AI-Driven Feature Extraction in Genomic Data for Precision Cancer Classification

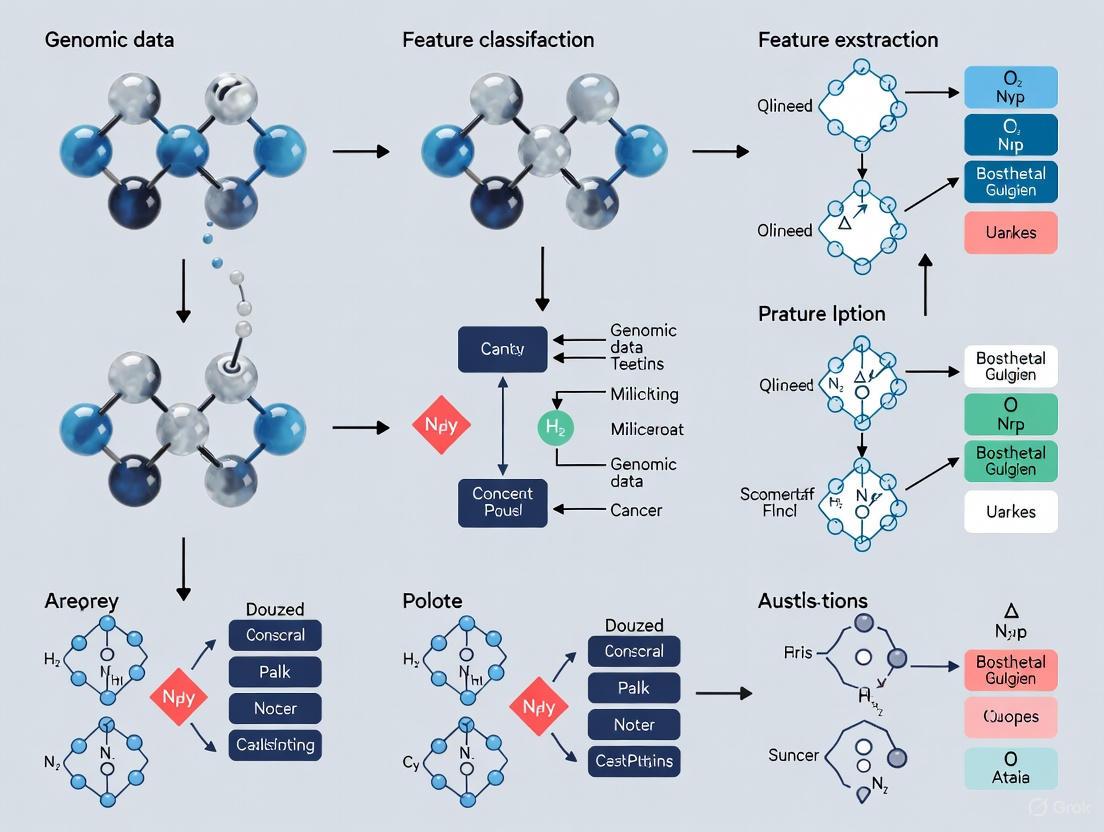

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced computational strategies for extracting meaningful features from high-dimensional genomic data to improve cancer classification.

AI-Driven Feature Extraction in Genomic Data for Precision Cancer Classification

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced computational strategies for extracting meaningful features from high-dimensional genomic data to improve cancer classification. It explores the foundational role of multi-omics data, details cutting-edge methodologies from nature-inspired optimization to deep learning, and addresses critical challenges like data dimensionality and model interpretability. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content also covers validation frameworks and performance benchmarks, synthesizing key trends to guide the future integration of these tools into clinical and precision medicine pipelines.

The Building Blocks: Understanding Genomic Data and the Imperative for Feature Extraction in Oncology

The Critical Role of Early and Precise Cancer Classification

Cancer remains a major global health challenge, characterized by the uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells that can lead to tumors, immune system deterioration, and high mortality rates [1]. According to the World Health Organization, cancer is among the deadliest disorders worldwide, with colorectal, lung, breast, and prostate cancers representing the most prevalent forms [1]. The critical importance of early and precise cancer classification cannot be overstated—it fundamentally shapes diagnostic accuracy, prognostic assessment, therapeutic decisions, and ultimately patient survival outcomes. Within modern oncology, this precision is increasingly framed within the context of genomic data feature extraction, which enables researchers to decode the complex molecular signatures that underlie carcinogenesis.

Traditional cancer classification, primarily based on histopathological examination of tumor morphology and anatomical origin, provides valuable but limited information for predicting disease behavior and treatment response. The integration of molecular profiling technologies has revealed tremendous heterogeneity within cancer types previously classified as uniform entities, driving the need for more sophisticated classification systems [2]. Early and precise classification using genomic data allows clinicians to identify distinctive gene patterns that are characteristic of various cancer types, enabling more personalized treatment approaches and improving overall recovery rates [3]. This whitepaper examines the technological frameworks, computational methodologies, and clinical applications that make precise cancer classification achievable, with particular emphasis on feature extraction from complex genomic datasets for research and therapeutic development.

The Impact of Classification Precision on Cancer Epidemiology and Clinical Decision-Making

Precise cancer classification directly influences public health understanding and clinical decision-making. Changes in classification standards can create artifactual patterns in incidence rates that must be carefully interpreted by researchers and public health officials. A recent cohort study of 63,780 patients with colorectal cancer demonstrated how changes in the definition of neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) significantly affected the estimated incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC) in individuals aged 15-39 years, for whom NENs constituted 29.7% of cases compared to just 5.7% in the 40-49 age group and 1.4% in patients aged 50 or older [4]. This highlights how classification precision impacts our understanding of evolving cancer trends, particularly important given current debates about initiating colorectal cancer screening at earlier ages.

From a clinical perspective, precise classification enables more accurate prognostication and therapy selection. Molecular subtypes within the same histopathological cancer classification often demonstrate dramatically different biological behaviors and treatment responses. For instance, in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), increased expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) occurs in 90% of cases and is associated with poor survival, making it a critical classification marker for determining eligibility for targeted therapies like cetuximab [5]. The development of resistance to such targeted therapies further underscores the need for sophisticated classification systems that can distinguish between pre-existing, randomly acquired, and drug-induced resistance mechanisms, each requiring different therapeutic approaches [5].

Table 1: Impact of Classification Changes on Colorectal Cancer Incidence Patterns [4]

| Age Group | NEN Proportion | Incidence Pattern | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15-39 years | 29.7% (278 of 935) | Significant increase | Artifactual increase due to classification changes |

| 40-49 years | 5.7% (132 of 2333) | Remained stable | Minimal impact from classification changes |

| ≥50 years | 1.4% (856 of 60,512) | Stable/Decreasing | Negligible effect from NEN reclassification |

Genomic Technologies Enabling Precise Cancer Classification

High-Throughput Technologies for Genomic Profiling

Advances in genomic technologies have revolutionized cancer classification by providing comprehensive molecular profiles of tumors. DNA microarrays and next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods, particularly RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq), represent the primary technologies enabling high-throughput genomic analysis [3]. DNA microarrays employ two-dimensional arrays with microscopic spots to which short DNA sequences or genes bind to known DNA molecules through a hybridization process, allowing simultaneous measurement of expression levels for thousands of genes [3]. RNA-sequencing offers several advantages over microarray technology, including greater specificity and resolution, increased sensitivity to differential expression, and a greater dynamic range [3]. RNA-Seq involves converting RNA molecules into complementary DNA (cDNA) and determining the nucleotide sequence of the cDNA for gene expression analysis and quantification, enabling examination of the transcriptome to determine the amount of RNA at a specific timepoint [3].

Multi-Omics Integration for Comprehensive Profiling

The most significant advances in cancer classification now come from integrating multiple data modalities, known as multi-omics approaches. Machine learning and deep learning methods have proven particularly effective at integrating diverse and high-volume data types, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, imaging data, and clinical records [2]. This integrative approach provides comprehensive molecular profiles that facilitate the identification of highly predictive biomarkers across various cancer types, including breast, lung, and colon cancers [2]. The shift from single-analyte approaches to multi-omics integration represents a fundamental transformation in cancer classification, enabling researchers to capture the complex, multifaceted biological networks that underpin disease mechanisms, particularly important for heterogeneous conditions like cancer.

Table 2: Genomic Technologies for Cancer Classification [3]

| Technology | Mechanism | Advantages | Applications in Cancer Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Microarrays | Hybridization of labeled nucleic acids to arrayed DNA probes | High-throughput, cost-effective for large studies | Simultaneous measurement of thousands of gene expressions |

| RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) | High-throughput sequencing of cDNA converted from RNA | Greater specificity, sensitivity, and dynamic range | Transcriptome analysis, detection of novel transcripts, variant calling |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Massively parallel sequencing of DNA fragments | Comprehensive genomic coverage, single-nucleotide resolution | Whole genome sequencing, targeted sequencing, mutation profiling |

Computational Methodologies for Feature Extraction and Classification

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have emerged as powerful tools for analyzing complex genomic data in cancer classification. These computational approaches address significant limitations of traditional biomarker discovery methods, including limited reproducibility, high false-positive rates, and inadequate predictive accuracy caused by biological heterogeneity [2]. ML and DL methodologies can be broadly categorized into supervised and unsupervised approaches. Supervised learning trains predictive models on labeled datasets to accurately classify disease status or predict clinical outcomes, using techniques including support vector machines (SVM), random forests, and gradient boosting algorithms (XGBoost, LightGBM) [2]. Unsupervised learning explores unlabeled datasets to discover inherent structures or novel subgroupings without predefined outcomes, employing methods such as k-means clustering, hierarchical clustering, and principal component analysis [2].

Deep learning architectures have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in analyzing large-scale genomic datasets. Commonly used architectures include convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), graph neural networks (GNNs), and transformer networks (TNNs) [3]. CNNs utilize convolutional layers to identify spatial patterns, making them highly effective for imaging data such as histopathology slides, while RNNs employ a recurrent architecture that maintains an internal memory of previous inputs, allowing them to understand context and dependencies within sequential information [3]. This capability is particularly valuable for biomedical data that changes over time, enabling RNNs to capture temporal dynamics crucial for prognostic and treatment response prediction.

Feature Selection and Optimization Strategies

The high-dimensional nature of genomic data, where the number of features (genes) vastly exceeds the number of samples, presents significant challenges for classification algorithms. Feature selection optimization has thus become one of the most promising approaches for cancer prediction and classification [6]. Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) have shown particular promise for feature selection from high-dimensional gene expression data [6]. These approaches can be categorized into filter, wrapper, and embedded methods [3]. Filter methods remove irrelevant and redundant data features based on quantifying the relationship between each feature and the target predicted variable, offering fast processing and lower computational complexity [3]. Wrapper methods employ a classification algorithm to evaluate feature importance, with the classifier wrapped in a search algorithm to discover the best feature subset [3]. Embedded approaches identify important features that enhance classifier performance by integrating feature selection directly into the learning process [3].

Recent research has produced advanced hybrid models that combine multiple approaches for enhanced performance. The Artificial Intelligence-Based Multimodal Approach for Cancer Genomics Diagnosis Using Optimized Significant Feature Selection Technique (AIMACGD-SFST) model employs the coati optimization algorithm (COA) for feature selection and ensemble models including deep belief network (DBN), temporal convolutional network (TCN), and variational stacked autoencoder (VSAE) for classification, achieving accuracy values of 97.06% to 99.07% across diverse datasets [1]. Similarly, binary variants of the COOT optimizer framework have been developed for gene selection to identify cancer and illnesses, incorporating crossover operators to enhance global search capabilities [1].

Experimental Design and Methodological Protocols

Master Protocol Trials for Targeted Therapeutic Evaluation

The shift toward molecularly-defined cancer subtypes has necessitated evolution in clinical trial design. Master protocol trials have emerged as a next-generation clinical trial approach that evaluates multiple targeted therapies for specific molecular subtypes within a single comprehensive protocol [7]. These trials can be categorized into basket, umbrella, and platform designs [7]. Basket trials evaluate one targeted therapy across multiple diseases or disease subtypes sharing a common molecular marker, enabling efficient enrollment for rare cancer fractions [7]. Umbrella trials evaluate multiple targeted therapies for at least one disease, typically stratified by molecular markers [7]. Platform trials represent the most adaptive design, evaluating several targeted therapies for one disease perpetually, with flexibility to add or exclude new therapies during the trial based on emerging results [7].

Master protocol trials use a common system for patient selection, logistics, templates, and data management, with histologic and hematologic specimens analyzed using standardized systems to collect coherent molecular marker data [7]. This approach increases patient access to trials most suitable for their molecular profile, accelerating clinical development and enabling more efficient evaluation of targeted therapies. The NCI-MATCH trial represents a prominent example, incorporating aspects of both basket and umbrella designs to evaluate multiple targeted therapies across different cancer types based on specific molecular alterations [7].

Model-Informed Experimental Design for Resistance Mechanism Identification

Mathematical modeling approaches have proven valuable for designing experiments to identify resistance mechanisms in targeted cancer therapies. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), researchers have utilized tumor volume data from patient-derived xenografts to develop a family of mathematical models, with each model representing different timing and mechanisms of cetuximab resistance (pre-existing, randomly acquired, or drug-induced) [5]. Through model selection and parameter sensitivity analyses, researchers determined that initial resistance fraction measurements and dose-escalation volumetric data are required to distinguish between different resistance mechanisms [5]. This model-informed approach provides a framework for optimizing experimental design to efficiently identify resistance mechanisms, potentially accelerating the development of strategies to overcome therapeutic resistance.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Cancer Genomics [1] [2] [3]

| Category | Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Laboratory Reagents | DNA Microarrays | Gene expression profiling | Simultaneous measurement of thousands of genes |

| RNA-Sequencing Kits | Transcriptome analysis | High sensitivity, detection of novel variants | |

| Immunohistochemistry Kits | Protein expression analysis | Validation of genomic findings at protein level | |

| Computational Tools | Coati Optimization Algorithm (COA) | Feature selection | Identifies optimal gene subsets from high-dimensional data |

| Deep Belief Networks (DBN) | Classification | Captures complex hierarchical patterns in genomic data | |

| Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN) | Sequential data analysis | Models temporal dependencies in longitudinal genomic data | |

| Variational Stacked Autoencoders (VSAE) | Dimensionality reduction | Learns efficient representations of genomic data |

Validation, Clinical Translation, and Future Directions

Validation Frameworks and Clinical Implementation

Robust validation represents a critical step in translating genomic classification systems from research tools to clinical applications. Biomarkers identified through computational methods must undergo stringent validation using independent cohorts and experimental wet-lab methods to ensure reproducibility and clinical reliability [2]. The dynamic nature of ML-driven biomarker discovery, where models continuously evolve with new data, presents particular challenges for regulatory oversight by bodies such as the US Food and Drug Administration, necessitating adaptive yet strict validation and approval frameworks [2]. Model interpretability remains a significant hurdle for clinical adoption, as many advanced algorithms function as "black boxes," making it difficult to elucidate how specific predictions are derived [2]. Explainable AI approaches are therefore essential for building clinical trust and facilitating integration into diagnostic workflows.

Clinical implementation of precise cancer classification systems requires careful consideration of ethical implications, regulatory standards, and practical workflow integration. As classification systems increasingly incorporate multi-omics data and complex algorithms, ensuring equitable access and avoiding health disparities becomes paramount. Furthermore, the clinical actionability of molecular subtypes must be clearly established, with defined therapeutic implications for each classification category. The continuous evolution of cancer classification systems necessitates ongoing education for clinicians and updates to clinical practice guidelines to ensure that diagnostic advances translate to improved patient outcomes.

Emerging Trends and Future Research Directions

The field of cancer classification is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. Functional biomarker discovery represents a particularly promising area, with researchers increasingly focusing on biomarkers that not only correlate with disease states but also provide insight into biological mechanisms [2]. Biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), which encode enzymatic machinery for producing specialized metabolites with therapeutic potential, exemplify this trend toward functional biomarkers [2]. The integration of microbiome-derived biomarkers represents another frontier, expanding the biomarker landscape beyond the human genome to include microbial signatures that influence cancer development and treatment response [2].

Technologically, the convergence of artificial intelligence with multi-omics data is expected to accelerate, with transformer networks and graph neural networks playing increasingly prominent roles in analyzing complex biological relationships [3]. The development of dynamic-length chromosome techniques for more sophisticated biomarker gene selection represents an important technical direction, addressing current limitations in handling the high dimensionality of genomic data [6]. As single-cell sequencing technologies mature, classification systems will increasingly incorporate cellular heterogeneity within tumors, enabling more precise characterization of tumor ecosystems and their role in therapeutic response and resistance [2].

Early and precise cancer classification, powered by advanced genomic technologies and computational methodologies, represents a cornerstone of modern oncology research and clinical practice. The integration of multi-omics data, machine learning algorithms, and sophisticated feature selection techniques has transformed our understanding of cancer biology, enabling molecular stratification that predicts disease behavior and treatment response with unprecedented accuracy. As classification systems continue to evolve, incorporating functional biomarkers, single-cell resolution, and microenvironmental factors, they will increasingly guide therapeutic development and clinical decision-making. The ongoing challenge for researchers and clinicians lies in validating these classification systems, ensuring their clinical utility, and translating complex molecular information into actionable strategies that ultimately improve outcomes for cancer patients across the diagnostic and therapeutic spectrum.

In the field of cancer genomics, researchers and drug development professionals face a fundamental computational obstacle: the high-dimensional nature of gene expression data. This "curse of dimensionality" arises from the vast discrepancy between the number of measured features (tens of thousands of genes) and typically available samples (often hundreds), creating significant challenges for pattern recognition, biomarker discovery, and classification model development [1] [8]. The complexity of this data landscape is characterized by high gene-gene correlations, significant noise, and the presence of numerous irrelevant genes that can obscure biologically meaningful signals crucial for accurate cancer classification [8]. This technical guide examines the core challenges inherent in high-dimensional genomic data and provides detailed methodologies for extracting robust features that drive reliable cancer classification in research settings.

The implications of improperly handled high-dimensional data are substantial, ranging from overfitted models that fail to generalize to new datasets to missed therapeutic targets and inaccurate diagnostic signatures. As cancer remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with nearly 10 million deaths reported in 2022, the development of efficient and accurate computational approaches for gene expression analysis has become increasingly critical [8]. This guide presents a comprehensive framework for navigating these challenges through optimized preprocessing, feature selection, and modeling techniques specifically tailored to genomic data within cancer research contexts.

Normalization Methods: Foundation for Reliable Analysis

Normalization constitutes the critical first step in processing raw gene expression data, addressing technical variations arising from sequencing depth, gene length, and other experimental factors that would otherwise confound biological signal interpretation [9] [10]. The choice of normalization method significantly impacts downstream analysis, including feature selection effectiveness and classification accuracy.

Methodological Comparison and Performance Benchmarking

Research benchmarking five predominant RNA-seq normalization methods—TPM, FPKM, TMM, GeTMM, and RLE—reveals distinct performance characteristics when these methods are applied to create condition-specific metabolic models using iMAT and INIT algorithms [9]. The findings demonstrate that between-sample normalization methods (TMM, RLE, GeTMM) produce metabolic models with considerably lower variability in active reactions compared to within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM), reducing false positive predictions at the expense of missing some true positive genes when mapped on genome-scale metabolic networks [9].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Normalization Methods

| Normalization Method | Category | Key Characteristics | Impact on Model Variability | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMM | Between-sample | Hypothesizes most genes not differentially expressed; sums rescaled gene counts | Low variability | General purpose; large sample sizes |

| RLE | Between-sample | Uses median ratio of gene counts; applies correction factor to read counts | Low variability | General purpose; differential expression |

| GeTMM | Between-sample hybrid | Combines gene-length correction with TMM normalization | Low variability | Studies requiring length normalization |

| TPM | Within-sample | Normalizes for gene length then sequencing depth | High variability | Single-sample comparisons |

| FPKM | Within-sample | Normalizes for sequencing depth then gene length | High variability | Single-sample comparisons |

For cross-platform analysis integrating microarray and RNA-seq data, approaches utilizing non-differentially expressed genes (NDEG) for normalization have demonstrated improved classification performance. Studies classifying breast cancer molecular subtypes achieved optimal cross-platform performance using LOGQN and LOGQNZ normalization methods combined with neural network classifiers when trained on one platform and tested on another [11].

Covariate Adjustment Considerations

The presence of dataset covariates such as age, gender, and post-mortem interval (for brain tissues) introduces additional complexity requiring specialized normalization approaches. Research indicates that covariate adjustment applied to normalized data increases accuracy in capturing disease-associated genes—for Alzheimer's disease, accuracy increased to approximately 0.80, and for lung adenocarcinoma, to approximately 0.67 across normalization methods [9]. This demonstrates the critical importance of accounting for technical and biological covariates during normalization to enhance model precision in cancer classification research.

Feature Selection Strategies for Dimensionality Reduction

Feature selection methods address high-dimensionality by identifying the most informative genes while eliminating redundant or noisy features, thereby improving model performance, reducing overfitting, and enhancing biological interpretability.

Algorithmic Approaches and Comparative Performance

Multiple feature selection strategies have been developed and benchmarked for cancer genomics applications:

Optimization Algorithm-Based Methods: The coati optimization algorithm (COA) has been employed in the AIMACGD-SFST model for selecting relevant features from gene expression datasets, contributing to reported classification accuracies of 97.06% to 99.07% across diverse cancer datasets [1]. Similarly, the novel HybridGWOSPEA2ABC algorithm, integrating Grey Wolf Optimizer, Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm 2, and Artificial Bee Colony, has demonstrated superior performance in identifying relevant cancer biomarkers compared to conventional bio-inspired algorithms [12].

Statistical and Hybrid Approaches: Weighted Fisher Score (WFISH) utilizes gene expression differences between classes to assign weights to features, prioritizing informative genes and reducing the impact of less useful ones. When combined with random forest and k-nearest neighbors classifiers, WFISH consistently achieved lower classification errors across five benchmark datasets [13]. LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) serves as both a regularization technique and feature selection tool by driving regression coefficients of irrelevant features to exactly zero, making it particularly valuable for high-dimensional data where only a subset of features is informative [8].

Table 2: Feature Selection Algorithm Performance in Cancer Classification

| Feature Selection Method | Underlying Approach | Key Advantages | Reported Classification Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coati Optimization Algorithm (COA) | Bio-inspired optimization | Effective dimensionality reduction while preserving critical data | 97.06% - 99.07% across datasets [1] |

| HybridGWOSPEA2ABC | Hybrid meta-heuristic | Enhanced solution diversity, convergence efficiency | Superior to conventional bio-inspired algorithms [12] |

| Weighted Fisher Score (WFISH) | Statistical weighting | Prioritizes biologically significant genes | Lower classification errors with RF/kNN [13] |

| LASSO Regression | Regularized linear model | Built-in feature selection via coefficient shrinkage | Effective for high-dimensional genomic data [8] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Model-based selection | Handles high-dimensional data effectively | 99.87% under 5-fold cross-validation [8] |

Ensemble and Multi-Method Integration

Integrating multiple feature selection approaches has emerged as a powerful strategy for leveraging their complementary strengths. The Deep Ensemble Gene Selection and Attention-Guided Classification (DEGS-AGC) framework combines ensemble learning with deep neural networks, XGBoost, and random forest, using an attention mechanism to adaptively allocate weights to genes to improve comprehensibility and classification accuracy [1]. Similarly, multi-strategy fusion approaches have demonstrated enhanced capability to address the challenges of high-dimensional data and advance gene selection for cancer classification [1].

Experimental Frameworks and Workflows

Integrated Multi-Modal Classification Pipeline

The Artificial Intelligence-Based Multimodal Approach for Cancer Genomics Diagnosis Using Optimized Significant Feature Selection Technique (AIMACGD-SFST) represents a comprehensive experimental framework that integrates multiple processing stages [1]:

- Preprocessing Stage: Min-max normalization, handling missing values, encoding target labels, and dataset splitting into training and testing sets

- Feature Selection: Application of coati optimization algorithm (COA) to select relevant features from the dataset

- Classification: Ensemble modeling using deep belief network (DBN), temporal convolutional network (TCN), and variational stacked autoencoder (VSAE)

This integrated approach has demonstrated superior performance with accuracy values of 97.06%, 99.07%, and 98.55% across diverse datasets, outperforming existing models [1].

Cross-Platform Transcriptomic Analysis Workflow

For studies integrating multiple gene expression measurement platforms, a specialized workflow has been developed:

- Data Cleaning: Screen samples across both platforms, retaining only samples with corresponding subtype classification labels and genes present in both datasets

- Gene Selection: Perform one-way ANOVA to identify non-differentially expressed genes (NDEGs) for normalization and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for classification

- Normalization: Apply platform-appropriate normalization methods (LOGQN and LOGQNZ recommended for cross-platform applications)

- Model Training and Validation: Implement classification models with rigorous cross-platform validation—training on RNA-seq and testing on microarray data (Model-S) or vice versa (Model-A) [11]

This workflow addresses the critical challenge of cross-platform compatibility, enabling researchers to leverage larger combined datasets while maintaining analytical rigor.

Joint Dimension Reduction for Translational Studies

Translating findings from cancer model systems to human contexts presents unique dimensional challenges. The Joint Dimension Reduction (jDR) approach horizontally integrates gene expression data across model systems (e.g., cell lines, mouse models) and human tumor cohorts [14]. Using methods like Angle-based Joint and Individual Variation Explained (AJIVE), this approach:

- Decomposes input data blocks into lower dimensional spaces that minimize redundant variation

- Eliminates spurious sampling noise while isolating cohort-specific variation

- Identifies shared components of variation acting across cohorts

- Enables more accurate translation of predictive models and clinical biomarkers from model systems to humans [14]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Gene Expression Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in Research | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Datasets | TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) | Provides comprehensive human tumor molecular characterization | Primary data source for cancer classification models [8] [15] |

| Cell Line Resources | CCLE (Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia) | Offers multi-omics profiling across human cancer cell lines | Model system for translational studies [14] |

| Dependency Maps | DepMap (Cancer Dependency Map) | Identifies cancer-specific genetic dependencies across cell lines | Functional gene network analysis [16] |

| Normalization Tools | edgeR (TMM), DESeq2 (RLE) | Implements between-sample normalization methods | Standardized RNA-seq data processing [9] |

| Feature Selection Algorithms | COATI, HybridGWOSPEA2ABC, WFISH | Identifies optimal gene subsets from high-dimensional data | Dimensionality reduction for classification [1] [12] [13] |

| ML Classifiers | SVM, Random Forest, Neural Networks | Builds predictive models from selected features | Cancer type classification [8] [15] |

| Validation Frameworks | FLEX, k-fold Cross-Validation | Benchmarks algorithm performance | Method evaluation and selection [16] |

Navigating the high-dimensional landscape of gene expression data requires a methodical, integrated approach combining appropriate normalization, strategic feature selection, and robust validation frameworks. The methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide researchers and drug development professionals with proven strategies for extracting meaningful biological signals from complex genomic data, ultimately enhancing the accuracy and reliability of cancer classification models. As the field advances, the continued refinement of these approaches—particularly through ensemble methods and cross-platform integration—will be essential for translating genomic discoveries into clinically actionable insights for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

The advent of large-scale molecular profiling has fundamentally transformed oncology research, shifting the paradigm from single-analyte investigations to integrative multi-omics analyses. Cancer, a complex and heterogeneous disease, manifests through coordinated dysregulations across genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic layers [17]. A comprehensive understanding of tumorigenesis, cancer progression, and treatment response requires simultaneous interrogation of these interconnected molecular dimensions [18]. The five core components—mRNA, miRNA, lncRNA, copy number variation (CNV), and DNA methylation—form a critical regulatory axis that drives cancer pathogenesis and heterogeneity [19] [17].

Integrative analysis of these elements provides unprecedented opportunities for refining cancer classification, identifying novel biomarkers, and developing targeted therapies [17]. mRNA represents the protein-coding transcriptome, reflecting functional gene activity states. miRNA and lncRNA constitute key regulatory RNA networks that fine-tune gene expression. CNV captures genomic structural variations that alter gene dosage, while DNA methylation provides an epigenetic layer that modulates transcriptional accessibility without changing the underlying DNA sequence [17]. Together, these molecular features form a multi-layered regulatory circuit that governs cellular homeostasis and, when disrupted, drives oncogenic transformation [20].

The clinical translation of multi-omics insights holds particular promise for precision oncology. Molecular subtyping of cancers based on multi-omics signatures has demonstrated superior prognostic and predictive value compared to traditional histopathological classifications [21]. For instance, tumors originating from different organs may share molecular features that predict similar therapeutic responses, while histologically similar tumors from the same tissue may exhibit distinct molecular profiles requiring different treatment approaches [19]. This refined classification framework enables more accurate diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy selection, ultimately improving patient outcomes [21].

Core Multi-Omics Components: Technical Specifications and Biological Functions

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics, technological platforms, and cancer biology relevance of the five core omics components in the current multi-omics landscape.

Table 1: Technical Specifications and Biological Functions of Core Multi-Omics Components

| Omics Component | Biological Function | Primary Technologies | Key Cancer Roles | Data Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA Expression | Protein-coding transcripts; translates genetic information into functional proteins [19]. | Microarrays, RNA-Seq [19]. | Dysregulation drives uncontrolled proliferation; identifies oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes [19]. | High-dimensional; continuous expression values; requires normalization. |

| miRNA Expression | Short non-coding RNAs (~22 nt) that regulate gene expression by targeting mRNAs for degradation or translational repression [19]. | miRNA-Seq, Microarrays. | Acts as oncogenes (oncomiRs) or tumor suppressors; modulates drug response [19]. | Small feature number relative to mRNA; stable in tissues and biofluids. |

| lncRNA Expression | Long non-coding RNAs (>200 nt) that regulate gene expression, development, and differentiation via diverse mechanisms [19]. | RNA-Seq. | Influences proliferation, metastasis, and apoptosis; serves as diagnostic/prognostic biomarker [20] [19]. | Tissue-specific expression; complex secondary structures. |

| Copy Number Variation (CNV) | Duplications or deletions of DNA segments, altering gene dosage and potentially driving oncogene activation or tumor suppressor loss [17]. | SNP Arrays, NGS, aCGH. | Amplification of oncogenes (e.g., HER2 in breast cancer); deletion of tumor suppressors [17]. | Discrete integer values (copy number states); segmented genomic regions. |

| DNA Methylation | Heritable epigenetic modification involving addition of methyl group to cytosine, typically in CpG islands, affecting gene expression without changing DNA sequence [20] [17]. | Bisulfite Sequencing, Methylation Arrays. | Transcriptional silencing of tumor suppressor genes; global hypomethylation; promoter hypermethylation [20]. | Continuous values (beta-values: 0-1); tissue-specific patterns. |

Experimental Methodologies and Analytical Workflows

Data Generation and Preprocessing Protocols

Multi-omics data generation requires sophisticated technological platforms and standardized processing pipelines to ensure data quality and interoperability. For transcriptomic analyses including mRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA, RNA-Seq has emerged as the predominant technology due to its high sensitivity, accuracy, and ability to detect novel transcripts compared to microarray platforms [19]. The standard workflow begins with RNA extraction, followed by library preparation with protocols specific to RNA species (e.g., size selection for small RNAs in miRNA-Seq), sequencing, and alignment to reference genomes. For methylation analysis, bisulfite conversion-based methods remain the gold standard, where unmethylated cytosines are converted to uracils while methylated cytosines remain protected, allowing for single-base resolution methylation quantification [20]. CNV profiling utilizes either array-based technologies such as SNP arrays or sequencing-based approaches that analyze read depth variations across the genome [17].

Data preprocessing represents a critical step that significantly impacts downstream analyses. For RNA-Seq data, this typically includes quality control (FastQC), adapter trimming, alignment (STAR, HISAT2), quantification (featureCounts, HTSeq), and normalization (TPM, FPKM) [19]. Methylation data preprocessing involves quality assessment, background correction, normalization, and probe filtering to remove cross-reactive and single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-affected probes [20]. CNV data requires segmentation algorithms (CBS, GISTIC) to identify genomic regions with consistent copy number alterations [17]. The integration of multi-omics datasets necessitates careful batch effect correction and data harmonization, particularly when combining data from different technological platforms or experimental batches [18].

Integrative Analysis and Network Construction

Advanced computational frameworks enable the integration of multi-omics data to reconstruct regulatory networks and identify master regulators of cancer phenotypes. One powerful approach involves constructing competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks that model the complex cross-talk between different RNA species [20]. The following diagram illustrates the workflow for constructing a dysregulated lncRNA-associated ceRNA network, which identifies epigenetically driven interactions in cancer:

CeRNA Network Construction Workflow

The ceRNA network construction begins with compiling experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions from databases such as miRTarBase, miRecords, starBase, and lncRNASNP2 [20]. For each candidate lncRNA-mRNA pair, a hypergeometric test identifies statistically significant sharing of miRNAs, with Bonferroni-corrected p-values < 0.01 indicating significant co-regulation [20]. The methodology then applies a modified mutual information approach to quantify the competitive intensity between lncRNAs and mRNAs in both cancer and normal samples, calculating ΔI values that represent the dependency change between miRNAs and their targets in the presence of competing RNAs [20]. Dysregulated interactions are identified as those specific to cancer conditions (gain/loss interactions) or showing significant difference in competitive intensity (ΔΔI) between cancer and normal states, with thresholds set at the 75th and 25th percentiles of all ΔΔI values [20]. Finally, methylation profiles are integrated to identify epigenetically related lncRNAs, defined as those with significant negative correlation between promoter methylation and expression levels [20].

Molecular Subtyping and Classification Frameworks

Cancer classification using multi-omics data employs both unsupervised clustering for subtype discovery and supervised learning for sample classification. Unsupervised approaches include multi-view clustering algorithms that simultaneously integrate data from multiple omics layers to identify molecular subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes and therapeutic vulnerabilities [18]. Supervised classification frameworks leverage machine learning and deep learning models trained on multi-omics features to assign tumor samples to known molecular subtypes [19] [22]. The following workflow illustrates a comprehensive multi-omics classification pipeline for cancer subtype identification:

Multi-Omics Classification Pipeline

The National Cancer Institute has developed a comprehensive resource containing 737 ready-to-use classification models trained on TCGA data across six data types (gene expression, DNA methylation, miRNA, CNV, mutation calls, and multi-omics) [21]. These models employ five different machine learning algorithms and can classify samples into 106 molecular subtypes across 26 cancer types [21]. For novel model development, advanced deep learning frameworks such as GraphVar have demonstrated remarkable performance by integrating complementary data representations, achieving 99.82% accuracy in classifying 33 cancer types through a multi-representation approach that combines mutation-derived imaging features with numeric genomic profiles [22]. These frameworks typically employ ensemble methods or multimodal architectures that process different omics data types through separate branches before integrating them for final classification [1] [22].

Successful multi-omics research requires both wet-lab reagents for data generation and computational resources for data analysis. The following table catalogues essential tools and resources for comprehensive multi-omics investigations in cancer biology.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Multi-Omics Cancer Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biobanking & Sample Prep | PAXgene Tissue System | Stabilizes RNA, DNA, and proteins in tissue samples for multi-omics analysis. | Preserves biomolecular integrity for sequential extraction. |

| TriZol/ TRI Reagent | Simultaneous extraction of RNA, DNA, and proteins from single sample. | Maintains molecular relationships across omics layers. | |

| Sequencing & Array Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq Series | High-throughput sequencing for genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics. | Scalable capacity for large multi-omics cohorts. |

| Affymetrix GeneChip | Microarray-based profiling of gene expression and genetic variation. | Cost-effective for targeted omics profiling. | |

| Illumina EPIC Array | Genome-wide methylation profiling at >850,000 CpG sites. | Comprehensive coverage of regulatory regions. | |

| Data Resources | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Curated multi-omics data for 33 cancer types [19] [21]. | Includes molecular and clinical data integration. |

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | Public repository for functional genomics data [19]. | Diverse dataset collection from independent studies. | |

| UCSC Genome Browser | Visualization and analysis of multi-omics data in genomic context [19]. | User-friendly interface for data exploration. | |

| Analysis Tools & Classifiers | NCICCR Molecular Subtyping Resource | 737 pre-trained models for cancer subtype classification [21]. | Implements multiple algorithms and data types. |

| GraphVar Framework | Multi-representation deep learning for cancer classification [22]. | Integrates image-based and numeric variant features. |

The integrative analysis of mRNA, miRNA, lncRNA, CNV, and methylation data represents a transformative approach in cancer research, enabling a systems-level understanding of tumor biology that transcends single-dimensional analyses. The workflows and methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide a framework for leveraging these complementary data types to refine cancer classification, identify novel therapeutic targets, and ultimately advance precision oncology. While significant challenges remain in standardizing analytical pipelines, managing data complexity, and translating computational findings into clinical practice, ongoing developments in multi-omics technologies and artificial intelligence promise to accelerate this transition [18].

Future directions in multi-omics cancer research will likely focus on dynamic rather than static profiling, incorporating temporal dimensions through longitudinal sampling to capture tumor evolution and therapy resistance mechanisms [19]. The integration of additional omics layers, particularly proteomics and metabolomics, will provide more direct functional readouts of cellular states [17]. Furthermore, the development of more sophisticated computational frameworks that can model causal relationships rather than mere associations will be crucial for distinguishing driver alterations from passenger events in oncogenesis [18]. As these technologies and analytical approaches mature, multi-omics profiling is poised to become an integral component of routine cancer diagnosis, treatment selection, and clinical trial design, finally bridging the gap between large-scale molecular data generation and actionable clinical insights [21].

The advancement of cancer classification research is increasingly dependent on the integration and analysis of large-scale, multi-dimensional genomic data. Key public data resources provide the foundational datasets necessary for developing and validating machine learning models that can decipher the complex molecular signatures of cancer. These resources offer comprehensive genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic profiles from thousands of patient samples, enabling researchers to identify disease biomarkers, characterize molecular subtypes, and develop personalized treatment strategies. Within the context of genomic feature extraction for cancer classification, these databases serve as critical infrastructure for training and testing classification algorithms that can distinguish between cancer types, subtypes, and molecular profiles with increasing accuracy.

The volume and complexity of cancer genomic data have grown exponentially, creating both opportunities and challenges for feature extraction methodologies. Where early approaches relied on single-omics data (e.g., gene expression alone), contemporary cancer classification research increasingly requires multi-omics integration to capture the full complexity of tumor biology. This whitepaper provides a technical analysis of four key public data resources—TCGA, GEO, MLOmics, and cBioPortal—focusing on their applications for feature extraction in cancer classification research, with specific consideration of data structures, preprocessing requirements, and implementation workflows for machine learning pipelines.

The landscape of genomic data resources varies significantly in scope, data types, and readiness for machine learning applications. The following table provides a systematic comparison of the four key resources based on their technical specifications and applicability to cancer classification research.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Key Genomic Data Resources for Cancer Research

| Resource | Primary Focus | Data Types | Sample Volume | Preprocessing Level | Direct ML Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA | Comprehensive cancer genomics | Genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, clinical | ~11,000 patients across 33 cancer types | Raw and processed data | Low (requires significant processing) |

| GEO | General functional genomics | Gene expression, epigenomics, SNP arrays | Millions of samples across diverse conditions | Varies by submission | Low (heterogeneous standards) |

| MLOmics | Machine learning for cancer | mRNA, miRNA, DNA methylation, CNV | 8,314 patients across 32 cancer types [23] | Standardized processing | High (multiple feature versions) |

| cBioPortal | Visual exploration of cancer genomics | Genomic, clinical, protein expression | >5,000 tumor samples from 25+ studies | Processed and normalized | Medium (API access for analysis) |

Technical Specifications and Access Methods

Each resource offers distinct technical characteristics that influence their utility for feature extraction pipelines:

TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas): Hosted by the Genomic Data Commons (GDC), TCGA provides comprehensive molecular characterization of primary cancer tissues and matched normal samples. The data is organized by cancer type and requires significant preprocessing to link samples across different omics modalities. For feature extraction, researchers must implement custom pipelines to harmonize genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic features from raw data files distributed across multiple repositories [23].

GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus): As a functional genomics repository, GEO accepts array- and sequence-based data with a focus on gene expression profiles. The database stores curated gene expression DataSets alongside original Series and Platform records [24]. A key challenge for feature extraction from GEO is the heterogeneity of data formats and experimental protocols, requiring substantial normalization before integration into classification models [25].

MLOmics: Specifically designed for machine learning applications, MLOmics provides preprocessed multi-omics data from TCGA with three distinct feature versions: Original (full feature set), Aligned (genes shared across cancer types), and Top (most significant features selected via ANOVA testing) [23]. This resource includes 20 task-ready datasets for classification and clustering tasks, with built-in support for biological knowledge integration through STRING and KEGG databases [26].

cBioPortal: This resource provides a web-based platform for visualizing, analyzing, and downloading cancer genomics datasets. While primarily designed for interactive exploration, cBioPortal offers API access for programmatic data retrieval, enabling integration with custom analysis pipelines. The platform includes processed mutation, CNA, and clinical data from multiple cancer studies, facilitating comparative analyses [27].

Data Processing and Feature Extraction Methodologies

Multi-Omics Data Processing Workflows

Effective feature extraction from genomic resources requires sophisticated preprocessing pipelines to transform raw data into analysis-ready features. The following diagram illustrates a standardized multi-omics processing workflow adapted from MLOmics and TCGA pipelines:

Diagram 1: Multi-omics data processing and feature extraction workflow

Omics-Specific Processing Protocols

Each omics data type requires specialized processing to extract meaningful features for cancer classification:

Transcriptomics (mRNA/miRNA) Processing:

- Data Identification: Trace data using "experimentalstrategy" field (e.g., "mRNA-Seq" or "miRNA-Seq") and verify "datacategory" as "Transcriptome Profiling" [23].

- Platform Determination: Identify experimental platform from metadata (e.g., "Illumina Hi-Seq") [23].

- Expression Quantification: Convert gene-level estimates using edgeR package to generate FPKM values; apply logarithmic transformation [23].

- Quality Filtering: Remove features with zero expression in >10% of samples or undefined values [23].

- Species Filtering: For miRNA data, remove non-human sequences using miRBase annotations [23].

Genomic (CNV) Processing:

- Variant Identification: Examine metadata for CNV calling descriptions and thresholds [23].

- Somatic Filtering: Retain entries marked as "somatic" and filter out germline mutations [23].

- Recurrent Alteration Detection: Use GAIA package to identify recurrent genomic alterations from segmentation data [23].

- Genomic Annotation: Annotate aberrant regions using BiomaRt package [23].

Epigenomic (Methylation) Processing:

- Region Identification: Map methylation regions to genes using promoter definitions (e.g., 500bp upstream/downstream of TSS) [23].

- Data Normalization: Perform median-centering normalization using limma R package to adjust for technical variations [23].

- Promoter Selection: For genes with multiple promoters, select the promoter with lowest methylation in normal tissues [23].

Feature Engineering and Selection Methods

MLOmics implements a standardized feature processing pipeline to generate three distinct feature versions optimized for different machine learning scenarios:

Table 2: Feature Processing Methodologies in MLOmics

| Feature Version | Processing Methodology | Optimal Use Cases | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original | Direct extraction from processed omics files | Method development, comprehensive feature analysis | Full gene set with platform-specific variations |

| Aligned | 1. Resolution of gene naming format mismatches\n2. Intersection of features across cancer types\n3. Z-score normalization | Cross-cancer comparative studies, pan-cancer classification | Shared feature space across all cancer types |

| Top | 1. Multi-class ANOVA (p < 0.05)\n2. Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction\n3. Feature ranking by adjusted p-values\n4. Z-score normalization | High-dimensional classification, biomarker identification | Significantly variable features only |

The Top feature version employs multi-class ANOVA to identify genes with significant variance across cancer types, followed by Benjamini-Hochberg correction to control false discovery rate [23]. This approach reduces feature dimensionality while preserving biologically relevant signals for cancer classification tasks.

Experimental Design and Implementation Frameworks

Machine Learning Task Formulations

Genomic data resources support multiple machine learning task formulations for cancer research:

Pan-Cancer Classification:

- Objective: Assign cancer type labels based on multi-omics profiles

- Dataset Composition: 32 cancer types from TCGA (8,314 samples) [23]

- Evaluation Metrics: Precision, Recall, F1-score [23]

- Baseline Models: XGBoost, SVM, Random Forest, Logistic Regression [23]

Cancer Subtype Classification:

- Objective: Identify molecular subtypes within specific cancers

- Gold-Standard Datasets: GS-COAD, GS-BRCA, GS-GBM, GS-LGG, GS-OV [23]

- Evaluation Metrics: Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) [23]

- Deep Learning Models: Subtype-GAN, DCAP, XOmiVAE, CustOmics, DeepCC [23]

Cancer Subtype Clustering:

- Objective: Discover novel subtypes through unsupervised learning

- Dataset Composition: Nine rare cancer types from MLOmics [23]

- Validation Approach: Survival analysis, clinical correlation

Technical Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete technical workflow from raw data to cancer classification insights:

Diagram 2: Technical implementation workflow for cancer classification

Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Analysis

The following table details essential computational tools and resources for implementing genomic feature extraction pipelines:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Genomic Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application in Feature Extraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| edgeR | Bioinformatics Package | Differential expression analysis | Convert RSEM estimates to FPKM; normalize RNA-seq data [23] |

| limma | Bioinformatics Package | Microarray data analysis | Normalize methylation data; remove technical biases [23] |

| GAIA | Genomic Analysis | Copy number alteration detection | Identify recurrent CNV regions; annotate genomic alterations [23] |

| BiomaRt | Genomic Annotation | Genomic region annotation | Map features to unified gene IDs; resolve naming conventions [23] |

| XGBoost | Machine Learning | Gradient boosting framework | Baseline classification model; feature importance analysis [23] |

| Subtype-GAN | Deep Learning | Generative adversarial network | Cancer subtyping using multi-omics data [23] |

| STRING | Biological Database | Protein-protein interactions | Biological validation of extracted features [23] |

| KEGG | Biological Database | Pathway mapping | Functional annotation of significant features [23] |

The evolving landscape of genomic data resources continues to transform approaches to cancer classification research. TCGA provides comprehensive raw data for novel analysis development, while MLOmics offers machine learning-ready datasets that significantly reduce preprocessing overhead for rapid model prototyping. GEO enables broad exploration of gene expression patterns across diverse conditions, and cBioPortal supports integrative analysis of genomic and clinical variables.

Future directions in genomic feature extraction will likely emphasize increased integration of multi-omics data, with emerging resources providing more sophisticated preprocessing and normalization pipelines. The integration of AI and machine learning directly into data portals represents a promising trend, potentially enabling real-time feature selection and model training within collaborative research platforms. As these resources evolve, they will continue to advance the precision and predictive power of cancer classification systems, ultimately supporting more personalized and effective cancer diagnostics and treatments.

From Data to Diagnosis: Methodologies for Genomic Feature Extraction and Selection

Filter, Wrapper, and Embedded Feature Selection Techniques

In the field of cancer genomics, the analysis of high-dimensional data, such as microarray gene expression data, presents a significant challenge. These datasets typically contain thousands of genes (features) but only a limited number of patient samples, creating a "curse of dimensionality" scenario where irrelevant, redundant, and noisy features can severely impair the performance of machine learning models [28]. Feature selection has emerged as a critical preprocessing step to identify the most informative genes, thereby enhancing the accuracy of cancer classification, improving the interpretability of models, and reducing computational costs [29]. By focusing on a subset of relevant biomarkers, researchers and clinicians can gain deeper insights into tumor heterogeneity and develop more precise diagnostic tools and personalized treatments [29]. The three primary categories of feature selection techniques—filter, wrapper, and embedded methods—each offer distinct mechanisms and advantages for tackling the complexities of genomic data. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these methodologies, their experimental protocols, and their application within cancer genomics research.

Filter Methods

Core Principle and Workflow

Filter methods assess the relevance of features based on intrinsic data characteristics, such as statistical measures or correlation metrics, without involving any machine learning algorithm for the evaluation. They operate independently of the classifier, making them computationally efficient and scalable to high-dimensional datasets like those encountered in genomics [30]. These methods typically assign a score to each feature, which is then used to rank them. A threshold is applied to select the top-ranked features for the final model.

Common Techniques and Algorithms

Several filter methods are commonly employed in gene expression analysis:

- Information Gain (IG): Measures the reduction in entropy when a feature is used to partition the data [28].

- Chi-squared (CHSQR): Evaluates the independence between a feature and the class label using a chi-squared test [28].

- Correlation (CR): Calculates the linear correlation between a feature and the target variable [28].

- Gini Index (GIND): Assesses the impurity of a split and is often used in tree-based models [28].

- Relief (RELIEF): Estimates feature weights according to their ability to distinguish between near instances [28].

- Standard Deviation (SD) and Bimodality Measures: SD selects features with high variability across samples, while bimodality indices (e.g., bimodality index, dip-test) select features with multimodal distributions, which may correspond to different disease subtypes [31].

Experimental Protocol for Microarray Data Analysis

Objective: To identify the most informative genes from a high-dimensional microarray dataset for cancer subtype classification using filter methods.

Materials:

- Dataset: Microarray gene expression data (e.g., from TCGA). The dataset should include known cancer subtypes for evaluation [31].

- Software: Computational environment such as R or Python with necessary libraries (e.g.,

scikit-feature,scikit-learnin Python).

Procedure:

- Preprocessing:

- Perform data normalization (e.g., min-max normalization) to adjust for technical variations [1].

- Handle missing values using imputation or removal.

- Encode target labels if necessary.

- Split the dataset into training and testing sets.

- Feature Scoring:

- Choose one or more filter methods (e.g., IG, CHSQR, Relief).

- Apply the selected method(s) to the training data to compute a relevance score for every gene.

- Feature Ranking and Selection:

- Rank all genes in descending order based on their scores.

- Select the top ( k ) genes (e.g., the top 5%) [28]. The value of ( k ) can be determined empirically or based on domain knowledge.

- Model Training and Validation:

- Train a chosen classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) using only the selected ( k ) features on the training set.

- Evaluate the classification performance (e.g., accuracy, sensitivity, F1-score) on the held-out test set.

Performance and Applications

Filter methods are particularly effective as an initial, fast dimensionality reduction step. For instance, one study used six filter methods to reduce microarray datasets to just the top 5% of genes before further optimization, demonstrating their utility in handling large feature spaces efficiently [28]. However, a key limitation is that they evaluate features independently and may ignore feature dependencies and interactions with the classifier, potentially leading to suboptimal subsets for classification tasks [28] [30].

Wrapper Methods

Core Principle and Workflow

Wrapper methods utilize the performance of a specific machine learning algorithm to evaluate the quality of a feature subset. They "wrap" themselves around a classifier and use its performance metric (e.g., accuracy) as the objective function to guide the search for an optimal feature subset [32]. This approach considers feature dependencies and interactions with the classifier, often yielding superior performance compared to filter methods. However, wrapper methods are computationally intensive, especially with high-dimensional data, as they require repeatedly training and evaluating the model [33].

Common Techniques and Algorithms

Wrapper methods often employ search strategies, including metaheuristic algorithms, to explore the vast space of possible feature subsets.

- Sequential Feature Selection: This includes Sequential Forward Selection (SFS) and Sequential Backward Selection (SBS). For example, a study on breast cancer biomarkers used SBS with an SVM classifier to identify an optimal set of biomarkers [32].

- Metaheuristic Algorithms: These are population-based stochastic optimization algorithms well-suited for complex search spaces.

- Binary Al-Biruni Earth Radius (bABER) Algorithm: A recently proposed algorithm for the intelligent removal of unnecessary data, shown to outperform other binary metaheuristic algorithms [33].

- Differential Evolution (DE): An evolutionary algorithm that performs well in convergence and has been combined with filter methods for gene selection [28].

- Other Algorithms: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithms (GA), and the Binary Ebola Optimization Search Algorithm (BEOSA) are also commonly used [33] [34].

Experimental Protocol for Biomarker Discovery

Objective: To identify a minimal set of biomarkers for early cancer detection using a wrapper-based feature selection approach.

Materials:

- Dataset: A dataset containing clinical and biomarker measurements (e.g., glucose, resistin, BMI, age) along with cancer diagnosis labels [32].

- Software: Python/R with optimization and machine learning libraries.

Procedure:

- Preprocessing: Similar to the filter method protocol, including normalization and train-test split.

- Search Algorithm Configuration:

- Select a metaheuristic algorithm (e.g., bABER, DE) and define its parameters (population size, iteration count).

- Define the solution representation (e.g., a binary vector where 1 indicates feature selection and 0 indicates exclusion).

- Fitness Evaluation:

- For each candidate feature subset in the population, train the chosen classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) on the training data using only the selected features.

- The fitness of the subset is the classifier's performance on a validation set (or via cross-validation). A common fitness function combines accuracy and subset size:

Fitness = α * Accuracy + (1 - α) * (1 - (#selected_features / #total_features)).

- Iteration and Selection:

- The metaheuristic algorithm iteratively generates new candidate subsets by applying evolutionary operators (e.g., mutation, crossover) and selects the best-performing ones based on their fitness.

- The process continues until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., a maximum number of iterations).

- Final Model Evaluation:

- The best feature subset found by the wrapper is used to train a final model on the entire training set.

- The model is evaluated on the independent test set to report final performance metrics (e.g., sensitivity, specificity, AUC) [32].

Performance and Applications

Wrapper methods can achieve high performance. For instance, a hybrid filter-wrapper approach that combined filter-based pre-selection with DE optimization achieved 100% classification accuracy on Brain and CNS cancer datasets with a significantly reduced feature set [28]. Another study using a wrapper approach with SVM and SBS identified a combination of five biomarkers (Glucose, Resistin, HOMA, BMI, Age) that achieved a sensitivity of 0.94 and specificity of 0.90 for breast cancer detection [32]. The primary trade-off is the computational cost associated with the extensive model training and evaluation required.

Embedded Methods

Core Principle and Workflow

Embedded methods integrate feature selection directly into the model training process. They learn which features contribute the most to the model's accuracy during the training phase itself, offering a compromise between the computational efficiency of filters and the performance of wrappers [30]. These methods often use regularization techniques to penalize model complexity and drive the coefficients of less important features toward zero.

Common Techniques and Algorithms

- Regularization-based Methods:

- LASSO (L1 Regularization): Adds a penalty equal to the absolute value of the magnitude of coefficients, which can force some coefficients to be exactly zero, effectively performing feature selection [30].

- Sparse Group Lasso: An extension that encourages sparsity at both the group and individual feature levels, useful for selecting groups of correlated genes [30].

- Tree-based Methods: Algorithms like Random Forest and XGBoost provide built-in feature importance measures (e.g., Gini importance or mean decrease in impurity) that can be used for feature selection.

- Neural Network-based Methods:

- Weighted Generalized Classifier Neural Network (WGCNN): A recently proposed embedded method that embeds feature weighting as part of training a neural network. It uses a statistical guided dropout to avoid overfitting and can capture non-linear relationships between genes, working for both binary and multi-class problems [30] [35].

Experimental Protocol for Non-linear Gene Interaction Analysis

Objective: To select relevant genes for cancer classification while capturing non-linear interactions using an embedded neural network approach.

Materials:

- Dataset: Microarray gene expression data with multiple possible classes (binary or multi-class).

- Software: A deep learning framework like TensorFlow or PyTorch, configured for the WGCNN architecture.

Procedure:

- Preprocessing: Standard steps including normalization and dataset splitting.

- Model Architecture Setup:

- Implement the WGCNN architecture, which typically includes an input layer, a pattern layer, a summation layer, a normalization layer, and an output layer [30].

- Incorporate a mechanism for learning feature weights, often as part of the input layer connections.

- Training with Guided Dropout:

- To prevent overfitting on high-dimensional data, employ a statistical guided dropout at the input layer. This dropout is based on the significance of features rather than being purely random [30].

- Train the WGCNN model on the training data. The training process simultaneously learns the classification task and the importance weights for each feature.

- Feature Selection and Model Evaluation:

- After training, extract the learned weights associated with each input feature (gene).

- Rank the genes based on the absolute values of their weights and select the top ( k ) genes.

- The performance of the selected feature subset can be evaluated by the model's final F1 score and accuracy on the test set [30].

Performance and Applications

Embedded methods like WGCNN have demonstrated strong performance in terms of F1 score and the number of features selected across several microarray datasets [30]. Their key advantage is the ability to capture complex, non-linear relationships between genes—a common characteristic in biological systems—while maintaining the efficiency of being part of the model training process. This makes them particularly powerful for genomic studies where understanding feature interactions is crucial.

Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Techniques

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of the three feature selection techniques.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Filter, Wrapper, and Embedded Feature Selection Methods

| Aspect | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods | Embedded Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Selects features based on statistical scores independent of the classifier [30]. | Selects features using the performance of a specific classifier as the guiding objective [32]. | Integrates feature selection within the model training process [30]. |

| Computational Cost | Low; fast and scalable [30]. | Very high; requires repeated model training [33]. | Moderate; more efficient than wrappers as it's part of training [30]. |

| Risk of Overfitting | Low, as no classifier is involved. | High, without proper validation (e.g., cross-validation) [33]. | Moderate, but mitigated via regularization. |

| Model Dependency | No, classifier-agnostic. | Yes, specific to a chosen classifier. | Yes, specific to a learning algorithm. |

| Handling Feature Interactions | Poor; typically evaluates features independently [30]. | Good; can capture feature dependencies. | Good; can capture interactions (e.g., non-linear via NN) [30]. |

| Primary Strengths | Computational efficiency, simplicity. | Potential for high classification accuracy. | Balance of performance and efficiency, model-specific selection. |

| Primary Weaknesses | Ignores interaction with classifier, may select redundant features. | Computationally expensive, prone to overfitting. | Limited to specific model types, can be complex to implement. |

The table below provides a quantitative performance comparison of different feature selection methods as reported in recent studies on cancer genomic data.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods on Cancer Genomic Data

| Feature Selection Method | Dataset(s) | Key Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Filter + Differential Evolution (DE) [28] | Brain, CNS, Breast, Lung Cancer | Accuracy: 100%, 100%, 93%, 98% | Achieved high accuracy with 50% fewer features than filter methods alone. |

| Wrapper (SVM with SBS) [32] | Breast Cancer | Sensitivity: 0.94, Specificity: 0.90, AUC: [0.89, 0.98] | Identified an optimal biomarker set of 5 features. |

| Embedded (WGCNN) [30] [35] | Seven Microarray Datasets | High F1 Score, Low number of selected features | Effectively captured non-linear relationships and worked for multi-class problems. |

| Binary Al-Biruni Earth Radius (bABER) [33] | Seven Medical Datasets | Statistical superiority over 8 other metaheuristics | Significantly outperformed other binary metaheuristic algorithms. |

| Voting-Based Binary Ebola (VBEOSA) [34] | Lung Cancer | Identified 10 hub genes (e.g., ADRB2, ACTB) | Successfully discovered biologically relevant hub genes for lung cancer. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Genomic Feature Selection Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Microarray Kits | Platforms for simultaneously measuring the expression levels of thousands of genes, generating the primary high-dimensional data for analysis [28]. |

| RNA-sequencing Reagents | Reagents for next-generation sequencing (NGS) that provide RNA-seq data, another common source of high-dimensional gene expression data used in cancer subtype identification [31]. |

| TCGA Data Portal | A public repository providing access to a large collection of standardized genomic and clinical data from various cancer types, serving as a vital resource for benchmarking algorithms [31] [34]. |

| STRING Database | A tool for exploring known and predicted protein-protein interactions (PPIs), used to validate the biological relevance of selected hub genes by constructing PPI networks [34]. |

| Cytoscape Software | An open-source platform for visualizing complex molecular interaction networks, often used in conjunction with PPI data from STRING [34]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for applying feature selection techniques in a cancer genomics study, integrating concepts from filter, wrapper, and embedded methods.

The following diagram represents a simplified signaling pathway influenced by hub genes identified through feature selection in lung cancer, as an example of downstream biological analysis.

The analysis of genomic data presents one of the most significant computational challenges in modern cancer research. The inherent characteristics of this data—extremely high dimensionality, significant sparsity, and frequent class imbalance—require sophisticated computational approaches for effective analysis and classification [36] [37]. Nature-inspired optimization algorithms have emerged as powerful tools for addressing these challenges, particularly in feature selection and model parameter optimization for cancer classification pipelines.

This technical guide focuses on three prominent nature-inspired optimization algorithms—Crayfish Optimization Algorithm (COA), Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)—framed within the context of genomic data feature extraction for cancer classification. We examine their fundamental mechanisms, provide comparative analysis, and detail experimental protocols for their application in cancer genomics research.

Algorithm Fundamentals

Crayfish Optimization Algorithm (COA)

COA is a swarm intelligence algorithm inspired by crayfish behaviors including summer resort, competition, and foraging [38]. The algorithm mimics crayfish behaviors through a two-phase strategy: in the exploration phase, it simulates crayfish searching for habitats to enhance global search ability, while in the exploitation phase, it mimics burrow scrambling and foraging behaviors to achieve local optimization. The algorithm is dynamically adjusted based on temperature changes, with crayfish searching for burrows to avoid the heat when the temperature exceeds 30°C and foraging when it falls below 30°C [38].