Benchmarking 3D-QSAR Against Molecular Docking: A Practical Guide for Predictive Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to benchmark 3D-QSAR models against molecular docking results.

Benchmarking 3D-QSAR Against Molecular Docking: A Practical Guide for Predictive Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to benchmark 3D-QSAR models against molecular docking results. It explores the foundational principles of both methods, detailing their synergistic application in modern drug discovery pipelines. The content covers practical methodologies for integrated use, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and establishes rigorous protocols for validation and performance comparison. By synthesizing recent benchmarking studies and emerging trends, including the impact of artificial intelligence, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to critically evaluate and effectively implement these computational tools for more reliable and efficient lead optimization and activity prediction.

Understanding the Core Principles: 3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking in Modern Drug Design

The Roles and Evolution of 3D-QSAR and Docking in Structure-Based Drug Discovery

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) has revolutionized modern therapeutics development by enabling the rational design of molecules targeting specific proteins [1]. Within this paradigm, 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) and molecular docking have emerged as cornerstone computational methodologies. While both aim to accelerate drug discovery, they operate on fundamentally different principles and offer complementary insights. Molecular docking focuses on predicting the binding conformation and affinity of a ligand within a target protein's binding pocket, essentially solving a spatial alignment problem [2]. In contrast, 3D-QSAR is a ligand-based approach that constructs statistical models correlating the three-dimensional molecular fields of compounds with their biological activity, without requiring target receptor structure [3] [4]. The evolution of these techniques has seen them grow from complementary tools to increasingly integrated components in sophisticated drug discovery workflows, often enhanced by machine learning and artificial intelligence [5] [6]. This guide objectively compares their performance, applications, and limitations within the context of benchmarking 3D-QSAR models against molecular docking results, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for method selection and implementation.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Mechanisms

Molecular Docking: Structure-Based Predictive Binding

Molecular docking computationally predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (receptor) [2]. The process essentially simulates molecular recognition between a drug candidate and its protein target. Docking algorithms employ scoring functions to evaluate and rank potential binding poses based on estimated binding free energy, considering factors like hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, and desolvation effects [2]. The approach has evolved from rigid body docking, where both ligand and receptor are treated as fixed structures, to flexible docking that accounts for ligand conformational changes and, in advanced implementations, limited receptor flexibility [2]. Modern docking tools like AutoDock Vina, GLIDE, and GOLD can screen vast chemical libraries, identifying potential hits by predicting their complementarity to a known binding site [2] [5].

3D-QSAR: Ligand-Based Activity Prediction

3D-QSAR establishes a quantitative correlation between the three-dimensional structural properties of a set of compounds and their biological activities using statistical methods [3] [4]. Unlike docking, 3D-QSAR does not require knowledge of the target protein's structure. Instead, it relies on the comparative analysis of molecular fields - steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bonding - around aligned active molecules [4]. The most established 3D-QSAR techniques include Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) [3] [4]. These methods generate contour maps that visually identify regions where specific molecular properties enhance or diminish biological activity, providing interpretable guidance for molecular optimization [4]. The quality of 3D-QSAR models depends critically on the structural alignment of training set molecules and the conformational selection of the bioactive form [3].

Key Conceptual Differences and Workflows

The table below summarizes the fundamental distinctions between these two approaches:

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between Molecular Docking and 3D-QSAR

| Feature | Molecular Docking | 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Requirement | Target protein 3D structure | Set of active ligands with known activities |

| Molecular Flexibility | Handles ligand flexibility; can incorporate protein flexibility | Typically uses fixed conformations; alignment-dependent |

| Primary Output | Binding pose and predicted binding affinity | Quantitative model relating molecular fields to biological activity |

| Information Provided | Atomic-level interaction details with protein | Structure-activity relationship contours for ligand optimization |

| Throughput | High (virtual screening) to Medium (precise pose prediction) | Medium (model building) to High (activity prediction) |

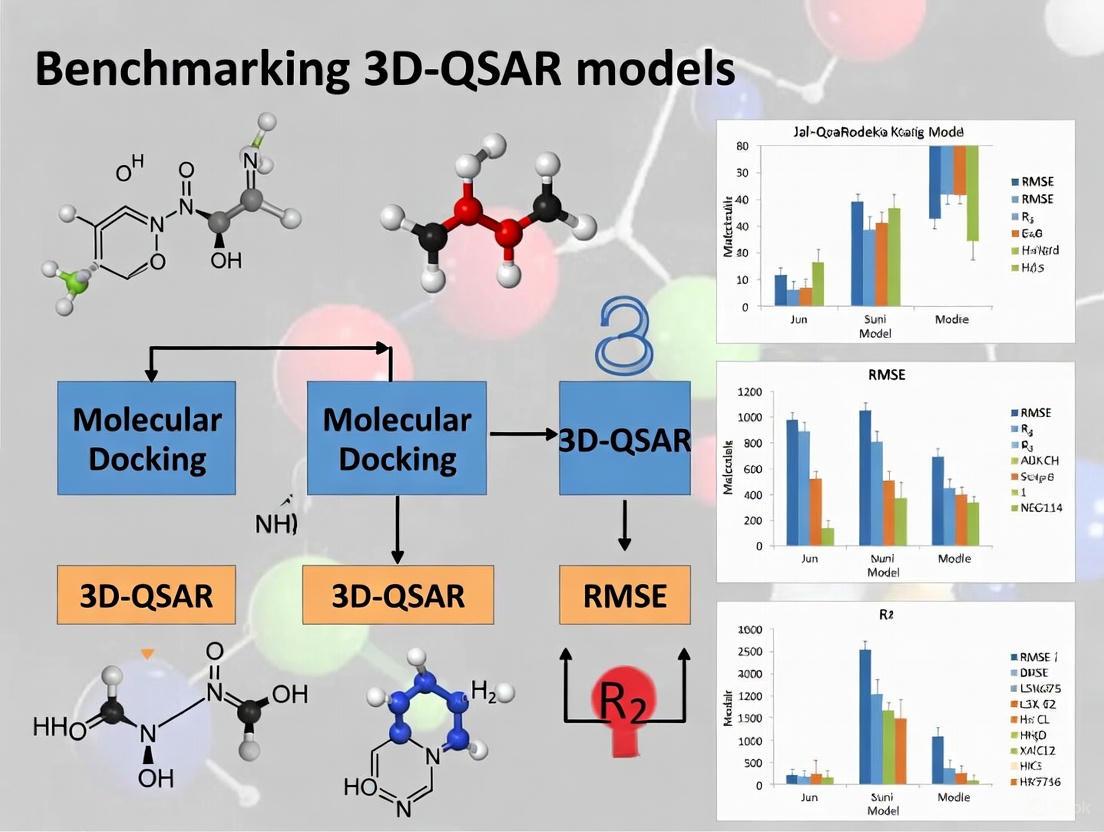

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship and typical workflow integration between these methodologies in modern drug discovery:

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Benchmarking studies across diverse protein targets and chemical classes provide objective performance measures for both techniques. The table below summarizes key statistical metrics from recent studies:

Table 2: Statistical Performance Metrics from Recent 3D-QSAR and Docking Studies

| Study/Target | Method | q² | r² | SEE | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAO-B Inhibitors [3] | COMSIA | 0.569 | 0.915 | 0.109 | Frontiers in Pharmacology (2025) |

| α-Glucosidase Inhibitors [4] | CoMFA | 0.594 | 0.958 | 0.100 | Journal of Molecular Structure (2025) |

| α-Glucosidase Inhibitors [4] | CoMSIA/SED | 0.619 | 0.972 | 0.077 | Journal of Molecular Structure (2025) |

| Anti-tubercular Agents [7] | Atom-based 3D-QSAR | 0.859 | 0.952 | - | BMC Chemistry (2025) |

Predictive Accuracy Comparison

Direct benchmarking of 3D-QSAR and molecular docking reveals their complementary strengths in predictive accuracy:

Table 3: Comparative Predictive Performance in Lead Optimization

| Performance Aspect | Molecular Docking | 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Pose Prediction | ~1.0-2.0 Å RMSD for top poses [3] | Not applicable (no pose prediction) |

| Activity Prediction (R²) | Moderate (0.4-0.7) for affinity [2] | High (0.9+ for good models) [4] |

| New Scaffold Identification | Strong (structure-based) [5] | Limited to chemical space similar to training set |

| Quantitative SAR Guidance | Limited to interaction patterns | Excellent (visual contour maps) [4] |

| Virtual Screening Enrichment | 10-100 fold enrichment reported [5] | Dependent on training set diversity |

Synergistic Application in Case Studies

Recent studies demonstrate the power of integrating both methodologies. In designing novel 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamides as MAO-B inhibitors, researchers first developed a COMSIA model with strong predictive statistics (q² = 0.569, r² = 0.915), then validated proposed compounds through molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations [3]. The most promising compound (31.j3) not only showed excellent predicted IC₅₀ but also maintained stable binding in MD simulations with RMSD fluctuations between 1.0-2.0 Å [3]. Similarly, for benzimidazole-based α-glucosidase inhibitors, the CoMSIA/SED model achieved outstanding statistics (q² = 0.619, r² = 0.972) and the contour maps informed the design of new derivatives subsequently validated by docking [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard 3D-QSAR Implementation Protocol

The typical workflow for developing validated 3D-QSAR models involves multiple meticulous steps:

Data Set Curation and Preparation: A series of compounds (typically 20-50) with known biological activities (IC₅₀, Ki) is collected. The biological values are converted to pIC₅₀ or pKi values using the formula pIC₅₀ = -log₁₀(IC₅₀) to ensure a linear relationship with free energy changes [4] [7]. The data set is divided into a training set (≈75-85%) for model development and a test set (≈15-25%) for external validation [4].

Molecular Modeling and Conformational Alignment: 3D structures of all compounds are built and energy-minimized using molecular mechanics or semi-empirical methods. A critical step is the alignment of all molecules based on a common scaffold or pharmacophoric features using methods like atom-based fitting or field-based alignment [4].

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building: Molecular interaction fields are calculated using probes (e.g., sp³ carbon for steric, proton for electrostatic) at grid points surrounding the molecules. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is used to correlate these field values with biological activity while avoiding overfitting [3] [4].

Model Validation: Internal validation using leave-one-out or leave-many-out cross-validation gives the q² value. External validation using the test set assesses predictive power. The model is also checked for chance correlation through Y-scrambling [7].

Contour Map Analysis and Interpretation: The final model is visualized as 3D contour maps showing regions where specific molecular properties (steric bulk, electronegativity, etc.) enhance (favored) or diminish (disfavored) biological activity, providing direct guidance for molecular design [4].

Standard Molecular Docking Protocol

A robust molecular docking workflow consists of these key stages:

Protein Preparation: The 3D structure of the target protein is obtained from crystallographic databases (PDB). The structure is cleaned by removing water molecules (except functionally important ones), adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and correcting protonation states of amino acid residues [8] [2].

Binding Site Definition: The specific binding pocket is identified either from known ligand coordinates in crystallographic complexes or through binding site prediction algorithms. A grid box is defined to encompass the binding site with sufficient margin for ligand exploration [8].

Ligand Preparation: Ligand structures are energy-minimized, possible tautomers and protonation states are generated, and rotatable bonds are defined for flexibility during docking [2].

Docking Execution and Pose Prediction: Multiple docking runs are performed for each ligand using algorithms that explore conformational space (genetic algorithms, Monte Carlo methods, etc.) to generate plausible binding poses [2].

Scoring and Pose Selection: Generated poses are ranked using scoring functions, and top-ranked poses are analyzed for key molecular interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking) with protein residues [8] [2].

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these methodologies integrate in modern computational drug discovery:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools and Software

The experimental implementation of 3D-QSAR and molecular docking requires specialized software tools and computational resources. The table below catalogues key platforms and their applications:

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for 3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Features | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sybyl-X [3] | 3D-QSAR Modeling | CoMFA, CoMSIA implementations | MAO-B inhibitor design [3] |

| AutoDock Vina [8] [5] | Molecular Docking | Efficient scoring, user-friendly | Natural inhibitor identification [8] |

| Schrödinger Suite [7] | Comprehensive Drug Design | Protein preparation, Glide docking, QSAR | Anti-tubercular agent design [7] |

| GROMACS [3] [6] | Molecular Dynamics | Simulation of biomolecular systems | Binding stability analysis [3] |

| Open-Babel [8] | Chemical Format Conversion | File format interoperability | Virtual screening workflows [8] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor [8] | Molecular Descriptors | Calculation of chemical descriptors | Machine learning-based screening [8] |

| RDKit [5] | Cheminformatics | Molecular fingerprint generation | Machine learning-guided docking [5] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The convergence of 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and artificial intelligence represents the most significant evolution in structure-based drug design. Machine learning algorithms are now being used to guide docking screens of ultralarge chemical libraries, reducing computational costs by more than 1,000-fold while maintaining sensitivity values of 0.87-0.88 [5]. For instance, CatBoost classifiers trained on molecular fingerprints can prioritize compounds for docking, enabling efficient screening of billion-compound libraries [5].

Hybrid frameworks that combine the strengths of different methodologies are emerging as powerful solutions. The Collaborative Intelligence Drug Design (CIDD) framework integrates the structural precision of 3D-SBDD models with the chemical reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs), achieving a remarkable success ratio of 37.94% compared to 15.72% for traditional SBDD approaches [1]. Similarly, end-to-end platforms like DrugAppy combine AI algorithms with computational chemistry methodologies, validating their approach through identification of PARP and TEAD inhibitors with activity matching or surpassing reference compounds [6].

The integration of molecular dynamics simulations has become standard practice for validating docking and QSAR predictions, with RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and SASA analyses providing insights into binding stability and conformational changes [3] [8]. These advancements are pushing the boundaries of what's possible in computational drug discovery, enabling more accurate predictions and efficient exploration of chemical space.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict biological activity based on molecular structure. While traditional 2D-QSAR utilizes numerical descriptors that are invariant to molecular conformation, 3D-QSAR advances this paradigm by incorporating the three-dimensional spatial characteristics of molecules [9]. This approach recognizes that biochemical interactions occur in three-dimensional space, where subtle variations in molecular shape and electrostatic properties significantly impact biological activity.

The fundamental principle underlying 3D-QSAR is that differences in biological response among a series of compounds can be accounted for by variations in their spatial molecular properties [10]. By quantifying these properties and correlating them with measured activities, 3D-QSAR models provide predictive frameworks that guide the rational design of novel therapeutic agents. These models have become indispensable in pharmaceutical and agrochemical research, serving as valuable predictive tools that complement experimental approaches [10].

This guide examines core 3D-QSAR methodologies with a specific focus on their benchmarking against molecular docking approaches. We present systematically compared experimental data, detailed protocols, and analytical visualizations to equip researchers with practical insights for method selection and implementation in drug development projects.

Core Concepts: Fields, Alignment, and Analysis

Molecular Interaction Fields

In 3D-QSAR, molecules are represented not just by their atomic coordinates but by their interaction potentials with theoretical probes. Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), a pioneering method developed by Cramer et al., calculates steric fields using Lennard-Jones potentials and electrostatic fields using Coulombic potentials [10]. These calculations position each molecule within a 3D grid lattice, with a probe atom measuring interaction energies at regularly spaced grid points [9].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extends this concept by employing Gaussian-type functions to evaluate multiple fields simultaneously: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor properties [9]. This approach smooths abrupt potential changes and often enhances model interpretability, particularly for structurally diverse datasets [9].

Molecular Alignment Strategies

Molecular alignment constitutes one of the most critical and technically demanding steps in alignment-dependent 3D-QSAR methods [9]. The objective is to superimpose all molecules in a shared 3D reference frame that reflects their putative bioactive conformations, analogous to aligning keys in the same lock [9].

Common alignment approaches include:

- Scaffold-based alignment: Using shared structural frameworks like Bemis-Murcko scaffolds or maximum common substructures (MCS) [9]

- Field-based alignment: Employing molecular field similarity algorithms such as Field-Based Similarity Searching (FBSS) [11]

- Pharmacophore-based alignment: Utilizing presumed key pharmacophoric elements

- Template-based alignment: Fitting to a known active compound or receptor structure

Alignment-independent methods have emerged as valuable alternatives, including Comparative Molecular Moment Analysis (CoMMA), Grid-Independent Descriptors (GRIND), and VolSurf approaches [10]. These techniques circumvent alignment challenges by using descriptors invariant to rotation and translation.

Chemometric Analysis

With molecular descriptors calculated, chemometric analysis establishes the mathematical relationship between field values and biological activity. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is the predominant statistical method in 3D-QSAR, effectively handling the large number of correlated descriptors by projecting them onto a smaller set of latent variables [9] [12].

Model validation is essential, employing techniques like leave-one-out cross-validation (quantified by Q²) and external test set validation (quantified by R²pred) [9] [12]. A robust model demonstrates both high explanatory power for training data and predictive accuracy for unseen compounds.

Comparative Methodologies: 3D-QSAR vs. Molecular Docking

Fundamental Approach and Data Requirements

Table 1: Methodological Comparison Between 3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking

| Aspect | 3D-QSAR | Molecular Docking |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Basis | Ligand-based (with exceptions) | Structure-based |

| Data Requirements | Set of compounds with known activity | Protein 3D structure (theoretical or experimental) |

| Molecular Recognition Model | Statistical correlation with molecular fields | Physical simulation of binding interactions |

| Key Output | Contour maps guiding structural modification | Predicted binding pose and affinity |

| Treatment of Flexibility | Limited to ligand conformational analysis | Can incorporate both ligand and receptor flexibility |

| Information Source | Experimental activity data | Protein-ligand complementarity |

3D-QSAR primarily follows a ligand-based approach, establishing statistical correlations between molecular fields and biological activity without requiring explicit knowledge of the target structure [10]. In contrast, molecular docking is fundamentally structure-based, relying on 3D protein structures to simulate and predict how ligands interact with their biological targets [2].

Performance Benchmarking

Table 2: Performance Characteristics in Drug Discovery Applications

| Performance Metric | 3D-QSAR | Molecular Docking |

|---|---|---|

| Handling of Novel Scaffolds | Limited to chemical space of training set | Can potentially identify novel scaffolds |

| Accuracy for Target Prediction | High within similar chemotypes | Variable; depends on scoring function accuracy |

| Computational Efficiency | High once model is built | Computationally intensive for large libraries |

| Interpretability | Intuitive contour maps for chemists | Detailed atomic-level interaction diagrams |

| Applicability Domain | Defined by training set diversity | Limited by available protein structures |

Recent benchmarking studies highlight the complementary strengths of these approaches. A 2025 systematic comparison of target prediction methods found that hybrid strategies often yield superior results [13]. For instance, machine learning-guided docking screens have demonstrated the ability to reduce computational costs by more than 1,000-fold when screening ultralarge compound libraries [5].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard 3D-QSAR Implementation Protocol

Data Curation and Preparation

- Assemble a congeneric series of compounds with uniform biological activity data

- Ensure consistent assay conditions and measurements

- Divide dataset into training and test sets

Molecular Modeling and Conformational Analysis

- Generate 3D structures from 2D representations

- Conduct geometry optimization using molecular mechanics or quantum mechanical methods

- Determine putative bioactive conformations

Molecular Alignment

- Select appropriate alignment strategy

- Superimpose molecules using shared scaffolds or field-based similarity

- Validate alignment quality

Descriptor Calculation

- Place aligned molecules in a 3D grid

- Compute steric and electrostatic fields

- Calculate additional fields for CoMSIA

Model Building and Validation

- Apply PLS regression to establish structure-activity relationship

- Conduct cross-validation

- Validate with external test set

Model Interpretation and Application

- Generate 3D contour maps

- Interpret favorable/unfavorable regions

- Design new analogs based on contour insights

Integrated 3D-QSAR and Docking Protocol

Recent studies demonstrate the power of integrating 3D-QSAR with molecular docking and molecular dynamics. A 2023 study on PLK1 inhibitors exemplifies this approach [12]:

- Initial 3D-QSAR Modeling: Develop CoMFA and CoMSIA models using a training set of pteridinone derivatives

- Molecular Docking: Dock compounds into the target protein active site

- Consensus Analysis: Compare 3D-QSAR contour maps with docking poses

- Molecular Dynamics Validation: Assess binding stability through MD simulations

- ADMET Profiling: Evaluate drug-like properties of promising candidates

This integrated protocol leverages the statistical power of 3D-QSAR with the mechanistic insights of structure-based methods, providing a comprehensive computational assessment.

Visualization and Data Interpretation

3D-QSAR Workflow and Integration with Docking

Figure 1: Integrated 3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking Workflow. The parallel implementation of both methods provides complementary insights for compound optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for 3D-QSAR and Docking Studies

| Tool Category | Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | SYBYL, RDKit, OpenBabel | 3D structure generation and optimization |

| Force Fields | Tripos Force Field, MMFF94, AMBER | Molecular mechanics calculations |

| QSAR Software | CoMFA, CoMSIA, SOMFA | Molecular field calculation and analysis |

| Docking Programs | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, GLIDE, DOCK | Protein-ligand docking simulations |

| Cheminformatics | Dragon, PaDEL, CheS-Mapper | Molecular descriptor calculation and visualization |

| Statistical Analysis | Partial Least Squares, PCA | Chemometric modeling and validation |

3D-QSAR and molecular docking represent complementary rather than competing approaches in computational drug discovery. 3D-QSAR excels in providing interpretable design guidance through contour maps and efficiently exploring chemical space around known actives [9]. Molecular docking offers mechanistic insights into binding interactions and the potential to identify novel scaffolds [2].

The emerging trend of hybrid methodologies combines the strengths of both approaches, as demonstrated in recent studies where 3D-QSAR contour maps inform docking analyses and vice versa [12]. Furthermore, the integration of machine learning with both 3D-QSAR and docking presents promising avenues for enhancing predictive accuracy and efficiency, particularly for navigating ultralarge chemical spaces [5] [14].

For researchers embarking on drug discovery projects, the selection between these methods should be guided by available data, project goals, and target knowledge. When structural information is available, integrated approaches leveraging both 3D-QSAR and docking provide the most comprehensive computational strategy for rational drug design.

Molecular docking is a foundational computational technique in structural biology and drug discovery that predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (typically a protein) [15]. The primary goal is to predict the three-dimensional structure of a ligand-protein complex and estimate the binding affinity, which is crucial for identifying potential drug candidates [16]. The technique has evolved significantly since its inception in the 1980s, driven by advances in computational power and algorithmic sophistication [15] [17]. Modern docking protocols address two fundamental challenges: efficiently exploring the vast conformational space of the ligand-receptor system (handled by search algorithms) and accurately ranking these conformations by their predicted binding affinity (handled by scoring functions) [18] [15].

In the broader context of benchmarking 3D-QSAR models against molecular docking results, understanding docking fundamentals becomes paramount. While 3D-QSAR models like CoMFA and CoMSIA correlate molecular field properties with biological activity without explicit receptor structure, molecular docking provides atomistic insights into binding interactions when protein structures are available [12]. This comparative framework enables researchers to validate and integrate both approaches for more reliable drug discovery pipelines.

Conformational Search Algorithms

Search algorithms systematically explore the possible orientations and conformations of the ligand within the protein's binding site [17]. The enormous degrees of freedom make exhaustive sampling computationally prohibitive, necessitating efficient search strategies [19]. These algorithms are broadly categorized into systematic, stochastic, and deterministic methods.

Systematic Search Methods

Systematic methods incrementally explore the conformational space by varying the ligand's structural parameters. These include:

- Conformational Search: Gradually changes torsional (dihedral), translational, and rotational degrees of freedom of the ligand's structural parameters [17].

- Fragmentation Methods: Dock multiple fragments either by forming bonds between them or anchoring them separately, with the first fragment docked initially and subsequent fragments built outward incrementally [17]. Tools implementing this approach include FlexX, DOCK, and LUDI [17].

- Database Search: Generates numerous reasonable conformations of small molecules pre-recorded in databases and docks them as rigid bodies using tools like FLOG [17].

Stochastic and Genetic Algorithms

Stochastic methods introduce randomness to efficiently navigate the vast conformational landscape:

- Monte Carlo Algorithms: Randomly place ligands in the receptor binding site, score the configuration, then generate new random configurations [17]. Implementations include MCDOCK and ICM [17].

- Genetic Algorithms (GA): Treat each spatial arrangement as a "gene" with energy as "fitness" [19]. Starting with a population of poses, the fittest undergo transformations and crossovers to produce subsequent generations [19] [17]. Popular GA-based docking programs include GOLD and AutoDock [19] [17]. These methods successfully sample large conformational spaces while maintaining biological relevance, though they may require multiple runs for reliability [19].

- Tabu Search: Avoids revisiting previously explored areas of the ligand's conformational space by implementing restrictions that facilitate investigation of fresh configurations [17]. Tools include PRO LEADS and Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD) [17].

Shape Complementarity and Molecular Dynamics Approaches

- Shape-Complementarity Methods: Focus on geometric and chemical complementarity between receptor and ligand [19]. These approaches use structural descriptors (solvent-accessible surface area, overall shape) and binding complementarity features (hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts) to quickly match potential compounds [19]. Implementations include DOCK, FRED, GLIDE, SURFLEX, eHiTS, and others [19]. These methods are highly efficient for virtual screening applications [19].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Typically hold proteins rigid while allowing ligands to explore conformational space through simulated annealing protocols [19]. Generated conformations are successively docked into the protein, with MD energy minimization steps and energies used for ranking [19]. Although computationally expensive, MD advantages include using standard force fields without specialized scoring functions and producing poses comparable with experimental structures [19]. Coarse-grained dynamics approaches like Distance Constrained Essential Dynamics (DCED) generate eigenstructures for docking while avoiding most costly MD calculations [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Conformational Search Algorithm Categories

| Algorithm Type | Key Features | Representative Software | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic | Incrementally explores degrees of freedom | FlexX, DOCK, LUDI, FLOG | Comprehensive sampling of defined space | Computationally demanding for flexible molecules |

| Stochastic/Genetic | Uses randomness and population-based evolution | GOLD, AutoDock, MCDOCK, ICM | Effective exploration of large spaces; biological relevance | May require multiple runs; longer computation time |

| Shape Complementarity | Focuses on geometric and chemical fit | DOCK, GLIDE, SURFLEX, FRED | High efficiency for virtual screening | May oversimplify molecular flexibility |

| Molecular Dynamics | Simulates physical movements over time | Various MD packages | Physically realistic sampling; standard force fields | Computationally expensive; not for large libraries |

Scoring Functions

Scoring functions are mathematical models that predict the binding affinity of protein-ligand complexes by calculating interaction energies [20]. They serve two critical purposes: guiding the search algorithm toward native-like binding modes and ranking final poses by predicted affinity [16]. Inaccuracies in scoring remain a major challenge in molecular docking [21].

Classical Scoring Function Categories

Traditional scoring functions fall into three main categories:

- Force-Field Based: Calculate binding affinity using classical mechanical force fields that sum contributions from non-bonded interactions including van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and Coulombic electrostatics, along with bond angle and torsional deviations [21] [17]. Tools include AutoDock, DOCK, and GoldScore [17]. These methods have high physical fidelity but substantial computational costs [21].

- Empirical-Based: Estimate binding affinity by summing weighted energy terms parameterized through linear regression against experimentally measured affinities [21] [20]. Terms describe key contributions like hydrogen bonding, ionic and hydrophobic interactions, and loss of ligand flexibility [20]. Implementations include LUDI score, ChemScore, and the London dG, ASE, Affinity dG, and Alpha HB functions in MOE software [20] [17]. These offer simpler computation and faster speeds compared to physics-based methods [21].

- Knowledge-Based: Derive statistical potentials from structural databases of known protein-ligand complexes through Boltzmann inversion of pairwise atom distances [21] [17]. These functions, including Potential of Mean Force (PMF) and DrugScore, offer a balance between accuracy and speed [21] [17].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Scoring

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches represent a paradigm shift in scoring function development [16] [21] [5]. Rather than using explicit empirical or mathematical functions, ML/DL models learn complex mapping functions from combinations of interface features, energy terms, and structural descriptors [21]. These methods can capture subtle patterns missed by classical functions [16].

Recent innovations include gradient boosting models like CatBoost, deep neural networks, and transformer architectures that achieve superior performance in virtual screening [5]. For example, one study demonstrated that ML-guided docking could reduce the computational cost of screening ultralarge libraries (3.5 billion compounds) by more than 1,000-fold while maintaining sensitivity values above 0.87 [5].

Performance Benchmarking

Comparative assessments reveal significant performance variations among scoring functions. A 2025 pairwise comparison of five MOE scoring functions using InterCriteria Analysis on the CASF-2013 benchmark found that Alpha HB and London dG showed the highest comparability, with the lowest RMSD being the best-performing docking output [22] [20]. The study highlighted substantial dissonance between different scoring functions, underscoring the challenge of selecting optimal functions for specific targets [20].

Comprehensive evaluations across seven public datasets indicate that while classical methods offer interpretability, ML/DL approaches generally achieve superior ranking accuracy, though with increased computational demands and potential dataset dependency issues [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Scoring Function Types with Performance Characteristics

| Scoring Type | Theoretical Basis | Representative Examples | Speed | Accuracy Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force-Field | Classical mechanics, molecular forces | AutoDock, DOCK, GoldScore | Slow | High physical fidelity but limited solvation treatment |

| Empirical | Linear regression of experimental data | LUDI, ChemScore, London dG, Alpha HB | Fast | Dependent on training data quality; may overfit |

| Knowledge-Based | Statistical potentials from databases | PMF, DrugScore | Medium | Good balance of speed and accuracy for diverse targets |

| Machine Learning | Pattern recognition from complex features | CatBoost, Deep Neural Networks, RoBERTa | Varies (fast prediction, slow training) | High potential accuracy; risk of dataset bias |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Standard Docking Validation Protocol

Rigorous validation is essential for reliable docking results. A standard protocol involves:

- Dataset Preparation: Curate high-quality protein-ligand complexes with known binding affinities and structures. The CASF-2013 benchmark subset of the PDBbind database, containing 195 diverse protein-ligand complexes, is widely used [20].

- Re-docking: Extract the native ligand from each complex and re-dock it into the prepared protein structure [20].

- Pose Generation: Generate multiple ligand poses (typically 20-30) for each complex using selected search algorithms [20].

- Pose Evaluation: Calculate RMSD between predicted poses and the experimental crystal structure to assess geometric accuracy [20].

- Scoring Function Assessment: Evaluate scoring functions based on their ability to identify native-like poses (RMSD ≤ 2.0 Å) as top-ranked and correlate predicted scores with experimental binding affinities [20].

InterCriteria Analysis Methodology

A sophisticated multi-criterion approach for scoring function comparison involves:

- Data Collection: For each protein-ligand complex, extract multiple docking outputs: best docking score (BestDS), lowest RMSD between predicted and crystallized ligand (BestRMSD), RMSD between best-docking-score pose and crystallized ligand (RMSDBestDS), and docking score of the pose with lowest RMSD (DSBestRMSD) [20].

- Matrix Formation: Format data with protein-ligand complexes as objects and different scoring function outputs as criteria [20].

- Threshold Application: Apply InterCriteria analysis with defined consonance (α = 0.75) and dissonance (β = 0.25) thresholds to determine degrees of agreement between scoring functions [20].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Investigate impact of varying α and β values on the relations between scoring functions [20].

- Correlation Analysis: Juxtapose ICrA results with traditional correlation metrics for validation [20].

Machine Learning-Guided Docking Workflow

For ultralarge library screening, an integrated ML-docking protocol enables efficient exploration:

- Training Set Docking: Conduct molecular docking of 1 million randomly selected compounds against the target protein [5].

- Classifier Training: Train machine learning classifiers (e.g., CatBoost with Morgan2 fingerprints) to identify top-scoring compounds based on docking results [5].

- Conformal Prediction: Apply the conformal prediction framework with Mondrian CP to make statistically valid selections from multi-billion-scale libraries [5].

- Focused Docking: Perform molecular docking only on the predicted virtual active set, typically reducing the screening library by 1,000-fold [5].

- Experimental Validation: Test top-ranked compounds in biochemical or cellular assays to confirm activity [5].

Visualization of Key Workflows

Molecular Docking Decision Pathway

ML-Accelerated Docking Screening

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Docking Research

| Tool Category | Representative Software | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Docking Suites | AutoDock/Vina, GOLD, MOE, Glide | Integrated search algorithms and scoring functions | General docking studies, virtual screening |

| Scoring Function Assessment | CCharPPI server | Evaluate scoring functions independent of docking | Benchmarking scoring function performance |

| Machine Learning Classifiers | CatBoost, Deep Neural Networks, RoBERTa | Predict top-scoring compounds from chemical features | ML-guided docking for ultralarge libraries |

| Validation & Analysis | DockBench, InterCriteria Analysis | Validate docking protocols, compare scoring functions | Method validation and performance benchmarking |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, PyRosetta | Assess binding stability, refine docking poses | Post-docking refinement and stability analysis |

| 3D-QSAR Integration | SYBYL-X | Develop comparative molecular field models | Correlation with docking results for validation |

Molecular docking remains an indispensable tool in computational drug discovery, with its effectiveness hinging on the careful selection and application of conformational search algorithms and scoring functions. Search algorithms span systematic, stochastic, and shape-based approaches, each with distinct strengths in balancing computational efficiency with sampling comprehensiveness. Scoring functions have evolved from classical force-field, empirical, and knowledge-based methods to increasingly sophisticated machine learning approaches that offer enhanced predictive accuracy.

Benchmarking studies reveal that performance varies significantly across methods and target classes, necessitating rigorous validation protocols like InterCriteria Analysis and standardized docking benchmarks. The integration of machine learning with traditional docking has enabled the screening of ultralarge chemical libraries previously considered intractable, representing a major advance for early drug discovery.

For researchers benchmarking 3D-QSAR models against docking results, understanding these fundamentals provides the foundation for meaningful comparisons. The complementary nature of these approaches - with QSAR identifying key molecular features and docking providing structural insights - creates a powerful framework for rational drug design when both are properly implemented and validated.

In modern computational drug discovery, Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) and molecular docking serve as foundational techniques for predicting compound activity and optimizing lead molecules. While both aim to elucidate the relationship between molecular structure and biological function, they operate on fundamentally different principles and excel in distinct application scenarios. 3D-QSAR methodologies, including Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), are ligand-based approaches that correlate the spatial distribution of molecular properties with biological activity without requiring explicit structural knowledge of the target protein [23] [24]. In contrast, molecular docking is a structure-based technique that predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target protein receptor, requiring detailed 3D structural information of the binding site [25] [24].

The integration of these methods has become increasingly common in rational drug design, with each approach providing complementary insights. This comparative analysis examines their respective strengths, limitations, and optimal application domains based on current benchmarking studies, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for method selection in specific drug discovery contexts.

Fundamental Principles of 3D-QSAR

3D-QSAR techniques model biological activity based on the three-dimensional molecular fields of aligned compounds. The core assumption is that differences in biological activity correlate with changes in the shapes and strengths of non-covalent interaction fields surrounding the molecules [23]. CoMFA, the pioneering 3D-QSAR method, calculates steric and electrostatic interaction fields using a probe atom placed at grid points surrounding the molecules [24]. CoMSIA extends this approach by incorporating a broader range of molecular fields—steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor—and uses a Gaussian function to calculate molecular similarity indices, resulting in more continuous field distributions and reduced sensitivity to molecular alignment [26] [24].

A significant advancement in 3D-QSAR accessibility is the recent development of open-source implementations like Py-CoMSIA, which provides a Python-based alternative to previously proprietary software platforms, broadening access to these methodologies [26]. 3D-QSAR models are typically constructed using partial least squares (PLS) regression and validated through both internal (e.g., leave-one-out cross-validation) and external validation techniques to ensure predictive reliability [27].

Fundamental Principles of Molecular Docking

Molecular docking aims to predict the stable binding conformation and orientation of a ligand within a protein's binding site, along with estimating the binding affinity through scoring functions [25]. Traditional docking tools consist of two key components: a conformational search algorithm that explores possible ligand orientations and conformations, and a scoring function that estimates the binding energy for each pose [25]. These scoring functions can be physics-based (estimating force field energies), empirical (using weighted interaction terms), or knowledge-based (derived from statistical analyses of protein-ligand complexes) [22].

Recently, deep learning (DL) approaches have introduced new paradigms to molecular docking, including generative diffusion models that directly generate binding poses, regression-based models that predict binding energies, and hybrid methods that combine traditional conformational searches with AI-driven scoring functions [25]. These DL methods leverage extensive training datasets to learn complex patterns in protein-ligand interactions, potentially overcoming limitations of traditional physics-based approaches.

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between 3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking

| Feature | 3D-QSAR | Molecular Docking |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Requirement | Requires only ligand structures and activities | Requires 3D structure of protein target |

| Molecular Alignment | Critical step; depends on ligand superposition | Automatic during docking process |

| Primary Output | Predictive activity model and contour maps | Binding pose and affinity estimation |

| Field Descriptors | Steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, H-bond donor/acceptor | Van der Waals, electrostatic, hydrogen bonding, desolvation |

| Statistical Foundation | PLS regression on molecular field descriptors | Search algorithms and scoring functions |

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Predictive Accuracy and Applicability Domain

Comprehensive benchmarking reveals distinctive performance patterns for 3D-QSAR and molecular docking across different evaluation metrics and application scenarios. For 3D-QSAR, validation studies demonstrate strong predictive capability within well-defined congeneric series, with reported q² values (cross-validated correlation coefficient) of 0.569-0.665 and r² values (coefficient of determination) of 0.898-0.937 in validated CoMSIA models [3] [26]. These models excel in lead optimization contexts where compounds share structural similarities and the focus is on relative activity prediction rather than absolute binding affinity.

Molecular docking performance varies significantly based on method selection and system characteristics. Traditional docking methods like Glide SP demonstrate high physical validity, maintaining PB-valid rates (assessing chemical and geometric plausibility) above 94% across diverse datasets [25]. However, pose prediction accuracy differs substantially between methods: generative diffusion models such as SurfDock achieve high RMSD ≤ 2Å success rates (exceeding 70% across benchmarks), while regression-based DL methods often produce physically implausible structures despite favorable RMSD scores [25].

Strengths and Limitations in Practical Applications

Table 2: Comparative Strengths and Weaknesses of 3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking

| Aspect | 3D-QSAR | Molecular Docking |

|---|---|---|

| Key Strengths | • Does not require protein structure• Excellent for congeneric series• Provides interpretable contour maps• Identifies key molecular features driving activity | • Provides atomic-level interaction details• Can handle structurally diverse compounds• Reveals binding mode hypotheses• Suitable for virtual screening |

| Major Limitations | • Dependent on molecular alignment• Limited to congeneric series• Cannot propose new binding modes• Requires significant experimental data for training | • Scoring function inaccuracies• Protein flexibility challenges• High computational cost for large libraries• Sensitivity to input preparation |

| Optimal Applications | Lead optimization, SAR analysis, molecular feature optimization | Virtual screening, binding mode prediction, structure-based design |

The benchmarking data reveals that 3D-QSAR models provide exceptional value in lead optimization stages where medicinal chemists need guidance on which molecular features to modify to enhance potency [28]. The contour maps generated by CoMSIA analyses directly visualize regions where increased steric bulk, enhanced electronegativity, or modified hydrophobic character would improve activity, making these models highly interpretable for chemistry teams [26] [24].

Molecular docking excels in virtual screening applications where the goal is to identify novel hit compounds from large chemical libraries, though performance varies significantly between methods. Traditional physics-based docking demonstrates robust generalization across novel protein binding pockets, while some DL docking methods exhibit performance degradation when encountering proteins with low sequence similarity to training data [25]. For binding pose prediction, traditional methods and hybrid AI approaches currently provide the best balance between accuracy and physical plausibility [25].

Integrated Workflows and Experimental Protocols

Standardized Methodological Approaches

Successful application of these computational techniques requires adherence to standardized protocols and validation procedures. For 3D-QSAR studies, the established workflow involves:

- Data Curation: Compiling a congeneric series of compounds with consistent biological activity measurements [27]

- Molecular Modeling: Generating 3D structures using quantum mechanical methods (e.g., DFT with M06-2X functional) and establishing molecular alignment rules [23]

- Descriptor Calculation: Computing molecular interaction fields using standard probes and grid parameters (typically 1-2Å spacing) [26]

- Model Development: Applying PLS regression with appropriate component selection based on cross-validation statistics [27]

- Model Validation: Implementing both internal (leave-one-out, leave-many-out) and external validation (training/test set splits) following OECD guidelines [23] [27]

For molecular docking, the standard protocol encompasses:

- Protein Preparation: Processing the protein structure (removing water molecules, adding hydrogens, assigning protonation states) [25]

- Binding Site Definition: Identifying and preparing the binding pocket (often from co-crystallized ligands or computational prediction) [25]

- Ligand Preparation: Generating 3D structures, tautomers, and protonation states for small molecules [22]

- Docking Execution: Performing conformational sampling using appropriate search algorithms [25]

- Pose Selection and Scoring: Analyzing results based on both scoring function values and structural rationality [22]

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated application of these methods in drug discovery:

Integrated Drug Discovery Workflow Combining 3D-QSAR and Docking

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Solutions for 3D-QSAR and Docking Studies

| Category | Tool/Solution | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-QSAR Software | Py-CoMSIA [26] | Open-source CoMSIA implementation | 3D-QSAR model development |

| Sybyl/QSARINS [23] [27] | Commercial 3D-QSAR platforms | Molecular field analysis and validation | |

| Docking Suites | Glide SP [25] | Traditional docking with high validity | Structure-based virtual screening |

| AutoDock Vina [25] | Efficient conformational search | Rapid docking of compound libraries | |

| SurfDock/DiffBindFR [25] | Deep learning docking methods | High-accuracy pose prediction | |

| Validation Tools | PoseBusters [25] | Physical plausibility assessment | Docking pose validation |

| QSARINS [27] | Statistical validation | QSAR model robustness testing | |

| Data Resources | ChEMBL [28] | Compound activity database | Training data for model development |

| PDBbind [22] [28] | Protein-ligand complex structures | Benchmarking docking methods |

The comparative analysis of 3D-QSAR and molecular docking reveals distinct but complementary roles in computational drug discovery. The selection between these methods should be guided by specific research objectives, available structural information, and the stage of the drug discovery pipeline.

3D-QSAR approaches provide maximum value in lead optimization campaigns where congeneric series are available and the research goal is to understand which specific molecular features modulate biological activity. The method's strength lies in its interpretability—the generated contour maps directly inform medicinal chemists which structural modifications are likely to enhance potency. Recent open-source implementations have increased accessibility to these methodologies, though careful attention to validation remains critical for reliable predictions [27] [26].

Molecular docking methods offer unique advantages in scenarios where protein structural information is available and the research requires understanding atomic-level interactions or screening structurally diverse compound collections. Traditional docking methods currently provide more consistent performance across novel protein targets, while specialized DL docking approaches can achieve superior pose accuracy for specific target classes [25]. The choice between traditional and AI-driven docking should consider the trade-offs between physical plausibility, accuracy, and generalization capability.

For comprehensive drug discovery programs, integrated workflows that leverage both techniques provide the most robust approach—using docking for initial binding mode analysis and virtual screening, followed by 3D-QSAR modeling to guide systematic optimization of lead compounds. This synergistic application capitalizes on the distinct strengths of each method while mitigating their individual limitations, ultimately accelerating the rational design of therapeutic agents.

The Synergistic Potential of an Integrated Approach

In modern computational drug discovery, 3D-QSAR and molecular docking have emerged as cornerstone methodologies. Traditionally applied independently, their integration presents a powerful synergistic potential for enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of lead compound identification and optimization. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these techniques, benchmarking their performance when used in isolation versus a unified workflow.

3D-QSAR models quantitatively correlate the three-dimensional molecular field properties of compounds with their biological activity. Molecular docking predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule within a protein's active site. While 3D-QSAR excels at revealing structural features crucial for potency, molecular docking provides atomic-level insights into protein-ligand interactions. The convergence of these approaches offers a more comprehensive framework for structure-based drug design, enabling researchers to overcome the limitations inherent in each method when used alone [29] [30].

Performance Benchmarking: Isolated vs. Integrated Approaches

Performance Metrics of Individual Methods

Table 1: Performance benchmarks for 3D-QSAR and molecular docking methodologies.

| Methodology | Specific Approach | Key Performance Metrics | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-QSAR | CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis) | q² = 0.569, r² = 0.915, SEE = 0.109, F = 52.714 [29] | Lead optimization for MAO-B inhibitors [29] |

| 3D-QSAR | CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) | R² = 0.992, Q² = 0.67, R²pred = 0.683 [30] | PLK1 inhibitor development for cancer [30] |

| Molecular Docking | Traditional (Glide SP) | High physical validity (PB-valid rate >94%), robust performance [25] | Pose prediction for known binding pockets |

| Molecular Docking | Deep Learning (SurfDock - Diffusion) | High pose accuracy (RMSD ≤2Å success rate >70%), lower physical validity [25] | Blind docking and pose generation |

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

3D-QSAR Strengths and Gaps: Statistically robust 3D-QSAR models, like the CoMSIA model for MAO-B inhibitors, demonstrate excellent predictive ability for designing novel derivatives with improved activity [29]. However, these models operate as "black boxes" and do not explicitly visualize the ligand's binding mode or specific interactions with the protein target, which is a significant limitation for rational drug design.

Molecular Docking Capabilities and Challenges: Molecular docking directly addresses the limitation of 3D-QSAR by providing atomic-level insight into binding interactions. Recent benchmarking reveals a performance spectrum: traditional methods like Glide SP excel in producing physically valid poses (PB-valid rate >94%), while deep learning generative models like SurfDock achieve superior pose accuracy (RMSD ≤2Å success rate >75%) though sometimes at the cost of physical plausibility [25]. A critical challenge for most docking methods is handling protein flexibility, often treating the receptor as rigid, which can limit accuracy in real-world scenarios where induced fit occurs [31].

Integrated Workflow: A Practical Protocol

Sequential Integration Methodology

The synergistic potential of 3D-QSAR and molecular docking is maximized through a sequential, iterative workflow. This integrated approach has been successfully validated in recent studies on diverse targets, including MAO-B and PLK1 inhibitors [29] [30].

Diagram: Integrated 3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking Workflow

Workflow Implementation:

3D-QSAR Model Construction and Validation: Begin with a training set of compounds with known biological activities (e.g., IC50 values). Construct 3D-QSAR models using methods like CoMFA or CoMSIA. Critical steps include molecular alignment and field calculation. Validate model robustness using cross-validated correlation coefficient (q² > 0.5) and predictive r² for test set compounds (R²pred > 0.6) [30].

Design and Activity Prediction: Use the contour maps from the validated 3D-QSAR model to guide the design of novel derivatives. Predict the biological activities of these newly designed compounds in silico to prioritize those with the highest predicted potency [29].

Molecular Docking and Interaction Analysis: Subject the prioritized compounds to molecular docking into the target protein's binding site. This step confirms the binding mode and identifies key amino acid residues (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, electrostatic interactions) that stabilize the complex [29] [30].

Stability Validation via Molecular Dynamics (MD): Perform MD simulations (typically 50-100 ns) on the top-ranked docked complexes. Analyze root mean square deviation (RMSD) and residue decomposition energy to evaluate the stability of binding under dynamic, physiological conditions [29] [32]. For instance, stable complexes for MAO-B inhibitors showed RMSD fluctuations between 1.0-2.0 Å [29].

Iterative Refinement: The insights from docking and MD regarding unfavorable interactions or suboptimal binding can be fed back to refine the compound structures, creating a powerful design loop [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key software and resources for integrated computational analysis.

| Tool Category | Representative Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling & QSAR | Sybyl-X, ChemDraw [29] | Compound construction, minimization, and 3D-QSAR model generation (CoMFA/CoMSIA) |

| Molecular Docking | Glide SP, AutoDock Vina [25] [30] | Prediction of protein-ligand binding conformation and scoring |

| Deep Learning Docking | SurfDock, DiffDock, DynamicBind [25] [31] | AI-powered pose prediction, particularly for flexible docking or cryptic pockets |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER [29] | Simulation of protein-ligand complex stability under physiological conditions |

| Protein Data Source | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [30] | Source of experimentally solved 3D protein structures for docking studies |

| Compound Activity Database | ChEMBL, BindingDB [28] | Public repositories of bioactivity data for model training and validation |

Case Studies in Integrated Drug Discovery

Neuroprotective Agent Development

In a 2025 study on Monoamine Oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors for neurodegenerative diseases, researchers developed a highly predictive CoMSIA model (q²=0.569, r²=0.915). The model guided the design of novel 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives. The top-designed compound, 31.j3, was then evaluated by molecular docking, achieving a high docking score. Subsequent MD simulations confirmed stable binding (RMSD 1.0-2.0 Å) with the MAO-B receptor, with energy decomposition highlighting the critical role of van der Waals and electrostatic interactions. This integrated workflow systematically transformed a QSAR prediction into a validated, promising candidate [29].

Oncology Target Inhibition

A study on Pteridinone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors for prostate cancer established multiple robust 3D-QSAR models (CoMFA: Q²=0.67, R²=0.992). The models successfully predicted active compounds, which were then docked into the PLK1 active site (PDB: 2RKU). Docking revealed critical interactions with residues R136, R57, and Y133. MD simulations over 50 ns reinforced the docking results, showing that the top inhibitors remained stable in the binding site. This multi-technique approach ensured that the compounds were optimized not just for predicted activity, but also for stable target engagement [30].

The benchmarking data and case studies presented demonstrate that an integrated approach of 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation is markedly superior to the application of any single method. While 3D-QSAR provides a powerful predictive map for activity, and docking offers structural insights, their synergy creates a rational feedback loop that accelerates and de-risks the drug discovery process. For researchers aiming to develop potent and selective therapeutic agents, this unified computational strategy represents a best-practice protocol, effectively bridging the gap between predictive modeling and mechanistic validation.

Implementing Integrated Workflows: From Model Building to Collaborative Application

Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling represents a pivotal methodology in modern computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to correlate the spatial and physicochemical properties of molecules with their biological activity. Among these techniques, Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) have emerged as cornerstone approaches for rational drug design. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, detailing experimental protocols, benchmarking data against established alternatives, and introducing modern implementations that address current accessibility challenges. The content is framed within a broader research context that emphasizes the integration and benchmarking of 3D-QSAR models against molecular docking results, providing researchers with a holistic framework for computational drug development.

Theoretical Background and Methodological Comparison

Core Principles of CoMFA and CoMSIA

CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis), introduced by Cramer et al. in 1988, operates on the fundamental principle that biological activity differences between molecules can be explained by their steric and electrostatic interaction fields with a common receptor [33]. The method calculates Lennard-Jones (steric) and Coulombic (electrostatic) potentials using probe atoms at regularly spaced grid points surrounding pre-aligned molecules [33] [34]. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is then employed to correlate these field values with biological activity, generating predictive models and visual contour maps that guide molecular optimization.

CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis), developed by Klebe et al. in 1994, extends beyond CoMFA by incorporating additional physicochemical fields and utilizing a Gaussian-type distance-dependent function [26]. This approach calculates similarity indices for five distinct molecular fields: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor [26] [34]. The Gaussian function eliminates singularities at atomic positions and reduces sensitivity to molecular alignment, addressing key limitations of the CoMFA approach [26].

Key Methodological Differences

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between CoMFA and CoMSIA Approaches

| Parameter | CoMFA | CoMSIA |

|---|---|---|

| Fields Used | Steric, Electrostatic | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-bond Donor, H-bond Acceptor |

| Calculation Function | Lennard-Jones & Coulomb potentials | Gaussian-type distance function |

| Cutoff Limits | Required (typically 30 kcal/mol) | Not required |

| Alignment Sensitivity | High | Moderate |

| Hydrophobic Interactions | Not directly modeled | Explicitly included |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Indirectly via electrostatic fields | Explicit donor and acceptor fields |

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Validation Against Established Benchmarking Datasets

Rigorous benchmarking studies have demonstrated the predictive performance of CoMFA and CoMSIA across diverse molecular systems. A comprehensive evaluation using the Sutherland datasets—eight frequently utilized datasets for 3D-QSAR benchmarking—showed that modern 3D-QSAR implementations perform comparably to or better than established methods [35].

Table 2: Performance Comparison (COD Values) Across Sutherland Datasets

| Dataset | CoMFA | CoMSIA Basic | CoMSIA Extra | 3D Model (This Work) | Open3DQSAR | QMOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.69 | 0.32 |

| ACHE | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.56 |

| BZR | 0.0 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.27 |

| COX2 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.22 |

| DHFR | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.6 | 0.46 |

| GPB | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.5 | 0.46 |

| THERM | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.39 |

| THR | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.42 |

| Average | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.39 |

The averaged Coefficient of Determination (COD) values across these datasets reveal that the 3D models developed in contemporary work (COD=0.52) outperform traditional CoMFA (COD=0.43) and CoMSIA basic (COD=0.37), while performing on par with more recently developed methods like Open3DQSAR (COD=0.52) [35].

BACE-1 Inhibitors Case Study

A comparative study on β-secretase 1 (BACE-1) inhibitors further validates the performance of modern 3D-QSAR approaches. The study utilized a dataset of 1478 uncharged ligands with conformers from literature, divided into training (205 ligands) and validation (1273 ligands) sets [35]. The results demonstrated that contemporary 3D-QSAR implementations can achieve Kendall's tau values of 0.49 and Pearson's r² values of 0.53, slightly outperforming best-performing third-party software including CoMFA (tau=0.45, r²=0.47) and comparable approaches from other platforms [35].

Integration with Molecular Docking and Dynamics

The true predictive power of 3D-QSAR models is enhanced when integrated with molecular docking and dynamics simulations. A study on TTK inhibitors demonstrated that structure-based alignment combined with MMFF94 charges yielded highly predictive CoMFA (q²=0.583, Predr²=0.751) and CoMSIA (q²=0.690, Predr²=0.767) models [34]. Subsequent molecular dynamics simulations confirmed the stability of complexes with newly designed compounds, with RMSD values fluctuating between 1.0-2.0 Å, indicating strong conformational stability [3] [29].

Similarly, research on monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors showcased a CoMSIA model with excellent predictive statistics (q²=0.569, r²=0.915) that successfully guided the design of novel 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives [3] [29]. Molecular docking and dynamics simulations validated the binding stability of these designed compounds, demonstrating the complementary value of integrating 3D-QSAR with structure-based approaches [3] [29].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standardized CoMFA/CoMSIA Workflow

Detailed Protocol for CoMFA/CoMSIA Analysis

Step 1: Dataset Preparation and Molecular Modeling

- Compound Selection: Curate a structurally diverse set of compounds with consistent biological activity data (e.g., IC50, Ki). Typically, 20-30 compounds are required for reliable modeling [36] [34].

- Structure Optimization: Sketch 2D structures using chemical drawing tools (e.g., ChemDraw) and generate 3D conformations using molecular modeling software [3] [29].

- Energy Minimization: Perform geometry optimization using appropriate force fields (e.g., Tripos, MMFF94) with convergence criteria of 0.01 kcal/molÅ and gradient of 0.001 kcal/molÅ [34].

- Charge Calculation: Compute partial atomic charges using methods such as Gasteiger-Hückel, Gasteiger-Marsili, or MMFF94 charges [34].

Step 2: Molecular Alignment

- Template Selection: Identify the most active compound or a representative structure as the alignment template [34].

- Alignment Methods:

- Database Alignment: Align molecules based on common substructure using SYBYL database align routine [36].

- Structure-Based Alignment: Use docking poses or crystal structure complexes when available [34].

- Pharmacophore-Based Alignment: Align key pharmacophoric features identified from active molecules.

Step 3: Field Calculations and Model Development

- Grid Generation: Create a 3D grid with 2.0Å spacing that encompasses all aligned molecules with a 4.0Å margin in all directions [34].

- CoMFA Field Calculation:

- Use an sp³ carbon atom with +1.0 charge as probe

- Set steric and electrostatic energy cutoffs to 30 kcal/mol [34]

- Calculate Lennard-Jones (steric) and Coulomb (electrostatic) potentials

- CoMSIA Field Calculation:

- Use a probe atom with radius 1.0Å, charge +1, hydrophobicity +1

- Apply Gaussian function with attenuation factor α=0.3 [34]

- Calculate five fields: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, H-bond donor, H-bond acceptor

- Statistical Analysis:

Modern Implementation Tools

The recent development of Py-CoMSIA, an open-source Python implementation, addresses accessibility challenges posed by discontinued proprietary software like SYBYL [26]. This library utilizes RDKit and NumPy for calculations and PyVista for visualizations, providing comparable results to traditional SYBYL analyses while offering greater flexibility for integration with advanced statistical and machine learning techniques [26].

Validation studies using the steroid benchmark dataset demonstrated that Py-CoMSIA achieves performance metrics (q²=0.609, r²=0.917) comparable to original SYBYL implementations (q²=0.665, r²=0.937), confirming its utility as a viable open-source alternative [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Software for 3D-QSAR Modeling

| Tool/Software | Type | Primary Function | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sybyl-X/Tripos | Commercial Software | Traditional platform for CoMFA/CoMSIA | Discontinued, limited access |

| Schrödinger Suite | Commercial Software | Comprehensive drug discovery platform | Commercial license required |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Commercial Software | Molecular modeling and simulation | Commercial license required |

| Py-CoMSIA | Open-source Python Library | Open-source CoMSIA implementation | Freely accessible |

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics | Chemical informatics and machine learning | Freely accessible |

| CORAL Software | Open-source Tool | QSAR modeling with SMILES descriptors | Freely accessible |

This comparison guide demonstrates that robust 3D-QSAR models, particularly CoMFA and CoMSIA, remain powerful tools for quantitative drug design when implemented with rigorous protocols and validated against appropriate benchmarking standards. The integration of these approaches with molecular docking and dynamics simulations creates a comprehensive framework for structure-based drug discovery. The emergence of open-source implementations like Py-CoMSIA addresses previous accessibility barriers while maintaining methodological rigor. By adhering to the detailed protocols outlined in this guide and leveraging the comparative performance data provided, researchers can develop predictive 3D-QSAR models that effectively contribute to rational drug design efforts.

Molecular docking is a cornerstone of computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict how small molecules interact with target proteins. This guide provides a comparative analysis of leading docking software, detailing their performance in predicting binding poses and affinities, and outlines essential experimental protocols for robust docking simulations.

Software Performance: Pose Prediction and Virtual Screening

The accuracy of molecular docking software is typically evaluated by its ability to predict the correct binding pose (often defined by a root-mean-square deviation, RMSD, of ≤ 2 Å from the experimental structure) and its effectiveness in virtual screening (VS), which is measured by its ability to enrich active compounds over inactive ones [37] [25].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Leading Docking Software

| Software | Pose Prediction Success Rate (RMSD ≤ 2 Å) | Key Strengths | Virtual Screening Performance (AUC Range) | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glide | 100% (COX enzymes) [37], >94% PB-valid rate [25] | Superior pose accuracy, excellent physical plausibility [37] [25] | 0.61 - 0.92 [37] | High-accuracy pose prediction, lead optimization [37] [38] |

| GOLD | 59% - 82% (COX enzymes) [37] | High-performance scoring function, genetic algorithm [38] | N/A | Handling diverse protein-ligand complexes [38] |

| AutoDock Vina | Tiered performance behind Glide [25] | Fast, reliable, free & open-source [38] | N/A | General-purpose docking, budget-conscious projects [38] |

| SurfDock (Deep Learning) | >70% across diverse sets [25] | Exceptional pose accuracy via generative diffusion [25] | N/A | High-accuracy pose generation on known complex types [25] |

| FRED (OEDocking) | N/A | Ultra-fast exhaustive docking for VS [39] | N/A | Ultra-high-throughput virtual screening [39] |

As the data shows, Glide demonstrates top-tier performance in both pose prediction and physical plausibility across multiple benchmarks [37] [25]. For scenarios requiring extreme speed in virtual screening, such as processing ultra-large libraries, FRED from OEDocking is a specialized tool [39]. Emerging deep learning methods like SurfDock show remarkable pose accuracy but can sometimes produce physically implausible structures and struggle with generalization to novel protein pockets [25].

Experimental Protocols for Docking and Validation

A reliable docking study requires careful preparation and validation. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive protocol integrating docking with 3D-QSAR and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for robust results.

Protein and Ligand Preparation

Protein Preparation

- Source: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Structures with higher resolution (e.g., < 2.5 Å) are preferred [37].

- Refinement: Using software like DeepView or Schrodinger's Protein Preparation Wizard, remove redundant chains, crystallographic water molecules, and irrelevant cofactors [37] [32].

- Optimization: Add missing hydrogen atoms, assign bond orders, and optimize the hydrogen-bonding network. For structures lacking essential components, such as a heme group, these must be added back [37].

Ligand Preparation

- Construction: Draw or obtain the 2D structure of ligand molecules and convert them to 3D formats using tools like ChemDraw or Sybyl-X [29].

- Energy Minimization: Perform geometry optimization using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., MMFF94) to ensure the ligand is in a low-energy conformation [32].

Molecular Docking Execution

- Grid Generation: Define the docking search space by creating a grid box centered on the protein's binding site. The box size should be large enough to accommodate ligand movement [37].

- Pose Generation and Scoring: Run the docking simulation using the chosen software (e.g., Glide, GOLD, AutoDock Vina). These programs use search algorithms to generate multiple ligand poses and scoring functions to rank them based on predicted binding affinity [37] [2].

- Pose Validation: The primary validation metric is the RMSD between the docked pose and a known experimental (crystallographic) pose. An RMSD of ≤ 2.0 Å is generally considered a successful prediction [37] [25].

Advanced Validation: 3D-QSAR and MD Simulations

3D-QSAR Modeling

- Objective: To build a predictive model that correlates the 3D structural properties of a set of ligands with their biological activity (e.g., IC50) [29] [40].

- Method: Use techniques like Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA). A robust model is indicated by a high cross-validated correlation coefficient (e.g., q² > 0.5) and a high non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (e.g., r² > 0.8) [29].

- Integration with Docking: The contour maps generated by 3D-QSAR can reveal favorable and unfavorable chemical features around the ligands, providing insights to guide the design of new compounds and their subsequent docking studies [29] [32].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations