From Docking to Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Molecular Interactions in Drug Discovery

This article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a complete framework for validating molecular docking results through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

From Docking to Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Molecular Interactions in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a complete framework for validating molecular docking results through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. As computational approaches become increasingly crucial in drug discovery, integrating these complementary techniques ensures more reliable predictions of binding affinities and complex stability. We explore the fundamental principles connecting docking and MD, present practical methodologies for implementation using popular software tools, address common troubleshooting scenarios, and establish rigorous validation protocols. By synthesizing insights from current literature and case studies, this guide serves as an essential resource for enhancing the accuracy and biological relevance of structure-based drug design, ultimately bridging the gap between computational predictions and experimental outcomes.

Understanding the Synergy: How Docking and MD Simulations Work Together in Drug Discovery

The Critical Role of Computational Validation in Modern Drug Development

In the contemporary drug development landscape, computational methods have evolved from supportive tools to indispensable components that streamline the discovery pipeline. These approaches, which include molecular docking, pharmacophore modeling, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enable researchers to rapidly identify and optimize potential drug candidates. However, the predictive power of these methods hinges on rigorous validation strategies that ensure their biological relevance and accuracy. As drug discovery embraces ultra-large virtual screening and artificial intelligence, establishing robust computational validation frameworks has become critical for translating in silico predictions into successful therapeutic outcomes. This guide examines the core computational techniques, their validation protocols, and their synergistic application in modern drug development.

Core Computational Methods and Comparative Performance

Modern drug discovery employs a suite of computational methods that operate on different principles and scales. Understanding their strengths, limitations, and appropriate validation contexts is essential for effective implementation.

Molecular Docking

Molecular docking predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (receptor). It is primarily used for virtual screening to identify potential hits from large compound libraries.

- Methodology: Docking programs such as DOCK, GOLD, and Glide use scoring functions to evaluate and rank ligand poses based on complementary interactions with the binding site [1].

- Key Applications: Initial hit identification, binding mode prediction, and structure-based drug design [2].

- Validation Consideration: Performance is highly dependent on the target's binding site characteristics and the accuracy of the scoring function [1].

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening (PBVS)

A pharmacophore model represents the essential structural features responsible for a ligand's biological activity. PBVS uses these abstract models to screen compound databases.

- Methodology: Models are often built from known active ligands or protein-ligand complex structures using tools like Catalyst or LigandScout. Screening identifies compounds that share the defined feature set [1].

- Key Applications: Scaffold hopping to discover novel chemotypes, pre-filtering for docking, and post-docking enrichment [1].

- Validation Consideration: Demonstrates high performance in retrieving actives, particularly when protein structural data is limited [1].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

MD simulations model the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing a dynamic view of molecular behavior that static structures cannot capture.

- Methodology: Simulations numerically solve Newton's equations of motion for a system of atoms, using force fields (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) to define interatomic forces. Software includes GROMACS, NAMD, and AMBER [3] [4] [5].

- Key Applications: Assessing binding stability, calculating free energies of binding, studying conformational changes, and validating docking poses [5].

- Validation Consideration: Requires careful parameterization and extensive sampling. Accuracy is critically dependent on the force field and must be validated against experimental data [3] [5].

Performance Comparison: PBVS vs. Docking-Based VS

A benchmark study across eight diverse protein targets provides quantitative performance data, measured by enrichment factor (EF) and hit rate (HR), which reflect the method's ability to prioritize active compounds over decoys [1].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Virtual Screening Methods

| Target | PBVS EF | DBVS EF (DOCK) | DBVS EF (GOLD) | DBVS EF (Glide) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | 4.92 | 1.23 | 1.85 | 1.64 |

| AChE | 4.05 | 2.32 | 2.14 | 2.41 |

| AR | 4.12 | 1.98 | 2.25 | 2.55 |

| DacA | 3.85 | 2.95 | 2.75 | 2.89 |

| DHFR | 3.95 | 2.11 | 2.33 | 2.67 |

| ERα | 4.25 | 2.45 | 2.51 | 2.88 |

| HIV-pr | 3.55 | 3.12 | 3.78 | 3.45 |

| TK | 3.88 | 2.67 | 2.72 | 2.91 |

| Average | 4.08 | 2.35 | 2.54 | 2.68 |

Table 2: Average Hit Rates at Different Top Fractions of Screened Database

| Method | Hit Rate @ 2% | Hit Rate @ 5% |

|---|---|---|

| PBVS | 42.5% | 38.2% |

| DBVS (DOCK) | 18.3% | 16.5% |

| DBVS (GOLD) | 21.1% | 18.9% |

| DBVS (Glide) | 23.4% | 20.7% |

The data demonstrates that PBVS generally outperformed DBVS across most targets, achieving higher enrichment factors and hit rates [1]. This suggests PBVS is a powerful method for initial ligand screening. However, the performance of DBVS methods varies by target and program, highlighting that the optimal tool is often target-dependent [1].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Computational predictions require robust experimental validation to confirm biological activity. The following protocols are commonly used to verify predictions from docking and MD simulations.

Orthogonal Biochemical and Biophysical Assays

A multi-pronged validation strategy is recommended to mitigate the limitations of any single assay [6].

- Binding Affinity Measurements: Use Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) to quantitatively measure the binding kinetics and thermodynamics of predicted interactions.

- Functional Activity Assays: Employ target-specific enzyme inhibition or cell-based reporter assays to determine if the binding event translates to a functional biological effect (e.g., agonism, antagonism).

- Structural Confirmation: Techniques like X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy (cry-EM) can provide atomic-level resolution of the ligand-target complex, directly validating the predicted binding pose from docking [2].

Experimental Validation of MD Simulations

Validating the physical accuracy of MD simulations is crucial for trusting their insights. A foundational approach involves comparing simulation outputs with experimental structural data [3].

- Protocol: A novel, model-independent method analyzes MD simulation data in the same way as experimental diffraction data. It determines the structure factors of the simulated system and reconstructs the overall transbilayer scattering-density profiles via Fourier analysis [3].

- Comparison Metrics: The simulated structures are evaluated against experimental data for key properties such as bilayer thickness, area per lipid, and molecular-component distributions [3].

- Outcome: This protocol provides a critical test of a force field's ability to reproduce experimental data, revealing discrepancies and guiding further force field development [3] [5].

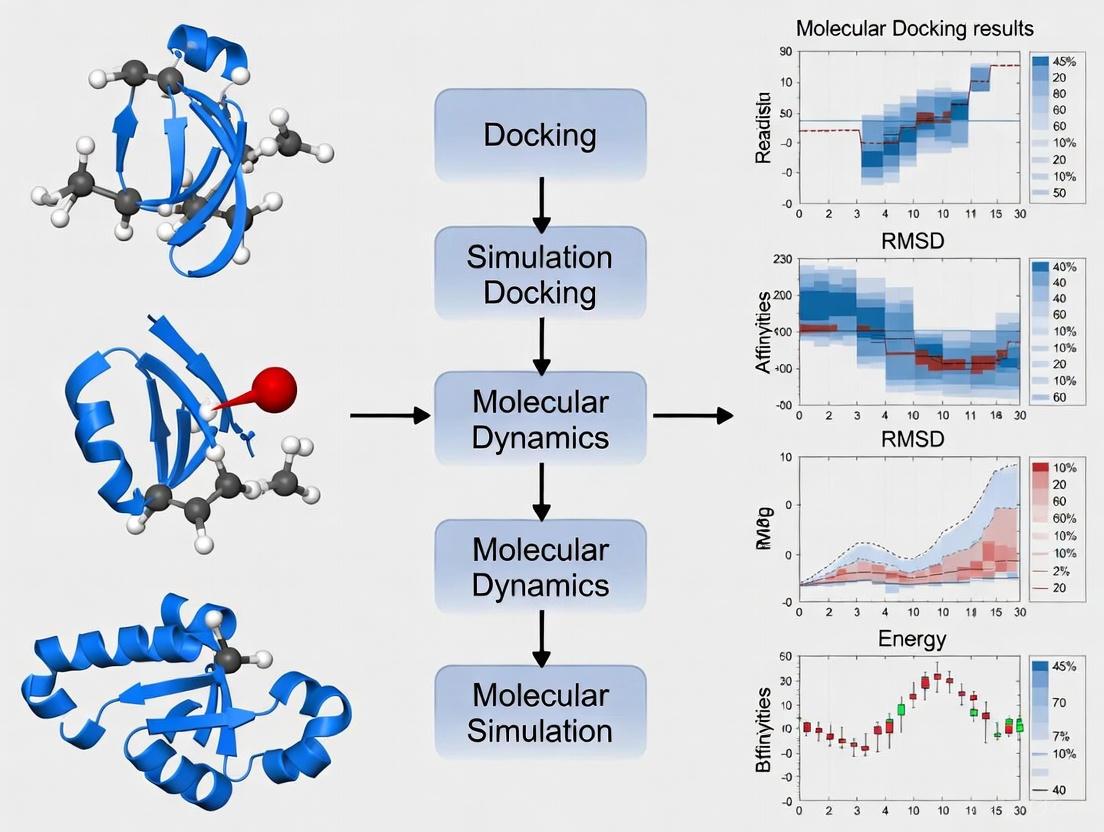

An Integrated Workflow for Computational Validation

Combining computational methods into a cohesive pipeline leverages their complementary strengths. The following workflow outlines a robust path from initial screening to dynamic validation.

Integrated Computational Validation Workflow

This integrated approach begins with pharmacophore-based virtual screening to efficiently reduce the chemical space, leveraging its high enrichment factors shown in Table 1 [1]. The top hits then undergo more computationally intensive docking-based virtual screening for precise pose prediction and scoring. The most promising complexes are finally subjected to MD simulations to assess the stability of the binding pose and calculate binding free energies, providing a dynamic validation that static docking cannot [5]. This step helps filter out false positives that may score well in docking but form unstable complexes. The final, critical step is experimental validation using the orthogonal assays described above [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of computational methods and subsequent validation relies on key software tools, force fields, and experimental resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Drug Development

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Software | Molecular dynamics simulation | High-performance MD simulations of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [3] [4]. |

| CHARMM36 | Force Field | Empirical molecular mechanics parameters | Provides accurate parameters for simulating lipid bilayers and proteins in MD [4]. |

| LigandScout | Software | Pharmacophore model generation | Creates 3D pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes for PBVS [1]. |

| Glide | Software | Molecular docking | Performs precision docking and scoring for virtual screening [1]. |

| ZINC20 | Database | Free ultralarge compound library | Provides access to billions of purchasable compounds for virtual screening [2]. |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web Server | Input generator for simulations | Simplifies the setup of complex simulation systems for various MD programs [4]. |

Computational methods are fundamentally reshaping drug development, but their predictive power is only as reliable as the validation frameworks that support them. The comparative data shows that pharmacophore-based screening offers high efficiency in enriching actives, while docking provides atomic-level insights into binding, and MD simulations deliver crucial dynamic context. An integrated workflow that strategically sequences these methods, culminating in rigorous experimental validation, creates a powerful and robust engine for discovering new therapeutics. As force fields continue to improve and computational power grows, the role of validation will only become more critical in ensuring that the rapid pace of in silico discovery translates confidently into clinical success.

Molecular docking is a foundational computational method in structure-based drug discovery that predicts how a small molecule (ligand) binds to a target protein receptor. This technique serves two primary objectives: to predict the binding affinity and three-dimensional orientation of small molecules within a receptor site, and to identify potential drug candidates from large chemical databases through virtual screening [7] [8]. The central premise involves sampling different conformations and orientations of the ligand within the protein's binding pocket and ranking these poses using scoring functions that estimate binding strength [9].

The methodology has evolved significantly from early rigid-body docking approaches, which treated both protein and ligand as fixed structures, to modern techniques that incorporate varying degrees of flexibility. This evolution acknowledges the "induced-fit" theory, where both ligand and receptor undergo conformational changes to achieve optimal binding [9] [8]. Today, molecular docking stands as an indispensable tool that reduces the cost and time of drug discovery by prioritizing the most promising candidates for experimental validation [10].

Molecular Docking Methodologies and Algorithms

Conformational Search Algorithms

Docking programs employ different conformational search strategies to explore the ligand's possible orientations and conformations within the binding site. These algorithms can be broadly classified into four categories:

Systematic Methods: These approaches exhaustively explore conformational space by systematically rotating rotatable bonds at fixed intervals. Incremental construction methods, used by FlexX and DOCK, break the ligand into fragments, dock rigid core fragments, and rebuild the molecule in the binding site. True systematic search algorithms, implemented in Glide and FRED, comprehensively explore all possible torsion angles but face exponential complexity growth with increasing rotatable bonds [7] [9].

Stochastic Methods: These techniques use random sampling to explore conformational space. Monte Carlo methods make random changes to ligand conformation and accept or reject them based on energy criteria and Boltzmann distribution probability. Genetic algorithms, used in AutoDock and GOLD, encode conformational degrees of freedom as "genes" that undergo mutation and crossover across generations, with docking scores serving as fitness functions [7].

Shape Matching Algorithms: These approaches, including DOCK, prioritize computational speed by emphasizing complementarity between ligand and binding site surfaces [8].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: While not typically used for initial docking due to computational cost, MD simulations serve as powerful conformational search tools that can capture induced-fit effects through pre-docking conformational sampling or post-docking refinement [7] [11].

Scoring Functions

Scoring functions are mathematical approximations used to predict binding affinity by evaluating protein-ligand interactions. They represent the sum of electrostatic and van der Waals energies, along with additional terms accounting for solvation effects, entropy, and specific interaction patterns [9]. These functions employ various approaches:

- Force Field-Based: Calculate energy terms using molecular mechanics force fields.

- Empirical: Parameterized using experimental binding affinity data.

- Knowledge-Based: Derived from statistical analyses of atom-pair frequencies in protein-ligand complexes.

Despite advancements, scoring remains a significant challenge in molecular docking, with functions often struggling to accurately predict absolute binding affinities while showing better performance for relative ranking of similar compounds [9].

Flexibility Considerations

The treatment of molecular flexibility represents a critical differentiator among docking approaches:

Rigid Docking: Treats both protein and ligand as fixed entities, considering only rotational and translational degrees of freedom. This approach is computationally efficient but biologically unrealistic for most systems [8].

Semi-Flexible Docking: Maintains a rigid protein while allowing ligand flexibility through rotatable bonds. This balanced approach offers improved accuracy over rigid docking while maintaining computational feasibility, making it the most common docking methodology [8].

Flexible Docking: Incorporates flexibility for both receptor and ligand, providing the most realistic representation but requiring substantial computational resources. Some implementations like "soft docking" implicitly account for flexibility by allowing limited atomic overlaps [8].

Comparative Analysis of Docking Software

Numerous molecular docking programs have been developed, each implementing different algorithms and scoring functions. The table below summarizes key characteristics of major docking software:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Molecular Docking Software

| Software | Algorithm Type | Flexibility Treatment | Scoring Function | Key Features | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [9] [10] | Stochastic (Genetic Algorithm) | Semi-flexible | Empirical & Knowledge-based | Hybrid scoring function with machine learning | Fast and reliable; good accuracy for pose prediction |

| GOLD [9] [10] | Stochastic (Genetic Algorithm) | Semi-flexible | Empirical (ChemScore) | Comprehensive conformational search | High docking accuracy; successful in virtual screening trials |

| Glide [7] [9] | Systematic | Semi-flexible | Empirical (GlideScore) | Hierarchical filters for speed | 90% pose prediction accuracy; exceptional for large databases |

| FlexX [9] [10] | Systematic (Incremental Construction) | Semi-flexible | Empirical | Fast incremental construction | Suitable for high-throughput virtual screening |

| DOCK [9] [12] | Shape-based | Semi-flexible | Force field-based | Geometric matching algorithm | Extensive validation history; handles large libraries |

| ZDOCK [13] [10] | FFT-based rigid body | Rigid | Shape complementarity + Electrostatics | Fast Fourier Transform correlation | Excellent for protein-peptide docking; incorporates desolvation energy |

| FRODOCK [13] | FFT-based rigid body | Rigid | Knowledge-based potential | Spherical harmonics properties | Top performer in blind protein-peptide docking benchmarks |

Performance Considerations

Docking accuracy is typically evaluated by the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between predicted and experimentally determined ligand positions, with values below 2.0 Å generally considered successful [9]. Benchmarking studies reveal that performance varies significantly based on the specific system and requirements:

For protein-small molecule docking, GOLD and Glide consistently achieve approximately 90% accuracy in pose prediction [9]. AutoDock Vina provides an optimal balance of speed and accuracy, particularly beneficial for virtual screening [10].

For protein-peptide docking, specialized tools show superior performance. FRODOCK achieves the best performance in blind docking, while ZDOCK excels in re-docking scenarios where binding sites are known [13].

Recent advancements incorporate machine learning to improve scoring functions and conformational sampling, addressing historical limitations in pose prediction and affinity estimation [7] [12].

Validation Through Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The Docking-MD Validation Workflow

Molecular docking provides initial binding hypotheses, but these static snapshots require validation through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that account for full protein flexibility and solvation effects. The integrated docking-MD workflow proceeds through several stages:

Graphviz: Docking-MD Validation Workflow

This workflow generates a more reliable assessment of binding stability and affinity than docking alone [11] [14].

Case Study: Streptococcus gallolyticus Drug Discovery

A recent study on Streptococcus gallolyticus demonstrates the power of combining docking with MD simulations. Researchers identified three druggable targets (GlmU, RpoD, and PPAT) using subtractive proteomics, then screened 10,000 natural compounds from the LOTUS database through molecular docking [15].

The top-ranking compounds (LTS001632 for GlmU, LTS0243441 for PPAT, and LTS0236112 for RpoD) underwent extensive MD simulations to validate complex stability and calculate binding free energies using MM-GBSA. This approach confirmed the docking predictions and provided quantitative affinity estimates, demonstrating how MD simulations complement docking by assessing the temporal stability and energetic landscape of predicted complexes [15].

Ensemble Docking Strategies

MD simulations enhance docking accuracy through ensemble docking, where multiple receptor conformations from MD trajectories are used as docking targets. This approach accounts for binding site flexibility and identifies ligands that stabilize different conformational states [11].

Table 2: MD Simulation Methods for Docking Validation

| Method | Purpose | Key Applications | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard MD [11] | Complex stability assessment | Pose validation, conformational sampling | Medium to High |

| Replica Exchange MD [11] | Enhanced conformational sampling | Overcoming energy barriers | High |

| MM/GBSA [15] [11] | Binding free energy estimation | Ranking docked compounds | Medium |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) [11] | Relative binding affinity | Lead optimization | Very High |

| Ensemble Docking [11] | Incorporating receptor flexibility | Virtual screening against dynamic targets | Medium |

Machine learning approaches are increasingly integrated with MD simulations to improve binding free energy predictions by guiding frame selection, refining energy terms, and optimizing resource allocation [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Docking Protocol

A reproducible molecular docking experiment follows these key steps:

Protein Preparation:

Ligand Preparation:

Binding Site Definition:

- Use known active site information when available

- Alternatively, employ cavity detection programs (GRID, SURFNET, DeepSite) [8]

Docking Execution:

- Select appropriate search algorithm and scoring function

- Generate multiple poses per ligand (typically 10-50)

- Apply constraints based on known interaction patterns if available [7]

Pose Analysis and Selection:

- Cluster similar conformations

- Visualize molecular interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts)

- Select top-ranked poses based on scoring function and interaction patterns [7]

MD Validation Protocol

Following docking, implement this MD validation protocol:

System Setup:

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in explicit solvent

- Add counterions to neutralize system charge

- Apply appropriate boundary conditions

Equilibration:

- Gradually heat system to target temperature (typically 300K)

- Apply positional restraints to protein and ligand

- Gradually release restraints while maintaining constant pressure

Production Simulation:

- Run unrestrained simulation for timescales sufficient for convergence (typically 50-500ns)

- Maintain constant temperature and pressure using thermostats and barostats

- Save trajectory frames at regular intervals for analysis [11]

Trajectory Analysis:

- Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of protein and ligand

- Monitor interaction persistence throughout simulation

- Identify stable binding modes and conformational changes

Binding Free Energy Calculation:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Docking and MD Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases [8] | PDB, AlphaFold Database | Source experimental and predicted structures | Public access |

| Chemical Compound Databases [15] [8] | DrugBank, ZINC, PubChem, LOTUS | Source small molecules for docking | Public access |

| Docking Software [9] [10] | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide, DOCK | Perform molecular docking | Commercial and free licenses |

| MD Simulation Packages [11] | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM | Run molecular dynamics simulations | Mostly open source |

| Analysis Tools [15] | PyMOL, VMD, Chimera | Visualize and analyze structures and trajectories | Mixed access models |

| Binding Site Detection [8] | DeepSite, CASTp, GRID | Identify potential binding pockets | Public servers and standalone |

| Force Fields [11] | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS | Parameterize molecular mechanics energy | Bundled with MD software |

Molecular docking provides powerful capabilities for predicting initial binding poses and estimating affinities, serving as an indispensable first step in structure-based drug discovery. However, docking results require validation through molecular dynamics simulations that account for full atomistic flexibility and solvation effects. The integration of these methodologies creates a robust framework for advancing drug discovery, with docking enabling high-throughput screening and MD providing physiological context and validation.

As both fields evolve—with docking benefiting from machine learning-enhanced scoring functions and MD leveraging specialized hardware for longer timescales—their synergy will continue to strengthen, offering increasingly reliable predictions of molecular interactions. This combined approach represents the current state-of-the-art in computational drug discovery, balancing computational efficiency with biological realism to accelerate the identification and optimization of therapeutic compounds.

Molecular docking serves as a fundamental computational technique in modern drug discovery, enabling the high-throughput prediction of how small molecule ligands interact with protein targets. However, its utility is fundamentally constrained by inherent limitations in scoring functions and the static nature of the structures it employs. Docking algorithms often struggle with accurately ranking binding poses and predicting binding affinities, as they typically rely on simplified physical models and cannot fully capture the dynamic protein-ligand interactions that occur in a physiological solution. The recognition of these shortcomings has established molecular dynamics (MD) simulations as an indispensable tool for the validation of molecular docking results. By providing a dynamic view of the binding process, MD simulations allow researchers to move beyond static snapshots and assess the stability and flexibility of protein-ligand complexes over time, thereby offering a more rigorous and biophysically realistic evaluation of potential drug candidates.

This guide objectively compares the performance of molecular dynamics simulations against traditional docking and other alternative methods for validating protein-ligand interactions. It synthesizes current research data and detailed experimental protocols to provide drug development professionals with a clear framework for integrating MD-based validation into their computational workflows.

Performance Comparison: MD Simulations vs. Docking and Other Methods

Quantitative Comparison of Key Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes the performance of molecular docking, MD simulations, and other computational methods across several key metrics relevant to the validation of protein-ligand complexes.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Computational Methods for Protein-Ligand Interaction Analysis

| Method | Binding Pose Stability Assessment | Binding Affinity Prediction Accuracy | Timescale | Explicit Solvent Treatment | Conformational Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Limited; cannot assess stability over time [16] | Approximate; often poor correlation with experiment [17] | Seconds to minutes | Implicit or absent | Single, static pose |

| MD Simulations | High; 94% of native poses maintained as stable [16] | Improved correlation with experiment via MMPBSA/GBSA [17] [18] | Hours to days | Explicit | Extensive, dynamic |

| Machine Learning Scoring | Varies with training data | Good for targets similar to training data; can overfit [19] | Minutes | Typically implicit | Limited to training set scope |

Key Insights from Comparative Studies

- Pose Stability and Decoy Rejection: A systematic study on 120 protein-ligand complexes demonstrated that while 94% of experimental (native) binding poses remained stable during MD simulations, a significant 38-44% of incorrect decoy poses generated by docking were successfully identified as unstable. This highlights MD's critical role in filtering out false positives from docking experiments [16].

- Binding Affinity Correlation: Large-scale datasets like PLAS-20k, which contains binding affinities for over 19,500 complexes derived from MD simulations followed by MM/PBSA calculations, show a better correlation with experimental values than traditional docking scores. This holds true even for diverse protein clusters and drug-like ligands, underscoring the predictive advantage of MD-based methods [17].

- Identifying Subtle Interaction Patterns: MD simulations excel at capturing dynamic interactions that are missed in static docking. For instance, a study on NDM-1 inhibitors revealed that a candidate compound (S904-0022) maintained stable interactions with key residues like Gln123 and His250 throughout a 300 ns simulation. This stable binding profile, corroborated by a favorable MM/GBSA binding free energy of -35.77 kcal/mol, provided a level of validation unattainable by docking alone [18].

Experimental Protocols for MD-Based Validation

Standard Workflow for Validation of Docking Results

The following diagram illustrates a typical integrated computational workflow for validating docking results through molecular dynamics simulations.

Detailed Methodological Steps

The workflow outlined above involves several critical steps, each with specific protocols:

System Preparation:

- Protein and Ligand Preparation: The protein structure, often from the PDB, is prepared by removing crystallographic water molecules, adding missing residues and hydrogen atoms, and assigning correct protonation states at physiological pH using tools like H++ or standard molecular visualization software [17] [20]. The ligand's 3D structure is optimized, and its force field parameters are generated using tools like

antechamberwith the GAFF2 force field [17]. - Solvation and Ionization: The protein-ligand complex is solvated in an explicit water box (e.g., TIP3P) with a buffer of at least 10 Å around the solute. Counterions are added to neutralize the system's net charge [17].

- Protein and Ligand Preparation: The protein structure, often from the PDB, is prepared by removing crystallographic water molecules, adding missing residues and hydrogen atoms, and assigning correct protonation states at physiological pH using tools like H++ or standard molecular visualization software [17] [20]. The ligand's 3D structure is optimized, and its force field parameters are generated using tools like

Simulation Setup:

- Energy Minimization: The system undergoes energy minimization (e.g., 1000-4000 steps) to remove steric clashes and bad contacts, often using the L-BFGS algorithm. This step may involve initial restraints on the protein backbone that are gradually released [17] [18].

- System Equilibration: The minimized system is gradually heated to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) and its density is equilibrated under constant pressure (1 atm). This is typically done in two phases: first in the NVT ensemble (constant volume and temperature) and then in the NPT ensemble (constant pressure and temperature). Restraints on the protein backbone are usually applied during initial equilibration and then removed [17].

Production Simulation and Analysis:

- Production Run: Multiple independent production simulations (typically ranging from 100 ns to 1 µs) are performed using a stable integrator like Langevin dynamics. Trajectories are saved at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) for subsequent analysis [16] [17].

- Stability Metrics: The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone and ligand heavy atoms is calculated to assess the overall stability of the complex. The root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of protein residues indicates flexible regions.

- Interaction Analysis: Hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and salt bridges are monitored over the simulation time to identify key interactions stabilizing the binding pose [20] [18].

- Binding Free Energy Calculation: The Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) or Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) method is commonly employed to calculate binding free energies from simulation snapshots. This provides a more rigorous estimate of binding affinity than docking scores [20] [18]. For instance, in the VEGFR-2/c-Met study, this method helped identify compounds with superior binding free energies compared to positive controls [20].

Case Study: Validating Dual VEGFR-2/c-Met Inhibitors

Detailed Workflow and Pathway Visualization

A recent study exemplifies the powerful synergy between docking and MD simulation. Researchers employed a comprehensive virtual screening approach to identify dual-target inhibitors for VEGFR-2 and c-Met, two critical kinases in cancer pathogenesis [20]. The process began with screening over 1.28 million compounds from the ChemDiv database using pharmacophore models and molecular docking. This was followed by extensive MD simulations and MM/PBSA calculations on the top hits to validate their binding stability and affinity [20].

The therapeutic relevance of these targets lies in their synergistic role in tumor angiogenesis and progression. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways involved, which the identified inhibitors aim to disrupt.

Quantitative Results from MD Validation

The MD simulation results provided critical validation that went beyond the initial docking scores:

Table 2: MD Simulation and Binding Energy Results for Identified VEGFR-2/c-Met Inhibitors [20]

| Compound ID | Target Protein | Key Stable Interactions Observed | Binding Free Energy (MM/PBSA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound17924 | VEGFR-2 | Not specified in detail, but superior to positive control | More favorable than positive control |

| Compound17924 | c-Met | Not specified in detail, but superior to positive control | More favorable than positive control |

| Compound4312 | VEGFR-2 | Not specified in detail, but superior to positive control | More favorable than positive control |

| Compound4312 | c-Met | Not specified in detail, but superior to positive control | More favorable than positive control |

The study concluded that both compounds showed superior binding free energies compared to the positive ligands, confirming their potential as promising drug candidates. This conclusion could not have been reached with docking alone, underscoring the value of MD for lead optimization and validation [20].

Successful execution of MD-based validation pipelines relies on a suite of software tools, databases, and computational resources. The following table details key components of the modern computational scientist's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for MD-Based Validation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Source of experimental 3D structures of target proteins and protein-ligand complexes [20]. |

| ChemDiv Database | Database | Commercial library of small molecules for virtual screening [20] [18]. |

| AutoDock Vina / AutoDockTools | Software | Widely used programs for molecular docking and pose generation [18]. |

| AMBER (ff14SB, GAFF2) | Software / Force Field | Suite of biomolecular force fields and simulation programs for MD [17]. |

| GROMACS / OpenMM | Software | High-performance MD simulation engines for running production trajectories [17] [18]. |

| MMPBSA.py / MMGBSA.py | Software | Tools for calculating binding free energies from MD trajectories using MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods [17]. |

| PLAS-20k Dataset | Dataset | A publicly available dataset of binding affinities for 19,500 protein-ligand complexes derived from MD simulations, useful for benchmarking [17]. |

In the realm of computational drug discovery, accurately predicting how small molecules interact with biological targets represents a fundamental challenge. The reliability of these predictions hinges on three interconnected theoretical concepts: force fields that describe the physical forces between atoms, scoring functions that rapidly evaluate binding affinity, and sampling algorithms that explore possible binding orientations. While molecular docking provides initial predictions, the scientific community increasingly recognizes that validation through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provides a more rigorous, physics-based assessment of docking results. This guide objectively compares the performance of these methodologies, demonstrating how an integrated approach leveraging their respective strengths leads to more reliable outcomes in structure-based drug design.

The critical limitation of docking arises from its heavy reliance on scoring functions, which often make simplifying assumptions to achieve computational speed. Research systematically validates that integrating MD simulations can significantly improve docking results. One study demonstrated a 22% improvement in ROC AUC (from 0.68 to 0.83) in distinguishing active from decoy compounds in the DUD-E dataset when docking results from AutoDock Vina were refined through high-throughput MD simulations [21]. This performance gain stems from MD's ability to account for critical physical phenomena such as solvent effects, entropic contributions, and protein flexibility that are often oversimplified in standard docking scoring functions [21] [22].

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Force Fields: The Physics-Based Foundation

Force fields are computational models that describe the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of its atomic coordinates, providing the fundamental physics basis for both MD simulations and some scoring functions [23]. They use mathematical functions and parameters to approximate the forces governing atomic interactions.

The general functional form of a molecular mechanics force field can be decomposed into bonded and non-bonded interaction terms:

Bonded Interactions: These include energy terms for atoms connected by covalent bonds:

Non-bonded Interactions: These describe interactions between atoms not directly bonded:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Biomolecular Force Fields

| Force Field | Parameterization Approach | Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM [21] | Mixed quantum mechanics and experimental data | Balanced treatment of proteins and lipids | MD simulations of biomolecular systems |

| AMBER [24] | Emphasizes accurate nucleic acid parameters | Excellent for DNA/RNA complexes | Protein-ligand simulations |

| GROMOS | Parameterized against condensed phase data | Strong performance for folding studies | Biomolecular simulations in aqueous environment |

| OPLS-AA | Optimized for liquid properties | Accurate for organic molecules | Ligand parameterization |

Scoring Functions: Rapid Binding Evaluation

Scoring functions are mathematical approximations used to predict the binding affinity between molecules after docking. They prioritize computational speed over physical completeness, enabling the rapid screening of thousands to millions of compounds [25]. These functions fall into four primary categories:

Force Field-Based: Estimate binding affinity by summing intermolecular van der Waals and electrostatic interactions from force fields, sometimes including implicit solvation terms [25] [26]. Examples include DOCK and AutoDock scoring functions.

Empirical: Use weighted sums of interaction types (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, etc.) with coefficients fitted to experimental binding affinity data [25]. Examples include Glide, ChemScore, and the DockTScore family.

Knowledge-Based: Derive statistical potentials from structural databases under the assumption that frequently observed atom pair interactions are energetically favorable [25]. Examples include PMF, DrugScore, and ITScore.

Machine Learning-Based: Utilize algorithms that learn complex relationships between structural features and binding affinities without assuming a predetermined functional form [27] [22] [25]. These consistently outperform classical scoring functions in binding affinity prediction, particularly when sufficient target-specific data is available [25].

Sampling Methods: Exploring Structural Landscapes

Sampling algorithms explore the conformational and orientational space available to the ligand and protein. While this guide focuses primarily on force fields and scoring, sampling efficiency directly impacts practical performance. Key approaches include:

- Systematic Search: Methodically explores all rotational and translational degrees of freedom

- Stochastic Algorithms: Use random changes (Monte Carlo, genetic algorithms) to explore space

- Molecular Dynamics: Simulates physical motion through numerical integration of Newton's equations

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Comparative Performance of Scoring Function Types

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Scoring Function Categories

| Scoring Function Type | Binding Mode Prediction | Binding Affinity Prediction | Virtual Screening | Computational Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force Field-Based | Moderate | Moderate (improves with implicit solvation) | High false positive rate for charged compounds | Fast |

| Empirical | Good | Variable across target classes | Good with target-matched training | Very fast |

| Knowledge-Based | Good to excellent | Limited correlation with affinity | Good balance of accuracy/speed | Fast |

| Machine Learning | Excellent with sufficient data | Best overall performance [22] | State-of-the-art enrichment [25] | Fast prediction (slow training) |

The performance heterogeneity across different target classes has prompted the development of target-specific scoring functions. For example, specialized functions for proteases and protein-protein interactions (PPIs) have demonstrated superior performance compared to general-purpose functions [22]. The DockTScore function, which incorporates optimized MMFF94S force-field terms alongside solvation and lipophilic interaction terms, showed competitive performance on DUD-E datasets, particularly for its intended target classes [22].

Quantitative Validation Through MD Integration

The integration of molecular dynamics simulations provides a robust method for validating and improving docking results. A comprehensive study evaluating 56 protein targets from the DUD-E dataset demonstrated this approach quantitatively:

Table 3: Performance Improvement of Docking with MD Refinement

| Metric | AutoDock Vina Alone | With MD Refinement | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROC AUC | 0.68 | 0.83 | +22% |

| Robust Performance | Variable across protein classes | Consistent across 7 protein classes | Significant |

| Binding Mode Quality | Dependent on scoring function | Moderate refinement observed | Enhanced |

This high-throughput MD method simulated protein-ligand complexes from docking results, evaluating ligand binding stability using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) throughout the trajectories. The physics-based approach of MD simulations successfully discriminated between correct and incorrect binding modes, with correctly predicted binding modes demonstrating greater stability during simulations [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

High-Throughput MD Validation Protocol

The workflow for validating docking results through MD simulations involves several standardized steps that ensure reproducible results:

Initial Docking: Protein receptors and ligands are prepared using standard protocols with AutoDock Vina, treating receptors as rigid and ligands as flexible. The search space is determined based on native ligand coordinates from crystal structures (cubic box with 22.5 Å edges) [21].

System Preparation: Protein-ligand complexes are processed using automated scripts (Python) that interface with CHARMM-GUI to generate MD simulation systems. Ligand topology and parameters are generated using CGenFF [21].

Solvation and Neutralization: Systems are solvated in a cubic TIP3P water box extending 10 Å from the protein and neutralized with K⁺ and Cl⁻ ions under periodic boundary conditions [21].

Force Field Application: Simulations use CHARMM36m force field with an NPT ensemble (constant particle number, pressure, and temperature) maintained using a Langevin thermostat [21].

Electrostatics and Constraints: Particle-mesh Ewald method handles electrostatic interactions, while hydrogen atoms are constrained using the SHAKE algorithm [21].

Simulation Execution: Systems undergo minimization (5,000 steps steepest descent), equilibration (1 ns NVT), and production runs using OpenMM [21].

Trajectory Analysis: Ligand binding stability is evaluated by calculating RMSD relative to initial docking structures, aligning protein structures but not ligands [21].

Target-Specific Scoring Function Development

The development of specialized scoring functions for specific target classes follows a rigorous protocol:

Dataset Curation: For protease-specific functions, compounds are selected from PDBbind based on Enzyme Commission numbers (ranging 3.4.11.0-3.4.25.69). For PPI inhibitors, high-resolution complexes are carefully curated, removing structures with resolution >2.5 Å or covalent ligands [22].

Structure Preparation: Protein Preparation Wizard in Maestro assigns protonation states using ProtAssign and PROPKA, considering bound ligands. Ligand protonation and tautomeric states are calculated with Epik. Metal ions are treated as cofactors, and waters are removed [22].

Descriptor Calculation: Physics-based terms include MMFF94S force field energy components, solvation and lipophilic interaction terms, and ligand torsional entropy contributions [22].

Model Training: Multiple linear regression ensures physical interpretability, while non-linear models (SVM, random forest) capture complex relationships without overfitting [22].

Validation: Functions are tested on independent test sets and DUD-E datasets to evaluate affinity prediction and virtual screening performance [22].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Workflow Integrating Docking with MD Validation

Classification of Scoring Functions

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Molecular Docking and Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [21] | Docking Program | Predicts binding modes and scores | Initial virtual screening |

| CHARMM-GUI [21] | Web Server | Prepares MD simulation systems | System setup for MD validation |

| CHARMM36m [21] | Force Field | Describes molecular interactions | Physics-based MD simulations |

| CGenFF [21] | Parameterization | Generates ligand parameters | MD setup for small molecules |

| OpenMM [21] | MD Engine | Performs high-throughput simulations | Production MD runs |

| PDBbind [22] | Database | Curated protein-ligand complexes | Training/scoring function development |

| DUD-E [21] | Benchmark Set | Directory of useful decoys | Method validation and testing |

| MMFF94S [22] | Force Field | Describes small molecule energetics | Physics-based scoring terms |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that while classical scoring functions provide computational efficiency for initial screening, their limitations in accurately predicting binding affinities necessitate validation through more rigorous methods. The integration of molecular dynamics simulations addresses key weaknesses in docking approaches by incorporating critical physical effects like explicit solvation, entropic contributions, and full flexibility.

The empirical evidence clearly shows that combining docking with MD validation improves performance substantially, with a demonstrated 22% increase in ROC AUC for distinguishing active from decoy compounds [21]. Furthermore, the development of target-specific scoring functions, particularly those incorporating physics-based terms and machine learning, shows promise for addressing the performance heterogeneity across different protein classes [22].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparative analysis suggests a practical workflow: utilize rapid docking and scoring for initial screening, followed by MD simulation validation for top candidates. This integrated approach leverages the respective strengths of each methodology while mitigating their individual limitations, ultimately leading to more reliable predictions in structure-based drug design.

Molecular docking has established itself as a cornerstone of structure-based drug discovery, providing computational predictions of how small molecules interact with biological targets at the atomic level. By simulating the binding orientation and affinity of ligands within protein binding sites, docking offers an efficient method for virtual screening and lead compound optimization [10]. However, conventional docking approaches predominantly rely on static protein structures, typically derived from X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy, which present an inherent limitation: biological systems are fundamentally dynamic. Proteins exist as ensembles of conformations, with side chains, loops, and even domains in constant motion—a reality that static snapshots cannot capture [28] [29]. This simplification often leads to inaccurate binding mode predictions, particularly when ligands induce conformational changes through "induced fit" mechanisms, more accurately described as conformational selection where ligands stabilize pre-existing protein conformations [29].

The integration of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with docking results has emerged as a powerful methodology to bridge this resolution gap. MD simulations model system motions over time, accounting for protein flexibility, solvent effects, and the dynamic nature of binding interactions that static docking cannot resolve [28]. This combination creates a powerful pipeline: docking rapidly screens thousands of compounds, while MD simulations validate and refine the most promising complexes, assessing their stability and providing more accurate binding free energy estimates [30] [31]. This review comprehensively compares current molecular docking software and demonstrates, through experimental data and protocols, how MD simulations serve as an essential validation tool, transforming static predictions into dynamic binding insights across various drug discovery applications.

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Docking Software

The performance of docking programs varies significantly depending on the target protein and ligand characteristics. Understanding these differences is crucial for selecting the appropriate tool for a specific research application.

Key Docking Software and Their Distinctive Features

Table 1: Comparison of Key Molecular Docking Software

| Software | Search Algorithm | Scoring Function | Flexibility Handling | Best Use Cases | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [10] [24] | Hybrid global/local optimization | Empirical, machine-learning enhanced | Flexible ligand, rigid receptor | High-throughput virtual screening, general-purpose docking | Open-source, free |

| GOLD [29] | Genetic Algorithm (GA) | ChemPLP, GoldScore, ASP | Flexible ligand, optional flexible protein side chains | High-accuracy pose prediction, lead optimization | Commercial |

| FRED (OEDocking) [29] [32] | Fast Rigid Exhaustive Docking | Chemgauss4, Shapegauss | Pre-generated ligand conformer ensemble | Ultra-high-throughput virtual screening | Commercial |

| Glide [10] | Hierarchical filter system | SP, XP scoring functions | Flexible ligand, grid-based receptor | Induced-fit docking, accurate binding mode prediction | Commercial |

| Surflex-Dock [29] | Fragment-based construction (Protomol) | Hammerhead scoring function | Flexible ligand, partial protein flexibility | De novo design, structure-based drug design | Commercial |

Performance Evaluation in Pose Prediction and Virtual Screening

Independent comparative studies provide critical insights into the practical performance of these tools. A landmark study evaluating docking routines for the transmembrane protein SERCA (sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase) compared GOLD, AutoDock, Surflex-Dock, and FRED [29]. The evaluation criteria included docking accuracy (using crystal structures as references), reproducibility, and correlation between docking scores and known bioactivities. The study found that GOLD and FRED provided the best overall results in accurately reproducing the known binding poses of inhibitors like thapsigargin and cyclopiazonic acid [29]. Notably, allowing for conformational flexibility in the binding site during docking runs did not yield a significant improvement in results for this particular target, highlighting that the benefits of flexible receptor docking are system-dependent [29].

For virtual screening, the speed and enrichment power are paramount. FRED (OpenEye OEDocking) excels in this domain, implementing a rigid docking approach that uses pre-generated conformational ensembles of ligands, making it exceptionally fast for screening massive compound libraries [32]. One study described FRED as "by far the fastest docking tool and thus particularly suitable for ultrahigh-throughput docking," leading to the discovery of a validated 2.7 nM inhibitor of BChE, a target for Alzheimer's disease [32]. AutoDock Vina strikes a notable balance between speed and accuracy, making it a popular choice for academic research and initial screening campaigns [10] [24].

Experimental Protocols for Docking Validation via Molecular Dynamics

The following section details a standardized workflow for transitioning from static docking predictions to dynamically validated complexes, incorporating specific protocols from recent literature.

Standardized Workflow for Integrated Docking and MD Validation

The general process for validating docking results with MD simulations follows a logical sequence from system preparation to analysis, as demonstrated in multiple recent studies [30] [31] [24].

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

System Preparation and Docking

Protein and Ligand Preparation: The crystal structure of the target protein is obtained from the Protein Data Bank. Water molecules and heteroatoms not involved in binding are typically removed, followed by the addition of hydrogen atoms and assignment of partial charges (e.g., Kollman charges for AutoDock, AMBER ff14SB for simulation-ready structures) [31] [24]. The ligand structure is energy-minimized using force fields like MMFF94 [31].

Molecular Docking: Docking is performed using tools like AutoDock Vina or GOLD into a defined grid box encompassing the binding site. For instance, in a study of phytochemicals against the Androgen Receptor for triple-negative breast cancer, virtual screening was performed using PyRx (with AutoDock Vina) after filtering compounds by Lipinski's Rule of Five [24]. Multiple poses are generated and ranked by their docking scores (e.g., binding affinity in kcal/mol).

Molecular Dynamics Simulation and Analysis

System Setup and Equilibration: The top-ranked docked complex is solvated in a water box (e.g., TIP3P water model) with ions added to neutralize the system. The system is energy-minimized and gradually heated to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) during a equilibration phase with positional restraints on the protein and ligand [30] [31].

Production MD and Analysis: Unrestrained production simulations are run for a sufficient timescale (typically 50-100 nanoseconds or more) using software like Desmond (Schrödinger) or GROMACS [30] [31]. The stability of the simulation is assessed by calculating the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone and ligand atoms. Key protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) are monitored throughout the trajectory to verify the stability of the docking-predposed pose [31] [24].

Binding Free Energy Validation: The Molecular Mechanics with Generalised Born and Surface Area Continuum Solvation (MM-GBSA) or Poisson-Boltzmann (MM-PBSA) method is often applied to snapshots from the MD trajectory to calculate binding free energy, providing a more robust affinity estimate than docking scores alone [24]. A study on Molnupiravir binding to bovine serum albumin used triplicate 100 ns simulations followed by thermodynamic analysis to confirm the spontaneous nature of binding, demonstrating the power of this approach [31].

Case Studies: Experimental Data Supporting the Docking-MD Workflow

SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) Inhibitor Screening

A comprehensive study screened 200 natural antiviral compounds against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB: 6LU7) using AutoDock 4.2.6 [30]. The top compounds, including theaflavin-3-3'-digallate (binding energy: -12.41 kcal/mol; Ki = 794.96 pM) and rutin (binding energy: -11.33 kcal/mol; Ki = 4.98 nM), were subjected to 50 ns MD simulations. The simulations confirmed the conformational stability of the complexes, with stable RMSD values (<2 Å) and persistent hydrogen bonding with key catalytic residues (CYS 145 and HIS 41), validating the docking predictions and providing confidence in the inhibitory mechanism [30].

Binding Mechanism of Molnupiravir to Bovine Serum Albumin

Research on the antiviral drug Molnupiravir (MOL) combined multiple spectroscopic techniques with docking and MD to elucidate its binding to Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)—a key pharmacokinetic determinant [31]. Docking with AutoDock4.2.6 predicted binding to site II of BSA, which was confirmed by competitive site-marker experiments. Subsequent triplicate 100 ns MD simulations demonstrated the stability of the MOL-BSA complex, with the ligand remaining in its binding site and interacting predominantly with tyrosine residues. This integrated approach provided a deeper mechanistic understanding of the drug's transport and distribution profile [31].

Phytochemical Lead Identification for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

In this study, the Androgen Receptor (AR) was identified as a novel target for triple-negative breast cancer [24]. Virtual screening of phytochemicals against AR (PDB: 1E3G) using PyRx identified 2-hydroxynaringenin as a top hit. MD simulations over 100 ns revealed that the AR-2-hydroxynaringenin complex maintained structural stability with a stable binding affinity of -42.5 kcal/mol calculated via MM-GBSA. This confirmed the docking predictions and established the phytochemical as a promising lead molecule worthy of further experimental investigation [24].

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Findings from Case Studies

| Case Study / Target | Primary Docking Software | MD Simulation Length | Key Validation Metric from MD | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [30] | AutoDock 4.2.6 | 50 ns | Stable protein-ligand RMSD; maintained H-bonds with catalytic dyad | Confirmed mechanism of inhibition for top hits |

| Molnupiravir-BSA [31] | AutoDock 4.2.6 | 3 x 100 ns | Stable binding pose in site II; interactions with Tyr residues | Elucidated pharmacokinetic binding mechanism |

| Androgen Receptor (TNBC) [24] | AutoDock Vina (via PyRx) | 100 ns | Stable complex (low RMSD); MM-GBSA affinity: -42.5 kcal/mol | Identified 2-hydroxynaringenin as a potential lead |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful execution of a docking-MD validation pipeline requires a suite of specialized software tools and resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Item Name | Category | Primary Function | Example Use in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [10] [24] | Docking Software | Predicts ligand binding modes and affinities | Initial virtual screening and pose generation. |

| GOLD [29] | Docking Software | Genetic algorithm-based docking with high pose accuracy | Lead optimization and high-accuracy pose prediction. |

| FRED (OEDocking) [32] | Docking Software | Ultra-fast, exhaustive rigid docking for large libraries | Virtual screening of millions of compounds. |

| Desmond [30] [31] | MD Simulation Software | Performs all-atom molecular dynamics simulations | System equilibration, production MD runs, and trajectory analysis. |

| GROMACS | MD Simulation Software | High-performance MD simulation package (open-source) | Alternative for running production MD simulations. |

| AMBER ff14SB [24] | Force Field | Parameters for simulating proteins and nucleic acids | Energy minimization and MD simulation of the protein-ligand system. |

| TP3P Water Model [31] | Solvation Model | A transferable intermolecular potential for simulating water molecules | Solvation of the simulation system in a water box. |

| MM-GBSA/PBSA [24] | Analysis Method | Calculates binding free energies from simulation snapshots | Post-MD validation of binding affinity. |

The integration of molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations represents a paradigm shift in computational drug discovery, effectively bridging the gap between static structural snapshots and the dynamic reality of biological systems. While docking programs like AutoDock Vina, GOLD, and FRED provide unparalleled efficiency for initial screening and pose prediction, their results require validation in a dynamic context. As demonstrated by the consistent methodology across multiple case studies, MD simulations provide this critical validation, assessing the stability of docked complexes, revealing detailed binding mechanisms, and offering more reliable affinity estimates through MM-GBSA/PBSA. This powerful combined protocol—from docking to dynamic validation—has proven its value across diverse therapeutic areas, from antiviral development to oncology, and will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone of rational drug design for the foreseeable future.

Molecular docking is a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, used to predict how small molecules interact with biological targets. However, its utility is often limited by the accuracy of scoring functions and the common simplification of treating the receptor as a rigid body. This guide examines how integrating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations as a validation step addresses these limitations, providing a more robust framework for predicting ligand binding. Through detailed case studies and quantitative comparisons, we demonstrate that this combined approach significantly enhances the reliability of virtual screening outcomes, offering a more physics-based assessment of binding stability and affinity.

Case Study 1: Large-Scale Validation on Diverse Protein Targets

Experimental Protocol

This study established a high-throughput workflow to evaluate the benefit of MD in improving docking results from AutoDock Vina [21]. The protocol was systematically applied to 56 protein targets from the DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) dataset, spanning seven protein classes including kinases, proteases, and nuclear receptors [21].

- Initial Docking: For each target, 5 active and 5 decoy compounds were docked using AutoDock Vina with a rigid receptor and flexible ligands. The search space was a cubic box centered on the native ligand's coordinates [21].

- System Setup for MD: The top-ranked docking pose for each complex was processed using a Python script and CHARMM-GUI to automate the generation of MD simulation systems. Systems were solvated in a TIP3P water box, neutralized with ions, and described by the CHARMM36m force field [21].

- MD Simulation and Analysis: Each system underwent energy minimization, equilibration, and a production run. The key metric for evaluating binding was the ligand root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), calculated relative to the initial docking pose after aligning the protein backbone. Stable binding was indicated by low ligand RMSD values [21].

Performance and Impact

The study provided a direct, large-scale comparison of docking and MD validation performance. The results are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Docking and MD Validation on the DUD-E Dataset

| Method | AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve) | Key Metric | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina (Docking Alone) | 0.68 | Docking Score | Baseline performance [21] |

| Docking + MD Validation | 0.83 | Ligand Stability (RMSD) | 22% improvement in AUC [21] |

| MD Performance | Robust | Ligand RMSD | Consistent improvement across all 7 protein classes tested [21] |

This quantitative data demonstrates that MD simulations significantly improve the ability to distinguish true binders from decoys. The post-processing analysis based on ligand stability during the simulation proved to be a more reliable indicator of binding than the initial docking score alone [21].

Case Study 2: Fragment-Based Screening for SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease

Experimental Protocol

This research employed a multi-tiered workflow for fragment-based virtual screening against the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro), integrating docking with more advanced free energy calculations [33].

- Ligand Preparation & Docking: An initial set of ~50,000 candidate compounds was generated from fragment hits using the Fragalysis network. After enumerating charge states and generating 3D conformers, compounds were docked using rDock into 22 different crystal structures of Mpro [33].

- Pose Filtering and Scoring: The millions of generated docking poses were first filtered using the SuCOS score, which measures the 3D overlap between a docking pose and an experimental fragment structure. This ensured poses were biologically relevant. Poses were also scored using the deep learning-based TransFS tool [33].

- Free Energy Validation: The top ~200 compounds from docking were advanced to free energy calculations using the MMGBSA method, running an ensemble of simulations totaling 5 ns per compound. A final subset of the top 50 compounds was subjected to even more rigorous dissipation-corrected Targeted MD (dcTMD) simulations, requiring 50 ns per compound [33].

Performance and Impact

This case study exemplifies a practical pipeline where docking handles the high-throughput screening, while successive rounds of more computationally intensive simulations are used to validate and refine the results.

Table 2: Workflow for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitor Screening

| Stage | Tool/Method | Key Function | Validation Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pose Generation | rDock | High-throughput molecular docking | Generates initial binding hypotheses [33] |

| 2. Pose Validation | SuCOS, TransFS | Compares poses to experimental fragments; AI-based scoring | Filters out unrealistic poses from docking [33] |

| 3. Affinity Validation 1 | MMGBSA (via GROMACS) | End-state free energy method | Medium-throughput ranking of binding affinity [33] |

| 4. Affinity Validation 2 | dcTMD (via GROMACS) | Path-dependent free energy method | High-accuracy affinity calculation for top candidates [33] |

This workflow, implemented within the Galaxy platform, highlights how MD-based free energy methods serve as a critical validation step after docking, providing a more accurate estimate of binding affinity that guides the selection of compounds for experimental testing [33].

Case Study 3: Binding Site Characterization for the 1EAG Protease

Experimental Protocol

This study focused on the precise characterization of the binding pocket in the Candida albicans 1EAG protease as a essential prerequisite for validating docking studies [34].

- Binding Site Analysis: The 3D structure of protease 1EAG was analyzed to identify key residues within 3–5 Å of its co-crystallized ligand. The study characterized 12 key active-site residues by their chemical properties (polar, hydrophobic, aromatic) and their functional roles in hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking, and hydrophobic interactions [34].

- Pharmacophore Modeling: The spatial organization of the pocket was translated into a simplified pharmacophore model, identifying features like hydrogen bond donors/acceptors and hydrophobic regions. The analysis identified ASP32 as a catalytic hotspot and TYR84 and TYR225 as key for ligand stabilization [34].

Performance and Impact

While this study primarily established a framework for docking validation, it underscores a critical principle: accurate docking and its subsequent MD validation depend entirely on a correct definition of the binding site. The detailed pocket characterization provides a structural benchmark against which docking poses and their stability during MD can be evaluated [34]. A poorly defined site leads to unreliable docking results that no amount of MD can correct, a concern echoed in a recent perspective criticizing the inappropriate use of "blind docking" across the entire protein surface without validation [35].

Comparative Analysis of Docking-Validation Protocols

The following table synthesizes the methodologies and key outcomes from the featured case studies, providing a direct comparison of the docking software, validation tools, and their performance.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Docking and MD Validation Protocols

| Case Study | Docking Software | Validation Method | Key Performance Metric | Impact/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DUD-E Benchmark | AutoDock Vina | HT MD & Ligand RMSD | ROC AUC | 22% improvement in binder vs. decoy discrimination [21] |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro | rDock | MMGBSA & dcTMD | Free Energy Ranking | Tiered workflow for prioritizing compounds from 50,000 candidates [33] |

| 1EAG Protease | (Framework) | Pocket Pharmacophore | Site Characterization | Provides a reproducible framework for validating docking poses [34] |

| Blind Docking Critique | (Multiple) | (Not specified) | Success Rate (RMSD <2Å) | Highlights failure of blind docking (34-47% success) vs. site-specific docking (90.2% success) [35] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key software tools and resources that form the foundation of integrated docking-MD workflows.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Software Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [21] [9] | Docking Software | Predicts binding poses and scores for ligand-receptor complexes. |

| rDock [33] | Docking Software | Open-source tool for high-throughput virtual screening. |

| GROMACS [33] [21] | MD Simulation Software | Performs molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations. |

| CHARMM-GUI [21] | Web-Based Platform | Automates the setup and parameterization of complex systems for MD simulations. |

| OpenBabel [33] | Chemoinformatics Tool | Handles chemical format interconversion and protonation state preparation. |

| Galaxy [33] | Workflow Management System | Provides a reproducible, scalable platform for assembling and executing computational pipelines. |

| PyMOL Plugin [36] | Visualization & Analysis | Integrates docking setup and results visualization within the PyMOL molecular graphics environment. |

| DUD-E Dataset [21] | Benchmarking Database | Provides a benchmark set of protein targets with known actives and decoys to test method performance. |

Visualizing the Integrated Workflow

The integrated docking and MD validation process can be summarized in a logical workflow, as depicted in the diagram below.

The case studies presented provide compelling evidence that molecular docking, while powerful, should not be the final step in a computational screening campaign. The integration of Molecular Dynamics simulations addresses critical weaknesses in docking, particularly related to scoring function inaccuracies and the lack of receptor flexibility. As demonstrated quantitatively, this combined approach offers a more reliable and physically realistic method for validating docking results, ultimately strengthening the decision-making process in structure-based drug design and increasing the likelihood of experimental success.

Practical Implementation: Setting Up Your Integrated Docking-MD Validation Pipeline

The process of drug discovery has been fundamentally transformed by computational methods, with molecular docking and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations emerging as cornerstone techniques. Molecular docking serves as a high-throughput tool for predicting the predominant binding mode(s) of a small molecule ligand within a protein's active site, providing initial binding affinity estimates. However, docking often treats proteins as rigid entities and offers a static snapshot of binding, which limits its accuracy in capturing the dynamic nature of biomolecular interactions. This is where MD simulations provide critical complementary value, enabling researchers to model the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, thereby offering insights into conformational changes, binding stability, and the true thermodynamic properties of ligand-receptor complexes.

The integration of these methods creates a powerful pipeline that leverages the strengths of both approaches. Docking rapidly screens thousands to millions of compounds, identifying promising candidates, while MD simulations subsequently validate and refine these predictions by assessing their stability under more biologically realistic conditions. This workflow is particularly crucial in modern drug development, where understanding binding mechanisms and residence times can significantly impact candidate selection. Furthermore, the validation of docking results through MD has become a standard practice in computational drug discovery, bridging the gap between static structural predictions and dynamic biological behavior.

Molecular Docking: Methods and Benchmarking

Docking Methodologies and Applications

Molecular docking encompasses a spectrum of algorithms designed to predict how a small molecule or peptide binds to a protein target. These methods vary in their treatment of flexibility, search algorithms, and scoring functions. Protein-ligand docking tools like AutoDock Vina specialize in predicting small molecule binding and were used in a study identifying 2-hydroxynaringenin as a potential phytochemical lead against triple-negative breast cancer by targeting the Androgen Receptor [24]. Protein-peptide docking methods address the challenge of peptide flexibility, with specialized tools like pepATTRACT designed to handle longer, more flexible peptides [13]. Protein-protein docking approaches such as ZDOCK and FRODOCK focus on larger protein-protein interfaces, which was applied in the AlphaRED pipeline combining AlphaFold with replica exchange docking for improved protein complex prediction [37].

Recent advances have integrated machine learning with traditional docking. The AlphaRED pipeline demonstrates how deep learning-based structure prediction from AlphaFold can be combined with physics-based docking to address challenging targets, particularly those involving conformational changes upon binding [37]. This integration has proven particularly valuable for difficult targets like antibody-antigen complexes, where AlphaRED achieved a 43% success rate compared to AlphaFold-multimer's 20% [37].

Experimental Protocol for Molecular Docking

A robust docking protocol consists of multiple standardized steps:

Protein Preparation: Retrieve the 3D structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and remove water molecules, cofactors, and original ligands. Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges using force fields like AMBER, and correct for missing residues or atoms. Energy minimization should be performed to relieve steric clashes [24].

Ligand Preparation: Obtain ligand structures from databases like PubChem and generate 3D coordinates. Optimize geometry using molecular mechanics methods and assign appropriate charges [20] [24].

Binding Site Definition: Either use known binding site coordinates from crystallographic data or predict potential binding pockets using cavity detection algorithms.

Docking Execution: Run the docking simulation using selected software. For virtual screening, tools like PyRx with AutoDock Vina can efficiently process compound libraries [24].

Pose Analysis and Scoring: Evaluate generated poses using the docking program's scoring function. Select top-ranked poses for further analysis based on binding energy and interaction patterns.

Benchmarking Docking Performance

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for validating docking methodologies. A comprehensive assessment of six docking methods (ZDOCK, FRODOCK, Hex, PatchDock, ATTRACT, and pepATTRACT) was conducted using 133 protein-peptide complexes, evaluating performance using CAPRI parameters like FNAT, I-RMSD, and L-RMSD [13]. The results demonstrated significant variation in performance across methods and highlighted the critical importance of proper benchmarking.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Docking Methods in Protein-Peptide Docking

| Docking Method | Type | Blind Docking (L-RMSD Å) | Re-docking (L-RMSD Å) | Key Algorithm Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRODOCK 2.0 | Rigid body | 12.46 | - | 3D grid-based potentials with spherical harmonics |

| ZDOCK 3.0.2 | Rigid body | - | 2.88 | FFT-based with shape complementarity, desolvation & electrostatics |

| AutoDock Vina | Flexible | - | 2.09* | Hybrid global/local search algorithm |

| ATTRACT | Flexible | - | - | Randomized search with Lennard-Jones & electrostatic potential |

| pepATTRACT | Flexible | - | - | Coarse-grained global search with simultaneous peptide modeling |

| Hex 8.0.0 | Rigid body | - | - | Spherical Polar Fourier correlations |