Combating Overfitting in 3D-QSAR Models: Robust Strategies for Anticancer Drug Discovery

Overfitting presents a significant challenge in 3D-QSAR modeling, often leading to non-predictive models and failed optimizations in anticancer drug discovery.

Combating Overfitting in 3D-QSAR Models: Robust Strategies for Anticancer Drug Discovery

Abstract

Overfitting presents a significant challenge in 3D-QSAR modeling, often leading to non-predictive models and failed optimizations in anticancer drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive framework for diagnosing, resolving, and preventing overfitting to build robust and reliable 3D-QSAR models. We explore foundational concepts and the critical importance of model validation, detail advanced methodological approaches including machine learning integration and field-based techniques, and offer practical troubleshooting strategies for dataset curation and feature selection. Finally, we cover rigorous internal and external validation protocols and comparative analyses of modeling techniques. This guide is intended to empower medicinal chemists and computational scientists with the tools to create generalizable QSAR models that successfully translate to novel, potent anticancer compounds.

Understanding and Diagnosing Overfitting in 3D-QSAR Models

In the pursuit of new anticancer compounds, 3D-QSAR models are indispensable tools that correlate the three-dimensional molecular structures of compounds with their biological activity. However, a pervasive challenge in model development is overfitting, where a model learns the noise and specific details of its training data rather than the underlying structure-activity relationship. This results in a model that appears perfect statistically but fails to make accurate predictions for new, unseen compounds. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and foundational knowledge to help researchers diagnose, prevent, and solve overfitting in their 3D-QSAR workflows.

FAQs: Understanding and Diagnosing Overfitting

What is overfitting in the context of a 3D-QSAR model?

Overfitting occurs when a 3D-QSAR model is excessively complex, capturing not only the genuine structure-activity relationship but also the random fluctuations and noise present in the training dataset [1]. Imagine memorizing answers for a specific practice test instead of understanding the subject; you will fail a different test on the same topic. Similarly, an overfitted model will have excellent statistical fit for the training compounds (e.g., high R²) but poor predictive power for external test compounds [2] [1].

What are the key statistical indicators of a potential overfitting problem?

A significant gap between a model's performance on the training set and its performance on the test set is the primary red flag. The following table summarizes the key metrics to watch:

| Statistical Metric | Indicator of Potential Overfitting |

|---|---|

| High R² (Training) | A value very close to 1.0 (e.g., >0.9) can indicate the model is fitting the training data too closely [3]. |

| Low Q² (Cross-Validation) | A large gap between R² and the cross-validated R² (Q²). A rule of thumb is that Q² should be greater than 0.5 for a predictive model [4] [1]. |

| Low R² (Test Set) | The model performs poorly on the independent test set that was not used during model training, demonstrating a lack of generalizability [2] [5]. |

| Large RMSE Delta | A significant difference between the Root Mean Square Error of the training set and the test set indicates poor generalization [1]. |

How can the "Applicability Domain" of a model help prevent overfitting issues?

The Applicability Domain (AD) defines the chemical space within which the model's predictions are considered reliable [6]. A model is only an extrapolation tool, not a universal oracle. Using a model to predict compounds outside of its AD—those structurally very different from the training set—is a common user error that leads to inaccurate results, even if the model itself is robust. Techniques like the leverage method can be used to determine if a new compound falls within the model's AD [7].

What are the main causes of overfitting in a 3D-QSAR study?

The primary causes are related to data and model complexity:

- Too Many Descriptors: Using a large number of 3D molecular field descriptors (e.g., steric, electrostatic) relative to the number of compounds in the training set. This is known as the "curse of dimensionality" [5].

- Descriptor Redundancy: Using highly correlated or redundant descriptors that do not provide new information (multi-collinearity) [1].

- Insufficient Data: Building a model with a small dataset that does not adequately represent the chemical space of interest [2].

- Overly Complex Algorithms: Applying highly flexible, non-linear algorithms without proper validation and regularization can easily lead to fitting the noise in the data [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Solving Overfitting in Your Experiment

Step 1: Diagnose the Problem

Begin by rigorously validating your model.

- Action: Split your data into a training set (typically 70-80%) and a test set (20-30%) before model building. The test set must be kept completely blind and only used for the final model evaluation [2].

- Action: Perform internal validation like 5-fold cross-validation on your training set to calculate Q² [2] [1].

- Check: Compare R² (training), Q² (cross-validation), and R² (test). A large gap between any of these values confirms an overfitting problem.

Step 2: Implement Solutions to Improve Model Robustness

Once a problem is diagnosed, apply these corrective measures.

Solution: Apply Robust Feature Selection

- Methodology: Reduce the number of descriptors to only the most meaningful ones. Instead of manually removing low-variance or highly correlated descriptors, use supervised methods like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) [5] [1]. RFE iteratively removes the least important features based on model performance, retaining the most predictive ones.

- Protocol: Use software tools (e.g., via a Flare Python API script) to implement RFE, which ranks descriptors by their real contribution to predicting activity [1].

Solution: Use Machine Learning Algorithms Resistant to Overfitting

- Methodology: Switch from classical linear regression to algorithms designed to handle descriptor redundancy and non-linearity.

- Protocol: Gradient Boosting Machines (e.g., XGBoost, CatBoost) are tree-based models that inherently prioritize informative descriptor splits and down-weight redundant ones, making them robust to multi-collinearity [8] [1]. These models have been successfully used in QSAR studies to predict properties like inhibition efficiency and hERG channel liability [8] [1].

Solution: Apply Data Preprocessing Best Practices

- Methodology: Ensure your dataset is curated and prepared correctly from the start.

- Protocol:

- Standardize Structures: Remove salts, normalize tautomers, and handle stereochemistry [2].

- Calculate a Diverse Set of Descriptors: Use tools like PaDEL-Descriptor, RDKit, or Dragon to generate 3D field descriptors, topological indices, and electronic properties [5] [1].

- Scale Descriptors: Normalize descriptor values to have a zero mean and unit variance to ensure equal contribution during model training [2].

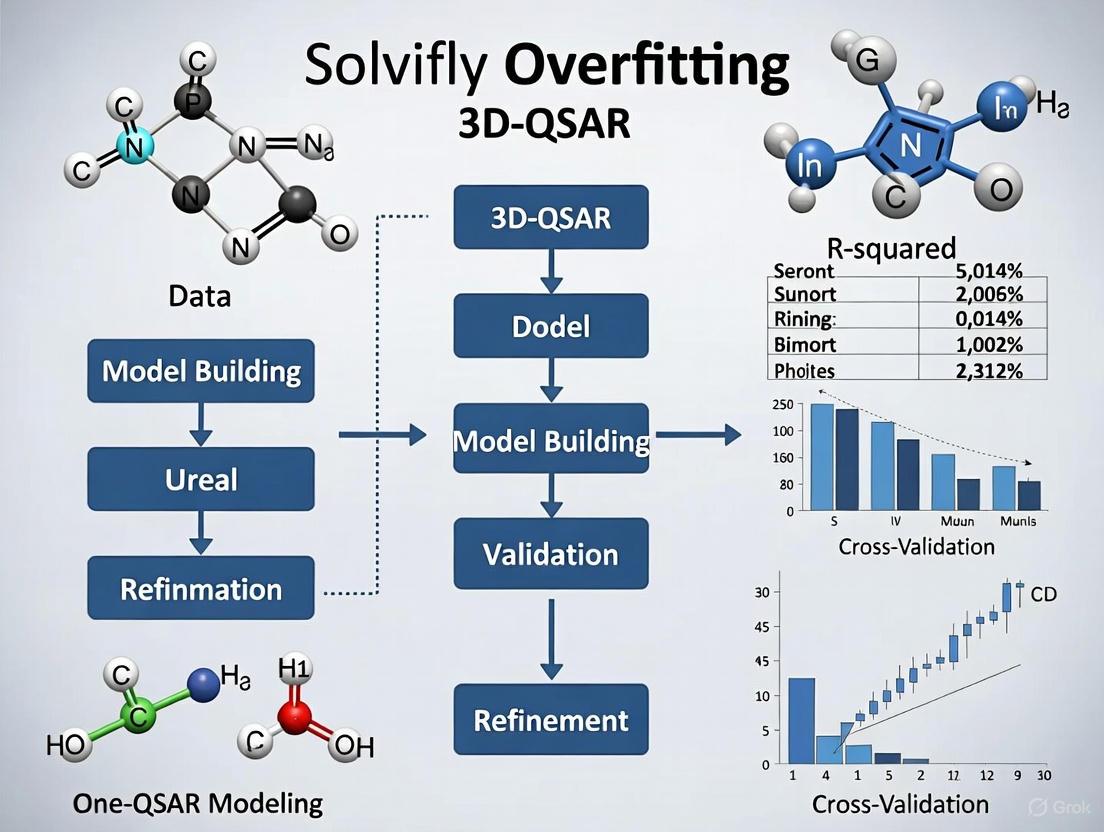

Diagram: Troubleshooting Overfitting in 3D-QSAR

This workflow outlines the diagnostic and solution process for addressing overfitting.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Robust 3D-QSAR

The following table lists key software and computational tools essential for developing validated and predictive 3D-QSAR models.

| Tool Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Application in Preventing Overfitting |

|---|---|---|

| Schrödinger Phase [4] | A comprehensive tool for 3D-QSAR model development, including pharmacophore hypothesis generation and model validation. | Provides robust PLS statistics and facilitates the creation of training/test sets. |

| Cresset Flare [1] | A platform for 3D and 2D QSAR modeling using field points or standard molecular descriptors. | Includes Gradient Boosting ML models and Python scripts for RFE to tackle descriptor intercorrelation. |

| RDKit [5] [1] | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used to calculate a wide array of 2D and 3D molecular descriptors for model building. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor [5] | Software for calculating molecular descriptors and fingerprints. | Helps generate a diverse set of descriptors for feature selection. |

| QSARINS [5] | Software specifically designed for robust QSAR model development with extensive validation tools. | Offers advanced validation techniques and data preprocessing options to ensure model reliability. |

| DeepAutoQSAR [6] | An automated machine learning solution for building QSAR models. | Provides uncertainty estimates and model confidence scores to define the Applicability Domain. |

Diagram: QSAR Model Validation Workflow

A proper data splitting and validation workflow is the first defense against overfitting.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most critical pitfalls that can compromise my 3D-QSAR model's reliability? The most critical pitfalls are data noise in the experimental biological activity data, using a high number of molecular descriptors relative to the number of compounds (leading to overfitting), and inadequate model validation that fails to test the model's generalizability to new compounds [5] [9] [10].

2. My model has excellent internal validation statistics but performs poorly on new compounds. What is the likely cause? This is a classic sign of overfitting, often due to a high descriptor-to-compound ratio. When the number of descriptors is too large, the model can memorize noise and specific characteristics of the training set instead of learning the underlying structure-activity relationship, harming its predictive power for external compounds [5] [11].

3. Can a QSAR model ever be more accurate than the experimental data it was trained on? Yes, under certain conditions. It is a common misconception that models cannot be more accurate than their training data. If experimental error is random and follows a Gaussian distribution, a model can learn the true underlying trend and make predictions that are closer to the "true" biological activity value than the error-laden experimental measurements in your dataset [9].

4. Why is it essential to define an "Applicability Domain" for my QSAR model? The Applicability Domain (AD) defines the chemical space within which the model's predictions are considered reliable. Predictions for compounds that are structurally very different from those in the training set involve a high degree of extrapolation and are less trustworthy. Defining the AD helps users understand the model's limitations and prevents misapplication [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Managing Data Noise and Experimental Error

Symptoms: Unusually high residuals for certain compounds, difficulty in achieving a good model fit even with complex algorithms, inconsistent performance across different validation sets.

Solutions:

- Curate Data Meticulously: Prioritize data from uniform, high-quality biological assays conducted in the same laboratory to minimize systematic error [12].

- Estimate Experimental Error: Be aware of the typical error ranges for your biological endpoint. For example, one analysis of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic (DMPK) data found that 87% of over 350,000 measurements had only a single replicate, highlighting the inherent uncertainty in many datasets [9].

- Apply Robust Algorithms: Some machine learning methods like Random Forest (RF) are inherently more robust to noisy data. In comparative studies, RF and Deep Neural Networks (DNN) sustained high predictive performance even as training set size decreased, unlike traditional methods like PLS and MLR which were more sensitive to noise and prone to overfitting [13].

Issue 2: Overcoming High Descriptor-to-Compound Ratios and Overfitting

Symptoms: A perfect or excellent fit on the training data (high R²) but poor performance on the test set (low R²pred), large discrepancies between internal and external validation metrics.

Solutions:

- Implement Rigorous Feature Selection: Do not use all generated descriptors. Apply feature selection techniques to identify the most relevant variables.

- Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) can be coupled with algorithms like Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) to effectively reduce descriptor count and mitigate overfitting [11].

- SelectFromModel is another technique that uses model-based feature importance to select the most critical descriptors [11].

- Use Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can transform a large number of correlated descriptors into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components, which can then be used for modeling [5] [14].

- Apply Regularization: Methods like LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) perform both variable selection and regularization to enhance model robustness [5].

Issue 3: Ensuring Adequate Model Validation

Symptoms: A model that cannot predict the activity of new, structurally distinct compounds, despite passing internal validation checks.

Solutions:

- Go Beyond Internal Validation: Internal validation (e.g., Leave-One-Out cross-validation, yielding q²) is necessary but not sufficient. A model must be rigorously validated using an external test set of compounds that were never used in model building [15].

- Adhere to Established Validation Criteria: Use a comprehensive set of statistical parameters to judge your model's predictive power. The table below outlines key benchmarks for a reliable 3D-QSAR model.

Table 1: Key Validation Parameters and Their Benchmarks for a Predictive 3D-QSAR Model

| Parameter | Type of Validation | Benchmark for a Good Model | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| q² (LOO) | Internal | > 0.5 [15] | Measures internal robustness and consistency of the model. |

| r² | Internal | > 0.9 [15] | Measures goodness-of-fit for the training set. |

| R²pred | External | > 0.5 [15] | The most critical measure of the model's predictive ability on new data. |

| MAE | External | ≤ 0.1 × training set range [15] | Measures the average magnitude of prediction errors. |

| Golbraikh & Tropsha Criteria | External | R² > 0.6, 0.85 < k < 1.15, [(R² – R₀²)/R²] < 0.1 [15] | A set of statistical tests to further confirm the model's external predictive reliability. |

- Define the Applicability Domain (AD): Quantify the chemical space your model represents. Techniques like Prediction Confidence and Domain Extrapolation can be used. The Decision Forest method, for example, calculates a confidence level for each prediction, allowing users to focus on high-confidence results [10].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Robust 3D-QSAR Model with Integrated Machine Learning

This protocol outlines a modern approach to 3D-QSAR that integrates machine learning to enhance predictive performance and combat overfitting [11].

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the integrated modeling workflow that combines traditional 3D-QSAR descriptor generation with modern machine learning techniques for robust model development.

Key Steps:

- Data Collection and Curation: Collect a dataset of compounds with uniform experimental activity data. For example, a study on antioxidant peptides used a curated FTC dataset of 197 tripeptides after removing duplicates and outliers [11].

- 3D Structure Generation and Alignment: Generate 3D molecular conformations. Interestingly, one study found that simple 2D->3D converted structures (from ChemSpider) could produce models superior to those from energy-minimized or template-aligned structures, and in a fraction of the time [12].

- Descriptor Calculation and Feature Selection: Calculate 3D descriptors (e.g., CoMSIA fields). This can generate thousands of descriptors. Apply feature selection methods like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) or SelectFromModel to identify the most predictive subset and reduce overfitting [11].

- Model Training with ML Algorithms: Move beyond traditional PLS. Train multiple machine learning algorithms (e.g., XGBoost, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression) on the selected features.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use techniques like GridSearchCV to systematically optimize the parameters of your chosen ML algorithm for the best performance [11].

- Comprehensive Validation: Rigorously validate the final model using both internal (cross-validation) and external (test set) validation, adhering to the benchmarks in Table 1.

Protocol 2: Assessing Prediction Confidence and Applicability Domain

This protocol is based on the Decision Forest (DF) methodology to quantify the reliability of each prediction your model makes [10].

Workflow Overview: The process of defining prediction confidence and applicability domain involves building a consensus model and calculating specific metrics for new compounds.

Key Steps:

- Build a Decision Forest Model: Develop multiple, heterogeneous Decision Tree models, each using a distinct set of molecular descriptors. The consensus of these trees forms the final Decision Forest model [10].

- Calculate Prediction Probability: For a new compound, each tree in the forest provides a probability of activity. The mean probability (P) across all trees is the final prediction.

- Quantify Prediction Confidence: Calculate the confidence level (C) for each prediction using the formula: C = 2 × |P - 0.5|. A confidence value of 1 indicates maximum confidence (P=1 or P=0), while a value of 0 indicates minimum confidence (P=0.5) [10].

- Define the Applicability Domain: Establish a confidence threshold (e.g., C > 0.4) to define the model's domain of applicability. Predictions for compounds that fall below this threshold should be treated with caution as they lie outside the model's reliable prediction space [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Software and Computational Tools for Robust 3D-QSAR Modeling

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| PaDEL, RDKit, DRAGON | Descriptor Calculation Software | Calculate 2D and 3D molecular descriptors from chemical structures [5]. |

| scikit-learn, KNIME | Machine Learning Platform | Provides a wide array of algorithms for feature selection, model building, and hyperparameter tuning [5]. |

| QSARINS, Build QSAR | Classical QSAR Software | Support classical model development with enhanced validation roadmaps and visualization tools [5]. |

| Sybyl (Tripos Force Field) | Molecular Modeling Suite | Traditionally used for CoMFA/CoMSIA studies for molecular alignment and field calculation [11]. |

| OPLS_2005 Force Field | Molecular Force Field | An alternative force field for molecular mechanics calculations and conformation generation [11]. |

| Select KBest | Feature Selection Method | A filter method for selecting the most relevant descriptors based on univariate statistical tests [8]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Interpretation Framework | Provides both local and global interpretability for ML models, identifying key descriptors driving predictions [8]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My CoMFA model shows a high R² but fails to predict the activity of the external test set. What is the cause? A: This is a classic sign of overfitting. The model has likely memorized the training set noise. To resolve this:

- Reduce the number of PLS components by using a lower cross-validated standard error.

- Increase the grid spacing (e.g., from 1.0 Å to 2.0 Å) to decrease the number of independent variables.

- Re-evaluate your molecular alignment to ensure it is biologically relevant.

- Apply a higher energy cutoff for the steric and electrostatic fields (e.g., 30 kcal/mol).

Q2: The PLS analysis for my CoMSIA model does not converge. What should I do? A: Non-convergence often stems from insufficient variation in the field descriptors.

- Verify that your dataset has a sufficient activity range (recommended > 3 log units).

- Check that you have not selected too many similar CoMSIA fields simultaneously. Start with Steric and Electrostatic only.

- Ensure all molecules are properly aligned and that no atom exists outside the defined grid.

Q3: How do I choose the optimal number of components for a Gaussian Field 3D-QSAR model? A: Use cross-validation rigorously.

- Perform a Leave-One-Out (LOO) or Leave-Group-Out (LGO) cross-validation.

- Plot the cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) against the number of components.

- The optimal number is the one that gives the highest q² value before it plateaus or decreases.

Q4: My contour maps are uninterpretable or show no clear regions. What steps can I take? A: This indicates a weak model or poor alignment.

- Re-inspect the statistical significance (q², r², standard error) of your model. If low, return to alignment and descriptor calculation.

- In CoMFA/CoMSIA, increase the contour level contribution (e.g., from 80% to 90%) to focus on the most significant regions.

- For Gaussian models, adjust the Gaussian kernel width (sigma) parameter; a value that is too broad can smear out important features.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Robust Molecular Alignment for Anticancer Compounds

- Identify a Common Core: Select a rigid, common substructure present in all molecules believed to be essential for binding to the biological target.

- Energy Minimization: Minimize the energy of each molecule using a force field (e.g., Tripos or MMFF94) with a distance-dependent dielectric and a gradient convergence criterion of 0.05 kcal/(mol·Å).

- Database Alignment: Use the "Database Align" function in software like SYBYL. Align all molecules to the template molecule based on the predefined common core atoms.

- Validation: Visually inspect the alignment from multiple angles to ensure consistency.

Protocol 2: Cross-Validation and External Validation to Prevent Overfitting

- Data Splitting: Randomly divide the dataset into a training set (typically 80%) and an external test set (20%). Ensure both sets cover the entire activity range.

- Model Building: Build the 3D-QSAR model (CoMFA, CoMSIA, or Gaussian) using only the training set.

- Internal Validation (q²): Perform Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation on the training set. The optimal number of components (N) is that which yields the highest q².

- External Validation (r²pred): Predict the activity of the external test set using the model built with N components. Calculate the predictive r² using the formula: r²pred = 1 - [Σ(Ypredicted - Yobserved)² / Σ(Yobserved - Ȳtraining)²], where Ȳ_training is the mean activity of the training set.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Key Statistical Parameters for Robust 3D-QSAR Models

| Model Type | Optimal PLS Components | q² (LOO) | r² (Non-cross-validated) | Standard Error of Estimate | r²_pred (External Test) | F-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | 4-6 | > 0.5 | > 0.8 | Low | > 0.6 | > 100 |

| CoMSIA | 4-6 | > 0.5 | > 0.8 | Low | > 0.6 | > 100 |

| Gaussian Field | 3-5 | > 0.5 | > 0.8 | Low | > 0.6 | > 100 |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR

| Item | Function in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|

| SYBYL-X Suite | Industry-standard software for molecular modeling, alignment, and performing CoMFA/CoMSIA analyses. |

| Open3DQSAR | Open-source tool for performing 3D-QSAR analyses, including Gaussian Field-based methods. |

| Tripos Force Field | Used for energy minimization of ligands to ensure stable, low-energy 3D conformations prior to alignment. |

| Gasteiger-Marsili Charges | A standard method for calculating partial atomic charges, crucial for the electrostatic field in CoMFA/CoMSIA. |

| PLS Toolbox (in MATLAB) | A statistical toolbox for performing Partial Least Squares regression and cross-validation. |

Mandatory Visualization

Title: 3D-QSAR Overfitting Prevention Workflow

Title: CoMSIA Descriptor Field Relationships

The Critical Role of Molecular Alignment and Conformational Sampling in Model Stability

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Model Instability and Overfitting in 3D-QSAR

Problem: Your 3D-QSAR model shows excellent performance on training data but poor predictive accuracy for new compounds, indicating potential overfitting.

Solution: Implement a rigorous conformational sampling and validation strategy.

- Step 1: Evaluate Conformational Complexity. Calculate the Kier Index of Molecular Flexibility for your dataset. Molecules with high indices (>5.0) are flexible and require more careful conformational analysis [12].

- Step 2: Compare Conformation-Generation Methods. Systematically generate conformations using at least two different methods. A recommended comparison includes [12]:

- Global Minimum Conformation: Locate the global minimum of the potential energy surface (PES).

- Template-Based Alignment: Align molecules to one or more biologically relevant templates.

- Rapid 2D-to-3D Conversion: Use simple molecular mechanics for direct 2D->3D conversion without extensive optimization.

- Step 3: Build and Validate Separate Models. Construct individual 3D-QSAR models for each conformational set. Validate each model using an external test set and strong statistical measures (e.g., R²Test, Q²) [12] [3].

- Step 4: Implement Consensus Modeling. If individual models show similar performance, average the predictions from models built on different molecular conformations to achieve a more robust consensus prediction [12].

Verification: A stable and reliable model will have a high consensus R²Test value with minimal statistical variance between predictions from different conformational sets.

Guide 2: Resolving Poor Predictive Performance Despite Good Initial Statistics

Problem: The 3D-QSAR model has good initial statistics (e.g., high R² for training), but the resulting contour maps do not offer chemically intuitive insights for drug design.

Solution: Integrate 2D molecular descriptors to clarify 3D field contributions.

- Step 1: Perform 2D-QSAR Analysis. Calculate a comprehensive set of 2D molecular descriptors (e.g., quantum chemical, topological, geometrical) for your compounds [3].

- Step 2: Identify Key 2D Descriptors. Use feature selection methods (e.g., the Heuristic Method) to identify which 2D descriptors most significantly impact biological activity [3].

- Step 3: Correlate with 3D Fields. Analyze if the most important 2D descriptors align with the regions highlighted in your 3D-QSAR contour maps. For instance, a key descriptor like "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN) should be interpreted in the context of hydrophobic or electrostatic fields from the 3D model [3].

- Step 4: Generate Design Hypotheses. Use the combined 2D and 3D information to propose structural modifications. This hybrid approach can flag critical substructural features that contribute to binding affinity and provide a more solid foundation for designing new compounds [12] [3].

Verification: The design hypotheses generated from the integrated 2D/3D analysis should be logically consistent and lead to the successful prediction or design of compounds with high activity, confirmed by molecular docking [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most computationally efficient method for generating conformations for a large dataset without significantly sacrificing model accuracy?

For large and diverse datasets, evidence suggests that a simple 2D-to-3D (2D->3D) conversion can be highly effective. In a study on androgen receptor binders, models using non-energy-optimized, non-aligned 2D->3D structures directly sourced from databases like ChemSpider produced a superior R²Test of 0.61. Crucially, this was achieved in only 3-7% of the time required by energy-intensive minimization or alignment procedures [12]. This makes it an excellent starting point for large-scale screening, especially for data sets where highly active compounds are fairly inflexible [12].

Q2: How can I determine if my 3D-QSAR model is overfitted?

An overfitted model typically displays a significant discrepancy between its performance on the training data and its performance on unseen test data. Key indicators include [3]:

- A high coefficient of determination for the training set (R²) but a low one for the test set (R²Test).

- A low cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²).

- Overly complex models with many descriptors but a limited number of training compounds.

- Contour maps that are noisy and lack a coherent, chemically interpretable structure.

Q3: What are the best practices for splitting my data into training and test sets to avoid overfitting?

To ensure a robust model, the data split must be statistically sound. A random partitioning strategy, such as allocating a certain ratio of compounds to the training and test sets, is commonly used [3]. It is critical that the test set is used only for model validation and not for any parameter adjustment or model building decisions. The training set should be large enough to capture the underlying structure-activity relationship and should encompass the structural diversity present in the entire dataset.

Q4: When is it necessary to use advanced conformational sampling like template alignment instead of simple 2D->3D conversion?

Advanced conformational sampling becomes critical when the biological activity is known to be highly dependent on a specific bioactive conformation that is not the global energy minimum. This is often the case for flexible molecules that interact with a protein active site in a well-defined pose. If a rapid 2D->3D approach yields models with poor predictive power, switching to a template-based alignment using a known active compound as a reference can impose a biologically relevant conformation, which may improve the model [12].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Different Conformational Strategies in 3D-QSAR

This table summarizes quantitative findings from a study on 146 androgen receptor binders, comparing the predictive performance and computational efficiency of different methods for defining molecular conformations [12].

| Conformational Strategy | Average R²Test | Key Statistical Insight | Computational Time (Relative) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Minimum (PES) | 0.56 - 0.61 | Good performance, but dependent on accurate energy minimization. | 100% (Baseline) |

| Alignment-to-Template | 0.56 - 0.61 | Performance varies with template selection; can be subjective. | 100% |

| 2D->3D Conversion | 0.61 | Achieved the best predictive accuracy in the study. | 3-7% |

| Consensus Model | 0.65 | Highest accuracy by aggregating predictions from multiple conformational models. | >100% |

Table 2: Comparison of 2D vs. 3D-QSAR Model Performance for Anticancer Dihydropteridone Derivatives

This table compares the performance of different QSAR modeling approaches from a study on 34 dihydropteridone derivatives with anti-glioblastoma activity [3].

| Model Type | Modeling Technique | R² (Training) | R² (Test) / Q² | Key Descriptor / Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-Linear | Heuristic Method (HM) | 0.6682 | 0.5669 (R² cv) | Model based on 6 selected molecular descriptors. |

| 2D-Nonlinear | Gene Expression Programming (GEP) | 0.79 | 0.76 (Validation Set) | Captures nonlinear relationships better than HM. |

| 3D-QSAR | CoMSIA | 0.928 | 0.628 (Q²) | Superior fit; combines steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Developing a Stable 3D-QSAR Model

Objective: To establish a standardized procedure for building a predictive and stable 3D-QSAR model while mitigating the risk of overfitting.

Materials: A dataset of compounds with known biological activity (e.g., IC50, RBA), molecular modeling software (e.g., HyperChem, CODESSA), and a QSAR modeling platform.

Procedure:

- Data Curation and Preparation: Collect and curate biological activity data. Improve data normality by converting activities to logarithms (e.g., log(RBA)) [12].

- Conformational Sampling & 3D Structure Generation:

- Sketch 2D structures using a tool like ChemDraw [3].

- Generate 3D conformations using multiple methods: a. Rapid 2D->3D: Use molecular mechanics (MM+) for initial optimization [3]. b. Energy-Minimized: Perform further optimization with semi-empirical methods (AM1/PM3) until the root mean square gradient is below 0.01 [3]. c. Template-Aligned: Align molecules to a high-affinity template molecule using molecular field constraints [12].

- Descriptor Calculation & Model Building:

- For 3D-QSAR (e.g., CoMSIA): Calculate steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic field energies on a 3D grid [3].

- For 2D-QSAR: Calculate a wide range of molecular descriptors (quantum chemical, topological, etc.) using software like CODESSA. Apply feature selection (e.g., Heuristic Method) to reduce dimensionality [3].

- Model Validation:

- Consensus and Application:

- Compare models from different conformations. If performance is comparable, create a consensus model by averaging predictions [12].

- Use the final model and its contour maps to predict the activity of new compounds and suggest structural optimizations.

Workflow Diagram: 3D-QSAR Model Development

Protocol 2: Protocol for Integrating 2D Descriptors with 3D-QSAR

Objective: To enhance the interpretability and stability of a 3D-QSAR model by integrating key 2D molecular descriptors.

Materials: A set of energy-minimized molecular structures, descriptor calculation software (e.g., CODESSA), and a QSAR modeling tool.

Procedure:

- Structure Optimization: Ensure all molecular structures are fully optimized using a consistent protocol (e.g., MM+ followed by AM1/PM3) [3].

- 2D Descriptor Calculation: Use the optimized structures to calculate a comprehensive set of 2D molecular descriptors covering quantum chemical, structural, topological, and electrostatic properties [3].

- Linear Model Construction: Apply the Heuristic Method (HM) to the training set data to construct a linear 2D-QSAR model. This process will automatically select the most relevant descriptors [3].

- Descriptor Identification: Note the top descriptors selected by the HM, such as "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN) [3].

- Nonlinear Model Development (Optional): For a potentially better fit, develop a 2D-nonlinear model using an algorithm like Gene Expression Programming (GEP) [3].

- Correlation with 3D Fields: Interpret the most important 2D descriptors in the context of the 3D-QSAR contour maps. For example, a key electronic descriptor should be reflected in the electrostatic field contours.

- Hypothesis Generation: Combine the insights from both the 2D descriptors and the 3D fields to generate robust, chemically intuitive hypotheses for molecular design.

Logic Diagram: 2D & 3D-QSAR Integration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Robust 3D-QSAR Modeling

| Tool / Resource Name | Function in Research | Specific Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| ChemDraw | Chemical structure drawing and representation. | Used to sketch 2D structures of compounds before 3D conversion and optimization [3]. |

| HyperChem | Molecular modeling and visualization. | Performs geometry optimization using molecular mechanics (MM+) and semi-empirical methods (AM1/PM3) to generate stable 3D conformations [3]. |

| CODESSA | Calculation of molecular descriptors. | Computes a wide range of 2D descriptors (quantum chemical, topological, etc.) for heuristic model development and identification of key activity-influencing features [3]. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | A comprehensive software tool for (Q)SAR assessment. | Provides workflows for profiling chemicals, defining categories, and filling data gaps. Its structured assessment framework (QAF) helps in evaluating model reliability and regulatory acceptance [16]. |

| Kier Flexibility Index | A dimensionless quantitative indicator of molecular flexibility. | Helps assess the conformational complexity of a dataset. Identifying highly flexible compounds (high index) flags molecules that may require more sophisticated conformational sampling [12]. |

In the development of robust 3D-QSAR models for anticancer compounds, the early detection of overfitting is paramount. Overfitting occurs when a model learns not only the underlying relationship in the training data but also the noise, leading to poor predictive performance on new, unseen compounds. Three key metrics—R², Q², and RMSE—serve as essential diagnostic tools to guard against this. By monitoring these metrics during model construction and validation, researchers can distinguish between a model that has genuinely learned the structure-activity relationship and one that has merely memorized the training data.

This guide provides troubleshooting advice and detailed protocols to help you correctly interpret these metrics within the specific context of 3D-QSAR modeling.

Metric Definitions and Theoretical Foundations

R² (R-squared)

Also known as the coefficient of determination, R² quantifies the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable (e.g., biological activity) that is predictable from the independent variables (e.g., molecular descriptors) in your model [17] [18].

- Formula: R² = 1 - (SS₍res₎ / SS₍tot₎)

- SS₍res₎ (Sum of Squared Residuals): The sum of squared differences between the actual and predicted values.

- SS₍tot₎ (Total Sum of Squares): The sum of squared differences between the actual values and their mean [17].

- Interpretation: Its value ranges from -∞ to 1. An R² of 1 indicates a perfect fit to the training data, while an R² of 0 means the model performs no better than predicting the mean activity. Critically, R² can be negative if the model is arbitrarily worse than simply using the mean [18].

Q² (Q-squared)

Also known as R² predictive, Q² is the coefficient of determination obtained from a cross-validation procedure, most commonly leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation [19]. It is a pivotal metric for estimating model generalizability.

- Core Concept: The dataset is repeatedly split into a construction set (to build the model) and a validation set (to test it). The Q² is calculated based on the predictions for these left-out samples [19].

- Interpretation: It estimates the model's ability to predict the activity of new, untested compounds. A high Q² suggests a model with strong predictive power, which is the ultimate goal in drug discovery.

RMSE (Root Mean Square Error)

RMSE measures the average magnitude of the prediction error, providing a clear idea of how far your predictions are from the actual values, on average [17] [20].

- Formula: RMSE = √( Σ( yᵢ - ŷᵢ )² / n )

- Key Feature: It is expressed in the same units as the dependent variable (e.g., log(IC₅₀)), making it highly interpretable [17] [20]. Because errors are squared before averaging, RMSE gives a relatively high weight to large errors, making it sensitive to outliers [17].

The table below provides a consolidated summary of these metrics for quick reference.

| Metric | What It Measures | Interpretation | Ideal Value/Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² | Goodness-of-fit to the training data [17]. | Proportion of variance in the training set explained by the model [17]. | Closer to 1 is better, but a very high value can signal overfitting. |

| Q² | Predictive performance via cross-validation [19]. | Estimated proportion of variance the model can predict in new data [19]. | > 0.5 is generally acceptable; a large gap from R² indicates overfitting. |

| RMSE | Average prediction error magnitude [17] [20]. | Average distance between predicted and actual values, in activity units [17]. | Closer to 0 is better. Compare training and validation RMSE. |

Troubleshooting Guides: Diagnosing Overfitting

Guide 1: The R² vs. Q² Discrepancy

Problem: You observe a high R² value for your training set but a significantly lower Q² value from cross-validation.

Diagnosis: This is a classic signature of overfitting. The model has become too complex, fitting the noise in your training data, which fails to generalize to the left-out validation samples [19].

Solutions:

- Simplify the Model: Reduce the number of molecular descriptors used in the model. Employ feature selection techniques like Genetic Algorithms or feature importance from Random Forest to identify and retain the most relevant descriptors [21] [2].

- Increase Data Size: Augment your training set with more diverse anticancer compounds. A larger, more representative dataset helps the model learn the true signal rather than spurious correlations [10].

- Use Double Cross-Validation: Implement double (nested) cross-validation for a more reliable and unbiased estimation of the prediction error, especially when performing model selection (like choosing descriptors) [19].

Guide 2: The RMSE Divergence

Problem: The RMSE calculated on the training data is much lower than the RMSE calculated on a separate external test set or from cross-validation.

Diagnosis: The model's average error is deceptively low for the data it was trained on but unacceptably high for new data, confirming a lack of generalizability [17] [20].

Solutions:

- Check for Data Leakage: Ensure that no information from the test or validation set was used during the model training process.

- Review Data Preprocessing: Confirm that all preprocessing steps (e.g., scaling, normalization) were fit on the training data and then applied to the validation/test data. Fitting on the entire dataset can introduce bias and over-optimistic performance [2].

- Tune Hyperparameters: If using machine learning methods like Support Vector Machines or Neural Networks, use the validation set to systematically tune hyperparameters to prevent overfitting [2].

Guide 3: Excessively High or Low R²

Problem: Your model's R² value is suspiciously high (e.g., >0.95) or even negative.

Diagnosis:

- R² > 0.95: May indicate overfitting, especially if the Q² is low. Alternatively, it could mean the model is correct, but the former must be ruled out [18].

- R² < 0: The model's predictions are worse than simply predicting the mean activity of the training set. This points to a fundamental issue with the model or the data [18].

Solutions:

- For High R²: Follow the solutions in Guide 1.

- For Negative R²:

- Inspect Model Assumptions: Ensure the modeling algorithm is appropriate for your data. For example, trying to fit a linear model to a highly non-linear structure-activity relationship can yield poor results [18] [2].

- Verify Data Integrity: Check for errors in the activity data (e.g., IC₅₀ values) or descriptor calculation. Outliers can also severely impact model performance [2].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical process for diagnosing and addressing overfitting using these key metrics.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My R² is acceptably high (0.85), and my Q² is also reasonable (0.65). Is my model safe from overfitting? A: While these values suggest a decent model, you are not entirely "safe." Continuously monitor the model's performance on new, external compounds as they are synthesized. Furthermore, analyze the Applicability Domain of your model to understand for which types of new compounds the predictions are reliable [10].

Q2: Which is a better metric to compare different models: RMSE or R²? A: They provide different but complementary information and should be interpreted together [22]. RMSE tells you about the average error in your activity units, which is directly actionable. R² tells you about the proportion of variance explained. Since both are derived from the sum of squared errors, a model that outperforms on one will generally outperform on the other [22]. However, for final model selection, prioritize Q² and validation-set RMSE as they are better indicators of predictive performance.

Q3: What is the "Double Cross-Validation" I keep seeing, and why is it important? A: Standard cross-validation (which gives you Q²) can be biased if the same data is used for both model selection (e.g., choosing descriptors) and error estimation. Double cross-validation uses an outer loop for error estimation and an inner loop for model selection. This provides a more reliable and unbiased estimate of how your model will perform on truly unseen data and is highly recommended for rigorous QSAR modeling [19].

Q4: My RMSE is 0.5 log units. What does this mean for my drug discovery project? A: An RMSE of 0.5 means that, on average, your model's predicted activity (e.g., pIC₅₀) is half a log unit away from the true value. For context, this is a significant error, as a 0.5 log unit difference translates to approximately a 3-fold error in IC₅₀ concentration. You should use this value to assess if the model is sufficiently accurate for your project's stage—it may be adequate for early-stage virtual screening but unacceptable for lead optimization [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key computational "reagents" and tools essential for conducting a rigorous 3D-QSAR analysis and calculating the diagnostic metrics discussed in this guide.

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Software/Package |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerical representations of molecular structure and properties. The independent variables in the QSAR model [21] [2]. | DRAGON, PaDEL-Descriptor, RDKit [2] |

| Feature Selection Algorithm | Identifies the most relevant molecular descriptors to reduce model complexity and prevent overfitting [21] [2]. | Genetic Algorithms, LASSO Regression, Random Forest Feature Importance [2] |

| Regression Algorithm | The core engine that builds the mathematical relationship between descriptors and activity [2]. | Partial Least Squares (PLS), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Support Vector Machines (SVM) [3] [23] [2] |

| Validation Software Script | Code or software functionality to perform LOO cross-validation and double cross-validation. | Scikit-learn (Python), in-house scripts, SYBYL [23] [19] |

| Applicability Domain Tool | Defines the chemical space where the model's predictions are reliable, crucial for interpreting predictions on new compounds [10]. | Various standalone scripts, integrated tools in software like KNIME |

Advanced Methodologies to Build Generalizable 3D-QSAR Models

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our 3D-QSAR model performs well on training data but poorly on new anticancer compounds. What is the most likely cause and how can we address it? A1: This is a classic sign of overfitting. Your model has likely learned noise and specific patterns from the training data that do not generalize. To address this:

- Implement Regularization: Use L1 (Lasso) or L2 (Ridge) regularization, which is built into algorithms like XGBoost, to penalize model complexity and prevent overfitting [24].

- Leverage Robust Algorithms: Employ CatBoost, which uses an ordered boosting technique specifically designed to reduce overfitting by avoiding target leakage and prediction shift [25] [24].

- Validate Rigorously: Always use stratified k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) to ensure your model's performance is consistent across different subsets of your data [25].

Q2: For our research on anticancer compounds, which is better: CatBoost or XGBoost, and why? A2: The choice depends on your dataset's characteristics and research goals. The table below summarizes their strengths in the context of 3D-QSAR:

Table 1: Comparison of CatBoost and XGBoost for 3D-QSAR Modeling

| Feature | CatBoost | XGBoost |

|---|---|---|

| Categorical Data Handling | Excellent; automatic handling without manual preprocessing [24]. | Requires manual preprocessing (e.g., label encoding, one-hot). |

| Overfitting Prevention | High; uses ordered boosting and oblivious trees [25]. | High; uses regularization and tree pruning [24]. |

| Key Advantage for QSAR | Ideal for datasets with mixed molecular descriptors and categorical features. | Excellent for numerical molecular descriptor data; highly optimized for speed [24]. |

| Model Interpretability | High; supports SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) for biological insight [25]. | High; provides built-in feature importance scores. |

Q3: How can we interpret our machine learning model's predictions to gain biological insights for drug design? A3: Use Explainable AI (XAI) techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations). For instance, in anticancer drug synergy prediction, SHAP analysis can identify which molecular descriptors or gene expression profiles (e.g., PTK2, CCND1) contribute most to the model's predictions, thereby validating the model's biological relevance and generating hypotheses for compound optimization [25].

Q4: What is a common data-related pitfall when building these models, and how can we avoid it? A4: A common pitfall is data leakage during the preprocessing stage, particularly when encoding categorical variables or performing feature scaling. To avoid this:

- Preprocess Within Cross-Validation Folds: Always perform steps like imputation and scaling after splitting data into training and validation folds within the cross-validation loop. CatBoost mitigates this for categorical features by using a more robust encoding scheme as part of its algorithm [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Generalization of 3D-QSAR Model

Symptoms:

- High accuracy on training data, but low accuracy on test data or external validation sets.

- Large discrepancy between training and validation error metrics.

Diagnosis and Resolution Steps:

- Verify Data Splitting: Confirm your data was split into training, validation, and test sets correctly. The test set should never be used for any aspect of model training or parameter tuning.

- Simplify the Model:

- Increase Regularization: Systematically increase the L1/L2 regularization parameters in XGBoost (

reg_alpha,reg_lambda) or thel2_leaf_regparameter in CatBoost. - Reduce Model Complexity: Decrease the

max_depthof trees and increase themin_data_in_leafparameters.

- Increase Regularization: Systematically increase the L1/L2 regularization parameters in XGBoost (

- Expand and Augment Data:

- If possible, increase the size of your dataset of anticancer compounds.

- Apply data augmentation techniques suitable for molecular data, as demonstrated in cardiovascular disease research where data augmentation enhanced model performance [26].

- Utilize Ensemble Robustness: Consider using the CatBoost algorithm, which is inherently designed to reduce overfitting through its ordered boosting technique, making it a strong candidate for building more generalizable 3D-QSAR models [25].

Issue 2: Suboptimal Performance with Mixed Data Types (Numerical and Categorical Descriptors)

Symptoms:

- Model performance is unsatisfactory despite tuning.

- Significant effort is spent on manually encoding categorical variables.

Diagnosis and Resolution Steps:

- Algorithm Selection: Switch to CatBoost, which is specifically designed to handle datasets with numerous categorical features natively and efficiently without requiring extensive preprocessing [24].

- Benchmark Against XGBoost: For comparison, manually preprocess your categorical features for XGBoost using one-hot encoding or label encoding. However, note that this can lead to high dimensionality or ordinal assumptions that may not exist.

- Hyperparameter Tuning:

- For CatBoost, key parameters to tune include

learning_rate,iterations,depth, andl2_leaf_reg. - Use methods like Bayesian optimization or grid search within a cross-validation framework to find the optimal parameters.

- For CatBoost, key parameters to tune include

Issue 3: Lack of Interpretability in Model Predictions

Symptoms:

- The model is a "black box," making it difficult to understand which molecular features drive activity predictions.

- Difficulty in deriving meaningful chemical insights for the next round of compound synthesis.

Diagnosis and Resolution Steps:

- Integrate SHAP Analysis: Implement SHAP analysis post-model training. This provides both global and local interpretability.

- Identify Key Descriptors: Use SHAP summary plots to identify the molecular descriptors that have the largest impact on your model's predictions for anticancer activity, similar to how it was used to find important genes in drug synergy prediction [25].

- Validate Chemically: Cross-reference the top SHAP-identified descriptors with known chemical and biological knowledge. This step validates the model and can reveal novel structure-activity relationships.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Building a Robust 3D-QSAR Prediction Model Using CatBoost/XGBoost

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for integrating gradient boosting machines into a 3D-QSAR pipeline to enhance predictivity and combat overfitting.

1. Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

- Compound Optimization: Generate and optimize the 3D structures of your anticancer compounds using software like HyperChem. Use molecular mechanics (e.g., MM+) followed by semi-empirical methods (e.g., AM1, PM3) for geometry optimization [3].

- Descriptor Calculation: Calculate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors (quantum chemical, topological, geometrical, electrostatic) using programs like CODESSA [3].

- Data Curation: Clean the data by removing descriptors with zero variance and handling missing values appropriately. The dataset is then split into training and test sets (e.g., 80/20).

2. Model Training with Cross-Validation

- Algorithm Implementation: Implement CatBoost and XGBoost models. For CatBoost, categorical feature indices can be specified to leverage its native handling.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use a k-fold cross-validated (e.g., 5-fold) grid search to tune key hyperparameters.

- XGBoost:

max_depth,learning_rate,n_estimators,reg_alpha,reg_lambda. - CatBoost:

iterations,learning_rate,depth,l2_leaf_reg.

- XGBoost:

- Validation: The model with the best cross-validation performance (e.g., highest R² or lowest MSE on the validation folds) is selected.

3. Model Evaluation and Interpretation

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set. Report key metrics like R², Mean Squared Error (MSE), and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE).

- SHAP Analysis: Apply the SHAP library to the trained model to calculate Shapley values for each prediction. Generate summary plots and dependence plots to interpret the model globally and for individual compounds.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics from ML-Enhanced QSAR Studies

| Study / Model | Dataset | Key Metric | Reported Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost for Drug Synergy [25] | NCI-ALMANAC (Cancer cell lines) | ROC AUC | 0.9217 |

| Pearson Correlation | 0.5335 | ||

| XGBoost for Solubility Prediction [27] | 68 Drugs in scCO₂ | R² | 0.9984 |

| RMSE | 0.0605 | ||

| Fine-Tuned CatBoost for CVD Diagnosis [26] | Hospital Records | Accuracy | 99.02% |

| F1-Score | 99% |

Diagram: Workflow for Robust ML-Enhanced 3D-QSAR Modeling

Protocol 2: Implementing SHAP for Model Interpretation

1. Installation and Setup

- Install the

shapPython package via pip.

2. Calculating and Visualizing SHAP Values

- Create Explainer: Instantiate a

shap.TreeExplainerfor your trained CatBoost or XGBoost model. - Calculate Values: Calculate SHAP values for the training or test set using

explainer.shap_values(X). - Generate Plots:

- Summary Plot:

shap.summary_plot(shap_values, X)shows the global feature importance and impact. - Dependence Plot:

shap.dependence_plot("feature_name", shap_values, X)investigates the relationship between a specific descriptor and the model's output.

- Summary Plot:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for ML-Enhanced 3D-QSAR

| Item / Software | Function / Application | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| HyperChem | Molecular modeling and 3D structure optimization of compounds [3]. | Provides a reliable platform for generating accurate initial 3D geometries. |

| CODESSA | Calculates a wide range of 2D and 3D molecular descriptors [3]. | Comprehensive descriptor calculation for feature space generation. |

| CatBoost Library | Gradient boosting algorithm for datasets with categorical features [25] [24]. | Reduces preprocessing time and mitigates overfitting via ordered boosting. |

| XGBoost Library | Optimized gradient boosting algorithm for structured data [27] [24]. | High speed and performance, with built-in regularization. |

| SHAP Library | Explains the output of any machine learning model [25]. | Bridges the gap between model performance and biochemical interpretability. |

| NCI-ALMANAC/DrugComb | Public databases containing drug combination synergy data [25]. | Provides large-scale experimental data for training and validating predictive models. |

Leveraging Field-Based Descriptors and Pharmacophore Mapping for Structural Insight

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of overfitting in 3D-QSAR models for anticancer research?

Overfitting occurs when a model is too complex and learns the noise in the training data instead of the underlying structure-activity relationship, leading to poor predictions for new compounds. The main causes are detailed in the table below.

| Cause of Overfitting | Description | Impact on Model |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Training Compounds [28] | Using too few molecules relative to the number of 3D field descriptors calculated. | The model cannot reliably establish a generalizable relationship. |

| Poor Feature Selection [2] | Failing to identify and use the most relevant steric and electrostatic descriptors from the thousands generated. | The model includes irrelevant variables that capture random noise. |

| Inadequate Validation [29] | Relying only on internal validation (e.g., Leave-One-Out) without an external test set. | Gives an overly optimistic view of the model's predictive power. |

| Incorrect Alignment [29] | Misaligning molecules in the 3D grid, which introduces artificial variance in the descriptor values. | The model learns from alignment errors rather than true bioactive features. |

Q2: How can pharmacophore mapping improve the robustness of a 3D-QSAR model?

Pharmacophore mapping provides a complementary, hypothesis-driven approach that constrains the model to focus on essential interaction features. It defines the minimal set of structural features—such as hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic rings—required for biological activity [30]. When used to guide the alignment of molecules in a 3D-QSAR study, it ensures that the model is built upon a biologically relevant superposition, reducing the risk of learning from spurious correlations. Furthermore, the key features identified in a pharmacophore model can be used to pre-filter compound libraries, ensuring that the training set molecules are relevant and share a common binding mode, which strengthens the resulting model [31].

Q3: What are the key differences between CoMFA and CoMSIA, and how does the choice impact overfitting?

Both Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) are core 3D-QSAR techniques, but their methodological differences significantly impact their susceptibility to overfitting.

| Feature | CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) | CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis) |

|---|---|---|

| Field Calculation | Calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulomb) potentials on a 3D grid [29] [32]. | Uses Gaussian-type functions to evaluate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields [29]. |

| Sensitivity to Alignment | Highly sensitive; precise molecular alignment is crucial [29]. | More robust to small misalignments due to the Gaussian functions [29]. |

| Risk of Overfitting | Can be higher if alignment is imperfect, as noise from misalignment is modeled. | Potentially lower for diverse datasets, as the smoothed fields are less prone to abrupt changes. |

| Recommended Use Case | Ideal for closely related congeneric series with a high degree of structural similarity. | Better suited for structurally diverse datasets where a perfect common alignment is difficult to achieve. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Cross-Validation Score but Poor External Predictivity

This is a classic symptom of an overfitted model. The model appears excellent during training but fails to predict the activity of new, unseen anticancer compounds.

Step-by-Step Diagnostic and Solution Protocol:

Diagnose the Applicability Domain (AD):

- Use leverage analysis (Williams plot) to determine if the poorly predicted test compounds fall outside your model's AD [32]. A compound with high leverage is structurally different from the training set and its prediction is unreliable.

- Statistically, the AD is defined by the leverage threshold, h = 3p/n, where p is the number of model descriptors and n is the number of training compounds [32].

Reduce Descriptor Dimensionality:

- Action: Employ feature selection techniques. Genetic Algorithms (GA) are highly effective for selecting an optimal, small subset of descriptors from the thousands of grid-based CoMFA/CoMSIA variables [32] [33].

- Protocol: a. Use software like QSARINS or SYBYL that implements GA or other feature selection methods. b. Set the algorithm to minimize the number of descriptors while maximizing the cross-validated R² (q²). c. Build a new model with the selected descriptors.

Re-evaluate Molecular Alignment:

- Action: Verify and potentially correct the alignment of your training and test set molecules. The alignment should be based on a experimentally known active conformation (e.g., from a protein-ligand crystal structure) or a robust common pharmacophore [31] [29].

- Protocol: a. Superimpose molecules based on a maximum common substructure (MCS) or a pharmacophore hypothesis. b. Ensure the alignment reflects a plausible binding mode to the biological target.

Validate with a Larger Test Set:

- Action: If possible, secure more test compounds. A common rule of thumb is to have a training set 3-4 times larger than the number of descriptors used in the final model. Reserve a significant portion of your data (20-30%) exclusively for external testing [2].

Problem 2: Uninterpretable or Chemically Illogical 3D Contour Maps

Contour maps from a robust 3D-QSAR model should provide clear, spatially distinct regions that a medicinal chemist can use for design. Uninterpretable maps often indicate a flawed model.

Step-by-Step Diagnostic and Solution Protocol:

Check Training Set Diversity and Activity Range:

- Diagnosis: Ensure your training set includes compounds with a wide range of activity (ideally at least 3-4 orders of magnitude in IC50 values) and meaningful structural variation around a common core [31] [29]. A set of nearly identical, highly active compounds will not generate a meaningful SAR.

- Solution: Curate a new training set that includes active, moderately active, and some inactive analogues to clearly define the steric and electrostatic boundaries for activity.

Increase the Data-to-Descriptor Ratio:

- Diagnosis: The number of training compounds (n) is too low compared to the number of field descriptors (p). A ratio of n/p < 5 is a red flag.

- Solution: a. Increase n: Add more diverse training compounds with measured activity. b. Decrease p: As in Problem 1, use feature selection (e.g., Genetic Algorithm) to reduce the number of descriptors before generating the final contour maps [33].

Switch from CoMFA to CoMSIA:

- Action: CoMSIA uses Gaussian functions, which produce smoother and often more interpretable contour maps that are less sensitive to small changes in molecular orientation and do not exhibit the extreme steric fields sometimes seen in CoMFA [29]. This can lead to more chemically intuitive design suggestions.

Experimental Protocol: Building a Validated 3D-QSAR Model with Pharmacophore-Guided Alignment

This protocol outlines a best-practice methodology to minimize overfitting from the outset, integrating pharmacophore mapping for robust structural insights.

1. Data Set Curation and Preparation

- Source: Collect a minimum of 20-30 compounds with consistently measured anticancer activity (e.g., pIC50 or pGI50) from a single biological assay [31] [34].

- Activity Range: Ensure activities span a sufficient range (e.g., 3-4 log units). Categorize compounds as active, moderately active, and inactive.

- Chemical Structure Preparation: a. Draw 2D structures in a tool like BIOVIA Draw or ChemDraw. b. Convert to 3D and perform energy minimization using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., UFF) or quantum mechanical method (e.g., DFT/B3LYP) to obtain a low-energy conformation [34] [29].

2. Pharmacophore Model Generation and Validation

- Generation: Use the 3D QSAR Pharmacophore Generation module in software like Discovery Studio. Input the training set compounds and their activities to generate hypotheses [31].

- Selection Criteria: Choose the best hypothesis based on high correlation coefficient (R²), low total cost, and a reasonable root mean square deviation (RMSD) [31].

- Validation: Validate the hypothesis using a test set of compounds and Fischer's randomization test at a 95% confidence level to confirm its statistical significance [31].

3. Molecular Alignment

- Method: Superimpose all training and test set molecules onto the selected pharmacophore hypothesis. This aligns the compounds based on essential chemical features rather than a maximum common substructure, which is particularly useful for scaffolds with significant diversity [31] [29].

4. 3D Field Descriptor Calculation

- Software: Use tools like SYBYL for CoMFA/CoMSIA.

- Process: Place the aligned molecules in a 3D grid. Calculate interaction energies between a probe atom and each molecule at every grid point.

- Descriptors: Standard CoMFA calculates steric (van der Waals) and electrostatic (Coulombic) fields. CoMSIA can additionally calculate hydrophobic and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor fields [29].

5. Model Building and Validation

- Algorithm: Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate the field descriptors with the biological activity data [29].

- Internal Validation: Perform Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation to obtain the cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²). A q² > 0.5 is generally considered acceptable [29] [33].

- External Validation: Use the reserved test set (not used in training or pharmacophore generation) to calculate the predictive R² (pred_r²). This is the gold standard for assessing predictive power [2] [33].

- Statistical Scrutiny: The final model should have a high q² and pred_r², a low standard error of estimate, and a reasonable number of principal components to avoid overfitting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

| Item Name | Category | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Studio (BIOVIA) | Software Suite | Integrated environment for pharmacophore modeling (Hypogen), 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and simulation [31]. |

| SYBYL | Software Suite | Industry-standard platform for performing CoMFA and CoMSIA analyses, including advanced visualization of contour maps [29]. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Descriptor Calculator | Open-source software for calculating a wide range of 2D molecular descriptors, useful for initial compound profiling [34] [2]. |

| QSARINS | QSAR Modeling Software | Specialized software with built-in genetic algorithm for feature selection and robust validation methods to combat overfitting [32]. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Open-source toolkit for converting 2D structures to 3D, energy minimization, and molecular alignment tasks [2] [29]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Computational Method | An optimization technique used for selecting the most relevant subset of descriptors from a large pool, crucial for preventing overfitting [32] [33]. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Statistical Algorithm | The core regression method used in 3D-QSAR to handle the high number of correlated field descriptors and build the predictive model [29] [28]. |

Experimental Workflow and Model Validation Logic

3D-QSAR Model Development Workflow

Model Validation and Diagnosis Logic

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is dimensionality reduction critical in 3D-QSAR modeling, especially for anticancer compound research?

Dimensionality reduction is essential because 3D-QSAR models use very high-dimensional descriptors. Methods like CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) calculate steric and electrostatic interaction energies at thousands of grid points surrounding a set of aligned molecules [29]. This creates a vast number of descriptors, often far exceeding the number of compounds in a typical dataset. This high dimensionality, known as the "curse of dimensionality," drastically increases the risk of the model learning noise and random correlations instead of the true structure-activity relationship, leading to overfitting [35]. For anticancer research, where datasets can be small and costly to generate, building a robust and generalizable model is paramount for accurately predicting the activity of new compounds.

Q2: My 3D-QSAR model performs well on training data but poorly on new compounds. Is overfitting the cause, and how can dimensionality reduction help?

Yes, this is a classic symptom of overfitting. It means your model has likely memorized the noise and specific patterns in your training set rather than learning the underlying relationship that applies to new data [35]. Dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA and feature selection mitigate overfitting by simplifying the model. They remove redundant or irrelevant features, which are a primary source of noise. By reducing the number of features, these techniques force the model to focus on the most significant patterns that govern biological activity, ultimately improving its predictive performance on unseen anticancer compounds [35].

Q3: What is the practical difference between Feature Selection and PCA for my 3D-QSAR analysis?

The difference lies in how they handle the original feature space.

- Feature Selection is a filtering process. It identifies and keeps the most important original descriptors from your model (e.g., specific steric or electrostatic fields from a CoMFA grid) while discarding the rest. This results in a subset of your original variables, making the model highly interpretable. You can directly see which specific regions in the 3D space around your molecules are critical for activity [2].

- PCA (Principal Component Analysis) is a transformation process. It creates a new, smaller set of features called Principal Components (PCs). These PCs are linear combinations of all the original descriptors, transformed to be uncorrelated and ordered by how much variance they capture. While PCA is excellent for handling multicollinearity and noise reduction, the resulting PCs are mathematical constructs that can be difficult to relate back to the original chemical or structural features [36] [35].

Q4: How do I know if I've reduced the dimensions sufficiently without losing critical chemical information?

Finding the right balance is key. A common and effective method is to use cross-validation. You build models with a varying number of features or principal components and plot the model's cross-validated performance metric (like Q²). The point where the Q² plateaus or begins to decline indicates that adding more features is no longer improving (or is starting to harm) the model's predictive power [29] [2]. Additionally, you should monitor the total variance explained by the selected PCs; a widely used threshold is to retain enough components to explain >80-85% of the cumulative variance in your original data [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model has a high performance on the training set but low predictive power on the test set.

- Potential Cause: Overfitting due to high-dimensional descriptor data with many irrelevant features.

- Solution:

- Apply Feature Selection: Use methods like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) or feature importance scores from Random Forest to select the most relevant descriptors [5] [2].

- Apply PCA: Use PCA to transform your high-dimensional descriptors into a smaller set of principal components that capture the essential variance.

- Re-validate: Rebuild your model (e.g., PLS regression) using the reduced feature set and rigorously validate its performance using an external test set [2].

Problem: The 3D-QSAR model is computationally intensive and slow to run.

- Potential Cause: The high dimensionality of 3D molecular descriptors (e.g., thousands of grid points from CoMFA) creates a computational bottleneck [29].

- Solution:

- Dimensionality Reduction as a Preprocessing Step: Use PCA or feature selection to drastically reduce the number of variables before model building.

- Benchmark Methods: Consider using efficient non-linear dimensionality reduction methods like UMAP or t-SNE, which have been shown to perform well on high-dimensional biological data [36].

Problem: After using PCA, the model is no longer chemically interpretable.

- Potential Cause: Principal Components are mathematical constructs that combine original features, making it hard to trace which structural properties affect activity.

- Solution:

- Use Feature Selection: If interpretability is a priority, prefer feature selection methods (filter, wrapper, or embedded methods) that retain the original, meaningful descriptors [2].

- Analyze Component Loadings: If using PCA, examine the loadings of the original features on the most important PCs. Features with high absolute loadings contribute most to that component and are likely to be chemically significant [5].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing PCA in a 3D-QSAR Workflow

The following protocol outlines how to integrate PCA into a standard 3D-QSAR modeling process for anticancer compounds.

Step-by-Step Guide

Data Curation and 3D Alignment

- Curate a dataset of anticancer compounds with consistent experimental IC50 values [37] [29].

- Generate and optimize 3D molecular structures using tools like RDKit or Sybyl [29].

- Perform molecular alignment based on a common scaffold or maximum common substructure to ensure a consistent reference frame [29].

Descriptor Calculation

- Calculate 3D molecular field descriptors. For example, using CoMFA, place each aligned molecule in a 3D grid and calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulomb) energy fields at each grid point using a probe atom. This results in a high-dimensional descriptor matrix X [29].

Data Preprocessing

- Standardize the descriptor matrix X by scaling each descriptor (each column) to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. This step is critical for PCA [2].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

- Apply PCA to the standardized matrix X.

- Retain the first k principal components that explain a sufficient amount (e.g., >80-85%) of the total cumulative variance in the data [35]. This creates a new, reduced feature matrix T (scores).

Model Building and Validation

This workflow is visualized in the diagram below.

Performance Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Methods

The following table summarizes the performance of various DR methods based on a benchmark study using drug-induced transcriptomic data, which shares characteristics with 3D-QSAR descriptor data [36].

| Method Category | Method Name | Key Strength | Performance in Preserving Structure | Best Use Case in QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | PCA (Principal Component Analysis) | Captures global variance efficiently; good for noise reduction. | Good global preservation. | Initial noise reduction, handling multicollinearity. |

| Non-Linear (Global & Local) | UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation) | Preserves both local and global data structure; computationally efficient. | High | Visualizing and reducing complex chemical space. |

| Non-Linear (Global & Local) | t-SNE (t-distributed SNE) | Excellent at preserving local clusters and neighborhoods. | High (local) | Exploring tight clusters of similar actives. |

| Non-Linear (Global & Local) | PaCMAP (Pairwise Controlled Manifold Approximation) | Robustly preserves both local and global structure without sensitive parameters. | High | General-purpose use on diverse molecular datasets. |