Advanced Strategies for Pharmacophore Feature Selection and Weight Optimization in Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing pharmacophore feature selection and weighting, a critical step for enhancing virtual screening success and designing selective...

Advanced Strategies for Pharmacophore Feature Selection and Weight Optimization in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing pharmacophore feature selection and weighting, a critical step for enhancing virtual screening success and designing selective inhibitors. It explores the foundational principles of pharmacophore modeling, examines cutting-edge AI and simulation-based methodologies, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and outlines robust validation frameworks. By synthesizing recent advances in deep generative models, water-based pharmacophores, and reinforcement learning, this resource offers practical strategies to improve the predictive power and application of pharmacophore models in rational drug design.

The Essential Guide to Pharmacophore Features: Core Concepts and Interaction Principles

FAQs: Core Concepts and Definitions

Q1: What is a pharmacophore in simple terms? A pharmacophore is an abstract model that defines the essential steric and electronic features a molecule must possess to interact with a biological target and trigger (or block) its biological response. It is not a specific molecule or functional group, but the common pattern of features shared by active molecules [1] [2].

Q2: What are the fundamental types of pharmacophore features? The most important pharmacophore feature types are [3] [2]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) and Donors (HBD)

- Hydrophobic areas (H)

- Positively (PI) and Negatively Ionizable (NI) groups

- Aromatic rings (AR)

- Metal coordinating areas

These features are often represented in models as geometric entities like spheres, planes, and vectors [3].

Q3: What is the main difference between structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models? The core difference lies in the input data used to generate the model [3]:

- Structure-Based Models are derived from the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from X-ray crystallography), detailing the complementary features of the binding site [4] [3].

- Ligand-Based Models are built from a set of known active (and sometimes inactive) compounds when the 3D structure of the target is unavailable, identifying common features responsible for activity [4] [3].

Q4: My pharmacophore model retrieves too many false positives during virtual screening. How can I improve its selectivity? This often indicates insufficient feature specificity or improper spatial constraints. To troubleshoot [3] [1]:

- Incorporate Exclusion Volumes: Add "forbidden areas" (XVOL) to your model to represent the physical shape and steric hindrance of the binding pocket, preventing molecules that are too large from matching [3].

- Refine Feature Selection: Re-evaluate if all features in your hypothesis are essential. Remove features that do not strongly contribute to binding energy or are not conserved across known active ligands [3].

- Validate with Inactive Compounds: Test your model against a set of known inactive molecules. If it matches them, your model lacks the discriminatory features to distinguish between active and inactive compounds [2].

Q5: How do I handle conformational flexibility when building a ligand-based pharmacophore? Conformational flexibility is a key challenge. The standard protocol involves [2]:

- Conformational Analysis: Generate a diverse set of low-energy conformations for each ligand in your training set.

- Molecular Superimposition: Systematically superimpose all combinations of the generated conformations to find the best common fit of the pharmacophoric features.

- Abstraction: The set of conformations that results in the best fit is presumed to represent the bioactive conformation and is transformed into an abstract pharmacophore model [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance in Virtual Screening

Problem: The pharmacophore model fails to enrich active compounds during the virtual screening of large compound libraries.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Incorrect Bioactive Conformation. The model may be based on a low-energy ligand conformation that is not the one adopted when bound to the target.

- Cause: Overly General or Too Specific Hypothesis. A model with too few features will lack selectivity, while one with too many may miss valid, structurally diverse hits.

- Cause: Inadequate Consideration of Tautomers and Protonation States.

- Solution: Ensure the model accounts for possible tautomeric forms and correct protonation states of the ligands at physiological pH, as these can alter hydrogen bonding and ionizable features [3].

Issue 2: Managing Feature Weights in Quantitative Models

Problem: Determining the relative importance (weights) of different pharmacophore features for predicting biological activity.

Solution - Experimental Protocol for Feature Weight Optimization: This protocol uses a genetic algorithm to assign weights to pharmacophore patterns [5].

- Data Set Preparation: Select a data set with active compounds. Choose the most active compound as the query structure. Insert the remaining active compounds into a background data set containing inactive compounds [5].

- Feature Definition: Define the pharmacophore substructures (features) using established software (e.g., Phase 3.0) [5].

- Genetic Algorithm Setup:

- Initialize a population of "individuals," where each individual is a vector of

nweight factors corresponding to thenpharmacophore features [5]. - Fitness Function: The fitness of an individual is evaluated by performing a virtual screening with the weighted query. The BEDROC score, which emphasizes early recognition performance, is optimized as the fitness criterion [5].

- Initialize a population of "individuals," where each individual is a vector of

- Evolution and Output: The genetic algorithm evolves the population over generations, selecting, crossing over, and mutating the weight vectors. The output is the weight vector of the best individual, assigning an optimized weight to each pharmacophore feature [5].

| Feature Type | Description | Common Representation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Atom that can donate a hydrogen bond (e.g., OH, NH). | Vector (directionality) | Correct protonation state is critical. |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Atom that can accept a hydrogen bond (e.g., O, N). | Vector (directionality) | Consider lone pair orientation. |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Non-polar region of the molecule. | Sphere/Volume | Often clustered for complex groups [6]. |

| Aromatic Ring (AR) | Center of an aromatic or delocalized system. | Ring/Plane | Defines planar electronic regions. |

| Positively Ionizable (PI) | Group that can carry a positive charge (e.g., amine). | Sphere | Protonation state at physiological pH. |

| Negatively Ionizable (NI) | Group that can carry a negative charge (e.g., carboxylate). | Sphere | Protonation state at physiological pH. |

| Exclusion Volume (XVOL) | Space forbidden for the ligand. | Sphere | Improves selectivity by mimicking steric clashes [3]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Model Generation

Objective: To create a pharmacophore model from a protein target's 3D structure.

Workflow:

Methodology:

- Obtain and Prepare Protein Structure:

- Source a high-resolution 3D structure of the target from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB). If an experimental structure is unavailable, use homology modeling or machine learning-based tools like AlphaFold2 [3].

- Critically evaluate and prepare the structure: Add hydrogen atoms, correct protonation states of residues, and address any missing atoms or residues. The quality of the input structure directly dictates the quality of the final model [3].

- Identify the Ligand-Binding Site:

- If the structure is a complex with a ligand, the binding site is defined by the ligand's location.

- For apo-structures, use bioinformatics tools like GRID or LUDI to detect potential binding sites based on geometric and energetic properties [3].

- Generate and Select Pharmacophore Features:

- Analyze the binding site to generate a map of potential interactions (e.g., H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic patches, charged regions).

- Select only the essential features for bioactivity. This can be done by removing features that do not contribute significantly to binding energy or by identifying conserved interactions across multiple protein-ligand complexes [3]. The final model may also include exclusion volumes to represent the receptor's shape [3].

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model Generation

Objective: To create a pharmacophore model from a set of known active ligands.

Workflow:

Methodology:

- Select a Training Set of Ligands: Choose a structurally diverse set of molecules that are known to be active against the target. Including inactive compounds can help define features that must be absent [2].

- Conformational Analysis: For each ligand in the training set, generate a comprehensive set of low-energy conformations that is likely to contain the bioactive conformation [2].

- Molecular Superimposition: Systematically superimpose ("fit") all combinations of the low-energy conformations of the molecules. The goal is to find the alignment that provides the best spatial overlap of common functional groups [2].

- Abstraction: Transform the aligned functional groups of the superimposed molecules into an abstract representation (e.g., a phenyl ring becomes an 'aromatic ring' feature, a hydroxy group becomes a 'hydrogen-bond donor' feature) [2].

- Validation: The generated pharmacophore model is a hypothesis. It must be validated by testing its ability to correctly predict the activity of a test set of compounds not used in the model building [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool/Software | Type | Primary Function in Pharmacophore Research |

|---|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [7] [1] | Software Suite | Integrated platform for molecular modeling, structure-based design, QSAR, and pharmacophore modeling. |

| Schrödinger (Phase/LiveDesign) [5] [7] | Software Suite | Provides the Phase module for ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and HypoGen for 3D QSAR pharmacophore generation [5] [1]. |

| Cresset (Flare) [7] | Software Suite | Offers tools for protein-ligand modeling and 3D pharmacophore design using field-based points. |

| Pharmer [6] | Specialized Software | An efficient, open-source algorithm for exact 3D pharmacophore search in large compound libraries. |

| LigandScout [1] | Software | Used to build structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models and perform virtual screening. |

| DataWarrior [7] | Open-Source Software | Provides cheminformatics and data analysis capabilities, including 3D pharmacophore feature perception. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [3] | Database | Primary repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, essential for structure-based modeling. |

The Critical Role of Feature Selection in Virtual Screening and Selectivity

Troubleshooting Guides

Virtual Screening Validation Failures

Reported Issue: High false positive rates and poor correlation between computational predictions and experimental validation.

| Problem Area | Specific Symptoms | Recommended Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Docking Protocol Validation | Known active compounds fail to re-dock into their native pose. RMSD > 2 Å [8]. | Perform redocking validation before screening: extract a known ligand from a crystal structure, remove it, then redock it. Optimize docking parameters until RMSD < 2 Å [8]. |

| Inadequate Feature Selection | Models perform well on training data but fail to generalize to new chemical scaffolds [9]. | Move beyond simple structural fingerprints. Use Protein-Ligand Interaction Fingerprints (PLIFs) like PADIF that capture the nature and strength of interactions, providing a more functionally relevant representation [9]. |

| Poor Decoy Selection | Machine learning models cannot distinguish between active and inactive compounds, despite high theoretical accuracy [9]. | Avoid using only random molecules or activity cut-offs for negative examples. Use recurrent non-binders from HTS assays (dark chemical matter) or carefully curated decoy sets from ZINC to create more realistic negative training data [9]. |

Achieving Target Selectivity

Reported Issue: Candidate compounds bind to multiple protein subtypes or off-targets, leading to potential side effects.

| Problem Area | Specific Symptoms | Recommended Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Ignoring Binding Site Selectivity | Molecules bind to unexpected binding sites on the target protein, leading to unpredictable effects or lack of efficacy [10]. | Integrate a binding site selectivity analysis into the screening workflow. Use machine learning models or molecular dynamics to analyze the binding tendency of candidates to specific, functionally relevant sites [10]. |

| Limited Selectivity Modeling | Standard machine learning models identify binders but perform poorly at distinguishing subtype-selective from non-selective ligands [11]. | Implement a two-step screening approach. Step 1: Identify putative binders for a target subtype. Step 2: Filter these binders to separate subtype-selective from multi-subtype ligands using specialized models [11]. |

| Over-reliance on a Single Technique | Inconsistent results between molecular docking and dynamics simulations; inability to rank true positives [12]. | Adopt a consensus and multi-technique approach. No single scoring function is universally best. Use a combination of empirical, force-field, and machine-learning-based scoring, complemented by expert visual inspection [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our team primarily uses ligand-based pharmacophore models. Why should we consider switching to protein-based pharmacophore models, and what are the key steps for generating and validating them?

A1: Ligand-based models are inherently limited by the chemical space of known actives and may miss critical interactions possible with structurally different ligands. Protein-based pharmacophore models, derived directly from the 3D structure of the binding site, offer a unbiased representation of the available interaction points, potentially revealing novel binding mechanisms [13].

Key Steps for Generation & Validation:

- Input: Use a high-quality, ligand-free protein structure with a well-defined binding site.

- Interaction Mapping: Place a 3D grid in the binding site and compute Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs) using probes representing different physicochemical properties (e.g., hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor, hydrophobic) [13].

- Pharmacophore Derivation: Cluster favorable interaction points to define pharmacophore elements (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic centers). The clustering parameters (e.g., distance cutoffs) significantly impact model quality and should be optimized [13].

- Validation: Critically assess the model's ability to reproduce known protein-ligand interactions from experimental complex structures. The model should be validated for its utility in pose prediction and virtual screening before deployment [13].

Q2: What is the most common mistake that leads to the complete failure of a virtual screening campaign, and how can it be easily avoided?

A2: The most common critical mistake is skipping the redocking validation of the molecular docking protocol. Proceeding without this step is akin to using a miscalibrated instrument for all subsequent measurements [8].

Avoidance Protocol:

- Action: Select a high-resolution crystal structure of your target protein with a bound ligand.

- Test: Extract the native ligand, then use your docking software to re-dock it back into the binding site.

- Metric: Calculate the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) between the docked pose and the original crystal pose.

- Success Criterion: An RMSD < 2.0 Å indicates a reliable protocol. If RMSD > 2.0 Å, your docking parameters (search algorithms, scoring functions, protein preparation) require optimization before screening any compounds [8]. This 30-minute step can prevent months of wasted effort on false positives.

Q3: Despite using advanced rescoring methods, including machine learning and quantum mechanics, we still struggle to discriminate true binders from false positives. What is the underlying reason, and what is the path forward?

A3: Current research indicates that no single rescoring method, regardless of its complexity, has successfully solved the general problem of distinguishing true and false positives. Failures arise from a combination of factors that are difficult to address globally, including erroneous poses, high ligand strain energy, unfavorable desolvation penalties, the critical role of explicit water molecules, and activity cliffs [12].

Path Forward:

- Acknowledge the Limitation: Understand that full automation of reliable scoring is currently an unsolved problem.

- Leverage Expert Knowledge: There is no substitute for the experienced computational chemist. Use rescoring functions to generate a shortlist of candidates, but final selection should involve visual inspection and chemical intuition to identify poses with strained conformations, unsatisfied hydrogen bonds, or polar groups in apolar pockets [12].

- Focus on Consensus: While not perfect, seeking consensus across different rescoring methods can be more robust than relying on a single approach.

Q4: How can we effectively select "decoy" molecules to train robust machine learning models for virtual screening when experimental data on true inactives is limited?

A4: The choice of decoys is critical for building ML models with high "screening power." When confirmed non-binders are unavailable, two strategies have proven effective [9]:

- Leverage Dark Chemical Matter (DCM): Use compounds from corporate or public HTS archives that have been screened multiple times and never shown activity (recurrent non-binders). These provide a realistic representation of "inactive" chemical space [9].

- Curated Random Selection: Randomly select compounds from large databases like ZINC15, but apply property-based filters (e.g., molecular weight, logP) to match the general physicochemical profile of your active set. Models trained with these decoys can perform nearly as well as those trained with true inactives [9].

- Avoid using only diverse docking conformations (DIV) of active molecules as decoys, as this can lead to models with high variability and lower performance [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Two-Step Support Vector Machine (SVM) for Selective Ligand Screening

This protocol is designed to identify subtype-selective ligands from large compound libraries, enhancing selectivity over standard single-step models [11].

1. Objective: To develop a machine learning model that first identifies potential binders and then distinguishes subtype-selective from non-selective binders.

2. Materials & Software:

- Bioactivity Data: Curated datasets of known active, inactive, and selective ligands for the target subtypes from databases like ChEMBL [11] or BindingDB [14].

- Chemical Libraries: Screening libraries such as PubChem, ZINC, or in-house collections.

- Computational Tools: Software capable of computing molecular descriptors (e.g., MOE) and a programming environment with SVM libraries (e.g., Python with scikit-learn).

- Feature Selection Method: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is recommended to identify the most critical features for selectivity [11].

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1 - Data Preparation and Featurization:

- Compile a training set containing known binders (both selective and non-selective) and confirmed non-binders for each subtype.

- Calculate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors (e.g., 2D descriptors) for all compounds.

- Use feature selection (e.g., RFE) to reduce dimensionality and identify descriptors critical for binding and selectivity.

Step 2 - Model Training (Two-Step Approach):

- First Step (Target Binding Model): Train a binary SVM classifier for a specific subtype (e.g., D2 receptor) to separate its binders (both selective and non-selective) from non-binders.

- Second Step (Selectivity Model): Train a second binary SVM classifier specifically to separate ligands that are selective for the target subtype (e.g., D2-selective) from those that bind to multiple subtypes (e.g., bind to both D2 and D3).

Step 3 - Virtual Screening:

- Pass all compounds in the screening library through the First-Step model for each subtype. Retain compounds predicted as binders.

- Pass the retained binders through the corresponding Second-Step selectivity model. The final output is a list of compounds predicted to be selective for the desired subtype.

4. Validation:

- Use internal cross-validation and an external test set with known selective and non-selective ligands to measure performance.

- Metrics should include the correct identification rates for both subtype-selective ligands and multi-subtype ligands [11].

Protocol: Optimized Protein-Based Pharmacophore Generation

This protocol details the creation of a pharmacophore model directly from a protein structure, optimized to reproduce native protein-ligand contacts [13].

1. Objective: To generate a high-quality, protein-based pharmacophore model for use in virtual screening or pose prediction.

2. Materials & Software:

- Protein Structure: A high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from PDB), preferably with a co-crystallized ligand for validation.

- Software: Molecular modeling software capable of calculating Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs) and generating pharmacophore hypotheses (e.g., Discovery Studio, MOE, or Schrödinger's Phase).

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1 - Protein Preparation:

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and optimizing hydrogen bonds.

Step 2 - Define Binding Site and Grid:

- Define the region of interest (the binding site) and place a 3D grid with a fine spacing (~0.4 Å) within it.

Step 3 - Calculate Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs):

- Compute interaction energies at each grid point using probes representing key properties: hydrogen-bond donor, hydrogen-bond acceptor, hydrophobic, aromatic, and ionic.

- Apply an Interaction Range for Pharmacophore Generation (IRFPG). Limit the distance range of favorable interactions to prevent the clustering algorithm from shifting feature centers to unrealistic positions [13].

Step 4 - Cluster MIFs to Define Pharmacophore Features:

- For hydrophobic features, apply k-means clustering over all grid points with favorable scores.

- For specific interactions (H-bond, ionic), perform clustering over grid points associated with the same protein functional group.

- Optimize clustering parameters. The distance cutoff for clustering significantly impacts model success. Test values between 1.0 - 3.0 Å to find the optimum for your target [13].

Step 5 - Generate Forbidden Volumes:

- Define exclusion volumes by clustering grid points that are closer than 2.0 Å to any protein heavy atom, representing regions where ligand atoms would sterically clash with the protein.

4. Validation:

- Validate the model by assessing its ability to reproduce the binding mode of a known ligand from a co-crystal structure.

- Use the model in a retrospective virtual screening to see if it can enrich known active compounds over decoys.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and data resources essential for conducting robust virtual screening studies focused on feature selection and selectivity.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Feature Selection & Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| BindingDB [14] | Database | Repository of experimental protein-ligand binding affinities. | Primary source for curating datasets of active/inactive/selective compounds to train machine learning models. |

| PDBbind [13] | Database | Curated collection of protein-ligand complex structures with binding data. | Used for assessing the quality of protein-based pharmacophores by providing known native contacts for validation. |

| ZINC [9] | Database | Library of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Source for screening libraries and for selecting property-matched decoy molecules to train ML models. |

| Dark Chemical Matter (DCM) [9] | Data Concept | Compounds from HTS that have never shown activity in any assay. | Provides high-quality, experimentally supported decoys for creating realistic negative training sets for ML models. |

| PADIF [9] | Computational Method | Protein per Atom Score Contributions Derived Interaction Fingerprint. | A advanced PLIF that captures nuanced interaction types and strengths, improving screening power over simple presence/absence fingerprints. |

| Redocking Validation [8] | Computational Protocol | Process of re-docking a native ligand to validate a docking setup. | A critical, often-skipped step to ensure the computational "ruler" is calibrated before screening, preventing fundamental failures. |

| Two-Step SVM [11] | Computational Method | Machine learning workflow for selectivity screening. | Specifically designed to enhance the identification of subtype-selective ligands over multi-subtype binders. |

| Protein-Based Pharmacophores [13] | Computational Model | A pharmacophore model derived solely from the protein binding site. | Avoids bias from known ligand chemotypes and can reveal novel interaction patterns critical for selectivity. |

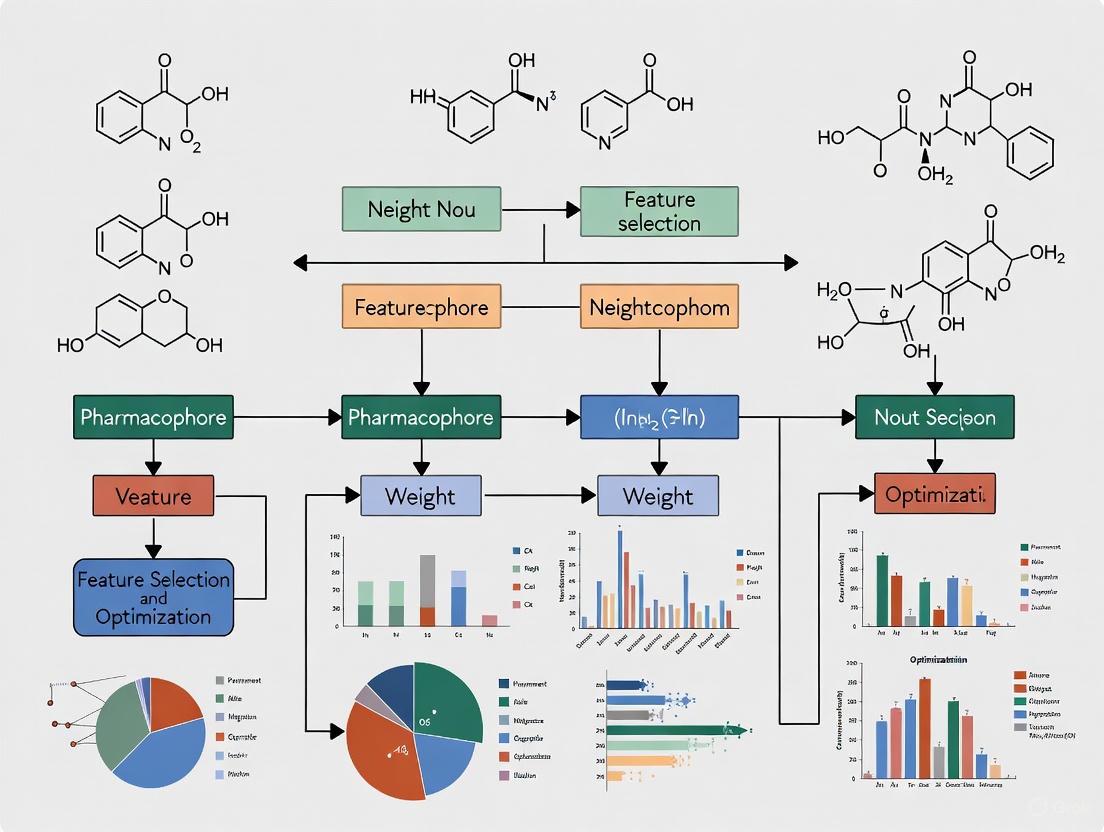

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Virtual Screening Optimization Workflow

Selectivity Screening Logic

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using coarse-grained (CG) models over all-atom models for studying protein-ligand interactions?

CG models, such as the Martini force field, significantly reduce computational cost by grouping multiple atoms into single interaction sites (beads). This coarsening enables the simulation of biological processes at microsecond to millisecond timescales, allowing for the spontaneous sampling of ligand binding and unbinding events that are often inaccessible to more detailed all-atom simulations [15] [16]. For instance, Martini 3 has been used to perform unbiased millisecond sampling of protein-ligand interactions, accurately predicting binding pockets and pathways without prior knowledge [15].

FAQ 2: How can CG approaches be integrated with pharmacophore models for more effective drug design?

CG models can act as a bridge between protein-ligand complexes and pharmacophore-based molecular generation. Frameworks like CMD-GEN first use a CG sampling module to generate three-dimensional pharmacophore points within a protein binding pocket. These pharmacophore points, which represent key interaction features, then serve as constraints for a molecular generation module that builds drug-like chemical structures. This hierarchical approach decomposes the complex problem of 3D molecule generation into more manageable steps [17].

FAQ 3: My CG simulations show unrealistic binding affinities. What could be the cause and how can it be mitigated?

Overestimated binding thermodynamics is a known challenge in some CG force fields [16]. To mitigate this:

- Force Field Version: Ensure you are using the latest version of the force field. Martini 3, for example, features improved chemical specificity and optimized molecular interactions compared to its predecessors, leading to more accurate binding free energies [15] [16].

- Validation: Always validate your CG results against available experimental data or all-atom simulations. For example, Martini 3 achieved a mean absolute error of only 1 kJ/mol for binding free energies to T4 lysozyme mutants [15].

- Enhanced Sampling: For absolute binding free energy calculations, consider integrating enhanced sampling techniques with your CG simulations to improve statistical accuracy [16].

FAQ 4: Can CG models handle protein flexibility during ligand docking?

While traditional docking often treats proteins as rigid bodies, CG MD simulations can incorporate protein flexibility. This can be achieved by combining the Martini force field with Gō-like potentials, which model the native protein structure, to allow for conformational changes [16]. This flexibility is crucial for capturing induced-fit effects and can even enable the discovery of cryptic (hidden) binding pockets that are not apparent in static protein structures [16] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Sampling of Ligand Binding/Unbinding Events

- Problem: In unbiased simulations, the ligand fails to bind to the protein or remains trapped in the bound state without dissociating.

- Solution:

- Extend Simulation Time: CG models like Martini enable longer timescales, but some systems may still require extensive sampling. Consider running multiple independent simulations or extending simulation time [15].

- Ligand Concentration: Ensure the ligand concentration in your simulation box is physiologically relevant. The cited Martini study used a concentration of ~1.6 mM [15].

- Employ Enhanced Sampling: If brute-force simulation is not feasible, use enhanced sampling techniques. The Push-Pull-Release (PPR) method is one such strategy that facilitates dissociation and reassociation by applying a biasing potential to cycle the proteins between associated and dissociated states [19].

Issue 2: Inaccurate Ligand Binding Pose or Failure to Identify the Correct Binding Site

- Problem: The simulated ligand density does not overlap with the known crystallographic binding pose, or binds to a non-physiological site.

- Solution:

- Parameter Validation: Double-check the CG parameters for both the ligand and the protein. Incorrect bead assignment or bonded interactions are a common source of error. Use available automated tools like

auto-martiniorPyCGTOOLwhere possible, and validate against atomistic simulations [16]. - Force Field Selection: Use a force field with sufficient chemical specificity. Martini 3 has a broader coverage of chemical groups found in drugs, which is critical for accurate pose prediction [15] [16].

- Incorporate Knowledge: For challenging targets, consider integrating prior knowledge. A deep learning framework like DiffPhore uses pre-computed pharmacophore models to guide ligand conformation generation, ensuring poses are consistent with known interaction patterns [20].

- Parameter Validation: Double-check the CG parameters for both the ligand and the protein. Incorrect bead assignment or bonded interactions are a common source of error. Use available automated tools like

Issue 3: Lack of Selectivity in Generated Drug Candidates

- Problem: Molecules generated by a computational framework show poor selectivity for the intended target over related off-targets.

- Solution:

- Leverage Pharmacophore Synergism: Develop QSAR models to identify critical pharmacophoric features and their combinations that drive binding to your target. Analyzing feature synergism can reveal selectivity determinants [21].

- Multi-Target Conditioning: Use a generative model capable of multi-conditional control. The CMD-GEN framework, for instance, can be guided by pharmacophore point clouds from multiple related targets (e.g., PARP1 and PARP2), allowing for the deliberate design of either selective or dual-target inhibitors [17].

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from coarse-grained simulation studies of protein-ligand binding.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Coarse-Grained Martini 3 for Protein-Ligand Binding

| System / Metric | Performance Result | Context / Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| T4 Lysozyme L99A - Benzene Binding [15] | 156 binding / 147 unbinding events (0.9 ms total sampling) | Demonstrates reversible binding and sufficient sampling for kinetics. |

| Binding Pose Accuracy (RMSD) [15] | 1.4 ± 0.2 Å (Benzene in T4L L99A) | Excellent agreement with crystal structure; similar to atomistic MD. |

| Binding Free Energy (ΔG) Accuracy [15] | Mean Absolute Error: 1 kJ/mol; Max Error: 2 kJ/mol | Compared to experimental data for T4 lysozyme ligands. |

| Virtual Screening (DiffPhore) [20] | Superior performance vs. traditional pharmacophore tools & advanced docking | Evaluated on PDBBind and PoseBusters test sets for binding conformation prediction. |

Table 2: Key Datasets for 3D Ligand-Pharmacophore Model Development

| Dataset Name | Size | Key Characteristics | Application in Model Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| CpxPhoreSet [20] | 15,012 pairs | Derived from experimental protein-ligand complexes; contains "real-world" imperfect mappings. | Model refinement to understand induced-fit effects and biased LPMs. |

| LigPhoreSet [20] | 840,288 pairs | Generated from diverse ligand conformations; features perfect ligand-pharmacophore pairs. | Initial training to capture generalizable LPM patterns across broad chemical space. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Unbiased Coarse-Grained Binding Simulation with Martini

This protocol outlines the procedure for simulating spontaneous protein-ligand binding using the Martini CG model, as applied to T4 lysozyme [15].

System Setup:

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the protein structure (e.g., from PDB). Convert it to the Martini CG representation. For flexibility, consider using a Go̅-model combination [16].

- Ligand Parametrization: Map the ligand's atomistic structure to Martini beads. Validate the CG model by comparing its properties to atomistic simulations or experimental data [16].

- Solvation and Box Creation: Place the protein in a simulation box (e.g., 10 nm cubic box for T4 lysozyme). Fill the box with ~8850 CG water beads (representing 35,400 water molecules). Add ions to neutralize the system.

- Ligand Placement: A single ligand should be placed randomly in the solvent. This corresponds to a concentration of ~1.6 mM in the given example [15].

Simulation Execution:

- MD Parameters: Use Langevin dynamics for temperature coupling. A friction coefficient of 50 ps⁻¹ and a time step of 0.01 ps are suitable for the Martini force field [19].

- Sampling Strategy: Run multiple independent, unbiased MD trajectories (e.g., 30 trajectories of 30 µs each for a total of 0.9 ms). This improves sampling statistics.

- Analysis:

- Binding Events: Track the distance between the ligand and the protein's binding pocket to identify binding and unbinding events.

- Ligand Density: Calculate the 3D density of the ligand around the protein to identify binding sites and pathways. The density in the primary pocket can be >1000 times higher than in bulk water [15].

- Binding Free Energy: Compute the potential of mean force (PMF) along a reaction coordinate (e.g., distance from the binding site) and integrate to obtain ΔG_bind [15].

Protocol 2: CMD-GEN Framework for Structure-Based Molecular Generation

This protocol describes the workflow for generating drug-like molecules tailored to a specific protein pocket using the CMD-GEN framework [17].

- Input: A 3D structure of the target protein pocket.

- Coarse-Grained Pharmacophore Sampling:

- Use a diffusion model to sample a cloud of coarse-grained pharmacophore points (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic centers) within the spatial constraints of the protein pocket. This step effectively abstracts the pocket's essential interaction features.

- Chemical Structure Generation:

- Feed the sampled pharmacophore point cloud into the Gating Condition Mechanism and Pharmacophore Constraints (GCPG) module.

- This transformer-based module converts the geometric pharmacophore information into a valid molecular structure (e.g., represented as a SMILES string) that satisfies the pharmacophore constraints.

- Conformation Prediction and Alignment:

- Generate a 3D conformation for the newly generated molecule.

- Align this conformation with the original pharmacophore point cloud to ensure the molecule's functional groups match the intended spatial interactions.

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: CMD-GEN Hierarchical Molecular Generation Workflow. This illustrates the pipeline for generating molecules by first creating a coarse-grained pharmacophore model from a protein structure [17].

Diagram 2: Push-Pull-Release (PPR) Enhanced Sampling. This cycle overcomes energy barriers to improve sampling of protein association/dissociation [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for CG-Based Drug Discovery

| Tool / Resource Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Martini Force Field [15] [16] | Coarse-Grained Force Field | Provides the interaction parameters for simulating proteins, lipids, drugs, and solvents at a reduced level of detail, enabling long-timescale simulations. |

| Martini Database (MAD) [16] | Parameter Database | A curated repository of validated Martini CG models for small molecules and fragments, ensuring parameter reliability. |

| Auto-martini / PyCGTOOL / Swarm-CG [16] | Automated Parameterization Tool | Assists in the automatic conversion of atomistic structures to CG representations and the derivation of bonded parameters for new molecules. |

| DiffPhore [20] | Deep Learning Framework | A knowledge-guided diffusion model for predicting 3D ligand binding conformations that match a given pharmacophore model. |

| CMD-GEN [17] | Deep Generative Model | A hierarchical framework that uses coarse-grained pharmacophore sampling and conditional generation to design molecules for a target pocket. |

Core Concepts: LB and SB Methods Defined

What are the fundamental differences between Ligand-Based (LB) and Structure-Based (SB) drug design approaches?

The core distinction lies in the starting information used for drug discovery. Ligand-Based (LB) Design relies on the structural information and physicochemical properties of known active molecules (ligands) to predict new active compounds, applying the "molecular similarity principle" that similar molecules often have similar biological activity [22] [23]. In contrast, Structure-Based (SB) Design utilizes the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the target protein (often obtained through X-ray crystallography, NMR, or Cryo-EM) to design molecules that complement the binding site's shape and chemical features [22] [17].

Table: Comparison of Ligand-Based vs. Structure-Based Drug Design Approaches

| Feature | Ligand-Based (LB) Design | Structure-Based (SB) Design |

|---|---|---|

| Required Information | Known active ligands [22] | 3D structure of the target protein [22] |

| Primary Objective | Identify new actives based on similarity to known ligands [22] | Design molecules that fit and bind to the target's binding site [22] |

| Common Techniques | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR), Pharmacophore Modeling, LB Virtual Screening [24] [22] | Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics, SB Virtual Screening [22] [23] |

| Key Advantage | Does not require the target protein structure; faster and less resource-intensive for screening [22] | Provides atomic-level insight into binding interactions; enables rational design of novel scaffolds [22] |

| Main Limitation | Bias towards known chemical scaffolds; cannot design entirely novel motifs [23] | Dependent on availability and quality of protein structure; computationally expensive [22] [23] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: My ligand-based pharmacophore model retrieves too many false positives during virtual screening. How can I improve its selectivity?

A high rate of false positives often indicates that the pharmacophore model is not restrictive enough or lacks key three-dimensional information [24].

- Solution A: Validate and Refine the Model. Use a test set containing both active (true-positives) and inactive (decoys) compounds to validate the model's ability to distinguish between them [24]. If the model performs poorly, adjust the chemical features (e.g., Hydrogen Bond Acceptors, Donors, Hydrophobic regions) and their spatial tolerances. A study on c-Jun N-terminal kinase-3 (JNK3) inhibitors demonstrated that a well-validated ligand-based pharmacophore model (Hypo1) achieved a high correlation coefficient (r² = 0.846) on a test set of 85 inhibitors [25].

- Solution B: Integrate Structure-Based Insights. If the protein structure is available, generate a structure-based pharmacophore model to identify essential interaction features from the binding site [25] [23]. Comparing and merging the key features from both models can create a more robust and selective hybrid pharmacophore. For instance, the JNK3 study found that while the LB model identified two hydrogen bond acceptors, one donor, and a hydrophobic feature, the structure-based model revealed two additional hydrogen bond donors and an acceptor, leading to a more "ideal pharmacophore" [25].

- Solution C: Apply Sequential Filtering. Use the initial pharmacophore model as a fast pre-filter to reduce the chemical space. Then, apply a more computationally intensive structure-based method like molecular docking to the resulting hits to re-rank them based on predicted binding poses and scores [23] [26]. This combination leverages the speed of LB methods and the precision of SB methods.

FAQ 2: When the protein target is highly flexible, my structure-based docking results are inconsistent. What strategies can I use?

Accounting for protein flexibility remains a major challenge in structure-based design, as rigid docking can produce unreliable results if the binding site undergoes conformational changes [23].

- Solution A: Use Multiple Protein Conformers. Instead of a single static structure, perform docking against an ensemble of different protein conformations. These can be obtained from:

- Solution B: Employ Flexible Residue Docking. Many advanced docking programs allow for side-chain flexibility of key binding site residues. This can be a computationally efficient compromise between full protein flexibility and a rigid receptor.

- Solution C: Switch to a Ligand-Based Approach. If resolving flexibility issues is not feasible, a ligand-based method can be a powerful alternative. Techniques like 3D-QSAR or ligand-based pharmacophore modeling do not require the protein structure and are unaffected by its flexibility [27] [22].

FAQ 3: How can I design a selective inhibitor for one protein subtype over another (e.g., PARP1 vs. PARP2) when their binding sites are very similar?

Designing selective inhibitors is a complex task that benefits immensely from a hybrid LB+SB strategy [17].

- Solution A: Leverage Consensus Pharmacophore Modeling from Multiple Complexes. Generate structure-based pharmacophore models for both protein subtypes using multiple ligand-bound complexes. A tool like ConPhar can systematically extract and cluster pharmacophoric features from many aligned complexes to create a consensus model for each target [28]. Comparing these consensus models can reveal subtle differences in the spatial arrangement or type of chemical features that are unique to one subtype.

- Solution B: Utilize Advanced AI-Driven Generation. New deep learning frameworks, such as CMD-GEN, are specifically designed for challenges like selective inhibitor generation [17]. This framework uses a coarse-grained pharmacophore sampling module to model the 3D chemical environment of a pocket, which then guides the generation of novel chemical structures. This approach was successfully validated in the design of selective PARP1/2 inhibitors [17].

- Solution C: Focus on Dynamic and Allosteric Sites. If the active sites are nearly identical, analyze differences in dynamic behavior via MD simulations or look for less-conserved allosteric binding sites that can be targeted for selectivity [22].

Integrating LB and SB Methods: A Hybrid Framework

Combining ligand-based and structure-based approaches can mitigate the limitations of each and enhance the success of drug discovery projects [23] [26]. The integration can be achieved through three main strategies:

- Sequential Approach: The VS pipeline is divided into consecutive steps. Typically, a fast LB method (e.g., pharmacophore screening) is used for pre-filtering a large library, and the resulting hits are passed to a more computationally demanding SB method (e.g., molecular docking) for final selection [23] [26].

- Parallel Approach: LB and SB methods are run independently on the same compound library. The resulting ranked lists are then combined, and compounds that rank highly in both lists are prioritized for experimental testing [26].

- Hybrid Approach: This involves methods that intrinsically use information from both ligands and the target structure simultaneously. An example is using a pharmacophore model derived from the protein binding site (SB) to constrain a molecular docking calculation (SB) or to guide a ligand-based similarity search (LB) [23] [26].

The following diagram illustrates how these strategies can be combined into a cohesive virtual screening workflow.

Experimental Protocol: Generating a Consensus Pharmacophore Model

This protocol details the generation of a consensus pharmacophore model from multiple ligand-protein complexes using the open-source tool ConPhar, as adapted from a published methodology [28]. This approach is invaluable for targets with extensive structural data, such as the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) [28].

1. Preparation of Ligand Complexes

- Align Structures: Use molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL) to align all protein-ligand complexes based on the target protein's backbone [28].

- Extract Ligands: Extract the 3D coordinates of each aligned ligand and save them as individual files in SDF format [28].

2. Feature Extraction with Pharmit

- Load Ligands: Individually upload each ligand SDF file to Pharmit (a free-access web server for pharmacophore screening) [24] [28].

- Generate Pharmacophores: Use Pharmit's "Load Features" option to automatically generate a pharmacophore model for each ligand. Save each model as a JSON file [28].

3. Consensus Generation with ConPhar in Google Colab

- Environment Setup: Launch a new Google Colab notebook. Install Conda, PyMOL, and the ConPhar package using the provided installation scripts [28].

- Load JSON Files: Create a dedicated folder in Colab and upload all the pharmacophore JSON files from the previous step [28].

- Parse and Consolidate: Execute the ConPhar script to parse all JSON files and consolidate the extracted pharmacophoric features (e.g., Hydrogen Bond Acceptors, Donors, Hydrophobic features) into a single data table [28].

- Generate Consensus Model: Run the consensus algorithm, which clusters the features from all ligands based on their type and 3D location. The output is a single, robust consensus pharmacophore model that captures the essential interaction points common across the ligand set [28].

- Visualize and Export: The final model can be visualized directly in PyMOL within Colab and exported for use in virtual screening [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table: Key Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

| Tool / Reagent Name | Type/Category | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Commercial Software | LB & SB Pharmacophore Modeling | Advanced algorithms for automatic 3D pharmacophore model generation from complexes [24]. |

| Pharmit | Free Web Server | SB Pharmacophore Screening | Interactive, fast virtual screening against a public compound database using pharmacophore queries [24] [28]. |

| ConPhar | Open-Source Tool | Consensus Pharmacophore Generation | Systematically extracts and clusters features from multiple ligand complexes into a single model [28]. |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Commercial Software Suite | Comprehensive CADD Platform | Integrated environment for QSAR, pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and simulations [24]. |

| PyMOL | Molecular Visualization Software | Structure Analysis & Rendering | Used for aligning protein structures, analyzing binding sites, and visualizing results [28]. |

| CMD-GEN | AI-Based Framework | Structure-Based Molecular Generation | Generates novel drug-like molecules by bridging coarse-grained pharmacophore points with chemical structures [17]. |

AI and Simulation-Driven Methods for Next-Generation Pharmacophore Modeling

Deep Generative Models for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Sampling (CMD-GEN, DiffPharm)

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Poor Pharmacophore Matching in Generated Molecules

Problem Description Generated molecules do not adequately satisfy the spatial and chemical constraints defined by the input pharmacophore model, leading to low alignment scores.

Possible Causes & Solutions

| Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Model |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Distance Mapping | Ensure proper conversion between Euclidean distances in the pharmacophore and shortest-path distances on the molecular graph. Refer to mapping rules in supplementary materials [29]. | CMD-GEN, PGMG |

| Low Diversity in Latent Sampling | Increase the number of latent variable z samples from the prior distribution ( N(0,I) ) to explore more modes in the conditional distribution [29]. |

PGMG |

| Suboptimal Graph Encoding | Verify that the graph neural network (Gated GCN) correctly encodes the spatially distributed chemical features of the pharmacophore hypothesis [29]. | PGMG |

| Inadequate Denoising Process | Check that pharmacophore constraints are properly injected into the equivariant transformer during the denoising steps [30]. | DiffPharm |

Issue 2: Low Validity or Uniqueness of Generated Molecules

Problem Description The generative model produces a high rate of invalid SMILES strings or repeatedly generates the same molecular structures.

Possible Causes & Solutions

| Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Model |

|---|---|---|

| SMILES Grammar Violations | Use a transformer backbone trained with a larger corpus of SMILES strings to better learn implicit grammatical rules [29]. | PGMG |

| Limited Chemical Space Exploration | Introduce latent variables to model the many-to-many relationship between pharmacophores and molecules, boosting variety [29]. | PGMG |

| Deterministic Generation | In DiffPharm, ensure the diffusion process is stochastic and that the noise sampling is correctly implemented [30]. | DiffPharm |

Issue 3: Inefficient Generation for Large Pharmacophores

Problem Description The model experiences slow inference times or memory overflow when processing pharmacophore models with a large number of features.

Possible Causes & Solutions

| Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Model |

|---|---|---|

| High Graph Complexity | The space complexity of graph-based models increases with the square of the node number. Consider feature reduction or partitioning [31]. | General |

| Long SMILES Sequences | For transformer decoders, use techniques like attention window optimization to handle long sequences [29]. | PGMG |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What types of pharmacophore data can be used as input for CMD-GEN? CMD-GEN utilizes coarse-grained pharmacophore points sampled from diffusion models, bridging 3D ligand-protein complex data with 2D drug-like molecule data. This enriches the training data for the generative model [32].

Q2: How does DiffPharm ensure 3D pharmacophore constraints are met during generation? DiffPharm encodes 3D pharmacophore models as graphs and injects these constraints directly into an equivariant transformer architecture throughout the denoising process of a diffusion model. This design maintains strong pharmacophore alignment for the generated conformations [30].

Q3: How do these models handle the "many-to-many" relationship between pharmacophores and molecules?

PGMG explicitly addresses this by introducing a set of latent variables z. A molecule x is represented by the combination of the pharmacophore encoding c and z, which governs the placement of chemical groups. This allows the model to capture multiple valid molecular solutions for a single pharmacophore [29].

Q4: Can these models be used for targets with limited known active molecules? Yes. A key advantage of PGMG is that it avoids using target-specific activity data during its primary training stage. It is trained on general molecular datasets like ChEMBL, bypassing the problem of data scarcity for novel targets [29].

Q5: What are the key metrics for evaluating the success of generated molecules? Beyond standard generative model metrics (validity, uniqueness, novelty), key evaluation metrics include the pharmacophore match score (how well the molecule fits the input constraints) and predicted or calculated docking scores to assess binding affinity [29] [30].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Preparing a Training Sample for PGMG

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a single training instance for the PGMG model from a molecule's SMILES string [29].

- Input SMILES: Begin with a canonical SMILES string of a molecule from a training database (e.g., ChEMBL).

- Feature Identification: Use RDKit to identify the molecule's chemical features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, positive/negative charges).

- Build Pharmacophore Graph: Randomly select a subset of these chemical features. Construct a pharmacophore graph ( G_p ) where:

- Nodes represent the selected pharmacophore features.

- Edges are defined by the shortest-path distances on the molecular graph between the atoms associated with these features. This graph distance serves as a proxy for 3D Euclidean distance.

- Create SMILES Token Sequence: Generate a randomised SMILES string from the molecule and segment it into a token sequence ( s ).

- Corrupt Sequence: Apply an infilling scheme to corrupt sequence ( s ) and create the encoder input ( s' ).

- Final Sample: The complete training sample is the tuple ( (G_p, s, s') ).

Protocol 2: Structure-Based Molecular Generation with DiffPharm

This protocol describes the process for generating molecules using a 3D structure-based pharmacophore and the DiffPharm model [30].

- Pharmacophore Definition: Define a 3D pharmacophore model based on a target protein's binding site. This model is an ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary for optimal supramolecular interactions.

- Graph Encoding: Encode this 3D pharmacophore model as a pharmacophore graph, where nodes are chemical features and edges represent their spatial relationships.

- Constraint Injection: This pharmacophore graph is used as a constraint set. It is injected into an E(3)-equivariant transformer architecture during the denoising process of the diffusion model.

- Molecular Generation: The diffusion model generates 3D molecular structures that are chemically valid and conform to the injected pharmacophore constraints.

- Inpainting (Optional): If a core scaffold (substructure) must be preserved, utilize DiffPharm's inpainting capability, which allows generation under simultaneous substructure and pharmacophore constraints.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Relevance to CMD-GEN/DiffPharm |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for identifying chemical features from molecules, handling SMILES strings, and molecular operations [29]. | Used in PGMG for pharmacophore feature identification and building the pharmacophore graph from a SMILES string. |

| ChEMBL Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, containing millions of compounds and their experimental bioactivity data [31]. | Serves as a primary source of training data for models like PGMG to learn general molecular patterns without target-specific data. |

| ZINC Database | A massive, freely available collection of commercially available, "drug-like" compounds for virtual screening [31]. | Useful for pre-training generative models and for virtual screening of generated molecules. |

| Gromacs | A versatile software package for molecular dynamics simulations, used for conformational optimization and energy minimization [33]. | In tools like DrugOn, it is used for receptor structure optimization before pharmacophore modeling and drug design. |

| Ligbuilder | A software suite for de novo drug design that can grow or link molecular fragments within a defined binding pocket [33]. | Used in integrated pipelines (e.g., DrugOn) for the structure-based design of novel ligands after receptor optimization. |

| PharmACOphore | A program used for the pairing of ligands and the construction of 3D pharmacophore models [33]. | A core component in pipelines like DrugOn for generating the pharmacophore models that could guide generative models. |

Workflow and System Architecture Diagrams

PGMG Training and Generation Workflow

DiffPharm's Diffusion-Based Generation

Leveraging Molecular Dynamics for Water-Based and Dynamic Pharmacophores

In modern computational drug discovery, dynamic pharmacophore modeling has emerged as a powerful paradigm that moves beyond static structural snapshots to capture the essential flexibility of biological systems. By integrating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations with pharmacophore generation, researchers can account for protein flexibility, solvent effects, and the true dynamic nature of binding interactions. This approach is particularly valuable for optimizing pharmacophore feature selection and weights, as it provides a thermodynamic and kinetic basis for identifying which chemical features are essential for binding affinity and specificity. Unlike traditional methods that might rely on single crystal structures, dynamic pharmacophores incorporate the temporal dimension, revealing transient binding pockets and interaction patterns that would otherwise remain undetected. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance for researchers implementing these advanced methods in their drug discovery pipelines.

Key Concepts & FAQs

Fundamental Principles

What is a dynamic pharmacophore and how does it differ from traditional pharmacophore models? A dynamic pharmacophore is an ensemble of pharmacophore features derived from multiple conformational states of a protein-ligand complex, typically generated through MD simulations. Unlike traditional static models based on a single crystal structure, dynamic pharmacophores capture the temporal evolution of binding sites and interactions, providing a more physiologically relevant representation of the binding process [34]. The "dyphAI" approach exemplifies this by integrating machine learning, ligand-based models, and complex-based models into a pharmacophore model ensemble that captures key protein-ligand interactions such as π-cation interactions and π-π interactions with critical residues [34].

Why is explicit solvent representation important in pharmacophore modeling? Explicit water molecules play crucial roles in ligand binding that cannot be captured by implicit solvent models. Water-mediated interactions can significantly influence binding affinity and specificity. In structure-based pharmacophore modeling, explicit waters can be treated as:

- Bridge features that facilitate hydrogen bonding between ligand and protein

- Displacement sites where high-energy waters can be targeted for displacement to improve binding affinity

- Exclusion volumes that define regions inaccessible to ligand atoms Incorporating water-based features provides a more accurate representation of the binding environment and can lead to improved virtual screening performance [35].

How do MD simulations improve pharmacophore feature selection and weighting? MD simulations generate an ensemble of protein conformations that sample the thermodynamic landscape of the binding site. By analyzing this ensemble, researchers can:

- Distinguish between persistent interactions (highly weighted features) and transient interactions (lower weighted features)

- Identify allosteric pockets and cryptic sites not visible in static structures

- Calculate occupancy rates and interaction energies to objectively weight pharmacophore features

- Detect water residence sites that contribute to binding thermodynamics [34] [35] This data-driven approach to feature selection and weighting represents a significant advancement over heuristic methods used in traditional pharmacophore modeling.

Implementation Strategies

What are the main approaches for generating dynamic pharmacophores? Table 1: Dynamic Pharmacophore Generation Methods

| Method | Description | Best Use Cases | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectory Clustering | Cluster MD snapshots and generate pharmacophores for representative structures | Systems with multiple distinct conformational states | Captures major conformational variants |

| Ensemble Pharmacophores | Combine features from multiple MD frames into a single comprehensive model | Identifying conserved interaction patterns | Comprehensive coverage of interaction space |

| Time-Window Averaging | Generate sequential pharmacophores over specific simulation time windows | Studying binding process evolution | Reveals temporal interaction patterns |

| Machine Learning Enhancement | Apply ML algorithms to identify essential features from MD trajectories | Large-scale simulation data analysis | Objective feature selection and weighting [34] |

How can water-based features be incorporated into pharmacophore models? Water-based pharmacophore features can be implemented through several strategies:

- High-Occupancy Water Sites: Identify water molecules with >80% occupancy in the binding site during MD simulations and include as hydrogen bond features

- Energetic Analysis: Calculate interaction energies for water molecules using methods like Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (GIST) to identify favorable displacement sites

- Bridging Water Detection: Identify water molecules that consistently form hydrogen bond bridges between protein and ligand

- Explicit Water Pharmacophores: Generate pharmacophore features directly from water oxygen positions with specific interaction geometries [35]

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Technical Challenges

Problem: Excessive Feature Density in Ensemble Pharmacophores Symptoms: Virtual screening yields few or no hits; pharmacophore model contains too many features to be practically useful Solutions:

- Apply feature persistence filtering - retain only features present in >70% of simulation frames

- Implement spatial clustering - group similar features within a defined radius (e.g., 1.0 Å)

- Use energy-based weighting - prioritize features with favorable interaction energies from MM-PBSA/GBSA calculations

- Apply machine learning feature selection - use random forest or LASSO regression to identify most discriminatory features [34] [36]

Problem: Poor Virtual Screening Enrichment Symptoms: High false positive rate; active compounds not preferentially selected Solutions:

- Validate with known actives/inactives - ensure model can distinguish established binders from non-binders

- Optimize feature tolerances - adjust distance and angle tolerances based on MD fluctuation data

- Incorporate exclusion volumes - add excluded volume spheres based on protein atom occupancy maps from MD

- Implement consensus scoring - combine pharmacophore matching with energy-based scoring [37] [36]

Problem: Water Feature Instability Symptoms: High turnover of water molecules in binding site; inconsistent water-mediated interactions Solutions:

- Extend simulation time to improve water sampling statistics

- Use metadynamics or other enhanced sampling to accelerate water exchange

- Apply spatial occupancy maps rather than individual water molecules

- Implement collective variable analysis to identify stable water networks [35]

Performance Optimization

Problem: Computational Resource Limitations Symptoms: MD simulations insufficiently converged; inadequate sampling for meaningful pharmacophore ensemble Solutions:

- Implement progressive sampling - start with short replicates to identify key motions before long production runs

- Use accelerated MD methods to enhance conformational sampling

- Apply trajectory compression algorithms to reduce storage requirements

- Utilize cloud computing resources for parallel simulation of multiple system variants [34]

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Dynamic Pharmacophore Generation Protocol

Dynamic Pharmacophore Workflow: This diagram illustrates the standard protocol for generating dynamic pharmacophores from MD simulations, showing the sequential stages from system preparation through to validated model generation.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- System Preparation

- Obtain protein structure from PDB or homology modeling

- Process with protein preparation tools (e.g., Schrodinger's Protein Preparation Wizard)

- Add missing residues and loops as needed

- Assign appropriate protonation states at physiological pH

- Parameterize small molecule ligands using appropriate force fields

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

- Solvate system in explicit water (TIP3P/SPC water models)

- Neutralize system with appropriate ions (Na+/Cl-)

- Energy minimization using steepest descent/conjugate gradient (5000 steps)

- Equilibration in NVT and NPT ensembles (100-500 ps each)

- Production simulation (50-100+ ns) with 2 fs timestep

- Save trajectories at appropriate intervals (10-100 ps)

Trajectory Analysis and Clustering

- Align trajectories to reference structure to remove rotational/translational motion

- Calculate RMSD/RMSF to assess convergence and flexibility

- Perform clustering (e.g., k-means, hierarchical) on binding site residues

- Select representative frames from largest clusters for pharmacophore generation

Pharmacophore Generation and Validation

Water-Based Feature Identification Protocol

Water Feature Identification: This workflow shows the specialized process for identifying and characterizing water-based pharmacophore features from MD trajectories with explicit solvent.

Detailed Methodology:

- Water Molecule Tracking

- Identify all water molecules within binding site region

- Calculate spatial occupancy using 3D density maps

- Determine residence times using continuous survival correlation function

- Classify waters as structural (long residence) or bulk (short residence)

Interaction Analysis

- Calculate hydrogen bond lifetimes and stability

- Identify bridging waters that connect protein and ligand atoms

- Analyze water-water interaction networks in binding site

- Compute interaction energies for high-occupancy waters

Feature Incorporation

- Create hydrogen bond features for stable water positions (>80% occupancy)

- Define displacement features for high-energy waters

- Add exclusion volumes based on protein atom occupancy

- Set appropriate distance and angular tolerances based on fluctuations [35]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Dynamic Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Resources | Key Functionality | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM | Molecular dynamics simulations | GROMACS recommended for balance of performance and features |

| Trajectory Analysis | MDTraj, MDAnalysis, CPPTRAJ | Trajectory processing and analysis | MDAnalysis offers excellent Python integration |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | LigandScout, MOE, Schrodinger | Pharmacophore generation and screening | LigandScout excels in structure-based modeling |

| Water Analysis | GIST, VolMap, TRAVIS | Solvation site analysis | GIST provides detailed thermodynamic profiling |

| Machine Learning Integration | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Feature selection and weighting | Scikit-learn sufficient for most applications |

| Validation Tools | DUD-E, DEKOIS, ROCS | Model validation and enrichment calculation | DUD-E provides standardized decoy sets |

Advanced Applications & Case Studies

Successful Implementations

Case Study: Alzheimer's Disease Target (AChE Inhibition) The dyphAI approach demonstrated the power of dynamic pharmacophores for identifying novel acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors. By integrating MD simulations with machine learning and pharmacophore ensembles, researchers identified key interactions with residues Trp-86, Tyr-341, Tyr-337, Tyr-124, and Tyr-72. This approach led to the discovery of 18 novel AChE inhibitors from the ZINC database, with experimental validation confirming several compounds exhibiting IC₅₀ values superior to the control drug galantamine [34].

Case Study: XIAP Protein for Cancer Therapy Structure-based pharmacophore modeling combined with MD simulations identified natural compounds targeting the XIAP protein. The pharmacophore model included 14 chemical features derived from protein-ligand complex analysis. Validation showed excellent discriminative power with an AUC value of 0.98 and early enrichment factor of 10.0, leading to identification of three promising natural compounds with potential anticancer activity [36].

Emerging Trends

AI-Enhanced Dynamic Pharmacophores Recent advances integrate deep learning with pharmacophore modeling. The PGMG (Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation) uses graph neural networks to encode spatially distributed chemical features and transformers to generate molecules matching specific pharmacophores. This approach addresses the "many-to-many" mapping challenge between pharmacophores and molecules through latent variable modeling [29].

High-Throughput Dynamic Pharmacophore Screening Tools like Pharmer enable efficient large-scale screening using pharmacophore queries. Pharmer uses innovative data structures (KDB-trees) and algorithms (Bloom fingerprints) to perform exact pharmacophore searches of millions of compounds in minutes rather than days, enabling practical screening of dynamic pharmacophore ensembles against large compound libraries [6].

Reinforcement Learning for Automated Feature Elucidation (PharmRL)

Within the domain of structure-based drug design, pharmacophore models represent a critical abstraction of the essential steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target. The process of elucidating an optimal set of features—a pharmacophore—from a protein binding site, particularly in the absence of a known ligand (apo structures), remains a significant challenge. Traditional methods often rely on computationally intensive fragment docking or molecular dynamics simulations, followed by expert-guided manual selection of features, introducing bias and limiting throughput. The integration of Reinforcement Learning (RL) presents a paradigm shift, enabling data-driven, automated exploration of the pharmacophore feature space to identify subsets optimal for virtual screening performance. This technical support center is designed to assist researchers in implementing and troubleshooting RL-based pharmacophore elucidation, specifically within the context of the PharmRL framework, to advance research in optimizing pharmacophore feature selection and weights [38] [39] [40].

Core Concepts: The PharmRL Framework

What is the fundamental architecture of the PharmRL pipeline?

The PharmRL method employs a two-stage deep learning approach to address the pharmacophore elucidation problem [38] [39].

Stage 1: Interaction Feature Identification. A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is trained to identify potential favorable interaction points directly from the 3D structure of a protein binding site. The model is trained on pharmacophore features derived from protein-ligand co-crystal structures in the PDBBind dataset.

- Input: A voxelized representation of the protein structure within a cubic volume (9.5 Å edge, 0.5 Å resolution) centered on a grid point [38] [39].

- Output: A multi-label classification predicting the presence of one or more of six pharmacophore feature classes at the evaluated point: Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA), Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD), Hydrophobic (H), Aromatic (A), Negative Ion (N), and Positive Ion (P) [38] [40].

- Adversarial Training: The CNN is retrained using adversarial samples to enhance robustness. This involves labeling predictions that are too close to protein atoms or too distant from complementary protein functional groups as negative examples [38] [39].

Stage 2: Optimal Feature Subset Selection. The candidate features from the CNN are processed (clustered, refined) and then passed to a deep geometric Q-learning algorithm. This algorithm sequentially selects a subset of features to form the final pharmacophore [38] [39] [41].

- State: The current protein-pharmacophore graph.

- Action: Incorporating an available pharmacophore feature into the graph or terminating the process.

- Reward: Based on the virtual screening performance (e.g., F1 score) of the pharmacophore on benchmark datasets like DUD-E [38].

- Network: Uses an SE(3)-equivariant neural network as the Q-value function, ensuring predictions are invariant to rotations and translations of the protein structure [38] [39].

The following diagram illustrates the complete PharmRL workflow from protein structure input to final pharmacophore query.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

1. Problem: The CNN identifies pharmacophore features in sterically occluded or physically implausible locations.

- Cause: The initial CNN model may not have been sufficiently trained to recognize the spatial constraints of the protein binding site, leading to false positive predictions.

- Solution:

- Employ Adversarial Retraining: As described in the core methodology, regenerate adversarial samples for your specific protein target [38] [39].

- Procedure:

- Discretize the binding site at a 0.5 Å resolution.

- Run the CNN on every grid point.

- Label predictions as negative if they are too close to protein atoms (e.g., within van der Waals radius).

- Also label predictions as negative if the complementary functional group on the protein is beyond a defined distance threshold (e.g., a Hydrogen Acceptor prediction >4 Å from any protein Hydrogen Donor group). Refer to thresholds in the original publication [38].

- Add these adversarial samples to your training data and fine-tune the CNN.

2. Problem: The reinforcement learning agent fails to converge on a meaningful pharmacophore, resulting in poor virtual screening performance.

- Causes and Solutions:

- Cause A: Sparse Reward Signal. This is a common challenge in RL for drug discovery. If only a tiny fraction of generated pharmacophores yield a high reward (good enrichment), the agent struggles to learn [42].

- Solution A:

- Reward Shaping: Modify the reward function to provide intermediate, guiding rewards instead of a single reward only upon pharmacophore completion [42].

- Experience Replay: Maintain a buffer of "good" past pharmacophore states and actions. During training, sample from this buffer to reinforce successful strategies and stabilize learning [42].

- Cause B: The state representation for the Q-network is inadequate.

- Solution B: Ensure the geometric graph (protein-pharmacophore) used as the state includes all relevant spatial and chemical information, such as feature types, coordinates, and distances to key protein atoms [38].

3. Problem: The generated pharmacophore retrieves too many false positives (decoys) during virtual screening on the DUD-E dataset.

- Cause: The selected feature set may be too common or lack the necessary spatial specificity to discriminate true actives from decoys.

- Solution:

- Feature Weight Optimization: While PharmRL selects features, the importance (weight) of each feature can be further optimized. Use a separate optimization loop (e.g., Bayesian optimization) on the feature weights post-elucidation.

- Tolerance Radius Adjustment: Reduce the tolerance radius for feature matching in Pharmit (default is 1 Å). A stricter tolerance demands a more precise geometric fit from screened molecules [38].

- Add Exclusion Volumes: Manually add exclusion spheres to the pharmacophore query in Pharmit to define regions sterically forbidden by the protein, which can significantly reduce false positives [43] [44].