Analytical Validation of qPCR Assays in Clinical Cancer Diagnostics: A Guide from Foundations to GxP Compliance

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the analytical validation of quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays in clinical cancer diagnostics.

Analytical Validation of qPCR Assays in Clinical Cancer Diagnostics: A Guide from Foundations to GxP Compliance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the analytical validation of quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays in clinical cancer diagnostics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of qPCR in oncology, detailed methodological setup for applications like liquid biopsies and minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring, advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and rigorous validation protocols for regulated environments. By synthesizing current best practices and comparing qPCR with emerging technologies like digital PCR, this guide aims to support the development of robust, reliable, and clinically actionable molecular assays that are essential for personalized cancer therapy.

The Unwavering Role of qPCR in Modern Clinical Oncology

Why qPCR Remains a Cornerstone for Targeted Cancer Mutation Detection

In the rapidly evolving landscape of molecular diagnostics, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) maintains a fundamental position in targeted cancer mutation detection despite the emergence of sophisticated technologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS). Its persistence stems from a powerful combination of analytical sensitivity, operational efficiency, and economic practicality that remains unmatched for specific clinical applications. qPCR enables the detection of clinically actionable biomarkers at low concentrations while supporting molecular stratification for personalized therapy [1]. This technical guide objectively examines the performance characteristics of qPCR relative to alternative technologies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data and validation frameworks essential for implementing robust qPCR assays in cancer diagnostics.

The transformation of cancer diagnostics from late-stage diagnosis toward earlier detection and personalized treatment has intensified the need for technologies that can detect actionable biomarkers at low concentrations in limited sample material [1]. Within this context, qPCR continues to offer a compelling value proposition for targeted mutation detection, particularly in time-sensitive clinical scenarios and resource-constrained settings. The technology's robust performance characteristics, combined with ongoing innovations in chemistry and workflow integration, ensure its continued relevance in precision oncology.

Performance Comparison of Mutation Detection Technologies

The selection of an appropriate molecular detection platform requires careful consideration of analytical capabilities, operational parameters, and practical constraints. The table below provides a systematic comparison of qPCR against next-generation sequencing and digital PCR for key performance metrics relevant to cancer mutation detection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Mutation Detection Technologies in Cancer Diagnostics

| Performance Parameter | qPCR | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Digital PCR (dPCR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Sensitivity (VAF) | <0.1%–1% [1] | 1%–5% (standard); <1% (liquid biopsy) [2] | 0.08%–0.1% [3] [4] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Moderate (up to 11 genes) [5] | High (hundreds of genes) [6] | Limited (typically 3–5 targets) [4] |

| Turnaround Time | Hours (∼2–4 hours) [1] | Days (∼1–7 days) [3] [7] | Hours (∼3–6 hours) [4] |

| Cost Per Sample | $50–$200 [1] | $300–$3,000 [1] | $100–$300 (estimated) |

| Throughput | High (96/384-well formats) [1] | Variable (low to very high) [6] | Medium (limited by partitioning) [4] |

| Discovery Power | Limited to known variants [6] | High (hypothesis-free) [6] | Limited to known variants |

| Sample Input Requirements | Low (FFPE, cfDNA, fine needle aspirates) [1] | Moderate to high (depends on panel size) [5] | Low (comparable to qPCR) [4] |

| Quantification | Relative (Ct values) | Absolute (read counts) [2] | Absolute (molecular counting) [4] |

| Implementation Complexity | Low (standard equipment) [1] | High (specialized infrastructure) [7] | Medium (specialized equipment) |

qPCR demonstrates particular strength in clinical scenarios requiring rapid turnaround for a limited number of predefined targets, such as testing for EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer or KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer [1] [3]. The technology provides a practical balance between sensitivity, speed, and cost, making it suitable for both centralized reference laboratories and hospital-based molecular pathology facilities [1] [7].

Key Experimental Applications in Cancer Research

Multiplexed qPCR for Comprehensive Lung Cancer Genotyping

Advanced qPCR systems now enable simultaneous detection of multiple clinically relevant mutations in a single reaction, maximizing data yield from minimal input material—a critical advantage in tissue-limited cases.

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: DNA is extracted from various micro cell samples (MCSs) including puncture needle rinse samples and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid using the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit [5].

- qPCR Setup: Reactions are performed using the Lung Cancer 11-Gene Mutations Detection Kit on an Mx3000P PCR instrument [5].

- Thermal Cycling: Protocol-specific cycling conditions are applied with fluorescence detection at each cycle.

- Data Analysis: Threshold cycle (Ct) values are determined for each target, with positive calls made based on established cutoff values [5].

Performance Data: In a 2025 study analyzing 184 patients with suspected lung cancer, qPCR successfully detected mutations in 11 genes (including EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, ALK, ROS1) with 100% concordance between MCSs and paired tissue samples [5]. The methodology achieved a complete diagnostic turnaround time of only 24 hours, significantly shorter than the 5-7 days typically required for standard diagnostic pathways [5].

High-Sensitivity KRAS Mutation Detection Using LBDA Technology

The long blocker displacement amplification (LBDA) method represents an advanced qPCR-based approach for detecting low-frequency mutations with enhanced sensitivity.

Experimental Protocol:

- Primer/Blocker Design: A wild-type-specific nucleic acid blocker is designed to bind WT templates with higher affinity, suppressing their amplification while allowing mutant templates to be amplified [3].

- Reaction Setup: SYBR Green dye is incorporated to intercalate into accumulating double-stranded DNA products, generating a fluorescence signal proportional to mutant template abundance [3].

- Amplification Conditions: 50 cycles of: 98°C for 10s, 70°C for 30s, 72°C for 3min [3].

- Analysis: Fluorescence curves are analyzed to identify samples with significant amplification above background [3].

Performance Data: In colorectal cancer samples, this LBDA approach achieved a detection limit of 0.08% variant allele frequency with only 20 ng of synthetic DNA input [3]. When applied to 59 CRC tumor samples, the method identified KRAS mutations in 37.29% of cases, demonstrating 88% sensitivity and 100% specificity compared to NGS [3].

Table 2: Experimental Performance of qPCR-Based Methods in Cancer Detection

| Cancer Type | qPCR Method | Genes Detected | Sensitivity | Specificity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | Multiplex qPCR (11-gene panel) | EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, ALK, ROS1, RET, MET, NTRK1-3, HER2 | 100% (vs. tissue) | 100% (vs. tissue) | [5] |

| Colorectal Cancer | LBDA qPCR | KRAS hotspots | 88% (vs. NGS) | 100% (vs. NGS) | [3] |

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Standard qPCR (cobas EGFR test) | EGFR exons 18-21 | 76.14% concordance with NGS | 76.14% concordance with NGS | [2] |

Analytical Validation Framework for qPCR Assays

Rigorous validation is essential for implementing reliable qPCR assays in clinical cancer research. The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines provide a foundational framework for ensuring assay quality and reproducibility [8] [9].

Key Validation Parameters

- Inclusivity: Determines how well the qPCR detects all intended target variants. Validation should include up to 50 well-defined strains or variants reflecting the genetic diversity of the target [8].

- Exclusivity/Cross-reactivity: Assesses the assay's ability to exclude genetically similar non-targets. Both in silico analysis and experimental testing with near-neighbor species are required [8].

- Linear Dynamic Range: Established using a seven 10-fold dilution series of DNA standards analyzed in triplicate. The acceptable linearity (R²) value is typically ≥0.980, with primer efficiency between 90-110% [8].

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest concentration at which the target can be reliably detected. Determined through serial dilution studies in relevant biological matrices [8] [9].

- Precision and Accuracy: Evaluated through replicate testing of samples across multiple runs, operators, and instruments [9].

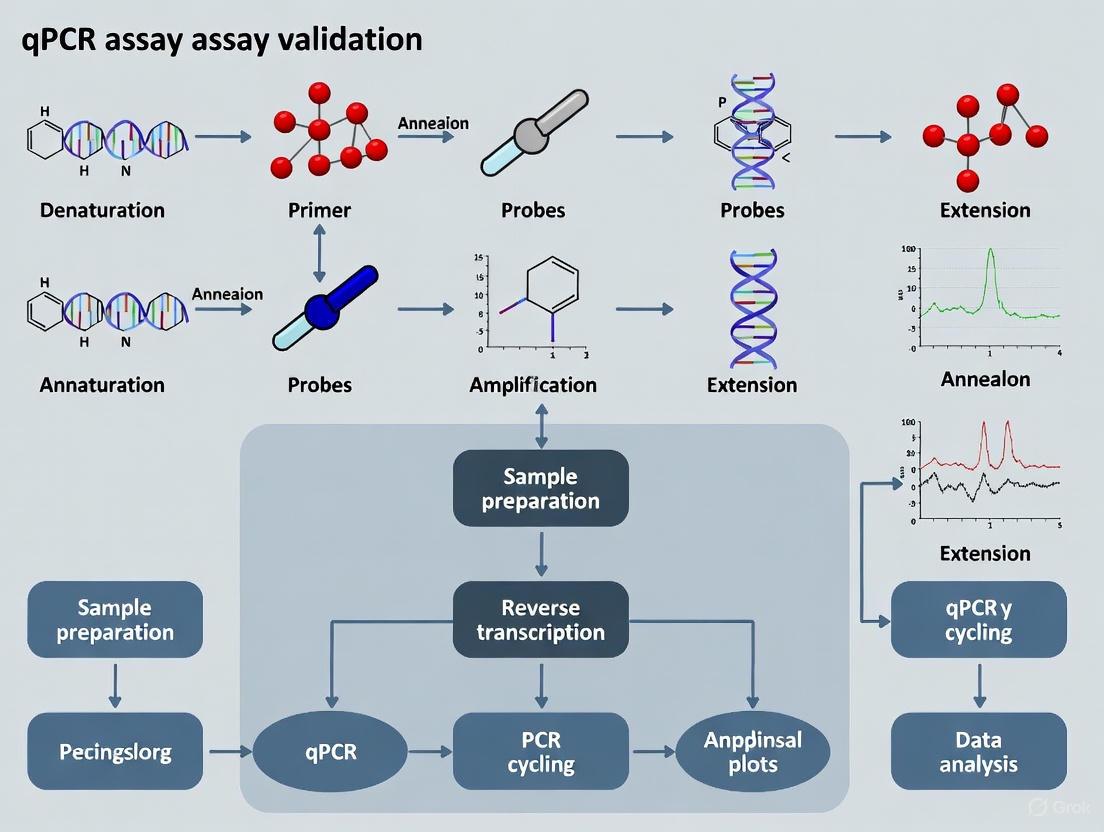

Figure 1: qPCR Assay Validation Workflow for Clinical Cancer Diagnostics

For laboratories implementing qPCR tests, whether as laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) or commercially available kits, verification of manufacturer's performance claims is essential [9]. This becomes particularly important for commercial assays, as performance may vary based on laboratory-specific factors including staff competency, equipment maintenance, and workflow systems [9].

qPCR Workflow Integration in Cancer Diagnostic Pathways

qPCR technology offers unique advantages in clinical workflows, particularly when integrated with traditional diagnostic methods to enhance overall efficiency and reliability.

Figure 2: qPCR Clinical Workflow for Cancer Mutation Detection

A 2025 study demonstrated the powerful synergy between traditional smear cytology (TSC) and qPCR testing for lung cancer diagnosis [5]. When used alone, TSC based on micro cell samples achieved a diagnostic yield of 78.9-93.5% across different sample types. However, when combined with qPCR genetic testing, the diagnostic yield increased to 81.6-98.1%, while maintaining a rapid 24-hour turnaround time [5]. This integrated approach exemplifies how qPCR complements established pathological methods to improve diagnostic accuracy without sacrificing speed.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of qPCR assays in cancer research requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for clinical samples. The following table details key components for robust qPCR-based mutation detection.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for qPCR-Based Cancer Mutation Detection

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Master Mixes | Oncology-specific qPCR master mixes [1] | Inhibitor-resistant polymerases, optimized buffers for clinical matrices (plasma, FFPE, cfDNA) | High-sensitivity detection in challenging samples |

| Mutation Detection Kits | Lung Cancer 11-Gene Mutations Detection Kit [5] | Pre-optimized multiplex assays for simultaneous detection of key cancer drivers | Comprehensive genotyping with minimal sample input |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | QIAamp DNA Micro Kit [5] | Efficient recovery from limited samples (fine needle aspirates, liquid biopsies) | Maximizing yield from low-input clinical specimens |

| Ambient-Stable Formulations | Lyophilized qPCR reagents [1] | Cold chain-independent transport and storage | Decentralized testing, resource-limited settings |

| Reference Standards | Biosynthetic DNA reference material [2] | Known variant allele frequencies for assay validation and quality control | Analytical validation, proficiency testing |

| Inhibition Resistance | Next-generation polymerases [1] | Tolerance to PCR inhibitors in clinical matrices (heparin, hemoglobin) | Reliable performance with direct clinical samples |

Modern qPCR reagent systems incorporate significant advancements including inhibitor-resistant enzymes, ambient-temperature stability, and enhanced multiplexing efficiency [1]. These innovations have substantially expanded the clinical utility of qPCR in oncology applications, enabling more reliable and efficient quantification of nucleic acids across diverse sample types and conditions.

qPCR maintains its cornerstone position in targeted cancer mutation detection through its unmatched combination of speed, cost-efficiency, and analytical robustness. The technology excels in clinical scenarios requiring rapid turnaround for a defined set of actionable mutations, particularly when sample material is limited or infrastructure constraints preclude more complex methodologies. While NGS offers superior discovery power for comprehensive genomic profiling, and digital PCR provides exceptional sensitivity for absolute quantification, qPCR remains the optimal solution for targeted mutation detection across a broad range of clinical and research settings [1] [6] [4].

For researchers and drug development professionals, qPCR represents a validated, accessible, and economically viable platform for precision oncology applications. Its continued evolution through advanced chemistries, improved multiplexing capabilities, and enhanced integration with complementary technologies ensures that qPCR will remain an indispensable tool in the cancer diagnostics arsenal for the foreseeable future.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains a foundational technology in clinical oncology, enabling critical advancements in early cancer detection and personalized therapy selection. Its value is anchored in a unique combination of analytical sensitivity, rapid turnaround time, and cost-effectiveness, making it uniquely suited for informing therapeutic decision-making at scale, particularly in time-sensitive or resource-constrained settings [1]. Within the framework of analytical validation, qPCR assays provide robust, reproducible, and clinically actionable data. This guide objectively compares qPCR's performance against alternative methodologies like digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) and next-generation sequencing (NGS), providing supporting experimental data and detailed protocols to inform researchers and assay developers in the field of clinical cancer diagnostics.

Performance Comparison of qPCR, ddPCR, and NGS

The diagnostic performance of nucleic acid detection technologies varies significantly based on the application, target, and required sensitivity. The following tables summarize key comparative data.

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Performance in Detecting Circulating Tumor HPV DNA (ctHPVDNA) [10]

| Detection Platform | Sensitivity (Pooled) | Specificity (Pooled) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Lower than ddPCR and NGS (P<0.001) | Similar across all platforms | Cost-effective, rapid, widely established |

| Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR) | Higher than qPCR, Lower than NGS (P=0.014) | Similar across all platforms | Absolute quantification, high sensitivity for low-frequency variants |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Greatest among the three platforms | Similar across all platforms | Multiplexing capability, discovery of novel variants |

Table 2: General Operational and Economic Comparison in Oncology Diagnostics [1]

| Parameter | qPCR | ddPCR | NGS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate Cost per Test | $50 - $200 | ~$150 - $300 | $300 - $3,000 |

| Typical Turnaround Time | Hours | Several hours | Days |

| Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) Sensitivity | <0.1% | <0.1% | ~1-5% (varies by coverage) |

| Multiplexing Capability | Strong (4-6 plex) | Limited | Excellent (High-plex) |

| Infrastructure & Complexity | Low; widely accessible | Moderate | High; requires specialized infrastructure |

| Best Suited For | High-throughput, targeted screening; routine diagnostics | Ultra-sensitive quantification of known variants; liquid biopsies | Comprehensive genomic profiling; discovery |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Multiplex qPCR for Targeted Mutation Detection in NSCLC

This protocol is designed for the simultaneous detection of actionable mutations in genes like EGFR, KRAS, and BRAF from patient samples such as FFPE tissue or liquid biopsies [1].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract DNA from patient samples (e.g., FFPE tissue, plasma cfDNA) using a magnetic bead-based method. Quantify DNA using a spectrophotometer and dilute to a working concentration of 1-5 ng/μL.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 30 μL qPCR reaction mixture:

- 17 μL of qPCR master mix (containing inhibitor-resistant polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer)

- 1 μL each of forward and reverse primers for multiple targets

- 1 μL of target-specific probes (e.g., TaqMan probes with different fluorophores)

- 10 μL of template DNA [11]

- Thermal Cycling: Run the reaction on a real-time PCR instrument with the following program:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 40 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute [11]

- Data Analysis: Analyze amplification curves to determine Cq values. Use a standard curve for absolute quantification or ΔΔCq method for relative expression. Report clinically actionable mutations based on pre-validated Cq thresholds.

Protocol 2: Analytical Validation of a qPCR Assay for Residual Host Cell DNA

This method details the development and validation of a qPCR assay for quantifying residual Vero cell DNA in biological products, demonstrating the principles of analytical validation [11].

- Assay Design:

- Target Selection: Select highly repetitive, unique genomic sequences (e.g., a 172 bp tandem repeat or Alu repetitive elements) to maximize sensitivity.

- Primer/Probe Design: Design primers and probes targeting specific amplicons (e.g., 99 bp or 154 bp within the 172 bp sequence).

- Standard Curve and Linearity: Prepare a 10-fold serial dilution of the Vero genomic DNA standard, covering a range from 0.03 pg/μL to 30 pg/μL. Run the dilution series in triplicate to establish a standard curve. The assay must demonstrate a linear correlation with an R² value of >0.99 [11].

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ):

- Specificity: Test the assay against genomic DNA from other common cell lines (e.g., CHO, HEK293) and bacterial strains to ensure no cross-reactivity [11].

- Precision and Accuracy: Assess intra- and inter-assay precision by calculating the relative standard deviation (RSD), which should be <20% across samples. Evaluate accuracy via spike-recovery experiments, with an ideal recovery rate of 85%-115% [11].

Visualizing the qPCR Workflow in Clinical Oncology

The following diagram outlines the standard workflow for applying qPCR in clinical cancer research, from sample collection to clinical decision-making.

Diagram Title: qPCR Clinical Workflow and Applications

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of qPCR in clinical oncology relies on specialized reagents formulated to address the challenges of complex biological samples.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Oncology qPCR Assay Development

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Characteristics for Oncology Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Resistant Master Mix | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, and optimized buffers for amplification. | Engineered to tolerate PCR inhibitors in clinical matrices (e.g., heparinized plasma, FFPE-derived nucleic acids) [1]. |

| Ambient-Stable Lyophilized Beads | Pre-formulated, room-temperature stable reaction pellets. | Reduces cold-chain costs, ideal for decentralized testing and OEM applications [1]. |

| Target-Specific Primers & Probes | Enables specific detection and quantification of mutant alleles. | Designed for high specificity and efficiency; crucial for multiplexed detection of actionable mutations [11]. |

| Quantified Genomic DNA Standards | Serves as a positive control and for generating standard curves. | Essential for assay validation, determining limits of detection (LOD), and ensuring quantitative accuracy [11]. |

| Internal Positive Control (IPC) | Distinguishes true negative results from PCR inhibition. | Added to each reaction to confirm that a negative result is due to the absence of the target, not assay failure. |

Advantages in Speed, Cost-Efficiency, and Scalability for Routine Diagnostics

Within the evolving landscape of clinical cancer diagnostics, the analytical validation of assays is paramount for ensuring reliable patient results. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains a foundational technology in this sphere, particularly when balanced against the capabilities of emerging methods like digital PCR (dPCR) and next-generation sequencing (NGS). This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies, focusing on their performance in speed, cost, and scalability—critical factors for routine diagnostic workflows in research and drug development. By examining direct experimental data and validated protocols, this analysis aims to equip scientists with the evidence needed to make informed platform selections for clinical cancer research.

Technology Comparison: qPCR vs. dPCR vs. NGS

The selection of a nucleic acid detection platform involves trade-offs between analytical sensitivity, throughput, cost, and turnaround time. The table below summarizes the core performance characteristics of qPCR, dPCR, and NGS based on current literature and market data.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nucleic Acid Detection Technologies in Clinical Diagnostics

| Feature | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Digital PCR (dPCR) | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Principle | Fluorescence-based real-time quantification relative to a standard curve [12] | Absolute nucleic acid quantification by end-point analysis of partitioned samples [12] | Massively parallel sequencing of clonally amplified DNA fragments [13] |

| Theoretical Sensitivity (Variant Allele Frequency) | ~1% (can be lower with optimized assays) [1] | <0.1% - 0.5% [12] [14] | ~1-2% (can be lower with deep sequencing) [13] |

| Absolute Quantification | No (requires standard curve) | Yes (via Poisson statistics) [12] | No (requires bioinformatic normalization) |

| Turnaround Time (Hands-on to result) | Several hours [13] [1] | Several hours [12] | Days to weeks [13] |

| Cost per Sample | $50 - $200 [1] | Higher than qPCR [12] | $300 - $3,000 [1] |

| Multiplexing Capability | High (with multiple probes/dyes) [1] [15] | Moderate (limited by fluorescence channels) | Very High (entire genomes/exomes) [13] |

| Best Suited For | High-throughput, rapid detection of known variants, routine screening [13] [1] | Detection of rare mutations, absolute quantification without standards, liquid biopsy monitoring [12] | Discovery of novel variants, comprehensive genomic profiling, complex mutation panels [13] |

| Infrastructure & Skill Demand | Widely accessible, standard molecular biology skills | Requires specialized instrumentation, moderate complexity | Demanding bioinformatics infrastructure and expertise [13] |

Experimental Data and Performance Benchmarks

Diagnostic Sensitivity in Liquid Biopsy Applications

Liquid biopsy, which involves analyzing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), presents a significant challenge for detection due to the low abundance of tumor DNA in a high background of wild-type DNA. A meta-analysis of circulating tumor HPV DNA (ctHPVDNA) detection across multiple cancer types provides a direct comparison of platform sensitivities.

Table 2: Comparative Sensitivity of ctHPVDNA Detection Platforms (Meta-Analysis Data) [16]

| Detection Platform | Relative Diagnostic Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Baseline (Lowest) | Similar across platforms |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Higher than qPCR (P < 0.001) | Similar across platforms |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Highest (P = 0.014 vs. ddPCR) | Similar across platforms |

This data demonstrates a clear tiered sensitivity, with NGS being the most sensitive, followed by dPCR, and then qPCR. However, this superior sensitivity comes at the cost of longer turnaround times and higher price points, making qPCR a robust choice for monitoring known, relatively abundant mutations.

Assay Performance in ESR1 Mutation Detection

A 2025 literature review of ESR1 mutation testing in advanced breast cancer provides a practical view of technology selection. The review identified 28 commercial assays for detecting ESR1 mutations in liquid biopsies, including four qPCR, four dPCR, and twelve NGS-based assays. The analysis concluded that while dPCR and NGS can offer high sensitivity, qPCR remains a clinically viable option with performance varying by the specific assay design and input DNA. The selection depends on the required analytical performance, desired turnaround times, and the available lab infrastructure and expertise [17]. This underscores that for many routine diagnostic contexts, qPCR provides a favorable balance of speed, cost, and sufficient accuracy.

Experimental Protocols for Analytical Validation

To ensure the reliability of qPCR assays in clinical research, the following key experimental protocols are employed for analytical validation.

Limit of Detection (LoD) and Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) Determination

- Objective: To determine the lowest concentration of a target mutant sequence that can be reliably detected by the qPCR assay.

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Serially dilute synthetic mutant DNA targets into a background of wild-type genomic DNA. The dilutions should cover a range of Variant Allele Frequencies (e.g., from 5% down to 0.1%).

- qPCR Run: Amplify each dilution in a minimum of 20 replicates to establish a statistical confidence level (e.g., ≥95% detection rate).

- Data Analysis: The LoD is defined as the lowest VAF at which ≥95% of the replicates return a positive result. This validates the assay's sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants, which is critical for liquid biopsy applications [1] [18].

Multiplexing Efficiency and Cross-Talk Validation

- Objective: To confirm that a single multiplex qPCR reaction can simultaneously and specifically detect multiple targets without interference.

- Methodology:

- Assay Design: Design primer-probe sets for multiple targets (e.g., mutations in EGFR, KRAS, and BRAF), each labeled with a spectrally distinct fluorescent dye.

- Specificity Testing: Run each primer-probe set individually in singleplex reactions and then combined in a multiplex reaction. Compare the amplification efficiency (measured by the Cq value) and the fluorescence signal in each channel between singleplex and multiplex setups.

- Analysis: A significant loss of sensitivity or an increase in background fluorescence (cross-talk) in the multiplex format indicates suboptimal assay conditions. Successful validation shows that the multiplex reaction performs with the same efficiency as the singleplex reactions, maximizing data output from minimal sample material [1] [15].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting and validating a diagnostic technology based on clinical needs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The performance of a qPCR assay is heavily dependent on the quality and suitability of its core reagents. The following table details essential components for developing robust oncology diagnostics.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for qPCR Assay Development in Oncology Diagnostics

| Reagent / Material | Function / Key Characteristic | Application in Clinical Assays |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Master Mix | Optimized buffer and enzyme formulation for high sensitivity and specificity. | Core reagent for amplification; essential for detecting low-frequency variants in ctDNA [13] [1]. |

| Inhibitor-Resistant Polymerase | Engineered polymerase tolerant to PCR inhibitors found in clinical samples (e.g., from plasma, FFPE). | Ensures robust assay performance across diverse and challenging sample matrices [1]. |

| dUTP/UNG Contamination Control | Master mix containing dUTP and Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) to prevent amplicon carryover. | Critical for high-throughput and reusable equipment settings to avoid false positives [13]. |

| Ambient-Stable (Lyo-Ready) Formulations | Reagents compatible with lyophilization for ambient-temperature storage and transport. | Enables decentralized testing, point-of-care use, and stable kit development for global distribution [13] [1]. |

| Multiplex Probe Systems | Sets of primers and probes labeled with different, non-overlapping fluorescent dyes. | Allows simultaneous detection of multiple mutations in a single reaction, conserving sample and increasing throughput [1] [15]. |

| Reference Templates | Synthetic DNA or well-characterized genomic DNA with known target mutations and wild-type sequences. | Serves as essential positive and negative controls for assay development, validation, and routine quality control. |

In the context of analytical validation for clinical cancer diagnostics, no single technology holds an absolute advantage; the choice is dictated by the specific clinical question and operational constraints. qPCR maintains its position as the optimal tool for high-speed, cost-effective, and scalable detection of known actionable mutations in routine diagnostics, especially where rapid therapeutic decisions are needed. dPCR provides superior sensitivity for absolute quantification of rare variants, while NGS offers unparalleled breadth for discovery and comprehensive profiling. A thorough understanding of the comparative data and validation protocols presented here empowers researchers and drug developers to strategically deploy qPCR, ensuring robust, reliable, and accessible diagnostic solutions.

The success of clinical cancer diagnostics and the development of targeted therapies hinge on the accurate molecular profiling of tumor material. In modern oncology, this analysis relies heavily on a variety of sample types, each with its own unique set of advantages and limitations. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue has long been the gold standard, providing a stable, histologically-rich resource. More recently, the analysis of circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from liquid biopsies has emerged as a powerful, minimally invasive tool for genomic profiling and monitoring therapy response [19] [20].

A significant challenge common to both sample types is the limited quantity and quality of nucleic acids available for testing. FFPE samples are notoriously compromised by chemical cross-linking and nucleic acid fragmentation, while cfDNA samples often contain very low concentrations of tumor-derived DNA (ctDNA) within a high background of wild-type DNA [20] [21]. This guide objectively compares the performance of qPCR assays across these challenging sample matrices, providing a framework for their analytical validation in clinical cancer research.

Sample Type Characteristics and Technical Hurdles

The pre-analytical variables and inherent properties of FFPE and liquid biopsy samples directly influence the choice of analytical platform and the design of the validation strategy. The table below summarizes the core challenges associated with each sample type.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Challenges of Key Oncology Sample Types

| Sample Type | Core Characteristics | Primary Technical Hurdles |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE Tissue | - Chemically cross-linked and fragmented nucleic acids [21]- Long-term stability at room temperature- Allows for correlative histopathology | - Nucleic acid degradation impacts yield and quality [21]- PCR inhibition from residual formalin [1]- Challenging DNA/RNA co-extraction [21] |

| Liquid Biopsy (cfDNA) | - Minimally invasive, enables serial monitoring [20]- Represents tumor heterogeneity [22]- Short turnaround time [19] | - Extremely low input of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) [19]- High background of wild-type DNA [23]- Critical pre-analytical conditions (e.g., blood draw to plasma processing time) [22] |

| Low-Input Samples (e.g., Fine Needle Aspirates, Low-Volume Plasma) | - Minimal material, often precludes repeat testing- Essential for hard-to-biopsy cancers | - Risk of false negatives due to sampling error- Maximizing data output from minimal input is critical [1]- Assay sensitivity and robustness are paramount |

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected challenges and considerations when working with these sample types, from collection to analysis.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Validation

Robust analytical validation is fundamental to generating reliable data from challenging samples. Key performance parameters must be rigorously established for each sample type and assay.

Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

Sensitivity requirements are particularly stringent for liquid biopsy applications due to the low variant allele frequency (VAF) of ctDNA. For example, the Aspyre Lung assay, a multiplexed qPCR-based test, demonstrated a 95% limit of detection (LoD95) of 0.19% VAF for single nucleotide variants and indels in cfDNA, alongside 100% specificity for all targets [19]. This level of sensitivity is crucial for detecting minimal residual disease (MRD) and early resistance mutations.

Digital PCR (dPCR) platforms, which include droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) and BEAMing PCR, offer alternative approaches for ultra-sensitive detection. One study comparing BEAMing PCR to standard qPCR for EGFR mutation detection in NSCLC patients reported high concordance rates (98.8% for exon 19 and 95.5% for exon 21), confirming the reliability of sensitive methods for profiling ctDNA [23].

Table 2: Comparative Analytical Performance of PCR Assays Across Sample Types

| Assay / Technology | Reported Sensitivity (LoD) | Reported Specificity | Sample Type Validated On | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspyre Lung qPCR (Multiplexed) | 0.19% VAF (SNV/Indels); 1 amplifiable copy (Fusions) [19] | 100% [19] | cfDNA, cfRNA, FFPE DNA/RNA [19] | Model trained on >13,500 contrived samples; enables single-workflow tissue and plasma testing [19]. |

| BEAMing dPCR (EGFR) | High sensitivity for mutant allele detection [23] | High specificity [23] | ctDNA from plasma [23] | 98.8% concordance with qPCR for exon 19 deletions; useful for mutation detection in background of normal DNA [23]. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) (EGFR) | High sensitivity [22] | Specificity validated with external controls [22] | cfDNA from plasma [22] | Pre-analytical conditions (shipping time, extraction) critically impact performance; in-house primers/probes can offer superior sensitivity [22]. |

| RT-qPCR (Reference Genes) | Varies with assay design | Varies with assay design | FFPE RNA, Cell line RNA [24] | ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A genes are unstable in dormant cancer cells and are inappropriate references; validation of stable genes like B2M/YWHAZ is essential [24]. |

Nucleic Acid Yield and Quality

The quality of input material is a primary determinant of assay success. A comparative study of nucleic acid extraction kits from FFPE tissue highlights significant variability in performance. Omega Bio-tek's Mag-Bind FFPE DNA/RNA 96 Kit, for instance, demonstrated significantly higher DNA yield from FFPE lung and breast tumor samples compared to kits from two other manufacturers (Company T and Q). Furthermore, the average ΔCq value—a metric for FFPE DNA quality where a lower value indicates higher quality—was 3.10 for Omega Bio-tek versus 4.06 and 5.32 for competitors, indicating superior preservation of nucleic acid functionality [21].

For RNA from FFPE samples, the DV200 value (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides) is a key quality indicator. The same study found that the Omega Bio-tek kit yielded RNA with a DV200 of 70.97% for lung and 76.86% for colorectal FFPE tumors, outperforming other kits and exceeding the Illumina-recommended threshold of 20% for successful sequencing [21].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Standardized and optimized experimental protocols are critical for ensuring reproducibility and data reliability.

Pre-Analytical cfDNA Workflow for ddPCR

The CIRCAN study provides a detailed workflow for the detection of EGFR mutations in cfDNA using ddPCR [22]:

- Blood Collection and Processing: Blood is drawn into EDTA tubes. Plasma is separated via a two-step centrifugation protocol: first at 820 × g for 10 minutes, followed by a second centrifugation of the supernatant at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove any remaining cellular debris.

- cfDNA Extraction: cfDNA is extracted from 1 mL of plasma using a commercially available DNA Micro Kit, following the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted DNA is eluted in a minimal volume.

- Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): The ddPCR reaction is set up using validated primer/probe sets for wild-type and mutant EGFR alleles (e.g., delEX19, L858R, T790M). The reaction mixture is partitioned into thousands of nanodroplets. Amplification is carried out on a thermal cycler, and droplets are read on a droplet reader to quantify the absolute number of mutant and wild-type DNA molecules.

Reference Gene Validation for RT-qPCR in Challenging Models

In novel experimental models, such as dormant cancer cells, classic reference genes can become unstable. A 2025 study established a protocol for validating reference genes in mTOR-suppressed cancer cells [24]:

- Model Generation: Treat cancer cell lines (e.g., A549, T98G) with a dual mTOR inhibitor (e.g., AZD8055) to induce a dormant phenotype.

- RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis: Extract total RNA from treated and control cells, and synthesize cDNA.

- Candidate Gene Screening: Perform RT-qPCR on a panel of 12 commonly used housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB, B2M, YWHAZ).

- Stability Analysis: Use algorithms (e.g., geNorm, NormFinder) to rank the genes based on their expression stability. The study found that ACTB and ribosomal protein genes (RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A) were highly unstable under these conditions, while B2M and YWHAZ were among the most stable for A549 cells [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right reagents is fundamental to overcoming sample-specific challenges. The following table details key solutions mentioned in the literature.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Challenging Sample Types

| Product / Solution | Primary Function | Key Features & Benefits | Supported Sample Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mag-Bind FFPE DNA/RNA 96 Kit (Omega Bio-tek) [21] | Co-extraction of DNA and RNA from FFPE samples. | - Uses non-toxic mineral oil for deparaffinization- Yields high-quality, functional nucleic acids with low ΔCq- Provides DNA-free RNA and RNA-free DNA in separate eluates | FFPE Tissues |

| Oncology-Focused qPCR Reagents (Meridian Bioscience) [1] | Master mixes for robust qPCR amplification. | - Engineered for inhibitor tolerance in clinical matrices (plasma, FFPE)- High sensitivity (<0.1% VAF detection)- Ambient-stable formulations for decentralized testing | cfDNA, FFPE-derived DNA, Low-input samples |

| Aspyre Lung Reagents (Biofidelity) [19] [1] | Targeted biomarker panel for NSCLC. | - Covers 114 genomic variants across 11 genes- Simultaneous DNA and RNA analysis from same workflow- Machine learning-powered data interpretation for high sensitivity | cfDNA, cfRNA, FFPE DNA/RNA |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) Assays [22] | Absolute quantification of rare mutant alleles. | - High sensitivity and specificity for low-VAF variants- Digital counting of molecules enables precise quantification- Suitable for tumor-agnostic and tumor-informed approaches | ctDNA from Plasma |

The landscape of clinical oncology samples is inherently complex, dominated by FFPE tissues with compromised nucleic acids and liquid biopsies with ultra-low target concentrations. Success in this field requires a deep understanding of the specific challenges posed by each sample type. As the data shows, qPCR and dPCR technologies, when paired with optimized reagents and rigorous validation, are capable of meeting these demands, delivering the sensitivity, specificity, and robustness required for modern cancer diagnostics and drug development. By adhering to stringent validation guidelines and selecting tools fit for purpose, researchers can reliably generate meaningful data from even the most challenging samples, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery and precision medicine.

Building a Robust qPCR Assay: From Design to Data Interpretation

The precision of quantitative PCR (qPCR) in clinical cancer diagnostics hinges on the meticulous design of its core components: primers, probes, and the amplicon. For research aimed at predicting responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy or detecting low-frequency cancer mutations, a robust assay design is not merely a preliminary step but the foundation of reliable, analytically valid results [1] [25] [26]. This guide objectively compares design strategies and presents supporting experimental data to inform the development of qPCR assays for cancer research.

Core Component Design and Comparison

The performance of a qPCR assay is directly governed by the biochemical properties of its primers and probes. Adherence to established design principles is crucial for achieving high specificity, sensitivity, and efficiency.

Primer Design Fundamentals

Primers are the critical determinants of assay specificity and efficiency. Optimal design requires balancing multiple biochemical parameters [27] [28].

- Length and Melting Temperature (Tm): Primers should be 18–22 base pairs long, with a Tm typically between 55–60°C. The forward and reverse primer Tm should be within 2°C of each other to ensure simultaneous annealing [27].

- GC Content and Sequence: Aim for a GC content of 35–65%, avoiding long stretches of a single nucleotide (homopolymers) or repeated G/C bases, especially at the 3' end, to prevent mis-priming [27].

- Specificity and Validation: Primer sequences must be checked for specificity using tools like NCBI BLAST to avoid amplification of non-target sequences, including pseudogenes. Furthermore, the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) must be determined empirically through a temperature gradient, as it is distinct from the in silico-calculated Tm and is vital for robustness [28].

Table 1: Key Design Parameters for qPCR Primers and Probes

| Parameter | Primers | TaqMan Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Length | 18–22 bp [27] | 20–30 bp [29] |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | ~55–60°C [27] | 65–70°C; 8–10°C higher than primers [29] [30] |

| GC Content | 35–65% [27] | Avoid 5' G; more C than G [30] |

| Critical Checks | Specificity (BLAST), secondary structures (dimers, hairpins) [27] [28] | Avoid repetitive sequences, especially 4 consecutive Gs [29] |

Probe Selection and TaqMan Chemistry

TaqMan probes offer superior specificity compared to intercalating dye methods by providing an additional layer of sequence-specific detection [29].

- Working Principle: A TaqMan probe is a dual-labeled oligonucleotide with a 5' fluorophore and a 3' quencher. During PCR, when the probe binds to its target, the 5' to 3' exonuclease activity of the DNA polymerase cleaves the probe, separating the fluorophore from the quencher and generating a fluorescent signal [31] [29].

- Multiplexing Capability: TaqMan chemistry supports high-order multiplexing. Using different fluorophore-labeled probes, assays can detect up to five or six targets in a single reaction, which is invaluable for profiling multiple cancer biomarkers simultaneously from limited sample material [1] [31].

Amplicon Selection Criteria

The amplicon—the DNA region amplified by the primers—must be carefully selected to ensure efficient and specific detection.

- Length: For standard qPCR, ideal amplicon lengths are between 70–140 base pairs. This is short enough to ensure high amplification efficiency and is crucial when working with fragmented DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples, a common source in cancer research [27] [26].

- Location: For mRNA quantification in RT-qPCR, primers should be designed to span an exon-exon junction. This ensures amplification of the spliced cDNA and not contaminating genomic DNA [27]. Assays must also be designed to avoid common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the binding sites [27].

Experimental Validation Protocols

A well-designed assay requires rigorous experimental validation to confirm its performance characteristics are fit for purpose in a clinical research setting.

Establishing Assay Efficiency and Dynamic Range

A core validation step is determining the amplification efficiency and dynamic range of the assay through a standard curve.

- Methodology: A serial dilution (e.g., 10-fold) of the target template (e.g., plasmid DNA or synthetic gBlock) with a known concentration is amplified. The Cq value is plotted against the logarithm of the starting quantity for each dilution [26].

- Data Interpretation: A slope between -3.1 and -3.6, a correlation coefficient (R²) greater than 0.99, and a calculated PCR efficiency between 90–110% are indicators of a highly efficient and precise assay [26]. Efficiencies outside this range suggest suboptimal primer/probe binding or issues with reaction components.

Assessing Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

Sensitivity and specificity define an assay's ability to detect low amounts of the target and to distinguish it from related non-targets.

- Limit of Detection (LoD): The lowest concentration at which the target is detected in ≥95% of replicates. For example, a multiplex qPCR for duck viruses reported LoDs as low as 6.03 x 10¹ copies/μL for individual targets, demonstrating high sensitivity [32].

- Specificity Testing: The assay must be tested against a panel of non-target organisms or genetic variants to ensure no cross-reactivity. In the development of a 10-plex qPCR for bladder cancer, researchers confirmed primer specificity using Standard Nucleotide BLAST and wet-lab testing against non-target sequences [26].

Ensuring Reproducibility and Robustness

Reproducibility is assessed by testing the assay's performance across different operators, instruments, and days.

- Protocol: Run replicates of samples at high, medium, and low concentrations across multiple runs (inter-assay) and within the same run (intra-assay) [26].

- Acceptance Criteria: The results are typically expressed as the Coefficient of Variation (CV) of the Cq values. Both intra- and inter-assay CVs should generally be below 10%, confirming the assay is robust and generates consistent results [32] [26].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key stages of qPCR assay design and validation.

Comparative Performance in Clinical Applications

qPCR holds a distinct position in the molecular diagnostics landscape, particularly when compared to broader profiling technologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS).

qPCR vs. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

The choice between qPCR and NGS is driven by the clinical or research question, with each technology offering complementary strengths.

Table 2: Performance Comparison between qPCR and NGS in Cancer Diagnostics

| Characteristic | qPCR | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Best Application | Targeted mutation detection, rapid therapy selection [1] | Comprehensive genomic profiling, discovery [1] |

| Turnaround Time | Hours [1] | Days [1] |

| Cost per Sample | $50 – $200 [1] | $300 – $3,000 [1] |

| Multiplexing Scale | Moderate (e.g., 4-10 plex) [1] [32] | High (100s-1000s of targets) [1] |

| Analytical Sensitivity | High (can detect <0.1% VAF) [1] | Moderate (typically 1-5% VAF) [1] |

| Infrastructure Needs | Low, more accessible [1] | High, complex infrastructure [1] |

qPCR excels in time-sensitive, resource-conscious, and targeted applications. For example, in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), multiplexed qPCR panels can simultaneously assess alterations in genes like EGFR, KRAS, and ALK, delivering results faster and using less input material than NGS [1]. This makes qPCR indispensable for large-scale screening and routine diagnostics where a defined set of actionable biomarkers is known.

The Critical Role of MIQE 2.0 Guidelines

The publication of the MIQE 2.0 guidelines is a critical response to widespread issues of poor transparency and reproducibility in qPCR-based research [25]. These guidelines provide a checklist of essential information that must be reported to ensure experimental rigor. Compliance is non-negotiable in clinical cancer research, as failures in proper sample handling, assay validation, and data normalization can lead to exaggerated sensitivity claims and overinterpreted results with real-world consequences for patient diagnosis and treatment [25] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful assay development relies on a suite of high-quality reagents and tools. The following table details key components for developing a robust qPCR assay for cancer diagnostics.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for qPCR Assay Development

| Item | Function / Key Feature | Example Application / Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer. | Oncology-specific formulations are engineered for inhibitor resistance in clinical samples (e.g., plasma, FFPE) and high sensitivity for low-frequency variants [1]. |

| TaqMan Probes | Dual-labeled hydrolysis probes for specific target detection. | MGB probes enable shorter, more specific probes and higher-order multiplexing (up to 5-plex) for profiling multiple cancer biomarkers [31]. |

| Custom qPCR Primers | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides for target amplification. | HPLC-purified, desalted primers minimize synthesis impurities that increase background noise and decrease assay sensitivity and reproducibility [31] [28]. |

| RNA/DNA Extraction Kits | Purify nucleic acids from complex biological samples. | Kits designed for FFPE tissue or cell-free DNA are critical for obtaining high-quality input material from clinically relevant sample types [26]. |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | Convert RNA to cDNA for RT-qPCR analysis. | Preamplification master mixes can be used to enable analysis of low-input and degraded RNA samples commonly encountered in cancer research [26]. |

| qPCR Assay Design Tool | In silico software for selecting optimal primers/probes. | Automated tools analyze sequence constraints to recommend primer/probe sets with appropriate Tm, GC%, and specificity [30]. |

The foundational elements of qPCR—primers, probes, and amplicons—must be designed with precision and validated with rigor. As shown, qPCR maintains a competitive edge over NGS for targeted, rapid, and cost-effective applications in clinical oncology, such as therapy selection and large-scale screening. By adhering to MIQE 2.0 guidelines and employing a disciplined approach to assay design and validation, researchers can ensure their qPCR data are robust, reproducible, and reliable, thereby solidifying the role of this powerful technology in the advancement of cancer diagnostics and personalized medicine.

In the field of clinical cancer diagnostics research, quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains a foundational tool for detecting oncogenes, monitoring minimal residual disease, and validating cancer biomarkers. Its high sensitivity, rapid turnaround, and cost-effectiveness make it uniquely suited for informing therapeutic decisions. A critical choice in developing a robust qPCR assay is the detection chemistry: the intercalating dye SYBR Green or the sequence-specific Hydrolysis Probes (often referred to as TaqMan probes). This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two chemistries to inform their application in validating cancer targets.

Mechanism of Detection: A Visual Guide

The core difference between the two chemistries lies in their mechanism for detecting amplified PCR products. The diagrams below illustrate the specific signaling pathways for each.

SYBR Green Detection Mechanism

Hydrolysis Probe Detection Mechanism

Direct Comparison: Performance and Practicality

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each chemistry, supported by experimental data, to guide your selection.

| Feature | SYBR Green | Hydrolysis Probes (TaqMan) |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Lower; binds any dsDNA (e.g., primer-dimers, non-specific products). Requires post-run melt curve analysis for verification. [33] | Higher; requires binding of a sequence-specific probe, minimizing false positives from non-specific amplification. [33] [34] |

| Sensitivity (LOD) | Can be highly sensitive with optimization. One study achieved a detection limit of 3.16 TCID50/mL in infected tissues. [35] | Excellent sensitivity, consistently capable of detecting low-frequency variants below <0.1% variant allele frequency (VAF). Ideal for liquid biopsy and MRD. [1] |

| Cost | Relatively cost-benefit. No need for expensive labeled probes. [33] | More expensive due to the cost of fluorogenic probe synthesis and validation. [33] [36] |

| Experimental Workflow | Easier and faster setup. Requires only primer design. [33] [37] | More complex design. Requires optimization of primers and a probe with a higher Tm. [36] [37] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Not possible, as the dye binds to all double-stranded DNA products non-specifically. [38] | Excellent. Multiple targets can be detected in a single reaction by using probes labeled with different reporter dyes. [36] [1] |

| Best Suited For |

Quantitative Experimental Data

A direct comparative study on breast cancer tissues measuring adenosine receptor subtypes provides robust experimental data on the performance of both chemistries when optimized.

Table: Performance Comparison in Breast Cancer Gene Expression Analysis [33]

| Gene Target | SYBR Green (Normalized Expression) | Hydrolysis Probe (Normalized Expression) | PCR Efficiency | Correlation (P-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 Adenosine Receptor | 1.44 | 1.38 | >97% for both methods | Positive and Significant (P < 0.05) |

| A2A Adenosine Receptor | 2.38 | 2.43 | >97% for both methods | Positive and Significant (P < 0.05) |

| A2B Adenosine Receptor | 3.79 | 3.84 | >97% for both methods | Positive and Significant (P < 0.05) |

| A3 Adenosine Receptor | 3.55 | 3.58 | >97% for both methods | Positive and Significant (P < 0.05) |

Conclusion from Data: With the use of high-performance primers and proper optimization, SYBR Green can generate precise data comparable to the hydrolysis probe method. The correlation between the normalized expression data from both methods was positive and statistically significant for all genes tested. [33]

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Hydrolysis Probe qPCR for miRNA (96-Well Plate)

This protocol, adaptable for cancer targets like microRNAs from liquid biopsies, highlights the specificity of probe-based chemistry. [34]

cDNA Synthesis (Reverse Transcription):

- Use 10 ng of total RNA extracted from serum or plasma in a 5 µL reaction volume.

- Prepare a master mix containing RT Buffer (1X), dNTPs (100 mM), RNase Inhibitor (20 U/µL), and reverse transcriptase (50 U/µL).

- Add 1 µL of a sequence-specific RT primer.

- Incubate on a thermal cycler: 16°C for 30 min, 42°C for 30 min, 85°C for 5 min (enzyme inactivation), and hold at 4°C.

Probe-based qPCR:

- Prepare a qPCR reagent mix containing a proprietary master mix, nuclease-free water, and a 20X probe-based assay mix (containing primers and probe).

- Combine 4.2 µL of this mix with 0.8 µL of cDNA in an optical 96-well plate.

- Seal the plate and centrifuge briefly.

- Run on a real-time PCR instrument with the following cycling conditions:

- Hold: 95°C for 20 sec (polymerase activation)

- 40-50 Cycles: 95°C for 1 sec (denaturation), 60°C for 30 sec (annealing/extension).

Protocol 2: SYBR Green qPCR for Gene Expression

This is a general protocol for SYBR Green-based detection, which requires a post-run melting curve analysis to verify specificity. [40]

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a 50 µL reaction containing:

- 25 µL of 2X SYBR Green Master Mix (hot-start Taq polymerase, buffer, dNTPs, SYBR Green dye).

- 1 µL each of 10 µM forward and reverse primers (200 nM final concentration).

- Template DNA (e.g., up to 100 ng genomic DNA, or cDNA generated from up to 1 µg total RNA).

- Nuclease-free water to volume.

- Include a no-template control (NTC) to check for contamination.

- Prepare a 50 µL reaction containing:

Thermal Cycling and Melt Curve:

- UDG Incubation (Optional): 50°C for 2 minutes to prevent amplicon carryover.

- Polymerase Activation: 95°C for 10 minutes.

- Amplification (40 Cycles): 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 60 sec.

- Melting Curve Analysis: Program the instrument to gradually increase temperature from 60°C to 95°C (e.g., by 0.3°C/sec) while continuously monitoring fluorescence. A single sharp peak indicates a specific product; multiple peaks suggest primer-dimers or non-specific amplification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application in Cancer Research |

|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Resistant Master Mix | Specially formulated polymerases and buffers to tolerate PCR inhibitors common in clinical samples like heparinized plasma, FFPE-derived nucleic acids, and cell-free DNA (cfDNA), ensuring reliable results. [1] |

| Ambient-Stable Master Mix | Lyophilized or stable liquid formulations that do not require a cold chain. Ideal for decentralized testing, resource-limited settings, or OEM diagnostic kit development. [1] |

| Pre-designed Assay Panels | Hydrolysis probe-based assays for multiplexed detection of clinically actionable mutations (e.g., in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, ALK). Provide standardized, validated protocols for rapid deployment in labs. [1] |

| ROX Reference Dye | A passive dye included in the reaction to normalize for non-PCR-related fluctuations in fluorescence between wells, critical for accurate quantification in high-throughput settings. [40] |

| UDG (Uracil-DNA Glycosylase) | An enzyme included in many master mixes to prevent re-amplification of carryover PCR products between runs, a key quality control measure in clinical diagnostics. [40] |

The choice between SYBR Green and hydrolysis probes is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is optimal for your specific research context within clinical cancer diagnostics.

- Choose SYBR Green for initial, cost-effective screening, when working with non-standardized targets, or when melt curve analysis provides sufficient specificity for the assay.

- Choose Hydrolysis Probes when your objective requires the highest level of specificity in a complex biological matrix (e.g., plasma), when multiplexing several cancer targets, or when validating biomarkers with the utmost confidence for potential clinical application.

Ultimately, with careful optimization and validation, both chemistries are powerful tools for the analytical validation of qPCR assays in the fight against cancer.

Multiplexing Strategies for Simultaneous Multi-Gene Mutation Detection

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains a cornerstone technology in clinical cancer diagnostics, prized for its rapid turnaround time, cost-effectiveness, and high analytical sensitivity [1]. In the context of precision oncology, the ability to simultaneously interrogate multiple clinically actionable mutations from a single, often limited, patient sample is paramount. Multiplex qPCR strategies address this need by enabling the parallel detection of several DNA targets within one reaction, conserving precious sample material, reducing reagent costs, and streamlining laboratory workflow [41] [42]. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary multiplex qPCR approaches, evaluated against the rigorous demands of analytical validation for clinical research. The performance of these methods is critical for applications such as therapy selection, patient stratification, and tracking treatment resistance, where the accuracy and comprehensiveness of mutation profiling can directly impact patient management.

Comparative Analysis of Multiplex qPCR Strategies

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of three advanced multiplexing strategies, based on recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Multiplex qPCR Strategies for Mutation Detection

| Multiplexing Strategy | Theoretical Multiplexing Capacity | Demonstrated Sensitivity (Mutant Allele Fraction) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color Cycle Multiplex Amplification (CCMA) [43] | Up to 136 targets (with 4 colors) | Not explicitly quantified for low AF, but provides quantitative Ct data | Exceptional multiplexing capacity on standard instruments; quantitative output; suitable for syndromic panels. | Complexity in assay design (requires blocker oligonucleotides); newer approach with less extensive validation. |

| Multiplex Allele-Specific qPCR (with ARMS/Blockers) [41] [44] | Limited by available fluorescent channels (typically 4-6). | 0.05% - 0.5% [41]; ~5% for PIK3CA H1047R [44] | Well-established and optimized; very high sensitivity; robust on FFPE-derived DNA. | Lower multiplexing capacity per reaction tube; requires careful optimization to prevent primer interference. |

| Allele-Specific LNA qPCR [45] | Limited by available fluorescent channels. | Comparable to NGS; linear detection from 0% to 95% mutant [45] | Excellent specificity and sensitivity for single-nucleotide variants; LNA probes enhance allele discrimination. | Similar channel-limited multiplexing; cost of LNA-modified probes may be higher. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Multiplex Allele-Specific qPCR for PIK3CA Mutation Detection

This protocol, adapted from a study screening 515 colorectal cancer samples, is designed for high-sensitivity detection of hotspot mutations in genes like PIK3CA [41].

- Sample Preparation: DNA is extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections using a dedicated kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit). DNA quantity and quality are assessed, with fragmentation and chemical modifications expected [41].

- Assay Design:

- Primers: Allele-specific primers are designed with the 3' end complementary to the mutant sequence to preferentially amplify mutant alleles [44].

- Blockers: A wild-type blocking oligonucleotide (e.g., phosphate-modified to prevent extension) is included. It binds to the wild-type sequence, suppressing its amplification and enhancing the specificity for the mutant allele [44].

- Multiplexing: Multiple primer sets, each tagged with a unique fluorophore, are combined in a single master mix.

- Reaction Setup:

- Thermocycling: Conditions are optimized for the specific master mix. An example protocol is: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 50-60 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min, with fluorescence acquisition at the annealing/extension step [41].

- Data Analysis: The Cycle threshold (Ct) for each target is determined. A sample is considered positive for a mutation if the Ct value for the mutant-specific channel is significantly lower than that of a wild-type control, and/or falls within a validated positive range [44].

Protocol: Color Cycle Multiplex Amplification (CCMA)

CCMA is a novel strategy that uses temporal fluorescence patterns, rather than color alone, to dramatically increase multiplexing capacity [43].

- Core Principle: Each DNA target is programmed to induce a sequential, pre-determined pattern of fluorescence increases across different color channels over the course of the qPCR run. The identity of the target is determined by this unique fluorescence "permutation" [43].

- Implementation via Blocker Displacement Amplification (BDA):

- Blocker Design: For a given target, multiple amplicons are designed, each corresponding to a different fluorophore. Rationally designed oligonucleotide blockers are used to competitively bind to the template, programmably delaying the amplification of specific amplicons [43].

- Ct Delay: By adjusting the binding strength (thermodynamics) or concentration of these blockers, the Ct value for each color channel can be precisely delayed by several cycles relative to the first, unblocked amplicon. This creates the characteristic step-wise fluorescence pattern [43].

- Workflow: The workflow is similar to a standard multiplex qPCR from a sample preparation and run standpoint. However, the data analysis involves interpreting the order and Ct values of fluorescence emergence across all channels to identify the present pathogen or mutant target.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing and validating a multiplex qPCR assay, from sample to clinical research application.

The PI3K-AKT-mTOR Signaling Pathway in Cancer

Mutations in genes like PIK3CA are frequently screened using multiplex qPCR. The PIK3CA gene encodes the catalytic subunit of PI3K, a key node in the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway, which is crucial for cell survival, proliferation, and metabolism [41] [44]. This pathway is one of the most frequently altered in human cancers, making it a major focus for molecular diagnostics and targeted therapy.

The diagram below outlines the core components of this pathway, highlighting where common mutations occur and how targeted inhibitors intervene.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of a multiplex qPCR assay for clinical research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplex qPCR Assay Development

| Reagent / Material | Function and Importance in Assay Development |

|---|---|

| Specialized DNA Polymerase Master Mixes | Next-generation master mixes are engineered for inhibitor resistance (e.g., for FFPE, plasma), thermal stability for faster cycling, and enhanced multiplexing efficiency [1]. |

| Allele-Specific Primers | Primers designed with the variant base at the 3' end to preferentially initiate amplification from the mutant allele, forming the basis of allele discrimination [41] [44]. |

| Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Probes | Modified nucleic acid analogs incorporated into TaqMan probes to increase binding affinity (Tm) and greatly improve specificity for discriminating single-nucleotide variants [45]. |

| Wild-Type Blocker Oligonucleotides | Non-extendible oligonucleotides that bind to and suppress the amplification of the wild-type sequence, thereby dramatically improving the sensitivity for detecting low-abundance mutants [44]. |

| Fluorophore-Labeled Probes | TaqMan probes labeled with distinct fluorophores (e.g., FAM, HEX, Cy5, ROX) for each target, enabling simultaneous detection in a multiplex reaction [41] [43]. |

| Synthetic DNA Templates (gBlocks) | Defined, synthetic DNA fragments used as positive controls for assay validation, calibration curve generation, and determining limits of detection and quantification [43] [45]. |

| FFPE-Specific Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Optimized kits for recovering fragmented and cross-linked DNA from FFPE tissues, which is the most common source of material in clinical cancer diagnostics [41]. |

The choice of a multiplexing strategy for multi-gene mutation detection is a strategic decision that balances multiplexing capacity, sensitivity, specificity, and technical complexity. Traditional multiplex allele-specific qPCR remains a robust, highly sensitive, and well-validated choice for profiling a defined set of core hotspots. In contrast, emerging technologies like Color Cycle Multiplex Amplification offer a paradigm shift for applications requiring very high multiplexing without specialized instrumentation. For clinical research aimed at informing therapeutic decisions, the analytical validation of any chosen method—demonstrating precision, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity against a reference standard—is non-negotiable. As the field advances, these qPCR-based multiplexing strategies will continue to be indispensable tools for enabling precision oncology in diverse laboratory settings.

The quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and its counterpart for RNA analysis, reverse transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR), are foundational technologies in modern clinical cancer diagnostics research. Their power to precisely quantify nucleic acids enables critical applications from gene expression profiling of cancer biomarkers to validating oncogenic signatures. The reliability of any qPCR result, however, is entirely dependent on the integrity and execution of its core workflow: nucleic acid isolation, reverse transcription, and amplification. This guide provides an objective comparison of methodologies and critical reagents within this workflow, framing them within the essential context of analytical validation for robust and reproducible clinical cancer research.

Nucleic Acid Isolation: A Foundation of Data Quality

The initial step of nucleic acid isolation is arguably the most critical, as it determines the quality and quantity of the starting template. Variations in sample type and isolation methods can significantly impact downstream results, a point rigorously considered during assay development.

Sample Type Considerations

Research often relies on diverse sample types, each with unique challenges. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues are a invaluable resource in oncology, but their fixation process can fragment RNA. Studies have demonstrated that successful qPCR with FFPE material requires a minimum RNA quality threshold (e.g., DV200 >15%) [46]. In contrast, fresh-frozen (FF) tissues and cell lines typically yield higher-quality RNA. Furthermore, the use of liquid biopsies, such as peripheral blood, is gaining traction for non-invasive diagnostics. One study successfully validated a five-gene pancreatic cancer signature from blood samples, confirming that with careful processing (e.g., RNA Integrity Number, RIN >7), reliable gene expression data can be obtained from these minimally invasive samples [47].

Comparison of Isolation Method Performance

The choice of isolation kit and protocol directly influences yield, purity, and the presence of enzymatic inhibitors. The following table summarizes key performance metrics for isolation strategies applicable to different sample types in cancer research.

Table 1: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Isolation Methods for Cancer Research Samples

| Sample Type | Recommended Method | Key Performance Metrics | Considerations for Clinical Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cultures | Direct lysis (e.g., Trizol) + column-based purification [48] | High yield and purity (A260/A280 ~1.8-2.0) from ~350μL Trizol [48] [49] | High throughput; suitable for screening; requires DNase treatment to eliminate gDNA [50]. |

| Fresh-Frozen Tissues | Column-based or magnetic bead purification | Yields high-quality RNA (RIN >8); optimal for sensitive gene expression assays | Considered the "gold standard" for analytical validation of new assays. |

| FFPE Tissues | Specialized FFPE RNA extraction kits | Requires DV200 >15%; stable performance across storage conditions [46] | High concordance with FF results can be achieved; fragmentation is a key variable to control [46]. |

| Peripheral Blood | Leucopak or whole blood RNA extraction (e.g., TRIzol LS) | Requires RIN >7 for reliable results in downstream assays [47] | Critical for liquid biopsy applications; sample processing time (<2h) is vital to prevent RNA degradation [47]. |

Reverse Transcription: Converting RNA to cDNA

The reverse transcription (RT) step converts RNA into more stable complementary DNA (cDNA), introducing another major source of technical variability. The choice between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR protocols is dictated by the research application.

- One-Step RT-qPCR: Combines the reverse transcription and PCR amplification in a single tube. This setup is optimal for high-throughput applications and minimizes pipetting steps, reducing the risk of contamination. It is often preferred in diagnostic settings for pathogen detection [51].

- Two-Step RT-qPCR: Physically separates the RT reaction from the PCR amplification. This approach is favored in gene expression studies in cancer research because it allows the generated cDNA to be used for multiple qPCR assays, enabling the validation of several gene targets from a single, consistent cDNA pool [48]. This provides greater flexibility and is more suited for assay development and validation.

A critical experimental protocol for the two-step method, as used in cancer cell research, is detailed below.

Table 2: Detailed Two-Step cDNA Synthesis Protocol [48]

| Step | Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Input RNA | Amount | 1000 ng total RNA |

| Reaction Setup | Total Volume | 40 μL |

| Master Mix | SuperScript VILO MasterMix (8 μL) | |

| Water | DNAse/RNAse-free, to volume | |

| Thermocycling | Step 1: Primer Incubation | 25°C for 10 minutes |

| Step 2: Reverse Transcription | 42°C for 60 minutes | |

| Step 3: Enzyme Inactivation | 85°C for 5 minutes | |

| Step 4: Hold | 4°C indefinitely |

qPCR Amplification: Detection, Chemistry, and Assay Design

The amplification phase is where quantitative detection occurs. Key choices here involve detection chemistry and assay design, which directly influence the specificity, sensitivity, and cost of the experiment.

Detection Chemistries: Probe-Based vs. Intercalating Dyes

- TaqMan Probe-Based Assays: These assays (e.g., 5' nuclease assays) use a sequence-specific, dual-labeled probe with a 5' fluorophore and a 3' quencher. The polymerase degrades the probe during amplification, releasing the fluorophore and generating a fluorescent signal [50]. This technology offers superior specificity by ensuring that the detected signal originates only from the intended target, making it the preferred choice for clinical assay validation where distinguishing between homologous genes or splice variants is crucial [50].

- SYBR Green-Based Assays: This chemistry utilizes a dye that fluoresces brightly when intercalated into double-stranded DNA. While more cost-effective and easier to design, SYBR Green will bind to any dsDNA, including primer-dimers and non-specific products, which can lead to false-positive signals [49]. The requirement for post-amplification melt curve analysis to verify amplicon specificity is mandatory [49].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of qPCR Detection Chemistries

| Characteristic | TaqMan (Probe-Based) | SYBR Green (Dye-Based) |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | High (sequence-specific probe) | Moderate (binds any dsDNA) |

| Background Signal | Low | Higher |

| Multiplexing Potential | High (multiple probe colors) | Low (single dye) |

| Assay Development Cost | Higher (requires probe) | Lower |

| Experimental Verification | Melt curve not required | Melt curve analysis essential [49] |

| Ideal Use Case | Clinically validated assays; multiplexing; splice variant detection [50] | Gene expression screening; assay optimization |

Primer and Probe Design Criteria

A well-designed assay is critical for accurate quantification. Adherence to established design parameters minimizes secondary structures and non-specific amplification.

- Primer Design: Primers should be 18-30 bases long with a Tm of ~60-62°C and GC content between 35-65% (ideally ~50%). Runs of more than four consecutive Gs should be avoided. To prevent amplification of genomic DNA, primers should be designed to span exon-exon junctions [50].

- Probe Design: For TaqMan assays, the probe should have a Tm 5-10°C higher than the primers and be limited to ~30 bases for optimal quenching. A guanine (G) base at the 5' end should be avoided as it can quench common dyes like FAM [50].

- Amplicon: The ideal amplicon size for probe-based assays is between 70-200 bp to ensure efficient amplification [50].

Analytical Validation in Cancer Research: A Case Study

Robust analytical validation ensures that a qPCR assay is reliable, reproducible, and fit for its intended purpose in clinical research. A prime example is the development of a multiplex qPCR assay to predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) in muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) [46].

- Robustness Across Sample Types: The assay was validated to perform with high concordance between FFPE and fresh-frozen tissues, a critical feature for leveraging historical archives [46].

- Impact of Pre-Analytical Variables: The assay demonstrated stable performance across different RNA input levels (5–100 ng), and was minimally affected by tissue necrosis or different technicians, proving its reproducibility in a real-world diagnostic context [46].