De Novo Drug Design for Oncology: AI-Driven Methods for Novel Cancer Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern de novo drug design methods and their transformative application in oncology.

De Novo Drug Design for Oncology: AI-Driven Methods for Novel Cancer Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern de novo drug design methods and their transformative application in oncology. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of generative AI, delves into specific methodological approaches for creating novel anti-cancer compounds, addresses key challenges in optimization and validation, and offers a comparative analysis of leading platforms and their clinical progress. The synthesis of current innovations and real-world case studies aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage these technologies for accelerating the discovery of next-generation cancer therapies.

The New Frontier: How AI is Redefining Oncology Drug Discovery

The development of novel oncology therapeutics is defined by a critical paradox: despite unprecedented understanding of cancer biology, the successful translation of this knowledge into new medicines remains hampered by persistently high attrition rates and the profound complexity of tumor heterogeneity. Traditional drug discovery approaches are increasingly insufficient to address these challenges, with approximately 90% of oncology drugs failing during clinical development [1]. This attrition imposes tremendous costs, both temporal and financial, with traditional drug development requiring 12-15 years and investments reaching $1-2.6 billion per approved therapy [2]. The convergence of these challenges has created an imperative for innovation, particularly in de novo drug design methods that can fundamentally reshape our approach to oncology therapeutic development.

Tumor heterogeneity manifests at multiple levels, encompassing genetic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental diversity both between patients (inter-tumoral) and within individual tumors (intra-tumoral) [1]. This heterogeneity drives differential treatment responses and facilitates the emergence of resistance through Darwinian selection pressures [3]. Under conventional discovery paradigms, this biological complexity translates to formidable obstacles in target identification, candidate optimization, and clinical trial design. The industry's response has been the rapid integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and novel preclinical models that collectively offer a path toward more predictive, efficient, and personalized oncology drug development [2] [4].

Application Note: AI-Driven De Novo Drug Design

Core Principles and Workflow

Artificial intelligence has emerged as a transformative force in de novo drug design, employing generative models to create novel molecular structures with optimized drug-like properties. These approaches leverage machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and reinforcement learning (RL) to explore chemical space with unprecedented breadth and efficiency [4] [1]. The fundamental paradigm shift involves transitioning from screening existing compound libraries to computationally generating novel chemical entities designed for specific therapeutic targets and pharmacological profiles.

Leading AI-driven drug discovery platforms have demonstrated remarkable efficiency gains, compressing early-stage discovery timelines from the typical 3-5 years to as little as 12-18 months [5]. For instance, Exscientia's platform has achieved clinical candidate selection while synthesizing only 136 compounds, compared to thousands typically required in traditional medicinal chemistry campaigns [5]. Similarly, Insilico Medicine advanced an idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug from target discovery to Phase I trials in just 18 months, showcasing the transformative potential of AI-accelerated workflows [1] [5].

Key Technological Approaches

Table 1: AI Techniques in De Novo Drug Design for Oncology

| AI Technique | Key Applications | Representative Algorithms | Impact on Oncology Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | De novo molecular design, scaffold hopping | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Generates novel chemical structures with optimized properties for difficult oncology targets (e.g., KRAS, PD-L1) |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) | Multi-parameter optimization, chemical space exploration | Deep Q-Learning, Actor-Critic Methods | Balances potency, selectivity, and ADMET properties through iterative design cycles |

| Graph Neural Networks | Molecular property prediction, binding affinity estimation | Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) | Models complex molecular interactions and predicts target engagement for cancer-relevant proteins |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | Target identification, literature mining | Transformer Models, BERT Variants | Extracts hidden relationships from biomedical literature and multi-omics data to identify novel oncology targets |

The application of these AI technologies has produced several clinical-stage candidates. Exscientia's DSP-1181, designed for obsessive-compulsive disorder, became the world's first AI-designed drug to enter Phase I trials, demonstrating the platform's generalizability [5]. In oncology specifically, Exscientia has advanced multiple candidates, including a CDK7 inhibitor (GTAEXS-617) for solid tumors and an LSD1 inhibitor (EXS-74539) [5]. Insilico Medicine has applied its generative chemistry platform to identify novel inhibitors for targets relevant to tumor immune evasion, such as QPCTL [1]. These examples underscore how AI-driven de novo design can address oncology's unique challenges, particularly for targets that have proven difficult to drug through conventional approaches.

Application Note: Advanced Preclinical Models for Addressing Tumor Heterogeneity

Integrated Model Systems

The predictive validity of oncology drug development depends critically on preclinical models that faithfully recapitulate tumor heterogeneity and microenvironmental complexity. Traditional 2D cell cultures have significant limitations in capturing this complexity, driving the adoption of more physiologically relevant systems. An integrated approach leveraging multiple model types provides complementary insights throughout the drug discovery pipeline [6].

Table 2: Advanced Preclinical Models in Oncology Drug Discovery

| Model Type | Key Characteristics | Applications in Oncology | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Organoids | 3D structures grown from patient tumor samples, preserve histopathology | High-throughput drug screening, biomarker identification, personalized therapy testing | Maintains patient-specific genetic and phenotypic features; more predictive than 2D cultures | Limited tumor microenvironment representation; technical complexity in establishment |

| Patient-Derived Xenografts | Patient tumor tissue implanted in immunodeficient mice | Biomarker discovery, clinical stratification, drug combination strategies | Preserves tumor architecture and heterogeneity; considered "gold standard" for preclinical studies | Time-consuming, expensive, limited throughput; ethical concerns regarding animal use |

| Organ-on-Chip | Microfluidic devices with human cells, simulating tissue-level complexity | ADME profiling, tumor-immune interactions, toxicity assessment | Dynamic system capturing fluid flow and mechanical forces; human-relevant biology | Technically challenging; not yet standardized for regulatory submissions |

| 3D Bioprinted Tumors | Layer-by-layer deposition of cells and biomaterials to create tumor constructs | Studies of tumor invasion, drug penetration, microenvironmental interactions | Precise control over spatial organization of multiple cell types; customizable complexity | Limited maturity; requires specialized equipment and expertise |

The FDA's evolving stance on New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), including through the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, has accelerated the adoption of these human-relevant models [7]. By 2022, NAM-based assays accounted for approximately 30% of oncology-related safety submissions to the FDA, with organ-on-chip models projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 20% through 2030 [7].

Protocol: Integrated Preclinical Screening Workflow for Addressing Tumor Heterogeneity

Objective: To establish a standardized, multi-stage screening protocol that leverages complementary preclinical models for comprehensive evaluation of novel oncology therapeutics against tumor heterogeneity.

Materials and Equipment:

- Cryopreserved patient-derived tumor samples

- Organoid culture media and extracellular matrix

- Immunodeficient mice (NSG, NOG, or similar)

- Automated cell culture systems (e.g., Hamilton, Sartorius)

- High-content imaging system

- Microsampling equipment (capable of collecting 50μL blood samples)

- Liquid handling robotics

- AI-powered image analysis software

Procedure:

Step 1: Primary Screening in PDX-Derived Cell Lines

- Establish 2D cultures from dissociated PDX tumors, preserving patient-derived genetic heterogeneity

- Conduct high-throughput cytotoxicity screening against 500+ genomically diverse cancer cell lines

- Perform initial biomarker hypothesis generation by correlating genetic mutations (e.g., EGFR, KRAS, BRAF status) with drug response

- Identify response and resistance patterns across diverse genetic backgrounds

- Select top 20% of compounds for further evaluation based on potency and therapeutic index

Step 2: Secondary Screening in Patient-Derived Organoids

- Establish patient-derived organoid biobanks from multiple cancer indications (e.g., colorectal, pancreatic, breast)

- Culture organoids in 3D extracellular matrix with organ-specific media formulations

- Treat organoids with candidate compounds identified from Step 1, using concentration-response curves (8-point, 1:3 dilution series)

- Assess efficacy using high-content imaging metrics (viability, apoptosis, proliferation)

- Perform multi-omics analysis (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) to refine biomarker signatures

- Evaluate mechanisms of resistance through single-cell RNA sequencing of treated organoids

Step 3: Tertiary Validation in PDX Models

- Implant patient-derived tumor fragments into immunodeficient mice (n=6-8 per group)

- Randomize mice when tumors reach 150-200mm³ and initiate treatment at human-equivalent doses

- Administer candidate compounds via appropriate route (oral, IV, IP) using clinically relevant schedules

- Monitor tumor growth by caliper measurements three times weekly

- Collect serial blood samples via microsampling (50μL) for PK/PD analysis

- Perform terminal harvest at study endpoint for immunohistochemistry and biomarker validation

- Analyze intra-tumoral heterogeneity through spatial transcriptomics of harvested tumors

Step 4: Data Integration and Biomarker Validation

- Correlate drug responses across all three model systems using concordance metrics

- Validate predictive biomarker hypotheses through orthogonal techniques (IHC, FISH, NGS)

- Utilize AI algorithms to integrate multi-omics data and identify complex biomarker signatures

- Generate a final biomarker report to guide clinical trial design and patient stratification strategies

Quality Control Considerations:

- Regularly authenticate cell lines and organoids via STR profiling

- Monitor mycoplasma contamination monthly

- Standardize passage number limits for biological models (organoids < passage 10)

- Implement automated media exchange systems to reduce variability in 3D cultures

- Use reference compounds with known activity as positive controls in all assays

This integrated protocol leverages the distinct advantages of each model system while compensating for their individual limitations, creating a comprehensive framework for evaluating novel therapeutics against the backdrop of tumor heterogeneity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Oncology Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Platform | Manufacturer/Provider | Function and Application | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crown Bioscience PDX Database | Crown Bioscience | World's largest collection of clinically relevant PDX models for efficacy studies | Extensive clinical annotation, including patient treatment history and multi-omics data |

| HuPrime PDX Collection | Crown Bioscience | Comprehensive PDX library covering multiple cancer types and rare subtypes | Well-characterized models with genomic and pharmacological profiling data |

| Organoid Biobanks | Various (Crown Bioscience, ATCC, academic institutions) | Biobanks of patient-derived organoids for high-throughput screening | Preserves genetic diversity of original tumors; enables personalized therapy testing |

| Curiox C-Free System | Curiox | Automated media exchange technology for cell culture workflows | Enhanced cell retention without detachment; improves reproducibility in 3D assays |

| Pluto Wash System | Curiox | Automated washing system for cell-based assays | Reduces background staining in flow cytometry; maintains cell viability |

| AI-Driven Design Platforms | Exscientia, Insilico Medicine, Schrödinger | De novo molecular design and optimization | Accelerates lead identification; optimizes multiple drug properties simultaneously |

| Multi-omics Integration Tools | Recursion, BenevolentAI | Integration of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic data for target identification | Identifies novel therapeutic targets; discovers biomarker signatures |

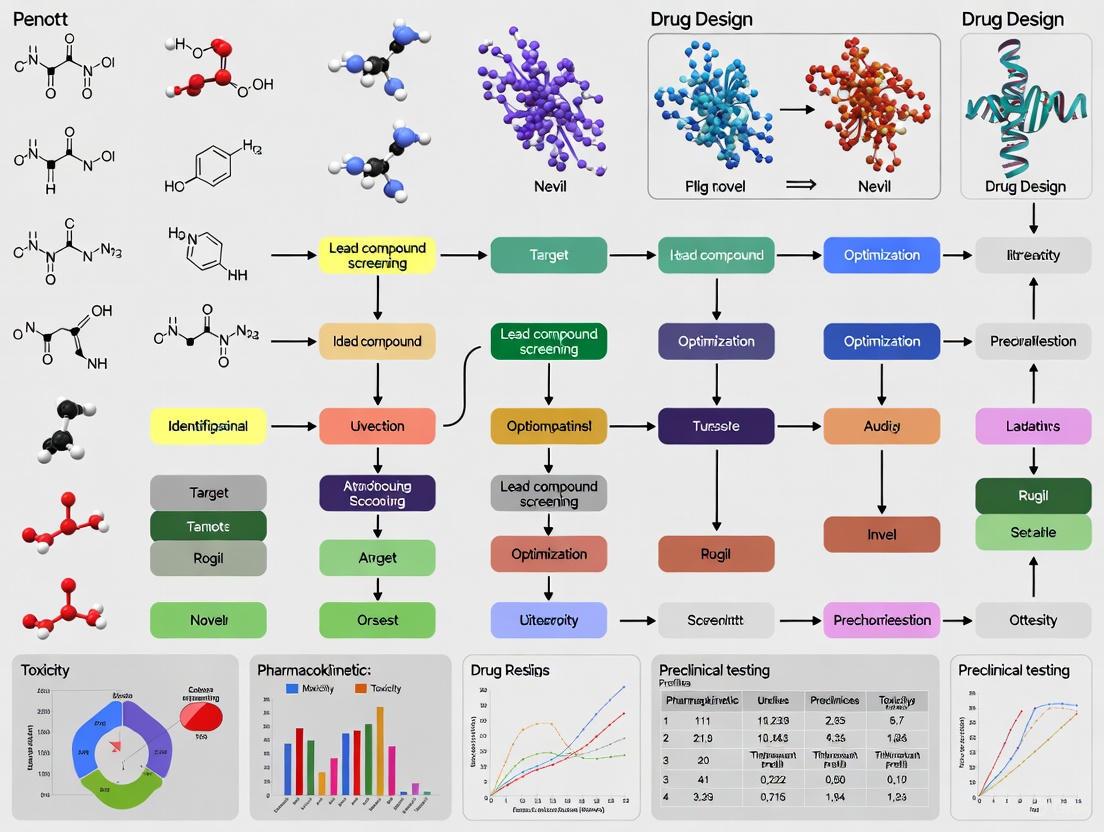

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

AI-Driven De Novo Drug Design Workflow

Integrated Preclinical Screening Strategy

Tumor Heterogeneity and Resistance Mechanisms

The imperative for innovation in oncology drug development has never been clearer. High attrition rates and tumor heterogeneity represent interconnected challenges that demand fundamentally new approaches to therapeutic discovery. The integration of AI-driven de novo design with advanced preclinical models creates a powerful framework for addressing these challenges, enabling more predictive candidate selection and personalized therapeutic strategies. As these technologies continue to mature and validate their clinical utility, they offer the promise of fundamentally transforming oncology drug development from a process of incremental optimization to one of rational design, ultimately delivering more effective therapies to cancer patients in significantly less time. The convergence of computational and biological innovations documented in these Application Notes provides researchers with both the conceptual framework and practical methodologies to advance this transformative agenda.

The development of novel oncology therapeutics is undergoing a paradigm shift, moving from a linear, high-attrition pipeline to an integrated, AI-accelerated discovery engine. This application note provides a comparative analysis of traditional versus artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced drug discovery pathways, focusing on de novo design methods for oncology. We present structured quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols for AI-driven methodologies, pathway visualizations, and essential research reagent solutions to guide researchers and drug development professionals in navigating this transformative landscape.

Cancer drug discovery has traditionally been a time-intensive and resource-heavy process, often requiring over a decade and exceeding $2.6 billion to bring a single drug to market, with approximately 90% of oncology candidates failing during clinical development [1] [8]. This high attrition rate, particularly in Phase II trials where nearly 70% of drugs fail due to insufficient efficacy, underscores the critical need for more predictive and efficient methodologies [8].

Artificial intelligence (AI) is now redefining this pipeline by leveraging machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and natural language processing (NLP) to integrate massive, multimodal datasets. These technologies accelerate target identification, optimize lead compounds, and personalize therapeutic approaches, potentially compressing discovery timelines from years to months and dramatically reducing costs [1] [4]. This document details both traditional and AI-accelerated pathways, providing practical protocols and resources for implementing these advanced approaches in oncology drug discovery.

Comparative Pipeline Analysis: Traditional vs. AI-Accelerated Pathways

Table 1: Stage-by-Stage Comparison of Traditional and AI-Accelerated Drug Discovery Pipelines

| Discovery Stage | Traditional Approach | AI-Accelerated Approach | Key AI Technologies | Reported Efficiency Gains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Literature review, genetic studies, biochemical assays [1] | Multi-omics data integration, network analysis [1] [9] | NLP, knowledge graphs, ML classifiers | Identification of novel targets in complex datasets [2] |

| Hit Identification | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) of physical libraries [9] | Virtual screening of billions of compounds [8] | Deep learning, QSAR models | Evaluation of ~10⁶⁰ chemical space in silico [8] |

| Lead Optimization | Iterative synthesis & testing (1000s of compounds) [10] | Generative molecular design & in silico ADMET prediction [1] [4] | Generative AI (VAE, GAN), Reinforcement Learning | 70% faster design cycles; 10x fewer compounds synthesized [5] |

| Preclinical Testing | Animal models (limited predictability) [10] | Patient-derived organoids/PDX models with AI-based biomarker prediction [6] | Predictive toxicology models, digital twins | Improved clinical translatability; reduced animal testing [6] |

| Clinical Trials | Manual patient recruitment, fixed design [1] | EHR mining for recruitment, predictive enrollment, synthetic control arms [1] [9] | Predictive analytics, NLP for EHR analysis | Accelerated recruitment; optimized trial design [1] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Traditional vs. AI-Accelerated Pipelines

| Performance Metric | Traditional Pipeline | AI-Accelerated Pipeline | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery to Phase I Timeline | ~5 years | 18-24 months (e.g., Insilico Medicine) [5] | Industry case studies [5] |

| Cost per Approved Drug | ~$2.6 Billion [8] | Potential for significant reduction (data still emerging) | Industry analysis [8] |

| Clinical Trial Success Rate | ~10% overall [8] | Aim to significantly improve (data still emerging) | Industry analysis [8] |

| Phase II Attrition Rate | ~70% failure [8] | Aim to reduce via better patient stratification [1] | Industry analysis [1] [8] |

| Compounds Synthesized for Lead Optimization | 1000s [10] | 100s (e.g., 136 for Exscientia's CDK7 program) [5] | Company reports [5] |

Experimental Protocols for AI-Accelerated Oncology Drug Discovery

Protocol: AI-Driven Target Identification Using Multi-Omics Data

Purpose: To identify novel, druggable oncology targets by integrating heterogeneous multi-omics data sources. Experimental Principles: This protocol uses AI to analyze genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and clinical data to uncover hidden patterns and novel therapeutic vulnerabilities that are difficult to detect with traditional methods [1] [9].

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Curation: Collect multi-omics data from public repositories (e.g., The Cancer Genome Atlas - TCGA) and proprietary sources. Manually curate literature and patent information to build a comprehensive knowledge base [1] [2].

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize and scale diverse data types. Impute missing values using advanced algorithms like autoencoders. Annotate data with unified biomedical ontologies.

- Network-Based Analysis: Construct biological networks using NLP-derived relationships and omics data. Apply graph ML algorithms to identify key network nodes (proteins/genes) central to oncogenic processes [9].

- Druggability Assessment: Utilize structure prediction tools (e.g., AlphaFold) to model protein structures and identify well-defined binding pockets for candidate targets [9]. Filter targets based on novelty, disease association, and chemical tractability.

- Experimental Validation: Prioritize top candidates for in vitro validation using CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screens in relevant cancer cell lines. Confirm essentiality via cell viability and functional assays [9].

Protocol: De Novo Molecular Design Using Generative AI

Purpose: To generate novel, synthetically accessible small molecules with optimized properties for a validated oncology target. Experimental Principles: Generative AI models learn from vast chemical libraries to design new molecular structures with desired pharmacological properties, balancing potency, selectivity, and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) characteristics [1] [4].

Procedure:

- Training Data Preparation: Assemble a curated dataset of known active and inactive compounds against the target. Annotate molecules with properties such as binding affinity, solubility, and metabolic stability.

- Model Selection and Training: Train a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) or Variational Autoencoder (VAE) on the prepared chemical dataset. The model learns the underlying probability distribution of "drug-like" molecules and their associated properties [4] [8].

- Conditional Generation: Define a target product profile (TPP) specifying desired properties (e.g., high binding affinity, low CYP inhibition). Use this TPP as a conditional input to the generative model to steer the generation of novel molecules meeting these criteria.

- Output Evaluation and Filtering: Generate a library of candidate molecules. Filter them using predictive QSAR and ADMET models to prioritize the most promising leads for synthesis [4].

- Iterative Optimization: Synthesize and test top candidates (e.g., 100-200 compounds) in biochemical and cellular assays. Feed the experimental results back into the AI model as a reinforcement learning signal for the next design cycle, creating a closed-loop optimization system [5].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

AI vs Traditional Drug Discovery Funnel

Generative AI de novo Design Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Oncology Discovery

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for AI-Driven Oncology Discovery

| Research Reagent / Platform | Type | Function in AI-Driven Discovery | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Organoids [6] | 3D Cell Culture | Faithfully recapitulates patient tumor biology for validating AI-predicted drug responses. | High-throughput screening of AI-generated compounds; biomarker hypothesis testing. |

| PDX Models [6] | In Vivo Model | Preserves tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment, serving as a gold-standard for in vivo validation of AI-designed candidates. | Final preclinical validation of efficacy and biomarker strategies before clinical trials. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Screening Libraries [9] | Functional Genomics Tool | Generates genetic dependency data for AI target identification algorithms. | Experimental validation of AI-predicted novel oncogenic vulnerabilities and synthetic lethality. |

| Multi-Omics Datasets (Genomics, Proteomics) [10] [9] | Data Resource | Provides the foundational data for training and validating AI models for target and biomarker discovery. | Input for network-based AI algorithms to identify novel targets and patient stratification biomarkers. |

| AI Drug Discovery Platforms (e.g., Exscientia, Insilico) [5] | Software Platform | Provides integrated environments for generative chemistry, virtual screening, and property prediction. | De novo design of small molecules against novel, AI-identified immuno-oncology targets. |

The integration of AI into the oncology drug discovery pipeline represents a fundamental shift from a slow, sequential, and high-failure process to an integrated, data-driven, and iterative engine. While the traditional pipeline provides a necessary foundation, the AI-accelerated pathway demonstrates compelling advantages in speed, efficiency, and predictive power, as quantified in this application note. The successful implementation of these approaches, supported by the detailed protocols and research tools outlined, holds the potential to reverse the trend of Eroom's Law and deliver more effective, personalized cancer therapies to patients in need.

Application Notes: Core AI Technologies in De Novo Drug Design

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing the paradigm of de novo drug design for novel oncology therapeutics. This shift moves the discovery process from a labor-intensive, serendipitous endeavor to a predictive, engineered science. Core AI technologies—Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), and Natural Language Processing (NLP)—are enabling the rapid generation and optimization of novel chemical entities with desired properties from scratch, significantly accelerating the path to effective cancer treatments [11] [12].

The following table summarizes the distinct roles and quantitative impact of these core technologies in oncology drug discovery.

Table 1: Core AI Technologies in Oncology Drug Discovery

| AI Technology | Key Function in De Novo Design | Specific Applications in Oncology | Reported Efficacy/Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | Identifies patterns in structure-activity relationships to predict compound properties [4]. | - Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling [13].- Predicting target binding affinity and ADMET properties [14] [4].- Virtual screening of compound libraries [14]. | Reduces costly late-stage attrition by predicting toxicity and efficacy early [12]. |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Generates novel molecular structures and predicts complex biological interactions using multi-layered neural networks [14] [1]. | - De novo molecule design using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) & Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [14] [4].- Prediction of protein-ligand binding structures (e.g., AlphaFold) [14].- Analysis of histopathology images for biomarker discovery [1]. | Novel drug candidate for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis designed in 18 months (vs. 3-6 years traditionally) [14] [1]. |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | Extracts and structures knowledge from unstructured biomedical text data [15] [16]. | - Mining electronic health records (EHRs) for patient recruitment in clinical trials [14] [15].- Identifying novel drug-target-disease relationships from scientific literature [1].- Named Entity Recognition (NER) for genes, compounds, and diseases [16]. | Identifies eligible patients for clinical trials from EHRs, addressing a major recruitment bottleneck [14] [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: AI-DrivenDe NovoDesign of a Small Molecule Immunomodulator

Objective: To design a novel, potent, and synthetically accessible small molecule inhibitor of the PD-L1 immune checkpoint pathway for cancer immunotherapy using an integrated AI workflow.

Background: Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis with small molecules is structurally challenging but offers advantages over biologics, such as oral bioavailability and better tumor tissue penetration [4]. AI accelerates the identification and optimization of such molecules.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Public Compound Databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) | Provide large-scale, labeled data on chemical structures and biological activities for model training [13]. | Source of known PD-L1 binders and non-binders for supervised learning. |

| Generative AI Model (e.g., VAE or GAN) | Learns the chemical space of drug-like molecules and generates novel molecular structures [14] [4]. | De novo generation of novel candidate PD-L1 inhibitors. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock Vina) | Computationally predicts how a small molecule binds to a protein target's binding site [17]. | Initial virtual screening and ranking of generated molecules based on predicted binding affinity to PD-L1. |

| ADMET Prediction Model | A supervised ML model (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) trained to predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity [13] [4]. | Filters generated molecules for desirable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles early in the pipeline. |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) Agent | An algorithm that optimizes a sequence of decisions; it is rewarded for generating molecules that meet multiple objectives [4]. | Optimizes the generated molecules iteratively for a combination of high binding affinity, good ADMET properties, and synthetic accessibility. |

Methodology

The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage, iterative workflow for the AI-driven de novo design protocol.

Workflow Diagram 1: AI-Driven De Novo Design Pipeline

Step 1: Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Action: Compile a dataset of known PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (active compounds) and decoys (inactive compounds) from public databases like ChEMBL and PubChem [13]. Annotate data with molecular descriptors (e.g., SMILES strings) and experimental binding affinities (e.g., IC50 values).

- Protocol: Standardize chemical structures, remove duplicates, and curate the data to ensure quality. Split the data into training (80%), validation (10%), and test sets (10%).

Step 2: Training the Generative Model

- Action: Train a Deep Learning generative model, such as a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) or a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), on the curated dataset of drug-like molecules [4].

- Protocol:

- Input: Represent molecules as SMILES strings or molecular graphs.

- Training: The VAE encoder learns to compress molecules into a latent vector space, and the decoder learns to reconstruct them. The model learns the fundamental rules of chemical structure and functionality.

- Validation: Assess the model's ability to generate valid, novel, and unique molecular structures not present in the training set.

Step 3: De Novo Molecule Generation

- Action: Use the trained generative model to create a large library (e.g., 1,000,000) of novel molecular structures.

- Protocol: Sample random vectors from the latent space of the VAE and decode them into new SMILES strings. Alternatively, use the generator from the GAN to produce new structures.

Step 4: Virtual Screening and Molecular Docking

- Action: Screen the generated library in silico to identify molecules with a high predicted affinity for the PD-L1 protein.

- Protocol:

- Pre-screening: Filter molecules based on drug-likeness rules (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five).

- Docking: Use software like AutoDock Vina to dock each candidate molecule into the binding site of a 3D crystal structure of PD-L1 [17].

- Scoring: Rank molecules based on their calculated binding free energy (docking score). Select the top 1,000-10,000 candidates for further analysis.

Step 5: In Silico ADMET Prediction

- Action: Employ supervised Machine Learning models to predict the pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles of the top-ranked candidates [13] [4].

- Protocol: Input the molecular structures of the candidates into pre-trained ML models that predict key properties such as:

- Absorption: Caco-2 permeability.

- Toxicity: hERG channel inhibition (cardiotoxicity).

- Metabolism: Stability in human liver microsomes. Filter out molecules with poor predicted ADMET properties.

Step 6: Multi-parameter Optimization via Reinforcement Learning (RL)

- Action: Iteratively refine the generated molecules to simultaneously optimize multiple properties [4].

- Protocol:

- Define Reward Function: The RL agent receives a positive reward for generating molecules with strong predicted binding affinity, favorable ADMET scores, and high synthetic accessibility.

- Optimization Loop: The agent explores the chemical space by making small modifications to molecular structures. It learns to maximize its cumulative reward over many iterations.

- Output: A focused set of 10-50 lead-like molecules that are optimized for both activity and developability.

Step 7: Experimental Validation

- Action: Synthesize the top AI-prioritized molecules and validate their activity and safety in in vitro and in vivo models.

- Protocol: Proceed to standard preclinical assays, including:

- In vitro binding assays to confirm PD-1/PD-L1 blockade.

- Cell-based assays to measure T-cell reactivation.

- In vivo efficacy studies in mouse cancer models.

- Preliminary toxicity studies.

Experimental Protocol: NLP-Enhanced Patient Stratification for Oncology Clinical Trials

Objective: To use Natural Language Processing (NLP) to efficiently identify and recruit eligible cancer patients for a clinical trial from Electronic Health Records (EHRs).

Background: Patient recruitment is a major bottleneck in clinical development, with about 80% of trials failing to enroll on time [1]. NLP can automate the screening of unstructured clinical notes to find eligible patients [15].

Methodology

The workflow for identifying eligible patients using NLP is outlined below.

Workflow Diagram 2: NLP-Driven Patient Stratification

Step 1: Define Eligibility Criteria

- Action: Translate the trial's formal eligibility criteria (e.g., "Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer," "EGFR wild-type," "No prior immunotherapy") into a structured query format [15].

Step 2: Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Action: Anonymize and aggregate unstructured clinical notes, pathology reports, and discharge summaries from the hospital's EHR system.

Step 3: NLP Text Processing and Named Entity Recognition (NER)

- Action: Process the text to identify and extract key clinical concepts.

- Protocol:

- Model Selection: Use a pre-trained biomedical NLP model like BioBERT or AdaBioBERT, which are specifically designed to recognize biomedical entities [16].

- Entity Extraction: The model scans the text and tags entities such as:

- Diseases: "metastatic adenocarcinoma"

- Genes & Biomarkers: "EGFR", "wild-type"

- Drugs: "pembrolizumab"

- Procedures: "lobectomy"

- Relationship Extraction: Advanced models can determine relationships between entities (e.g., that the "wild-type" status refers to the "EGFR" gene).

Step 4: Structured Data Output

- Action: Convert the extracted information into a structured database (e.g., a table) where each patient has standardized fields for cancer type, biomarkers, treatment history, etc.

Step 5: Apply Eligibility Logic

- Action: Run the structured query from Step 1 against the structured database from Step 4 to automatically flag patients who meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Step 6: Output and Review

- Action: Generate a list of potential candidates for the clinical trial team to review and contact, significantly accelerating the recruitment process [14] [15].

In the field of oncology therapeutics research, de novo drug design represents a paradigm shift, moving away from the incremental modification of existing compounds toward the computational generation of novel molecular entities from scratch [18]. This approach is critically dependent on a clear understanding of three foundational concepts: "hit," "lead," and "chemical space." The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) has revitalized de novo strategies, enabling researchers to navigate the vast chemical universe with unprecedented precision to discover and optimize new cancer treatments [18] [19]. This document delineates these core concepts and provides detailed experimental protocols framed within the context of oncology drug discovery.

Core Conceptual Definitions

The drug discovery pipeline is a multi-stage process that aims to transform a biological hypothesis into a clinically effective drug. The precise definition of key terms at each stage is vital for clear communication and effective strategy among research teams.

Chemical Space: This concept refers to the total ensemble of all possible organic molecules that are theoretically stable and synthesizable. Estimates suggest this space contains up to 10^60 drug-like molecules, a near-infinite landscape from which potential therapeutics can be drawn [19]. Traditional methods, such as high-throughput screening (HTS), explore only a minuscule fraction of this space. De novo design, powered by generative AI, allows researchers to systematically navigate and sample previously inaccessible regions of this chemical universe to identify novel compounds with desired properties from the outset [18] [19].

Hit: A "hit" is a molecule that demonstrates a desired pharmacological effect, such as binding to or modulating the activity of a validated oncology target (e.g., a specific kinase or protein implicated in cancer progression) during initial screening assays [18] [2]. Hits are the starting points in the drug discovery pipeline and are typically identified from large-scale screening of compound libraries or, increasingly, through generative AI models that design molecules tailored to a target [18]. A hit confirms the initial hypothesis that a molecule can interact with the target but usually requires significant optimization to become a viable drug candidate.

Lead: A "lead" compound is a refined version of a hit that has undergone preliminary optimization to improve its properties. The transition from hit to lead focuses on enhancing efficacy, specificity, and drug-like characteristics while minimizing early red flags for toxicity or poor pharmacokinetics [18] [2]. A lead compound possesses a more favorable profile, making it suitable for further extensive optimization and preclinical testing. AI algorithms are particularly valuable in this phase, as they can suggest optimal structural modifications to the core scaffold or its substituents to accelerate this development [18].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Hits and Leads in Oncology Drug Discovery

| Characteristic | Hit Compound | Lead Compound |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Origin | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) or AI-generated de novo design [18] [1] | Optimized derivative of a hit compound [18] |

| Biological Activity | Confirmed activity against the target in initial assays [2] | Improved potency and selectivity in more complex models [18] |

| Chemical Structure | May have suboptimal properties (e.g., potency, solubility) [18] | Chemically modified scaffold to enhance properties [18] |

| Role in Pipeline | Starting point for further investigation | Candidate for preclinical development [2] |

| Key Goal | Validate interaction with the therapeutic target | Establish a promising profile for a drug candidate [18] |

Quantitative Landscape of Chemical Space

The scale of chemical space underscores both the challenge and the opportunity in drug discovery. The following table quantifies the different scopes of molecular exploration, highlighting the transformative potential of de novo design.

Table 2: The Scale of Explored and Unexplored Chemical Space

| Category | Estimated Number of Molecules | Context and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Approved Drugs | ~10⁴ [19] | The small number of successfully marketed drugs highlights the high attrition rate in traditional discovery. |

| Large Combinatorial Libraries | Up to 10²⁰ [19] | Represents the largest experimentally accessible libraries, yet is still a tiny fraction of the total chemical space. |

| Total Drug-like Chemical Space | Up to 10⁶⁰ [19] | The vast theoretical universe of possible molecules, which de novo design aims to access computationally. |

Experimental Protocols for Hit Identification and Lead Optimization

The following protocols outline established methodologies for identifying hits and optimizing leads, with an emphasis on the integration of AI-driven de novo design strategies.

Protocol 1: AI-Driven De Novo Hit Identification

Objective: To generate novel hit compounds against a defined oncology target using generative AI models. Application: Initial phase of drug discovery for a new or undrugged target in oncology.

Materials and Reagents:

- Generative AI Software Platform (e.g., AIDDISON): Utilizes algorithms like variational autoencoders (VAEs) or generative adversarial networks (GANs) for molecular generation [1] [19].

- Target Structure: 3D crystal structure or high-quality predicted structure of the target protein (e.g., from Protein Data Bank).

- Training Data: Curated datasets of known active/inactive compounds and ADMET properties from public and proprietary sources [19].

Procedure:

- Target Preparation: Prepare the 3D structure of the oncology target by removing water molecules, adding hydrogen atoms, and defining the binding pocket.

- Model Configuration: Configure the generative AI model with multi-parameter optimization goals, including high binding affinity, favorable drug-likeness (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five), and synthetic accessibility [19].

- Molecular Generation: Execute the AI model to generate a library of novel molecular structures. For Structure-Based De Novo Design, the model uses docking scores to guide generation for optimal fit in the binding pocket [19].

- In Silico Hit Validation:

- Docking Analysis: Screen generated molecules using molecular docking simulations against the target to predict binding modes and affinities.

- ADMET Prediction: Employ machine learning models to predict key ADMET properties to filter out compounds with poor predicted pharmacokinetics or toxicity [2].

- Hit Selection: Select a diverse set of top-ranking compounds that meet the predefined criteria for biological activity and drug-like properties as putative hits for experimental validation.

Protocol 2: Hit-to-Lead Optimization via Scaffold Hopping and Decoratio n

Objective: To optimize a confirmed hit into a lead compound by improving its potency, selectivity, and overall drug-like profile. Application: Optimization of a confirmed hit with suboptimal properties.

Materials and Reagents:

- Confirmed Hit Compound: Chemically characterized and biologically tested molecule.

- Generative AI Platform with Scaffold-Hopping Capability: Software capable of suggesting novel core scaffolds while preserving bioactivity [18].

- Medicinal Chemistry Tools: Applications for visualizing and analyzing structure-activity relationships (SAR).

Procedure:

- SAR Analysis: Analyze existing data to identify key pharmacophoric features essential for the hit's biological activity.

- Scaffold Identification: Define the core molecular scaffold of the hit compound.

- AI-Guided Scaffold Hopping: Use the AI platform to generate novel, structurally distinct scaffolds that maintain the critical pharmacophoric features. This explores new intellectual property space and can improve properties [18] [19].

- Scaffold Decoration: For the original or a newly identified scaffold, use the AI model to suggest optimal substituents at various attachment points. This fine-tunes the molecule's interaction with the target and its physical properties [18].

- In Silico Lead Profiling: Rank the optimized compounds based on a weighted score of predicted potency, selectivity over anti-targets, and ADMET properties.

- Synthesis and Testing: Synthesize the top-ranked proposed leads and subject them to in vitro biological testing to confirm improved efficacy and selectivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key reagents, computational tools, and data resources essential for executing de novo design campaigns in oncology.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for De Novo Design

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Use Case in Oncology |

|---|---|---|

| Generative AI Software | Generates novel molecular structures optimized for specific parameters [1] [19]. | De novo design of inhibitors for specific oncology targets like kinases or mutant proteins. |

| Protein Structure Data | Provides the 3D atomic coordinates of a biological target. | Enables structure-based de novo design for targets such as EGFR or KRAS. |

| Curated Compound Libraries | Serves as training data for AI models and source for virtual screening. | Libraries enriched with known oncology drugs and tool compounds improve model predictions for cancer targets. |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | Computationally predicts absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity. | Early filtering of compounds with potential cardiotoxicity or poor blood-brain barrier penetration for CNS cancers. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a molecule to a target protein. | Validating the binding mode of AI-generated hits to the active site of an oncology target. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow of the integrated AI-driven de novo design process and a key signaling pathway often targeted in oncology.

AI De Novo Workflow

STK33 Signaling in Cancer

This application note details a standardized protocol for implementing an integrated, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven workflow for de novo drug design, with a specific focus on novel oncology therapeutics. The documented methodology accelerates the early discovery pipeline—from target identification and validation to the generation of novel, optimized molecular entities. By leveraging machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), this workflow significantly compresses discovery timelines, reduces reliance on costly empirical screening, and enhances the probability of clinical success for oncology drugs [1] [5]. The protocols below provide a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to adopt and adapt these technologies in their discovery campaigns.

Quantitative Foundations of AI in Drug Discovery

The adoption of AI-driven platforms is supported by compelling quantitative metrics that demonstrate increased efficiency and cost-effectiveness in the drug discovery process.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI-Driven vs. Traditional Drug Discovery in Oncology

| Metric | Traditional Discovery | AI-Driven Discovery | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Discovery Timeline | ~3-6 years | 12-18 months | Insilico Medicine developed a preclinical candidate for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in under 18 months [1]. |

| Compounds Synthesized | Thousands | Hundreds | Exscientia's CDK7 inhibitor program achieved a clinical candidate after synthesizing only 136 compounds [5]. |

| Design Cycle Efficiency | Baseline | ~70% faster | Exscientia reports AI-driven design cycles that are substantially faster and require 10x fewer synthesized compounds [5]. |

| Target Identification | Several months | Days to weeks | A Top Ten pharmaceutical company reported saving four months in the discovery phase, identifying the right research target faster [20]. |

| Cost Impact | High | Significant reduction | Life sciences researchers report AI is reducing operational costs; one project saved an estimated $42M by cutting research timelines by 90% [20]. |

Table 2: Key AI Platforms and Their Clinical-Stage Contributions (2025 Landscape)

| AI Platform / Company | Core AI Technology | Oncology-Relevant Clinical Candidate(s) | Development Stage (as of 2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia | Generative AI, Centaur Chemist | EXS-21546 (A2A antagonist for IO), GTAEXS-617 (CDK7 inhibitor) | Phase I/II trials; Pipeline prioritized post-Recursion acquisition [5]. |

| Insilico Medicine | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Novel inhibitors for QPCTL (tumor immune evasion) | Advancing into oncology pipelines [1]. |

| BenevolentAI | Knowledge Graphs, ML | Novel targets in Glioblastoma | Preclinical validation [1]. |

| Recursion | Phenotypic Screening, CNNs | Pipeline enhanced by integration with Exscientia's generative chemistry | Multiple programs in clinical trials [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AI-Driven Target Identification and Validation

Objective: To systematically identify and prioritize novel, druggable oncology targets from integrated multi-omics data.

Materials: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster or cloud instance (GPU-accelerated recommended); Access to a purpose-built scientific AI platform (e.g., Causaly) or in-house pipeline; Curated biological databases (e.g., The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), COSMIC, Human Protein Atlas, PubMed, ClinicalTrials.gov).

Procedure:

- Data Aggregation and Curation:

- Compile and pre-process multimodal data, including genomic (DNA sequencing), transcriptomic (RNA-seq), proteomic (mass spectrometry), and epigenomic datasets relevant to the cancer type of interest.

- Incorporate structured and unstructured data from scientific literature and clinical trial reports using Natural Language Processing (NLP) to build a comprehensive knowledge graph [20].

Target Hypothesis Generation:

- Utilize the AI platform to query the integrated data for genes or proteins associated with the desired disease phenotype (e.g., "cell proliferation in glioblastoma").

- Apply network analysis algorithms to identify key nodes (potential targets) within disease-associated biological pathways. BenevolentAI used this approach to predict novel targets in glioblastoma [1].

- Filter generated hypotheses based on genetic evidence (e.g., overexpression, mutation frequency), "druggability" predictions, and novelty relative to the competitive landscape.

Target Prioritization and Rationale:

- The platform should generate a ranked list of targets with fully traceable evidence for each association, linking back to source literature and data [20].

- Manually review the top candidates, focusing on the strength of causal versus correlative relationships, the potential for resistance mechanisms, and the feasibility of developing a high-throughput assay for downstream screening.

Validation Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 2: Generative AI forDe NovoMolecule Design with Active Learning

Objective: To generate novel, synthetically accessible, and target-specific small molecules using a generative AI model refined by iterative active learning cycles.

Materials: A dataset of known active and inactive molecules for the target of interest (e.g., ChEMBL, internal libraries); Cheminformatics software suite (e.g., RDKit); Molecular docking software (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide); High-performance computing resources for molecular dynamics simulations; Access to a generative AI framework (e.g., Variational Autoencoder (VAE)).

Procedure:

- Model Initialization and Training:

- Represent molecules in a machine-readable format, typically SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System). Tokenize and convert them into one-hot encoding vectors.

- Pre-train a VAE on a large, general molecular dataset (e.g., ZINC) to learn fundamental chemical rules and structures.

- Fine-tune the pre-trained VAE on a target-specific training set to bias the model towards relevant chemical space [21].

Nested Active Learning (AL) Cycles:

- Inner AL Cycle (Chemical Optimization):

- Generate: Sample the fine-tuned VAE to produce a set of novel molecular structures.

- Evaluate: Filter generated molecules using chemoinformatic oracles for drug-likeness (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five), synthetic accessibility (SA) score, and structural dissimilarity from the training set.

- Learn: Add molecules that pass the filters to a "temporal-specific set." Use this set to further fine-tune the VAE, reinforcing the generation of molecules with desired chemical properties. Repeat for a predefined number of iterations [21].

- Outer AL Cycle (Affinity Optimization):

- Evaluate: Subject the accumulated molecules from the inner cycles to molecular docking against the target's 3D structure, using the docking score as an affinity oracle.

- Learn: Transfer molecules with favorable docking scores to a "permanent-specific set." Use this high-quality set to fine-tune the VAE, directly steering the generative process towards high-affinity chemical space [21].

- Iterate between inner and outer AL cycles to progressively optimize for both chemical excellence and target engagement.

- Inner AL Cycle (Chemical Optimization):

Candidate Selection and In Silico Validation:

- Apply stringent filters to the final "permanent-specific set," selecting molecules with the best docking scores, SA, and novelty.

- Perform advanced molecular modeling, such as absolute binding free energy (ABFE) simulations or Monte Carlo methods (e.g., PELE), to refine the selection of the most promising candidates for synthesis and in vitro testing [21].

Active Learning Workflow Diagram:

Key Signaling Pathways in Oncology for AI-Driven Discovery

PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Pathway: A primary target for cancer immunotherapy. AI can design small molecules to disrupt the PD-1/PD-L1 protein-protein interaction, a strategy complementary to monoclonal antibodies [4]. These small molecules can inhibit PD-L1 dimerization or promote its degradation, potentially offering improved tissue penetration and oral bioavailability [4].

Tumor Microenvironment (TME) Metabolic Pathways: Targets like the IDO1 (Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1) enzyme, which catalyzes tryptophan degradation, creating an immunosuppressive TME. AI-driven models are used to design novel IDO1 inhibitors to reverse this suppression and reinvigorate T-cell responses [4].

Oncogenic Signaling (e.g., KRAS): Once considered "undruggable," KRAS is now a high-priority target. AI-generative models have been successfully tested to design novel inhibitors for KRAS, exploring scaffolds distinct from known ones, even in sparsely populated chemical spaces [21].

Pathway Diagram for PD-1/PD-L1 and IDO1:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for AI-Driven Oncology Drug Discovery

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function in the Workflow | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-omics Databases (e.g., TCGA) | Provides comprehensive molecular profiling data for human tumors. | Used as primary input data for AI-driven target identification and patient stratification [1] [10]. |

| Scientific AI Platform (e.g., Causaly, BenevolentAI) | Aggregates and structures public and private biomedical evidence using NLP and knowledge graphs. | Accelerates target identification and validation by uncovering causal biological relationships from vast literature [20]. |

| Generative AI Model (e.g., VAE, GAN) | Learns the structure of chemical space and generates novel molecular entities from scratch. | Core engine for de novo molecule design, as in the VAE-Active Learning workflow [21]. |

| Cheminformatics Suite (e.g., RDKit) | Provides computational tools for analyzing and manipulating chemical structures. | Used to calculate molecular properties, filter for drug-likeness, and assess synthetic accessibility [21]. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock Vina) | Predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule to a protein target. | Serves as the "affinity oracle" in the active learning cycle to prioritize molecules for synthesis [21]. |

| Patient-Derived Organoids / Ex Vivo Models | Provides biologically relevant, human-derived systems for testing compound efficacy. | Used to validate AI-designed compounds in a more translational context, as exemplified by Exscientia's acquisition of Allcyte [5]. |

Generative AI in Action: Core Methodologies for Designing Novel Cancer Drugs

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) has catalyzed a paradigm shift in computational chemistry and drug discovery, transitioning the field from reliance on manually engineered descriptors to the automated extraction of molecular features using deep learning [22]. Central to this transformation is the choice of molecular representation—the method of encoding chemical structures into a computationally tractable format [23]. The representation serves as the foundational layer upon which models learn, directly influencing their ability to predict molecular properties, generate novel compounds, and ultimately accelerate the discovery of new oncology therapeutics.

Within the context of de novo drug design for novel oncology research, selecting an appropriate molecular representation is crucial for creating effective AI-driven workflows. This document provides detailed Application Notes and Protocols for the three predominant molecular representations: SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System), SELFIES (SELF-referencing Embedded String), and Molecular Graphs. We summarize their comparative performance, provide protocols for their implementation, and visualize their roles in an integrated drug discovery pipeline.

String-Based Representations: SMILES and SELFIES

SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) is a linear notation system that represents a molecule's structure using ASCII strings, describing atoms, bonds, and ring structures [23] [24]. Despite its widespread use, SMILES has inherent limitations, including non-uniqueness (a single molecule can have multiple valid SMILES strings) and semantic fragility, where small string mutations can lead to invalid molecules [25] [26].

SELFIES (SELF-referencing Embedded String) is a more robust string-based representation developed to guarantee 100% syntactic and semantic validity [25] [27]. Every possible SELFIES string corresponds to a valid molecule, making it particularly advantageous for generative models in de novo design [26]. This robustness has enabled its successful application in platforms like DeLA-DrugSelf for multi-objective optimization of bioactive molecules [26].

Graph-Based Representations: Molecular Graphs

Molecular Graphs explicitly represent a molecule's structure as a mathematical graph ( G = (V, E) ), where atoms are nodes (V) and bonds are edges (E) [23]. This representation naturally captures the topological structure of molecules and can be enriched with node and edge features (e.g., atom type, formal charge, bond type) [23]. Molecular graphs are the backbone of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), which have demonstrated superior performance in many molecular property prediction tasks [22] [28]. Furthermore, graph-based crossover operators in genetic algorithms have shown high performance in generating diverse and plausible candidate molecules for drug discovery [29].

Quantitative Comparison of Representation Performance

The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison of SMILES-, SELFIES-, and Graph-based models on benchmark molecular generation tasks, as reported in recent literature. Performance is measured by the Wasserstein distance (lower is better) between property distributions of generated and test molecules, indicating how well the model learns the target distribution [24].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Molecular Representations on Complex Generation Tasks (Wasserstein Distance). Lower values indicate better performance.

| Representation | Model Type | Penalized LogP Task | Multimodal Distribution Task | Large Molecules Task | Validity (%) | Uniqueness (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES | RNN (SM-RNN) | 0.095 | 0.109 | 3.482 | >99% [24] | High [24] |

| SELFIES | RNN (SF-RNN) | 0.177 | 0.132 | 4.789 | ~100% [25] | High [24] |

| Molecular Graph | JTVAE | 0.536 | 0.245 | 18.16 | ~100% [24] | Moderate [24] |

| Molecular Graph | CGVAE | 1.000 | 0.426 | 22.69 | ~100% [24] | Moderate [24] |

| Hybrid (Multi-View) | MoL-MoE [28] | - | - | - | - | - |

Table 2: Qualitative Comparison of Molecular Representation Characteristics.

| Representation | Robustness | Interpretability | Ease of Generation | Information Captured |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES | Low: Sensitive to small changes [25] | Medium: Readable but non-unique | High: Simple string-based models | 2D molecular structure |

| SELFIES | High: Every string is valid [27] | Low: Less human-readable | High: Simple string-based models | 2D molecular structure |

| Molecular Graph | High: Inherently structured | High: Direct structural mapping | Medium: Requires complex GNN architectures | 2D/3D topology and features |

Application Notes forDe NovoDrug Design

Selecting a Representation for Oncology Drug Discovery

The choice of molecular representation should be guided by the specific goals and constraints of the oncology research project:

- For goal-directed optimization of known scaffolds, where exploring a constrained chemical space around a lead compound is key, SELFIES-based models are highly recommended. Their robustness ensures a high yield of valid molecules during optimization, as demonstrated in the DeLA-DrugSelf platform for CB2R ligand optimization [26].

- For exploring vast chemical spaces or generating entirely novel scaffolds, graph-based representations and genetic algorithms with cut-and-join crossover operators can produce highly diverse and synthesizable molecules [29]. The REvoLd system successfully utilized this approach to find candidate molecules with binding constants exceeding known binders for several target proteins [29].

- For multi-task property prediction or when data is limited, hybrid models that integrate multiple representations (SMILES, SELFIES, graphs) can leverage complementary strengths. The MoL-MoE framework demonstrated superior performance on various MoleculeNet benchmarks by dynamically weighting experts from different modalities [28].

- For structure-based design, where explicit 3D protein binding site information is required, 3D graph-based approaches are essential. The DRAGONFLY framework successfully integrated 3D protein binding site graphs with ligand information for the de novo design of potent PPARγ partial agonists, with crystal structures confirming the anticipated binding modes [30].

Integrated Workflow forDe NovoDesign

The following diagram illustrates a recommended protocol integrating multiple molecular representations within a de novo drug design cycle for oncology therapeutics.

Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a SELFIES-Based Generative Model for Scaffold Optimization

This protocol outlines the steps for using a SELFIES-based generative model, like DeLA-DrugSelf, to optimize a starting bioactive molecule for an oncology target [26].

Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential reagents and computational tools for Protocol 1.

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Query Molecule | The known bioactive molecule to be optimized. | e.g., a known inhibitor from corporate or public databases (ChEMBL). |

| SELFIES Encoder | Converts the molecular structure into a SELFIES string. | Open-source libraries: selfies (Python). |

| DeLA-DrugSelf Algorithm | The generative algorithm performing mutations (substitutions, insertions, deletions). | https://www.ba.ic.cnr.it/softwareic/delaself/ [26] |

| Fitness Function | Multi-objective function evaluating generated compounds (e.g., binding affinity, solubility, synthetic accessibility). | User-defined based on project goals; can use Pareto dominance. |

| Filtering Pipeline | Removes SELFIES-related collapse issues and applies drug-likeness rules (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five). | Integrated in DeLA-DrugSelf; can be customized with RDKit. |

Procedure

- Input Preparation: Select a starting query molecule with known activity against the oncology target of interest. Convert this molecule into its SELFIES representation using a SELFIES encoder.

- Algorithm Initialization: Configure the DeLA-DrugSelf algorithm with the initial SELFIES string and set the parameters for the genetic operations (mutation and crossover rates).

- Generation Loop: Execute the algorithm. In each iteration, DeLA-DrugSelf will generate new SELFIES strings by applying substitutions, insertions, and deletions to the parent string(s).

- Collapse Check and Validation: Decode all newly generated SELFIES strings to molecular structures. Explicitly check for and discard any compounds that encounter SELFIES-related collapse issues, retaining only collapse-free structures [26].

- Fitness Evaluation: Evaluate the validated compounds using the multi-objective fitness function. This function should incorporate predictions for key properties relevant to oncology drugs, such as target binding affinity (from a QSAR model), permeability, and metabolic stability.

- Selection and Iteration: Select the top-performing compounds based on the fitness score to serve as parents for the next generation. Repeat steps 3-5 for a predefined number of generations or until convergence criteria are met.

- Output: The final output is a library of optimized, novel compounds prioritized for further computational analysis and experimental validation.

Protocol 2: Structure-BasedDe NovoDesign with 3D Molecular Graphs (DRAGONFLY Framework)

This protocol describes the methodology for using the DRAGONFLY framework, which utilizes deep interactome learning on 3D graphs for structure-based molecular generation [30].

Research Reagent Solutions Table 4: Essential reagents and computational tools for Protocol 2.

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Target Protein Structure | 3D structure of the oncology target's binding site. | Protein Data Bank (PDB), homology model. |

| Drug-Target Interactome | A graph database of known ligand-target interactions for pre-training. | Curated from ChEMBL [30]. |

| Graph Transformer Neural Network (GTNN) | Encodes the 3D protein binding site graph into a latent representation. | Core component of DRAGONFLY [30]. |

| Chemical Language Model (LSTM) | Decodes the latent representation into a SMILES string of a novel ligand. | Core component of DRAGONFLY [30]. |

| QSAR Models | Predicts pIC50 values for generated molecules against the target. | Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) models with ECFP4, CATS, USRCAT descriptors [30]. |

| Synthesizability Filter | Assesses the feasibility of synthesizing the generated molecule. | Retrosynthetic Accessibility Score (RAScore) [30]. |

Procedure

- Data Curation and Interactome Construction: Compile a structure-based interactome comprising macromolecular targets with known 3D structures and their associated ligands (with binding affinity ≤ 200 nM). This serves as the pre-training dataset [30].

- Target Binding Site Representation: For the target protein of interest, represent the 3D binding site as a graph. Nodes represent key residues or pharmacophore features, and edges represent spatial relationships or interactions.

- Model Inference ("Zero-Shot" Generation): Input the target binding site graph into the pre-trained DRAGONFLY model. The model, which combines a GTNN and an LSTM, will process the graph and generate novel, drug-like molecules predicted to bind the site, without requiring application-specific fine-tuning [30].

- Computational Validation: Screen the generated molecules using the following steps: a. On-Target Bioactivity Prediction: Use pre-trained QSAR models (e.g., KRR with ECFP4 descriptors) to predict pIC50 values for the generated molecules against the target [30]. b. Synthesizability Assessment: Calculate the RAScore for each molecule to prioritize synthetically accessible compounds [30]. c. Selectivity and Off-Target Profiling: Use similar QSAR models to predict activity against related anti-targets (e.g., other nuclear receptors) to assess selectivity.

- Hit Prioritization and Experimental Validation: Chemically synthesize the top-ranking computational designs. Characterize them biophysically (e.g., Surface Plasmon Resonance) and biochemically to confirm binding and functional activity. Determine the crystal structure of the ligand-receptor complex to validate the predicted binding mode [30].

The workflow for this structure-based protocol is visualized below.

Application Notes

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) has transitioned from a proof-of-concept technology to a central pillar of modern de novo drug design, particularly for oncology therapeutics. Faced with rising research and development costs, multi-year timelines, and high attrition rates, the pharmaceutical industry is increasingly adopting AI-driven approaches to explore the vast theoretical chemical space (estimated at 10³³–10⁶³ drug-like molecules) efficiently [31]. Among the most impactful architectures are Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Transformers. These models enhance the "design–make–test–analyze" (DMTA) cycle by generating novel, optimized molecular structures with desired pharmacological properties, thereby accelerating the journey from target identification to clinical candidates [31] [4]. In oncology, this is critical for designing novel immunomodulators, kinase inhibitors, and therapies against drug-resistant cancers.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Generative Models

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for different generative model architectures as reported in recent literature and benchmarks.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Generative Model Architectures in De Novo Drug Design

| Model Architecture | Reported Validity (%) | Novelty (%) | Uniqueness (%) | Internal Diversity (intDiv2, %) | Key Application Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCF-VAE (Posterior Collapse Free VAE) [32] | 95.01 - 98.01 | 93.77 - 95.01 | 100 | 85.87 - 86.33 | Mitigates posterior collapse; high diversity and validity. |

| ScafVAE (Scaffold-Aware VAE) [33] | High (Model-specific) | High (Model-specific) | High (Model-specific) | High (Model-specific) | Multi-objective optimization; scaffold-based generation. |

| VGAN-DTI (VGAE + GAN for DTI) [34] | High (Model-specific) | High (Model-specific) | High (Model-specific) | N/R | High DTI prediction accuracy (96% accuracy, 94% F1-score). |

| Transformer-Based Models [31] | High | High | High | N/R | Scaffold hopping; molecular optimization via NLP-inspired edits. |

| GAN-Based Models (e.g., MolGAN) [31] [35] | Variable (Can suffer from mode collapse) | High | High | N/R | Generation of structurally diverse compounds. |

N/R: Not explicitly reported in the summarized search results. Metrics for VAE models like PCF-VAE can vary based on the diversity level (D) parameter and training setup [32].

Oncology-Focused Applications

Targeting Immune Checkpoints and the Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

Generative models are pivotal for designing small-molecule immunomodulators, which offer advantages over biologics like monoclonal antibodies, including oral bioavailability and better penetration into solid tumors [4].

- VAEs and GANs are used to generate inhibitors for intracellular targets like IDO1 (Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1), an enzyme that contributes to immunosuppression in the TME [4].

- Transformers and VAEs help design small molecules that disrupt the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction, a critical immune checkpoint, by promoting PD-L1 degradation or inhibiting its dimerization [4].

Overcoming Drug Resistance in Cancer Therapy

A key application is the de novo design of dual-target drug candidates to combat drug resistance through various mechanisms, such as synthetic lethality [33].

- Scaffold-aware VAEs (ScafVAE) have been successfully employed to generate molecules with strong binding affinity for two distinct target proteins involved in cancer resistance pathways. This is achieved while simultaneously optimizing other properties like drug-likeness (QED) and synthetic accessibility (SA) [33].

Scaffold Hopping and Lead Optimization

Generative models enable scaffold hopping—creating novel molecular cores that retain biological activity but offer improved properties.

- Transformers, trained on vast molecular corpora, can suggest chemist-like edits and novel scaffolds, escaping existing intellectual property or improving selectivity [31].

- VAEs with Bayesian optimization in their latent space can efficiently explore and optimize known scaffolds to improve potency, selectivity, and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) profiles [31] [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: De Novo Molecule Generation using a Scaffold-Aware VAE (ScafVAE)

Principle

This protocol outlines the procedure for generating novel, multi-objective drug candidates using ScafVAE, a graph-based variational autoencoder. Its bond scaffold-based generation approach expands the accessible chemical space while ensuring high chemical validity and synthetic accessibility, making it particularly suitable for designing oncology therapeutics [33].

Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ScafVAE Protocol

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dataset | Provides training data for the model. | ZINC, ChEMBL, QM9, or proprietary corporate libraries. |

| Protein Structures | For structure-based validation via docking. | From Protein Data Bank (PDB) or AlphaFold2 predictions. |

| Surrogate Model Datasets | Train property prediction models on the latent space. | ADMET, QED, SA scores, or experimental binding affinity data. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides computational resources for training and inference. | Equipped with multiple GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA A100/V100). |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Validates binding stability of generated molecules. | GROMACS, AMBER, or Desmond. |

| Docking Software | Computationally assesses binding affinity. | AutoDock Vina, Glide, or GOLD. |

Workflow Diagram

Diagram Title: ScafVAE Multi-Objective Molecule Generation Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preprocessing and Perplexity-Inspired Fragmentation

- Input: A large dataset of molecules (e.g., from ZINC or ChEMBL) in SMILES or graph format.

- Action: A pre-trained masked graph model (the "perplexity estimator") calculates a perplexity score for each bond in a molecule, which reflects the bond's predictability and uncertainty. Bonds with high perplexity are prioritized as potential breakpoints for fragmentation. This data-driven approach generates a comprehensive set of molecular fragments and "bond scaffolds" (scaffolds where atom types are unspecified) [33].

Model Training: Encoder and Decoder

- Encoder: A Graph Neural Network (GNN) combined with a Recurrent GNN (RGNN) encodes each molecular graph into a low-dimensional, continuous latent vector (z) following a Gaussian distribution. This maps the molecule into a probabilistic latent space [33].

- Decoder: The decoder network performs bond scaffold-based generation. It first assembles fragments into a complete bond scaffold by specifying connected bonds, then decorates the scaffold with specific atom types to produce a valid molecular structure. This process preserves the benefits of fragment-based approaches while accessing a wider chemical space [33].

- Training Objective: The model is trained to minimize the reconstruction loss (difference between original and reconstructed molecule) and the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, which regularizes the latent space [34] [33].

Surrogate Model Augmentation

- Input: The latent vectors (z) from the trained encoder.

- Action: Shallow Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs) are applied to the latent vectors, followed by task-specific machine learning modules, to predict molecular properties. The model is augmented using contrastive learning and molecular fingerprint reconstruction to improve prediction accuracy, especially for scarce experimental data (e.g., ADMET properties) [33].

Multi-Objective Optimization and Sampling

- Input: Desired property profiles (e.g., strong binding to two oncology targets, high QED, low toxicity).

- Action: Using the trained surrogate models, an optimization algorithm (e.g., Bayesian optimization) navigates the latent space to find vectors (z) that maximize the desired multi-objective function. This allows for the targeted generation of dual-target drug candidates or molecules with other optimized property combinations [33].

Generation and Validation

- Action: The optimized latent vectors are decoded by the ScafVAE decoder to generate novel molecular structures.

- Validation:

- Computational: Assess generated molecules with docking simulations, ADMET prediction tools, and synthetic accessibility (SA) scores [31] [33].

- Experimental: Promising candidates proceed to in vitro biochemical/biophysical assays and cell-based assays for functional validation in a relevant biological context [31].

Protocol 2: Predicting Drug-Target Interactions (DTI) using a Hybrid VAE-GAN Framework

Principle

This protocol describes a framework (VGAN-DTI) that combines VAEs, GANs, and MLPs to accurately predict drug-target interactions, a critical step in early-stage drug discovery for identifying potential oncology therapeutics [34].

Workflow Diagram

Diagram Title: Hybrid VAE-GAN Framework for DTI Prediction

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preparation