Benchmarking Virtual Screening for Breast Cancer Subtypes: Methods, Challenges, and AI-Driven Advances

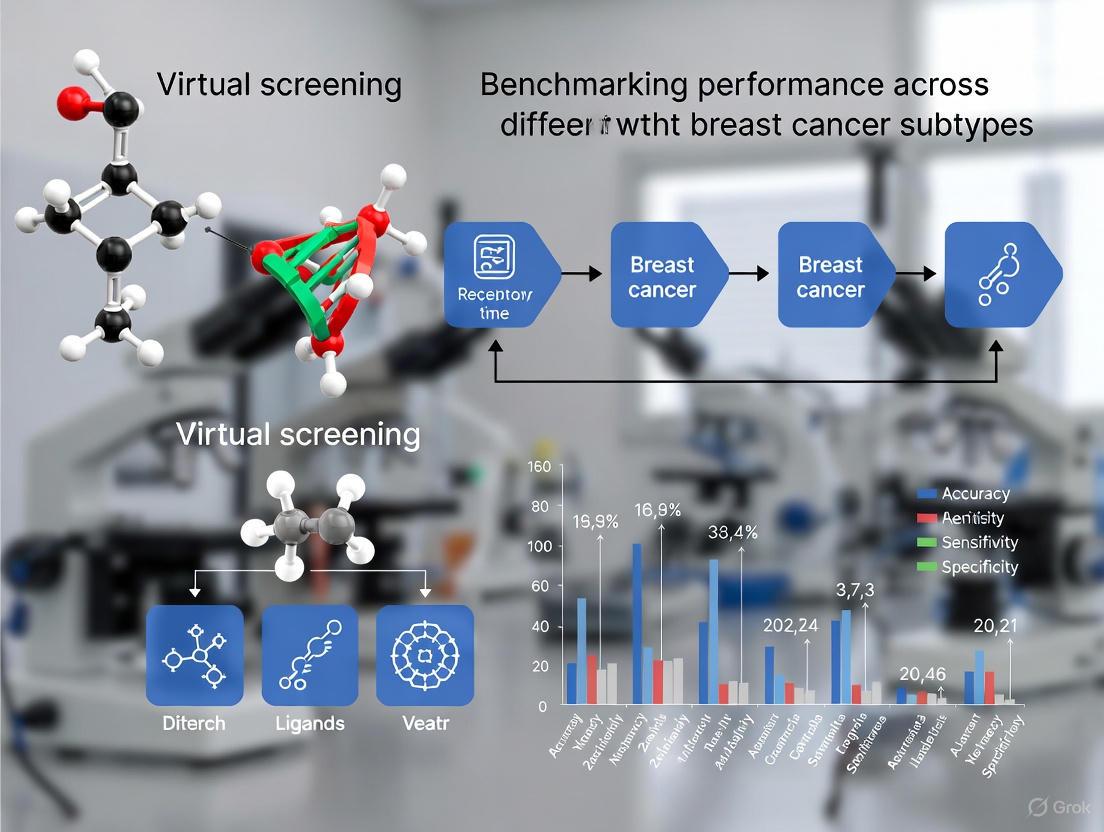

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of benchmarking virtual screening (VS) performance across the major molecular subtypes of breast cancer—Luminal, HER2-positive, and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC).

Benchmarking Virtual Screening for Breast Cancer Subtypes: Methods, Challenges, and AI-Driven Advances

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of benchmarking virtual screening (VS) performance across the major molecular subtypes of breast cancer—Luminal, HER2-positive, and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC). It explores the foundational need for subtype-specific VS strategies due to distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities and target landscapes. The content details the application of core computational methodologies, including molecular docking, pharmacophore modeling, AI-accelerated platforms, and molecular dynamics, highlighting their use in discovering subtype-specific inhibitors. Significant challenges such as tumor heterogeneity, data leakage in benchmarks, and scoring function inaccuracies are addressed, alongside optimization strategies like flexible receptor docking and active learning. The article further examines validation protocols, from retrospective benchmarks like DUD and CASF to experimental confirmation via X-ray crystallography and cell-based assays. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current best practices and future directions for developing more precise and effective computational drug discovery pipelines in oncology.

The Imperative for Subtype-Specific Virtual Screening in Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is not a single disease but a collection of malignancies with distinct molecular features, clinical behaviors, and therapeutic responses. This heterogeneity has profound implications for prognosis and treatment selection, necessitating robust classification systems that guide clinical decision-making and drug development. The most widely recognized framework categorizes breast cancer into four principal molecular subtypes—Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-positive (HER2-enriched), and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)—based on the expression of hormone receptors (estrogen receptor [ER] and progesterone receptor [PR]), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and the proliferation marker Ki-67 [1] [2] [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these subtypes, detailing their pathological characteristics, associated signaling pathways, and standard treatment modalities. Furthermore, it situates this biological overview within the context of modern computational drug discovery, illustrating how virtual screening and computer-aided drug design (CADD) are being leveraged to target subtype-specific vulnerabilities.

Molecular and Clinical Characteristics of Breast Cancer Subtypes

The classification of breast cancer into intrinsic molecular subtypes has revolutionized both prognostic assessment and therapeutic strategies. The table below summarizes the defining Pathological and Clinical Characteristics of each major subtype.

Table 1: Pathological and Clinical Characteristics of Major Breast Cancer Subtypes

| Characteristic | Luminal A | Luminal B | HER2-Positive | Triple-Negative (TNBC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER Status | Positive [1] [2] | Positive (often lower levels) [1] [3] | Usually Negative [1] [4] | Negative [1] [5] |

| PR Status | Positive [1] [2] | Negative or Low [1] [2] | Negative [1] | Negative [1] [5] |

| HER2 Status | Negative [1] [2] | Positive or Negative [2] [3] | Positive (Overexpression/Amplification) [1] [4] | Negative [1] [5] |

| Ki-67 Level | Low (<20%) [1] | High (≥20%) [1] | Variable, often high [1] | High [2] [5] |

| Approx. Prevalence | 50-60% [2] [3] | 15-20% [2] [3] | 10-15% [1] [2] | 10-20% [1] [3] |

| Common Treatments | Endocrine Therapy (e.g., Tamoxifen, AIs) [1] [6] | Endocrine Therapy + Chemotherapy ± Anti-HER2 [1] [3] | Chemotherapy + Anti-HER2 Therapy (e.g., Trastuzumab) [1] [2] | Chemotherapy ± Immunotherapy [6] [5] |

| Prognosis | Best prognosis [1] [2] | Intermediate prognosis [1] [3] | Good prognosis with targeted therapy [2] [4] | Poor prognosis, more aggressive [1] [5] |

Subtype-Specific Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Targets

The clinical behavior of each subtype is driven by distinct underlying molecular pathways. Targeting these pathways is the cornerstone of precision oncology in breast cancer. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and associated targeted therapies for the major subtypes.

Computational Approaches for Subtype-Specific Drug Discovery

The heterogeneity of breast cancer demands tailored therapeutic development. Computational methods, particularly virtual screening and computer-aided drug design (CADD), have emerged as powerful tools for efficiently identifying and optimizing subtype-specific drugs.

Key Methodologies and Workflows

Virtual screening employs structure-based or ligand-based approaches to computationally screen large libraries of compounds for potential activity against a specific target [6] [7]. A standard structure-based workflow for identifying novel HER2 inhibitors, as exemplified by a study screening natural products, is outlined below [8].

Table 2: Key Virtual Screening and CADD Methodologies

| Method Category | Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Virtual Screening | Docking compounds from large libraries into the 3D structure of a target protein to predict binding affinity and pose [8] [7]. | Screening 638,960 natural products against the HER2 tyrosine kinase domain [8]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to assess the stability of protein-ligand complexes and refine binding models [8] [7]. | Validating the binding stability of the natural product liquiritin to HER2 [8]. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Identifying the essential 3D arrangement of molecular features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions) necessary for biological activity [7]. | Used in CADD campaigns for luminal breast cancer to design novel ER-targeting agents [7]. |

| AI/Machine Learning in Drug Design | Using predictive models to triage chemical space, forecast drug-target interactions, and optimize pharmacokinetic properties [6] [7]. | Predicting novel drug candidates and biomarkers by integrating multi-omics data across breast cancer subtypes [6]. |

Successful execution of computational and experimental research on breast cancer subtypes relies on a suite of key reagents, databases, and software tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Breast Cancer Subtype Research

| Resource Category | Specific Example | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Database | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of 3D protein structures (e.g., PDB ID 3RCD for HER2) for structure-based virtual screening and molecular docking [8]. |

| Compound Libraries | COCONUT, ZINC Natural Products | Large-scale, commercially available libraries of small molecules or natural products used for virtual screening campaigns [8]. |

| Computational Software | Schrödinger Suite (Maestro) | Integrated software platform for protein preparation (Protein Prep Wizard), molecular docking (Glide), and ADMET prediction (QikProp) [8] [7]. |

| Cell Line Models | HER2+ Cell Lines (e.g., SK-BR-3) | Preclinical in vitro models representing specific subtypes (e.g., HER2-overexpressing) for validating the anti-proliferative effects of computationally identified hits [8]. |

| Clinical Biomarker Assays | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for ER, PR, HER2, Ki-67 | Standard clinical methods for defining breast cancer subtypes by measuring protein expression levels in tumor tissue [1] [5]. |

Benchmarking Virtual Screening Performance Across Subtypes

The application and performance of virtual screening can vary significantly across different breast cancer subtypes, primarily due to differences in target availability and characterization.

Subtype-Specific CADD Applications and Experimental Protocols

Luminal A & B (ER-Positive): The primary target is the estrogen receptor (ER). CADD efforts have been highly successful in developing Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) and Degraders (SERDs). A common protocol involves docking compounds into the ligand-binding domain of ERα to identify novel antagonists or degraders. For instance, virtual screening of colchicine-based compounds followed by Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) calculations identified candidates with higher predicted binding affinity than tamoxifen [9] [7]. Subsequent molecular dynamics simulations (e.g., 100-200 ns) are used to confirm the thermodynamic stability of the ligand-ER complex [9].

HER2-Positive (HER2-Enriched): The HER2 tyrosine kinase is a well-defined, druggable target. The standard protocol, as detailed in a study discovering natural HER2 inhibitors, involves a hierarchical docking workflow [8]. First, a large compound library is screened using High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS). Top hits are refined with Standard Precision (SP) docking, and the best are subjected to more computationally intensive Extra Precision (XP) docking. The final top-ranking compounds undergo molecular dynamics simulations (e.g., 100 ns) to validate binding mode stability, followed by MM-GBSA calculations to estimate binding free energy [8]. Successful hits are then tested in biochemical kinase inhibition assays and cellular proliferation assays using HER2-overexpressing cell lines.

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC): The lack of classic targets makes TNBC a challenge. Research often focuses on targeting non-classical vulnerabilities, such as:

- Androgen Receptor (AR) in the LAR subtype: Using virtual screening to identify AR antagonists [5] [7].

- DNA Damage Response Pathways: Targeting BRCAness and homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) with PARP inhibitors, which can be identified and optimized using CADD [5] [7].

- Immunomodulatory Targets: AI and network-based methods analyze multi-omics data to identify immune checkpoints or other immunomodulatory targets for combination therapies [6] [5]. The experimental protocol often includes network pharmacology to map compound-gene-disease interactions, followed by validation in TNBC cell line panels representing different transcriptomic subsets (e.g., basal-like 1, mesenchymal, LAR) [5].

Comparative Analysis of Computational Challenges

Table 4: Benchmarking Virtual Screening Across Breast Cancer Subtypes

| Subtype | Prominent CADD Targets | Strengths of CADD Approach | Key Challenges & Research Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal (A/B) | Estrogen Receptor (ERα), CDK4/6, ESR1 mutants [7]. | Well-characterized, structured ligand-binding domain highly amenable to docking; Success in developing clinical-grade SERDs [9] [7]. | Overcoming therapy resistance due to ESR1 mutations and pathway rewiring requires modeling receptor plasticity [7]. |

| HER2-Positive | HER2 Tyrosine Kinase domain, extracellular domain [8] [4]. | High-resolution crystal structures available; Clear definition of ATP-binding site enables successful structure-based screening [8] [7]. | Tumor heterogeneity and brain metastases; Need for inhibitors overcoming resistance via alternative pathways (e.g., PI3K) [4] [7]. |

| TNBC | AR (LAR), PARP1/2, PI3K, PD-L1, various kinases [5] [7]. | Opportunity for novel target discovery; Network-based and AI methods can uncover hidden vulnerabilities from multi-omics data [6] [5]. | Target scarcity and high heterogeneity; Lack of a single dominant driver complicates target selection; Limited clinical success of candidates [5] [7]. |

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide, with therapeutic resistance representing a fundamental barrier to improving patient outcomes [10] [11]. Despite significant advances in targeted therapies and treatment modalities, resistance mechanisms enable cancer cells to evade destruction, leading to disease progression and recurrence [12]. This challenge is particularly acute in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), where target scarcity—the lack of defined molecular targets such as hormone receptors or HER2—severely limits treatment options [10] [7]. The complex interplay of genetic, epigenetic, metabolic, and microenvironmental factors drives resistance through dynamic adaptations that allow cancer cells to survive therapeutic assaults [13] [11].

Computational approaches, particularly virtual screening and artificial intelligence (AI), have emerged as powerful strategies to address these challenges [7] [11]. By leveraging molecular modeling, machine learning, and multi-omics data integration, researchers can identify novel therapeutic vulnerabilities and predict resistance mechanisms before they manifest clinically [14] [7]. This review benchmarks current computational methodologies across breast cancer subtypes, evaluating their performance in overcoming resistance and identifying new targets in traditionally challenging contexts like TNBC.

Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance Across Breast Cancer Subtypes

Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations

Therapeutic resistance in breast cancer arises through complex genetic and epigenetic reprogramming. Key driver mutations include ESR1 mutations in luminal subtypes, which confer resistance to endocrine therapies by enabling ligand-independent activation of estrogen receptor signaling [15] [7]. In HER2-positive disease, PIK3CA mutations activate alternative signaling pathways that bypass HER2 blockade, while TNBC frequently exhibits TP53 mutations and germline BRCA deficiencies that promote genomic instability and adaptive resistance [14] [10] [7]. Beyond genetic changes, epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation, histone alterations, and non-coding RNA dysregulation reprogram gene expression patterns to support survival under therapeutic pressure [12].

Cancer Stem Cells and Tumor Microenvironment

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a functionally resilient subpopulation capable of driving tumor initiation, progression, and therapy resistance [13]. These cells demonstrate enhanced DNA repair capacity, efficient drug efflux mechanisms, and metabolic plasticity that collectively enable survival after conventional treatments [13]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) further reinforces resistance through stromal cell interactions, immune evasion, and metabolic symbiosis [10] [16]. Nutrient competition, hypoxia-driven signaling, and lactate accumulation within the TME create protective niches that shield resistant cells from therapeutic effects [16] [11].

Metabolic Reprogramming

Metabolic adaptation represents a cornerstone of resistance across breast cancer subtypes [16]. Hormone receptor-positive tumors exhibit dependencies on fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis, while HER2-positive cancers leverage enhanced glycolytic flux and HER2-mediated metabolic signaling [16]. TNBC demonstrates remarkable metabolic plasticity, dynamically shifting between glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and glutamine metabolism to survive under diverse conditions [13] [16]. These subtype-specific metabolic dependencies represent promising therapeutic targets for overcoming resistance.

Computational Strategies for Overcoming Resistance

Virtual Screening and Computer-Aided Drug Design

Computer-aided drug design (CADD) has emerged as a transformative approach for addressing resistance across breast cancer subtypes [7]. Structure-based methods including molecular docking, virtual screening, and molecular dynamics simulations enable rational drug design against resistance-conferring mutations [7]. For luminal breast cancer, CADD has facilitated development of next-generation selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) effective against ESR1-mutant tumors [7]. In HER2-positive disease, computational approaches guide antibody engineering and kinase inhibitor optimization to overcome pathway reactivation [7]. For TNBC, virtual screening identifies compounds targeting DNA repair pathways and epigenetic regulators to address target scarcity [7].

AI-enabled workflows represent a recent advancement, with deep learning models rapidly triaging chemical space while physics-based simulations provide mechanistic validation [7]. Generative models propose novel chemical entities aligned with pharmacological requirements, feeding candidates into refinement loops for optimized therapeutic efficacy [7].

Deep Learning for Diagnostic and Predictive Biomarkers

Deep learning approaches applied to medical imaging and digital pathology demonstrate growing capability for non-invasive resistance prediction [17] [18]. The DenseNet121-CBAM model achieves area under curve (AUC) values of 0.759 for distinguishing Luminal versus non-Luminal subtypes and 0.668 for identifying triple-negative breast cancer directly from mammography images [17]. For multiclass classification across five molecular subtypes, the system shows superior performance in detecting HER2+/HR− (AUC = 0.78) and triple-negative (AUC = 0.72) subtypes [17]. These imaging-based predictors offer non-invasive alternatives to biopsy for monitoring tumor evolution and detecting emerging resistance.

Virtual staining represents another computational breakthrough, using deep generative models to create immunohistochemistry (IHC) images directly from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained samples [18]. This approach preserves tissue specimens while reducing turnaround time and resource requirements for biomarker assessment [18]. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) and contrastive learning approaches have demonstrated particular effectiveness for this image-to-image translation task [18].

Liquid Biopsy and Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis

Liquid biopsy approaches leveraging circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) enable real-time monitoring of resistance evolution [14] [15]. The SERENA-6 trial demonstrated that ctDNA analysis can detect emerging ESR1 mutations in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer months before standard imaging shows progression [15]. This early detection enables timely intervention with targeted therapies like camizestrant, potentially delaying resistance emergence [15]. In TNBC, the PREDICT-DNA trial established that ctDNA-negative status after neoadjuvant therapy correlates with excellent prognosis, suggesting utility for risk stratification and adjuvant therapy guidance [15].

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Computational Methods Across Breast Cancer Subtypes

| Method Category | Specific Approach | Luminal Performance | HER2+ Performance | TNBC Performance | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning Imaging | DenseNet121-CBAM (Mammography) | AUC: 0.759 (Luminal vs non-Luminal) | AUC: 0.658 (HER2 status) | AUC: 0.668 (TN vs non-TN) | Molecular subtype prediction |

| Virtual Staining | H&E to IHC Translation | High accuracy for ER/PR prediction | HER2 virtual staining under validation | Emerging for Ki-67 assessment | Biomarker preservation |

| Liquid Biopsy | ctDNA mutation detection | ESR1 mutations: 5.3 months lead time | HER2 mutations: Detectable pre-progression | Limited validation | Early resistance detection |

| CADD | Molecular docking & dynamics | SERDs development (elacestrant, camizestrant) | HER2 degraders & kinase inhibitors | PARP inhibitors & novel targets | Overcoming target scarcity |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Deep Learning Model Development for Subtype Prediction

The DenseNet121-CBAM architecture provides a validated protocol for predicting molecular subtypes from mammography images [17]. This approach integrates Convolutional Block Attention Modules (CBAM) with DenseNet121 backbone for enhanced feature extraction [17].

Data Preprocessing Workflow:

- Image Acquisition: Full-field digital mammography images acquired with spatial resolution of 7 lp/mm, stored in DICOM format [17]

- Region of Interest Annotation: Two qualified radiologists independently annotate tumor areas using ITK-SNAP software, with inter-observer variability assessment [17]

- ROI Expansion: Annotated tumor regions expanded outward by specified pixel values to capture peritumoral features, then resized to square dimensions (224×224 pixels) [17]

- Class Imbalance Handling: Simple random oversampling applied with subtype-specific rates (Luminal: 1.3×, TNBC: 1.7×, HER2: 1.5×) [17]

- Data Augmentation: Geometric transformations including random horizontal flipping (50% probability), vertical flipping (50% probability), random rotation (±20°), and horizontal shearing (±10°) [17]

Model Architecture Details:

- Backbone Selection: DenseNet121 selected through comparative analysis of multiple CNN architectures (Simple CNN, ResNet101, MobileNetV2, ViT-B/16) [17]

- Channel Adaptation: Pretrained ImageNet weights adapted to single-channel mammography images by averaging across three input channels [17]

- Attention Mechanism: CBAM modules integrated to enhance feature discriminability, with Grad-CAM visualization for interpretability [17]

- Training Protocol: Five-fold cross-validation with binary (Luminal vs non-Luminal, HER2-positive vs negative, TN vs non-TN) and multiclass classification tasks [17]

Virtual Staining Implementation

Virtual staining techniques generate immunohistochemistry images directly from H&E-stained tissue sections using deep generative models [18].

Benchmarking Framework:

- Model Architectures: CycleGAN, conditional GAN, and contrastive unpaired translation (CUT) models evaluated on public datasets [18]

- Performance Metrics: Structural similarity index measure (SSIM), peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), and Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) for image quality assessment [18]

- Clinical Validation: Concordance with ground truth IHC staining assessed for ER, PR, HER2, and Ki-67 biomarkers [18]

- Dataset Requirements: Training typically requires paired H&E and IHC whole slide images from consecutive tissue sections [18]

Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis Protocol

Liquid biopsy methodologies enable detection of resistance mutations in real-time [15].

SERENA-6 Trial Methodology:

- Blood Collection: Serial blood samples collected at baseline and every 4-8 weeks during treatment [15]

- ctDNA Extraction: Plasma separation followed by cell-free DNA extraction using commercial kits [15]

- Mutation Detection: Next-generation sequencing panels targeting known resistance mutations (ESR1, PIK3CA, etc.) with high sensitivity (0.1% variant allele frequency) [15]

- Intervention Threshold: Protocol-specified therapy switch upon detection of emerging ESR1 mutations with clinical correlation [15]

Signaling Pathways in Breast Cancer Resistance

The following diagram illustrates key resistance pathways and their interactions across breast cancer subtypes, highlighting potential intervention points for computational targeting.

Breast Cancer Resistance Signaling Network: This diagram illustrates key molecular pathways contributing to therapy resistance across breast cancer subtypes, highlighting potential targets for computational intervention.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Breast Cancer Resistance Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/Platform | Primary Research Application | Subtype Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Panels | MD Anderson Breast Cancer Cell Panel, ATCC Breast Cancer Portfolio | In vitro drug screening & resistance modeling | All subtypes (Luminal, HER2+, TNBC) |

| ctDNA Detection Kits | MSK-ACCESS, Guardant360, FoundationOne Liquid CDx | Liquid biopsy analysis for resistance mutation detection | Luminal (ESR1), HER2+ (PIK3CA), TNBC (TP53) |

| IHC Antibodies | ER (SP1), PR (1E2), HER2 (4B5), Ki-67 (30-9) | Biomarker validation & molecular subtyping | Subtype-defining markers |

| Virtual Staining Datasets | TCGA-BRCA, Camelyon17, Internal institutional datasets | Training & validation of generative models | All subtypes |

| CADD Software | AutoDock, Schrödinger Suite, OpenEye Toolkits | Molecular docking & dynamics simulations | Target-specific applications |

| AI/ML Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, MONAI for medical imaging | Development of predictive models for resistance | Subtype-agnostic |

| 3D Culture Systems | Matrigel, Organoid culture media | Tumor microenvironment modeling & CSC studies | All subtypes |

| Animal Models | PDX collections (Jackson Laboratory, EurOPDX) | In vivo validation of resistance mechanisms | Subtype-characterized models |

The growing arsenal of computational approaches for addressing breast cancer resistance demonstrates promising performance across subtypes, though significant challenges remain [7] [11]. Virtual screening and AI-driven drug design show particular potential for overcoming target scarcity in TNBC by identifying novel vulnerabilities [7]. Deep learning applications in medical imaging enable non-invasive resistance monitoring, while liquid biopsy approaches provide real-time molecular intelligence on evolving tumor dynamics [17] [15].

Future progress will require enhanced integration of multi-omics data, refined in silico models of tumor heterogeneity, and robust validation through prospective clinical trials [7]. The convergence of computational prediction with experimental validation offers a pathway toward personalized therapeutic strategies that proactively address resistance mechanisms rather than reacting to their emergence [14]. As these technologies mature, they hold potential to transform breast cancer management by anticipating resistance and deploying countermeasures before treatment failure occurs.

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) as a Strategic Response

Breast cancer is a highly heterogeneous malignancy with distinct molecular subtypes—Luminal, HER2-positive (HER2+), and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)—each presenting unique therapeutic challenges and vulnerabilities [19]. This molecular diversity complicates the development of effective therapies, as traditional drug discovery methods face constraints from high costs and extended development timelines [19]. Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) has emerged as a transformative strategy to accelerate therapeutic discovery by leveraging computational power to identify and optimize drug candidates with enhanced precision [19]. CADD integrates a suite of computational techniques, including molecular docking, virtual screening (VS), pharmacophore modeling, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enabling researchers to efficiently explore chemical space and predict drug-target interactions [19] [20]. The strategic application of CADD is particularly valuable for developing subtype-specific therapies, overcoming drug resistance mechanisms, and streamlining the drug discovery pipeline from initial target identification to lead optimization [19].

Benchmarking Virtual Screening Performance: A Subtype-Centric Analysis

Virtual screening (VS) stands as a cornerstone technique within CADD, functioning as a computational counterpart to experimental high-throughput screening [21]. Its performance is critical for the efficient identification of hit compounds. Benchmarking studies reveal that VS effectiveness varies considerably across breast cancer subtypes due to their distinct molecular pathologies and target characteristics. The integration of multiple computational techniques significantly enhances VS outcomes, with structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) emerging as the most prominently used approach, accounting for an average of 57.6% of applications [21].

Table 1: Benchmarking Virtual Screening Software Preferences and Performance

| Software/Resource | Average Usage % | Primary Application | Notable Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock | 41.8% | Structure-based Virtual Screening, Molecular Docking | Open-source; well-validated; extensive community support [21] |

| ZINC Database | 31.2% | Compound Library Source | Extensive catalog of commercially available compounds [21] |

| GROMACS | 39.3% | Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Open-source; high performance for biomolecular systems [21] |

| AlphaFold | N/A | Protein Structure Prediction | High-accuracy predictions when experimental structures unavailable [19] |

The selection of specific VS protocols is often guided by the target class prevalent in each breast cancer subtype. For instance, in Luminal cancers targeting the Estrogen Receptor (ER), VS workflows frequently incorporate pharmacophore modeling and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) analyses to identify novel Selective Estrogen Receptor Degraders (SERDs) [19]. For HER2+ subtypes, structure-based approaches leveraging high-resolution HER2 kinase domain structures enable the optimization of selective inhibitors and antibody-drug conjugates [19]. The particularly challenging TNBC subtype, characterized by a scarcity of well-defined targets, often benefits from hybrid workflows that combine ligand-based screening for targets like PARP with structure-based methods for emerging targets in DNA repair pathways [19].

Table 2: Subtype-Specific Virtual Screening Applications and Outcomes

| Breast Cancer Subtype | Primary Targets | Preferred VS Approaches | Representative Successes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal (ER/PR+) | Estrogen Receptor (ESR1) | SBVS, Pharmacophore Modeling, QSAR | Next-generation oral SERDs (elacestrant, camizestrant) [19] |

| HER2-Positive | HER2 receptor, kinase domain | SBVS, Molecular Docking, MD Simulations | Optimized kinase inhibitors, antibody engineering [19] |

| Triple-Negative (TNBC) | PARP, epigenetic regulators, immune checkpoints | Hybrid Screening, Multi-omics Guided VS | PARP inhibitors, immune modulators [19] |

Post-docking refinement through Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations has become a standard practice for validating VS results, employed in approximately 38.5% of studies [21]. This step is crucial for assessing binding stability, accounting for protein flexibility, and calculating more reliable binding free energies, thereby reducing false positives identified from docking alone [21].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking CADD Performance

Standard Protocol for Structure-Based Virtual Screening

A robust, benchmarked workflow for SBVS integrates multiple computational techniques to maximize the likelihood of identifying true active compounds [21]. The following protocol outlines the key steps:

- Target Selection and Preparation: Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or generate a high-confidence model using predictive tools like AlphaFold [19] [20]. Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, and removing water molecules, except those involved in key binding interactions.

- Compound Library Preparation: Select a diverse chemical library, such as ZINC or Enamine REAL Database [22] [21]. Prepare ligands by generating 3D conformations, optimizing geometry, and assigning correct tautomeric and ionization states at physiological pH.

- Molecular Docking: Define the binding site coordinates based on experimental data or known active sites. Perform docking simulations using software like AutoDock to generate multiple binding poses for each compound. Score each pose using the software's native scoring function to estimate binding affinity [21].

- Post-Docking Analysis and Refinement: Visually inspect the top-ranked poses to evaluate critical interaction patterns (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts). Subject the most promising complexes to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations using software like GROMACS to assess binding stability and account for protein flexibility [21].

- Consensus Scoring and Hit Selection: Apply consensus scoring strategies by re-evaluating top poses with alternative scoring functions or machine learning-based predictors to improve hit rates. Prioritize compounds for experimental validation based on a combination of docking scores, interaction quality, and stability in MD simulations [21].

Protocol for AI-Enhanced Virtual Screening

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) introduces a paradigm shift in VS efficiency [19] [22].

- Data Curation and Featurization: Compile a dataset of known active and inactive compounds against the target. Featurize the compounds using molecular descriptors or fingerprint representations that encode structural and physicochemical properties [22].

- Model Training and Validation: Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., deep neural networks, random forest) on the curated dataset to distinguish between active and inactive molecules. Validate model performance using rigorous cross-validation or a held-out test set to ensure predictive robustness and avoid overfitting [22].

- AI-Driven Triage: Apply the trained model to rapidly screen ultra-large chemical libraries, effectively triaging millions of compounds and generating a manageable shortlist of high-probability hits [19].

- Physics-Based Validation: Subject the AI-prioritized compounds to physics-based methods, such as molecular docking and MD simulations, to provide mechanistic insights and validate the AI predictions [19]. This hybrid approach leverages the speed of AI with the mechanistic detail of physics-based simulations.

Visualizing Key Pathways and Workflows

CADD Workflow in Breast Cancer Drug Discovery

Key Signaling Pathways in Breast Cancer Subtypes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective application of CADD requires a suite of computational tools and data resources. The following table details key reagents and platforms essential for conducting cutting-edge virtual screening and drug design research in breast cancer.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CADD

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in CADD | Relevance to Breast Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold [19] [20] | Structure Prediction | Provides high-accuracy 3D protein models when experimental structures are unavailable. | Crucial for modeling mutant forms of ER (ESR1) in Luminal BC and other targets with limited structural data. |

| AutoDock [21] | Docking Software | Predicts ligand binding modes and scores binding affinity. | Workhorse for SBVS against targets like HER2 kinase domain and ER. |

| GROMACS [21] | MD Simulation Software | Simulates protein-ligand dynamics and refines binding poses. | Used to validate stability of potential inhibitors and study resistance mechanisms. |

| ZINC/Enamine [22] [21] | Compound Database | Provides libraries of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Source of chemical matter for screening campaigns across all subtypes. |

| ChEMBL/PubChem [22] | Bioactivity Database | Curates bioactivity data for model training and validation. | Source of data for building QSAR and ML models specific to breast cancer targets. |

| PyMOL/Maestro | Visualization & Platform | Enables visualization of complexes and integrated workflow management. | Used for analyzing docking poses and communicating results; commercial platforms offer end-to-end workflows. |

The strategic implementation of CADD, particularly through rigorously benchmarked virtual screening protocols, provides a powerful response to the challenges of drug discovery in heterogeneous diseases like breast cancer. The continued evolution of this field is being driven by the deeper integration of AI and ML for accelerated compound triage, the rise of more accurate protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold, and the increasing emphasis on hybrid workflows that marry the speed of learning-based models with the mechanistic validation of physics-based simulations [19] [22]. Furthermore, the growing availability of large-scale, high-quality biological data (big data) and its multi-omics integration is paving the way for more holistic, systems-level approaches to target identification and drug design [22]. As these technologies mature and overcome current challenges—such as the need for robust experimental validation and better modeling of complex phenomena like drug resistance—CADD is poised to enable the design of ever more precise, subtype-informed, and personalized therapeutic strategies for breast cancer patients [19].

This guide objectively compares the performance of two modern artificial intelligence frameworks designed for breast cancer subtype classification, a critical task in oncological research and drug development. Benchmarking such tools reveals significant performance variations, underscoring the necessity for context-specific model selection.

Experimental Protocols & Performance Benchmarking

The following section details the methodologies of two distinct deep-learning approaches and quantitatively compares their performance.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

1. DenseNet121-CBAM Model Protocol

This protocol utilized a retrospective analysis of 390 patients with pathologically confirmed invasive breast cancer [17]. The model was designed to predict molecular subtypes from conventional mammography images, offering a non-invasive diagnostic alternative [17].

- Data Preprocessing: Mammographic images were acquired via a Hologic full-field digital mammography system. Two radiologists independently annotated tumor areas to create Regions of Interest (ROIs). These ROIs were expanded outward to include peritumoral background, resized to 224x224 pixels, and processed with a channel-adaptive strategy to adapt ImageNet's 3-channel pre-trained weights to single-channel mammograms [17].

- Model Architecture: The proposed model integrated Convolutional Block Attention Modules (CBAM) with a DenseNet121 backbone. This enhancement aimed to improve feature extraction by focusing on spatially informative regions, visualized via Grad-CAM heatmaps [17].

- Training Strategy: The study involved three binary classification tasks (Luminal vs. non-Luminal, HER2-positive vs. HER2-negative, triple-negative vs. non-TN) and one multiclass task (Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2+/HR+, HER2+/HR−, TNBC). To address class imbalance, simple random oversampling was applied with rates between 1.3 and 1.7. Data augmentation included random horizontal/vertical flipping, rotation (±20°), and shearing (±10°) [17].

2. TransBreastNet Model Protocol

This protocol introduced BreastXploreAI, a multimodal and multitask framework for breast cancer diagnosis. Its backbone, TransBreastNet, is a hybrid CNN-Transformer architecture designed to classify subtypes and predict disease stages simultaneously, incorporating temporal lesion progression and clinical metadata [23].

- Data Preprocessing and Modeling: The framework processes longitudinal mammogram sequences to model temporal lesion evolution. A key innovation is the generation of synthetic temporal lesion sequences to compensate for scarce real longitudinal data. It also fuses imaging features with structured clinical metadata (e.g., hormone receptor status, tumor size) for context-aware predictions [23].

- Model Architecture: The hybrid model uses CNNs for spatial feature encoding from lesions and Transformers for temporal encoding of lesion sequences. A dense network fuses the clinical metadata, and a dual-head classifier performs the joint subtype and stage prediction [23].

- Training Strategy: The model was trained for multi-task learning, which helps avoid bias towards a primary class in imbalanced datasets. Explainability is built-in through Grad-CAM and attention rollout to elucidate the model's decision-making process [23].

Performance Data Comparison

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of the two models, highlighting their different strengths.

Table 1: Benchmarking performance of AI models for breast cancer subtype classification.

| Model | Primary Classification Task | Key Performance Metric | Score | Dataset & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DenseNet121-CBAM [17] | Binary (Luminal vs. non-Luminal) | AUC | 0.759 | Internal test set of 390 patients. |

| Binary (HER2-positive vs. HER2-negative) | AUC | 0.658 | ||

| Binary (Triple-negative vs. non-TN) | AUC | 0.668 | ||

| Multiclass (5 subtypes) | AUC | 0.649 | ||

| TransBreastNet [23] | Multiclass (Subtype & Stage) | Macro Accuracy (Subtype) | 95.2% | Public mammogram dataset; performs joint stage prediction. |

| Macro Accuracy (Stage) | 93.8% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers seeking to implement or benchmark similar AI frameworks, the following computational "reagents" are essential.

Table 2: Key computational components and their functions in deep learning for medical imaging.

| Research Reagent | Function in the Experimental Pipeline |

|---|---|

| DenseNet121 Backbone | A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) that is highly effective for extracting complex spatial features from medical images like mammograms [17]. |

| Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) | An attention mechanism that enhances a CNN's ability to focus on diagnostically significant regions within an image, such as specific lesion areas [17]. |

| Transformer Encoder | A neural network architecture adept at modeling long-range dependencies and temporal sequences, crucial for analyzing the progression of lesions over time [23]. |

| Grad-CAM & Attention Rollout | Explainable AI (XAI) techniques that generate visual heatmaps, illustrating which parts of the input image most influenced the model's prediction. This builds clinical trust and aids in validation [17] [23]. |

| Clinical Metadata Encoder | A component (often a dense neural network) that processes non-imaging patient data (e.g., hormone receptor status), fusing it with image features for a holistic diagnosis [23]. |

Workflow Visualization

The diagrams below illustrate the logical structure and data flow of the two benchmarked AI frameworks.

DenseNet121-CBAM Workflow

TransBreastNet Hybrid Workflow

The benchmarking data reveals a clear trade-off: the DenseNet121-CBAM model provides a strong, interpretable baseline for subtype prediction from single images, while the TransBreastNet framework offers a more holistic, clinically nuanced approach by integrating temporal and metadata context, achieving higher accuracy at the cost of increased complexity. The choice for virtual screening and research depends on the specific experimental goals, data availability, and the need for joint pathological staging.

Core Methodologies and Subtype-Tailored Virtual Screening Applications

Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) has become an indispensable cornerstone of modern drug discovery, providing a computationally driven methodology to identify novel hit compounds by leveraging the three-dimensional structure of a biological target. The core premise involves computationally "docking" large libraries of small molecules into a target's binding site to predict interaction poses and evaluate binding affinity. From its origins in traditional molecular docking, the field is now experiencing a paradigm shift, propelled by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI). AI acceleration is enhancing nearly every aspect of the SBVS pipeline, from improved scoring functions to the management of target flexibility, thereby offering unprecedented gains in speed, accuracy, and cost-efficiency [24] [25] [26]. This evolution is particularly critical in complex areas like breast cancer research, where understanding the subtle differences in binding sites across molecular subtypes (e.g., Luminal A, HER2-positive, Triple-Negative) can inform the development of more targeted and effective therapeutics [27].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of mainstream and emerging SBVS tools, benchmarking their performance and outlining detailed experimental protocols. It is framed within the context of breast cancer research, a field that stands to benefit immensely from these advanced computational methodologies.

Benchmarking Docking and AI-Accelerated Tools

The selection of a docking engine is a fundamental decision in any SBVS workflow. The following table summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of widely used and next-generation tools.

Table 1: Benchmarking Traditional and AI-Accelerated Docking Tools

| Tool Name | Type / Core Algorithm | Key Features | Performance Highlights | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [24] [28] | Traditional / Gradient-Optimization | Open-source, fast, widely used. | Good pose reproduction; scoring can be less accurate for certain target classes. | A good baseline tool; scoring function is generic. |

| GNINA [28] | AI-Accelerated / CNN-based Scoring | Uses Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for scoring and pose refinement. | Superior performance in pose reproduction and active ligand enrichment vs. Vina; better at distinguishing true/false positives. | Higher computational demand than Vina; requires more specialized setup. |

| Glide [24] [29] | Traditional / Hierarchical Filtering | High accuracy in pose prediction, robust scoring function. | Often used in high-performance screening workflows; integrates with active learning (e.g., Glide-MolPAL). | Commercial software; can be computationally intensive. |

| SILCS-MC [29] | Physics-Based / Monte Carlo Docking with Fragments | Incorporates explicit solvation and membrane effects via Fragmap technology. | Excellent for membrane-embedded targets (e.g., GPCRs); provides realistic environmental description. | Highly specialized; computationally demanding for very large libraries. |

| Active Learning Protocols (e.g., MolPAL) [29] | AI-Driven / Iterative Surrogate Modeling | Iteratively trains models to prioritize promising compounds, reducing docking calculations. | Vina-MolPAL: Highest top-1% recovery. SILCS-MolPAL: Comparable accuracy at larger batch sizes. | Requires careful parameter tuning (batch size, acquisition function). |

A recent 2025 benchmark study across ten heterogeneous protein targets, including kinases and GPCRs, provides compelling quantitative data on the performance gains offered by AI-driven tools [28]. The study compared AutoDock Vina with GNINA, evaluating their ability to distinguish active ligands from decoys in a virtual screen.

Table 2: Virtual Screening Performance Metrics (GNINA vs. AutoDock Vina) [28]

| Metric | AutoDock Vina | GNINA | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC-ROC | Variable, lower on average | Consistently higher | GNINA shows better overall classification performance. |

| Enrichment Factor (EF) at 1% | Lower | Significantly Higher | GNINA is more effective at identifying true hits early in the ranked list. |

| Pose Reproduction Accuracy | Good | Excellent | GNINA's CNN scoring more accurately replicates crystallographic poses. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking VS Workflows

To ensure reproducible and meaningful results in virtual screening, a structured experimental protocol is essential. The following workflow is adapted from established methodologies in the literature [24] [29] [28].

Workflow Diagram: AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening

Protocol Details

Target and Library Preparation

- Target Preparation: Obtain a high-resolution crystal structure (e.g., from PDB) or a high-quality homology model. For breast cancer targets like HER2 or estrogen receptor, special attention should be paid to the protonation states of key residues, the management of structurally important water molecules, and the treatment of metal ions if present. For flexibility, consider using an ensemble of conformations generated by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [24].

- Compound Library Curation: Select a diverse and relevant chemical library (e.g., ZINC, PubChem). Prepare compounds by generating relevant tautomeric and stereoisomeric states at a physiological pH (e.g., 7.4). Apply pre-filters, such as physicochemical property filters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) or structure-based pharmacophore models, to enrich the library for drug-like compounds and reduce the screening burden [24] [30].

Docking and AI-Driven Prioritization

- Molecular Docking: Perform docking calculations using the chosen tool(s) (e.g., GNINA, Vina, Glide). Ensure the docking box is large enough to encompass the entire binding site of interest. It is good practice to validate the docking protocol first by re-docking a known co-crystallized ligand and confirming that the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the top pose is less than 2.0 Å from the experimental pose [24] [28].

- AI-Enhanced Scoring & Active Learning: After initial docking, re-score the generated poses using an AI-based scoring function. For example, in GNINA, this involves using its built-in CNN models. For ultra-large libraries, implement an active learning protocol like MolPAL, which iteratively selects the most informative compounds for docking based on a surrogate model, dramatically reducing the number of full docking calculations required [29] [28].

Post-Processing and Hit Analysis

- Consensus Ranking & Visual Inspection: Combine scores from different methods (e.g., traditional and CNN scoring) to create a consensus ranking, which can improve the robustness of hit selection. Crucially, the top-ranked compounds should be visually inspected to verify that they form sensible interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) with key residues in the binding site [30].

- Experimental Validation: The final shortlist of virtual hits should proceed to in vitro experimental validation, such as binding affinity assays (e.g., SPR) or functional cell-based assays, to confirm biological activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

A successful SBVS campaign relies on a foundation of high-quality data and software tools. The following table details key resources mentioned in the featured research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SBVS Workflows

| Category / Item | Function in SBVS Workflow | Relevant Context / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary source for experimentally determined 3D structures of target proteins. | Essential for obtaining reliable starting structures for docking (e.g., HER2 kinase domain). |

| Chemical Libraries (ZINC, PubChem) | Provide vast collections of purchasable or synthesizable small molecules for virtual screening. | ZINC database contains over 13 million compounds for screening [24]. |

| AutoDock Vina | Open-source docking program for initial pose generation and baseline scoring. | Serves as a benchmark and is integrated into active learning pipelines (Vina-MolPAL) [29]. |

| GNINA | AI-powered docking suite that uses CNNs for superior pose scoring and ranking. | Demonstrated to outperform Vina in virtual screening enrichment and pose accuracy [28]. |

| MolPAL | Active learning framework that optimizes the screening of ultra-large chemical libraries. | Can be coupled with Vina, Glide, or SILCS to improve screening efficiency [29]. |

| Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) | Deep learning component that improves model interpretability by highlighting relevant image regions. | Used in DenseNet121-CBAM models for analyzing mammograms, analogous to identifying key binding features in a protein pocket [17]. |

The field of structure-based virtual screening is undergoing a rapid transformation, moving from reliance on traditional physics-based docking algorithms toward hybrid and fully AI-accelerated workflows. As benchmark studies have shown, tools like GNINA that integrate deep learning offer tangible improvements in both pose prediction accuracy and, most critically, the enrichment of truly active compounds in virtual screens. When combined with strategic active learning protocols, these AI-powered methods enable researchers to navigate the vastness of chemical space with unprecedented efficiency and precision. For scientists working on challenging targets in breast cancer and beyond, adopting these advanced SBVS workflows promises to significantly accelerate the journey from a protein structure to a promising therapeutic hit.

Within modern oncology drug discovery, ligand-based computational approaches provide powerful methods for identifying novel chemical scaffolds when structural information for the primary target is limited or unavailable. In the context of breast cancer research—a disease characterized by significant molecular heterogeneity across subtypes such as Luminal, HER2-positive, and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)—these approaches enable researchers to leverage existing bioactivity data to accelerate the discovery of new therapeutic candidates [7]. This guide objectively compares the performance and application of two fundamental ligand-based methods: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling and pharmacophore modeling, with a specific focus on their utility in scaffold identification for virtual screening campaigns targeting breast cancer subtypes.

Core Methodologies and Comparative Performance

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR modeling establishes a mathematical relationship between the chemical structure of compounds and their biological activity [31]. It operates on the principle that structurally similar compounds exhibit similar biological activities, and uses molecular descriptors to quantify these structural properties.

Key Experimental Protocols:

- Data Collection and Curation: A set of compounds with known biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀) against a specific breast cancer target or cell line is assembled. For combinational therapy QSAR, this includes data on anchor and library drugs and their combined biological activity (Combo IC₅₀) [32].

- Molecular Descriptor Calculation: Software tools like PaDEL or PaDELPy are used to compute numerical descriptors representing the molecules' structural, topological, geometric, electronic, and physicochemical properties [32] [31].

- Model Building and Validation: The dataset is split into training and test sets. Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) algorithms—such as Random Forest, Deep Neural Networks (DNN), and Support Vector Regressor (SVR)—build the predictive model using the training set [32]. The model is rigorously validated using statistical parameters like the coefficient of determination (R²) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). For instance, a DNN model achieved an R² of 0.94 and an RMSE of 0.255 in predicting the combinational biological activity of drug pairs in breast cancer cell lines [32].

Pharmacophore Modeling

A pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supra-molecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [33]. Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling extracts common chemical features from a set of known active ligands, arranged in a specific 3D orientation, which are critical for biological activity [33] [34].

Key Experimental Protocols:

- Ligand Selection and Conformation Generation: A set of active compounds with diverse structures but common activity against a target (e.g., aromatase in breast cancer) is selected. Their 3D structures are generated, and conformational models are created to account for flexibility [35] [34].

- Feature Identification and Model Generation: Software such as PharmaGist or the 3D QSAR Pharmacophore Generation module in Discovery Studio is used to identify common pharmacophore features from the aligned active ligands. These features include Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA), Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD), Hydrophobic areas (H), and Aromatic rings (AR) [33] [31] [34].

- Model Validation: The model is validated using a test set of compounds and sometimes through Fisher randomization to ensure its predictive power is not due to chance [34]. The model's ability to distinguish active compounds from inactive decoys is assessed using metrics like the Enrichment Factor (EF) and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) plot [36].

Performance Comparison in Virtual Screening

The table below summarizes the comparative performance of QSAR and pharmacophore modeling in key aspects relevant to scaffold identification and virtual screening.

Table 1: Performance and Application Comparison of Ligand-Based Approaches

| Aspect | QSAR Modeling | Pharmacophore Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Quantitative activity prediction; excellent for lead optimization [35] | Identification of novel chemotypes via "scaffold hopping" [35] |

| Data Requirement | Requires a sufficiently large and congeneric set of compounds with known activity data [32] | Can be generated from a relatively small set of known active ligands [33] |

| Scaffold Identification | Identifies scaffolds based on descriptor-activity relationships; less intuitive for direct scaffold design | Directly defines the essential steric and electronic features for activity, enabling search for diverse scaffolds possessing these features [33] |

| Handling of Cancer Heterogeneity | Can build subtype-specific models (e.g., for Luminal or TNBC) by using relevant cell line or target data [32] [7] | A single model can screen for compounds active against a specific target across subtypes; subtype-specificity depends on the ligands used for modeling |

| Key Limitation | Predictive capability is limited to the chemical space defined by the training set; poor extrapolation | Lacks quantitative activity prediction unless combined with QSAR (3D-QSAR pharmacophore) [34] |

| Typical Output | Predictive model for biological activity (e.g., pIC₅₀) | 3D spatial query for database screening |

Integrated Workflows for Enhanced Performance

Benchmarking studies reveal that integrating QSAR and pharmacophore modeling into a single workflow significantly enhances virtual screening performance. The sequential application of these methods allows researchers to leverage the strengths of each approach.

Protocol for an Integrated QSAR-Pharmacophore Screening Workflow:

- 3D-QSAR Pharmacophore Generation: A pharmacophore model is built based on the QSAR of training set compounds, correlating the spatial arrangement of features with biological activity levels [34].

- Virtual Screening: The validated pharmacophore model is used as a 3D query to screen large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, NCI) to retrieve potential hit compounds with novel scaffolds [35] [34].

- Activity Prediction and Prioritization: The retrieved hits are then passed through a previously developed and validated QSAR model to predict their biological activity and prioritize the most promising candidates for further study [35] [37].

- Experimental Validation: Top-ranked compounds are subjected to in vitro and in vivo testing to confirm computational predictions [7].

This workflow was successfully applied to identify novel steroidal aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer. A pharmacophore model containing two acceptor atoms and four hydrophobic centers was used to screen the NCI2000 database, and the retrieved hits' activities were predicted using CoMFA and CoMSIA models, leading to the identification of six promising hit compounds [35].

Figure 1: Integrated ligand-based virtual screening workflow, combining pharmacophore and QSAR approaches for identifying and prioritizing novel scaffolds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of ligand-based approaches relies on a suite of computational tools and data resources. The table below details key solutions used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ligand-Based Modeling

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| PaDEL / PaDELPy [32] [31] | Software Descriptor | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints for QSAR. | Generating structural descriptors for training a combinational QSAR model on breast cancer cell lines [32]. |

| ZINC Database [36] [31] | Chemical Database | A curated collection of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Source of natural products for pharmacophore-based screening against dengue virus NS3 protease [31]. |

| PharmaGist [31] | Software Pharmacophore | Generates ligand-based pharmacophore models from a set of active molecules. | Creating a pharmacophore hypothesis from top-active 4-Benzyloxy Phenyl Glycine derivatives [31]. |

| ZINCPharmer [31] | Online Tool | Screens the ZINC database using a pharmacophore model as a query. | Identifying compounds with features similar to known active ligands [31]. |

| LigandScout [36] | Software Pharmacophore | Creates structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models and performs virtual screening. | Generating a structure-based pharmacophore model for XIAP protein from a protein-ligand complex [36]. |

| BuildQSAR [31] | Software QSAR | Develops QSAR models using selected descriptors and the Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) method. | Building a 2D QSAR model to predict the IC₅₀ of dengue virus protease inhibitors [31]. |

| GDSC Database [32] | Bioactivity Database | Provides drug sensitivity data for a wide range of cancer cell lines, including combinational drug screening data. | Source of data for building a combinational QSAR model for breast cancer therapy [32]. |

Ligand-based approaches, namely QSAR and pharmacophore modeling, are indispensable for scaffold identification in breast cancer drug discovery. While QSAR excels at providing quantitative activity predictions for lead optimization, pharmacophore modeling is superior for scaffold hopping and identifying novel chemotypes. Benchmarking studies and experimental data confirm that the integration of these methods into a cohesive workflow, often supplemented with molecular docking and dynamics simulations, provides a powerful strategy for navigating the complex chemical and biological space of breast cancer subtypes. This integrated approach enhances the efficiency of virtual screening campaigns, ultimately accelerating the discovery of new therapeutic agents to address the critical challenge of tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance.

Integrating AI and Machine Learning for Sensitivity Prediction and Biomarker Discovery

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is fundamentally reshaping the landscape of breast cancer research, particularly in the critical areas of sensitivity prediction and biomarker discovery. This transformation is most evident in the benchmarking of virtual screening performance across different breast cancer subtypes. AI systems are increasingly being validated against, and integrated with, traditional biological assays to stratify patient risk, predict treatment response, and identify novel molecular signatures directly from standard clinical images and data [38] [39] [40]. The emerging paradigm leverages deep learning models to extract subtle, sub-visual patterns from mammography, histopathology slides, and multi-omics data, establishing imaging-derived biomarkers as non-invasive proxies for complex molecular phenotypes [39] [41]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of AI/ML performance against conventional methods, detailing experimental protocols and offering a toolkit for researchers aiming to implement these technologies in their drug discovery and development pipelines for breast cancer.

Performance Benchmarking: AI vs. Conventional Workflows

The performance of AI/ML models is benchmarked across several key clinical tasks. The following tables synthesize quantitative results from recent studies, allowing for direct comparison between emerging computational approaches and established diagnostic and predictive methods.

Table 1: Performance of AI Models in Breast Cancer Subtype Classification

| Clinical Task | AI Model / Approach | Performance Metric | Conventional Method (for context) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNBC Identification (from H&E images) | TRIP System (Deep Learning) | AUC: 0.980 (Internal), 0.916 (External) | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) & FISH (Gold Standard, costly/time-consuming) | [41] |

| Molecular Subtyping (from Mammography) | DenseNet121-CBAM | AUC: 0.759 (Luminal), 0.668 (TN), 0.649 (Multiclass) | Needle Biopsy & IHC (Invasive, risk of sampling error) | [42] |

| HER2 Status Prediction | Vision Transformer (ViT) | Accuracy up to 99.92% reported in mammography | IHC & FISH (Tissue-based, requires specialized equipment) | [38] |

| Biomarker Status Prediction | End-to-End CNN on CEM | AUC: 0.67 for HER2 status | IHC on biopsy sample | [42] |

Table 2: AI Performance in Screening, Prognosis, and Workflow Efficiency

| Application Area | AI Model / Workflow | Performance Outcome | Comparison Baseline | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population Screening | AI-supported double reading (Vara MG) | Detection Rate: 6.7/1000 (vs. 5.7/1000); Recall rate non-inferior | Standard Double Reading (without AI) | [43] |

| TNBC Prognosis (Disease-Free Survival) | TRIP System | C-index: 0.747 (Internal), 0.731 (External) | Traditional clinicopathological features (e.g., TNM stage) | [41] |

| Workflow Triage | AI Normal Triage + Safety Net | 56.7% of exams auto-triaged as normal; Safety Net triggered for 1.5% of exams, contributing to 204 cancer diagnoses | Full manual review by radiologists | [43] |

| Risk Stratification | AI-based Mammographic Risk Models | Improved discrimination vs. classical models (e.g., Gail, Tyrer-Cuzick); AUCs often >0.70 | Classical Clinical Risk Models (AUC often <0.65-0.70) | [40] |

Experimental Protocols for Key AI Applications

Protocol 1: Predicting Molecular Subtypes from Mammography Images

This protocol is based on the study by Luo et al. (2025) that developed a deep learning model for predicting molecular subtypes from conventional mammography [42].

- Objective: To develop and validate a deep learning model for non-invasive prediction of breast cancer molecular subtypes (Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2+/HR+, HER2+/HR-, TNBC) using standard mammography images.

- Data Curation:

- Cohort: Retrospective dataset of 390 patients with pathologically confirmed invasive breast cancer and preoperative mammography.

- Inclusion Criteria: Primary invasive breast cancer with mammographically visible tumor mass, molecular subtype determined by postoperative pathology (gold standard).

- Exclusion Criteria: Inflammatory breast cancer, bilateral/pathologically heterogeneous lesions, prior radiotherapy/chemotherapy, or invasive procedures within a week before mammography.

- Image Annotation: Two qualified radiologists independently annotated all identifiable tumor areas on craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO) views using ITK-SNAP software.

- Preprocessing & Augmentation:

- ROI Extraction: Annotated tumor regions were extracted and expanded outward by a specified pixel bound to include peritumoral background, then resized to 224x224 pixels.

- Class Imbalance Handling: Simple random oversampling was applied (e.g., oversampling rate of 1.7 for TNBC class).

- Data Augmentation: Geometric transformations included random horizontal flipping (50% probability), vertical flipping (50% probability), random rotation (±20°), and horizontal shearing (±10°).

- Model Architecture & Training:

- Backbone: DenseNet121 was selected as the backbone after comparative experiments with ResNet101, MobileNetV2, and Vision Transformers.

- Innovation: Integration of Convolutional Block Attention Modules (CBAM) to enhance feature learning.

- Input Adaptation: A channel-adaptive pretrained weight allocation strategy was used to adapt ImageNet (3-channel) pretrained weights to single-channel mammography images.

- Tasks: The model was trained for binary (Luminal vs. non-Luminal, HER2-positive vs. HER2-negative, TN vs. non-TN) and multiclass classification tasks.

- Validation & Interpretation:

- Validation: Performance was evaluated on an independent test set using AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

- Interpretability: Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was used to generate heatmaps, highlighting that the model focused on peritumoral regions as critical discriminative features [42].

Protocol 2: Developing an AI System for TNBC Diagnosis and Prognosis

This protocol is based on the development and validation of the TRIP system, a deep learning model for identifying Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) and predicting its prognosis from histopathology images [41].

- Objective: To create a unified, end-to-end AI system for accurate TNBC identification and prognosis prediction (disease-free and overall survival) using haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained whole slide images (WSIs).

- Data Sourcing and Cohort Design:

- Development Cohort: 2045 patients with breast cancer from The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (FAH), including 451 TNBC patients with follow-up outcomes.

- External Validation: Independent retrospective cohorts from four tertiary hospitals in China (SDPH, SRRS, YWCH, WHCH) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset, totaling 2793 cases for identification and 463 for prognosis.

- Exclusion Criteria: Patients with other synchronous malignant neoplasms within five years or those who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- AI Model Development:

- System Architecture: The TRIP system integrates a pathology foundation model with effective long-sequence modelling to process giga-pixel WSIs.

- Outputs: A single pipeline capable of both classifying TNBC versus other subtypes and predicting continuous survival outcomes.

- Performance Evaluation:

- TNBC Identification: Evaluated using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) on internal and external cohorts.

- Prognosis Prediction: Evaluated using the Concordance Index (C-index) for disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) predictions.

- Interpretability and Biological Validation:

- Heatmaps: Generated to visualize key histologic features learned by the model, revealing associations with nuclear atypia, necrosis, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, and immune-cold microenvironments.

- Multi-Omics Analysis: Conducted to explore TNBC heterogeneity and identify molecular subtypes with distinct immune and pro-tumour signalling profiles, providing biological plausibility for the model's prognostic accuracy [41].

Visualizing the AI-Driven Biomarker Discovery Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data relationships in an AI-driven pipeline for sensitivity prediction and biomarker discovery, integrating elements from the experimental protocols above.

AI-Driven Biomarker Discovery Workflow

This workflow visualizes the end-to-end pipeline, from multi-modal data input to clinical validation, highlighting the key stages and components required for robust AI-driven biomarker discovery and sensitivity prediction in breast cancer research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI-Driven Breast Cancer Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Relevance to AI Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| H&E-Stained Whole Slide Images (WSIs) | Digital pathology slides used as primary input for deep learning models predicting subtype and prognosis. | The TRIP system demonstrated that standard H&E slides contain latent information for accurate TNBC identification (AUC 0.98) and survival prediction [41]. |

| Annotated Mammography Datasets (CC & MLO views) | Curated imaging datasets with radiologist-annotated regions of interest (ROIs) for model training. | Essential for developing models like DenseNet121-CBAM for non-invasive molecular subtyping; annotations enable supervised learning [42]. |

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Kits (ER, PR, HER2) | Gold standard for determining molecular subtype and providing ground truth labels for AI model training and validation. | Critical for validating AI predictions against biological truth; necessary for creating labeled datasets [42] [41]. |

| Multi-Omics Datasets (Genomics, Transcriptomics) | Data used for biological validation and to explore correlations between AI-derived image features and molecular pathways. | Multi-omics analysis supported the TRIP system's prognostic accuracy by revealing distinct molecular subtypes underlying the AI-predicted risk groups [41]. |

| Pre-Trained Deep Learning Models (e.g., DenseNet, Vision Transformers on ImageNet) | Foundational models that can be adapted for medical image tasks via transfer learning, mitigating data scarcity. | A channel-adaptive strategy was used to adapt ImageNet-pretrained DenseNet121 weights for single-channel mammography, improving performance [42]. |

| AI Explainability Tools (Grad-CAM, Attention Heatmaps) | Software libraries to generate visual explanations of model predictions, fostering trust and providing biological insight. | Grad-CAM heatmaps revealed that the DenseNet121-CBAM model focused on peritumoral regions, offering interpretability [42]. |

The benchmarking data and experimental protocols presented herein demonstrate that AI and ML models are achieving performance levels that suggest their potential as valuable supplements, and in some cases alternatives, to more invasive or costly conventional methods for sensitivity prediction and biomarker discovery in breast cancer. Key findings indicate strong capabilities in TNBC identification, molecular subtyping from mammography, and prognostic risk stratification.

However, the field must address critical challenges before widespread clinical adoption. Generalizability remains a concern, as model performance can diminish on external datasets from different institutions due to variations in imaging equipment, protocols, and patient populations [38] [39]. Furthermore, prospective clinical trials demonstrating improvement in patient outcomes are still needed for many of these AI systems [40] [41]. The future of this field lies in the development of robust, multimodal AI models that integrate imaging, clinical, and genomic data within validated frameworks, ensuring that these powerful tools can be translated safely and effectively into routine research and clinical practice to advance personalized breast cancer therapy [38] [40] [44].

Clinical Context: Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes

Breast cancer is not a single disease but a collection of molecularly distinct subtypes that dictate prognosis, therapeutic strategies, and drug development approaches. The classification is primarily based on the expression of hormone receptors (HR)—estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR)—and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). These biomarkers define four principal subtypes with dramatically different clinical behaviors and therapeutic responses [6] [45].

Table: Epidemiology and Survival Profiles of Major Breast Cancer Subtypes

| Molecular Subtype | Approximate Prevalence | 5-Year Relative Survival | Key Clinical Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR+/HER2- (Luminal A/B) | ~70% [46] | 95.6% [46] | Hormone-driven; best prognosis; treated with endocrine therapy (e.g., Tamoxifen, AIs) ± CDK4/6 inhibitors [6] [47]. |

| HR+/HER2+ (Luminal B) | ~9% [46] | 91.8% [46] | Aggressive; responsive to both endocrine and HER2-targeted therapies (e.g., Trastuzumab, T-DXd) [6] [47]. |

| HR-/HER2+ (HER2-Enriched) | ~4% [46] | 86.5% [46] | Very aggressive; highly responsive to modern HER2-targeted therapies and Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) [47] [48]. |

| Triple-Negative (TNBC) | ~10% [46] | 78.4% [46] | Most aggressive subtype; lacks targeted receptors; chemotherapy and immunotherapy are mainstays; poor prognosis [6] [49]. |

These subtypes also exhibit distinct metastatic patterns, a critical consideration for late-stage drug development. HR+/HER2- tumors show a propensity for bone metastasis, while HER2-positive and TNBC subtypes are more likely to involve visceral organs and the brain [50]. Multi-organ metastases, particularly combinations involving the brain, are associated with the poorest prognosis, underscoring the need for subtype-specific therapeutic strategies [50].

Current Therapeutic Landscape and Challenges

The treatment paradigm for advanced breast cancer is rapidly evolving, marked by the rise of targeted therapies and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs). Recent phase III trials are redefining standards of care, particularly for HER2-positive and TNBC subtypes [47].

HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

The DESTINY-Breast09 trial established a new first-line benchmark for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. It demonstrated that Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (T-DXd) plus Pertuzumab significantly outperformed the previous standard (taxane + trastuzumab + pertuzumab), reducing the risk of disease progression or death by 44% and achieving a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 40.7 months [47]. Despite its efficacy, toxicity management remains crucial, with interstitial lung disease (ILD) observed in approximately 12% of patients in the experimental arm [47] [48].

Hormone Receptor-Positive (HR+), HER2-Negative Breast Cancer