Computational Design of Kinase Inhibitors: Advanced Molecular Docking Protocols for Cancer Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying molecular docking protocols to discover and optimize kinase inhibitors for cancer therapy.

Computational Design of Kinase Inhibitors: Advanced Molecular Docking Protocols for Cancer Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying molecular docking protocols to discover and optimize kinase inhibitors for cancer therapy. It covers the foundational biology of kinase targets, detailed methodological workflows for docking and virtual screening, strategies for troubleshooting common challenges like selectivity and resistance, and advanced techniques for validating and benchmarking results. By integrating recent case studies and emerging trends, such as machine learning and hybrid docking-MD pipelines, this resource aims to enhance the efficiency and predictive power of structure-based kinase drug design.

Understanding Kinase Targets: Structural Biology and Therapeutic Significance in Oncology

Protein kinases represent one of the most extensive and biologically important enzyme families in the human genome, constituting key regulators of most aspects of eukaryotic cellular behavior [1] [2]. These enzymes catalyze the transfer of a phosphate group from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to specific amino acid residues on target proteins, thereby regulating their activity, localization, and interaction with other molecules [1] [3]. This phosphorylation mechanism serves as a fundamental molecular switch that fine-tunes signaling cascades to regulate critical cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, metabolism, and responses to environmental stress [1]. The complete set of protein kinases encoded in an organism's genome, known as the kinome, has a profound impact on the biological properties of that organism [2].

The eukaryotic protein kinase (ePK) superfamily is divided into several major groups based on evolutionary relationships and sequence homology [2]. The most fundamental classification of protein kinases is based on their substrate specificity, primarily distinguishing between serine/threonine kinases (STKs) that phosphorylate serine or threonine residues and tyrosine kinases (TKs) that phosphorylate tyrosine residues [4]. Some kinases demonstrate dual specificity, capable of phosphorylating all three residues [5]. The advent of the tyrosine kinase group correlates with the rise of metazoans, highlighting their importance in complex multicellular organisms [2]. Of these, serine/threonine kinases constitute the most abundant class, accounting for over 70% of the human kinome [1] [3].

Table 1: Major Kinase Groups in the Human Kinome

| Kinase Group | Primary Substrate | Approximate Percentage of Kinome | Key Representative Families |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serine/Threonine Kinases (STKs) | Serine/Threonine | ~70% | MAPK, CDK, Akt, mTOR, AMPK, GSK3β [1] [3] |

| Tyrosine Kinases (TKs) | Tyrosine | ~10% | EGFR, HER2, FGFR, BTK, JAK [4] [6] |

| Dual-Specificity Kinases | Ser/Thr/Tyr | <5% | NEK10 [5] |

| Atypical Kinases (aPKs) | Varied | ~15% | PKLs, SelO, SidJ [2] [7] |

The clinical relevance of protein kinases is well-established, as aberrant kinase activity is implicated in diverse human diseases, particularly cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory conditions [1] [8]. The drug targetability of kinases has been demonstrated by the impressive number of clinically successful kinase inhibitors, with the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) having approved over seventy small-molecule kinase inhibitors since 2001 [1] [3]. This review will explore the classification, structural features, and functional roles of serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases, with particular emphasis on their relevance to molecular docking protocols for kinase inhibitor development in cancer research.

Structural Features of Kinase Domains

Conserved Kinase Architecture

Protein kinases share a highly conserved bilobal catalytic domain structure that is characteristic of the kinase superfamily [1]. The smaller N-terminal lobe (N-lobe) is predominantly composed of β-sheets and contains several functionally critical elements: the glycine-rich loop (G-loop) that stabilizes ATP-binding, the VAIK motif containing a conserved lysine responsible for interaction with phosphate groups of ATP, and the αC-helix [1] [5]. The C-terminal lobe (C-lobe), which is substantially larger and mainly α-helical, forms the peptide substrate-binding interface and contains the catalytic loop with the HRD motif, the activation loop with the DFG motif, and the APE motif [1] [5].

The catalytic mechanism involves proper orientation of the ATP molecule and transfer of its γ-phosphate to the hydroxyl group of a serine, threonine, or tyrosine residue on the substrate protein. This process requires precise coordination between the N-lobe and C-lobe, facilitated by several conserved motifs. The catalytic spine (C-spine) and regulatory spine (R-spine) consist of hydrophobic residues that assemble during kinase activation to create a stable framework for catalysis [9]. The formation of a salt bridge between a conserved lysine in the β3 strand and a glutamate in the αC-helix (K-E salt bridge) is essential for proper orientation of the ATP molecule for phosphotransfer [5] [9].

Classification of Kinase Conformational States

Protein kinases are dynamic molecules that adopt distinct conformational states regulating their catalytic activity. The most fundamental conformational change is the transition between active and inactive states [9]. The activation segment, also known as the T-loop, whose conformation governs active versus inactive states, lies between the DFG and APE motifs [5]. Key structural features used to classify kinase conformations include:

- DFG Motif Orientation: The DFG motif can adopt "DFG-in" or "DFG-out" conformations. In the DFG-in state, the aspartate chelates a magnesium ion that coordinates ATP phosphates, while in DFG-out, the phenylalanine side chain occupies the ATP-binding pocket, creating a hydrophobic pocket targeted by Type II inhibitors [9].

- αC-helix Position: The αC-helix can be "αC-in" or "αC-out," with the αC-in position facilitating formation of the crucial K-E salt bridge [9].

- Activation Loop Conformation: In active kinases, the activation loop is ordered and positioned to allow substrate access, while in inactive kinases, it may block the substrate-binding site [9].

Machine learning approaches have been developed to classify kinase conformations based on activation segment orientation measured by φ, ψ, χ1, and pseudo-dihedral angles, providing more accurate classification than methods focused solely on active site geometry [9]. These conformational classifications are crucial for structure-based drug design, as different inhibitor classes target specific kinase conformations.

Serine/Threonine Kinases: Classification and Functions

Major STK Families and Their Cellular Roles

Serine/threonine kinases constitute the most abundant class of protein kinases in the human kinome and regulate diverse signaling pathways governing cell growth, proliferation, metabolism, and apoptosis [1]. STKs act as molecular switches that fine-tune signaling cascades to regulate cell fate [1]. Several STK families play pivotal roles in cellular homeostasis and disease pathogenesis:

- Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs): Mediate the effects of growth factors and cytokines, transmitting signals from cell surface receptors to nuclear transcription factors [1].

- Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (CDKs): Control cell-cycle progression, with CDK4/6 inhibitors like palbociclib becoming standard treatments for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer [1] [3].

- Akt and mTOR Kinases: Integrate nutrient and energy signals affecting cell survival and growth, with mTOR inhibitors (everolimus, temsirolimus) used clinically in oncology and tuberous sclerosis complex [1] [3].

- AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK): Functions as a metabolic sensor for restoring energy homeostasis during metabolic stress [1].

- Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3β (GSK3β) and CDK5: Play central roles in neuronal physiology and neurodegenerative diseases [1].

Table 2: Major Serine/Threonine Kinase Families and Their Functions

| STK Family | Key Members | Cellular Functions | Disease Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAPK | ERK1/2, JNK, p38 | Cell proliferation, differentiation, stress response | Cancer, inflammatory diseases [1] |

| CDK | CDK1-4, CDK6 | Cell cycle control, transcription | Cancer (CDK4/6 in breast cancer) [1] |

| AGC | Akt, PKA, PKC | Cell survival, metabolism | Cancer, metabolic disorders [1] [10] |

| CAMK | AMPK, CaMK | Energy sensing, calcium signaling | Metabolic disorders, cardiac disease [1] |

| NEK | NEK1-11 | Centrosome cycle, ciliogenesis, DNA damage response | Cancer, ciliopathies, neurodevelopmental disorders [8] [5] |

The NEK Family: A Case Study in STK Diversity

The Never-in-Mitosis A-related kinase (NEK) family provides an excellent example of STK functional diversity. The human NEK family comprises eleven members (NEK1-NEK11) that occupy a distinct branch on the human kinome phylogenetic tree [8] [5]. NEK family members play important roles in diverse cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, primary cilia formation, centrosome dynamics, and the DNA damage response (DDR) [8]. All NEKs share a conserved kinase domain but contain unique regulatory domains that confer functional specificity, such as coiled-coil motifs, DEAD-box domains, PEST sequences, RCC1 repeats, and Armadillo repeats [5].

NEK2, one of the best-characterized family members, illustrates the conformational regulation common to many STKs. NEK2 adopts either an active "Tyr-Up" conformation with a properly aligned αC-helix and formed K-E salt bridge, or an inactive, autoinhibited "Tyr-Down" conformation where the regulatory tyrosine rotates into the active site, disrupting αC-helix alignment and preventing the Lys-Glu interaction [5]. This structural plasticity represents both a challenge and opportunity for selective inhibitor design.

Tyrosine Kinases: Classification and Functions

Receptor and Non-Receptor Tyrosine Kinases

Tyrosine kinases are categorized into two major classes: receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and non-receptor tyrosine kinases (nRTKs). RTKs are transmembrane receptors that sense extracellular signals and initiate intracellular signaling cascades, while nRTKs are intracellular enzymes that relay and amplify signals from various cellular compartments [4]. Notable tyrosine kinase families include:

- Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Family: Includes EGFR (HER1), HER2, HER3, and HER4, which dimerize upon ligand binding and initiate signaling cascades promoting cell proliferation and survival [4] [6].

- Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR) Family: Regulates embryonic development, angiogenesis, wound healing, and metabolic homeostasis [6].

- Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase (BTK): Plays crucial roles in B-cell development and activation, with inhibitors like ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib approved for hematologic malignancies [6].

- Janus Kinases (JAKs): Associate with cytokine receptors and phosphorylate signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs), with JAK inhibitors used for inflammatory conditions and alopecia areata (ritlecitinib) [6].

TK Signaling in Colorectal Cancer: A Clinical Perspective

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have emerged as key therapeutic agents for colorectal cancer (CRC), illustrating the clinical importance of tyrosine kinase signaling [4]. The research landscape for TKIs in CRC treatment has identified several emerging trends, including microsatellite instability, biological evaluation, drug discovery, regorafenib, immunotherapy, and T-cell modulation [4]. Current research hotspots include development of novel TKIs, elucidation of TKI resistance mechanisms and corresponding overcoming strategies, evaluation of TKI efficacy and safety through biological assessments, and combination of TKIs with immunotherapy [4].

The most frequently cited reference in CRC TKI research is an international, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, Phase 3 trial demonstrating that regorafenib provides a survival benefit for patients with metastatic CRC who have progressed after all standard therapies [4]. This multi-targeted TKI suppresses tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis by blocking multiple cellular signaling receptors, thereby limiting CRC progression [4].

Computational Classification of Kinases

Bioinformatics Approaches for Kinome Analysis

The surge in genomic data has created a need to automate identification and classification of conserved and novel protein kinases. Kinannote is a computational tool that produces a draft kinome and comparative analyses for a predicted proteome using a single command [2]. This program automatically classifies protein kinases using the controlled vocabulary of Hanks and Hunter, employing a hidden Markov model in combination with a position-specific scoring matrix to identify kinases, which are subsequently classified using BLAST comparison with a local version of KinBase [2]. Kinannote demonstrates average sensitivity and precision of 94.4% and 96.8%, respectively, for kinome retrieval from test species [2].

More recently, constraint-based sequence clustering approaches have been applied to classify bacterial serine-threonine kinases (bSTKs), identifying 42 distinct families comprising canonical kinase and noncanonical pseudokinase families [7]. This classification revealed that although sequences within each STK family originated from multiple bacterial phyla, most kinase families were predominantly composed of sequences from a single phylum [7]. Actinobacteria exhibited the most diverse repertoire of STKs, encompassing 13 families and over 100,000 sequences unique to Actinobacterial species [7].

Machine Learning for Kinase Conformation Classification

Machine learning approaches have been developed to classify kinase conformations based on structural features [9]. These methods utilize automated pattern recognition algorithms to identify conformational changes between active and inactive protein kinases, with studies showing that the orientation of the activation segment alone is sufficient to accurately classify kinase conformations as active or inactive [9]. This approach has revealed that the greatest variation between inactive structures results from evolutionary relationships between kinases, identifying a variety of residues that can be used to increase drug specificity [9].

Diagram 1: Classification of Kinase Conformational States

Molecular Docking Protocols for Kinase Inhibitor Design

Structure-Based Drug Discovery Workflow

Structure-based drug discovery utilizing molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations has become a central strategy for identifying and optimizing kinase inhibitors [1] [3]. Molecular docking is primarily used to predict the binding poses of small molecules to kinases and their binding affinities, facilitating virtual screening of large chemical libraries and rational design of structure-activity relationships [1] [3]. In contrast, MD simulations move beyond static docking models to consider the time-resolved flexibility of kinases and their complexes, enabling exploration of loop motions, activation states, solvent effects, and resistance-associated mutations [1].

Integrated docking-MD workflows typically follow these steps:

- Target Preparation: Retrieval and preparation of kinase structures from the Protein Data Bank, including addition of hydrogen atoms, assignment of protonation states, and treatment of missing residues.

- Ligand Preparation: Generation of 3D structures of small molecule inhibitors with proper stereochemistry, tautomeric states, and charge assignments.

- Molecular Docking: Placement of small molecules into the kinase active site using scoring functions to predict binding geometry and affinity.

- MD Simulation: Refinement of docked complexes using nanosecond-to-microsecond simulations to assess complex stability and incorporate protein flexibility.

- Binding Free Energy Calculation: Estimation of binding affinities using methods such as MM-PBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) or free-energy perturbation.

- Experimental Validation: Synthesis and testing of predicted inhibitors using biochemical and cellular assays.

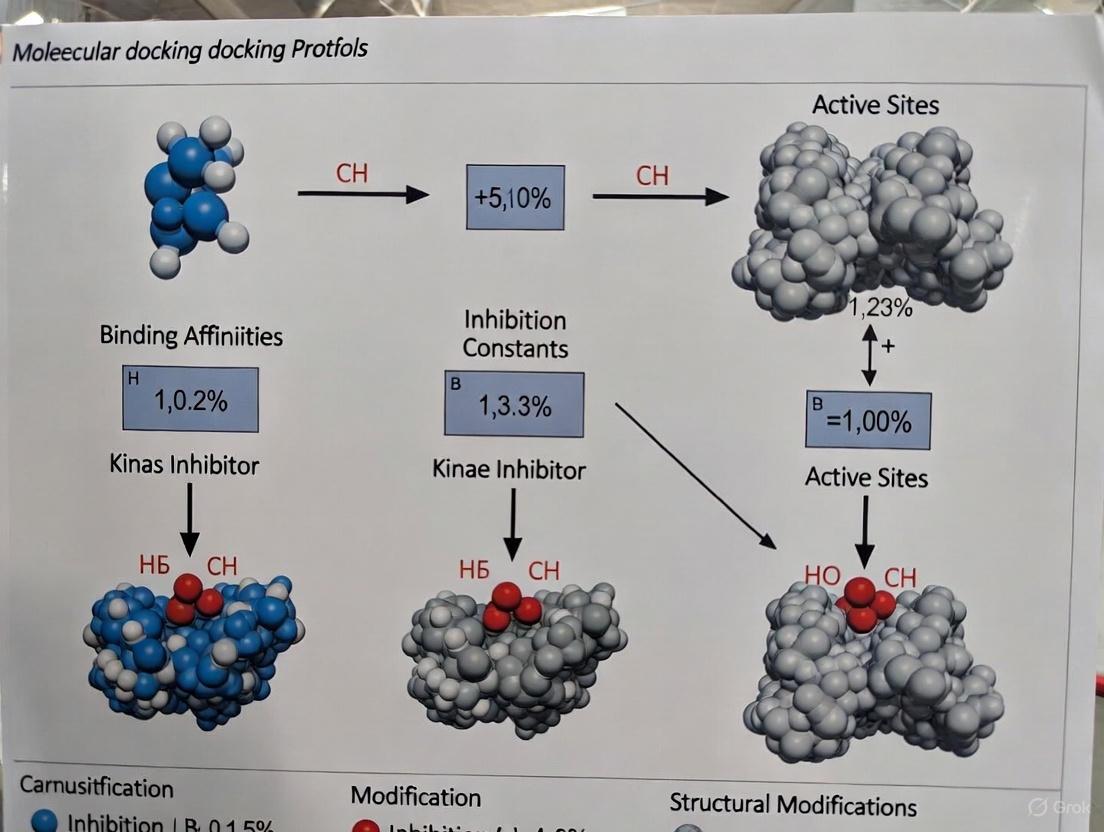

Diagram 2: Molecular Docking Workflow for Kinase Inhibitor Discovery

Targeted Covalent Inhibitors in Kinase Drug Discovery

Targeted covalent inhibitors (TCIs) represent an important class of kinase antagonists that form irreversible covalent complexes with their target enzymes [6]. These compounds typically contain an electrophilic warhead (most commonly an acrylamide) that reacts with a nucleophilic cysteine residue in the kinase active site, forming a stable thioether adduct [6]. The clinical efficacy of ibrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase blocker approved in 2013 for mantle cell lymphoma, helped overcome a general bias against the development of irreversible drug inhibitors [6].

As of 2025, eleven FDA-approved protein kinase targeted covalent inhibitors are available, including acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib (BTK inhibitors); afatinib, dacomitinib, lazertinib, mobocertinib, and osimertinib (EGFR family inhibitors); neratinib (ErbB2 inhibitor); futibatinib (FGFR inhibitor); and ritlecitinib (JAK3 inhibitor) [6]. The development of targeted covalent inhibitors is gaining acceptance as a valuable component of the medicinal chemist's toolbox and has made a significant impact on the development of protein kinase antagonists and receptor modulators [6].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Kinase Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Kinannote Software | Automated kinome identification and classification | Classifies kinases using Hanks and Hunter vocabulary; 94.4% sensitivity, 96.8% precision [2] |

| Machine Learning Classifiers | Kinase conformation classification | Activation segment orientation analysis using φ, ψ, χ1 angles [9] |

| Constraint-Based Clustering | Bacterial STK family classification | omcBPPS algorithm identifying 42 bSTK families [7] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Protein-ligand pose prediction | Virtual screening for kinase inhibitor identification [1] [3] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Binding mode refinement and stability assessment | Nanosecond-to-microsecond simulations of kinase-inhibitor complexes [1] |

| Targeted Covalent Inhibitors | Irreversible kinase inhibition | Acrylamide-containing inhibitors (ibrutinib, osimertinib, futibatinib) [6] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Kinase drug discovery continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. PROTACs (proteolysis targeting chimeras) represent an innovative approach that uses heterobifunctional molecules to recruit kinases to E3 ubiquitin ligases, leading to their degradation rather than simple inhibition [1] [3]. Allosteric inhibitors that target sites outside the conserved ATP-binding pocket offer potential for greater selectivity and ability to overcome resistance mutations [1]. Machine learning-augmented simulations and hybrid quantum mechanical methods are transforming molecular dynamics from a purely descriptive technique into a scalable, quantitative component of modern kinase drug discovery [1] [3].

The integration of computational and experimental approaches continues to advance kinase research, with cryo-electron microscopy providing high-resolution structural information on previously challenging targets like multi-protein kinase complexes [1]. As our understanding of kinase biology deepens and technological capabilities expand, the classification and targeting of serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases will continue to yield innovative therapeutics for cancer and other diseases driven by aberrant kinase signaling.

Protein kinases are pivotal regulators of cellular signaling pathways, controlling essential processes such as growth, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Their catalytic activity, which involves the transfer of a phosphate group from ATP to specific serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues on target proteins, is tightly regulated through complex structural mechanisms [11]. The kinase domain represents a highly conserved structural unit characterized by remarkable conformational flexibility, enabling it to alternate between active and inactive states [12] [13]. Understanding the structural features of kinase domains and their dynamic behavior is paramount for rational drug design, particularly in oncology, where kinase inhibitors have emerged as transformative therapeutics [11].

This Application Note examines the conserved structural features of kinase domains and ATP-binding sites, their conformational states, and the experimental and computational methodologies essential for studying these dynamic enzymes. Framed within the context of molecular docking protocols for kinase inhibitor discovery in cancer research, this document provides detailed protocols and resources to support researchers and drug development professionals in targeting these challenging proteins.

Conserved Structural Architecture of Kinase Domains

The catalytic domain of protein kinases exhibits a conserved bilobal architecture consisting of a small N-terminal lobe (N-lobe) and a larger C-terminal lobe (C-lobe), with the ATP-binding site nestled in a deep cleft between them [11] [12]. This canonical fold is maintained across the kinome, though significant conformational diversity exists in regulatory elements and inactive states [12].

Table 1: Core Structural Elements of the Protein Kinase Domain

| Structural Element | Location | Key Features and Functions |

|---|---|---|

| N-lobe | N-terminal | Predominantly β-sheet (β1-β5), contains glycine-rich loop, αC-helix, and gatekeeper residue |

| C-lobe | C-terminal | Primarily α-helical, contains catalytic loop, activation loop, and substrate-binding platform |

| Hinge Region | Between lobes | Connects N-lobe and C-lobe, forms hydrogen bonds with adenine ring of ATP |

| Glycine-Rich Loop | N-lobe (between β1-β2) | Stabilizes ATP phosphates, often referred to as the P-loop |

| Catalytic Loop | C-lobe | Contains key residues for catalyzing phosphoryl transfer |

| Activation Loop (A-loop) | C-lobe | Dynamic regulatory element; phosphorylation often required for activation |

The ATP-Binding Site and Catalytic Machinery

The ATP-binding pocket is located at the interface between the N-lobe and C-lobe, with the adenine ring of ATP sandwiched between the lobes and forming critical hydrogen bonds with the hinge region [11]. The phosphates of ATP are positioned under the glycine-rich loop and interact with a conserved lysine residue on the β3 strand, with a divalent cation (typically Mg²⁺) connecting them to the C-lobe [11] [3].

Two evolutionarily conserved "spine" architectures regulate kinase activity by traversing both lobes and creating a cohesive structural core:

- The Regulatory Spine (R-spine) consists of four hydrophobic side chains that must align for catalytic competence [11] [12]. This spine includes residues from the αC-helix (RS3), the DFG motif (RS1), and the C-lobe (RS2 and RS4).

- The Catalytic Spine (C-spine) incorporates the adenine ring of ATP and creates a continuous hydrophobic structure that connects the N-lobe and C-lobe [11] [13].

The DFG motif (Asp-Phe-Gly) at the N-terminus of the A-loop serves as a critical regulatory switch, with its conformation determining catalytic readiness [12] [13]. The αC-helix contributes a conserved glutamate that forms a salt bridge with a lysine on β3 in active kinases, and its position ("C-helix in" or "C-helix out") significantly influences kinase activity [11].

Conformational States and Regulatory Mechanisms

Active versus Inactive States

Protein kinases function as molecular switches that transition between active ("on") and inactive ("off") states through precise structural rearrangements [11] [12]. The active conformation is highly conserved across the kinome and is characterized by several hallmark features:

- DFG motif with phenylalanine oriented inward (DFG-in)

- αC-helix positioned inward (αC-in) with salt bridge formation between Glu on αC-helix and Lys on β3 strand

- Extended and ordered activation loop that facilitates substrate binding

- Proper alignment of both regulatory and catalytic spines [11] [12] [13]

In contrast, inactive states display considerable structural diversity, with multiple distinct mechanisms for suppressing catalytic activity [12] [13]. Common inactive conformations include:

- DFG-out: The phenylalanine of the DFG motif flips outward, disrupting the ATP-binding pocket

- αC-helix out: The αC-helix shifts away from the active site, breaking the critical salt bridge

- A-loop collapse: The activation loop adopts a folded conformation that blocks substrate access

- Disrupted spine alignment: Misalignment of the R-spine and C-spine residues [11] [12]

Table 2: Classification of Major Kinase Conformational States

| State | DFG Motif | αC-helix | A-loop | Spine Alignment | Drug Targeting Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | DFG-in | αC-in (salt bridge intact) | Extended, often phosphorylated | Fully assembled | Targeted by type I inhibitors; limited selectivity |

| Type I Inactive | DFG-in | αC-out (salt bridge broken) | Variable | Disrupted | Potential for increased selectivity |

| Type II Inactive | DFG-out | αC-out | Often collapsed | Severely disrupted | Targeted by type II inhibitors; enhanced selectivity |

| Other Inactive States | Variable | Variable | Autoinhibited conformations | Variable | Opportunities for allosteric inhibition |

Allosteric Regulation and Dynamics

Kinase activity is regulated through diverse allosteric mechanisms that control the equilibrium between conformational states. Many kinases incorporate additional domains (e.g., SH2, SH3) or binding partners that modulate this equilibrium [11] [13]. The αC-β4 loop, typically 8 amino acids long with a conserved hydrophobic motif, serves as a critical hub for allosteric regulation and is a hotspot for disease-associated mutations that promote kinase activity [11].

The conformational landscape of kinases is not static but represents a dynamic ensemble of states in equilibrium. Studies on Abelson kinase (Abl) using NMR spectroscopy have revealed the presence of a ground state (predominantly active conformation) and multiple excited states (inactive conformations) that are minimally populated but critically important for regulation and drug binding [13]. Mutations that shift this equilibrium can lead to constitutive activation in cancers or confer resistance to targeted therapies [13].

Experimental Methodologies for Characterizing Kinase Conformations

Biophysical and Structural Techniques

Protocol 4.1.1: NMR Spectroscopy for Detecting Kinase Conformational States

Principle: NMR spectroscopy can detect alternate conformational states, even those populated as low as 1%, and measure the kinetics and thermodynamics of transitions between states [13].

Procedure:

- Isotope Labeling: Introduce ¹H-¹³C labels at methyl-bearing residues to provide multiple probes distributed throughout the kinase domain [13].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare kinase domain samples (0.1-0.5 mM) in appropriate buffers. For ligand-binding studies, titrate with ATP analogs or inhibitors.

- CEST Experiments: Perform Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer experiments to detect sparsely populated states:

- Apply a weak radiofrequency B₁ field (10-100 Hz) at varying offset frequencies across the spectrum

- Measure signal intensity as a function of saturation offset

- Fit data to extract chemical shifts, populations, and exchange rates of excited states [13]

- Relaxation Dispersion: Characterize chemical exchange processes on the μs-ms timescale.

- Structural Characterization: For excited states, introduce strategic mutations to increase their population and enable structure determination using conventional NMR methods [13].

Applications: Mapping conformational landscapes, identifying cryptic allosteric sites, understanding drug resistance mechanisms.

Protocol 4.1.2: Cryo-Electron Microscopy for Kinase-Ligand Complexes

Principle: Cryo-EM enables structural determination of kinase complexes without crystallization, particularly valuable for large multi-domain complexes or membrane-associated kinases [14].

Procedure:

- Sample Vitrification: Apply kinase-inhibitor complex (3-4 μL) to cryo-EM grids, blot, and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane.

- Data Collection: Collect micrographs using a high-end cryo-EM instrument (e.g., 300 keV) with automated data acquisition software.

- Image Processing:

- Perform motion correction and contrast transfer function (CTF) estimation

- Select particles through 2D and 3D classification

- Reconstruct high-resolution density maps

- Model Building and Refinement: Build atomic models into density maps and iteratively refine.

Applications: Visualizing kinase conformations in complex regulatory assemblies, characterizing allosteric modulator binding.

Computational Approaches

Protocol 4.2.1: Molecular Docking for Kinase Inhibitor Screening

Principle: Molecular docking predicts the binding mode and affinity of small molecules within kinase ATP-binding sites or allosteric pockets [14] [3].

Procedure:

- Receptor Preparation:

- Obtain kinase structure from PDB or generate homology model

- Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define protonation states

- Define binding site using grid boxes centered on regions of interest

- Ligand Preparation:

- Generate 3D structures of small molecules

- Assign appropriate bond orders and formal charges

- Energy minimize using molecular mechanics force fields

- Docking Execution:

- Select search algorithm (e.g., genetic algorithm, Monte Carlo)

- Define flexible bonds in the ligand and optionally in the receptor

- Run multiple docking simulations to ensure comprehensive sampling

- Pose Scoring and Analysis:

Applications: Virtual screening of compound libraries, lead optimization, prediction of ligand binding modes.

Protocol 4.2.2: Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Kinase Conformational Changes

Principle: MD simulations model the time-dependent motions of kinase structures, providing insights into conformational dynamics, allostery, and drug-binding mechanisms [16] [3].

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Solvate the kinase structure in explicit water molecules within a periodic boundary box

- Add counterions to neutralize system charge

- Energy Minimization:

- Perform steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient minimization to remove steric clashes

- Equilibration:

- Gradually heat system to target temperature (e.g., 310 K) over 100-500 ps

- Apply position restraints on protein heavy atoms initially, then gradually release

- Equilibrate at constant pressure (1 atm) for 1-5 ns

- Production Run:

- Run unrestrained simulation for timescales ranging from 100 ns to multiple μs

- Save coordinates at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) for analysis

- Trajectory Analysis:

Applications: Characterizing conformational transitions, understanding allosteric mechanisms, simulating drug binding and unbinding events.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Kinase Structural Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Kinase Expression Systems | Baculovirus-insect cell, Mammalian (HEK293), E. coli | Production of recombinant kinase domains with proper post-translational modifications |

| Isotope-labeled Compounds | ¹⁵N-ammonium chloride, ¹³C-glucose, ²H-water | Isotopic labeling for NMR spectroscopy; ¹H-¹³C-methyl labeling for large kinases [13] |

| ATP Analogs & Inhibitors | ATPγS, AMPPCP, Imatinib, Staurosporine, Balanol | Trapping specific conformational states; reference compounds for binding studies [13] [17] |

| Molecular Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD, MOE-Dock | Predicting ligand binding modes and affinities [14] [15] |

| MD Simulation Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, CHARMM | Simulating kinase dynamics and conformational changes [16] [3] |

| NMR Spectrometers | High-field instruments (600-900 MHz) with cryoprobes | Detecting conformational states and dynamics in solution [13] |

Kinase Activation Pathway and Computational Workflow

The activation of protein kinases follows a conserved pathway involving specific structural rearrangements of key regulatory elements, as illustrated below:

The integrated application of computational and experimental methods provides a powerful framework for kinase inhibitor discovery, as depicted in the following workflow:

The structural conservation and conformational dynamics of kinase domains present both challenges and opportunities for drug discovery. While the conserved nature of the ATP-binding site complicates achieving selectivity, the diversity of inactive conformations and allosteric regulatory mechanisms provides avenues for developing highly specific inhibitors [11] [12]. Successful targeting of kinases in oncology, exemplified by drugs like imatinib, demonstrates the therapeutic potential of structure-based approaches [13].

Future directions in kinase research and drug discovery include:

- AI-Driven Structure Prediction: Tools like AlphaFold2 are revolutionizing our ability to model kinase conformations and predict the effects of disease-associated mutations, though limitations remain in modeling the full conformational landscape [12].

- Allosteric Inhibitor Development: Targeting pockets outside the ATP-binding site offers potential for overcoming resistance and achieving greater selectivity [11] [3].

- Targeted Protein Degradation: Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) that induce kinase degradation represent a promising new modality that extends beyond traditional inhibition [3].

- Multi-Scale Simulations: Integration of enhanced sampling methods with machine learning is transforming MD simulations from descriptive tools to predictive components of the drug discovery pipeline [16] [3].

The protocols and resources detailed in this Application Note provide a foundation for leveraging structural insights to advance kinase-targeted drug discovery programs. As our understanding of kinase conformational landscapes deepens, so too will our ability to design increasingly specific and effective therapeutics for cancer and other diseases driven by kinase dysregulation.

Kinases represent one of the largest enzyme families in the human genome, comprising approximately 2% of all human genes and regulating over 30% of cellular proteins through phosphorylation [18] [19]. These enzymes catalyze the transfer of phosphate groups from ATP to specific amino acid residues on target proteins, thereby acting as molecular switches that fine-tune essential cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, metabolism, and programmed cell death [18] [3]. The human kinome is broadly classified into serine/threonine kinases, tyrosine kinases, and dual-specificity kinases based on their phosphorylation targets [18]. Protein kinase families are systematically categorized into groups including AGC, CAMK, CK1, CMGC, STE, TK, and TKL, each with distinct structural features and functional roles [18].

In cancer biology, kinases emerge as critical oncological drivers through their regulation of three fundamental processes: proliferation, apoptosis, and metastasis. Aberrant kinase activity disrupts normal cellular homeostasis, leading to uncontrolled cell growth, evasion of programmed cell death, and enhanced invasive capabilities [18]. The overexpression or constitutive activation of kinase signaling pathways is frequently observed in human cancers, resulting in abnormal cell proliferation and inhibition of both cell differentiation and apoptosis [18]. This dysregulation typically facilitates tumor growth and survival by activating downstream signaling cascades that drive cancer initiation and progression [20].

Table 1: Major Kinase Families and Their Cancer-Related Functions

| Kinase Family | Key Members | Primary Cancer Functions | Associated Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| STE | MAP4Ks, STE20 | Cell migration, apoptosis, immune modulation | JNK, Hippo, MAPK [21] |

| AGC | PKA, PKC, PKG, Akt | Cell proliferation, metabolism, survival | PI3K/Akt/mTOR [18] [22] |

| TK | EGFR, SRC, MERTK | Tumor growth, metastasis, drug resistance | MAPK, JAK/STAT [18] [23] |

| CMGC | CDKs, MAPKs | Cell cycle progression, differentiation | MAPK/ERK, CDK/Cyclin [18] [20] |

| TKL | RAF, LRRK2 | Signal transduction, proliferation | Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK [20] |

The therapeutic relevance of kinases is demonstrated by the impressive number of clinically successful kinase inhibitors, with over seventy small-molecule kinase inhibitors approved by the FDA since 2001 [3]. These targeted therapies have revolutionized cancer treatment, particularly for malignancies driven by specific kinase alterations. However, challenges remain in achieving selectivity, overcoming drug resistance, and effectively targeting the complex network of kinase signaling cascades that operate through cross-talk and compensatory mechanisms [19] [3].

Key Kinase Signaling Pathways in Oncology

MAPK Cascade

The Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathway represents a complex interconnected kinase signaling cascade that is commonly mutated and targeted in cancer [20]. This pathway initiates when growth factors (e.g., epidermal growth factor) bind the extracellular domains of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as EGFR and PDGFR, stimulating their signal transduction cascades [20]. The canonical MAPK cascade includes the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, where Ras activates Raf, a serine/threonine kinase that relays signals to the MAPK cascade [20]. Raf then activates MEK, which subsequently activates ERK, which phosphorylates proteins in both the cytoplasm and nucleus [20].

Upon translocation to the nucleus, ERK promotes the transcription of genes by phosphorylating and activating transcription factors, culminating in the expression of target genes that regulate proliferation, differentiation, and survival [20]. The MAPK signaling pathway exemplifies how kinases can initiate with single, specific substrates and culminate in activating multiple, specific cellular programs across diverse cell types and states [20]. The effectiveness of this allosteric signaling relay stems from coordinated speed and precision, with the kinases lodged in dense molecular condensates at the membrane adjoining RTK clusters, where their assemblies promote specific, productive signaling [20].

PI3K/AKT/mTOR Cascade

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR cascade serves as another major drug target in cancer, primarily tasked with metabolic signaling and protein synthesis in cell growth [20]. This pathway can be activated via RTKs and Ras, promoting cell survival, growth, and proliferation in response to extracellular stimuli [20]. PI3K, a lipid kinase, phosphorylates the signaling lipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), an action reversed by phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), with both catalytic actions occurring at the membrane [20].

In turn, phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) binds to PIP3 through its C-terminal Pleckstrin homology (PH) domain with high affinity, which is essential for PDK1 to phosphorylate and activate AKT kinase, which also binds PIP3 through its PH domain [20]. AKT is subsequently phosphorylated by both PDK1 and mTORC2, the next kinase in the cascade [20]. Thus, PI3K, PTEN, PDK1, and AKT are all recruited to the membrane through the signaling lipid—either unphosphorylated (PIP2; PI3K) or phosphorylated (PIP3; PTEN, PDK1, and AKT) [20]. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway exhibits extensive cross-talk with other signaling pathways, including MAPK, creating a complex regulatory network that coordinates cellular responses to growth signals and metabolic cues [20].

Table 2: Core Components of Oncogenic Kinase Signaling Pathways

| Pathway Component | Kinase Class | Biological Function | Cancer Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs) | Transmembrane receptors | Initiate signaling cascades upon ligand binding | Overexpression in multiple cancers; drive proliferation [18] [20] |

| Ras | Small GTPase | Transmits signals from RTKs to downstream effectors | Frequently mutated in cancers; constant activation [20] |

| RAF | Serine/Threonine Kinase | Phosphorylates MEK in MAPK pathway | Mutated in melanoma, CRC; hyperactive signaling [24] [20] |

| MEK | Dual-specificity Kinase | Phosphorylates ERK in MAPK pathway | Key signaling node; targeted in BRAF-mutant cancers [24] [20] |

| ERK | Serine/Threonine Kinase | Regulates transcription factors and cytoplasmic targets | Controls proliferation and survival genes [24] [20] |

| PI3K | Lipid Kinase | Generates PIP3 at membrane | Frequently mutated; activates AKT signaling [20] |

| AKT | Serine/Threonine Kinase | Promotes cell survival and growth | Overactive in many cancers; inhibits apoptosis [18] [20] |

| mTOR | Serine/Threonine Kinase | Integrates nutrient and growth signals | Hyperactive in cancer; drives protein synthesis [18] [20] |

Emerging Pathways: MAP4K and Hippo Signaling

Beyond the classical MAPK and PI3K pathways, emerging research has highlighted the importance of additional kinase families in cancer biology. The MAP4K family, consisting of seven kinases (MAP4K1-7), plays crucial roles in regulating diverse cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis [21]. Recent studies have demonstrated their involvement in multiple signaling pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinase, Jun N-terminal kinase, and Hippo pathways, implicating them in cancer, autoimmune disorders, metabolic diseases, and neurodegenerative conditions [21].

MAP4K proteins have demonstrated significant roles in cancer development and progression, including tumor growth, metastasis, and immune modulation [21]. For instance, MAP4K1 functions as a negative regulator of T-cell receptor signaling, and its inhibition enhances T-cell activation and improves immune responses against tumors [21]. Conversely, MAP4K4 is linked to cancer cell movement and growth, influencing metastatic potential [21]. These kinases can act as both promoters and suppressors of cancer depending on cellular context, making them potential targets for novel cancer therapies [21].

Molecular Docking Protocols for Kinase Inhibitor Development

Computational Framework and Workflow

The development of kinase inhibitors has become a cornerstone of targeted cancer therapy, with computational methods playing an increasingly vital role in accelerating drug discovery pipelines. Structure-based drug discovery, utilizing molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, has emerged as a central strategy for identifying and optimizing kinase inhibitors [3]. These in silico approaches address the challenges of traditional high-throughput screening, which often incurs high costs, is time-consuming, and lacks sufficient coverage of chemical space [3].

A novel framework for kinase-inhibitor binding affinity prediction integrates self-supervised graph contrastive learning with multiview molecular graph representation and structure-informed protein language models to effectively extract features [24]. This approach, known as Kinhibit, employs a feature fusion method to optimize the integration of inhibitor and kinase features, achieving impressive accuracy of 92.6% in inhibitor prediction tasks for three MAPK signaling pathway kinases: Raf protein kinase, MEK, and ERK [24]. The framework demonstrates even higher accuracy (92.9%) on the combined MAPK-All dataset, providing promising tools for drug screening and biological sciences [24].

The Kinhibit framework comprises two primary processes: pretraining and fine-tuning [24]. The pretraining phase focuses on developing a robust small-molecule encoder through a graph contrastive learning strategy, where input ligands are represented by multiple SMILES strings transformed into molecular graph representations with distinct atomic coordinates and spatial conformations using the RDKit toolkit [24]. The resulting molecular graphs are fed into a small-molecule encoder based on the E(n) Equivariant Graph Neural Network, which learns high-dimensional ligand representations by minimizing contrastive loss [24]. During fine-tuning, the weights of both the molecular encoder and the ESM-S-based encoder remain frozen, preserving their pretrained representations, while projection layers and inhibitor predictors are fine-tuned on the training set [24].

Practical Protocol: Kinase-Inhibitor Docking

Objective: To identify and characterize potential small-molecule inhibitors targeting kinase domains using molecular docking and dynamics simulations.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Kinase crystal structure (PDB format)

- Small molecule compound library (SDF or MOL2 format)

- Molecular docking software (AutoDock Vina, MOE, or similar)

- Molecular dynamics simulation package (AMBER, GROMACS, or similar)

- Visualization software (PyMOL, Chimera)

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

Protein Preparation:

- Retrieve kinase crystal structure from Protein Data Bank (e.g., PDB ID: 6BKW for BTK kinase) [19]

- Remove water molecules and heteroatoms not involved in catalytic activity

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign appropriate protonation states for ionizable residues

- Energy minimization using force field parameters to relieve steric clashes

Ligand Library Preparation:

- Obtain compound structures from databases (ZINC, ChEMBL, or in-house collections)

- Generate 3D coordinates and optimize geometry using molecular mechanics

- Assign atomic charges and determine rotatable bonds

- Convert to appropriate format for docking simulations

Molecular Docking Execution:

- Define binding site coordinates based on known ATP-binding site or allosteric pockets

- Set grid parameters to encompass the entire binding pocket with sufficient margin

- Perform docking simulations using appropriate sampling algorithms

- Generate multiple poses per ligand to explore binding orientations

Pose Scoring and Evaluation:

- Rank compounds based on docking scores and binding affinity predictions

- Analyze interaction patterns (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, salt bridges)

- Assess complementarity with key binding site residues

- Select top candidates for further refinement

Molecular Dynamics Validation:

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in explicit water molecules

- Add counterions to neutralize system charge

- Energy minimization and equilibration using standard protocols

- Production run (typically 50-100 ns) with stable temperature and pressure

- Analyze trajectory for stability, binding mode conservation, and interaction persistence

Binding Free Energy Calculations:

- Perform MM-PBSA or MM-GBSA calculations on stable trajectory segments

- Decompose energy contributions per residue to identify key interactions

- Compare calculated binding affinities with experimental data when available

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If docking poses show inconsistent orientation, consider increasing sampling parameters and using different search algorithms

- For unstable complexes during MD simulations, check initial structure quality and ensure proper system equilibration

- When binding affinity predictions disagree with experimental values, validate force field parameters and solvation models

Advanced Applications: Pocket-Aware Inhibitor Design

Recent advances in kinase inhibitor development have explored targeting alternative binding sites beyond the conserved ATP-binding pocket. The structurally diverse and less conserved J pocket has emerged as a promising target for developing next-generation inhibitors with high selectivity and low molecular weight [19]. Although recent structural studies on AURKA first reported a hydrophobic pocket in the J-loop region that can be exploited by small molecules, similar structural sites had been identified in other kinase families, such as the PIF-binding pocket in PDK1 and related AGC kinases [19].

The catalytic domain of BTK also harbors a similar J-pocket conformation, located on the posterior side of the catalytic domain, oriented opposite to the ATP-binding site [19]. Inhibitors can form stable thioether covalent bonds with BTK Cys481 through sulfur-Michael addition, accompanied by local conformational rearrangements around the active site [19]. Multi-omics and computational studies have demonstrated that inhibitor occupancy and covalent modification can modulate the in/out equilibrium of the αC-helix and the conserved Lys–Glu salt bridge via an allosteric network, thereby biasing the kinase conformation toward an inactive state [19].

Generative deep learning approaches have shown promise in addressing the challenges of J pocket inhibitor development [19]. These models can integrate multidimensional structural data to accurately capture dynamic conformational changes of kinase pockets, enabling the construction of high-precision models for predicting drug-pocket binding modes [19]. Deep reinforcement learning algorithms establish strategic exploration pathways within chemical space, allowing precise perception and generation of molecular structures that form stable interactions with key residues in alternative binding pockets [19].

Table 3: Computational Methods for Kinase Inhibitor Development

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Applications | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Rigid docking, Flexible docking, Induced fit | Binding pose prediction, Virtual screening | docking score, RMSD, interaction energy [23] [3] |

| Molecular Dynamics | Explicit solvent MD, Enhanced sampling | Binding stability, Conformational dynamics, Residence time | RMSD, RMSF, H-bonds, binding free energy [23] [3] |

| Machine Learning | Graph neural networks, Protein language models | Binding affinity prediction, De novo design | Accuracy, AUC, RMSE [24] |

| Free Energy Calculations | MM-PBSA, MM-GBSA, FEP | Binding affinity estimation, Lead optimization | ΔG binding, per-residue energy decomposition [23] [3] |

| Generative Models | VAEs, GANs, Reinforcement learning | Novel inhibitor design, Scaffold hopping | Diversity, synthetic accessibility, binding affinity [19] |

Experimental Validation of Kinase Inhibitors

Biochemical and Cellular Assays

Following computational predictions, experimental validation is essential to confirm the efficacy and mechanism of action of potential kinase inhibitors. Standard experimental protocols include:

Kinase Inhibition Assay:

- Prepare kinase reaction buffer (e.g., 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM MgCl2)

- Incubate kinase with varying concentrations of inhibitor (typically 0.1 nM - 100 μM) for 15-30 minutes at room temperature

- Initiate reaction by adding ATP mix (including [γ-32P]ATP for radiometric assays or ATP with fluorescently-labeled substrate for fluorescence-based assays)

- Terminate reaction after appropriate incubation time and quantify phosphorylation levels

- Calculate IC50 values using nonlinear regression of inhibition curves

Cell-Based Viability and Proliferation Assays:

- Seed cancer cell lines (e.g., T47D for breast cancer, A549 for non-small-cell lung carcinoma) in 96-well plates at optimal density [25]

- Treat cells with serially diluted inhibitors for 48-72 hours

- Assess viability using MTT, MTS, or Alamar Blue assays according to manufacturer protocols

- Determine GI50 values (concentration causing 50% growth inhibition) through dose-response analysis

- Include healthy control cells (e.g., human skin fibroblasts) to assess selectivity [25]

Cell Cycle Analysis:

- Treat cells with inhibitors for 24-48 hours

- Harvest cells and fix in 70% ethanol at -20°C for at least 2 hours

- Stain with propidium iodide solution (50 μg/mL PI, 100 μg/mL RNase A in PBS) for 30 minutes at room temperature

- Analyze DNA content by flow cytometry

- Quantify percentage of cells in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases

Apoptosis Assay:

- Stain cells with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide using commercial apoptosis detection kits

- Analyze by flow cytometry to distinguish early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-), late apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI+), and necrotic (Annexin V-/PI+) populations

- Confirm apoptosis through additional markers like caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage

Protocol: Evaluation of Anticancer Activity in Breast Cancer Models

Purpose: To assess the therapeutic potential of kinase inhibitors in breast cancer models, with emphasis on proliferation, apoptosis, and metastasis-related phenotypes.

Materials:

- Breast cancer cell lines (e.g., T47D, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231)

- Normal breast epithelial cells (e.g., MCF-10A) as control

- Test compounds dissolved in DMSO (final concentration ≤0.1%)

- Cell culture reagents and plasticware

- Western blot equipment and antibodies for signaling pathway analysis

- Transwell chambers for migration/invasion assays

Methodology:

Proliferation and Dose-Response Analysis:

- Plate cells in 96-well plates at 3-5 × 10³ cells/well and allow to adhere overnight

- Treat with 8-10 concentrations of inhibitor (typically 1 nM - 100 μM) in triplicate

- Incubate for 72 hours, then assess viability using MTS assay

- Measure absorbance at 490 nm and calculate percentage viability relative to DMSO-treated controls

- Generate dose-response curves and determine IC50 values using four-parameter logistic fit

Clonogenic Survival Assay:

- Seed cells at low density (200-500 cells/well) in 6-well plates

- Treat with inhibitors at IC50 and IC75 concentrations for 10-14 days

- Fix colonies with methanol:acetic acid (3:1) and stain with 0.5% crystal violet

- Count colonies containing >50 cells and calculate plating efficiency and surviving fraction

Migration and Invasion Assays:

- For migration assays, seed 5 × 10⁴ serum-starved cells in upper chamber of Transwell inserts with 8 μm pores

- For invasion assays, coat inserts with Matrigel (1 mg/mL) before seeding cells

- Add complete medium with 10% FBS as chemoattractant in lower chamber

- Incubate for 16-24 hours, then fix and stain migrated cells on lower membrane surface

- Count cells in 5 random fields per insert under microscope

Western Blot Analysis of Signaling Pathways:

- Treat cells with inhibitors for 2-24 hours at IC50-IC90 concentrations

- Lyse cells in RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors

- Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membranes

- Probe with antibodies against phosphorylated and total forms of kinases (e.g., p-ERK, ERK, p-AKT, AKT)

- Detect using enhanced chemiluminescence and quantify band intensities

3D Spheroid Invasion Assay:

- Seed cells in ultra-low attachment plates to form spheroids

- Embed spheroids in collagen matrix after 3-5 days

- Treat with inhibitors and monitor invasive outgrowth over 7-14 days

- Measure spheroid area and invasive protrusion length using image analysis software

Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Compare IC50 values across different cell lines to assess potency and selectivity

- Evaluate correlation between pathway inhibition (western blot) and functional responses

- Assess statistical significance using ANOVA with post-hoc tests for multiple comparisons

- Consider combination indices when testing inhibitor combinations

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinase Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase Inhibition Assay Kits | ADP-Glo, Kinase-Glo | Luminescent detection of kinase activity | High-throughput screening of kinase inhibitors [3] |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | p-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), p-AKT (Ser473) | Detection of kinase activation states | Western blot, immunofluorescence for pathway analysis [18] |

| Cell Viability Assays | MTT, MTS, CellTiter-Glo | Quantification of cell proliferation and viability | Dose-response studies for inhibitor efficacy [25] |

| Apoptosis Detection Kits | Annexin V FITC/PI, Caspase-3/7 assays | Identification and quantification of apoptotic cells | Mechanism of action studies for kinase inhibitors [18] [25] |

| Proteomic Tools | Phospho-tyrosine antibodies, Kinase arrays | Global analysis of kinase signaling networks | Identification of downstream targets and pathway activation [21] |

| Molecular Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, MOE, Glide | Prediction of inhibitor binding modes and affinities | Virtual screening and rational drug design [23] [19] [3] |

| MD Simulation Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Analysis of dynamic behavior of kinase-inhibitor complexes | Binding stability and mechanism studies [23] [19] [3] |

Kinases undeniably serve as critical oncological drivers through their regulation of proliferation, apoptosis, and metastasis. The intricate signaling networks involving MAPK, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and emerging pathways like MAP4K and Hippo signaling represent promising therapeutic targets in oncology. The development of computational frameworks for kinase inhibitor discovery, particularly molecular docking protocols and dynamics simulations, has significantly accelerated the identification and optimization of targeted therapies.

Future directions in kinase research include addressing the persistent challenges of drug resistance and selectivity. Combining allosteric inhibitors with traditional ATP-competitive compounds may overcome resistance mutations, while bifunctional degraders such as PROTACs offer alternative strategies for targeting kinase function [3]. Advances in structural biology, including cryo-EM, will provide higher-resolution insights into kinase conformations and activation mechanisms, facilitating more rational drug design [3]. Additionally, machine learning and artificial intelligence approaches will continue to transform kinase drug discovery, enabling more accurate prediction of binding affinities and generation of novel chemotypes with improved properties [24] [19].

The integration of computational predictions with robust experimental validation remains paramount for translating kinase research into clinical advances. As our understanding of kinase biology deepens and technological capabilities expand, targeting these oncological drivers will continue to yield innovative therapeutic strategies for cancer treatment.

Application Note: Clinical Efficacy of Kinase Inhibitors in Advanced Cancers

Protein kinases represent a pivotal family of enzymes that regulate essential cellular processes through phosphorylation mechanisms. With over 50 FDA-approved kinase inhibitors currently available for clinical use, these targeted therapies have revolutionized cancer treatment by addressing specific molecular drivers of oncogenesis [26]. The evolutionary journey from first-generation to third-generation kinase inhibitors demonstrates remarkable progress in overcoming drug resistance and improving patient outcomes across various malignancies, particularly in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [26] [27].

Clinical Case Studies

Table 1: Clinical Response to Selected Kinase Inhibitors in Different Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Kinase Inhibitor | Study Details | Clinical Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Lung Adenocarcinoma (EGFR T790M+) | Osimertinib | 90 patients, retrospective study | ORR: 70.3%, mPFS: 12.30 months, mOS: 37.27 months | [27] |

| EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC | Osimertinib + Chemotherapy | Phase 3 trial, 279 patients | Median OS: 47.5 months | [28] |

| EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC | Osimertinib Monotherapy | Phase 3 trial, 278 patients | Median OS: 37.6 months | [28] |

| CML (Chronic Phase) | Imatinib 400 mg/d | Phase 3 trial, 157 patients | MMR at 12 months: 40% | [29] |

| CML (Chronic Phase) | Imatinib 800 mg/d | Phase 3 trial, 319 patients | MMR at 12 months: 46% | [29] |

| Advanced Lung Cancer (Case Study) | Sequential EGFR Inhibitors | Single patient, 18-year follow-up | Ongoing response with osimertinib after 7 years | [30] |

Osimertinib in NSCLC: Mechanisms and Resistance

Osimertinib represents a third-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor that selectively targets both EGFR-TKI sensitizing mutations and the T790M resistance mutation while sparing wild-type EGFR [27]. This specificity translates to enhanced efficacy and reduced toxicity compared to earlier generation inhibitors. The drug has demonstrated significant clinical activity even in challenging clinical scenarios, including patients with central nervous system involvement [31]. However, resistance mechanisms inevitably emerge, leading to disease progression typically after a median of 10.41 months in advanced lung adenocarcinoma patients [27]. Ongoing research focuses on combination therapies and retreatment strategies to overcome this resistance, with recent studies showing that osimertinib retreatment following interim chemotherapy can provide additional disease control in approximately 53% of patients [31].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Clinical Efficacy Assessment of Kinase Inhibitors in NSCLC

Patient Selection and Treatment Administration

- Inclusion Criteria: Patients with histologically confirmed advanced NSCLC (Stage IV) with documented EGFR mutations (exon 19 deletion or L858R mutation) who have progressed after first-line EGFR-TKI treatment [27]. T790M mutation status should be confirmed via biopsy or liquid biopsy.

- Exclusion Criteria: Patients with uncontrolled systemic diseases, inadequate organ function, or previous exposure to third-generation EGFR-TKIs.

- Dosing Regimen: Administer osimertinib at 80 mg orally once daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity [27]. For combination therapy, add pemetrexed (500 mg/m²) and cisplatin (75 mg/m²) or carboplatin (pharmacologically guided dose) every 3 weeks [28].

Efficacy Monitoring and Response Assessment

- Radiological Assessment: Perform computed tomography (CT) scans at baseline and every 6-8 weeks thereafter. Brain MRI should be conducted for patients with known or suspected brain metastases [27].

- Response Criteria: Evaluate treatment response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1, categorizing responses as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD) [27].

- Key Metrics: Calculate objective response rate (ORR) as (CR + PR)/total cases × 100% and disease control rate (DCR) as (CR + PR + SD)/total cases × 100% [27].

- Survival Parameters: Monitor progression-free survival (PFS) from treatment initiation to disease progression or death, and overall survival (OS) from treatment initiation to death from any cause [27].

Safety and Toxicity Management

- Assessment Schedule: Conduct routine blood tests, liver function tests, and renal function tests at baseline, weekly during the first month, and monthly thereafter [27].

- Grading System: Evaluate adverse events according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0 [27].

- Dose Modification Guidelines: Implement dose reductions or temporary treatment interruptions for Grade ≥3 adverse events. For osimertinib-specific toxicities such as diarrhea (occurring in 28.9% of patients) or rash (24.4%), provide appropriate symptomatic management [27].

Protocol 2: Molecular Docking for Kinase Inhibitor Design

Protein Preparation and Binding Site Characterization

- Structure Retrieval: Obtain three-dimensional structures of target kinases (e.g., EGFR, PI3Kα) from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 4JPS for PI3Kα) [32]. The characteristic kinase domain consists of a small N-lobe dominated by β-strands and one conserved α-helix, and a large α-helical C-lobe connected by a hinge region forming the catalytic cleft where ATP binds [26].

- Binding Site Identification: Define the active site by identifying key residues including the conserved Lys/Glu/Asp/Asp (K/E/D/D) signature, DFG motif (Asp-Phe-Gly) in the activation loop, and the glycine-rich GxGxxG motif (P-loop) between β1 and β2 strands that folds over the nucleotide [26].

- Structure Optimization: Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and remove crystallographic water molecules except those participating in key hydrogen-bonding interactions within the active site [32].

Compound Library Preparation and Virtual Screening

- Library Selection: Curate compound libraries from protein kinase inhibitor databases or design hybrid compounds comprising privileged scaffolds such as pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine and isatin linked by hydrazine bridges [33].

- Ligand Preparation: Generate 3D structures of library compounds, perform energy minimization using molecular mechanics force fields, and assign appropriate protonation states at physiological pH [33] [32].

- Docking Protocol: Conduct high-throughput virtual screening using molecular docking software with validated parameters. Employ scoring functions to predict binding affinities and prioritize hits for further analysis [32].

Binding Affinity Calculation and Validation

- Energy Calculations: Perform Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) calculations to estimate binding free energies of protein-ligand complexes [32].

- Induced Fit Docking: Account for protein flexibility through induced fit docking protocols to model conformational changes upon ligand binding [32].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Conduct MD simulations (100-200 ns) in explicit solvent to assess complex stability, analyze root mean square deviation (RMSD), and identify key interaction dynamics [32].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: EGFR Signaling & Drug Inhibition Pathway

Diagram 2: Computational Drug Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Kinase Inhibitor Development

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Kinase Expression Systems | Production of purified kinase domains for structural and biochemical studies | Catalytic domains of EGFR, PI3Kα, Bcr-Abl expressed in insect or mammalian cells |

| Crystallography Platforms | Determination of 3D protein-ligand complex structures | X-ray crystallography with PDB structures (e.g., 4JPS for PI3Kα) [32] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Prediction of ligand binding poses and affinity | AutoDock, Glide, GOLD for structure-based virtual screening [32] |

| Compound Libraries | Source of potential kinase inhibitor candidates | Protein kinase inhibitor database; pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-based hybrids [33] [32] |

| MD Simulation Packages | Assessment of protein-ligand complex stability over time | GROMACS, AMBER for 100-200 ns simulations in explicit solvent [32] |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | Evaluation of drug-like properties and toxicity | SwissADME, pkCSM for absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity profiling [32] |

The clinical success stories from imatinib to osimertinib exemplify the transformative impact of targeted kinase inhibitors in oncology. These advances have been facilitated by integrated approaches combining structural biology, computational drug design, and robust clinical validation protocols. The continued refinement of molecular docking methodologies and clinical application frameworks promises to accelerate the development of next-generation kinase inhibitors with enhanced efficacy and specificity, ultimately improving outcomes for cancer patients worldwide.

The escalating global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis necessitates innovative therapeutic strategies. One in six bacterial infections worldwide is now resistant to common antibiotics, with resistance rising in over 40% of monitored pathogen-drug combinations [34]. This application note explores the targeting of bacterial kinases, particularly eukaryotic-like serine/threonine kinases (eSTKs), as a novel approach to combat AMR. We detail computational and experimental protocols, repurposing molecular docking frameworks from oncology to design inhibitors that disrupt bacterial virulence, persistence, and resistance mechanisms. Within the context of a broader thesis on kinase inhibitors in cancer research, this document provides actionable methodologies for expanding this expertise into infectious disease applications.

Antimicrobial resistance represents a catastrophic threat to global health, directly causing an estimated 1.27 million deaths annually and contributing to nearly five million more [35]. Gram-negative bacteria, including Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, pose a severe threat, with more than 55% of K. pneumoniae isolates resistant to first-line cephalosporin antibiotics [34]. This dire landscape mandates the exploration of unconventional antibacterial targets.

Bacterial kinases, especially eukaryotic-like serine/threonine kinases (eSTKs), have emerged as promising candidates. These kinases regulate critical bacterial processes, including:

- Cell wall homeostasis and metabolism: Essential for bacterial growth and integrity [1].

- Virulence factor expression: Controls the production of molecules that enable infection and pathogenesis [36].

- Antibiotic tolerance and resistance: Mediates survival mechanisms in the presence of antibiotics [1] [36].

The structural and mechanistic conservation between bacterial eSTKs and human kinases provides a unique opportunity. Researchers can leverage the extensive knowledge, computational tools, and chemical libraries developed for human kinase inhibitor discovery in cancer research and apply them to antibacterial development [1] [36]. This strategy of target repurposing can significantly accelerate the discovery timeline.

Table 1: Key Bacterial Serine/Threonine Kinases and Their Therapeutic Relevance

| Kinase Target | Bacterial Pathogen | Biological Function | Role in Resistance/Virulence | Inhibitor Adjuvant Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PASTA kinases (e.g., Stk1) | Staphylococcus aureus | Cell wall metabolism, signal transduction | Regulates β-lactam susceptibility [36] | Re-sensitizes MRSA to β-lactams [36] |

| KpnK | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Oxidative stress response | Modulates β-lactam susceptibility [1] | Potential for combination therapies |

| HipA homologues | Various (e.g., E. coli) | Toxin-antitoxin system | Mediates antibiotic tolerance (e.g., to ciprofloxacin) [1] | Potential to counter bacterial persistence |

| PknB | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Regulation of cell growth and division | Critical for cell wall synthesis and survival | Validated target for anti-tuberculosis drugs |

Table 2: Global Antibiotic Resistance Statistics Underpinning the Need for Novel Targets

| Pathogen | Resistance to Key Antibiotic Class | Global Resistance Rate | Regional Highlight (Highest Burden) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Third-generation cephalosporins | >55% [34] | Exceeds 70% in the African Region [34] |

| Escherichia coli | Third-generation cephalosporins | >40% [34] | - |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Methicillin (MRSA) | Widespread, significant healthcare costs [37] | - |

| Multiple Gram-negative bacteria | Carbapenems (last-resort) | Increasing, becoming more frequent [34] | - |

Computational Protocol: Molecular Docking for Bacterial Kinase Inhibitors

This protocol adapts standard molecular docking pipelines from human kinase research for bacterial kinase targets, focusing on identifying inhibitors that can serve as antibiotic adjuvants.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Target and Ligand Preparation

- Target Selection and Retrieval: Identify a bacterial kinase of interest (e.g., Stk1 from S. aureus). Retrieve its three-dimensional structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). If an experimental structure is unavailable, employ homology modeling using tools like MODELLER, with a human kinase structure (e.g., CDK4/6) as a template [1] [15].

- Protein Preparation: Process the protein structure by removing native ligands and water molecules, adding hydrogen atoms, and assigning partial charges using tools like UCSF Chimera or the Protein Preparation Wizard in Maestro. Critical: Define the binding site, typically the ATP-binding pocket or an identified allosteric site [15].

- Ligand Library Curation: Compile a library of small molecules for screening. For repurposing, start with FDA-approved human kinase inhibitors (e.g., from the Approved Oncology Drugs Set). Prepare ligands by energy minimization and conversion into a suitable format (e.g., MOL2 or PDBQT), ensuring correct tautomeric and protonation states [36] [15].

Step 2: Molecular Docking Execution

- Software Selection: Employ docking software such as AutoDock Vina, Glide, or GOLD. These tools are well-established in kinase inhibitor discovery for their accuracy and performance [15].

- Grid Generation: Define a search space (grid box) encompassing the entire binding pocket of the target kinase. The grid should be sufficiently large to allow ligand movement and conformational sampling.

- Docking Parameters: Utilize a search algorithm (e.g., Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm in AutoDock) to generate multiple ligand poses. Set the number of runs and poses per molecule to ensure comprehensive sampling of the binding mode [15].

Step 3: Post-Docking Analysis and Validation

- Pose Scoring and Ranking: Rank the generated ligand poses based on a scoring function (e.g., Vina score, GlideScore) that estimates the binding affinity. The pose with the most favorable (lowest) score is typically considered the predicted binding mode [15].

- Pose Analysis: Visually inspect the top-ranked poses using molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, UCSF Chimera). Analyze key interactions, such as hydrogen bonds with the kinase's hinge region and hydrophobic contacts within the binding pocket.

- Validation with MD Simulations: Refine and validate the top docking poses using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., with GROMACS or AMBER). This step assesses the stability of the protein-ligand complex over time and provides a more accurate calculation of binding free energy using methods like MM-PBSA [1].

Experimental Validation Protocol: Assessing Efficacy

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Primary Antibacterial Screening

- Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assay: Perform a standard broth microdilution assay according to CLSI guidelines to determine the intrinsic antibacterial activity of the compound.

- Prepare a dilution series of the test compound in a 96-well plate containing Mueller-Hinton broth.

- Inoculate each well with ~5 × 10^5 CFU/mL of the target bacterial strain (e.g., MRSA).

- Incubate at 37°C for 16-20 hours. The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration that completely inhibits visible bacterial growth [36] [38].

Step 2: Adjuvant Effect Screening

- Checkerboard Synergy Assay: For compounds lacking intrinsic activity but predicted to inhibit resistance mechanisms, test their ability to potentiate conventional antibiotics.

- Dispense a fixed, sub-inhibitory concentration of the kinase inhibitor (e.g., 7 µg/mL) in a 96-well plate.

- Create a two-dimensional dilution series of a partner antibiotic (e.g., oxacillin).

- Inoculate with bacteria and incubate as above.

- Calculate the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) index to quantify synergy. An FIC index ≤0.5 indicates significant synergy, suggesting the compound resensitizes the bacterium to the antibiotic [36].

Step 3: Cytotoxicity and Host-Directed Effect Assessment

- Cell Viability Assays: To ensure selectivity and identify host-directed therapeutics, assess compound toxicity against mammalian cell lines (e.g., HEK-293 or HeLa).

- Treat cells with a range of compound concentrations for 24-48 hours.

- Measure cell viability using colorimetric assays like MTT or XTT.

- A compound is considered non-cytotoxic if it maintains >80% host cell viability at concentrations effective against the bacteria [39].

- Intracellular Infection Models: For pathogens like S. aureus, use fluorescence-based high-throughput assays to quantify the compound's effect on bacterial invasion and intracellular survival within host cells, as described in [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Bacterial Kinase Research and Inhibitor Screening