AI-Powered Virtual Screening: Computational Protocols Revolutionizing Anticancer Drug Discovery

This comprehensive review explores the transformative role of computational virtual screening protocols in accelerating anticancer drug discovery.

AI-Powered Virtual Screening: Computational Protocols Revolutionizing Anticancer Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the transformative role of computational virtual screening protocols in accelerating anticancer drug discovery. It examines foundational concepts, from target identification to drug repurposing, and details state-of-the-art methodologies including molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and AI-accelerated platforms. The article provides practical insights for troubleshooting common challenges and presents rigorous validation frameworks through case studies across various cancer targets. By synthesizing recent advances and real-world applications, this work serves as an essential resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage computational approaches for developing more effective and targeted cancer therapies.

Virtual Screening Foundations: From Basic Concepts to Anticancer Applications

Virtual screening (VS) is a computational technique that automatically searches through libraries of molecules to identify structures most likely to bind effectively to a therapeutic target, such as a protein receptor or enzyme implicated in cancer progression [1]. In the pharmaceutical industry, VS has demonstrated efficacy as a strategy for effectively identifying bioactive molecules, presenting the potential to drastically speed up the drug discovery phase, which is often hindered by huge costs and high failure rates [1]. In oncology, this approach is particularly valuable for identifying novel anti-tumor agents and targeted therapies [2].

The two primary computational strategies in virtual screening are ligand-based screening and structure-based screening [1].

Ligand-Based Screening: This approach is used when the 3D structure of the target protein is unknown but there is information about known active ligands. It involves creating a pharmacophore model—a set of structural features essential for biological activity—from a collection of active ligands, or performing 2D chemical similarity analyses to find new molecules that resemble known actives [1]. This method is computationally efficient, often requiring only a single CPU to screen thousands of compounds rapidly [1].

Structure-Based Screening (Molecular Docking): This method is employed when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is available. It involves computationally "docking" candidate small molecules into the binding site of the target protein and scoring their complementary to predict binding affinity [3] [1] [4]. This approach is more computationally intensive and typically relies on a parallel computing infrastructure to manage large datasets and run multiple comparisons simultaneously [1].

AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening Platforms

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has transformed virtual screening, enabling the efficient exploration of ultra-large chemical libraries containing billions of compounds [3] [5]. AI-driven platforms can slash development timelines and boost success rates by learning complex patterns from large datasets of chemical compounds and biological targets [5].

State-of-the-Art Platforms and Performance

Recent advances have led to the development of highly accurate, open-source platforms. One such platform, RosettaVS, incorporates an improved physics-based force field (RosettaGenFF-VS) and uses active learning to triage the most promising compounds for expensive docking calculations [3]. This platform has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance on standard benchmarks.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of RosettaGenFF-VS on CASF-2016 Dataset

| Benchmark Metric | Performance of RosettaGenFF-VS | Comparison to Second-Best Method |

|---|---|---|

| Docking Power (Pose Prediction) | Top-performing method for distinguishing native binding poses from decoys [3] | Superior performance across a broad range of ligand RMSDs [3] |

| Screening Power (Top 1% Enrichment Factor) | EF~1%~ = 16.72 [3] | Outperformed second-best method (EF~1%~ = 11.9) by a significant margin [3] |

| Success Rate (Identifying Best Binder) | Excelled at placing the best binder within the top 1%, 5%, and 10% of ranked molecules [3] | Surpassed all other methods in the benchmark [3] |

In practical applications, this AI-accelerated platform successfully screened multi-billion compound libraries against two unrelated oncology-relevant targets: the ubiquitin ligase KLHDC2 and the human voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.7. The screening process was completed in less than seven days, identifying hit compounds with single-digit micromolar binding affinities [3].

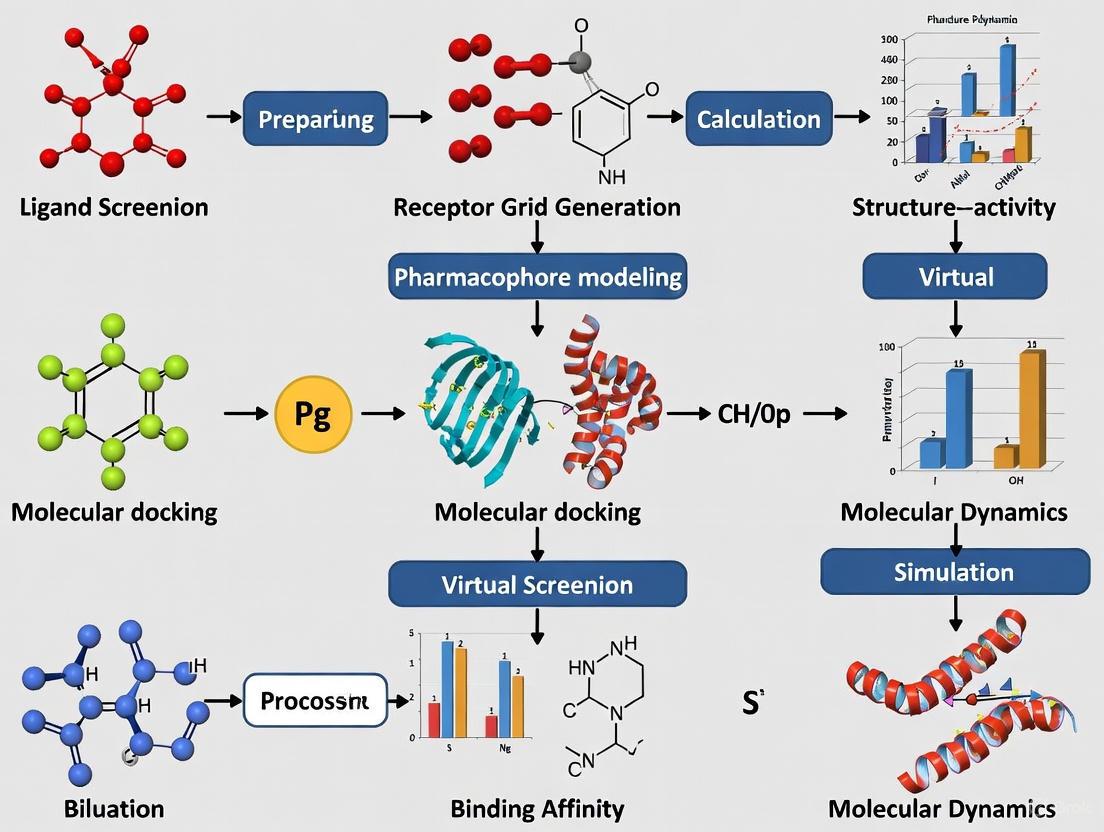

Workflow of an AI-Accelerated Screening Platform

AI-powered platforms integrate multiple components into a cohesive and iterative workflow. The following diagram illustrates the key stages of this process, from initial library preparation to final experimental validation.

Key Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing structure-based and AI-enhanced virtual screening campaigns in an oncology context.

Protocol for Structure-Based Virtual Screening with RosettaVS

This protocol is adapted from a successful screening campaign against the oncology target KLHDC2, which yielded a 14% hit rate with micromolar affinities [3].

Objective: To identify novel, high-affinity small-molecule binders to a defined binding site on an oncology target protein from an ultra-large chemical library.

Required Reagents and Resources:

- Target Structure: A high-resolution 3D structure of the protein target (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM) in PDB format [3] [4].

- Compound Library: A file (e.g., in SDF or SMILES format) of small molecules to screen. Publicly available libraries include ZINC and PubChem [4].

- Computational Infrastructure: A high-performance computing (HPC) cluster. The referenced study used a cluster with 3000 CPUs and one GPU per target [3].

- Software: The OpenVS platform incorporating RosettaVS [3].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Target Preparation:

- Obtain the protein structure and prepare it using molecular modeling software (e.g., Maestro, MOE).

- Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define protonation states of key residues at physiological pH.

- Define the binding site coordinates based on known ligand interactions or structural data.

Ligand Library Preparation:

- Download and curate the compound library. Apply filters for drug-like properties (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) and remove pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) [4].

- Generate biologically relevant, low-energy 3D conformers for each molecule in the library.

Hierarchical Docking with RosettaVS:

- Stage 1 - VSX (Virtual Screening Express) Mode: Perform rapid, initial docking of the entire library. In this mode, the receptor is treated as rigid to maximize speed [3].

- Stage 2 - VSH (Virtual Screening High-precision) Mode: Take the top-ranked hits from the VSX stage (e.g., top 1-5%) and re-dock them using the high-precision mode. This mode allows for full receptor side-chain flexibility and limited backbone movement, which is critical for accurately modeling induced fit upon ligand binding [3].

Scoring and Hit Selection:

- Score the final docking poses from the VSH stage using the RosettaGenFF-VS scoring function, which combines enthalpy (∆H) calculations with a new model estimating entropy changes (∆S) upon binding [3].

- Rank the compounds based on their predicted binding affinity.

- Visually inspect the top 100-500 ranked compounds to assess binding pose rationality and key interactions.

Experimental Validation:

- Procure the top-ranked virtual hit compounds from commercial suppliers or synthesize them.

- Validate binding using biochemical assays (e.g., fluorescence polarization, surface plasmon resonance) to determine half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC~50~) or dissociation constant (K~d~) [3].

- Confirm functional activity in cell-based assays relevant to the oncology target (e.g., cell proliferation, apoptosis) [2].

Protocol for AI-Guided Hit Identification

This protocol leverages machine learning to enhance the efficiency of virtual screening [3] [5].

Objective: To employ a target-specific neural network, trained concurrently with docking calculations, to prioritize compounds for docking and improve hit rates.

Required Reagents and Resources:

- All resources from Protocol 3.1.

- An active learning framework integrated into the virtual screening platform (e.g., OpenVS) [3].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initial Sampling and Model Training:

- Start by docking a small, random subset (e.g., 0.1%) of the ultra-large library.

- Use the docking scores and molecular descriptors from this subset as training data to initialize a target-specific machine learning model (e.g., a deep neural network).

Iterative Active Learning Cycle:

- Predict: Use the trained ML model to predict the docking scores for the entire undocked portion of the library.

- Select: Prioritize and select a new batch of compounds for docking that the model predicts will have high affinity.

- Update: Dock the newly selected batch of compounds and add their results (true docking scores) to the training set.

- Retrain: Update the ML model with the expanded training data.

- Repeat this cycle until a predefined stopping criterion is met (e.g., number of compounds docked or convergence of hit discovery).

Final Hit Selection and Validation:

- After the active learning cycle is complete, the top-ranked compounds from the final model and their docking poses are analyzed.

- Proceed with experimental validation as described in Step 5 of Protocol 3.1.

Successful implementation of virtual screening requires a collection of specialized computational and experimental resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Virtual Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application in Virtual Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Public Compound Databases | ZINC [4], PubChem [4] | Provide libraries of commercially available, synthesizable small molecules for screening. |

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL [4], BindingDB [4] | Contain experimental bioactivity data for model training and validation. |

| Protein Structure Repository | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [4] | Source of 3D structural data for target preparation in structure-based screening. |

| Docking & VS Software | RosettaVS (OpenVS) [3], Glide [4], AutoDock Vina [3] | Core programs for predicting protein-ligand complex structures and binding affinities. |

| AI/ML Platforms | Aurigene.AI [6], BenevolentAI [5], Owkin [7] | Offer predictive and generative AI models for target identification, compound scoring, and lead optimization. |

| Computing Infrastructure | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Clusters [3] [1], NVIDIA GPUs [3] [6] | Provide the necessary parallel processing power for large-scale docking and AI model training. |

The discovery and development of novel anticancer agents represent a complex, risky, and costly endeavor, traditionally requiring over 15 years and exceeding $1.8 billion USD per approved drug [8]. Within this landscape, computational methodologies have become crucial components of drug discovery programs, significantly accelerating the identification and optimization of potential therapeutic compounds [8]. Computer-Aided Drug Discovery and Design (CADDD) harnesses various sources of information and computational techniques to facilitate the development of new drugs that modulate therapeutically relevant protein targets in cancer [8]. These approaches have evolved from serendipitous discovery to rational design, enabling researchers to make in silico improvements before resource-intensive laboratory experimentation [8].

Computational drug design approaches are broadly classified into two families: ligand-based and structure-based methods [8]. Ligand-based methods utilize existing knowledge of active compounds against a target to predict new chemical entities with similar behavior, while structure-based methods rely on three-dimensional structural information of the target to determine whether new compounds are likely to bind and interact effectively [8]. The integration of both approaches has become common in virtual screening, enhancing strengths while mitigating the limitations of each method individually [8]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for key computational methodologies within the context of virtual screening for anticancer drug discovery.

Key Terminology and Computational Concepts

Core Methodologies

Molecular Docking predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to its target binding site, enabling the prediction of binding affinity and molecular interactions [9] [10]. This technique is fundamental for structure-based virtual screening, allowing researchers to prioritize compounds with the highest predicted binding energies for further investigation.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling correlates the structural properties of compounds with their biological activity through statistical methods [11]. These models enable the prediction of biological activity for novel compounds based on their structural descriptors, guiding the optimization of lead compounds in anticancer development.

ADMET profiling predicts the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity properties of candidate molecules [12] [10]. These computational assessments are critical early in the discovery process to eliminate compounds with unfavorable pharmacokinetic or safety profiles, reducing late-stage attrition.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation analyzes the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing insights into the stability and dynamics of protein-ligand complexes under biologically relevant conditions [9] [13]. These simulations validate docking results and assess the temporal stability of binding interactions.

Pharmacophore Modeling identifies the essential structural features responsible for a compound's biological activity [12]. This approach schematically illustrates the critical components of molecular recognition, enabling the identification of novel compounds that share these key features regardless of their overall chemical structure.

Integrated Workflows in Anticancer Discovery

Modern computational drug discovery employs integrated workflows that combine multiple methodologies. For example, a typical structure-based virtual screening workflow might include: structure-based pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening of compound libraries, molecular docking of top hits, ADMET profiling, and final validation through molecular dynamics simulations [9] [10] [14]. Such integrated approaches have successfully identified potential inhibitors for various cancer targets, including PD-L1, VEGFR-2, c-Met, MCL1, and XIAP [9] [10] [13].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Computational Methods in Anticancer Discovery

| Method | Reported Enrichment | Library Size Screened | Success Rate | Key Applications in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Early enrichment factor (EF1%) = 10.0 [14] | 52,765 - 407,270 compounds [9] [13] | AUC: 0.98 [14] | XIAP, MCL1, VEGFR-2/c-Met inhibitors [10] [13] [14] |

| Molecular Docking | Binding affinity improvements from -6.8 kcal/mol to -11.2 kcal/mol [14] | 1.28 million compounds [10] | 18 hit compounds from 1.28 million [10] | PD-L1, VEGFR-2/c-Met dual inhibitors [9] [10] |

| QSAR Modeling | IC50 prediction below median value [13] | 407,270 compounds [13] | Sub-nanomolar potency achievement [13] | MCL1 inhibitor optimization [13] |

| MD Simulations | Stable conformation maintenance at 100 ns [9] [10] | 2-4 final candidates [10] [14] | Binding free energy validation [10] | PD-L1, VEGFR-2/c-Met, XIAP complex stability [9] [10] [14] |

| AI-Enhanced Screening | >50-fold hit enrichment vs traditional methods [15] | 26,000+ virtual analogs [15] | 4,500-fold potency improvement [15] | MAGL inhibitor optimization [15] |

Table 2: ADMET Profiling Parameters for Anticancer Candidate Selection

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Computational Tools | Impact on Candidate Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solubility | Level 3 (reference value) [10] | SwissADME [15] | Ensures adequate bioavailability |

| Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration | Level 3 (reference value) [10] | ADMET predictors [10] | Minimizes CNS-related side effects |

| Cytochrome P450 2D6 Inhibition | Non-inhibitor preferred [10] | PreADMET [14] | Reduces drug-drug interaction potential |

| Hepatotoxicity | Non-toxic preferred [10] | PreADMET [14] | Prevents liver damage |

| Human Intestinal Absorption | Level 0 (good absorption) [10] | SwissADME [15] | Ensures oral bioavailability |

| Plasma Protein Binding | Moderate to high [14] | PreADMET [14] | Influences drug distribution and half-life |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Application Context: Identification of natural PD-L1 inhibitors from marine natural products [9].

Principle: Structure-based pharmacophore modeling defines the essential steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition at a drug target's binding site [12] [9].

Procedure:

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D crystal structure of the target protein (e.g., PD-L1, PDB ID: 6R3K) from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. Remove water molecules, add hydrogen atoms, complete missing amino acid residues, and minimize energy using force fields (e.g., CHARMM) [9] [10].

- Pharmacophore Generation: Using molecular interaction data between the protein and a known co-crystallized ligand, generate pharmacophore features including:

- Model Validation: Validate the pharmacophore model using a decoy set containing known active compounds and inactive molecules. Calculate the Enrichment Factor (EF) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. A reliable model typically has AUC >0.7 and EF >2 [10] [14].

- Virtual Screening: Employ the validated pharmacophore model to screen large compound databases (e.g., ZINC, COCONUT, ChemDiv) to identify hits containing the essential features [9] [13] [14].

Protocol 2: Molecular Docking and Binding Affinity Assessment

Application Context: Identification of VEGFR-2 and c-Met dual inhibitors [10].

Principle: Molecular docking predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of small molecules within a target's binding site through scoring functions [9] [10].

Procedure:

- Ligand Preparation: Obtain 3D structures of compounds from databases. Prepare ligands by removing salts, adding hydrogen atoms, generating possible tautomers and protonation states, and minimizing energy [10].

- Binding Site Definition: Define the protein's binding site coordinates based on the known location from co-crystallized ligands or computational prediction methods [10] [14].

- Docking Execution: Perform docking simulations using software such as AutoDock or molecular operating environment. Apply appropriate search algorithms and scoring functions [15] [9].

- Pose Analysis and Scoring: Analyze the predicted binding poses and interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, π-π stacking). Rank compounds based on docking scores and evaluate binding free energies using methods like MM-GBSA or MM-PBSA [10] [13].

Protocol 3: ADMET Profiling

Application Context: Early-stage filtering of potential MCL1 inhibitors [13].

Principle: ADMET prediction evaluates the pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of compounds using computational models [12] [10].

Procedure:

- Compound Filtering: Apply Lipinski's Rule of Five and Veber's rules to filter compounds for drug-likeness [10].

- ADMET Prediction: Calculate key ADMET descriptors using tools such as PreADMET or SwissADME:

- Hit Selection: Prioritize compounds with favorable ADMET properties based on predefined cut-off values (e.g., solubility level >3, absorption level 0) [10].

Protocol 4: Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Application Context: Validation of XIAP inhibitor binding stability [14].

Principle: MD simulations assess the stability and dynamics of protein-ligand complexes under biologically relevant conditions over time [9] [14].

Procedure:

- System Setup: Place the protein-ligand complex in a solvation box with explicit water molecules. Add counterions to neutralize the system [9] [14].

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms [14].

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the system in NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) and NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensembles to achieve stable temperature and pressure [9].

- Production Run: Conduct production MD simulations for sufficient duration (typically 100-200 ns) using software like GROMACS or AMBER. Apply periodic boundary conditions and maintain constant temperature and pressure [9] [10] [14].

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration (Rg), and hydrogen bonding patterns to evaluate complex stability [9] [14].

Workflow Visualization of Computational Protocols

Diagram 1: Integrated Computational Workflow for Anticancer Drug Discovery. This workflow illustrates the sequential integration of computational methods from target identification to lead candidate selection, highlighting the screening and optimization phases.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Databases for Virtual Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Functionality | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/) [8] [10] | Provides 3D structural data of biological macromolecules | Source for target protein structures (e.g., XIAP PDB: 5OQW) [14] |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC Database, COCONUT, ChemDiv [10] [13] [14] | Curated collections of commercially available compounds for virtual screening | Source of natural products and synthetic compounds for screening [9] [13] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Discovery Studio, LigandScout [10] [14] | Generation and validation of structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models | Essential for Protocol 1: Structure-based pharmacophore modeling [14] |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock, SwissDock, Molecular Operating Environment [15] [9] | Prediction of ligand binding modes and binding affinities | Core component of Protocol 2: Molecular docking assessment [15] [9] |

| ADMET Prediction | PreADMET, SwissADME, pkCSM [10] [14] | Prediction of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties | Required for Protocol 3: ADMET profiling [10] [14] |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM [9] [10] [14] | Simulation of molecular systems over time to analyze stability and dynamics | Implementation of Protocol 4: MD simulation validation [9] [14] |

| Validation Data Sources | DUD-E (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) [10] [14] | Provides decoy compounds for validation of virtual screening methods | Used for pharmacophore model validation in Protocol 1 [14] |

The integration of computational protocols outlined in this document has transformed the landscape of anticancer drug discovery. Through structured workflows combining pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, ADMET profiling, and molecular dynamics simulations, researchers can efficiently identify and optimize promising therapeutic candidates with higher precision and reduced resource expenditure. These methodologies have demonstrated significant success across various cancer targets, including PD-L1, VEGFR-2, c-Met, MCL1, and XIAP, leading to novel inhibitors with validated binding stability and favorable drug-like properties [9] [10] [13]. As these computational approaches continue to evolve with advancements in artificial intelligence and machine learning, their predictive power and efficiency in anticancer drug discovery are expected to further increase, potentially reducing both timelines and attrition rates in the development of novel cancer therapeutics [15] [11].

The Role of Target Identification and Validation in Cancer Therapeutics

The discovery and development of effective cancer therapeutics are fundamentally reliant on the precise identification and validation of molecular targets. A drug target is a biological molecule, typically a protein, that plays a pivotal role in a disease pathway and whose modulation by a therapeutic agent is expected to yield a clinical benefit [16] [17]. In oncology, the landscape of target discovery has been revolutionized by rapid and affordable tumor profiling, which has led to an explosion of genomic data and facilitated the development of targeted therapies against specific oncogenic lesions [18]. However, the inherent complexity of cancer, characterized by different gene mutations and omics profiles across cancer types, demands a rigorous and multi-faceted approach to distinguish true therapeutic targets from mere biological noise [19] [17]. This document outlines standardized protocols and application notes for target identification and validation, framed within a modern computational paradigm for anticancer drug discovery.

Target Identification: Approaches and Protocols

Target identification is the initial critical step focused on discovering and prioritizing "druggable" biological molecules involved in cancer pathophysiology. An ideal target possesses several key properties: a pivotal role in the disease, confined expression to specific locations, the existence of a 3D model for druggability assessment, suitability for high-throughput screening, and a favorable predicted toxicity profile upon modulation [16]. The following protocols describe core identification strategies.

Protocol: Multi-Omics Data Analysis for Target Discovery

Principle: Integrative analysis of transcriptomics and proteomics data from cancer cell lines and patient tissues to identify genes and proteins significantly overexpressed or dysregulated in specific cancer types [19].

Materials:

- Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE): A publicly available database containing RNA-Seq transcriptomics data for over 1000 cancer cell lines [19].

- Proteomics Datasets: Tandem mass tag (TMT)-based quantitative proteomics data from cancer cell lines (e.g., from 375 cell lines as described in Nusinow et al.) [19].

- Bioinformatics Software: Tools for statistical analysis (e.g., R/Bioconductor), pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., GSEA, DAVID).

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Download RNA-Seq and proteomics data for 16 or more common cancer types (e.g., AML, breast cancer, NSCLC) from repositories such as the CCLE.

- Differential Expression Analysis: For each cancer type, identify significant transcripts and proteins by comparing their expression levels against all other cancer types. Apply false discovery rate (FDR) corrections to adjust for multiple hypothesis testing.

- Biotype Analysis: Classify significant transcripts into biotypes (e.g., protein-coding, lincRNA, pseudogene) to prioritize protein-coding targets.

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Input lists of significant transcripts and proteins into pathway analysis tools to identify biological pathways (e.g., olfactory transduction, GPCR signaling, mRNA processing) that are characteristic of each cancer type.

- Target Prioritization: Prioritize molecular targets that are:

- Statistically significant at both the transcript and protein levels.

- Enriched in cancer-specific pathways with known therapeutic relevance.

- Linked to patient survival or treatment response in clinical datasets.

Protocol: Functional Genomics Screening

Principle: Use RNA interference (RNAi) or CRISPR-Cas9 screens to systematically knock down or knock out genes in cancer cells to identify those essential for cell survival or proliferation (synthetic lethality) [18] [17].

Materials:

- shRNA or CRISPR Libraries: Genome-wide or pathway-focused libraries.

- Cancer Cell Lines: Representative of the cancer type of interest.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform: For quantifying guide RNA abundance.

Procedure:

- Library Transduction: Transduce a population of cancer cells with the shRNA or CRISPR library at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to ensure single integration events.

- Negative Selection: Culture the transduced cells for multiple population doublings. Cells carrying guides targeting essential genes will be depleted from the population.

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Extract genomic DNA from cells at the beginning (T0) and end (Tfinal) of the experiment. Amplify the integrated shRNA or guide RNA sequences and sequence them using NGS.

- Hit Identification: Calculate the depletion of individual guides between T0 and Tfinal using specialized bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., MAGeCK). Genes targeted by significantly depleted guides are considered essential for cancer cell fitness and are candidate therapeutic targets.

Computational Approaches in Identification

Computer-aided drug design (CADD) has emerged as a powerful technology to make drug discovery quicker, cheaper, and more efficient [20] [21]. Ligand-based virtual screening uses known active compounds to search large chemical databases for structurally similar molecules. Conversely, structure-based virtual screening uses the 3D structure of a target protein to computationally "dock" millions of small molecules and predict their binding affinity and pose [22] [21]. Machine learning models are now being employed to further accelerate this process by predicting docking scores without explicitly performing costly docking calculations, thereby enabling the virtual screening of ultra-large libraries [22].

Table 1: Summary of Target Identification Approaches

| Approach | Core Principle | Key Outputs | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Omics Analysis [19] | Integrative analysis of transcriptomics and proteomics data from cancer cell lines and tissues. | Lists of significant transcripts/proteins; enriched cancer-specific pathways. | Requires robust statistical correction; validation is essential. |

| Functional Genomics [18] | Systematic gene knockdown/knockout to identify genes essential for cancer cell survival. | Ranked list of candidate essential genes (synthetic lethal interactions). | Can have off-target effects; in vivo validation is often needed. |

| Computational Virtual Screening [22] [21] | Using computer simulations to identify hit molecules that bind to a defined target. | Predicted high-affinity ligands for a target protein. | Highly dependent on the quality of the target protein structure. |

Target Validation: Confirming Therapeutic Relevance

Once a candidate target is identified, it must be rigorously validated to confirm its functional role in the disease and that its modulation provides a therapeutic effect. Validation is a critical step to justify the substantial investment in subsequent drug discovery campaigns [17] [23].

Protocol: In vivo Target Validation Using Inducible RNAi

Principle: Combine inducible RNAi technology with genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) to assess the impact of target inhibition on tumor growth and to probe potential toxicities in a physiologically relevant in vivo context [18].

Materials:

- Inducible shRNA System: Vectors allowing doxycycline-dependent expression of shRNAs.

- Genetically Engineered Mouse Models (GEMMs): Models of specific cancers (e.g., lymphoma, melanoma).

- Imaging and Histology Equipment: For monitoring tumor growth and analyzing tissue samples.

Procedure:

- Model Generation: Generate GEMMs in which the expression of a specific shRNA targeting the candidate gene can be induced systemically or in a tissue-specific manner upon administration of doxycycline.

- Tumor Monitoring: Induce shRNA expression in tumor-bearing mice and monitor tumor progression and regression using caliper measurements or in vivo imaging.

- Toxicity Assessment: Closely monitor mice for signs of toxicity in normal tissues. Perform histopathological analysis on key organs post-study.

- Target Engagement Analysis: Validate that the shRNA-mediated knockdown leads to a significant reduction in the target protein levels within the tumors.

Protocol: Digital Pathology-Based Biomarker Analysis

Principle: Utilize multiplexed immunohistochemistry (IHC) or immunofluorescence (IF) coupled with whole-slide imaging and artificial intelligence (AI)-based analysis to quantitatively validate target expression and its spatial relationship within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [24] [25].

Materials:

- Tissue Microarrays (TMAs): Containing patient tumor samples and normal tissue controls.

- Multiplex Staining Kits: Such as Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA)-based kits for simultaneous detection of multiple proteins.

- Whole Slide Scanner: For high-resolution digitization of stained slides.

- Digital Pathology Software: Open-source (e.g., QuPath, ImageJ) or commercial (e.g., HALO).

Procedure:

- Multiplex Staining: Perform TSA-based multiplex IHC/IF on TMAs. A typical panel may include antibodies against the target protein (e.g., TROP2), tumor markers (PanCK), immune cell markers (CD8), and checkpoint inhibitors (PD-L1) [25].

- Slide Digitization: Scan the stained slides using a whole-slide scanner to create high-resolution digital images.

- Algorithmic Analysis: Use digital pathology software to train an AI algorithm to identify and quantify different cell types and the expression levels (membrane, cytoplasmic, nuclear) of the target protein.

- Spatial and Clinical Correlation: Correlate the quantitative target expression data (e.g., nuclear TROP2) with patient clinical outcomes such as progression-free survival (PFS) or response to immunotherapy to establish clinical relevance [25].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Target Validation and Qualification [23]

| Validation Component | Assessment Metrics (in ascending order of priority) |

|---|---|

| Target Validation (Human Data) | Tissue expression profile → Genetic association in humans (e.g., GWAS) → Clinical experience with target modulation (e.g., known drugs) |

| Target Qualification (Preclinical Data) | Phenotypic data from genetically engineered models → Evidence of target engagement and pathway modulation → Demonstrated efficacy in translational disease models |

Integration with Computational Drug Discovery

The identified and validated targets seamlessly feed into the computational pipeline for drug discovery. A highly validated target with a known or homology-modeled 3D structure becomes the foundation for structure-based drug design.

Workflow: From Validated Target to Lead Compound

The diagram below illustrates the integrated computational workflow, from a validated target to a optimized lead compound ready for experimental testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key reagents and platforms essential for conducting the experiments described in these protocols.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Target Identification & Validation

| Category / Reagent | Specific Example(s) | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Omics Platforms | RNA-Seq (CCLE), TMT-based Proteomics [19], Single-cell & Spatial Transcriptomics [25] | Generate comprehensive molecular profiles of cancers for target discovery. |

| Functional Genomics Tools | shRNA Libraries, CRISPR-Cas9 Systems [18] [17] | Perform genome-wide loss-of-function screens to identify essential genes. |

| Preclinical Models | Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [19], Genetically Engineered Mouse Models (GEMMs) [18] | Provide in vitro and in vivo systems for target validation and efficacy testing. |

| Digital Pathology | Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) Kits [24], Whole Slide Scanners, HALO/QuPath Software [24] [25] | Enable multiplexed protein detection and quantitative, spatially resolved biomarker analysis. |

| Computational Tools | Molecular Docking Software, XGBoost, Attention-based LSTM Networks [22] | Accelerate virtual screening and predict protein-ligand interactions. |

| Assay Development | Biochemical & Cellular Assays, High-Throughput Screening (HTS) [16] | Test and validate target engagement and functional activity of small molecules. |

| nor-4 | nor-4, CAS:163180-50-5, MF:C14H18N4O4, MW:306.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| UK-2A | UK-2A | UK-2A is a natural product-derived Qi site inhibitor fungicide for agricultural research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Target identification and validation form the critical, non-negotiable foundation of modern cancer drug discovery. The convergence of multi-omics, functional genomics, and advanced computational methods has created a powerful, integrated pipeline. This pipeline enables researchers to move from genomic data to a validated, "druggable" target with higher confidence and efficiency. By adhering to the rigorous protocols outlined herein—from multi-omics analysis and in vivo validation to AI-powered digital pathology and computational screening—researchers can de-risk the drug development process and prioritize the most promising targets for intervention. This structured approach is essential for translating the wealth of cancer genomic data into safe and effective therapeutics for patients.

Drug Repurposing Strategies for Oncology Applications

Drug repurposing represents a paradigm shift in oncology drug development, seeking to identify new therapeutic uses for existing drugs already approved for other conditions. This strategy significantly accelerates therapeutic development while reducing costs and risks associated with novel drug discovery [26] [27]. The established safety profiles, known pharmacokinetics, and existing clinical experience with these compounds enable researchers to bypass early-phase development stages, focusing resources directly on efficacy validation in oncological contexts [27] [28].

Computational approaches have revolutionized drug repurposing by enabling systematic, high-throughput screening of existing drug libraries against cancer-specific targets. The integration of bioinformatics, artificial intelligence (AI), and molecular modeling has transformed the field, allowing researchers to predict drug-target interactions with increasing accuracy and identify promising repurposing candidates from thousands of existing compounds [29] [20]. The global drug repurposing market, valued at US$29.4 billion in 2024 and projected to reach US$37.3 billion by 2030, reflects the growing importance of these approaches, with oncology representing the largest therapeutic segment [30].

Promising Repurposed Drug Candidates in Oncology

The Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO) database has identified 268 non-cancer drugs with published evidence of anticancer activity, demonstrating the substantial potential of this approach [27]. Table 1 summarizes the evidence levels and characteristics of these repurposing candidates.

Table 1: Evidence Profile for 268 Drugs in the ReDO Database

| Characteristic | Number of Drugs | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Included in WHO Essential Medicines List | 87 | 32% |

| Off-patent | 226 | 84% |

| Supported by in vitro evidence | 264 | 99% |

| Supported by in vivo evidence | 247 | 92% |

| Supported by human data (case reports, observational studies, or clinical trials) | 194 | 72% |

| Tested in clinical trials | 178 | 66% |

| Meeting all favorable criteria (WHO EML + off-patent + human data) | 67 | 25% |

Source: Adapted from ReDO_DB summary statistics [27]

These repurposing candidates originate from diverse therapeutic areas, with cardiovascular, nervous system, and alimentary tract medications being the most common sources, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Therapeutic Origins of Repurposing Candidates by ATC Classification

| Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Category | Number of Drugs |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular System | 56 |

| Nervous System | 49 |

| Alimentary Tract and Metabolism | 39 |

| Musculo-Skeletal System | 31 |

| Antiinfectives for Systemic Use | 26 |

| Dermatologicals | 23 |

| Genito Urinary System and Sex Hormones | 23 |

| Sensory Organs | 22 |

| Antiparasitic Products, Insecticides and Repellents | 20 |

Source: Adapted from ReDO_DB analysis [27]

Clinically Evaluated Repurposing Candidates

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide the highest quality evidence for repurposed drugs in oncology. Recent RCTs have evaluated several promising candidates:

Metformin: Originally an antidiabetic medication, metformin has been studied in various cancers including prostate, lung, and pancreatic malignancies. Its mechanisms involve activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), inhibition of mTOR signaling, and reduction of insulin-like growth factor levels [28].

Propranolol: This beta-blocker, used for cardiovascular conditions, has demonstrated potential in multiple myeloma and, when combined with etodolac, in breast cancer. Proposed mechanisms include inhibition of β-adrenergic signaling pathways that influence tumor growth and metastasis [28].

Mebendazole: An antiparasitic agent showing promise in colorectal cancer through tubulin polymerization inhibition and interference with glucose uptake in cancer cells [28].

Sulconazole: Originally an antifungal, sulconazole inhibits PD-1 expression in immune and cancer cells by blocking NF-κB and calcium signaling, representing an immunomodulatory approach [26].

Olaparib: While already approved for BRCA-mutant cancers, olaparib has shown potential for repurposing in lung cancer, demonstrating improved progression-free survival as monotherapy compared to combination regimens [26].

Computational Framework for Drug Repurposing

Virtual Screening Methodologies

Virtual screening (VS) comprises computational techniques to identify structures most likely to bind to drug targets from large libraries of small molecules [31]. The two primary approaches are structure-based and ligand-based methods, which can be integrated in hybrid frameworks for enhanced accuracy [31] [29].

Diagram 1: Computational virtual screening methodologies for drug repurposing

Integrated Repurposing Workflow

A systematic computational repurposing workflow combines multiple data sources and validation steps to identify high-probability drug-target matches for oncology applications.

Diagram 2: Integrated computational repurposing workflow for oncology

Experimental Protocols

Structure-Based Virtual Screening Protocol

Objective: Identify potential inhibitors for protein kinase CK2α, a crucial cancer target, through structure-based virtual screening.

Materials and Reagents:

- Molecular Target: Zea mays CK2α crystal structure (PDB ID: 4RLK)

- Compound Library: 5,000 small molecules for initial screening

- Software Tools: AutoDock Vina, AutoDock, Desmond Molecular Dynamics

- Computing Infrastructure: Linux cluster with batch queue processor

Procedure:

Target Preparation:

- Obtain 3D structure of CK2α from Protein Data Bank (4RLK)

- Remove water molecules and add polar hydrogen atoms

- Define binding site coordinates based on known active site residues

Molecular Docking:

- Perform initial screening of 5,000 compounds using AutoDock Vina

- Select top 50 compounds based on docking scores for refined analysis

- Execute refined docking with AutoDock using more precise parameters

- Analyze binding poses and interaction patterns (hydrogen bonds, π-stacking, hydrophobic interactions)

Molecular Dynamics Simulations:

- Run 100 ns simulations using Desmond with OPLS-2005 force field

- Analyze Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) for complex stability

- Calculate Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) for residue flexibility

- Monitor hydrogen bonding patterns throughout simulation trajectory

Hit Identification:

- Prioritize compounds demonstrating stable binding throughout MD simulation

- Select candidates with consistent protein-ligand interactions for experimental validation [32]

Computational Repurposing Database Screening Protocol

Objective: Systematically identify off-target repurposing opportunities using validated computational databases.

Materials and Reagents:

- Database Resources: Probe Miner (PM), Broad Institute Drug Repurposing Hub, TOPOGRAPH

- Validation Set: FDA-approved therapies with known biomarkers

- Analysis Tools: Custom scripts for data integration and scoring

Procedure:

Database Curation:

- Compile FDA-approved oncology drugs from Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling

- Manually curate drug-target combinations to ensure accuracy

- Filter for small molecule inhibitors (n=67) for repurposing analysis

Platform Validation:

- Use Probe Miner quantitative score (0-1 scale) to assess compound selectivity

- Apply inclusion threshold of PM quantitative score ≥0.25

- Calculate sensitivity and specificity for identifying known gene-targetable drugs

- Validate approach against known FDA-approved drug-biomarker combinations

Tumor Genomic Analysis:

- Sequence tumors using Illumina TruSight Oncology 500 or FoundationOne CDx panels

- Analyze 523 genes for single nucleotide variations and insertions/deletions

- Call amplifications with limit of detection of 2.2x fold change

- Determine microsatellite instability status and tumor mutational burden

Variant Classification:

- Review NGS reports for genomic variants of significance

- Classify variants as gain-of-function (GOF) or loss-of-function (LOF)

- Annotate pathogenic mutations with orthogonal functional validation

- Classify variants of unknown significance using FATHMM pathogenicity scoring

Repurposing Event Identification:

- Assess GOF mutations for targeting compounds across PM, Broad Institute DRH, and TOPOGRAPH

- Prioritize compounds not indexed in TOPOGRAPH and excluding FDA-approved biomarkers

- Validate predictions through experimental assays [33]

AI-Driven Drug Repurposing Protocol

Objective: Leverage artificial intelligence and machine learning to identify novel drug-disease relationships for oncology repurposing.

Materials and Reagents:

- AI Platform: Predictive Oncology's PEDAL platform (92% accuracy in tumor response prediction)

- Biobank Resources: 150,000+ tumor samples across 130+ cancer types

- Drug Library: ~150 FDA-approved drugs with known clinical indications

- Computing Infrastructure: AI servers with GPU acceleration

Procedure:

Data Integration:

- Construct knowledge graphs integrating drug-target-disease relationships

- Apply large language models (LLMs) to analyze biomedical literature

- Incorporate real-world medical data from electronic health records

- Integrate multi-omics data (transcriptomics, toxicogenomics, functional genomics)

Model Training:

- Train machine learning models on known drug response data

- Validate models using cross-validation techniques

- Optimize parameters to achieve >90% prediction accuracy

- Establish confidence thresholds for prediction reliability

Candidate Identification:

- Screen tumor samples against FDA-approved drug library

- Rank opportunities based on AI-predicted efficacy scores

- Prioritize candidates for diseases with unmet therapeutic needs

- Apply ensemble methods combining multiple AI approaches

Experimental Validation:

- Test top predictions using patient-derived tumor models

- Generate dose-response curves for prioritized drug-cancer pairs

- Validate mechanisms of action through pathway analysis

- Confirm selectivity and safety profiles [34]

Table 3: Computational Tools and Databases for Drug Repurposing

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Oncology Repurposing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Miner (PM) | Database | Indexes >1.8M compounds against 2,220 human targets with quantitative scoring | Identifies potent and selective compounds for specific proteins; validated for FDA-approved drug prediction |

| Broad Institute Drug Repurposing Hub | Database | Curated collection of repurposing candidates and their targets | Provides well-annotated compound-target relationships for hypothesis generation |

| TOPOGRAPH | Database | Maps drug-target interactions and polypharmacology | Filters out non-specific interactions to improve repurposing candidate quality |

| AutoDock Vina | Software | Molecular docking and virtual screening | Performs initial high-throughput screening of compound libraries against cancer targets |

| Desmond | Software | Molecular dynamics simulations | Assesses binding stability and conformational changes in protein-ligand complexes |

| TruSight Oncology 500 | Sequencing Panel | Analyzes 523 genes for variants, fusions, and splice variants | Comprehensive genomic profiling to identify targetable alterations in tumors |

| FoundationOne CDx | Sequencing Panel | Analyzes 324 genes with TMB and MSI assessment | FDA-approved comprehensive genomic profiling for therapy selection |

| PEDAL Platform | AI Tool | Predicts tumor response to drugs with 92% accuracy | AI-driven drug response prediction using extensive tumor biobank data |

Table 4: Key Chemical and Biological Reagents

| Reagent | Specifications | Experimental Role | Considerations for Repurposing Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDA-Approved Drug Library | ~150 compounds with diverse indications | Screening against tumor models | Prioritize off-patent compounds with favorable safety profiles |

| Patient-Derived Tumor Cells | 150,000+ samples across 130 cancer types | Ex vivo drug response testing | Maintain biological relevance and tumor heterogeneity |

| CK2α Protein | Zea mays crystal structure (PDB: 4RLK) | Structure-based screening target | Representative kinase model for cancer signaling pathways |

| Molecular Dynamics Force Field | OPLS-2005 parameters | Simulation of protein-ligand interactions | Balance between computational efficiency and physical accuracy |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | TSO-500 or FoundationOne CDx | Tumor genomic profiling | Ensure coverage of clinically actionable cancer genes |

Signaling Pathways in Drug Repurposing for Oncology

The efficacy of repurposed drugs in oncology often derives from their action on critical cancer signaling pathways. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for rational repurposing strategy design.

Diagram 3: Signaling pathways and mechanisms of action for repurposed drugs in oncology

Computational drug repurposing represents a transformative approach in oncology, offering accelerated pathways to new cancer therapies by leveraging existing pharmacological agents. The integration of structure-based virtual screening, AI-driven prediction platforms, and systematic database mining has created a robust framework for identifying high-probability repurposing candidates.

The promising clinical results from randomized controlled trials of drugs like metformin, propranolol, and mebendazole validate this computational approach [28]. Furthermore, the establishment of large-scale collaborations between organizations like Predictive Oncology and Every Cure demonstrates the growing recognition of computational repurposing as a viable strategy for addressing unmet needs in oncology [34].

As computational methods continue to evolve, particularly through advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning, the precision and efficiency of drug repurposing will further improve. The availability of extensive tumor biobanks, comprehensive genomic databases, and validated screening platforms creates an unprecedented opportunity to systematically explore the vast landscape of existing drugs for new anticancer applications. This approach promises to deliver safe, effective, and affordable cancer therapies in significantly reduced timeframes, ultimately benefiting patients through expanded treatment options and improved outcomes.

The identification of novel anticancer agents relies heavily on the screening of diverse chemical libraries to find compounds that can modulate specific biological targets. Publicly available chemical libraries and databases provide an indispensable resource for virtual screening (VS), a computational approach that dramatically reduces the time and financial costs associated with early drug discovery [35]. These libraries vary significantly in size, content, structural diversity, and design methodology, making the selection of appropriate screening collections crucial for successful hit identification [36]. Within the context of anticancer research, specifically targeting oncogenic drivers like the V600E-BRAF kinase—a key therapeutic target in melanoma, colorectal cancer, and thyroid cancer—the strategic use of these libraries enables researchers to efficiently identify potent inhibitors with superior pharmacokinetic properties [35].

The construction of virtual chemical libraries can be achieved through various methods, including using known reaction schemas with available reagents, functional group-based approaches, de novo design, molecular graph decoration, and morphing/transformation techniques [37]. This protocol outlines the key publicly available libraries, provides methodologies for their utilization in virtual screening workflows, and demonstrates their application through a case study on V600E-BRAF inhibitor identification.

Key Public Chemical Libraries and Databases

Major Public Compound Databases

Table 1: Major Public Compound Databases for Anticancer Virtual Screening

| Database Name | Key Characteristics | Size | Special Features | Relevance to Anticancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem | NCBI's repository of chemical molecules and their activities | 72+ million compounds (as exemplified by a specific anticancer set [35]) | Links to bioactivity data, screening assays, and toxicity information | Source of anticancer compounds with known biological activities [35] |

| ZINC15 | Curated collection of commercially available compounds for virtual screening | Over 100 million compounds (as of 2015) [36] | Includes 37 vendors offering >100,000 compounds each [36] | Foundation for building targeted screening libraries against cancer targets |

| ChEMBL | Manually curated database of bioactive drug-like molecules | Not specified in sources | Contains drug-like molecules with binding, functional ADMET data | Reference for similarity searches in anticancer library design [38] |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine Compound Database (TCMCD) | Natural products from Chinese medicinal herbs | 57,809 molecules [36] | High structural complexity and unique scaffolds [36] | Source of natural compounds with potential anticancer activity |

Specialized Anticancer Libraries

Table 2: Specialized Anticancer Screening Libraries

| Library Name | Composition | Design Methodology | Key Features | Cancer Targets/Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Chemicals Anticancer Library | 9,100 drug-like molecules [38] | 2D similarity search against ChEMBL and BindingDB with 80% similarity cut-off [38] | PAINS/reactive groups filtered; Ro5 compliance indicated [38] | 12,000 reference anticancer agents; various cancer cell lines and targets [38] |

| Life Chemicals Docking Set | 4,500 structurally diverse molecules [38] | Molecular docking against cancer-focused targets [38] | Focus on synthetically feasible compounds | MRP1, TNF targets [38] |

| CCSMD Database | Combinatorial library built from smart reaction modules [39] | Virtual synthesis through amide reactions [39] | High actual hit rate (76.92%) in validation [39] | Discovered CDK6 inhibitors with IC50 values ~1.3 μM [39] |

| Natural Product Libraries (e.g., Anticancer Bioscience) | 17,636 crude extracts, 1,211 fractions, 2,452 pure compounds [40] | Collection from Traditional Chinese Medicine herbs and plants [40] | Structural diversity unavailable in synthetic libraries [40] | Targets difficult to drug with synthetic compounds [40] |

DNA-Encoded Chemical Libraries (DELs)

DNA-encoded chemical libraries (DELs) represent a powerful alternative approach for hit identification, combining aspects of combinatorial chemistry with biological selection methods. These libraries consist of organic molecules covalently coupled to distinctive DNA fragments that serve as amplifiable barcodes, enabling the screening of millions to billions of compounds in a single test tube [41]. DELs can be categorized as either single pharmacophore libraries (one DNA fragment coupled to a chemical building block) or dual pharmacophore libraries (pairs of chemical building blocks attached to complementary DNA strands) [41]. The screening process involves incubating the DEL with an immobilized target protein, washing away non-binders, and identifying binding molecules through PCR amplification and high-throughput sequencing of the DNA barcodes [41].

Experimental Protocols for Virtual Screening

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening Using Molecular Docking

Application: Identification of potential V600E-BRAF kinase inhibitors [35]

Materials and Reagents:

- Target Structure: Crystal structure of V600E-BRAF (PDB code: 3OG7) [35]

- Compound Library: 72 anticancer compounds from PubChem database [35]

- Software Tools: Molecular docking software (e.g., Molegro Virtual Docker), structure visualization tool (e.g., Discovery Studio) [35]

- Reference Ligand: Vemurafenib (FDA-approved V600E-BRAF inhibitor) [35]

Procedure:

- Target Preparation:

Ligand Preparation:

Docking Validation:

Docking Simulation:

Interaction Analysis:

Diagram 1: Workflow for structure-based virtual screening of V600E-BRAF inhibitors

Protocol 2: Library Enumeration and Design Using Pre-validated Reactions

Application: Construction of virtual combinatorial libraries for anticancer screening [37]

Materials and Reagents:

- Chemical Reaction Schemas: Pre-validated or reported reactions (e.g., amide bond formation) [37] [39]

- Building Blocks: Commercially available chemical reagents [37]

- Software Tools: Open-source chemoinformatics tools (e.g., DataWarrior, KNIME) [37]

- Molecular Representation: SMILES, SMARTS, or InChI notations [37]

Procedure:

- Reaction Selection:

Building Block Selection:

Library Enumeration:

Library Characterization:

Library Filtering:

Diagram 2: Chemical library enumeration workflow using pre-validated reactions

Protocol 3: Analysis of Scaffold Diversity in Compound Libraries

Application: Comparative assessment of purchasable screening libraries for anticancer virtual screening [36]

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound Libraries: Standardized subsets of commercial libraries (e.g., Mcule, Enamine, ChemDiv) [36]

- Software Tools: Pipeline Pilot, Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), Tree Maps software [36]

- Analysis Methods: Murcko framework analysis, Scaffold Tree generation, RECAP fragmentation [36]

Procedure:

- Library Standardization:

Fragment Generation:

Diversity Assessment:

Visualization:

Library Selection:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Anticancer Virtual Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function | Application in Anticancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | PubChem, ZINC15, ChEMBL | Source of screening compounds and bioactivity data | Identification of compounds with known activity against cancer targets [35] |

| Cheminformatics Tools | DataWarrior, KNIME, Pipeline Pilot | Library enumeration, property calculation, and filtering | Design of targeted libraries against specific oncogenic targets [37] |

| Molecular Modeling Software | Molegro Virtual Docker, Spartan, MOE | Structure-based design, docking, and quantum calculations | Docking against cancer targets like V600E-BRAF kinase [35] |

| ADMET Prediction Platforms | SwissADME, pkCSM | Prediction of drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic properties | Optimization of anticancer candidates for favorable properties [35] |

| Specialized Screening Libraries | Life Chemicals Anticancer Library, Natural Product Libraries | Focused sets for specific target classes | Screening against cancer cell lines and specific oncogenic targets [38] [40] |

Case Study: Identification of V600E-BRAF Kinase Inhibitors

The V600E-BRAF mutation, present in 60% of melanomas and 10-70% of other cancers, represents a critical therapeutic target in oncology [35]. Despite the availability of FDA-approved inhibitors like dabrafenib and vemurafenib, resistance frequently emerges after 5-8 months of treatment, necessitating the discovery of novel chemotypes [35]. A recent study demonstrated the successful application of computational protocols to identify new V600E-BRAF inhibitors from a set of 72 anticancer compounds in the PubChem database [35].

Methodology Overview: Researchers employed an integrated in silico approach combining:

- Molecular docking simulation against V600E-BRAF crystal structure (PDB: 3OG7)

- Pharmacokinetic evaluation using SwissADME and pkCSM

- Density functional theory (DFT) computations for electronic structure analysis [35]

Results: The screening identified five top-ranked molecules (compounds 12, 15, 30, 31, and 35) with excellent docking scores (MolDock score ≥90 kcal molâ»Â¹, Rerank score ≥60 kcal molâ»Â¹) that formed hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with essential residues in the V600E-BRAF binding site [35]. DFT calculations revealed favorable frontier molecular orbital characteristics and reactivity parameters, while drug-likeness predictions indicated superior pharmacokinetic properties compared to existing inhibitors [35].

Significance: This case study demonstrates how publicly available chemical libraries, when screened with robust computational protocols, can yield promising hit compounds for further development as anticancer agents. The identified compounds showed potential as candidates for overcoming resistance to current V600E-BRAF inhibitors, highlighting the value of virtual screening in addressing challenging problems in oncology drug discovery [35].

Publicly available chemical libraries and databases provide an essential foundation for computational approaches to anticancer drug discovery. The strategic selection and application of these resources, combined with robust virtual screening protocols, can significantly accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic agents for oncology targets. As library enumeration methods continue to advance and new screening technologies like DNA-encoded libraries mature, the opportunities for discovering innovative cancer therapies through computational means will continue to expand. The protocols and resources outlined in this application note provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for leveraging these powerful approaches in their anticancer drug discovery efforts.

Computational Methodologies: AI, Docking, and Dynamics in Practice

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS), often used interchangeably with molecular docking, has become an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery pipelines [42] [43]. This computational approach predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a macromolecular target, typically a protein [44]. In the context of anticancer drug discovery, SBVS provides a rapid and cost-effective method to identify novel chemical entities from vast virtual libraries, significantly accelerating the hit identification phase [21]. The process fundamentally involves two core components: a search algorithm that explores possible ligand conformations and orientations within the target's binding site, and a scoring function that estimates the binding strength of each generated pose [45] [43]. The integration of these components into robust protocols allows researchers to prioritize a manageable number of compounds for experimental validation, making the drug discovery process more rational and efficient [46].

Key Components of a Docking Protocol

A successful SBVS campaign relies on the careful setup and execution of several interconnected steps. The diagram below illustrates the typical workflow.

Molecular Preparation

The initial and critical phase involves preparing the structures of both the target and the ligands.

- Target Preparation: The 3D structure of the protein target is most often obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [45] [47]. If an experimental structure is unavailable, computationally modeled structures (e.g., from AlphaFold) can be used [47]. Preparation typically involves:

- Adding missing hydrogen atoms and assigning protonation states to amino acid residues using tools like

PropKaorH++[45]. - Removing water molecules and original co-crystallized ligands, unless they are integral to binding.

- Adding partial atomic charges and optimizing the structure via energy minimization [47].

- Adding missing hydrogen atoms and assigning protonation states to amino acid residues using tools like

- Ligand Preparation: Small molecule structures are sourced from databases like ZINC, PubChem, or ChEMBL [45] [47]. Ligand preparation includes:

Binding Site Definition

Docking accuracy is greatly improved when the search is focused on a specific region of the protein. If the binding site is unknown (e.g., from a co-crystallized ligand), cavity detection programs like DoGSiteScorer, CASTp, or DeepSite can predict potential binding pockets [45] [47]. Performing a "blind docking" over the entire protein surface is computationally expensive and often less accurate [43].

Docking Execution: Search Algorithms and Scoring Functions

The core of SBVS involves generating and evaluating ligand poses.

- Search Algorithms: These algorithms explore the translational, rotational, and conformational degrees of freedom of the ligand within the defined binding site. They are broadly classified as follows [44] [45] [43]:

- Systematic Search: Explores torsional angles incrementally (e.g.,

FlexXuses incremental construction). - Stochastic Search: Uses random changes to find low-energy poses (e.g.,

AutoDock VinaandGOLDuse Monte Carlo and Genetic Algorithms, respectively). - Shape-Matching: Quickly fits the ligand to a defined cavity based on geometric and chemical complementarity [44].

- Systematic Search: Explores torsional angles incrementally (e.g.,

- Scoring Functions: These functions rank the generated poses by estimating the binding affinity. They fall into three main categories [48] [43]:

- Force Field-Based: Calculate energy terms based on molecular mechanics.

- Empirical: Use weighted sums of heuristic interaction terms.

- Knowledge-Based: Derive potentials from statistical analyses of known protein-ligand complexes in the PDB.

Table 1: Popular Molecular Docking Software and Their Key Characteristics

| Software | Search Algorithm | Scoring Function Type | License | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Iterated Local Search | Empirical / Knowledge-Based | Free (Apache) | [45] |

| GLIDE | Systematic + Optimization | Empirical | Commercial | [42] [45] |

| GOLD | Genetic Algorithm | Physics-based, Empirical, Knowledge-based | Commercial | [45] [3] |

| DOCK | Anchor-and-grow incremental construction | Physics-based | Academic | [42] [45] |

| RosettaVS | Genetic Algorithm | Physics-based (RosettaGenFF-VS) | Free (Rosetta) | [3] |

Advanced SBVS Protocols and Considerations

Accounting for Flexibility

A significant challenge in docking is treating molecular flexibility. While most protocols treat the receptor as rigid, this can limit accuracy. Advanced protocols incorporate flexibility through various methods [43] [47]:

- Side-chain Flexibility: Allowing side-chains in the binding site to rotate during docking.

- Ensemble Docking: Docking against multiple receptor conformations (e.g., from NMR or molecular dynamics simulations) to account for backbone movement [43].

- Induced-Fit Docking: More advanced (and computationally intensive) methods that explicitly model the conformational changes in the receptor upon ligand binding.

Target-Specific and Machine Learning Scoring

Generic scoring functions may not be optimal for all targets. The development of Target-Specific Scoring Functions (TSSFs) can significantly improve virtual screening performance [48]. Furthermore, machine learning and deep learning models are increasingly being integrated into docking pipelines. These models, such as DeepScore, can be trained on specific target data to better distinguish true binders from non-binders, potentially reducing false-positive rates [48] [45] [3].

Consensus Methods

To improve the reliability of hit selection, consensus scoring—using multiple scoring functions to rank compounds—is a widely adopted strategy. A compound that ranks highly across several different scoring functions is more likely to be a true active [48] [45].

Performance Evaluation and Experimental Validation

Evaluating Docking Performance

Before launching a prospective SBVS campaign, it is crucial to validate the chosen protocol. This is typically done using benchmarking datasets like the Directory of Useful Decoys: Enhanced (DUD-E) [48] [3]. Key metrics include:

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the concentration of true active compounds found in a top fraction of the ranked library compared to a random selection [49] [3].

- Area Under the Curve (AUC) of ROC: Represents the overall ability of the method to discriminate actives from inactives [49].

- Early Recognition Metrics: Metrics like BEDROC and RIE are designed to specifically reward methods that rank actives very early in the list, which is critical for practical VS [49].

Table 2: Common Metrics for Evaluating Virtual Screening Performance

| Metric | Description | Interpretation | Utility in VS |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC-ROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve | Overall ability to rank actives above inactives. Value of 0.5 is random; 1.0 is perfect. | Measures global performance but may not reflect early enrichment. |

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | Fraction of actives found in a top percentage (e.g., 1%) of the screened library vs. random. | An EF of 10 in the top 1% means a 10-fold enrichment over random. | Directly measures early enrichment, which is highly relevant for VS. |

| BEDROC / RIE | Exponentially weights the rank of actives to emphasize early recognition. | A single metric that focuses on early ranks. More sensitive to early performance than AUC. | Specifically designed to address the "early recognition" problem in VS. |

Experimental Validation

The ultimate test of any SBVS protocol is experimental validation. Promising computational hits must be procured or synthesized and tested in biochemical or cell-based assays [42]. A comprehensive validation cascade includes:

- In vitro binding/activity assays (e.g., measuring ICâ‚…â‚€, Káµ¢) to confirm potency [42].

- Cellular assays to demonstrate activity in a more physiologically relevant context [42] [21].

- Co-crystallization of the hit compound with the target protein, which provides the highest level of validation by confirming the predicted binding mode [42] [3].

Successful case studies, such as the discovery of hits against the ubiquitin ligase KLHDC2 and the sodium channel Naáµ¥1.7 using the RosettaVS protocol, underscore the power of well-validated SBVS approaches. In these studies, high-resolution X-ray crystallography confirmed the predicted docking poses, demonstrating remarkable agreement between computation and experiment [3].

Table 3: Key Resources for Structure-Based Virtual Screening

| Resource Category | Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold Database | Source for 3D atomic coordinates of target proteins, either experimentally determined or computationally predicted. |

| Small Molecule Databases | ZINC, PubChem, ChEMBL, DrugBank | Provide 2D or 3D structures of commercially available or known bioactive compounds for virtual screening libraries. |

| Structure Preparation Tools | UCSF Chimera, AutoDockTools, Open Babel, Schrodinger Maestro | Prepare protein and ligand structures for docking (add H atoms, assign charges, optimize hydrogen bonding). |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, GLIDE, GOLD, DOCK, RosettaVS | Core platforms that perform the conformational sampling (posing) and scoring of ligands. |

| Binding Site Prediction | DoGSiteScorer, CASTp, DeepSite, COACH | Predict potential binding pockets on a protein surface when the active site is unknown. |

| Benchmarking Sets | DUD-E, CASF-2016 | Standardized datasets used to validate and benchmark the performance of docking protocols and scoring functions. |

In the landscape of anticancer drug discovery, ligand-based computational approaches provide powerful tools for identifying and optimizing novel therapeutic candidates when the structural information of the biological target is limited or unavailable. These methods rely on the principle that molecules with similar structural or physicochemical properties often exhibit similar biological activities. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling and pharmacophore modeling represent two cornerstone methodologies in this domain, enabling researchers to distill critical features responsible for anticancer activity from known active compounds [11] [50]. Within the broader context of computational protocols for virtual screening, these ligand-based strategies offer a cost-effective and efficient solution for prioritizing compounds with a high likelihood of efficacy from extensive chemical libraries, thereby accelerating the early stages of anticancer drug development [51] [52].

Theoretical Background

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR)

QSAR is a computational methodology that correlates quantitative descriptions of molecular structure with a specific biological activity. The fundamental hypothesis is that a direct, quantifiable relationship exists between a compound's molecular properties and its biological response [11]. Once established, this mathematical model can predict the activity of new, untested compounds.

- Molecular Descriptors: These are numerical representations of a molecule's physicochemical properties. They can range from simple atomic counts to complex electronic or topological indices.

- Biological Activity Data: Typically expressed as IC50, Ki, or EC50 values, this data represents the potency of a series of compounds against a specific anticancer target or cell line.

- Statistical Modeling: Algorithms such as Partial Least Squares (PLS) or multiple linear regression are used to derive the mathematical relationship between the descriptors and the biological activity [11].

Pharmacophore Modeling

A pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [53]. In simpler terms, it is an abstract representation of the essential molecular features a compound must possess to bind to a target.

- Pharmacophoric Features: Common features include hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrophobic regions (H), and positive or negative ionizable groups [53] [54].

- Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation: This approach constructs the pharmacophore model based on a set of known active ligands. It identifies the common spatial arrangement of features shared among these diverse but active molecules, which is presumed to be responsible for their biological activity [53] [55].

Application Note 1: Ligand-Based 3D-QSAR Pharmacophore Modeling for Topoisomerase I Inhibitors

Background

DNA Topoisomerase I (Top1) is a well-validated anticancer target. While natural products like Camptothecin (CPT) and its derivatives are known Top1 poisons, they suffer from limitations such as instability and toxicity [55]. This application note details a protocol for discovering novel Top1 inhibitors using a 3D-QSAR pharmacophore model, virtual screening, and molecular docking.

Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Compound Selection and Dataset Preparation

- A diverse set of 62 CPT derivatives with known experimental IC50 values against the A549 lung cancer cell line was compiled from literature [55].