CoMFA vs. CoMSIA: A Comparative Analysis of Predictive Accuracy in Cancer Drug Design

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two cornerstone 3D-QSAR techniques—Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA)—in the context of cancer drug discovery.

CoMFA vs. CoMSIA: A Comparative Analysis of Predictive Accuracy in Cancer Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two cornerstone 3D-QSAR techniques—Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA)—in the context of cancer drug discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of both methods, details their practical application against specific cancer targets like IDO1, CDK2, and tubulin, and offers strategic guidance for troubleshooting and optimizing model robustness. By synthesizing validation metrics and direct performance comparisons from recent studies, this review serves as a practical guide for selecting and applying these computational tools to enhance the predictive accuracy and efficiency of designing novel oncology therapeutics.

Understanding CoMFA and CoMSIA: Core Principles and Field Descriptors in QSAR

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) is a foundational 3D-QSAR method that correlates the biological activity of molecules with their spatially-dependent steric and electrostatic properties. This guide objectively compares CoMFA's performance and methodology against its successor, Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), focusing on their application and predictive accuracy in cancer targets research.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) operates on the principle that the biological activity of a molecule is dependent on its interaction with a receptor, which is largely governed by non-covalent forces. It quantitatively describes these interactions by mapping two key molecular fields around a set of aligned molecules. The steric field is calculated using the Lennard-Jones potential, which describes the repulsive and attractive forces between atoms at various distances. The electrostatic field is calculated using a Coulombic potential, which describes the interaction between charged particles [1] [2].

CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis) was developed to address some inherent limitations of CoMFA. Instead of the Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials, CoMSIA uses a Gaussian function to calculate similarity indices for several physicochemical properties. This approach avoids the abrupt changes in potential energy near the molecular surface that occur in CoMFA and eliminates the need for arbitrary energy cut-offs. In addition to steric and electrostatic fields, CoMSIA typically incorporates hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields, providing a more holistic view of potential ligand-receptor interactions [3] [1].

Comparative Performance Data in Cancer Research

The predictive accuracy of CoMFA and CoMSIA is quantitatively assessed using statistical metrics. The table below summarizes key parameters from recent cancer-related 3D-QSAR studies, illustrating the performance of both methods.

Table 1: Comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA Model Performance in Cancer Drug Discovery

| Study Focus (Compound Class) | Method | Cross-validated R² (q²) | Non-cross-validated R² (r²) | Predictive R² (r²pred) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thioquinazolinones (Breast Cancer) | CoMFA | 0.669 | 0.991 | Information Missing | [4] |

| CoMSIA | 0.682 | 0.994 | Information Missing | [4] | |

| Phenylindole Derivatives (Breast Cancer) | CoMSIA/SEHDA | 0.814 | 0.967 | 0.722 | [5] |

| Ionone-based Chalcones (Prostate Cancer) | CoMFA | 0.527 | 0.636 | 0.621 | [6] |

| CoMSIA | 0.550 | 0.671 | 0.563 | [6] | |

| α1A-AR Antagonists (Prostate Cancer) | CoMFA | 0.840 | Information Missing | 0.694 | [7] |

| CoMSIA | 0.840 | Information Missing | 0.671 | [7] |

The cross-validated coefficient (q²) indicates the internal predictive power of the model, with values above 0.5 generally considered acceptable [6]. The non-cross-validated coefficient (r²) measures the goodness-of-fit, while the predictive r² (r²pred) is a crucial metric for evaluating the model's ability to predict the activity of external test set compounds [7] [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The development of robust CoMFA and CoMSIA models follows a meticulous workflow. Adherence to this protocol is critical for generating reliable and predictive models.

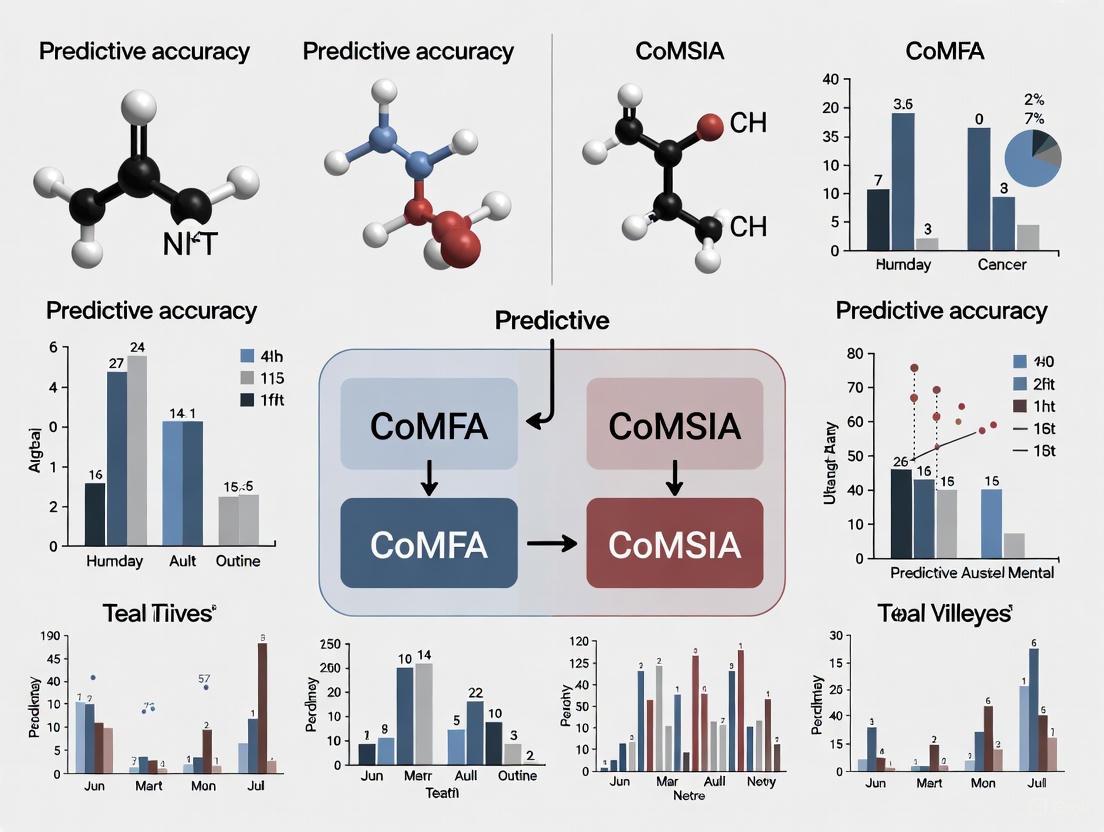

Figure: 3D-QSAR Model Development Workflow

Key Procedural Steps

- Data Set Preparation and Molecular Modeling: A series of molecules with known biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀ or Kᵢ) are compiled. Their 3D structures are sketched and energy-minimized using a molecular mechanics force field, such as the Tripos standard force field, and Gasteiger-Hückel partial atomic charges are assigned [4] [5] [6].

- Molecular Alignment: This is the most critical step. All molecules are structurally aligned to a common template, often the most active compound, based on a presumed pharmacophore or a common substructure, to ensure they are in a comparable orientation and conformation [4] [7] [6].

- Field Calculation (The Key Differentiator):

- In CoMFA, a probe atom (typically an sp³ carbon with a +1 charge) is placed at intersections of a 3D grid that encompasses the aligned molecules. At each point, the steric energy is computed using the Lennard-Jones 6-12 potential and the electrostatic energy using Coulomb's law [1] [2].

- In CoMSIA, the same probe is used, but instead of calculating interaction energies, it calculates similarity indices using a Gaussian function for up to five fields: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor [3] [1] [2].

- Statistical Analysis and Validation: Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is used to correlate the field values (independent variables) with the biological activity data (dependent variable). The model is first validated internally using leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation to obtain the q² value. Its true predictive power is then tested by predicting the activity of an external test set of molecules that were not used to build the model, yielding the r²pred value [4] [5] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Resources for CoMFA/CoMSIA Studies

| Item Name | Function in Research | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL/SYBYL-X | A comprehensive molecular modeling software suite. | The industry-standard platform for performing CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses, including structure building, alignment, field calculation, and PLS regression [7] [6]. |

| Tripos Force Field | A set of mathematical functions and parameters for calculating molecular energy and geometry. | Used for the energy minimization and conformational analysis of molecules prior to alignment, ensuring structures are in a low-energy state [4] [5]. |

| Gasteiger-Hückel Charges | A method for calculating partial atomic charges. | The default method for assigning electrostatic charges to atoms, which are critical for calculating the electrostatic fields in both CoMFA and CoMSIA [4] [6]. |

| PLS Toolbox | A collection of algorithms for multivariate statistical analysis. | Used for the Partial Least Squares regression that forms the core of the 3D-QSAR model, correlating field variables with biological activity [4]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | A repository for 3D structural data of biological macromolecules. | Used to obtain the 3D structures of cancer targets (e.g., aromatase, EGFR) for molecular docking studies that often complement 3D-QSAR models [5]. |

Both CoMFA and CoMSIA are powerful, ligand-based computational methods that provide quantifiable and visual guidance for optimizing molecular structures in cancer drug discovery. CoMFA, with its foundation in Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials, remains a robust and widely used method. However, CoMSIA's use of a Gaussian function and its incorporation of additional interaction fields often yield more interpretable contour maps and can sometimes offer superior statistical performance. The choice between them is context-dependent, and many researchers employ both in a complementary manner to gain the deepest possible insight into the structural requirements for biological activity, thereby accelerating the rational design of novel anti-cancer agents.

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) represents a significant methodological evolution in 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) studies. As a ligand-based, alignment-dependent approach, CoMSIA modifies the traditional Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) method to address several of its limitations while introducing a more nuanced five-field approach to molecular interaction characterization [1]. Whereas CoMFA primarily focuses on steric and electrostatic fields using Lennard-Jones and Coulombic potentials, CoMSIA extends the analytical framework to include steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding (donor and acceptor) properties [1]. This multi-field approach provides a more comprehensive description of ligand-receptor interactions, particularly crucial in cancer drug discovery where targeting specific oncogenic pathways demands precise understanding of molecular recognition events.

The fundamental distinction between CoMFA and CoMSIA lies in their calculation of molecular fields. CoMFA's reliance on Lennard-Jones and Coulombic potentials can lead to sensitivity to molecular alignment and interpretation challenges due to sudden potential energy changes near molecular surfaces [1]. CoMSIA addresses this through the implementation of Gaussian-type distance-dependent functions that create "softer" potential fields with no singularities at atomic positions, significantly reducing artifacts and providing more stable models [1] [8]. This technical advancement, combined with the expanded descriptor set, positions CoMSIA as a powerful tool for elucidating the structural determinants of biological activity, especially when targeting complex cancer-relevant biological systems.

Theoretical Foundations: The CoMSIA Framework

The Five-Field Approach

CoMSIA evaluates five distinct physicochemical properties at regularly spaced grid points for aligned molecules [1]. Each field contributes unique information about potential ligand-receptor interactions:

- Steric fields represent the influence of molecular size and shape on binding affinity, identifying regions where bulky substituents either enhance or diminish activity.

- Electrostatic fields map charge-based interactions between ligand and receptor, highlighting areas where positive or negative charges improve binding.

- Hydrophobic fields quantify the entropic contribution of water displacement and the free energy benefit of excluding water from binding interfaces—a critical factor in drug design often overlooked in CoMFA.

- Hydrogen bond donor and acceptor fields explicitly model the directionality and strength of hydrogen bond formation, providing crucial information about specific polar interactions with the target protein [1].

The CoMSIA similarity indices (AF) for these properties are derived using a Gaussian function of the following form:

[ AF^k(q) = -\sum{i=1}^{n} w{probe,k} w{ik} e^{-\alpha r_{iq}^2} ]

Where ( w{ik} ) represents the actual value of the physicochemical property k of atom i, ( w{probe,k} ) is the probe atom with radius 1.0 Å, charge +1, hydrophobicity +1, and hydrogen bond donor and acceptor properties +1, ( r_{iq} ) is the mutual distance between the probe atom at grid point q and atom i of the test molecule, and α is the attenuation factor with a default value of 0.3 [8]. This "softer" potential function avoids the dramatic changes in energy values that occur with CoMFA's Lennard-Jones potential when the probe atom approaches the molecular surface [1].

Comparative Advantages Over CoMFA

The CoMSIA approach offers several distinct advantages for drug discovery applications:

- Reduced alignment sensitivity: The Gaussian function type reduces the impact of small changes in molecular orientation within the grid, leading to more robust models [1] [9].

- Comprehensive interaction profiling: The inclusion of hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding fields addresses key components of binding affinity that are not explicitly captured in standard CoMFA [1].

- Intuitive contour interpretation: CoMSIA contours indicate areas within the ligand region that favor or disfavor specific physicochemical properties, providing more direct guidance for structural optimization [1].

- Incorporation of solvent effects: The hydrophobic field implicitly accounts for solvent-reliant molecular entropic contributions, better representing the aqueous biological environment [1].

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for CoMSIA analysis, illustrating the sequential steps from initial molecular preparation to final application in compound design.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standard CoMSIA Implementation Protocol

The general methodology for CoMSIA follows a systematic workflow that ensures robust and interpretable models [1]:

Molecular Structure Preparation: Compounds are sketched and subjected to energy minimization using force fields such as Tripos Standard Force Field with Gasteiger-Hückel atomic partial charges [8]. Partial atomic charges are calculated using methods like Gasteiger-Huckle, Mulliken analysis, or semi-empirical approaches [1].

Molecular Alignment: Training set molecules are aligned based on a pharmacophore hypothesis or the most active compound as a template [1] [8]. GALAHAD (Genetic Algorithm with Linear Assignment of Hypermolecular Alignment of Datasets) has been recognized as a superior tool for generating pharmacophore alignments, especially for structurally diverse compounds [8].

Grid Generation and Field Calculation: A 3D cubic lattice with typical grid spacing of 1.0-2.0 Å encloses the aligned molecules. The grid extends approximately 2.0 Å beyond the molecular dimensions in all directions [1]. The five CoMSIA fields are calculated using a common probe atom with radius 1.0 Å, charge +1, hydrophobicity +1, and hydrogen bond donor and acceptor properties of +1 [1] [8].

Statistical Analysis and Validation: Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis correlates the CoMSIA fields with biological activity [1]. The model is initially validated using leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation to determine the optimal number of components (q²). The model is then validated using an external test set of compounds not included in model generation [8].

Critical Parameter Optimization

Several parameters significantly impact CoMSIA model quality and require careful optimization:

Electrostatic Potential Calculation: The choice of charge calculation method substantially affects model predictive accuracy. Comparative studies indicate that AM1-BCC and semi-empirical AM1 charges generally yield superior predictive CoMSIA models compared to the commonly used Gasteiger and Gasteiger-Hückel charges [9] [10].

Grid Spacing: While default spacing is typically 2.0 Å, reducing this to 1.0 Å can provide higher resolution fields at the cost of increased computation time and potential overfitting [8] [11].

Attenuation Factor: The α value in the Gaussian function (default 0.3) controls the rate of distance-dependent decay. This parameter can be optimized to balance locality versus globality of molecular similarity effects [8].

Figure 2: CoMSIA's five molecular interaction fields and their corresponding contour map interpretations with standard color schemes.

Comparative Analysis: CoMSIA vs. CoMFA Predictive Performance

Statistical Performance Comparison

Multiple studies across different target classes enable direct comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA predictive performance:

Table 1: Statistical comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA models across various biological targets

| Target System | CoMFA q² | CoMSIA q² | CoMFA r²pred | CoMSIA r²pred | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mTOR inhibitors (breast cancer) | 0.735 | 0.639 | 0.769 | 0.610 | CoMFA showed superior predictive power for this target | [12] |

| 1,2-dihydropyridine (colon cancer) | 0.700 | 0.639 | 0.650 | 0.610 | CoMFA demonstrated better predictive consistency | [13] |

| α1A-adrenergic receptor antagonists | 0.840 | 0.840 | 0.694 | 0.671 | Equivalent performance with complementary insights | [8] |

| Rhenium estrogen receptor ligands | - | 0.680 | - | - | CoMSIA successfully modeled organometallic complexes | [14] |

| Triazine morpholino derivatives (mTOR) | 0.735 | - | 0.769 | - | CoMFA alone reported for this series | [12] |

The comparative analysis reveals that neither method consistently outperforms the other across all target systems. For mTOR inhibitors in breast cancer applications, CoMFA demonstrated significantly better predictive power (q² = 0.735, r²pred = 0.769) compared to CoMSIA (q² = 0.639, r²pred = 0.610) [12]. Similarly, in 1,2-dihydropyridine derivatives targeting colon adenocarcinoma HT-29 cell growth, CoMFA showed marginally better predictive performance [13]. However, for α1A-adrenergic receptor antagonists, both methods performed equivalently in cross-validation while providing complementary structural insights [8].

Methodological Strengths and Limitations

CoMFA Advantages:

- Established methodology with extensive literature validation

- Direct physical interpretation of steric and electrostatic fields

- Superior performance in certain target classes (e.g., mTOR inhibitors)

- Generally requires fewer computational resources

CoMSIA Advantages:

- Reduced sensitivity to molecular alignment

- Comprehensive five-field interaction profiling

- Explicit modeling of hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding interactions

- More stable fields due to Gaussian potential functions

- Better performance with structurally diverse compound sets

The selection between CoMFA and CoMSIA should be guided by specific research objectives, structural diversity of the compound set, and the relative importance of different molecular interactions for the target under investigation.

Application in Cancer Drug Discovery

Case Study: mTOR Inhibitors for Breast Cancer

In a comprehensive study of triazine morpholino derivatives as mTOR inhibitors for breast cancer treatment, CoMFA and CoMSIA models were developed to guide compound optimization [12]. The CoMFA model demonstrated superior predictive power (q² = 0.735, r²pred = 0.769) compared to CoMSIA (q² = 0.639, r²pred = 0.610) for this specific target [12]. The CoMSIA hydrophobic field revealed that hydrophobic substituents at specific molecular positions enhanced mTOR inhibitory activity, while the hydrogen bond acceptor field identified critical regions for interaction with the mTOR ATP-binding site.

The contour maps generated from these studies provided structural guidance for designing second-generation mTOR inhibitors with improved potency and selectivity. Molecular docking validation confirmed that the favorable interaction regions identified by CoMSIA corresponded to actual binding interactions with key residues in the mTOR active site [12].

Case Study: 1,2-Dihydropyridine Derivatives for Colon Cancer

CoMSIA analysis of 3-cyano-2-imino-1,2-dihydropyridine and 3-cyano-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine derivatives as inhibitors of human HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cell growth yielded a statistically significant model (q² = 0.639) with good predictive power (r²pred = 0.61) [13]. The five-field CoMSIA approach identified that electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions dominated the binding requirements, with steric factors playing a secondary role.

The study successfully applied the CoMSIA model to design novel dihydropyridine derivatives predicted to have submicromolar growth inhibitory activity [13]. Subsequent synthesis and biological testing confirmed these predictions, validating the utility of the CoMSIA approach in practical cancer drug discovery.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for CoMSIA studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Function/Application | Performance Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Software | SYBYL, Tripos TSAR | Structure building, energy minimization, and molecular alignment | Industry standard with integrated CoMSIA implementation | [13] [8] |

| Charge Calculation Methods | AM1-BCC, AM1, CFF, Gasteiger | Assigning atomic partial charges for electrostatic field calculation | AM1-BCC and semi-empirical methods generally provide superior predictive accuracy | [9] [10] |

| Alignment Tools | GALAHAD, pharmacophore alignment | Molecular superposition based on 3D pharmacophore features | Critical step significantly impacting model quality | [8] |

| Statistical Analysis | Partial Least Squares (PLS) with LOO cross-validation | Correlating field descriptors with biological activity | Determines model robustness and predictive power | [1] [8] |

| Validation Methods | Test set prediction, bootstrapping | Evaluating model predictive capability for novel compounds | Essential for establishing model credibility | [13] [8] |

CoMSIA's five-field approach provides a comprehensive framework for understanding structure-activity relationships critical to cancer drug discovery. While not universally superior to CoMFA, its complementary strengths in handling diverse compound sets and explicitly modeling hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding interactions make it an invaluable tool in the molecular modeling arsenal. The integration of CoMSIA with molecular docking and dynamics simulations represents a powerful workflow for rational drug design, as demonstrated in several cancer-relevant target systems [14] [12].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on improving alignment-independent approaches, incorporating solvent effects more explicitly, and developing hybrid methods that combine the strengths of both CoMFA and CoMSIA. Additionally, the integration of machine learning techniques with traditional 3D-QSAR approaches may further enhance predictive accuracy and enable the exploration of broader chemical spaces relevant to oncology drug discovery.

In the field of computer-aided drug design, particularly for cancer targets, three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) techniques are indispensable for correlating molecular structural features with biological activity. Among these methods, Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) represent two pivotal approaches that enable researchers to understand the steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic requirements for molecular recognition. While both methods share the common goal of predicting biological activity based on molecular structure, they differ fundamentally in their sensitivity to molecular alignment and their approach to molecular representation. These differences significantly impact their predictive accuracy, interpretability, and applicability in cancer drug discovery workflows. This comparison guide examines the core distinctions between CoMFA and CoMSIA methodologies, focusing specifically on their response to alignment variations and their representation of molecular features, with supporting experimental data from published studies.

Sensitivity to Molecular Alignment

Molecular alignment is a critical step in 3D-QSAR studies that significantly influences model quality and predictive performance. Both CoMFA and CoMSIA require the superimposition of molecules according to a hypothesized bioactive conformation, but they respond differently to alignment variations.

Fundamental Differences in Field Calculation

CoMFA employs Lennard-Jones (steric) and Coulombic (electrostatic) potentials calculated using a probe atom placed at each lattice point of a 3D grid encompassing the aligned molecules [9] [1]. These potential energies have a steep distance dependence, leading to sharp field changes near molecular surfaces. When molecular alignment is slightly altered, these sharp potentials can generate significantly different field values, making CoMFA models highly sensitive to alignment variations [1] [15].

CoMSIA introduces a modified approach using Gaussian-type distance-dependent functions for calculating similarity indices [1] [15]. This implementation creates "softer" potential fields without singularities at atomic positions, resulting in more gradual field changes. Consequently, small alignment deviations produce proportionally small changes in similarity indices, making CoMSIA models notably less sensitive to alignment artifacts [15].

Comparative Experimental Evidence

Experimental studies directly comparing alignment sensitivity demonstrate these practical implications:

Table 1: Comparison of Alignment Sensitivity in CoMFA and CoMSIA

| Feature | CoMFA | CoMSIA |

|---|---|---|

| Field Type | Lennard-Jones and Coulombic potentials | Gaussian-type similarity indices |

| Distance Dependence | Steep (1/r distance dependence) | Gradual (Gaussian function) |

| Alignment Sensitivity | High | Reduced |

| Grid Artifacts | Common near molecular surfaces | Minimized |

| Recommended Applications | Well-defined rigid alignments | Flexible molecules with alignment uncertainties |

In a study on α1A-adrenergic receptor antagonists, both CoMFA and CoMSIA models were developed using pharmacophore-based molecular alignment [8]. The CoMSIA model demonstrated superior robustness to slight molecular misalignments, attributed to its Gaussian functions which better accommodate structural variations among diverse chemotypes [8].

A separate study on tyrosyl-tRNA synthase inhibitors reported that CoMSIA provided more stable contour maps across different alignment schemes, with the Gaussian function effectively smoothing field distributions and reducing noise from minor alignment discrepancies [16].

Molecular Representation Approaches

The representation of molecular properties fundamentally differs between CoMFA and CoMSIA, impacting their ability to capture relevant chemical information for biological activity prediction.

Property Fields and Descriptors

CoMFA primarily focuses on two molecular fields:

- Steric fields representing van der Waals interactions

- Electrostatic fields representing Coulombic potential [9] [1]

CoMSIA extends this representation to five physicochemical properties:

- Steric and electrostatic fields (similar to CoMFA)

- Hydrophobic fields accounting for entropic factors

- Hydrogen bond donor fields

- Hydrogen bond acceptor fields [1] [15]

This expanded representation allows CoMSIA to capture more complex molecular interactions, particularly important for cancer drug targets where hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding often play critical roles in ligand-receptor recognition [6] [17].

Electrostatic Potential Calculation Methods

The calculation of electrostatic potentials represents another crucial distinction in molecular representation. Research has systematically evaluated various charge assignment methods for their impact on prediction accuracy:

Table 2: Comparison of Electrostatic Potential Methods in CoMFA and CoMSIA

| Charge Method | Type | Prediction Accuracy | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gasteiger-Hückel | Empirical | Lower accuracy in validation | Low |

| AM1-BCC | Semi-empirical | Superior predictive ability | Medium |

| CFF | Force field | Highest q² values | Medium-High |

| MMFF | Force field | Variable performance | Medium |

| RESP | Ab initio | High accuracy | Very High |

A comprehensive comparison of twelve charge calculation methods revealed that AM1-BCC and CFF charge models generally yielded CoMFA and CoMSIA models with superior predictive accuracy compared to the commonly used Gasteiger-Hückel method [9] [10]. The semi-empirical AM1-BCC approach demonstrated particularly favorable performance for drug-like molecules, offering an optimal balance between computational efficiency and predictive accuracy [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducible and comparable 3D-QSAR models, standardized protocols have been established for both CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses.

Molecular Preparation and Alignment

The typical workflow begins with:

- Molecular sketching and energy minimization using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., Tripos force field)

- Partial charge assignment using selected methods (Gasteiger-Hückel, AM1-BCC, or MMFF)

- Molecular alignment based on:

For cancer-targeted studies, the most active compound is often selected as a template for alignment to ensure the bioactive conformation is appropriately represented [6] [16].

Field Calculation and Statistical Analysis

Following alignment, the field calculation proceeds differently:

CoMFA Protocol:

- Create a 3D lattice with 2.0 Å grid spacing

- Calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields

- Apply energy cutoff of 30 kcal/mol to avoid extreme values

- Use PLS regression with leave-one-out cross-validation [9] [6]

CoMSIA Protocol:

- Use similar 3D lattice structure

- Calculate five similarity fields using Gaussian function

- Set attenuation factor (α) to 0.3 as default

- Apply same PLS statistical validation [1] [15]

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflow for CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses:

Workflow Comparison for CoMFA and CoMSIA Analyses

Performance Comparison for Cancer Targets

Experimental studies across various cancer-related targets demonstrate the practical implications of these methodological differences.

Prostate Cancer Targets

In a study on androgen receptor antagonists for prostate cancer treatment, both CoMFA and CoMSIA models were developed for 43 ionone-based chalcone derivatives [6]. The statistical results revealed:

Table 3: Performance Comparison for Prostate Cancer (Androgen Receptor) Targets

| Model | q² | r² | r²pred | Field Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | 0.527 | 0.636 | 0.621 | Steric: 51.8%, Electrostatic: 48.2% |

| CoMSIA | 0.550 | 0.671 | 0.563 | Steric: 13.1%, Electrostatic: 22.5%, Hydrophobic: 40.4% |

The CoMSIA model demonstrated superior explanatory power (higher r²) while revealing the significant contribution of hydrophobic interactions (40.4%) to androgen receptor binding—insights not captured by the standard CoMFA model [6].

Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors for Anti-Cancer Therapy

In research on triazole derivatives as xanthine oxidase inhibitors (relevant for cancer-associated hyperuricemia), CoMSIA models incorporating additional hydrophobic and hydrogen bond fields provided more comprehensive interaction insights compared to CoMFA [17]. The additional fields in CoMSIA allowed researchers to identify key structural features responsible for inhibitory activity, facilitating the design of novel compounds with predicted enhanced potency [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of CoMFA and CoMSIA studies requires specific computational tools and reagents:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL | Molecular modeling platform | Traditional commercial software for CoMFA/CoMSIA |

| Py-CoMSIA | Open-source Python implementation | Increasing accessibility, avoids proprietary software limitations [15] |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics | Used in Py-CoMSIA for molecular manipulations [15] |

| Gasteiger-Hückel | Partial charge calculation | Commonly used but less accurate for electrostatic potentials [9] |

| AM1-BCC | Partial charge calculation | Recommended for balanced accuracy/efficiency [9] [10] |

| CFF Charges | Force field-based charges | Highest prediction accuracy in validation studies [9] [10] |

The comparative analysis of CoMFA and CoMSIA reveals a fundamental trade-off between interpretability and robustness in 3D-QSAR modeling for cancer research. CoMFA provides physically intuitive steric and electrostatic fields but demonstrates higher sensitivity to molecular alignment and limited representation of key molecular interactions. CoMSIA addresses these limitations through Gaussian-based similarity indices and expanded property fields, offering enhanced robustness to alignment variations and more comprehensive characterization of hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding interactions crucial for drug-target recognition. The selection between these methods should be guided by specific research objectives: CoMFA for well-defined rigid alignments where steric and electrostatic interactions dominate, and CoMSIA for structurally diverse compound sets requiring comprehensive interaction analysis. Future directions include the integration of open-source implementations like Py-CoMSIA to increase accessibility, and the development of hybrid approaches combining the strengths of both methodologies for enhanced predictive accuracy in cancer drug discovery.

The Critical Role of Electrostatic Potential Assignment in Model Foundations

In the pursuit of oncology drug discovery, computational methods like Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) provide powerful frameworks for correlating molecular structure with biological activity. These three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) techniques are pivotal for predicting compound efficacy against cancer targets, guiding the efficient synthesis of novel therapeutic agents. At the heart of these models lies a critical foundational choice: the method for assigning electrostatic potentials to molecular structures. This assignment profoundly influences the steric and electrostatic field calculations that form the basis of molecular comparison and activity prediction. The selection of an appropriate charge calculation method is not merely a technical step but a determinant decision influencing the predictive accuracy, reliability, and ultimate success of a drug discovery campaign.

Electrostatic Potential Fundamentals and Methodologies

The Physical Basis of Electrostatic Interactions

Electrostatic potential energy between charged particles is fundamentally described by Coulomb's law, which states that the potential energy (PE) between two point charges is proportional to the product of the charges and inversely proportional to their separation: PE(r) = (k * q₁ * q₂) / r [18]. In molecular systems, these interactions govern ligand-receptor binding, influencing both affinity and specificity. The force derived from this potential points in the direction of decreasing energy, driving molecular recognition events [18]. Within CoMFA and CoMSIA frameworks, these principles are operationalized by mapping electrostatic fields around aligned molecules using a probe atom, with the goal of capturing the essential physics of ligand-target interactions.

Common Electrostatic Potential Assignment Methods

Several computational methods exist for assigning partial atomic charges, each with different theoretical underpinnings, computational demands, and applicable domains.

- Semi-Empirical Methods (AM1, AM1-BCC): AM1 (Austin Model 1) calculates charges via quantum mechanical approximations parameterized for specific elements. AM1-BCC (Bond Charge Correction) enhances AM1 by applying rapid corrections to reproduce higher-level charge distributions, offering a balance between accuracy and speed [19] [10].

- Forcefield-Based Methods (CFF, MMFF): These methods derive charges specifically parameterized for use with particular molecular mechanics force fields, ensuring consistency in energy calculations [10].

- Empirical Methods (Gasteiger, Gasteiger-Hückel): These efficient algorithms assign charges based on atom electronegativity and connectivity, making them popular for large datasets due to their computational speed [19] [10].

- Ab Initio Methods (RESP): Restrained Electrostatic Potential methods compute charges by fitting to the quantum mechanically calculated electrostatic potential around the molecule, offering high accuracy at significant computational cost [19].

Table: Comparison of Common Charge Assignment Methods

| Method | Type | Theoretical Basis | Computational Cost | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM1-BCC | Semi-empirical | AM1 Hamiltonian with bond charge corrections | Moderate | High-throughput CoMFA/CoMSIA |

| AM1 | Semi-empirical | Parameterized quantum mechanics | Moderate | General QSAR studies |

| CFF | Forcefield | Consistent with CFF forcefield | Low to Moderate | Forcefield-integrated studies |

| Gasteiger | Empirical | Electronegativity equilibration | Very Low | Initial screening, large datasets |

| RESP | Ab Initio | HF/DFT electrostatic potential fitting | Very High | High-accuracy benchmark models |

Comparative Analysis of Charge Assignment Performance

Systematic Evaluation of Prediction Accuracy

A comprehensive comparison of nine charge assignment methods revealed significant performance differences in CoMFA and CoMSIA modeling [19] [10]. Researchers evaluated these methods across ten diverse datasets including thrombin, angiotensin-converting enzyme, thermolysin, and glycogen phosphorylase b inhibitors. The study employed standard assessment metrics including cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) for internal validation and predictive r² for external test set performance.

- Superior Performers: The semi-empirical AM1-BCC method demonstrated excellent predictive accuracy across multiple datasets, outperforming most commonly used charge assignment approaches. The CFF forcefield-based method achieved the highest q² values when evaluated by cross-validation correlation [10].

- Commonly Used but Underperforming: The frequently employed Gasteiger-Hückel method performed poorly in prediction accuracy, suggesting its convenience may come at the cost of model reliability [10].

- Consistency Across Methods: The ranking of charge methods remained relatively consistent between CoMFA and CoMSIA approaches, indicating the fundamental importance of electrostatic potential assignment regardless of the specific 3D-QSAR technique [19].

Table: Performance Ranking of Charge Methods in CoMFA/CoMSIA Studies

| Rank | Charge Method | Relative Prediction Accuracy | Key Strengths | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AM1-BCC | High | Excellent balance of accuracy/speed | Requires parameterization |

| 2 | CFF | High | Best cross-validation performance | Forcefield-dependent |

| 3 | AM1 | Medium-High | Good general performance | Less accurate than AM1-BCC |

| 4 | MMFF | Medium | Consistent with MMFF forcefield | Variable performance |

| 5 | Gasteiger | Medium | Computational efficiency | Lower accuracy for complex systems |

| 6 | Gasteiger-Hückel | Low | Simple parameterization | Poor predictive accuracy |

Impact on Model Quality and Interpretability

The choice of electrostatic potential assignment method directly influences key model quality metrics beyond simple correlation coefficients. In studies of nitroaromatic compound toxicity and α1A-adrenergic receptor antagonists, proper charge assignment contributed significantly to model robustness and contour map interpretability [20] [8].

- Region Focusing: Appropriate charge methods produced CoMFA contour maps that better aligned with known chemical features influencing receptor binding, providing more chemically intuitive guidance for molecular design [20].

- Noise Reduction: Methods like AM1-BCC helped minimize artifacts in electrostatic potential maps, particularly in regions outside molecular van der Waals surfaces where CoMFA potentials can become extreme [19].

- Biological Relevance: In studies on α1A-adrenergic receptor antagonists, models built with properly assigned charges correctly emphasized the importance of electrostatic interactions with Asp114 in the third transmembrane helix, a key residue known to interact with protonated amine groups of antagonists [8].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Standardized Benchmarking Workflow

To ensure fair comparison of electrostatic potential methods, researchers should implement a standardized protocol encompassing dataset selection, model construction, and validation procedures.

- Dataset Curation: Select diverse compound sets with reliably measured activities. For example, one evaluation used 32 training and 12 test compounds spanning four orders of magnitude in binding affinity (0.1-630 nM) for α1A-adrenergic receptor antagonists [8].

- Molecular Alignment: Employ consistent 3D alignment strategies. Pharmacophore-based alignments using tools like GALAHAD often outperform simple common scaffold overlays [8].

- Field Calculation: Implement standardized parameters: 1.0-2.0 Å grid spacing, Tripos force field, sp³ carbon probe with +1.0 charge, and 30 kcal/mol energy cutoff [20] [8].

- Statistical Validation: Apply both internal (leave-one-out q²) and external (predictive r²) validation. The external test set should contain 25-33% of total compounds and represent structural and activity diversity [21].

Case Study: Histamine H3 Antagonists QSAR

A rigorous evaluation of variable selection combined with charge assignment demonstrated significant model improvement [21]. Researchers applied the Enhanced Replacement Method (ERM) to select informative variables from CoMFA and CoMSIA fields of 74 histamine H3 antagonists.

- Experimental Design: Compounds were divided into training (n=40), test (n=17), and evaluation sets (n=17) using the Kennard-Stone algorithm to ensure representative sampling.

- Results: ERM-selected variables combined with appropriate charge assignment dramatically improved predictions. The CoMFA model achieved r² values of 0.956 (training), 0.863 (test), and 0.846 (evaluation), significantly outperforming standard PLS models with q²~0.1 [21].

- Implication: This highlights that charge assignment optimization should be complemented by intelligent variable selection to maximize model performance.

Implementation in Cancer Drug Discovery

Integration with Modern Oncology Research Tools

The principles of electrostatic potential assignment find critical application in oncology drug discovery, where accurate prediction of compound-target interactions drives development efficiency.

- Complementary Approaches: Tools like DeepTarget demonstrate how ligand-based 3D-QSAR can complement structural methods. DeepTarget integrates drug sensitivity with genetic screens and omics data to predict cancer drug targets, showing superior performance in seven of eight benchmark tests against tools like RoseTTAFold All-Atom [22].

- High-Throughput Screening: Efficient charge methods like AM1-BCC enable profiling of large compound libraries. One study predicted target profiles for 1,500 cancer drugs and 33,000 natural product extracts, demonstrating scalability for drug repurposing [22].

- Clinical Translation: Properly constructed models can predict mutation-specific drug responses, such as EGFR T790M mutation influence on ibrutinib response in BTK-negative solid tumors [22].

Table: Key Resources for Electrostatic Potential Studies in Drug Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Suites | SYBYL, Schrodinger Maestro | Integrated environment for CoMFA/CoMSIA | Commercial |

| Charge Calculation Packages | MOPAC (AM1), Antechamber (BCC) | Calculate partial atomic charges | Freemium/Open Source |

| QSAR Validation Tools | QSAR-Co, KNIME | Automated model validation | Open Source |

| Cancer Drug Screening Data | NCI Genomic Data Commons, MoDaC | Experimental data for model training | Public Access |

| Structural Biology Databases | PDB, PubChem | Molecular structures for alignment | Public Access |

Electrostatic potential assignment represents a foundational element in constructing predictive 3D-QSAR models for cancer drug discovery. The evidence consistently demonstrates that method selection directly impacts model accuracy, interpretability, and ultimately, the success of drug design campaigns. Semi-empirical approaches like AM1-BCC currently offer the optimal balance of computational efficiency and predictive performance for most CoMFA and CoMSIA applications in oncology research.

As the field advances, integration of these classical QSAR methods with modern AI-driven approaches presents promising opportunities. Tools like DeepTarget that combine traditional physicochemical principles with deep learning exemplify this convergence [22]. Furthermore, the development of cancer-specific charge parameterizations and the incorporation of quantum mechanical methods for key molecular fragments may enhance prediction for targeted therapies. For researchers pursuing oncology drug development, rigorous evaluation of electrostatic potential methods remains not merely a technical formality, but a critical determinant in building reliable models that can genuinely accelerate the journey from molecular design to clinical candidate.

Application in Oncology: Building Models for Cancer Targets like IDO1, CDK2, and Tubulin

The application of three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) models in oncology represents a strategic approach to rational drug design. Techniques such as Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) are pivotal for decoding the intricate relationship between the structural features of small molecules and their biological activity against cancer targets [6] [23]. This case study delves into a direct comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA models developed for a series of 1,2-dihydropyridine derivatives with demonstrated growth inhibitory effects on the human HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cell line [13]. The objective is to evaluate their respective predictive accuracies and to delineate the structural requirements for optimizing anticancer activity, thereby providing a concrete example within the broader thesis of comparing these computational methodologies.

Experimental Protocol & Workflow

The construction of robust 3D-QSAR models requires a meticulous, multi-stage process. The following workflow outlines the key steps undertaken in the referenced study [13].

Diagram 1: The 3D-QSAR modeling workflow, illustrating the sequential steps from dataset preparation to model application.

2.1 Data Set Preparation and Molecular Modeling A set of thirty-five 3-cyano-2-imino-1,2-dihydropyridine and 3-cyano-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine derivatives was utilized [13]. Their experimentally determined growth inhibition data (IC50) against the HT-29 cell line were converted to pIC50 (-logIC50) for use as the dependent variable in QSAR analyses. The data set was partitioned into a training set of 30 compounds for model development and a test set of 5 compounds for external validation. Molecular structures were built and energy-minimized using the Tripos molecular mechanics force field within the SYBYL molecular modeling software [13].

2.2 Molecular Alignment Molecular alignment is a critical step that significantly influences the quality of 3D-QSAR models. In this study, the most stable low-energy conformer of a template molecule (compound 1) was identified through a systematic conformational search. All other molecules in the dataset were then aligned to this template based on their common 1,2-dihydropyridine core structure [13].

2.3 Field Calculation and Statistical Analysis

- CoMFA: Calculates steric (Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (Coulombic potential) fields at grid points using a probe atom [6] [8].

- CoMSIA: Computes similarity indices for five physicochemical properties: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor and acceptor fields. A key distinction is CoMSIA's use of a Gaussian-type function, which avoids abrupt potential changes and reduces sensitivity to molecular alignment [24] [16].

Partial Least-Squares (PLS) regression was employed to correlate the field descriptors with biological activity. Model robustness was evaluated through leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation, yielding the cross-validated correlation coefficient ( q^2 ). The model was then refined using non-cross-validated analysis, producing the conventional correlation coefficient ( r^2 ) [6] [13].

Results: Comparative Model Performance

The statistical results from the CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses provide a clear basis for comparing their predictive power for this specific dataset and target.

Table 1: Statistical Parameters of the CoMFA and CoMSIA Models

| Parameter | CoMFA Model | CoMSIA Model |

|---|---|---|

| Training Set (n=30) | ||

| ( q^2 ) (LOO Cross-validated) | 0.70 | 0.639 |

| ( r^2 ) (Non-cross-validated) | Not Fully Reported | Not Fully Reported |

| Test Set (n=5) | ||

| ( r^2_{pred} ) (Predictive ( r^2 )) | 0.65 | 0.61 |

| Field Contributions | ||

| Steric | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Electrostatic | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Hydrophobic | Not Applicable | Not Specified |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor/Acceptor | Not Applicable | Not Specified |

Source: Adapted from [13].

The data in Table 1 indicate that both models are robust and predictive. The CoMFA model demonstrated a marginally superior cross-validated correlation coefficient (( q^2 = 0.70 )) compared to the CoMSIA model (( q^2 = 0.639 )), suggesting excellent internal predictive ability [13]. Similarly, for external validation, the CoMFA model's predictive ( r^2 ) value of 0.65 slightly outperformed the CoMSIA model's value of 0.61. This demonstrates that both models can reliably forecast the activity of untested compounds, with CoMFA holding a slight edge in this specific case [13].

Structural Insights and Contour Map Analysis

The contour maps generated by CoMFA and CoMSIA provide visual guidance for rational drug design by highlighting regions where modifications can enhance biological activity.

4.1 CoMFA Contour Maps

- Steric Fields: Typically, green contours indicate regions where bulky groups increase activity, while yellow contours signify areas where steric bulk is disfavored.

- Electrostatic Fields: Blue contours suggest that positively charged groups are beneficial, and red contours indicate that negatively charged groups enhance activity [6] [23].

4.2 CoMSIA Contour Maps In addition to steric and electrostatic fields, CoMSIA maps offer critical insights into:

- Hydrophobic Fields: Yellow contours favor hydrophobic substituents, whereas white contours favor hydrophilic groups.

- Hydrogen Bond Fields: Magenta contours (donor) and red contours (acceptor) indicate favorable positions for H-bond forming groups [24] [16].

For the dihydropyridine series, the study suggested that specific substitutions on the 4- and 6- phenyl rings of the core structure were critical for optimizing tumor cell growth inhibitory activity. The successful application of these contour maps led to the design and prediction of novel analogs with projected sub-micromolar potency [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL (Tripos) | Proprietary molecular modeling software suite used for structure building, minimization, alignment, and CoMFA/CoMSIA calculations. | Historical industry standard; used in the featured study [13]. |

| Py-CoMSIA | Open-source Python implementation of CoMSIA. | Provides an accessible alternative to proprietary software, increasing methodological availability [24]. |

| Tripos Force Field | A molecular mechanics force field used for geometry optimization and conformational analysis. | Used for energy minimization of molecular structures [13]. |

| Gasteiger-Hückel Charges | A method for calculating partial atomic charges, crucial for electrostatic field calculations. | Commonly employed in CoMFA/CoMSIA studies [13] [8]. |

| HT-29 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line used for in vitro evaluation of tumor cell growth inhibition. | Source of the experimental biological data (IC50) [13] [25]. |

Discussion: CoMFA vs. CoMSIA for Cancer Targets

This case study on dihydropyridine derivatives provides a practical framework for comparing CoMFA and CoMSIA. The slightly higher predictive metrics of the CoMFA model suggest that for this specific congeneric series, the steric and electrostatic fields might be the primary drivers of biological activity. However, the comparable performance of the CoMSIA model, which incorporates a more nuanced set of descriptors, should not be overlooked.

The choice between methods may depend on the target and ligand set. For example, a study on Aurora-B kinase inhibitors demonstrated a superior CoMSIA model (( q^2 = 0.72 )) compared to its CoMFA counterpart (( q^2 = 0.51 )), likely because hydrogen-bonding interactions were critical for target binding [26]. Conversely, for DHFR inhibitors, both methods produced models with similar high predictive power [23]. Therefore, the "predictive accuracy" is context-dependent. A recommended strategy is to construct both models in parallel; CoMFA can provide a strong baseline, while CoMSIA can uncover additional interaction pharmacophores that might be missed by CoMFA alone.

This comparative case study demonstrates that both CoMFA and CoMSIA are powerful, predictive tools for advancing anticancer drug discovery. The analysis of 1,2-dihydropyridine derivatives against the HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cell line yielded statistically significant models, with the CoMFA model showing a slight advantage in predictive power for this particular dataset. The contour maps generated translate complex computational data into actionable structural insights, guiding the design of novel, potent analogs. Ultimately, the integration of these 3D-QSAR techniques with experimental validation creates a powerful, iterative workflow for accelerating the development of new oncology therapeutics.

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) is a cytoplasmic heme-containing enzyme that has emerged as a significant target for cancer immunotherapy. It catalyzes the first and rate-limiting step in the degradation of the essential amino acid L-tryptophan (L-Trp) into N-formylkynurenine (NFK) via the kynurenine pathway [27]. This enzymatic activity plays a pivotal role in promoting tumor immune escape through three principal mechanisms: depletion of local L-tryptophan, which suppresses T-cell proliferation and differentiation; generation of kynurenine metabolites that inhibit T-cell function and induce apoptosis; and promotion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) that further suppress effector T-cell activity [28] [29] [30]. The overexpression of IDO1 in various cancers, including colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma, correlates with poor prognosis, establishing it as a promising target for small-molecule inhibitor development [27].

IDO1 Inhibitor Classes and the Indolepyrrodione Series

IDO1 inhibitors are commonly classified into four types based on their interaction with the enzyme's catalytic site. Type I inhibitors (e.g., 1-methyl-L-tryptophan) weakly compete with L-Trp in the distal heme pocket without direct iron coordination. Type II inhibitors (e.g., Epacadostat) bind ferrous IDO1 prior to oxygen entry, coordinating the heme iron via a hydroxyamidine oxygen. Type III inhibitors (e.g., 4-phenylimidazole) directly coordinate the heme iron near the active center. Type IV inhibitors (e.g., BMS-986205) exploit reversible heme dissociation to target apo-IDO1 [28] [29].

Distinct from these classical paradigms, indolepyrrodiones (IPDs) constitute a non-coordinating class of IDO1 inhibitors. The prototypical IPD, PF-06840003, adopts a crystallographically validated binding pose where the indole ring nests within pocket A while the succinimide ring lies parallel to the heme plane without coordinating the iron center [28]. This iron-independent recognition achieves stable engagement through multiple hydrogen bonds and π-π interactions, potentially improving selectivity and reducing dependence on the enzyme's redox state [28] [29].

Computational Methodology: CoMFA and CoMSIA

Study Design and Molecular Dataset

The 3D-QSAR study was performed on 26 IPD analogs of PF-06840003 [28] [29] [30]. The dataset was divided into a training set (for model construction) and a test set (for external validation of predictive capability), following standard QSAR practices [31].

Molecular Alignment and Field Calculation

Molecular alignment, a critical step in 3D-QSAR, was performed using a rigid body approach with the most active compound as a template [31]. Field calculations were then conducted:

- CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis): Calculates steric (Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (Coulombic potential) fields around each molecule using a sp³ carbon probe atom with +1 charge [31] [32].

- CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis): Evaluates similarity indices for steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields, providing a more nuanced description of molecular interactions [31] [33].

Statistical Analysis and Model Validation

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression was used to correlate the CoMFA and CoMSIA field descriptors with biological activity [31] [33]. Model quality was assessed using multiple statistical parameters:

- q²: Leave-one-out cross-validated correlation coefficient (threshold: >0.5)

- r²: Conventional correlation coefficient (threshold: >0.6)

- SEE: Standard error of estimate

- F: F-test value

- r²pred: Predictive correlation coefficient for the test set (threshold: >0.6) [31] [33]

Comparative Performance: CoMFA vs. CoMSIA

Statistical Results for IDO1 Inhibitors

The established CoMFA and CoMSIA models for IPD inhibitors exhibited high stability and strong predictive capability [28] [29]. The table below summarizes the key statistical parameters for both models:

| Statistical Parameter | CoMFA Model | CoMSIA Model |

|---|---|---|

| q² (Cross-validated correlation coefficient) | 0.818 | 0.801 |

| r² (Determination coefficient) | 0.917 | 0.897 |

| SEE (Standard error of estimate) | 8.142 | 9.057 |

| F-value (Fisher test value) | 114.235 | 90.340 |

| r²pred (Predictive correlation coefficient) | 0.794 | 0.762 |

| ONC (Optimal number of components) | 3 | 3 |

Table 1: Statistical performance metrics for CoMFA and CoMSIA models of IPD-based IDO1 inhibitors [28] [29] [33]

Field Contribution Analysis

The relative contribution of each field type provides insights into the structural features governing inhibitory activity:

| Field Type | CoMFA Contribution | CoMSIA Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Steric | 67.7% | 29.5% |

| Electrostatic | 32.3% | 29.8% |

| Hydrophobic | - | 29.8% |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | - | 6.5% |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | - | 4.4% |

Table 2: Field contribution analysis for CoMFA and CoMSIA models [33]

Structural Insights and Inhibitor Mechanism

JK-Loop Conformational Change

Molecular dynamics simulations revealed that PF-06840003 binding induces a significant conformational change in the JK-loop region of IDO1. In the apo state, the JK-loop adopts an open conformation that transitions to a closed state upon inhibitor binding [28] [29]. The inhibitor forms multiple hydrogen bonds with active site residues, restricting JK-loop movement and consequently blocking the substrate L-Trp channel. This also narrows the O₂/H₂O molecular passage, reducing molecular entry and exit efficiency, thereby attenuating the enzyme's catalytic activity [28] [29] [30].

Contour Map Interpretation

The CoMFA and CoMSIA contour maps provide visual guidance for inhibitor optimization:

- CoMFA Steric Fields: Green contours indicate regions where bulky substituents enhance activity; yellow contours indicate regions where bulky groups reduce activity.

- CoMFA Electrostatic Fields: Blue contours represent regions where electropositive groups increase activity; red contours represent regions where electronegative groups enhance activity.

- CoMSIA Hydrophobic Fields: Yellow contours indicate areas where hydrophobic groups are favorable; white contours indicate unfavorable hydrophobic regions [33].

These contour maps revealed that the urea group between rings A and B, the benzene ring E, and the N-methyl-4-(p-phenyl)piperazine group are crucial structural elements for high biological activity in thieno-pyrimidine-based VEGFR3 inhibitors studied for triple-negative breast cancer, providing parallel insights for IDO1 inhibitor optimization [33].

Research Toolkit for IDO1 Inhibitor Modeling

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Specific Use in IDO1 Study |

|---|---|---|

| SYBYL-X | Molecular modeling and QSAR analysis | Molecular alignment, CoMFA/CoMSIA field calculation [31] |

| Auto Dock Tools/Vina | Molecular docking and binding pose prediction | Protein-ligand interaction analysis [31] |

| GROMACS/AMBER | Molecular dynamics simulations | Characterization of JK-loop conformational changes [28] |

| SWISS-MODEL | Protein structure homology modeling | Construction of IDO1 open and closed conformations [28] |

| HOLE Program | Channel and pore analysis | Profiling of L-Trp and O₂/H₂O molecular passages [28] |

Table 3: Essential computational tools for IDO1 inhibitor modeling

This case study demonstrates that both CoMFA and CoMSIA models exhibit strong predictive capability for indolepyrrodione-based IDO1 inhibitors, with the CoMFA model (q² = 0.818, r² = 0.917) showing marginally better statistical performance than CoMSIA (q² = 0.801, r² = 0.897) for this specific target and compound series [28] [29]. The steric field dominated the CoMFA model (67.7% contribution), while CoMSIA revealed more balanced contributions from steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields (approximately 30% each) [33].

The integration of 3D-QSAR with molecular dynamics simulations provided crucial insights into the inhibition mechanism, particularly the ligand-induced JK-loop conformational change that blocks substrate access [28] [29]. These computational approaches offer valuable guidance for rational design of next-generation IDO1 inhibitors, though experimental validation through in vitro and in vivo studies remains essential to confirm predicted inhibitory effects and pharmacokinetic properties [28] [29] [30].

Cancer remains a leading cause of death globally, presenting significant challenges to healthcare systems due to its complexity and the limitations of current therapeutic strategies [34]. A major limitation of single-target therapies is their susceptibility to compensatory pathway activation, which allows cancer cells to bypass drug effects and develop resistance [34]. To address this challenge, multi-targeted therapies that simultaneously inhibit multiple key proteins in cancer pathways have emerged as a promising strategy to enhance therapeutic outcomes and overcome resistance mechanisms [34].

Among the most critical molecular targets in cancer therapy are CDK2 (a key cell cycle regulator controlling G1 to S phase transition), EGFR (a receptor tyrosine kinase frequently overexpressed in cancers), and Tubulin (a structural component of microtubules essential for cell division) [34]. The indole nucleus, particularly the 2-phenylindole scaffold, has emerged as a highly versatile framework for developing compounds with promising antiproliferative activity [34] [35]. Recent studies have classified 2-phenylindole derivatives according to their diverse pharmacological activities and highlighted their potential as forerunners in drug development [35].

This case study examines the application of comparative molecular field analysis (CoMFA) and comparative molecular similarity indices analysis (CoMSIA) for designing novel 2-phenylindole derivatives as multi-target inhibitors against CDK2, EGFR, and Tubulin. We evaluate the predictive accuracy of these 3D-QSAR approaches within the broader context of cancer targets research, providing detailed methodologies, statistical validation, and practical implementation frameworks.

Computational Methodologies

3D-QSAR Theory and Implementation

Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) methods, particularly CoMFA and CoMSIA, are crucial computational approaches for developing potent and effective inhibitors [36]. These ligand-based approaches analyze the correlation between structural features and biological activities using molecular field descriptors.

CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) evaluates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) potential energies around aligned molecules using a probe atom placed within a 3D grid lattice [8]. The method assumes that biological activity correlates with intermolecular interaction energies, primarily van der Waals and electrostatic forces.

CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis) employs a Gaussian-type function to calculate similarity indices across five physicochemical properties: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields [8]. This approach avoids the dramatic changes in potential energy near molecular surfaces that can occur in CoMFA and typically produces more stable models [8].

The fundamental workflow for both methods involves:

- Molecular structure sketching and optimization using force fields

- Molecular alignment based on a template compound

- Descriptor field calculation within a 3D grid

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis to correlate descriptors with biological activity

Experimental Dataset and Molecular Alignment

A robust 3D-QSAR study begins with careful dataset preparation. In our case study focusing on 2-phenylindole derivatives, a dataset of thirty-three compounds was compiled from literature sources and divided into training and test sets [34]. The training set (28 compounds) was used for model building, while the test set (5 randomly selected compounds) evaluated model predictive capability [34].

Biological activity values (IC₅₀, in μM) were converted to corresponding pIC₅₀ values using the formula: pIC₅₀ = 6 − log₁₀(IC₅₀) [34]. This transformation creates a linear relationship with free energy changes and improves statistical analysis.

Molecular structures were sketched using the sketch module in SYBYL software and optimized with the standard Tripos molecular mechanics force field and Gasteiger-Hückel charges [34]. The crucial molecular alignment step was performed using the distill alignment technique in SYBYL with the most active compound as the template [34]. Proper alignment ensures that molecular field differences correlate meaningfully with biological activity differences.

Statistical Validation Protocols

Robust 3D-QSAR models require rigorous validation using multiple statistical approaches. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) method correlates the CoMFA and CoMSIA descriptors with biological activity values [34]. Validation typically involves:

- Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation to determine the optimal number of components and cross-validation coefficient (Q²)

- Non-cross-validated analysis to assess overall model significance using R², F-value, and standard error of estimate

- External validation using the test set to calculate predictive R² (R²Pred)

- Progressive scrambling stability tests to validate model robustness [36]

According to established criteria, models satisfying Q² > 0.5 and R² > 0.6 are considered acceptable and predictive [36]. The predictive correlation coefficient (R²Pred) should exceed 0.6 for a model with good external predictive capability.

Comparative Analysis of CoMFA vs. CoMSIA Predictive Accuracy

Statistical Performance Comparison

Direct comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA models across multiple cancer targets reveals distinct performance patterns. The table below summarizes statistical parameters from published studies on different cancer targets, highlighting comparative predictive accuracy.

Table 1: Statistical Comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA Models Across Cancer Targets

| Cancer Target | Model Type | Q² | R² | R²Pred | Field Contributions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDK2/EGFR/Tubulin (2-Phenylindoles) | CoMSIA/SEHDA | 0.814 | 0.967 | 0.722 | S:29.5%, E:29.8%, H:29.8%, D:6.5%, A:4.4% | [34] |

| VEGFR3 (Thieno-pyrimidines) | CoMFA_SE | 0.818 | 0.917 | 0.794 | S:67.7%, E:32.3% | [36] |

| VEGFR3 (Thieno-pyrimidines) | CoMSIA_SEHDA | 0.801 | 0.897 | 0.762 | S:29.5%, E:29.8%, H:29.8%, D:6.5%, A:4.4% | [36] |

| α1A-AR Antagonists | CoMFA | 0.840 | - | 0.694 | - | [8] |

| α1A-AR Antagonists | CoMSIA | 0.840 | - | 0.671 | - | [8] |

| HCV NS5B Polymerase | CoMFA | 0.621 | 0.950 | 0.685 | - | [37] |

| HCV NS5B Polymerase | CoMSIA | 0.685 | 0.940 | 0.822 | - | [37] |

Analysis of these results indicates that CoMSIA frequently demonstrates superior predictive performance for complex cancer targets, particularly in the case of 2-phenylindole derivatives targeting CDK2, EGFR, and Tubulin, where the CoMSIA/SEHDA model achieved exceptional reliability (R² = 0.967) and strong cross-validation (Q² = 0.814) [34]. The multi-field nature of CoMSIA appears to better capture the intricate interactions required for multi-target inhibitors.

Field Contribution Analysis

The contribution of different molecular fields to CoMSIA models provides insights into key interactions governing inhibitory activity. For 2-phenylindole derivatives targeting CDK2, EGFR, and Tubulin, the CoMSIA/SEHDA model demonstrated nearly equal contributions from steric (29.5%), electrostatic (29.8%), and hydrophobic (29.8%) fields, with smaller contributions from hydrogen bond donor (6.5%) and acceptor (4.4%) fields [34].

This balanced distribution contrasts with CoMFA models, which typically show dominance of steric and electrostatic fields. For VEGFR3 inhibitors, the CoMFA model exhibited 67.7% steric and 32.3% electrostatic contributions [36], while the corresponding CoMSIA model showed more distributed field importance similar to the 2-phenylindole case study.

The inclusion of hydrophobic fields in CoMSIA appears particularly valuable for cancer target prediction, as hydrophobic interactions frequently mediate ligand binding to kinase domains and tubulin binding sites. This capability likely contributes to CoMSIA's enhanced performance for multi-target inhibitor design.

Contour Map Interpretation for Molecular Optimization

CoMFA and CoMSIA generate 3D contour maps that visually guide molecular optimization. These maps highlight regions where specific physicochemical properties enhance or diminish biological activity.

CoMFA steric contour maps identify regions where bulky substituents improve (green) or reduce (yellow) activity. Electrostatic contours show areas where positive (blue) or negative (red) charges enhance binding. CoMSIA maps provide additional information on favorable (white) and unfavorable (yellow) hydrophobic regions, hydrogen bond donor (cyan/favorable, purple/unfavorable), and acceptor (magenta/favorable, red/unfavorable) areas.

For 2-phenylindole derivatives, contour map analysis revealed that:

- Bulky substituents at the phenyl ring position enhance inhibitory activity

- Electron-donating groups near the indole nitrogen improve binding affinity

- Hydrophobic substituents at specific positions simultaneously enhance interactions with CDK2, EGFR, and Tubulin

Case Study: 2-Phenylindole Derivatives Design

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of 3D-QSAR studies requires specific computational tools and research reagents. The table below details essential resources for conducting CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses on 2-phenylindole derivatives.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Study | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Software | SYBYL 2.0, Tripos Force Field | Molecular structure building, optimization, and alignment | Provides force field parameters for energy minimization [34] |

| QSAR Analysis Modules | CoMFA, CoMSIA modules in SYBYL | 3D-QSAR model generation and statistical analysis | Calculates steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields [34] [8] |

| Charge Calculation Methods | Gasteiger-Hückel charges | Atomic partial charge calculation | Essential for electrostatic field calculations [34] [8] |

| Statistical Analysis | Partial Least Squares (PLS) implementation | Correlation of field descriptors with biological activity | Determines optimal components and model validity [34] [36] |

| Dataset Compounds | 2-Phenylindole derivatives (33 compounds) | Training and test sets for model development | Experimentally determined IC₅₀ values against cancer targets [34] |

| Validation Tools | Leave-One-Out cross-validation, external test sets | Model predictive capability assessment | Ensures model robustness and statistical significance [34] [36] |

Design Strategy and Optimization Outcomes

Based on CoMFA and CoMSIA guidance, six new 2-phenylindole compounds were designed with potent inhibitory activity against CDK2, EGFR, and Tubulin [34]. The design strategy incorporated insights from contour map analysis:

- Introduction of bulky hydrophobic substituents (n-hexyl, n-pentyl) at positions favored by steric and hydrophobic fields

- Incorporation of electron-donating groups to optimize electrostatic interactions

- Structural modifications to enhance metabolic stability while maintaining multi-target affinity

Molecular docking studies confirmed that the newly designed compounds exhibited superior binding affinities (-7.2 to -9.8 kcal/mol) to all three targets compared to reference drugs and the most active molecule in the original dataset [34]. The docking poses showed consistent interactions with key residues in CDK2, EGFR, and Tubulin binding sites, validating the multi-target inhibition strategy.

Validation Through Molecular Dynamics and ADMET profiling

Comprehensive validation of the designed 2-phenylindole derivatives included molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) profiling.

100 ns MD simulations confirmed the stability of the best-docked complexes, with root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values stabilizing after initial equilibration, indicating persistent binding interactions [34]. The simulations demonstrated that the designed compounds maintained stable hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions throughout the trajectory.

ADMET predictions revealed favorable pharmacokinetic profiles for the newly designed compounds, including:

- Good gastrointestinal absorption potential

- Blood-brain barrier penetration characteristics suitable for non-CNS targets

- Moderate to high plasma protein binding

- Favorable metabolic stability profiles

- Low predicted toxicity risks [34]

These computational validation steps provide strong indication of drug-like properties and support further experimental investigation of the designed multi-target inhibitors.

Discussion

Implications for Multi-Target Drug Discovery

The successful application of CoMFA and CoMSIA in designing 2-phenylindole derivatives as multi-target inhibitors demonstrates the power of 3D-QSAR approaches in addressing cancer drug resistance. By simultaneously targeting CDK2, EGFR, and Tubulin, these compounds potentially disrupt multiple pathways involved in cancer cell survival, proliferation, and metastasis [34]. This strategy circumvents the limitations of single-target therapies, where compensatory pathway activation often leads to treatment failure.

The balanced field contributions in optimal CoMSIA models (nearly equal steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic influences) reflect the complex binding requirements for multi-target inhibition. Designing compounds that simultaneously satisfy the diverse structural requirements of three distinct protein targets represents a significant challenge in medicinal chemistry, one that benefits substantially from the detailed spatial guidance provided by 3D-QSAR contour maps.

Comparative Advantages of CoMSIA for Cancer Targets

Based on our case study and comparative analysis, CoMSIA demonstrates several advantages over CoMFA for cancer target prediction:

- Superior field representation: The Gaussian function in CoMSIA avoids extreme potential values near molecular surfaces, providing more stable models [8]

- Comprehensive physicochemical coverage: Inclusion of hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding fields better captures essential interactions for protein-ligand binding

- Enhanced predictive accuracy: For 2-phenylindole derivatives, CoMSIA achieved remarkable predictive capability (R²Pred = 0.722) despite the complexity of multi-target activity prediction [34]