From Sequence to Diagnosis: A Practical Guide to Machine Learning for DNA-Based Cancer Detection

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the practical implementation of machine learning (ML) for cancer detection using DNA sequence data.

From Sequence to Diagnosis: A Practical Guide to Machine Learning for DNA-Based Cancer Detection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the practical implementation of machine learning (ML) for cancer detection using DNA sequence data. It explores the foundational principles of DNA-based biomarkers, including mutations, methylation patterns, and fragmentation profiles. The piece details methodological workflows for data processing, feature extraction, and the application of both traditional and advanced deep learning models. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for handling real-world data challenges like class imbalance and low signal-to-noise ratios. Finally, the article offers a framework for the rigorous validation, benchmarking, and clinical interpretation of models, synthesizing key insights to guide the development of robust, translatable ML tools for oncology.

The Genetic Blueprint of Cancer: Core Concepts and Data Sources for ML

The advancement of precision oncology hinges on the ability to decipher the complex molecular signatures of cancer. DNA biomarkers, including somatic mutations, DNA methylation changes, and copy number variations (CNVs), serve as critical indicators for cancer detection, classification, and prognosis. The integration of these biomarkers with machine learning (ML) algorithms has revolutionized oncological research, enabling the analysis of high-dimensional data from technologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS) to uncover patterns that traditional methods might overlook [1]. These computational approaches are particularly vital for tasks such as identifying the tissue-of-origin for cancers of unknown primary, predicting patient outcomes, and tailoring personalized therapeutic strategies [2]. This document outlines the practical application of these key DNA biomarkers within ML frameworks, providing detailed protocols and resources for researchers and drug development professionals.

Biomarker Fundamentals and Data Characteristics

The effective use of DNA biomarkers in ML requires a deep understanding of their biological nature and the specific challenges associated with their data representations.

Somatic Mutations

Somatic mutations are acquired genetic alterations present in tumor cells but not in the patient's germline. They represent a cornerstone of cancer genomics. In ML applications, somatic mutation data is often represented as a binary matrix, where rows correspond to patient samples and columns to specific genes or genomic positions, with values indicating the presence (1) or absence (0) of a mutation [3]. A key challenge is the inherent sparsity of this data; even in large cohorts, most genes are mutated in only a small fraction of samples [2]. Common ML features include driver mutations in genes like KRAS (lung and colorectal cancer), BRAF (melanoma), PIK3CA (breast cancer), and EGFR (non-small cell lung cancer) [4]. These mutations can inform treatment selection and serve as targets for therapeutic interventions.

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to a cytosine base, typically in a CpG dinucleotide context. In cancer, aberrant methylation manifests as global hypomethylation, which can genomic instability, and localized hypermethylation at CpG islands in promoter regions, leading to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes [5]. Methylation data is generated using array-based (e.g., Illumina Infinium 450K or 850K) or sequencing-based (e.g., whole-genome bisulfite sequencing) technologies. The data is quantitative, often reported as β-values ranging from 0 (completely unmethylated) to 1 (fully methylated) [6]. This creates a continuous, high-dimensional dataset ideal for many ML models. Its tissue-specific patterns make it exceptionally valuable for diagnostic and classification tasks [7].

Copy Number Variations (CNVs)

CNVs are somatic alterations that result in gains or losses of genomic DNA segments, leading to deviations from the normal diploid state. These variations can amplify oncogenes or delete tumor suppressor genes. In ML datasets, CNV data is typically represented as a continuous or discrete numerical matrix, where values indicate the copy number state (e.g., -2 for homozygous deletion, -1 for heterozygous deletion, 0 for neutral, 1 for gain, 2 for amplification) for each genomic segment across patient samples [1]. While not the primary focus of all cited studies, CNV data provides crucial complementary information for tumor subtyping and understanding cancer pathogenesis.

Table 1: Characteristics of Key DNA Biomarkers for Machine Learning

| Biomarker | Data Type | Typical Data Format | Key Characteristics in Cancer | Common ML Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic Mutations | Discrete | Sparse binary matrix | Driver vs. passenger mutations; varies widely between cancer types. | Tumor subtyping, prediction of therapeutic targets, prognosis. |

| DNA Methylation | Continuous | β-values (0 to 1) or M-values | Tissue-specific; global hypomethylation with promoter-specific hypermethylation. | Early detection, tissue-of-origin identification, disease classification. |

| Copy Number Variations | Discrete/Continuous | Integer or segmented log-R ratios | Amplifications of oncogenes; deletions of tumor suppressor genes. | Molecular classification, understanding tumorigenesis pathways. |

Machine Learning Data Processing Protocols

Proper data preprocessing is a critical step for building robust and accurate ML models with genomic data.

Data Sourcing and Multi-Omics Integration

Large, well-curated datasets are the foundation of effective ML. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) is a primary source, containing multi-omics data from over 20,000 primary cancer and matched normal samples across 33 cancer types [1] [3]. The Genomic Data Commons (GDC) and cBioPortal provide streamlined access to this data. For methylation-specific data, repositories like the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) are invaluable [1]. Integration of multiple data types (e.g., RNA-seq, methylation, somatic mutation) has been shown to improve classification accuracy. For instance, a stacking ensemble model that integrated these three data types achieved 98% accuracy in classifying five common cancers, outperforming models using any single data type alone [3].

Preprocessing and Feature Selection

High-dimensional genomic data necessitates rigorous preprocessing and feature selection to avoid overfitting.

- Normalization: Techniques like Transcripts Per Million (TPM) for RNA-seq data correct for technical variations and sequencing depth, enhancing cross-sample comparability [8] [3].

- Handling Missing Data: Methods such as k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) imputation can be used to estimate and fill in missing values, ensuring a complete dataset for analysis [8].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Given the large number of features (e.g., >20,000 genes), feature selection is essential. Methods include:

- Filter Methods: Using statistical tests (e.g., Pearson correlation) to select features based on their association with the sample labels [2] [9].

- Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR): An advanced filter method that selects features that are highly relevant to the target class while being minimally redundant with each other [8] [9].

- Autoencoders: A deep learning technique for non-linear dimensionality reduction that can compress data while preserving its essential biological structure [3].

- Addressing Class Imbalance: In cancer datasets, some cancer types may be over-represented. Techniques like Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) or downsampling can balance class distribution and prevent model bias [3].

Experimental and Analytical Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for generating and analyzing DNA biomarker data.

Protocol for Identifying Cancer-Specific Methylation Markers

Objective: To discover and validate DNA methylation markers specific to a cancer type (e.g., Breast Cancer) using array-based technology [6].

Materials:

- Tumor and tumor-adjacent tissue samples.

- Plasma samples from cancer patients, individuals with benign tumors, and healthy donors.

- Infinium Human Methylation 850K BeadChip kit (Illumina).

- Reagents for bisulfite conversion (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit from Zymo Research).

- Equipment for digital droplet PCR (ddPCR), such as the Bio-Rad QX200 system.

Methodology:

- Discovery Phase:

- Extract DNA from tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues.

- Perform genome-wide methylation profiling using the 850K array.

- Identify differentially methylated CpG sites (DMCs) with an absolute methylation difference (Δβ) > 0.10 and an adjusted p-value < 0.05 using a package like "ChAMP" in R.

- Cross-reference DMCs with public datasets (e.g., TCGA, GEO) to filter for sites that are consistently differential and specific to the cancer of interest, while excluding sites methylated in white blood cells or other cancers.

Assay Development (for Plasma cfDNA):

- Design primers and minor groove binder (MGB) TaqMan probes for the top candidate methylation markers.

- Develop a multiplex droplet digital PCR (mddPCR) assay. Optimize the reaction mixture using ddPCR Supermix for Probes and bisulfite-converted DNA.

- Generate droplets, perform PCR, and read the droplets on a QX200 Droplet Reader. Analyze data with QuantaSoft software to quantify the copies of methylated alleles per mL of plasma.

Validation:

- Apply the mddPCR assay to a independent cohort of plasma cfDNA samples from confirmed patients, benign tumor individuals, and healthy controls.

- Evaluate diagnostic performance by calculating the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve.

- Assess prognostic value by correlating methylation levels with overall survival data using Cox regression models.

Protocol for Multi-Omics Cancer Classification with ML

Objective: To build a high-accuracy classifier for cancer types by integrating somatic mutation, DNA methylation, and gene expression data [3].

Materials:

- RNA-seq, somatic mutation, and DNA methylation data from TCGA and LinkedOmics.

- Computational resources (e.g., high-performance computing cluster).

- Python environment with libraries: Scikit-learn, XGBoost, TensorFlow/Keras.

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing:

- RNA-seq: Normalize raw count data using a method like DESeq2's median-of-ratios or TPM [8] [3].

- Somatic Mutation: Create a binary matrix of mutated genes.

- Methylation: Use β-values from array data.

- Clean data by removing samples with >7% missing values and reduce dimensionality using feature selection (e.g., mRMR) or an autoencoder.

Model Training with Stacking Ensemble:

- Base Models: Train a diverse set of five base classifiers on the multi-omics data: Support Vector Machine (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Random Forest (RF).

- Meta-Model: Use the predictions from these base models as input features to train a final meta-classifier (e.g., a logistic regression model or another neural network) to make the ultimate prediction.

Validation:

- Evaluate model performance using a held-out test set or cross-validation.

- Report key metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and AUC.

- Use explainability tools like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to interpret the model's predictions and identify the most important biomarkers [8].

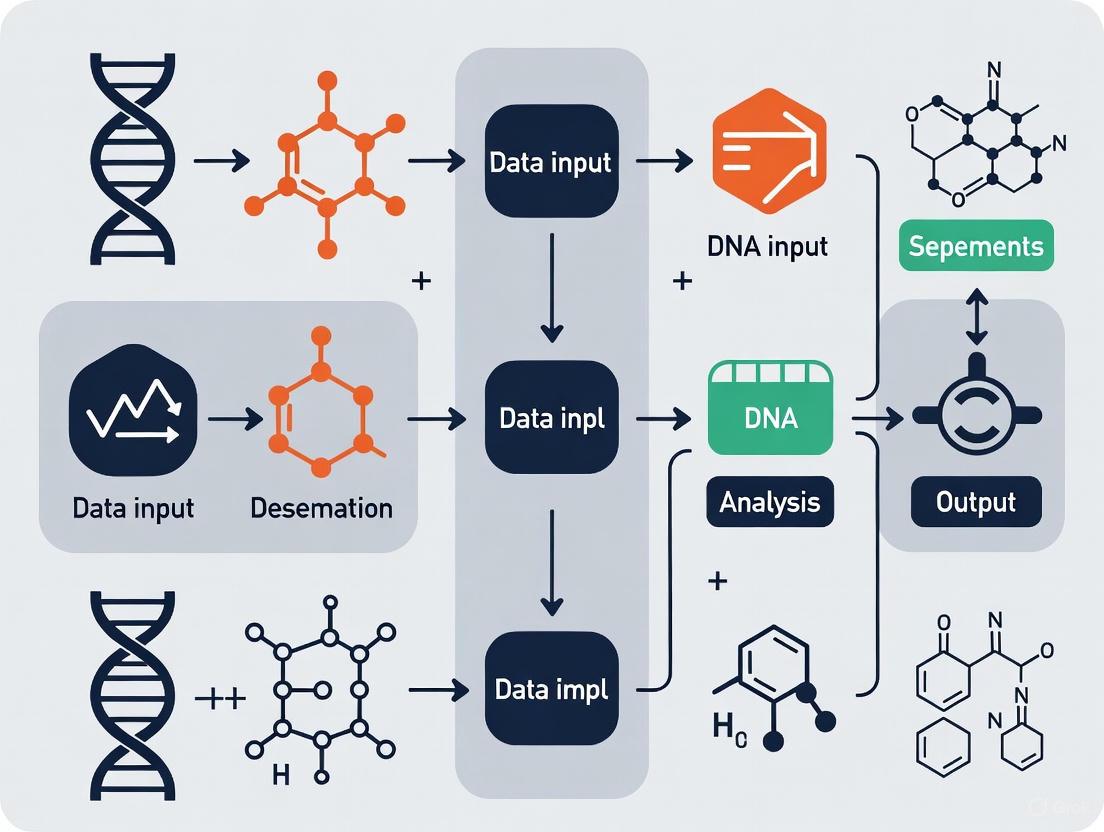

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the multi-omics data integration and analysis process for cancer classification.

Multi-Omics Cancer Classification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for DNA Biomarker and ML-Based Cancer Research

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Primary source for multi-omics data (genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics) from thousands of tumor samples [1] [3]. |

| Genomic Data Commons (GDC) | Data repository and portal providing unified access to TCGA and other cancer genomics datasets [1]. | |

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | Public repository for high-throughput functional genomics data, including methylation array datasets [1] [6]. | |

| Wet-Lab Reagents & Kits | Infinium MethylationEpic (850K) Kit | Array-based platform for genome-wide methylation profiling at over 850,000 CpG sites [6]. |

| EZ DNA Methylation Kit | Used for bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils, a critical step for most methylation analysis methods [7]. | |

| ddPCR Supermix for Probes | Reagent for highly sensitive and absolute quantification of low-abundance nucleic acids in droplet digital PCR assays [6] [4]. | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | "ChAMP" (R/Bioconductor) | Comprehensive pipeline for the analysis of Illumina methylation array data, including DMC identification [6]. |

| "DESeq2" (R/Bioconductor) | Standard tool for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq count data, also used for normalization [8]. | |

| ANNOVAR | Tool for functional annotation of genetic variants from DNA sequencing data [1]. | |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Scikit-learn (Python) | Provides a wide array of classical ML algorithms (SVM, RF, KNN) and utilities for preprocessing and evaluation [3]. |

| XGBoost (Python/R) | Optimized gradient boosting library known for its performance and success in bioinformatics competitions [8] [2]. | |

| TensorFlow/Keras (Python) | Open-source libraries for building and training deep learning models like ANNs and CNNs [3]. | |

| Tutin | Tutin|Glycine Receptor Antagonist|Neurotoxin Research | High-purity Tutin, a potent neurotoxin and glycine receptor antagonist. Essential for neuroscience research into convulsant mechanisms. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Tabac | Tabac|2,4,6-triiodo-3-acetamidobenzoic acid ester | Tabac (C18H21I3N2O5) is a high-purity chemical for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostics or therapeutic use. |

The integration of somatic mutations, DNA methylation, and copy number variations with sophisticated machine learning models represents a powerful paradigm in modern precision oncology. As detailed in these application notes, the successful implementation of this approach relies on rigorous data preprocessing, robust experimental protocols for biomarker discovery, and the strategic use of ensemble and other ML methods to integrate multi-omics data. The provided protocols and toolkit offer a practical roadmap for researchers to contribute to this rapidly evolving field, ultimately driving forward the development of more accurate diagnostic tools and personalized cancer therapies.

Foundational Concepts: cfDNA and ctDNA

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) refers to degraded fragments of DNA that are released into bodily fluids, such as blood plasma, through cellular processes like apoptosis and necrosis [10] [11]. In healthy individuals, the majority of cfDNA originates from normal hematopoietic cells [12]. Its fragment size typically shows a characteristic peak at approximately 166 base pairs, which corresponds to DNA protected by nucleosomes [11].

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) is a specific subset of cfDNA that is derived exclusively from tumor cells [13]. ctDNA carries tumor-specific genetic alterations, such as somatic mutations, and can exhibit a more variable fragment size profile, often including shorter fragments [11]. In cancer patients, ctDNA typically constitutes a very small fraction (0.1% to 1%) of the total cfDNA pool, making its detection technologically challenging [10] [13].

The table below summarizes the key differences between these two molecules.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of cfDNA and ctDNA

| Feature | cfDNA | ctDNA |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Apoptotic/Necrotic normal cells (primarily hematopoietic lineage) | Tumor cells (via necrosis, apoptosis, or active secretion) |

| Fragment Size | Predominantly ~166 bp (mononucleosomal) | Bimodal distribution, often shorter (<150 bp) and longer fragments |

| Concentration | 1-100 ng/mL plasma (in healthy individuals) | Often < 1% of total cfDNA |

| Genetic Alterations | Wild-type | Tumor-specific (e.g., mutations in EGFR, TP53, KRAS) |

| Primary Clinical Utility | Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT), transplant rejection monitoring | Cancer detection, treatment monitoring, therapy selection |

Detection Technologies and Analytical Approaches

The low abundance of ctDNA necessitates highly sensitive detection methods. Common technologies include digital PCR (dPCR) and next-generation sequencing (NGS). NGS, in particular, enables a wide range of analyses, from targeted panels to whole-genome sequencing [13] [11].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized protocol for cfDNA/ctDNA analysis, from sample collection to data interpretation.

Beyond simple mutation detection, several advanced analytical paradigms leverage different features of cfDNA:

- Fragmentomics: This approach analyzes the fragmentation patterns of cfDNA. Tumor-derived DNA often exhibits altered fragmentation due to differences in nucleosome positioning in cancer cells. Research has shown that nucleosome-depleted regions (NDRs) at gene promoters and first exon-intron junctions can be used to infer ctDNA burden and even the tissue of origin [12].

- Methylation Analysis: DNA methylation patterns are highly tissue-specific. Profiling the methylome of cfDNA allows for the detection of cancer signals and can help identify the tumor's origin [11].

- Long-Read Sequencing: Emerging technologies like Oxford Nanopore Sequencing (ONT) enable the simultaneous detection of multiomics features—including genetics, fragmentomics, and direct methylation profiling—in a single assay, offering a more comprehensive view from limited sample material [14].

Experimental Protocol: A Targeted NGS Approach for ctDNA Detection

This protocol outlines the key steps for detecting and analyzing ctDNA from patient blood samples using a targeted next-generation sequencing approach.

Pre-Analytical Phase: Sample Collection and Processing

- Blood Collection: Draw a minimum of 10 mL of whole blood into cell-stabilizing tubes (e.g., Streck tubes) to preserve cfDNA integrity and prevent gDNA contamination from white blood cell lysis. Streck tubes can be stored at room temperature for up to 7 days [11].

- Plasma Separation: Process samples within the recommended timeframe. Centrifuge blood at 1,600 × g for 10-20 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from cellular components. Carefully transfer the supernatant (plasma) to a new tube without disturbing the buffy coat. Perform a second, high-speed centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove any remaining cellular debris [13] [11].

- cfDNA Extraction: Extract cfDNA from the clarified plasma using a bead-based method (e.g., MagMAX kits) optimized for the recovery of short DNA fragments. Bead-based methods are preferred over silica-column techniques for their superior recovery of ctDNA's characteristic short fragments [11]. Elute the purified cfDNA in a low-EDTA TE buffer or nuclease-free water.

- Quality Control (QC): Quantify the extracted cfDNA using a fluorescence-based assay (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay). Assess the fragment size distribution using a Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA kit or similar. A successful extraction from a healthy individual should show a dominant peak at ~166 bp [11].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Library Construction: Use 10-50 ng of cfDNA as input. Prepare sequencing libraries using a hybrid-capture-based targeted NGS panel. The steps include:

- End-Repair and A-Tailing: Convert DNA fragments to blunt-ended, 5'-phosphorylated molecules and add a single 'A' nucleotide to the 3' ends.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific sequencing adapters to the fragments. For multiplexing, use unique dual-indexed adapters for each sample.

- Target Enrichment: Hybridize the library to biotinylated probes designed to capture a panel of cancer-related genes. Wash away non-specific fragments and amplify the captured library with a limited number of PCR cycles [15].

- Sequencing: Pool the enriched, indexed libraries and sequence on an Illumina platform (e.g., NextSeq 550Dx) to a high depth of coverage (>5,000x is recommended for reliable detection of low-frequency variants) [15].

Bioinformatics Analysis

- Primary Analysis: Demultiplex sequenced reads and assess raw data quality using tools like FastQC.

- Alignment: Map the sequencing reads to a reference genome (e.g., hg19/GRCh37) using a splice-aware aligner like BWA-MEM.

- Variant Calling: Identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) using a variant caller such as Mutect2, which is designed for detecting low-frequency somatic variants. A common variant allele frequency (VAF) threshold of ≥2% is often applied [15].

- Annotation and Reporting: Annotate called variants using tools like SnpEff and filter them against population databases. Classify variants according to clinical significance guidelines (e.g., AMP/ASCO/CAP tiers), focusing on Tier I (strong clinical significance) and Tier II (potential clinical significance) alterations for reporting [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for cfDNA/ctDNA Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example Products/Types |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilizes nucleated blood cells to prevent gDNA release and preserve cfDNA profile for up to 7 days at room temperature. | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT, PAXgene Blood cDNA Tube |

| Bead-Based Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate short-fragment DNA with high efficiency; critical for ctDNA recovery. | MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit, Dynabeads |

| Targeted Hybrid-Capture Sequencing Panels | Enrich for genomic regions of interest (e.g., cancer genes) to enable deep sequencing and low-frequency variant detection. | SNUBH Pan-Cancer Panel, Illumina TruSight Oncology, Guardant360 |

| Ultra-Sensitive DNA Quantitation Assays | Accurately quantify low concentrations and small volumes of cfDNA. | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit |

| Molecular Barcoded Adapters | Tag individual DNA molecules pre-amplification to correct for PCR and sequencing errors, improving sensitivity and specificity. | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) in kits from vendors like Illumina and IDT |

| Pfetm | Pfetm, CAS:91112-39-9, MF:C16H26Cl2N4O2S, MW:409.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dhesn | DHESN (Dihydroergosine) | Research-grade DHESN (Dihydroergosine), a serotoninergic ergot alkaloid. For research use only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Integration with Machine Learning for Cancer Detection

The complex, high-dimensional data generated from cfDNA/ctDNA sequencing is an ideal substrate for machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI). ML models can integrate diverse features—including genetic mutations, fragmentomics, and methylation patterns—to improve the sensitivity and specificity of cancer detection.

The diagram below illustrates a typical predictive modeling pipeline for DNA sequence analysis in cancer detection.

Key ML Applications in cfDNA/ctDNA Analysis:

- Overcoming Biological Noise: A primary challenge in early cancer detection is the low concentration of ctDNA. Machine learning algorithms are capable of modeling complex data relationships to distinguish subtle oncogenic patterns from the background noise of normal cfDNA [10]. For instance, models can be trained on fragmentation patterns (fragmentomics) to predict the tissue of origin of cfDNA fragments, effectively acting as a "nucleosome positioning" scanner [10] [12].

- Multi-Feature Integration: ML models can simultaneously analyze multiple data types. A model might take as input mutation calls, copy number variations, and fragmentation profiles from the same NGS run to generate a more robust cancer detection score than any single feature could provide alone [14].

- Sensitivity for Early Detection: Groundbreaking research has demonstrated the potential of this approach. One study used a multi-cancer early detection test on prospectively collected plasma samples and found that ctDNA was detectable in some individuals more than three years prior to their clinical cancer diagnosis [16]. Achieving this level of sensitivity requires analytical methods capable of identifying extremely faint tumor signals, a task for which ML is uniquely suited.

Clinical Applications and Practical Implementation

The analysis of cfDNA and ctDNA has a rapidly expanding set of clinical applications across the cancer care continuum.

Table 3: Key Clinical Applications of cfDNA/ctDNA in Oncology

| Application | Description | Real-World Impact / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Early Cancer Detection & Screening | Identifying cancer signals in asymptomatic individuals via MCED (Multi-Cancer Early Detection) tests. | ctDNA detectable >3 years prior to clinical diagnosis in some cases [16]. GRAIL's Galleri test screens for 50+ cancers [11]. |

| Therapy Selection | Identifying targetable mutations to guide use of targeted therapies or immunotherapies. | Detection of EGFR, KRAS, or BRAF mutations to select appropriate tyrosine kinase inhibitors [15] [11]. |

| Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) & Recurrence Monitoring | Detecting molecular residual disease after curative-intent surgery to predict relapse. | ctDNA positivity post-surgery predicts recurrence months before radiological evidence (e.g., Signatera assay). Guides adjuvant therapy decisions [17] [11]. |

| Therapeutic Response Monitoring | Dynamically tracking ctDNA burden to assess treatment efficacy in real-time. | Declining ctDNA levels correlate with tumor regression; rising levels indicate progression or resistance [17]. |

Considerations for Practical Implementation:

- Test Validation and Concordance: While ctDNA testing is becoming standard in advanced disease, its concordance with tissue-based testing is not perfect. Studies show a concordance rate of approximately 70-80% for detecting key mutations, with sensitivity influenced by disease stage and tumor shedding [17].

- Economic and Logistical Factors: The implementation of NGS and ctDNA testing in clinical practice requires significant investment in bioinformatics infrastructure, specialized personnel, and rigorous quality control to ensure reasonable turnaround times [15].

- Interpretation in Context: ctDNA results must be interpreted with caution. False negatives can occur in patients with low tumor shedding, and false positives can arise from clonal hematopoiesis. A multidisciplinary approach, integrating ctDNA results with clinical, radiological, and pathological findings, is essential for optimal patient management [17].

The shift from broad, genome-wide methylation analysis to focused, targeted panels represents a significant evolution in the application of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for cancer research. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) provides a comprehensive, single-base resolution map of DNA methylation across the entire genome, serving as a powerful discovery tool for identifying novel epigenetic biomarkers [18] [19]. In contrast, targeted sequencing panels enable researchers to concentrate resources on specific genomic regions with known or suspected associations with cancer, facilitating deeper sequencing at lower costs [20]. This strategic progression from unbiased discovery to focused validation is particularly crucial for developing machine learning models in cancer detection, as it dictates both the quality and quantity of training data required for building accurate predictive algorithms. The integration of these complementary approaches provides the foundational data necessary for advancing precision oncology through artificial intelligence.

Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS)

Principle and Mechanism: WGBS combines sodium bisulfite conversion with high-throughput DNA sequencing to detect methylated cytosines at single-nucleotide resolution across the entire genome [18] [19]. The fundamental principle relies on the differential chemical reactivity of methylated versus unmethylated cytosines when treated with sodium bisulfite. Unmethylated cytosines undergo deamination to form uracils, which are then converted to thymines during PCR amplification and subsequent sequencing. In contrast, methylated cytosines (5-methylcytosine, 5mC) are protected from this conversion and remain as cytosines [18]. This chemical modification creates distinct sequencing signatures that allow for precise mapping of methylation status when aligned to an untreated reference genome.

Key Methodological Steps:

- DNA Extraction and Quality Control: High-quality genomic DNA is extracted, with input requirements varying by specific protocol (ranging from >100 ng for standard protocols to as low as ~20 ng for tagmentation-based methods) [18].

- Bisulfite Conversion: DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite, facilitating the deamination of unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged.

- Library Preparation: Converted DNA undergoes library preparation, with emerging methods like Tagmentation-based WGBS (T-WGBS) combining fragmentation and adapter ligation in a single step to minimize DNA loss [18].

- Sequencing and Data Analysis: Libraries are sequenced using NGS platforms, followed by alignment to a reference genome and methylation calling using specialized bioinformatics tools.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and principle of bisulfite sequencing:

Variants of Bisulfite Sequencing

Several specialized bisulfite sequencing methods have been developed to address specific research needs and limitations of conventional WGBS:

Table 1: Comparison of Bisulfite Sequencing Methods

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Genome-wide mapping at single-base resolution [18] | Covers CpG and non-CpG methylation; comprehensive [18] | High cost; substantial DNA degradation; complex data analysis [18] [19] | Discovery of novel methylation biomarkers; pan-cancer studies [21] |

| Reduced-Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Uses restriction enzymes for sequence-specific fragmentation [18] | Cost-effective; focuses on CpG-rich regions [18] | Covers only ~10-15% of CpGs; biased selection [18] | High-throughput population studies; specific promoter analysis [18] |

| Oxidative Bisulfite Sequencing (oxBS-Seq) | Differentiates 5mC from 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) [18] | Clearly distinguishes between 5mC and 5hmC [18] | Complex protocol; same limitations as BS-Seq for alignment [18] | Fine epigenetic mapping; studying active demethylation pathways |

| Tagmentation-based WGBS (T-WGBS) | Uses Tn5 transposase for fragmentation and adapter ligation [18] | Minimal DNA input (~20 ng); fast protocol [18] | Does not distinguish 5mC from 5hmC; alignment challenges [18] | Limited sample availability; clinical specimens |

| Single-cell Bisulfite Sequencing (scBS-Seq) | Adapted from BS-Seq and PBAT for single cells [18] | Enables methylation analysis at single-cell resolution [18] | Extremely low input DNA; technical noise | Tumor heterogeneity studies; developmental biology |

Targeted Sequencing Panels

Targeted sequencing panels represent a focused approach that sequences specific genes or genomic regions with known or suspected associations with disease. These panels are particularly valuable in clinical applications where resources must be strategically allocated to maximize information yield from limited samples [20].

Design Strategies:

- Predesigned Panels: Contain curated gene content selected from published literature and expert guidance for specific diseases or phenotypes [20].

- Custom Panels: Allow researchers to target specific genomic regions relevant to their research interests, enabling follow-up on discoveries from WGBS or other genome-wide approaches [20].

Methodological Approaches:

- Amplicon Sequencing: Utilizes highly multiplexed PCR to amplify regions of interest prior to sequencing. This approach is ideal for smaller gene sets (<50 genes) and offers a simpler, more affordable workflow with less hands-on time [20].

- Hybrid Capture: Involves solution-based hybridization of genomic DNA to biotinylated probes complementary to targeted regions, followed by magnetic pulldown. This method is better suited for larger gene content (>50 genes) and provides more comprehensive variant detection, though with longer turnaround times [20] [22].

Targeted panels sequence genes of interest to exceptional depth (500-1000× or higher), enabling identification of rare variants that might be missed in broader approaches [20]. The manageable data size simplifies storage and analysis while reducing costs compared to whole-genome methods.

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

WGBS Protocol for Cancer Epigenomics

Sample Preparation:

- Input Requirements: 20-100 ng of high-quality genomic DNA, depending on the specific protocol [18]. For tagmentation-based WGBS, inputs as low as 20 ng are feasible [18].

- Quality Control: Assess DNA integrity using agarose gel electrophoresis or fragment analyzers. Ensure DNA is free of contaminants that may inhibit bisulfite conversion.

Bisulfite Conversion and Library Preparation:

- Bisulfite Treatment: Treat DNA with sodium bisulfite using commercial kits (e.g., Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation kits). Typical conditions: incubation at 95°C for 30-60 seconds followed by 50-60°C for 45-60 minutes [18] [19].

- Library Construction: For standard WGBS, fragment converted DNA by sonication or enzymatic digestion to ~300 bp fragments. Ligate methylated adapters to fragment ends [18]. For T-WGBS, use Tn5 transposase for simultaneous fragmentation and adapter incorporation [18].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify libraries with DNA polymerases optimized for bisulfite-converted templates. Limit PCR cycles (typically 8-12) to minimize bias in amplification of methylated versus unmethylated sequences [19].

- Library Quantification and Validation: Quantify libraries using fluorometric methods and validate size distribution using bioanalyzer or tape station systems.

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Sequencing Parameters: Sequence on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq, HiSeq) with 2×150 bp paired-end reads recommended for adequate alignment efficiency [18].

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Quality Control: Use FastQC to assess read quality.

- Alignment: Map reads to a bisulfite-converted reference genome using specialized aligners (Bismark, BS-Seeker2).

- Methylation Calling: Extract methylation information at each cytosine position, generating coverage files and methylation ratios (number of C reads/total reads).

- Differential Analysis: Identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) between sample groups using tools like methylKit or DMRept.

Targeted Panel Protocol for Liquid Biopsy Applications

Sample Preparation:

- Cell-Free DNA Extraction: Isolate cfDNA from 5-10 mL of plasma using specialized extraction kits (e.g., Illumina Cell-Free DNA Prep with Enrichment). Typical yields range from 1-100 ng cfDNA per mL plasma [20].

- Quality Assessment: Verify cfDNA size distribution (expected peak ~167 bp) using bioanalyzer systems.

Library Preparation and Target Enrichment:

- Library Construction: Use library prep kits designed for low-input cfDNA (e.g., Illumina Cell-Free DNA Prep with Enrichment) with incorporation of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish true variants from PCR errors [20].

- Target Enrichment: For hybrid capture approaches, hybridize libraries with biotinylated probes targeting cancer-associated genes (e.g., 50-200 gene panels). Incubate for 16-24 hours, then capture with streptavidin beads [20]. For amplicon approaches, use multiplex PCR with primers targeting regions of interest.

- Post-Capture Amplification: Amplify captured libraries with limited PCR cycles (8-12) to maintain representation.

Sequencing and Variant Calling:

- Sequencing Parameters: Sequence to high depth (typically >3000× for cfDNA applications) using Illumina platforms to detect variants at low allele frequencies (down to 0.2%) [20].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment: Map reads to reference genome using optimized aligners (BWA-MEM).

- Variant Calling: Use specialized callers (MuTect2, VarScan2) with UMI correction to identify somatic mutations at low allele fractions.

- Annotation: Annotate variants with population frequency, functional impact, and clinical significance using databases (COSMIC, ClinVar).

Integration with Machine Learning for Cancer Detection

Data Requirements for Machine Learning Models

The successful application of machine learning (ML) to cancer detection requires carefully curated training data with specific characteristics. WGBS provides comprehensive methylation data ideally suited for discovery-phase ML, while targeted panels offer focused data for validated biomarker applications.

Table 2: Data Characteristics for Machine Learning Applications

| Data Characteristic | WGBS for ML | Targeted Panels for ML |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | ~28 million CpG sites in humans [19] | Hundreds to thousands of validated CpG sites |

| Sample Requirements | Higher input DNA (typically >20 ng) [18] | Lower input (cfDNA feasible) [20] |

| Data Volume | Very large (hundreds of GB per sample) | Manageable (GB range per sample) |

| Feature Selection | Unbiased, discovery-oriented [5] | Hypothesis-driven, focused on known biomarkers |

| Best ML Applications | Novel biomarker discovery; pan-cancer classification [5] | Clinical diagnostics; minimal residual disease detection [23] |

AI-Driven Methylation Analysis in Multi-Cancer Detection

Artificial intelligence has revolutionized the analysis of DNA methylation patterns for cancer detection and classification. Advanced ML algorithms, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and gradient boosting machines (GBMs), can recognize subtle cancer-specific methylation signatures in complex datasets [5]. These approaches have enabled the development of Multi-Cancer Early Detection (MCED) tests that analyze circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) methylation patterns to detect multiple cancer types from a single blood sample [5].

Notable Applications:

- GRAIL's Galleri Test: Employs targeted methylation sequencing of over 100,000 informative regions and ML algorithms to detect more than 50 cancer types with high specificity [5].

- CancerSEEK: Integrates mutation data with protein biomarkers to improve diagnostic sensitivity across eight cancer types [5].

- Prostate Cancer Detection: Machine learning-prioritized targeted sequencing panels have demonstrated improved detection of tumor-derived variants in cfDNA from patients with localized prostate cancer [23].

The typical workflow for ML-driven cancer detection from methylation data involves multiple stages of data processing and model development, as shown in the following diagram:

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of DNA sequencing technologies for cancer research requires carefully selected reagents and platforms optimized for specific applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Category | Specific Products/Solutions | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation | Illumina DNA Prep with Enrichment [20] | Flexible targeted sequencing for genomic DNA, tissue, blood, saliva, and FFPE samples | Targeted panel sequencing |

| Illumina Cell-Free DNA Prep with Enrichment [20] | Scalable library prep for highly sensitive mutation detection from cfDNA | Liquid biopsy applications | |

| Bisulfite Conversion | Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation kits | Efficient conversion with minimal DNA degradation | WGBS, RRBS |

| Target Enrichment | Illumina Custom Enrichment Panel v2 [20] | Fully customized enrichment solution (20 kb-62 Mb regions) | Custom targeted sequencing |

| AmpliSeq for Illumina Custom Panels [20] | Custom panels optimized for specific content of interest | Focused gene panels | |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, HiSeq, MiSeq [24] | High-throughput sequencing with various output options | WGBS, targeted panels |

| Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine [24] | Semiconductor-based sequencing technology | Targeted sequencing | |

| Design Tools | DesignStudio Software [20] | Online tool for optimizing custom probe designs | Custom panel design |

The strategic selection of DNA sequencing technologies—from comprehensive WGBS to focused targeted panels—provides researchers with a powerful toolkit for advancing cancer detection and precision medicine. WGBS offers an unbiased discovery platform for identifying novel methylation biomarkers across the entire genome, while targeted panels enable cost-effective, deep sequencing of validated markers in clinical samples. The integration of these technologies with advanced machine learning algorithms has already demonstrated significant promise in multi-cancer early detection tests and precision oncology applications. As sequencing costs continue to decline and analytical methods improve, these approaches will increasingly converge, enabling more sensitive, specific, and accessible cancer diagnostics that leverage the full potential of epigenetic information for improving patient outcomes.

Public Data Repositories and Standards for Acquiring Cancer DNA Sequence Data

The effective application of machine learning (ML) to cancer detection hinges on access to high-quality, well-annotated DNA sequence data. For researchers building ML models to identify oncogenic signatures, understanding the landscape of public data repositories and the standards governing data acquisition is a critical first step. These resources provide the foundational data upon which predictive models for cancer detection, diagnosis, and treatment are built. This guide details the primary sources of cancer genomic data, the standard file formats encountered, and practical protocols for accessing and utilizing this data within an ML research workflow.

Major Public Data Repositories

Large-scale public repositories house vast amounts of genomic data from cancer studies, serving as indispensable resources for the research community. The following table summarizes key repositories used in cancer genomics research.

Table 1: Key Public Data Repositories for Cancer Genomics

| Repository Name | URL | Primary Focus | Data Types | Bulk Data Retrieval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCI Genomic Data Commons (GDC) | https://gdc.cancer.gov/ | Unified repository for NCI cancer genome programs like TCGA [25]. | Clinical data, somatic mutations, gene expression, DNA methylation [25]. | Yes [26] |

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ | Public repository for functional genomics data from tens of thousands of studies [25]. | Array- and sequence-based data from published studies [25]. | Yes [25] |

| Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) | https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/ | International repository for raw sequence data, based in China [27]. | Raw sequence data [27]. | Information missing |

| cBioPortal | http://www.cbioportal.org/ | Visualization, analysis, and download of large-scale cancer genomics datasets [25]. | Gene sequencing data from cancer studies, including TCGA [25]. | Yes [25] |

| Broad GDAC Firehose | http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/ | Provides standardized analysis outputs on the entire TCGA dataset [25]. | Analysis results and high-level standardized data tables [25]. | Yes [25] |

The NCI Genomic Data Commons (GDC) is a cornerstone for cancer genomics, providing a unified platform that harmonizes data from multiple projects, including The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [25]. The GDC not only provides access to data but also includes web-based tools for searching, viewing, and downloading datasets. For large-volume data transfers, the GDC offers a high-performance Data Transfer Tool [26]. It's important to note that access to controlled data, which includes detailed patient-level information, requires authorization through the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) [26].

For researchers seeking user-friendly interfaces to explore genetic alterations across cancer types, tools like cBioPortal are invaluable. It allows for the visualization of mutation and copy number alteration patterns for a set of input genes across samples within a given study [25]. Similarly, Oncomine and UALCAN focus on enabling researchers to explore differential gene expression between cancer and normal samples [25].

Data Formats and Standards

Understanding the structure and content of genomic file formats is essential for data preprocessing and feature extraction in ML pipelines. The two primary text-based formats for nucleotide sequences are FASTA and FASTQ.

Table 2: Comparison of FASTA and FASTQ File Formats

| Feature | FASTA Format | FASTQ Format |

|---|---|---|

| Information Content | Nucleotide or protein sequences [28] | Nucleotide sequences and per-base quality scores [28] |

| Standard Use | Reference genomes, assembled contigs, protein sequences [28] | Raw sequence reads from high-throughput sequencers [28] |

| Quality Information | Typically none, though some conventions use lower-case for low-confidence bases [28] | Yes (Phred-scaled quality scores for each base) [28] |

| File Structure | 1. Identifier line starting with >2. Sequence data on subsequent lines [28] |

1. Identifier line starting with @2. Sequence data3. A + line (may repeat identifier)4. Quality scores string [28] |

| Typical File Size | Relatively smaller | Very large (often 10s of GB compressed), due to quality scores and raw data volume [28] |

FASTA Format

A FASTA file contains one or more sequences. Each entry consists of an identifier line beginning with a > symbol, followed by the sequence data. The identifier can include a unique ID and optional descriptive information about the sequence, such as gene function, species, or location in the genome [28]. This format is the standard input for sequence alignment tools like BLAST and HMMER, and for reference genomes used in read mapping [28].

FASTQ Format

FASTQ is the standard format for raw sequencing reads from platforms like Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore. Each read is represented by four lines: the sequence identifier (starting with @), the nucleotide sequence, a separator line (often just a +), and a string of quality score characters [28]. The quality scores are encoded in Phred scale, where each character represents the probability of a base-calling error [29]. These scores are crucial for ML applications as they provide a measure of confidence for each base, allowing preprocessing steps to trim or filter low-quality data, thereby improving downstream model accuracy.

Data Access Tiers and Acquisition Workflow

Genomic data is often organized into different tiers of accessibility. Open-access data is freely available to all users without restrictions. Controlled-access data, which includes personally identifiable information, requires researchers to apply for access through dbGaP by submitting a research protocol for approval [26].

The data within repositories can also be understood through a "level" framework, which describes the degree of processing:

- Level 1: Raw data (e.g., FASTQ files, microarray images) [25].

- Level 2: Essential processed information (e.g., BAM alignment files) [25].

- Level 3: Data ready for analysis (e.g., variant calls, normalized expression tables) [25].

- Level 4: Results from platform-specific analyses (e.g., significantly mutated genes) [25].

- Level 5: Integrated findings, combining multiple data types and external knowledge [25].

ML researchers often start with Level 3 or 4 data for model training, while those developing novel base-calling or variant-calling algorithms may require Level 1 or 2 data.

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for acquiring and preparing cancer DNA sequence data for ML research.

Protocols for Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Protocol: Accessing Controlled Data from the GDC

This protocol outlines the steps to acquire controlled-access genomic data, which is often essential for building robust ML models in cancer research.

Prerequisites:

- eRA Commons Account: Ensure you have a registered account in the NIH eRA Commons system.

- Institutional Signing Official: Identify the appropriate official at your institution who can approve and sign data access requests.

Procedure:

- dbGaP Application: Navigate to the dbGaP website and submit a Data Access Request (DAR) for the specific dataset of interest (e.g., a TCGA dataset via the GDC) [26].

- Research Protocol Submission: As part of the DAR, you will be required to provide a detailed research protocol outlining the planned use of the data, including specific research objectives and the measures you will take to protect data confidentiality.

- Review and Approval: The request is reviewed by the Data Access Committee (DAC) associated with the dataset. This process ensures the proposed use is scientifically valid and ethically sound.

- Download Data: Once approved, use the GDC Data Portal or the high-performance GDC Data Transfer Tool for downloading large volumes of data [26]. The transfer tool is essential for managing the large file sizes typical of genomic data.

Protocol: From Raw FASTQ to ML-Ready Features

This protocol describes a common preprocessing workflow to transform raw sequencing reads (FASTQ) into structured numerical features suitable for machine learning. This is a generalized protocol; specific tools and parameters will vary based on the research goal.

Materials:

Procedure:

- Quality Control (QC): Run FastQC on the raw FASTQ files to assess per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and other potential issues. This step informs the parameters for subsequent trimming.

- Adapter Trimming and Quality Filtering: Use a tool like Trimmomatic to remove sequencing adapters and trim low-quality bases from the ends of reads. This improves the quality of the data used for alignment.

- Alignment to Reference Genome: Map the quality-filtered reads to a reference genome using an aligner like BWA or Bowtie2 [28]. This generates a BAM file, which stores the aligned reads and their positions.

- Post-Alignment Processing and Variant Calling: This includes sorting and indexing BAM files. For mutation-based ML models, use a variant caller like GATK [28] to identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) from the BAM file. The output is a VCF file listing genomic variants.

- Feature Engineering: Convert the biological data into a numerical feature matrix. This could involve:

- Variant-Based Features: Creating a sample x gene matrix where values represent mutation counts or a binary indicator of mutation presence/absence.

- Coverage-Based Features: Calculating read depth or copy number variation (CNA) in genomic bins [10].

- Fragmentation Features: For cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analyses, features can include fragment size distributions, nucleosome positioning patterns, and preferred end sites [10].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for cfDNA-based ML Detection

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA (cfDNA) from Plasma | The target analyte containing the signal of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) for non-invasive liquid biopsy [10]. |

| Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) Kit | A protocol for treating DNA with bisulfite to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils, allowing for the assessment of methylation states, a key cancer signature [10]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencer (e.g., Illumina) | The instrument platform for generating raw sequence reads in FASTQ format from the input DNA [10]. |

| Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) | A software package for variant discovery and genotyping; used in the protocol for variant calling and sequence analysis [10]. |

| Reference Genome FASTA File | The standardized reference sequence (e.g., GRCh38) against which cfDNA reads are aligned to identify genomic origins and variations [28] [10]. |

The path to acquiring and standardizing cancer DNA sequence data is a structured process critical for powering ML-driven detection algorithms. By leveraging the rich data from repositories like the GDC and GEO, and adhering to standardized preprocessing protocols, researchers can generate high-quality, ML-ready datasets. Mastering these foundational steps of data acquisition and preparation is paramount for developing robust, generalizable models that can ultimately contribute to advancements in early cancer detection and precision oncology.

Building the Model: ML Workflows and Algorithm Selection for DNA Sequence Analysis

The shift towards data-driven methodologies in genomics has made the effective conversion of raw DNA sequences into informative features a critical step in machine learning (ML) pipelines for cancer detection. This process, known as feature engineering, directly influences a model's ability to identify pathological patterns. This Application Note details three advanced feature extraction techniques—k-mer analysis, sentence embeddings (SBERT/SimCSE), and DNA methylation profiling—within the practical context of cancer research. Each method bridges the gap between complex biological sequences and quantifiable features, enabling researchers to build more accurate and robust diagnostic and classification models. We provide structured protocols, comparative data, and visualization tools to facilitate implementation by research scientists and drug development professionals.

k-mer Analysis for DNA Sequence Classification

k-mer analysis is a foundational technique in genomic machine learning that involves breaking down long DNA sequences into shorter, overlapping subsequences of length k. This approach treats DNA as a text string, allowing the application of Natural Language Processing (NLP) methods to identify sequence-based motifs and variations associated with different cancer types [30]. The core principle is that the frequency and composition of these k-mers provide a numerical signature that can distinguish between sequences derived from healthy and cancerous tissues, or between different cancer subtypes.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Source: Obtain DNA/Genomic sequences in FASTA format from public repositories like the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [31].

- Handling Class Imbalance: If certain cancer types are underrepresented (e.g., MERS and dengue in viral datasets), employ the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE). This algorithm generates synthetic samples for minority classes by interpolating between existing instances in feature space [31].

Step 2: k-mers Generation

- Generate all possible subsequences of length k from a DNA sequence via a sliding window.

- The choice of k is critical: small k (e.g., 3-6) captures simple motifs, while larger k captures more complex, specific sequences but increases dimensionality.

- Python Function Example:

For a sequence "CCGAGGGCT" with

k=3, output is['CCG', 'CGA', 'GAG', 'AGG', 'GGG', 'GGC', 'GCT'][30].

Step 3: k-mers Concatenation and Vectorization

- Concatenate all k-mers from a sequence into a single "document."

- Convert this document into a numerical format using:

- Bag-of-Words (BoW): Creates a count vector of all possible k-mers.

- TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency): Weights k-mer frequencies by their importance across the entire dataset, often yielding superior results [30].

Step 4: Model Training and Classification

- Feed the vectorized features into standard ML classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) or deep learning models.

Table 1: Performance of Different Models and k-mer Encoding on DNA Sequence Classification

| Model Architecture | Encoding Method | Reported Testing Accuracy | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | K-mer (size not specified) | 93.16% | Classification of COVID, MERS, SARS, dengue, hepatitis, influenza [31] |

| CNN-Bidirectional LSTM | K-mer (size not specified) | 93.13% | Classification of COVID, MERS, SARS, dengue, hepatitis, influenza [31] |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | Hybrid k-mer/probabilistic | 89.51% | Classification of mutated DNA to identify virus origin [31] |

| Ensemble Decision Tree | K-mer based features | 96.24% | Classification of complex DNA sequence datasets [31] |

Workflow Visualization

Sentence Embeddings (SBERT/SimCSE) for Genomic Sequences

Sentence-BERT (SBERT) is a modification of the BERT architecture designed to derive semantically meaningful sentence embeddings that can be compared using cosine-similarity [32]. When applied to genomics, DNA sequences are treated as sentences, and k-mers or other representations are treated as words. SBERT uses siamese and triplet networks to create embeddings where semantically similar sequences (e.g., from the same cancer subtype) are close in vector space. SimCSE is a simple, unsupervised extension that uses dropout as a form of noise to create positive pairs for training, significantly improving embedding quality without labeled data [33]. This approach is powerful for semantic similarity search and clustering of genomic data.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: DNA Sequence Preprocessing and "Sentence" Formation

- Convert DNA sequences into a textual format suitable for embedding models.

- Recommended Approach: Generate k-mers (e.g., k=3-6) for a sequence and join them with spaces to form a "sentence" (e.g.,

CCG CGA GAG AGG GGG). This preserves local context and creates an input structure analogous to natural language.

Step 2: Unsupervised Training with SimCSE

- SimCSE leverages dropout for creating positive pairs, requiring no manually labeled data.

- Python Code Skeleton: [33].

Step 3: Generating and Using Embeddings

- Use the trained model to compute dense vector embeddings for any DNA sequence.

- Inference:

- These embeddings can be used for:

- Clustering: Group unlabeled sequences to discover novel cancer subtypes.

- Semantic Search: Find sequences most similar to a query sequence in a large database in seconds, a task that is computationally prohibitive with raw BERT [32].

Table 2: Impact of Model and Training Parameters on Embedding Quality (AskUbuntu MAP)

| Parameter | Option 1 | Performance (MAP) | Option 2 | Performance (MAP) | Option 3 | Performance (MAP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Model | distilbert-base-uncased | 53.59 | bert-base-uncased | 54.89 | distilroberta-base | 56.16 |

| Batch Size (distilroberta-base) | 128 | 56.16 | 256 | 56.63 | 512 | 56.69 |

| Pooling Mode (distilroberta-base, 512 batch) | CLS Pooling | 56.56 | Mean Pooling | 56.69 | Max Pooling | 52.91 |

Workflow Visualization

Methylation Profiling for Cancer Classification

DNA methylation is an epigenetic modification involving the addition of a methyl group to a cytosine base in a CpG dinucleotide context. Aberrant methylation patterns are stable, organ-specific, and play a key role in cancer development, making them ideal biomarkers for diagnosis and classification [34] [35]. Machine learning models can leverage data from platforms like the Illumina Infinium Human Methylation 450k BeadChip (interrogating 450,000 CpG sites) to distinguish cancerous from normal tissues and identify the tissue of origin for cancers of unknown primary (CUP) with high accuracy [34] [35].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Source: Download methylation β-values (ranging from 0 unmethylated to 1 fully methylated) for cancer and normal tissue samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) via the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) portal [34] [35].

- Preprocessing:

- Remove low-variance features: Filter out CpG sites with minimal variation across samples.

- Batch effect correction: Correct for technical artifacts using methods like ComBat.

- Data split: Divide data into training (70%) and test (30%) sets, stratifying by cancer type [34].

Step 2: Feature Selection for Biomarker Discovery

- Given the high dimensionality (~485,000 features), aggressive feature reduction is essential.

- Two-Step Filter and Embedded Method:

- Decision Tree Approach: An alternative is to use a decision tree to identify a small panel of CpG sites where the median β-value for cancer and normal groups fall on opposite sides of a biologically relevant threshold (e.g., β=0.3) [35].

Step 3: Model Training and Validation

- Train a classifier on the selected CpG sites.

- Model Choices: Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), CatBoost, Random Forest, and Neural Networks have shown high performance [34] [35].

- Validation: Use stratified 5-fold cross-validation and an independent test set. Evaluate using accuracy, F1 score, and AUC.

Table 3: Performance of Methylation-Based Classifiers Across Studies

| Cancer Types | Number of Samples / Types | Feature Selection Method | Final # of CpG Sites | Best Model(s) | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 types (e.g., BRCA, COAD, LUAD) [34] | 890 / 10 | ANOVA/Gain Ratio -> Gradient Boosting | 100 | XGBoost, CatBoost, Random Forest | 87.7% - 93.5% |

| Urological Cancers (Prostate, Bladder, Kidney) [35] | Not Specified / 3 | Decision Tree | 6 - 14 (per cancer type) | Neural Network | High (Visual separation via PCA) |

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Resources for Feature Extraction in Genomic ML

| Category / Item | Function / Description | Example Sources / Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | ||

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Provides comprehensive, publicly available genomic datasets (including methylation and sequence data) for multiple cancer types. | Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Portal [34] [35] |

| National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) | Repository for DNA sequence data in FASTA format, essential for sequence-based classification tasks. | NCBI Nucleotide Database [31] |

| Wet-Bench Profiling | ||

| Illumina Infinium Methylation BeadChip | Platform for genome-wide methylation profiling, generating β-values for ~450,000 or ~850,000 CpG sites. | Illumina 450k/850k Array [34] [35] |

| Software & Computational Tools | ||

| Orange Data Mining Suite | A Python-based, visual tool for data analysis, machine learning, and preprocessing of methylation and other biological data. | Orange v3.32 [34] |

| Sentence Transformers (SBERT) | The primary Python library for using and training state-of-the-art sentence embedding models like SBERT and SimCSE. | sbert.net [32] [33] [36] |

| Scikit-learn, XGBoost, CatBoost | Standard Python libraries for implementing a wide range of machine learning models and evaluation metrics. | [34] [31] |

| Bioinformatics Packages | Custom Python packages for genomic data preprocessing, including k-mer generation and vectorization. | PyDNA (hypothetical example) [30] |

| Azido | Azido, MF:N3, MW:42.021 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AR-42 | AR-42, MF:C18H20N2O3, MW:312.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The transition from raw DNA sequences to meaningful features is a critical enabler for modern machine learning applications in cancer research. K-mer analysis provides a robust and interpretable method for sequence-based classification. Sentence embedding techniques like SBERT and SimCSE offer a powerful, modern approach for understanding semantic similarity and clustering in genomic data without the need for extensive labeled datasets. Finally, methylation profiling leverages well-established epigenetic biology to deliver highly accurate tissue-of-origin and diagnostic classifications, even with a minimal set of CpG sites. The protocols and analyses provided here serve as a practical guide for researchers aiming to implement these techniques, ultimately contributing to more precise cancer detection and diagnosis.

The application of machine learning (ML) to DNA sequence analysis is revolutionizing the field of cancer detection, offering new pathways for early diagnosis and personalized treatment strategies. As the volume and complexity of genomic data grow, selecting and implementing the appropriate model architecture becomes critical for translating data into actionable clinical insights. This practical guide focuses on three powerful architectures demonstrating significant promise in oncology research: blended ensembles, XGBoost, and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). We detail their practical implementation through specific application notes, experimental protocols, and performance benchmarks derived from recent studies, providing researchers with a framework for applying these techniques to DNA-based cancer detection.

Performance Comparison of Model Architectures

The table below summarizes the performance of different model architectures as reported in recent cancer detection and classification studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML Architectures in Cancer Detection

| Model Architecture | Application Context | Data Types | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blended Ensemble (LR + GNB) | Multi-cancer type classification | DNA Sequencing | 100% accuracy for BRCA1, KIRC, COAD; 98% for LUAD, PRAD; ROC AUC 0.99 | [37] |

| Stacked Deep Learning Ensemble | Multi-cancer type classification | RNA-seq, Somatic Mutation, DNA Methylation | 98% accuracy with multiomics data | [3] |

| XGBoost | Cancer-specific chromatin feature analysis | Cell-free DNA, Open Chromatin | Improved cancer detection accuracy | [38] |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Cancer type prediction | Gene Expression (RNA-seq) | 93.9–95.0% accuracy across 33 cancer types and normal tissue | [39] |

| Random Forest, NN, XGBoost Ensemble | General cancer detection and classification | Genomic Data | 99.45% detection accuracy, 93.94% type classification accuracy | [40] |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Blended Ensemble for DNA Sequencing Data

Application Note: A high-performance blended ensemble combining Logistic Regression (LR) and Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB) has been developed for DNA-based cancer prediction [37]. This architecture leverages the strengths of both models—GNB's strong foundational assumptions and LR's ability to model complex decision boundaries. The blend creates a lightweight, interpretable, yet highly effective tool suitable for clinical settings where both accuracy and explainability are valued. The model was validated on a cohort of 390 patients across five cancer types (BRCA1, KIRC, COAD, LUAD, PRAD), achieving near-perfect accuracies [37].

Experimental Protocol:

Data Preparation:

- Input: DNA sequencing data from patient samples.

- Processing: Perform standard genomic data preprocessing, including quality control, alignment, and variant calling. Structure the data into a feature matrix suitable for traditional ML algorithms.

Model Training & Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Implement both Logistic Regression and Gaussian Naive Bayes base models.

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Conduct a comprehensive grid search to optimize key parameters for both models. This includes regularization strength (

C) and solver for LR, as well as variance smoothing for GNB. - Blending: Train a meta-learner (often a linear model) on the predictions (or class probabilities) generated by the base models' cross-validated folds. This prevents overfitting.

Model Validation:

- Validate the final blended model on a held-out test set.

- Performance Metrics: Report accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC. The benchmark for this architecture includes accuracies of 100% for several cancer types and a macro-average ROC AUC of 0.99 [37].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for developing this blended ensemble model:

XGBoost for Open Chromatin Analysis in Cell-free DNA

Application Note: XGBoost has proven highly effective for analyzing nucleosome enrichment patterns in cell-free DNA (cfDNA) at open chromatin regions, providing a non-invasive method for cancer detection [38]. Its key advantage in this context is the combination of high predictive performance with interpretability. By using SHAP or built-in feature importance, researchers can identify which specific genomic loci (e.g., cancer-specific or immune cell-specific open chromatin regions) most significantly contribute to the prediction, yielding biologically actionable insights [38].

Experimental Protocol:

Feature Engineering from cfDNA:

- Input: cfDNA sequencing data from blood plasma of cancer patients and healthy donors.

- Feature Definition: Define features based on read-count enrichment or nucleosome positioning patterns within cell type-specific open chromatin regions (e.g., from ATAC-seq peaks of relevant cancer and immune cells) [38].

- Data Wrangling: Structure these enrichment scores into a feature matrix where rows are samples and columns are genomic regions.

Model Training with Interpretability:

- Training: Train an XGBoost classifier on the feature matrix, using cancer vs. healthy as the target variable.

- Handling Class Imbalance: Apply techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) or adjusting class weights to manage imbalanced datasets [41].

- Interpretation: Use SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis or XGBoost's native feature importance to rank the genomic regions by their contribution to the model's predictions [38]. This identifies key cancer-associated chromatin features.

Validation:

- Use cross-validation and hold-out testing.

- Performance Metrics: Assess model performance using ROC-AUC, accuracy, and precision. The model should demonstrate a distinct improvement in cancer prediction compared to baseline methods [38].

Convolutional Neural Networks for Gene Expression Data

Application Note: CNNs, while traditionally applied to image data, can be successfully adapted to one-dimensional genomic data, such as gene expression profiles. Their ability to learn local patterns and hierarchical features makes them powerful for cancer type classification from RNA-seq data [39]. Studies have achieved high accuracy (93.9–95.0%) in classifying 33 different cancer types from TCGA data using various CNN architectures [39].

Experimental Protocol:

Data Preprocessing & Structuring:

- Input: Gene expression data (e.g., FPKM or TPM values from RNA-seq).

- Normalization: Apply log2(FPKM + 1) transformation and normalize the data [39].

- Gene Filtering: Filter out low-information genes (e.g., those with low mean expression or standard deviation).

- Input Structuring: For a 1D-CNN, structure the expression values of ~7,100 genes into a 1D vector. For a 2D-CNN, reshape the vector into a 2D matrix, though the gene order may not be biologically meaningful [39].

Model Architecture & Training:

- Architecture Choice:

- 1D-CNN: Uses 1D convolutional kernels that scan the input vector. This is often sufficient and computationally efficient [39].

- 2D-CNN: Reshapes data into a 2D matrix and uses 2D kernels.

- Training: Use a shallow architecture (one convolutional layer) to prevent overfitting, given the typically limited number of patient samples. The network typically includes a convolution layer, a max-pooling layer, and fully connected layers [39].

- Regularization: Employ dropout and L2 regularization to further mitigate overfitting.

- Architecture Choice:

Model Interpretation & Validation:

- Interpretation: Use guided saliency maps or other interpretability techniques to identify genes with the greatest influence on the classification outcome. This can reveal known and novel cancer marker genes [39].

- Validation: Perform robust k-fold cross-validation and test on independent datasets. Report accuracy, confusion matrices, and per-class metrics.

The workflow for implementing a 1D-CNN for gene expression classification is as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for ML-based Cancer Detection

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Data Repository | Provides a vast, publicly available collection of genomic, epigenomic, and clinical data from multiple cancer types for model training and validation. | [3] [39] |

| LinkedOmics | Data Repository | Offers multiomics data (e.g., methylation, somatic mutations) integrated with TCGA, facilitating multi-modal model development. | [3] |

| UK Biobank | Data Repository | A large-scale biomedical database containing genetic, lifestyle, and health information from participants, useful for developing broad population-level models. | [42] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Software Library | Provides model-agnostic interpretability, explaining the output of any ML model (e.g., XGBoost) by quantifying feature importance. | [38] [42] |

| Autoencoder | Algorithm | Used for unsupervised feature extraction and dimensionality reduction of high-dimensional genomic data (e.g., RNA-seq) prior to classification. | [3] |

| SMOTE | Algorithm | A synthetic oversampling technique to address class imbalance in datasets, preventing model bias toward majority classes. | [3] [41] |

| Appna | Appna, CAS:60189-44-8, MF:C14H18N4O4, MW:306.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| YM758 | YM758|If Channel Inhibitor|CAS 312752-85-5 | YM758 is a novel, specific sinoatrial node If current channel inhibitor for cardiovascular research. This product is for Research Use Only. | Bench Chemicals |

Cancer remains one of the most complex challenges in global healthcare, with accurate and early diagnosis being crucial for effective treatment and improved patient outcomes [3]. The inherent heterogeneity of cancer, where tumors can exhibit significant molecular differences even within the same type, complicates diagnosis and treatment planning [43]. Traditional single-omics approaches often fail to capture the complete biological picture of carcinogenesis, limiting their diagnostic accuracy [44].

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), particularly ensemble methods that blend multiple algorithms, have demonstrated remarkable potential in overcoming these limitations [45]. This case study examines the implementation of a high-accuracy blended ensemble framework for multi-cancer classification, focusing on practical implementation within the broader context of DNA sequence analysis and multi-omics data integration. We present a detailed analysis of the methodology, experimental protocols, and performance outcomes based on recent research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with actionable insights for developing robust cancer classification systems.

Background and Rationale

The Multi-Omics Approach in Cancer Classification

Multi-omics data integration has emerged as a powerful paradigm in cancer research, providing complementary insights into disease mechanisms across genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic dimensions [43]. The fundamental premise is that while single-omics data (e.g., RNA sequencing alone) can yield valuable insights, integrating multiple data types captures more comprehensive biological signatures, leading to improved classification accuracy [3] [46].

Key omics data types relevant to cancer classification include:

- RNA sequencing: Provides information about gene expression levels and transcriptome activity [3]

- DNA methylation: An epigenetic mechanism that regulates gene expression and shows characteristic changes in cancer [3] [46]

- Somatic mutation data: Reveals acquired genetic alterations that drive carcinogenesis [3]

- miRNA and lncRNA expression: Offers insights into regulatory networks that control cellular processes [43]

Studies have consistently demonstrated that models integrating multiple omics data types outperform single-omics approaches. For instance, one investigation showed that while RNA sequencing and methylation data individually achieved 96% accuracy, and somatic mutation data reached 81%, their integration boosted performance to 98% accuracy [3] [46].

Ensemble Learning in Cancer Diagnostics