AI-Enhanced QSAR Modeling for Anticancer Drug Discovery: From Machine Learning to Clinical Translation

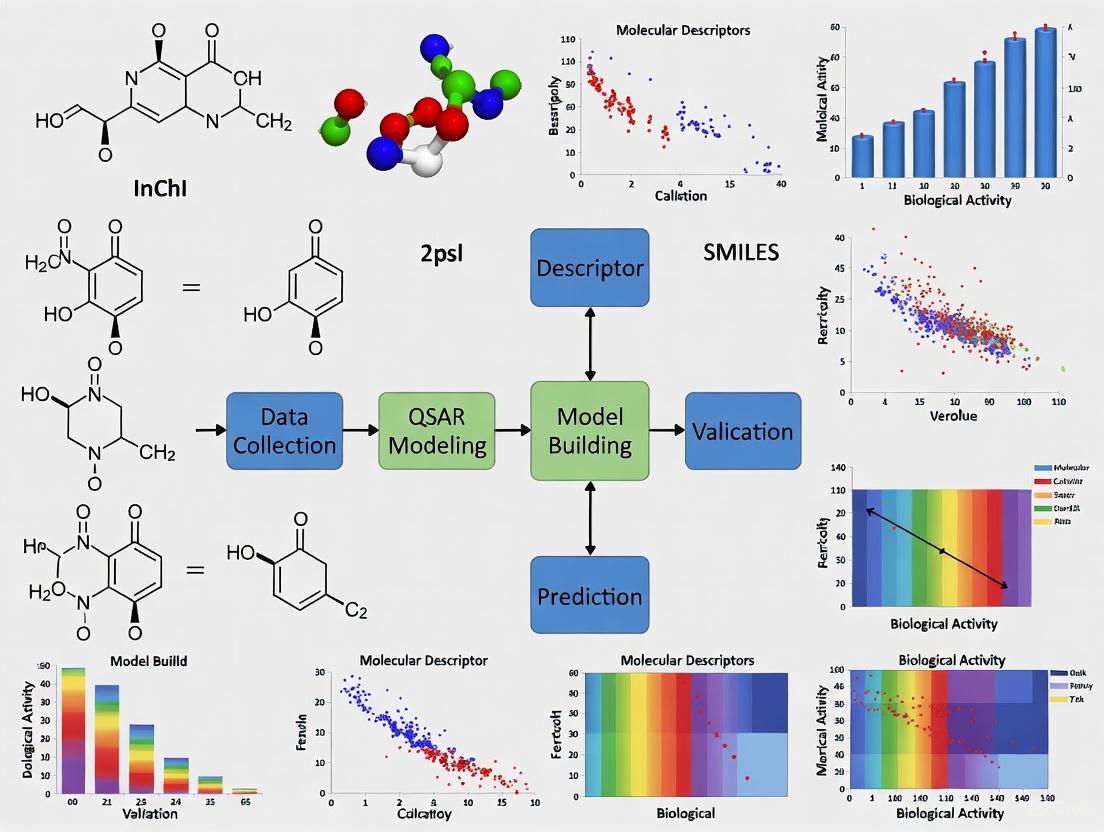

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling techniques for predicting anticancer activity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

AI-Enhanced QSAR Modeling for Anticancer Drug Discovery: From Machine Learning to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling techniques for predicting anticancer activity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, advanced machine learning methodologies, critical optimization strategies for real-world application, and rigorous validation frameworks. By integrating recent case studies on breast cancer, colon adenocarcinoma, and other cancers, the content demonstrates how AI-driven QSAR models, combined with molecular docking and ADMET prediction, are revolutionizing lead compound identification and optimization. The article also addresses paradigm shifts in model assessment for virtual screening and discusses future directions for integrating computational predictions with experimental validation to accelerate oncology drug development.

QSAR Foundations in Oncology: Principles, Molecular Descriptors, and Data Curation

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) is a computational methodology that correlates the chemical structure of compounds with their biological activity using mathematical models [1] [2]. The fundamental principle posits that the biological activity of a compound is determined by its molecular structure and can be expressed as a function of its physicochemical properties [3]. This relationship enables researchers to predict the biological activity of novel compounds without extensive laboratory testing, significantly accelerating the drug discovery process [2] [3].

In anticancer drug discovery, QSAR has emerged as an indispensable tool for identifying and optimizing potential chemotherapeutic agents [4] [5]. The approach allows medicinal chemists to understand which structural features contribute to cytotoxicity against specific cancer cell lines, guiding the rational design of more potent and selective anticancer compounds [4] [6]. The versatility of QSAR modeling is demonstrated by its successful application across diverse anticancer research domains, from traditional chemotherapeutic agents to modern targeted therapies [5] [6].

Fundamental Principles of QSAR

The QSAR Equation and Key Components

The mathematical foundation of QSAR is expressed by the general formula: Biological Activity = f(physicochemical properties and/or structural properties) + error [1]

This equation represents the relationship between a molecule's measurable characteristics (descriptors) and its biological effect, with the error term accounting for both model bias and observational variability [1]. The development of a reliable QSAR model depends on several critical components:

- Chemical Structures: A congeneric series of compounds with structural diversity

- Biological Activity Data: Experimentally determined values (e.g., IC₅₀, EC₅₀)

- Molecular Descriptors: Quantitative representations of structural and physicochemical features

- Statistical Methods: Algorithms to correlate descriptors with biological activity [3]

Types of Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors quantitatively capture various aspects of chemical structures and are categorized based on the structural information they encode [7]:

Table: Categories of Molecular Descriptors in QSAR Modeling

| Descriptor Category | Description | Examples | Applications in Anticancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical | Bulk properties related to molecular interactions | logP (lipophilicity), molecular weight, polar surface area | Predicting membrane permeability and bioavailability [2] |

| Electronic | Features describing electron distribution | Electronegativity, polarizability, HOMO/LUMO energies | Modeling interactions with enzyme active sites [4] |

| Steric/Topological | Structural shape and connectivity indices | Van der Waals volume, molecular connectivity indices | Correlating with steric hindrance in target binding [4] |

| Geometric | 3D spatial arrangement of atoms | Principal moments of inertia, molecular surface areas | 3D-QSAR studies using molecular fields [1] |

Historical Development of QSAR Approaches

QSAR methodologies have evolved significantly since their inception in the 1960s [7] [6]:

QSAR Workflow and Methodologies

Essential Steps in QSAR Modeling

The development of a robust QSAR model follows a systematic workflow with four critical stages [1]:

Statistical Methods and Machine Learning Algorithms

QSAR modeling employs diverse statistical approaches, ranging from traditional regression methods to advanced machine learning algorithms [5] [7]:

Traditional Statistical Methods:

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR): Establishes linear relationships between descriptors and activity [4] [2]

- Partial Least Squares (PLS): Handles datasets with correlated descriptors and more descriptors than compounds [1] [2]

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Reduces descriptor dimensionality while retaining essential information [5]

Machine Learning Approaches:

- Random Forest (RF): Ensemble method using multiple decision trees [5]

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Effective for nonlinear pattern recognition [1]

- Deep Neural Networks (DNN): Capable of learning complex relationships in high-dimensional data [5]

- Gradient Boosting Methods (XGBoost): High-performance ensemble technique [5]

Model Validation Techniques

Robust validation is essential to ensure QSAR model reliability and predictive power [1]:

- Internal Validation: Assesses model robustness using the training set (e.g., leave-one-out cross-validation) [1] [8]

- External Validation: Evaluates predictive ability using an independent test set not used in model development [1]

- Y-Randomization: Verifies absence of chance correlations by scrambling activity data [1]

- Applicability Domain: Defines the chemical space where the model provides reliable predictions [8]

QSAR in Anticancer Drug Discovery: Case Studies and Applications

Sulfur-Containing Anticancer Agents

A recent study demonstrated the power of QSAR in optimizing sulfur-containing compounds for anticancer activity [4]. Researchers evaluated 38 thiourea and sulfonamide derivatives against six cancer cell lines, identifying several promising candidates:

Table: Promising Sulfur-Containing Anticancer Compounds Identified Through QSAR

| Compound | Most Potent Cancer Cell Line | IC₅₀ Value (μM) | Key Structural Features | QSAR Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | HuCCA-1 (cholangiocarcinoma) | 14.47 | Fluoro-thiourea derivative | Mass and polarizability critical for activity |

| 14 | HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma) | 1.50 | Fluoro-thiourea derivative | Key predictors: electronegativity, van der Waals volume |

| 10 | MOLT-3 (lymphoblastic leukemia) | 1.20 | Thiourea derivative | Octanol-water partition coefficient essential |

| 22 | T47D (breast cancer) | 7.10 | Thiourea derivative | Presence of C-N bonds significant for activity |

The QSAR models developed in this study exhibited excellent predictive performance with training set correlation coefficients (Rtr) ranging from 0.8301 to 0.9636 and cross-validation coefficients (RCV) from 0.7628 to 0.9290 [4]. Key molecular descriptors identified included mass, polarizability, electronegativity, van der Waals volume, octanol-water partition coefficient, and frequency of specific chemical bonds (C-N, F-F, N-N) [4].

Combinatorial QSAR for Breast Cancer Treatment

A 2024 study explored combinational therapy for breast cancer using advanced QSAR approaches [5]. Researchers developed models to predict the combined biological activity of drug pairs (anchor drugs and library drugs) across 52 breast cancer cell lines. Among 11 machine learning and deep learning algorithms tested, Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) achieved superior performance with an R² value of 0.94 and RMSE of 0.255 [5].

This innovative approach demonstrated that QSAR can effectively predict synergistic drug combinations, potentially accelerating the development of effective combination therapies for highly heterogeneous cancers like breast cancer [5].

Protocol: Developing a QSAR Model for Anticancer Activity Prediction

Objective: To develop a validated QSAR model for predicting anticancer activity of novel compounds.

Materials and Reagents:

Table: Essential Research Tools for QSAR Modeling

| Category | Specific Tools/Software | Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure Software | ChemDraw Ultra, Spartan | Structure drawing and optimization | 3D geometry optimization, conformational analysis [8] |

| Descriptor Calculation | PaDEL, Dragon | Molecular descriptor generation | Calculation of 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors [8] |

| Statistical Analysis | MATLAB, R | Model development and validation | MLR, PLS, PCA algorithms [9] [2] |

| Machine Learning | Python Scikit-learn, TensorFlow | Advanced model development | Random Forest, SVM, Neural Networks [5] |

| Validation Tools | DatasetDivision1.2, KNIME | Model validation | Cross-validation, external validation [8] |

Experimental Procedure:

Step 1: Data Set Preparation

- Select a congeneric series of 20-50 compounds with known anticancer activity (IC₅₀ values) [4] [2]

- Convert biological activities to negative logarithmic scale (pIC₅₀ = -logIC₅₀) for linear modeling [8]

- Divide data set into training (80%) and test (20%) sets using Kennard-Stone algorithm [8]

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- Optimize 3D molecular structures using DFT methods (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G* basis set) [8]

- Calculate molecular descriptors using appropriate software (e.g., PaDEL, Dragon)

- Preprocess descriptors by removing constant values and highly correlated variables (VIF < 10) [8]

Step 3: Model Development

- Apply genetic function algorithm (GFA) for descriptor selection [8]

- Develop QSAR model using Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) with the equation: pIC₅₀ = C₀ + C₁×D₁ + C₂×D₂ + ... + Cₙ×Dₙ where C₀ is intercept, C₁...Cₙ are coefficients, D₁...Dₙ are descriptors [4]

- Validate model internally using leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation [8]

Step 4: Model Validation

- Assess predictive power using external test set [1]

- Calculate key statistical parameters: R², Q², R²predicted [8]

- Perform Y-randomization to verify absence of chance correlation [1]

- Define applicability domain using Williams plot [8]

Step 5: Model Application

- Use validated model to predict activity of novel designed compounds [4]

- Synthesize and test most promising candidates to verify predictions

- Iteratively refine model based on new experimental data

Relevance and Future Perspectives

QSAR modeling has become an integral component of modern anticancer drug discovery, offering significant advantages in terms of reduced development time and costs [3]. The approach enables researchers to prioritize the most promising candidates for synthesis and biological evaluation, effectively bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental validation [4] [5].

The future of QSAR in anticancer research is evolving toward more sophisticated approaches, including:

- Multi-target QSAR models addressing cancer heterogeneity and resistance mechanisms [5]

- Integration with other computational methods such as molecular docking and dynamics simulations [9]

- Advanced deep learning architectures capable of handling complex structure-activity relationships [5] [7]

- Universal QSAR models with expanded applicability domains across diverse chemical spaces [7]

As anticancer drug discovery faces increasing challenges with tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance, QSAR methodologies continue to adapt and provide valuable insights for designing next-generation therapeutics with improved efficacy and selectivity profiles [4] [6].

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations that translate the chemical information encoded within a molecular structure into standardized quantitative values [10]. In the context of anticancer drug discovery, these descriptors serve as critical variables in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, enabling researchers to correlate structural features with biological activity against specific cancer targets [11] [12]. The classification of descriptors into 1D, 2D, 3D, and 4D categories reflects increasing levels of structural complexity and conformational information, each contributing uniquely to the prediction of anticancer properties [11] [10]. For cancer target characterization, these descriptors help elucidate how structural features influence drug potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic profiles, thereby accelerating the development of novel therapeutic agents [13] [14].

The predictive capability of QSAR models hinges on appropriate descriptor selection. Studies across various cancer types—including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), melanoma, and colon cancer—demonstrate that comprehensive descriptor utilization can yield highly predictive models for anticancer activity [13] [14] [15]. With advances in machine learning and deep learning algorithms, the integration of multidimensional descriptors has further enhanced model accuracy, providing powerful tools for virtual screening and lead optimization in oncology drug development [11] [12].

Fundamental Concepts and Classification

Molecular descriptors are formally defined as "the final result of a logical and mathematical procedure, which transforms chemical information encoded within a symbolic representation of a molecule into a useful number or the result of some standardized experiment" [10]. These descriptors form the foundation of chemoinformatics by enabling quantitative analysis of structure-activity relationships essential for anticancer drug discovery [11].

Dimensional Classification of Descriptors: Molecular descriptors are categorized based on the level of structural representation they encode [11] [10]:

- 0D Descriptors: The simplest descriptors that consider molecular composition without connectivity information. Examples include atom counts, molecular weight, and molar refractivity [11] [10].

- 1D Descriptors: Account for presence of specific functional groups or substructures through binary indicators or frequency counts. These include hydrogen bond donors/acceptors and fragment counts [10].

- 2D Descriptors: Capture topological features derived from molecular graph representations, considering atom connectivity without spatial coordinates. Examples include topological indices and molecular fingerprints [11] [10].

- 3D Descriptors: Encode spatial and geometrical properties derived from three-dimensional molecular structures, including surface properties, volume, and quantum chemical descriptors [11] [10].

- 4D Descriptors: Incorporate ensemble averages from molecular dynamics simulations, accounting for conformational flexibility and interaction sampling over time [16] [11].

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Descriptors in QSAR Modeling

| Descriptor Dimension | Structural Information Encoded | Example Descriptors | Common Applications in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0D | Molecular composition | Atom counts, molecular weight | Preliminary screening, property calculation |

| 1D | Functional groups & fragments | Hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, presence of specific substructures | Rule-of-five screening, fragment-based design |

| 2D | Topological connectivity | Molecular fingerprints, topological polar surface area (TPSA) | High-throughput virtual screening, similarity analysis |

| 3D | Spatial & geometrical properties | Surface area, volume, quantum chemical properties | Binding affinity prediction, receptor-ligand complementarity |

| 4D | Conformational flexibility & dynamics | Grid cell occupancy descriptors (GCODs), interaction pharmacophore elements (IPEs) | Addressing induced-fit, flexible docking simulations |

For cancer target characterization, the appropriate selection of descriptor dimensions depends on the specific research question, with higher-dimensional descriptors typically providing more detailed information at the cost of increased computational complexity [10]. Research indicates that 2D descriptors often perform comparably to 3D descriptors in QSAR modeling while being significantly faster to compute, making them valuable for initial screening phases [10].

Detailed Descriptor Dimensions and Their Applications

1D Descriptors: Foundation-Level Characterization

1D descriptors provide fundamental molecular information derived from one-dimensional representations, focusing primarily on compositional and functional group features [10]. These descriptors are computationally efficient and serve as essential filters in early-stage anticancer drug discovery.

Key Types and Examples: Common 1D descriptors include molecular formula representation, SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor counts, rotatable bond counts, and presence indicators for specific chemical fragments [11] [10]. These descriptors effectively capture substructural features that influence drug-likeness and basic physicochemical properties.

Applications in Cancer Research: 1D descriptors are particularly valuable for initial compound filtering using rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, which helps identify compounds with favorable absorption and permeability characteristics [13]. In studies of tetrahydropyrazolo-quinazoline derivatives for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 1D descriptors helped establish baseline structure-activity relationships before proceeding to more complex analyses [13]. Similarly, in combinational QSAR models for breast cancer therapy, 1D descriptors provided foundational information for predicting synergistic effects between anchor and library drugs [12].

2D Descriptors: Topological Analysis for Cancer Targets

2D descriptors encode information about molecular connectivity and topology derived from the hydrogen-suppressed molecular graph, where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges [10]. These descriptors capture structural patterns that significantly influence biological activity while remaining computationally efficient.

Key Types and Examples: Important 2D descriptors include molecular fingerprints (e.g., MACCS keys, ECFP6), topological indices, connectivity measures, and graph invariants [11] [10]. Topological polar surface area (TPSA) is a particularly valuable 2D descriptor that correlates well with membrane permeability and bioavailability [10].

Applications in Cancer Research: 2D descriptors have demonstrated exceptional utility in QSAR modeling across various cancer types. In a study on NSCLC therapeutics, 2D-QSAR models developed with topological descriptors showed high predictive capability (R² = 0.798, Q²CV = 0.673) for antiproliferative activity against A549 cancer cell lines [13]. For anti-melanoma activity prediction, 2D descriptors enabled the development of robust QSAR models (R² = 0.864, Q²CV = 0.799) for SK-MEL-2 cell line inhibition [14]. Similarly, in colon cancer research, SMILES-based 2D descriptors combined with graph-based descriptors yielded highly predictive models (R²_validation = 0.90) for chalcone derivatives against HT-29 cell lines [15]. The efficiency and predictive power of 2D descriptors make them particularly suitable for high-throughput virtual screening of large compound libraries in anticancer drug discovery.

3D Descriptors: Spatial Modeling for Target Engagement

3D descriptors capture the spatial arrangement of atoms in three-dimensional space, providing critical information about molecular shape, steric interactions, and electronic properties that directly influence binding to cancer targets [17] [10]. These descriptors require generation of three-dimensional molecular structures with optimized geometry.

Key Types and Examples: 3D descriptors include steric and electrostatic parameters, quantum chemical descriptors (e.g., electrostatic potential, HOMO-LUMO energies), surface properties (van der Waals surface area, solvent-accessible surface area), and shape descriptors [17] [11]. Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) are popular 3D-QSAR approaches that use interaction field descriptors [16].

Applications in Cancer Research: 3D descriptors have proven valuable for understanding precise binding interactions with cancer-related targets. In hERG channel blocker prediction—a critical safety assessment in cancer drug development—3D-QSAR models utilizing quantum mechanical electrostatic potential (ESP) descriptors demonstrated superior predictive capability (R²test > 0.79 across molecular subsets) compared to 2D approaches [17]. For kinase inhibitors targeting NSCLC and other cancers, 3D descriptors help optimize selectivity and potency by mapping steric and electrostatic complementarity with ATP-binding sites [13]. The main challenge with 3D descriptors lies in the conformational analysis and molecular alignment, which can significantly impact model quality [17].

4D Descriptors: Incorporating Flexibility and Dynamics

4D descriptors extend beyond static 3D representations by incorporating molecular flexibility and temporal evolution through ensemble averaging or explicit dynamics simulations [16]. This "fourth dimension" accounts for conformational changes that occur during ligand-receptor interactions, providing a more realistic representation of binding processes.

Key Types and Examples: The core 4D descriptors include Grid Cell Occupancy Descriptors (GCODs), which represent the sampling frequency of different interaction pharmacophore elements (IPEs) within grid cells during molecular dynamics simulations [16]. Key IPE categories include: any atom (A), nonpolar (NP), polar-positive charge (P+), polar-negative charge (P-), hydrogen bond acceptor (HA), hydrogen bond donor (HB), and aromatic (Ar) [16].

Applications in Cancer Research: 4D-QSAR has successfully addressed challenging cancer targets where flexibility and induced-fit play crucial roles. The method has been applied to enzyme inhibitors relevant to cancer, including HIV-1 protease, p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38-MAPK), and 14-α-lanosterol demethylase (CYP51) [16]. In receptor-dependent (RD) 4D-QSAR, models are derived from multiple ligand-receptor complex conformations, explicitly simulating the induced-fit process with complete flexibility for both ligand and receptor [16]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for optimizing inhibitors against resistance mechanisms in cancer therapies, such as those addressing T790M mutations in EGFR for NSCLC treatment [13].

Diagram 1: 4D-QSAR Workflow for Cancer Target Characterization. This flowchart illustrates the key steps in developing 4D-QSAR models, from conformational sampling to final model validation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: 2D-QSAR Model Development for NSCLC Agents

Objective: To develop a predictive 2D-QSAR model for identifying potential therapeutic agents against non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) using topological descriptors [13].

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound dataset: 45 tetrahydropyrazolo-quinazoline and tetrahydropyrazolo-pyrimidocarbazole derivatives

- Biological activity: IC₅₀ values against A549 NSCLC cell line

- Software: Molecular modeling software for descriptor calculation, statistical package for regression analysis

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Convert IC₅₀ values to pIC₅₀ using the equation: pIC₅₀ = -log(IC₅₀ × 10⁻⁶) [13].

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute 2D topological descriptors for all compounds, including connectivity indices, electronic parameters, and steric factors.

- Dataset Division: Split compounds into training set (≈70-80%) for model development and test set (≈20-30%) for external validation.

- Model Building: Employ multiple linear regression or partial least squares (PLS) analysis to correlate descriptors with biological activity.

- Model Validation: Assess model quality using statistical parameters: R² (coefficient of determination), Q² (cross-validated R²), and R²ₜₑₛₜ (external validation) [13].

Expected Outcomes: A validated 2D-QSAR model with R² > 0.75 and Q² > 0.60, capable of predicting antiproliferative activity of new compounds against A549 NSCLC cell lines [13].

Protocol 2: 3D-QSAR with Quantum Mechanical Descriptors for hERG Inhibition

Objective: To develop a 3D-QSAR model for predicting hERG channel inhibition using quantum mechanical electrostatic potential descriptors [17].

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound dataset: 490 diverse organic compounds with experimental hERG pIC₅₀ values

- Software: Quantum chemistry package (for ESP calculations), molecular alignment tool, artificial neural network algorithm

Procedure:

- Structural Preparation: Generate optimized 3D structures for all compounds using appropriate quantum mechanical methods.

- Molecular Alignment: Perform pairwise 3D structural alignments by maximizing quantum mechanical cross-correlation with template molecules [17].

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute quantum mechanical electrostatic potential (ESP) descriptors for aligned molecules.

- Data Stratification: Divide dataset into subsets based on molecular weight ranges to improve alignment quality.

- Model Development: Employ artificial neural network (ANN) algorithm to establish relationship between ESP descriptors and hERG inhibitory activity.

- Model Validation: Validate using external test set and calculate R²ₜᵣₐᵢₙ and R²ₜₑₛₜ parameters [17].

Expected Outcomes: Highly predictive 3D-QSAR models with R²ₜₑₛₜ > 0.79 for each molecular weight subset, enabling reliable prediction of cardiotoxicity risk in cancer drug candidates [17].

Protocol 3: 4D-QSAR Analysis for Flexible Cancer Targets

Objective: To construct a 4D-QSAR model accounting for conformational flexibility in ligand-receptor interactions for cancer targets [16].

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound dataset: Series of enzyme inhibitors with known biological activity

- Software: Molecular dynamics simulation package, 4D-QSAR specialized software, genetic function algorithm

Procedure:

- Conformational Sampling: Generate conformational ensemble profile for each compound through molecular dynamics simulations [16].

- Grid Definition: Embed all compounds in a common 3D grid space with consistent dimensions and resolution.

- IPE Assignment: Classify atoms into Interaction Pharmacophore Elements (IPEs): any (A), nonpolar (NP), polar-positive (P+), polar-negative (P-), hydrogen bond acceptor (HA), hydrogen bond donor (HB), and aromatic (Ar) [16].

- GCOD Calculation: Calculate Grid Cell Occupancy Descriptors as occupancy frequencies of different IPEs in grid cells during MD simulations.

- Variable Selection: Apply Genetic Function Algorithm (GFA) to identify most relevant descriptors [16].

- Model Construction: Develop 4D-QSAR model using partial least squares (PLS) regression.

- Model Interpretation: Generate 3D pharmacophore maps identifying favorable and unfavorable interaction regions.

Expected Outcomes: A conformationally-aware QSAR model that identifies active conformations and key interaction elements for flexible cancer targets, with demonstrated applications for HIV-1 protease and p38-MAPK inhibitors [16].

Table 2: Key Statistical Parameters for QSAR Model Validation

| Statistical Parameter | Formula | Acceptance Criterion | Interpretation in Cancer QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² (Coefficient of Determination) | R² = 1 - (SSₑᵣᵣ/SSₜₒₜ) | > 0.6 | Goodness of fit for training set |

| Q² (Cross-Validated R²) | Q² = 1 - (PRESS/SSₜₒₜ) | > 0.5 | Internal predictive ability |

| R²ₜₑₛₜ (External Validation) | R²ₜₑₛₜ = 1 - (∑(yᵢ-ŷᵢ)²/∑(yᵢ-ȳ)²) | > 0.6 | External predictive ability |

| RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) | RMSE = √(∑(yᵢ-ŷᵢ)²/n) | Lower values preferred | Average prediction error |

| IIC (Index of Ideality of Correlation) | Complex formula based on correlation | > 0.7 | Model robustness for chalcone derivatives [15] |

Computational Workflow for Cancer Target Characterization

Diagram 2: Comprehensive QSAR Workflow for Anticancer Drug Discovery. This workflow illustrates the integrated process from data collection to experimental validation for cancer target characterization.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Molecular Descriptor Analysis in Cancer Research

| Research Tool | Type/Function | Application in Cancer Target Characterization |

|---|---|---|

| CORAL Software | QSAR Modeling Tool | Develops QSAR models using SMILES and graph-based descriptors; used for predicting anti-colon cancer activity of chalcones [15] |

| PadelPy Library | Python Descriptor Calculator | Calculates molecular descriptors for combinational QSAR models; applied in breast cancer combination therapy studies [12] |

| SWISSADME | Pharmacokinetic Prediction | Evaluates drug-likeness, absorption, and metabolism properties; used for NSCLC therapeutic agent profiling [13] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Conformational Sampling | Generates ensemble conformations for 4D-QSAR analysis; applied to flexible cancer targets like kinase enzymes [16] |

| DNN Algorithms | Deep Learning Framework | Develops complex non-linear QSAR models; achieved R² = 0.94 for breast cancer combination therapy prediction [12] |

| Genetic Function Algorithm | Variable Selection Method | Identifies most relevant molecular descriptors; used in 4D-QSAR model development for cancer targets [16] |

Multidimensional molecular descriptors provide complementary insights for cancer target characterization, with each dimension offering unique advantages for specific applications in anticancer drug discovery. The integration of 1D, 2D, 3D, and 4D descriptors in QSAR modeling has demonstrated significant predictive power across various cancer types, from non-small cell lung cancer and melanoma to breast and colon cancers [13] [14] [15]. As machine learning and deep learning algorithms continue to advance, the strategic selection and combination of appropriate descriptor dimensions will further enhance the accuracy and efficiency of virtual screening and lead optimization processes in oncology drug development [11] [12]. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this article provide researchers with practical frameworks for applying these powerful computational tools to characterize cancer targets and accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic agents.

The advancement of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling in anticancer activity prediction critically depends on access to high-quality, well-curated pharmacological and chemical data. Public databases such as the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) and ChEMBL provide comprehensive datasets that serve as foundational resources for developing robust machine learning models. These repositories address the pressing need in anticancer drug discovery to bypass time- and cost-exhaustive traditional processes through computational approaches [18]. Effective utilization of these resources requires systematic data sourcing, rigorous curation protocols, and appropriate modeling techniques to translate genomic and chemical information into predictive insights for drug sensitivity.

Database Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

Key Database Characteristics

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Pharmacogenomic Databases

| Database | Primary Focus | Key Data Types | Scale (Representative) | Unique Value Proposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDSC [18] [19] [20] | Cancer pharmacogenomics | Drug sensitivity (IC₅₀), genomic data (mutation, expression, CNV) | 297+ drugs; 1,000+ cell lines [18] | Large-scale drug screening across genetically characterized cancer cell lines |

| ChEMBL [21] [22] [23] | Bioactive drug-like molecules | Chemical structures, bioactivity, targets | Manually curated data on 1,000,000+ compounds | Broad coverage of drug-like properties and bioactivities |

| PharmacoDB [22] | Integrative meta-database | Unified drug response data from multiple studies | 759 compounds; 1,691 cell lines | Integrates multiple pharmacogenomic studies for robust comparison |

Data Composition and Applicability

The GDSC database provides extensive dose-response data across hundreds of cancer cell lines, with IC₅₀ values serving as the primary measure of compound efficacy [18] [19]. These pharmacological profiles are coupled with extensive genomic characterizations, including mutation data, gene expression, and copy number variations [22]. This combination enables researchers to correlate structural features of compounds with biological activity across genetically diverse cellular contexts.

ChEMBL contributes manually curated bioactivity data for small molecules, including calculated molecular properties and experimental results from scientific literature [21]. Its key strength lies in the standardized representation of chemical structures and their effects on biological targets, providing essential data for establishing structure-activity relationships [23].

PharmacoDB addresses a critical challenge in the field by integrating multiple disparate pharmacogenomic datasets (including GDSC, CCLE, CTRPv2) through rigorous curation of cell line and compound identifiers. This integration nearly triples the intersection of compounds available for analysis across studies, significantly enhancing the robustness of meta-analyses [22].

Experimental Protocols for Data Sourcing and Curation

Data Acquisition and Integration Workflow

Protocol: Sourcing Pharmacological Data from GDSC

Objective: Acquire and preprocess drug sensitivity data from GDSC for QSAR modeling.

Data Retrieval:

- Access GDSC data through the official portal (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/downloads/bulk_download) [19].

- Download the following key files:

GDSC1-datasetorGDSC2-dataset: Contains IC₅₀ values for drug-cell line combinations.Compounds-annotation: Provides compound identifiers, names, and targets.Cell-line-annotation: Details on cell line origins and characteristics [19].

Data Preprocessing:

- Apply activity cutoff: Filter out inactive compounds using an IC₅₀ threshold (e.g., 100 μM) to focus on biologically relevant responses [18].

- Transform values: Convert IC₅₀ to natural logarithmic scale (lnIC₅₀) to normalize the distribution for modeling.

- Handle missing data: Implement appropriate imputation strategies or remove entries with excessive missing values based on research objectives.

Structure Acquisition:

- Obtain compound structures using PubChem Compound IDs (CIDs) from the GDSC annotations.

- Download structures in Spatial Data File (SDF) format from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) [18].

- Convert 2D structures to 3D using toolkits like RDKit and perform energy minimization with force fields (e.g., MMFF94) [18].

Protocol: Curation and Descriptor Calculation

Objective: Generate uniform molecular representations and select relevant features for model development.

Descriptor Calculation:

- Use PaDEL software or the Padelpy library in Python to calculate 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors [18] [12].

- Compute diverse descriptor types including:

- Constitutional descriptors: Atom/bond counts, molecular weight

- Topological descriptors: Connectivity indices, molecular graphs

- Electronic descriptors: Partial charges, polarizability

- Geometric descriptors: Moment of inertia, molecular dimensions

- Binary fingerprints: Extended, Graph, Substructure fingerprints [18]

Descriptor Selection and Curation:

- Preprocess descriptors using the "RemoveUseless" function (WEKA) to eliminate non-informative features with no variation [18].

- Apply attribute evaluation (e.g., "CfssubsetEval") combined with search methods (e.g., "BestFirst" ranker) to select descriptors with high predictive power and low intercorrelation [18].

- Maintain appropriate drug-to-descriptor ratio (≥2:1) to minimize overfitting risk during model development [18].

Protocol: Cross-Database Integration

Objective: Maximize overlap between different pharmacogenomic datasets through identifier standardization.

Automated Matching:

- Perform exact case-insensitive matching of identifiers between datasets.

- Implement partial, programmatic matching algorithms to generate candidate matches for remaining identifiers.

Manual Curation:

- Review algorithm-generated matches manually to verify correctness.

- For unmatched compounds, use structural identifiers (SMILES, InChiKey, PubChem CID) or compound names to find matches in PubChem via WebChem R package [22].

- For unmatched cell lines, query Cellosaurus to generate candidate synonyms and attempt manual matching [22].

- Create new unique human-interpretable identifiers for any remaining entities [22].

QSAR Model Development and Validation Framework

Model Building Workflow

Modeling Approaches and Performance

Table 2: QSAR Modeling Approaches and Performance Metrics

| Modeling Approach | Best-Performing Algorithms | Reported Performance (R²) | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Drug QSAR [18] | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 0.609 - 0.827 (CRC cell lines) | Predicting drug activity against individual cancer cell types |

| Combinational QSAR [12] | Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | 0.94 (Breast cancer) | Predicting synergy of drug pairs in combination therapy |

| FGFR-1 Inhibitor Prediction [23] | Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | 0.7869 (Training)0.7413 (Test) | Target-specific inhibitor activity prediction |

| Integrative Chemical-Genomic [24] | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | MSE: 1.06 | Integrating SMILES and genomic profiles for response prediction |

Protocol: Model Development and Validation

Algorithm Selection and Training:

Validation Framework:

- Perform 10-fold cross-validation to assess model robustness and avoid overfitting [18]

- Evaluate using multiple statistical indices:

- Coefficient of determination (R²)

- Root mean square error (RMSE)

- Mean absolute error (MAE)

- Pearson's correlation coefficient (R) [18]

- Conduct external validation with completely independent test sets [23]

Model Interpretation:

- Calculate SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) values to understand descriptor contributions [18]

- Identify frequently occurring molecular descriptors (e.g., KRFP314 fingerprint in CRC models) [18]

- Perform recapitulation tests to verify model ability to reproduce known biological relationships (e.g., drug-to-oncogene associations) [18]

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for QSAR Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| PaDEL Software [18] | Molecular descriptor calculation | Calculates 1D, 2D, 3D descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures |

| RDKit [18] | Cheminformatics and machine learning | Chemical structure manipulation, 3D conversion, and descriptor calculation |

| WEKA [18] | Machine learning algorithms | Feature selection, descriptor evaluation, and preliminary modeling |

| Scikit-learn [18] [12] | Machine learning in Python | Model implementation, cross-validation, and performance evaluation |

| GDSC Database [18] [19] | Pharmacogenomic data source | Primary source of drug sensitivity and genomic data for cancer cell lines |

| ChEMBL [21] [23] | Bioactive compound data | Source of compound structures, bioactivities, and target information |

| PharmacoDB [22] | Integrated pharmacogenomics | Meta-analysis across multiple drug screening studies |

| Super-PRED [18] | Drug target prediction | Identifying potential protein targets for active compounds |

| REACTOME [18] | Pathway analysis | Mapping drug targets to biological pathways and processes |

Application Case Study: Anti-Colorectal Cancer Drug Prediction

A practical implementation of these protocols demonstrated the identification of potential anti-CRC drugs through the following workflow:

- Data Sourcing: 297 anticancer drugs with lnIC₅₀ values across 12 CRC cell lines from GDSC [18]

- Descriptor Calculation: 1,875 chemical descriptors computed using PaDEL from 3D optimized structures [18]

- Model Development: SVM-based QSAR models achieving R² = 0.609-0.827 after 10-fold cross-validation [18]

- Drug Repurposing: Prediction of FDA-approved drug activity using developed models, identifying viomycin and diamorphine as potential anti-CRC candidates [18]

- Target and Pathway Analysis: Using Super-PRED and REACTOME to elucidate mechanisms of action and pathway associations [18]

- Resource Deployment: Integration of models into the "ColoRecPred" web server for community access (https://project.iith.ac.in/cgntlab/colorecpred) [18]

This case study exemplifies the complete translational pipeline from data curation to actionable drug discovery resources, demonstrating the power of integrated database utilization in accelerating anticancer drug development.

In anticancer research, the "chemical space" encompasses the multi-dimensional descriptor space that defines the structural and property-based relationships among a collection of compounds. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) is a critical first step for visualizing this space and understanding its Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR), which informs the development of predictive Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. The "activity landscape" is a conceptual model for visualizing and analyzing the relationship between chemical structure and biological activity, wherein "activity cliffs" are a key feature—defined as pairs of structurally similar compounds that exhibit a large difference in potency [25]. The identification of these cliffs is crucial, as they highlight areas where the SAR is discontinuous and can reveal critical structural features responsible for drastic changes in anticancer activity, thereby preventing false predictions in subsequent QSAR models [25].

Key Concepts and Definitions

The following table defines the core concepts used in the analysis of chemical space and activity landscapes.

Table 1: Core Concepts in Chemical Space and Activity Landscape Analysis

| Concept | Definition | Relevance to Anticancer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Space | The multi-dimensional space defined by molecular descriptors or fingerprints of a compound set, representing their structural and physicochemical relationships [25]. | Provides a global overview of the structural diversity and coverage of screened compound libraries, guiding the selection of representative compounds for further screening. |

| Activity Landscape | A conceptual model that visualizes the relationship between chemical similarity and biological activity for a set of compounds [25]. | Helps in understanding the overall SAR of a dataset, identifying smooth regions (continuous SAR) and critical discontinuities. |

| Activity Cliff | A pair of compounds that are structurally highly similar but have a large difference in their biological activity [25]. | Pinpoints specific molecular modifications that lead to drastic changes in anticancer potency, offering insights for lead optimization and scaffold hopping. |

| Activity Cliff Generator | A compound that is involved in forming activity cliffs with multiple other compounds in the dataset [25]. | Identifies privileged or problematic substructures that are highly sensitive to minor modifications, which is critical for medicinal chemistry decisions. |

| Structural Similarity | A quantitative measure of the resemblance between two chemical structures, often calculated using molecular fingerprints like ECFP or FCFP and a similarity metric such as Tanimoto coefficient [26] [25]. | Serves as the foundation for comparing compounds and mapping the structure-activity landscape. |

Experimental Protocol for Activity Landscape Analysis

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for performing an activity landscape analysis on a dataset of compounds with recorded anticancer activity, adapted from established computational workflows [25].

Phase 1: Data Curation and Preparation

Objective: To assemble a clean, standardized, and well-annotated dataset ready for analysis.

- Data Collection: Compile a dataset of compounds with associated experimental anticancer activity measures (e.g., IC50, GI50). Data can be sourced from public databases like NCI-60 or published literature.

- Structure Standardization:

- Remove duplicate structures and inorganic compounds.

- For salts, retain the largest organic neutral counterpart.

- Standardize tautomers and protonation states to a consistent form.

- Activity Annotation: Express the biological activity on a consistent scale (e.g., -logIC50 for potency). Categorize compounds as active, inactive, or intermediate based on predefined thresholds if a classification model is the end goal.

Phase 2: Chemical Space Visualization and Clustering

Objective: To explore the global diversity of the dataset and identify inherent chemical clusters.

- Molecular Descriptor/Fingerprint Calculation: Generate chemical fingerprints for all curated compounds. Recommended fingerprints include:

- Similarity Matrix Calculation: Compute the pairwise structural similarity (e.g., Tanimoto similarity) for all compounds in the dataset using the selected fingerprints.

- Dimensionality Reduction and Visualization:

- Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the similarity matrix or fingerprint matrix to reduce dimensionality.

- Generate a 2D or 3D scatter plot using the first two or three principal components to visualize the chemical space.

- Chemical Clustering:

- Perform clustering analysis (e.g., using the Louvain community detection method on a chemical similarity network) to identify groups of structurally related compounds [25].

- Visually inspect the PCA plot to confirm that the clusters are spatially separated in the chemical space.

Phase 3: Activity Landscape Modeling and Cliff Identification

Objective: To map the structure-activity relationships and identify significant activity cliffs.

- Structure-Activity Similarity (SAS) Map Construction:

- For all compound pairs, plot their structural similarity (X-axis) against their absolute activity difference (Y-axis) [25].

- Visually identify activity cliffs as data points in the upper-left quadrant of the SAS map (i.e., high structural similarity paired with high activity difference).

- Quantitative Activity Cliff Identification with SALI:

- For each pair of compounds, calculate the Structure-Activity Landscape Index (SALI) score using the formula:

SALI(i,j) = |Activity(i) - Activity(j)| / (1 - Similarity(i,j))[25] - Define a SALI score threshold to classify compound pairs as activity cliffs. A high SALI score indicates a cliff.

- For each pair of compounds, calculate the Structure-Activity Landscape Index (SALI) score using the formula:

- Consensus Cliff Identification: Overlay the activity cliffs identified from the SAS map onto a SALI heatmap to compare and confirm the results from both methodologies [25].

- Activity Cliff Generator Analysis: Identify "activity cliff generators," which are compounds that form activity cliffs with multiple partners, by counting the frequency of each compound's involvement in cliff pairs [25].

Phase 4: Interpretation and Reporting

Objective: To derive chemically and biologically meaningful insights from the analysis.

- Structural Categorization: Classify the identified activity cliff pairs into categories based on the type of structural change (e.g., single atom replacement, functional group change, ring variation) [25].

- Cluster Enrichment Analysis: Determine if the activity cliffs are enriched within specific chemical clusters identified in Phase 2.

- Reporting: Document all findings, including visualizations (PCA plots, SAS maps, SALI heatmaps), lists of activity cliffs and generators, and their structural interpretations.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and data resources required for performing the activity landscape analysis described in this protocol.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EDA

| Item | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit for manipulating chemical structures and generating molecular descriptors [26]. | Used for structure standardization, fingerprint calculation (ECFP, FCFP), and similarity metric computation. |

| Python with scikit-learn | A programming language and a machine learning library that provides implementations of various algorithms [26]. | Used for performing PCA, clustering, and general data analysis and visualization. |

| PubChem Bioassay Database | A public repository of biological assays and their results for a vast number of chemicals [26]. | A potential source for obtaining experimental anticancer activity data for compounds of interest. |

| Chemical Similarity Network | A graph where nodes represent compounds and edges represent significant structural similarity between them [25]. | Used for clustering compounds and visualizing relationships, aiding in the identification of chemical neighborhoods that may contain activity cliffs. |

| SAS Map Plot | A 2D scatter plot visualizing the relationship between structural similarity and activity difference for all compound pairs [25]. | The primary visual tool for the global assessment of the activity landscape and initial identification of activity cliffs. |

| SALI Score Algorithm | A numerical method to quantify the "cliff-ness" of a compound pair based on their activity difference and structural similarity [25]. | Provides a quantitative and objective metric to complement the visual inspection of the SAS map for robust cliff identification. |

Workflow and Data Visualization Diagrams

The pursuit of novel anticancer agents is increasingly guided by computational methodologies that enhance the efficiency and rational design of drug discovery. This application note details the integration of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling with complementary in silico techniques for the identification and optimization of inhibitors against three critical molecular targets in oncology: Aromatase, Tankyrase, and Tubulin. We provide a structured overview of successful applications, summarized quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential reagent solutions to facilitate research in this domain. The focus is on providing actionable methodologies for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in anticancer activity prediction.

QSAR Modeling Applications for Key Oncological Targets

Aromatase Inhibitors for Breast Cancer Therapy

Aromatase, a cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP19A1), is the rate-limiting enzyme in estrogen biosynthesis and a well-validated target for hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer. Inhibition of aromatase lowers estrogen production, which is the growth driver for these cancer cells [27].

- QSAR Model Specifications: A robust 3D-QSAR model was developed for a diverse set of 299 inhibitors (175 steroidal and 124 azaheterocyclic compounds). The model incorporated a hydrophobicity density field and the smallest dual descriptor Δf(r)S to quantitatively account for hydrophobic contacts and nitrogen–heme–iron coordination, respectively [28].

- Key Molecular Descriptors: Analysis revealed that hydrophobic interactions are the primary determinant for steroidal inhibitor potency, whereas coordination with the heme-iron is critical for azaheterocyclic compounds. Additional hydrogen bonds with Asp309 and Met375 significantly enhance binding affinity [28].

- Experimental Validation: A separate study on indole derivatives utilized a SOMFA-based 3D-QSAR model, which demonstrated a high correlation coefficient and excellent predictive ability. The model's reliability was confirmed through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations over 100 ns, which showed stable binding of the designed inhibitors within the aromatase active site [29].

Table 1: Summary of QSAR Studies on Aromatase Inhibitors

| Study Focus | Dataset Size | Key Descriptors/Features | Statistical Performance | Validation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroidal & Azaheterocyclic Inhibitors [28] | 299 compounds | Hydrophobicity density, Heme-iron coordination, H-bond with Asp309/Met375 | N/A | Flexible Docking, Internal Validation |

| Indole Derivatives [29] | N/A | Shape & Electrostatic fields from SOMFA | High correlation | Molecular Docking, 100 ns MD Simulation |

| General Review of AI QSAR [27] | N/A (Comprehensive Review) | Various steric and electronic features | Varies by study | Highlights need for robust models |

Tankyrase Inhibitors in Wnt/β-Catenin-Driven Cancers

Tankyrase (TNKS1 and TNKS2), part of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) family, regulates the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by promoting the degradation of Axin. Inhibition of tankyrase stabilizes Axin, leading to the breakdown of β-catenin, and is a promising strategy for cancers like colon adenocarcinoma [30] [31].

- Machine Learning-QSAR Hybrid Model: A study on 1100 TNKS inhibitors from the ChEMBL database employed a Random Forest classification model. The model utilized 2D and 3D molecular descriptors and achieved a high predictive performance with a ROC-AUC of 0.98. This model successfully identified the PARP inhibitor Olaparib as a potential tankyrase inhibitor for repurposing in colorectal cancer [31].

- 3D-QSAR for Flavone Analogs: A field point-based 3D-QSAR model was built for flavone analogs, showing strong descriptive and predictive capability (r² = 0.89, q² = 0.67). The model guided the virtual screening of 8000 flavonoids, identifying 1480 with predicted IC50 < 5 µM. Subsequent molecular docking and ADMET profiling narrowed this down to 8 top-hit leads with low nanomolar predicted activity [32].

- Virtual Screening Workflow: A protocol combining molecular docking, ML-based scoring, and ADMET prediction screened a library of 1.7 million compounds. From 7 candidates tested in vitro, two compounds (A1 and A3) showed TNKS2 inhibitory activity with IC50 values of <10 nM and <10 µM, respectively [30].

Table 2: Summary of QSAR and Computational Studies on Tankyrase Inhibitors

| Study Focus | Dataset/Scale | Core Methodology | Key Outcome | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavone Analogs [32] | 87 compounds (Training); 8000 screened | 3D-QSAR (Field-based) | 8 top hits with IC50 ~0.6-3.98 µM | Docking, ADMET, In vitro assay proposed |

| Machine Learning Screening [31] | 1100 inhibitors from ChEMBL | Random Forest QSAR | Identified Olaparib as repurposing candidate | Docking, MD Simulation, Network Pharmacology |

| Structure-Based Virtual Screening [30] | 1.7 million compounds | Docking, ML scoring, ADMET | 2 active compounds (A1: IC50 <10 nM) | In vitro immunochemical assay |

Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors

Tubulin, the subunit protein of microtubules, is a classic target for anticancer therapy. Inhibitors like Combretastatin A-4 (CA-4) bind to the colchicine site, disrupting microtubule dynamics and leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [33] [34] [35].

- 3D-QSAR for CA-4 Analogues: A combined 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and MD simulation study on CA-4 analogues produced highly predictive CoMFA (q² = 0.724, r² = 0.974) and CoMSIA (q² = 0.710, r² = 0.976) models. These models were used to design new analogues with predicted high activity, and the detailed binding mode was confirmed by 30 ns MD simulations [33].

- QSAR on 1,2,4-Triazine-3(2H)-one Derivatives: Research on tubulin inhibitors for breast cancer developed a QSAR model using a dataset of 32 compounds. The model, based on descriptors like absolute electronegativity (χ) and water solubility (LogS), achieved a predictive accuracy (R²) of 0.849. The top-designed compound, Pred28, exhibited a high docking score (-9.6 kcal/mol) and formed a stable complex in 100 ns MD simulations [34].

- Pharmacophore-Based 3D-QSAR for Quinolines: A study on cytotoxic quinolines identified a six-point pharmacophore model AAARRR.1061 (three hydrogen bond acceptors and three aromatic rings) as optimal for tubulin inhibitory activity. The model showed strong statistical quality (R² = 0.865, Q² = 0.718) and was used for database screening, identifying a compound with a high docking score of -10.95 kcal/mol [36].

Table 3: Summary of QSAR Studies on Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors

| Study Focus | Dataset | Model Type | Statistical Performance | Key Validation Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA-4 Analogues [33] | N/A | 3D-QSAR (CoMFA/CoMSIA) | q²=0.724/0.710; r²=0.974/0.976 | 30 ns MD Simulation |

| 1,2,4-Triazine-3(2H)-one Derivatives [34] | 32 compounds | QSAR (MLR) | R² = 0.849 | Docking, 100 ns MD Simulation |

| Cytotoxic Quinolines [36] | 62 compounds | 3D-QSAR (Pharmacophore) | R² = 0.865, Q² = 0.718 | Molecular Docking, Y-Randomization |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Development of a Predictive 3D-QSAR Model

This protocol outlines the general workflow for building a 3D-QSAR model, as applied in the studies on aromatase, tankyrase, and tubulin inhibitors [36] [28] [32].

- Dataset Curation: Compile a set of compounds with consistent experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC50). Convert IC50 values to pIC50 (-logIC50) for analysis. A typical ratio of 80:20 for training set to test set is used to ensure robust model training and external validation [34].

- Ligand Preparation and Conformational Analysis: Draw or retrieve 2D structures of all compounds. Use software like ChemBioOffice or Maestro/LigPrep to generate 3D structures. Optimize geometries using force fields (e.g., MMFF94x, OPLS_2005). For each molecule, generate a representative set of low-energy conformations [36] [32].

- Molecular Alignment: This is a critical step. Align all molecules to a common reference, often the most active compound or a co-crystallized ligand, using methods like Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) or field-based alignment [32].

- Descriptor Calculation and Model Building: Calculate 3D molecular field descriptors (e.g., steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic) around the aligned molecules. Use partial least squares (PLS) regression to build a model correlating these descriptors with the biological activity [36].

- Model Validation: Rigorously validate the model using:

- Internal Validation: Calculate cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) using methods like leave-one-out.

- External Validation: Predict the activity of the withheld test set and calculate the predictive R².

- Y-Randomization: Scramble the activity data and rebuild models to confirm the original model is not based on chance correlation [36].

Protocol 2: Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow for Novel Inhibitor Identification

This protocol combines multiple computational techniques for a high-probability identification of novel hit compounds, as demonstrated in tankyrase and tubulin research [30] [31] [32].

- Molecular Docking-Based Primary Screening: Perform semi-rigid or flexible molecular docking of a large compound library (e.g., ZINC) into the target's binding site. Use scoring functions (e.g., Vinardo in Smina) to rank compounds by predicted binding affinity. Select the top-ranking compounds for further analysis [30].

- Machine Learning and QSAR Filtering: Apply a pre-validated QSAR or machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest) to the docking hits. This filters for compounds with predicted biological activity, moving beyond just binding affinity [31].

- ADMET and Physicochemical Profiling: Screen the remaining compounds for desirable drug-like properties. Use QSPR/QSAR models to predict key parameters such as LogP (lipophilicity), water solubility, human intestinal absorption, and hERG-mediated cardiac toxicity risk. Eliminate compounds with poor predicted profiles [30] [32].

- Expert Analysis and Consensus Selection: Manually inspect the shortlisted compounds to eliminate potentially reactive, unstable, or excessively complex structures (e.g., PAINS). Use consensus scoring from the previous steps to select a final, manageable number of compounds (e.g., 5-10) for in vitro testing [30].

- Experimental Validation: Procure the selected compounds and evaluate their inhibitory activity against the target protein using standardized in vitro assays, such as immunochemical assays for tankyrase or tubulin polymerization assays [30] [34].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Tankyrase in the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates how Tankyrase promotes the degradation of Axin, leading to the stabilization of β-catenin and subsequent activation of oncogenic gene transcription. Inhibiting Tankyrase restores the destruction complex's ability to degrade β-catenin.

Diagram 2: Integrated QSAR and Virtual Screening Workflow. This flowchart outlines the sequential steps for developing a validated QSAR model and applying it, in combination with docking and ADMET profiling, to identify novel inhibitors for experimental testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Oncology

| Reagent / Software Solution | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Comprehensive software suite for QSAR, molecular modeling, and simulation. | Used for structure preparation, energy minimization, and 3D-QSAR model development for aromatase inhibitors [28]. |

| Schrodinger Suite (Maestro, LigPrep, Phase) | Integrated platform for drug discovery, including ligand preparation, pharmacophore modeling, and docking. | Employed for generating pharmacophore hypotheses and 3D-QSAR models for quinoline-based tubulin inhibitors [36]. |

| Gaussian 09W | Software for electronic structure calculations, including Density Functional Theory (DFT). | Used to compute quantum chemical descriptors (e.g., HOMO/LUMO energies) for QSAR studies on 1,2,4-triazine derivatives [34]. |

| Forge | Software for field-based 3D-QSAR, activity prediction, and virtual screening. | Utilized to build field point-based 3D-QSAR models for flavone analogs as tankyrase inhibitors [32]. |

| ICM-Pro | Software for molecular docking, model building, and virtual screening. | Applied for flexible docking studies of steroidal aromatase inhibitors to account for protein flexibility [28]. |

| CHEMBL Database | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | Served as the source for a dataset of 1100 known tankyrase inhibitors to build a machine learning QSAR model [31]. |

| ZINC Database | Free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Used as a source library (~1.7 million compounds) for virtual screening of novel tankyrase inhibitors [30]. |

Advanced QSAR Methodologies: Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Integrative Approaches

Application Notes

The integration of machine learning (ML) with Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling has revolutionized the early stages of anticancer drug discovery. These data-driven approaches leverage computational power to predict the biological activity of molecules, significantly accelerating the identification and optimization of lead compounds. By establishing relationships between molecular descriptors (numerical representations of chemical structures) and anticancer activity, ML-driven QSAR models enable the virtual screening of vast chemical libraries, reducing the reliance on costly and time-consuming experimental screens alone [37]. Among the various algorithms employed, Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) have emerged as particularly robust and widely used methods for building predictive models in cancer research.

The following table summarizes the documented performance of these three algorithms in recent QSAR studies focused on predicting anticancer activity.

| Algorithm | Reported Performance in Anticancer QSAR Studies | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | R²: 0.820-0.835 on test sets; Cross-validation R² (Q²): 0.744-0.770 [38]. MCC of 0.49-0.71 in classification tasks [39]. | - Prediction of cytotoxicity of flavone analogs against breast (MCF-7) and liver (HepG2) cancer cell lines [38].- Discriminating EGFR inhibitors from non-inhibitors across diverse molecular scaffolds [39]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Accuracy: 90.40%; Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC): 0.81 [40]. Overall accuracy of 76.6-77.9% for 5-LOX inhibitor prediction [41]. | - Classification of anticancer vs. non-anticancer molecules screened against NCI-60 cancer cell lines [40].- Developing classification models for 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) inhibitors, a target in cancer-related inflammation [41]. |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) | Overall accuracy of 76.6% (training) and 77.9% (test set) when k=5 [41]. | - Used with Information Gain-filtered descriptors to build a robust QSAR classification model for 5-LOX inhibitors [41]. |

Key Advantages in Anticancer Research

Random Forest is highly regarded for its robustness against overfitting and its ability to handle high-dimensional descriptor data without requiring intensive preprocessing. It also provides intrinsic feature importance rankings, which help medicinal chemists identify key structural motifs influencing anticancer activity. For instance, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis on RF models can reveal which molecular descriptors are most critical for cytotoxicity [38] [42].

Support Vector Machine is powerful for non-linear classification problems, often encountered in complex bioactivity data. It performs well even with a moderate number of samples, making it suitable for datasets of thousands of compounds [40] [41].

k-Nearest Neighbors is a simple, intuitive, yet effective algorithm that leverages the principle of chemical similarity. It assumes that structurally similar molecules are likely to have similar biological activities, a cornerstone concept in cheminformatics [41].

Protocols

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for developing a robust QSAR classification model for anticancer activity prediction, adaptable for use with RF, SVM, or k-NN algorithms.

Protocol 1: Development of a Classification QSAR Model for Anticancer Activity

Objective: To build a machine learning model that classifies small molecules as anticancer active or inactive.

Experimental Workflow:

Step 1: Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Source a publicly available bioactivity dataset. For example, use the NCI-60 screening data [40] or retrieve compounds from the PubChem BioAssay database [42].

- Curate the dataset by assigning a binary label (

1for active,0for inactive) based on experimental IC₅₀ or GI₅₀ values. A common threshold is IC₅₀ < 10 µM for "active" [42] [40]. - Preprocess the chemical structures: standardize tautomers, remove duplicates, and neutralize charges. Filter out highly similar molecules using the Tanimoto coefficient on molecular fingerprints (e.g., a threshold of >0.85) to ensure chemical diversity and prevent model bias [42].

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- Calculate a comprehensive set of numerical descriptors for each molecule to represent its chemical structure.

- Use open-source tools like:

- The combined descriptor set often requires cleaning by removing descriptors with missing values, zero variance, or constant values.

Step 3: Feature Selection

- Apply a multi-step feature selection process to reduce dimensionality and enhance model performance.

- Variance Filtering: Remove descriptors with very low variance (e.g., using a threshold of <0.05) [42].

- Correlation Filtering: Eliminate highly correlated descriptors (e.g., Pearson correlation > 0.85) to reduce redundancy [42].

- Advanced Feature Selection: Use algorithms like Boruta [42] or Recursive Feature Elimination to identify the most statistically significant features for predicting activity.

Step 4: Dataset Splitting

- Split the curated dataset into:

- Perform this split in a stratified manner to preserve the ratio of active to inactive compounds in each set.

Step 5: Model Training and Validation

- Train the RF, SVM, and k-NN models on the training set using selected features.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize key parameters using techniques like Grid Search or Bayesian Optimization with 5-fold or 10-fold cross-validation on the training set [37].

- Random Forest:

n_estimators,max_depth. - SVM:

C(regularization),gamma(kernel coefficient). - k-NN:

k(number of neighbors).

- Random Forest:

Step 6: Model Evaluation and Interpretation

- Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set using metrics such as Accuracy, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), Sensitivity, Specificity, and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC) [42] [40] [43].

- Interpret the model to gain chemical insights.

- For Random Forest, use SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to quantify the contribution of each descriptor to the prediction, highlighting key physicochemical properties for anticancer activity [38] [42].

- Analyze the most important molecular descriptors and fingerprints to inform the rational design of new compounds.

Protocol 2: Virtual Screening Workflow for Novel Anticancer Agents

Objective: To use a validated QSAR model to screen a large chemical database and identify potential novel anticancer hits.

Experimental Workflow:

Step 1: Database Preparation

- Obtain a large database of purchasable or synthesizable compounds, such as ZINC or e-Drug3D [41].

- Preprocess the database as in Protocol 1, Step 1 (standardization, deduplication).

Step 2: Predictive Screening

- Calculate the same set of selected molecular descriptors from Protocol 1 for all compounds in the database.

- Use the pre-trained and validated RF, SVM, or k-NN model to predict the probability of anticancer activity for each compound.

Step 3: Hit Identification and Validation

- Rank the compounds based on their predicted activity scores or probabilities.

- Select the top-ranked compounds (virtual hits) for experimental validation.

- Validate hits using in vitro assays, such as the MTT assay against relevant cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7, HepG2) [38] [44] to confirm cytotoxic activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table lists essential reagents, software, and databases for conducting ML-driven QSAR studies in anticancer research.

| Category | Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Programming Tools | PaDEL-Descriptor / PaDELPy [37] [42] [40] | Calculates 1D, 2D molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures. |

| RDKit [37] [42] | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for descriptor calculation, molecular manipulation, and similarity search. | |

| scikit-learn [42] | A core Python library for implementing ML algorithms (RF, SVM, k-NN) and data preprocessing steps. | |

| CORAL Software [43] | Builds QSAR models based on SMILES notation and the Monte Carlo method. | |

| Bioactivity Data Sources | PubChem BioAssay [42] | Public repository of chemical molecules and their biological activities, used for dataset construction. |

| NCI-60 Database [40] | Contains screening results of thousands of compounds against 60 human cancer cell lines. | |

| ChEMBL [41] | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | |

| Experimental Validation Reagents | MTT / XTT Assay Kits [44] | Standard colorimetric assays for measuring cell viability and proliferation to confirm cytotoxic activity of predicted hits. |

| Cancer Cell Lines (e.g., MCF-7, HepG2, A549, HeLa) [38] [44] [45] | Human cancer cells used for in vitro testing of compound cytotoxicity. | |

| Normal Cell Lines (e.g., Vero, MRC-5) [38] [44] | Non-cancerous cells used to assess the selectivity index (SI) of potential anticancer agents. |

This application note details the implementation of Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) for predicting anticancer activity, positioning this advanced machine learning technique within the established framework of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling. Conventional QSAR models often struggle with the high-dimensionality and non-linear relationships present in complex anticancer drug data. DNNs address these limitations by automatically learning hierarchical feature representations from raw molecular descriptors, leading to enhanced predictive accuracy for identifying novel anticancer agents [46]. This document provides a comparative analysis of model performance, a detailed experimental protocol for DNN-QSAR model development, and essential resources for researchers.

Comparative Performance of Modeling Techniques

A comparative study evaluated the performance of DNNs against other machine learning and traditional QSAR methods for predicting inhibitory activity against the MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cell line. The models were trained and tested on a dataset of 7,130 molecules, using extended connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs) and functional-class fingerprints (FCFPs) as molecular descriptors [46]. The predictive accuracy was measured using the R-squared (R²) value on a fixed test set of 1,061 compounds.

Table 1: Performance Comparison (R²) of Predictive Models on a Triple-Neg breast Cancer Dataset

| Modeling Technique | Training Set (n=6,069) | Training Set (n=3,035) | Training Set (n=303) | Model Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | ~0.90 | ~0.94 | ~0.84 | Machine Learning |

| Random Forest (RF) | ~0.90 | ~0.90 | ~0.84 | Machine Learning |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | ~0.65 | ~0.24 | ~0.24 | Traditional QSAR |

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | ~0.65 | ~0.24 | ~0.24 | Traditional QSAR |

Note: Data adapted from a comparative study on virtual screening methods [46].

The data demonstrates the superior performance of machine learning methods, particularly DNNs, over traditional QSAR approaches. DNNs maintain high predictive accuracy even with a substantial reduction in training set size, showcasing their robustness and efficiency in feature learning [46].

Experimental Protocol: DNN-driven QSAR for Anticancer Activity Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps for developing a DNN-based QSAR model to predict the anticancer activity of flavone derivatives, based on a published 2025 study [38].

Stage 1: Compound Library Design and Biological Assay

- Rational Library Design: Design a library of flavone analogs (e.g., 89 compounds) with diverse substitution patterns using pharmacophore modeling against specific cancer targets (e.g., breast cancer MCF-7 and liver cancer HepG2 cell lines) [38].

- Synthesis and Characterization: Synthesize the designed flavone analogs and characterize their chemical structures using analytical techniques (NMR, LC-MS).

- Biological Evaluation:

- Cytotoxicity Assay: Determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) of each compound against the target cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7, HepG2) via a standard MTT assay.

- Selectivity Assessment: Evaluate cytotoxicity against a normal cell line (e.g., Vero cells) to assess selective toxicity.

Stage 2: Data Preparation and Molecular Featurization

- Data Curation: Compile a dataset where each entry consists of a flavone's chemical structure and its corresponding bioactivity (e.g., IC₅₀ value converted to pIC₅₀).

- Compute Molecular Descriptors: Generate a set of molecular descriptors for each compound. This can include:

- Dataset Splitting: Randomly split the curated dataset into a training set (e.g., 80%) for model development and a hold-out test set (e.g., 20%) for final model evaluation.

Stage 3: DNN Model Development and Training

- Model Architecture Definition: Construct a DNN architecture using a deep learning library (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch).

- Input Layer: Number of nodes equals the number of molecular descriptors.

- Hidden Layers: Implement multiple fully connected layers (e.g., 3-5 layers) with non-linear activation functions (e.g., ReLU). The number of neurons per layer can be optimized (e.g., 512, 256, 128).

- Output Layer: A single node for continuous pIC₅₀ value prediction.

- Model Training:

- Loss Function: Use Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the loss function.

- Optimizer: Employ the Adam optimizer.

- Validation: Use a portion of the training set (e.g., 10-20%) as a validation set to monitor for overfitting during training.