of compound libraries. |

| DrugAppy [23] | End-to-End AI Framework | Combines HTVS, MD, and AI models for activity/ADMET prediction. | Validated platform for discovering novel PARP and TEAD inhibitors. |

The synergy of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning with CADD represents a paradigm shift in anticancer drug discovery. This powerful integration is transforming a traditionally slow, high-attrition process into a more efficient, predictive, and accelerated endeavor. By augmenting established computational methods—from target identification and virtual screening to de novo design and ADMET prediction—AI/ML is enabling researchers to navigate the vast complexity of cancer biology and chemical space with unprecedented precision. As these technologies continue to mature, their pervasive adoption promises to significantly compress the drug discovery timeline, reduce associated costs, and ultimately, deliver more effective and safer targeted therapies to cancer patients faster than ever before.

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) has emerged as a transformative force in modern pharmaceutical research, significantly accelerating the discovery and development of therapeutic agents. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the two principal CADD methodologies: structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD). Within the specific context of anticancer drug discovery, we examine how these computational approaches overcome traditional limitations, streamline development timelines, and enable targeting of complex cancer biology. By synthesizing current literature and emerging trends, this review demonstrates how the strategic integration of SBDD and LBDD methodologies is revolutionizing oncology drug discovery, offering researchers powerful tools to navigate the challenges of high attrition rates and escalating development costs.

The drug discovery and development process traditionally consumes approximately 10-14 years and over $1 billion per approved therapeutic, with oncology candidates facing particularly high attrition rates of approximately 97% in clinical trials [24] [9]. Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) has emerged as a pivotal approach to addressing these challenges, potentially reducing discovery costs by up to 50% while significantly compressing development timelines [24] [25]. CADD encompasses computational techniques that simulate drug-receptor interactions to predict binding affinity and biological activity, serving as a fundamental component of rational drug design paradigms [24].

In anticancer drug discovery, CADD's importance is magnified by the complexity of cancer pathogenesis, involving multiple signaling pathways, genetic mutations, and adaptive resistance mechanisms. The integration of CADD methodologies enables researchers to navigate vast chemical and target spaces efficiently, identifying and optimizing compounds with desired specificity for cancer-related targets while minimizing off-target effects [9] [26]. CADD techniques are broadly categorized into two complementary approaches: structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD), each with distinct methodologies, applications, and advantages in oncology contexts [25] [27].

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) relies on knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of the biological target, typically obtained through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [25] [24]. The central paradigm of SBDD involves identifying and characterizing binding sites on the target protein and designing molecules that complement these sites both geometrically and chemically [24].

Molecular docking, a cornerstone SBDD technique, predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to its target receptor [24] [27]. Docking algorithms employ scoring functions to evaluate and rank potential binding poses, enabling virtual screening of extensive compound libraries [24]. The dramatic expansion of available protein structures, fueled by advances in structural biology and breakthrough computational tools like AlphaFold (which has predicted over 214 million protein structures), has vastly expanded the applicability of SBDD to previously intractable targets [24].

For anticancer drug discovery, SBDD has proven particularly valuable in targeting oncogenic proteins with well-defined active sites, including kinases, transcription factors, and epigenetic regulators [26]. The approach enables precise design of inhibitors that compete with endogenous substrates or allosterically modulate protein function, offering strategies to circumvent resistance mutations common in cancer therapeutics [28].

Key SBDD Experimental Protocols

Molecular Docking and Virtual Screening Protocol

- Target Preparation: Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or via computational prediction using AlphaFold [24] [27]. Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands, then add hydrogen atoms and assign partial charges using tools like AutoDock Tools or Schrodinger's Protein Preparation Wizard [27].

- Binding Site Identification: Define the binding cavity using grid maps that encompass the known active site or potential allosteric sites. Tools including DOCK, AutoDock Vina, and Glide implement this process [27].

- Ligand Library Preparation: Compile a database of small molecules for screening, typically from sources like ZINC, Enamine REAL, or in-house collections [24]. Generate three-dimensional conformations and optimize geometries using energy minimization.

- Docking Execution: Perform computational docking of each compound in the library into the defined binding site. Most docking programs employ a combination of conformational search algorithms and scoring functions [24] [27].

- Post-Docking Analysis: Analyze top-ranked poses for favorable interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking). Visually inspect promising complexes using molecular visualization software such as PyMOL or Chimera [27].

- Hit Selection: Prioritize compounds based on docking scores, interaction patterns, and drug-like properties for experimental validation [24].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Protocol

- System Setup: Place the protein-ligand complex in a simulation box with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P water model). Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration [24].

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent and conjugate gradient minimization to remove steric clashes and bad contacts, typically for 5,000-50,000 steps [24].

- Equilibration: Conduct gradual heating from 0K to 300K over 100-500 ps using Langevin dynamics, followed by density equilibration at constant pressure (NPT ensemble) for 1-5 ns [24].

- Production Run: Perform extended MD simulation (typically 100 ns to 1 μs) using packages like GROMACS, AMBER, or OpenMM, saving coordinates at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) [24] [27].

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (Rg), solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), and hydrogen bonding patterns. Employ MM-PBSA/GBSA methods to estimate binding free energies [24].

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Structure-Based Drug Design

| Software Tool | Application | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking | Improved speed and accuracy, open-source | Free |

| GOLD | Molecular docking | Genetic algorithm, precise docking | Commercial |

| Glide | Molecular docking | Hierarchical filtering, accurate scoring | Commercial |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics | High performance, versatile | Free |

| AMBER | Molecular dynamics | Force field specificity, biomolecular focus | Commercial |

| OpenMM | Molecular dynamics | GPU acceleration, customizability | Free |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure prediction | High-accuracy protein structure prediction | Free |

SBDD Applications in Anticancer Drug Discovery

SBDD has contributed significantly to oncology therapeutics, with prominent examples including kinase inhibitors targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in lung cancer and BCR-ABL inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia [26]. The approach enables structure-guided optimization of lead compounds to enhance potency while reducing off-target effects, a critical consideration in cancer chemotherapy [28].

The Relaxed Complex Scheme (RCS) represents an advanced SBDD methodology that addresses target flexibility by incorporating multiple receptor conformations from molecular dynamics simulations into the docking process [24]. This technique is particularly valuable for identifying compounds that bind to cryptic allosteric sites or adapt to conformational changes in mutant oncoproteins that confer drug resistance [24] [28].

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD)

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) approaches are employed when three-dimensional structural information of the target protein is unavailable or incomplete [25] [27]. Instead of relying on target structure, LBDD utilizes knowledge of known active compounds to infer molecular features necessary for biological activity through the Similarity Property Principle, which states that structurally similar molecules tend to have similar properties [27].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling constitutes a fundamental LBDD technique, establishing mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors (physicochemical properties, structural features) and biological activity through statistical methods [25] [27]. Modern QSAR implementations increasingly incorporate machine learning algorithms, including random forests, support vector machines, and deep neural networks, to handle complex, non-linear relationships [9] [27].

Pharmacophore modeling represents another cornerstone LBDD approach, identifying the essential spatial arrangement of molecular features necessary for target recognition and biological activity [27]. A pharmacophore model typically includes features such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, and charged groups that collectively define the interaction capabilities of active ligands [27].

Key LBDD Experimental Protocols

QSAR Model Development Protocol

- Dataset Curation: Compile a structurally diverse set of compounds with consistent biological activity data (e.g., IC50, Ki) against the target of interest. Public databases like ChEMBL and BindingDB provide valuable sources [27].

- Chemical Structure Standardization: Normalize molecular structures by removing counterions, standardizing tautomers, and generating canonical representations using toolkits like RDKit or OpenBabel [27].

- Molecular Descriptor Calculation: Compute numerical representations of molecular structures using various descriptor types (e.g., topological, geometrical, electronic). Popular packages include Dragon, MOE, and RDKit [27].

- Dataset Division: Split data into training set (70-80%), validation set (10-15%), and test set (10-15%) using rational methods such as Kennard-Stone or sphere exclusion algorithms to ensure representative distributions [27].

- Model Construction: Apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., multiple linear regression, partial least squares, random forest, support vector machines) to establish relationships between descriptors and activity [9] [27].

- Model Validation: Assess model performance using internal cross-validation and external test set predictions. Calculate statistical metrics including R², Q², RMSE, and MAE [27].

- Model Interpretation: Analyze descriptor importance to extract chemically meaningful insights about structural features governing activity [27].

Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

- Conformational Analysis: Generate a representative set of low-energy conformations for each active compound in the training set using tools like OMEGA or CONFLEX [27].

- Pharmacophore Feature Identification: Define chemical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, aromatic rings, charged groups) common to active molecules [27].

- Model Generation: Align molecular conformations to identify optimal spatial arrangement of features using software such as Catalyst, Phase, or MOE [27].

- Model Validation: Evaluate model ability to discriminate between known active and inactive compounds, refining feature definitions and tolerances as needed [27].

- Virtual Screening: Employ the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D search query to screen compound databases, identifying new scaffolds with potential activity [27].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Ligand-Based Drug Design

| Software Tool | Application | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROCS | Shape similarity | Rapid overlay of chemical structures | Commercial |

| Phase | Pharmacophore modeling | Comprehensive modeling and screening | Commercial |

| MOE | QSAR/pharmacophore | Integrated cheminformatics platform | Commercial |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics | Open-source, Python-based | Free |

| KNIME | QSAR modeling | Visual workflow, data integration | Free |

| Canvas | QSAR modeling | Machine learning implementations | Commercial |

LBDD Applications in Anticancer Drug Discovery

LBDD has proven particularly valuable in anticancer drug discovery for scaffold hopping to identify novel chemotypes with activity profiles similar to known anticancer agents but improved pharmacological properties [27]. The approach has successfully been applied to multiple oncology target classes, including G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion channels, and nuclear receptors [27].

In cases where structural information is limited, such as for protein-protein interactions frequently dysregulated in cancer, LBDD provides a powerful strategy for lead identification and optimization [26]. The integration of LBDD with multi-parameter optimization enables simultaneous improvement of potency, selectivity, and ADMET properties, addressing the complex requirements of cancer therapeutics [28] [27].

Integrated Approaches and Emerging Trends

Hybrid CADD Strategies

The integration of SBDD and LBDD methodologies creates synergistic approaches that overcome limitations of individual techniques [29]. Sequential workflows typically apply LBDD for rapid filtering of large compound libraries followed by SBDD for detailed analysis of top candidates, optimally balancing computational efficiency with structural insights [29].

The parallel combination of SBDD and LBDD involves executing both approaches independently then combining results using data fusion algorithms such as rank-by-rank or rank-by-vote strategies to prioritize compounds identified by multiple methods [29]. Hybrid approaches integrate elements of both methodologies into unified frameworks, exemplified by interaction fingerprint techniques that capture structure-based interaction patterns within ligand-based similarity searching [29].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Integration

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing both SBDD and LBDD approaches [30] [31]. Deep learning architectures including graph neural networks and transformer models are enhancing prediction of protein-ligand interactions, de novo molecular design, and ADMET property forecasting [30] [31].

The application of large language models to chemical and biological data enables novel approaches to target identification, literature mining, and hypothesis generation, accelerating the early stages of anticancer drug discovery [30]. AI-driven platforms increasingly integrate multi-omics data to identify novel drug targets and biomarkers for patient stratification in oncology [9] [26].

Quantum Computing in CADD

Though still emergent, quantum computing holds transformative potential for CADD, particularly for simulating quantum mechanical phenomena in drug-receptor interactions and solving complex optimization problems in molecular design [30]. Quantum algorithms promise exponential speedup for molecular orbital calculations and protein folding simulations, potentially addressing current limitations in simulation accuracy and timescales [30].

Research Toolkit for CADD in Anticancer Discovery

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CADD Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application in Anticancer Drug Discovery | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Enamine REAL, ZINC, MCULE, SAVI | Ultra-large screening collections for virtual screening; REAL database contains >6.7 billion make-on-demand compounds [24] | Commercial |

| Protein Structure Databases | PDB, AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Source of experimental and predicted structures for SBDD; AlphaFold provides >214 million predicted structures [24] | Public |

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL, BindingDB, PubChem | Curated bioactivity data for QSAR modeling and machine learning training [27] | Public |

| Computational Infrastructure | GPU clusters, Cloud computing (AWS, Azure, GCP) | High-performance computing for molecular dynamics and deep learning applications [24] | Commercial |

| Specialized Software Suites | Schrödinger, OpenEye, BIOVIA | Integrated platforms for structure-based and ligand-based design [27] | Commercial |

Visualization of CADD Workflows

CADD Workflow Integration: This diagram illustrates the complementary nature of structure-based and ligand-based drug design approaches in anticancer drug discovery, culminating in integrated strategies that leverage both methodologies.

Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Drug Design represent complementary pillars of modern Computer-Aided Drug Design, each offering distinct advantages for addressing the complex challenges of anticancer drug discovery. SBDD provides atomic-level insights into drug-target interactions, enabling rational design of selective inhibitors, while LBDD leverages existing structure-activity knowledge to guide optimization when structural information is limited. The accelerating integration of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and emerging computational technologies with both approaches is rapidly expanding the boundaries of what is achievable in silico. For anticancer drug discovery specifically, the strategic implementation and integration of these CADD methodologies offers a powerful path to addressing the high attrition rates and escalating costs that have traditionally plagued oncology drug development, potentially delivering more effective, targeted therapies to cancer patients in significantly compressed timeframes.

CADD in Action: Core Methodologies and Workflows for Accelerating Anticancer Drug Discovery

Target Identification and Validation with AI-Driven Tools like AlphaFold

The process of discovering and developing a new drug is notoriously lengthy and expensive, often exceeding a decade and costing over $2.3 billion, with a failure rate of approximately 90% for oncologic therapies [17] [9]. Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) has long been employed to mitigate these challenges, and its integration with modern artificial intelligence (AI) is now fundamentally accelerating the discovery timeline, particularly for cancer therapeutics [31] [16]. At the heart of this transformation are AI-driven structural biology tools like AlphaFold, which have ushered in a new era for target identification and validation—the critical first steps in the drug discovery pipeline [32] [33]. By providing rapid, accurate protein structure predictions, these tools are deepening our understanding of cancer biology and enabling the design of novel therapeutics with unprecedented precision and speed, directly supporting the broader thesis that CADD significantly compresses the anticancer drug discovery timeline [32] [33] [31].

The AlphaFold Revolution in Structural Biology

AlphaFold represents a watershed moment in structural biology. It is a deep learning system that utilizes a series of neural networks to interpret amino acid sequence information and translate it into accurate three-dimensional spatial structures [33]. Its architecture is trained to recognize complex patterns in known protein sequences and structures, allowing it to predict the 3D coordinates of proteins with near-experimental accuracy, without being explicitly programmed with the laws of physics or chemistry [33]. The system's performance was demonstrated during the 14th Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP14) experiment, where it achieved a median backbone accuracy of ~0.96 Å for predicted structures, a level of precision that is revolutionizing the field [33].

The subsequent development of AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold 3 has extended this capability to predict the structures of protein complexes and their interactions with other biomolecules like DNA, RNA, and ligands, which is crucial for understanding the protein-protein interactions (PPIs) often dysregulated in cancer [33]. The AlphaFold Protein Structure Database has democratized access to structural information, providing over 214 million predicted protein structures, thereby offering unprecedented insights into previously undruggable cancer targets [33].

Table 1: Evolution of AlphaFold and Its Impact on Drug Discovery

| Model Version | Key Capability | Significance for Cancer Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 2 | Highly accurate single-chain protein structure prediction [33]. | Enabled target identification for proteins with no experimental structure [32] [33]. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Prediction of protein-protein complexes [33]. | Facilitated the modulation of PPIs, a key frontier in oncology [32] [33]. |

| AlphaFold 3 | Prediction of protein interactions with DNA, RNA, ligands, and ions [33]. | Allows for a systems-level view of drug-target interactions and signaling pathways [33]. |

| AlphaFold Database | Provides free access to over 214 million predicted structures [33]. | Dramatically reduced the time from target gene sequence to structural hypothesis [32] [33]. |

AI-Driven Target Identification and Validation in Oncology

Target identification and validation involves pinpointing a specific biological macromolecule (e.g., a protein) involved in a disease process and confirming that modulating its activity produces a therapeutic effect. In cancer, these targets are often proteins governing cell proliferation, survival, and metastasis [33]. AI-driven tools are accelerating every stage of this process.

Target Identification

- Exploring the Dark Proteome: Many cancer-relevant proteins, such as those involved in intracellular signaling or disordered regions, are difficult to study with experimental methods. AlphaFold illuminates this "dark proteome" by providing reliable structural models, revealing new potential drug targets [33].