High-Throughput qPCR in Cancer Biomarker Screening: A Comprehensive Guide for Translational Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of high-throughput quantitative PCR (HT-qPCR) and its transformative role in cancer biomarker screening and validation.

High-Throughput qPCR in Cancer Biomarker Screening: A Comprehensive Guide for Translational Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of high-throughput quantitative PCR (HT-qPCR) and its transformative role in cancer biomarker screening and validation. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of cancer biomarkers, including circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), microRNAs (miRNAs), and mRNA. It details methodological workflows, from automated liquid handling and nanofluidics to data analysis pipelines. The scope extends to practical troubleshooting, optimization strategies for challenging samples, and rigorous validation protocols. Finally, it presents a comparative assessment of HT-qPCR against other genomic technologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS), offering insights to guide platform selection for precision oncology applications.

The Rise of Precision Oncology and the Critical Role of Biomarkers

The Global Cancer Burden and the Imperative for Early Detection

The global burden of cancer is substantial and growing, underscoring an urgent need for scalable early detection technologies. In 2022, there were an estimated 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million deaths worldwide according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. The most common cancers include lung (2.5 million new cases), breast (2.3 million), and colorectal cancer (1.9 million) [1]. Projections indicate a dramatic increase to 35 million new annual cases by 2050, a 77% rise from 2022 figures, with the most significant proportional increases expected in low and medium-resource countries [1].

This escalating burden creates a pressing imperative for diagnostic tools that are not only accurate but also cost-effective, rapid, and deployable at scale. High-throughput quantitative PCR (qPCR) represents a foundational technology in this effort, combining high analytical sensitivity, rapid turnaround time, and cost-efficiency essential for informing therapeutic decision-making at scale [2]. Its utility is particularly pronounced in time-sensitive or resource-constrained settings where complex infrastructure is unavailable.

Quantitative Analysis of the Global Cancer Landscape

Table 1: Global Incidence and Mortality for Major Cancers (2022)

| Cancer Type | New Cases (Millions) | Proportion of Total Cases | Deaths (Millions) | Proportion of Total Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 2.5 | 12.4% | 1.8 | 18.7% |

| Breast | 2.3 | 11.6% | 0.67 | 6.9% |

| Colorectal | 1.9 | 9.6% | 0.9 | 9.3% |

| Prostate | 1.5 | 7.3% | - | - |

| Stomach | 0.97 | 4.9% | 0.66 | 6.8% |

| Liver | - | - | 0.76 | 7.8% |

| Total (All Cancers) | 20.0 | 100% | 9.7 | 100% |

Table 2: Projected Cancer Incidence Growth and Health System Preparedness

| Development Index | Projected Increase in Incidence by 2050 | Countries Adequately Financing Cancer Services |

|---|---|---|

| High HDI Countries | +4.8 million cases (Greatest absolute increase) | Higher likelihood of service coverage |

| Medium HDI Countries | 99% increase | Limited data available |

| Low HDI Countries | 142% increase (Largest proportional increase) | Significant gaps in service financing |

| Global Average | 77% increase (35 million total cases) | 39% of countries cover basic cancer management |

Alarming disparities exist in cancer burden and care accessibility. For example, women in lower Human Development Index (HDI) countries are 50% less likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer than women in high HDI countries, yet they face a much higher risk of mortality due to late diagnosis and inadequate treatment access [1]. These inequities highlight the critical need for accessible, affordable, and scalable diagnostic technologies like qPCR that can function effectively in diverse healthcare environments.

High-Throughput qPCR as a Solution for Early Detection

Technical Advantages in Oncology Diagnostics

qPCR offers several distinct advantages that make it particularly suitable for addressing the global cancer detection challenge:

Multiplexing Capability: Modern qPCR platforms can simultaneously detect multiple clinically relevant mutations in a single reaction without compromising sensitivity or speed [2]. For non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), multiplexed qPCR panels can simultaneously assess alterations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF and ALK, delivering results faster with less input material than sequential sequencing approaches [2].

Rapid Turnaround and Minimal Infrastructure: Unlike sequencing platforms that can take days to generate data, qPCR delivers clinically actionable results within hours, which is critical for selecting targeted therapies or enrolling patients in mutation-driven clinical trials [2]. The technology is highly scalable and automation-friendly, supporting high-throughput testing in 96- or 384-well formats without significant capital investment [2].

Cost-Effectiveness for Population-Scale Screening: qPCR remains significantly more cost-effective than next-generation sequencing (NGS), with test costs typically ranging from $50 to $200 compared to $300 to $3,000 for NGS [2]. This affordability makes it particularly well-suited for large-scale screening initiatives and routine clinical diagnostics in resource-conscious healthcare systems.

Innovations in qPCR Chemistry

Recent advancements in qPCR chemistry have further enhanced its utility for cancer biomarker detection:

- Inhibitor Resistance: Next-generation polymerases and buffers are engineered to tolerate PCR inhibitors commonly found in clinical matrices such as heparinized plasma, whole blood, or FFPE-derived nucleic acids [2].

- Thermal Stability: Enzymes now withstand higher-temperature, faster-cycling protocols without loss of activity, enabling faster run times and greater assay reliability [2].

- Lyophilization Compatibility: Ambient-temperature stable formulations support cold chain-independent transport and storage, ideal for decentralized testing environments [2].

- Multiplexing Efficiency: Advanced master mixes and probe systems enable detection of multiple mutations in a single reaction, critical for cancers with complex mutational profiles [2].

Application Note: Multiplex RT-qPCR for Breast Cancer Subtyping

Background and Rationale

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer mortality globally, with approximately 2.3 million new cases anticipated worldwide [3]. Current diagnostic standards rely heavily on Immunohistochemistry (IHC), which can be slow, expensive, and dependent on proficient pathologists [3]. We developed a novel multiplex Reverse Transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) approach with touch-down methods to enhance the accuracy, speed, and cost-effectiveness of BC diagnosis and subtyping.

Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tumor block samples. In our validation study, we used 61 tumor samples from different breast cancer groups (Luminal type, TN, HER2 positive, and TP subtypes) and 9 benign samples [3].

- RNA Extraction: Extract total RNA from FFPE samples using the Quick-DNA/RNATM FFPE Kit (or equivalent), following manufacturer instructions. Evaluate RNA concentration and purity using a Nano-Drop One C spectrophotometer [3].

- Storage: Store isolated RNA at -80°C until use.

Primer and Probe Design

- Target Genes: Design primers and probes for ESR, PGR, HER-2, Ki67, HIF1A, ANG, and VEGF genes, using RPL13A as the endogenous control gene [3].

- Preparation: Resuspend lyophilized primers and probes in PCR-grade water to 100 μM final concentration, then prepare 1:10 dilution to achieve 10 μM working concentration [3].

Multiplex RT-qPCR Workflow

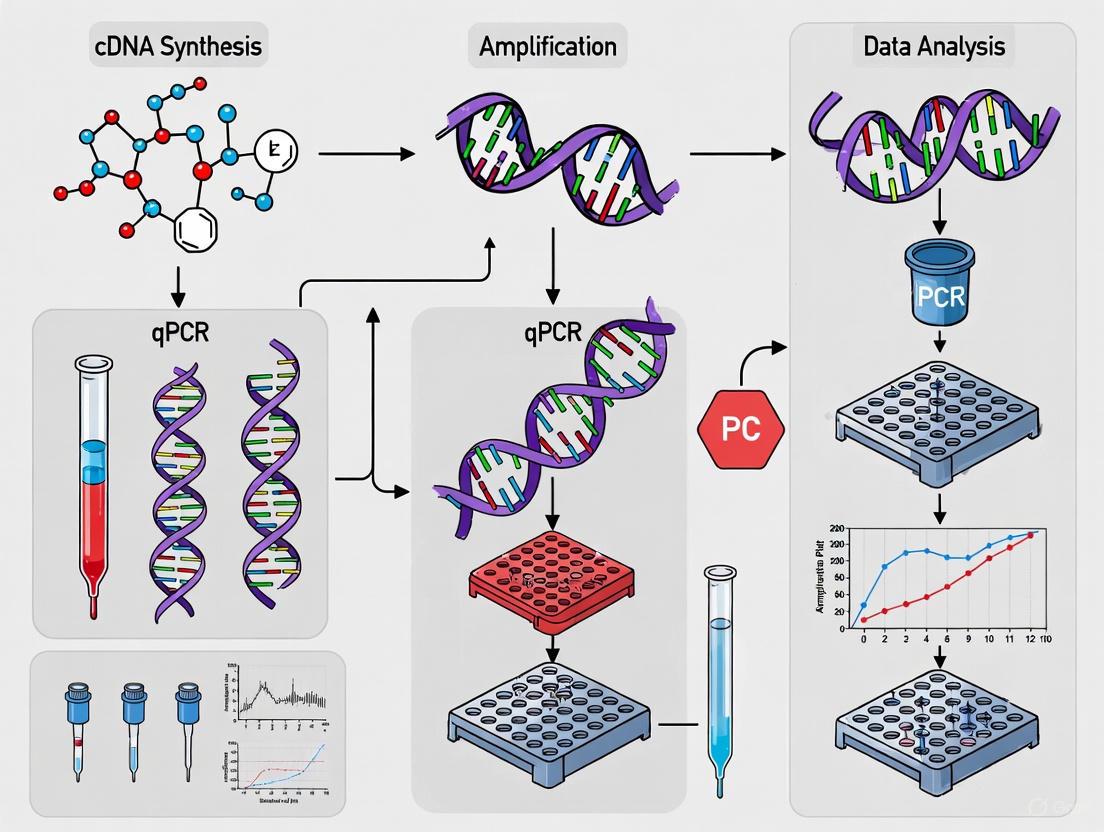

Diagram 1: Multiplex RT-qPCR workflow for breast cancer subtyping

- cDNA Formation: 50°C for 10 minutes [3]

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes [3]

- Touch-Down PCR Cycling:

- 3 cycles: 95°C for 10s, 70°C for 15s

- 3 cycles: 95°C for 10s, 67°C for 15s

- 3 cycles: 95°C for 10s, 63°C for 15s

- Final Amplification: 40 cycles: 95°C for 5s, 60°C for 30s (with data collection) [3]

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- ΔCT Calculation: Calculate ΔCT values for target genes using the reference gene (RPL13A) as control: ΔCT = CT(target) - CT(reference) [3]

- Inverted ΔCT: Subtract ΔCT values from the maximum PCR cycle number to obtain inverted ΔCT values [3]

- Normalization: Mathematically normalize inverted ΔCT values to the scale of IHC for direct comparison with immunohistochemistry results [3]

- Fold Change Calculation: Use the ΔΔCT method to calculate gene expression fold changes: Fold Change = 2^(-ΔΔCT) [3]

Results and Validation

This methodology demonstrated remarkable precision, nearly equivalent to IHC, in detecting gene expressions vital for BC diagnosis and subtyping [3]. The touch-down PCR approach consistently yielded significantly lower Cycle Threshold (CT) values, enhancing detection sensitivity [3]. Additionally, the protocol enabled exploration of angiogenesis gene expression (Hif1A, ANG, and VEGFR), shedding light on the metastatic potential of the tested BC tumours [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for High-Throughput qPCR Cancer Biomarker Screening

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Quick-DNA/RNATM FFPE Kit | Extracts high-quality RNA/DNA from challenging FFPE samples; critical for working with archival clinical specimens [3]. |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Inhibitor-resistant master mixes | Engineered to tolerate PCR inhibitors in clinical matrices (heparinized plasma, whole blood); enables direct amplification without purification [2]. |

| Reference Genes | RPL13A, GAPDH | Endogenous controls for data normalization; RPL13A demonstrated stable expression across breast cancer subtypes [3]. |

| Primers & Probes | Target-specific primers with dual hybridization probes | Enable multiplex detection of cancer biomarkers (ESR, PGR, HER2, Ki67); designed for specific amplification and reliable detection [3]. |

| Ambient-Stable Formulations | Lyophilized qPCR reagents | Reduce cold chain requirements; ideal for decentralized testing or global distribution to resource-limited settings [2]. |

| Targeted Biomarker Panels | Aspyre Lung Reagents, AmoyDx Pan Lung Cancer PCR Panel | Multiplexed panels for specific cancers; simultaneously assess alterations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, ALK in NSCLC [2]. |

Biomarker Development Pipeline: From Discovery to Clinical Application

The translation of cancer biomarkers from initial discovery to clinical application follows a structured pathway with distinct stages:

Diagram 2: Cancer biomarker development and validation pipeline

Key Considerations at Each Stage

Biomarker Discovery: Study design quality is paramount; "samples of convenience" can introduce confounding factors and contribute to false positive associations [4]. Large-scale, well-predefined prospective studies provide the most reliable evidence [4].

Assay Development and Analytical Validation: Following discovery, candidate biomarkers must be adapted to robust, clinically applicable platforms like qPCR [4]. This requires careful optimization of sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility under standardized conditions.

Clinical Validation and Implementation: Biomarkers must demonstrate clinical utility in improving patient outcomes [4]. Only an estimated 0.1% of initially discovered biomarkers successfully complete this translation process [4].

The growing global cancer burden, projected to reach 35 million new cases annually by 2050, demands urgent implementation of accessible, scalable, and cost-effective early detection technologies [1]. High-throughput qPCR represents a foundational technology in this effort, with demonstrated utility across multiple cancer types including lung, breast, and hepatocellular carcinomas [2] [3] [5].

The multiplex RT-qPCR protocol detailed herein for breast cancer subtyping exemplifies how this technology can deliver precision nearly equivalent to IHC while offering advantages in speed, cost-effectiveness, and objectivity [3]. As the field advances, ongoing innovations in qPCR chemistry, multiplexing efficiency, and ambient-stable formulations will further enhance the deployability of these assays in diverse healthcare settings worldwide [2].

For researchers and drug development professionals, focusing on robust assay design, careful validation, and attention to the specific requirements of the biomarker development pipeline will be essential to translating promising discoveries into clinically impactful tools that can reduce the global cancer burden.

Cancer biomarkers have revolutionized oncology, shifting the paradigm from a one-size-fits-all approach to personalized precision medicine. A biomarker refers to any biological marker found in blood, body fluids, or tissues that signals the presence of normal or abnormal biological processes, conditions, or diseases [6]. In oncology, these biomarkers provide critical insights into cancer type, likely disease progression, recurrence chances, and expected treatment outcomes [6]. They are broadly classified as prognostic biomarkers, which indicate the natural course of the disease independent of treatment, and predictive biomarkers, which forecast how a cancer will respond to a specific therapy [6].

The ideal cancer biomarker should possess attributes that facilitate easy, reliable, and cost-effective assessment, coupled with high sensitivity and specificity [6]. It should demonstrate remarkable detectability at early stages and accurately reflect tumor burden, enabling continuous monitoring of disease evolution during treatments [6]. The rapid expansion of biological sciences has markedly driven technological advancements in biomarker discovery, from early immunological techniques to contemporary sophisticated analytical methodologies including mass spectrometry, protein and DNA arrays, and next-generation sequencing [6].

Classes of Cancer Biomarkers: From Coding to Non-Coding RNAs

DNA and mRNA Biomarkers

Traditional cancer biomarkers primarily focused on DNA alterations and protein-coding mRNA. These include specific genetic alterations such as mutations, amplifications, and translocations at the single gene level, as well as comprehensive genetic profiles created through microarrays [6]. For example, identifying activating epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations in non-small cell lung cancer patients enables clinicians to select EGFR inhibitors for those most likely to respond [7]. Similarly, multi-gene expression patterns have been exploited as biomarkers for clinical outcomes in numerous cancer studies, such as the PAM50 50-gene panel effectively used for breast cancer classification [8].

Table 1: DNA and mRNA Biomarkers in Cancer

| Biomarker Type | Example | Cancer Type | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Mutation | EGFR mutations | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Predicts response to EGFR inhibitors |

| Gene Amplification | HER2 amplification | Breast, Gastric Cancer | Guides HER2-targeted therapies |

| Gene Fusion | ALK rearrangements | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Predicts response to ALK inhibitors |

| mRNA Signature | PAM50 | Breast Cancer | Molecular subtyping and prognosis |

| DNA Methylation | F12 gene CpG site | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Early detection in liquid biopsies |

The Emerging Role of Non-Coding RNAs

Non-coding RNAs represent a significant proportion of the human genome and have established crucial roles in cancer biology. Among these, microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have attracted substantial research interest as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets [9].

MicroRNAs are short RNA transcripts of 18-24 nucleotides that regulate gene expression at the translational level [9]. According to the canonical view, miRNAs function as negative regulators of gene expression that upon binding to the 3'-untranslated region of target messenger RNA (mRNA) cause a block of translation and/or degradation of the transcript [9]. A single miRNA can target several mRNAs, enabling simultaneous regulation of multiple target genes both within a single pathway or across different pathways [9]. MiRNA expression patterns are tissue specific and often define the physiological nature of the cell, with altered expression occurring in numerous diseases including cancer [9].

Long non-coding RNAs are non-coding RNAs exceeding 200 nucleotides in length that play important roles as transcriptional or post-transcriptional regulators [9]. These molecules demonstrate high stability in the bloodstream due to extensive secondary structures, transport by protective exosomes, and stabilizing post-translational modifications, making them particularly attractive as circulating biomarkers [10]. Many lncRNAs function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors, influencing tumour growth, invasion, and metastasis by regulating key genes involved in cancer development [9] [10].

Table 2: Non-Coding RNA Biomarkers in Cancer Diagnostics

| RNA Type | Example | Cancer Type | Diagnostic Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | miR-21 | Various Cancers | Suppresses p53, TGF-β and mitochondrial apoptosis pathways |

| miRNA | miR-155 | Various Cancers | Binds to coding sequence of target mRNAs; oncogenic |

| lncRNA | PCA3 | Prostate Cancer | FDA-approved for prostate cancer diagnosis (Progensa) |

| lncRNA | HOTAIR | Colorectal Cancer | 92.5% specificity for identifying colorectal cancer |

| lncRNA | MALAT-1 | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | 96% specificity for detecting NSCLC |

| lncRNA | LINC00152 | Gastric Cancer | 85.2% specificity for detecting gastric cancer |

| lncRNA | UCA1 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 82.1% specificity for detecting HCC |

High-Throughput qPCR: A Cornerstone Technology in Biomarker Screening

Advantages of qPCR in Oncology Diagnostics

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains a foundational tool in oncology diagnostics despite the emergence of newer technologies like next-generation sequencing [2]. Its combination of high analytical sensitivity, rapid turnaround time, and cost-efficiency makes it uniquely suited for informing therapeutic decision-making at scale, especially in time-sensitive or resource-constrained settings [2]. Key advantages include:

Multiplexing Capability: qPCR allows multiple clinically relevant mutations to be detected in a single reaction without compromising sensitivity or speed. For example, in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), multiplexed qPCR panels can simultaneously assess alterations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF and ALK – delivering results faster and using less input material than sequential or panel-based NGS approaches [2].

Rapid Turnaround: Unlike sequencing platforms, which can take days to generate and analyze data, qPCR delivers clinically actionable results within hours. This rapid turnaround is especially valuable in time-sensitive scenarios such as selecting targeted therapies or enrolling patients into mutation-driven clinical trials [2].

Cost-Effectiveness: Test costs typically range from $50 to $200 – substantially less than the $300 to $3,000 price range of NGS. This affordability makes qPCR especially well-suited for large-scale screening initiatives and routine clinical diagnostics [2].

Innovations in qPCR Chemistry and Applications

Recent innovations have significantly enhanced qPCR's clinical utility for cancer biomarker detection:

Inhibitor Resistance: Next-generation polymerases and buffers are engineered to tolerate PCR inhibitors commonly found in clinical matrices, such as heparinized plasma, whole blood, or FFPE-derived nucleic acids [2].

Thermal Stability: Enzymes now withstand higher-temperature, faster-cycling protocols without loss of activity – enabling faster run times and greater assay reliability [2].

Multiplexing Efficiency: Advanced master mixes and probe systems enable detection of multiple mutations in a single reaction – critical for cancers with complex mutational profiles [2].

Sensitivity Optimization: Methodologies have been developed to quantify surrogate markers of immunity from very low numbers of PBMCs, reducing costs by almost 90% compared to standard practice while maintaining single-cell analytical sensitivity [11].

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Detection

High-Throughput, Cost-Optimized RT-qPCR for Immune Marker Profiling

This protocol enables sensitive and specific quantification of surrogate transcriptional markers of immunity from low numbers of PBMCs, optimized for high-throughput screening [11].

Sample Preparation and Stimulation

- Isolate PBMCs from healthy donors by standard density gradient centrifugation and cryopreserve in 90% FBS/10% DMSO.

- Before use, thaw samples rapidly at 37°C, treat with DNase I (100μg/mL), and rest for 18 hours at 2x10^6 cells/mL in complete R10 media at 37°C and 5% CO2.

- Stimulate with synthetic peptides (10μg/mL) representing well-defined CD4+ or CD8+ T cell epitopes alongside PMA/Iono mitogen positive-control (50ng/mL PMA, 1,000ng/mL Ionomycin) and media-only negative-control.

- For RT-qPCR analysis, stimulate PBMCs in 200μL R10 media in 96-well U-bottom plates.

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

- Extract RNA using MagMAX mirVana Total RNA Isolation Kit following manufacturer's instructions.

- Convert extracted RNA to cDNA with SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System.

- For cost-optimized "Half Volume" or "Quarter Volume" protocols, use reagents at 50% or 25% of manufacturer-recommended volumes, maintaining equal reaction volume with DEPC-Treated H2O.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

- Determine mRNA copies/reaction with absolute quantification based on a standard curve.

- Use IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2 specific desalt-grade primers at 500nM with SYBR Green Master-Mix.

- Run reactions in technical triplicate at either 10μL or 5μL total volume.

- For 5μL reaction volumes, add 1μL of reverse transcription eluent diluted 1:4 in Ultra-Pure H2O.

- Acquire data using a QuantStudio5 Real-Time PCR system.

- Calculate primer reaction efficiency by amplification of logarithmically diluted cDNA.

Circulating lncRNA Detection from Blood Samples

This protocol outlines the recommended approach for investigating circulating lncRNAs in blood samples from cancer patients [10].

Sample Collection and Processing

- Collect peripheral blood in EDTA tubes and process within 2 hours of collection.

- Centrifuge at 1,200 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma.

- Transfer supernatant to a fresh tube and centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove residual cells.

- Aliquot cleared plasma and store at -80°C until RNA extraction.

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Extract RNA from plasma using commercial kits specifically designed for liquid biopsies.

- Include synthetic spike-in RNAs during extraction to monitor efficiency and potential degradation.

- Assess RNA quality and quantity using spectrophotometry or fluorometry.

Reverse Transcription and qPCR

- Perform reverse transcription using gene-specific primers or random hexamers.

- Use stem-loop RT primers for specific miRNA detection if analyzing multiple RNA species.

- Conduct qPCR reactions using SYBR Green or TaqMan chemistry.

- Normalize data using stable reference genes or spike-in controls.

- Analyze using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method for relative quantification.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows and Biomarker Classification

High-Throughput qPCR Workflow for Cancer Biomarker Screening

Cancer Biomarker Classification and Clinical Applications

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for High-Throughput qPCR Biomarker Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA/DNA from various sample types | MagMAX mirVana Total RNA Isolation Kit | Optimized for challenging samples including liquid biopsies |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Conversion of RNA to cDNA for qPCR analysis | SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System | High efficiency and robustness for limited samples |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Enzymes and buffers for efficient amplification | Luna Universal qPCR Master Mix, ssoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Master-Mix | Inhibitor-resistant, thermal stability, multiplexing compatibility |

| qPCR Primers & Probes | Target-specific amplification | PrimerBank primers, Custom TaqMan assays | High specificity and efficiency for biomarker targets |

| Reference Genes | Normalization of qPCR data | GAPDH, β-actin, 18S rRNA | Stable expression across sample types and conditions |

| Automation Equipment | High-throughput sample processing | Liquid handlers, automated pipetting systems | Enables miniaturization and reproducible results |

| Quality Control Tools | Assessment of RNA/DNA quality | Bioanalyzer, spectrophotometers | Ensures input material quality for reliable results |

The future of cancer biomarker research lies in shifting towards multiparameter approaches that incorporate diverse molecular classes including DNA, mRNA, miRNAs, and lncRNAs, alongside dynamic processes and immune signatures [6]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is further revolutionizing biomarker analysis by identifying subtle patterns in large datasets that human observers might miss [8]. These technologies enable the integration and analysis of various molecular data types with imaging to provide a comprehensive picture of cancer, consequently enhancing diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic recommendations [12] [8].

High-throughput qPCR maintains its pivotal role in this evolving landscape due to its unique combination of speed, cost-efficiency, and scalability [2]. As biomarker discovery continues to advance, qPCR technologies have kept pace through innovations in chemistry, automation, and miniaturization, ensuring their continued relevance in both research and clinical settings [11] [2]. By embracing technological sophistication without compromising practical utility, the field moves closer to realizing the full potential of personalized cancer diagnosis and treatment through comprehensive biomarker profiling.

The global molecular diagnostics market is demonstrating robust growth, propelled by its indispensable role in modern healthcare. This expansion is quantified by several key reports, all pointing towards a consistent upward trajectory, though with varying projections based on different methodological assumptions. The market was valued at approximately USD 27 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow to between USD 40.4 billion and USD 63.86 billion by 2034, reflecting compound annual growth rates (CAGRs) of 4.2% to 3.87% over the forecast period [13] [14]. This growth is primarily fueled by the rising global prevalence of infectious diseases, technological advancements in diagnostic techniques, an increasing focus on early disease diagnosis, and the growing demand for point-of-care (POC) testing solutions [13]. Furthermore, the global geriatric population, which is more susceptible to chronic diseases, is a significant demographic driver; the population aged 60 and above is projected to rise from 1.1 billion in 2023 to 1.4 billion by 2030, necessitating more frequent health monitoring [13].

Table 1: Global Molecular Diagnostics Market Size Projections

| Report Source | Base Year Value | Projected Year Value | Forecast Period | CAGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM Insights [13] | USD 27 Billion (2024) | USD 40.4 Billion (2034) | 2025-2034 | 4.2% |

| Precedence Research [14] | USD 45.11 Billion (2025) | USD 63.86 Billion (2034) | 2025-2034 | 3.87% |

| Research and Markets [15] | USD 15.9 Billion (2025) | USD 30.9 Billion (2035) | 2025-2035 | 6.2% |

The application of molecular diagnostics in oncology is a particularly fast-growing segment, driven by the critical need for early detection and the development of precision medicine [14]. Molecular diagnostics enable the identification of cancer-related biomarkers at very early stages, allowing for treatment initiation before symptoms arise. In 2023, nearly 1.96 million new cancer cases were projected in the United States alone, underscoring the massive demand for accurate diagnostic methods [14]. Techniques such as quantitative PCR (qPCR), next-generation sequencing (NGS), and microarrays are pivotal for detecting genetic mutations, gene expression patterns, and other nucleic acid-based biomarkers that guide treatment decisions and facilitate personalized therapeutic strategies [16] [15].

Table 2: Molecular Diagnostics Market Segmentation (2024 Estimates)

| Segmentation Basis | Leading Segment | Market Share / Key Stat |

|---|---|---|

| Product Type | Reagents & Kits | ~66-70% of market [13] [14] |

| Technology | Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) | 70.4% of market [13] |

| Application | Infectious Disease Diagnostics | ~78% of market [14] |

| End User | Hospitals & Central Laboratories | Largest market share [14] |

| Regional Market | North America | >40% revenue share [14] |

| Fastest-Growing Region | Asia Pacific | CAGR of ~4.9% [14] |

Application Note: High-Throughput qPCR for Cancer Biomarker Screening

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and its derivative, reverse transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR), are cornerstone technologies in molecular diagnostics and biomarker research due to their sensitivity, specificity, and capacity for precise quantification [17]. In the context of cancer, these techniques allow for the rapid, sensitive, and accurate detection of potential biomarkers from a variety of sample sources, including formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, circulating tumor cells, and liquid biopsies [16]. The primary biomarkers quantified include DNA, mRNA, microRNA (miRNA), and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA). Notably, miRNA is a highly stable biomarker resistant to fragmentation, making it an excellent candidate for precision diagnostics in cancer [16]. The power of qPCR is now being amplified through high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies, which enable the processing of thousands of reactions simultaneously, dramatically accelerating the pace of biomarker discovery and validation.

Detailed Protocol: A Cost-Optimized HTS qPCR Workflow

The following protocol is adapted from an HTS-optimized RT-qPCR assay designed for quantifying surrogate markers of immunity, with principles directly applicable to cancer biomarker screening from limited cell samples [18]. This protocol is miniaturized to reduce reagent costs by nearly 90% while maintaining high sensitivity and specificity.

Sample Preparation and Stimulation

- Cell Source: Utilize relevant cell samples, such as purified cancer cell lines, patient-derived PBMCs, or other primary cells.

- Resting: Thaw and rest cells (e.g., 2x10^6 cells/mL) in complete media for 18 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2.

- Stimulation: Stimulate cells with the desired oncogenic or therapeutic agents. Include a mitogen-positive control (e.g., PMA/Ionomycin) and a media-only negative control. For kinetic studies, harvest cells at multiple time points (e.g., hourly from 0-12 hours) to identify peak biomarker expression [18].

RNA Extraction

- Method: Extract total RNA using a magnetic bead-based RNA isolation kit, such as the MagMAX mirVana Total RNA Isolation Kit, following the manufacturer's instructions. This method is efficient for 96-well or 384-well format processing [18].

Reverse Transcription (cDNA Synthesis) - Cost Optimized

- Kit: Use a high-efficiency system like the SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System.

- Miniaturization: Scale down the reaction volumes to 25% of the manufacturer's recommended volume to drastically reduce costs while maintaining cDNA yield and quality [18].

- Example: If the standard protocol uses 20 µL, the miniaturized reaction would be 5 µL.

- Priming: Use a combination of oligo(dT) and random primers for comprehensive cDNA synthesis.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) - High-Throughput Setup

- Reaction Volume: Perform qPCR in a miniaturized 5 µL total reaction volume [18].

- Chemistry: Use a SYBR Green or probe-based master mix, such as the ssoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Master-Mix.

- Template: Add 1 µL of a 1:4 dilution of the synthesized cDNA from the previous step.

- Primers: Use gene-specific primers at a concentration of 500 nM. For cancer biomarkers, this could include primers for mRNA, miRNA (using a specialized Mir-X miRNA kit), or lncRNA targets [16].

- Platform: Run the reactions on a high-throughput real-time PCR system capable of handling 384-well or higher-density plates, such as the SmartChip Real-Time PCR System, which allows for thousands of nanoscale reactions per chip [16].

- Replication: Conduct all reactions in technical triplicate in accordance with MIQE guidelines to ensure reproducibility [18].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Baseline and Threshold Setting: Accurate quantification cycle (Cq) values are critical. The baseline should be set using early cycles (e.g., 5-15) where fluorescence is stable. The threshold must be set within the exponential phase of all amplification curves, sufficiently above the baseline to ensure signal significance [19].

- Relative Quantification (ΔΔCq Method): This is the most common method for gene expression analysis [17] [20].

- Normalization: Normalize the Cq of the target gene (ΔCq) to a stable endogenous control (reference gene) [17].

- Calibration: Compare the ΔCq of the test sample to the ΔCq of a control sample (e.g., untreated cells) to calculate the ΔΔCq.

- Fold Change: Calculate the fold change in gene expression using the formula: 2^(-ΔΔCq) [20].

- PCR Efficiency: For the ΔΔCq method to be valid, the amplification efficiency of the target and reference genes must be approximately equal and near 100% (90-110%). Efficiency (E) is calculated from a standard curve of serial dilutions using the formula: E (%) = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) × 100 [20]. If efficiencies are not equivalent, alternative models like the Pfaffl method should be used [19] [20].

The workflow for this high-throughput qPCR protocol, from sample preparation to data analysis, is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of high-throughput qPCR for cancer biomarker discovery relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The following table details key solutions for constructing a robust screening pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput qPCR Biomarker Screening

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput RNA Isolation Kits | Efficient, automated-friendly total RNA extraction from multiple sample types (cells, FFPE tissue). | MagMAX mirVana Total RNA Isolation Kit [18] |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | High-efficiency reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA, crucial for sensitive detection. | SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System [18] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Provides enzymes, buffers, and fluorescence chemistry (SYBR Green or Probe-based) for amplification. | ssoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Master-Mix [18] |

| Pre-Designed qPCR Assays/Panels | Pre-validated primer/probe sets for specific cancer-related genes or pathways; save time and ensure reproducibility. | Lyophilized primer sets for colorectal, lung, prostate cancer etc.; PCR arrays for pathways [16] [17] |

| miRNA Quantification Kits | Specialized single-step, single-tube reaction for accurate and sensitive quantification of stable miRNA biomarkers. | Mir-X miRNA qRT-PCR TB Green Kit [16] |

| High-Throughput qPCR Systems | Automated platforms for running and analyzing thousands of nanoscale qPCR reactions. | SmartChip Real-Time PCR System [16] |

| Endogenous Controls | Stable reference genes (e.g., housekeeping genes) for normalization of qPCR data. | TaqMan Endogenous Controls (e.g., for human, mouse, rat) [17] |

Pathway Visualization: From Biomarker Discovery to Clinical Application

The journey from initial biomarker screening to its integration into clinical diagnostics and personalized treatment strategies involves a logical, multi-stage pathway. This process, underpinned by high-throughput qPCR and other omics technologies, is critical for advancing cancer management [21].

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains a foundational technology in clinical oncology, providing a unique combination of high analytical sensitivity, rapid turnaround time, and cost-efficiency that makes it uniquely suited for informing therapeutic decision-making at scale [2]. In the context of high-throughput cancer biomarker screening, qPCR enables the detection of clinically actionable biomarkers at increasingly low concentrations while supporting broader mutational profiling to guide precise treatment decisions [2]. This application note details the specific implementations of qPCR across the cancer care continuum, from initial diagnosis through therapy selection and monitoring.

The advantages of qPCR are particularly evident in time-sensitive or resource-constrained settings. Unlike sequencing platforms that can take days to generate and analyze data, qPCR delivers clinically actionable results within hours, which is especially valuable when selecting targeted therapies or enrolling patients into mutation-driven clinical trials [2]. Furthermore, its strong multiplexing capability allows multiple clinically relevant mutations to be detected in a single reaction without compromising sensitivity or speed, making it ideal for oncology applications where actionable targets span several genes and sample material is scarce [2].

Application Note: qPCR for Cancer Diagnosis and Early Detection

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Analysis

Liquid biopsies analyzing ctDNA have transformed cancer diagnosis by providing a minimally invasive method to detect tumor-derived genetic material in blood and other body fluids [22] [23]. qPCR assays can detect cancer-specific mutations and epigenetic alterations in ctDNA with sensitivity sufficient to identify early-stage malignancies. The rapid clearance of ctDNA, with estimated half-lives ranging from minutes up to a few hours, provides a dynamic window into current disease status, though it also presents technical challenges for detection [23].

DNA methylation biomarkers in liquid biopsies offer particular promise for early cancer detection. Methylation patterns often emerge early in tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout tumor evolution, making them ideal biomarker candidates [23]. The inherent stability of the DNA double helix provides additional protection compared to single-stranded nucleic acid-based biomarkers, and methylated DNA appears to have enhanced resistance to degradation during sample collection, storage, and processing [23].

Multiplexed Panels for Comprehensive Screening

Multiplexed qPCR panels exemplify the power of high-throughput applications in cancer diagnostics. For example, in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), multiplexed qPCR panels can simultaneously assess alterations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, and ALK – delivering results faster and using less input material than sequential or panel-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) approaches [2]. Solutions such as Biofidelity's Aspyre Lung Reagents and the AmoyDx Pan Lung Cancer PCR Panel showcase the strong clinical potential of multiplexed qPCR for comprehensive molecular profiling [2].

Table 1: Diagnostic qPCR Biomarkers in Common Cancers

| Cancer Type | Key Biomarkers | Sample Source | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, ALK fusions | Plasma, FFPE | Diagnosis, mutation profiling [2] |

| Colorectal Cancer | DNA Methylation Markers | Stool, Plasma | Early detection, screening [23] |

| Liver Cancer (HCC) | AFP | Serum | Diagnosis, recurrence monitoring [22] |

| Prostate Cancer | PSA | Serum | Screening, diagnosis [22] |

| Bladder Cancer | DNA Methylation Markers | Urine | Non-invasive detection [23] |

Application Note: qPCR for Prognostic Stratification

Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Detection

qPCR enables highly sensitive detection of minimal residual disease following curative-intent treatment. By tracking tumor-specific mutations or methylation patterns in ctDNA, qPCR can identify molecular recurrence weeks or months before clinical or radiographic evidence emerges [23]. This early warning system allows clinicians to initiate interventions sooner, potentially improving outcomes. The quantitative nature of qPCR further enables monitoring of disease burden over time, providing dynamic prognostic information.

Gene Expression Profiling

While ctDNA analysis focuses on genetic and epigenetic alterations, qPCR also facilitates gene expression profiling of tumor tissue. By quantifying expression levels of genes associated with aggressive phenotypes or treatment resistance, qPCR panels can stratify patients according to recurrence risk. This application requires careful normalization to appropriate reference genes and validation of expression thresholds with clinical outcomes [24].

Table 2: Prognostic Biomarkers Detectable by qPCR

| Biomarker Category | Specific Examples | Prognostic Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Circulating Tumor DNA | EGFR mutations, methylation markers | Molecular recurrence, tumor burden [23] |

| Gene Expression Signatures | Oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes | Risk stratification, treatment response [24] |

| MicroRNAs | Various cancer-associated miRNAs | Disease progression, metastasis [22] |

| Cancer/Testis Antigens | CT antigens | Aggressive disease course [22] |

Application Note: qPCR for Therapy Selection

Companion Diagnostic Applications

qPCR serves as the technological foundation for numerous companion diagnostics that match patients with targeted therapies. For example, detection of EGFR mutations in NSCLC determines eligibility for EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, while BRAF V600E identification guides use of BRAF inhibitors in melanoma and other cancers [2]. The rapid turnaround time of qPCR (typically within hours) supports timely treatment decisions without compromising accuracy.

Resistance Mutation Monitoring

During treatment with targeted therapies, tumors often develop resistance mutations that can be detected by qPCR before clinical progression occurs. Serial monitoring of known resistance mechanisms (e.g., EGFR T790M in NSCLC) enables timely adaptation of treatment strategies. qPCR's cost-effectiveness and technical accessibility make it ideal for repeated testing throughout a patient's treatment journey [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ctDNA Extraction and Mutation Analysis from Plasma

Principle: Circulating tumor DNA fragments are extracted from blood plasma and analyzed for cancer-specific mutations using allele-specific qPCR assays.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Blood collection tubes (EDTA or specialized ctDNA tubes)

- Plasma separation reagents

- ctDNA extraction kit

- qPCR master mix optimized for low input DNA

- Mutation-specific primers and probes

- Control templates (wild-type and mutant)

- Centrifuge capable of 16,000 × g

- Quantitative PCR instrument

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and Processing: Collect blood in EDTA tubes. Process within 2 hours of collection by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 minutes to separate plasma. Transfer supernatant to a fresh tube and centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove residual cells [23].

- ctDNA Extraction: Extract ctDNA from plasma using a specialized circulating nucleic acid kit according to manufacturer's instructions. Elute in an appropriate buffer and quantify using a fluorometric method sensitive to low DNA concentrations.

- Assay Preparation: Prepare qPCR reactions containing mutation-specific primers and probes. Include appropriate controls: no-template control, wild-type control, and mutant control at known variant allele frequencies.

- qPCR Amplification: Run reactions under the following conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute

- Data Analysis: Determine Cq values using appropriate baseline and threshold settings. For variant allele frequency calculation, use a standard curve generated from control templates with known mutation percentages [24].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Multiplex qPCR for Cancer Panel Screening

Principle: Simultaneous detection of multiple cancer-associated mutations in a single reaction using a multiplex qPCR approach with target-specific probes differentially labeled with fluorescent reporters.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Multiplex qPCR master mix

- Target-specific primer and probe sets

- DNA template (from tumor tissue, plasma, or other sources)

- 384-well qPCR plates

- High-throughput qPCR instrument with multiple detection channels

Procedure:

- Assay Design: Design primer and probe sets for each target mutation, ensuring similar annealing temperatures and minimal cross-reactivity. Label each probe with a different fluorescent dye compatible with available detection channels.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare multiplex qPCR reactions containing all primer and probe sets. For high-throughput applications, use automated liquid handling systems to dispense reactions into 384-well plates.

- qPCR Amplification:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 50 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute (with fluorescence acquisition)

- Data Analysis: Analyze amplification curves for each fluorescence channel separately. Set thresholds within the exponential phase of amplification where all assays display parallel log-linear phases [24]. Determine Cq values and interpret results based on established cutoffs for each target.

Protocol 3: DNA Methylation Analysis Using Bisulfite Conversion

Principle: Bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils, followed by qPCR with methylation-specific primers to detect promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Bisulfite conversion kit

- Methylation-specific primers

- qPCR master mix

- Converted DNA controls (fully methylated and unmethylated)

Procedure:

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat extracted DNA with bisulfite reagent according to manufacturer's instructions. This process deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged.

- Purification: Purify bisulfite-converted DNA and elute in an appropriate buffer.

- Methylation-Specific qPCR: Set up reactions with primers specifically designed to amplify either the methylated or unmethylated sequence. Always run both reactions for each sample.

- Amplification:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing: Primer-specific temperature for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds

- Data Interpretation: Calculate the percentage of methylated alleles using the ΔΔCq method with reference to standards of known methylation percentage [24].

Workflow Visualization

High-Throughput qPCR Clinical Workflow: This diagram illustrates the standardized workflow for processing samples in cancer biomarker screening, from sample collection through clinical reporting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for High-Throughput qPCR in Oncology Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Resistant Master Mix | Amplification of challenging clinical samples | Engineered polymerases that tolerate PCR inhibitors in plasma, whole blood, or FFPE-derived nucleic acids [2] |

| Multiplex qPCR Reagents | Simultaneous detection of multiple targets | Advanced master mixes and probe systems enabling detection of several mutations in a single reaction [2] |

| Ambient-Stable Formulations | Decentralized testing applications | Lyophilized reagents that maintain stability without cold chain storage [2] |

| Mutation-Specific Assays | Detection of low-frequency variants | Optimized primers and probes capable of detecting variants at <0.1% variant allele frequency [2] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | DNA methylation analysis | Efficient conversion of unmethylated cytosines while preserving methylated sites [23] |

| Reference Gene Assays | Data normalization | Consistently expressed genes for reliable quantification across sample types [24] |

Data Analysis and Quality Control

Baseline and Threshold Setting

Accurate Cq determination requires proper baseline correction and threshold setting. The baseline should be set using early cycles (typically cycles 5-15) where amplification remains linear, avoiding the initial cycles (1-5) which may contain reaction stabilization artifacts [24]. The threshold should be set:

- Sufficiently above background fluorescence to avoid premature threshold crossing

- Within the logarithmic phase of amplification, before plateau effects begin

- At a position where all amplification curves display parallel log-linear phases [24]

Quantitative Analysis Methods

Standard Curve Quantification: Using a dilution series of standards with known concentrations, this method provides absolute quantification of target molecules. The Cq values of standards are plotted against the logarithm of their concentrations to generate a standard curve, from which unknown sample concentrations can be interpolated [24].

Comparative Cq Method (ΔΔCq): This relative quantification approach uses the difference in Cq values between target genes and reference genes compared to a control sample. The formula 2^(-ΔΔCq) provides the relative expression fold change, assuming amplification efficiencies are near 100% [25] [24].

Efficiency-Corrected Model: For more precise quantification when amplification efficiencies differ from 100%, this model incorporates actual PCR efficiencies (determined from standard curves) into the relative quantification calculation, providing more accurate fold-change measurements [24].

Quality Assessment Metrics

Amplification Efficiency: Calculated from standard curves using the formula E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1, with ideal values between 90-110% [24].

Linearity (R²): The correlation coefficient of the standard curve, with values >0.985 indicating acceptable linearity.

Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest variant allele frequency consistently detectable, typically <0.1% for optimized oncology assays [2].

qPCR maintains a crucial position in clinical oncology workflows due to its unique combination of sensitivity, speed, and practicality. While emerging technologies like next-generation sequencing provide broader genomic coverage, qPCR offers unmatched efficiency for targeted detection of clinically validated biomarkers across the cancer care continuum. The ongoing development of more robust reagents, enhanced multiplexing capabilities, and stable formulations ensures that qPCR will remain an indispensable tool for high-throughput cancer biomarker screening in both centralized and decentralized settings. As the field moves toward earlier detection and more personalized treatment approaches, qPCR's role in providing rapid, cost-effective, and clinically actionable molecular information continues to expand.

Implementing High-Throughput qPCR Workflows: From Sample to Data

High-throughput quantitative polymerase chain reaction (HT-qPCR) represents a cornerstone technology in modern oncology research, enabling the rapid, sensitive, and parallelized detection of nucleic acid biomarkers critical for early cancer detection and personalized medicine. This platform overview examines the core architectures—96-well systems, microfluidics, and emerging nanodispenser technologies—that empower researchers to screen large patient cohorts and multiplexed biomarker panels with high efficiency and reproducibility. The transition from conventional qPCR to HT formats addresses the pressing need in cancer diagnostics to process numerous samples while conserving precious reagents and clinical material, such as cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from liquid biopsies [26]. In the context of cancer biomarker discovery, HT-qPCR facilitates the validation of candidate markers, including circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), microRNAs (miRNAs), and DNA methylation patterns, across diverse sample types from tissue biopsies to liquid biopsies [22] [23]. The compatibility of these platforms with standardized well plates and automated liquid handling makes them indispensable for translational research aimed at bringing novel biomarkers from concept to clinic.

HT-qPCR Platform Architectures and Technical Specifications

96-Well Plate Systems

The standard 96-well plate format remains the most widely adopted platform for HT-qPCR due to its direct compatibility with established laboratory automation, thermal cyclers, and liquid handling robotics. This format strikes a balance between throughput, reagent consumption, and accessibility, making it a versatile choice for various applications in cancer research.

Key Applications:

- Biomarker Validation: Ideal for profiling the expression of a focused panel of candidate genes (e.g., oncogenes, tumor suppressors, miRNAs) across many patient samples [27].

- Mutation Screening: Multiplexed qPCR panels can simultaneously assess clinically actionable mutations in genes such as EGFR, KRAS, and BRAF from limited samples like fine-needle aspirates or liquid biopsies [26].

- Data Analysis: The R/Bioconductor package

HTqPCRis specifically designed to process, normalize, and perform statistical analysis on the large datasets generated from 96-well (and higher density) formats, handling cycle threshold (Ct) values, quality control, and differential expression [27].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of 96-well HT-qPCR Platforms

| Feature | Specification | Utility in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | 96 reactions per run | Efficient for screening 10s-100s of samples against a defined biomarker panel |

| Reaction Volume | Typically 10-25 µL | Balances sensitivity with reagent cost |

| Multiplexing Capability | Moderate (typically 2-4 plex) | Suitable for simultaneous detection of a few key mutations or expression targets |

| Data Analysis | Compatible with specialized software (e.g., HTqPCR package for R) |

Enables quality control, normalization, and statistical testing across multiple conditions [27] |

| Cost per Sample | Low ($50-$200 per test) [26] | Cost-effective for large-scale screening and routine diagnostics |

Microfluidic qPCR Systems

Microfluidic HT-qPCR systems represent a significant advancement in miniaturization and integration. These systems use microfabricated fluidic channels and chambers to partition reactions at nanoliter scales, dramatically increasing throughput while reducing sample and reagent consumption. A prominent example is the TaqMan Low Density Array (TLDA) cards, which are pre-configured with assay primers and probes [27].

Key Applications:

- High-Density Profiling: Enables the parallel analysis of hundreds of targets (e.g., a comprehensive miRNA signature or a large panel of methylation markers) from a single, limited patient sample [27] [23].

- Liquid Biopsy Analysis: Ideal for analyzing ctDNA or other rare nucleic acid species from liquid biopsies where input material is scarce [23] [26].

- Integrated Perfusion Culture: Novel systems like the High-Throughput microfluidics-enabled uninterrupted perfusion system (HT-μUPS) integrate microfluidic perfusion with 96-well plates, allowing for long-term dynamic cell culture and chronic all-optical electrophysiology. This is particularly useful for maintaining highly metabolic cells like patient-derived cardiomyocytes or studying cell responses under controlled conditions, which can support research into cancer cell behavior and cardiotoxicity of chemotherapeutics [28] [29].

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Microfluidic HT-qPCR Platforms

| Feature | Specification | Utility in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | 384 wells or more per run | High-density profiling of hundreds of targets from a single sample |

| Reaction Volume | Nanoliter scale (e.g., 1-10 nL) | Drastically reduces reagent costs and conserves precious samples (e.g., liquid biopsies) |

| Multiplexing Capability | High (dozens to hundreds of pre-configured assays) | Comprehensive screening of biomarker panels for molecular stratification |

| System Integration | Can be coupled with perfusion systems for cell culture [28] | Allows for longitudinal study of cell responses and functional assays |

| Shear Stress Management | Designed to keep shear stress low (e.g., <2.4 dyn/cm² for excitable cells) [28] | Maintains viability of sensitive cell cultures for downstream analysis |

Nanodispenser Systems

Nanodispenser systems focus on the front-end of the HT-qPCR workflow: the precise, high-speed dispensing of nanoliter-scale reaction volumes into high-density well plates (e.g., 384- or 1536-well formats). These systems are critical for achieving the miniaturization and automation that define true high-throughput screening.

Key Applications:

- Ultra-High-Throughput Screening: Essential for large-scale drug discovery campaigns, functional genomics screens, and population-scale biomarker validation studies.

- Reagent Miniaturization: Enables the setup of thousands of qPCR reactions with significant savings on costly primers, probes, and master mixes.

- Workflow Automation: Can be integrated with robotic plate handlers to create fully automated, walk-away systems for processing thousands of samples per day.

Table 3: Key Characteristics of Systems with Nanodispenser Technology

| Feature | Specification | Utility in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Dispensing Volume | Nanoliter to picoliter range | Enables reaction setup in 384- and 1536-well plates, minimizing costs |

| Dispensing Precision | High accuracy and reproducibility | Critical for assay robustness and reliable quantification of low-abundance targets |

| Throughput | Thousands of wells per hour | Facilitates population-scale studies and large compound screens |

| Automation Compatibility | Designed for integration into robotic workstations | Supports complex, multi-step workflows with minimal manual intervention |

Experimental Protocols for Cancer Biomarker Applications

Protocol: Multiplexed Mutation Detection in Liquid Biopsies using 96-well qPCR

This protocol is designed for detecting somatic mutations in ctDNA from plasma, relevant for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and other solid tumors [26].

1. Sample Preparation and Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Collect whole blood in EDTA or cell-stabilizing tubes. Process within 2 hours to prevent lysis of blood cells.

- Isolate plasma by double centrifugation (e.g., 1,600 x g for 10 min, then 16,000 x g for 10 min).

- Extract cfDNA from 1-5 mL of plasma using a silica-membrane or bead-based kit optimized for low-concentration samples. Elute in a low-EDTA TE buffer or nuclease-free water.

- Quantify cfDNA using a fluorescence-based method sensitive to low DNA concentrations (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay).

2. Assay Design and qPCR Setup

- Primers/Probes: Use a validated multiplex qPCR panel targeting key mutations (e.g., in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF). Assays should be designed for high specificity to discriminate single-nucleotide variants. Use dual-labeled probes (e.g., TaqMan) with distinct fluorophores for each target.

- Reaction Mix (10 µL final volume in a 96-well plate):

- 5 µL of 2x Multiplex qPCR Master Mix (inhibitor-resistant, with antibody-mediated hot-start) [26]

- 1 µL of primer-probe mix (pre-optimized concentrations)

- 2-4 µL of cfDNA template (up to 50 ng total)

- Nuclease-free water to 10 µL

- Sealing and Centrifugation: Seal the plate with an optical adhesive film and centrifuge briefly to collect contents at the bottom of the wells.

3. qPCR Amplification and Data Acquisition

- Run the plate on a real-time PCR instrument with multicolor detection capability. Use the following typical cycling conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes (polymerase activation)

- 45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute (acquire fluorescence)

- Controls: Include no-template controls (NTCs) for each assay, wild-type control DNA, and positive controls for each mutation if available.

4. Data Analysis with HTqPCR Package in R

- Data Input: Import raw Ct value exports from the qPCR instrument software into the R environment using the

HTqPCRpackage [27]. - Quality Control (QC):

- Use

plotCtDensityandplotCtBoxesto assess the distribution and quality of Ct values across samples. - Flag Ct values above a reliable detection threshold (e.g., Ct > 35) as "Unreliable".

- Use

- Normalization: Normalize data using the

normalizeCtDatafunction. The ΔΔCt method is common, using one or more reference genes (e.g., β-actin) that are stably expressed across samples. Alternatively, use quantile normalization if stable reference genes are not available. - Calling Mutations: Calculate ΔCt values (Ct[target] - Ct[reference]). A ΔCt value beyond a pre-defined threshold (established from wild-type controls) indicates the presence of a mutation.

Diagram 1: Workflow for multiplexed mutation detection in liquid biopsies.

Protocol: DNA Methylation Analysis via Bisulfite Conversion and qPCR

DNA methylation is a stable epigenetic biomarker often altered in cancer. This protocol outlines its detection using bisulfite conversion followed by qPCR, which is highly relevant for analyzing promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes [23].

1. Bisulfite Conversion of cfDNA

- Use 10-50 ng of input cfDNA.

- Treat DNA with sodium bisulfite using a commercial kit. This process converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged.

- Purify the bisulfite-converted DNA and elute in a small volume.

2. qPCR Assay for Methylated Alleles

- Assay Design: Design primers and probes that are specific to the bisulfite-converted, methylated sequence. The probe typically spans several CpG sites to maximize specificity.

- Reaction Setup:

- Use a qPCR master mix optimized for bisulfite-converted DNA, which is often more fragmented and of lower quality.

- Set up two parallel reactions for each sample: one with primers/probes for the methylated allele and one for a reference gene (to control for DNA input).

- Amplification: Run on a real-time PCR instrument with standard cycling conditions. Methylation-specific amplification will typically yield a lower Ct value if the methylated allele is present.

3. Data Analysis and Quantification

- Calculate the ΔCt value: Ct(methylated assay) - Ct(reference assay).

- The level of methylation can be expressed as 2^(-ΔCt). For absolute quantification, compare to a standard curve of known methylated DNA.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of HT-qPCR in cancer research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials designed to ensure sensitivity, specificity, and robustness, particularly when working with challenging clinical samples.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for HT-qPCR in Oncology

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Characteristics for Cancer Apps |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Resistant Master Mix | Amplification of nucleic acids | Contains engineered polymerases and buffers to tolerate PCR inhibitors common in clinical samples (e.g., from plasma, FFPE tissue) [26] |

| Multiplex qPCR Assays | Simultaneous detection of multiple targets | Pre-optimized primer-probe sets for mutation panels (e.g., EGFR, KRAS) or biomarker signatures; different fluorophores enable multiplexing [26] |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of cell-free DNA from liquid biopsies | Optimized for low-abundance DNA from large volume plasma/serum inputs; maximizes recovery and minimizes contamination |

| Ambient-Stable/Lyophilized Reagents | Ready-to-use assay formats | Reduces cold-chain dependency, ideal for decentralized testing; simplifies workflow and improves reproducibility [26] |

| Standard 96-/384-Well Plates | Reaction vessel for HT-qPCR | Manufactured to high standards for optimal thermal conductivity and low well-to-well cross-talk; compatible with automation |

| Microfluidic Cartridges (e.g., TLDA) | Integrated, high-density reaction vessel | Pre-configured with assays for specific cancer pathways; minimizes pipetting steps and reduces risk of contamination [27] |

The integrated use of 96-well, microfluidic, and nanodispenser HT-qPCR platforms provides a powerful, scalable toolkit for advancing cancer biomarker research. From validating targeted mutation panels in a standard 96-well format to performing ultra-high-throughput methylation profiling on microfluidic chips, these technologies enable researchers to navigate the complexities of cancer genomics with precision and efficiency. The continued evolution of associated reagents—such as inhibitor-resistant master mixes and ambient-stable formulations—further enhances the reliability of these platforms for analyzing real-world clinical specimens like liquid biopsies. By leveraging the detailed protocols and tools outlined in this overview, researchers and drug development professionals can robustly employ HT-qPCR to accelerate the discovery and translation of molecular diagnostics into clinical practice, ultimately contributing to earlier cancer detection and personalized therapeutic strategies.

The rising global cancer burden, with new cases expected to exceed 35 million annually by 2050, places unprecedented demands on cancer diagnostics and biomarker development [23]. In this context, high-throughput quantitative PCR (qPCR) has emerged as a cornerstone technology for sensitive and specific detection of cancer biomarkers in liquid biopsies, including circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), microRNAs, and other RNA species. The need to screen large patient cohorts for biomarker discovery and validation, combined with increasing reagent costs and limited sample availability, has driven laboratories toward automation and miniaturization strategies. These approaches enable researchers to maintain high data quality while significantly reducing per-reaction costs and increasing experimental throughput, thereby accelerating the pace of cancer research and precision oncology initiatives.

Miniaturization in qPCR refers to the systematic reduction of reaction volumes from traditional 20-50 µL scales down to 1-10 µL volumes using 384-well plates or higher-density formats. This paradigm shift, when coupled with automated liquid handling systems, allows researchers to achieve substantial cost savings while maximizing output from precious clinical samples. The integration of these approaches is particularly valuable in cancer biomarker research, where sample availability is often limited and the need for robust, reproducible results is paramount for clinical translation.

Quantitative Benefits: Cost and Resource Optimization

The economic advantages of miniaturization in high-throughput qPCR are substantial and directly impact research efficiency. A detailed cost analysis reveals significant savings in reagent consumption and associated expenses when transitioning from 96-well to 384-well formats.

Table 1: Cost Comparison Between 96-Well and 384-Well qPCR Formats

| Parameter | 96-Well Format | 384-Well Format | Savings with 384-Well |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Volume | 20 µL | 10 µL | 50% reduction in reagents |

| Reactions per Plate | 96 | 384 | 4x increase in throughput |

| Cost per Reaction | 0.72 EUR / 0.89 USD | 0.36 EUR / 0.44 USD | 50% reduction per data point |

| Cost per Full Plate | 50 EUR / 85.78 USD | 60 EUR / 167.86 USD | Higher total but lower per reaction |

| Plates to Break Even on Instrument Cost | - | 77 plates (~29,600 reactions) | Initial investment recouped rapidly at scale [30] |

Beyond direct reagent costs, miniaturization preserves valuable clinical samples. A 2.5-fold difference in sample input exists between 20 µL (typically 5 µL sample) and 10 µL (typically 2 µL sample) reactions, with only a minimal impact on Cq values (approximately 0.83 cycles higher in 10 µL reactions) [30]. This allows researchers to perform more replicates, include additional controls, or analyze more biomarkers from the same sample volume, thereby increasing the statistical power and reliability of cancer biomarker studies.

For specialized cell models such as iPSC-derived cells, which can cost over $1,000 per vial of 2 million cells, miniaturization from 96-well to 384-well format reduces cell requirements from approximately 23 million to 4.6 million cells for a 3,000 data-point screen, representing substantial cost savings of approximately $6,900 excluding additional savings on specialized culture media and growth factors [31].

Implementation Strategies: Methodologies and Workflows

Automated Liquid Handling and Miniaturization Protocols

Successful implementation of miniaturized qPCR workflows requires specialized equipment and optimized protocols. Automated liquid handling systems with positive displacement technology enable accurate and precise transfer of volumes from 500 nL to 5 µL, eliminating cross-contamination through pre-sterilized disposable pipettes and maximizing efficiency through rapid plate-to-plate pipetting [32]. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for miniaturized qPCR setup for cancer biomarker analysis:

Protocol: Miniaturized qPCR Setup for Cancer Biomarker Analysis

Reagents and Equipment:

- Automated liquid handler (e.g., mosquito HV genomics)

- 384-well qPCR plates with white wells and ultra-clear seals

- Low-volume qPCR master mix (e.g., biotechrabbit Capital qPCR Mix)

- Template DNA/cDNA (minimum 2 µL per 10 µL reaction)

- Target-specific primers/probes

- qPCR instrument with 384-well block (e.g., qTOWERiris)

Procedure:

- Reaction Plate Preparation: Program the automated liquid handler to dispense 8 µL of master mix into each well of a 384-well plate.

- Template Addition: Add 2 µL of template DNA/cDNA to each well using the automated system.

- Sealing and Centrifugation: Seal the plate with optical-quality clear seals and centrifuge briefly (1000 × g, 1 minute) to collect reaction mixture at the bottom of wells and eliminate bubbles.

- qPCR Amplification: Run the reaction using the following optimized thermocycling conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds (for genomic DNA)

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 5-15 seconds (shorter for smaller templates)

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute (combined shuttle PCR)

- Melt curve analysis: As recommended by instrument manufacturer [33]

Critical Optimization Steps:

- Primer Design: Design primers with 40-60% GC content, length of 28 bp or larger, and Tm between 58-65°C with less than 4°C difference between forward and reverse primers.

- Probe Design: For probe-based detection, design probes with Tm approximately 10°C higher than primers, length between 9-40 bp, and avoid G repeats, especially at the 5' end.

- Evaporation Control: Use proper sealing methods and consider plate designs with evaporation barriers to prevent edge effects, particularly critical in low-volume reactions [31] [33].

Integration with Cancer Biomarker Applications

In cancer biomarker research, miniaturized qPCR workflows can be applied to various liquid biopsy analytes. For RNA biomarkers, a two-step RT-qPCR approach is recommended when analyzing multiple transcripts from a single sample. This involves reverse transcription primed with either oligo d(T)16 or random primers, followed by miniaturized qPCR analysis of specific targets [17]. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing circulating miRNAs, lncRNAs, and other RNA species identified as promising cancer biomarkers in recent studies [8].

For DNA methylation-based cancer biomarkers, which demonstrate enhanced stability in liquid biopsies, targeted qPCR approaches following bisulfite conversion enable sensitive detection of hypermethylated promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes. The minimal sample requirements of miniaturized workflows are especially beneficial for these applications, as they allow for parallel assessment of multiple methylation markers from limited liquid biopsy samples [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Miniaturized qPCR in Cancer Biomarker Research

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handler | Precise nanoliter-scale dispensing for 384-well plate setup | Positive displacement technology (e.g., mosquito HV) minimizes cross-contamination; enables 10x miniaturization of NGS library prep [32] |

| Low-Volume qPCR Master Mix | Optimized enzyme and buffer system for 10 µL reactions | Antibody-mediated hot-start polymerases eliminate need for 10-15 minute activation step [33] |

| 384-Well qPCR Plates | Optical reaction vessels with minimal well-to-well variability | White wells reduce light distortion; ultra-clear caps optimize signal detection [33] |

| Target-Specific Assays | Pre-designed primer/probe sets for cancer biomarkers | Commercial assays available for known biomarkers; custom designs needed for novel targets; ensure 90-110% amplification efficiency [17] |

| Quality Control Tools | RNA/DNA integrity assessment and quantification | Bioanalyzer systems (e.g., Implen N80) and spectrophotometers essential for input quality control [33] |

Workflow Integration and Pathway Analysis

The implementation of automated, miniaturized qPCR requires careful planning of the complete workflow from sample collection to data analysis. The following diagram illustrates the integrated process for cancer biomarker screening:

The successful implementation of this workflow requires careful consideration of the logical relationships between key experimental parameters. The following diagram illustrates the optimization pathway for miniaturized qPCR experiments:

Automation and miniaturization of qPCR workflows represent a transformative approach in cancer biomarker research, addressing the dual challenges of increasing throughput and reducing costs without compromising data quality. The strategic implementation of 384-well formats, coupled with automated liquid handling systems, enables researchers to achieve significant reagent savings while maximizing the utility of precious liquid biopsy samples. As cancer biomarker discovery evolves toward multi-analyte panels and larger validation cohorts, these approaches will become increasingly essential for accelerating the development of next-generation cancer diagnostics and personalized treatment strategies. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide a foundation for laboratories seeking to implement these efficient workflows in their cancer research programs.

The shift toward personalized oncology has made the molecular profiling of tumors a prerequisite for effective treatment. Oncogenic drivers such as EGFR, KRAS, and BRAF are critical biomarkers that predict response to targeted therapies, particularly monoclonal antibodies against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and small molecule inhibitors [34] [35]. For instance, KRAS mutations are well-established negative predictors of response to anti-EGFR therapies in colorectal cancer (CRC), as they lead to constitutive activation of downstream signaling pathways, rendering EGFR inhibitors ineffective [34] [35]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and other regulatory bodies therefore recommend mandatory testing of these biomarkers before initiating treatment [34] [35]. This creates a pressing need for diagnostic methods that are not only accurate and sensitive but also fast, cost-effective, and capable of maximizing information output from often limited patient samples. High-throughput quantitative PCR (qPCR) and its advanced derivatives have emerged as powerful tools to meet this need, enabling the simultaneous detection of multiple actionable mutations in a single, streamlined assay [2] [36].

Multiplex Assay Design Strategy

Core Principles for Multiplexing Oncogenic Drivers