Beyond R²: A Comprehensive Guide to Statistical Validation for Robust Anticancer QSAR Models

This article provides a comprehensive framework for developing and validating statistically robust Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models in anticancer research.

Beyond R²: A Comprehensive Guide to Statistical Validation for Robust Anticancer QSAR Models

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for developing and validating statistically robust Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models in anticancer research. It covers foundational principles, from the OECD guidelines to the critical distinction between internal and external validation, addressing the known limitations of traditional metrics like R² and Q². We explore advanced methodological approaches, including novel parameters like rm² and Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC), and detail strategies for troubleshooting common issues such as overfitting and applicability domain definition. A comparative analysis of established validation criteria from Golbraikh-Tropsha, Roy, and others is presented to guide model selection. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide aims to equip readers with the knowledge to build predictive and reliable QSAR models that can confidently inform the discovery of novel anticancer agents.

The Pillars of Predictive Power: Why QSAR Validation is Non-Negotiable in Anticancer Discovery

The Critical Role of QSAR in Modern Anticancer Drug Discovery

In the face of cancer's complex global health challenge, the drug discovery process remains notoriously time-consuming and costly, with an estimated success rate for new cancer drugs sitting well below 10% [1]. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling has emerged as a cornerstone of computer-aided drug design (CADD), providing a powerful computational methodology to correlate the chemical structures of compounds with their biological activities against cancer targets [2] [1]. By employing mathematical models and machine learning algorithms, QSAR enables researchers to predict the anticancer potential of novel chemical entities before synthesis, significantly accelerating the identification and optimization of lead compounds while reducing reliance on extensive laboratory testing and animal experiments [3]. This review examines the critical application of QSAR methodologies in modern anticancer drug discovery, comparing modeling approaches through experimental case studies and emphasizing the statistical validation frameworks essential for developing robust, predictive models in oncology research.

Foundational QSAR Methodologies and Workflows

Core Principles and Historical Development

QSAR formally began in the early 1960s with the seminal works of Hansch and Fujita, and Free and Wilson, who established the fundamental principle that biological activity can be correlated with physicochemical parameters through mathematical relationships [2]. The approach is rooted in the concept that a molecule's biological activity = f(physicochemical parameters), where these parameters quantitatively describe structural and electronic features [3]. The critical concept of the pharmacophore—the essential geometric arrangement of atoms or functional groups necessary for biological activity—serves as the foundation for understanding ligand-target interactions [2]. QSAR methodologies have evolved through multiple dimensions:

- 1D-QSAR: Correlates global molecular properties like pKa and logP with biological activity [3].

- 2D-QSAR: Considers structural patterns and topological descriptors in two-dimensional space [3] [4].

- 3D-QSAR: Incorporates three-dimensional steric and electrostatic properties [5] [6].

- 4D-QSAR: Extends further to include multiple ligand conformations [3].

Standardized QSAR Modeling Workflow

The generation of robust QSAR models follows a systematic workflow encompassing several critical stages, each requiring rigorous execution to ensure predictive reliability [2] [3].

Table 1: Essential Stages in QSAR Model Development

| Stage | Key Components | Research Reagents & Computational Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset Curation | Compound selection, activity data (IC₅₀, EC₅₀), structural diversity | Commercial databases (PubChem, ChEMBL), in-house compound libraries |

| Descriptor Calculation | Topological, electronic, steric, hydrophobic parameters | Dragon software, PaDEL-Descriptor, RDKit |

| Model Training | Machine learning algorithms, statistical correlation | Random Forest, ANN, PLS, MLR algorithms (Python scikit-learn, R) |

| Validation | Internal & external validation, statistical metrics | Cross-validation, test set prediction, R², Q², RMSE metrics |

| Application | Activity prediction, compound prioritization | Virtual screening platforms, in silico compound design |

The process begins with assembling a library of chemically related compounds with reliably assayed biological activities [2] [3]. Molecular descriptors are then calculated, representing structural and physicochemical properties in numerical form. Using statistical methods or machine learning algorithms, these descriptors are correlated with biological activity to generate predictive models [2]. The resulting model must undergo rigorous validation to confirm its reliability and predictive power before application in virtual screening or lead optimization [2] [3].

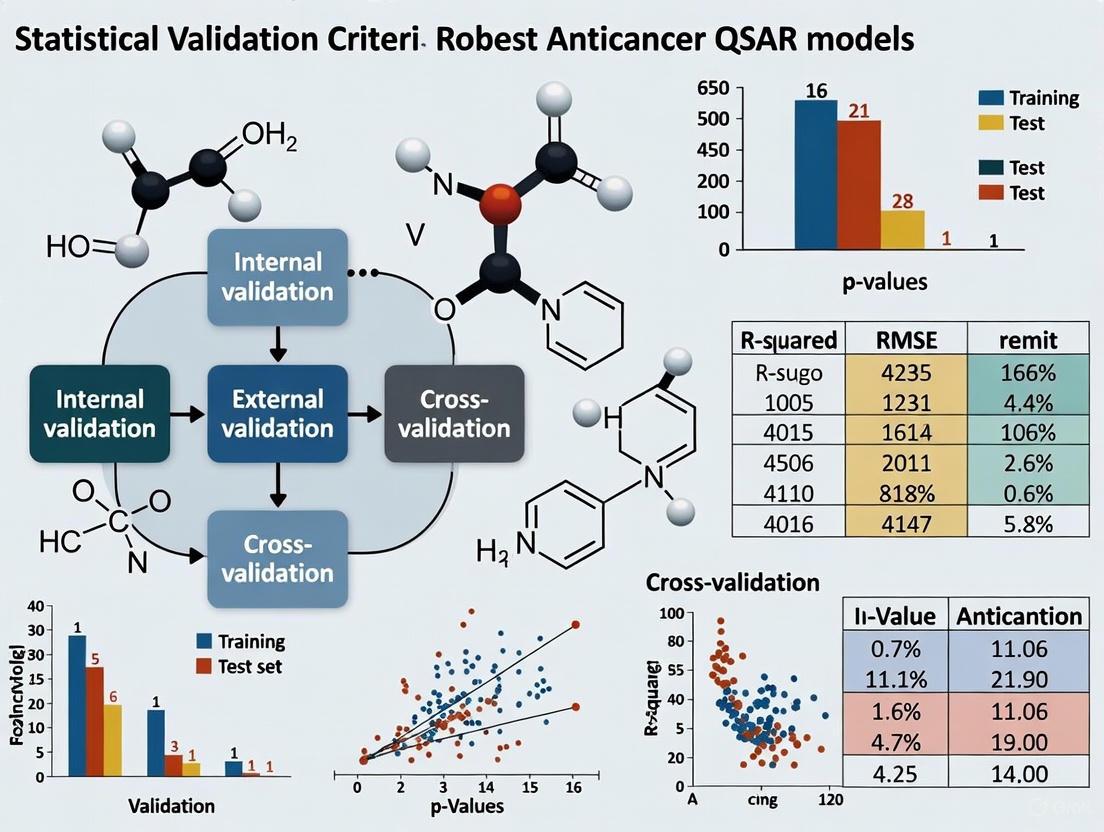

Figure 1: QSAR Model Development Workflow. This standardized protocol ensures robust, predictive model generation for anticancer compound discovery.

Comparative Analysis of QSAR Approaches in Anticancer Research

Machine Learning-Enhanced QSAR for Flavone Optimization

Recent advances have integrated machine learning algorithms with traditional QSAR approaches to enhance predictive performance in anticancer compound optimization. A notable study developed ML-driven QSAR models to optimize flavone derivatives, recognized as "privileged scaffolds" with significant anticancer potential [7]. Researchers designed and synthesized 89 flavone analogs with varied substitution patterns, then evaluated their cytotoxicity against breast cancer (MCF-7) and liver cancer (HepG2) cell lines [7]. The study compared multiple machine learning algorithms, with the Random Forest model demonstrating superior performance for both cancer cell lines [7].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of ML-QSAR Models for Anticancer Flavone Derivatives

| Model Type | MCF-7 R² | MCF-7 Q² | HepG2 R² | HepG2 Q² | Test Set RMSE | Key Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.820 | 0.744 | 0.835 | 0.770 | 0.573 (MCF-7), 0.563 (HepG2) | Electronic parameters, hydrophobicity |

| XGBoost | 0.801 | 0.725 | 0.819 | 0.752 | 0.592 (MCF-7), 0.581 (HepG2) | Steric bulk, hydrogen bonding |

| ANN | 0.785 | 0.710 | 0.808 | 0.741 | 0.605 (MCF-7), 0.594 (HepG2) | Topological indices, substituent effects |

The optimized random forest model successfully identified key molecular descriptors influencing anticancer activity, enabling the rational design of flavone derivatives with enhanced cytotoxicity against cancer cells and low toxicity toward normal Vero cells [7]. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis provided interpretability to the model predictions, highlighting specific structural features responsible for anticancer activity [7].

Experimental Protocol Insight: The biological evaluation followed standardized MTT assay procedures. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with varying concentrations of flavone derivatives for 48 hours. After incubation, MTT solution was added, and formazan crystals were dissolved before measuring absorbance at 570nm. IC₅₀ values were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis [7].

3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking for Multi-Target Cancer Therapy

The emergence of resistance to single-target therapies has driven the development of multi-targeting agents in oncology. A comprehensive study explored 2-Phenylindole derivatives as MCF-7 breast cancer cell line inhibitors using 3D-QSAR modeling combined with molecular docking [6]. The Comparative Molecular Similarity Index Analysis (CoMSIA) with SEHDA methodology produced a highly reliable model with R² = 0.967 and a strong Leave-One-Out cross-validation coefficient (Q² = 0.814) [6]. The model maintained strong predictive capability in external testing (R²Pred = 0.722), demonstrating statistical robustness [6].

Six new compounds designed using this approach showed potent predicted inhibitory activity and favorable ADMET profiles [6]. Molecular docking studies revealed that these novel compounds exhibited superior binding affinities (-7.2 to -9.8 kcal/mol) to key cancer-related targets (CDK2, EGFR, and Tubulin) compared to reference drugs [6]. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed the stability of the best-docked complexes over 100ns, providing additional validation of the multi-targeting approach [6].

Experimental Protocol Insight: The 3D-QSAR study employed the following methodology: molecular structures were sketched in ChemDraw and converted to 3D using Chem3D, then minimized using the MMFF94 force field. Molecular alignment was performed using the common skeleton-based method. The CoMSIA fields were calculated with a grid spacing of 2.0 Å, and partial least squares (PLS) analysis was used to construct the relationship between structural descriptors and biological activity [6].

Integrated QSAR-Docking-ADMET Workflow for Natural Product Derivatives

Natural products represent valuable scaffolds for anticancer drug discovery, but systematic optimization requires sophisticated computational approaches. Researchers implemented an integrated in silico framework to evaluate 24 acylshikonin derivatives, combining QSAR modeling with molecular docking and ADMET prediction [8]. The Principal Component Regression (PCR) model demonstrated exceptional predictive performance (R² = 0.912, RMSE = 0.119), identifying electronic and hydrophobic descriptors as critical determinants of cytotoxic activity [8].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of QSAR Methodologies for Different Cancer Targets

| QSAR Methodology | Cancer Type | Molecular Target | Statistical Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Random Forest [7] | Breast, Liver | Multiple | R² = 0.820-0.835, Q² = 0.744-0.770 | Handles complex descriptor relationships |

| 3D-QSAR CoMSIA [6] | Breast | CDK2, EGFR, Tubulin | R² = 0.967, Q² = 0.814 | Captures steric and electrostatic fields |

| PCR Modeling [8] | Multiple | 4ZAU protein | R² = 0.912, RMSE = 0.119 | Reduces descriptor collinearity |

| ANN-QSAR [5] | Breast | Aromatase | R² = 0.89, Q² = 0.85 | Models nonlinear structure-activity relationships |

Docking simulations identified compound D1 as the most promising derivative, forming multiple stabilizing hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with key residues of the cancer-associated target 4ZAU [8]. All evaluated derivatives satisfied major drug-likeness filters and exhibited acceptable synthetic accessibility, indicating favorable pharmacokinetic potential for further development [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The successful implementation of QSAR in anticancer drug discovery relies on specialized research reagents and computational solutions that form the foundation of robust modeling workflows.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Anticancer QSAR Studies

| Research Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Synthetic flavone library [7], Acylshikonin derivatives [8] | Provide structural diversity and experimental activity data for model training |

| Descriptor Calculation Software | Dragon, PaDEL-Descriptor, RDKit | Generate quantitative molecular descriptors from chemical structures |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Python scikit-learn, R, Weka | Implement statistical algorithms for model development |

| Validation Toolkits | QSAR Model Reporting Format, OECD Validation Principles | Ensure model predictability and regulatory compliance |

| Structural Biology Resources | Protein Data Bank (PDB), Homology Modeling Tools | Provide target structures for integrated QSAR-docking studies |

Statistical Validation Frameworks for Robust Anticancer QSAR

The critical importance of statistical validation in QSAR modeling cannot be overstated, particularly in the high-stakes context of anticancer drug discovery. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) principles, a valid QSAR model must have: (1) a defined endpoint, (2) an unambiguous algorithm, (3) a defined domain of applicability, (4) appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity, and (5) a mechanistic interpretation, if possible [3].

The "domain of applicability" defines the chemical space where the model can reliably make predictions, preventing extrapolation beyond validated structural boundaries [2]. Model validation typically involves both internal techniques (cross-validation, bootstrap) and external validation using a completely independent test set not used in model building [5] [7]. Key statistical metrics include R² (goodness-of-fit), Q² (predictive ability from cross-validation), and RMSE (error measure) [7] [8].

Figure 2: QSAR Model Validation Framework. This diagram outlines the essential statistical validation criteria based on OECD principles for developing robust anticancer QSAR models.

QSAR methodologies have evolved from traditional linear regression to sophisticated machine learning and multi-dimensional approaches that integrate seamlessly with molecular docking, ADMET prediction, and molecular dynamics simulations [5] [8] [6]. The critical advantage of these computational approaches lies in their ability to prioritize the most promising candidates for synthesis and biological evaluation, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with anticancer drug discovery [3] [1]. As artificial intelligence continues to transform computational biology, QSAR modeling remains a cornerstone of rational drug design, providing researchers with powerful predictive tools to navigate complex structure-activity relationships in oncology. Future directions will likely focus on enhancing model interpretability, expanding applicability domains to cover broader chemical spaces, and strengthening integration with experimental validation to accelerate the development of novel anticancer therapeutics.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a critical computational approach in modern chemical risk assessment and drug discovery. These mathematical models predict the biological activity or physicochemical properties of chemical compounds based on their structural characteristics, providing a powerful tool for prioritizing chemicals for further testing and filling data gaps when experimental testing is impractical or unethical. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has spearheaded an international effort to establish a solid scientific foundation for QSAR applications, particularly in regulatory contexts [9]. This initiative gained significant momentum with the implementation of the European Union's REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals) regulation, which explicitly promotes the use of QSAR approaches to reduce vertebrate animal testing while ensuring the protection of human health and the environment [10].

The OECD principles for QSAR validation were formally established in 2004 following extensive international discussions and have since become the global benchmark for assessing the scientific validity of QSAR models intended for regulatory applications [10]. These principles provide a framework that manufacturers, regulators, and researchers can apply to ensure that QSAR predictions are scientifically credible and adequately reliable for decision-making processes. This guide examines these fundamental principles, their practical implementation in model development and validation, and their critical role in advancing robust QSAR applications, particularly in the demanding field of anticancer drug research.

The Five OECD Principles for QSAR Validation

The OECD member countries have agreed upon five validation principles that a (Q)SAR model should fulfill to be considered for regulatory application [10]. These principles provide a systematic framework for developing scientifically rigorous models.

Table 1: The OECD Principles for QSAR Validation

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Core Requirement | Common Pitfalls Avoided |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Defined Endpoint | A transparent and unambiguous definition of the biological activity or property being predicted. | Prevents models constructed using data measured under different conditions and various experimental protocols. |

| 2 | Unambiguous Algorithm | A clear description of the algorithm used to generate the model. | Addresses lack of transparency when commercial models do not provide algorithmic information. |

| 3 | Defined Applicability Domain | A clear description of the chemical structures and properties for which the model can make reliable predictions. | Ensures models are not applied to chemicals outside the structural domain used in model development. |

| 4 | Appropriate Validation Statistics | Demonstration of the model's predictive power using internationally accepted statistical measures. | Provides objective evidence of model performance using both internal and external validation techniques. |

| 5 | Mechanistic Interpretation | Provision of a mechanistic interpretation where possible, though not always mandatory. | Encourages scientifically plausible models that reflect understanding of biological effect mechanisms. |

Principle 1: A Defined Endpoint

The first principle requires that the endpoint being predicted must be transparently and unambiguously defined. This includes a clear description of the biological effect, the experimental system used to generate the training data, and the specific units of measurement. Without a precisely defined endpoint, significant inconsistencies can arise because models may be constructed using data measured under different conditions and varying experimental protocols [10]. In anticancer research, this might involve specifying whether a model predicts cytotoxicity against a particular cell line (e.g., MCF-7 breast cancer cells) or inhibitory activity against a specific molecular target (e.g., EGFR tyrosine kinase), along with exact experimental conditions.

Principle 2: An Unambiguous Algorithm

The second principle mandates that the algorithm used to construct the model must be clearly defined. This includes the complete mathematical representation of the model, the types of molecular descriptors employed, and any data pre-processing steps. The requirement addresses the commercial practice where some organizations selling models do not provide algorithmic information, claiming proprietary concerns [10]. For regulatory acceptance, however, the model must be sufficiently transparent to allow independent assessment of its scientific basis.

Principle 3: A Defined Applicability Domain

The applicability domain (AD) represents the chemical space defined by the structures and properties of the compounds used to develop the model. A clearly defined AD indicates for which compounds the model can generate reliable predictions and is perhaps the most crucial principle for preventing model misuse [10]. In practice, each QSAR model is intrinsically linked to the chemical structures, physicochemical properties, and biological mechanisms represented in its training set. When a compound falls outside the model's applicability domain, its predictions should be treated with appropriate caution, as the model's performance for such compounds is unverified [11].

Principle 4: Appropriate Measures of Goodness-of-Fit, Robustness, and Predictivity

The fourth principle requires suitable statistical evaluation to demonstrate the model's reliability. Both internal validation (e.g., cross-validation) and external validation (using an independent test set) should be employed whenever possible [10]. Common statistical measures include:

- Goodness-of-fit: R² (coefficient of determination)

- Internal predictivity: Q² (cross-validated correlation coefficient)

- External predictivity: PRESS (Predictive Residual Sum of Squares) and SDEP (Standard Deviation of Prediction)

A model is generally considered "good" if Q² > 0.5 and "excellent" if Q² > 0.9 [10]. For classification models, metrics such as balanced accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) are increasingly important, particularly for virtual screening applications where identifying active compounds is the primary goal [12].

Principle 5: A Mechanistic Interpretation, If Possible

The final principle encourages, where possible, a mechanistic interpretation of the model. This means that the molecular descriptors used in the model should be interpretable in the context of the biological endpoint being predicted [10]. While recognizing that the exact mechanism may not always be known, this principle pushes model developers to consider how structural features relate to biological activity through plausible biological pathways. In anticancer QSAR studies, this might involve linking specific molecular features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, hydrophobic regions) to known interactions with cancer-related biological targets.

Figure 1: The sequential workflow for implementing OECD QSAR validation principles, from initial model development through regulatory acceptance.

Experimental Protocols for QSAR Model Validation

Standardized Model Development Workflow

Developing a QSAR model that complies with OECD principles requires a systematic approach to dataset preparation, descriptor calculation, model building, and validation. The following workflow outlines the key experimental and computational steps:

Dataset Curation: Compile a structurally diverse set of compounds with reliable, consistent experimental data for the defined endpoint. This data should ideally come from standardized assays conducted under comparable conditions [2].

Chemical Structure Standardization: Process all chemical structures to ensure consistent representation, including removal of duplicates, standardization of tautomeric forms, and optimization of 3D geometries if required.

Descriptor Calculation: Generate molecular descriptors capturing relevant structural and physicochemical properties using computational chemistry software. These may include electronic, steric, hydrophobic, and topological descriptors [2].

Data Splitting: Divide the dataset into training (typically 70-80%) and test (20-30%) sets using rational methods (e.g., Kennard-Stone, sphere exclusion) to ensure both sets adequately represent the chemical space.

Model Building: Apply machine learning or regression algorithms (e.g., PLS, Random Forest, SVM) to establish relationships between descriptors and the endpoint activity using the training set [13].

Internal Validation: Assess model performance on the training set using cross-validation techniques (e.g., leave-one-out, k-fold) to evaluate robustness [10].

External Validation: Test the final model on the previously unused test set to evaluate its predictive ability for new compounds [10].

Applicability Domain Characterization: Define the model's applicability domain using approaches such as leverage methods, distance-based methods, or descriptor ranges [11] [10].

Mechanistic Interpretation: Analyze the relative importance of descriptors in the model and relate them to known chemical and biological principles governing the endpoint [10].

Statistical Validation Protocols

Robust statistical validation is fundamental to OECD Principle 4. The following protocols ensure comprehensive assessment of model performance:

For Regression Models (Predicting Continuous Values):

- Calculate goodness-of-fit metrics: R², adjusted R², and root mean square error (RMSE) for the training set

- Perform cross-validation: Calculate Q² and cross-validated RMSE using leave-one-out or k-fold methods

- Conduct external validation: Calculate predictive R² (R²pred), predictive RMSE, and concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) for the test set

- Analyze residuals: Check for systematic errors and heteroscedasticity

For Classification Models (Categorical Predictions):

- Generate confusion matrices for both training and test sets

- Calculate sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and balanced accuracy

- Compute precision (Positive Predictive Value - PPV) and recall

- Generate receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and calculate area under curve (AUC)

- For virtual screening applications, prioritize PPV as it directly measures the proportion of true actives among predicted actives, which is critical when experimental follow-up capacity is limited [12]

Figure 2: Comprehensive QSAR model development workflow showing key stages from data preparation through model application, aligned with OECD validation principles.

Comparative Analysis of QSAR Software and Tools

Various software platforms implement the OECD principles with different approaches and capabilities. The selection of appropriate tools depends on the specific application domain, required level of transparency, and regulatory context.

Table 2: Comparison of QSAR Software Platforms Supporting OECD Validation Principles

| Software Platform | Primary Application Domain | OECD Principle Support | Notable Features | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGA | Environmental risk assessment; Cosmetic ingredient safety [11] | Defined endpoints, Applicability Domain, Validation statistics | Integration of multiple models; Qualitative and quantitative predictions | High performance for ready biodegradability (IRFMN model); Relevant for BCF prediction (Arnot-Gobas model) [11] |

| EPI Suite | Environmental fate prediction [11] | Defined endpoints, Validation statistics | Comprehensive suite for physicochemical property and environmental fate prediction | BIOWIN models show high performance for persistence property; KOWWIN effective for Log Kow prediction [11] |

| Danish QSAR Models | Regulatory chemical assessment [11] | Defined endpoints, Validation statistics | Open-access models focused on specific regulatory endpoints | Leadscope model shows high performance for ready biodegradability prediction [11] |

| ADMETLab 3.0 | Drug discovery and development [11] | Defined endpoints, Validation statistics | Web-based platform for ADMET property prediction | High performance for Log Kow prediction in bioaccumulation assessment [11] |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Regulatory hazard assessment [10] | All five OECD principles | Profiling and categorization of chemicals; Read-across capabilities | Free software designed specifically for regulatory applications; Supports chemical categorization [10] |

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Robust QSAR Modeling

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in QSAR Modeling | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | TOXRIC, PubChem, ChEMBL, DrugBank [13] [12] | Sources of experimental bioactivity and toxicity data for model training | Data quality verification essential; Standardization required for cross-study comparisons |

| Descriptor Calculation Software | DRAGON, PaDEL, CDK | Generation of molecular descriptors from chemical structures | Descriptor selection critical to avoid overfitting; Domain relevance important |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | PLS, Random Forest, SVM, Neural Networks [13] | Establishing mathematical relationships between structures and activities | Algorithm selection depends on dataset size, complexity, and endpoint nature |

| Validation Frameworks | OECD QSAR Assessment Framework [14] | Systematic approach to assess model validity and applicability | Provides structured methodology for evaluating regulatory readiness |

| Applicability Domain Tools | Leverage methods, Distance-based approaches, PCA-based methods [10] | Defining chemical space where model predictions are reliable | Critical for regulatory acceptance; Prevents model extrapolation beyond valid domain |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions in QSAR Validation

Emerging Techniques: q-RASAR Modeling

Recent advances in QSAR methodologies include the development of quantitative Read-Across Structure-Activity Relationship (q-RASAR) models, which combine traditional QSAR with similarity-based read-across techniques. This hybrid approach has demonstrated superior performance compared to conventional QSAR in predicting human acute toxicity, with one study reporting robust external validation metrics (Q²F1 = 0.812, Q²F2 = 0.812) [13]. The q-RASAR approach enhances predictive accuracy by incorporating similarity values among closely related compounds, along with traditional molecular descriptors, potentially offering a more comprehensive framework for addressing complex endpoints.

Evolving Validation Paradigms for Virtual Screening

Traditional QSAR validation practices emphasizing dataset balancing and balanced accuracy are being reconsidered for virtual screening applications, particularly in anticancer drug discovery. Recent research indicates that for virtual screening of ultra-large chemical libraries, models with the highest positive predictive value (PPV) built on imbalanced training sets outperform balanced models in identifying active compounds [12]. This paradigm shift recognizes the practical constraints of experimental follow-up, where typically only small batches of compounds (e.g., 128 compounds fitting a single screening plate) can be tested. Studies show that training on imbalanced datasets achieves a hit rate at least 30% higher than using balanced datasets, highlighting the importance of context-specific validation metrics [12].

Regulatory Implementation and Acceptance

The OECD QSAR Assessment Framework provides a practical tool for increasing regulatory uptake of computational approaches [14]. This framework assists in building confidence in (Q)SAR predictions by systematically addressing uncertainty and applicability domain considerations. As regulatory agencies continue to develop capacity for evaluating computational models, adherence to the OECD principles remains foundational for establishing scientific credibility. The principles provide a common language and evaluation framework that facilitates dialogue between model developers, users, and regulatory decision-makers, ultimately promoting the appropriate use of these valuable tools in protecting human health and the environment.

In the rigorous field of computational drug discovery, particularly in the development of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models for anticancer research, validation is not merely a procedural step—it is the cornerstone of model credibility. For researchers and drug development professionals, the distinction between internal and external validation represents a fundamental concept that separates a suggestive hypothesis from a predictive, reliable tool. These processes are critical for assessing the robustness and generalizability of models designed to predict the activity of novel compounds, such as those targeting melanoma or leukemia cell lines. However, inconsistencies in their application and interpretation persist within the scientific community. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two validation paradigms, framed within the established OECD principles, to equip scientists with the knowledge to build statistically sound QSAR models for robust anticancer research.

Core Conceptual Frameworks: Internal and External Validation Defined

In the context of QSAR modeling, validation is a holistic process for assessing a model's quality, applicability, and mechanistic interpretability [15]. The OECD principles have cemented the scientific and regulatory necessity of this step, identifying the need to validate a model both internally and externally [15].

Internal Validation refers to the process of evaluating a model's performance using the same data on which it was trained. Its primary intent is to assess the model's goodness-of-fit and robustness [15] [16]. Internal validation techniques, such as cross-validation (e.g., Leave-One-Out), involve repeatedly building the model on subsets of the training data and testing it on the remaining portions. This process checks how stable the model's parameters are and helps guard against overfitting.

External Validation, in contrast, is the ultimate test of a model's predictivity and generalizability [17] [15] [16]. It involves testing the model on a completely new set of data—the external test set—that was not used in any part of the model building process. A model that passes external validation demonstrates its potential to make accurate predictions for new, untested chemicals, which is the primary goal in drug discovery [15].

The relationship between these two forms of validation is often a trade-off. Over-optimizing a model for internal performance can sometimes reduce its ability to generalize to external data, a phenomenon known as overfitting [18]. Therefore, a successful QSAR model must strike a balance, demonstrating competence in both areas to be considered reliable for predictive purposes.

Methodological Protocols and Statistical Criteria

The validity of a QSAR model is quantified using specific statistical protocols and metrics for both internal and external validation. The following workflow outlines the general process of QSAR model development and where each validation type occurs:

Internal Validation Protocols

Internal validation begins during the model development phase. A common protocol is Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOO-CV), where a single compound is removed from the training set, the model is rebuilt with the remaining compounds, and the activity of the removed compound is predicted. This is repeated for every compound in the training set [15].

The key statistical parameters for internal validation include:

- Q² (Q²LOO): The cross-validated correlation coefficient. A high Q² (e.g., >0.5) indicates model robustness [19].

- R²: The coefficient of determination for the training set, indicating goodness-of-fit. A value closer to 1.0 suggests a good fit [20] [19].

- R²adjusted: Adjusts R² for the number of descriptors, penalizing model overcomplexity [20].

For example, in a QSAR study on anti-leukemia compounds, the model for the MOLT-4 cell line showed high internal validity with R² = 0.902 and Q²LOO = 0.881 [19].

External Validation Protocols

External validation is performed by applying the final model, built on the entire training set, to the withheld test set. The OECD principles emphasize that a model's predictivity must be established externally [15].

Multiple statistical criteria have been proposed to judge external validity, as relying on the coefficient of determination (r²) alone is insufficient [17] [21]. The following table summarizes the key metrics and their thresholds:

| Validation Metric | Description | Acceptance Threshold | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| R²pred | Coefficient of determination for the test set. | > 0.6 | Golbraikh & Tropsha [21] |

| Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) | Measures the agreement between experimental and predicted values. | > 0.8 | Gramatica [21] |

| r²m | A modified r² metric that accounts for differences between observed and predicted values via regression through origin. | > 0.5 | Roy [21] |

| Slope (K or K') | Slope of the regression line through the origin between experimental and predicted values. | 0.85 < K < 1.15 | Golbraikh & Tropsha [21] |

A study evaluating 44 QSAR models highlighted that these criteria have individual advantages and disadvantages, and using a combination of them provides a more reliable assessment of a model's predictive power [17] [21].

Comparative Analysis: A Side-by-Side Examination

The table below provides a direct, structured comparison of internal and external validation based on core characteristics, using examples from anticancer QSAR research.

| Characteristic | Internal Validation | External Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Objective | Evaluate goodness-of-fit and robustness [15]. | Test predictivity and generalizability [17] [15]. |

| Primary Question | Is the model stable and internally consistent? | Can the model accurately predict new, unseen data? |

| Data Usage | Uses only the training set data [15] [16]. | Uses a separate, unseen test set [17] [16]. |

| Common Metrics | R², Q²LOO, R²adjusted [20] [19]. | R²pred, CCC, r²m, Slope of regression (K) [21]. |

| Typical Workflow | Cross-validation (e.g., Leave-One-Out) [15]. | Splitting data into training/test sets prior to modeling [20] [17]. |

| Example from Research | SK-MEL-2 melanoma model: R²=0.864, Q²cv=0.799 [20]. | SK-MEL-2 model tested on 22 compounds [20]. |

| Role in OECD Principles | Addresses "goodness-of-fit" and "robustness" (Principle 4) [15]. | Addresses "predictivity" (Principle 4) [15]. |

| Main Risk | Overfitting: A model with high R²/Q² may fail on external data [18] [17]. | Under-generalization: A model may be too specific to the training set chemistry. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software for QSAR Validation

Building and validating a robust QSAR model requires a suite of computational tools and conceptual "reagents." The following table details key resources referenced in the studies cited.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in QSAR Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PaDEL-Descriptor [20] [19] | Calculates molecular descriptors from chemical structures, which are the independent variables in the model. | Used to generate descriptors for 72 NCI cytotoxic compounds [20] and 112 anti-leukemia compounds [19]. |

| CORAL Software [22] | A QSAR modeling tool that uses SMILES notation and the Monte Carlo method to build models and calculate optimal descriptors. | Employed to develop a QSAR model for 193 chalcone derivatives against colon cancer (HT-29) [22]. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) [20] [15] | A conceptual "reagent" that defines the chemical space where the model's predictions are reliable. Critical for interpreting both internal and external validation results. | Compounds 30 and 41 were used as templates for new drug design because they had high activity and resided within the model's AD [20]. |

| Test Set (External Set) | The ultimate "reagent" for external validation. A subset of data withheld from model training to provide an unbiased assessment of predictive power. | The SK-MEL-2 study used a test set of 22 compounds to determine the model's predictive ability [20]. |

| OECD Validation Principles [15] | A framework of five principles that provide guidelines for developing scientifically valid and regulatory-accepted QSAR models. | Serves as a checklist to ensure a QSAR model has a defined endpoint, unambiguous algorithm, and is properly validated [15]. |

Navigating Inconsistencies and Reaching a Consensus

A significant inconsistency in QSAR validation lies in the over-reliance on a single metric, particularly for external validation. A 2022 comprehensive study confirmed that using the coefficient of determination (r²) alone is inadequate for confirming a model's validity [17] [21]. Different criteria proposed by various researchers (Golbraikh & Tropsha, Roy, Gramatica) can sometimes yield conflicting conclusions about the same model due to their specific mathematical focuses and potential statistical defects [21].

To navigate these inconsistencies and build consensus, researchers should adopt a multi-faceted strategy:

- Use Multiple Validation Criteria: Do not rely on a single metric. A model should satisfy a majority of the established external validation criteria (e.g., R²pred > 0.6, CCC > 0.8, and 0.85 < K < 1.15) to be deemed predictive [21].

- Define the Applicability Domain (AD): As per OECD Principle 3, every model must have a defined AD [15]. A prediction for a compound outside the AD is unreliable, regardless of the validation metrics. This step is crucial for understanding the scope and limitations of your model's predictions.

- Follow OECD Principles: Adhering to the five OECD principles provides a comprehensive framework that ensures scientific rigor [15]. This includes having a defined endpoint, an unambiguous algorithm, a defined AD, appropriate measures of fit and predictivity, and a mechanistic interpretation where possible.

In the demanding landscape of anticancer drug development, the path from a computational model to a trusted predictive tool is paved with rigorous validation. Internal and external validation are not redundant steps but are complementary and both essential. Internal validation ensures a model is robust and internally consistent, while external validation is the unequivocal test of its predictive power for novel compounds. While inconsistencies in statistical criteria exist, a consensus approach that employs multiple validation metrics, strictly defines the model's applicability domain, and adheres to the OECD principles provides the most robust strategy. For researchers aiming to design the next generation of anticancer agents, mastering this balanced approach to validation is not just a best practice—it is a scientific imperative.

In the high-stakes field of anticancer drug development, robust statistical models are indispensable for predicting compound efficacy and prioritizing candidates for synthesis. While the coefficient of determination, R², is frequently used as an initial measure of model fit, reliance on this single metric presents significant risks. This guide objectively compares the performance of various statistical validation criteria, demonstrating through experimental QSAR (Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship) data why a multi-faceted validation strategy is crucial for developing reliable models.

The Allure and Peril of R²

R-squared is ubiquitously used to indicate the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the model. However, this common intuition is seriously flawed [23]. R² is often mistakenly treated as a scoring system, where a value above 0.9 is considered an 'A', above 0.8 a 'B', and below 0.7 a failure [23]. This perception is problematic because R² can be misleadingly inflated by including more variables in the model, even those with no real informational value, leading to overfit models that fail in prediction [23] [24]. Furthermore, R² is sensitive to outliers and does not convey information about the direction or practical significance of the relationship between variables [24]. In essence, a high R² does not guarantee a good or useful model.

A Multi-Metric Framework for QSAR Model Validation

Robust QSAR model acceptance requires evaluating multiple statistical parameters that assess different aspects of model quality, including its internal stability, predictive power, and chance correlation. The table below summarizes the core metrics beyond R² that form a comprehensive validation framework.

Table 1: Key Statistical Metrics for Robust QSAR Model Validation

| Metric Category | Metric Name | Definition | Interpretation | Desired Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goodness-of-Fit | R² | Coefficient of determination for the training set. | Proportion of variance explained by the model. | > 0.6 |

| R²adj | R-squared adjusted for the number of descriptors. | Prevents model overfitting; penalizes excessive parameters. | Close to R² | |

| Internal Validation | Q²loo (or Q²cv) | Cross-validated R² (e.g., Leave-One-Out). | Measure of the model's internal predictive ability and stability. | > 0.5 |

| External Validation | R²pred | R-squared for the external test set. | True measure of the model's predictive power for new data. | > 0.5 |

| Robustness Check | Y-Scrambling | Correlation from models built with randomized activity. | Ensures model is not a result of chance correlation. | Low correlation |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

The following methodologies are essential for generating the validation metrics cited in this guide.

Protocol 1: Internal Validation via Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation

- Step 1: From the full dataset of n compounds, remove one compound to serve as a temporary validation set.

- Step 2: Build the QSAR model using the remaining n-1 compounds.

- Step 3: Use the newly built model to predict the activity of the omitted compound.

- Step 4: Repeat steps 1-3 until every compound in the dataset has been omitted and predicted once.

- Step 5: Calculate the predictive residual sum of squares (PRESS) from all predictions, and then compute Q²loo as follows: Q²loo = 1 - (PRESS / SS), where SS is the total sum of squares of the original activity values.

Protocol 2: External Validation via a Test Set

- Step 1: Before model building, rationally divide the full dataset into a training set (typically 70-80%) and a test set (20-30%). The test set must never be used in model calibration.

- Step 2: Build the QSAR model exclusively using the training set compounds.

- Step 3: Use the final model to predict the activities of the test set compounds.

- Step 4: Calculate the predictive residual sum of squares (PRESS) for the test set and the total sum of squares (SS) of the experimental activities in the test set. The R²pred is calculated as: R²pred = 1 - (PRESS / SS).

Protocol 3: Y-Scrambling for Detecting Chance Correlation

- Step 1: Randomly shuffle the biological activity values (the Y-response) of the training set compounds, thereby breaking the true structure-activity relationship.

- Step 2: Build a new "model" using the scrambled activities and the original molecular descriptors.

- Step 3: Record the R² and Q² values of this scrambled model.

- Step 4: Repeat this process numerous times (e.g., 100-200 iterations).

- Step 5: Analyze the distribution of R² and Q² from the scrambled models. A robust original model should have significantly higher R² and Q² values than those obtained from the scrambled data.

Case Study: Validation in Action for Anti-Melanoma and Anti-Leukemia Models

Examining published QSAR studies reveals how a multi-metric approach is applied in practice. The following table compares the validation data from two independent anticancer QSAR studies.

Table 2: Comparative Validation Metrics from Published Anticancer QSAR Studies

| Study Focus / Cell Line | Training Set Metrics | External Validation Metric | Key Active Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-Melanoma (SK-MEL-2) [20] | R² = 0.864, R²adj = 0.845, Q²cv = 0.799 | R²pred = 0.706 (on 22 compounds) | Anthra[1,9-cd]pyrazol-6(2H)-one derivative (NSC-355644) |

| Anti-Leukemia (P388) [19] | R² = 0.904, Q²LOO = 0.856 | R²pred = 0.670 | Not Specified |

| Anti-Leukemia (MOLT-4) [19] | R² = 0.902, Q²LOO = 0.881 | R²pred = 0.635 | Not Specified |

The data demonstrates that while the anti-leukemia models showed excellent goodness-of-fit and internal validation (R² and Q² > 0.85), their external predictive power, as indicated by R²pred, was notably lower. This underscores the critical importance of external validation; a model can appear perfect internally but still be less reliable for predicting new compounds. In contrast, the anti-melanoma model presents a more balanced profile across all validation metrics, suggesting greater robustness [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for QSAR Modeling

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Robust QSAR Modeling

| Tool / Reagent | Function in QSAR Modeling |

|---|---|

| paDEL Descriptor Software [20] [19] | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures, providing the numerical inputs for model building. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) Assessment [11] | Defines the chemical space area where the model can make reliable predictions, crucial for evaluating new compounds. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT/B3LYP) [20] | A computational method for optimizing 3D molecular structures to their most stable geometry before descriptor calculation. |

| V600E-BRAF Protein (PDB: 3OG7) [20] | A specific crystal structure of a target protein used in molecular docking studies to validate QSAR predictions and elucidate binding modes. |

Integrated Workflow for Robust Anticancer QSAR Model Development

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of building and validating a QSAR model, highlighting the critical checkpoints beyond R².

Integrated QSAR Validation Workflow

The pursuit of robust, predictive QSAR models in anticancer research demands a rigorous, multi-faceted approach to validation. As demonstrated, an over-reliance on R² can be misleading and carries the risk of adopting models that fail when applied to new chemical entities. The consistent application of internal validation (Q²), external validation (R²pred), and robustness checks (Y-scrambling), complemented by a clear definition of the model's Applicability Domain, provides a far more defensible foundation for leveraging computational predictions in the costly and critical journey of drug discovery.

Building Defensible Models: A Step-by-Step Guide to Advanced Validation Techniques

In the field of anticancer drug discovery, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a powerful computational tool to predict the biological activity of novel compounds, thereby streamlining the research process [25] [26]. The reliability and predictive power of these models are paramount. A robust validation protocol, built on the core components of internal, external, and data randomization validation, is essential to ensure that a QSAR model can deliver trustworthy predictions for new, untested chemicals. This guide objectively compares these validation methods and outlines the experimental data required to confirm a model's robustness for research applications [25].

Core Components of QSAR Model Validation

The following table summarizes the key validation components, their objectives, and the common statistical measures used to assess them.

Table 1: Core Components of a QSAR Validation Protocol

| Validation Component | Primary Objective | Key Validation Experiments & Metrics | Acceptance Criteria Indicating Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation | To ensure the model is statistically significant and reliable for the data used to build it. | - Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOO-CV): Calculates the cross-validated correlation coefficient, ( q^2 ) [25].- Y-Randomization Test: Checks for chance correlation by randomizing the target activity values [25] [27]. | - ( q^2 > 0.5 ) is a common threshold [25].- The ( q^2 ) of the actual model should be significantly higher than that of randomized models. A ( cR^2_p > 0.5 ) confirms the model is not inferred by chance [27]. |

| External Validation | To evaluate the model's predictive power for new, untested data not used in model development. | - Test Set Prediction: The model predicts an external set of compounds. The correlation coefficient ( R^2 ) between predicted and experimental activities is calculated [25]. | - ( R^2 > 0.6 ) for the external test set is a cited benchmark [25].- A high ( R^2_{test} ) value (e.g., 0.98) indicates excellent predictive ability [27]. |

| Data Randomization | To verify that the model's performance is based on a true structure-activity relationship and not a statistical fluke. | - Y-Randomization (Scrambling): The biological activity values (Y-block) are randomly shuffled, and new models are built. This process is repeated multiple times [25] [27]. | - The statistical parameters (e.g., ( q^2 ), ( R^2 )) of the true model should be drastically superior to those obtained from the randomized models [25]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

Internal Validation via Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation

Methodology: This procedure tests the model's stability and predictive reliability within the training set.

- Training Set: Begin with a defined training set of compounds with known structures and activities (e.g., IC₅₀ or EC₅₀) [25].

- Iterative Omission: One compound is removed from the training set.

- Model Rebuilding: The QSAR model is rebuilt using the remaining compounds.

- Prediction: The newly built model is used to predict the activity of the omitted compound.

- Repetition: Steps 2-4 are repeated until every compound in the training set has been omitted and predicted once.

- Statistical Analysis: The cross-validated correlation coefficient ( q^2 ) is calculated from the predicted versus actual activities of all compounds [25].

Supporting Data: In a study on phenanthrine-based tylophrine derivatives, models were only considered acceptable if their leave-one-out cross-validated ( q^2 ) values were greater than 0.5 for the training sets [25].

External Validation with a Test Set

Methodology: This is the most critical test for assessing a model's utility in practical drug discovery.

- Data Splitting: The full dataset is divided into a training set and an external test set. This can be done using algorithms like Kennard and Stone's to ensure the test set is representative of the chemical space [27]. A common split is 80% for training and 20% for testing [27].

- Model Building: The QSAR model is built exclusively using the training set data.

- Blind Prediction: The finalized model is used to predict the biological activities of the compounds in the external test set, which were not used in any part of the model development process.

- Performance Calculation: The correlation coefficient ( R^2 ) between the model's predictions and the experimental activities for the test set is calculated [25].

Supporting Data: A combined QSAR and virtual screening study demonstrated the power of external validation. Ten validated models were used to screen a database, and several hits were experimentally tested. The correlation between the predicted and experimental EC₅₀ for these new active compounds, along with newly synthesized derivatives, was reported to be 0.57, demonstrating the model's real-world predictive accuracy [25].

Data Randomization via Y-Randomization Test

Methodology: This test confirms that the model captures a real structure-activity relationship and not a chance correlation.

- Randomization: The biological activity values (Y-vector) of the training set are randomly shuffled, while the molecular descriptor matrix (X-matrix) is kept unchanged.

- Model Building: A new "QSAR model" is built using the randomized activity data.

- Repetition: Steps 1 and 2 are repeated multiple times (e.g., 100 times) to build numerous models based on random chance.

- Comparison: The statistical performance (e.g., ( q^2 ) and ( R^2 )) of the true model is compared to the distribution of performance from the randomized models. A powerful model will have significantly better statistics than any of the randomized models [25] [27].

Supporting Data: In a QSAR study on 4-alkoxy cinnamic analogues, the Y-randomization test produced a ( cR^2_p ) value of 0.6569. Since this value was greater than the threshold of 0.5, the authors concluded that the model was robust and not due to a chance correlation [27].

Workflow for Robust QSAR Model Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and interactions between the different validation components in a typical QSAR modeling workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This table details key computational tools and materials used in developing and validating anticancer QSAR models, as cited in the literature.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions for Anticancer QSAR Modeling

| Tool/Solution | Function in QSAR Modeling & Validation |

|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptor Software (e.g., MolConnZ, PaDEL-Descriptor) | Calculates numerical descriptors that quantify chemical structures, forming the independent variables (X-matrix) for the QSAR model [25] [27]. |

| Chemical Databases (e.g., ChemDiv Database) | Provide large collections of commercially available chemical compounds for virtual screening to discover new active hits using a validated QSAR model [25]. |

| Statistical & QSAR Modeling Software (e.g., BuildQSAR, DTC Lab Tools) | Provides algorithms (e.g., k-Nearest Neighbors, Multiple Linear Regression, Genetic Algorithm) to build the model and perform internal validation and Y-randomization tests [25] [27]. |

| Quantum Chemical Calculation Software (e.g., ORCA, Gaussian) | Used to optimize the 3D geometry of molecules and calculate quantum chemical descriptors, which are often used in more advanced 3D-QSAR studies [26] [27]. |

| Data Preprocessing & Splitting Tools | Assist in normalizing descriptor data and splitting the dataset into training and test sets using methods like the Kennard and Stone algorithm to ensure a representative external validation set [27]. |

In modern anticancer drug discovery, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models serve as indispensable computational tools for predicting compound activity and prioritizing synthesis candidates. However, a model's internal performance offers no guarantee of its real-world predictive capability for novel chemical structures. This reality makes external validation—the assessment of a model on compounds not used in its training—the cornerstone of reliable QSAR research [17] [21]. The fundamental challenge lies in selecting the most appropriate statistical parameters to evaluate this predictive ability accurately.

While the coefficient of determination (r²) has been historically common, recent scientific consensus confirms that it alone cannot indicate the validity of a QSAR model [17] [21]. Its insufficiency has spurred the development and adoption of more stringent criteria, including the Golbraikh-Tropsha parameters, the Roy's rm² metrics, and the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC). These parameters interrogate the model's predictions from different statistical perspectives, collectively providing a more robust assessment of true external predictivity. This guide provides an objective comparison of these advanced parameters, equipping computational researchers and medicinal chemists with the knowledge to build and validate more reliable anticancer QSAR models.

Methodological Protocols: Calculation and Interpretation

Golbraikh-Tropsha Criteria and Rp² Parameters

The Golbraikh-Tropsha method is not a single metric but a set of conditions a model must pass to be deemed predictive [21]. It leverages regression through the origin (RTO) to scrutinize the agreement between experimental and predicted values.

Key Parameters and Calculations:

- r²: The conventional coefficient of determination between experimental and predicted values for the test set. A threshold of r² > 0.6 is often used [21].

- r₀² and r'₀²: The coefficients of determination for regressions through the origin (predicted vs. experimental and experimental vs. predicted, respectively). These are calculated to check for biases in prediction.

- Slopes K and K': The slopes of the regression lines through the origin for (Y vs. Ypred) and (Ypred vs. Y). They should be close to 1.

Validation Conditions: A model is considered predictive if it satisfies ALL of the following conditions [21]:

- ( r^2 > 0.6 )

- ( 0.85 < K < 1.15 \ \text{or} \ 0.85 < K' < 1.15 )

- ( \frac{r^2 - r0^2}{r^2} < 0.1 \ \text{or} \ \frac{r^2 - r0'^2}{r^2} < 0.1 )

Interpretation: This method is highly regarded for its comprehensiveness, testing not just correlation but also the slope and agreement of the data with the ideal line of unity.

Roy's rm² Metrics (rm² and Δrm²)

Roy and colleagues introduced the rm² metrics as a more integrated approach to validation, which also accounts for the dispersion of data points around the regression line [21].

Calculation:

- The foundational metric is calculated as: ( rm^2 = r^2 \times \left(1 - \sqrt{r^2 - r0^2}\right) )

- In practice, two values are computed: rₘ²(original) (for experimental vs. predicted) and rₘ²(predicted) (for predicted vs. experimental).

- The Δrₘ² is the absolute difference between these two values: ( \Delta rm^2 = | rm^2(\text{original}) - r_m^2(\text{predicted}) | )

Interpretation and Thresholds:

- The primary criterion for an acceptable model is an rₘ² > 0.5 for both axes.

- Additionally, the Δrₘ² should be < 0.2. A low Δrₘ² indicates consistency in the model's performance regardless of which variable is considered dependent.

Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC)

The Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) was proposed as a simple yet powerful measure to evaluate the agreement between two measurements by measuring both precision (deviation from the best-fit line) and accuracy (deviation from the line of unity) [28].

Calculation: The CCC is calculated as follows [21]: [ \text{CCC} = \frac{2 \sum{i=1}^{n{EXT}} (Yi - \bar{Y})(\hat{Y}i - \bar{\hat{Y}}) }{ \sum{i=1}^{n{EXT}} (Yi - \bar{Y})^2 + \sum{i=1}^{n{EXT}} (\hat{Y}i - \bar{\hat{Y}})^2 + n{EXT} (\bar{Y} - \bar{\hat{Y}})^2 } ] Where ( Yi ) is the experimental value, ( \hat{Y}i ) is the predicted value, ( \bar{Y} ) and ( \bar{\hat{Y}} ) are their means, and ( n{EXT} ) is the size of the test set.

Interpretation and Thresholds:

- CCC ranges from -1 to 1. A value of 1 represents perfect agreement, 0 represents no agreement, and -1 represents perfect inverse agreement.

- A CCC > 0.8 is generally proposed as the threshold for a predictive model [21]. Studies have shown it to be one of the most restrictive and precautionary validation parameters, often providing a prudent measure of true predictivity [28].

Figure 1: A workflow for the simultaneous application of the three stringent validation parameters to a QSAR model.

Comparative Experimental Analysis

To objectively compare the performance of these validation criteria, we synthesized data from a comprehensive study that evaluated 44 published QSAR models [17] [21]. The table below summarizes the pass/fail outcomes for a representative subset of these models based on the established thresholds for each parameter set.

Table 1: Comparative Validation Outcomes for a Subset of QSAR Models

| Model ID | r² (test set) | Golbraikh-Tropsha Criteria Pass? | rₘ² > 0.5 Pass? | Δrₘ² < 0.2 Pass? | CCC > 0.8 Pass? | Overall Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.917 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Predictive |

| 3 | 0.715 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Predictive |

| 7 | 0.261 | No | No | No | No | Non-Predictive |

| 13 | 0.372 | No | No | No | No | Non-Predictive |

| 16 | 0.818 | No | No | Yes | No | Non-Predictive |

| 20 | 0.703 | No | Yes | No | No | Non-Predictive |

| 23 | 0.790 | No | No | No | No | Non-Predictive |

Analysis of Comparative Outcomes

The experimental data reveals critical insights into the behavior of these validation parameters:

High r² is Necessary but Not Sufficient: Model 16 demonstrates a high test set r² (0.818) yet fails all stringent criteria. Similarly, Model 20 (r²=0.703) fails due to a high Δrₘ², indicating inconsistency. This confirms that a high r² alone is an unreliable indicator of model predictivity [17] [21].

CCC as a Precautionary Measure: The CCC was found to be one of the most restrictive measures. In the full study, it was broadly in agreement with other measures ~96% of the time but was almost always the most precautionary, providing a robust "safety net" against accepting non-predictive models [28].

Conflict Resolution: Models that fail on one criterion but pass others (like Model 20, which passes rₘ² but fails Δrₘ² and CCC) highlight the ambiguity in validation. In such cases, the restrictive nature of the CCC can be a tie-breaker, suggesting a more prudent approach is to reject the model or undertake further refinement [28].

Table 2: Summary of Key Characteristics of the Three Stringent Parameters

| Parameter Set | Key Strength | Key Weakness / Complexity | Primary Threshold | Overall Restrictiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golbraikh-Tropsha | Comprehensive; tests multiple aspects of agreement. | Involves multiple conditions; all must be passed. | r²>0.6, 0.85 | High |

| Roy's rₘ² | Integrates correlation and dispersion; provides a consistency check (Δrₘ²). | Calculation is less intuitive than r² or CCC. | rₘ² > 0.5 and Δrₘ² < 0.2 | High |

| CCC | Directly measures agreement with the line of unity; conceptually simple and stable. | Can be overly restrictive in some contexts. | CCC > 0.8 | Very High |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for QSAR Validation

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Robust QSAR Model Validation

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function in Validation | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Datasets | Data | Provide a "ground truth" for evaluating interpretation methods and model logic. | Synthetic benchmarks with pre-defined patterns (e.g., atom-based contributions) [29]. |

| Statistical Software | Software | Calculate validation metrics and perform regression analysis. | R, Python (scikit-learn), SPSS, or specialized QSAR software. |

| CCC Calculator | Software / Code | Compute the Concordance Correlation Coefficient. | Can be implemented using the standard formula in R or Python [21]. |

| rm² Calculator | Software / Code | Compute the rₘ² and Δrₘ² metrics. | Available in specialized QSAR toolkits or via custom script [21]. |

| Chemical Standardization Tool | Software | Ensure structural consistency and remove duplicates before modeling. | Tools from RDKit, OpenBabel, or KNIME. |

| Descriptor Calculation Software | Software | Generate molecular descriptors for model building. | Dragon software, PaDEL-Descriptor, or RDKit descriptors [17]. |

Figure 2: Essential tools and their role in the QSAR model development and validation workflow.

Based on the comparative analysis, the following recommendations are proposed for researchers developing robust anticancer QSAR models:

Adopt a Multi-Metric Approach: Relying on a single parameter is inadvisable. A model's external validity should be assessed using a combination of the Golbraikh-Tropsha criteria, Roy's rₘ² metrics, and the CCC. This triangulation provides a more defensible argument for a model's predictive power.

Prioritize the CCC: Given its stability and precautionary nature, the Concordance Correlation Coefficient should be considered a cornerstone metric. A model failing the CCC > 0.8 threshold should be treated with high skepticism, regardless of its performance on other parameters [28].

Contextualize with rm²: Use Roy's rₘ² and Δrₘ² to gain insight into the consistency of the predictions. A model with a high rₘ² but also a high Δrₘ² may have underlying issues with bias that require investigation.

Go Beyond Statistics with Interpretation: For critical applications in anticancer drug discovery, statistical validation should be complemented with model interpretation to ensure the learned structure-activity relationships align with known pharmacological principles [29].

In conclusion, while the coefficient of determination (r²) provides a initial glance at model performance, the implementation of novel, stringent parameters like rm², Rp², and CCC is non-negotiable for establishing trust in the predictive capability of QSAR models, thereby accelerating and de-risking the journey of novel anticancer agents from the computer to the clinic.

In the pursuit of new anticancer drugs, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a powerful tool to predict compound activity and guide design. However, the reliability of any QSAR model is constrained by its Applicability Domain (AD)—the chemical space defined by the training compounds. Predictions for new compounds falling outside this domain are unreliable, making AD definition a critical step for robust anticancer QSAR models [2]. This guide compares the core methodologies for defining the AD, supported by experimental data and protocols from active research.

Core Methodologies for Defining the Applicability Domain

Several computational approaches exist to define the Applicability Domain. The table below compares the most prevalent methods, their underlying principles, and key considerations for application.

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range-Based Methods [2] | Defines the AD as the minimum and maximum values of each descriptor in the training set. | Simple to implement and interpret; computationally fast. | Does not account for correlation between descriptors; can define an overly simplistic, box-like domain. |

| Leverage-Based Methods (e.g., Williams Plot) | Uses Hat matrix and leverage to identify compounds structurally different from the training set. | Effective at flagging influential compounds and outliers; provides a visual diagnostic (Williams Plot). | Relies on the model's descriptor space; may not fully capture complex non-linear relationships. |

| Distance-Based Methods (e.g., Euclidean, Manhattan) | Measures the multivariate distance between a new compound and its nearest neighbors in the training set. | Intuitively measures similarity; flexible in capturing the distribution of training data. | Performance is sensitive to the choice of distance metric and scaling of descriptors. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [2] | Projects high-dimensional descriptor data into a lower-dimensional space defined by principal components (PCs). | Reduces complexity and multi-collinearity; allows for visual inspection of the chemical space in 2D/3D score plots. | The defined AD in PC space is dependent on the variance captured by the selected PCs. |

The following workflow illustrates how these methods are integrated into the QSAR modeling process to define and apply the Applicability Domain.

Case Study: AD in Anticancer Naphthoquinone QSAR Models

A 2025 study on 1,4-naphthoquinone derivatives provides a practical example of QSAR development and validation, underscoring the importance of the Applicability Domain [30].

Experimental Protocol

- Objective: To construct predictive QSAR models for the anticancer activity of 1,4-naphthoquinones against four human cancer cell lines (HepG2, HuCCA-1, A549, MOLT-3) [30].

- Bioactivity Data: Cytotoxic activity (IC50 values) was determined experimentally using standardized MTT and XTT assays on the cancer cell lines. A normal cell line (MRC-5) was used to assess selectivity [30].

- Modeling Process:

- Descriptor Calculation: A wide range of molecular descriptors were computed from the chemical structures.

- Model Construction: Four separate QSAR models (one per cell line) were built using the Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) algorithm.

- Validation: Model performance was rigorously evaluated on both training and external test sets [30].

- Key Structural Descriptors: The models identified that potent anticancer activity was primarily influenced by descriptors related to polarizability, van der Waals volume, electronegativity, dipole moment, and molecular shape [30]. These descriptors collectively define the relevant chemical space for this class of compounds.

Performance Metrics and Model Robustness

The table below summarizes the performance metrics of the constructed QSAR models, demonstrating their predictive robustness within their applicability domain [30].

| Cancer Cell Line | Training Set R | Testing Set R | Training Set RMSE | Testing Set RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HepG2 | 0.8928 | 0.7824 | 0.2600 | 0.3748 |

| HuCCA-1 | 0.9664 | 0.9157 | 0.1755 | 0.2726 |

| A549 | 0.9445 | 0.8493 | 0.2038 | 0.3408 |

| MOLT-3 | 0.9496 | 0.8365 | 0.1933 | 0.3511 |

R: Correlation coefficient; RMSE: Root Mean Square Error [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the featured QSAR case study, which are essential for similar experimental workflows in anticancer drug discovery.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Human Cancer Cell Lines (HepG2, HuCCA-1, A549, MOLT-3) | In vitro models for evaluating the cytotoxic potency and selectivity of tested compounds [30]. |

| Cell Culture Media (RPMI-1640, DMEM, Hamm's F12) | Provides essential nutrients to maintain cell viability and support cell growth under controlled conditions [30]. |

| MTT/XTT Reagent | Tetrazolium salts used in colorimetric assays to quantitatively measure cell viability and proliferation after compound treatment [30]. |

| Reference Drugs (Doxorubicin, Etoposide) | Well-characterized anticancer agents used as positive controls to validate the experimental assay and benchmark the activity of new compounds [30]. |

| Molecular Descriptor Software | Computational tools used to translate the chemical structure of a compound into a set of numerical values (descriptors) that quantify its physicochemical properties [30] [2]. |

Defining the Applicability Domain is not an optional step but a fundamental requirement for generating trustworthy QSAR predictions in anticancer research. No single method is universally superior; a consensus approach, combining multiple techniques, often provides the most robust assessment of whether a new compound falls within the model's reliable scope [2]. As demonstrated in the naphthoquinone study, a well-validated model operating within its AD can successfully guide the rational design of new chemical entities, significantly accelerating the drug discovery pipeline while conserving valuable resources [30].

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, creating an urgent need for more effective and less toxic therapeutic agents [31] [32]. Natural products (NPs) represent a valuable source for anticancer drug discovery due to their structural diversity and biological activities [31] [8]. However, the identification of promising compounds through experimental methods alone is time-consuming and costly. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling has emerged as a powerful computational tool that can predict the biological activity of compounds based on their chemical structures, thereby accelerating the drug discovery process [33] [2].

The reliability of any QSAR model depends critically on the application of robust validation techniques [17]. A model that performs well on its training data may fail to predict the activity of new compounds if not properly validated, a phenomenon known as overfitting [17] [33]. This case study examines the development and, more importantly, the rigorous validation of a QSAR model designed to identify natural products with anti-breast cancer activity against the MCF-7 cell line, framing it within the broader context of statistical validation criteria for robust anticancer QSAR models [31].

Theoretical Foundations of QSAR Validation

The Critical Importance of Validation in QSAR Modeling

QSAR modeling formally began in the early 1960s with the works of Hansch and Fujita, and Free and Wilson, establishing the principle that biological activity can be correlated with quantitative descriptors of chemical structure [2]. The fundamental steps in QSAR development include dataset collection, data curation, molecular descriptor calculation, model construction, and—most critically—validation [33]. Without proper validation, QSAR models may produce unreliable predictions that cannot be translated into successful drug candidates.

Statistical validation ensures that a QSAR model possesses both internal robustness (the ability to perform consistently on the data used to build it) and external predictivity (the ability to accurately predict new, unseen compounds) [17] [33]. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has established principles for QSAR validation, emphasizing the need for defined endpoints, unambiguous algorithms, appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity, and a mechanistic interpretation where possible [34].

Key Statistical Parameters for QSAR Validation

Multiple statistical parameters are used to evaluate QSAR models, each providing different insights into model performance. No single parameter is sufficient to confirm model validity [17].

Internal Validation Parameters: These assess the model's stability and predictability on the training set compounds, typically using cross-validation techniques.

- R² (Coefficient of Determination): Measures the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. Values closer to 1.0 indicate a better fit.

- R²adj (Adjusted R²): Adjusts R² for the number of descriptors in the model, penalizing overfitting.

- Q²Loo (Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation Coefficient): Assesses model predictivity by iteratively leaving one compound out, training the model on the rest, and predicting the left-out compound [31] [33].

External Validation Parameters: These are the ultimate test of a model's real-world utility, evaluating its performance on a completely independent test set not used in model development.