Harnessing 3D-QSAR for Anticancer Drug Discovery: A Computational Guide for Natural Product Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the foundational principles and advanced applications of Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling in the discovery and optimization of natural product-based anticancer compounds.

Harnessing 3D-QSAR for Anticancer Drug Discovery: A Computational Guide for Natural Product Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the foundational principles and advanced applications of Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling in the discovery and optimization of natural product-based anticancer compounds. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the critical methodology from pharmacophore generation and molecular field analysis to model validation and troubleshooting. The content further details the integration of 3D-QSAR with complementary computational techniques like molecular docking and dynamics simulations, supported by case studies on compounds such as shikonin and maslinic acid derivatives. Finally, it outlines the pathway from in silico predictions to experimental validation, discussing future directions and the transformative potential of these methodologies in accelerating oncology drug development.

From Plant to Prediction: Unveiling the Principles of 3D-QSAR for Natural Anticancer Leads

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, providing a predictive framework to correlate chemical structure with biological effect. While traditional 2D-QSAR methods utilize numerical descriptors that treat molecules as flat structures—such as logP for hydrophobicity or molecular weight—they fundamentally lack spatial information about how these molecules interact in three-dimensional biological systems [1]. Three-dimensional QSAR (3D-QSAR) addresses this critical limitation by incorporating the molecular shape, conformation, and interaction potentials into the modeling process [1]. This paradigm shift is particularly valuable in the context of natural product anticancer research, where complex molecular architectures interact with biological targets through precise three-dimensional complementarity. The transition from 2D to 3D descriptors enables researchers to visualize and quantify the spatial requirements for biological activity, transforming the drug optimization process from molecular feature counting to rational, structure-based design.

Theoretical Foundations: Core Concepts of 3D-QSAR

Molecular Descriptors in 3D Space

In 3D-QSAR, molecules are represented not by global molecular properties but by detailed spatial descriptors derived from their three-dimensional structures. The most established approaches calculate interaction energies between the molecule and chemical probes positioned at numerous points within a grid surrounding the molecular structure [1]. These interaction fields capture the essential steric (shape-based) and electrostatic (charge-based) properties that govern molecular recognition and binding. Steric fields map regions where molecular bulk may create favorable van der Waals contacts or unfavorable clashes with the target. Electrostatic fields identify areas of positive or negative potential that can form favorable charge-charge interactions or repulsions with the biological target [1]. Some advanced methods like Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extend this concept to include additional fields such as hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen-bonding capabilities, providing a more comprehensive description of the molecular interaction profile [1].

The Critical Role of Molecular Alignment

A fundamental requirement of classical 3D-QSAR methods is the correct spatial alignment of all molecules in the dataset [1]. This process assumes that all compounds share a similar binding mode to their common biological target. Alignment typically involves superimposing molecules based on either a common scaffold (using approaches like Bemis-Murcko scaffolding) or the maximum common substructure (MCS) shared among the dataset compounds [1]. The quality of this molecular alignment directly impacts the reliability and predictive power of the resulting 3D-QSAR model, as misaligned molecules will generate inconsistent field descriptors that do not correspond to equivalent positions in three-dimensional space. This alignment dependency represents both a challenge and an opportunity—while it requires careful conformational analysis and bioactive pose estimation, it also ensures that the resulting model reflects the actual spatial relationship between molecular features and biological activity.

Methodological Workflow: Building a 3D-QSAR Model

Data Preparation and Molecular Modeling

The construction of a reliable 3D-QSAR model begins with the assembly of a high-quality dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀ or Kᵢ values) measured under uniform conditions [1]. For natural product research, this typically involves structurally related analogs derived from a common scaffold. These 2D structures are converted into three-dimensional coordinates using cheminformatics tools like RDKit or Sybyl, followed by geometry optimization to ensure they adopt realistic, low-energy conformations [1]. Optimization may employ molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., UFF) or more accurate quantum mechanical methods, with the selected conformation critically influencing subsequent alignment and descriptor calculation.

Field Calculation and Statistical Modeling

Following alignment, steric and electrostatic field descriptors are calculated using a probe atom at regular grid points surrounding the molecules [1]. In Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), a carbon atom with a +1 charge serves as this probe, calculating steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) potentials at each grid point [1]. The resulting data matrix, comprising thousands of field values for each compound, is analyzed using Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to identify the field components most strongly correlated with biological activity [1]. PLS effectively handles the high dimensionality and collinearity of 3D-field data by projecting it into a reduced space of latent variables that maximize the covariance with the activity data.

Table 1: Comparison of Major 3D-QSAR Methodologies

| Method | Field Types | Alignment Dependency | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA [1] | Steric, Electrostatic | High | Established methodology, intuitive interpretation | Lead optimization for congeneric series |

| CoMSIA [1] | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-bond Donor/Acceptor | Moderate | Smoother fields, additional field types, more tolerant to alignment variations | Diverse compound sets, natural product analogs |

| Similarity-Based [2] | Shape, Electrostatic | Low | Consensus predictions, machine learning integration, domain of applicability | Large virtual screening, scaffold hopping |

Model Validation and Interpretation

Robust validation is essential to ensure a 3D-QSAR model possesses genuine predictive power for novel compounds. Internal validation techniques like leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation measure a model's stability, producing a Q² value that estimates predictive ability [1]. External validation using a completely separate test set provides the most reliable assessment of a model's utility in real-world applications [1]. A successfully validated model is interpreted through 3D contour maps that visually identify specific spatial regions where molecular properties enhance or diminish biological activity. These maps directly guide chemical modification: green steric contours indicate regions where bulky groups increase activity, while yellow contours flag unfavorable steric interactions [1]. Similarly, blue electrostatic contours mark regions favoring positive charges, with red contours preferring negative charges [1].

Application in Anticancer Natural Product Research

Case Study: Naphthoquinone Derivatives Against Colorectal Cancer

A compelling application of 3D-QSAR in natural product anticancer research involves naphthoquinone derivatives evaluated against HT-29 colorectal cancer cells [3]. Researchers synthesized 36 naphthoquinone analogs and tested their anti-proliferative activity, identifying 15 active compounds (IC₅₀ = 1.73-18.11 μM) [3]. The subsequent 3D-QSAR study employing Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) generated a highly reliable model (r² = 0.99, q² = 0.625) that correlated structural features with cytotoxic potency [3]. The model revealed that tricyclic naphtho[2,3-b]furan-4,9-dione and naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-dione systems substituted at the 2-position with electron-withdrawing groups demonstrated enhanced cytotoxicity [3]. This 3D-QSAR analysis enabled the rational design of five novel proposed compounds with predicted two-fold higher anti-proliferative activity than the most potent compound identified in the initial series [3].

Case Study: Nitrogen-Mustard Derivatives for Osteosarcoma

Another innovative application involves dipeptide-alkylated nitrogen-mustard compounds with anti-osteosarcoma activity [4]. In this research, both 2D- and 3D-QSAR models were established to predict the anti-tumor activity of these derivatives [4]. The 3D-QSAR study utilized the CoMSIA method, which incorporated steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields to generate a comprehensive model [4]. By analyzing the contour plots from this model, researchers designed 200 novel compounds, with one particular candidate (I1.10) demonstrating both high predicted anti-tumor activity and favorable molecular docking characteristics [4]. This integrated approach exemplifies how 3D-QSAR can guide the optimization of natural product-derived chemotherapeutic agents against challenging malignancies like osteosarcoma.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for 3D-QSAR Model Development

| Stage | Key Procedures | Software Tools | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset Preparation | Collect uniform activity data (IC₅₀); Curate structurally related compounds; Divide into training/test sets | Manual curation; ChemDraw | Experimentally consistent IC₅₀ values; Structural diversity with common scaffold; ~80/20 training/test split |

| 3D Structure Generation | Convert 2D to 3D coordinates; Geometry optimization; Conformational analysis | RDKit; Sybyl; HyperChem | Force field selection (MM+, UFF, AM1, PM3); Convergence criteria (RMS gradient ≤0.01) |

| Molecular Alignment | Identify common scaffold; Superimpose molecules; Verify bioactive conformation | Maximum Common Substructure (MCS); Bemis-Murcko scaffolds | Alignment hypothesis; Template selection; Consensus scoring |

| Descriptor Calculation | Generate interaction fields; Place grid around molecules; Calculate steric/electrostatic potentials | CoMFA; CoMSIA | Grid spacing (1.0-2.0Å); Probe atom type; Field type selection |

| Model Building | Perform PLS regression; Select optimal components; Avoid overfitting | CODESSA; SAMFA | Cross-validation; Component significance; Statistical significance (q², r²) |

| Validation & Interpretation | External test set prediction; Generate contour maps; Design new analogs | Custom visualization; Docking software | Predictive r²; Contour map analysis; Synthetic feasibility |

Advanced Approaches and Future Directions

Integration with Machine Learning and AI

Modern 3D-QSAR implementations increasingly incorporate machine learning algorithms and artificial intelligence to enhance predictive performance and interpretability. Recent approaches utilize descriptors based on 3D molecular shape and electrostatic similarity tools, with predictions generated as a consensus of multiple models to improve robustness [2]. Studies have demonstrated successful applications of Support Vector Regression (SVR), Categorical Boosting Regression (CatBoost), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Backpropagation Artificial Neural Networks (BPANN) for 3D-QSAR modeling [5]. These methods can handle the high-dimensional nature of 3D-field data while providing insights into complex structure-activity relationships through interpretation tools like SHAP analysis [5]. The integration of deep learning with traditional 3D-QSAR represents a promising frontier for enhancing the anticancer potential of natural products [6].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Platforms | 3D-QSAR.com [7]; OpenEye's 3D-QSAR [2] | Web-based and standalone platforms for developing ligand-based and structure-based 3D-QSAR models | Academic and industrial drug discovery projects |

| Molecular Modeling | RDKit; Sybyl; HyperChem [4] [1] | 2D to 3D structure conversion; geometry optimization; conformational analysis | Initial structure preparation and optimization |

| Descriptor Calculation | CoMFA; CoMSIA; ROCS and EON [1] [2] | Calculate steric, electrostatic, and similarity-based descriptors from aligned molecules | Field-based QSAR analysis; Shape-based similarity screening |

| Statistical Analysis | CODESSA [4]; PLS algorithms [1] | Perform partial least squares regression; variable selection; model optimization | Building and optimizing the QSAR model |

| Validation Tools | Cross-validation scripts; External test set validation [1] | Assess model predictivity; determine domain of applicability | Model validation and performance assessment |

The evolution from traditional 2D-QSAR to three-dimensional methodologies represents a fundamental advancement in computational drug discovery, particularly for the complex structural landscape of natural product anticancer research. By incorporating spatial molecular features—steric bulk, electrostatic potentials, hydrogen-bonding capabilities, and hydrophobic character—3D-QSAR models provide medicinal chemists with visually interpretable guidance for rational compound optimization. The integration of these approaches with modern machine learning algorithms and the continued development of user-friendly computational platforms will further enhance their utility in the ongoing challenge of anticancer drug development. As demonstrated in successful applications against colorectal cancer and osteosarcoma, 3D-QSAR serves as a powerful bridge between structural information and biological activity, accelerating the transformation of natural product scaffolds into promising therapeutic candidates.

Why Natural Products? Exploring a Rich Source of Anticancer Scaffolds

Natural products (NPs) and their derivatives have been, and continue to be, an indispensable source of innovative anticancer therapeutics. Historically, approximately 60% of all cancer drugs are derived from natural products, a statistic that underscores their profound impact on oncology [8]. Iconic examples include the Vinca alkaloids (vincristine and vinblastine), isolated from the Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus), which have been fundamental in managing leukemia and Hodgkin's disease [9]. The significance of NPs extends into the modern era; from 1981 to the present, 79 out of 99 small molecule anticancer drugs are natural product-based or inspired [10]. This enduring utility stems from the unique biological relevance of NPs. As a result of co-evolution with biological targets over millennia, natural products possess complex chemical structures and privileged scaffolds that are pre-validated for biological interaction, making them exceptionally effective at modulating a wide range of targets, including many considered "challenging" for synthetic, drug-like libraries [11] [10].

In the contemporary drug discovery landscape, computational methods are pivotal for harnessing the potential of NPs. Among these, three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has emerged as a powerful ligand-based drug design approach. It allows researchers to quantitatively correlate the three-dimensional spatial and electronic fields of natural compounds with their biological activity. This technique is particularly valuable for optimizing lead compounds derived from NPs, guiding the rational design of more potent and selective anticancer agents by pinpointing the critical steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic features necessary for target binding [12] [13] [14]. This whitepaper explores the rationale behind using natural products as a rich source of anticancer scaffolds and examines the integral role of 3D-QSAR methodologies in translating these natural templates into promising therapeutic candidates.

The Chemical and Biological Rationale for Natural Products

Accessing Unexplored Chemical Space

A primary advantage of natural products lies in their ability to access regions of "biologically relevant chemical space" that are largely untapped by conventional synthetic libraries. An analysis of the human druggable genome reveals a stark concentration of existing drugs on a narrow set of targets; approximately 50% of all drugs target just four protein classes [11]. It is estimated that only 10-14% of proteins encoded by the human genome are 'druggable' using existing drug-like molecules [11]. This limitation exists because synthetic libraries are often biased towards structures with favorable synthetic accessibility and drug-like properties, as defined by rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five.

Natural products, by contrast, exhibit a much broader diversity in their structural and physicochemical properties. A comparative principal component analysis of top-selling drugs, drug-like synthetic compounds, and natural products reveals that NPs generally cluster in a distinct and wider area of chemical space. They often possess higher molecular polarity, increased stereochemical complexity, and fewer aromatic rings compared to their synthetic counterparts [11]. It is estimated that 83% of natural product scaffolds with ≤11 heavy atoms are absent from commercially available screening collections [11]. This vast underrepresented structural diversity makes NPs ideal for addressing biologically challenging targets such as protein-protein interactions (PPIs), which often feature flat, extensive binding interfaces that are difficult for small, synthetic molecules to modulate effectively [11] [10].

Intrinsic Bioactivity and Privileged Scaffolds

The inherent bioactivity of many natural products is not accidental. These molecules have evolved over billions of years to interact precisely with biological macromolecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids, serving as ligands, signal transducers, or defense mechanisms [11]. This process of co-evolution has selected for structures with "privileged scaffolds" that are inherently capable of high-affinity binding to a variety of biological targets. This is why libraries based on natural product scaffolds are considered "biologically pre-validated" and demonstrate a higher hit rate in screening campaigns compared to purely synthetic libraries [8].

This privileged status is evident in recent successes. For instance, the natural products FR901464 and pladienolide B were discovered to inhibit the spliceosome, a massive macromolecular complex involved in mRNA splicing, by binding to the SF3b subcomplex and modulating critical protein-protein interactions [11]. Their analogs have even advanced to clinical trials for cancer, demonstrating the potential of NPs to drugg challenging targets. Furthermore, a 2025 study on HER2-positive breast cancer identified several natural scaffolds, including oroxin B and liquiritin, which suppressed HER2 catalysis with nanomolar potency and showed promising selective anti-proliferative effects in cellular assays [15].

Table 1: Key Advantages of Natural Products in Anticancer Drug Discovery

| Advantage | Description | Implication for Anticancer Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Diversity | Complex skeletons with high stereochemical complexity; distinct from synthetic libraries [11]. | Access to novel mechanisms of action and ability to target undrugged cancer pathways. |

| Biological Pre-Validation | Results from co-evolution with biological targets; contain "privileged scaffolds" [8]. | Higher probability of hit discovery in biological screens; effective against challenging targets like PPIs [11]. |

| Proven Clinical Success | ~60% of cancer drugs and 80% of recent small molecule anticancer drugs are NP-based/inspired [9] [10]. | Strong historical precedent and reduced development risk for NP-derived leads. |

| Synergy with Computation | NP scaffolds provide excellent starting points for computational optimization via 3D-QSAR, docking, etc. [9]. | Enables rational, data-driven optimization of complex NP structures for improved potency and selectivity. |

3D-QSAR as a Bridge from Natural Products to Drug Candidates

Core Principles and Workflow of 3D-QSAR

Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) is a computational methodology that establishes a quantitative correlation between the three-dimensional molecular field properties of a set of compounds and their biological activity. Unlike traditional 2D-QSAR, which uses molecular descriptors derived from the two-dimensional structure, 3D-QSAR considers spatial characteristics such as steric bulk, electrostatic potential, and hydrophobic interactions surrounding the molecule [14]. This is particularly suited to natural products, where activity is often governed by specific conformational and spatial arrangements.

The standard workflow for a 3D-QSAR study, such as those employing a Gaussian-based method or the Field-based QSAR tool in Schrödinger, involves several critical steps [12] [13]:

- Data Set Compilation and Molecular Modeling: A series of structurally related natural products with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC50 values) are collected. Their 3D structures are built and subjected to geometry optimization, often using semi-empirical or ab initio methods to obtain energetically stable conformations.

- Molecular Alignment: This is the most critical step. All molecules are superimposed in 3D space based on a common pharmacophore hypothesis or a rigid core structure. The quality of the alignment directly dictates the success of the model.

- Descriptor Calculation and Model Building: A grid is placed around the aligned molecules. At each point on the grid, molecular field values (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor) are calculated for every compound. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is then used to correlate these field descriptors with the biological activity, generating the QSAR model.

- Model Validation: The model's predictive ability is rigorously tested. Statistical parameters like the cross-validated correlation coefficient (q² > 0.5) and the non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (r² > 0.6) are used to assess internal and external predictive power [16]. A stable model with a high predictive r² for an external test set is considered reliable.

- Model Interpretation and Application: The model is interpreted using contour maps that highlight regions in 3D space where specific molecular properties favorably or unfavorably influence biological activity. These maps guide the design of new analogs with predicted higher activity.

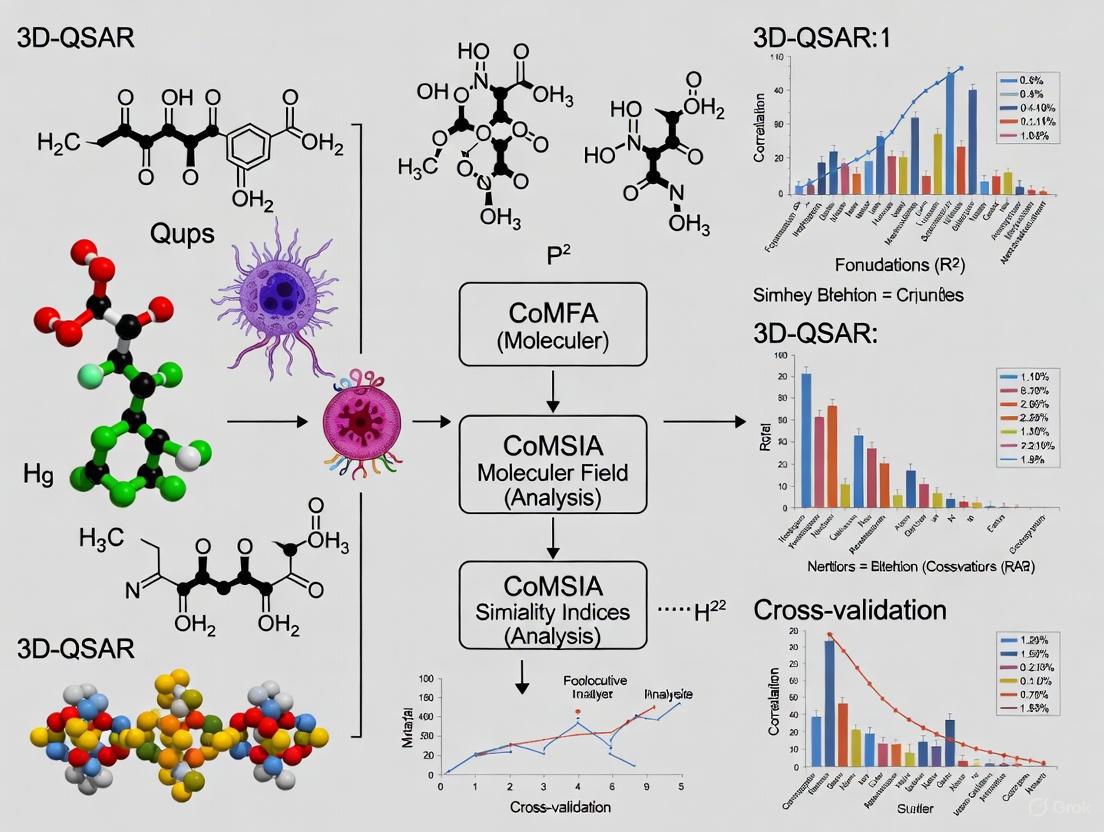

The following diagram visualizes this interconnected experimental and computational workflow:

Case Studies in Anticancer Discovery

The integration of 3D-QSAR with natural products research has yielded several success stories, demonstrating its power in lead optimization.

Case Study 1: Indole-Based Aromatase Inhibitors for Breast Cancer A 2025 study on indole-based aromatase inhibitors for ER+ breast cancer successfully integrated Gaussian-based 3D-QSAR with pharmacophore mapping [12]. The generated model exhibited excellent statistical quality (r² = 0.7621, stability = 0.817). The model revealed that specific steric and electrostatic features surrounding the indole core were critical for optimal inhibitory activity. Concurrent pharmacophore mapping identified that a Hydrogen-bond Donor (D), a Hydrophobic (H) feature, and three aromatic rings (R) are essential for potent activity. Using these computational insights, the researchers designed a novel compound, S1, which demonstrated a predicted IC50 of 9.332 nM, a potency comparable to the reference drug letrozole [12].

Case Study 2: Lonchocarpin, a Natural Chalcone for Lung Cancer A 3D-QSAR study on lonchocarpin, a natural chalcone from Pongamia pinnata, aimed to understand its potent pro-apoptotic activity against lung cancer cells (H292) [13]. The field-based QSAR model indicated that steric (51% contribution) and hydrophobic (23% contribution) features were the most critical determinants of its antitumor activity. The contour maps guided the interpretation, showing that methyl substitutions on one ring system were located in a sterically favorable region (green contours), while the aromatic rings were positioned in areas favoring hydrophobic interactions (yellow contours) [13]. This information is crucial for designing more potent chalcone analogs. Further docking and experimental validation confirmed that lonchocarpin induces apoptosis by binding to the BH3-binding groove of Bcl-2 and modulating the Bax/Caspase-9/Caspase-3 pathway [13].

Case Study 3: Naphthoquinones with Broad-Spectrum Activity QSAR modeling was applied to a series of fourteen 1,4-naphthoquinones with demonstrated anticancer activities against four cell lines (HepG2, HuCCA-1, A549, and MOLT-3) [17]. Four robust QSAR models were constructed using Multiple Linear Regression (MLR). The models highlighted that potent anticancer activity was primarily influenced by descriptors related to polarizability (MATS3p), van der Waals volume (GATS5v), electronegativity (E1e), and dipole moment [17]. These insights into the key structural features governing activity were then used to rationally design and predict the activities of 248 new structurally modified compounds, significantly accelerating the lead optimization process.

Table 2: Summary of Recent 3D-QSAR Studies on Anticancer Natural Products

| Natural Product Class | Biological Target / Cancer Model | Key 3D-QSAR Findings | Experimental Validation | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indole Derivatives | Aromatase / ER+ Breast Cancer | Steric and electrostatic features critical; H-bond donor & hydrophobic pharmacophore essential. | Designed compound S1 showed predicted pIC50 of 9.332 nM, comparable to Letrozole. | [12] |

| Chalcones (e.g., Lonchocarpin) | Bcl-2 / Lung Cancer (H292 cells) | Steric (51%) and hydrophobic (23%) field properties are major activity determinants. | Induced apoptosis (47.9% at 48h); inhibited tumor growth by up to 72.51% in S180-bearing mice. | [13] |

| 1,4-Naphthoquinones | Multiple Cell Lines (e.g., HepG2, A549) | Polarizability, van der Waals volume, and dipole moment are key activity drivers. | Guided rational design of 248 new compounds; top compound 11 showed IC50 = 0.15 – 1.55 μM. | [17] |

| Flavonoids from C. procera | Wound Healing Proteins / Antimicrobial | Model identified structural parameters for antimicrobial IC50, relevant for adjuvant cancer care. | Identified Stigmasterol as a hit compound with better activity than standard antibiotics. | [16] |

Advancing from a natural product lead to a pre-clinical candidate requires a suite of specialized experimental and computational tools. The following table details key resources for this process.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for NP-Based Anticancer Discovery

| Category / Item | Function / Description | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Product Libraries | Curated collections of pure NPs or NP-inspired compounds for screening. (e.g., ChemDiv's NP Library: 18,500 compounds, 22 scaffolds). | Initial hit discovery; source of diverse scaffolds for building QSAR datasets [10]. |

| Cell-Based Assay Kits | Reagents for evaluating cytotoxicity and mechanism (e.g., MTT assay kits, Annexin V/PI apoptosis kits). | In vitro activity testing (IC50 determination); validation of apoptotic mechanisms [13]. |

| Protein Targets | Recombinant human cancer target proteins (e.g., HER2 kinase domain, Bcl-2, Aromatase). | In vitro biochemical assays; target identification and binding affinity studies [15]. |

| Molecular Modeling Software | Platforms for 3D-QSAR, docking, and dynamics (e.g., Schrödinger Suite, FLARE). | 3D structure optimization, molecular alignment, QSAR model generation, and contour map visualization [12] [16]. |

| Chemical Descriptor Software | Tools for calculating molecular descriptors and fingerprints (e.g., PaDEL, Dragon). | Generation of thousands of structural and physicochemical descriptors for QSAR model building [17] [14]. |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | In silico prediction of pharmacokinetics and toxicity (e.g., QikProp, SwissADME). | Early assessment of drug-likeness, oral bioavailability, and potential toxicity liabilities [15]. |

Natural products remain an irreplaceable foundation for anticancer drug discovery. Their unparalleled structural diversity and biologically validated scaffolds provide a critical starting point for addressing both established and novel, challenging oncology targets. The synergy between this natural chemical resource and advanced computational methodologies like 3D-QSAR creates a powerful pipeline for modern drug development. 3D-QSAR transforms the complex structures of natural products into quantifiable, interpretable data, guiding the rational optimization of potency and selectivity. As computational power increases with the integration of artificial intelligence and deep learning, the ability to efficiently mine and optimize the vast potential of natural products will only accelerate, promising a continued flow of innovative and effective anticancer therapies derived from nature's blueprint.

Molecular Fields, Alignments, and the Bioactive Conformation

In the realm of computer-aided drug design, particularly for anticancer natural products, understanding the three-dimensional molecular interactions that govern biological activity is paramount. Molecular fields, alignments, and the bioactive conformation represent foundational concepts in three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling. These elements bridge the gap between a compound's chemical structure and its biological effect by quantifying the spatial and electronic features critical for target recognition [14]. The bioactive conformation refers to the specific three-dimensional geometry a molecule adopts when bound to its biological target, a state that may differ from its lowest energy solution conformation [18]. Accurate determination of this conformation is essential for meaningful 3D-QSAR analysis, as the model's predictive power hinges on correctly representing this interaction state. For natural product research, where compounds often serve as complex scaffolds, these principles provide a systematic framework for optimizing anticancer activity by revealing the steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic requirements of target binding sites.

Core Concepts in 3D-QSAR

The Nature of Molecular Fields

Molecular fields are computational representations of the physicochemical forces a molecule exerts in its surrounding three-dimensional space. These fields are calculated at grid points surrounding a molecule and represent the potential energy of interaction with a probe. The principal fields used in 3D-QSAR studies include:

- Steric Fields: Represent the van der Waals forces and shape characteristics of a molecule, indicating regions where bulk is favorable or unfavorable for activity [18] [19].

- Electrostatic Fields: Map the positive and negative electrostatic potentials, revealing areas where charge interactions with the target occur [18] [19].

- Hydrophobic Fields: Describe the propensity for hydrophobic interactions, a key driver in ligand binding [18].

These fields collectively define a pharmacophore – the essential arrangement of structural features responsible for a molecule's biological activity [14]. In anticancer drug discovery, particularly with natural products, mapping these fields helps identify which structural regions control potency and selectivity.

The Critical Role of Molecular Alignment

Molecular alignment is the process of superimposing a set of molecules to maximize the similarity of their chemically relevant features. This step is crucial because 3D-QSAR models assume all compounds interact with the same biological target in a geometrically consistent manner [20]. The alignment process determines how molecular fields are compared across compounds, directly impacting model quality and interpretability.

Several alignment strategies exist, each with advantages and limitations:

- Template-Based Alignment: Molecules are aligned to a common reference structure, often the most active compound or a known pharmacophore [18].

- Common Substructure Alignment: A shared structural scaffold is used for superimposition.

- Field-Based Alignment: Direct alignment based on molecular field similarity rather than atomic positions.

The choice of alignment method significantly affects model performance. Studies have shown that even simple 2D-to-3D conversion without extensive optimization can sometimes produce superior models compared to energy-minimized and conformation-aligned approaches, achieving high predictive accuracy in significantly less computational time [20].

Defining the Bioactive Conformation

The bioactive conformation is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms when a ligand is bound to its biological target. A fundamental challenge in 3D-QSAR is that this conformation is often unknown, especially in the early stages of drug discovery when structural data on the target protein may be unavailable [18].

Several approaches exist to approximate bioactive conformations:

- Global Energy Minimum: Assumes the lowest energy conformation represents the bound state, which may not always be accurate [20].

- Pharmacophore-Based Conformer Selection: Uses field and shape information to determine a hypothesis for the 3D conformation [18].

- Dock-Derived Conformations: Utilizes molecular docking to generate putative bound conformations when target structure is available.

For natural products with complex, flexible structures, identifying the true bioactive conformation is particularly challenging but essential for developing predictive 3D-QSAR models in anticancer research.

Experimental Protocols for 3D-QSAR Model Development

Data Collection and Preparation

The initial phase involves compiling a structurally diverse set of compounds with reliably measured biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀ values). For natural product studies, this typically includes analogs with modified functional groups to explore structure-activity relationships. Activity data is converted to pIC₅₀ (-logIC₅₀) to normalize the scale for modeling [18].

Structure preparation involves:

- Drawing 2D chemical structures using tools like ChemDraw [21].

- Converting 2D structures to 3D using converter modules (e.g., ChemBio3D) [18].

- Geometry optimization using molecular mechanics (MM+ force field) followed by semi-empirical methods (AM1 or PM3) [21].

- Conformational analysis to identify low-energy conformers.

Conformational Analysis and Pharmacophore Generation

When structural information for the target-bound state is unavailable, as is common with novel natural products, the FieldTemplater module (Forge software) can determine a hypothesis for the 3D conformation using field and shape information from known active compounds [18]. The process involves:

- Selecting a subset of highly active and structurally diverse compounds as potential templates.

- Generating field points using the eXtended Electron Distribution (XED) force field to calculate positive/negative electrostatic, shape, and hydrophobic fields.

- Creating a 3D field point pattern that provides a condensed representation of the compound's key interaction features.

- Annotating the hypothesis with calculated field points to produce a pharmacophore template.

Molecular Alignment and Descriptor Calculation

Using the pharmacophore template, compounds are aligned with the identified template in 3D-QSAR software [18]. Field point-based descriptors are then calculated for building the 3D-QSAR model after alignment. Key parameters include:

- Setting the maximum number of PLS components (typically 15-20).

- Defining sample point maximum distance (e.g., 1.0 Å).

- Including relevant molecular fields (electrostatics, sterics, hydrophobics).

- Using the SIMPLS algorithm for PLS regression during QSAR modeling.

Model Validation and Visualization

Robust validation is essential for reliable 3D-QSAR models. Standard validation protocols include:

- Internal Validation: Leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation yielding q² value [18] [22].

- External Validation: Using a test set of compounds not included in model building [18].

- Statistical Assessment: Evaluating regression coefficient (r²), F-value, and standard error of estimate [21].

Activity-Atlas modeling provides qualitative 3D visualization of structure-activity relationships, revealing favorable/unfavorable regions for steric bulk, positive/negative electrostatics, and hydrophobicity [18].

Comparative Analysis of 3D-QSAR Methodologies

Statistical Performance of Different Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of 3D-QSAR Methodologies and Their Performance Metrics

| Methodology | Application | Statistical Performance | Key Advantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMSIA | Dihydropteridone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors | Q²=0.628, R²=0.928, F-value=12.194, SEE=0.160 | Combines steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields; Excellent predictive power | [21] |

| Field-Based QSAR | Maslinic acid analogs against breast cancer | R²=0.92, q²=0.75 | High correlation; Effective for natural product analogs | [18] |

| 3D-QSDAR | Androgen receptor binders | R²Test=0.61 (2D>3D approach) | Alignment-independent; Fast computation; Good for large datasets | [20] |

| Alignment-Independent GRIND | Mer tyrosine kinase inhibitors | q²=0.77, r²pred=0.94, RMSEP=0.25 | No alignment needed; Excellent external prediction | [23] |

Alignment Strategies: Comparative Effectiveness

Table 2: Impact of Molecular Alignment Strategies on 3D-QSAR Model Quality

| Alignment Strategy | Description | Computational Demand | Predictive Accuracy (R²) | Recommended Use Cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D>3D Conversion | Direct conversion without optimization | Low (3-7% of other methods) | R²=0.61 | Large datasets; Initial screening; Rigid molecules | [20] |

| Energy Minimization | Global minimum of potential energy surface | High | R²=0.56-0.61 | Flexible molecules when bioactive conformation unknown | [20] |

| Template Alignment | Alignment to common pharmacophore | Medium to High | Varies by template selection | When reliable template exists; Series with common scaffold | [18] |

| Field-Based Alignment | Alignment by molecular field similarity | Medium | Dependent on field calculation | Diverse structures; Natural products with varied scaffolds | [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in 3D-QSAR | Application Context | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Drawing | ChemDraw | 2D structure creation and initial optimization | Initial molecular representation | [21] |

| 3D Optimization | HyperChem, ChemBio3D | 2D to 3D conversion; geometry optimization | Molecular mechanics and semi-empirical optimization | [21] [18] |

| Descriptor Calculation | CODESSA | Computation of molecular descriptors | Quantum chemical, structural, topological descriptor generation | [21] |

| Pharmacophore Generation | FieldTemplater (Forge) | Field-based pharmacophore hypothesis creation | Bioactive conformation determination without structural target data | [18] |

| 3D-QSAR Modeling | Forge, SYBYL | Alignment, field calculation, and PLS regression | Core 3D-QSAR model development and validation | [18] |

| Docking Validation | Molecular docking software | Binding mode analysis and model verification | Confirm putative binding poses and interaction patterns | [21] [18] |

Workflow Visualization: 3D-QSAR Model Development

Figure 1: 3D-QSAR Model Development Workflow. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive process from initial compound collection to final new compound design, highlighting critical decision points in conformational analysis and molecular alignment.

Molecular fields, alignments, and the bioactive conformation constitute the fundamental triad of effective 3D-QSAR modeling in natural product anticancer research. The integration of these elements enables researchers to transform structural information into predictive models that guide rational drug design. As demonstrated across multiple studies, the careful selection of alignment strategies and bioactive conformation determination methods directly impacts model quality and predictive capability. The ongoing advancement of alignment-independent techniques and robust validation protocols continues to enhance the applicability of 3D-QSAR to complex natural product scaffolds, accelerating the discovery of novel anticancer therapeutics with improved efficacy and selectivity profiles.

The discovery of novel anticancer compounds from natural products presents a unique challenge due to the structural complexity and diversity of phytochemicals. Within this endeavor, Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has emerged as a pivotal computational methodology for rational drug design. This technical guide details the comprehensive workflow from initial data curation to final predictive model building, specifically framed within natural product anticancer research. The systematic application of this workflow enables researchers to decode the essential structural features responsible for biological activity, thereby accelerating the identification and optimization of lead compounds against cancer targets such as estrogen receptors for breast cancer [24] [14].

Data Curation and Preparation

The foundation of any robust 3D-QSAR model is a high-quality, well-curated dataset. This initial phase is critical, as the model's predictive power is directly contingent upon the accuracy and consistency of the input data.

Data Collection and Curation

The process begins with the assembly of a library of chemical structures and their associated biological activities, typically expressed as half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀), inhibitory constant (Kᵢ), or dissociation constant (K𝒹). For natural products, data can be sourced from public databases such as the Traditional Chinese Medicine Database (TCMDb), ChEMBL, and BindingDB [25]. The primary objective is to collect a congeneric series of molecules that interact with a specific anticancer target, such as estrogen receptors (ESR1/ESR2) or aromatase [24] [26].

Key Steps in Data Curation:

- Structure Standardization: Remove salt ions, standardize tautomers, and handle stereochemistry consistently using software like Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) or Open Babel [25].

- Activity Data Standardization: Convert all biological activities to a common unit (e.g., nM) and scale them, often by converting to negative logarithmic units (pIC₅₀ = -log₁₀IC₅₀) to create a uniformly varying response variable [27] [28].

- Duplicate Removal: Identify and remove duplicate compounds using unique molecular identifiers like InChIKey [25].

- Data Splitting: Divide the dataset into a training set (typically 70-80% of compounds) for model development and a test set (the remaining 20-30%) for external validation. Methods like the Kennard-Stone algorithm can be used to ensure both sets are representative of the overall chemical space [27] [29].

Molecular Geometry Optimization

Once curated, the 3D structures of all compounds must be generated and energetically optimized. This is a crucial step for 3D-QSAR, as the model is sensitive to the spatial orientation of functional groups.

- Conformer Generation: Multiple low-energy conformers are generated for each molecule using algorithms like MCMM/LMOD, typically producing hundreds of conformers with a relative energy difference threshold of 20 kcal/mol [24] [29].

- Energy Minimization: The generated conformers are subjected to geometry optimization using force fields (e.g., MMFF94) or quantum mechanical methods to obtain the most stable 3D structure [24].

Table 1: Key Data Curation and Preparation Steps

| Step | Description | Common Tools/Software |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | Assembling structures and bioactivity data from literature and databases. | TCMDb, ChEMBL, BindingDB, DrugBank [25] |

| Structure Standardization | Removing salts, standardizing tautomers, defining correct chirality. | MOE, Open Babel [25] [27] |

| Activity Conversion | Converting IC₅₀/Kᵢ values to pIC₅₀/pKᵢ for uniform analysis. | In-house scripts, Excel [27] [28] |

| Conformer Generation | Creating multiple 3D structures representing possible molecular shapes. | Schrödinger Maestro, MOE, Open Babel [24] [29] |

| Molecular Alignment | Superimposing molecules based on a common scaffold or pharmacophore. | Schrödinger Phase, ROCS [24] [29] |

Molecular Modeling and Pharmacophore Development

With a prepared dataset, the next phase involves translating 3D structural information into quantitative descriptors and identifying the common pharmacophoric features essential for biological activity.

Molecular Alignment and Descriptor Calculation

Molecular alignment is the most critical step in 3D-QSAR, as it defines the spatial frame of reference for comparing molecules.

- Alignment Rules: Molecules can be aligned using a common rigid scaffold, a known active compound, or a pharmacophore hypothesis [28] [29].

- Field Calculation: Once aligned, molecules are placed into a 3D grid. Probe atoms (e.g., an sp³ carbon for steric fields and a proton for electrostatic fields) are used to calculate interaction energies at each grid point. Methods like Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) calculate steric (Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (Coulombic potential) fields, while Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) may include additional fields like hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and acceptor [28].

Pharmacophore Model Generation

A pharmacophore is an abstract representation of the molecular features necessary for biological recognition. It is derived either from a set of active ligands (ligand-based) or from the 3D structure of the target protein (structure-based).

- Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: Using a training set of active and inactive compounds, software like Schrödinger's Phase generates hypotheses comprising features such as hydrogen bond acceptors (A), donors (D), hydrophobic regions (H), aromatic rings (R), and positively ionizable groups (P). The best hypothesis is selected based on statistical scores like survival score, volume overlap, and selectivity [24] [29]. For example, a model named

HPRRRindicates one Hydrogen bond donor, one Positive ionizable group, and three aRomatic Rings [29]. - E-Pharmacophore Modeling: This structure-based method combines energy terms from protein-ligand docking (e.g., using Glide) with traditional pharmacophore features to create energy-optimized (

e-pharmacophore) hypotheses, which are often more precise [29].

Table 2: Core Components of a 3D-QSAR Modeling Toolkit

| Category | Research Reagent / Software | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics | PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, RDKit | Calculates thousands of 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors and fingerprints. |

| Molecular Modeling | Schrödinger Suite, MOE, Open Babel | Generates 3D structures, performs geometry optimization, and conformational analysis. |

| Alignment & Modeling | ROCS, Schrödinger Phase | Superimposes molecules and performs 3D-QSAR calculations (CoMFA, CoMSIA). |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Schrödinger Phase, Catalyst | Generates and validates ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore models. |

| Statistical Analysis | SIMCA, R, Python (scikit-learn) | Performs Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression and other multivariate analyses. |

3D-QSAR Model Building and Validation

This stage involves constructing the mathematical model that relates the computed 3D fields to the biological activity and rigorously testing its predictive capability.

Model Construction using Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression

Given the high dimensionality and collinearity of 3D-field descriptors (where the number of variables far exceeds the number of compounds), Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is the algorithm of choice [28] [29]. PLS reduces the descriptor variables to a smaller number of latent variables that have the highest covariance with the biological activity.

- Model Statistics: The quality of the model is assessed using several statistical parameters derived from the training set [29]:

- R² (Coefficient of Determination): Measures the goodness of fit (how well the model explains the variance in the training data). A value closer to 1.0 indicates a good fit.

- Q² (or q² from Cross-Validation): Measures the internal predictive power of the model. A Q² > 0.5 is generally considered acceptable, and > 0.7 is good.

- Standard Deviation (SD): The standard error of the estimate.

- F Value: The Fischer statistic indicating the overall significance of the model.

- Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE): The average magnitude of the prediction errors.

Model Validation

Validation is paramount to ensure the model is robust and not over-fitted to the training data. It involves both internal and external validation [27] [28].

- Internal Validation:

- Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation: Iteratively, one compound is removed from the training set, the model is rebuilt with the remaining compounds, and the activity of the left-out compound is predicted. The predicted activities are used to calculate Q² [29].

- Leave-Group-Out Cross-Validation: Similar to LOO, but a group of compounds is left out in each iteration.

- External Validation: The ultimate test of a model's utility is its ability to accurately predict the activity of the external test set of compounds that were never used in model building. The predictive R² (r²pred) for the test set should be greater than 0.6 [30] [29].

- Y-Scrambling: This test checks for chance correlation. The biological activity data is randomly shuffled, and new models are built. A valid original model should have significantly higher R² and Q² values than the scrambled models [28].

Table 3: Key Statistical Metrics for 3D-QSAR Model Validation

| Metric | Description | Interpretation & Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| N | Number of compounds in the training set. | Should be sufficient for the chosen descriptors (typically > 20). |

| R² | Coefficient of determination. | Goodness-of-fit; should be high (e.g., > 0.8) [29]. |

| Q² | Cross-validated R². | Internal predictivity; Q² > 0.5 is acceptable, > 0.7 is good [29]. |

| RMSE | Root-Mean-Square Error. | Average prediction error; lower values are better. |

| PLS Factors | Number of latent variables used in the model. | Should be optimal; too few lead to underfitting, too many to overfitting. |

| r²pred | Predictive R² for the external test set. | Gold standard for external predictivity; should be > 0.6 [30]. |

Application in Natural Product Anticancer Research

The integrated 3D-QSAR and pharmacophore workflow has proven highly effective in identifying and optimizing natural products for cancer therapy. For instance, a study targeting breast cancer estrogen receptors curated a library of 202 natural phytochemicals. Following the outlined workflow, the research identified key pharmacophore features and built a reliable 3D-QSAR model, which highlighted five promising candidates—Genistein, Coumestrol, Apigenin, Emodin, and Rhein—as potent inhibitors [24].

The generated 3D-QSAR models provide visual contour maps that offer intuitive insights for medicinal chemists. These maps show regions in 3D space where increased steric bulk or specific electrostatic properties would enhance or diminish biological activity. This guides the rational design of novel derivatives with improved potency [24] [26] [14]. Furthermore, the validated pharmacophore model can be used as a query for virtual screening of large chemical databases, including natural product libraries, to identify new hit compounds with novel scaffolds that match the essential features for anticancer activity [24] [29].

The computational workflow from data curation to 3D-QSAR model building is a powerful, iterative process that leverages the structural information of natural products to decipher the complex code of biological activity. By adhering to rigorous protocols for data preparation, molecular alignment, statistical modeling, and—most critically—model validation, researchers can develop robust predictive tools. These models serve as invaluable guides in the rational design of novel, potent, and selective anticancer agents derived from nature's chemical wealth, thereby streamlining the drug discovery pipeline and reducing reliance on serendipity.

Natural products have served as a cornerstone of cancer chemotherapy for decades, providing a rich source of chemical diversity with profound therapeutic potential. It is estimated that over 60% of approved anticancer drugs are derived from natural sources in one way or another [31]. These compounds have not only revolutionized cancer treatment but have also provided invaluable insights into cancer biology through their unique mechanisms of action. The historical successes of natural products in oncology demonstrate the power of nature to yield complex chemical scaffolds that would be difficult to conceive or synthesize through conventional medicinal chemistry approaches. This review examines pivotal case studies of natural product-derived cancer therapeutics, with particular emphasis on how these historical successes inform modern computational approaches, specifically three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) methodologies, in the ongoing search for novel anticancer agents from nature.

Foundational Case Studies of Natural Products in Oncology

Plant-Derived Anticancer Agents

Vinca Alkaloids

The first plant-derived agents to advance into clinical use were the vinca alkaloids, vinblastine and vincristine, isolated from the Madagascar periwinkle, Catharanthus roseus G. Don [31]. This plant was historically used by various cultures for the treatment of diabetes, but during investigations of its potential as a source of oral hypoglycemic agents, researchers observed that extracts reduced white blood cell counts and caused bone marrow depression in rats. Subsequent testing revealed activity against lymphocytic leukemia in mice, leading to the isolation of vinblastine and vincristine as the active anticancer agents.

Mechanism of Action: Vinca alkaloids disrupt microtubule formation, causing arrest of cell division at metaphase and ultimately leading to apoptotic cell death [31]. They achieve this by binding to tubulin and inhibiting the assembly of microtubules, which are essential components of the mitotic spindle.

Clinical Applications and Development: These agents are primarily used in combination with other chemotherapeutic drugs for treating various cancers, including leukemias, lymphomas, advanced testicular cancer, breast and lung cancers, and Kaposi's sarcoma [31]. Semisynthetic analogues such as vinorelbine and vindesine were subsequently developed, with the most recent being vinflunine, a second-generation bifluorinated analogue of vinorelbine.

Taxanes

The taxanes represent one of the most important classes of cancer chemotherapeutic drugs in clinical use. Paclitaxel (Taxol) was originally isolated from the bark of the Pacific yew, Taxus brevifolia Nutt., while docetaxel (Taxotere) is a semisynthetic analogue synthesized from 10-deacetylbaccatin III isolated from the leaves of the European yew, Taxus baccata [31]. Interestingly, the leaves of T. baccata are used in traditional Asiatic Indian (ayurvedic) medicine, with one reported use being in the treatment of 'cancer' [31].

Mechanism of Action: Unlike vinca alkaloids, paclitaxel and other taxanes promote the polymerization of tubulin heterodimers to microtubules and suppress dynamic changes in microtubules, resulting in mitotic arrest [31]. This unique mechanism represents a complementary approach to targeting the mitotic apparatus in cancer cells.

Clinical Applications and Challenges: Paclitaxel is used in the treatment of breast, ovarian, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and has also shown efficacy against Kaposi's sarcoma, while docetaxel is primarily used in the treatment of breast cancer and NSCLC [31]. The clinical development of taxanes faced significant challenges, including supply issues due to the slow growth of yew trees and poor solubility of the compounds. These hurdles were overcome through the development of semisynthetic production methods and novel formulations, such as albumin-bound nanoparticle (nab) technology, which circumvented the severe toxicities caused by earlier formulations [32].

Camptothecins

The anticancer activity of camptothecin, isolated from wood and bark of Camptotheca acuminata, was initially noted in the early 1960s, but its application as an anticancer agent languished for almost 20 years until its mechanism of action was uncovered [32]. Camptothecin specifically traps topoisomerase I, an enzyme critically involved in both DNA replication and transcription processes, forming topoisomerase-DNA complexes that cause severe genomic stress when colliding with ongoing DNA replication forks or transcription machinery, ultimately leading to cell death [32].

Clinical Development: In the mid-1990s, two camptothecin analogs, topotecan and irinotecan, received FDA approval for treating various cancers including ovarian, lung, breast and colon cancers [32]. Additionally, 10-hydroxycamptothecin, with reduced toxicity compared with camptothecin, has been used against hepatoma, colon cancer and bladder cancer in China since the 1970s. The legacy of camptothecin continues with new derivatives such as chimmitecan currently undergoing clinical trials [32].

Table 1: Historical Plant-Derived Anticancer Agents and Their Properties

| Natural Product | Source Plant | Mechanism of Action | Clinical Applications | Year of Discovery/Approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinblastine/Vincristine | Catharanthus roseus | Microtubule disruption, mitotic arrest | Leukemias, lymphomas, testicular cancer | 1960s (discovery) |

| Paclitaxel | Taxus brevifolia | Microtubule stabilization, mitotic arrest | Breast, ovarian, NSCLC, Kaposi's sarcoma | 1971 (structure), 1992 (FDA approval) |

| Docetaxel | Semisynthetic from Taxus baccata | Microtubule stabilization | Breast cancer, NSCLC | 1995 (FDA approval) |

| Camptothecin | Camptotheca acuminata | Topoisomerase I inhibition | Various cancers via analogs | 1966 (isolation) |

| Etoposide | Semisynthetic from Podophyllum peltatum | Topoisomerase II inhibition | Lymphomas, bronchial, testicular cancers | 1983 (FDA approval) |

Microorganisms have yielded numerous impactful anticancer agents, showcasing the chemical diversity present in microbial metabolism. Microbial natural products often possess complex structures that have been optimized through evolution for specific biological interactions, making them invaluable as both therapeutic agents and biochemical probes.

Actinomycin D and Mitomycin C

These bacterial-derived compounds represent early successes in cancer chemotherapy. Actinomycin D, isolated from Streptomyces bacteria, intercalates into DNA and inhibits transcription, while mitomycin C functions as a DNA cross-linking agent, causing irreversible damage to DNA structure and function [32]. These mechanisms highlight how natural products can target fundamental cellular processes essential for cancer cell proliferation.

Bleomycin

Bleomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces verticillus, causes single-strand and double-strand breaks in DNA through a metal-dependent oxidative process [32] [31]. Its unique mechanism and relative sparing of bone marrow toxicity made it particularly valuable in combination chemotherapy regimens, especially for Hodgkin's lymphoma and testicular cancer.

Marine-Derived Anticancer Agents

The marine environment represents a relatively untapped reservoir of chemical diversity with significant anticancer potential. Marine organisms often produce unique secondary metabolites as chemical defenses in highly competitive ecosystems, and these compounds frequently possess novel mechanisms of action.

Ecteinascidin 743 (Trabectedin)

Isolated from the marine tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata, trabectedin was approved for the treatment of advanced soft tissue sarcoma and ovarian cancer [31]. It operates through a unique mechanism that includes alkylation of DNA minor grooves and interaction with transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair processes.

Halichondrin B and Derivatives

Halichondrin B, originally isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria okadai, served as the lead compound for the development of eribulin (Halaven), a fully synthetic analog approved for metastatic breast cancer and liposarcoma [31]. Like vinca alkaloids, eribulin inhibits microtubule dynamics but through a distinct binding site and mechanism, demonstrating how natural products can reveal new targeting opportunities even within well-established target classes.

Traditional Medicine-Derived Success: Arsenic Trioxide

The development of arsenic trioxide (Trisenox) for acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) represents a compelling case study in the modernization of traditional medicine [32]. Beginning in the 1970s, arsenic-containing preparations were used for treating APL in China, initially in the form of Ailing-1, a preparation containing arsenic and a trace amount of mercury chloride. Clinical data using the pure form of arsenic trioxide was reported in the mid-1990s, and subsequent trials consolidated its remarkable benefit in APL patients [32].

Mechanistic Insights: In-depth mechanistic studies revealed that arsenic trioxide exhibits its effect by degrading PML-RARα fusion protein, the oncogenic driver of APL [32]. Arsenic trioxide targets the PML moiety of PML-RARα and specifically induces SUMO-dependent degradation via the ubiquitination-proteasome system. The combination of arsenic trioxide with retinoic acid has revolutionized APL treatment, achieving stunning cure rates of approximately 90% [32].

Table 2: Natural Product-Derived Anticancer Agents from Non-Plant Sources

| Natural Product | Source | Mechanism of Action | Clinical Applications | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinomycin D | Streptomyces bacteria | DNA intercalation, transcription inhibition | Wilms' tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma | One of the earliest natural product anticancer antibiotics |

| Mitomycin C | Streptomyces caespitosus | DNA cross-linking | Gastric, pancreatic cancers | Bio-reductive activation |

| Bleomycin | Streptomyces verticillus | DNA strand breakage | Hodgkin's lymphoma, testicular cancer | Limited bone marrow toxicity |

| Trabectedin | Marine tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata | DNA minor groove alkylation | Soft tissue sarcoma, ovarian cancer | Also targets tumor microenvironment |

| Eribulin | Synthetic analog of Halichondrin B from marine sponge | Microtubule inhibition | Metastatic breast cancer, liposarcoma | Distinct binding site from other microtubule agents |

The Transition to Modern Computational Approaches

Challenges in Natural Product Drug Discovery

Despite their remarkable successes, natural products present significant challenges for drug discovery, including technical barriers to screening, isolation, characterization, and optimization [33]. These challenges contributed to a decline in their pursuit by the pharmaceutical industry from the 1990s onwards, as attention shifted to combinatorial chemistry and target-based screening approaches. Specific challenges include:

Supply and Sustainability: Many natural products occur in minute quantities in their source organisms, creating supply challenges for development and clinical use [32]. The story of taxol, originally isolated from the bark of the Pacific yew tree, exemplifies this challenge, as sustainable production required development of semisynthetic methods from more abundant precursors [31].

Structural Complexity: The complex structures of many natural products make total synthesis economically challenging, though semisynthetic approaches often provide viable solutions [31].

Mechanistic Understanding: Elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms of natural products can be challenging but is essential for their rational development and application [32].

The Role of 3D-QSAR in Modern Natural Product Research

Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) methodologies have emerged as powerful tools for optimizing natural product leads and understanding their interactions with biological targets. These computational approaches analyze the relationship between the three-dimensional structural properties of molecules and their biological activities, enabling rational drug design even for complex natural product scaffolds.

Fundamentals of 3D-QSAR

3D-QSAR techniques, such as Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), employ statistical methods to correlate biological activity with spatial characteristics of molecules, including steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding properties [3] [16]. These methods generate predictive models that can guide the optimization of lead compounds by suggesting specific structural modifications likely to enhance potency and selectivity.

Application to Natural Products

The application of 3D-QSAR to natural product research is particularly valuable given the structural complexity of these compounds. For example, a study on naphthoquinone derivatives demonstrated the successful implementation of 3D-QSAR for predicting anti-proliferative activity against colorectal cancer cells [3]. The generated CoMFA model exhibited strong statistical reliability (r² = 0.99 and q² = 0.625), enabling the proposal of five new compounds with predicted two-fold higher theoretical anti-proliferative activity than the parent compounds [3].

Similarly, Gaussian-based 3D-QSAR studies of indole derivatives as aromatase inhibitors have identified essential steric and electrostatic features required for optimal biological activity, with developed models successfully predicting compound activity in the nanomolar range [12]. These approaches allow researchers to prioritize which natural product analogs to synthesize and test, significantly accelerating the optimization process.

Integrating Historical Knowledge with Contemporary 3D-QSAR Approaches

From Historical Cases to Computational Models

The historical case studies of natural products in cancer therapy provide invaluable structural and mechanistic information that informs contemporary 3D-QSAR studies. The well-characterized mechanisms of action of established natural product drugs offer validated biological targets for which additional natural product leads can be optimized using computational approaches. Furthermore, the structural diversity represented by historical successes provides templates for molecular alignment and field calculation in 3D-QSAR studies.

Workflow for 3D-QSAR in Natural Product Development

The application of 3D-QSAR to natural product-based drug discovery follows a systematic workflow that integrates computational and experimental approaches:

Diagram 1: 3D-QSAR Guided Natural Product Development Workflow. This workflow illustrates the iterative process of combining computational predictions with experimental validation in natural product-based drug discovery.

Successful Applications of 3D-QSAR to Natural Product-Derived Compounds

Recent studies demonstrate the successful application of 3D-QSAR methodologies to natural product-derived anticancer agents:

Naphthoquinone Derivatives: As mentioned previously, 3D-QSAR modeling of naphthoquinone derivatives against colorectal cancer cells yielded highly predictive models that guided the design of more potent analogs [3]. The study specifically found that tricyclic naphtho[2,3-b]furan-4,9-dione and naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-dione systems substituted at the 2-position with an electron-withdrawing group exhibited enhanced cytotoxicity.

Indole-Based Aromatase Inhibitors: Gaussian-based 3D-QSAR combined with pharmacophore mapping identified hydrogen bond donor, hydrophobic features, and three aromatic rings as essential for potent aromatase inhibitory activity [12]. The developed model (r² = 0.7621) enabled the design of a compound with predicted activity comparable to the reference drug letrozole.

Calotropis procera Constituents: 3D-QSAR studies on natural compounds from Calotropis procera for wound healing applications demonstrate the broader utility of these approaches for natural product optimization [16]. The generated models successfully identified stigmasterol as a hit compound with better predicted activity than standard antibiotics.

Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Anticancer Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR Natural Product Studies

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Natural Product Research | Application in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Product Libraries | NCI Natural Products Repository [34] | Source of diverse chemical scaffolds for screening | Provides initial lead compounds for 3D-QSAR model development |

| Fractionation Tools | Automated flash chromatography, HPLC [34] | Separation of complex natural extracts into individual components | Enables isolation of pure compounds for structural characterization and activity testing |

| Structural Elucidation Instruments | NMR spectroscopy, LC-MS, X-ray crystallography [32] [33] | Determination of precise molecular structures | Provides essential 3D structural data for molecular alignment and field calculations |

| Computational Chemistry Software | FLARE, SYBYL, Schrodinger Suite [16] [12] | Molecular modeling, docking, and QSAR analysis | Performs molecular alignment, field calculation, and statistical model generation |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | HT-29, MCF-7 cancer cell lines, MTT assay [3] | Evaluation of anti-proliferative activity | Generates biological activity data for QSAR model training and validation |

| Protein Expression & Crystallization | Recombinant protein production, crystallization kits | Target protein structure determination | Provides structural data for structure-based 3D-QSAR and validation of predicted interactions |

The historical successes of natural products in cancer therapy provide both inspiration and foundation for contemporary drug discovery efforts. From the vinca alkaloids and taxanes to arsenic trioxide, these natural products have not only transformed cancer treatment but also revealed fundamental biological processes and potential therapeutic targets. The ongoing revolution in computational methodologies, particularly 3D-QSAR approaches, is addressing historical challenges in natural product research by enabling more efficient optimization of lead compounds and prediction of biological activities. By integrating the structural diversity and validated mechanisms of action from historical natural product successes with modern computational tools, researchers are well-positioned to unlock the next generation of natural product-derived cancer therapeutics. The continued investigation of nature's chemical repertoire, guided by sophisticated computational approaches, promises to yield additional breakthroughs in the ongoing battle against cancer.

Building Predictive Power: A Step-by-Step Guide to 3D-QSAR Model Development and Application

Data Set Preparation and Conformational Analysis for Natural Products

Cancer remains one of the leading global health challenges, with current treatments often limited by toxicity, drug resistance, and lack of selectivity [35]. Natural products represent valuable scaffolds for anticancer drug discovery due to their structural diversity and complex biological activities [6]. Within this context, Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has emerged as a powerful computational approach that correlates the three-dimensional molecular structures of natural compounds with their biological activities against cancer targets [36].

The foundation of reliable 3D-QSAR models depends critically on two fundamental pillars: the careful preparation of high-quality data sets and the accurate determination of molecular conformations [37]. This technical guide provides researchers with comprehensive methodologies for these essential preparatory stages, framed within the specific challenges posed by natural product anticancer research. The protocols outlined herein enable the generation of robust, predictive models that can prioritize promising natural product-derived leads for experimental validation, thereby accelerating the anticancer drug discovery pipeline [35] [6].

Data Set Preparation: Curation and Preprocessing

Data Collection and Selection Criteria

The initial phase of data set preparation involves the systematic collection and curation of natural product structures and their corresponding anticancer activity data.

- Source Selection: Prioritize databases providing standardized bioactivity measurements for natural products against cancer cell lines or molecular targets. Reputable sources include PubChem, ChEMBL, and the ZINC database, which contain experimentally determined IC₅₀, EC₅₀, or Kᵢ values suitable for QSAR modeling [37] [38].

- Activity Data Preparation: For QSAR modeling, quantitative biological activity data should be converted to a logarithmic scale (e.g., pIC₅₀ = -log₁₀(IC₅₀)) to improve data normality and model performance [36]. The dataset should encompass a broad activity range to facilitate meaningful structure-activity relationship analysis.

- Structural Diversity: Ensure the data set includes structurally diverse natural products spanning multiple chemical classes. This diversity enhances the model's applicability domain and predictive capability for novel compounds [36]. A minimum of 20-30 compounds is typically required for initial model development, though larger datasets (containing 100+ compounds) yield more robust and generalizable models [36] [38].

Molecular Structure Standardization

Consistent molecular representation is essential for accurate descriptor calculation and conformational analysis.

- Structure Representation: Convert all molecular structures into a standardized format. While Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings or 1D representations are common, they must be converted to 2D or 3D formats for 3D-QSAR studies [37].

- Protocol: 2D Structure Cleaning

- Remove counterions, solvents, and salts.

- Standardize tautomeric states and functional group representations.

- Assign correct bond orders and formal charges at biological pH (7.4).

- Perform energy minimization using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., MMFF94) to resolve steric clashes and geometric distortions [36].

- Chemical Space Analysis: Apply principal component analysis (PCA) on molecular descriptors to visualize chemical space coverage and identify potential outliers before proceeding to conformational analysis [35].

Table 1: Standardization Protocol for Natural Product Data Sets

| Processing Step | Technical Objective | Recommended Tools/Methods | Quality Control Check |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Curation | Assemble consistent bioactivity data | PubChem, ChEMBL, EDKB | Uniform measurement type (e.g., all IC₅₀) |

| Structure Cleaning | Generate canonical, representative structures | RDKit, OpenBabel | Consistent stereochemistry, charge states |

| Activity Conversion | Normalize data for modeling | pIC₅₀ = -log₁₀(IC₅₀) | Linear distribution of transformed values |

| Chemical Diversity | Ensure broad applicability domain | PCA on molecular descriptors | Clusters representing multiple chemotypes |

Conformational Analysis Methodologies

Conformation Generation Strategies

The biological activity of a molecule is influenced by its three-dimensional conformation when interacting with a biological target. Selecting an appropriate conformational analysis strategy is therefore critical for meaningful 3D-QSAR models [36].