Field-Based vs. Similarity-Based 3D-QSAR: A Comprehensive Guide for Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a thorough comparative analysis of two foundational 3D-QSAR methodologies: field-based and similarity-based approaches.

Field-Based vs. Similarity-Based 3D-QSAR: A Comprehensive Guide for Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a thorough comparative analysis of two foundational 3D-QSAR methodologies: field-based and similarity-based approaches. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the theoretical underpinnings of each method, from classic Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) to advanced Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) and alignment-free techniques. The scope extends to practical applications in lead optimization and scaffold hopping, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and delivers a rigorous validation framework for model selection. By synthesizing methodological insights with current advancements, including open-source tools and machine learning integration, this review serves as a critical resource for the effective application of 3D-QSAR in rational drug design.

Core Principles: Understanding the Theoretical Basis of 3D-QSAR Approaches

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict the biological activity of compounds based on their chemical structures. Among these methodologies, three-dimensional QSAR (3D-QSAR) techniques have emerged as particularly powerful tools because they account for the spatial arrangement of molecules, thereby directly modeling the steric and electronic features crucial for biological recognition. This guide focuses on a specific subclass of these methods: field-based 3D-QSAR approaches, with the Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) paradigm as its central tenet. Unlike simpler 2D methods that utilize molecular graph descriptors, field-based techniques characterize molecules based on their non-covalent interaction potentials surrounding their three-dimensional structures [1]. The core premise is that a molecule's interaction with a biological target is mediated by its molecular interaction fields—regions in space where a probe would experience favorable or unfavorable steric, electrostatic, or other physicochemical interactions [1]. This stands in contrast to similarity-based 3D-QSAR methods, which often focus on aligning molecules and comparing their shapes or pharmacophoric features directly. Understanding this distinction is critical for selecting the appropriate tool for a given drug discovery problem.

Core Principles: Molecular Interaction Fields and the CoMFA Framework

The Concept of Molecular Interaction Fields

Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs) form the theoretical foundation of all field-based 3D-QSAR methods. An MIF describes how the interaction energy between a target molecule and a specific chemical probe varies throughout the surrounding three-dimensional space [1]. Regions of large negative interaction energy indicate areas where the probe is favorably attracted to the molecule, often corresponding to potential binding sites on a biological target. Conversely, regions of large positive energy indicate unfavorable, repulsive interactions. In practical terms, these fields are calculated by placing the molecule of interest within a three-dimensional grid and computing interaction energies at each grid point using a chosen probe atom or functional group [1]. The most fundamental probes include a positive ion (such as H+) for mapping the electrostatic potential, and a steric probe (like a methane molecule) for mapping the van der Waals surfaces. The resulting data matrix, which encodes the spatial and energetic properties of the molecule, serves as the input variables for subsequent statistical analysis to correlate with biological activity.

The CoMFA Paradigm

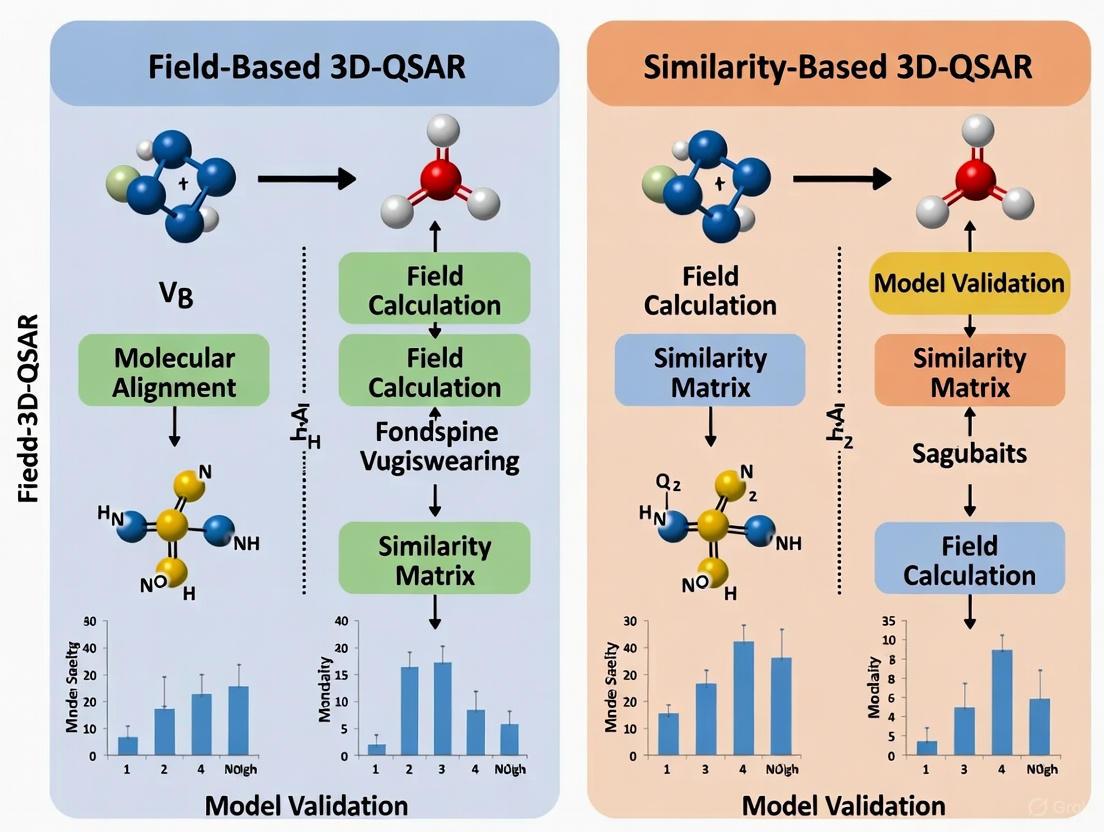

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), introduced in 1988, was the first and remains the most iconic field-based 3D-QSAR method [2]. Its operational workflow can be broken down into several key stages, as illustrated in the diagram below.

Critical Implementation Steps:

- Molecular Alignment: A set of molecules with known biological activities is aligned in 3D space according to a postulated pharmacophore or a common scaffold. The accuracy of this alignment is arguably the most critical step, as it ensures that the computed fields correspond meaningfully across the dataset [2].

- Grid Generation and Field Calculation: The aligned molecules are placed within a regularly spaced 3D grid. At each grid point, the steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies between a probe atom and each molecule are calculated [3].

- Statistical Correlation via PLS: The vast number of grid-point variables (descriptors) is correlated with the biological activity data using Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression. PLS is adept at handling datasets where the number of variables far exceeds the number of observations and where variables are highly collinear [4] [5].

- Visualization as Contour Maps: The results are interpreted visually through 3D contour maps. These maps highlight regions in space where specific changes in steric or electrostatic properties are predicted to increase or decrease biological activity, providing an intuitive guide for molecular design [3].

Comparative Analysis: Field-Based vs. Similarity-Based 3D-QSAR

While both are 3D-QSAR techniques, field-based and similarity-based approaches differ fundamentally in their underlying principles and descriptors. The table below provides a systematic comparison.

Table 1: Comparison of Field-Based and Similarity-Based 3D-QSAR Approaches

| Feature | Field-Based (CoMFA Paradigm) | Similarity-Based (e.g., LISA, FBSS) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Descriptor | Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs) - interaction energies with probes [1]. | Global or local molecular similarity indices, often based on shape or pharmacophore overlap [4] [2]. |

| Molecular Representation | Grid-based potential fields surrounding the molecule. | Overlaid structures and their computed similarity to a reference. |

| Descriptor Types | Primarily steric and electrostatic; extended in CoMSIA to hydrophobic and H-bond donor/acceptor fields [3]. | Similarity indices that may segregate regions into "favored similar" and "disfavored similar" potentials [4]. |

| Underlying Calculation | Force-field based (e.g., Coulombic, Lennard-Jones) or Gaussian functions for smoother fields (CoMSIA) [3]. | Similarity metrics (e.g., Carbo index, Petke's formula) computed across molecular alignments [4] [2]. |

| Primary Output | 3D contour maps showing regions where specific properties enhance/diminish activity. | A view of molecular sites permitting favorable changes, often with insight into binding mechanisms [4]. |

| Key Strength | Direct, physically intuitive interpretation of chemical space and interaction requirements. | Can suggest non-obvious alignments and may be less sensitive to alignment artifacts in some cases [2]. |

A key advancement within the field-based paradigm is Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA). Developed by Klebe et al., CoMSIA addresses several CoMFA limitations by using a Gaussian function to calculate similarity indices, thereby avoiding the abrupt energy cutoffs of CoMFA and resulting in models that are less sensitive to molecular alignment and grid parameters [3]. Furthermore, CoMSIA typically incorporates a broader set of physicochemical properties, including hydrophobic and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor fields, providing a more holistic view of the interaction landscape [3].

Performance Evaluation: Experimental Data and Comparative Studies

Empirical comparisons are essential for understanding the relative strengths and practical performance of these methodologies.

Case Study: Histamine H3 Receptor Antagonists

A seminal study compared 2D and 3D-QSAR methods for predicting the binding affinities of 58 arylbenzofuran histamine H3 receptor antagonists [5] [6]. The performance was evaluated using statistical metrics like the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) and the Standard Deviation of Error of Prediction (SDEP) from cross-validation.

Table 2: Predictive Performance on H3 Receptor Antagonists [5] [6]

| Method | Type | MAPE | SDEP | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | 2D | 2.9 - 3.6 | 0.31 - 0.36 | Performance was statistically comparable to ANN and superior to the 3D-HASL method. |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | 2D | 2.9 - 3.6 | 0.31 - 0.36 | Equally effective as MLR for this dataset, despite its higher sophistication. |

| HASL (Hypothetical Active Site Lattice) | 3D (Similarity-based) | Not Superior to 2D | Not Superior to 2D | Results were not as good as those obtained by the 2D methods. |

| CoMFA / CoMSIA | 3D (Field-based) | Not reported in this study | Not reported in this study | Commonly provides interpretable 3D contour maps, a key advantage over 2D models. |

This study underscores a critical point: simpler 2D methods can sometimes achieve predictive accuracy on par with or even exceeding that of more complex 3D methods, particularly when the dataset is congeneric. The primary advantage of field-based 3D methods like CoMFA and CoMSIA, therefore, lies not necessarily in superior predictive power for all systems, but in their rich graphical interpretability, which provides direct, visual guidance for molecular design.

Case Study: Sweetness Intensity of Chalcones

A 2025 study on the sweetness intensity of plant-derived chalcones effectively demonstrates the modern application of field-based 3D-QSAR. Researchers used both CoMFA and CoMSIA to decode the structure-sweetness relationship for 25 chalcones [7]. The resulting models were highly informative, revealing that:

- Introducing a negatively charged group at the C2 site of ring A would increase sweetness.

- A positively charged group at the C4 site and a small-volume group with a positive charge at the C6 site were also favorable [7].

The CoMSIA model, in particular, yielded a high cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) of 0.626, confirming its strong predictive capability. The findings were further validated by molecular docking, illustrating how field-based 3D-QSAR can generate testable, quantitative hypotheses for property optimization even outside traditional pharmaceutical targets [7].

Practical Implementation: Protocols and Reagents

Generic Workflow for a CoMFA/CoMSIA Study

The following protocol outlines the standard steps for conducting a field-based 3D-QSAR analysis.

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for a Field-Based 3D-QSAR Analysis

- Dataset Curation: Compile a series of molecules (typically 20-100) with consistent and quantitatively measured biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki).

- Molecular Modeling and Conformational Analysis: Generate reasonable 3D structures for all compounds. For flexible molecules, identify the putative bioactive conformation.

- Molecular Alignment: Superimpose all molecules according to a common scaffold or a hypothesized pharmacophore. This is a critical step that can be done manually or using automated tools like FBSS (Field-Based Similarity Searching) [2].

- Descriptor Calculation (Field Generation):

- Place the aligned molecule set into a 3D grid.

- For CoMFA: Calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) energies at each grid point using a sp³ carbon and a +1 charge as probes, respectively.

- For CoMSIA: Calculate similarity indices for steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor fields using a Gaussian function [3].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Use PLS regression to build a model correlating the field descriptors with the biological activity.

- Validate the model using techniques like Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation to obtain a q² value and an external test set to obtain a predictive r² (r²pred) [3].

- Model Interpretation: Analyze the resulting 3D contour maps to identify regions where specific molecular modifications are predicted to enhance activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Resources for Field-Based 3D-QSAR Research

| Resource / Reagent | Function in 3D-QSAR | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Suite | Provides the environment for structure building, energy minimization, conformational analysis, and alignment. | Commercial: Schrödinger Suite, MOE. Open-source: Open3DALIGN. |

| 3D-QSAR Software | Performs the core tasks of grid generation, field calculation, PLS analysis, and visualization of contour maps. | Commercial: Built into Schrödinger, MOE. Open-source: Py-CoMSIA (a Python implementation that replicates CoMSIA functionality) [3]. |

| Validated Dataset | Serves as a benchmark for testing new models and methodologies. | The classic steroid benchmark dataset is frequently used for validation [3]. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) Algorithm | The statistical engine that correlates the high-dimensional field data with biological activity. | Implemented in all major 3D-QSAR software packages. |

Field-based 3D-QSAR, pioneered by the CoMFA paradigm, provides an indispensable framework for understanding the intricate relationship between a molecule's three-dimensional structure and its biological function. While simpler 2D-QSAR or other similarity-based 3D methods may sometimes achieve comparable predictive accuracy for specific datasets, the defining value of CoMFA and its advanced successor CoMSIA lies in their powerful, visual interpretability. The 3D contour maps generated by these methods transform abstract statistical models into concrete, spatially-resolved design guides, enabling medicinal chemists to make rational decisions about which molecular features to modify and where. The ongoing development of open-source tools, such as Py-CoMSIA, promises to broaden access to these powerful techniques and foster further innovation in the field [3]. As demonstrated by applications ranging from kinase inhibitors to sweetener design, field-based 3D-QSAR remains a vital technology for molecular design and optimization across scientific disciplines.

The concept of molecular similarity represents a foundational principle in computer-aided drug design, underpinning the assumption that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [8]. This molecular similarity principle has driven the development of sophisticated quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) methodologies that translate molecular features into predictive models for biological activity [8]. Among these, three-dimensional QSAR (3D-QSAR) techniques have emerged as powerful tools that consider the spatial orientation of molecules, providing critical insights into the interaction between a ligand and its biological target.

The evolution of 3D-QSAR has progressed through two predominant conceptual frameworks: field-based approaches and similarity-based approaches. Field-based methods, exemplified by Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), characterize molecules by calculating their steric and electrostatic interaction potentials with probe atoms in a 3D grid [9] [10]. While revolutionary, these methods demonstrated sensitivity to molecular alignment and functional parametrization, prompting the development of more advanced similarity-based techniques [9]. Similarity-based approaches, including Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) and emerging Local Molecular Similarity (LISA) methods, employ Gaussian-type distance-dependent functions to evaluate molecular resemblance across multiple physicochemical properties, offering superior handling of molecular alignment and a more comprehensive description of interaction potentials [9] [11].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their theoretical foundations, practical implementation, predictive performance, and applications in contemporary drug discovery pipelines.

Theoretical Foundations: From Molecular Fields to Similarity Indices

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA): The Field-Based Paradigm

CoMFA operates on the fundamental premise that a molecule's biological activity correlates with its non-covalent interaction fields sampled in three-dimensional space [9] [10]. The methodology involves several systematic steps: first, a set of congeneric molecules is selected and their 3D structures are energy-minimized; second, molecules are aligned according to a hypothesized pharmacophore or bioactive conformation; third, a 3D grid is constructed around the aligned molecules; fourth, steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies between each molecule and a probe atom are calculated at every grid point; finally, Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression correlates these field values with biological activity to generate a predictive model [9]. The results are typically visualized as 3D contour maps indicating regions where specific molecular properties would enhance or diminish biological activity [10].

Despite its widespread adoption and success, CoMFA suffers from several theoretical limitations. The method is highly sensitive to molecular orientation and alignment within the grid, and the Lennard-Jones potential used for steric fields can produce singularities at atomic positions, requiring arbitrary cutoff values [9] [10]. Additionally, the original CoMFA formalism incorporates only steric and electrostatic fields, potentially overlooking other critical interactions such as hydrophobicity and hydrogen bonding that significantly influence ligand-receptor recognition [9].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA): The Similarity-Based Advancement

CoMSIA was developed to address several limitations inherent in CoMFA. Rather than calculating interaction energies, CoMSIA evaluates similarity indices using a common probe atom at regularly spaced grid points around pre-aligned molecules [9]. The key theoretical advancement lies in the use of a Gaussian-type function for field calculation, which eliminates singularities and provides a "softer" potential that does not require arbitrary cutoff limits [9] [10].

The CoMSIA methodology extends beyond the steric and electrostatic fields of CoMFA to incorporate up to five physicochemical properties: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor and acceptor fields [9]. This comprehensive description of molecular properties allows for a more nuanced understanding of ligand-receptor interactions. The similarity indices (AF) for each property are calculated using the equation:

[ AF(q) = -\sum{i=1}^{n} w{probe,k} w{ik} e^{-\alpha r_{iq}^{2}} ]

where ( w{ik} ) represents the actual value of the physicochemical property k of atom i, ( w{probe,k} ) is the probe value, and ( r_{iq} ) is the mutual distance between the probe atom at grid point q and atom i of the molecule [9]. The exponent ( \alpha ) defines the steepness of the Gaussian function. The resulting contour maps from CoMSIA analyses indicate regions within the molecular region that favor or disfavor specific physicochemical properties, providing more intuitive guidance for molecular optimization [9].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between CoMFA and CoMSIA Approaches

| Feature | CoMFA | CoMSIA |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Interaction energy fields | Similarity indices |

| Field Calculation | Lennard-Jones & Coulomb potentials | Gaussian-type distance function |

| Fields Included | Steric, Electrostatic | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-bond Donor, H-bond Acceptor |

| Alignment Sensitivity | High | Moderate |

| Cutoff Requirements | Required to avoid singularities | Not required |

| Contour Map Interpretation | Regions where fields interact favorably/unfavorably | Regions within ligand space favoring specific properties |

Local Molecular Similarity (LISA) and Evolutionary Methods

Building upon the similarity concept, recent approaches have further refined molecular similarity assessment. Local Molecular Similarity methods focus on specific molecular regions or pharmacophoric features rather than global similarity, potentially offering enhanced selectivity in virtual screening [11]. Evolutionary chemical binding similarity approaches, such as the target-specific ensemble evolutionary chemical binding similarity (TS-ensECBS) model, incorporate machine learning to encode evolutionarily conserved key molecular features required for target-binding into chemical similarity scores [11]. These methods measure the probability that chemical compounds bind to identical or related targets, representing a shift from purely structural similarity to functional similarity based on binding site characteristics [11].

Methodological Comparison: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard CoMSIA Protocol

The implementation of a CoMSIA study follows a well-defined workflow that shares initial steps with CoMFA but diverges in field calculation and analysis [9]:

Dataset Preparation: A series of molecules with known biological activities is compiled. For robust model development, the dataset should be divided into training (typically 80-85%) and test sets (15-20%) [12].

Molecular Modeling and Conformational Analysis: 3D molecular structures are constructed and energy-minimized using molecular mechanics (e.g., MM2) or quantum chemical methods (e.g., AM1). The most likely bioactive conformation is identified for each molecule [9] [6].

Molecular Alignment: This critical step involves superimposing molecules based on a common scaffold, pharmacophoric features, or receptor-active site. The most active compound is often used as a template [9]. For example, in a study of 6-aryl-5-cyano-pyrimidine derivatives as LSD1 inhibitors, molecules were aligned based on their common pyrimidine scaffold [13].

Field Calculation: A 3D grid with typically 2.0 Å spacing is created around the aligned molecules. Similarity indices are calculated for each physicochemical property using a probe atom with specific characteristics: radius 1.0 Å, charge +1, hydrophobicity +1, and hydrogen bond donor and acceptor properties +1 [9].

Statistical Analysis and Model Validation: Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression correlates the similarity indices with biological activity. Model quality is assessed using cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²), conventional correlation coefficient (r²), standard error of estimate (SEE), and F-value [12] [9]. For instance, a CoMSIA model for 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives as MAO-B inhibitors demonstrated strong predictive power with q² = 0.569 and r² = 0.915 [12].

CoMSIA Methodology Workflow: This diagram illustrates the standard workflow for CoMSIA model development, highlighting the sequential steps from dataset preparation to predictive application.

Machine Learning-Enhanced CoMSIA Protocols

Recent advances have integrated machine learning (ML) techniques with CoMSIA to address limitations of traditional PLS regression, particularly when handling the high dimensionality of CoMSIA descriptors [14] [15]. A novel ML-enhanced protocol demonstrated superior performance for identifying lipid antioxidant peptides:

Feature Selection: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and SelectFromModel techniques were applied to identify the most relevant CoMSIA descriptors from thousands of initially generated indices [14] [15].

Algorithm Selection and Hyperparameter Tuning: Twenty-four different regression estimators were evaluated, with tree-based models like Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) showing particular promise. Hyperparameter tuning through GridSearchCV optimized parameters such as learningrate, maxdepth, and n_estimators [14] [15].

Model Validation: The optimized GB-RFE with GBR model (learningrate = 0.01, maxdepth = 2, n_estimators = 500, subsample = 0.5) demonstrated superior performance with RCV² of 0.690, R²test of 0.759, and R² of 0.872 compared to the traditional PLS model (RCV² of 0.653, R²test of 0.575, and R² of 0.755) [14] [15].

This integrated approach effectively mitigated overfitting issues commonly encountered with traditional CoMSIA models and enhanced predictive accuracy for novel compound design [14].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis of Predictive Accuracy

Direct comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA methodologies across various therapeutic targets reveals distinct performance patterns that inform method selection for specific applications.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA Across Various Targets

| Therapeutic Target | Compound Series | Best CoMFA Model (q²/r²) | Best CoMSIA Model (q²/r²) | Key Interaction Fields | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 Protease | HOE/BAY-793 analogs | 0.562/0.985 | 0.662/0.989 | Steric, Electrostatic, H-bond Donor | [10] |

| LSD1 Inhibitors | 6-Aryl-5-cyano-pyrimidines | 0.802/0.979 | 0.799/0.982 | Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-bond Donor | [13] |

| MAO-B Inhibitors | 6-Hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamides | N/R | 0.569/0.915 | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic | [12] |

| Lipid Antioxidant Peptides | Tryptophyllin L fragments | N/R | 0.653/0.755 (Traditional PLS) | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic | [14] |

| Lipid Antioxidant Peptides | Tryptophyllin L fragments | N/R | 0.690/0.872 (ML-Enhanced) | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic | [14] |

Cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) and conventional correlation coefficient (r²) values are reported where available. *RCV² and R² values reported for the lipid antioxidant peptide study [14]. N/R = Not Reported.

The quantitative comparisons reveal several important trends. CoMSIA frequently demonstrates comparable or superior predictive performance relative to CoMFA, with the HIV-1 protease inhibitor study showing a notably higher q² value for CoMSIA (0.662) compared to CoMFA (0.562) [10]. The additional physicochemical properties included in CoMSIA (hydrophobicity, hydrogen bonding) often contribute significantly to model quality, as observed in the LSD1 inhibitor study where electrostatic, hydrophobic and H-bond donor fields played crucial roles [13]. Most significantly, the integration of machine learning feature selection and algorithm optimization with CoMSIA descriptors substantially enhanced model predictivity and mitigated overfitting, demonstrating the potential of hybrid approaches [14] [15].

Research Applications and Case Studies

Lipid Antioxidant Peptide Discovery

A comprehensive application of ML-enhanced CoMSIA was demonstrated in the identification of lipid antioxidant peptides from Tryptophyllin L tripeptide fragments [14] [15]. The optimized model identified key molecular features contributing to ferric thiocyanate (FTC) antioxidant activity and screened potential antioxidant tripeptides. Subsequent synthesis and experimental validation confirmed promising activity levels for three peptides: F-P-5Htp (FTC = 4.2 ± 0.12), F-P-W (FTC = 4.4 ± 0.11), and P-5Htp-L (FTC = 1.72 ± 0.15) [14] [15]. This case study highlights the successful translation of computational predictions to experimentally verified bioactive compounds.

Kinase Inhibitor Identification Using Similarity-Based Approaches

The evolutionary chemical binding similarity approach (TS-ensECBS), which shares conceptual foundations with local molecular similarity methods, demonstrated remarkable efficacy in virtual screening for kinase targets [11]. In a blinded validation study, the method identified novel inhibitors for MEK1 and EPHB4 kinases with a success rate of 46.2% (6 out of 13 compounds) for MEK1 and 16.7% (2 out of 12 compounds) for EPHB4 confirmed through in vitro binding assays [11]. Notably, many identified molecules exhibited low structural similarity to known inhibitors, revealing novel scaffolds that would likely have been missed by traditional similarity methods [11].

CNS-Active Agent Optimization

Molecular field-based similarity approaches have also proven valuable in central nervous system drug discovery. A field point analysis of quinoline-based agents with CNS activity assessed their 3D similarity to standard atypical antipsychotics [8]. The compounds demonstrated relatively lower 3D similarity to clozapine but higher similarity to extended chain compounds like ketanserin, ziprasidone, and risperidone [8]. These computational findings aligned with previously reported physicochemical similarity measures and biological activity profiles, supporting the utility of field-based similarity assessments in understanding structure-activity relationships for complex molecular targets [8].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Similarity-Based 3D-QSAR

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Key Function | Application in 3D-QSAR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | SYBYL/Tripos Force Field, ChemBio3D, Hyperchem | 3D structure construction, energy minimization, conformational analysis | Molecular preparation and optimization prior to alignment | [8] [6] |

| Field Calculation | FieldAlign, Open3DALIGN, in-house Python scripts | Molecular alignment, similarity field calculation, grid generation | Core CoMSIA field computation and descriptor generation | [8] [15] |

| Statistical Analysis | Partial Least Squares (PLS), Scikit-learn (Python) | Regression modeling, feature selection, hyperparameter tuning | Correlation of similarity indices with biological activity | [14] [9] |

| Machine Learning | Gradient Boosting Regression, Random Forest, SVM | Nonlinear pattern recognition, descriptor optimization | Enhanced prediction accuracy and feature selection | [14] [11] |

| Validation Tools | Cross-validation routines, bootstrapping algorithms | Model validation, robustness assessment | Statistical verification of model predictivity | [14] [12] |

| Visualization | PyMOL, VMD, SYBYL contour maps | 3D visualization of contour maps, molecular interactions | Interpretation of favorable/unfavorable molecular regions | [13] [10] |

The evolution from field-based to similarity-based 3D-QSAR approaches represents significant methodological advancement in computational drug design. CoMSIA's Gaussian potential functions, diverse physicochemical fields, and more intuitive contour maps address key limitations of the CoMFA approach while maintaining strong predictive performance. The integration of machine learning for feature selection and model optimization further enhances the utility of similarity-based methods, as demonstrated by the superior performance of ML-enhanced CoMSIA in identifying antioxidant peptides [14] [15].

Future developments in similarity-based 3D-QSAR will likely focus on several promising directions. Dynamic 3D-QSAR approaches that incorporate molecular flexibility and explicit solvation effects may provide more physiologically relevant models [12]. The integration of deep learning architectures for automatic feature extraction from molecular fields could further reduce reliance on expert-driven alignment rules [11]. Additionally, hybrid methods combining ligand-based similarity approaches with structural information from target proteins offer opportunities for enhanced predictive accuracy across diverse chemical classes [11].

As these methodologies continue to evolve, similarity-based 3D-QSAR approaches will remain indispensable tools in the molecular design toolkit, providing critical insights into structure-activity relationships and accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents.

The field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR) has fundamentally transformed drug discovery by providing a systematic framework to correlate chemical structure with biological activity. The journey began with classical Hansch analysis in the 1960s, which established the fundamental principle that biological activity correlates with physicochemical properties of chemical substances [16] [17]. This paradigm established that similar compounds typically exhibit similar biological properties, laying the groundwork for computational approaches in medicinal chemistry [16]. For decades, QSAR has served as an indispensable predictive tool in the design of pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals, significantly reducing the trial-and-error factor involved in drug development by facilitating the selection of the most promising candidates for synthesis [17].

The evolution from these early one-dimensional approaches to sophisticated three-dimensional (3D) methods represents one of the most significant advancements in computer-aided drug design. This transition was driven by the recognition that classical QSAR approaches had limited utility for designing new molecules due to their inability to account for the three-dimensional structure of molecules and their interaction with biological targets [17]. This comprehensive review traces this historical progression, comparing the methodological approaches, applications, and predictive capabilities of classical and modern 3D-QSAR techniques within the broader context of field-based versus similarity-based approaches.

The Classical Era: Hansch Analysis and 2D-QSAR

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Hansch analysis, pioneered by Corwin Hansch in the 1960s, operates on the principle that biological activity can be correlated with physicochemical properties using linear free-energy relationships [16] [17]. This approach utilizes global molecular descriptors that reduce complex molecular structures to numerical values representing key properties:

- Lipophilicity (logP): Representing the partition coefficient between octanol and water phases

- Electronic properties: Including Hammett constants and dipole moments

- Steric parameters: Such as Taft's steric factor and molar refractivity [16] [17]

In classical QSAR, molecules are described using summary descriptors that do not depend on the molecule's three-dimensional orientation. These one-dimensional or two-dimensional descriptors remain invariant when the molecule is rotated or translated in space, treating molecular structure as essentially flat or feature-based rather than three-dimensional [18]. The developed model typically includes a set of selected variables (descriptors) that are statistically significant and allow insights into the mode of studied interaction, though this approach does not adequately describe ligand-receptor interactions that depend on spatial arrangement [16].

Mathematical Formulation and Application

The classical Hansch approach employs Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) to construct mathematical relationships of the general form:

Activity = f(D₁, D₂, D₃...)

Where D₁, D₂, D₃ represent molecular descriptors encoding specific structural features, including polarizability, electronic properties, and steric parameters [16] [19]. These descriptors encode certain structural features that influence biological activity, with the model providing a statistical correlation between these features and the measured biological endpoint [16].

The methodology follows a structured workflow:

- Calculation of physicochemical descriptors for a series of compounds with known activity

- Selection of the most relevant descriptors using statistical methods

- Development of a linear mathematical model correlating descriptors with biological activity

- Validation using internal and external validation techniques [19]

Table 1: Key Descriptors in Classical Hansch Analysis

| Descriptor Category | Specific Examples | Structural Property Represented |

|---|---|---|

| Lipophilic | logP, π (Hansch constant) | Hydrophobicity, membrane permeability |

| Electronic | σ (Hammett constant), dipole moment, HOMO/LUMO energies | Electron donating/withdrawing effects, molecular reactivity |

| Steric | Molar refractivity, Taft's steric constant, surface area | Molecular size, shape, and bulkiness |

| Structural | Indicator variables, atom counts | Presence/absence of specific functional groups |

The 3D Paradigm Shift: From Flat to Spatial

The Advent of 3D-QSAR

The limitations of classical approaches prompted the development of three-dimensional QSAR methods that explicitly account for molecular shape and interaction fields. The first application of 3D-QSAR technique was proposed in 1988 by Cramer et al. with their program Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) [16] [17]. This revolutionary approach assumed that differences in biological activity correspond to changes in shapes and strengths of non-covalent interaction fields surrounding the molecules [16] [17].

Unlike classical QSAR that treats molecules as collections of global properties, 3D-QSAR considers molecules as three-dimensional objects with specific shapes and interaction potentials. These methods derive descriptors directly from the spatial structure of the molecule, typically quantifying steric fields (representing regions where molecular bulk may clash or accommodate other structures) and electrostatic fields (mapping areas of positive or negative potential) [18]. This fundamental shift from "what groups are present" to "where and how these groups are arranged in space" represented a quantum leap in molecular modeling capabilities.

Key Methodological Differences

The transition from 2D to 3D QSAR introduced several critical methodological distinctions:

- Descriptor Computation: 3D-QSAR involves aligning each molecule within a coordinate grid and computing field values at specific points surrounding it, leading to a much higher dimensional descriptor space than in classical QSAR [18]

- Conformational Dependence: Unlike 2D descriptors that are invariant to conformation, 3D descriptors depend on the molecular conformation and orientation in space

- Alignment Sensitivity: 3D-QSAR methods, particularly CoMFA, are highly sensitive to molecular alignment, requiring careful superposition based on putative bioactive conformations [18]

Table 2: Fundamental Differences Between Classical and 3D QSAR Approaches

| Aspect | Classical (Hansch) QSAR | 3D-QSAR Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Representation | 1D/2D descriptors (logP, molar refractivity) | 3D interaction fields (steric, electrostatic) |

| Descriptor Dimensionality | Low (typically <10 parameters) | High (hundreds to thousands of grid points) |

| Conformational Dependence | None | Critical (requires bioactive conformation) |

| Alignment Requirement | Not applicable | Essential for field-based methods |

| Statistical Methods | MLR, PCA | PLS, G/PLS, ANN |

| Interpretation | Numerical coefficients | 3D contour maps |

| Handling of Structural Diversity | Limited to congeneric series | Accommodates greater diversity |

Modern 3D-QSAR Methodologies: Field-Based vs. Similarity-Based Approaches

Field-Based Methods: CoMFA and Beyond

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) stands as the pioneering field-based 3D-QSAR approach. The methodology involves placing aligned molecules within a 3D lattice and using a probe atom to calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies at each grid point [16] [18]. The collection of these field values forms a fingerprint-like descriptor for the molecule's 3D shape and electrostatic profile, which is then correlated with biological activity using Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression [18].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extends CoMFA by using Gaussian-type functions to evaluate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields [18]. This approach smooths out abrupt field changes near molecular surfaces and enhances interpretability, especially across structurally diverse compounds. While CoMFA is highly sensitive to alignment quality, CoMSIA offers more tolerance to minor misalignments, thereby expanding its applicability [18].

A recent study on MAO-B inhibitors demonstrated the power of CoMSIA, where the developed model exhibited excellent predictive ability with a q² value of 0.569 and r² value of 0.915, successfully guiding the design of novel neuroprotective agents [20].

Similarity-Based Approaches and Local Methods

As alternatives to field-based approaches, similarity-based methods have emerged that focus on molecular similarity indices rather than interaction fields. The Local Indices for Similarity Analysis (LISA) approach breaks global molecular similarity into local similarity at each grid point surrounding molecules, using these as QSAR descriptors [4]. This method segregates regions into "equivalent," "favored similar," and "disfavored similar" potentials with respect to a reference molecule, providing insights into binding mechanisms and allowing fine-tuning of molecules at the local level to improve activity [4].

Similarity-based approaches offer distinct advantages in their straightforward graphical interpretation and ability to handle structurally diverse datasets without stringent alignment requirements. The outcome of these models corroborates well with literature data and provides medicinal chemists with intuitive guidance for molecular optimization [4].

Table 3: Comparison of Major 3D-QSAR Methodologies

| Method | Descriptor Basis | Fields/Indices Calculated | Alignment Sensitivity | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | Steric/electrostatic interaction energies | Lennard-Jones, Coulomb | High | Established method, intuitive fields |

| CoMSIA | Similarity indices using Gaussian functions | Steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, H-bond donor/acceptor | Moderate | Broader field types, smoother sampling |

| LISA | Local similarity indices | Shape, electrostatic similarity | Moderate | Direct similarity comparison, local optimization guidance |

| HASL | Composite lattice from 3D grids | Multipoint pharmacophore patterns | Low to moderate | Handles conformational flexibility |

| ML-Based 3D-QSAR | Shape, color, electrostatic featurizations | ROCS shape, EON electrostatics | Variable (alignment-free options) | Error estimation, confidence predictions [21] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Workflows

Building a Robust 3D-QSAR Model

The construction of a reliable 3D-QSAR model follows a systematic workflow with critical steps at each phase:

Data Collection and Preparation: Assembling a dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (IC₅₀, EC₅₀, Kᵢ) measured under uniform conditions is paramount. The integrity of this dataset directly impacts model quality, requiring structurally related yet sufficiently diverse molecules to capture meaningful structure-activity relationships [18].

Molecular Modeling and Conformation Optimization: 2D structures are converted to 3D coordinates using cheminformatics tools like RDKit or Sybyl, followed by geometry optimization using molecular mechanics (UFF) or quantum mechanical methods to ensure realistic, low-energy conformations [18]. For the classic nano-QSAR approach, optimal geometries of investigated fullerene derivatives were obtained applying Density Functional Theory (DFT) with the hybrid meta exchange-correlation functional M06-2X and the 6-31G(d,p) basis set [16].

Molecular Alignment: This critical step involves superimposing all molecules in a shared 3D reference frame reflecting putative bioactive conformations. Approaches include:

- Bemis-Murcko Scaffold: Removing side chains and retaining ring systems and linkers

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS): Identifying largest shared substructure

- Pharmacophore-based alignment: Using common chemical features [18]

Descriptor Calculation and Variable Selection: For CoMFA, a lattice of grid points surrounds the molecules where steric and electrostatic interaction energies are calculated using probe atoms [18]. With modern machine learning approaches, featurization using shape (from ROCS) and electrostatics (from EON) provides comprehensive 3D molecular representations [21]. Genetic algorithms are often employed for variable selection to identify the most relevant descriptors [16] [19].

Model Building and Validation: PLS regression correlates field values with biological activities. Robust validation includes:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR Research

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Solutions | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | Sybyl-X, Schrodinger Suite, HyperChem | 3D structure generation, optimization, and visualization |

| Quantum Chemistry | Gaussian 09, GAMESS, ORCA | Quantum mechanical calculations, orbital energies, accurate geometry optimization |

| Cheminformatics | RDKit, OpenBabel, Dragon | Descriptor calculation, file format conversion, structural analysis |

| Alignment Tools | ROCS, Phase | Molecular superposition using shape or pharmacophore features |

| 3D-QSAR Specific | CoMFA, CoMSIA (in Sybyl), HASL | Field calculation, similarity analysis, model building |

| Statistical Analysis | QSARINS, MATLAB, R | MLR, PLS, genetic algorithm variable selection |

| Machine Learning | Python Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, Orion | Advanced pattern recognition, model building with error estimation [21] |

Comparative Performance and Applications

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Direct comparisons between classical and 3D-QSAR approaches reveal distinct performance characteristics. In a study comparing different 2D and 3D-QSAR methods for predicting histamine H3 receptor antagonist activity, 3D methods generally demonstrated superior predictive capability for structurally diverse compounds, while well-parameterized 2D models performed adequately for congeneric series [6].

A recent 3D-QSAR study on MAO-B inhibitors demonstrated impressive statistical results with a CoMSIA model exhibiting q² = 0.569, r² = 0.915, SEE = 0.109, and F value = 52.714 [20]. Similarly, modern machine learning-enhanced 3D-QSAR approaches show performance on-par with or better than published methods, with the additional advantage of providing prediction error estimates to help users identify the right compounds for the right reasons [21].

Application Case Studies

The evolution from Hansch analysis to 3D methods has expanded QSAR applications across multiple domains:

Drug Discovery: 3D-QSAR has become indispensable in lead optimization campaigns, successfully guiding the design of HIV-1 protease inhibitors [16], MAO-B inhibitors for neurodegenerative diseases [20], and NF-κB inhibitors for inflammatory conditions and cancer [19]

Toxicity Prediction: Nano-QSAR approaches have been developed to investigate nanoparticle toxicity and environmental health effects, with 3D methods providing insights into interaction mechanisms [16]

Materials Science: QSAR approaches have been applied to predict corrosion inhibition efficiency, with recent studies demonstrating that 3D descriptors combined with machine learning models like XGBoost achieve superior predictive performance (R² = 0.94-0.96 for training sets) [22]

Environmental Chemistry: Prediction of aquatic toxicity, pesticide effects, and environmental fate of chemicals [19]

Current Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of QSAR continues to evolve with emerging trends shaping its future development. Integration of machine learning with 3D-QSAR represents perhaps the most significant advancement, with models featurized using shape, color, and electrostatic properties demonstrating enhanced predictive capability [21]. These approaches leverage the full 3D similarity of molecules while providing confidence estimates for predictions.

Ultra-large virtual screening capabilities now enable researchers to screen billions of compounds, with 3D-QSAR models providing rapid prioritization of candidates for more computationally intensive methods like free energy calculations [23] [21]. The synergy between rapid 3D-QSAR screening and detailed molecular dynamics simulations creates a powerful multi-tiered approach to drug discovery [20].

Future developments will likely focus on dynamic 3D-QSAR approaches that account for protein flexibility and binding site adaptations, moving beyond the static ligand-receptor interaction paradigm. Additionally, the integration of deep learning architectures with 3D molecular representations promises to further enhance predictive accuracy while reducing dependence on precise molecular alignment [23].

The historical evolution from Hansch analysis to modern 3D-QSAR methods represents a remarkable journey of increasing molecular representation complexity and predictive capability. While classical QSAR approaches established the fundamental principle that biological activity correlates with molecular structure, their limitation to global descriptors restricted their utility for detailed molecular design.

The advent of 3D-QSAR methodologies addressed this limitation by explicitly incorporating spatial and electronic properties, enabling medicinal chemists to visualize and optimize molecular interactions with biological targets. The distinction between field-based approaches like CoMFA/CoMSIA and similarity-based methods like LISA provides researchers with complementary tools for addressing different challenges in molecular design.

As the field continues to evolve, the integration of machine learning with 3D structural information promises to further enhance predictive accuracy and practical utility. This ongoing innovation ensures that QSAR methodologies will remain indispensable tools in drug discovery and molecular design, building upon the foundation established by Hansch over half a century ago while embracing the computational power and theoretical advances of the modern era.

In the field of computer-aided drug design, Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) methods are pivotal for correlating the biological activity of compounds with their spatial characteristics. Two dominant paradigms have emerged: the interaction energy fields approach and the Gaussian similarity indices methodology. While both aim to predict and optimize compound activity, their underlying principles and operational frameworks differ significantly. Interaction energy fields, exemplified by methods like Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), directly compute physico-chemical potential energies around molecules [24]. In contrast, Gaussian similarity indices, central to techniques like Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), employ probabilistic functions to measure molecular resemblance [25] [26]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these strategies, detailing their performance, supported by experimental data and practical implementation protocols.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Principles

Core Conceptual Frameworks

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in how they represent and quantify molecular environments.

Interaction Energy Fields are rooted in classical molecular mechanics [24]. This approach posits that a biological receptor perceives a ligand not as atoms and bonds, but as a shape carrying complex forces, predominantly steric and electrostatic potentials. The method involves placing a target molecule within a 3D lattice and using a probe atom (e.g., an sp³ carbon with a +1 charge for electrostatic fields) to calculate the interaction energy at each grid point using potentials like Coulomb's law (electrostatic) and Lennard-Jones (steric) [24]. The resulting data represents a direct mapping of the Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs), which can be visualized as iso-potential surfaces to identify favorable and unfavorable interaction regions around the molecule.

Gaussian Similarity Indices, used in methods like CoMSIA, abandon the direct calculation of harsh potential energies [25]. Instead, they describe molecular properties using Gaussian-type functions for distance dependence [27] [26]. This approach calculates the similarity of molecules in a set to a common probe placed at grid points, using a Gaussian function to avoid singularities and extreme values inherent in classical potential functions. CoMSIA typically extends beyond steric and electrostatic fields to include hydrogen bond donor, hydrogen bond acceptor, and hydrophobic fields, providing a more nuanced description of interaction potential [25] [26].

Mathematical Underpinnings

The mathematical representation highlights their core differences:

- Interaction Energy Fields (CoMFA): The steric energy ( E{steric} ) is often described by a Lennard-Jones potential ( E = \frac{A}{r^{12}} - \frac{B}{r^6} ), and electrostatic energy ( E{electrostatic} ) by Coulomb's law ( E = \frac{q1 q2}{\epsilon r} ), where ( r ) is the distance from a grid point to an atom, and ( q ) is atomic charge [24].

- Gaussian Similarity Indices (CoMSIA): The similarity index ( AF ) for a property ( F ) at grid point ( q ) is calculated as ( AF(q) = -\sumi \omega{probe} \omega{ik} e^{-\alpha r{iq}^2} ), where ( \omega{ik} ) is the actual value of the property for atom ( i ), ( r{iq} ) is the distance between grid point ( q ) and atom ( i ), and ( \alpha ) is an attenuation factor [27] [26]. This Gaussian function ensures the similarity indices decay smoothly with distance.

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between the Two Approaches

| Feature | Interaction Energy Fields (e.g., CoMFA) | Gaussian Similarity Indices (e.g., CoMSIA) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Calculation of physico-chemical potential energies | Measurement of molecular similarity using Gaussian functions |

| Distance Dependence | Inverse power laws (e.g., (1/r), (1/r^{12})) | Exponential decay ((e^{-\alpha r^2})) |

| Handling of Singularities | Prone to extreme values near van der Waals surfaces | Avoided due to Gaussian function properties |

| Primary Descriptors | Steric and Electrostatic fields | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-bond Donor, H-bond Acceptor fields |

| Probe Usage | Single-atom probe to measure energy | Common probe to measure similarity indices |

| Visualization | Direct interpretation of potential energy contours | Interpretation of similarity and dissimilarity regions |

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Implementation

Standardized Workflow for 3D-QSAR Model Development

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for developing a 3D-QSAR model, highlighting steps where the two methodologies diverge.

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol for Interaction Energy Fields (CoMFA) [24] [25]:

- Molecular Alignment: Align training set molecules based on a presumed bioactive conformation, using a common scaffold or pharmacophore hypothesis.

- Grid Generation: Embed the aligned molecules in a 3D grid with a typical spacing of 1.0–2.0 Å, ensuring all molecules are contained.

- Interaction Energy Calculation:

- Steric Field: Use an sp³ carbon probe with a van der Waals radius of 1.52 Å and a typical energy cutoff of 30 kcal/mol. Calculate using a 6-12 Lennard-Jones potential.

- Electrostatic Field: Use a +1.0 charged sp³ carbon probe. Calculate using Coulomb's law with a distance-dependent dielectric constant (e.g., ε = 1r).

- Data Reduction and PLS Analysis: Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate the energy field values with biological activity. Apply cross-validation (e.g., leave-one-out) to determine the optimal number of components and avoid overfitting.

Protocol for Gaussian Similarity Indices (CoMSIA) [25] [26]:

- Molecular Alignment and Grid Generation: Perform identical to the CoMFA protocol.

- Similarity Indices Calculation: For each molecule, calculate similarity indices at all grid points for five property fields: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor.

- Use a Gaussian function with a default attenuation factor ( \alpha ) of 0.3.

- The hydrophobic field is derived from atom-based parameters (e.g., Crippen log P fragments). Hydrogen bond donor and acceptor fields use appropriate probe atoms.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform PLS regression on the similarity indices. The smoother nature of the CoMSIA fields often requires a different column filtering value than CoMFA.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Independent studies across different biological targets provide objective performance comparisons.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison from Literature Case Studies

| Study Context | Method | Statistical Metrics | Key Performance Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antitumor Diaryl-sulfonylureas (28 compounds) | CoMFA | q² = 0.653, r² = 0.955 | Superior statistical correlation, best model in study | [25] |

| CoMSIA | q² = 0.638, r² = 0.934 | Comparable, strong performance | [25] | |

| Lipid Antioxidant Peptides (FTC Dataset, 197 peptides) | CoMSIA (Traditional PLS) | R²CV = 0.653, R²test = 0.575 | Baseline performance with linear PLS | [26] |

| CoMSIA (ML-Enhanced, GBR) | R²CV = 0.690, R²test = 0.759 | Machine learning integration significantly boosted predictivity | [26] | |

| Quantum Mechanical MIFs (9 diverse datasets) | QM-Based MIFs | N/A | Average performance superior to force-field (FF) MIFs; performance equal or better in all datasets | [28] |

Qualitative Comparative Analysis

- Interpretability and Visualization: CoMFA contour maps directly indicate regions where increased steric bulk or positive/negative charge is favorable/unfavorable for activity [24]. CoMSIA maps, due to the Gaussian basis, are often considered less harsh and may more clearly define favorable regions for specific interactions like hydrogen bonding or hydrophobicity [25].

- Robustness to Alignment: The Gaussian similarity indices in CoMSIA are less sensitive to small changes in molecular alignment within the grid because the functions decay smoothly. CoMFA's classical potentials can produce large energy changes with small atomic displacements, especially near the van der Waals surface [25] [26].

- Application Scope: CoMSIA's inclusion of additional fields (hydrophobic, H-bond) can be advantageous for targets where these interactions are critical, providing a more holistic view of the binding landscape [25] [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Research Solutions for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Tool / Reagent / Software | Primary Function | Relevance to Field-Based vs. Similarity-Based QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL (Tripos) | Commercial molecular modeling suite | Historically the platform where CoMFA and CoMSIA were first implemented and standardized [25]. |

| GRID | Software for calculating MIFs | Pioneering structure-based approach for mapping interaction hotspots with diverse probes, foundational to the field concept [24]. |

| Python with RDKit/Scikit-learn | Open-source cheminformatics and ML | Enables custom implementation of descriptors (e.g., USRCAT) and integration of ML algorithms for model enhancement [27] [26]. |

| OPLS_2005 Force Field | Force field for molecular dynamics | Used for molecular geometry optimization and charge calculation, providing input for both CoMFA and CoMSIA studies [26]. |

| Gasteiger-Hückel Charges | Empirical method for partial atomic charge calculation | A common charge calculation method used to derive the electrostatic fields in CoMFA and CoMSIA models [26]. |

| Ultrafast Shape Recognition (USR) | Alignment-free shape similarity method | Represents a class of Gaussian-overlay based shape descriptors used for fast virtual screening, related to the similarity philosophy [27]. |

Integrated Applications and Future Directions

The combination of both field-based and similarity-based concepts with modern computational techniques represents the future of 3D-QSAR.

- Integration with Machine Learning: As demonstrated with the FTC dataset, replacing traditional PLS with machine learning algorithms like Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) can significantly improve the predictivity of CoMSIA models, overcoming limitations of linear regression [26]. This synergy allows the rich descriptor sets of 3D-QSAR to be leveraged by more powerful, non-linear fitters.

- Evolution to Quantum Mechanical Fields: A significant shift involves moving from classical force fields to Quantum Mechanical (QM)-based Molecular Interaction Fields [28]. QM-MIFs do not suffer from the fixed atom-centered charge approximation and provide a more accurate description of electron density and polarization effects. Studies show that QMFA models consistently perform equal to or better than conventional force-field-based models [28].

- Hybrid Screening Approaches: Effective virtual screening often combines the strengths of multiple methods. For instance, a workflow might use a fast chemical binding similarity method for initial filtering, followed by more computationally intensive 3D-QSAR pharmacophore or molecular docking studies for refined prediction [11]. This leverages the speed of similarity-based screening and the detailed insight of field-based and structure-based methods.

Implementation and Use Cases: Applying Field and Similarity Methods in Drug Design

In the realm of three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling, the computational workflow of molecular alignment, grid generation, and field calculation forms the essential foundation for predicting biological activity based on molecular structure. These steps transform 3D molecular structures into quantitative descriptors that can be correlated with biological endpoints. Within the broader thesis of comparing field-based and similarity-based 3D-QSAR approaches, the execution of these workflow stages fundamentally diverges, leading to distinct advantages and limitations for each paradigm. Field-based methods like CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) and CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis) rely heavily on precise molecular alignment to compute interaction energies, while modern similarity-based approaches often leverage alignment-independent descriptors or consensus models to predict binding affinity. This guide objectively breaks down these critical workflow components, supported by experimental data and comparative performance metrics.

Core Workflow Components and Comparative Analysis

The process of building a 3D-QSAR model follows a defined sequence, with methodological choices at each stage directly influencing the model's predictive performance and interpretability.

Molecular Alignment: The Conformational Foundation

Molecular alignment, or superimposition, aims to position all molecules in a shared 3D space in a manner that reflects their putative bioactive orientation. This is one of the most critical and challenging steps, especially for alignment-dependent methods [18].

- Objective: To ensure that the computed molecular descriptors correspond to equivalent spatial regions relative to a common reference, typically a known active compound or a shared pharmacophoric core [18].

Methodologies:

- Field-Based Workflow: Requires a rigorous, often manual or algorithmically complex, alignment procedure. Common techniques include scaffold-based alignment using the Bemis-Murcko framework or substructure-based alignment via the Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) [18]. The underlying assumption is that all compounds share a similar binding mode to the target protein.

- Similarity-Based Workflow: Employs strategies to minimize or bypass alignment sensitivity. For instance, the topomer approach generates a single, canonical conformation and alignment based solely on a molecule's 2D topology and a predefined fragmentation scheme, making the process fully automated and objective [29]. Other modern implementations may use consensus models that aggregate predictions from multiple alignments [30].

Experimental Protocol: A standardized protocol for field-based alignment involves:

- 3D Structure Generation: Convert 2D structures to 2D using tools like RDKit or Sybyl, followed by geometry optimization with molecular mechanics (e.g., UFF) or quantum mechanical methods [18].

- Template Selection: Identify a high-affinity ligand or a rigid core structure common to the dataset.

- Superimposition: Align all molecules to the template based on atomic correspondences of the shared scaffold or pharmacophoric features using molecular modeling software [18] [20].

Impact of Bioactive Conformations: Studies comparing 2D and 3D descriptors using bioactive conformations (from protein-ligand crystal structures) found that combining 2D and 3D descriptors often yielded more significant models, as they encode complementary molecular properties [31]. Interestingly, research on androgen receptor binders demonstrated that models using simple, non-energy-minimized 2D->3D conformations (directly converted from databases like ChemSpider) could achieve predictive performance (R²Test = 0.61) superior to models using energy-minimized or template-aligned conformations, and in a fraction of the computational time [32].

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and outcomes in the molecular alignment workflow.

Grid Generation: Defining the Calculational Space

Once molecules are aligned, a 3D grid is constructed to encompass the entire set of aligned molecules. This grid provides the points at which molecular fields will be calculated [18].

- Objective: To create a systematic lattice of points in 3D space that serves as a common framework for sampling and comparing molecular properties across the entire dataset [3].

Methodologies:

- The grid is typically defined by its bounding box (extending beyond the molecular dimensions by a margin of 4-6 Å) and its resolution (spacing between grid points, commonly 1-2 Å) [3].

- This step is largely consistent across field-based and similarity-based methods that rely on 3D grids. The key difference lies in how the grid points are utilized in the subsequent field calculation step.

Experimental Protocol:

- Calculate the spatial extent (min/max coordinates) of all aligned molecules.

- Extend the bounding box by a defined padding (e.g., 4.0 Å) in all directions to ensure the grid encompasses the molecules and their potential interaction volumes.

- Define the grid spacing (e.g., 1.0 Å or 2.0 Å). A finer grid yields more descriptors and higher resolution but increases computational cost and the risk of overfitting [18] [3].

Field Calculation: The Source of Descriptors

This is the stage where field-based and similarity-based methodologies fundamentally diverge in how they characterize molecules.

Objective: To compute numerical values at each grid point that describe the steric, electrostatic, and other physicochemical properties of the molecules [18] [3].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols:

Field-Based Descriptors (CoMFA/CoMSIA):

- CoMFA: Uses a probe atom (e.g., sp³ carbon with +1 charge) to calculate steric (Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (Coulomb potential) interaction energies at every grid point [18] [33]. A key limitation is the occurrence of abrupt energy changes near the molecular surface.

- CoMSIA: Introduces a Gaussian function to calculate similarity indices, avoiding singularities and making fields less sensitive to small alignment variations. It calculates five fields: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor [3]. The use of a Gaussian function (with an attenuation factor, typically α=0.3) ensures smooth, continuous fields [3].

Similarity-Based Descriptors:

- Methods like OpenEye's 3D-QSAR use descriptors derived from molecular similarity tools, such as shape (ROCS) and electrostatic (EON) comparisons, rather than interaction energy probes [30].

- Predictions are often generated as a consensus from multiple models employing different similarity descriptors and machine learning techniques, enhancing robustness [30].

- The topomer approach leverages the automated alignment to generate CoMFA-like fields, but its accuracy is attributed to focusing field differences only on grid points adjacent to structural changes, minimizing noise from uncertain binding geometry effects [29].

The table below summarizes a quantitative performance comparison of different 3D-QSAR approaches based on various experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of 3D-QSAR Methodologies in Practical Applications

| Methodology | Dataset / Application | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoMSIA (Field-Based) [20] | 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives (MAO-B inhibition) | q² = 0.569, r² = 0.915 (model); Successful prediction of novel derivative 31.j3 with high docking score and stable MD simulation. | Demonstrated high internal consistency and predictive power for designing novel, potent inhibitors. |

| XGBoost with 2D/3D Descriptors [22] | Pyrazole derivatives (corrosion inhibition) | Training set R² = 0.96 (2D), 0.94 (3D); Test set R² = 0.75 (2D), 0.85 (3D); RMSE < 2.84. | Machine learning on 2D/3D descriptors can yield strong predictive ability, with 3D descriptors showing better test set performance. |

| Topomer CoMFA (Similarity-Based) [29] | 140 structures across 4 industrial drug discovery projects (prospective testing) | Average pIC50 prediction error = 0.5. | Unprecedented prediction accuracy in real-world prospective applications, attributed to reduced noise from binding geometry ambiguities. |

| 2D->3D Conformation (Alignment-Independent 3D-SDAR) [32] | 146 androgen receptor binders | R²Test = 0.61 (vs. 0.56-0.61 for other conformations). | Achieved superior predictive accuracy with minimal computational overhead, suggesting utility for large datasets and rigid targets. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful execution of 3D-QSAR workflows relies on a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources.

Table 2: Essential Tools for 3D-QSAR Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Workflow | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Suites | Software Platform | Integrated environment for structure building, optimization, alignment, and QSAR analysis. | Schrödinger, Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) (commercial); Sybyl (legacy, discontinued) [3]. |

| Cheminformatics Libraries | Programming Library | Scriptable molecular manipulation, descriptor calculation, and model building. | RDKit (open-source, used in Py-CoMSIA [3]), NumPy. |

| 3D-QSAR Specialized Tools | Specialized Software | Perform specific CoMFA/CoMSIA or similarity-based calculations. | OpenEye's 3D-QSAR (similarity-based, consensus modeling [30]), Py-CoMSIA (open-source CoMSIA implementation [3]). |

| Conformational Generators | Algorithm/Tool | Generate low-energy or bio-active 3D conformations from 2D structures. | Tools within RDKit, Concord (used in topomer generation [29]). |

| Validation & Analysis Tools | Software/Statistical | Model validation, statistical analysis, and visualization of contour maps. | Built-in PLS and cross-validation in QSAR software; PyVista for visualizations in Py-CoMSIA [3]. |

The workflows for molecular alignment, grid generation, and field calculation are not merely procedural steps but embody the core philosophical differences between field-based and similarity-based 3D-QSAR approaches. Field-based methods like CoMSIA offer high interpretability through detailed contour maps but are often gated by the challenge of achieving a correct, bioactive molecular alignment. In contrast, similarity-based and alignment-independent strategies, such as topomer CoMFA or methods using simple 2D->3D conformations, prioritize predictive robustness, automation, and objectivity, often with remarkable success in real-world drug discovery applications [29] [32] [30]. The choice between them depends on the project's specific needs: when a reliable alignment is achievable, field-based methods provide deep insight; for high-throughput prediction or when alignment is uncertain, modern similarity-based and automated approaches offer a powerful and increasingly accurate alternative. The emergence of open-source tools like Py-CoMSIA is making these advanced methodologies more accessible, promising further innovation in the field [3].

In modern drug discovery, three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling represents a pivotal methodology for understanding how the structural features of molecules influence their biological activity. Unlike traditional 2D-QSAR that utilizes numerical descriptors invariant to molecular conformation, 3D-QSAR methods consider molecules as three-dimensional objects with specific shapes and interaction potentials distributed in space [18]. Among 3D-QSAR approaches, a fundamental distinction exists between field-based and similarity-based methods, each with distinct theoretical foundations and practical applications.

Field-based descriptors are founded on the principle that a biological receptor "perceives" a ligand not as a collection of atoms, but as a composite shape with associated molecular forces [24]. These forces—steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding potentials—are systematically mapped in the space surrounding molecules to create quantitative descriptors that can be correlated with biological activity. The most established field-based techniques include Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), which have become indispensable tools in rational drug design [34] [3].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these field-based descriptors, detailing their theoretical foundations, methodological implementation, performance characteristics, and practical applications in contemporary drug discovery research.

Theoretical Foundations and Molecular Field Types

Field-based 3D-QSAR methods operate on the principle that molecular binding is inherently three-dimensional and driven by complementary interactions between a ligand and its receptor [24]. The receptor does not recognize ligands as sets of atoms and bonds, but rather as shapes carrying complex force fields. These interaction fields are quantified using the probe concept, where specific chemical groups are used to measure interaction potentials at numerous points in the space surrounding each molecule [24].

Core Field Descriptors in 3D-QSAR

Table 1: Fundamental Field-Based Descriptors in 3D-QSAR

| Field Type | Physical Basis | Probe Types Used | Computational Function | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steric | van der Waals forces | Carbon sp³ atom | Lennard-Jones potential: ( V_{LJ} = 4\varepsilon[(\frac{\sigma}{r})^{12} - (\frac{\sigma}{r})^6] ) | Molecular shape complementarity, bulk tolerance/clashes [34] [24] |

| Electrostatic | Coulombic interactions | Charged atom (+1 typically) | Coulomb's law: ( E = \frac{q1 q2}{4\pi\varepsilon r} ) | Ion-ion, ion-dipole, dipole-dipole interactions [34] [24] |

| Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic effect | Hypothetical hydrophobic probe | Gaussian-type distance-dependent function | Driven by entropic effects, crucial for membrane permeability and binding [3] |

| Hydrogen-Bond Donor | Directional H-bonding | Hydrogen atom or H-bond donor group | Gaussian function | Specificity in molecular recognition [3] |

| Hydrogen-Bond Acceptor | Directional H-bonding | Oxygen atom or H-bond acceptor group | Gaussian function | Binding affinity and selectivity [3] |

The steric field describes repulsive and attractive van der Waals forces, calculated using the Lennard-Jones potential [34]. At short distances, strong repulsion occurs due to electron cloud overlap, while weaker attractive dispersion forces operate at longer ranges [24]. The electrostatic field, governed by Coulomb's law, represents charge-charge interactions that operate over longer distances and often guide initial ligand approach to the binding site [34] [24].

Hydrophobic fields quantify the entropically driven tendency of nonpolar surfaces to associate in aqueous environments, while hydrogen-bonding fields map the direction-specific potentials for forming hydrogen bond interactions [3]. Compared to CoMFA, which primarily focuses on steric and electrostatic fields, CoMSIA incorporates additional descriptors including hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding fields, providing a more comprehensive representation of molecular interactions [3].

Methodological Implementation: From Theory to Practice

The implementation of field-based 3D-QSAR models follows a systematic workflow with multiple critical stages where methodological decisions significantly impact model quality and predictive power.

Experimental Workflow for Field-Based 3D-QSAR

The diagram below illustrates the standard workflow for developing field-based 3D-QSAR models:

Critical Methodological Considerations

Molecular Alignment Strategies

Molecular alignment constitutes perhaps the most critical step in alignment-dependent 3D-QSAR methods like CoMFA [18]. The objective is to superimpose all molecules in a shared 3D reference frame that reflects their putative bioactive conformations. Common approaches include:

- Atom-based superimposition: Direct atom-to-atom pairing between molecules based on common substructures [34]

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS): Identification of the largest shared substructure among a set of molecules [18]

- Pharmacophore-based alignment: Superimposition based on key pharmacophoric features