Beyond GAPDH and ACTB: A Modern Guide to Selecting Stable Reference Genes for Accurate qPCR in Cancer Research

Accurate gene expression analysis via qPCR is foundational to cancer research, yet a pervasive reliance on traditional reference genes like GAPDH and ACTB frequently leads to data distortion and irreproducible...

Beyond GAPDH and ACTB: A Modern Guide to Selecting Stable Reference Genes for Accurate qPCR in Cancer Research

Abstract

Accurate gene expression analysis via qPCR is foundational to cancer research, yet a pervasive reliance on traditional reference genes like GAPDH and ACTB frequently leads to data distortion and irreproducible results. This article synthesizes recent evidence to provide a comprehensive framework for selecting and validating stable reference genes tailored to specific cancer models and experimental conditions, including hypoxia, dormancy, and drug treatments. We detail the perils of using common but unstable housekeeping genes, present robust methodological workflows for gene identification, and underscore the critical need for multi-algorithm validation to ensure reliable normalization, ultimately empowering researchers to generate more trustworthy and biologically relevant data.

Why Traditional Housekeeping Genes Fail in Cancer Research: The Foundation of Accurate qPCR

The Critical Role of Reference Genes in qPCR Normalization

In the field of cancer research, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) has become a cornerstone technique for analyzing gene expression patterns that drive tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. However, the accuracy of this powerful method hinges entirely on a critical methodological step: proper normalization using stably expressed reference genes (RGs), also known as housekeeping genes (HKGs). When researchers use inappropriate reference genes, all subsequent gene expression data become compromised, leading to inaccurate conclusions and irreproducible results. This is particularly problematic in cancer studies, where cellular conditions such as hypoxia, dormancy, and metabolic stress can dramatically alter the expression of commonly used reference genes. This technical guide explores the critical importance of rigorous reference gene validation in cancer research, providing researchers with frameworks for selecting appropriate normalization strategies across diverse experimental conditions.

The Fundamental Importance of Reference Gene Validation

Why Reference Genes Matter in qPCR

RT-qPCR enables precise quantification of gene expression by measuring the accumulation of PCR products in real-time. However, technical variations in RNA quantity, quality, and reverse transcription efficiency can introduce significant artifacts. Reference genes correct for these variations by providing an internal control for endogenous normalization. The ideal reference gene is constitutively expressed at a constant level across all tissue types, developmental stages, and experimental conditions [1]. In practice, however, numerous studies have demonstrated that biological systems are dynamic and constantly responding to their environment, making it unlikely that a single universal reference gene exists [1] [2].

The consequences of improper reference gene selection are profound. A poorly chosen reference gene can obscure genuine expression patterns or create artificial ones, potentially invalidating research conclusions. This is especially critical in cancer research, where gene expression signatures increasingly inform molecular phenotyping, diagnostic classifications, and therapeutic decisions [1] [2].

The Pitfall of "Traditional" Housekeeping Genes

Many researchers routinely default to classic housekeeping genes like GAPDH, ACTB (β-actin), and 18S rRNA without validating their stability under specific experimental conditions. Accumulating evidence strongly cautions against this practice, particularly in cancer studies:

GAPDH encodes a glycolytic enzyme that also functions as a multifunctional "moonlighting" protein involved in diverse cellular processes including apoptosis, transcriptional regulation, and DNA repair [1] [2]. Its expression is influenced by numerous factors including insulin, growth hormone, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and tumor protein p53. Alarmingly, GAPDH has been implicated in many oncogenic processes, such as tumor survival, hypoxic tumor growth, and angiogenesis, and shows substantial variability across tissues and individuals [1] [2].

ACTB, which encodes a cytoskeletal protein, demonstrates variable expression in response to experimental manipulations and can be problematic in conditions that alter cell morphology or cytoskeletal organization [1]. In dormant cancer cells induced by mTOR inhibition, ACTB expression undergoes dramatic changes, rendering it "categorically inappropriate" for normalization in these experimental systems [3].

Ribosomal genes (e.g., RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A) also show significant instability in certain cancer models, particularly under conditions of translational stress such as mTOR inhibition [3].

The table below summarizes traditional reference genes and their limitations in cancer research:

Table 1: Commonly Used Reference Genes and Their Limitations in Cancer Studies

| Reference Gene | Primary Function | Limitations in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Glycolytic enzyme | Multifunctional protein; expression induced by hypoxia, oxidative stress, insulin; implicated in tumor survival and progression |

| ACTB (β-actin) | Cytoskeletal structural protein | Expression varies with cell morphology changes; unstable in dormant cancer cells and cytoskeletal remodeling conditions |

| 18S rRNA | Ribosomal RNA component | Often excessively abundant; may not correlate with mRNA expression patterns; stability varies under stress conditions |

| TUBα (Tubulin) | Cytoskeletal structural protein | Expression varies during cell division; unstable in microtubule-targeting therapies |

| RPS23/RPS18 | Ribosomal proteins | Expression dramatically changes under mTOR inhibition and translational stress |

Reference Gene Performance in Cancer Research Models

Dormant Cancer Cells and mTOR Inhibition

Recent investigations into dormant cancer cells have highlighted the critical need for condition-specific reference gene validation. In 2025, a systematic study analyzed 12 candidate reference genes in T98G (glioblastoma), A549 (lung adenocarcinoma), and PA-1 (ovarian teratocarcinoma) cancer cell lines treated with the dual mTOR inhibitor AZD8055 to induce dormancy [3].

The researchers found that ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, and RPL13A underwent "dramatic changes" in expression and were "categorically inappropriate for RT-qPCR normalization in cancer cells treated with dual mTOR inhibitors" [3]. The optimal reference genes varied by cell line:

- A549 cells: B2M and YWHAZ performed best

- T98G cells: TUBA1A and GAPDH were most stable

- PA-1 cells: No optimal reference genes were identified among the 12 candidates

This study exemplifies how reference gene stability is cell-type specific, even within the same experimental paradigm, and underscores the danger of assuming that a reference gene validated in one cellular context will transfer to another.

Hypoxia Studies in Breast Cancer

Hypoxia is a common feature of solid tumors linked to therapy resistance and advanced disease. Because hypoxia dramatically reprograms cellular transcription and metabolism, traditional reference genes like GAPDH and PGK1 are particularly unsuitable for hypoxic conditions [4].

A 2025 study systematically identified robust reference genes for studying hypoxia in breast cancer cell lines representing Luminal A (MCF-7, T-47D) and triple-negative (MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468) subtypes [4]. After evaluating candidate genes in normoxia, acute hypoxia (1% O2, 8h), and chronic hypoxia (1% O2, 48h), the researchers identified RPLP1 and RPL27 as optimal reference genes across all conditions and cell lines [4].

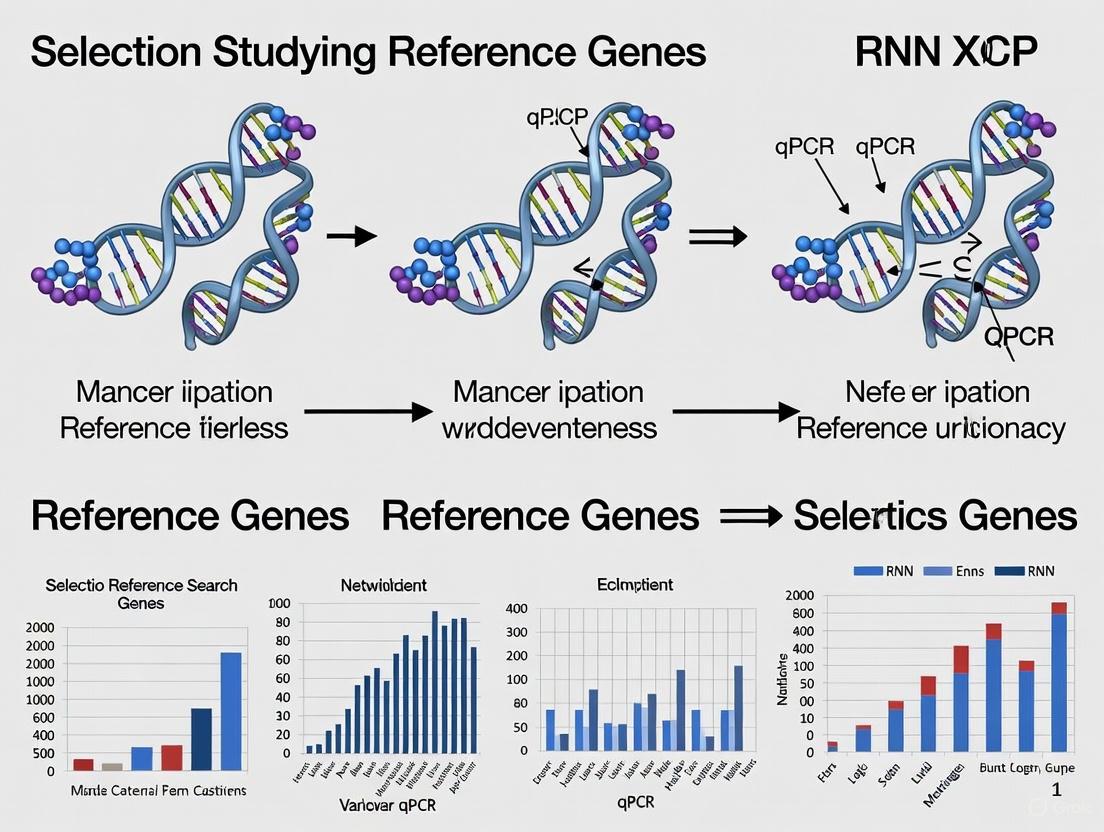

The experimental workflow for this systematic approach is detailed below:

Endometrial Cancer and Hormone Receptor Studies

In endometrial cancer research, improper reference gene selection has been linked to significant discrepancies in reported expression levels of sex hormone receptors [2]. A comprehensive review published in 2025 emphasized that GAPDH is unsuitable as a housekeeping gene for studies on both normal endometrium and endometrial cancer [2].

Accumulating evidence suggests that GAPDH may actually function as a pan-cancer marker in endometrial cancer rather than a stable normalizer [2]. The review advocates for using at least two validated reference genes for target gene expression recalculations—a technical aspect rarely applied in final data processing but critical for accuracy [2].

Experimental Framework for Reference Gene Validation

Selection of Candidate Genes

The first step in reference gene validation is selecting appropriate candidate genes. Ideal candidates should:

- Exhibit minimal variability in expression across your specific experimental conditions

- Be expressed at roughly similar levels to your target genes of interest

- Have well-annotated sequences for reliable primer design

- Represent diverse functional pathways to avoid co-regulation

Commonly evaluated candidate genes across various cancer studies include:

Table 2: Candidate Reference Genes Evaluated in Recent Cancer Studies

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Primary Function | Reported Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| B2M | β-2-microglobulin | Component of MHC class I molecules | Stable in A549 dormant cells [3] |

| YWHAZ | Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase | Signal transduction regulation | Stable in A549 dormant cells [3] |

| TUBA1A | Tubulin alpha 1a | Cytoskeletal structure | Stable in T98G dormant cells [3] |

| RPLP1 | Ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P1 | Ribosomal protein | Optimal in hypoxic breast cancer [4] |

| RPL27 | Ribosomal protein L27 | Ribosomal protein | Optimal in hypoxic breast cancer [4] |

| RPL13A | Ribosomal protein L13a | Ribosomal protein | Stable in hypoxic PBMCs [5] |

| PSAP | Prosaposin | Lysosomal protein processing | Stable in porcine macrophages [6] |

| TBP | TATA-box binding protein | Transcription initiation | Variable in breast cancer [4] |

| HPRT | Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase | Purine synthesis | Moderate stability in hypoxia [5] |

Comprehensive Validation Workflow

A robust reference gene validation protocol involves multiple experimental and computational steps:

Computational Analysis Methods

Several well-established algorithms are available for assessing reference gene stability, each with distinct advantages:

- geNorm: Calculates a stability measure (M) based on the average pairwise variation between genes; also determines the optimal number of reference genes by calculating pairwise variation (V) [7] [6] [5]

- NormFinder: Estimates both intra- and inter-group variation, providing a stability value that considers sample subgroups [7] [6] [5]

- BestKeeper: Relies on raw Cq (quantification cycle) values and calculates standard deviations to identify stable genes [7] [5]

- ΔCt Method: Compares relative expression of pairs of genes within each sample [5]

- RefFinder: Web-based tool that integrates all four algorithms to generate a comprehensive ranking [5] [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Reference Gene Validation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | Extraction of high-quality total RNA | Select kits with DNase treatment; assess RNA integrity (RIN >8) |

| Reverse Transcriptase Kits | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | Use consistent enzyme and random/oligo-dT primer mix |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Amplification with fluorescent detection | Select SYBR Green or probe-based depending on application |

| Validated Primer Assays | Gene-specific amplification | Ensure high efficiency (90-110%) and specificity (single melt curve peak) |

| Nuclease-free Water | Dilution of RNA and reagents | Essential for preventing RNase contamination |

| Standard Curve Materials | Assessment of amplification efficiency | Use serial dilutions of pooled cDNA; R² >0.99 ideal |

| MicroAmp Fast Optical Plates | Reaction vessels for qPCR | Ensure compatibility with thermal cycler platform |

| Positive Control RNAs | Assessment of reverse transcription | Use standardized reference materials when available |

Best Practices for Implementation in Cancer Research

Based on current evidence, cancer researchers should adopt the following practices for reference gene normalization:

Always Validate Reference Genes for Specific Conditions: Never assume that a reference gene stable in one cancer type, treatment condition, or cellular context will perform adequately in another [3] [4].

Use Multiple Reference Genes: Normalize against at least two validated reference genes to improve accuracy and reliability [2]. The geNorm algorithm can determine the optimal number of reference genes for your experimental system [6].

Avoid GAPDH as a Default Choice: In many cancer contexts, particularly endometrial cancer and hypoxic conditions, GAPDH is unsuitable as a reference gene and may actually be a marker of disease progression [2] [4].

Consider Ribosomal Proteins: In some cancer models, particularly under hypoxic conditions, ribosomal proteins like RPLP1, RPL27, and RPL13A demonstrate superior stability compared to traditional reference genes [5] [4].

Report Validation Data: Publications should include detailed information about reference gene selection, stability values, and the number of genes used for normalization to enhance reproducibility.

Re-validate for New Conditions: Any significant change in experimental parameters (cell type, treatment, environmental conditions) warrants re-validation of reference gene stability.

The critical role of reference genes in qPCR normalization cannot be overstated, particularly in cancer research where accurate gene expression data informs our understanding of tumor biology and therapeutic development. As this technical guide demonstrates, the practice of using traditional housekeeping genes without rigorous validation is methodologically unsound and potentially misleading. Instead, researchers must adopt a systematic, condition-specific approach to reference gene selection, employing multiple computational tools to identify optimal normalizers for their unique experimental systems. By implementing these robust validation protocols, cancer researchers can ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of their gene expression studies, ultimately advancing our understanding of cancer biology and therapeutic development.

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway serves as a critical regulator of cell growth, proliferation, and metabolism in response to environmental cues. In cancer biology, pharmacological inhibition of mTOR has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy that can induce a reversible dormant state in tumor cells. However, this suppression of mTOR—a master regulator of global translation—significantly rewires basic cellular functions and profoundly influences the expression of traditional housekeeping genes used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) normalization. This case study examines how mTOR inhibition destabilizes commonly used reference genes, potentially distorting gene expression profiles in dormant cancer cells and compromising research conclusions. Through experimental validation across multiple cancer cell lines, we demonstrate that genes once considered stable internal controls, particularly ACTB (β-actin) and ribosomal proteins like RPS23, undergo dramatic expression changes following mTOR suppression, establishing an imperative for rigorous reference gene validation in studies involving mTOR pathway modulation.

The mTOR kinase represents a clinically recognized key target for eliminating cancer cells with increased PI3K/mTOR signaling activity that contributes to tumor growth and proliferation [3]. According to preclinical and clinical studies, effective suppression of mTOR by dual inhibitors leads to a reduction in the size of solid tumors in vivo and patient stabilization [3]. However, these promising results have a significant limitation: pharmacological mTOR suppression may generate numerous dormant cancer cells that resist conventional therapies [3] [8].

A key property of dormant tumor cells is reversible cell cycle arrest in the G1/G0 phase, but knowledge of specific signaling pathways and markers remains limited [3]. Recent studies have revealed that suppression of the mTOR kinase can be a molecular determinant of dormant cancer cells, with pharmacological inhibition of mTOR forming the mechanistic basis for producing dormant tumor cells in vitro [3]. When cancer cells enter this dormant state under mTOR inhibition, they undergo extensive proteome changes caused by the shutdown of global mTOR-dependent mRNA translation and activation of alternative translation pathways [3].

These dramatic mTOR-dependent alterations in proteostasis can induce responsive changes in basic cellular functions, potentially modulating the stable expression of housekeeping genes under a dormant phenotype. Despite numerous published datasets on cancer cells treated with dual mTOR inhibitors, analysis of the stable expression of housekeeping genes has been largely overlooked [3]. To prevent potential errors in interpreting gene expression results in dormant cancer cells, researchers must ensure that relevant reference genes are available for RT-qPCR data normalization obtained from tumor cells after mTOR suppression.

mTOR Signaling Fundamentals and Inhibition Mechanisms

The mTOR Signaling Pathway

The mammalian or mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a serine/threonine kinase that belongs to the phosphoinositide 3-kinase related protein kinase (PIKK) superfamily [9]. In mammalian cells, mTOR functions through two evolutionarily conserved complexes: mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2), which share some common subunits but perform distinct cellular functions [9] [10].

mTORC1 is sensitive to rapamycin and contains regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (RAPTOR) and proline-rich substrate of 40 kDa (PRAS40) [9]. This complex integrates signals from multiple growth factors, nutrients, and energy supply to promote cell growth when energy is sufficient and catabolism during nutrient scarcity [10]. mTORC1 primarily regulates cell growth and metabolism by phosphorylating downstream effectors such as eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1) and S6 kinase (S6K), which motivate protein translation, synthesis of nucleotides and lipids, biogenesis of lysosomes, and suppression of autophagy [9].

mTORC2 is comparatively resistant to rapamycin and contains rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (RICTOR) and mammalian stress-activated protein kinase interacting protein 1 (mSIN1) [9]. This complex mainly controls cell proliferation and survival by phosphorylating downstream targets like serum glucose kinase (SGK) and protein kinase C (PKC), thereby intensifying signaling cascades that increase cytoskeletal rebuilding and cell migration while inhibiting apoptosis [9] [10].

mTOR Inhibition and Cellular Consequences

The PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway plays a crucial role in regulating cell survival, metabolism, growth, and protein synthesis in response to upstream signals in both normal physiological and pathological conditions [9] [11]. Aberrant mTOR signaling resulting from genetic alterations at different levels of the signal cascade is commonly observed in various cancers, with mTOR being aberrantly overactivated in more than 70% of cancers [9]. Upon hyperactivation, mTOR signaling promotes cell proliferation and metabolism that contribute to tumor initiation and progression [9].

mTOR inhibitors are classified into three generations:

- First-generation inhibitors (rapamycin and its analogs, called rapalogs) interact with FKBP12, which then binds to the FRB domain of mTOR, specifically inhibiting mTORC1 [11].

- Second-generation inhibitors (ATP-competitive inhibitors) compete with ATP molecules for attachment to the mTOR kinase domain, simultaneously targeting both mTORC1 and mTORC2 [11].

- Third-generation inhibitors are designed to be active against drug-resistant cancer cells with mTOR FRB/kinase domain mutations [11].

In the context of cancer therapy, mTOR inhibition can induce a paradoxical effect. While suppressing tumor expansion, it simultaneously facilitates the development of a reversible drug-tolerant senescent state, allowing a subpopulation of cancer cells to persist despite therapeutic challenge [8]. These "persister" cells display a senescence phenotype and can resume proliferation after drug withdrawal, representing a significant challenge in cancer treatment [8].

Figure 1: mTOR Signaling Pathway and Key Cellular Functions. The diagram illustrates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade, highlighting the central role of mTOR complexes in regulating critical cellular processes including protein translation and cytoskeletal organization—processes that directly involve commonly used reference genes like ACTB and RPS23.

Experimental Evidence: Systematic Evaluation of Reference Gene Stability Under mTOR Inhibition

Experimental Design and Model Systems

A comprehensive study published in Scientific Reports (2025) addressed the critical need for validated reference genes in mTOR-suppressed cancer cells [3]. The researchers established an in vitro model of cancer cell dormancy using the dual mTOR inhibitor AZD8055 to convert proliferative cancer cells into a dormant state across three tumor cell lines of different origins:

- A549 - lung adenocarcinoma

- T98G - glioblastoma

- PA-1 - ovarian teratocarcinoma

Cells were treated with AZD8055 at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 10 µM for one week, followed by assessment of viability, proliferation recovery, and spheroid formation capacity [3]. The AZD8055 concentration of 10 µM was selected as optimal for generating a robust population of mTOR-suppressed cancer cells exhibiting key characteristics of dormancy, including significantly reduced cell size and reversible proliferation arrest [3].

To identify appropriate reference genes for RT-qPCR normalization in these dormant cancer cells, the researchers evaluated 12 candidate reference genes selected from among widely used references according to the literature: GAPDH, ACTB, TUBA1A, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A, PGK1, EIF2B1, TBP, CYC1, B2M, and YWHAZ [3]. Primer specificity was rigorously assessed with coefficients of determination (R²), efficiency coefficients (E), and melt curve analyses to ensure accurate quantification of expression stability [3].

Quantitative Findings: Reference Gene Stability Rankings

The experimental results demonstrated striking differences in reference gene stability across cell lines following mTOR inhibition, with traditional housekeeping genes showing particularly pronounced instability.

Table 1: Stability Ranking of Reference Genes in mTOR-Inhibited Cancer Cell Lines

| Cell Line | Most Stable Reference Genes | Least Stable Reference Genes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| A549 (Lung adenocarcinoma) | B2M, YWHAZ | ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A | Ribosomal protein genes showed dramatic expression changes |

| T98G (Glioblastoma) | TUBA1A, GAPDH | ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A | ACTB and ribosomal proteins categorically inappropriate |

| PA-1 (Ovarian teratocarcinoma) | No optimal genes identified | ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A | High sensitivity to culture conditions confounded identification |

The most significant finding across all cell lines was that ACTB (encoding β-actin cytoskeleton) and the ribosomal protein genes RPS23, RPS18, and RPL13A underwent dramatic expression changes and were deemed "categorically inappropriate for RT-qPCR normalization in cancer cells treated with dual mTOR inhibitors" [3]. This instability directly reflects the cellular reprogramming induced by mTOR inhibition: reduced cytoskeletal reorganization and fundamental alterations in ribosomal biogenesis and function.

Table 2: Expression Stability of Traditional Housekeeping Genes Under mTOR Inhibition

| Gene | Cellular Function | Impact of mTOR Inhibition | Suitability as Reference Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACTB | Cytoskeletal structural protein | Dramatic expression changes due to altered cytoskeletal organization | Not recommended - highly unstable |

| RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A | Ribosomal proteins | Severe suppression due to global translation shutdown | Not recommended - highly unstable |

| GAPDH | Glycolytic enzyme | Variable stability (suitable in T98G, less stable in others) | Cell line-dependent |

| TUBA1A | Cytoskeletal microtubule | Relatively stable in T98G cells | Cell line-dependent |

| B2M, YWHAZ | Signaling adaptor proteins | Most stable in A549 cells | Recommended for specific cell types |

The validation experiments demonstrated that incorrect selection of a reference gene resulted in significant distortion of the gene expression profile in dormant cancer cells, potentially leading to erroneous biological conclusions [3]. This underscores the critical importance of specifically validating reference genes for each experimental system involving mTOR pathway modulation.

Molecular Mechanisms Linking mTOR Inhibition to Reference Gene Destabilization

Global Translational Control and Ribosomal Gene Expression

The destabilization of ribosomal protein genes (RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A) under mTOR inhibition can be directly attributed to the central role of mTORC1 in regulating protein synthesis. mTORC1 promotes translation initiation and ribosome biogenesis through phosphorylation of key effectors:

- S6K (S6 kinase): Phosphorylates the S6 ribosomal protein and other targets to enhance the translation of mRNAs containing a 5' terminal oligopyrimidine (TOP) tract, which includes many ribosomal proteins and translation factors [9] [10].

- 4E-BP1 (eIF4E-binding protein): When phosphorylated by mTORC1, releases eIF4E to initiate cap-dependent translation [9] [10].

Pharmacological inhibition of mTOR thus suppresses global protein synthesis by simultaneously inactivating S6K and preventing 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, leading to reduced expression of ribosomal proteins and translation factors [3]. Since genes like RPS23, RPS18, and RPL13A encode structural components of the ribosome, their expression is particularly vulnerable to mTOR inhibition, explaining their unsuitability as reference genes under these conditions.

Cytoskeletal Remodeling and ACTB Destabilization

The profound instability of ACTB (β-actin) following mTOR inhibition reflects extensive cytoskeletal remodeling in dormant cancer cells. Several interconnected mechanisms contribute to this phenomenon:

- mTORC2 directly regulates actin cytoskeletal organization through phosphorylation of PKCα and other substrates, controlling cell shape and motility [9] [10]. Inhibition of mTOR disrupts these regulatory networks, triggering compensatory changes in actin expression and dynamics.

- Dormant cancer cells undergo significant reduction in cell size as measured by forward scatter in flow cytometry, indicating substantial cytoskeletal reorganization [3]. This morphological adaptation directly impacts the expression of structural genes like ACTB.

- mTOR inhibition alters cellular metabolism toward catabolic processes, which may involve restructuring of the actin cytoskeleton to conserve energy and resources [10].

These coordinated changes in cytoskeletal organization explain why ACTB expression becomes highly variable in mTOR-suppressed cells, despite its widespread use as a "housekeeping" gene in conventional cell cultures.

Cell-Type Specific Variations in Gene Stability

The differential stability of reference genes across cell lines (e.g., GAPDH stability in T98G but not PA-1 cells) highlights the importance of cell-type specific factors in determining gene expression responses to mTOR inhibition. Several elements contribute to these variations:

- Baseline expression levels: Genes expressed at very high or very low levels may show greater variability following pathway perturbations.

- Lineage-specific dependencies: Different cell types may rely on distinct metabolic and structural pathways, creating lineage-specific patterns of gene regulation.

- Proliferation status: Rapidly dividing versus slow-cycling cells may exhibit different susceptibilities to mTOR inhibition.

- Genetic background: Mutations in upstream regulators of mTOR (e.g., PTEN, PI3K, TSC1/2) can modulate cellular responses to mTOR inhibitors.

These factors collectively necessitate experimental validation of reference genes for each specific cell model and experimental condition, rather than relying on presumed "universal" reference genes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Reference Gene Validation in mTOR Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| mTOR Inhibitors | AZD8055, INK128, Rapamycin, Torin1 | Induce dormancy and validate reference gene stability | Dual inhibitors (AZD8055) provide complete mTOR blockade |

| Reference Gene Candidates | B2M, YWHAZ, TUBA1A, GAPDH, ACTB, RPS23 | Test expression stability across experimental conditions | Include both traditional and alternative candidates |

| Cell Line Models | A549, T98G, PA-1, MIA PaCa-2 | Provide diverse genetic backgrounds for validation | Select lines relevant to research focus |

| Validation Algorithms | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, comparative ΔCt | Statistically determine expression stability | Use multiple algorithms for consensus |

| qPCR Reagents | Specific primers with validation data, high-efficiency master mixes | Accurate quantification of gene expression | Verify primer efficiency (90-110%) |

Recommended Experimental Protocol for Reference Gene Validation

Step-by-Step Validation Workflow

Based on the methodological approach described in the primary study [3] and complemented by established best practices in the field [12] [13], the following protocol is recommended for validating reference genes in mTOR inhibition studies:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Reference Gene Validation. This diagram outlines a systematic approach for validating reference genes under mTOR inhibition conditions, highlighting key considerations at each step to ensure reliable results.

Implementation Guidelines

Establish mTOR Inhibition Model: Treat relevant cancer cell lines with mTOR inhibitors across a concentration range (e.g., 0.5-10 µM AZD8055) for sufficient duration (e.g., 1 week) to establish dormancy. Verify efficacy through measures like reduced cell size, proliferation arrest, and pathway phosphorylation status [3].

Select Candidate Reference Genes: Choose 3-12 candidate genes representing different functional classes. Always include both traditional housekeeping genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH) and alternative genes identified in previous studies (e.g., B2M, YWHAZ, TUBA1A) [3] [13].

Design and Validate qPCR Primers: Ensure primer specificity through:

- Efficiency testing with serial dilutions (R² > 0.98, efficiency 90-110%)

- Melt curve analysis for single amplification products

- Verification of no genomic DNA amplification [3]

RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR: Isolve high-quality RNA (RIN > 7) with DNase treatment. Use consistent reverse transcription conditions with appropriate controls. Perform qPCR with sufficient technical and biological replicates (minimum n=3 per condition) [3] [13].

Expression Stability Analysis: Analyze results using multiple algorithms:

- geNorm: Determines stability measure M (lower M = greater stability)

- NormFinder: Estimates intra- and inter-group variation

- BestKeeper: Uses pairwise correlations based on Cq values

- Comparative ΔCt: Evaluates consistency of relative expression [13]

Validation of Selected Genes: Confirm the stability of selected reference genes by normalizing target genes of interest. Demonstrate that appropriate reference gene selection significantly impacts experimental conclusions [3].

This case study demonstrates that mTOR inhibition profoundly destabilizes commonly used reference genes, particularly those involved in cytoskeletal organization (ACTB) and ribosomal function (RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A). The dramatic rewiring of cellular physiology under mTOR suppression extends to fundamental processes typically considered "housekeeping" in nature, necessitating a paradigm shift in how reference genes are selected for gene expression studies in this context.

The implications for cancer research and drug development are substantial. As mTOR inhibitors continue to be investigated as therapeutic agents and tools for studying cancer dormancy, the validity of gene expression data hinges on appropriate normalization strategies. Researchers must abandon the presumption that traditional reference genes remain stable under these perturbed conditions and instead implement systematic validation protocols specific to their experimental systems.

The findings further suggest that the concept of "housekeeping genes" requires refinement in the context of pathway-targeted therapies. Rather than representing a fixed set of genes, stable reference candidates must be identified empirically for each biological context, particularly when targeting master regulators like mTOR that orchestrate diverse cellular processes. By adopting the rigorous validation approaches outlined in this case study, researchers can ensure the reliability and reproducibility of gene expression data in mTOR pathway research, ultimately advancing our understanding of cancer biology and therapeutic resistance mechanisms.

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is one of the most commonly used housekeeping genes for normalization in gene expression analyses. However, emerging pan-cancer evidence reveals that GAPDH is frequently dysregulated in malignant tissues, exhibiting overexpression correlated with poor prognosis across diverse cancer types. This whitepaper synthesizes current molecular evidence demonstrating GAPDH's oncogenic roles, detailing the regulatory mechanisms driving its overexpression, and providing validated experimental frameworks for selecting appropriate reference genes in cancer research. The findings necessitate a paradigm shift in how researchers approach internal controls for quantitative PCR (qPCR) in oncological studies, moving beyond traditional housekeeping genes to more stable, context-specific reference signatures.

GAPDH has long been classified as a housekeeping gene due to its fundamental role in glycolysis and its constitutive expression across most tissue types. This perception established GAPDH as a default internal control for quantifying DNA, RNA, and proteins in countless biological experiments, including cancer studies [14] [15]. However, the foundational assumption that GAPDH expression remains constant across physiological and pathological states is fundamentally flawed in oncology research.

Systematic bioinformatic investigations now confirm that GAPDH is not merely a metabolic enzyme but a multifunctional protein involved in diverse cancer-related processes, including regulation of mRNA stability, DNA repair, and cell death [15] [16]. Its expression is significantly elevated in the majority of human cancers, where it correlates strongly with adverse clinical outcomes, thus invalidating its utility as a neutral reference gene [14] [15] [17]. This whitepaper consolidates the pan-cancer evidence against using GAPDH as an internal control and provides methodological guidance for proper reference gene selection in cancer gene expression studies.

Pan-Cancer Evidence: GAPDH Overexpression and Prognostic Implications

Comprehensive analyses of large-scale cancer genomics datasets have systematically quantified GAPDH dysregulation across human malignancies, revealing consistent patterns of overexpression with significant clinical implications.

Systematic Overexpression in Tumor Tissues

A comprehensive pan-cancer analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data demonstrated that GAPDH mRNA expression is significantly elevated in almost all tumor types compared to adjacent normal tissues. Notable exceptions are limited, with prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) being a rare cancer type that did not exhibit differential GAPDH expression [14] [18]. This overexpression pattern is conserved at the protein level, as validated through Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) data, which showed significantly higher GAPDH protein levels in ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD) [14]. Immunohistochemical analyses from the Human Protein Atlas corroborate these findings, showing low-to-medium staining intensity in normal ovary, kidney, lung, and pancreas tissues, contrasted with medium-to-strong staining in corresponding tumor tissues [14] [17].

Table 1: GAPDH Expression Across Selected Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | mRNA Expression | Protein Expression | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA) | Significantly elevated | N/A | P<0.05 |

| Lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) | Significantly elevated | N/A | P<0.05 |

| Liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) | Significantly elevated | Elevated | P<0.05 |

| Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) | Significantly elevated | Elevated | P<0.05 |

| Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) | Significantly elevated | Elevated | P<0.05 |

| Prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) | Not significantly different | N/A | Not significant |

Association with Poor Clinical Outcomes

Survival analyses across multiple cancer types reveal that high GAPDH expression consistently predicts poor patient prognosis. In TCGA cohort studies, tumors with elevated GAPDH levels demonstrated significantly worse overall survival (OS) in multiple cancer types, including cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), brain lower grade glioma (LGG), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), LUAD, and mesothelioma (MESO) [14]. Similarly, deteriorated disease-free survival (DFS) rates were observed in KIRC, kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), LGG, MESO, PAAD, sarcoma (SARC), and thymoma (THYM) among patients with high GAPDH expression [14]. The Human Protein Atlas independently validates GAPDH as a prognostic marker in liver cancer, lung cancer, and renal cancer, categorizing it as an "unfavorable" prognostic indicator [17].

Table 2: Prognostic Significance of GAPDH Overexpression in Specific Cancers

| Cancer Type | Overall Survival | Disease-Free Survival | Hazard Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) | P=2.1e−05 | N/A | Not specified |

| Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) | P=3e−04 | N/A | Not specified |

| Brain lower grade glioma (LGG) | P=1.7e−05 | P=0.003 | Not specified |

| Mesothelioma (MESO) | P=0.00061 | P=0.036 | Not specified |

| Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP) | N/A | P=0.0089 | Not specified |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD) | N/A | P=0.0081 | Not specified |

Molecular Mechanisms Underlying GAPDH Dysregulation in Cancer

The consistent overexpression of GAPDH in human cancers is driven by multiple genomic and epigenetic mechanisms that disrupt its normal regulatory controls.

Genetic Alterations and Copy Number Variations

Genetic alteration analyses reveal that the GAPDH gene is altered in approximately 2.1% (231/10,967) of queried TCGA tumor samples [14]. Notably, certain cancer types exhibit particularly high alteration frequencies, with seminoma showing greater than 6% alteration rate where "amplification" constitutes the primary genetic change [14]. Crucially, these genetic alterations directly impact expression levels, as samples with GAPDH copy number alterations demonstrate significantly increased mRNA expression compared to those without such changes [14]. Independent pan-cancer analyses confirm that DNA copy number amplification represents a fundamental mechanism driving GAPDH overexpression in human cancers [15].

Epigenetic Regulation and Transcriptional Control

DNA methylation status and transcription factor activity additionally contribute to GAPDH dysregulation. Multi-omics analyses indicate that GAPDH overexpression is regulated by promoter methylation modification, with hypomethylation potentially contributing to its increased transcription [15]. Furthermore, researchers have identified the transcription factor forkhead box M1 (FOXM1) as a key regulator of GAPDH expression [15]. FOXM1 itself functions as an oncogene and is ubiquitously highly expressed across multiple cancer types. Experimental validation through semi-quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation, quantitative PCR, and dual-luciferase assays confirmed that FOXM1 primarily binds to the promoter region of GAPDH in multiple cancer cell lines, directly activating its transcription [15].

Diagram 1: Molecular drivers of GAPDH overexpression in cancer

Functional Roles of GAPDH in Oncogenesis

Beyond its canonical glycolytic function, GAPDH participates in diverse molecular processes that directly contribute to tumor development and progression.

Metabolic Reprogramming and the Warburg Effect

Cancer cells preferentially utilize glycolysis for energy production even under aerobic conditions, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect [16]. As a key glycolytic enzyme, GAPDH is integral to this metabolic reprogramming. The heightened glycolytic flux in cancer cells demands increased expression of GAPDH to maintain accelerated glucose metabolism and support biomass production for rapid proliferation [15]. In lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), this metabolic switch enhances metastasis and cellular invasion through epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) signaling and angiogenesis [16]. Analysis of LUAD datasets confirms significant GAPDH upregulation (log2[FC]=1.130) that correlates with poor patient survival [16].

Modulation of Tumor Immune Microenvironment

GAPDH expression significantly correlates with altered immune infiltration patterns in the tumor microenvironment. Pan-cancer analyses demonstrate that GAPDH expression negatively correlates with immune infiltration involving cancer-associated fibroblasts, neutrophils, and endothelial cells [14]. Furthermore, GAPDH expression shows concordance with immune checkpoint gene expression, suggesting a potential association between GAPDH and the tumor immunological landscape [15]. These findings position GAPDH within the complex network of tumor-immune interactions that influence cancer development and therapeutic response.

Non-Metabolic Functions in Cancer Cells

GAPDH exhibits multiple glycolysis-independent functions that contribute to oncogenesis. Through its nitrosylase activity, GAPDH participates in nitrosylation of nuclear proteins and regulation of mRNA stability [14] [18]. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) reveals that GAPDH contributes to multiple important cancer-related pathways and biological processes beyond metabolism [15]. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) and post-translational modifications within intrinsically disordered regions of GAPDH can impact its structure, stability, and functionality, potentially influencing its role in tumorigenesis [16].

Experimental Validation and Case Studies

Reference Gene Stability in Cancer Models

Empirical investigations consistently demonstrate GAPDH instability across diverse cancer model systems. A comprehensive analysis of reference genes in dormant cancer cells revealed that pharmacological inhibition of mTOR kinase significantly rewires basic cellular functions and influences housekeeping gene expression [19]. While GAPDH was identified among the more stable reference genes in T98G cancer cells treated with dual mTOR inhibitors, its stability was cell line-dependent [19]. Similarly, in MCF-7 breast cancer cell line studies, GAPDH showed variable expression across sub-clones cultured under identical conditions over multiple passages [20]. Although GAPDH was initially identified as having low variation in one MCF-7 sub-clone, subsequent validation revealed it was unsuitable as a single internal control [20].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for validating reference genes

Methodological Considerations for Metastasis Research

The critical importance of appropriate GAPDH detection methodologies is exemplified in metastasis research. Human-specific GAPDH qRT-PCR enables quantification of human cancer cells within murine xenograft tissues without requiring overexpression of exogenous genes [21]. This approach demonstrates exceptional sensitivity, capable of detecting approximately 100 human cells in an entire mouse lung lobe (∼70 mg tissue) [21]. When directly compared to the gold-standard histological quantification of metastatic burden, human-specific GAPDH qRT-PCR showed strong correlation while offering superior sensitivity [21]. This methodology is particularly valuable for its applicability to diverse xenograft models without necessitating genetic modification of cancer cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for GAPDH and Reference Gene Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-specific GAPDH qPCR Primers [21] [22] | Quantification of human GAPDH in xenograft models | Forward: GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCGReverse: ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA [22] | Specifically detects human GAPDH in mouse tissue background |

| GAPDH Antibodies [17] | Protein expression analysis via IHC/Western blot | Clones: HPA040067, HPA061280, CAB005197, CAB016392, CAB079968 [17] | Consistent cytoplasmic and nuclear staining in most cancers |

| mTOR Inhibitors (e.g., AZD8055) [19] | Inducing cellular dormancy for reference gene validation | Dual mTORC1/2 inhibitor | Significantly alters expression of many housekeeping genes |

| Reference Gene Panels [19] [20] | Comprehensive normalization strategy | Includes 12+ candidate genes (e.g., ACTB, B2M, YWHAZ, TBP, RPL13A) | Enables identification of most stable genes for specific conditions |

| Bioinformatics Databases [14] [15] [17] | In silico expression and survival analysis | TIMER2, GEPIA2, UALCAN, cBioPortal, Human Protein Atlas | Provide pan-cancer expression data and prognostic correlations |

Best Practices for Reference Gene Selection in Cancer Research

Implementing Multi-Gene Normalization Strategies

Given the demonstrated instability of single reference genes like GAPDH, researchers should adopt multi-gene normalization strategies. Studies consistently show that normalization against a single reference gene is not recommended unless clear evidence of uniform expression dynamics is provided for specific experimental conditions [20]. For example, in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, the triplet combination of GAPDH-CCSER2-PCBP1 provided reliable normalization despite variability in individual gene expression [20]. Similarly, in cancer cells treated with mTOR inhibitors, optimal reference genes were cell line-dependent, with B2M and YWHAZ identified as most stable in A549 cells, while TUBA1A and GAPDH were optimal in T98G cells [19]. These findings underscore the necessity of empirically determining stable reference genes for each specific experimental system.

Experimental Framework for Reference Gene Validation

Researchers should implement the following methodological framework for robust reference gene validation:

- Select Multiple Candidate Genes: Choose 8-12 candidate reference genes representing diverse functional classes [19] [20].

- Assess Expression Stability: Evaluate candidate genes across all experimental conditions, treatments, and cell passages using appropriate statistical measures (e.g., coefficient of variation, geNorm algorithm) [20].

- Validate Selected Genes: Confirm the stability of selected reference genes by normalating target genes with known expression patterns [20].

- Utilize Bioinformatics Resources: Leverage public databases (TCGA, CPTAC, HPA) to assess potential dysregulation of candidate reference genes in specific cancer types [14] [15] [17].

The collective evidence from pan-cancer analyses unequivocally demonstrates that GAPDH is frequently overexpressed in human malignancies, associates with poor clinical outcomes, and participates in diverse oncogenic processes beyond its traditional metabolic functions. These findings fundamentally undermine its reliability as an internal control in cancer gene expression studies. Researchers must transition from the conventional practice of using GAPDH as a default reference gene toward rigorously validated, context-specific normalization strategies employing multiple stable reference genes. Adopting these robust experimental frameworks will enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of cancer research, particularly in studies investigating metabolic reprogramming, tumor progression, and therapeutic response.

Understanding How the Tumor Microenvironment (e.g., Hypoxia) Rewires Gene Expression

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex ecosystem characterized by numerous stress conditions, with hypoxia being a predominant feature that drives aggressive disease states. Hypoxia arises from the uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells that outpace the oxygen supply from existing vasculature, leading to regions of solid tumors with severely reduced oxygen tension [23] [24]. In response to hypoxia, cancer cells activate sophisticated molecular adaptations primarily orchestrated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), which function as master transcriptional regulators of the cellular response to oxygen deprivation [23] [4]. This hypoxic response triggers extensive rewiring of gene expression programs that influence key cancer hallmarks including metabolic reprogramming, angiogenesis, immune evasion, and therapy resistance [23] [24].

Understanding these dynamic transcriptional changes requires precise molecular techniques, with reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) emerging as the gold standard for quantifying gene expression dynamics. However, a critical yet often overlooked aspect of RT-qPCR experimental design is the selection of appropriate reference genes (RGs) for data normalization. Traditional "housekeeping" genes frequently used for normalization, such as those involved in glycolysis or cytoskeletal structure, are themselves transcriptionally regulated by hypoxia, potentially leading to inaccurate conclusions if used indiscriminately [3] [4]. This technical guide explores how the hypoxic TME reshapes gene expression while providing evidence-based frameworks for selecting robust reference genes in cancer studies, ensuring accurate interpretation of transcriptional data in this challenging context.

Molecular Mechanisms of Hypoxia-Induced Gene Expression

HIF-Dependent Transcriptional Regulation

The cellular response to hypoxia is predominantly mediated through the stabilization and activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α). Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is continuously synthesized but rapidly degraded by the proteasome following prolyl hydroxylation by oxygen-dependent enzymes. Under hypoxic conditions, this degradation is inhibited, leading to HIF-1α accumulation and translocation to the nucleus, where it forms a heterodimer with HIF-1β and binds to hypoxia response elements (HREs) in the promoter regions of target genes [4]. This HIF-mediated transcriptional program activates hundreds of genes involved in diverse cellular processes:

- Metabolic Reprogramming: HIF-1α directly upregulates glycolytic enzymes including hexokinase II (HKII) and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), shifting cellular metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis even in the presence of oxygen (the Warburg effect) [23].

- Angiogenesis: HIF-1α induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression, promoting the formation of new but often dysfunctional blood vessels that further contribute to the heterogeneous TME [24].

- pH Regulation: HIF-1α upregulates carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX), an enzyme that helps maintain intracellular pH amidst increased glycolytic flux [23].

Epigenetic Modifications in Hypoxia

Beyond direct transcriptional regulation, hypoxia induces profound epigenetic changes that further reshape gene expression patterns. The epigenetic reader ZMYND8 has been identified as a key mediator of hypoxia-induced gene expression, particularly in breast cancer. ZMYND8 expression is significantly elevated under hypoxic conditions and physically interacts with HIF-1α to co-activate HIF target genes [23]. This protein functions as a dual histone reader of H3.1K36me2/H4K16ac and regulates metabolic genes by promoting the recruitment of S5-phosphorylated RNA polymerase II to promoter regions, thereby enhancing transcription of genes like LDHA [23]. Through these epigenetic mechanisms, ZMYND8 bifurcates the metabolic axis toward anaerobic glycolysis, increasing extracellular acidification and contributing to the immunosuppressive TME by impacting CD8+ T cell activity [23].

Figure 1: HIF-1α Signaling Pathway in Normoxia and Hypoxia. Under normoxic conditions, prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes hydroxylate HIF-1α, targeting it for proteasomal degradation. During hypoxia, PHD activity is inhibited, leading to HIF-1α stabilization, nuclear translocation, heterodimerization with HIF-1β, and binding to hypoxia response elements (HREs) to activate transcription of genes involved in key cancer hallmarks [23] [4].

Methodological Considerations for Gene Expression Studies in Hypoxia

Experimental Models for Studying Hypoxia

To accurately investigate hypoxia-driven gene expression changes, researchers must employ appropriate experimental models that recapitulate features of the in vivo TME:

- In Vitro Hypoxia Chambers: Specialized incubators that maintain precise low oxygen tensions (typically 0.1-2% O₂) for cell culture, providing the most physiologically relevant in vitro hypoxia model [4].

- Chemical Hypoxia Mimetics: Compounds like cobalt chloride (CoCl₂) that stabilize HIF-1α by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylases under normoxic conditions, offering a convenient though less physiologically accurate alternative [5].

- 3D Multicellular Tumor Spheroids (MCTS): Scaffold-free 3D structures that spontaneously develop oxygen, nutrient, and proliferation gradients, mimicking the heterogeneous architecture of solid tumors more effectively than 2D cultures [23].

Comprehensive Workflow for Reference Gene Validation

Establishing reliable reference genes for RT-qPCR studies under hypoxic conditions requires a systematic, multi-step approach to ensure robust and reproducible results:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Reference Gene Validation. A systematic approach for identifying and validating stable reference genes under hypoxic conditions, encompassing candidate selection, experimental design, molecular workup, and multi-algorithm stability analysis [3] [5] [4].

Reference Gene Stability in Hypoxic Conditions

Pan-Cancer Analysis of Traditional Reference Genes

Extensive analysis across multiple cancer types and experimental conditions has revealed that many traditionally used reference genes exhibit significant expression variability under hypoxic conditions, rendering them unsuitable for normalization:

Table 1: Stability of Traditional Reference Genes in Hypoxic Conditions

| Reference Gene | Stability in Hypoxia | Expression Direction | Biological Function | Recommended Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Variable | Context-dependent [3] [4] [25] | Glycolytic enzyme | Pan-cancer platelets [25] |

| ACTB | Unstable | Decreased in mTOR inhibition [3] | Cytoskeletal structure | Not recommended |

| PGK1 | Unstable | HIF-target gene [4] | Glycolytic enzyme | Not recommended |

| TBP | Low expression | Variable [4] | Transcription factor | Not recommended |

| B2M | Stable | Stable in lung cancer [3] | Immune signaling | A549 cells [3] |

| YWHAZ | Stable | Stable in lung cancer [3] | Signal transduction | A549 cells [3] |

Validated Reference Genes for Hypoxia Studies

Recent systematic studies have identified more stable reference genes appropriate for hypoxia research in specific cancer types and experimental systems:

Table 2: Validated Stable Reference Genes for Hypoxia Studies

| Cancer Type/Cell Model | Recommended Reference Genes | Experimental Conditions | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer (Luminal A & TNBC) | RPLP1, RPL27 | Acute (8h) & chronic (48h) hypoxia at 1% O₂ [4] | RefFinder (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, ΔCt) |

| Glioblastoma (T98G cells) | TUBA1A, GAPDH | mTOR inhibition-induced stress [3] | Multiple algorithms |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma (A549 cells) | B2M, YWHAZ | mTOR inhibition-induced stress [3] | Multiple algorithms |

| PBMCs (Normoxia vs. Hypoxia) | RPL13A, S18, SDHA | 1% O₂ & chemical hypoxia [5] | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, ΔCt |

Technical Guidelines for Reliable Gene Expression Analysis

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

Proper RNA handling is fundamental for obtaining accurate RT-qPCR results, particularly under hypoxic conditions where RNA integrity may be compromised:

- Isolation Method: Use phenol/chloroform extraction with isopropanol precipitation for high-quality RNA recovery. Include GlycoBlue Coprecipitant to enhance nucleic acid yield during isolation [4].

- DNase Treatment: Treat all RNA samples with DNase I to eliminate contaminating genomic DNA that could cause false positive amplification [4].

- Quality Assessment: Determine RNA concentration and purity using spectrophotometry (NanoDrop), ensuring A260/A280 ratios between 1.8-2.0 and A260/A230 >2.0 [4] [25].

- Integrity Verification: Confirm RNA integrity using agarose gel electrophoresis or automated electrophoresis systems, looking for sharp ribosomal RNA bands without degradation smearing [4].

qPCR Experimental Design and Validation

Implement rigorous controls and validation steps to ensure technically sound and biologically meaningful results:

- Primer Validation: Confirm primer specificity through melt curve analysis (single peak) and agarose gel electrophoresis (single band of expected size) [5] [4].

- Efficiency Calculation: Generate standard curves using serial cDNA dilutions, with acceptable amplification efficiencies ranging from 90-110% and correlation coefficients (R²) >0.990 [5] [4].

- Experimental Replication: Include minimum three biological replicates (independent cultures) with three technical replicates each to account for both biological and technical variability [4].

- No-Template Controls: Include negative controls without template cDNA to detect potential contamination or primer-dimer formation [4].

Data Normalization and Analysis

- Multi-Gene Normalization: Use a combination of at least two validated reference genes, as this approach significantly improves normalization accuracy compared to single reference genes [5] [4].

- Stability Assessment: Employ multiple algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, ΔCt method) to comprehensively evaluate reference gene stability, then use RefFinder to generate a comprehensive ranking [5] [4].

- Data Interpretation: Normalize target gene expression to the geometric mean of validated reference genes using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method for relative quantification [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hypoxia and Gene Expression Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia Inducers | Cobalt Chloride (CoCl₂) [5] | Chemical hypoxia mimetic | Stabilizes HIF-1α by inhibiting PHDs under normoxia [5] |

| Hypoxia Chambers | InvivO₂ workstation [4] | Physiologic hypoxia modeling | Maintains precise low O₂ tensions (e.g., 1% O₂) [4] |

| RNA Isolation | QIAzol lysis reagent [4], TRIzol [25] | Total RNA extraction | Phenol/chloroform phase separation for high-quality RNA [4] |

| cDNA Synthesis | PrimeScript RT kit with gDNA eraser [25] | Reverse transcription | Includes DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination [25] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Bryt Green [5] | Fluorescent detection | DNA-binding dye for real-time PCR quantification [5] |

| Stability Algorithms | RefFinder [5] [4] | Reference gene validation | Integrates four algorithms for comprehensive stability assessment [5] [4] |

The hypoxic tumor microenvironment orchestrates extensive rewiring of gene expression through both HIF-dependent transcriptional programs and epigenetic mechanisms, fundamentally altering cancer cell behavior and therapeutic responses. Accurately quantifying these transcriptional changes requires rigorous methodological approaches, with particular attention to reference gene selection for RT-qPCR normalization. The evidence presented in this technical guide demonstrates that traditional reference genes are often unsuitable for hypoxia studies, while validating alternative genes that maintain stable expression under these challenging conditions. By implementing the standardized workflows, experimental models, and validated reference genes outlined herein, researchers can significantly improve the reliability and interpretability of gene expression data in hypoxia research, ultimately advancing our understanding of tumor biology and supporting the development of more effective cancer therapeutics.

In the field of cancer research, the reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) is a cornerstone technique for validating gene expression signatures that define molecular phenotypes of cells, tissues, and patient samples [1]. The accuracy of this powerful method, however, is entirely dependent on a critical methodological step: the use of stably expressed internal controls, known as reference genes (RGs) or housekeeping genes (HKGs), for data normalization [1]. The improper selection of these genes is not a minor technical oversight; it is a fundamental flaw that systematically distorts gene expression profiles and leads to unreliable biological conclusions. This guide details the consequences of poor reference gene selection and provides a validated roadmap for ensuring data integrity in cancer studies.

The Critical Role of Reference Genes in qPCR

RT-qPCR is renowned for its sensitivity, specificity, and ability to detect even low-abundance transcripts [26] [27]. However, this technique is susceptible to inconsistencies at various stages, including RNA extraction, sample storage, reverse transcription efficiency, and cDNA quality [26]. Normalization using reference genes is the most effective method to correct for these technical variations, thereby ensuring that observed changes in gene expression reflect true biology rather than experimental artifacts [26].

A reliable reference gene must be constitutively expressed at a constant level across all test conditions, tissue types, and developmental stages, and its expression should be unaffected by the experimental treatment [1]. Traditionally, researchers have used genes involved in basic cellular maintenance, such as GAPDH (glycolysis), ACTB (cytoskeleton), and 18S rRNA (ribosomal function), under the assumption that their expression is invariably stable [1]. A growing body of evidence, however, unequivocally demonstrates that this assumption is often false, particularly in the complex and dynamic context of cancer biology.

Documented Evidence of Data Distortion in Cancer Research

The consequences of selecting inappropriate reference genes have been quantitatively demonstrated across various cancer models. The following table summarizes key findings from recent studies:

Table 1: Documented Consequences of Poor Reference Gene Selection in Cancer Models

| Cancer Model | Experimental Condition | Unstable Reference Genes | Impact & Data Distortion | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Adenocarcinoma (A549), Glioblastoma (T98G), Ovarian Teratocarcinoma (PA-1) | Treatment with dual mTOR inhibitor (AZD8055) to induce dormancy | ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A | "Dramatic changes" in expression; "categorically inappropriate" for normalization. Incorrect selection led to "significant distortion of the gene expression profile". [3] | |

| Endometrial Cancer | General gene expression studies | GAPDH | GAPDH is a pan-cancer marker itself; its use is "unsuitable" and can be "held responsible for broad discrepancies in published results". [1] | |

| Breast Cancer Cell Lines (MCF-7, T-47D, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468) | Hypoxia (1% O₂) | GAPDH, PGK1 | Glycolytic genes are transcriptionally reprogrammed by hypoxia, rendering them redundant for normalization under this condition. [4] | |

| MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Line | Nutrient stress; sub-clone heterogeneity | ACTB, GAPDH, PGK1 as single controls | Use as a single internal control is not recommended. A triplet of genes (GAPDH-CCSER2-PCBP1) was required for reliable normalization across passages and conditions. [20] | |

| Cultured Human Odontoblasts | Expression of cannabinoid receptors | ACTB | "Significant differences were found in the relative expression levels... using the selected genes compared to those calculated using beta actin transcripts as references". [28] |

The diagram below illustrates the cascade of analytical errors that originates from the selection of an unstable reference gene, ultimately leading to false conclusions.

Methodological Framework for Robust Reference Gene Validation

To avoid the pitfalls described above, researchers must adopt a systematic, condition-specific approach to reference gene validation. The following workflow, endorsed by the MIQE guidelines, provides a robust framework.

Step 1: Selection of Candidate Reference Genes

Initiate the process by selecting a panel of candidate genes (typically between 10-12). These can include traditional genes and new candidates identified from RNA-sequencing data or literature reviews focused on your specific cancer type and experimental condition [3] [4].

Step 2: Experimental Design and RNA Extraction

- Biological Replicates: Include a sufficient number of biological replicates that accurately represent the variation in your study population [20].

- RNA Quality: Use high-quality, intact RNA. Assess purity using absorbance ratios (A260/A280 ~1.8-2.0) and integrity using appropriate methods [26].

Step 3: Reverse Transcription and qPCR Amplification

- Primer Design/Validation: Ensure primers have high amplification efficiency (90–110%) and specificity, confirmed by a single peak in melt curve analysis and a single band of the correct size on a gel [3] [27].

- qPCR Run: Perform reactions in technical replicates. The cycle threshold (Cq) values obtained are the raw data for stability analysis [27].

Step 4: Stability Analysis Using Multiple Algorithms

There is no single best method for evaluating stability. Therefore, it is essential to use multiple algorithms, each based on a different statistical principle, and then combine their results [29]. The most common tools are:

- geNorm: Calculates a stability measure (M) for each gene; lower M values indicate greater stability. It also determines the optimal number of reference genes by calculating the pairwise variation (V) between sequential normalization factors [29] [20].

- NormFinder: Evaluates intra-group and inter-group variation, making it particularly suited for experiments comparing different sample groups [29].

- BestKeeper: Relies on the standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) of the Cq values. Genes with a high SD and CV are considered unstable [29] [20].

- RefFinder: A web-based tool that integrates the results from geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the comparative Delta-Ct method to provide a comprehensive overall ranking [29] [30] [4].

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Reference Gene Validation

| Category | Item | Specific Function / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | High-Quality Total RNA | Starting material; integrity and purity are critical. [4] |

| DNase I Treatment | Removes contaminating genomic DNA. [4] | |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | For cDNA synthesis; can use oligo-dT or random primers. [25] | |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBR Green). [27] | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Primer Design Software | Ensures gene-specific amplification with high efficiency. [27] |

| Stability Analysis Algorithms | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper. [29] | |

| Comprehensive Ranking Tool | RefFinder aggregates results from multiple algorithms. [30] [4] | |

| Experimental Controls | Positive Control | cDNA known to express the target genes. |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | Checks for reagent contamination. |

Step 5: Final Validation

The ultimate test for your selected reference gene(s) is to normalize a well-characterized target gene of interest. If the normalized expression profile aligns with expected results based on literature or other validated methods, the reference gene panel is considered fit for purpose [29].

The entire workflow, from candidate selection to final validation, is summarized below.

In cancer research, where accurate gene expression data can inform diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets, the selection of reference genes must be elevated from a assumed technicality to a central, validated component of experimental design. As evidenced by studies across cancer types, the uncritical use of traditional housekeeping genes like GAPDH and ACTB is a significant source of error and irreproducibility. By implementing the rigorous, multi-step validation framework outlined in this guide—which mandates the use of multiple candidate genes and statistical algorithms—researchers can safeguard their data against distortion. This disciplined approach ensures that scientific conclusions about oncogenesis, treatment response, and resistance are built upon a foundation of reliable and accurate gene expression measurement.

A Step-by-Step Workflow for Identifying and Applying Stable Reference Genes

In cancer research, quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) serves as a cornerstone technique for validating gene expression patterns discovered through high-throughput transcriptomic analyses. Accurate and reliable RT-qPCR data, however, is critically dependent on proper normalization using stable reference genes, also known as endogenous controls [31] [26]. These genes are used to correct for variations in sample quantity, RNA quality, and enzymatic efficiencies during the reverse transcription and PCR processes [31]. The selection of inappropriate reference genes that vary under experimental conditions can lead to significant distortion of gene expression profiles and erroneous biological conclusions [3] [26]. This guide details a robust, evidence-based methodology for selecting candidate reference genes by leveraging RNA-seq data and existing literature, forming the essential first step in establishing a reliable qPCR workflow for cancer studies.

Mining RNA-seq Data for Stable Candidate Genes

RNA sequencing provides a genome-wide, unbiased view of transcript abundance, making it an ideal starting point for identifying genes with stable expression across your specific cancer model and experimental conditions.

Establishing Selection Criteria from RNA-seq Data

When processing RNA-seq data (e.g., from public repositories like GEO), apply the following bioinformatics filters to shortlist candidate reference genes with inherently stable expression [32]:

- Fold-Change Threshold: Select genes where the ratio of mean expression in control versus test groups (e.g., tumor vs. normal) is less than a defined cutoff. A common standard is mean(normal)/mean(tumor) < 1.2 and mean(tumor)/mean(normal) < 1.2 [32]. This ensures the gene's expression is not significantly altered by the cancerous state.

- High Abundance Filter: Retain genes within the top 10% of mean expression in both normal and tumor sample groups [32]. Highly expressed genes are preferable for RT-qPCR as they yield lower, more reliable Cq values.

- Low Variability Filter: Include genes with a Coefficient of Variation (CV) < 10% in both normal and tumor samples, where CV = standard deviation/mean [32]. This statistical measure identifies genes with minimal expression fluctuation across biological replicates.

Table 1: Bioinformatics Filters for Candidate Gene Selection from RNA-seq Data

| Filter Name | Calculation | Target Threshold | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fold-Change | MAX(Mean_A, Mean_B) / MIN(Mean_A, Mean_B) |

< 1.2 | Ensures expression is unaffected by experimental condition. |

| High Abundance | Percentile rank of mean expression | Top 10% | Identifies genes suitable for sensitive RT-qPCR detection. |

| Low Variability | Standard Deviation / Mean |

< 10% | Selects genes with consistent expression across replicates. |

A Practical Workflow for Data Analysis

A published pan-cancer study on platelets demonstrates this approach. Researchers analyzed the GSE68086 dataset, containing RNA-seq data from six different cancers. After standard quality control and read alignment, they applied the filters in Table 1 to a list of 73 known reference genes, narrowing the field to 7 high-confidence candidates (YWHAZ, GNAS, GAPDH, OAZ1, PTMA, B2M, and ACTB) for further experimental validation [32].

Leveraging Existing Scientific Literature

Concurrently with RNA-seq analysis, a thorough review of the literature is indispensable for understanding which genes have proven stable in similar cancer contexts and for avoiding commonly used but unstable genes.

Context-Dependent Instability of Common Reference Genes

A critical finding from recent cancer research is that classic "housekeeping" genes are often unreliable in specific experimental settings. For instance, a 2025 study on dormant cancer cells found that ACTB (cytoskeleton) and ribosomal genes RPS23, RPS18, and RPL13A undergo "dramatic changes" in expression following mTOR inhibition and are "categorically inappropriate" for normalization in that context [3]. Similarly, in studies of hypoxic breast cancer, glycolytic enzymes like GAPDH and PGK1 are unsuitable because their expression is directly upregulated by hypoxia, a common feature of the tumor microenvironment [4].

Compiling and Assessing Literature-Based Candidates

When reviewing literature, create a table to synthesize findings. The table below summarizes insights from recent cancer studies.

Table 2: Reference Gene Stability in Specific Cancer Contexts from Literature

| Cancer / Experimental Context | Recommended Stable Genes | Genes to Avoid (Unstable) | Key Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dormant Cancer Cells (mTOR inhibition) | A549 cells: B2M, YWHAZT98G cells: TUBA1A, GAPDH | ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A | [3] |

| Hypoxic Breast Cancer Cells | RPLP1, RPL27 | GAPDH, PGK1 | [4] |

| Pan-Cancer (Platelets) | GAPDH | (Varies by cancer type) | [32] |

Generating a Final Candidate List for Validation

The final candidate list is generated by integrating results from your RNA-seq analysis and literature review.

The Integration Workflow

This process involves cross-referencing and prioritizing genes that appear stable in both your own data and external studies.

A Sample Candidate List for General Cancer qPCR

Based on the synthesis of the provided sources, a robust starting panel of 8-12 candidate genes should include a diverse set of functional classes to increase the likelihood of finding stable genes. The following table provides a template.

Table 3: Sample Panel of Candidate Reference Genes for Cancer Studies

| Gene Symbol | Full Name | Primary Function | Notes on Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| YWHAZ | Tyrosine 3-Monooxygenase/Tryptophan 5-Monooxygenase Activation Protein Zeta | Signal transduction, cell cycle regulation | Often stable across diverse contexts; recommended for A549 cells [3] and pan-cancer platelets [32]. |

| B2M | Beta-2-Microglobulin | Component of MHC class I molecules | Recommended for A549 dormant cells [3]. |

| RPLP1 | Ribosomal Protein Lateral Stalk Subunit P1 | Ribosomal protein, translation | Identified as optimal in hypoxic breast cancer [4]. |

| RPL27 | Ribosomal Protein L27 | Ribosomal protein, translation | Optimal in combination with RPLP1 in hypoxic breast cancer [4]. |

| TBP | TATA-Box Binding Protein | Transcription initiation factor | Often stable; identified as best for lotus rootstocks and flowers [33]. |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase | Glycolytic enzyme | Context-dependent. Stable in T98G cells [3] and pan-cancer platelets [32], but unstable under hypoxia [4] and mTOR inhibition [3]. |

| ACTB | Beta-Actin | Cytoskeletal structural protein | Frequently unstable. Avoid in mTOR-inhibited cells [3] and use with caution generally. |

| PGK1 | Phosphoglycerate Kinase 1 | Glycolytic enzyme | Context-dependent. Explicitly unstable under hypoxia [4]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Candidate Gene Selection and Validation