Building a Modern High-Throughput Pharmacophore Screening Pipeline: From AI-Driven Foundations to Clinical Hit Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on constructing and implementing a high-throughput pharmacophore virtual screening pipeline.

Building a Modern High-Throughput Pharmacophore Screening Pipeline: From AI-Driven Foundations to Clinical Hit Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on constructing and implementing a high-throughput pharmacophore virtual screening pipeline. It explores the foundational principles of pharmacophore modeling, details state-of-the-art methodological workflows that integrate machine learning and structure-based design, and offers strategies for troubleshooting and performance optimization. Furthermore, it presents rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses against other virtual screening techniques, illustrating how a well-constructed pharmacophore pipeline can significantly accelerate the identification of novel bioactive compounds in the era of billion-compound libraries.

Pharmacophore Modeling 2.0: Core Concepts and the Evolution to AI-Driven Screening

The pharmacophore concept, foundational to medicinal chemistry, has evolved significantly from its early definitions. According to the modern IUPAC definition, a pharmacophore is "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1]. This definition underscores that a pharmacophore is not a specific molecule or functional group, but an abstract concept representing the common molecular interaction capacities of a group of compounds toward their biological target [2] [3].

Contemporary pharmacophore modeling has transcended simple feature mapping, evolving into a sophisticated representation of three-dimensional interaction landscapes. This advanced approach captures the essential chemical features responsible for biological activity and their precise spatial relationships, enabling more accurate virtual screening and drug design [2] [4]. The modern pharmacophore represents a critical tool in computer-aided drug discovery (CADD), reducing the time and costs needed to develop novel therapeutic agents—a particularly valuable capability during health emergencies and in the advancing field of personalized medicine [2].

Key Concepts and Data Comparison

Modern pharmacophore models are built from key chemical features that facilitate supramolecular interactions with biological targets. The most significant pharmacophoric features include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), aromatic rings (AR), and metal coordinating areas [2]. These features are represented as geometric entities such as spheres, planes, and vectors in three-dimensional space, often supplemented with exclusion volumes to represent forbidden areas of the binding pocket [2].

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Functional Roles

| Feature Type | Symbol | Functional Role | Representation in Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | HBA | Forms hydrogen bonds with donor groups on target | Vector or sphere |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | HBD | Forms hydrogen bonds with acceptor groups on target | Vector or sphere |

| Hydrophobic Area | H | Engages in van der Waals interactions | Sphere |

| Positively Ionizable | PI | Forms electrostatic interactions/ salt bridges | Sphere |

| Negatively Ionizable | NI | Forms electrostatic interactions/ salt bridges | Sphere |

| Aromatic Ring | AR | Engages in cation-π or π-π stacking | Ring or plane center |

| Exclusion Volume | XVOL | Represents steric hindrance/ forbidden regions | Sphere |

The construction and application of pharmacophore models primarily follow two distinct methodologies, each with specific requirements and advantages as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Comparison of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Parameter | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Input Data | 3D structure of macromolecular target or target-ligand complex [2] | 3D structures of multiple known active ligands [2] [5] |

| Key Requirement | High-quality protein structure (X-ray, NMR, or homology model) [2] | Set of ligands with diverse structures but common biological activity [1] |

| Feature Generation | Analysis of binding site to identify interaction points [2] | Superimposition of active compounds to extract common features [5] |

| Spatial Constraints | Derived directly from binding site geometry [2] | Derived from conserved spatial arrangement across multiple ligands [2] |

| Best Application Context | Target with well-characterized structure; novel chemotypes [2] | Targets with unknown structure; scaffold hopping [1] |

| Common Software Tools | LigandScout, MOE [1] | Catalyst/HypoGen, Phase, DISCO, GASP [1] [5] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol generates pharmacophore models directly from the three-dimensional structure of a biological target, ideal for scenarios where high-resolution structural data is available [2].

Step 1: Protein Structure Preparation

- Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through computational methods like homology modeling or ALPHAFOLD2 [2].

- Critically evaluate structure quality, addressing issues such as missing residues, protonation states, and position of hydrogen atoms (typically absent in X-ray structures) [2].

- Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and optimize hydrogen bonding networks using molecular mechanics force fields [2].

Step 2: Binding Site Identification and Analysis

- Identify the ligand-binding site through analysis of protein-ligand co-crystal structures or using computational tools such as GRID or LUDI that detect potential binding sites based on geometric and energetic properties [2].

- For targets with known active ligands, the binding site can be inferred from the co-crystallized ligand position [2].

Step 3: Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Analyze the binding site to identify potential interaction points complementary to ligand features [2].

- Map key interaction features including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged interactions, and aromatic centers [2].

- If a protein-ligand complex is available, derive features directly from the ligand's functional groups involved in target interactions [2].

Step 4: Feature Selection and Model Validation

- Select the most relevant features essential for biological activity, removing those that don't strongly contribute to binding energy [2].

- Incorporate exclusion volumes (forbidden areas) to represent spatial restrictions from the binding site shape [2].

- Validate the model by screening a small set of known active and inactive compounds to assess its ability to distinguish between them [2].

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This approach develops pharmacophore models from a set of known active ligands, particularly valuable when the macromolecular target structure is unknown [2] [5].

Step 1: Compound Selection and Preparation

- Select a structurally diverse set of 20-30 known active compounds with measured biological activity against the target [5].

- Include inactive compounds if available to improve model selectivity [5].

- Prepare 3D structures of all compounds using tools like LigPrep or similar software, generating multiple low-energy conformers to account for molecular flexibility (typically 100-250 conformers per compound) [5].

Step 2: Molecular Alignment and Common Feature Identification

- Superimpose active compounds using point-based or property-based alignment techniques to identify common spatial arrangements [5].

- For point-based alignment, minimize Euclidean distances between corresponding atoms or chemical features [5].

- For property-based alignment, use molecular field descriptors to maximize overlap of interaction energies [5].

Step 3: Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation

- Extract common chemical features from the aligned molecule set, balancing generalizability with specificity [5].

- Define feature types (HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, etc.) with appropriate tolerance radii [5].

- Use algorithms such as HipHop (for qualitative models) or HypoGen (for quantitative models using activity data) to generate pharmacophore hypotheses [5].

Step 4: Model Validation and Refinement

- Validate the model against a test set of known active and inactive compounds not used in model generation [6].

- Assess model performance using statistical measures including enrichment factor, sensitivity, and specificity [6].

- Refine the model by adjusting feature definitions and spatial tolerances based on validation results [5].

Protocol 3: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

This protocol applies validated pharmacophore models to screen large compound libraries for novel hit identification [2] [7] [8].

Step 1: Database Preparation

- Select appropriate compound libraries for screening (commercial databases, in-house collections, or virtual combinatorial libraries) [7] [8].

- Convert 2D compound structures to 3D representations and generate multiple conformers to account for molecular flexibility using tools such as GINGER or similar conformer generation software [8].

Step 2: Pharmacophore Screening

- Use the pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen the prepared compound database [2] [8].

- Apply flexible search algorithms that allow limited deviation from ideal feature positions [2].

- Score and rank compounds based on their fit value to the pharmacophore hypothesis [2].

Step 3: Post-Screening Filtering and Analysis

- Apply additional filters including drug-likeness (Lipinski's Rule of Five), ADMET properties, and chemical diversity [7] [8].

- Perform visual inspection of top-ranking compounds to verify sensible alignment with pharmacophore features [7].

- Cluster results to select structurally diverse hits for further investigation [7].

Step 4: Experimental Validation

- Select 20-100 top-ranking compounds for experimental testing based on screening scores and structural diversity [7].

- Procure or synthesize selected compounds and evaluate their biological activity against the target [7].

- Use results to iteratively refine the pharmacophore model and screening strategy [7].

The High-Throughput Screening Pipeline

Integrating pharmacophore modeling into a high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) pipeline creates a powerful approach for rapid hit identification. A comprehensive HTVS pipeline combines multiple computational techniques to efficiently prioritize compounds for experimental testing [7] [8].

A notable application of this pipeline demonstrated the identification of novel c-Src kinase inhibitors with anticancer potential. Researchers screened 500,000 compounds from the ChemBridge library using a pharmacophore model, followed by molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and experimental validation. This approach identified several promising inhibitors, with the top hit demonstrating an IC50 of 517 nM against c-Src kinase and significant anticancer activity across multiple cancer cell lines [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Modern Pharmacophore Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Structure-based & ligand-based pharmacophore modeling [1] | Advanced pharmacophore modeling with intuitive visualization [1] |

| Catalyst/HypoGen | Software | Ligand-based 3D QSAR pharmacophore generation [5] | Building quantitative pharmacophore models from activity data [5] |

| Phase | Software | Pharmacophore perception, 3D QSAR, database screening [1] | Comprehensive pharmacophore modeling and screening suite [1] |

| MOE | Software | Molecular modeling and simulation with pharmacophore capabilities [1] | Integrated drug discovery platform with pharmacophore modules [1] |

| ICM-Pro | Software | Molecular docking and virtual screening [8] | Structure-based screening and binding pose prediction [8] |

| GINGER | Software | GPU-accelerated conformer generation [8] | Rapid generation of conformer libraries for large databases [8] |

| RDKit | Open-source | Cheminformatics and machine learning [4] | Chemical feature identification and molecular processing [4] |

| ChemBridge Library | Compound Database | 500,000+ small molecules for screening [7] | Commercially available diverse compound collection [7] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of pharmacophore modeling continues to evolve with emerging methodologies that enhance its predictive power and application scope. Deep learning approaches are now being integrated with traditional pharmacophore methods, as demonstrated by PGMG (Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation), which uses graph neural networks to encode spatially distributed chemical features and transformer decoders to generate novel bioactive molecules [4]. This integration addresses the challenge of data scarcity, particularly for novel target families where limited activity data is available [4].

Another significant advancement is the incorporation of pharmacophore concepts in safety pharmacology. Pharmacophore-based 3D QSAR models are being employed to predict off-target interactions against liability targets such as the adenosine receptor 2A (A2A), enabling early identification of potential adverse effects during drug development [6]. This application is particularly valuable as it functions effectively even with chemotypes drastically different from training compounds, addressing a key limitation of traditional QSAR approaches [6].

The ongoing development of hybrid methods that combine pharmacophore screening with molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations represents the cutting edge of virtual screening pipelines [7] [8]. These integrated approaches leverage the complementary strengths of different computational techniques, improving the accuracy of hit identification while reducing false positives [7]. As these methodologies mature, pharmacophore-based strategies will continue to play an increasingly vital role in accelerating drug discovery and addressing the challenges of cost-effective therapeutic development.

Computational approaches are indispensable in modern drug discovery, with ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) and structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) representing two fundamental strategies [9] [10]. LBVS leverages known active ligands to identify new hits through pattern recognition of structural or pharmacophoric features, while SBVS utilizes the three-dimensional structure of the target protein to rationally identify compounds that fit within the binding pocket [11] [10]. Individually, these approaches possess inherent limitations; LBVS may lack structural novelty, whereas SBVS can be computationally intensive and reliant on high-quality protein structures [9]. The integration of these complementary methods creates a powerful synergistic workflow, mitigating individual weaknesses and providing a more robust framework for identifying and optimizing novel therapeutics [11] [9] [10]. This application note details protocols and best practices for implementing these combined strategies, framed within the context of a high-throughput pharmacophore screening pipeline.

Comparative Analysis of Virtual Screening Methods

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of LBVS and SBVS approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Ligand-Based and Structure-Based Virtual Screening Methods

| Feature | Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) | Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Infers activity from known active ligands using similarity or QSAR models [11] [9] | Predicts interaction based on the 3D structure of the target protein [11] [10] |

| Structural Requirement | Does not require a protein structure [10] | Requires an experimental or predicted protein structure [10] |

| Key Strengths | Fast, cost-effective computation; excellent for scaffold hopping and screening ultra-large libraries [11] [12] | Provides atomic-level interaction insights; often better library enrichment [11] |

| Major Limitations | Limited chemical novelty if known actives are sparse; can introduce bias [9] [10] | Computationally expensive; accuracy depends on quality of protein structure and scoring functions [9] [10] |

| Typical Applications | Initial filtering of ultra-large chemical libraries; hit identification when structural data is limited [11] [12] | Detailed binding mode analysis; lead optimization; virtual screening when a high-quality structure is available [11] [10] |

Integrated Workflow Strategies

The combination of LBVS and SBVS can be operationalized through sequential, parallel, or hybrid strategies, each offering distinct advantages.

Sequential Combination

This funnel-based approach applies LBVS and SBVS in consecutive steps for computational economic benefits [9] [10]. Large compound libraries are first rapidly filtered using fast ligand-based methods like 2D/3D similarity search or QSAR models. The resulting subset of promising compounds then undergoes more computationally intensive structure-based techniques like molecular docking [11] [10]. This workflow is highly efficient, particularly when resources or time are constrained, as it focuses expensive calculations on a pre-enriched set of candidates [10].

Parallel and Hybrid Combination

In parallel screening, LBVS and SBVS are run independently on the same compound library. The results are then combined using consensus scoring frameworks [11] [9]. One can select top-ranked compounds from both lists to maximize the chance of recovering actives, or employ a hybrid (consensus) scoring method that multiplies or averages the ranks from each method to create a unified ranking [11]. This consensus approach favors compounds that perform well across both methods, thereby increasing confidence in selecting true positives and reducing the impact of limitations inherent in any single method [11] [9].

Detailed Application Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

This protocol, adapted from studies on XIAP and KHK-C inhibitors, outlines the steps for identifying hits using a structure-based pharmacophore model [13] [14].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) Structure | Provides the experimental 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., XIAP PDB: 5OQW) for pharmacophore modeling [14]. |

| LigandScout Software | Advanced molecular design software used to generate structure-based pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes [14]. |

| ZINC/Enamine REAL Database | Curated collections of commercially available chemical compounds (over 40 billion molecules in Enamine REAL) for virtual screening [12] [14]. |

| DUDE Decoy Set | A database of useful decoys used to validate the pharmacophore model's ability to distinguish active compounds from inactives [14]. |

- Structure Preparation and Model Generation:

- Obtain a high-quality experimental structure of the target protein in complex with a potent inhibitor from the PDB.

- Using molecular design software (e.g., LigandScout), load the protein-ligand complex and generate a structure-based pharmacophore model. The model will identify key chemical features (e.g., hydrophobics, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, positive ionizable areas) and exclusion volumes based on the interaction pattern between the protein and the reference ligand [14].

- Pharmacophore Model Validation:

- Validate the model using a set of known active compounds and a large set of decoy molecules (e.g., from DUDE) [14].

- Perform an initial screening of this combined set. Calculate the early enrichment factor (EF) and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). A high EF1% (e.g., 10.0) and AUC value (e.g., 0.98) indicate a model capable of reliably distinguishing true actives [14].

- Virtual Screening:

Protocol 2: A Hybrid LBVS/SBVS Screening Pipeline for Ultra-Large Libraries

This protocol leverages the scalability of modern LBVS tools for initial filtering, followed by structure-based refinement.

- Ligand-Based Ultra-High-Throughput Screening:

- Begin with an ultra-large chemical library, such as the Enamine REAL Space (40 billion compounds) [12].

- Employ a high-throughput LBVS system (e.g., BIOPTIC B1, infiniSee, or FastROCS) to screen the entire library. These systems use efficient algorithms, such as transformers or topological fingerprints, to rapidly identify compounds similar to known actives based on chemical structure or pharmacophoric patterns [11] [12].

- The goal of this step is to reduce the library size by several orders of magnitude, yielding a manageable subset (e.g., thousands of compounds) for subsequent analysis.

- Structure-Based Docking and Refinement:

- Use a high-quality protein structure (experimental or AI-predicted, like from AlphaFold) for molecular docking.

- Dock the enriched compound subset from the previous step into the target's binding pocket. Note that while AlphaFold has expanded structural coverage, its models can be single-conformation and may require refinement for optimal docking performance [15] [11].

- Score and rank the resulting docking poses based on predicted interaction energies.

- Consensus Scoring and Hit Selection:

- Combine the ligand-based similarity scores and the structure-based docking scores using a consensus method (e.g., rank multiplication or averaging) to create a unified ranking [11] [9].

- Select the top-ranked compounds for experimental validation. This integrated prioritization helps cancel out errors inherent in each individual method and increases confidence in the final selection [11] [9].

Case Study & Data Presentation

Prospective Application on LRRK2 for Parkinson's Disease

In a prospective application targeting LRRK2, a high-value target for Parkinson's disease, the BIOPTIC B1 LBVS system was used to screen the 40-billion-molecule Enamine REAL Space library. This system successfully identified novel ligands binding to both wild-type and G2019S-mutant LRRK2 with dissociation constants (Kd) as low as 110 nM, demonstrating the power of efficient LBVS for novel hit identification from an ultra-large chemical space [12].

Performance of Hybrid Models in Lead Optimization

A collaboration between Optibrium and Bristol Myers Squibb on LFA-1 inhibitor optimization demonstrated the quantitative benefit of a hybrid approach. Predictions from a 3D ligand-based QSAR model (QuanSA) and a structure-based free energy perturbation (FEP) method were averaged, resulting in a model that performed better than either method alone [11]. The mean unsigned error (MUE) dropped significantly, achieving a high correlation between experimental and predicted affinities through partial cancellation of errors from the individual methods [11].

Table 3: Quantitative Results from Hybrid Affinity Prediction for LFA-1 Inhibitors

| Prediction Method | Reported Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Based (QuanSA) | High accuracy in predicting pKi [11] | Generalizes well across chemically diverse ligands [10] |

| Structure-Based (FEP+) | High accuracy in predicting pKi [11] | High accuracy for small structural modifications [10] |

| Hybrid Model (Averaging) | Lower Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) than either method alone [11] | Reduces prediction error via cancellation of individual method errors [11] |

Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of a hybrid virtual screening pipeline requires careful consideration of several factors. For LBVS, the availability and quality of known active ligands are critical, as a limited or biased set can constrain chemical diversity [10]. For SBVS, the quality of the protein structure is paramount; while AlphaFold models have greatly expanded access, they may represent a single conformational state and can have inaccuracies in side-chain positioning, potentially impacting docking accuracy [15] [11]. Finally, the choice of combination strategy—sequential, parallel, or hybrid—should be guided by the project's specific goals, available data, and computational resources [11] [9].

The evolution of virtual screening (VS) represents a paradigm shift from the use of rigid, rule-based filters toward dynamic, intelligent models capable of learning and prediction. In modern drug discovery, particularly within high-throughput pharmacophore virtual screening pipelines, this transition is critical for exploring ultra-large chemical spaces efficiently. Pharmacophore models, defined as abstract descriptions of structural features essential for a molecule's biological activity, have long been foundational to ligand-based drug design [16]. Traditionally, these models served as static filters for compound prioritization. However, the integration of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) has transformed them into dynamic, predictive engines that enhance screening accuracy, speed, and interpretability [16] [17]. This integration addresses key limitations of traditional methods, including their inability to handle vast chemical libraries and reliance on scarce activity data [18]. By embedding pharmacophore constraints within ML/DL frameworks, researchers can now conduct billion-compound screens in hours rather than months, accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic agents for targets such as GSK-3β in Alzheimer's disease and monoamine oxidases in neurological disorders [19] [18] [20].

Key Applications and Methodological Advances

The synergy of pharmacophore modeling with ML/DL has spawned several innovative frameworks. These applications demonstrate a progression from using ML to augment specific screening steps to fully integrated, end-to-end deep learning systems.

Integrated ML-DL Virtual Screening Frameworks

Zhou et al. developed a novel two-stage virtual screening framework that strategically combines an interpretable machine learning model with a deep learning-based docking platform to identify natural GSK-3β inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease [19]. Their approach first employs an interpretable random forest (RF) model with a high predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.99) for initial compound filtering. The model's decisions are made transparent using SHAP analysis, which uncovers key fingerprint features driving activity predictions, thus addressing the "black-box" limitation of many complex models [19]. In the second stage, compounds passing the RF filter are subjected to deep learning-based molecular docking using KarmaDock (NEF0.5% = 1.0), which provides more refined binding affinity assessments [19]. This integrated pipeline was applied to a curated natural product library of 25,000 compounds, leading to the identification of three promising candidates from Clausena and Psoralea genera with predicted favorable blood-brain barrier permeability and low neurotoxicity [19]. The workflow demonstrates how combining different AI modalities can enhance both screening accuracy and the interpretability of results.

Pharmacophore-Guided Deep Molecular Generation

A groundbreaking application called Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation (PGMG) represents the cutting edge in dynamic model integration [4]. PGMG utilizes pharmacophore hypotheses as a bridge to connect different types of activity data, addressing the critical challenge of data scarcity in drug discovery, particularly for novel targets [4]. The approach employs a graph neural network to encode spatially distributed chemical features of a pharmacophore and a transformer decoder to generate molecular structures that match these features [4].

Notably, PGMG introduces a latent variable to model the many-to-many relationship between pharmacophores and molecules, significantly boosting the diversity of generated compounds [4]. During validation, PGMG demonstrated strong performance in unconditional molecule generation, achieving high scores in novelty and the ratio of available molecules while maintaining physicochemical property distributions similar to training data [4]. This capability enables de novo drug design in both ligand-based and structure-based scenarios, providing unprecedented flexibility in generating targeted compound libraries for virtual screening campaigns.

Machine Learning-Accelerated Pharmacophore Screening

To address the computational bottleneck of traditional docking, researchers have developed ML models that predict docking scores directly from molecular structures, dramatically accelerating the screening process. In a study focused on monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, Świątek et al. created an ensemble ML model using multiple molecular fingerprints and descriptors to predict Smina docking scores, bypassing the need for explicit docking calculations [18]. This approach achieved a remarkable 1000-fold acceleration in binding energy predictions compared to classical docking-based screening [18]. The methodology employed pharmacophore constraints to filter the ZINC database before applying the predictive model, leading to the identification of 24 synthesized compounds, with several showing weak MAO-A inhibition activity [18]. This hybrid approach demonstrates the power of ML to overcome computational barriers in large-scale pharmacophore-based screening while maintaining reasonable accuracy.

End-to-End Deep Learning Pipelines

Fully integrated deep learning pipelines represent the most advanced manifestation of the dynamic model paradigm. VirtuDockDL is a streamlined Python-based platform that employs a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to predict compound effectiveness, combining both ligand- and structure-based screening approaches [21]. The system processes molecules as graph structures, extracting both topological features and physicochemical descriptors to make accurate binding affinity predictions [21]. In benchmarking studies, VirtuDockDL achieved exceptional performance (99% accuracy, F1 score of 0.992, and AUC of 0.99) on the HER2 dataset, surpassing both traditional docking software and other deep learning tools [21].

Similarly, PharmacoNet has emerged as the first deep learning framework specifically designed for pharmacophore modeling toward ultra-fast virtual screening [20]. This system offers fully automated, protein-based pharmacophore modeling and evaluates ligand potency using a parameterized analytical scoring function [20]. In a dramatic demonstration of its capabilities, PharmacoNet successfully screened 187 million compounds against cannabinoid receptors in just 21 hours on a single CPU, identifying selective inhibitors with reasonable accuracy compared to traditional docking methods [20]. This unprecedented throughput highlights the transformative potential of deep learning in pharmacophore modeling for ultra-large-scale virtual screening.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Integrated ML/DL Virtual Screening Approaches

| Method/Platform | Key Innovation | Reported Performance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated RF + KarmaDock [19] | Interpretable ML combined with DL docking | RF AUC = 0.99; KarmaDock NEF0.5% = 1.0 | Natural GSK-3β inhibitor identification |

| PGMG [4] | Pharmacophore-guided molecular generation | High novelty & diversity; maintains chemical property distributions | De novo molecular design for novel targets |

| ML-accelerated MAO screening [18] | Ensemble ML predicting docking scores | 1000x faster than classical docking; identified active MAO-A inhibitors | Pharmacophore-constrained MAO inhibitor discovery |

| VirtuDockDL [21] | GNN-based binding affinity prediction | 99% accuracy, F1=0.992, AUC=0.99 (HER2 dataset) | Multi-target virtual screening (VP35, HER2, TEM-1, CYP51) |

| PharmacoNet [20] | DL-guided pharmacophore modeling | Screened 187M compounds in 21 hours on single CPU | Ultra-large-scale CB receptor inhibitor screening |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing integrated machine learning and deep learning approaches into pharmacophore-based virtual screening pipelines, based on established protocols from recent literature.

Protocol for Automated Virtual Screening with ML Integration

Barbosa Pereira et al. described a comprehensive protocol for an automated virtual screening pipeline that can be seamlessly integrated with machine learning components [22]. The protocol encompasses the following key steps:

Compound Library Generation:

- Compound libraries are assembled from publicly available databases such as ZINC [22] [18].

- Initial filtering is performed using drug-likeness rules (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) and structural diversity criteria.

- For natural product screening, specialized databases like TCMBank and HERB can be leveraged [19].

Receptor and Grid Box Setup:

- Protein structures are obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and prepared by removing water molecules and co-crystallized ligands, followed by hydrogen atom addition and energy minimization [18].

- The binding site is defined using a 3D grid box centered on reference ligands or known active site residues [22].

Molecular Docking and Evaluation:

Machine Learning Integration:

- Docking results from a representative compound subset train machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, GNN) to predict docking scores for remaining compounds [18] [21].

- Molecular fingerprints (ECFP, Morgan) and physicochemical descriptors (MW, LogP, TPSA) serve as model features [18] [21].

- The trained ML model rapidly prioritizes compounds from ultra-large libraries, focusing experimental validation on highest-ranked candidates [18] [20].

Implementation of Pharmacophore-Guided Deep Learning

For implementing pharmacophore-guided deep learning approaches like PGMG, the following protocol, adapted from Seo et al., is recommended [4]:

Pharmacophore Definition and Representation:

- Ligand-based pharmacophores: Derived by identifying common chemical features among known active compounds aligned in 3D space [4].

- Structure-based pharmacophores: Generated from protein-ligand complex structures by analyzing key interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions) [20].

- Pharmacophores are represented as complete graphs where nodes represent chemical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, charged groups) and edges represent spatial distances between features [4].

Model Architecture and Training:

- A Graph Neural Network encoder processes the pharmacophore graph to create a fixed-dimensional representation [4] [21].

- A transformer decoder generates molecular structures (as SMILES strings) conditioned on both the pharmacophore encoding and a latent variable that captures the diversity of possible solutions [4].

- The model is trained on general chemical databases (e.g., ChEMBL) without target-specific activity data, enhancing its generalizability to novel targets [4].

Molecular Generation and Validation:

- Given a target pharmacophore, multiple latent variables are sampled to generate diverse molecules that match the constraint [4].

- Generated molecules are evaluated for drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, and potential off-target effects [4].

- Top candidates undergo molecular dynamics simulations to confirm binding stability and interaction conservation [19].

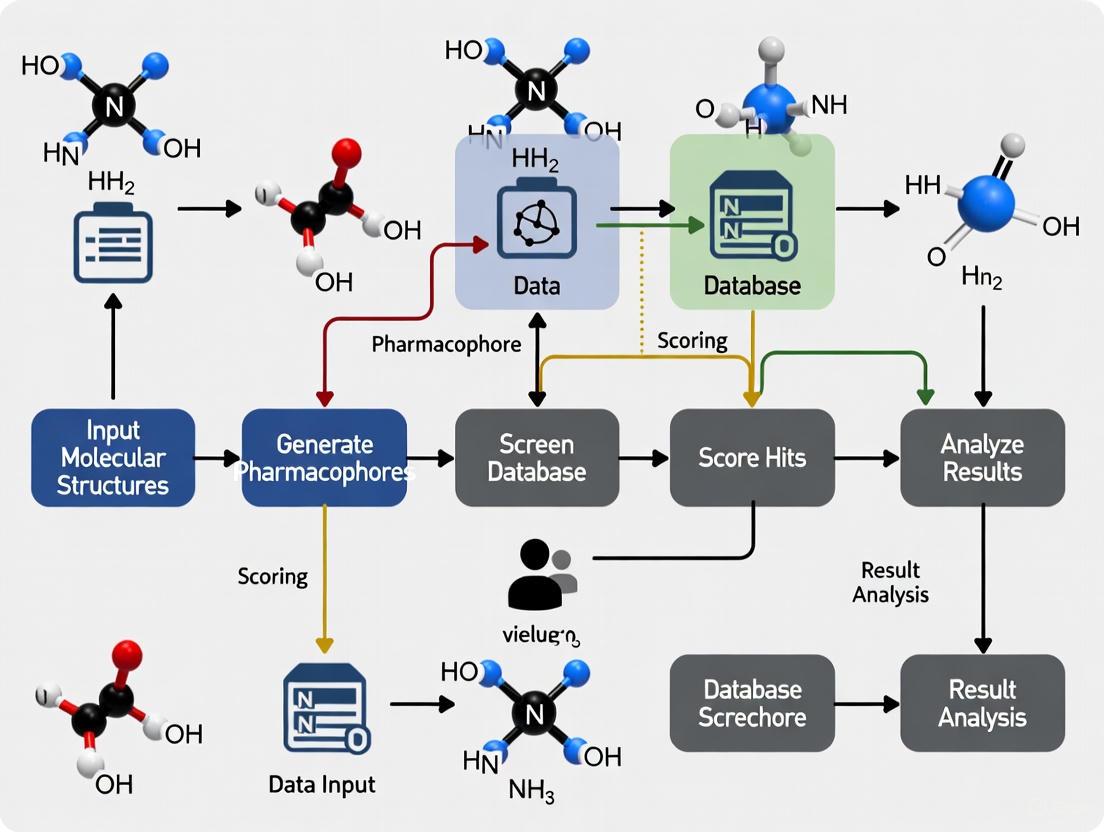

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated pharmacophore virtual screening pipeline, highlighting the seamless combination of traditional methods with machine learning and deep learning components:

Integrated Pharmacophore Screening Workflow

This workflow demonstrates the dynamic interplay between traditional computational methods (light blue) and advanced AI components (red), with pharmacophore modeling serving as the central bridge (green) connecting different data sources and screening approaches.

Successful implementation of integrated ML/DL pharmacophore screening requires both computational tools and experimental resources. The following table details key components of the research toolkit:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Integrated Pharmacophore Screening

| Category | Item/Resource | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | Docking Software | Predicts ligand-receptor binding poses and affinity | AutoDock Vina [22], Smina [18], KarmaDock [19] |

| ML/DL Frameworks | Implements machine learning and deep learning models | PyTorch Geometric [21], TensorFlow, scikit-learn | |

| Cheminformatics Libraries | Handles molecular representation and feature calculation | RDKit [4] [21], OpenBabel | |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Tools | Creates and validates pharmacophore hypotheses | PharmaGist, LigandScout, Phase | |

| Data Resources | Compound Databases | Sources of screening compounds | ZINC [22] [18], TCMBank [19], HERB [19] |

| Protein Structure Databases | Sources of target structural information | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [18] | |

| Bioactivity Databases | Sources of training data for ML models | ChEMBL [4] [18], BindingDB | |

| Experimental Validation Resources | Enzyme Assay Kits | Measures inhibitory activity and potency | MAO-A/MAO-B inhibition assay kits [18] |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Evaluates cellular efficacy and toxicity | Blood-brain barrier permeability models [19], neurotoxicity assays [19] | |

| Chemical Synthesis Equipment | Synthesizes predicted active compounds | Solid-phase synthesizers, HPLC purification systems [18] |

Performance Metrics and Validation

Rigorous validation is essential for establishing the reliability of integrated ML/DL pharmacophore screening approaches. The following metrics and validation strategies are commonly employed:

Table 3: Key Performance Metrics for ML/DL-Enhanced Pharmacophore Screening

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Interpretation and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Predictive Accuracy | AUC-ROC, Precision, Recall, F1-Score [21] | Measures classification performance in distinguishing actives from inactives |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Quantifies accuracy of continuous value predictions (e.g., binding affinity) | |

| Screening Efficiency | Enrichment Factors (EF) [19] | Measures the concentration of true actives in the top-ranked fraction compared to random selection |

| Throughput (compounds screened per unit time) [20] | Critical for ultra-large-scale screening campaigns | |

| Chemical Quality | Validity, Uniqueness, Novelty [4] | Assesses the chemical rationality and diversity of generated compounds |

| Drug-likeness (QED), Synthetic Accessibility (SA) | Evaluates practical potential of identified hits | |

| Experimental Validation | Inhibition Percentage/Potency (IC₅₀, Kᵢ) [18] | Confirms biological activity through experimental testing |

| Selectivity Ratios (e.g., MAO-A/MAO-B) [18] | Determines specificity for target isoforms or related targets |

The transition from rigid filters to dynamic models represents a fundamental advancement in pharmacophore-based virtual screening. By integrating machine learning and deep learning approaches, researchers can now conduct more accurate, efficient, and interpretable screening campaigns against ultra-large chemical libraries. The frameworks and protocols described herein provide actionable guidance for implementing these advanced methods, potentially accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents for a wide range of diseases. As these technologies continue to evolve, we anticipate further convergence of computational prediction and experimental validation, ultimately transforming the landscape of early-stage drug discovery.

The advent of ultra-large, make-on-demand chemical libraries, containing billions of readily synthesizable compounds, represents a transformative opportunity for early-stage drug discovery [23] [24]. These vast libraries, such as the Enamine REAL space with over 20 billion molecules, allow researchers to explore unprecedented areas of chemical space but also introduce significant computational challenges for virtual screening (VS) [23]. Traditional structure-based methods like molecular docking become prohibitively expensive in terms of time and computational resources when applied to such scales, creating a critical need for innovative approaches that balance speed, scalability, and interpretability [18] [25]. This application note examines current methodologies that address these challenges, focusing on integrated protocols for high-throughput pharmacophore-based virtual screening. We present quantitative benchmarks and detailed experimental workflows to guide researchers in implementing these advanced techniques, framed within the context of a comprehensive screening pipeline.

Performance Benchmarks of Advanced Screening Methods

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of key computational methods developed for screening ultra-large libraries, highlighting their advantages in speed and scalability.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Ultra-Large Library Screening Methods

| Method Name | Underlying Approach | Reported Speed/Scale | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| PharmacoNet [26] | Deep learning-guided pharmacophore modeling | 187 million compounds in 21 hours on a single CPU | Extremely fast, reasonably accurate vs. traditional docking |

| ML-Based Score Prediction [18] | Ensemble ML model predicting docking scores | 1000x faster than classical docking-based screening | Strong correlation to actual docking scores |

| REvoLd [23] | Evolutionary algorithm with flexible docking | 49,000 - 76,000 unique molecules docked per target | Hit rate improvement factor of 869x - 1622x vs. random |

| OpenVS (RosettaVS) [25] | AI-accelerated physics-based docking platform | Screening of multi-billion compound libraries in <7 days | 14% (KLHDC2) and 44% (NaV1.7) experimental hit rates |

These methods demonstrate that strategic computational approaches can overcome the traditional trade-offs between screening volume and practical resource constraints. The integration of machine learning and advanced algorithms with physics-based methods enables a more efficient exploration of the vast chemical space.

Experimental Protocols for High-Throughput Screening

Protocol: Deep Learning-Guided Pharmacophore Screening with PharmacoNet

PharmacoNet provides a fully automated, protein-based pharmacophore modeling framework for ultra-fast virtual screening [26].

- Input Preparation:

- Protein Structure: Obtain a 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from PDB). Preprocess by removing water molecules and co-crystallized ligands, and adding polar hydrogen atoms.

- Binding Site Definition: Define the coordinates of the binding pocket of interest if known.

- Pharmacophore Modeling:

- Run the PharmacoNet framework to automatically generate a pharmacophore model directly from the protein structure. This deep learning step identifies key interaction features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic patches, aromatic rings) essential for binding.

- Library Screening:

- Prepare the ultra-large chemical library in a suitable molecular format (e.g., SDF).

- Use PharmacoNet's parameterized analytical scoring function to rapidly evaluate and rank compounds from the library based on their complementarity to the generated pharmacophore.

- Hit Identification & Validation:

- Select the top-ranked compounds for further analysis.

- Optional: Perform coarse-grained pose alignment to generate approximate binding conformations.

- Validate top hits experimentally through synthesis and biochemical assays.

Protocol: Machine Learning-Accelerated Docking Score Prediction

This protocol uses ML models to approximate docking scores, bypassing the need for explicit, time-consuming docking simulations [18].

- Training Set Generation:

- Select a diverse, representative subset (e.g., 50,000-100,000 compounds) from the target ultra-large library.

- Perform molecular docking with your chosen software (e.g., Smina) against the target protein to generate a dataset of "true" docking scores for the subset.

- Model Training & Validation:

- Calculate multiple types of molecular fingerprints and descriptors (e.g., ECFP, MACCS, physicochemical properties) for every compound in the subset.

- Use these features and the corresponding docking scores to train an ensemble machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting).

- Validate the model using a held-out test set and scaffold-based splitting to ensure its ability to generalize to new chemotypes.

- Large-Scale Screening:

- Compute the same molecular features for all compounds in the full ultra-large library.

- Use the trained ML model to predict docking scores for the entire library.

- Rank the library based on the predicted scores to prioritize compounds for experimental testing.

Protocol: Evolutionary Library Exploration with REvoLd

REvoLd uses an evolutionary algorithm to efficiently search combinatorial chemical spaces without full enumeration, incorporating full ligand and receptor flexibility via RosettaLigand [23].

- Initialization:

- Define the combinatorial library by its constituent synthon lists and reaction rules.

- Generate an initial random population of 200 ligands from the available building blocks.

- Evolutionary Optimization:

- Docking & Scoring: Dock each ligand in the current population using a flexible docking protocol like RosettaLigand.

- Selection: Select the top 50 scoring individuals ("the fittest") to advance to the next generation.

- Reproduction:

- Crossover: Recombine well-suited ligands to create new offspring.

- Mutation: Apply mutation steps, such as switching single fragments for low-similarity alternatives or changing the reaction while searching for similar fragments.

- Repeat this process for 30 generations, which typically balances convergence and exploration.

- Hit Expansion:

- Conduct multiple independent runs (e.g., 20) with different random seeds to discover diverse scaffolds and high-scoring molecules.

Visualizing the High-Throughput Screening Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow of an integrated, high-throughput virtual screening pipeline, combining the strengths of the methods described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful implementation of a high-throughput pharmacophore screening pipeline relies on several key software tools and chemical resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ultra-Large Library Screening

| Item Name | Type | Function in Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Enamine REAL Library [23] [24] | Make-on-Demand Chemical Library | Provides access to billions of readily synthesizable compounds for virtual screening; a primary source for exploring vast chemical space. |

| ZINC Database [18] | Publicly Accessible Compound Library | A large, freely available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening and model training. |

| Rosetta Software Suite [23] [25] | Molecular Modeling Suite | Enables flexible protein-ligand docking (RosettaLigand) and provides the REvoLd application for evolutionary algorithm-based screening. |

| Smina [18] | Molecular Docking Software | Used for generating docking scores for training sets in ML-accelerated protocols; offers a customizable scoring function. |

| ROSHAMBO2 [27] | Molecular Alignment Tool | Optimizes molecular alignment using Gaussian volume overlaps with GPU acceleration, crucial for 3D similarity and pharmacophore modeling. |

The integration of advanced computational methods—including deep learning-guided pharmacophores, machine learning score predictors, and evolutionary algorithms—has created a powerful toolkit for navigating the challenges and opportunities presented by ultra-large chemical libraries. The protocols and benchmarks detailed in this application note demonstrate that it is now feasible to conduct screens of billions of compounds with unprecedented speed and scalability, while maintaining a degree of interpretability through structure-based approaches. By adopting these integrated pipelines, researchers can significantly accelerate the hit identification phase, reduce resource costs, and enhance the overall efficiency of the drug discovery process.

Architecting Your Screening Pipeline: A Step-by-Step Workflow from Query to Hit

In modern drug discovery, pharmacophore modeling serves as an abstract representation of the steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target. This blueprint provides detailed protocols for transforming either a protein structure or a set of active ligands into a screenable pharmacophore query, enabling virtual screening of compound libraries to identify novel bioactive molecules. The workflow is particularly valuable for high-throughput screening campaigns, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with experimental screening by prioritizing compounds with the highest potential for activity [2].

The fundamental principle underlying pharmacophore approaches is that molecules sharing common chemical functionalities in a similar spatial arrangement are likely to exhibit similar biological activity toward the same target. Pharmacophore models represent these chemical features as geometric entities—including hydrogen bond acceptors (A), hydrogen bond donors (D), hydrophobic areas (H), positively ionizable groups (P), negatively ionizable groups (N), and aromatic rings (R)—complemented by exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding site [2].

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

The structure-based approach generates pharmacophore models using the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or computational prediction methods like AlphaFold2 [2] [28]. This method extracts key interaction features directly from the binding site, providing a target-focused query that can identify diverse chemotypes capable of interacting with essential residues.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Protein Structure Preparation

- Input Requirement: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through computational prediction [2] [29].

- Structure Assessment: Critically evaluate structure quality by checking resolution (preferably <2.5 Å for X-ray structures), completeness, and the presence of artifacts [2].

- Structure Preparation:

- Add hydrogen atoms using molecular modeling software (e.g., Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard) [30].

- Assign appropriate protonation states to residues (especially His, Asp, Glu) at physiological pH.

- Optimize hydrogen-bonding networks.

- Remove crystallographic water molecules unless functionally important.

- Address missing residues or side chains through loop modeling if necessary.

- Energy Minimization: Perform restrained minimization using force fields (e.g., OPLS3/OPLS4) to relieve steric clashes while maintaining the overall protein fold [31].

Binding Site Identification and Analysis

- Binding Site Detection: Use computational tools such as GRID or LUDI to identify potential ligand-binding pockets based on geometric and energetic properties [2].

- Site Characterization: Manually inspect the binding site if structural information about known ligands is available, noting key residues involved in molecular recognition.

- Volume Generation: Define the binding site volume using the bound ligand or by creating a grid around the predicted binding pocket.

Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Feature Mapping: Identify potential interaction points within the binding site using software such as LigandScout or Schrödinger Phase [30] [31].

- Feature Selection: Select features that are evolutionarily conserved or known from mutagenesis studies to be critical for function, typically 4-7 features for an effective model [2].

- Exclusion Volumes: Add exclusion volumes to represent regions where ligand atoms would experience steric clashes, improving model selectivity [2].

- Spatial Optimization: Adjust feature positions and tolerances to balance model specificity and generality.

Table 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Feature Types and Their Chemical Significance

| Feature Type | Symbol | Chemical Significance | Common Protein Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | A | Atoms that can accept H-bonds | Ser, Thr, Tyr OH; backbone NH |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | D | Atoms that can donate H-bonds | Asp, Glu COO⁻; backbone C=O |

| Hydrophobic | H | Non-polar surface areas | Val, Ile, Leu, Phe, Trp side chains |

| Positively Ionizable | P | Basic groups (amines) | Asp, Glu COO⁻ |

| Negatively Ionizable | N | Acidic groups (carboxylic acids) | Arg, Lys, His side chains |

| Aromatic Ring | R | π-electron systems | Phe, Tyr, Trp side chains (π-stacking) |

| Exclusion Volume | XVOL | Sterically forbidden regions | Protein backbone and side chains |

Model Validation

- Decoy Screening: Test the model against a set of known actives and decoys from databases like DUD-E [32].

- Enrichment Calculation: Evaluate performance using enrichment factor (EF) and BEDROC metrics to ensure the model can prioritize active compounds [32].

- Feature Importance: Verify that no single feature disproportionately drives screening results unless biologically justified.

Figure 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

When the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling provides an effective alternative. This approach develops models based on the physicochemical properties and spatial arrangement of known active ligands, under the principle that compounds with similar activity share common interaction features with the target [2] [33]. The method often incorporates 3D quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) analysis to correlate pharmacophore features with biological activity levels.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Ligand Set Selection and Preparation

- Data Curation: Collect a set of 20-100 compounds with known biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀, Kᵢ) against the target, ensuring structural diversity and a wide potency range (≥4 orders of magnitude) [33].

- Activity Data: Convert activity values to pIC₅₀ (−logIC₅₀) for QSAR analysis and categorize compounds as active (pIC₅₀ > 5.5) and inactive (pIC₅₀ < 4.7) for hypothesis generation [33].

- Ligand Preparation:

Common Pharmacophore Identification

- Feature Mapping: Identify pharmacophore features present in each active ligand using software such as Schrödinger Phase [33] [31].

- Hypothesis Generation: Generate common pharmacophore hypotheses that align features across multiple active compounds.

- Hypothesis Scoring: Evaluate hypotheses using survival scores that consider alignment accuracy, volume overlap, and selectivity [33].

- Model Selection: Choose the best hypothesis based on statistical parameters (R², Q², F-value) and ability to discriminate active from inactive compounds [33].

3D-QSAR Model Development

- Training/Test Set Division: Split the dataset using random selection or structured methods (e.g., Kennard-Stone), typically using 70-80% for training and 20-30% for testing [33] [34].

- PLS Factor Determination: Use partial least squares (PLS) analysis to establish the relationship between pharmacophore alignment and biological activity [33].

- Model Validation: Validate using leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation (Q²) and external test set prediction (R²test) [33] [34].

- Contour Map Analysis: Generate 3D contour maps to visualize regions where specific chemical features enhance or diminish activity [33].

Table 2: Statistical Parameters for Validating Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Models

| Parameter | Symbol | Acceptable Value | Excellent Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficient | R² | >0.6 | >0.8 | Goodness of fit for training set |

| Cross-Validation Coefficient | Q² | >0.5 | >0.7 | Model predictive ability |

| F-Statistic | F | p<0.05 | p<0.01 | Statistical significance |

| Root Mean Square Error | RMSE | Low relative to data range | As low as possible | Average prediction error |

| Concordance Correlation Coefficient | CCC | >0.8 | >0.9 | Agreement between observed and predicted |

Model Application and Validation

- Database Screening: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a query to screen compound databases (e.g., ZINC, Enamine, in-house collections).

- Hit Selection: Select compounds that match the pharmacophore features and have high predicted activity.

- Experimental Verification: Test selected hits in biological assays to validate model predictions.

Figure 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Advanced Fragment-Based Protocol

Fragment-based pharmacophore screening represents an advanced approach that aggregates pharmacophore feature information from multiple experimentally determined fragment poses. The FragmentScout workflow, developed for SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase, combines features from X-ray crystallographic fragment screening to create comprehensive pharmacophore queries that can identify micromolar hits from millimolar fragments [30].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Fragment Data Collection

- Source Identification: Access fragment screening data from XChem facilities or similar high-throughput crystallographic screening platforms [30].

- Structure Selection: Collect multiple protein-fragment complex structures (typically 20-50) representing different binding modes and chemotypes [30].

Joint Pharmacophore Query Generation

- Feature Detection: Import each fragment-protein structure into LigandScout to automatically assign pharmacophore features and exclusion volumes [30].

- Structure Alignment: Align all structures based on protein coordinates to ensure consistent reference frames.

- Feature Merging: Combine pharmacophore features from all fragments into a single joint query using the "merge based on reference points" function in LigandScout [30].

- Tolerance Optimization: Adjust distance tolerances to accommodate the diverse fragment poses while maintaining specificity.

Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

- Database Screening: Screen large compound databases (e.g., Enamine REAL, ZINC) using the joint pharmacophore query with LigandScout XT [30].

- Hit Prioritization: Select compounds that match key pharmacophore features present in multiple fragment clusters.

- Experimental Validation: Test selected compounds using biophysical (e.g., ThermoFluor) and cellular assays to confirm activity [30].

Virtual Screening Implementation and Validation

Screening Database Preparation

- Database Selection: Choose appropriate screening libraries such as ZINC, Enamine REAL, PubChem, or corporate collections [29] [31].

- Compound Preparation: Generate 3D conformers, assign correct protonation states at physiological pH, and eliminate undesirable compounds (reactive, pan-assay interference compounds).

- Database Formatting: Convert databases to screenable formats compatible with the pharmacophore software (e.g., LigandScout .ldb2 format) [30].

Screening Parameters and Hit Selection

- Search Parameters: Use appropriate feature matching tolerances (typically 1.5-2.0 Å) and set minimum feature match requirements (usually 60-80% of features) [30].

- Screening Method: Employ efficient screening algorithms like the Greedy 3-Point Search in LigandScout XT for large libraries [30].

- Hit Criteria: Select compounds that match essential pharmacophore features while maintaining drug-like properties.

Performance Metrics and Model Validation

- Enrichment Calculations: Use traditional Enrichment Factor (EF) or the improved Bayes Enrichment Factor (EFB) to quantify screening performance [35].

- Early Recognition Metrics: Calculate BEDROC with appropriate α values (α=80.5 gives 80% weight to the top 2% of ranked compounds) [32].

- ROC-AUC Analysis: Generate receiver operating characteristic curves and calculate area under the curve values [33].

- Statistical Significance: Perform y-randomization tests to ensure model robustness [33].

Table 3: Benchmark Virtual Screening Datasets for Validation

| Dataset | Type | Targets | Compounds | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys-Enhanced) | Structure-based | 102 targets | 22,886 actives, 1.4M decoys | 50 property-matched decoys per active; avoids analogue bias | Docking and pharmacophore validation [32] |

| MUV (Maximum Unbiased Validation) | Ligand-based | 17 targets | 30 actives, 15,000 inactives per set | Refined nearest neighbor analysis to avoid artificial enrichment | Ligand-based method validation [29] |

| PDBbind | Structure-based | General: 21,382 complexes; Refined: 4,852 complexes | Binding affinity data (Kd, Ki, IC50) | High-quality protein-ligand complexes with binding data | Scoring function validation [29] |

| BindingDB | Bioactivity | 8,499 targets | 2.2M bioactivity data points | Diverse bioactivity data from literature and patents | Training and validation [29] |

| ChEMBL | Bioactivity | 14,347 targets | 17M activities from 80K publications | Manually curated bioactivity data from literature | Large-scale model training [29] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Software Solutions

Table 4: Key Software Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

| Software Tool | Vendor/Provider | Key Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Inte:ligand | Structure- & ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening | Includes advanced XT screening for large libraries; FragmentScout workflow implementation [30] |

| Phase | Schrödinger | Pharmacophore modeling, 3D-QSAR, virtual screening | Integrates with Maestro platform; best-in-class OPLS4 force field [33] [31] |

| Glide | Schrödinger | Molecular docking, virtual screening | Used for comparative screening in FragmentScout workflow [30] |

| AlphaFold2 | DeepMind/NVIDIA NIM | Protein structure prediction | Provides reliable protein structures when experimental structures unavailable [2] [28] |

| DiffDock | NVIDIA NIM | Molecular docking | AI-based docking approach in high-throughput pipelines [28] |

| MolMIM | NVIDIA NIM | Generative molecular design | Optimizes lead compounds with 90% accuracy in AI-driven pipelines [28] |

Table 5: Essential Data Resources for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Resource | Content Type | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Protein structures | >175,000 macromolecular structures; primary source for structure-based design [2] [29] | https://www.rcsb.org |

| PubChem | Bioactivity data | >280M bioactivity data points; >1.2M biological assays [29] | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| ChEMBL | Bioactivity data | 17M activities from 80K publications; manually curated [29] | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl |

| BindingDB | Binding affinity data | 2.2M binding data points for 8,499 targets; includes assay conditions [29] | https://www.bindingdb.org |

| ZINC | Purchasable compounds | >230M commercially available compounds for virtual screening [32] | https://zinc.docking.org |

| Enamine REAL | Screening compounds | Billion-scale chemical space for virtual screening [30] | https://enamine.net |

This workflow blueprint provides comprehensive protocols for transforming protein structures or ligand sets into effective screenable pharmacophore queries. By following these detailed methodologies, researchers can establish robust virtual screening pipelines that significantly accelerate hit identification in drug discovery campaigns. The integration of structure-based, ligand-based, and fragment-based approaches offers complementary strategies for addressing diverse target classes and data availability scenarios. Proper validation using standardized benchmarks and performance metrics ensures the generation of reliable pharmacophore models capable of identifying novel bioactive compounds with high efficiency.

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling is a foundational computational technique in modern drug discovery that translates the three-dimensional structural information of a macromolecular target into an abstract representation of the chemical features essential for biological activity. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore model is defined as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [36]. This approach has gained significant traction in pharmaceutical research due to its ability to facilitate drug discovery for targets with few known ligands, as it relies primarily on the 3D structure of the target protein rather than extensive structure-activity relationship data [37].

The fundamental principle underlying structure-based pharmacophore generation is the identification and spatial mapping of key interaction points within a protein's binding site that are critical for ligand binding. These interaction points are translated into pharmacophoric features including hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrophobic regions (H), positively or negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), and aromatic features [2] [38]. The resulting pharmacophore model serves as a template for virtual screening of compound databases, enabling researchers to identify novel chemical entities that match the essential interaction pattern required for binding to the target protein [36].

Recent advances in structural biology and computational methods have significantly expanded the applicability of structure-based pharmacophore approaches. With the increasing number of high-resolution protein structures available in public databases such as the Protein Data Bank (PDB), coupled with reliable homology modeling techniques and revolutionary structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2, structure-based pharmacophore modeling has become accessible for a wide range of therapeutic targets [2] [37]. This protocol article provides a comprehensive overview of current techniques, detailed methodologies, and practical applications of structure-based pharmacophore generation within high-throughput virtual screening pipelines.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Fundamental Pharmacophore Features

Structure-based pharmacophore models represent critical ligand-receptor interactions through distinct chemical features with specific spatial arrangements. The primary features include:

- Hydrogen Bond Donors and Acceptors: These features represent the capacity of a ligand to form hydrogen bonds with complementary residues in the protein binding site. In visualization, rigid hydrogen-bond interactions at sp2 hybridized heavy atoms are typically shown as a cone with a cutoff apex, while flexible interactions at sp3 hybridized heavy atoms are represented as a torus [38].

- Hydrophobic Features: These represent regions of the ligand that participate in van der Waals interactions with hydrophobic residues in the binding pocket. Hydrophobic features are crucial for the binding of many drug-like molecules and are often represented as spheres in pharmacophore models [38].

- Ionizable Groups: Positively or negatively charged features that form electrostatic interactions with oppositely charged residues in the protein active site. These are critical for targets where salt bridges contribute significantly to binding affinity.

- Aromatic Features: These include pi-pi stacking and cation-pi interactions with aromatic residues in the binding site. These features are particularly important for targets with tryptophan, tyrosine, or phenylalanine residues in their active sites [38].

- Exclusion Volumes: Steric constraints derived from the protein structure that represent regions inaccessible to ligands due to steric hindrance. These volumes ensure that identified ligands fit comfortably within the binding cavity without clashing with the protein structure [38].

Comparison of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Aspect | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Source | 3D structure of protein target (with or without bound ligand) | Set of known active compounds |

| Key Requirements | Protein structure from X-ray, NMR, or homology modeling | Structural diversity of known actives and their biological activities |

| Feature Identification | Derived from protein-ligand interaction analysis or binding site probing | Extracted from common chemical features of aligned active compounds |

| Advantages | Applicable without known ligands; provides structural insights into binding | Incorporates ligand flexibility directly; reflects actual bioactive conformations |

| Limitations | Dependent on quality and resolution of protein structure | Requires sufficient number of diverse active compounds; may miss novel scaffolds |

| Best Suited For | Novel targets with few known ligands; structure-driven drug design | Targets with extensive SAR data; scaffold hopping and lead optimization |

Computational Tools and Research Reagents

Essential Software and Platforms

The implementation of structure-based pharmacophore generation requires specialized software tools for protein preparation, binding site analysis, feature identification, and model validation. The following table summarizes key computational resources used in structure-based pharmacophore modeling:

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool Category | Representative Software | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Suites | LigandScout [14], Discovery Studio | Structure-based pharmacophore generation | Feature annotation from protein-ligand complexes; exclusion volume mapping |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina [39], GOLD, Glide | Binding pose prediction for complex generation | Provides ligand binding conformations for pharmacophore feature extraction |

| Virtual Screening Platforms | ZINC PHARMER [36], Unity | Pharmacophore-based database screening | Rapid 3D search of compound libraries using pharmacophore queries |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS [38], AMBER, CHARMM | Binding site flexibility assessment | Incorporates protein flexibility and dynamics into pharmacophore models |

| Homology Modeling | MODELLER, SWISS-MODEL, AlphaFold2 [2] | Protein structure prediction | Generates 3D models for targets without experimental structures |

| Graphical Visualization | PyMOL, UCSF Chimera | Model visualization and analysis | Interactive inspection and refinement of pharmacophore features |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch [40] [21] | AI-powered feature detection | Implements neural networks for complex pharmacophore pattern recognition |

Emerging Deep Learning Approaches

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have introduced deep learning methodologies to enhance pharmacophore modeling. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have shown particular promise in analyzing molecular structures and predicting bioactive conformations [21]. These networks process molecular graphs where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges, enabling the model to learn complex structure-activity relationships directly from molecular topology.

VirtuDockDL represents a cutting-edge implementation of this approach, employing a GNN architecture that combines graph-derived features with traditional molecular descriptors and fingerprints [21]. This hybrid approach has demonstrated superior performance in benchmarking studies, achieving 99% accuracy on the HER2 dataset compared to 89% for DeepChem and 82% for AutoDock Vina [21]. The integration of deep learning with pharmacophore modeling enables more accurate prediction of biological activity and enhances the efficiency of virtual screening pipelines.

Experimental Protocols

Core Workflow for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for structure-based pharmacophore generation and application in virtual screening:

Diagram 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Workflow

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation from Experimental Structures

This protocol details the generation of pharmacophore models from experimentally determined protein structures, suitable for targets with available crystal or NMR structures.

Protein Structure Preparation

- Source and Retrieve Structure: Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Prioritize structures with high resolution (<2.5 Å), complete active site residues, and preferably co-crystallized with a ligand [14].

- Structure Preprocessing: Remove crystallographic water molecules, except those involved in crucial water-mediated ligand interactions. Add hydrogen atoms appropriate for physiological pH (typically pH 7.4) using molecular modeling software [2].

- Binding Site Identification: Define the binding site coordinates based on the position of co-crystallized ligands or through computational binding site detection tools such as GRID or LUDI [2]. GRID uses molecular interaction fields to identify energetically favorable interaction sites, while LUDI applies geometric rules derived from known protein-ligand complexes [2].

Pharmacophoric Feature Mapping

- Interaction Analysis: Systematically analyze potential interaction points between the protein binding site and hypothetical ligands. For structures with co-crystallized ligands, examine the specific ligand-protein interactions including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and ionic interactions [14].

- Feature Annotation: Translate identified interaction points into pharmacophoric features:

- Hydrogen Bond Donors/Acceptors: Map complementary HBD and HBA features based on protein residues capable of forming hydrogen bonds [38].

- Hydrophobic Features: Identify hydrophobic subpockets in the binding site and add corresponding hydrophobic features [38].

- Charged Features: Map ionizable features based on the presence of acidic (Asp, Glu) or basic (Arg, Lys, His) residues in the binding site [39].

- Exclusion Volumes: Add exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints derived from the protein structure, ensuring identified ligands fit comfortably within the binding cavity [38].

Model Generation and Optimization

- Feature Selection: From the initially identified features, select those most critical for binding affinity and specificity. Prioritize features that interact with conserved residues known to be essential for biological function from mutagenesis studies [2].

- Spatial Arrangement: Define the spatial relationships between selected features with appropriate distance and angle tolerances. These tolerances should balance model specificity with the ability to identify diverse chemical scaffolds [36].

- Model Validation: Validate the initial pharmacophore model using a set of known active compounds and decoy molecules. Calculate enrichment factors and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to quantify model performance [14] [37].

Protocol 2: Automated Random Pharmacophore Model Generation

For targets with limited ligand information, automated random pharmacophore generation provides an alternative approach that systematically samples possible feature combinations:

Fragment-Based Feature Sampling

- MCSS Implementation: Perform Multiple Copy Simultaneous Search (MCSS) by placing multiple copies of functional group fragments (e.g., hydroxyl, carbonyl, methyl groups) into the protein binding site [37].

- Energy Minimization: Apply energy minimization to optimize fragment positions within the binding site, identifying energetically favorable locations for each fragment type [37].

- Random Feature Selection: Automatically generate pharmacophore models by randomly selecting 5-7 optimized fragments from the MCSS results to create diverse pharmacophore hypotheses [37].

Model Evaluation and Selection