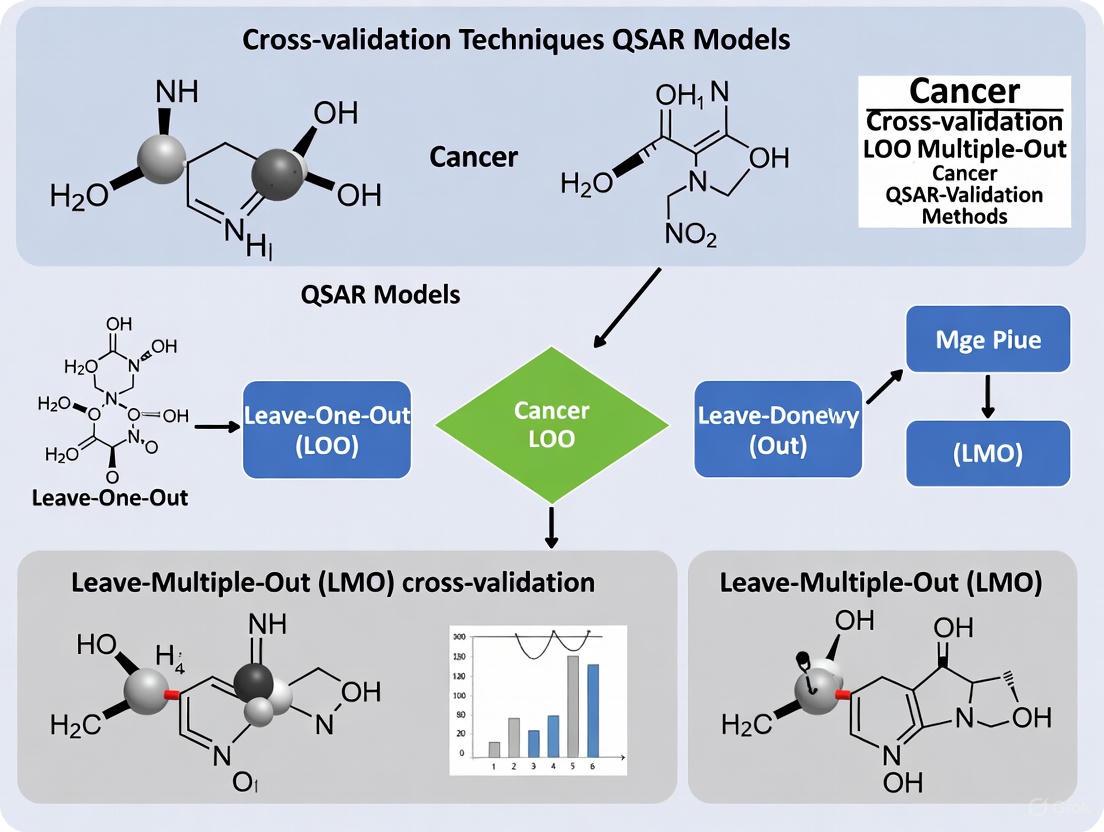

Cross-Validation in Cancer QSAR: Mastering LOO, LMO, and Advanced Validation for Predictive Drug Discovery Models

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cross-validation techniques for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models in cancer research.

Cross-Validation in Cancer QSAR: Mastering LOO, LMO, and Advanced Validation for Predictive Drug Discovery Models

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cross-validation techniques for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models in cancer research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles of Leave-One-Out (LOO) and Leave-Many-Out (LMO) validation, their practical implementation in anti-cancer model development, common pitfalls and optimization strategies, and advanced validation frameworks including double cross-validation and external validation. By synthesizing current methodologies and addressing critical challenges like model selection bias, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and predictive power of QSAR models in the discovery of novel oncology therapeutics.

Understanding QSAR and Cross-Validation Fundamentals in Cancer Research

The Role of QSAR in Modern Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, establishing statistically significant correlations between chemical structures and biological activities to predict compound behavior. In anti-cancer drug development, QSAR methodologies have evolved from traditional linear regression models to sophisticated machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) approaches capable of navigating complex chemical spaces to identify novel therapeutic candidates [1]. These models serve as powerful virtual screening tools that accelerate the identification of potential cancer therapeutics by prioritizing compounds with the highest likelihood of efficacy, thereby reducing reliance on costly and time-consuming experimental screening [2].

The predictive power of QSAR models in oncology hinges on rigorous validation techniques, particularly cross-validation procedures that ensure model robustness and reliability. As chemical databases expand exponentially, with modern libraries containing billions of compounds, proper validation becomes increasingly critical for distinguishing true therapeutic potential from false hits [3]. This review examines current QSAR methodologies, their validation frameworks, and practical applications in cancer drug discovery, with a specific focus on how cross-validation techniques enhance predictive accuracy in identifying novel oncology therapeutics.

Foundational QSAR Methodologies and Validation Frameworks

Molecular Descriptors and Model Architectures

QSAR models utilize quantitative descriptors to capture key aspects of molecular structure that influence biological activity. These descriptors span multiple dimensions of complexity:

- 1D descriptors: Elemental composition and molecular weight

- 2D descriptors: Structural fingerprints and topological indices derived from molecular graphs

- 3D descriptors: Geometrical and surface properties

- 4D descriptors: Incorporation of molecular dynamics and conformational ensembles [4]

In anti-cancer drug discovery, 2D descriptors have proven particularly valuable for large datasets with significant chemical diversity, as they eliminate conformational uncertainty while providing sufficient structural information for meaningful activity predictions [4]. Machine learning algorithms commonly employed in modern QSAR development include support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), gradient boosting, and deep neural networks (DNN), each offering distinct advantages for specific dataset characteristics and prediction tasks [4] [5].

Critical Validation Paradigms: From LOO to Nested Cross-Validation

Robust validation is essential for generating reliable QSAR models, with cross-validation techniques serving as the gold standard for assessing predictive performance:

- Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation: Iteratively removes one compound, builds the model on the remaining compounds, and predicts the omitted compound. This approach uses data efficiently but may produce higher variance in error estimates [6].

- Leave-Many-Out (LMO) Cross-Validation: Also known as k-fold cross-validation, this method removes a subset of compounds (typically 10-20%) during each iteration, offering a balance between bias and variance in error estimation [6].

- Nested (Double) Cross-Validation: Employs two layers of cross-validation, with an inner loop for model selection and parameter tuning and an outer loop for unbiased performance estimation. This approach provides the most reliable assessment of model performance on new data and effectively controls overfitting [4] [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Cross-Validation Techniques in QSAR Modeling

| Validation Method | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leave-One-Out (LOO) | Single compound omitted in each cycle | Maximizes training data usage | Can overestimate performance for small datasets |

| Leave-Many-Out (LMO) | Multiple compounds omitted in each cycle | More reliable error estimation | Requires larger datasets for stable results |

| Nested Cross-Validation | Separate loops for model selection & assessment | Unbiased performance estimation | Computationally intensive |

| Hold-Out Validation | Single split into training and test sets | Simple implementation | High variance based on split composition |

Traditional validation approaches have emphasized balanced accuracy as the primary performance metric. However, contemporary research demonstrates that for virtual screening of highly imbalanced chemical libraries (where inactive compounds vastly outnumber actives), positive predictive value (PPV) provides a more relevant metric for assessing model utility in early drug discovery [3]. Models with high PPV identify a greater proportion of true active compounds within the limited number of candidates that can be practically tested experimentally, making them particularly valuable for anti-cancer drug screening campaigns.

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies in Cancer Therapeutics

QSAR-Driven Discovery of PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Immunotherapy targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis has revolutionized cancer treatment, but existing therapeutics face limitations including high cost and drug resistance. A recent study applied multi-step structure-based virtual screening coupled with QSAR modeling to identify novel PD-L1 inhibitors from natural products [8].

Experimental Protocol:

- Receptor Preparation: The 3D crystal structure of human PD-L1 co-crystallized with a JQT inhibitor (PDB ID: 6R3K) was retrieved and prepared using protein preparation tools

- Library Curation: 32,552 natural compounds were obtained from the Natural Product Atlas database and prepared using LigPrep module

- Virtual Screening Workflow:

- Step 1: High-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) filtered compounds using ADME and drug-likeness criteria

- Step 2: Standard precision (SP) docking further refined candidate compounds

- Step 3: Extra precision (XP) screening identified top candidates

- Binding Affinity Assessment: Post-process binding free energy calculations using Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) method

- Validation: Explicit 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations assessed complex stability [8]

This workflow identified five natural compounds with substantial stability with PD-L1 through intermolecular interactions with essential residues. The calculated results indicated these natural compounds as putative potent PD-L1 inhibitors worthy of further development in cancer immunotherapy [8].

Nanoparticle QSAR Models for Tumor Delivery Optimization

Nanoparticles represent promising drug delivery systems in oncology, but achieving efficient tumor delivery remains challenging. Recent research has developed QSAR models to predict tissue distribution and tumor delivery efficiency of nanoparticles based on their physicochemical properties [5].

Experimental Protocol:

- Dataset Compilation: Data on nanoparticle physicochemical properties and in vivo distribution were obtained from the Nano-Tumor Database

- Model Development: Multiple ML algorithms were trained and validated:

- Linear regression

- Support vector machines

- Random forest

- Gradient boosting

- Deep neural networks (DNN)

- Model Validation: Rigorous cross-validation assessed prediction accuracy for delivery efficiency to tumors and major tissues

- Feature Importance Analysis: Identified core nanoparticle materials as critical determinants of distribution patterns [5]

The DNN model demonstrated superior performance, with determination coefficients (R²) for test datasets of 0.41, 0.42, 0.45, 0.79, 0.87, and 0.83 for delivery efficiency in tumor, heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, respectively [5]. This model successfully identified multiple nanoparticle formulations with enhanced tumor delivery efficiency and was converted to a user-friendly web dashboard to support nanomedicine design.

Diagram 1: Nested Cross-Validation Workflow for QSAR Model Development. This diagram illustrates the double-layered validation approach that provides unbiased performance estimation.

Comparative Performance Analysis of QSAR Approaches

Validation Metrics and Model Performance

The predictive accuracy of QSAR models varies significantly based on the biological endpoint, descriptor types, and modeling algorithms employed. The following table summarizes performance metrics for recently published QSAR models with relevance to anti-cancer drug discovery.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of QSAR Models in Drug Discovery Applications

| Application Domain | Model Type | Dataset Size | Validation Method | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibition | Multiple ML Algorithms | 300 models | Nested Cross-Validation | R² ≥ 0.70, CCC ≥ 0.85 | [4] |

| Nanoparticle Tumor Delivery | Deep Neural Network | Nano-Tumor Database | 5-Fold Cross-Validation | R² = 0.41 (tumor), 0.87 (lung) | [5] |

| Repeat Dose Toxicity Prediction | Random Forest | 3,592 chemicals | External Test Set | R² = 0.53, RMSE = 0.71 log10-mg/kg/day | [9] |

| 5-HT2B Receptor Binding | Binary Classification | 754 compounds | External Validation | 90% Experimental Hit Rate | [2] |

Impact of Data Set Characteristics on Model Performance

The size and composition of training datasets significantly influence QSAR model reliability. While traditional QSAR development often emphasized dataset balancing, contemporary research indicates that models trained on imbalanced datasets (reflecting the true distribution of active versus inactive compounds in chemical space) can achieve higher positive predictive value (PPV) – a critical metric for virtual screening applications [3]. In practical anti-cancer drug discovery, this translates to higher hit rates within the limited number of compounds that can be experimentally tested.

Comparative studies demonstrate that training on imbalanced datasets achieves hit rates at least 30% higher than using balanced datasets when screening ultra-large chemical libraries [3]. This paradigm shift acknowledges that modern virtual screening campaigns typically evaluate billions of compounds but can only experimentally validate a minute fraction (e.g., 128 compounds corresponding to a single 1536-well plate), making early enrichment of true actives more valuable than global classification accuracy.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for QSAR Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in Anti-Cancer QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ZINC15, ChEMBL, PubChem, Natural Product Atlas | Source of chemical structures and bioactivity data | Provides training data and virtual screening libraries [4] [8] |

| Descriptor Calculation | MOE, Dragon, PaDEL | Compute molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Generates quantitative features for model building [6] |

| Modeling Platforms | scikit-learn, WEKA, mlr3, Schrödinger | Machine learning algorithm implementation | Develops and validates QSAR models [4] |

| Validation Frameworks | Double Cross-Validation, Bootstrapping | Model performance assessment | Ensures model robustness and predictive capability [7] |

| Specialized Tools | ADMETLab 3.0, EPI Suite, VEGA | Predicts absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity | Assesses drug-like properties and safety profiles [10] |

Diagram 2: Integrated QSAR Workflow in Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery. This diagram shows the sequential process from data collection to experimental validation, with integrated ADMET assessment.

QSAR modeling continues to evolve as an indispensable tool in anti-cancer drug discovery, with advanced machine learning algorithms and rigorous validation frameworks enhancing predictive accuracy. The adoption of nested cross-validation techniques represents a significant advancement in model reliability, providing unbiased performance estimates that better reflect real-world screening utility. As chemical libraries expand into the billions of compounds, the emphasis on positive predictive value rather than balanced accuracy aligns model development with practical screening constraints, where only a minute fraction of predicted actives can undergo experimental validation.

Future directions in QSAR development for oncology applications will likely incorporate more sophisticated deep learning architectures, multi-task learning approaches that simultaneously model multiple cancer targets, and enhanced integration with structural biology information through hybrid structure-based and ligand-based methods. Furthermore, the growing availability of high-quality bioactivity data from public repositories will enable the development of increasingly accurate models capable of navigating the complex chemical space of potential anti-cancer therapeutics. As these computational approaches mature, their integration with experimental validation will continue to accelerate the discovery of novel cancer therapies while optimizing resource allocation in the drug development pipeline.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling is a fundamental computational approach in modern drug discovery, particularly in the development of anti-cancer agents. These models mathematically correlate the chemical structure of compounds with their biological activity, enabling the prediction of new therapeutic candidates against targets like breast cancer cell lines, tubulin, and dihydrofolate reductase [11] [12] [13]. The core assumption of QSAR is that structurally similar molecules exhibit similar biological properties, a principle that underpins the use of molecular descriptors to quantify chemical features and predict bioactivity [14] [13].

The predictive performance and reliability of any QSAR model are critically dependent on rigorous validation techniques. Without proper validation, models risk being overfitted to their training data, rendering them useless for predicting new, unseen compounds. Cross-validation stands as the primary statistical method for internally validating QSAR models and estimating their predictive capability. It operates by repeatedly partitioning the available dataset into training and validation subsets to simulate how the model will perform on external data [7]. Among cross-validation methods, Leave-One-Out (LOO) and Leave-Many-Out (LMO) are two pivotal approaches with distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations. Their strategic application is essential for developing robust QSAR models in cancer research, where accurate prediction of compound activity can significantly accelerate the identification of novel therapeutics [15] [11] [12].

Theoretical Foundations of LOO and LMO

Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation

Leave-One-Out cross-validation is an exhaustive method where each compound in the dataset takes a turn being the sole test subject. For a dataset containing N compounds, LOO involves N separate learning experiments. In each iteration, N-1 compounds are used to train the model, and the single remaining compound is used to test its predictive accuracy. The process repeats until every molecule has been the test object once, and the overall predictive performance is summarized by averaging the results from all N iterations [7]. The primary advantage of LOO is its efficient use of data; since each training set contains nearly all available compounds, the model is built on a near-complete representation of the chemical space. This characteristic makes LOO particularly valuable when working with small datasets, a common scenario in early-stage anticancer drug discovery where synthesizing and testing numerous compounds is costly and time-consuming [11]. However, LOO is computationally intensive for large datasets and can yield high-variance error estimates because each test set consists of only one compound, potentially making the results sensitive to small changes in the data.

Leave-Many-Out (LMO) Cross-Validation

Leave-Many-Out cross-validation, also known as k-fold cross-validation, takes a different approach by partitioning the dataset into k subsets (folds) of approximately equal size. Typically, k values of 5 or 10 are used, though this can vary based on dataset size and characteristics. In each iteration, k-1 folds are combined to form the training set, while the remaining single fold serves as the test set. This process repeats k times, with each fold getting exactly one turn as the test set. The final predictive performance metric is the average across all k iterations [7]. LMO's strength lies in its ability to provide a more stable and reliable estimate of prediction error, particularly for larger datasets. By testing the model on multiple compounds simultaneously, it better represents how the model will perform when faced with entirely new sets of compounds. Additionally, LMO is less computationally demanding than LOO for larger datasets. The main disadvantage of LMO is that each training set contains substantially fewer samples than the full dataset (e.g., 80-90% for k=5 or k=10), which might lead to models that don't fully capture the underlying chemical space, especially when the total number of available compounds is limited.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of LOO and LMO Cross-Validation

| Feature | Leave-One-Out (LOO) | Leave-Many-Out (LMO) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Iteratively removes one compound as test set, uses all others for training | Partitions data into k folds; uses k-1 folds for training, one fold for testing |

| Number of Iterations | Equal to number of compounds (N) | Typically 5 or 10 (user-defined) |

| Training Set Size | N-1 compounds | Approximately (k-1)/k * N compounds |

| Test Set Size | 1 compound | Approximately N/k compounds |

| Computational Demand | High for large N | Lower than LOO for large N |

| Variance of Error Estimate | Higher | Lower |

| Preferred Context | Small datasets | Medium to large datasets |

Comparative Analysis in Cancer QSAR Research

The choice between LOO and LMO cross-validation significantly impacts the validation outcomes of QSAR models designed for anticancer activity prediction. A review of recent literature reveals how both methods are applied in practice and highlights their performance characteristics across different research contexts.

In breast cancer research, a QSAR study on pyrimidine-coumarin-triazole conjugates against MCF-7 cell lines utilized LOO cross-validation, reporting a high Q²LOO value of 0.9495, indicating strong predictive capability [11]. Similarly, research on 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives as tubulin inhibitors for breast cancer therapy relied on LOO validation to confirm model robustness [12]. These applications demonstrate LOO's prevalence in studies with limited compound libraries, where maximizing training data is crucial.

For leukemia research, a QSAR study on 112 anticancer compounds tested against MOLT-4 and P388 leukemia cell lines implemented both LOO and external validation. The models achieved high Q²LOO values (0.881 and 0.856, respectively) alongside respectable external prediction accuracy (R²pred = 0.635 and 0.670) [15]. This dual-validation approach provides a more comprehensive assessment of model performance, with LOO offering internal consistency and external validation testing true generalizability.

The critical importance of proper validation parameterization was highlighted in a systematic study on double cross-validation, which emphasized that the parameters for the inner loop of double cross-validation mainly influence bias and variance of the resulting models [7]. This finding underscores why the choice between LOO and LMO directly impacts the reliability of the validated QSAR model, especially under model uncertainty when the optimal QSAR model isn't known a priori.

Table 2: Application of LOO and LMO in Published Cancer QSAR Studies

| Study Focus | Dataset Size | Validation Method | Reported Metric | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-breast cancer agents (MCF-7) [11] | 28 compounds | LOO | Q²LOO | 0.9495 |

| Anti-leukemia agents (MOLT-4) [15] | 112 compounds | LOO | Q²LOO | 0.881 |

| Anti-leukemia agents (P388) [15] | 112 compounds | LOO | Q²LOO | 0.856 |

| Tubulin inhibitors [12] | 32 compounds | LOO | Q²LOO | Not specified |

| c-Met inhibitors [16] | 48 compounds | LOO | Q²LOO | Not specified |

Experimental Protocols and Best Practices

Standard Implementation Protocol

Implementing proper cross-validation requires a systematic approach to ensure reliable and reproducible results. The following protocol outlines the key steps for both LOO and LMO cross-validation in cancer QSAR studies:

Dataset Preparation: Begin with a curated dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀ or pIC₅₀ values). For anticancer QSAR studies, this typically involves 20-100 compounds, depending on synthetic and testing capacity [11] [12] [16]. Ensure structural diversity within the dataset to adequately represent the chemical space under investigation.

Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing: Compute molecular descriptors using appropriate software such as PaDEL, DRAGON, or quantum chemical calculations with Gaussian [15] [12] [17]. Reduce descriptor dimensionality using methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or variable selection techniques to avoid overfitting [13].

Data Splitting:

- For LOO: No explicit splitting is needed as the algorithm automatically creates N partitions where each partition has one test compound and N-1 training compounds.

- For LMO: Randomly partition the dataset into k folds of approximately equal size, ensuring each fold represents the overall distribution of activity values. Stratified sampling is recommended to maintain similar activity distributions across folds.

Model Training and Validation:

- For each iteration, train the QSAR model (e.g., MLR, PLS, Random Forest) on the training set.

- Predict the activity of compounds in the validation set.

- Record the prediction error metrics (e.g., MSE, RMSE, R²) for each iteration.

Performance Assessment: Calculate the average performance metrics across all iterations. The most commonly reported metric is Q² (cross-validated R²), which indicates the model's predictive capability [15] [11].

External Validation (Recommended): For a more rigorous assessment, further validate the model using a completely external test set that wasn't involved in any cross-validation process [15] [7].

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflows for LOO and LMO cross-validation in the context of QSAR model development:

Cross-Validation Workflow: LOO vs. LMO

Decision Framework and Best Practices

Selecting the appropriate cross-validation method requires consideration of multiple factors. The following decision framework incorporates established best practices from the literature:

Dataset Size Considerations: Use LOO for small datasets (N < 50) commonly encountered in preliminary anticancer studies, as it maximizes training data usage. For medium to large datasets (N > 100), prefer LMO (typically 5-fold or 10-fold) for more stable error estimates and reduced computation time [15] [11] [7].

Model Stability Assessment: Implement multiple runs of LMO with different random seeds to assess model stability, as the specific partitioning can influence results. For LOO, this isn't necessary as the partitions are deterministic.

Comprehensive Validation Strategy: Employ double cross-validation (nested cross-validation) when performing both model selection and model assessment to obtain unbiased error estimates [7]. Always supplement internal cross-validation with external validation on a completely hold-out test set when data permits [15].

Reporting Standards: Clearly specify the cross-validation method (LOO or LMO with k value) and report all relevant metrics (Q², RMSE, etc.) in publications. For LMO, indicate the number of folds and whether the partitioning was stratified.

Applicability Domain Integration: Combine cross-validation with applicability domain assessment to identify when predictions for new compounds fall outside the model's reliable prediction space [15] [16].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for QSAR Cross-Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in QSAR/CV | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSARINS [11] [17] | Software | QSAR model development with comprehensive cross-validation features | 2D-QSAR analysis of pyrimidine-coumarin-triazole conjugates |

| PaDEL-Descriptor [15] | Software | Calculation of molecular descriptors for QSAR modeling | Descriptor calculation for anti-leukemia QSAR models |

| Gaussian 09/16 [12] [16] | Software | Quantum chemical calculations for electronic structure descriptors | Computing HOMO/LUMO energies for tubulin inhibitor models |

| R/Python with scikit-learn [17] [7] | Programming Libraries | Implementing custom cross-validation and machine learning algorithms | Building double cross-validation workflows for model uncertainty assessment |

| DRAGON [14] | Software | Calculation of a wide range of molecular descriptors (>3,300) | Molecular descriptor calculation for predictive toxicology models |

Leave-One-Out and Leave-Many-Out cross-validation represent two fundamental approaches with complementary strengths in validating QSAR models for cancer research. LOO's exhaustive nature makes it particularly valuable for small datasets typical in early-stage anticancer drug discovery, where maximizing training data is paramount. In contrast, LMO provides more stable error estimates for larger compound libraries and is computationally more efficient. The choice between these methods should be guided by dataset size, computational resources, and the required stability of the error estimate. As QSAR methodology continues to evolve with integration of artificial intelligence and multi-omics data [14] [17], proper cross-validation remains the bedrock of developing reliable models that can genuinely accelerate the discovery of novel anticancer therapeutics. A thoughtful validation strategy, potentially incorporating both LOO and LMO in a double cross-validation framework, provides the rigorous assessment necessary to advance promising compounds from in silico predictions to experimental validation.

In the field of oncology drug discovery, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models are indispensable computational tools that connect chemical structures to biological activity, dramatically accelerating the identification of potential therapeutic compounds [13]. However, the predictive power and real-world utility of these models are entirely dependent on the rigor of their validation. Without proper validation, models may suffer from overfitting and model selection bias, producing deceptively optimistic results that fail to generalize to new compounds [18]. This guide examines the critical validation methodologies that ensure oncology QSAR models generate reliable, clinically-relevant predictions for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Key Validation Concepts and Their Importance

The Fundamental Distinction: Internal vs. External Validation

Robust QSAR modeling requires both internal and external validation approaches, each serving distinct purposes in establishing model reliability:

Internal Validation assesses model stability using only the training data, typically through techniques like Leave-One-Out (LOO) and Leave-Many-Out (LMO) cross-validation [19]. These methods evaluate how well the model performs on different subsets of the training data, providing initial indicators of potential overfitting.

External Validation represents the gold standard for evaluating predictive power, where the model is tested on completely independent compounds that were not involved in model building or selection [18] [19]. This approach provides the most realistic estimate of how the model will perform in actual drug discovery applications when predicting activities of novel compounds.

The Perils of Inadequate Validation: Model Selection Bias and Overfitting

When validation is insufficient, several critical pitfalls can compromise model utility:

Model Selection Bias occurs when the same data is used for both model selection and validation, causing overly optimistic performance estimates [18]. This bias arises because suboptimal models may appear superior by chance when their errors are underestimated on specific data splits.

Overfitting happens when models become excessively complex, adapting to noise in the training data rather than capturing the underlying structure-activity relationship [18]. Such models demonstrate excellent performance on training compounds but fail dramatically when applied to new chemical entities.

Cross-Validation Techniques: Methodologies and Protocols

Core Cross-Validation Protocols

Table 1: Comparison of Key Cross-Validation Techniques in Oncology QSAR

| Technique | Key Methodology | Primary Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leave-One-Out (LOO) | Iteratively removes one compound, builds model on remaining n-1 compounds, and predicts the omitted compound [19] | Internal validation for small datasets | Maximizes training data usage; Low computational cost for small n | High variance in error estimate; Can overestimate predictive ability |

| Leave-Many-Out (LMO) | Removes a subset of compounds (typically 20-30%) repeatedly, building models on reduced training sets [19] | Internal validation for datasets of various sizes | More reliable error estimate than LOO; Better assessment of model stability | Requires larger datasets; Higher computational cost |

| Double (Nested) Cross-Validation | Features external loop for model assessment and internal loop for model selection [18] | Both model selection and error estimation for final assessment | Provides nearly unbiased performance estimates; Uses data efficiently | Complex implementation; Computationally intensive |

Advanced Validation: Double Cross-Validation Methodology

For the most reliable validation, double cross-validation (also called nested cross-validation) offers a sophisticated approach that addresses model selection bias:

Workflow Overview:

Experimental Protocol:

- Outer Loop Configuration: Partition the entire dataset into k-folds (typically 5-10), reserving one fold as the test set and remaining folds as the training set [18]

- Inner Loop Execution: On the training set, perform additional cross-validation to optimize model parameters and select the best-performing configuration [18]

- Model Assessment: Apply the selected model to the held-out test set from the outer loop to obtain unbiased performance estimates [18]

- Iteration and Averaging: Repeat the process across all outer loop partitions and average the results for stable performance metrics [18]

Compared to single validation approaches, double cross-validation provides more realistic performance estimates and should be preferred over single test set validation [18].

Quantitative Validation Metrics and Benchmarking

Essential Statistical Parameters for QSAR Validation

Table 2: Key Validation Metrics and Their Interpretation in Oncology QSAR

| Validation Metric | Acceptance Threshold | Interpretation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² (Coefficient of Determination) | > 0.6 [20] | Goodness of fit for training set | QSAR model for photodynamic therapy showed R² = 0.87 [20] |

| Q² (LOO Cross-Validated R²) | > 0.5 [20] | Internal predictive ability | Photodynamic therapy model achieved Q² = 0.71 [20] |

| R²pred (External Validation R²) | > 0.5 [20] [21] | True predictive power for new compounds | CoMSIA model for breast cancer inhibitors showed strong external prediction [21] |

| RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) | Lower values preferred | Average prediction error | Used in 3D-QSAR studies of thioquinazolinone derivatives [21] |

Performance Benchmarks from Oncology QSAR Studies

Recent studies demonstrate how proper validation separates reliable from unreliable models:

- Photodynamic Therapy Application: A porphyrin-based QSAR model achieved excellent internal validation (R² = 0.87, Q² = 0.71) and respectable external predictive ability (R²pred = 0.52) [20]

- Anti-Breast Cancer Models: A CoMSIA model for thioquinazolinone derivatives exhibited significant external prediction performance, confirming the value of rigorous validation [21]

- Multi-Model Analysis: Examination of 44 published QSAR models revealed that relying solely on R² cannot adequately indicate model validity, emphasizing the need for multiple validation metrics [19]

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRAGON Software [22] | Descriptor Calculation | Computes molecular descriptors (0D-2D) | Generates structural parameters for model building and validation |

| QSARINS [22] | Modeling Software | Develops MLR models with validation features | Facilitates variable selection and model validation processes |

| Cross-Validation Algorithms [18] | Statistical Method | Data splitting and resampling | Implements LOO, LMO, and double cross-validation protocols |

| Statistical Metrics Package [19] | Validation Metrics | Calculates R², Q², R²pred, etc. | Quantifies model performance and predictive power |

Implementation Guidelines and Best Practices

Recommended Validation Workflow

For comprehensive QSAR validation in oncology applications, researchers should implement this integrated approach:

Data Preparation Phase:

- Curate high-quality, diverse compound sets with reliable activity measurements

- Apply appropriate division algorithms to create representative training and test sets

Internal Validation Stage:

- Implement LOO cross-validation for initial assessment of model stability

- Conduct LMO cross-validation with multiple data splits (e.g., 5-fold, 10-fold)

- Calculate Q² and internal performance metrics

External Validation Stage:

- Completely hold out the test set during model building and parameter optimization

- Evaluate the final model on the external test set to calculate R²pred

- Assess predictive performance using multiple statistical measures

Advanced Validation (When Feasible):

- Implement double cross-validation to obtain nearly unbiased error estimates

- Compare performance across different validation approaches

- Conduct applicability domain analysis to define model boundaries

Interpretation of Validation Results

Proper interpretation of validation outcomes is crucial for model acceptance:

- Models meeting all thresholds (R² > 0.6, Q² > 0.5, R²pred > 0.5) can be considered predictively reliable for the defined chemical space [20]

- Models with strong internal but weak external validation likely suffer from overfitting and require simplification or better applicability domain definition [18]

- Consistently poor performance across validation methods indicates fundamental issues with descriptor selection or the underlying structure-activity hypothesis

Robust validation is not merely a statistical formality but the fundamental determinant of real-world predictive power in oncology QSAR models. Through the systematic application of cross-validation techniques, particularly LOO, LMO, and double cross-validation, researchers can develop models that genuinely accelerate oncology drug discovery rather than producing misleading results. The integration of both internal and external validation, coupled with appropriate performance metrics, provides the comprehensive assessment needed to translate computational predictions into successful experimental candidates. As QSAR methodologies continue to evolve, maintaining rigorous validation standards will remain essential for building trust in computational approaches and ultimately developing more effective cancer therapeutics.

Common Molecular Descriptors and Datasets in Cancer QSAR Studies

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict the biological activity and physicochemical properties of compounds based on their molecular structures. In oncology research, QSAR models provide an invaluable tool for prioritizing synthetic efforts, understanding structure-activity relationships, and identifying potential anticancer agents with desired efficacy profiles. These computational approaches have gained significant importance in recent years due to their ability to reduce reliance on animal testing through New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), offering faster, less expensive alternatives for early-stage drug screening while maintaining ethical standards [23].

The predictive power of QSAR models hinges on two fundamental components: molecular descriptors that numerically represent structural features, and robust datasets containing reliable bioactivity measurements. Molecular descriptors quantify diverse aspects of molecular structure, from simple atomic properties to complex quantum chemical calculations, while datasets provide the experimental foundation upon which models are built and validated. Understanding the interplay between these components, particularly within the context of proper validation techniques like Leave-One-Out (LOO) and Leave-Many-Out (LMO) cross-validation, is essential for developing reliable predictive models in cancer drug discovery [7].

Common Molecular Descriptors in Cancer QSAR Studies

Molecular descriptors serve as the mathematical representation of molecular structures and properties, forming the independent variables in QSAR models. The selection of appropriate descriptors is critical for model interpretability and predictive performance, with different descriptor classes offering distinct advantages for specific applications in cancer research.

Quantum Chemical Descriptors

Quantum chemical descriptors derived from computational chemistry methods provide insights into electronic structure and reactivity properties that influence biological activity. Studies on anti-colorectal cancer agents have identified several significant quantum chemical descriptors, including total electronic energy (E~T~), charge of the most positive atom (Q~max~), and electrophilicity (ω) [24]. These descriptors validate the importance of electronic properties in modeling anti-cancer activity and can be obtained through gaseous-state Gaussian optimization at HF/3-21G level in a vacuum, providing robust yet computationally accessible parameters for QSAR modeling.

Two-Dimensional (2D) Descriptors

Two-dimensional descriptors remain widely used due to their computational efficiency and clear structural interpretability. Research on triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) inhibitors has identified several key 2D descriptors that correlate with cytotoxicity against MDA-MB231 cells, including electronegativity (Epsilon-3), carbon atoms separated through five bond distances (TCC_5), electrotopological state indices of -CH~2~ groups (SssCH2count), z-coordinate dipole moment (Zcomp Dipole), and the distance between highest positive and negative electrostatic potential on van der Waals surface area [25]. These descriptors capture essential electronic, topological, and steric properties that influence compound binding and biological activity.

Topological Descriptors

Topological descriptors encode molecular connectivity patterns and have demonstrated significant utility in breast cancer QSAR studies. Recent research has explored novel entire neighborhood topological indices, which provide comprehensive characterization of atomic environments and bonding patterns [26]. These indices include first, second, and modified entire neighborhood indices, as well as newly developed entire neighborhood forgotten and modified entire neighborhood forgotten indices. Such descriptors have shown strong correlations with physicochemical properties of breast cancer drugs, enabling predictive modeling of their behavior.

SMILES-Based Descriptors

SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) notation provides an alternative approach to molecular representation through string-based descriptors. Studies on anti-colon cancer chalcone analogues have demonstrated that hybrid optimal descriptors combining SMILES notation with hydrogen-suppressed molecular graphs (HSG) can achieve excellent predictive performance, with validation R² values reaching 0.90 [27]. The SMILES-based approach allows for efficient representation of complex molecular structures while maintaining interpretability through identified structural promoters.

Table 1: Common Molecular Descriptors in Cancer QSAR Studies

| Descriptor Category | Specific Examples | Cancer Type Applications | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemical | Total electronic energy (E~T~), Most positive atomic charge (Q~max~), Electrophilicity (ω) | Colorectal cancer [24] | Describe electronic structure and reactivity; Computed at HF/3-21G level |

| 2D Descriptors | Electronegativity (Epsilon-3), TCC_5, SssCH2count, Zcomp Dipole | Triple-negative breast cancer [25] | Capture electronic, topological, and steric properties |

| Topological Indices | Entire neighborhood indices, Entire forgotten index, Modified entire neighborhood indices | Breast cancer [26] | Encode molecular connectivity and atomic environments |

| SMILES-Based | Hybrid optimal descriptors (SMILES + Graph) | Colon cancer [27] | String-based representations with high predictive power |

Datasets for Cancer QSAR Modeling

The development of robust QSAR models requires high-quality, well-curated datasets containing reliable bioactivity measurements. These datasets vary in size, composition, and source, with each offering distinct advantages and limitations for different cancer types and research objectives.

Colon Cancer Datasets

Colon cancer research has benefited from carefully constructed datasets focusing on specific compound classes. Studies on chalcone derivatives have utilized datasets of 193 compounds tested against HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cell lines, with activity measurements expressed as pIC~50~ values ranging from 3.58 to 7.00 [27]. These datasets are typically compiled from multiple published sources and standardized using rigorous curation protocols to ensure consistency in structural representation and activity measurements.

Breast Cancer Datasets

Breast cancer QSAR studies employ diverse datasets reflecting the heterogeneity of this disease. Research on triple-negative breast cancer has utilized datasets comprising 99 known MDA-MB-231 inhibitors sourced from the ChEMBL database and published literature [25]. These datasets focus specifically on the aggressive TNBC subtype and include structurally diverse chemical series, particularly terpene derivatives and analogs with measured IC~50~ values. Additionally, studies on breast cancer drugs more broadly have examined 16 established therapeutic agents, including Azacitidine, Cytarabine, Daunorubicin, Docetaxel, Doxorubicin, and Paclitaxel, focusing on their physicochemical properties [26].

Genotoxicity and Carcinogenicity Datasets

Beyond direct anticancer activity, QSAR models also address genotoxicity and carcinogenicity endpoints crucial for safety assessment. Research in this area has led to the development of consolidated micronucleus assay datasets, including 981 chemicals for in vitro micronucleus testing and 1,309 chemicals for in vivo mouse micronucleus assays [28]. These datasets are constructed through extensive literature mining using advanced natural language processing approaches, specifically the BioBERT large language model fine-tuned for biomedical text mining, followed by expert curation to ensure data quality and relevance.

Public Databases and Repositories

Several public databases serve as valuable resources for QSAR model development in cancer research. The ChEMBL database provides extensively curated bioactivity data, including drug-target interactions and inhibitory concentrations, with version 34 containing over 2.4 million compounds and 15,598 targets [29]. The DBAASP database offers specialized collections of anticancer peptides, while the EFSA Genotoxicity Pesticides Database provides curated information relevant to carcinogenicity assessment [23] [30]. These repositories enable researchers to access standardized, annotated bioactivity data for model building and validation.

Table 2: Representative Datasets in Cancer QSAR Research

| Cancer Type/Endpoint | Dataset Size | Activity Measure | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colon Cancer (Chalcones) | 193 compounds | pIC~50~ against HT-29 cells | Multiple published studies [27] |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer | 99 inhibitors | IC~50~ against MDA-MB-231 cells | ChEMBL database & literature [25] |

| Breast Cancer Drugs | 16 drugs | Physicochemical properties | Established therapeutics [26] |

| In Vitro Micronucleus | 981 chemicals | Binary (positive/negative) | PubMed, ISSMIC, EURL ECVAM [28] |

| In Vivo Micronucleus (Mouse) | 1,309 chemicals | Binary (positive/negative) | Multiple databases & literature [28] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

QSAR Model Development Workflow

The development of validated QSAR models follows a systematic workflow encompassing data preparation, model building, validation, and application. The diagram below illustrates this process, highlighting critical steps for ensuring model reliability and predictive power.

Data Curation Protocols

Robust data curation is essential for developing reliable QSAR models. For micronucleus assay datasets, researchers implement comprehensive curation protocols including: standardization of chemical structures using tools like RDKit; removal of mixtures, polymers, and inorganic compounds; neutralization of salts to parent structures; and duplicate removal through InChiKeys comparison [28]. Additionally, experimental results are carefully reviewed for compliance with OECD test guidelines (e.g., OECD 487 for in vitro micronucleus, OECD 474 for in vivo micronucleus), with technically compromised studies excluded from final datasets.

Model Validation Techniques

Proper validation is crucial for assessing model predictive power and avoiding overoptimistic performance estimates. Double cross-validation (also called nested cross-validation) provides a robust framework for both model selection and assessment [7]. This approach consists of two nested loops: an inner loop for model selection and parameter optimization, and an outer loop for unbiased error estimation. The inner loop typically employs LOO or LMO cross-validation to select optimal model parameters, while the outer loop assesses the final model performance on independent test sets, effectively eliminating model selection bias that can occur with single-level validation approaches.

Performance Metrics

QSAR model quality is assessed using multiple statistical metrics, including: coefficient of determination (R²) for goodness of fit; cross-validated R² (Q²) for internal predictive ability; index of ideality correlation (IIC) for model robustness; and accuracy/sensitivity/specificity for classification models [27] [7] [25]. These metrics collectively provide a comprehensive picture of model performance, with acceptable QSAR models typically demonstrating Q² > 0.5 and R² > 0.6, though higher thresholds are preferred for reliable predictions.

Successful QSAR modeling in cancer research relies on a diverse toolkit of software, databases, and computational resources that facilitate data curation, descriptor calculation, model building, and validation.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Cancer QSAR Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR Software | CORAL, QSARINS, V-Life MDS | Model development & validation | Monte Carlo optimization, descriptor selection [27] |

| Descriptor Calculation | RDKit, ChemBioDraw, Dragon | Molecular descriptor computation | 2D/3D descriptor calculation [31] [28] |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, DrugBank | Bioactivity data source | Compound sourcing, activity data [29] |

| Text Mining | BioBERT, PubMed | Data extraction from literature | Automated dataset construction [28] |

| Docking & Dynamics | PyRx, AutoDock Vina, GROMACS | Structure-based modeling | Binding mode analysis, stability assessment [31] [30] |

The landscape of cancer QSAR research is characterized by diverse molecular descriptors tailored to specific cancer types and endpoints, complemented by increasingly sophisticated datasets constructed through both manual curation and automated text mining approaches. Quantum chemical descriptors offer fundamental insights into electronic properties governing anti-cancer activity, while 2D, topological, and SMILES-based descriptors provide computationally efficient alternatives with strong predictive power. The reliability of resulting models hinges critically on rigorous validation protocols, particularly double cross-validation approaches that provide unbiased performance estimates under model uncertainty. As the field advances, integration of QSAR predictions with experimental validation through molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and in vitro testing will continue to enhance the efficiency of anti-cancer drug discovery, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective and selective cancer therapeutics.

In the field of cancer research, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models have become indispensable tools for accelerating drug discovery. These computational models predict the biological activity of chemical compounds against specific cancer targets, guiding researchers toward promising therapeutic candidates [32] [33]. The reliability of these models depends critically on rigorous validation practices, with cross-validation being a fundamental technique for assessing predictive performance and minimizing overfitting [34] [35].

Among cross-validation methods, Leave-One-Out cross-validation (LOO CV) has been widely adopted, particularly in QSAR studies featuring limited compound datasets. The LOO q² statistic (or Q²) has traditionally served as a primary metric for judging model quality, with higher values generally interpreted as indicating better predictive capability [33] [36]. However, within the context of cancer QSAR research—where model failures can misdirect precious resources in drug development—this article demonstrates that while LOO q² represents a necessary condition for model acceptability, it is far from sufficient as a standalone validation measure.

Understanding LOO Cross-Validation and Its Statistical Appeal

The LOO CV Methodology

Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOO CV) is a resampling technique that systematically excludes each compound from the dataset once, using the remaining compounds to build a model that predicts the omitted observation [34]. For a dataset containing N compounds, this process involves N separate model building and prediction cycles. The LOO q² statistic is then calculated as:

[ q² = 1 - \frac{\sum{(y{i} - ŷ{i})^2}{\sum{(y_{i} - \bar{y})^2} ]

where (y{i}) represents the observed activity value, (ŷ{i}) is the predicted activity value when the ith compound is excluded from model building, and (\bar{y}) is the mean of all observed activity values [36].

Why LOO CV Gained Prominence in Cancer QSAR

LOO CV offers particular appeal for cancer QSAR studies, which often face limited compound availability due to the cost and complexity of synthetic and biological testing [37]. The method's advantages include:

- Maximized Training Data: Each model training iteration utilizes N-1 compounds, minimizing bias in small datasets [34]

- Comprehensive Usage: Every compound serves in both training and testing capacities across the validation process

- Theoretical Appeal: The approach appears to provide a thorough assessment of predictive capability

These attributes have led to LOO q² becoming a standard reporting requirement in many QSAR publications, with models often judged primarily on this metric [33] [36].

The "Necessary But Not Sufficient" Principle in Model Validation

Logical Foundation of the Principle

The concept of a condition being "necessary but not sufficient" has a precise meaning in logical reasoning. A necessary condition (A) for an outcome (B) must be present for B to occur, but its presence alone does not guarantee B [38]. In the context of QSAR validation:

- LOO q² as Necessary Condition: A sufficiently high q² value is required for a model to be considered predictive

- Insufficiency Demonstrated: High q² alone does not ensure reliable predictions for novel compounds

This logical fallacy occurs when researchers treat the necessary condition (good LOO q²) as sufficient for establishing model validity [38] [39].

Mathematical and Practical Limitations of LOO q²

Despite its widespread use, LOO CV exhibits several critical limitations that undermine its reliability as a sole validation metric:

- High Variance: The method can produce unstable estimates, particularly with small datasets or outliers [34]

- Insufficient Stress Testing: Models are not adequately tested on structurally diverse compounds simultaneously

- Ambiguity in Thresholds: Arbitrary q² cutoff values (e.g., 0.5) provide false security without complementary metrics [36]

The fundamental issue is that LOO CV primarily assesses interpolative capability within the chemical space of the training set, while QSAR models are most valuable for their extrapolative power to truly novel chemotypes [40].

Comparative Analysis of Cross-Validation Techniques in Cancer QSAR

Beyond LOO: Alternative Validation Methods

Robust QSAR model validation requires multiple approaches that complement LOO CV's limitations:

- Leave-Many-Out Cross-Validation (LMO CV): Also known as k-fold cross-validation, this method excludes multiple compounds (typically 10-30%) during each validation cycle, providing a more challenging test of model robustness [33]

- External Validation: The most rigorous approach uses a completely independent compound set not involved in model development, directly simulating real-world prediction scenarios [32] [40]

- Y-Randomization: This technique scrambles activity values to ensure models cannot achieve good statistics by chance alone, testing for chance correlation [33] [36]

Table 1: Comparison of Cross-Validation Methods in Cancer QSAR Research

| Validation Method | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations | Reported Usage in Cancer QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOO CV | Each compound omitted once; N iterations | Maximizes training data; Low bias | High variance; Optimistic estimates | Widely used (e.g., [33] [36]) |

| LMO CV | Multiple compounds omitted; k folds (k=5-10) | Better variance estimation; More challenging test | Smaller training sets; Computational cost | Increasing adoption (e.g., [33]) |

| External Validation | Completely independent compound set | Real-world simulation; Most reliable assessment | Requires additional experimental data | Gold standard (e.g., [32] [40]) |

Case Studies: LOO q² Limitations in Practical Cancer Research

Recent cancer QSAR studies demonstrate the insufficiency of LOO q² alone:

- In a breast cancer QSAR model developing combinational therapy, Deep Neural Networks achieved impressive LOO q² values (0.94) but required external validation on separate cell lines to confirm practical utility [32]

- A study on aurora kinase inhibitors for breast cancer reported both LOO q² (0.7875) and LMO q² (0.7624), with the divergence between values indicating potential overfitting had only LOO been considered [33]

- Research on anti-colorectal cancer agents combined cross-validation with multiple metrics including R², RMSE, and interaction terms to provide comprehensive model assessment beyond single q² values [24]

Table 2: Representative Validation Approaches in Recent Cancer QSAR Studies

| Research Focus | LOO q² Reported | Additional Validation | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Combinational Therapy | R²=0.94 (DNN) | External test set validation | Model generalized well to novel drug combinations | [32] |

| Aurora Kinase Inhibitors | Q²LOO=0.7875 | LMO (Q²LMO=0.7624); External set (R²ext=0.8735) | Discrepancy highlighted need for multiple metrics | [33] |

| Lung Surfactant Inhibition | 5-fold CV accuracy=96% | 10 random seeds; Multiple metrics (F1 score=0.97) | Comprehensive protocol revealed true performance | [40] |

Implementing Robust Validation Protocols: A Practical Guide

Essential Components of QSAR Validation

Based on analysis of successful cancer QSAR studies, robust validation should incorporate these elements:

- Multiple Resampling Methods: Combine LOO with LMO (k-fold) cross-validation [33]

- External Test Set: Reserve 20-30% of compounds for final validation [32] [40]

- Diverse Statistical Metrics: Include R², RMSE, MAE, and domain-specific metrics [32] [40]

- Y-Randomization: Verify models outperform random chance [33] [36]

- Applicability Domain Assessment: Define chemical space where predictions are reliable [40]

Recommended Workflow for Cancer QSAR Validation

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive validation protocol that positions LOO q² as one component within a multifaceted validation strategy:

Diagram 1: Comprehensive QSAR Validation Workflow (Title: QSAR Validation Protocol)

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Validation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Libraries | RDKit, PaDEL-Descriptor, Mordred | Molecular descriptor calculation | Generate structural features for modeling [40] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | scikit-learn, DTC-Lab, PyTorch | Model building and validation | Implement cross-validation protocols [32] [40] |

| Specialized QSAR Software | QSARINS, Material Studio | Dedicated QSAR analysis | Built-in validation statistics [33] |

| Data Processing Tools | Scikit-learn preprocessing, DTC-Lab pretreatment | Data standardization and splitting | Ensure proper train/test separation [32] [40] |

The LOO q² statistic remains a valuable initial screening tool in QSAR model development—a necessary first hurdle that models must clear. However, treating this metric as a sufficient condition for model validity represents a critical methodological error with potentially significant consequences in cancer drug discovery. Robust validation requires a multifaceted approach that combines LOO with LMO cross-validation, external validation, and complementary statistical measures.

As cancer QSAR research increasingly incorporates complex machine learning algorithms and tackles more challenging therapeutic targets, the validation standards must evolve accordingly. By recognizing LOO q² as necessary but insufficient, researchers can implement more rigorous validation protocols that ultimately yield more reliable, predictive models—accelerating the discovery of urgently needed cancer therapeutics.

Implementing LOO and LMO Cross-Validation in Anti-Cancer QSAR Workflows

Step-by-Step Protocol for LOO Cross-Validation Implementation

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling is essential in drug discovery for predicting the biological activity of chemical compounds based on their structural features [41]. In cancer research, reliable QSAR models help prioritize compounds for synthesis and testing. Cross-validation (CV) is a fundamental procedure for estimating the predictive performance of these models, with Leave-One-Out (LOO) and Leave-Many-Out (LMO) being two pivotal techniques [42] [43]. This guide provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for implementing LOO cross-validation, objectively compares it with LMO, and presents experimental data within cancer QSAR research.

Conceptual Foundations of LOO and LMO

Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation

LOO-CV is an exhaustive cross-validation technique where each compound in the dataset is systematically held out once as the test set, while the remaining n-1 compounds form the training set [44] [45]. This process repeats for all n compounds in the dataset. The final performance metric is the average of all n individual evaluations [46]. The core advantage of LOO is that it maximizes the data used for training, resulting in a less biased estimate, which is particularly valuable with small datasets [45] [46].

Leave-Many-Out (LMO) Cross-Validation

LMO-CV, also known as k-fold cross-validation, involves partitioning the dataset into k subsets (folds) of approximately equal size [45]. In each iteration, one fold is held out as the test set, and the remaining k-1 folds are used for model training. This process repeats k times until each fold has served as the test set once [35]. Typical values for k are 5 or 10 [45]. LMO introduces more randomness in the data splitting compared to the deterministic LOO, but is computationally more efficient for larger datasets [43].

The workflow below illustrates the fundamental difference in how datasets are partitioned for LOO-CV versus LMO-CV.

Comparative Analysis: LOO vs. LMO in Practice

Theoretical and Practical Comparison

The choice between LOO and LMO involves trade-offs between bias, variance, and computational cost [45]. LOO-CV tends to have lower bias because each training set contains n-1 samples, making it nearly identical to the full dataset. However, since the test sets of LOO are highly similar (overlapping), the performance estimates can have higher variance [46]. Conversely, LMO-CV (e.g., 5-fold or 10-fold) has slightly higher bias but lower variance in its estimates due to more independent test sets [45]. Computationally, LOO requires fitting n models, which becomes prohibitive for large n or complex models, whereas LMO only requires fitting k models [45].

Performance Comparison in Cancer QSAR Studies

Empirical studies, particularly in cancer research, provide concrete performance data. The table below summarizes a comparison from a QSAR study on melanoma cell line SK-MEL-5, which utilized various machine learning classifiers [41].

Table 1: Comparison of LOO and 5-Fold LMO Performance in a Melanoma QSAR Study [41]

| Machine Learning Classifier | Average LOOCV Accuracy (%) | Average 5-Fold LMO Accuracy (%) | Optimal Descriptor Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | 88.5 | 86.2 | Topological descriptors, Information indices |

| Gradient Boosting (BST) | 85.1 | 83.7 | 2D-Autocorrelation descriptors |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 86.8 | 85.5 | P-VSA-like descriptors, Edge-adjacency indices |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | 82.3 | 80.9 | 2D-Autocorrelation descriptors |

A separate multi-level analysis of QSAR modeling methods further compared validation protocols across different case studies, providing general insights into the consistency of these methods [43].

Table 2: General Comparison of CV Methods Based on Multi-Level QSAR Analysis [43]

| Validation Aspect | LOO-CV | 5-Fold LMO (Random) | 5-Fold LMO (Contiguous) | 5-Fold LMO (Venetian Blind) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias of Estimate | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Variance of Estimate | High | Medium | High | Medium |

| Computational Cost | High | Low | Low | Low |

| Stability/Determinism | High (Deterministic) | Low (Randomized) | Medium | Medium |

| Resistance to Data Ordering | High | Medium | Low | High |

Step-by-Step LOO-CV Protocol for Cancer QSAR

This protocol is designed for researchers implementing LOO-CV in a Python environment, using standard QSAR data structures.

Prerequisites and Data Preparation

- Environment Setup: Ensure Python (v3.7+) is installed with the following core libraries:

scikit-learn(for model building and CV),pandas(for data handling),numpy(for numerical operations), andrdkitordragon(for calculating molecular descriptors if needed). - Dataset Curation: The dataset should consist of a matrix where rows represent unique chemical compounds and columns represent molecular descriptors and a biological activity endpoint (e.g., GI50, IC50 for cytotoxicity) [41]. For classification models, discretize the activity (e.g., 'active' if GI50 < 1 µM, 'inactive' otherwise) [41].

- Data Pre-processing:

- Descriptor Filtering: Remove descriptors with constant or near-constant values.

- Handling Missing Values: Remove descriptors or impute missing values.

- Reducing Correlarity: Remove highly correlated descriptors (e.g., correlation coefficient > 0.80) to mitigate multicollinearity [41].

- Feature Selection: Apply feature selection methods (e.g., Random Forest importance, symmetrical uncertainty) to reduce dimensionality. Select a manageable number of top descriptors (e.g., 7-15) [41].

Detailed LOO-CV Implementation Code

The following Python code demonstrates the LOO-CV procedure for a Random Forest classifier, a common and robust algorithm in QSAR studies [41].

Performance Evaluation and Model Validation

After completing the LOO-CV procedure, a comprehensive evaluation is necessary.

- Calculate Performance Metrics: Beyond accuracy, calculate metrics relevant to your research question. For classification, report Precision, Recall, Specificity, and F1-Score. For regression, use Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and the Coefficient of Determination (R²) [42] [47].

- External Validation: The OECD principles for QSAR validation stress the importance of external validation. After finalizing a model using LOO-CV internally, its predictive power must be confirmed on a truly external test set of compounds that were never used in any model-building or CV step [47] [6].

- Assess Model Applicability Domain: Define the chemical space area where the model's predictions are reliable. This can be assessed using leverage, distance-based methods, or ranges of descriptor values [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Building and validating a robust cancer QSAR model requires a suite of computational tools and data resources. The table below lists key components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Cancer QSAR Modeling

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Database | Source of experimental biological activity data for model training and testing. | PubChem BioAssay (source of SK-MEL-5 GI50 data) [41] |

| Chemical Standardization Tool | Standardizes molecular structures into a consistent representation for descriptor calculation. | ChemAxon Standardizer [41] |

| Descriptor Calculation Software | Computes numerical representations of molecular structures from 1D to 3D. | Dragon software [41] |

| Machine Learning Framework | Provides algorithms for building classification/regression models and validation procedures. | Scikit-learn (Python) [35] [45] |

| Statistical Analysis Environment | Used for data pre-processing, statistical analysis, and visualization. | R programming language [41] |

Experimental Protocol & Workflow from a Cited Study

To ground this guide in practical research, the following diagram and summary detail the protocol from a published QSAR study on SK-MEL-5 melanoma cell line cytotoxicity [41].

Summary of Key Experimental Details [41]:

- Dataset: 422 unique compounds after duplicate removal, with 174 active and 248 inactive on SK-MEL-5.

- Descriptors: 13 blocks of molecular descriptors were computed (e.g., topological indices, 2D-autocorrelations, edge-adjacency indices) and pre-processed.

- Modeling: Four machine learning classifiers (RF, BST, SVM, KNN) were used. LOO-CV was performed on the training set (n=316) for model selection and evaluation.

- Results: The best models (all Random Forests) achieved a LOO-CV accuracy of ~88.5% and a positive predictive value (PPV) higher than 0.85 upon external validation.

LOO-CV is a powerful validation technique for QSAR models, especially when working with small, precious datasets common in early-stage cancer drug discovery. It provides a nearly unbiased estimate of model performance by maximizing the use of available data. While LMO-CV (e.g., 5-fold) offers a computationally cheaper and potentially less variable alternative, LOO-CV remains a gold standard for rigorous internal validation [6] [43]. The optimal choice depends on the dataset size, computational resources, and the specific requirement for bias-variance trade-off. Ultimately, a well-validated QSAR model should employ rigorous internal validation like LOO-CV and must be confirmed by a strong external validation test to ensure its reliability for predicting the activity of new, untested compounds.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone methodology in modern computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict the biological activity of compounds based on their chemical structures [13]. These statistical models correlate molecular descriptors—numerical representations of chemical properties—with biological responses, providing invaluable insights for lead optimization and virtual screening in anticancer drug development [17]. The reliability and predictive power of QSAR models hinge critically on rigorous validation techniques, with cross-validation standing as an indispensable component for assessing model robustness and preventing overfitting [1].

Within the landscape of cross-validation methods, Leave-One-Out (LOO) and Leave-Many-Out (LMO) strategies represent two fundamentally different approaches to model validation. LOO cross-validation, a more traditional approach, involves iteratively removing a single compound from the training set, building a model with the remaining compounds, and predicting the activity of the omitted compound [48]. This process repeats until every compound has been left out once. While computationally intensive, LOO provides a nearly unbiased estimate of model performance but may overestimate predictive accuracy for small datasets and fail to adequately assess model stability [49].

LMO cross-validation, alternatively known as k-fold cross-validation, addresses several limitations of LOO by systematically excluding multiple compounds simultaneously—typically between 10-30% of the dataset—during each validation iteration [49] [48]. This approach more effectively evaluates model stability against data fluctuations and provides a more realistic assessment of predictive performance on external compounds, making it particularly valuable for cancer QSAR models where dataset diversity and model applicability are paramount concerns [50]. The strategic implementation of LMO validation directly supports the development of more reliable predictive models for identifying novel anticancer therapeutics, ultimately accelerating the drug discovery pipeline while reducing resource-intensive experimental screening.

Theoretical Foundations of LMO Validation

Mathematical Framework and Algorithmic Implementation

The Leave-Many-Out cross-validation technique operates on a robust mathematical foundation designed to thoroughly evaluate QSAR model performance. The core algorithm partitions the complete dataset of N compounds into k distinct subsets of approximately equal size through random selection, though stratified sampling based on chemical structural features or activity ranges may be employed for cancer-related targets to ensure representative distribution [48]. The LMO procedure iteratively designates one subset (approximately N/k compounds) as the temporary validation set while using the remaining k-1 subsets (approximately N×(k-1)/k compounds) for model training. This process repeats k times until each subset has served as the validation set exactly once [49].

The predictive performance of LMO cross-validation is quantified using the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²), calculated as follows:

Q² = 1 - [Σ(yobserved - ypredicted)² / Σ(yobserved - ymean)²]

where yobserved represents the experimental biological activity values, ypredicted denotes the predicted activities from the LMO validation, and y_mean signifies the mean observed activity of the training set [48]. This metric directly measures the model's predictive capability, with values approaching 1.0 indicating excellent predictive power. Additional statistical parameters frequently reported alongside Q² include Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values for both training and validation sets, which provide insights into prediction accuracy, and the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC), which evaluates the agreement between observed and predicted values [51].

The critical distinction between LMO and LOO validation emerges from their respective approaches to dataset partitioning. While LOO represents an extreme case of LMO where k equals the number of compounds (N), this approach tends to yield higher variance in prediction error estimates for smaller datasets common in early-stage anticancer drug discovery [49]. The LMO method, with its intentional grouping of compounds, provides a more stringent assessment of model robustness by simulating how the model performs when predicting multiple structurally diverse compounds simultaneously, thus better approximating real-world virtual screening scenarios where models must predict activities for entirely new chemical classes [1].

OECD Guidelines for LMO Validation

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has established definitive guidelines for QSAR model validation, with Principle 4 explicitly addressing the necessity of appropriate validation methods [52] [51]. These internationally recognized guidelines mandate that LMO validation must demonstrate acceptable statistical quality through multiple metrics including Q², RMSE, and CCC values to establish scientific validity for regulatory purposes in drug development [51]. The OECD guidelines further recommend that the number of LMO groups (k) and their composition be carefully selected based on dataset size and diversity, with specific emphasis on ensuring that each group represents the structural and activity space of the entire dataset [49].

For QSAR models targeting cancer therapeutics, adherence to these guidelines becomes particularly crucial given the potential clinical implications of model predictions. The OECD framework emphasizes that LMO validation should assess both internal predictability (through the Q² metric) and external predictability (through validation with truly external compounds not included in any model development), with the latter being especially important for establishing model utility in prospective virtual screening [51]. Recent research in anti-breast cancer QSAR models has further refined these guidelines by recommending that LMO group composition should account for chemical clustering based on molecular scaffolds to prevent overoptimistic performance estimates when structurally similar compounds are grouped together [13] [52].

Comparative Analysis: LMO vs. LOO Cross-Validation

Performance Metrics and Statistical Robustness

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of LMO and LOO Cross-Validation in Cancer QSAR Studies

| Validation Metric | LMO Cross-Validation | LOO Cross-Validation | Statistical Significance & Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q² Value Range | 0.7865 - 0.8558 [51] | Typically 0.05-0.15 higher than LMO for same dataset [48] | LMO provides more conservative, realistic estimate of external predictivity |

| Variance in Error Estimation | Lower variance due to compound grouping [49] | Higher variance, especially with small datasets [48] | LMO offers more stable performance estimates across different data partitions |

| Computational Intensity | Moderate (k iterations) [48] | High (N iterations for dataset size N) [48] | LMO more practical for large virtual screening libraries in cancer drug discovery |