Ensuring Predictive Power: A Comprehensive Guide to External Validation Methods for 3D-QSAR Anticancer Models

This article provides a critical examination of external validation methodologies for 3D-Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models in anticancer drug discovery.

Ensuring Predictive Power: A Comprehensive Guide to External Validation Methods for 3D-QSAR Anticancer Models

Abstract

This article provides a critical examination of external validation methodologies for 3D-Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models in anticancer drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it addresses the foundational principles of model validation, details current methodological applications, and offers troubleshooting strategies for optimization. By synthesizing the latest research, the content delivers a comparative analysis of validation criteria—including Golbraikh-Tropsha, Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC), and rm² metrics—to guide the robust evaluation of model predictability and reliability. The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to build and select highly predictive 3D-QSAR models, thereby accelerating the development of novel oncology therapeutics.

The Critical Role of External Validation in 3D-QSAR Anticancer Modeling

In the relentless pursuit of effective anticancer therapies, computer-aided drug design has become an indispensable tool for accelerating discovery and reducing costs. Among these methods, Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling stands out for its ability to correlate the spatial and physicochemical properties of molecules with their biological activity. However, the predictive power and real-world utility of these models hinge entirely on one critical process: rigorous external validation. This review examines the fundamental principles of 3D-QSAR, its application in oncology drug discovery, and the non-negotiable requirement for robust external validation to ensure the development of reliable, translatable anticancer agents.

The Fundamentals of 3D-QSAR in Drug Design

Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) represents a significant evolution from traditional QSAR methods by incorporating the spatial characteristics of molecules. While classical 2D-QSAR utilizes numerical descriptors that are invariant to molecular conformation and orientation, 3D-QSAR derives descriptors directly from the molecule's three-dimensional structure, providing a more comprehensive understanding of interaction potentials with biological targets [1].

The core premise of 3D-QSAR is that a compound's biological activity can be correlated with its interaction fields surrounding the molecule. These fields represent how the molecule would interact with a potential binding site on a target protein. The primary methodologies for calculating these fields include Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), which form the backbone of most modern 3D-QSAR applications [1].

CoMFA calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulomb) fields on a 3D grid surrounding aligned molecules. A probe atom, typically a carbon with a +1 charge, is placed at each grid point to measure interaction energies. This method is highly sensitive to molecular alignment, requiring precise spatial congruence across all molecules in the dataset [1].

CoMSIA extends this approach by using Gaussian-type similarity functions to compute multiple fields including steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor properties. This method provides more detailed insights into structure-activity relationships and is more robust to small alignment variations, making it suitable for structurally diverse datasets [1].

The mathematical relationship between these 3D descriptors and biological activity is typically established using Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, which handles the large number of correlated descriptors by projecting them onto a smaller set of latent variables. The resulting model generates contour maps that visually guide chemists toward favorable structural modifications by highlighting regions where specific molecular features enhance or diminish biological activity [1].

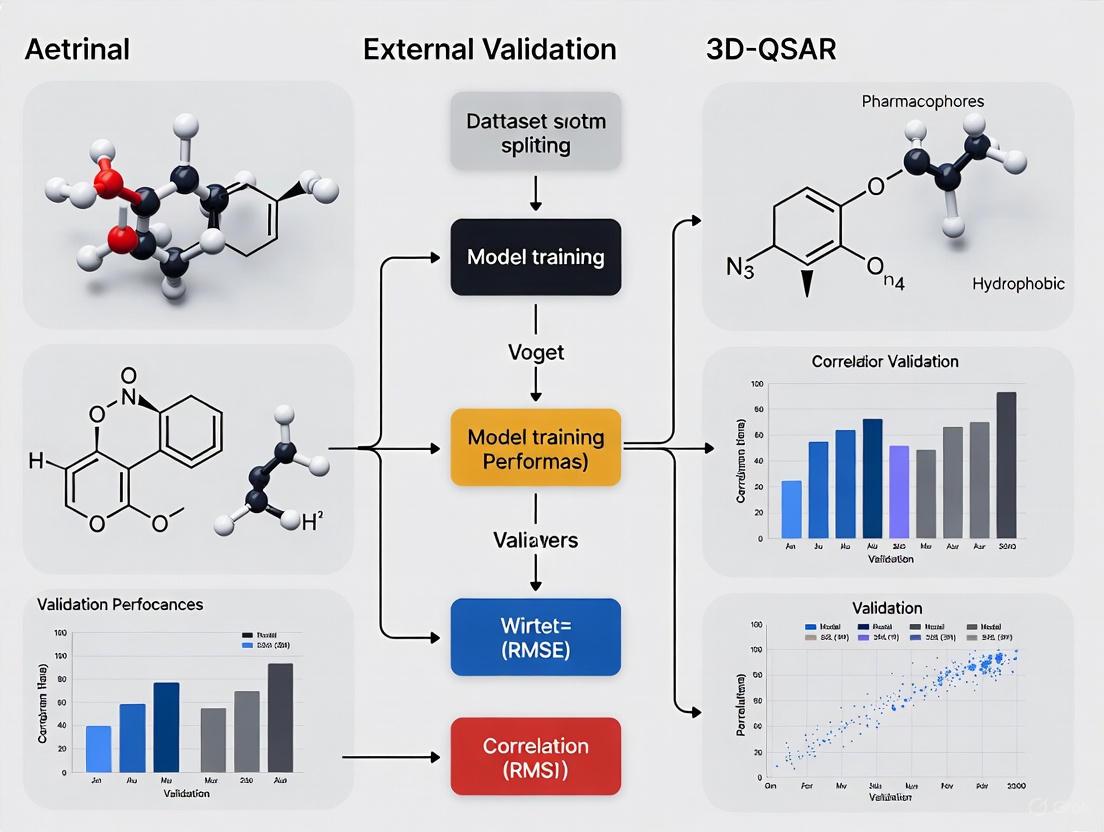

Figure 1: 3D-QSAR Modeling Workflow - This diagram illustrates the sequential process of developing and validating a 3D-QSAR model, highlighting the critical role of validation in the iterative refinement cycle.

Why External Validation is Non-Negotiable in Oncology

The high stakes of anticancer drug development demand exceptional rigor in computational models used for candidate selection. External validation serves as the ultimate test of a model's predictive power and practical utility by evaluating its performance on compounds that were entirely excluded from the model building process [2].

The Critical Limitations of Internal Validation Alone

While internal validation techniques like Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation provide useful preliminary assessments of model stability, they offer insufficient evidence of true predictive capability. A study analyzing 44 reported QSAR models revealed that relying solely on the coefficient of determination (r²) or internal validation could not adequately indicate model validity for predicting new compounds [2]. The investigation demonstrated that various established criteria for external validation each have distinct advantages and disadvantages that must be carefully considered in QSAR studies.

The fundamental challenge lies in the fact that internal validation only assesses how well the model explains the data used to create it. In oncology research, where chemical space is vast and structural diversity is the norm, this provides false confidence. Models exhibiting excellent internal statistics may fail catastrophically when confronted with structurally novel compounds, leading to wasted resources and missed opportunities [2].

Consequences of Inadequate Validation in Cancer Drug Discovery

The ramifications of using poorly validated 3D-QSAR models in oncology are particularly severe. Inaccurate predictions can direct synthetic efforts toward compounds with negligible therapeutic potential while overlooking promising candidates. Given the enormous costs and time investments required for experimental validation of anticancer compounds—including cell-based assays, animal studies, and clinical trials—the economic impact of such misdirection is substantial [3].

Furthermore, the complex pathophysiology of cancer necessitates targeting specific molecular pathways with precision. An inadequately validated model might suggest compounds that appear potent in silico but fail to engage the intended target in biological systems, or worse, produce off-target effects with toxicological consequences. Only rigorous external validation can provide the necessary confidence to advance compounds to experimental stages [4].

Current Applications in Oncology: Case Studies

The integration of rigorously validated 3D-QSAR models has advanced drug discovery across multiple cancer types, as demonstrated by these recent applications:

Breast Cancer Therapeutics

Breast cancer remains a devastating disease and a primary focus of oncological drug discovery. Several recent studies exemplify the powerful integration of 3D-QSAR with complementary computational approaches:

Antiaromatase Agents: An integrative computational strategy combining 3D-QSAR with Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), molecular docking, ADMET prediction, and molecular dynamics simulations identified 12 novel drug candidates (L1-L12) for breast cancer targeting the aromatase enzyme. Virtual screening techniques revealed one hit compound (L5) with significant potential compared to the reference drug exemestane. Subsequent stability studies and pharmacokinetic evaluations reinforced L5 as an effective aromatase inhibitor, with retrosynthetic analysis proposed for future synthesis [5].

Tubulin Inhibitors: A 2024 study explored novel 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives as tubulin inhibitors for breast cancer therapy. The QSAR model achieved a predictive accuracy (R²) of 0.849, identifying absolute electronegativity and water solubility as key descriptors influencing inhibitory activity. Molecular docking identified compound Pred28 with the highest binding affinity (-9.6 kcal/mol), while molecular dynamics simulations confirmed complex stability over 100 ns with minimal RMSD fluctuations (0.29 nm) [3].

Multitargeted Approaches: Targeting multiple oncogenic pathways simultaneously represents a promising strategy to overcome drug resistance. Research on 2-Phenylindole derivatives as multitarget inhibitors against CDK2, EGFR, and Tubulin demonstrated the power of integrated computational methods. The CoMSIA model showed high reliability (R² = 0.967) with strong cross-validation (Q² = 0.814) and external validation (R²Pred = 0.722). Six newly designed compounds exhibited superior binding affinities (-7.2 to -9.8 kcal/mol) compared to reference compounds across all three targets [4].

Neurodegenerative Disorders with Cancer Applications

While primarily focused on neurodegenerative diseases, MAO-B inhibitors have relevant applications in cancer therapy, particularly for managing treatment-related symptoms and potential direct anticancer effects:

MAO-B Inhibitors: Research on 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives as monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors exemplifies rigorous model development. The 3D-QSAR model demonstrated excellent predictive ability with q² = 0.569 and r² = 0.915. Based on model insights, researchers designed novel derivatives, with compound 31.j3 showing the highest predicted activity and docking scores. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed binding stability with RMSD values fluctuating between 1.0-2.0 Å, indicating strong conformational stability [6].

Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Thyroid Cancer

The investigation of thyroid peroxidase (TPO) inhibitors demonstrates the application of 3D-QSAR for identifying potential thyroid disruptors, with implications for understanding environmental factors in thyroid cancer:

TPO Inhibitors: A 2024 study developed and experimentally validated 3D-QSAR models for screening thyroid peroxidase inhibitors. After curating 190 human TPO inhibitors with IC₅₀ values, researchers built machine learning models including k-Nearest Neighbor (kNN) and Random Forest (RF), subsequently validating them using an external experimental dataset containing 10 molecules. The models demonstrated 100% accuracy in qualitatively identifying all 10 molecules as TPO inhibitors, with docking studies confirming selective TPO inhibition over the sodium iodide symporter (NIS) [7].

Table 1: Recent Applications of Validated 3D-QSAR Models in Oncology Research

| Cancer Type | Molecular Target | Model Statistics | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Aromatase | Rigorous internal/external validation | 12 novel candidates designed, compound L5 showed superior potential to exemestane | [5] |

| Breast Cancer | Tubulin | R² = 0.849 | Pred28 identified with highest binding affinity (-9.6 kcal/mol) and stability (RMSD 0.29 nm) | [3] |

| Breast Cancer | CDK2, EGFR, Tubulin | R² = 0.967, Q² = 0.814, R²Pred = 0.722 | Six novel compounds with multi-target inhibition superior to reference drugs | [4] |

| Neurodegenerative (Cancer-related) | MAO-B | q² = 0.569, r² = 0.915 | Compound 31.j3 showed highest activity and stable binding (RMSD 1.0-2.0 Å) | [6] |

| Thyroid | Thyroid Peroxidase | 100% accuracy on external set | Machine learning models identified 10/10 TPO inhibitors correctly in external validation | [7] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The development of robust, externally validated 3D-QSAR models follows a standardized workflow with critical steps that ensure reliability and predictive power:

Data Set Preparation and Division

The foundation of any QSAR model is a high-quality, curated dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (typically IC₅₀ or EC₅₀ values). The integrity of this dataset is paramount, requiring molecules to be structurally related yet sufficiently diverse to capture meaningful structure-activity relationships. All activity data must be acquired under uniform experimental conditions to minimize variability and systemic bias [1].

For validation purposes, the dataset is strategically divided into training and test sets. Common splits include 80:20 or 70:30 ratios, with the training set used for model development and the test set reserved exclusively for external validation. This division must ensure that both sets adequately represent the structural and activity space of the entire dataset [3].

Molecular Modeling and Alignment

Molecular structures are constructed from 2D representations and converted to 3D coordinates using cheminformatics tools like RDKit or Sybyl. Geometry optimization is performed using molecular mechanics (e.g., Tripos force field) or quantum mechanical methods (e.g., DFT/B3LYP) to ensure realistic, low-energy conformations [3] [1].

Molecular alignment represents the most critical technical step in 3D-QSAR. Multiple approaches exist:

- Distill alignment: Uses the most active compound as a template for superimposing all other molecules [4]

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS): Identifies the largest shared substructure for alignment, useful for diverse datasets [1]

- Pharmacophore-based alignment: Utilizes putative pharmacophoric elements to guide molecular superposition

The alignment assumption—that all compounds share a similar binding mode—fundamentally influences model quality and must be carefully considered [1].

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building

For CoMFA studies, descriptor fields are computed within a 3D cubic grid with typically 2Å spacing, extending beyond the dimensions of all aligned molecules. At each grid point, steric and electrostatic fields are calculated using a probe atom (typically an sp³ carbon with +1 charge). CoMSIA extends this approach to include hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor fields using Gaussian-type functions [4].

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression establishes the correlation between descriptor fields and biological activity. The optimal number of components is determined through Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation, seeking the highest cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) and lowest standard error of estimate (SEE). Non-cross-validated analysis then assesses overall model significance using conventional R², F-value, and SEE [4].

Validation Protocols

Comprehensive validation employs multiple strategies:

- Internal validation: LOO or Leave-Many-Out cross-validation

- External validation: Prediction of test set compounds excluded from model building

- Statistical metrics: Q², R²Pred, concordance correlation coefficient, RMSEP

- Applicability domain: Assessing whether new compounds fall within the model's structural domain [2]

The external validation represents the gold standard, with R²Pred > 0.6 generally considered acceptable for predictive models [2].

Figure 2: External Validation Protocol - This flowchart outlines the rigorous process for externally validating 3D-QSAR models, highlighting the critical assessment step that determines model acceptability based on statistical criteria.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of 3D-QSAR in oncology research requires specific computational tools and analytical resources. The following table summarizes key components of the methodology and their functions in the drug discovery pipeline:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR in Oncology

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Software | Sybyl-X, RDKit, ChemDraw | 2D to 3D structure conversion, molecular optimization, and descriptor calculation |

| Force Fields | Tripos MMFF94, UFF, DFT/B3LYP | Geometry optimization and energy minimization of molecular structures |

| Molecular Alignment Tools | Distill alignment, MCS, Pharmacophore alignment | Spatial superposition of molecules based on common scaffolds or pharmacophoric features |

| 3D-QSAR Methods | CoMFA, CoMSIA | Calculation of steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and H-bond interaction fields |

| Statistical Analysis | PLS regression, kNN, Random Forest | Correlation of descriptor fields with biological activity and model building |

| Validation Packages | LOO cross-validation, external test sets | Assessment of model robustness and predictive power for new compounds |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Validation of binding stability and conformational analysis of protein-ligand complexes |

| ADMET Prediction | SwissADME, pkCSM | Evaluation of drug-likeness, pharmacokinetic, and toxicity properties |

The integration of 3D-QSAR modeling in oncology drug discovery represents a powerful strategy for rational compound design and optimization. However, as demonstrated by numerous case studies across breast cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and endocrine disruption, the predictive utility and translational potential of these models depend fundamentally on rigorous external validation. The non-negotiable requirement for external validation stems from the profound consequences of model failure in the high-stakes domain of anticancer therapy development.

Researchers must implement comprehensive validation protocols that extend beyond internal cross-validation to include true external test sets, appropriate statistical metrics, and applicability domain assessment. Only through such rigorous approaches can 3D-QSAR models fulfill their promise as reliable tools for accelerating the discovery of novel anticancer agents and addressing the pressing challenges of drug resistance and therapeutic efficacy in oncology.

In the field of 3D-QSAR modeling for anticancer research, the reliability of a model is determined by its ability to make accurate predictions for new, untested compounds. This predictive prowess is formally assessed through two distinct but complementary processes: internal and external validation. Internal validation evaluates the model's stability and robustness within the training dataset, while external validation tests its true predictive power on a completely independent set of compounds, defining its practical utility in drug discovery [2] [8].

Core Concepts and Definitions

Internal Validation

Internal validation assesses the robustness and stability of a 3D-QSAR model using the same data from which it was built, typically through cross-validation techniques. Its primary purpose is to ensure the model is not over-fitted and to provide an initial estimate of its predictive capability during the development phase [9] [8]. The most common method is Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation, where one compound is repeatedly omitted from the training set, the model is rebuilt with the remaining compounds, and its activity is predicted. This process repeats until every compound has been left out once [9]. For a 3D-QSAR model to be considered internally robust, the LOO cross-validated correlation coefficient ((q^2)) should typically be greater than 0.5 [10] [9].

External Validation

External validation is the definitive test of a model's predictive power, performed using a separate test set of compounds that were not involved in any part of the model-building process [2] [8]. This process answers a critical question for drug developers: can the model accurately predict the activity of truly novel compounds? A model that passes external validation demonstrates generalizability, confirming that the structure-activity relationships it has learned are not mere statistical artifacts but are applicable to a broader chemical space [2]. According to widely accepted criteria, the predictive correlation coefficient ((R^2_{pred})) should be greater than 0.5, and the mean absolute error (MAE) should satisfy MAE ≤ 0.1 × training set activity range [10].

The table below synthesizes key statistical parameters and their accepted thresholds for internal and external validation, providing a clear framework for evaluating 3D-QSAR models in anticancer research.

Table 1: Key Validation Parameters and Their Thresholds for 3D-QSAR Models

| Parameter | Role in Validation | Interpretation & Accepted Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| (q^2) (LOO Cross-Validation) | Internal Validation | Indicates model robustness. Generally requires > 0.5 [10] [9]. |

| (R^2) (Coefficient of Determination) | Goodness-of-Fit | Measures how well the model fits the training data. Should be high (e.g., > 0.8-0.9) but alone is insufficient for validity [2] [9]. |

| (R^2_{pred}) (Predictive (R^2)) | External Validation | Measures predictive power on an external test set. Requires > 0.5 [10]. |

| MAE (Mean Absolute Error) | External Validation | Measures average prediction error. Should meet MAE ≤ 0.1 × training set range [10]. |

| Golbraikh & Tropsha Criteria | External Validation | A set of statistical criteria (e.g., (R^2) > 0.6, slope (k) between 0.85-1.15) to confirm model reliability [10]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the standard 3D-QSAR development process and the critical roles that internal and external validation play within it.

3D-QSAR Model Development and Validation Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Internal Validation via Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation

This protocol is a standard procedure for assessing model robustness, as demonstrated in studies on maslinic acid analogs and other anticancer agents [9] [11].

- Model Building with Omission: From a training set of N compounds, remove one compound (i).

- Rebuild and Predict: Use the remaining N-1 compounds to rebuild the complete 3D-QSAR model. The model parameters (e.g., PLS components, field contributions) are recalculated.

- Predict Omitted Activity: Use the newly built model to predict the biological activity (e.g., pIC50) of the omitted compound (i).

- Iterate: Repeat steps 1-3 for all N compounds in the training set, ensuring each compound is left out exactly once.

- Calculate (q^2): Compute the LOO cross-validated correlation coefficient ((q^2)) using the formula: (q^2 = 1 - \frac{\sum{(Y{actual} - Y{predicted})^2}}{\sum{(Y{actual} - \bar{Y}{training})^2}}) where (Y{actual}) and (Y{predicted}) are the actual and predicted activities of the left-out compounds, and (\bar{Y}_{training}) is the mean activity of the training set. A (q^2 > 0.5) is typically considered indicative of a robust model [9].

Protocol 2: Comprehensive External Validation

This protocol outlines a multi-faceted approach to external validation, incorporating several statistical criteria to thoroughly evaluate predictive power [2] [10].

- Initial Data Splitting: Prior to model development, the full dataset is divided into a training set (typically 70-80%) for model building and a test set (20-30%) for validation. The test set must contain compounds representing the full range of biological activity and must be strictly withheld from the model-building process [11].

- Predict Test Set Activities: After the final model is developed using only the training set, use it to predict the activities of the compounds in the external test set.

- Calculate Key Metrics:

- Predictive (R^2{pred}): Calculate using the formula: (R^2{pred} = 1 - \frac{PRESS}{SD}) where PRESS is the sum of squared deviations between the actual and predicted activity of the test compounds, and SD is the sum of squared deviations between the actual activity of test compounds and the mean activity of the training set [10]. A value > 0.5 is required.

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): Calculate as: (MAE = \frac{1}{N{test}}\sum{|Y{actual} - Y_{predicted}|}) For the model to have high predictive accuracy, the MAE should be less than or equal to 0.1 times the activity range of the training set [10].

- Apply Golbraikh & Tropsha Criteria: For further statistical rigor, apply this set of criteria to the test set predictions [10]:

- The correlation coefficient ((R^2)) from a regression of predicted vs. actual activities should be > 0.6.

- The slope of the regression line ((k)) should be between 0.85 and 1.15.

- The difference between (R^2) and the coefficient of determination through the origin ((R0^2)) should be small: ((R^2 - R0^2)/R^2 < 0.1).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful development and validation of 3D-QSAR models rely on a suite of specialized software tools and computational reagents.

Table 2: Essential Tools for 3D-QSAR Modeling and Validation

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL-X [11] | Software Suite | A comprehensive molecular modeling environment used for structure sketching, energy minimization, and running CoMFA/CoMSIA studies. |

| Forge [9] | Software | Used for field-based pharmacophore generation, molecular alignment, and field-based 3D-QSAR model development using XED force field. |

| Dragon [2] | Software | Calculates thousands of molecular descriptors for 2D- and 3D-QSAR analyses, though feature selection is critical. |

| CODESSA [12] | Software | Calculates a wide range of molecular descriptors (quantum chemical, topological, geometrical) for QSAR model building. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Algorithm | The core regression algorithm used in 3D-QSAR (e.g., CoMFA, CoMSIA) to correlate molecular field variables with biological activity [10] [9]. |

| Gasteiger-Huckel Charges [11] | Computational Method | A method for assigning partial atomic charges to molecules, which is a critical step in preparing structures for 3D-QSAR analysis. |

| Tripos Force Field [11] | Molecular Mechanics | A force field used for energy minimization of molecular structures to obtain stable 3D conformations before alignment. |

| FieldTemplater [9] | Software Module | Generates a pharmacophore hypothesis based on molecular fields and shape to guide the alignment of compounds for 3D-QSAR. |

Internal and external validation serve non-overlapping roles in 3D-QSAR modeling. Internal validation, quantified by (q^2), is a necessary check for model robustness during development. However, it is external validation, with its stringent metrics like (R^2_{pred}) and MAE, that ultimately certifies a model's predictive scope and its readiness to be deployed in the rational design of novel anticancer agents. Relying solely on internal validation or the training set's (R^2) can be misleading, as these metrics do not guarantee performance on unseen data [2]. A rigorous, multi-faceted validation strategy is therefore the core principle that separates computationally derived hypotheses from truly predictive tools in drug discovery.

In the field of anticancer drug discovery, Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling serves as a pivotal computational technique for predicting the biological activity of novel compounds. These models mathematically relate the spatial and physicochemical properties of molecules to their anticancer efficacy, guiding the optimization of lead compounds. However, the predictive power and real-world applicability of these models are critically dependent on the rigor of their external validation—the process of evaluating a model's performance on compounds not used during its training. Inadequate validation practices can create a deceptive illusion of model accuracy, leading to severe downstream consequences including unforeseen toxicities, the promotion of drug resistance, and significant waste of valuable scientific resources. This guide provides a comparative analysis of validation methodologies, highlighting the experimental protocols and quantitative metrics that distinguish reliable 3D-QSAR models from poorly validated ones, framed within the broader thesis that robust external validation is non-negotiable for successful anticancer research.

The Critical Role of External Validation in 3D-QSAR

Defining External Validation

External validation is the definitive step for assessing the reliability and predictive power of a QSAR model for new, untested compounds. It involves splitting the available dataset into a training set, used to build the model, and an independent test set, used exclusively for final evaluation [8]. This process answers a critical question: Can the model accurately predict the activity of compounds it has never encountered before? In the context of 3D-QSAR, which considers the three-dimensional conformations and molecular fields of compounds, validation becomes even more complex. A model must not only be statistically sound but also biologically relevant, ensuring that predicted activity aligns with real-world interactions in a biological system.

Limitations of Internal Validation and R²

A common pitfall in QSAR modeling is over-reliance on internal validation metrics and the coefficient of determination (R²) alone. Internal validation techniques, such as Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation, use the training data to estimate performance but can produce overly optimistic results [2] [8]. A high R² value indicates how well the model fits the data it was trained on, but it is not a sufficient indicator of its predictive capability for new compounds. A study evaluating 44 reported QSAR models found that employing R² alone could not indicate the validity of a model, underscoring the necessity of rigorous external validation procedures [2].

Comparative Analysis of 3D-QSAR Validation in Anticancer Research

The table below summarizes the validation outcomes from recent 3D-QSAR studies focused on different anticancer targets, illustrating the correlation between validation rigor and model reliability.

Table 1: Comparison of 3D-QSAR Model Validation in Anticancer Studies

| Cancer Type / Target | Model Type | Key Validation Metrics | Outcome & Consequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer (Aromatase) | CoMSIA | Q² = 0.628, R² = 0.928, R²pred (External) | High predictive accuracy; reliable for candidate screening. [13] | |

| Breast Cancer (MCF-7 Cell Line) | Field-based 3D-QSAR | r² = 0.92, q² = 0.75 (LOO), External Test Set | Model successfully identified a best-hit compound (P-902) with confirmed activity. [9] | |

| Neurodegeneration (MAO-B Inhibitors) | CoMSIA | q² = 0.569, r² = 0.915, External Test Set, Molecular Dynamics | Good predictive ability; designed stable, potent inhibitors verified by simulation. [14] | |

| General QSAR Analysis | Various (44 models) | Over-reliance on R² alone | Models deemed unreliable; cannot guarantee predictive power for new compounds. [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Robust Validation

The following workflow outlines the standard protocol for developing and rigorously validating a 3D-QSAR model, integrating best practices from the cited studies.

Figure 1: 3D-QSAR Development and Validation Workflow

1. Dataset Curation and Division: The process begins with compiling a dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC50 values), often expressed as pIC50 (-logIC50) for modeling [9]. A critical step is the activity-stratified partitioning of this dataset into a training set (typically 70-80%) for model building and a test set (20-30%) for external validation. This ensures both sets cover a similar range of activity [9] [13].

2. Molecular Modeling and Alignment: 2D chemical structures are converted into 3D models and their geometries are optimized using force fields (e.g., TRIPOS, MMFF94) [15]. For 3D-QSAR, a sensitive and crucial step is the alignment of all molecules into a common 3D space. This is often done based on a common pharmacophore hypothesis or by aligning them onto the structure of the most active compound [15] [9].

3. Descriptor Calculation and Model Construction: Molecular field descriptors are calculated. In methods like Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), these include steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor fields [15]. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is then used to build the quantitative model that relates these molecular fields to the biological activity [9].

4. Internal and External Validation: The model undergoes internal validation, primarily through Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation, to yield the cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) and to prevent overfitting [8] [9]. The model's predictive power is then truly tested by predicting the activities of the external test set. Key metrics here include the predictive R² (R²pred) and the standard error of prediction [15] [13].

5. Model Application and Experimental Verification: A well-validated model is used to predict the activity of newly designed compounds and to guide lead optimization through contour map analysis. The ultimate validation involves the synthesis and experimental testing of top-predicted compounds to confirm model accuracy, closing the loop between in silico prediction and empirical reality [7] [9].

Consequences of Poor Validation Practices

Unforeseen Toxicity

Poorly validated models carry a high risk of failing to predict toxic off-target effects. In contrast, robust studies integrate ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) predictions early in the design process. For instance, a study on maslinic acid analogs filtered predicted compounds through Lipinski's Rule of Five and ADMET risk assessment to eliminate candidates with poor drug-likeness or high toxicity potential [9]. Without this rigorous vetting, a model might optimize solely for potency, inadvertently selecting compounds that are hepatotoxic, cardiotoxic, or possess other dangerous side profiles. Unexpected toxicity accounts for nearly 30% of failures in drug development [16], a risk that is magnified by inadequate computational models.

Propagation of Drug Resistance

In the context of antibiotics, poor QSAR validation has direct implications for drug resistance. A study on quinolone antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) used molecular docking and 3D-QSAR to design a modified quinolone derivative (ORB-19) intended to inhibit the toxic expression of ARGs [17]. A poorly validated model might misidentify key structural features controlling this interaction, leading to the design of compounds that continue to apply strong selective pressure, ultimately promoting the spread of resistance rather than suppressing it.

Significant Resource Waste

The development of a drug candidate from concept to market requires immense investment, often exceeding billions of dollars and over a decade of work. Pursuing leads based on flawed computational predictions represents a catastrophic waste of financial resources, time, and scientific effort. It directs synthetic and experimental biology work towards compounds with a low probability of success. Robust validation acts as a crucial quality control checkpoint, preventing the waste of resources on dead-end compounds and increasing the overall efficiency of the drug discovery pipeline [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

The table below details key resources commonly used in the development and validation of 3D-QSAR models for anticancer research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software for 3D-QSAR

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in 3D-QSAR | Relevance to Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sybyl/X | Software Suite | Molecular modeling, structure optimization, CoMFA/CoMSIA analysis. | Platform for calculating field descriptors and generating the initial model. [15] [14] |

| Forge | Software | Field-based QSAR, pharmacophore generation, and activity-atlas modeling. | Uses field point descriptors and provides advanced validation through activity cliffs. [9] |

| CHEMBIODRAW | Software | Chemical structure drawing and 2D to 3D structure conversion. | Prepares initial molecular structures for subsequent modeling steps. [14] [13] |

| CODESSA | Software | Calculates a wide range of molecular descriptors (quantum chemical, topological, etc.). | Provides descriptors for 2D-QSAR and can be used to complement 3D-QSAR findings. [13] |

| PLSR | Algorithm (Partial Least Squares Regression) | Core statistical method for building the QSAR model from molecular descriptors/fields. | Directly generates key statistical metrics (R², q²) for internal validation. [9] [13] |

| ZINC Database | Online Database | Public repository of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Source for external compounds to test model predictability beyond the training set. [9] |

| pIC50 | Biological Metric | Negative logarithm of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration; the common dependent variable. | Standardizes activity data for modeling; high-quality data is the foundation of a valid model. [9] |

The path from a computational model to a clinically effective anticancer drug is fraught with challenges. The evidence is clear that rigorous external validation of 3D-QSAR models is not an optional academic exercise but a fundamental prerequisite for success. As summarized in this guide, robust validation, characterized by strict dataset division, multiple statistical metrics (Q², R²pred), and experimental follow-up, leads to reliable, predictive models that can efficiently guide drug discovery. In contrast, poor validation creates a facade of success, directly enabling the dire consequences of clinical toxicity, amplified drug resistance, and the profound waste of the limited resources dedicated to fighting cancer. For researchers in the field, adopting the stringent protocols and tools outlined here is essential for ensuring their work contributes to viable solutions rather than costly failures.

In the field of 3D-QSAR modeling for anticancer research, the reliability of a model is not determined by its performance on training data alone. Robust external validation is crucial to ensure that a model can make accurate predictions for new, unseen compounds, thereby providing genuine value in drug discovery pipelines. This guide objectively compares the core metrics and concepts—Q², R²pred, RMSE, and Applicability Domain (AD)—used to evaluate the predictive power of 3D-QSAR models, with supporting data from recent anticancer studies.

Core Validation Metrics at a Glance

The following table defines the key terminology and its role in model validation.

| Term | Full Name | Primary Role in Validation | Interpretation in Anticancer QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q² | Cross-validated Coefficient of Determination | Assesses internal robustness and reliability of the model through data resampling [2]. | A high Q² (>0.5) suggests the model can reliably predict the activity (e.g., pIC50) of compounds within the training set's chemical space [18]. |

| R²pred | Predictive Coefficient of Determination | Evaluates external predictability on a completely independent test set [2]. | An R²pred > 0.6 indicates the model can successfully forecast the anticancer activity of novel, untested compounds [19] [15]. |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error | Quantifies the average prediction error in the units of the biological activity [20]. | A lower RMSE is desired. It directly estimates the expected error in predicting activity values, crucial for prioritizing potent candidates [21]. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) | Applicability Domain | Defines the chemical space where the model's predictions are considered reliable [15]. | Ensures that a prediction for a new compound is trusted only if the compound is structurally similar to those used to build the model [22]. |

Quantitative Comparison from Recent Anticancer QSAR Studies

The table below summarizes the performance of various QSAR models reported in published anticancer research, providing a benchmark for these key metrics.

| Study Focus / Model Type | Q² (Internal) | R²pred (External) | RMSE (External) | Key Findings & Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tubulin Inhibitors (Quinoline derivatives) [18] | 0.718 | 0.774 | N/R | The pharmacophore-based 3D-QSAR model showed high predictive ability for external compounds, confirming its utility in virtual screening. |

| ALK Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (GA-MLR Model) [21] | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.57 | The model demonstrated a strong balance between internal robustness (high Q²) and external predictive power (high R²pred, low RMSE). |

| Breast Cancer (Thioquinazolinone derivatives, CoMSIA) [15] | N/R | "Significant" | N/R | The model's external prediction capability was validated, and its AD was defined to identify reliable drug candidates. |

| Anticancer Compounds on SK-MEL-2 Cell Line [23] | 0.845 | 0.799 | N/R | The QSAR model was used to design new compounds with improved predicted activity, which were then validated via molecular docking. |

| Benzimidazole Derivatives (CoMFA model) [19] | 0.613 | 0.714 | N/R | The 3D-QSAR model provided useful information for the design of new angiotensin II-AT1 receptor antagonists. |

N/R: Not explicitly reported in the provided search results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Building and validating a 3D-QSAR model requires a suite of specialized software tools.

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL-X [24] | Commercial Software | Industry-standard platform for performing CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses [19]. |

| Schrödinger Phase | Commercial Software | Integrated environment for pharmacophore modeling and 3D-QSAR studies [18] [24]. |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Commercial Software | Provides comprehensive tools for 3D-QSAR modeling, molecular visualization, and alignment [20] [24]. |

| Open3DQSAR | Open-Source Software | A free platform for building and analyzing 3D-QSAR models [24]. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Descriptor Calculator | Software tool used to generate molecular descriptors from chemical structures [23]. |

| OMEGA | Conformer Generator | Tool for generating representative 3D conformations of molecules, a critical step before alignment [24]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Analyses

Protocol 1: External Validation with a Test Set

This is the fundamental protocol for assessing a model's real-world predictive power [2].

- Data Set Division: Randomly split the full dataset of compounds into a training set (typically ~70-80%) for model building and a test set (the remaining ~20-30%) for validation [18] [23]. The test set must be kept completely separate from the model development process.

- Model Construction: Build the 3D-QSAR model (e.g., CoMFA or CoMSIA) using only the compounds in the training set [19].

- Activity Prediction: Use the finalized model to predict the biological activity (e.g., pIC50) of the compounds in the test set.

- Calculation of R²pred and RMSE:

- R²pred is calculated by comparing the experimental activity of the test set compounds with their model-predicted activities [2]. The formula is based on the sum of squared differences between predicted and experimental values versus the sum of squared differences between experimental values and the mean activity of the training set.

- RMSE is calculated as the root mean square of the errors between the predicted and experimental activities for the test set compounds [21]. A lower RMSE indicates higher prediction accuracy.

Protocol 2: Defining the Applicability Domain (AD)

The AD ensures that predictions are only made for compounds structurally similar to the training set [22].

- Descriptor Calculation: Calculate the same set of molecular descriptors used in the QSAR model for all compounds in the training set.

- Define the Domain: The AD is often defined using leveraged-based methods. For each compound, leverage is calculated based on its descriptor values relative to the model's descriptor space [15].

- Set a Threshold: A common threshold is to define a Williams plot, which plots standardized residuals versus leverage. A critical leverage value (h*) is typically set to 3p'/n, where p' is the number of model descriptors plus one, and n is the number of training compounds.

- Check New Compounds: For any new compound, its leverage is calculated. If the leverage is greater than the critical threshold (h*), the compound is considered outside the AD, and its prediction may be unreliable [15].

Workflow for 3D-QSAR Model Development and Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of building and rigorously validating a 3D-QSAR model, integrating the key concepts and metrics discussed.

Diagram: The 3D-QSAR Validation Workflow from model building to reliable prediction.

In the context of developing 3D-QSAR models for anticancer research, reliance on a single metric provides an incomplete picture of model quality. A robust validation strategy is multi-faceted. It requires demonstrating internal robustness (Q²), proving external predictability (R²pred), quantifying the expected error (RMSE), and honestly defining the bounds of reliability (Applicability Domain). The comparative data and protocols outlined in this guide provide a framework for researchers to critically evaluate and transparently report the performance of their models, thereby strengthening the path from computational prediction to experimental validation in cancer drug discovery.

Implementing Robust External Validation Protocols: From Theory to Practice

In computational drug discovery, the robustness and predictive power of a Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model are fundamentally determined by the strategy employed for dataset curation and splitting. For 3D-QSAR models targeting complex anticancer mechanisms, proper division of data into training and test sets is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of model validity and translational potential. The 80:20 split, where 80% of data trains the model and 20% provides an unbiased evaluation, represents a widely adopted starting point in the field. This practice balances the competing needs of sufficient training data for pattern recognition against adequate testing data for performance validation [25] [26].

The imperative for rigorous external validation in anticancer QSAR research stems from the high stakes of drug development, where false positives can waste valuable resources and delay therapeutic advances. External validation using a properly reserved test set simulates real-world prediction scenarios on genuinely novel compounds, providing a realistic assessment of model utility before costly experimental synthesis and biological testing [27] [28]. This article examines dataset splitting methodologies within the specific context of 3D-QSAR modeling for anticancer research, comparing implementation strategies and providing evidence-based protocols to enhance model reliability.

Comparative Analysis of Data Splitting Methodologies

Splitting Ratio Performance Comparison

The choice of splitting ratio involves trade-offs between model training stability and evaluation reliability. The following table summarizes key characteristics of common splitting strategies as implemented in anticancer QSAR studies:

Table 1: Comparison of Dataset Splitting Strategies in QSAR Modeling

| Split Ratio (Train:Test) | Optimal Dataset Size | Variance in Parameter Estimates | Variance in Performance Statistics | Common Applications in Anticancer QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80:20 | Medium to Large (>1,000 compounds) | Low | Moderate | Full 3D-QSAR workflows with external validation [26] [27] |

| 70:30 | Small to Medium (100-1,000 compounds) | Moderate | Low | Initial screening models with limited data availability [26] |

| 90:10 | Very Large (>10,000 compounds) | Very Low | High | Large-scale virtual screening of commercial libraries [26] |

| 60:20:20 (Train:Val:Test) | Medium to Large (>2,000 compounds) | Low (Training) | Low (Validation & Test) | Hyperparameter tuning with rigorous validation [26] |

Statistical Foundations of the 80:20 Split

The 80:20 ratio finds statistical support through the Pareto principle, with empirical validation across numerous QSAR applications. Research indicates that with approximately 80% of data allocated to training, models achieve sufficient parameter stability while maintaining a test set large enough to yield performance metrics with acceptable variance [26]. For datasets of typical size in anticancer research (often hundreds to thousands of compounds), this ratio provides an optimal balance—approximately 80% of data generates robust parameter estimates, while 20% provides a reliable performance assessment without sacrificing excessive training material [26] [27].

Theoretical work by Guyon (1996) suggests the ideal validation-to-training-set ratio should scale inversely with the square root of the number of free adjustable parameters. For QSAR models with approximately 25-30 adjustable descriptors, this relationship yields a recommended validation fraction near 20%, mathematically supporting the 80:20 convention [26]. In practice, the 33-compound phenylindole derivative study targeting MCF-7 breast cancer cells implemented exactly this approach, with 28 compounds (85%) for training and 5 (15%) for external testing, demonstrating robust predictive capability (R²Pred = 0.722) [4].

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Model Validation

Standardized 80:20 Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for proper dataset splitting and model validation in 3D-QSAR anticancer studies:

Diagram 1: QSAR dataset splitting and validation workflow

Case Study: Implementation in Acylshikonin Anticancer Research

A recent investigation of acylshikonin derivatives for anticancer activity exemplifies rigorous 80:20 implementation. Researchers evaluated 24 compounds using an integrated QSAR-docking-ADMET framework. The dataset was split following the 80:20 convention, with 80% of compounds (19 derivatives) building the PCA-based QSAR model and 20% (5 derivatives) reserved for external validation. This approach yielded a highly predictive model (R² = 0.912, RMSE = 0.119) that successfully identified compound D1 as a promising candidate through subsequent molecular docking studies [29].

The validation protocol incorporated both internal leave-one-out cross-validation on the training set and external validation using the held-out test compounds. This two-tier approach ensured the model was neither overfitted to the training data nor dependent on a single validation method, establishing confidence in its predictive capability for novel shikonin-based anticancer agents [29].

Advanced Protocol: Three-Way Data Partitioning

For complex 3D-QSAR studies requiring hyperparameter optimization, a three-way split incorporating a separate validation set is recommended:

Table 2: Three-Way Data Partitioning for Advanced QSAR Modeling

| Data Segment | Function | Typical Size | Implementation in Anticancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Set | Model fitting and parameter estimation | 60% | Used to develop the initial 3D-QSAR model using CoMSIA/CoMFA fields [6] [4] |

| Validation Set | Hyperparameter tuning and model selection | 20% | Optimizes parameters such as grid spacing, field contributions, and PLS components [30] |

| Test Set | Final unbiased performance evaluation | 20% | Provides the external validation metric (R²Pred) reported in publications [4] |

This approach was effectively employed in the development of 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives as monoamine oxidase B inhibitors, where it helped create a highly predictive COMSIA model (q² = 0.569, r² = 0.915) while maintaining rigorous external validation standards [6].

Table 3: Essential Resources for 3D-QSAR Dataset Curation and Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function in Dataset Splitting & QSAR Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Software | SYBYL 2.0 [4], ChemDraw [6], Rdkit [31] | Compound structure sketching, optimization, and descriptor calculation |

| QSAR Modeling Platforms | COMSIA/CoMFA [4], Auto-Modeller [31], Scikit-learn [27] | 3D-QSAR model development, validation, and prediction |

| Data Splitting Utilities | Scikit-learn traintestsplit() [27], Stratified Sampling [30] | Randomized dataset division with optional stratification |

| Validation Metrics | LOO Cross-Validation [4], External Validation (R²Pred) [4], RMSE [29] | Model performance assessment on training and external test sets |

| Specialized Libraries | Therapeutic Data Commons [31], Brazilian Compound Library [28] | Curated compound databases for model building and validation |

The 80:20 dataset splitting ratio represents a validated standard in 3D-QSAR anticancer research, balancing the competing demands of comprehensive model training and rigorous external validation. Evidence from recent studies on phenylindole, acylshikonin, and benzothiazole derivatives confirms that this approach, when implemented with proper randomization and stratification protocols, yields models with strong predictive power and translational potential. The strategic curation of datasets following these best practices provides the foundation for computational models that can genuinely accelerate anticancer drug discovery by prioritizing the most promising candidates for experimental validation.

As the field advances toward larger datasets and more complex multi-target modeling approaches, the fundamental principles of proper data splitting remain essential. Maintaining a dedicated external test set represents a non-negotiable standard for establishing model credibility, ensuring that promising computational predictions undergo unbiased evaluation before guiding resource-intensive synthetic and biological testing efforts.

The predictive accuracy of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, particularly in critical fields like anticancer research, is paramount. External validation is the definitive test, assessing a model's ability to predict the activity of new, untested compounds reliably [2]. Within 3D-QSAR modeling for anticancer research, this process ensures that computational predictions on novel drug candidates translate into real-world therapeutic potential. Several established statistical frameworks exist to judge this predictive power. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three pivotal approaches: the Golbraikh-Tropsha criteria, Roy's rm² metrics, and the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC). Adherence to these stringent validation standards is crucial for developing trustworthy computational tools that can accelerate the discovery of new anticancer agents.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Metrics

The following table summarizes the core principles, key parameters, and acceptance criteria for the three validation methods.

Table 1: Overview of Key External Validation Methods for QSAR Models

| Validation Method | Core Principle | Key Parameters | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golbraikh-Tropsha Criteria [32] [33] | A set of multiple statistical conditions that must be simultaneously satisfied to confirm model predictivity. | - ( R^2{pred} ) (Predictive ( R^2 ))- ( r^20 ) (or ( r'^2_0 ))- Slope of regression lines (( k ) or ( k' )) | - ( R^2{pred} > 0.5 ) [33]- ( \mid r^20 - r'^2_0 \mid < 0.3 ) [2]- ( 0.85 \leq k \leq 1.15 ) (or similar for ( k' )) |

| Roy's rm² Metrics [34] [33] [35] | A stringent metric that penalizes models for large differences between observed and predicted values. | - ( \Delta r^2m ) ( ( \mid r^2m - r'^2m \mid ) )- ( \overline{r^2m} ) (Average ( r^2m ))- ( r^2m ) (for training, test, or overall) | - ( \Delta r^2m < 0.2 ) [35]- ( \overline{r^2m} > 0.5 ) [35] |

| Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) [36] [37] [38] | Measures the agreement between two variables by combining precision (Pearson's r) and accuracy (shift from the 45° line). | - ( \rho_c ) (Lin's CCC) | - ( \rhoc > 0.90 ) (Poor to Moderate) [38]- ( \rhoc > 0.95 ) (Substantial) [38]- ( \rho_c > 0.99 ) (Almost Perfect) [38] |

Golbraikh-Tropsha Criteria

The Golbraikh-Tropsha method is not a single metric but a composite of statistical conditions that a predictive model must pass [33]. It is based on analyzing the regression between the observed and predicted values of the test set compounds. The key criteria often include the coefficient of determination from regression through the origin, and the slopes of regression lines, all designed to ensure predictions are both accurate and unbiased [34] [32].

Roy's rm² Metrics

Roy's rm² metrics were introduced to provide a stricter and more reliable validation tool compared to traditional metrics like ( R^2{pred} ), which can overestimate predictive ability when the data has a wide range of response values [33] [35]. The calculation involves correlations between observed and predicted values with (( r^2 )) and without (( r^20 )) the intercept for the least-squares regression line [33]. The metric is calculated as ( r^2m = r^2 \times (1 - \sqrt{r^2 - r^20}) ) [35]. A significant advantage is the use of the ( \Delta r^2_m ) parameter, which helps identify models with consistent performance regardless of how the observed and predicted values are assigned to the axes [33] [35].

Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC)

The Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC), introduced by Lawrence Lin, evaluates the agreement between two sets of data by measuring how well they fall along the 45-degree line of perfect concordance (the line of identity) [36] [37]. It is a product of precision (Pearson's correlation coefficient ( \rho ), which measures how far each observation deviates from the best-fit line) and accuracy (a bias correction factor ( C\beta ), which measures how far the best-fit line deviates from the 45-degree line) [37] [38]. The formula is ( \rhoc = \rho \cdot C_\beta ) [37]. This dual nature makes it superior to Pearson's r alone for validation, as it captures both linear relationship and systematic bias.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Implementing these validation metrics requires a structured workflow. The diagram below outlines the key stages from data preparation to final model validation.

Figure 1: Workflow for the External Validation of a QSAR Model.

Data Preparation and Model Development

The initial and crucial step involves rationally dividing the full experimental dataset into a training set, used to build the model, and a test set, used exclusively for external validation [32]. Best practices suggest the test set should be representative of the structural diversity and uniformly span the whole range of activity of the training set [39]. For 3D-QSAR models, such as those using CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) or CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis), molecular alignment is a sensitive and critical step [15]. The model is then developed using the training set, often with techniques like Multiple Linear Regression or Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression [2] [39].

Protocol for Applying Golbraikh-Tropsha Criteria

- Prediction: Use the developed model to predict the activities of the test set compounds.

- Regression Analysis: Perform a regression analysis between the observed (Y) and predicted (X) values of the test set.

- Calculate Key Parameters:

- Calculate ( R^2{pred} = 1 - \frac{\sum (Y{pred(test)} - Y{(test)})^2}{\sum (Y{(test)} - \bar{Y}{training})^2} ) where ( \bar{Y}{training} ) is the mean activity of the training set [33].

- Calculate the coefficients of determination for regressions through the origin: ( r^20 ) (observed vs. predicted) and ( r'^20 ) (predicted vs. observed).

- Calculate the slopes of the regression lines ( k ) and ( k' ).

- Check Criteria: The model is considered predictive if, for example:

- ( R^2_{pred} > 0.5 )

- ( \mid r^20 - r'^20 \mid < 0.3 )

- ( 0.85 \leq k \leq 1.15 ) (or similar for ( k' ))

Protocol for Calculating Roy's rm² Metrics

- Prediction: Obtain the predicted activities for the test set (or LOO-predicted for the training set).

- Calculate Correlation Coefficients:

- Calculate ( r^2 ), the coefficient of determination for the regression between observed and predicted values with an intercept.

- Calculate ( r^2_0 ), the coefficient of determination for the regression through the origin.

- Compute rm² and Derived Metrics:

- Calculate ( r^2m = r^2 \times (1 - \sqrt{r^2 - r^20}) ) [35].

- Calculate ( r'^2m ) by swapping the axes (predicted vs. observed).

- Compute ( \Delta r^2m = \mid r^2m - r'^2m \mid ).

- Compute the average ( \overline{r^2m} = \frac{(r^2m + r'^2_m)}{2} ).

- Check Criteria: A model is deemed acceptable if ( \overline{r^2m} \geq 0.5 ) and ( \Delta r^2m < 0.2 ) for the test set [35].

Protocol for Calculating Concordance Correlation Coefficient

- Data: You have paired observed (( Y )) and predicted (( X )) values for the test set.

- Calculate Components:

- Calculate the means (( \bar{X}, \bar{Y} )) and variances (( s^2X, s^2Y )) of both sets.

- Calculate the covariance ( s{XY} ).

- Calculate Pearson's correlation coefficient (precision): ( \rho = \frac{s{XY}}{sX \cdot sY} ).

- Compute CCC:

Performance Comparison and Interpretation

The practical application of these metrics reveals their distinct strengths and sensitivities. A 2022 comparative study on 44 reported QSAR models highlighted that relying on a single metric like the coefficient of determination (( r^2 )) is insufficient to indicate model validity [2]. The study found instances where models with high ( r^2 ) values failed other stringent validation criteria.

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Model Validation Studies

| Context / Study | Key Finding Related to Validation Metrics |

|---|---|

| General QSAR Model Review (44 models) [2] | Identified models where ( r^2 > 0.6 ) but other metrics (( r^20 ), ( r'^20 )) showed poor performance, demonstrating the weakness of using ( r^2 ) alone. |

| 3D-QSAR on Thioquinazolinone (Anti-breast cancer) [15] | A validated CoMSIA model was reported with strong ( Q^2 ), ( R^2 ), and ( R^2_{pred} ) values, using the Golbraikh-Tropsha framework to confirm predictive power. |

| 3D-QSAR on Oxadiazole (Anti-Alzheimer agents) [39] | The built CoMFA and CoMSIA models were validated by external validation and applicability domain analysis, showing significant ( R^2_{pred} ) values. |

Strengths and Weaknesses

- Golbraikh-Tropsha: Its main strength is its comprehensiveness, as it evaluates multiple aspects of the regression. A potential weakness is that some of its criteria can be overly strict and may be sensitive to the specific software implementation for regression through the origin [34] [2].

- Roy's rm²: The key strength is its stringency and the insight from ( \Delta r^2m ), which detects asymmetry in predictions. It is less dependent on the training set mean than ( R^2{pred} ), avoiding overestimation for data with a wide response range [33] [35]. A minor complexity is the need for multiple calculations (( r^2m ) and ( r'^2m )).

- Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC): Its primary strength is providing a single, unified measure that incorporates both precision and accuracy. This makes it intuitive and highly useful for comparing models. Its interpretation is similar to other correlation coefficients, making it accessible [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Resources for QSAR Model Development and Validation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Training & Test Sets | Data | The foundational split of data for model building and unbiased evaluation of predictive power [32]. |

| Plots (Y-obs vs. Y-pred) | Diagnostic | The scatter plot for visual assessment of fit and to check deviation from the line of identity. |

| Statistical Software (R, Python, SPSS) | Software | Platforms for calculating validation metrics (e.g., CCC, ( r^2 ), slopes). Note: Algorithms for RTO may differ between tools [34]. |

| Validation Scripts | Algorithm | Custom or published scripts to compute specific stringent metrics like ( r^2m ) and ( \Delta r^2m ) or CCC. |

| Applicability Domain | Framework | Defines the chemical space where the model's predictions are reliable, an essential complement to validation [39]. |

The external validation of 3D-QSAR models for anticancer research is a multi-faceted process that cannot rely on a single statistic. The Golbraikh-Tropsha criteria, Roy's rm² metrics, and Concordance Correlation Coefficient each provide unique and critical insights into a model's predictive reliability. While Golbraikh-Tropsha offers a multi-pronged hypothesis test, rm² metrics provide a stringent, penalizing check, and the CCC elegantly combines precision and accuracy into one value. Current research indicates that the most robust strategy is a consensus approach. A model that simultaneously satisfies the key conditions of the Golbraikh-Tropsha criteria, demonstrates a high ( \overline{r^2m} ) with a low ( \Delta r^2m ), and achieves a CCC value in the "substantial" to "almost perfect" range can be considered highly predictive and reliable for prospective anticancer drug design.

In anticancer drug discovery, computational methods like three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling are pivotal for reducing the cost and time of development. These models help elucidate the relationship between a molecule's spatial features and its biological activity, guiding the optimization of novel drug candidates [40]. The predictive power of any 3D-QSAR model, however, is not determined by its fit to the data used to build it, but by its ability to accurately forecast the activity of new, unseen compounds. This process is known as external validation, and it is the most critical step for establishing a model's robustness and utility in a real-world research setting [6]. This case study examines a successful implementation of external validation for a Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) model developed for a series of novel pteridinone derivatives as inhibitors of Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1), a promising broad-spectrum anticancer target [40] [41].

Background on PLK1 and Pteridinone Derivatives

Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is a serine-threonine kinase that plays an essential role in cell proliferation, regulating processes such as centrosome maturation and bipolar spindle formation [40]. Its overexpression has been documented in numerous cancer types, including prostate, lung, and colon cancers, making it a attractive target for therapeutic intervention [40] [41]. A series of novel pteridinone derivatives were synthesized and evaluated for their biological activity (IC~50~) against PLK1, providing an excellent dataset for molecular modeling studies [40]. The core objective of the research was to build reliable 3D-QSAR models that could inform the design of more potent PLK1 inhibitors for the treatment of cancers like prostate cancer [40].

Methodology for Model Development and Validation

Data Set Preparation and Molecular Alignment

The study utilized a data set of 28 pteridinone derivatives with known experimental half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC~50~) values [40]. The biological activity was converted to pIC~50~ (pIC~50~ = -log IC~50~) for use as the dependent variable in modeling. To ensure a rigorous validation, the dataset was divided into a training set (22 compounds, 80%) for model construction and a test set (6 compounds, 20%) to evaluate the model's predictive capability [40].

Molecular alignment is a sensitive and critical step in 3D-QSAR model generation. In this study, a rigid distill alignment was performed using SYBYL-X 2.1 software. The most active compound was often used as a template, and all other molecules were aligned to it based on their structural similarities to ensure a meaningful comparison of their molecular fields [40] [42].

CoMSIA Model Generation

The CoMSIA methodology was employed to relate the biological activities of the pteridinone derivatives to various molecular field descriptors [40]. Unlike Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), which only calculates steric and electrostatic fields, CoMSIA can assess additional fields such as hydrophobic and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor characteristics, providing a more nuanced view of ligand-receptor interactions [6].

The study established several CoMSIA models using different field combinations. One of the most successful was the CoMSIA/SEAH model, which incorporated Steric, Electrostatic, Acceptor, and Hydrophobic fields [40]. The descriptor fields were computed within a 3D grid spacing of 2 Å, using a probe atom with a charge of +1. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) algorithm was then used to build a linear correlation between these molecular fields and the pIC~50~ values [40].

Validation Protocols

A multi-tiered validation strategy was employed to ensure the model's reliability:

- Internal Validation: The model was first subjected to leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation. This process involves systematically removing one compound from the training set, rebuilding the model with the remaining compounds, and predicting the activity of the omitted compound. The result of this is the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²). A Q² > 0.5 is generally considered indicative of a model with good internal predictive ability [40].

- Internal Non-Cross-Validation: After determining the optimal number of components (ONC) from the LOO validation, a conventional regression was performed on the entire training set to calculate the non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (R²) and the standard error of estimation (SEE). A high R² and low SEE suggest a good fit to the training data [40].

- External Validation: This is the most crucial step for assessing predictive power. The final model, built from the entire training set, was used to predict the activities of the six compounds in the external test set. The predictive correlation coefficient (R²~pred~) was then calculated based on these predictions. An R²~pred~ > 0.6 is a key benchmark for a model to be considered successful and reliable for predictive purposes [40].

Table 1: Key Statistical Parameters for the Developed 3D-QSAR Models [40]

| Model | Field Combination | Q² | R² | SEE | R²~pred~ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | Steric, Electrostatic | 0.67 | 0.992 | Not Specified | 0.683 |

| CoMSIA/SHE | Steric, Hydrophobic, Electrostatic | 0.69 | 0.974 | Not Specified | 0.758 |

| CoMSIA/SEAH | Steric, Electrostatic, Acceptor, Hydrophobic | 0.66 | 0.975 | Not Specified | 0.767 |

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for CoMSIA model development and validation, highlighting the critical step of external validation with a hold-out test set.

Results and Discussion

Success of External Validation

As shown in Table 1, the CoMSIA/SEAH model demonstrated excellent statistical characteristics. It achieved a high internal cross-validation value of Q² = 0.66 and a strong non-cross-validated correlation of R² = 0.975 [40]. Most importantly, the external validation yielded an R²~pred~ value of 0.767. This result surpasses the accepted threshold of 0.6 and confirms that the model possesses high predictive reliability for new pteridinone analogues [40]. The model's ability to accurately predict the activity of the six test compounds, which were not involved in model building, provides strong confidence for its use in virtual screening and lead optimization.

Contour Map Analysis and Structural Insights

The CoMSIA model provides more than just a numerical prediction; it offers visual guidance for molecular design through contour maps. These maps illustrate regions in 3D space where specific molecular properties (steric bulk, hydrophobicity, etc.) are favorably or unfavorably linked to biological activity [40].

For instance, the contour chart of the CoMSIA/SEAH model clearly demonstrated the relationships between the different molecular fields and inhibitory activities. Analyzing these maps allows a medicinal chemist to understand why certain substituents enhance activity. For example:

- A yellow contour near a substituent indicates that hydrophobic groups at that position are unfavorable for activity.

- A white contour suggests that electron-donating groups (electropositive) would be beneficial.

These insights directly guide the rational design of new compounds, such as suggesting the introduction of a bulky, hydrophobic group in a region with a favorable steric (green) contour to potentially enhance potency [40].

Corroboration with Molecular Docking and Dynamics

To reinforce the findings from the 3D-QSAR study, the researchers performed molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Docking studies identified key amino acid residues (R136, R57, Y133, L69, L82, and Y139) in the active site of PLK1 (PDB: 2RKU) that interact with the most active ligands [40].

Subsequently, MD simulations were run for 50 nanoseconds to observe the stability of the protein-ligand complexes over time. The results showed that the inhibitors remained stable within the PLK1 active site for the entire simulation period, validating the binding poses predicted by docking and providing atomic-level insight into the inhibitory mechanism [40]. This multi-faceted computational approach, where 3D-QSAR is supported by structural interaction studies, significantly strengthens the credibility of the results.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR and Validation [40] [42] [43]

| Research Reagent / Software | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| SYBYL-X 2.1.1 Software | Integrated software suite for molecular modeling, used for sketching, optimization, alignment, and CoMFA/CoMSIA model generation. |

| Tripos Force Field | Used for energy minimization of molecular structures to their most stable conformations prior to alignment and analysis. |

| Gasteiger-Hückel Charges | A method for calculating partial atomic charges, which are essential for computing electrostatic potential fields. |

| PLS (Partial Least Squares) Algorithm | The statistical method used to correlate the molecular field descriptors (independent variables) with biological activity (dependent variable). |

| AutoDock Tools / Vina | Molecular docking software used to predict the binding orientation and affinity of ligands within the protein's active site. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS) | Software used to simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, assessing the stability of protein-ligand complexes. |

This case study exemplifies a rigorously validated 3D-QSAR model for pteridinone-based PLK1 inhibitors. The CoMSIA/SEAH model demonstrated high predictive accuracy, as confirmed by a strong external validation result (R²~pred~ = 0.767). The model's contour maps provide actionable insights for drug design, which were further corroborated by stable binding modes observed in molecular docking and dynamics simulations. This integrated computational workflow—from robust QSAR modeling and stringent external validation to structural interaction analysis—provides a reliable framework for accelerating the discovery of novel anticancer agents. The success of this validation protocol underscores its critical role in ensuring that computational models are not just statistically sound on paper but are truly predictive tools that can guide efficient drug discovery.

In modern anticancer drug discovery, the limitations of single-target therapies, often leading to drug resistance, have accelerated the development of multi-target agents [4] [44]. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a pivotal computational tool in this endeavor, enabling the rational design of potent therapeutic compounds [45]. However, the predictive power and reliability of any QSAR model are critically dependent on rigorous validation, particularly through external validation methods that assess its performance on compounds not used during model building [2].

This case study examines the application of comprehensive external validation to a 3D-QSAR model developed for a series of 2-Phenylindole derivatives, investigated as multi-target inhibitors against key cancer-related proteins: Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 2 (CDK2), Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), and Tubulin [4] [44]. We will evaluate the established validation protocols, analyze the model's predictive capability, and discuss its utility in designing novel anticancer candidates with improved binding affinities and favorable pharmacokinetic profiles.

Background and Significance

The Multi-Target Approach in Cancer Therapy

Cancer's complexity often renders single-target therapies ineffective long-term due to compensatory pathway activation in cancer cells [44]. Simultaneously targeting multiple critical proteins offers a promising strategy to enhance therapeutic outcomes and overcome resistance mechanisms [4] [46]. CDK2 regulates cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase; EGFR, a receptor tyrosine kinase, drives uncontrolled proliferation and survival; and Tubulin, essential for cell division, represents a classical antimitotic target [44]. Concurrent inhibition of these diverse pathways can potentially deliver more durable disease control.

The Essential Role of External Validation in QSAR