Getting Started with Field-Based 3D-QSAR for Tumor Inhibitors: A Practical Guide for Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing field-based 3D-QSAR to accelerate the discovery of novel tumor inhibitors.

Getting Started with Field-Based 3D-QSAR for Tumor Inhibitors: A Practical Guide for Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing field-based 3D-QSAR to accelerate the discovery of novel tumor inhibitors. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it explores the core theory behind molecular field analysis and offers step-by-step methodologies for building robust models using modern software tools. The content addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, model optimization techniques, and rigorous validation protocols through real-world case studies targeting key oncology targets like JAK-2, BRAFV600E, and PARP14. By integrating 3D-QSAR with molecular dynamics and docking studies, this guide demonstrates a powerful computational framework for rational drug design in oncology, enabling more efficient and targeted cancer therapeutic development.

Understanding Field-Based 3D-QSAR: Core Concepts and Significance in Oncology Drug Discovery

The development of effective tumor inhibitors represents a central challenge in modern medicinal chemistry. For decades, the quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) paradigm has guided researchers in understanding how chemical structure influences biological activity. Traditional 2D-QSAR methods correlate biological activity with numerical descriptors of molecules such as lipophilicity (logP), electronic properties, or steric parameters [1] [2]. While these approaches have generated useful predictive models and contributed to drug discoveries, they treat molecules as essentially flat entities, ignoring their three-dimensional nature and the spatial characteristics critical to molecular recognition processes [3]. This limitation becomes particularly significant in cancer drug design, where inhibitors must precisely complement complex binding pockets of therapeutic targets like protein kinases, tubulin, and various receptors.

The transition from 2D to 3D-QSAR marks a fundamental shift from considering molecules as collections of substituents to treating them as volumetric entities with distinct shape and interaction potential. 3D-QSAR techniques explicitly incorporate the spatial properties of molecules, establishing a correlation between the three-dimensional structural fields of ligands and their biological effects [3]. This advancement has become indispensable in modern tumor inhibitor design, allowing medicinal chemists to visualize and quantify the structural features that enhance or diminish anticancer activity, thereby providing rational guidance for molecular optimization [4] [5]. This technical guide explores the core concepts, methodologies, and applications of field-based 3D-QSAR, framed within the context of tumor inhibitor research.

Core Concepts: Why Molecular Fields Transform Inhibitor Design

The Fundamental Difference: Descriptors vs. Fields

In classical 2D-QSAR, molecules are described using global molecular descriptors that are invariant to conformation and orientation. These include physicochemical parameters like logP for hydrophobicity, molar refractivity for steric bulk, and electronic parameters such as Hammett constants [2]. These descriptors are computationally efficient but offer limited insight into the spatial requirements for target binding.

In contrast, 3D-QSAR describes molecules using interaction fields calculated in three-dimensional space around the molecule. These fields represent the potential interaction energy between a probe atom or group and the molecule at numerous grid points surrounding it [1] [3]. This approach captures the molecule's shape and electronic distribution in a way that directly relates to molecular recognition processes. The most significant fields in tumor inhibitor design include:

- Steric Fields: Represent regions of molecular bulk that may clash with or accommodate target protein residues [1].

- Electrostatic Fields: Map areas of positive or negative potential that influence binding through charge-charge interactions [1].

- Hydrophobic Fields: Identify regions that favor or disfavor interactions with non-polar environments [6].

- Hydrogen Bond Donor/Acceptor Fields: Delineate capabilities for specific polar interactions critical to binding affinity and selectivity [6].

Key Methodological Approaches

Several 3D-QSAR methodologies have been developed, each with distinct advantages for tumor inhibitor design:

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) is the pioneering 3D-QSAR method that calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields on a 3D grid surrounding aligned molecules [4] [3]. The resulting interaction energy values serve as descriptors correlated with biological activity using Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression.

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extends CoMFA by using Gaussian-type functions to evaluate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields [1] [4]. This approach avoids singularities at atomic positions and provides more interpretable contour maps, often making it more suitable for structurally diverse datasets.

Self-Organizing Molecular Field Analysis (SOMFA) is a simpler grid-based technique that uses molecular shape and electrostatic potential directly to construct QSAR models, without requiring complex field calculations [7] [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Major 3D-QSAR Techniques in Tumor Inhibitor Design

| Method | Fields Calculated | Key Advantages | Limitations | Representative Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | Steric, Electrostatic | Established, interpretable results | Sensitive to molecular alignment and orientation | Quinazoline derivatives as HER2 inhibitors [7] |

| CoMSIA | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-bond Donor/Acceptor | More intuitive contours, less sensitive to alignment | More parameters to optimize | Phenylindole derivatives as multi-target cancer inhibitors [5] |

| SOMFA | Shape, Electrostatic potential | Simpler implementation | Less field information | Indole-based aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer [8] |

Methodological Workflow: Implementing 3D-QSAR for Tumor Inhibitors

The construction of a robust 3D-QSAR model requires meticulous execution of multiple sequential steps, each critically influencing the final model's predictive power and utility in tumor inhibitor design.

Data Set Preparation and Curation

The foundation of any reliable QSAR model is a high-quality, congeneric series of compounds with consistently measured biological activities. For tumor inhibitor studies, half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) values are commonly used, converted to pIC₅₀ (-logIC₅₀) to minimize skewness [6] [5]. The dataset should encompass sufficient structural diversity within a common scaffold to provide meaningful structure-activity information, typically 20-50 compounds [9] [6]. The data set is divided into training (typically 70-80%) and test sets (20-30%) to enable model validation [6] [10] [5].

Molecular Modeling and Conformation Selection

3D molecular structures are generated from 2D representations using cheminformatics tools like RDKit or molecular modeling packages such as Sybyl [1]. Geometry optimization is crucial and typically performed using molecular mechanics (e.g., Tripos force field) followed by more accurate semi-empirical (AM1, PM3) or density functional theory (DFT with B3LYP/6-31G*) methods [9] [6] [10].

A critical step is identifying the bioactive conformation – the 3D structure a molecule adopts when bound to its target. When available, experimental data from X-ray crystallography or NMR of protein-ligand complexes provides the most reliable bioactive conformations [3]. Alternatively, molecular docking can generate putative binding poses, while pharmacophore modeling can identify common features essential for activity [7] [8].

Molecular Alignment

Molecular alignment superimposes all molecules in a common 3D reference frame that reflects their putative binding mode, representing one of the most challenging aspects of 3D-QSAR [1]. Common alignment strategies include:

- Atom-based alignment: Superimposing atoms of a common core scaffold [7]

- Pharmacophore-based alignment: Aligning key pharmacophoric features

- Docking-based alignment: Using orientations derived from molecular docking [7]

- Distill rigid alignment: Using algorithms that maximize overlap of similar features [5]

The choice of alignment method significantly impacts model quality, with poor alignment introducing noise and reducing predictive ability [1].

Field Calculation and Model Building

Once aligned, molecules are placed within a 3D grid, and interaction fields are calculated at each grid point. In CoMFA, a probe atom (typically an sp³ carbon with +1 charge) calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) potentials [3]. CoMSIA uses a Gaussian-type function to compute similarity indices for multiple fields, resulting in smoother contours and reduced sensitivity to minor alignment errors [1] [4].

The resulting descriptor matrix, containing thousands of field values, is analyzed using Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, which handles highly correlated variables by projecting them into latent variables that maximize covariance with biological activity [1] [3]. The optimal number of components is determined through cross-validation to avoid overfitting.

Model Validation and Interpretation

Rigorous validation is essential to ensure model reliability for prospective tumor inhibitor design. Key validation metrics include:

- Internal validation: Leave-One-Out (LOO) or Leave-Several-Out cross-validation, reported as Q² (cross-validated correlation coefficient) [1] [6]

- External validation: Predictive ability on an independent test set, reported as R²pred [6] [5]

- Statistical significance: Conventional correlation coefficient (R²), Fisher ratio (F-value), and standard error of estimate (SEE) [9] [6]

Table 2: Statistical Benchmarks for Robust 3D-QSAR Models in Tumor Inhibitor Design

| Statistical Parameter | Threshold for Predictive Model | Exemplary Values from Recent Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Q² (LOO Cross-Validation) | >0.5 | 0.628 (CoMFA, Dihydropteridone derivatives) [9], 0.666 (CoMSIA, Quinazolin-4(3H)-one analogs) [6] |

| R² (Conventional Correlation) | >0.8 | 0.928 (CoMFA, Dihydropteridone derivatives) [9], 0.982 (CoMSIA, Quinazolin-4(3H)-one analogs) [6] |

| R²pred (External Test Set) | >0.5 | 0.681 (CoMSIA, Quinazolin-4(3H)-one analogs) [6], 0.722 (CoMSIA, Phenylindole derivatives) [5] |

| Number of Components | Should be <⅓ training set compounds | 3-6 typical for datasets of 20-40 compounds [9] [6] |

The validated model is interpreted through 3D contour maps that visualize regions where specific molecular properties enhance or diminish biological activity. For example, green contours in CoMFA steric maps indicate regions where bulkier substituents increase activity, while yellow contours suggest steric hindrance [1]. Similarly, blue and red contours in electrostatic maps identify regions favoring positive or negative charges, respectively [3].

Case Studies: 3D-QSAR Successes in Tumor Inhibitor Design

Dihydropteridone Derivatives as PLK1 Inhibitors for Glioblastoma

A 2023 study demonstrated the power of integrated 2D and 3D-QSAR approaches for designing dihydropteridone derivatives as Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibitors for glioblastoma treatment [9]. The 3D-QSAR model exhibited excellent statistical parameters (Q²=0.628, R²=0.928), outperforming both linear and nonlinear 2D models. The most significant 2D descriptor, "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN), combined with hydrophobic field information from 3D-QSAR, guided the design of compound 21E.153, which exhibited outstanding antitumor properties and docking capabilities [9].

Quinazolin-4(3H)-one Analogs as EGFR Inhibitors for Breast Cancer

In breast cancer research, CoMFA and CoMSIA models were developed for quinazolin-4(3H)-one analogs as EGFR inhibitors [6]. The optimal CoMSIA model incorporating steric, hydrophobic, and electrostatic fields (CoMSIA_SHE) showed strong predictive power (Q²=0.666, R²=0.982, R²pred=0.681). The contour maps guided the design of five novel compounds with predicted pIC₅₀ values of 5.62 to 6.03, which molecular docking confirmed had superior binding affinities compared to the reference drug Gefitinib [6].

Phenylindole Derivatives as Multi-Target Cancer Inhibitors

A 2025 study showcased 3D-QSAR's application in multi-target therapy, developing phenylindole derivatives as simultaneous inhibitors of CDK2, EGFR, and tubulin [5]. The CoMSIA model demonstrated high reliability (R²=0.967, Q²=0.814) and successfully guided the design of six new compounds with improved binding affinities (-7.2 to -9.8 kcal/mol) across all three targets compared to reference compounds. This approach addresses the critical challenge of drug resistance in cancer therapy through simultaneous multi-target inhibition [5].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR in Tumor Inhibitor Design

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Software | Primary Function in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Building & Visualization | ChemDraw [9], ChemOffice [10] | 2D structure creation and initial editing |

| Molecular Modeling & Optimization | Sybyl [6] [5], HyperChem [9] [7], Spartan [6], Gaussian [10] | 3D structure generation, geometry optimization, conformational analysis |

| Quantum Chemical Calculations | Gaussian [10], DFT methods (B3LYP/6-31G*) [6] [10] | High-accuracy electronic structure calculation for descriptor generation |

| 3D-QSAR Specific Platforms | SYBYL-X [6] [5], Open3DQSAR | CoMFA, CoMSIA, and other 3D-QSAR analyses |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock [7], AutoDock Vina [7], Molegro Virtual Docker [6] | Bioactive conformation prediction, binding mode analysis |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM [7] | Validation of binding stability and conformational sampling |

| ADMET Prediction | SwissADME [6], pkCSM [6] | Pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiling of designed compounds |

The evolution from 2D to 3D-QSAR represents a paradigm shift in tumor inhibitor design, moving from abstract numerical descriptors to spatially intuitive molecular fields that directly inform medicinal chemistry optimization. By explicitly accounting for steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic interactions, 3D-QSAR provides a rational framework for designing compounds with enhanced binding affinity, selectivity, and therapeutic potential against challenging oncology targets.

The integration of 3D-QSAR with complementary computational approaches – particularly molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and ADMET profiling – creates a powerful multidisciplinary pipeline for accelerated anticancer drug discovery [4] [10] [5]. As 3D-QSAR methodologies continue to evolve, incorporating more sophisticated machine learning algorithms and enhanced conformational sampling techniques, their impact on tumor inhibitor design is poised to grow, potentially addressing persistent challenges in cancer therapy such as drug resistance and metastasis.

For researchers embarking on 3D-QSAR studies for tumor inhibitors, success hinges on meticulous attention to each step of the workflow – from careful dataset curation and biologically relevant alignment to rigorous validation and thoughtful contour map interpretation. When executed with scientific rigor, 3D-QSAR transitions from a predictive tool to an indispensable guide for molecular design, directly contributing to the development of next-generation cancer therapeutics.

The discovery and optimization of novel tumor inhibitors demand computational methods that accurately capture the essence of molecular recognition. Field-based approaches provide a powerful framework for this task by describing molecules not merely by their atomic structure, but by the forces they exert on their biological targets. Central to this methodology is the concept that a molecule's biological activity is determined by its interaction with a protein binding site, mediated through electrostatic, steric, and hydrophobic fields [11].

This technical guide details the core principles of molecular fields, field points, and the eXtended Electron Distribution (XED) force field, providing a foundation for researchers applying field-based 3D-QSAR to the development of tumor inhibitors. These principles enable the meaningful comparison of diverse chemical scaffolds—a critical capability for overcoming drug resistance through scaffold hopping and activity optimization [11].

Core Theoretical Principles

The Molecular Interaction Potential (MIP)

The most important factor affecting molecular recognition is electrostatics, though it is also influenced by shape and hydrophobicity [11]. Cresset's technology describes the electrostatic environment around a ligand or protein as a Molecular Interaction Potential (MIP).

- Definition: The MIP is a scalar field where the value at each point in space is the interaction energy of a charged probe atom (with the van der Waals parameters of oxygen) with the molecule [11].

- Significance: The MIP describes all energetically important interactions a ligand can make with a protein. Viewing the MIP provides clear insights into why some ligands bind more strongly than others [11].

- Comparative Power: Describing molecules in terms of electrostatics rather than structure enables sensible comparison of molecules from different series, facilitating scaffold hopping and lead identification [11].

Field Points: A Compact Representation of Molecular Fields

Dealing with a full 3D scalar potential is computationally challenging. Cresset's solution is to identify the maxima and minima of the fields, termed 'field points' [11].

- Definition: Field points are the spatial extrema of a molecule's MIP. The set of field points is uniquely defined for any given molecular conformation and is usually displayed as colored spheres, where the visual extent of each sphere corresponds to the magnitude of the field [11].

- Computational Advantage: This representation avoids the issues of gauge variance and grid spacing irreproducibility associated with sampling values on a grid [11].

- Interpretation: Each field point represents a location where the molecule can make a locally maximal electrostatic interaction with another molecule. The pattern of field points is consistent with the distribution of H-bond donors and acceptors observed in small molecule crystal structures [11].

The XED Force Field: Accurate Electrostatics for Molecular Modeling

Underpinning the calculation of fields and field points is the XED force field. Traditional force fields use the Atom-Centred Charge (ACC) approximation, which models electrostatics using a set of point partial charges placed on atomic nuclei [11]. This approach performs poorly when describing the electrostatic potential near the molecular surface because it cannot represent key features like lone pairs, pi orbitals, and sigma holes [11].

The XED force field addresses these limitations through a more sophisticated approach.

- Core Innovation: XED uses a complex description of atoms, placing additional monopole points, or eXtended Electron Distributions (XEDs), around atoms. These are treated within the force field as atoms with zero van der Waals radii and can move under the influence of external electrostatic potentials, allowing direct modeling of polarizability [11].

- Key Capabilities:

- Correctly models substituent effects on aromatics and charge density changes in complex aromatics [11].

- Reproduces intermolecular interactions of small molecules, water, and proteins with high accuracy [11].

- Models the anomeric effect and halogen bonding (including the 'sigma hole' in heavier halogens) without requiring specific torsional parameters [11].

- Parameterization: Unlike many force fields, XED is parameterized where possible against experimental data (e.g., microwave conformation energies, small molecule crystal structures) rather than relying purely on ab initio calculations [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Electrostatic Modeling Approaches in Force Fields

| Feature | Traditional Force Fields (AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS) | XED Force Field |

|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic Model | Atom-Centered Charges (ACC) | eXtended Electron Distributions (XED) |

| Polarizability | Typically not included | Explicitly included |

| Anisotropic Effects (e.g., lone pairs, π-orbitals) | Poorly represented | Accurately represented |

| Aromatic-Aromatic Interactions | Limited accuracy | Quantitatively superior |

| Parameterization Basis | Often ab initio calculations | Primarily experimental data |

Computational Methodologies and Workflows

Calculating Molecular Fields and Field Points

The process of deriving fields and field points from a molecular structure follows a defined protocol.

- System Preparation: The 3D structure of the molecule is prepared, and formal charge states are correctly assigned using a complex rule-based system designed to assign the protonation state for most drug-like molecules at pH 7 [11].

- Electrostatic Calculation: The electrostatic potential around the molecule is calculated using the XED force field. A charged probe atom is placed at points in space, and its interaction energy with the molecule is computed. For efficiency, the ligand is not repolarized for every probe position, but the force field parameterization accounts for this to ensure accurate field patterns [12].

- Dielectric Treatment: A key consideration is the dielectric environment. Cresset uses an effective dielectric of 4 for neutral parts of a molecule to simulate a protein-ish environment. For charged groups, a higher dielectric of 32 is used to prevent the charge from swamping the electrostatic potentials from the rest of the molecule, approximating the presence of a counterion or solvation shell [12].

- Field Point Identification: The algorithm identifies the spatial extrema (maxima and minima) of the calculated electrostatic field. These are the field points, which are visualized as colored spheres (e.g., red for negative, blue for positive) [11].

Field Similarity and Molecular Alignment

A patented method is used to compare the molecular interaction potentials of two molecules and compute a field similarity score [11].

- Similarity Calculation: The fields of two molecules are compared at the locations where one of them has a field point. This ensures the field is computed only where at least one conformation suggests the field is important, balancing computational efficiency and accuracy [11].

- Alignment Optimization: To find the optimal alignment between two molecules, a set of initial alignments is generated by computing colored clique matches between the sets of field points on the two conformations. Each clique match determines an alignment by least-squares fitting of the matching field points in 3D. The alignments are then scored using the field similarity algorithm [11].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for generating and using field points in molecular comparison.

Application in 3D-QSAR for Tumor Inhibitor Research

Field-based concepts are directly implemented in 3D-QSAR techniques like CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) and CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis), which are pivotal in modern anti-cancer drug discovery [13] [5] [14].

Integration with 3D-QSAR

In a 3D-QSAR workflow, molecular fields are the fundamental descriptors.

- Field Descriptors: Molecules in a training set are aligned, and their steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields are sampled on a 3D grid [5] [14].

- Model Building: Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is used to correlate the field values at each grid point with the biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀) of the compounds [5]. The resulting model identifies regions in space where specific field properties (e.g., increased steric bulk or a positive charge) are favorable or unfavorable for activity.

- Model Validation: The reliability of a 3D-QSAR model is assessed using cross-validation (reported as Q²) and the coefficient of determination (R²). A model with Q² > 0.5 and R² > 0.9 is generally considered robust and predictive [5].

Case Study: Designing Bcr-Abl Inhibitors for Leukemia

A 2025 study on purine-based Bcr-Abl inhibitors for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) exemplifies this approach [13].

- Challenge: Overcoming the T315I mutation in Bcr-Abl, which confers resistance to imatinib and other front-line therapies [13].

- Method: Researchers constructed 3D-QSAR models using a database of 58 purine inhibitors. The models correlated the steric and electrostatic potentials of the compounds with their Bcr-Abl inhibition (pIC₅₀) [13].

- Outcome: The contour maps from the 3D-QSAR models guided the design of new purine derivatives. Compounds 7a and 7c demonstrated higher potency (IC₅₀ = 0.13 and 0.19 μM) than imatinib (IC₅₀ = 0.33 μM). Crucially, compounds 7e and 7f showed greater sensitivity against imatinib-resistant KCL22-B8 cells (expressing Bcr-Abl[T315I]) than imatinib itself [13].

Table 2: Key Experimental Results from Purine-Based Bcr-Abl Inhibitor Study [13]

| Compound | Bcr-Abl IC₅₀ (μM) | Potency vs. Imatinib | Activity vs. T315I Mutant (KCL22-B8 cells) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imatinib | 0.33 | Reference | GI₅₀ > 20 μM |

| 7a | 0.13 | ~2.5x more potent | N/A |

| 7c | 0.19 | ~1.7x more potent | N/A |

| 7e | N/A | N/A | GI₅₀ = 13.80 μM |

| 7f | N/A | N/A | GI₅₀ = 15.43 μM |

Table 3: Key Software and Tools for Field-Based 3D-QSAR Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevant URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cresset Flare | Software Platform | Structure-based drug design platform that implements the XED force field for calculating fields, field points, and performing FEP, WaterSwap, and dynamics simulations. | cresset-group.com |

| 3D-QSAR.com | Online Platform | Web application for developing ligand-based and structure-based 3D-QSAR models. | 3d-qsar.com |

| Open Force Field Consortium | Consortium/Initiative | Develops next-generation, open-source force fields for molecular simulation, such as the "Parsley" force field. | openforcefield.org |

| SYBYL | Software Suite | A comprehensive molecular modeling software package that includes modules for CoMFA and CoMSIA. | N/A |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, essential for structure-based alignment. | rcsb.org |

The principles of molecular fields, field points, and advanced force fields like XED form a rigorous scientific foundation for rational drug design. By focusing on the biologically relevant forces a molecule exerts, these methods enable researchers to transcend simple structural comparisons, directly addressing the challenge of optimizing activity and overcoming resistance in tumor inhibitor development. The integration of these concepts into 3D-QSAR workflows provides a powerful, predictive framework for accelerating the discovery of novel oncology therapeutics.

The development of targeted cancer therapies relies heavily on understanding and inhibiting key oncogenic signaling pathways. 3D-QSAR (Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship) modeling has emerged as a powerful computational approach in this endeavor, enabling the rational design of small molecule inhibitors by correlating their three-dimensional molecular properties with biological activity. This technical guide explores the application of field-based 3D-QSAR methodologies to three critical pathways in oncology: the JAK-STAT, RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK, and DNA repair pathways. By integrating computational predictions with experimental validation, researchers can accelerate the discovery of novel tumor inhibitors with improved potency and selectivity, ultimately advancing personalized cancer treatment strategies.

3D-QSAR represents a significant advancement over traditional 2D-QSAR methods by incorporating the three-dimensional structural features of molecules and their interaction fields. Unlike classical QSAR that uses numerical descriptors (e.g., logP, molar refractivity), 3D-QSAR utilizes steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields surrounding aligned molecules to build predictive models [1]. This approach is particularly valuable in cancer drug discovery where small structural modifications often lead to significant changes in inhibitory potency against validated oncological targets.

The core premise of 3D-QSAR involves analyzing how the spatial arrangement of molecular features influences binding to biological targets, typically using methods such as Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) [1]. These techniques have proven instrumental in optimizing lead compounds against various kinase targets, including those in the JAK-STAT and RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathways, by providing visual contour maps that guide structural modifications to enhance potency and selectivity.

Key Cancer Signaling Pathways: Biological Significance and Therapeutic Targeting

JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK-STAT pathway is a critical signaling cascade that transmits information from extracellular cytokines to the nucleus, influencing fundamental cellular processes including immune response, cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [15]. The pathway consists of three main components: transmembrane receptors, Janus Kinases (JAKs), and Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (STATs). Four JAK family members (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, TYK2) and seven STAT proteins (STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5a, STAT5b, STAT6) have been identified, with different combinations mediating responses to specific cytokines [15].

Dysregulation of the JAK-STAT pathway, particularly through constitutive activation of STAT3 and STAT5, is strongly associated with autoimmune disorders and various cancers, including leukemias and lymphomas [15]. JAK3 is especially notable as a drug target due to its restricted expression primarily in hematopoietic cells, potentially offering a favorable therapeutic window [16]. The unique presence of Cys909 in JAK3 has been exploited for developing covalent inhibitors, though recent research also focuses on non-covalent inhibitors to minimize off-target effects [16].

Figure 1: JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway Activation. Cytokine binding induces receptor activation, leading to JAK phosphorylation, STAT activation, dimerization, nuclear translocation, and target gene transcription.

RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK Signaling Pathway

The RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway is a conserved MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) cascade that regulates fundamental cellular functions including proliferation, survival, and differentiation [17] [18]. This pathway transmits signals from activated cell surface receptors (e.g., receptor tyrosine kinases) through a series of cytoplasmic kinases ultimately to transcription factors in the nucleus. Aberrant activation of this pathway occurs in approximately one-third of all human cancers, with RAS mutations present in 33% and RAF mutations in 8% of tumors [17].

The pathway begins with RAS activation through GTP binding, which then recruits and activates RAF kinases (ARAF, BRAF, CRAF) [18]. Activated RAF phosphorylates MEK1/2, which in turn phosphorylates and activates ERK1/2. ERK possesses hundreds of substrates in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, enabling it to regulate diverse cellular processes [17] [19]. The high frequency of mutations in this pathway, particularly in KRAS (the most frequent isoform in human cancers) and BRAF (especially the V600E mutation), has made it a prime target for anticancer drug development [17] [18].

Figure 2: RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK Signaling Cascade. Growth factor binding initiates a phosphorylation cascade through RAS, RAF, MEK, and ERK, ultimately regulating transcription factors and cellular processes.

DNA Repair Pathways

DNA repair mechanisms maintain genomic integrity by correcting various types of DNA damage, including base modifications, single-strand breaks, and double-strand breaks. Key pathways include base excision repair (BER), nucleotide excision repair (NER), mismatch repair (MMR), and double-strand break repair (including homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining). Cancer cells often exhibit deficiencies in specific DNA repair pathways, creating therapeutic opportunities through synthetic lethality, as exemplified by PARP inhibitors in BRCA-deficient cancers.

While the search results provided limited specific information on 3D-QSAR applications for DNA repair targets, the principles and methodologies discussed for kinase targets can be directly applied to DNA repair enzymes. The development of inhibitors for DNA repair proteins like PARP, ATM, ATR, and DNA-PK represents an active area of cancer drug discovery where 3D-QSAR approaches can contribute significantly.

3D-QSAR Methodologies: Principles and Workflows

Fundamental Concepts and Descriptors

3D-QSAR methods rely on calculating interaction energies between probe atoms and aligned molecules within a defined grid space. The most established approaches include:

CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis): Calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields using a probe atom placed at grid points surrounding the aligned molecules [1]. Highly sensitive to molecular alignment.

CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis): Extends CoMFA by incorporating hydrophobic and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor fields using Gaussian-type functions, reducing sensitivity to alignment and providing smoother field distributions [1].

The selection of appropriate molecular descriptors is critical for model quality. The table below summarizes key descriptor types used in 3D-QSAR studies for cancer targets.

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptors in 3D-QSAR Studies

| Descriptor Category | Specific Descriptors | Biological Significance | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steric | van der Waals volumes, Shape indices | Molecular bulk, steric hindrance | Optimizing substituents to fill binding pockets |

| Electrostatic | Partial charges, Dipole moments, Molecular electrostatic potentials | Charge-charge interactions, hydrogen bonding | Enhancing ligand-target complementarity |

| Hydrophobic | logP, logD, Partition coefficients | Desolvation, membrane permeability | Improving cellular uptake and bioavailability |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Donor/acceptor counts, H-bond energies | Specificity and binding affinity | Optimizing key interactions with active site residues |

Comprehensive Workflow for 3D-QSAR Model Development

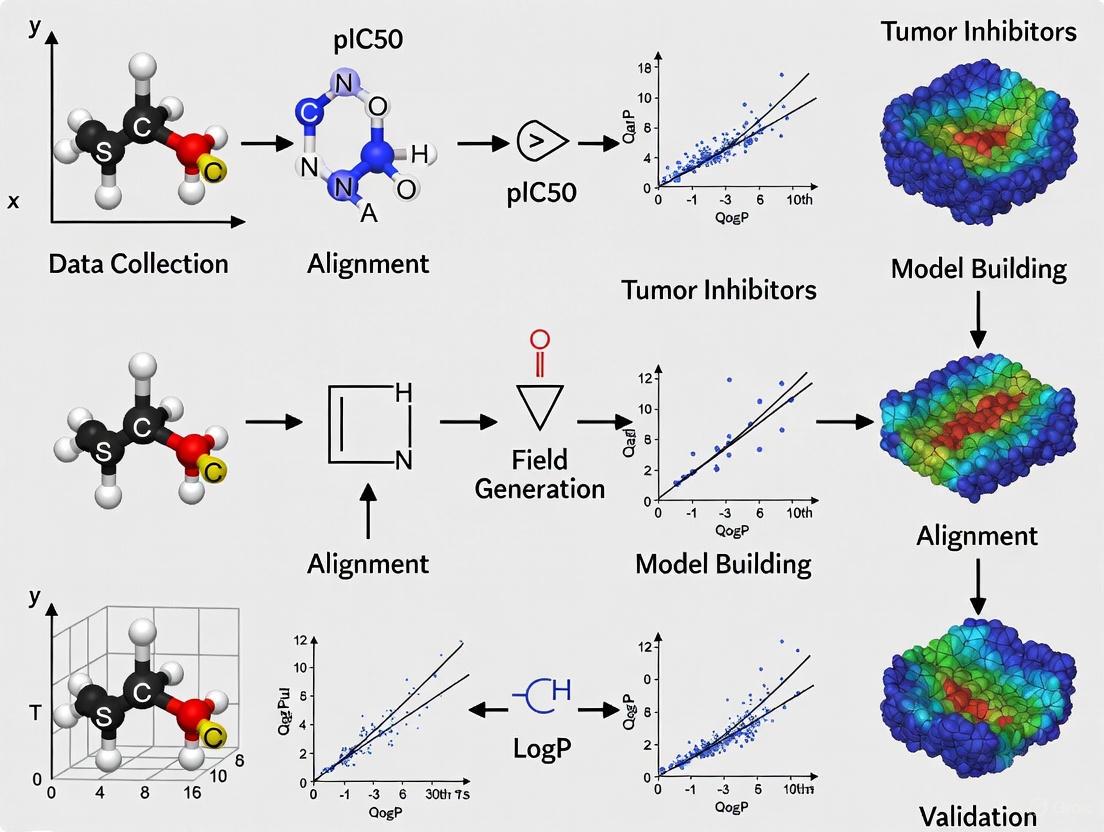

A robust 3D-QSAR workflow involves multiple critical steps from data collection to model application, as illustrated below:

Figure 3: 3D-QSAR Workflow. Key steps include data collection, molecular modeling, alignment, descriptor calculation, model building, validation, interpretation, and compound design.

Data Collection and Preparation: Curate a dataset of compounds with consistently determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀, Kᵢ) spanning 3-4 orders of magnitude [20] [1]. Ensure structural diversity while maintaining a common scaffold for meaningful alignment.

Molecular Modeling and Alignment: Generate energetically optimized 3D conformations using molecular mechanics (e.g., UFF) or quantum mechanical methods [1]. Align molecules based on shared pharmacophoric features or maximum common substructure (MCS), assuming similar binding modes [16] [1].

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building: Calculate steric and electrostatic fields (CoMFA) or additional similarity indices (CoMSIA) for aligned molecules [1]. Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate descriptor fields with biological activity, selecting optimal components to avoid overfitting.

Model Validation and Interpretation: Validate models using leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation (q² > 0.5), external test set prediction (r²ₚᵣₑd > 0.6), and Fischer randomization [20] [16]. Interpret results through 3D contour maps visualizing regions where specific molecular properties enhance or diminish activity.

Applications to Cancer Pathway Inhibition

JAK-STAT Pathway Inhibitors

3D-QSAR has significantly contributed to developing selective JAK inhibitors, particularly for JAK3. A recent study constructed 3D-QSAR models for 73 JAK3 inhibitors with pIC₅₀ values spanning 4 orders of magnitude [16]. The optimal CoMSIA model demonstrated excellent predictive power with q² = 0.52 and r² = 0.91, highlighting key structural features for JAK3 selectivity:

- Hydrophobic moieties at specific positions enhance affinity

- Hydrogen bond acceptors toward certain regions improve selectivity over other JAK isoforms

- Steric bulk in defined areas discriminates against JAK2 binding

The study identified critical residues for selective JAK3 inhibition through molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations, facilitating the design of 10 novel inhibitors with predicted high potency [16]. Similarly, field-based 3D-QSAR for JAK-2 inhibitors achieved strong correlation values (r² = 0.884, q² = 0.67), identifying electronegativity, electropositivity, hydrophobicity, and shape as essential determinants of inhibitory activity [21].

Table 2: Selected 3D-QSAR Studies for JAK-STAT Pathway Inhibitors

| Target | Method | Statistical Parameters | Key Structural Insights | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JAK3 | CoMSIA | q² = 0.52, r² = 0.91 | Hydrophobic moieties and H-bond acceptors critical for selectivity | [16] |

| JAK2 | Field-based 3D-QSAR | r² = 0.884, q² = 0.67 | Electronegativity, electropositivity, hydrophobicity essential | [21] |

| SYK | 3D-QSAR Pharmacophore | - | One H-bond acceptor, three aromatic rings optimal | [20] |

RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK Pathway Inhibitors

The RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway presents multiple targeting opportunities, with 3D-QSAR applications focusing predominantly on RAF and MEK inhibition. Although the search results don't provide detailed 3D-QSAR statistics for this pathway specifically, the successful application of these methods to kinase targets in general suggests strong potential.

Recent efforts have yielded covalent KRASG12C inhibitors like sotorasib (AMG510) and adagrasib (MRTX849), approved for KRASG12C-mutant cancers [17]. While not explicitly detailing 3D-QSAR in their development, these breakthroughs demonstrate the importance of structural optimization approaches that 3D-QSAR facilitates. Resistance mechanisms to these agents highlight the need for continued inhibitor optimization, where 3D-QSAR can contribute significantly.

The pathway's complexity, including feedback regulation and crosstalk with PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, presents challenges that 3D-QSAR approaches can address by designing inhibitors with appropriate polypharmacology or combination therapy strategies [17] [19].

Experimental Protocols and Technical Approaches

Detailed 3D-QSAR Protocol for Kinase Inhibitors

Dataset Curation

- Select 20-100 compounds with consistently measured inhibitory activities (IC₅₀) from the same biological assay [20]

- Ensure activity range of 3-4 log units for robust model building

- Divide compounds into training (70-80%) and test sets (20-30%) using structural diversity and activity distribution criteria

Molecular Modeling and Alignment

- Generate 3D structures from 2D representations using tools like RDKit or Sybyl [1]

- Optimize geometries using molecular mechanics (UFF) or semi-empirical methods (AM1)

- Align molecules to a common reference frame using:

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) approach

- Pharmacophore-based alignment

- Dock-based alignment using a protein structure if available

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building

- Calculate CoMFA steric and electrostatic fields using sp³ carbon probe with +1 charge

- Compute CoMSIA similarity indices for steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and H-bond donor/acceptor fields

- Perform Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression with cross-validation to determine optimal components

- Validate model robustness using leave-one-out (LOO) and leave-many-out cross-validation

Model Application and Compound Design

- Visualize results as 3D contour maps showing favorable/unfavorable regions for steric bulk and electrostatic properties

- Design new analogs incorporating structural features predicted to enhance activity

- Synthesize and test top candidates to validate model predictions

Table 3: Essential Resources for 3D-QSAR Studies in Cancer Pathway Inhibition

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Software | SYBYL, Discovery Studio, RDKit | Molecular modeling, descriptor calculation | Force field implementation, QSAR module integration |

| 3D-QSAR Specialized Tools | CoMFA, CoMSIA modules | Field calculation, contour map generation | Steric/electrostatic field computation, PLS analysis |

| Molecular Dynamics | AMBER, GROMACS | Binding mode validation, stability assessment | Free energy calculations, trajectory analysis |

| Protein Data Sources | RCSB PDB | Structural templates for alignment | Experimentally determined protein-ligand complexes |

| Compound Databases | ZINC, PubChem | Virtual screening, lead identification | Diverse chemical libraries, availability information |

3D-QSAR methodologies represent powerful approaches for rational inhibitor design against key cancer pathways like JAK-STAT and RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK. By correlating three-dimensional molecular properties with biological activity, these computational techniques provide valuable insights for optimizing potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties. The integration of 3D-QSAR with complementary approaches like molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations enhances predictive accuracy and mechanistic understanding.

Future directions in this field include the incorporation of machine learning algorithms for descriptor selection and model building [22], application to covalent inhibitor design through specialized reaction field descriptors, and addressing compound promiscuity by modeling off-target effects. Additionally, the development of 3D-QSAR models for emerging cancer targets in DNA repair pathways represents a promising avenue for expanding the utility of these methods in oncological drug discovery.

As structural biology and computational power continue to advance, 3D-QSAR approaches will play an increasingly vital role in translating pathway knowledge into effective targeted therapies, ultimately contributing to more personalized and effective cancer treatments.

Field-based Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has become an indispensable technique in modern computational oncology for designing and optimizing novel tumor inhibitors. Unlike traditional 2D-QSAR methods that use numerical molecular descriptors, 3D-QSAR considers the crucial three-dimensional spatial orientation of molecules, providing insights into how steric (shape-related) and electrostatic fields surrounding a molecule influence its biological activity against cancer targets [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding and overcoming drug resistance mechanisms in cancer therapy, as it allows researchers to visualize specific molecular regions where structural modifications can enhance binding affinity to therapeutic targets [23].

The predictive power and practical utility of 3D-QSAR models fundamentally depend on two critical factors: the quality of specialized software platforms and the rigorous application of validated computational protocols. Software tools enable the accurate calculation of molecular interaction fields, proper alignment of compound datasets, and generation of statistically robust models that can reliably predict the activity of newly designed compounds before costly synthetic efforts [1] [14]. For researchers focusing on tumor inhibitors, mastering these computational tools provides a strategic advantage in accelerating the drug discovery pipeline from initial hit identification to lead optimization stages.

Core 3D-QSAR Methodology and Experimental Protocols

Fundamental Workflow

The construction of a predictive 3D-QSAR model follows a systematic workflow with several interdependent stages. Adherence to this protocol ensures the generation of chemically meaningful and statistically significant models suitable for guiding cancer drug discovery efforts.

Data Collection and Preparation: The process begins with assembling a dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀ or Kᵢ values) measured against the cancer target of interest under consistent assay conditions [1]. Activity values are typically converted to negative logarithmic scales (pIC₅₀ = -logIC₅₀) to create a linearly distributed dependent variable for modeling [24]. The dataset should contain structurally related compounds with sufficient diversity to capture meaningful structure-activity relationships, typically divided into training (for model building) and test (for model validation) sets [24] [25].

Molecular Modeling and Conformational Analysis: 2D chemical structures are converted to 3D representations and subjected to geometry optimization using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., Tripos or MMFF94) or quantum mechanical methods to identify low-energy conformations [1] [24]. For each compound, multiple conformations may be generated and evaluated to identify the putative bioactive conformation, which is often the global energy minimum or a low-energy state compatible with binding [25].

Molecular Alignment: This critical step superimposes all molecules in a common 3D coordinate system that reflects their putative binding orientation at the target site [1]. Alignment methods include:

- Pharmacophore-based alignment: Using common chemical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic centers, aromatic rings) [25]

- Database alignment: Superimposing compounds onto a known active template or reference structure [26]

- Docking-based alignment: Using molecular docking poses to orient compounds within a protein active site [14]

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS): Identifying and aligning the largest shared structural framework [1]

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building: Following alignment, 3D molecular field descriptors are calculated at grid points surrounding the molecules. In Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields are computed using a probe atom [1]. Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extends this approach by incorporating additional fields (hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor) using Gaussian-type functions for smoother potential maps [1] [24]. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is then used to correlate the field descriptors with biological activity, addressing the high dimensionality and multicollinearity of the descriptor matrix [1] [25].

Model Validation and Interpretation: Rigorous validation assesses model robustness and predictive power. Internal validation uses techniques like Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation, generating cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) [25]. External validation tests the model on an independent test set not used in training [24]. Statistical metrics include conventional correlation coefficient (r²), standard error of estimate, and F-value [24]. The final model is visualized as 3D contour maps showing regions where specific molecular properties (steric bulk, electropositive/electronegative groups) enhance or diminish biological activity [1].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive 3D-QSAR modeling workflow, from initial data preparation to final model application in drug design:

Critical Experimental Parameters and Validation Metrics

Successful 3D-QSAR implementation requires careful attention to technical parameters and validation standards. The table below summarizes key metrics and their acceptable ranges for robust models:

| Parameter Category | Specific Metric | Acceptable Range/Value | Technical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Quality | Regression coefficient (r²) | >0.8 [24] [25] | Measures goodness-of-fit of the model to training data |

| Cross-validated r² (q²) | >0.5 [24] [25] | Indicates predictive power through internal validation | |

| Number of PLS components | Optimized to avoid overfitting [25] | Latent variables capturing variance in descriptor-activity relationship | |

| Data Preparation | Training set size | ≥20 compounds [25] | Ensures sufficient statistical power for model development |

| Test set size | ~20-25% of total dataset [24] | Provides independent validation of model predictability | |

| Activity range | ≥4 orders of magnitude [27] | Ensures adequate dynamic range for meaningful SAR | |

| Field Parameters | Grid spacing | 1.0-2.0 Å [25] | Resolution for molecular field calculations |

| Probe atom type | sp³ carbon with +1 charge [1] | Standard for steric and electrostatic field calculations |

Essential Software Platforms

Specialized software platforms provide the computational infrastructure necessary for implementing the 3D-QSAR workflow described above. The table below summarizes the core capabilities, key features, and typical applications of major commercial and academic platforms relevant to tumor inhibitor research:

| Software Platform | Core Capabilities | Key Features for 3D-QSAR | Application in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forge (Cresset) | Field-based molecular alignment, Activity Atlas, 3D-QSAR model building [25] | FieldTemplater for pharmacophore generation, XED force field, Field-QSAR with PLS regression [25] | Maslinic acid analogs against breast cancer MCF-7 cells (r²=0.92, q²=0.75) [25] |

| SYBYL (Tripos) | Comprehensive molecular modeling, CoMFA, CoMSIA, molecular docking [24] | CoMFA steric/electrostatic fields, CoMSIA with multiple field types, Region Focusing [24] | Anthraquinone derivatives as PGAM1 inhibitors (CoMFA: q²=0.81, r²=0.97) [24] |

| Schrödinger | Integrated drug discovery platform, FEP, MM/GBSA, molecular dynamics [28] | Advanced chemical descriptors, QM-Polarized Ligand Docking, Free energy calculations [28] | Predictive modeling for kinase inhibitors and oncology targets [28] |

| MOE (CCG) | Molecular modeling, simulations, cheminformatics, QSAR, structure-based design [28] | Pharmacophore query development, conformational analysis, descriptor calculation [28] | ADMET prediction, protein engineering for cancer targets [28] |

| ICM (Molsoft) | Biological system modeling, docking, virtual screening, 3D-QSAR [26] | APF (Atomic Property Fields), flexible superposition to template, PLS regression [26] | Thyroid Hormone Receptor Alpha (THRA) inhibitors [26] |

Platform Selection Criteria

Choosing the appropriate software platform depends on several factors specific to the research objectives and available resources:

Research Stage: For lead optimization with established structure-activity relationships, Forge's field-based approaches offer intuitive visualization. For scaffold hopping and novel chemical matter identification, SYBYL's CoMSIA handles diverse datasets effectively [1] [25].

Target Information Availability: When protein structure information is available, integrated platforms like Schrödinger that combine 3D-QSAR with docking and molecular dynamics provide enhanced insights. For strictly ligand-based studies, Forge and SYBYL offer specialized functionality [14] [28].

Computational Resources: Desktop solutions like Forge and SYBYL are suitable for individual researchers, while enterprise platforms like Schrödinger offer scalable solutions for team-based drug discovery programs [28].

Validation Requirements: Platforms with built-in statistical validation protocols and automated permutation testing ensure model robustness, particularly important for regulatory applications in drug development [24] [25].

Case Studies and Research Applications

Tumor Inhibitor Development Examples

The practical application of 3D-QSAR software in cancer research is illustrated through these representative case studies:

Breast Cancer Inhibitors from Maslinic Acid Analogs: Researchers used Forge software to develop a 3D-QSAR model for maslinic acid analogs tested against MCF-7 breast cancer cells [25]. The study employed FieldTemplater to identify a common pharmacophore from active compounds, followed by field-based alignment of 74 compounds. The resulting model showed excellent statistical parameters (r²=0.92, q²=0.75) and identified key steric and electrostatic features controlling anticancer activity. Virtual screening of a natural product database followed by ADMET filtering identified compound P-902 as a promising candidate, subsequently validated through docking studies against multiple breast cancer targets [25].

PGAM1 Inhibitors for Cancer Metabolism Therapy: In a study targeting phosphoglycerate mutase 1 (PGAM1), a key enzyme in cancer metabolism, researchers utilized SYBYL to perform both CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses on anthraquinone derivatives [24]. The models demonstrated high predictive power (CoMFA: q²=0.81, r²=0.97; CoMSIA: q²=0.82, r²=0.96) and contour maps revealed structural requirements for PGAM1 inhibition. Molecular dynamics simulations validated the binding modes of newly designed compounds, with specific residues (F22, K100, V112, W115, R116) identified as critical for inhibitor binding [24].

NAMPT Inhibitors for Cancer Therapy: A field-based 3D-QSAR study on amide- and urea-containing NAMPT inhibitors employed docking-based alignment to generate predictive models [14]. The optimized model successfully identified key molecular interactions with active site residues, enabling rational design of novel inhibitors with potential applications against various cancers dependent on the NAD+ salvage pathway [14].

Integrated Computational Approaches

Modern 3D-QSAR studies increasingly combine multiple computational techniques to enhance predictive accuracy and mechanistic understanding:

3D-QSAR with Molecular Dynamics: Integration of 3D-QSAR with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations allows for incorporation of protein flexibility and explicit solvent effects. In the SYK kinase inhibitor study, 3D-QSAR pharmacophore models were used for virtual screening, with MD simulations providing validation of binding stability and key protein-ligand interactions [27].

3D-QSAR with Free Energy Calculations: Advanced platforms like Schrödinger incorporate free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations to refine 3D-QSAR predictions with rigorous thermodynamic binding estimates [28].

The following diagram illustrates how these computational techniques integrate into a comprehensive drug discovery workflow for tumor inhibitor development:

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of 3D-QSAR studies requires both computational tools and conceptual "research reagents" - the fundamental components and data resources that form the foundation of reliable models.

| Research Reagent | Function in 3D-QSAR | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Bioactivity Data | Provides experimental activity values for model training and validation | IC₅₀ values from uniform bioassays [24] [25]; pKd values from binding assays [26] |

| Molecular Force Fields | Calculates molecular energies and optimizes 3D geometries | Tripos force field [24]; XED force field [25]; Universal Force Field (UFF) [1] |

| Structural Templates | Provides reference frameworks for molecular alignment | Known active compounds [25]; Protein Data Bank structures [26]; Pharmacophore hypotheses [27] |

| Chemical Descriptors | Numerically represents molecular properties for QSAR | Steric and electrostatic field points [1] [25]; Similarity indices [1]; Quantum chemical parameters [28] |

| Validation Protocols | Assesses model robustness and predictive power | Leave-One-Out cross-validation [25]; Test set prediction [24]; Fisher randomization [27] |

Field-based 3D-QSAR methodologies, implemented through sophisticated software platforms like Forge, SYBYL, and their counterparts, provide powerful capabilities for rational design of tumor inhibitors. The integration of these computational approaches with experimental validation creates an iterative cycle of compound optimization that significantly accelerates oncology drug discovery. As these platforms continue to evolve with enhanced AI capabilities, improved force fields, and more intuitive interfaces, their impact on overcoming cancer drug resistance and identifying novel therapeutic strategies will undoubtedly expand. For research teams engaged in tumor inhibitor development, strategic investment in both the computational tools and expertise required for 3D-QSAR modeling represents a valuable approach to addressing the persistent challenge of cancer drug discovery.

The discovery and optimization of tumor inhibitors represent a critical frontier in the battle against cancer. Among the modern computational techniques employed, field-based Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has emerged as a powerful tool for rational drug design. This methodology correlates the three-dimensional structural and field properties of compounds with their biological activity against specific oncology targets, enabling the prediction and design of more potent inhibitors. The reliability of any 3D-QSAR model is fundamentally contingent on the quality, consistency, and appropriate preparation of the underlying data. This guide details the core data requirements—encompassing compound selection, activity data curation, and structural preparation—essential for initiating robust 3D-QSAR studies focused on tumor inhibitors.

Compound Selection and Dataset Curation

The initial and perhaps most crucial step in a 3D-QSAR study is the assembly of a high-quality dataset of inhibitory compounds.

Sourcing and Selection Criteria

Information on kinase inhibitor activity can be retrieved from public chemical and bioactivity databases such as ChEMBL, BindingDB, and Excape [29]. When selecting compounds from these sources, researchers should apply stringent criteria. For instance, in a study on RET kinase inhibitors, the selection was refined to data from wild-type, non-cell-based assays where the inhibitory concentration (IC50) was measured in nanomolar (nM) units [29]. This ensures data homogeneity. Furthermore, compounds with activity annotations featuring blank fields or values containing “<” or “>” should typically be excluded to maintain data integrity [29].

The selected compounds should be structurally related to ensure coherent modeling, yet sufficiently diverse to capture meaningful structure-activity relationships [1]. A common strategy involves focusing on a specific chemotype or core structure that interacts with a key region of the target protein. For example, many selective RET inhibitors share a 5,6-fused bicyclic ring that acts as a hinge binder, making this a suitable scaffold for building a focused dataset [29].

Dataset Division for Modeling and Validation

Once a curated dataset is assembled, it must be divided into a training set and a test set. The training set is used to build the QSAR model, while the test set is reserved for an external validation of its predictive power. A common practice is to use a 3:1 or 9:1 ratio for the training and test sets, respectively [29] [30]. The division should be performed via random selection, sometimes with the additional step of grouping compounds into high, medium, and low activity bands first to ensure the test set is representative of the entire activity range [30].

Table 1: Public Databases for Sourcing Tumor Inhibitor Data

| Database Name | Primary Content | Utility in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [29] | Bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, curated from scientific literature. | A primary source for consistent bioactivity data (e.g., IC50) for a wide range of oncology targets. |

| BindingDB [29] | Binding affinities for protein-ligand complexes. | Provides binding data useful for modeling receptor-ligand interactions. |

| Excape [29] | Database of chemical structures and associated biological activities. | Another source for retrieving compound and activity data for dataset building. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [5] | 3D structural data for biological macromolecules. | Source of crystal structures for molecular docking and receptor-guided alignment. |

Diagram 1: Compound selection and curation workflow.

Activity Data: Measurement and Transformation

Biological activity data is the dependent variable in any QSAR model and must be handled with care to ensure statistical soundness.

Activity Measurements and Conversion

The most common measurement for inhibitory activity is the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), typically reported in molar units (e.g., nM, µM) [29] [6]. To minimize skewness and linearize the relationship between the concentration and the modeled response, IC50 values are converted into their negative logarithmic form, pIC50, using the following formula [29] [6]: pIC50 = –log10(IC50) In practice, to handle unit conversion seamlessly, the formula is often expressed as: pIC50 = 9 – log(IC50) for IC50 values in nM [29], or pIC50 = –log10(IC50 × 10⁻⁶) for IC50 values in µM [6]. This transformation results in a positive value where a higher pIC50 indicates greater potency.

Data Uniformity and Integrity

All activity data for the training set must be acquired under uniform experimental conditions [1]. Variability in assay protocols (e.g., cell-based vs. non-cell-based, different cell lines) introduces unwanted noise and systemic bias, which can severely compromise the predictive value and interpretability of the final QSAR model.

Table 2: Biological Activity Data Handling in 3D-QSAR

| Data Aspect | Description | Best Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Activity Type | Direct measure of compound potency (e.g., IC50, Ki). | Use IC50 values from consistent, biochemical, non-cell-based assays for initial model development [29]. |

| Value Transformation | Converting IC50 to pIC50 for modeling. | Apply the formula pIC50 = -log10(IC50) to create a linear, normally-distributed response variable [29] [6]. |

| Data Integrity | Handling of incomplete or uncertain data. | Exclude compounds with activity annotations containing ">", "<", or blank fields to ensure a reliable dataset [29]. |

| Experimental Consistency | Ensuring data is generated from comparable assays. | Collect all activity data from the same type of assay (e.g., wild-type, non-cell-based) under standardized conditions [29] [1]. |

Structural Preparation and Molecular Modeling

The accurate generation and preparation of 3D molecular structures form the foundation for all subsequent alignment and descriptor calculation steps.

Generation of 3D Structures and Conformer Sampling

The process typically begins with two-dimensional (2D) structural sketches, which are created using software like PerkinElmer ChemDraw [6]. These 2D structures are then converted into three-dimensional coordinates using molecular modeling packages such as Spartan or Schrödinger's LigPrep [6] [29]. This 2D-to-3D conversion may include options for neutralizing compounds and generating possible states or tautomers [29].

The resulting initial 3D structures are not necessarily in their lowest energy or bioactive conformation. Therefore, they must undergo geometry optimization. This can be achieved using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., Tripos force field, OPLS3e, or the Universal Force Field (UFF)) or, for higher accuracy, quantum mechanical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) with a basis set such as B3LYP/6-31G* [6] [29] [1]. Since molecules are flexible, generating multiple low-energy conformers for each compound is often necessary to account for flexibility and aid in identifying the putative bioactive conformation [1].

Molecular Docking for Receptor-Guided Alignment

A powerful approach for structural preparation, especially when a protein crystal structure is available, is molecular docking. It is used to pose compounds into the target's binding site, providing a receptor-guided alignment for 3D-QSAR [29]. The general protocol involves:

- Protein Preparation: A crystal structure of the target (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank) is prepared by adding hydrogen atoms, removing unnecessary chains and water molecules, and correcting any faulty amino acid residues. The protein structure is then minimized using a force field like OPLS3e to an acceptable RMSD (e.g., 0.3 Å) [29].

- Grid Generation: A grid box is defined around the centroid of the native ligand or the known binding site.

- Ligand Docking: The prepared ligands are docked into the binding site using software like Glide [29]. The docking pose that forms key interactions with hinge region residues (e.g., hydrogen bonds with ALA807 or GLU805 in RET kinase) is often selected for QSAR modeling [29]. The docking model itself must be validated by redocking the native crystal ligand and calculating the RMSD between the redocked and original poses [29].

Diagram 2: Structural preparation and alignment workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR of Tumor Inhibitors

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Function in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| KNIME [29] | Data Analytics Platform | Used for data curation, compilation, and preprocessing of compounds and activity data from various sources. |

| Schrödinger Suite (LigPrep, Glide, Maestro) [29] [31] | Molecular Modeling Software | Provides an integrated environment for ligand preparation (LigPrep), molecular docking (Glide), and field-based QSAR model building and visualization. |

| Sybyl/SYBYL-X [6] [5] | Molecular Modeling Software | A classic software package for conducting CoMFA and CoMSIA studies, including molecular alignment and PLS analysis. |

| RDKit [1] | Cheminformatics Library | An open-source toolkit for cheminformatics, useful for 2D-to-3D conversion, molecular alignment, and descriptor calculation. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [5] | Structural Database | The single worldwide repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, essential for obtaining target structures for docking. |

| ChEMBL / BindingDB [29] | Bioactivity Database | Public databases used to retrieve experimental bioactivity data (e.g., IC50) for compounds against specific oncology targets. |

| Tripos Force Field [5] | Molecular Mechanics Force Field | Used for energy minimization and geometry optimization of molecular structures. |

| Gasteiger-Hückel Charges [5] | Partial Charge Calculation | A method for assigning partial atomic charges to molecules, which are critical for calculating electrostatic fields and docking simulations. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) [29] [6] | Statistical Method | The core regression technique used to build the relationship between 3D molecular field descriptors and biological activity. |

A meticulous approach to data collection and preparation is the bedrock of a successful and predictive 3D-QSAR model for tumor inhibitors. This involves the careful selection and curation of compounds from reliable databases, the rigorous transformation and standardization of biological activity data, and the precise generation and optimization of 3D molecular structures, often guided by molecular docking. Adherence to these detailed protocols for compound selection, activity data handling, and structural preparation, as outlined in this guide, will equip researchers with a robust foundation for embarking on field-based 3D-QSAR studies, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel and potent anti-cancer therapeutics.

Building Your 3D-QSAR Model: A Step-by-Step Workflow for Tumor Inhibitors

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, providing a predictive framework that correlates the chemical structure of compounds with their biological activity. When extended to three dimensions, 3D-QSAR offers superior capability in rational drug design by incorporating spatial and electronic properties that dictate molecular recognition and binding. In the context of tumor inhibitor research, field-based 3D-QSAR techniques implemented in platforms like Forge and SYBYL enable researchers to quantitatively understand how structural features influence anticancer activity, guiding the optimization of lead compounds with improved potency and selectivity.

The fundamental principle underlying 3D-QSAR is that biological activity can be correlated with interaction fields surrounding molecules, typically steric (shape-related) and electrostatic (charge-related) fields. Unlike traditional 2D-QSAR that uses molecular descriptors invariant to conformation, 3D-QSAR derives descriptors directly from the spatial structure of molecules, providing finer resolution of molecular interactions but introducing challenges related to molecular alignment and conformational sampling. For oncology targets, this approach has been successfully applied to various kinase inhibitors, including those targeting RET, BRAF, Plk1, and other key players in cancer signaling pathways.

Theoretical Foundations and Biological Context

Key Signaling Pathways in Cancer

Cancer pathogenesis frequently involves dysregulation of essential signaling pathways that control cell growth, proliferation, and survival. Understanding these pathways provides biological context for 3D-QSAR studies on tumor inhibitors. The following diagram illustrates a prominent pathway frequently targeted in cancer drug discovery:

This pathway is particularly significant in melanoma, where the BRAFV600E mutation occurs in 70-90% of cases, making it a prime target for inhibitor development. BRAF inhibitors like dabrafenib and vemurafenib exemplify successful targeting of this pathway, with their discovery and optimization benefiting from computational approaches including 3D-QSAR.

3D-QSAR methods like Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) operate on the principle that biological activity can be correlated with interaction fields surrounding molecules. The key distinction between traditional QSAR and 3D-QSAR lies in their descriptor systems:

- Classical QSAR: Uses summary descriptors (e.g., logP, molar refractivity) that are invariant to molecular conformation and orientation.

- 3D-QSAR: Derives descriptors from spatial structure and interaction fields calculated at grid points surrounding aligned molecules, making them conformation-dependent.

The table below compares the main 3D-QSAR approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Primary 3D-QSAR Methodologies

| Method | Field Types | Alignment Sensitivity | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | Steric, Electrostatic | High | Established method, easily interpretable contour maps | Congeneric series with reliable alignment |

| CoMSIA | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-bond Donor/Acceptor | Moderate | Smoother fields, additional field types, more tolerant to alignment variations | Structurally diverse datasets |

| Field-Based 3D-QSAR in Forge | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, etc. | Configurable | Advanced statistics, robust validation, intuitive visualization | Lead optimization throughout drug discovery pipeline |

Experimental Setup and Workflow Design

Data Collection and Curation

The foundation of any robust QSAR model is a high-quality, curated dataset of compounds with reliable biological activity data. For tumor inhibitor research, this typically involves collecting IC₅₀ or Kᵢ values from published literature or experimental work.

Data Collection Protocols:

- Source Identification: Extract compound structures and activity data from public databases (ChEMBL, BindingDB) or proprietary corporate databases. For RET kinase inhibitors, one study compiled 952 inhibitors with 49 different 5,6-fused bicyclic heteroaromatic rings from five data sources [29].

- Activity Standardization: Convert all activity measurements to a consistent format (typically pIC₅₀ = -logIC₅₀) and unit (nM). Exclude compounds with ambiguous activity annotations (e.g., containing "<" or ">") [29].

- Structural Curation: Remove duplicates, standardize tautomeric states, and address salt forms. Utilize automated workflows in KNIME or other platforms for efficient data preprocessing [32].

- Chemical Space Analysis: Apply statistical molecular design (SMD) and principal component analysis (PCA) to evaluate structural diversity and ensure adequate coverage of chemical space [33].

Key Considerations for Tumor Inhibitors:

- Focus on compounds tested against specific oncology targets (e.g., BRAFV600E, RET, Plk1)

- Ensure consistent assay conditions (e.g., non-cell-based vs. cell-based)

- Document mutation status of molecular targets when relevant

Molecular Modeling and Conformation Generation

Accurate 3D molecular structures are prerequisite for field-based QSAR analyses. Multiple approaches exist for generating biologically relevant conformations:

Methodology:

- 2D to 3D Conversion: Transform 2D structures to 3D coordinates using tools like RDKit, LigPrep (Schrödinger), or CORINA.

- Geometry Optimization: Minimize structures using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., OPLS3e, MMFF94) or quantum mechanical methods for higher accuracy [29] [1].

- Conformational Sampling: Generate multiple low-energy conformations for each compound using systematic search, stochastic methods, or rule-based approaches. For pyrazole-based TRAP1 inhibitors, conformational ensembles were generated to account for flexibility [34].

Software-Specific Implementation in Forge:

- Utilize the built-in conformation generator with options for energy window and maximum conformers

- Consider the "global minimum" or "diverse" conformation generation strategies based on dataset size

- For large datasets, balance computational cost with conformational coverage (typically 10-50 conformers per compound)

Molecular Alignment Strategies

Molecular alignment constitutes the most critical step in 3D-QSAR, as field descriptors are sensitive to relative molecular orientation. The alignment should reflect putative bioactive conformations:

Common Alignment Protocols:

Table 2: Molecular Alignment Methods for 3D-QSAR

| Method | Procedure | Applicability | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore-Based | Align compounds based on common chemical features (H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions) | Diverse chemotypes with shared pharmacophore | Requires reliable pharmacophore hypothesis |

| Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) | Identify largest common substructure and use for alignment | Structurally related series with variable substituents | May fail for highly diverse compounds |

| Docking-Based | Use molecular docking poses against target protein structure | When crystal structure available and binding mode consistent | Computationally intensive, dependent on docking accuracy |

| Scaffold-Based | Align using core scaffold (e.g., Bemis-Murcko scaffolds) | Series with well-defined common core | Neglects conformational flexibility of side chains |

Case Example - RET Kinase Inhibitors: For 5,6-fused bicyclic heteroaromatic derivatives targeting RET kinase, researchers performed receptor-guided alignment using molecular docking simulations. The crystal structure of RET complex (PDB ID: 7DUA) was prepared, and compounds were docked with constraints to form hydrogen bonds with hinge residues ALA807 or GLU805 [29]. This approach ensured consistent orientation in the biologically relevant binding mode.

Descriptor Calculation and Field Generation

With aligned molecules, the next step involves calculating interaction fields that serve as molecular descriptors:

Standard Protocol:

- Grid Definition: Create a 3D grid that encompasses all aligned molecules with typical spacing of 1.0-2.0 Å.

- Probe Selection: Choose appropriate probe atoms (typically sp³ carbon with +1 charge for CoMFA).

- Field Calculation:

- Steric Fields: Lennard-Jones potential measured at each grid point

- Electrostatic Fields: Coulomb potential calculated at each grid point

- Hydrophobic Fields: In CoMSIA, additional hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding fields

Forge-Specific Implementation:

- Select field types based on target biology (e.g., emphasize hydrophobic fields for targets with extensive hydrophobic pockets)

- Adjust grid padding to ensure complete molecular coverage (typically 4-6 Å beyond molecular extents)

- Consider smoothing functions (Gaussian in CoMSIA) to reduce abrupt field changes

Model Building and Validation Framework

Statistical Modeling using Partial Least Squares (PLS)