Advanced Real-Time PCR Protocols for Circulating Tumor DNA: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications in Precision Oncology

This comprehensive review details the pivotal role of real-time PCR technologies, particularly digital PCR (dPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), in the analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) for cancer...

Advanced Real-Time PCR Protocols for Circulating Tumor DNA: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications in Precision Oncology

Abstract

This comprehensive review details the pivotal role of real-time PCR technologies, particularly digital PCR (dPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), in the analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) for cancer research and drug development. It covers foundational principles of ctDNA biology, advanced methodological protocols for ultra-sensitive detection, and strategies for troubleshooting pre-analytical and analytical challenges. The article provides a critical comparison with next-generation sequencing (NGS) and validates ctDNA as a biomarker for treatment monitoring, minimal residual disease (MRD) detection, and early therapeutic response assessment in clinical trials. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource offers practical insights for implementing robust, reproducible ctDNA PCR assays that meet the evolving demands of precision oncology.

Understanding ctDNA Biology and the Central Role of Real-Time PCR in Liquid Biopsy

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) refers to the fraction of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in the bloodstream that originates from tumor cells. As a minimally invasive biomarker, ctDNA carries tumor-specific genetic and epigenetic alterations that reflect the entire tumor genome, enabling real-time monitoring of cancer dynamics [1] [2]. The analysis of ctDNA has emerged as a cornerstone of liquid biopsy, providing critical insights for precision oncology through applications in treatment selection, response monitoring, and detection of minimal residual disease (MRD) [1] [3]. Understanding the biological foundations of ctDNA—including its release mechanisms, structural characteristics, and clearance dynamics—is essential for developing robust real-time PCR protocols and other detection methodologies that accurately capture tumor burden and evolution.

Biological Mechanisms of ctDNA Release

Tumor cells release DNA fragments into the circulation through multiple distinct pathways, which can be broadly categorized into passive release (through cell death) and active secretion. The specific mechanism of release significantly influences the structural properties of the resulting ctDNA, including its fragment size and integrity [4] [2] [5].

Passive Release Mechanisms

Apoptosis: Programmed cell death serves as a primary source of ctDNA, particularly through the caspase-dependent cleavage of DNA [4] [2]. During apoptosis, caspase-activated DNase (CAD) and other nucleases systematically cleave DNA at internucleosomal regions, resulting in DNA fragments that are wrapped around nucleosomal structures [4]. This process generates characteristic short DNA fragments of approximately 167 base pairs (bp), which correspond to the length of DNA protected by a single nucleosome core (147 bp) plus linker DNA [4] [2]. These fragments are typically packaged into apoptotic bodies and subsequently cleared by phagocytosis before being released into circulation as soluble debris [4].

Necrosis: In contrast to apoptosis, necrosis represents an unprogrammed form of cell death resulting from pathological conditions such as hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, or therapeutic injury [4] [2]. This process involves uncontrolled release of cellular contents due to plasma membrane rupture, leading to the liberation of larger, more heterogeneous DNA fragments that can extend to many kilobase pairs [4] [2]. However, these large fragments are often subjected to further degradation by circulating nucleases and phagocytic activity, resulting in a mixture of fragment sizes in circulation [4] [2].

Active Secretion Mechanisms

Beyond cell death pathways, viable tumor cells can actively release DNA through extracellular vesicles (EVs) [2]. This secretion represents a regulated communication mechanism rather than a consequence of cellular demise. Different EV subtypes contribute variably to this process:

- Exosomes (30-150 nm diameter) and microvesicles (100-1000 nm diameter) can carry tumor-derived DNA [2].

- Studies have identified DNA within EVs isolated from cancer patients, including fragments containing mutations in key oncogenes such as KRAS and TP53 [2].

- The DNA associated with larger vesicles (e.g., microvesicles, apoptotic bodies) appears enriched with smaller fragments (<200 bp), while nanoscale EVs may offer superior mutation detection capabilities in some early-stage cancers [2].

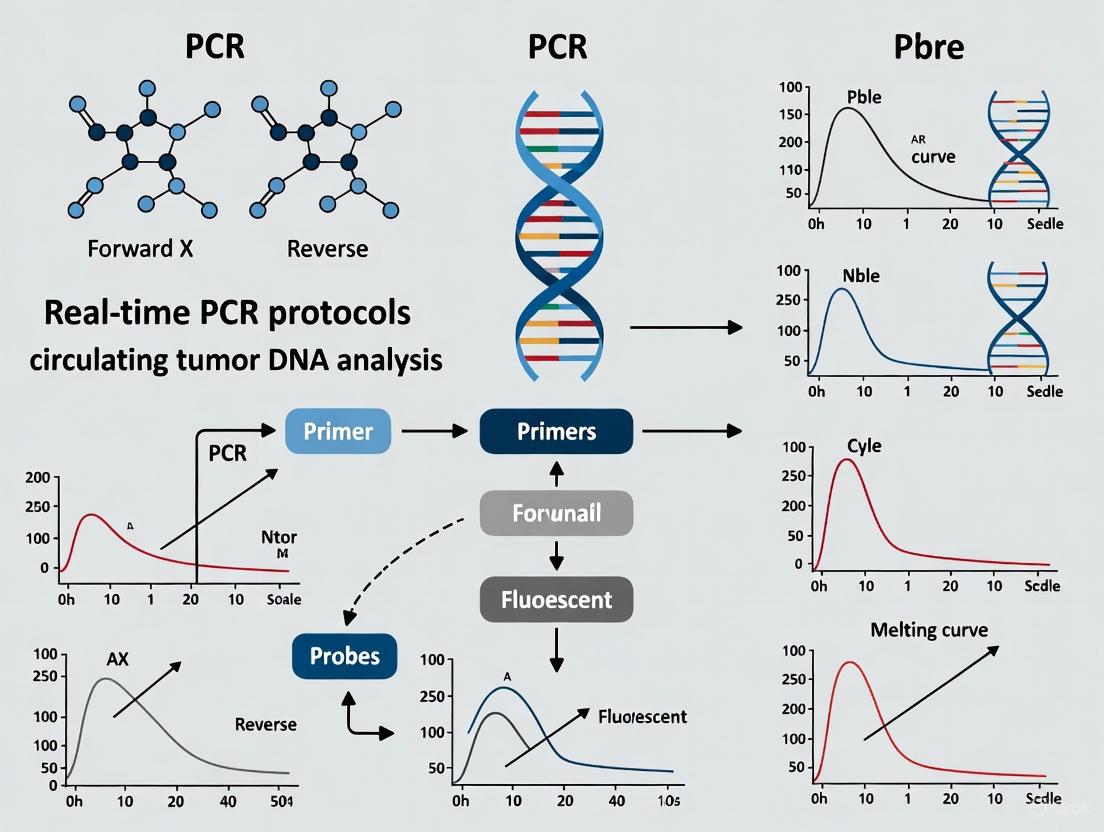

The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms of ctDNA release and their characteristic fragment profiles:

Figure 1: ctDNA Release Mechanisms and Resulting Fragment Characteristics. Tumor cells release DNA through passive mechanisms (apoptosis and necrosis) and active secretion via extracellular vesicles, each generating distinct fragment size profiles.

Characteristics and Properties of ctDNA

The mechanism of release directly influences the physical and molecular properties of ctDNA, which has important implications for detection methodology selection and assay design.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ctDNA by Release Mechanism

| Release Mechanism | Primary Fragment Sizes | DNA Integrity | Distinguishing Features | Contribution to Total ctDNA Pool |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | ~167 bp (mononucleosomal) with ladder-like pattern | Low integrity; systematic fragmentation | Nucleosome-protected ends; enriched in tumor-derived alterations | Major contributor |

| Necrosis | >200 bp to many kilobases; heterogeneous | Higher integrity; random fragmentation | Longer fragments; may reflect advanced disease or treatment effect | Variable; increased in aggressive tumors |

| Active Secretion | Variable; associated with vesicle size | Protected within lipid bilayers | Mutation-containing DNA in exosomes and microvesicles | Less characterized; potentially significant |

Beyond fragment size, ctDNA possesses several distinguishing biological features:

- Nucleosome Footprints: ctDNA fragments often retain nucleosomal patterning, which protects them from nuclease digestion and informs tissue of origin [4] [2].

- Preferred End Motifs: The cleavage of ctDNA is a non-random process, with certain genomic locations serving as preferential ends [2]. Cancer patients demonstrate greater end motif diversity, which can potentially enhance diagnostic performance [2].

- Fragmentation Patterns: ctDNA exhibits a higher fragmentation pattern compared to non-tumor cfDNA, with shorter fragments (<100 bp) potentially enriched for tumor-derived genomic alterations [2].

Experimental Approaches for ctDNA Analysis

The analysis of ctDNA requires highly sensitive methodologies capable of detecting rare mutant molecules against a background of wild-type DNA, with concentrations that can be below 0.1% of total cfDNA in early-stage disease or MRD settings [3].

Detection Technologies

PCR-based methods, including quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR), offer sensitive detection of known mutations with rapid turnaround times [1] [6]. These techniques are particularly valuable for tracking specific mutations identified through prior tumor tissue testing (tumor-informed approach) [1] [6]. Digital PCR platforms partition samples into thousands of individual reactions, enabling absolute quantification of mutant alleles without the need for standard curves [1].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides a more comprehensive approach for ctDNA analysis, enabling the assessment of multiple genomic alterations simultaneously [1] [3]. Both targeted panels and whole-exome/whole-genome sequencing approaches have been developed, with error-correction methods such as unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) essential for distinguishing true low-frequency variants from sequencing artifacts [1]. Recent technological advances include:

- Structural variant (SV)-based assays that identify tumor-specific rearrangements with high specificity [3].

- Phased variant approaches that target multiple single-nucleotide variants on the same DNA fragment to improve sensitivity [3].

- Fragmentomic analyses that leverage size selection and fragmentation patterns to enrich ctDNA fraction [3].

Pre-analytical Considerations

The reliability of ctDNA analysis depends heavily on appropriate sample collection, processing, and storage:

- Blood Collection: Plasma is preferred over serum for ctDNA analysis due to reduced background DNA from clotting [6].

- Sample Processing: Rapid separation of plasma from blood cells (within 2-6 hours of collection) prevents dilution of ctDNA by genomic DNA from lysed leukocytes [6].

- DNA Extraction: Methods optimized for short-fragment recovery improve ctDNA yield [6] [3].

- Fragment Size Selection: Enrichment of shorter DNA fragments (90-150 bp) can significantly increase the mutant allele fraction by excluding longer wild-type DNA [3].

The following workflow diagram outlines key steps in ctDNA analysis from sample collection to detection:

Figure 2: ctDNA Analysis Workflow. The process from sample collection to data analysis, highlighting critical steps that impact assay performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful ctDNA research requires carefully selected reagents and methodologies optimized for working with low-abundance, fragmented DNA.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ctDNA Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilizes nucleated blood cells to prevent genomic DNA contamination | Critical for extended transport or storage; maintains sample integrity |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of cfDNA from plasma | Select kits optimized for short-fragment recovery; silica membrane or magnetic bead-based |

| DNA Quantification Assays | Measure cfDNA concentration and quality | Fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) preferred over UV spectrophotometry |

| PCR Reagents | Amplification of target sequences | Use of high-fidelity polymerases with low error rates essential |

| Digital PCR Master Mixes | Partitioned amplification for absolute quantification | Enables detection down to 0.001% VAF; requires specialized instrumentation |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Incorporation of UMIs critical for error correction; size selection enhances sensitivity |

| Targeted Capture Panels | Enrichment of cancer-relevant genes | Commercially available or custom-designed; should cover relevant mutational hotspots |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Variant calling and interpretation | Error-suppression algorithms; fragmentomic analysis capabilities |

Clinical Applications and Research Implications

The biological characteristics of ctDNA directly inform its clinical applications in oncology. The short half-life of ctDNA (estimated between 16 minutes to several hours) enables real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics and treatment response [1]. Key applications include:

Treatment Response Monitoring: Changes in ctDNA levels often precede radiographic evidence of response or progression [1] [3] [7]. Molecular response assessments using ctDNA have demonstrated utility across multiple cancer types, with clearance of ctDNA after treatment initiation correlating with improved outcomes [7]. Quantitative metrics such as variant allele frequency (VAF) dynamics provide sensitive measures of therapeutic efficacy [7].

Minimal Residual Disease Detection: The high sensitivity of modern ctDNA assays enables identification of MRD following curative-intent treatment [1] [6] [3]. Tumor-informed approaches that track patient-specific mutations achieve the highest sensitivity for MRD detection, with ctDNA positivity post-treatment strongly predicting future recurrence [6] [3].

Therapy Selection and Resistance Monitoring: ctDNA profiling can identify targetable mutations and emerging resistance mechanisms without the need for repeated tissue biopsies [1] [3]. For example, in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer, ctDNA monitoring enables detection of T790M resistance mutations that guide subsequent therapy selection [3].

Understanding the origins and characteristics of ctDNA through apoptosis, necrosis, and active release mechanisms provides the fundamental biological context necessary for developing and optimizing real-time PCR protocols and other detection methodologies. This knowledge enables researchers to select appropriate pre-analytical methods, design assays with optimal sensitivity and specificity, and accurately interpret experimental results in the context of cancer biology and clinical management.

The analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has emerged as a transformative paradigm in precision oncology, enabling real-time, noninvasive assessment of tumor burden, genetic heterogeneity, and therapeutic response [3]. As a subset of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) derived from tumor tissue, ctDNA carries tumor-specific genetic alterations that provide a molecular snapshot of the cancer's dynamic genomic landscape [8]. However, the reliable detection of ctDNA faces three fundamental analytical challenges that constrain its clinical utility, particularly in early-stage disease and minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring [3] [9].

The first challenge, low abundance, stems from the fact that ctDNA often constitutes less than 0.1% of the total circulating cell-free DNA, creating a significant detection hurdle that demands exceptional analytical sensitivity [3]. In early-stage tumors, the concentration can be vanishingly low—sometimes fewer than 1-100 copies per milliliter of plasma—posing substantial technical challenges for detection systems [9]. The second challenge, short half-life, reflects the rapid clearance of ctDNA from circulation, with estimates ranging from 16 minutes to several hours [1]. This transient presence necessitates careful timing of sample collection and rapid processing to avoid pre-analytical degradation. The third challenge, background wild-type DNA, represents the overwhelming majority of cfDNA derived from non-tumor sources, primarily hematopoietic cells undergoing physiological apoptosis [9] [1]. This background creates a signal-to-noise problem where rare mutant ctDNA fragments must be distinguished from a vast excess of wild-type DNA, requiring exceptional specificity in detection methods.

These interconnected challenges are particularly pronounced in clinical scenarios where ctDNA detection would be most impactful: early cancer detection, assessment of MRD following curative-intent therapy, and early identification of molecular recurrence [3]. This technical guide examines these analytical barriers within the context of real-time PCR protocols and emerging solutions, providing a framework for optimizing ctDNA research in oncology applications.

Technical Analysis of Core Challenges

Challenge 1: Low Abundance of ctDNA

The low fractional abundance of ctDNA represents perhaps the most significant technical hurdle in liquid biopsy applications. Tumor-derived DNA typically constitutes only 0.025-2.5% of total circulating cell-free DNA, with this proportion influenced by tumor biology, disease burden, and treatment-related factors [9]. In practical terms, this means that detection methods must identify a handful of mutant DNA molecules among tens of thousands of wild-type fragments, pushing analytical systems to their limits of detection [3].

The biological basis for low ctDNA abundance is multifactorial. In early-stage tumors, only a tiny fraction of cells undergo apoptosis and shed DNA into circulation [9]. Additionally, ctDNA release is influenced by factors such as tumor vascularity, with ctDNA being more frequently detected in tumors with vascular invasion [9]. The relationship between tumor burden and ctDNA levels is not linear, creating particular difficulties in detecting minimal residual disease where tumor mass may be below current detection thresholds [9].

Table 1: Factors Influencing ctDNA Abundance

| Factor Category | Specific Factors | Impact on ctDNA Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor-Related Factors | Tumor stage and size | Higher stages and larger tumors correlate with increased ctDNA |

| Tumor vascularity | Vascular invasion increases ctDNA release | |

| Tumor location | Anatomical site influences shedding rates | |

| Cellular turnover rate | Higher apoptosis rates increase ctDNA | |

| Patient-Related Factors | Body mass index | Affects background cfDNA levels |

| Renal function | Impacts clearance of cfDNA | |

| Inflammatory conditions | Increase background wild-type cfDNA | |

| Circadian rhythms | ctDNA levels may fluctuate diurnally | |

| Treatment-Related Factors | Radiotherapy | Can transiently increase ctDNA release |

| Chemotherapy | May initially increase then decrease ctDNA | |

| Surgical resection | Rapidly decreases ctDNA post-procedure |

Challenge 2: Short Half-Life of ctDNA

The transient nature of ctDNA in circulation presents significant challenges for sample timing, collection, and processing. Current evidence suggests a half-life ranging from 16 minutes to several hours, significantly shorter than many protein biomarkers traditionally used in oncology [1]. This rapid turnover means that ctDNA levels provide a near real-time snapshot of tumor dynamics but also necessitates careful protocol standardization to avoid pre-analytical degradation.

The clearance mechanisms for ctDNA involve both enzymatic degradation by circulating nucleases and phagocytic uptake by liver macrophages [9]. This rapid elimination contributes to the dynamic range of ctDNA measurements, enabling rapid assessment of treatment response, but also creates vulnerabilities in the pre-analytical phase where delays in processing can profoundly impact results.

Experimental approaches to modulate ctDNA half-life have shown promise in animal models, where interfering with liver macrophages and circulating nucleases can slow physiological ctDNA decay [9]. However, these interventions remain primarily in the research domain and are not yet applicable to clinical practice.

Challenge 3: Background Wild-Type DNA Interference

The presence of abundant wild-type DNA constitutes a significant source of background noise in ctDNA analysis. In healthy individuals and cancer patients alike, the majority of cfDNA originates from hematopoietic cells through physiological apoptosis [1]. This wild-type DNA creates a dilution effect where mutant alleles are present at very low variant allele frequencies (VAF), often below 0.1% in early-stage cancers and MRD settings [3].

The wild-type background not only dilutes the signal but can also introduce analytical artifacts during amplification. In PCR-based methods, the amplification of wild-type sequences can preferentially consume reagents, potentially limiting the amplification of rare mutant templates. Additionally, errors introduced during early amplification cycles can be perpetuated and mistaken for true variants, creating false positives unless robust error-correction methods are implemented.

Table 2: Sources and Characteristics of Background Wild-Type DNA

| Source of Wild-Type DNA | Contribution to Total cfDNA | Factors Increasing Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic Cells | Primary source (≥90% in many cases) | Hemolysis during blood draw, extended tourniquet use |

| Other Normal Tissues | Variable based on physiological state | Physical exercise, tissue trauma, inflammation |

| Clonal Hematopoiesis | Variable (increases with age) | Advanced age, smoking history |

| Post-Surgical Release | Transiently increased | Recent surgical procedures, tissue injury |

Advanced Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Ultrasensitive Detection Technologies

Structural Variant-Based ctDNA Assays

Next-generation sequencing assays that focus on somatic structural variants (SVs) rather than single nucleotide variants (SNVs) can mitigate many challenges associated with low VAF detection [3]. SV-based assays identify tumor-specific chromosomal rearrangements with breakpoint sequences unique to the tumor, effectively eliminating concerns about sequencing artifacts affecting SNV calls [3]. These assays can employ multiplexed PCR panels or hybrid-capture probes personalized to individual breakpoints, achieving parts-per-million sensitivity with tumor specificity, as normal cells lack these rearrangement combinations [3].

Experimental Protocol: SV-Based ctDNA Detection

- Tumor Whole Genome Sequencing: Perform 30-60x WGS on tumor tissue and matched normal DNA to identify tumor-specific structural variants.

- Breakpoint Prioritization: Select 10-20 rearrangements with balanced allele frequencies in tumor tissue.

- Probe Design: Design hybrid-capture probes or PCR primers spanning breakpoint junctions.

- Library Preparation: Extract cfDNA from patient plasma and create sequencing libraries with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs).

- Target Enrichment: Enrich for target regions using custom probes.

- Deep Sequencing: Sequence to high coverage (≥10,000x) to detect rare ctDNA molecules.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map reads to reference genome, identify chimeric reads spanning breakpoints, and quantify tumor-specific molecules using UMI groups.

In early-stage breast cancer, this approach detected ctDNA in 96% (91/95) of participants at baseline with a median VAF of 0.15% (range: 0.0011%-38.7%), with 10% of cases having VAF <0.01% [3].

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Electrochemical Sensors

Bioelectronic sensors utilize the high surface area and conductive properties of nanomaterials to transduce DNA-binding events into recordable electrical signals, achieving attomolar sensitivity [3]. Magnetic nanoparticles coated with gold and conjugated with complementary DNA probes can capture and enrich target ctDNA fragments in proximity to electrode surfaces, enabling detection within 20 minutes [3]. Graphene or molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) facilitates label-free sensing methods where ctDNA hybridization is detected through impedance changes or current-voltage characteristics [3].

Experimental Protocol: Magnetic Nano-Electrode System

- Nanoparticle Preparation: Synthesize superparamagnetic Fe₃O₄–Au core–shell particles (10-15 nm diameter).

- Probe Conjugation: Covalently link thiol-modified DNA capture probes to gold surfaces.

- Sample Incubation: Mix nanoparticle probes with plasma cfDNA for 15 minutes with agitation.

- Magnetic Separation: Concentrate nanoparticle-cfDNA complexes using magnetic fields.

- Electrochemical Readout: Transfer complexes to electrode surface and measure current-voltage characteristics.

- Signal Amplification: Apply enzymatic or nanomaterial-based signal amplification if needed.

This approach can achieve detection limits of three attomolar with a signal-to-noise ratio within 7 minutes of PCR amplification [3].

Pre-Analytical Optimization Strategies

Blood Collection and Processing Protocols

Standardized blood collection and processing are critical for reliable ctDNA analysis. Conventional EDTA tubes require processing within 2-6 hours at 4°C to prevent leukocyte lysis and release of genomic DNA [9]. Commercial blood collection tubes containing cell-stabilizing preservatives (e.g., Streck cfDNA, PAXgene Blood ccfDNA) allow for storage and transportation for up to 7 days at room temperature by preventing leukocyte degradation [9].

Experimental Protocol: Optimal Blood Collection and Processing

- Blood Draw: Collect 20-30 mL blood using butterfly needles, avoiding excessively thin needles and prolonged tourniquet use.

- Tube Selection: Use cfDNA-stabilizing tubes for studies requiring shipment or delayed processing.

- Centrifugation: Perform two-step centrifugation:

- First step: 380-3,000 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature

- Second step: 12,000-20,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C

- Plasma Storage: Aliquot plasma and store at -80°C (stable for 10 years for mutation detection; 9 months for quantitative analysis).

- DNA Extraction: Use silica membrane-based kits (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit) for higher yields compared to magnetic bead methods.

Fragment Size Selection

Tumor-derived cfDNA typically fragments to lengths of 90-150 base pairs, while non-tumor cfDNA tends to be longer [3]. Utilizing bead-based or enzymatic size selection to enrich for shorter fragments can increase the fractional abundance of ctDNA in sequencing libraries by several folds [3]. This approach enhances the detection yield of low-frequency variants and can reduce the required sequencing depth for MRD detection, improving cost-effectiveness [3].

Bioinformatic Enhancement Strategies

Error suppression through bioinformatic methods is essential for distinguishing true low-frequency variants from technical artifacts. Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) tagged onto DNA fragments before PCR amplification enable consensus sequencing to filter out errors introduced during amplification [1]. Advanced methods like Duplex Sequencing tag and sequence both strands of DNA duplexes, allowing true mutations to be identified when present in the same position on both strands [1]. Recent innovations such as CODEC (Concatenating Original Duplex for Error Correction) achieve 1000-fold higher accuracy than conventional NGS while using up to 100-fold fewer reads than duplex sequencing [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for ctDNA Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Streck cfDNA BCT, PAXgene Blood ccfDNA Tube | Cellular stabilization during transport | Enable room temperature storage for ≤7 days |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, Cobas ccfDNA Sample Preparation Kit | Isolation of high-quality cfDNA | Silica-membrane methods yield more ctDNA than magnetic beads |

| Library Preparation | KAPA HyperPrep, ThruPLEX Plasma-Seq | Sequencing library construction | Incorporate UMIs for error correction |

| Target Enrichment | IDT xGen Lockdown Probes, Twist Custom Panels | Hybrid-capture-based target enrichment | Enable focused sequencing on relevant regions |

| qPCR/dPCR Master Mixes | ddPCR Supermix, TaqMan Advanced miRNA cDNA | Absolute quantification of mutant alleles | Digital PCR provides single-molecule sensitivity |

| Size Selection Beads | AMPure XP, Circulomics SRE | Enrichment of short cfDNA fragments | Improve tumor fraction by selecting 90-150 bp fragments |

The analytical challenges of low abundance, short half-life, and background wild-type DNA in ctDNA analysis continue to drive innovation in detection technologies and methodological approaches. Emerging strategies include stimulation of ctDNA release through external means such as localized irradiation or ultrasound, which can transiently increase ctDNA concentration 6-24 hours post-procedure [9]. Additionally, interference with physiological clearance mechanisms to prolong ctDNA half-life shows promise in animal models, though clinical applications remain exploratory [9].

The future of ctDNA analysis will likely involve multimodal approaches that combine mutation detection with complementary analytes such as methylation patterns and fragmentomics. Tumor-agnostic hypermethylated gene promoter panels can detect and quantify tumor development in patients with early-stage cancer by analyzing epigenetic modifications in cfDNA [3]. The combination of mutations and methylation signatures in cfDNA may form the foundation for future pan-cancer screening initiatives [3].

For the research community, addressing the current challenges requires continued focus on pre-analytical standardization, analytical validation, and bioinformatic sophistication. As these technical hurdles are overcome, ctDNA analysis promises to become an increasingly powerful tool for precision oncology, enabling earlier detection, more sensitive monitoring of treatment response, and improved management of cancer patients across the disease spectrum.

Diagrams above illustrate the integrated workflow for ctDNA analysis (top) and the relationship between key challenges and technological solutions (bottom).

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents a paradigm shift in nucleic acid quantification, moving beyond the relative measurements of quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) to provide absolute quantification with single-molecule sensitivity. This transformative technology partitions a sample into thousands of individual reactions, enabling precise enumeration of target molecules through binary endpoint detection and Poisson statistics. Within circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) research, dPCR's exceptional sensitivity for detecting rare mutations in a background of wild-type DNA has revolutionized liquid biopsy applications, including minimal residual disease monitoring, treatment response assessment, and resistance mutation tracking. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, methodological frameworks, and cutting-edge applications of dPCR that are advancing precision oncology.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR), invented by Kary Mullis in 1983, revolutionized molecular biology by enabling exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences [10]. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) advanced this technology by allowing researchers to monitor amplification throughout the reaction cycle using fluorescent probes, establishing itself as the gold standard for nucleic acid quantification [11]. However, qPCR possesses significant limitations: it requires standard curves for quantification, lacks sensitivity for detecting very rare mutations, and is susceptible to amplification efficiency variations between samples [12] [11].

Digital PCR emerged to address these limitations, with the fundamental concept first described in 1988 and the term "digital PCR" formally introduced in 1999 [12]. The technology leverages sample partitioning, endpoint fluorescence detection, and Poisson statistics to achieve absolute quantification without standard curves [10] [12]. This approach has proven particularly valuable in ctDNA research, where detecting rare tumor-derived mutations in circulation requires exceptional sensitivity to identify mutant allele frequencies often below 0.1% amid abundant wild-type DNA [1] [3].

Fundamental Principles of Digital PCR

Core Technological Framework

The fundamental innovation of dPCR lies in its partitioning strategy. A standard PCR reaction mixture containing template DNA, primers, probes, nucleotides, and enzymes is divided into thousands to millions of individual microreactions [12]. These partitions can be created through various physical means including microfluidic chambers, droplet emulsions, or nanoplates [10] [12]. Each partition acts as an independent PCR microreactor where amplification occurs in isolation from other partitions.

Following thermal cycling, each partition is analyzed for fluorescence. Partitions containing the target sequence emit fluorescence (recorded as "1"), while those without the target remain dark (recorded as "0") [12]. This binary detection system gives the technology its "digital" name, analogous to digital computing's binary code [12]. The ratio of positive to total partitions enables absolute quantification of the target nucleic acid through statistical analysis.

Statistical Foundation: Poisson Distribution and Quantification Accuracy

The random distribution of DNA molecules across partitions follows Poisson statistics, which forms the mathematical foundation for dPCR quantification [10] [11]. According to Poisson distribution, the probability of a partition containing k target molecules is given by:

P(k) = (λ^k · e^(-λ)) / k!

Where λ represents the average number of target molecules per partition [11]. For dPCR analysis, the most critical case is k=0 (the fraction of empty partitions), leading to the simplified equation:

λ = -ln(1 - p)

Where p is the proportion of positive partitions [11]. This relationship allows calculation of the absolute target concentration without reference to standards.

The accuracy of dPCR quantification depends heavily on the number of partitions analyzed and their occupancy rate. Precision is optimal when approximately 20% of partitions are positive (λ = 1.6), with accuracy improving as the total number of partitions increases [11]. This statistical framework defines both the dynamic range and detection limits of dPCR systems, with higher partition counts enabling more sensitive detection of rare targets—a critical advantage for ctDNA analysis where mutant allele frequencies can be extremely low [10] [12].

Comparative Analysis: dPCR vs. qPCR

digital PCR vs. Quantitative PCR: Key Technical Differences

| Parameter | Digital PCR (dPCR) | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Absolute quantification via Poisson statistics | Relative quantification requiring standard curve |

| Detection Principle | End-point fluorescence detection | Real-time fluorescence monitoring during exponential phase |

| Sensitivity | Higher sensitivity for rare alleles (<0.1% VAF) | Limited sensitivity for rare mutations (typically >1% VAF) |

| Precision | Superior precision due to partitioning and binary detection | Moderate precision influenced by amplification efficiency |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Higher tolerance due to sample partitioning | More susceptible to PCR inhibitors |

| Dynamic Range | Limited by number of partitions | Broader dynamic range |

| Throughput | Moderate to high | High |

| Cost Considerations | Higher per sample, but becoming more competitive | Established, cost-effective for high-volume testing |

VAF: Variant Allele Frequency [12] [11]

dPCR Workflow and Experimental Design

Core Workflow Implementation

The dPCR process follows a standardized workflow that can be divided into three key phases: preparation, amplification, and analysis [12]. The preparation phase involves assembling the PCR reaction mix and loading it into the dPCR instrument, which then automatically partitions the sample. The partitioning mechanism varies by platform, with common approaches including droplet-based systems (creating water-in-oil emulsions), chip-based arrays (with etched microwells), and nanoplate-based technologies [10] [12].

During the amplification phase, the partitioned sample undergoes conventional PCR thermal cycling. Each partition functions as an individual reaction vessel, with target molecules amplified independently. Following amplification, the system detects fluorescence in each partition, with positive partitions indicating the presence of the target sequence [12]. The final analytical phase applies Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration of the target molecule in the original sample based on the proportion of positive partitions [10] [12].

Research Reagent Solutions for ctDNA Analysis

Essential Research Reagents for dPCR-based ctDNA Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Function in dPCR Workflow | Application Notes for ctDNA |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes with Stabilizers (e.g., cfDNA BCT tubes) | Preserves blood sample integrity, prevents genomic DNA release from blood cells | Critical for accurate ctDNA analysis; enables room temperature transport for up to 7 days [13] |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | Isolates cell-free DNA from plasma | Size-selection methods can enrich for ctDNA fragments (90-150 bp) over longer hematopoietic DNA [3] |

| dPCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, nucleotides, buffers for amplification | Should include UDI technology to reduce cross-contamination; inhibitor-resistant formulations preferred [12] |

| Mutation-Specific Assays | Detects tumor-specific mutations | Tumor-informed assays (based on prior sequencing) increase sensitivity; multiplex assays enable parallel detection [1] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tags individual DNA molecules to distinguish true mutations from PCR errors | Essential for error correction in rare mutation detection; reduces false positives [1] |

| Microfluidic Partitioning Oil/Reagents | Creates stable emulsion for droplet-based dPCR | Partition stability critical for accurate quantification; commercial formulations provide optimal consistency [10] |

dPCR Applications in ctDNA Research

Monitoring Treatment Response and Resistance

The short half-life of ctDNA (approximately 16 minutes to several hours) makes it an ideal biomarker for real-time monitoring of treatment response [1]. dPCR enables serial assessment of mutation-specific ctDNA levels during therapy, with declining concentrations indicating positive treatment response and rising levels suggesting therapeutic resistance [1] [3]. Studies across multiple cancer types have demonstrated that ctDNA changes often precede radiographic evidence of response or progression by several weeks [3]. In EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer, for example, dPCR can detect emerging T790M resistance mutations, guiding timely switches to third-generation EGFR inhibitors without repeated tissue biopsies [3].

Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Detection

The exceptional sensitivity of dPCR enables detection of molecular residual disease following curative-intent surgery or radiation therapy [1] [14]. MRD assessment represents one of the most promising applications of dPCR in oncology, as it can identify patients at high risk of recurrence who might benefit from additional therapy, while sparing those with undetectable MRD from unnecessary treatment [14]. Clinical studies have demonstrated that ctDNA detection post-treatment predicts recurrence with high sensitivity and specificity, often providing a lead time of several months before clinical or radiographic recurrence [14]. In colorectal cancer, ctDNA-guided approaches have reduced adjuvant chemotherapy use without compromising recurrence-free survival [14].

Clinical Trial Applications and Protocol Implementation

The research applications of dPCR in ctDNA analysis are increasingly being translated into clinical trials frameworks. Ongoing studies are evaluating ctDNA-based endpoints for accelerated drug development and as potential surrogates for traditional survival endpoints [14]. The implementation of dPCR in these settings requires careful attention to pre-analytical variables, assay validation, and analytical standardization to ensure reproducible results across sites [13]. A proposed workflow for implementing dPCR in clinical research captures the comprehensive process from sample collection to clinical decision-making.

Advanced Methodologies and Future Directions

Emerging Technological Innovations

While current dPCR platforms already provide exceptional sensitivity, emerging technologies promise to further advance the field. Approaches such as Concatenating Original Duplex for Error Correction (CODEC) claim to achieve 1000-fold higher accuracy than conventional NGS while using significantly fewer reads [1]. Structural variant-based ctDNA assays that identify tumor-specific chromosomal rearrangements are achieving detection sensitivities in the parts-per-million range [3]. Nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors using graphene or molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) can detect ctDNA at attomolar concentrations within minutes, potentially enabling point-of-care applications [3]. Additionally, fragmentation pattern analysis that exploits the characteristic shorter length of ctDNA fragments (90-150 bp) compared to non-tumor cfDNA provides an orthogonal method for improving detection specificity [1] [3].

Addressing Current Limitations and Challenges

Despite its considerable advantages, dPCR faces several technical and implementation challenges. The dynamic range of dPCR is constrained by the number of partitions available in each system, potentially limiting its utility for samples with very high target concentrations [12]. Pre-analytical variables including blood collection methods, processing timelines, and plasma separation protocols can significantly impact ctDNA recovery and assay performance [13]. Standardization across platforms and laboratories remains challenging, with inter-institution harmonization efforts ongoing [13]. Additionally, the tumor-informed approach that provides maximum sensitivity requires prior knowledge of tumor-specific mutations, adding complexity to the testing workflow [1] [14].

Future developments will likely focus on increasing partition densities to enhance sensitivity and dynamic range, improving multiplexing capabilities to simultaneously monitor multiple mutations, and integrating artificial intelligence-based error suppression methods to further improve specificity [3]. As these technological advances mature, dPCR is poised to become an increasingly central tool in both cancer research and clinical oncology, enabling more precise monitoring of treatment response and disease dynamics through non-invasive liquid biopsy approaches.

Digital PCR represents a fundamental advancement in nucleic acid quantification, providing absolute measurement of target sequences with precision that surpasses traditional qPCR, particularly for rare mutation detection. Its unique partitioning approach, combined with Poisson statistical analysis, enables researchers to detect and quantify ctDNA at variant allele frequencies below 0.1%—a critical capability for advancing liquid biopsy applications in oncology. As technological innovations continue to enhance the sensitivity, multiplexing capacity, and accessibility of dPCR platforms, this methodology is establishing new paradigms for cancer monitoring, minimal residual disease detection, and real-time assessment of treatment response. The integration of dPCR into both research and clinical workflows promises to accelerate the development of more personalized, dynamic cancer management strategies based on the molecular signatures captured in circulating tumor DNA.

Liquid biopsy, a revolutionary technique in precision oncology, enables the analysis of tumor-derived components from bodily fluids such as blood. This approach provides a minimally invasive alternative to traditional tissue biopsies, offering dynamic insights into tumor biology through circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), and other biomarkers [15] [16]. The clinical adoption of liquid biopsy has transformed cancer management by facilitating real-time monitoring, capturing tumor heterogeneity, and enabling serial sampling with minimal patient risk [17]. This technical guide explores the core advantages of liquid biopsy technologies, with particular emphasis on their application within circulating tumor DNA research frameworks, providing researchers and drug development professionals with detailed methodologies and current evidence supporting their implementation.

Core Advantages of Liquid Biopsy

Real-Time Monitoring and Dynamic Prognostication

Liquid biopsy enables real-time tracking of tumor dynamics and treatment response by detecting changes in circulating biomarker levels, offering a significant advantage over traditional imaging methods.

Superior Prognostic Value: Meta-analyses demonstrate that ctDNA detection consistently predicts poorer survival outcomes across multiple cancer types. In esophageal cancer, for example, ctDNA positivity associates with significantly reduced progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) at various treatment timepoints, with hazard ratios increasing from baseline through follow-up monitoring [18].

Early Recurrence Detection: ctDNA testing can identify molecular recurrence months before radiological confirmation. A comprehensive analysis revealed that ctDNA detection anticipates clinical recurrence with an average lead time of 4.53 months (range: 0.98-11.6 months) compared to conventional imaging [18].

Therapy Response Monitoring: Dynamic changes in ctDNA levels closely reflect treatment effectiveness. In metastatic colorectal cancer, a ctDNA increase during systemic therapy strongly correlates with reduced PFS (HR: 2.44, 95% CI: 2.02-2.95) and OS (HR: 2.53, 95% CI: 2.01-3.18) [19]. Rapid ctDNA clearance following treatment initiation often indicates favorable response, while persistent detection may signal resistance [17].

Table 1: Prognostic Value of ctDNA at Different Monitoring Timepoints in Esophageal Cancer

| Timepoint | PFS Hazard Ratio | OS Hazard Ratio | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (after diagnosis, before treatment) | HR = 1.64 (95% CI: 1.30-2.07) | HR = 2.02 (95% CI: 1.36-2.99) | Identifies high-risk patients who may benefit from treatment intensification |

| After Neoadjuvant Therapy (before surgery) | HR = 3.97 (95% CI: 2.68-5.88) | HR = 3.41 (95% CI: 2.08-5.59) | Detects minimal residual disease, guides adjuvant therapy decisions |

| During Follow-up (adjuvant therapy or surveillance) | HR = 5.42 (95% CI: 3.97-7.38) | HR = 4.93 (95% CI: 3.31-7.34) | Enables early recurrence detection, allows for preemptive intervention |

Comprehensive Capture of Tumor Heterogeneity

Tumors exhibit substantial spatial and temporal heterogeneity, which traditional biopsies often fail to capture comprehensively. Liquid biopsy addresses this limitation by sampling tumor-derived components released from all tumor sites throughout the body.

Overcoming Sampling Bias: Tissue biopsies provide information only from a specific lesion and may miss molecular alterations present in metastatic sites or different regions of the primary tumor. In contrast, liquid biopsy integrates genetic material from multiple tumor sites, offering a more complete molecular profile [16].

Tracking Clonal Evolution: Serial liquid biopsies enable monitoring of tumor evolution under therapeutic pressure, including the emergence of resistance mechanisms. This capability is crucial for understanding treatment failure and guiding subsequent therapy selection [19].

Complementary Biomarker Classes: Different liquid biopsy components provide unique insights:

- CTCs: Offer intact cellular material for functional studies and protein expression analysis [15]

- ctDNA: Provides genetic information including mutations, copy number alterations, and epigenetic modifications [15]

- Extracellular Vesicles: Contain proteins, RNA species, and other macromolecules that reflect cellular states [16]

The following workflow illustrates how liquid biopsy captures global tumor heterogeneity, unlike traditional tissue biopsy:

Non-Invasive Sampling and Clinical Applications

The minimally invasive nature of liquid biopsy facilitates repeated sampling, enabling longitudinal monitoring that is not feasible with tissue biopsies due to procedural risks and patient discomfort.

Procedural Advantages: Liquid biopsy primarily uses blood draws, which are routine outpatient procedures with minimal risk, unlike surgical biopsies which may require hospitalization and carry risks of bleeding, infection, or organ injury [15] [16].

Serial Monitoring Capability: The ability to perform frequent assessments enables dynamic treatment response evaluation and early detection of resistance mechanisms. This facilitates timely intervention before clinical deterioration [17].

Diverse Clinical Applications:

- Early Cancer Detection: Identifying tumor-specific mutations in blood samples from asymptomatic individuals [15]

- Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Monitoring: Detecting molecular residual disease after curative-intent treatment [17] [13]

- Treatment Selection: Identifying actionable genomic alterations to guide targeted therapy [20]

- Clinical Trial Endpoints: Providing pharmacodynamic biomarkers for drug development [16]

Table 2: Clinical Impact of Liquid Biopsy in a Real-World Cohort (n=30 Patients)

| Clinical Decision Category | Case Examples | ctDNA Findings | Clinical Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Escalation | Stage III sigmoid cancer; Stage IV pancreatic NET | ctDNA positivity after initial therapy | Initiation or intensification of systemic treatment |

| Treatment De-escalation | Metastatic urothelial carcinoma; Oligometastatic colorectal cancer | ctDNA negativity with radiological response | Reduction or discontinuation of toxic therapies |

| Early Relapse Prediction | GE junction carcinoma; Lung adenocarcinoma | ctDNA detection during surveillance | Earlier imaging confirmation and treatment modification |

| Response Monitoring | Colorectal, endometrial, breast cancers | Persistent ctDNA negativity | Continued surveillance or maintenance therapy |

Technical Considerations for ctDNA Analysis

Pre-analytical Factors and Sample Collection

The sensitivity of ctDNA detection depends critically on proper sample collection and processing, as ctDNA typically represents less than 0.025-2.5% of total circulating cell-free DNA [13].

Blood Collection Tubes: Both conventional EDTA tubes and specialized cell-free DNA preservation tubes are used. EDTA tubes require processing within 2-6 hours at 4°C, while specialized tubes (e.g., Streck cfDNA, PAXgene) allow sample stability for up to 7 days at room temperature [13].

Recommended Blood Volume: For single-analyte liquid biopsy, 2 × 10 mL of blood is typically recommended. Larger volumes may be necessary for MRD detection, whole-genome sequencing, or multi-analyte testing [13].

Pre-analytical Variables: Physical activity, circadian rhythms, and concurrent conditions (inflammation, surgery) can influence ctDNA levels. Surgical trauma transiently increases total cell-free DNA for several weeks, potentially confounding interpretation [13].

Analytical Methods and Sensitivity Enhancement

Advanced molecular techniques have dramatically improved the sensitivity of ctDNA detection, enabling applications in minimal residual disease monitoring.

Ultra-Sensitive Detection Platforms: Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) are the primary technologies for ctDNA analysis. Recent assays like Northstar Select demonstrate a limit of detection of 0.15% variant allele frequency for single nucleotide variants and indels, with sensitive detection of copy number variations and gene fusions [20].

Approaches to Enhance Sensitivity:

- Physical Stimulation: Local tumor irradiation can induce transient apoptosis and increase ctDNA release 6-24 hours post-procedure [13]

- Technical Innovations: Modified ultra-deep NGS protocols discriminate true low-frequency mutations from sequencing artifacts [13]

- Biological Interventions: Slowing physiological ctDNA clearance by interfering with liver macrophages and circulating nucleases shows promise in preclinical models [13]

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from sample collection to clinical application in ctDNA analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Liquid Biopsy Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubes (e.g., Streck, PAXgene) | Preserves blood sample integrity during storage and transport | Enables room temperature stability for up to 7 days; prevents genomic DNA contamination from white blood cell lysis |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality cfDNA from plasma | Magnetic bead-based systems typically provide better yield and reproducibility than column-based methods |

| PCR/Sequencing Reagents | Amplification and detection of tumor-specific alterations | Digital PCR platforms (ddPCR) offer absolute quantification; NGS enables multiplexed analysis of multiple genomic regions |

| Reference Standard Materials | Assay validation and quality control | Commercially available synthetic cfDNA references with predetermined mutation frequencies enable assay calibration |

| Bioinformatic Analysis Pipelines | Variant calling and interpretation | Specialized algorithms (e.g., MuTect, VarScan2) distinguish low-frequency true variants from sequencing artifacts |

Liquid biopsy represents a paradigm shift in cancer management, offering distinct advantages through its non-invasive nature, capacity for real-time monitoring, and comprehensive capture of tumor heterogeneity. Technological advancements continue to enhance the sensitivity of ctDNA detection, expanding applications from early cancer detection to minimal residual disease monitoring. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these advantages and the associated technical considerations is essential for leveraging liquid biopsy's full potential in advancing precision oncology and improving patient outcomes.

Implementing Cutting-Edge dPCR and ddPCR Protocols for ctDNA Analysis

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), a subset of cell-free DNA derived from tumor tissue, has emerged as an essential biomarker for the real-time, noninvasive assessment of cancer burden, molecular response, and early evaluation of recurrence in precision oncology [3]. The analysis of ctDNA via liquid biopsy presents a less invasive alternative to tissue biopsy, with lower sampling bias and procedural risk [3]. However, the reliable detection of ctDNA is challenging due to its often very low concentration in blood, sometimes constituting less than 0.1% of the total circulating cell-free DNA, especially in early-stage disease and minimal residual disease (MRD) settings [3]. This technical guide details an optimized, end-to-end workflow from blood collection to data analysis, specifically framed within the context of real-time PCR protocols for ctDNA research, to achieve maximal sensitivity and reproducibility for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The entire process, from patient blood draw to the generation of a quantitative ctDNA report, involves a series of critical and sequential steps. Each stage must be rigorously controlled to preserve the integrity of the scarce ctDNA analyte and ensure the accuracy of the final result. The following diagram summarizes this optimized workflow and its key decision points.

Phase 1: Pre-Analytical Sample Processing

The pre-analytical phase is arguably the most critical for success in ctDNA analysis, as improper handling can lead to the irreversible loss of the target analyte or the introduction of artifacts that confound subsequent analysis.

Blood Collection and Plasma Separation

- Collection Tube: Collect peripheral blood using cell-stabilizing tubes (e.g., Streck, PAXgene). These tubes prevent the lysis of white blood cells and the subsequent release of genomic DNA, which would dilute the ctDNA fraction [3] [21].

- Processing Timeline: Process blood samples within 4-6 hours of draw to ensure ctDNA stability and prevent degradation [21].

- Centrifugation Protocol: A double-centrifugation method is essential to obtain platelet-poor plasma.

- First Spin: Centrifuge at 1,600 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from cellular components.

- Second Spin: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove any remaining platelets and debris.

- Storage: Aliquot the cleared plasma to avoid freeze-thaw cycles and store at -80°C until cfDNA extraction.

cfDNA Extraction and Quality Control

Extract cfDNA from plasma using a silica membrane or magnetic bead-based kit optimized for low-abundance nucleic acids. The following table outlines key quality control checkpoints and their acceptance criteria.

Table 1: Quality Control Metrics for Extracted cfDNA

| Parameter | Assessment Method | Optimal QC Range | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration | Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) | >0.5 ng/µL (from 1-4 mL plasma) | Indicates sufficient material for downstream analysis [3]. |

| Fragment Size | Bioanalyzer/TapeStation | Peak ~160-170 bp | Confirms enrichment of mononucleosomal cfDNA; tumor-derived cfDNA is often shorter [3]. |

| Purity (A260/A280) | Spectrophotometry | 1.8 - 2.0 | Suggests minimal protein or solvent contamination. |

Samples failing these QC metrics should not be advanced to library preparation, as they are likely to yield unreliable results.

Phase 2: Analytical Assay and qPCR Setup

This phase involves preparing the extracted cfDNA for amplification and setting up the highly sensitive qPCR reaction.

Library Preparation and Target Enrichment

For ctDNA detection using real-time PCR, a targeted approach is typically used.

- Library Preparation: Convert the extracted cfDNA into a sequencing library. This involves end-repair, adapter ligation, and minimal cycle amplification. Specialized library preparation methods that enrich for short fragments can significantly increase the fractional abundance of ctDNA [3].

- Target Enrichment: Use multiplexed PCR to amplify specific genomic regions harboring mutations of interest (e.g., SNVs, indels). This creates an amplicon library enriched for the targets, increasing the assay's sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants [3].

qPCR Experimental Design and Plate Setup

Quantitative PCR enables the detection and quantification of mutant alleles with a limit of detection (LOD) approaching 0.1% variant allele frequency (VAF) when using digital PCR (dPCR) technologies, which is often the basis for ultra-sensitive qPCR assays [3] [22].

- Assay Design: Design TaqMan hydrolysis probes or similar, with wild-type and mutation-specific probes.

- Reaction Composition: Optimize the reaction mix with a passive reference dye to correct for variations in master mix volume and optical anomalies, thereby improving precision [22].

- Replicates: Include both technical and biological replicates.

- Technical Replicates: A minimum of triplicate reactions per sample is recommended to account for system variation (pipetting, instrument noise) and allow for outlier detection [22].

- Biological Replicates: Multiple patient or control samples per group are required to account for true biological variation [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for setting up and running the qPCR experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for ctDNA qPCR Workflow

| Reagent / Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Stabilizing Blood Tubes | Preserves blood sample integrity post-draw. | Prevents gDNA contamination from white blood cell lysis; critical for maintaining low background [3]. |

| cfDNA Extraction Kit | Isolates and purifies cfDNA from plasma. | Select kits designed for low-input, short-fragment DNA to maximize ctDNA recovery. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer for amplification. | Use a high-fidelity, robust mix suitable for detecting rare variants. |

| Mutation-Specific Assays | Enables specific detection of target mutations. | Includes primers and probes (e.g., TaqMan) for wild-type and mutant sequences. LNA/DNA primers can enhance specificity. |

| Passive Reference Dye | Normalizes fluorescent signals. | Corrects for well-to-well volume variation and optical anomalies, improving data precision [22]. |

| Quantitative Standards | Enables absolute quantification. | A dilution series of synthetic DNA templates with known mutant allele concentrations to generate a standard curve. |

Phase 3: Data Analysis and Quality Assurance

Rigorous data analysis is required to transform raw fluorescence data into reliable, quantitative ctDNA measurements.

Quantification Methods

- Absolute Quantification: Relates the Cq value of a sample to a standard curve from known concentrations, allowing the determination of the fundamental number of target DNA molecules in a sample. This is essential for reporting ctDNA concentration in plasma [22].

- Relative Quantification: Measures the change in target quantity relative to a reference group (e.g., a housekeeping gene or wild-type allele). The ΔΔCq method is commonly used to calculate fold-changes in mutant allele frequency, though this is less common for direct ctDNA reporting.

Ensuring Precision and Statistical Significance

Precision—the random variation of repeated measurements—is critical for discriminating small, biologically significant differences in ctDNA levels [22].

- Calculate Precision Metrics:

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): A key measure of precision, calculated as (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100%. CV should be minimized, ideally below 10-15% for technical replicates [22].

- Standard Error (SE): Measures sampling error, providing boundaries for how distant the measured mean is from the true mean [22].

- Statistical Testing: To assess whether an observed fold-change in ctDNA levels between groups (e.g., pre- and post-treatment) is statistically significant, perform a t-test. A significant result (typically p < 0.05) indicates that random chance is an unlikely explanation for the observed change [22].

Table 3: Key Statistical Metrics for qPCR Data Analysis

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation in ctDNA Context |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Variation (CV%) | (SD / Mean) × 100% | Measures run-to-run and sample-to-sample reproducibility. A high CV reduces the ability to detect true changes in ctDNA levels [22]. |

| Standard Error (SE) | SD / √(n) | Indicates the confidence in the mean estimate. A smaller SE suggests the sample mean is a more reliable estimate of the true population mean [22]. |

| p-value | From t-test or ANOVA | Determines the statistical significance of observed differences in ctDNA levels between patient groups or time points. |

The optimized workflow detailed in this guide—from standardized blood collection and stringent pre-analytical processing to a meticulously controlled qPCR assay and rigorous statistical analysis—provides a robust framework for reliable ctDNA detection and quantification. As the field advances, emerging technologies like fragment-enriched library preparation, nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors, and AI-based error suppression methods promise to push sensitivity even further, potentially to attomolar concentrations [3]. Adherence to this structured protocol ensures the generation of high-quality, reproducible data, which is foundational for realizing the full potential of ctDNA analysis in cancer research, drug development, and ultimately, clinical practice.

The analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) through real-time PCR has emerged as a transformative tool in oncology research and drug development, enabling non-invasive detection of tumor-specific genetic alterations from liquid biopsies. The pre-analytical phase—encompassing sample collection, processing, storage, and preparation—represents the most vulnerable stage in the entire workflow, where improper handling can irrevocably compromise data integrity. Research indicates that pre-analytical variables contribute to up to 70% of errors in laboratory testing, underscoring the critical importance of standardized protocols for reliable ctDNA analysis. This technical guide provides comprehensive, evidence-based methodologies for mastering pre-analytical variables to ensure the accuracy, reproducibility, and sensitivity required for cutting-edge circulating tumor DNA research.

Sample Tubes: Selection and Specifications

The initial choice of blood collection tubes fundamentally influences ctDNA stability and recovery, serving as the foundational step in pre-analytical workflows. Proper selection preserves the integrity of cell-free DNA and prevents genomic DNA contamination from leukocyte lysis.

PCR Tube Specifications and Performance Characteristics

For downstream PCR amplification, tube design directly impacts thermal transfer efficiency and reaction consistency. The following table summarizes key specifications for PCR tubes and strips used in ctDNA analysis:

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of PCR Tubes for ctDNA Analysis

| Feature | Specification | Importance for ctDNA Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Polypropylene [23] [24] | Chemically inert, prevents biomolecule adsorption |

| Wall Design | Thin-walled [23] [24] | Optimizes thermal transfer for precise temperature cycling |

| Certifications | RNase-, DNase-, DNA-free [23] [24] | Precludes false positives from contaminating nucleases or DNA |

| Profile | Low-profile design [24] | Reduces dead air volume, minimizes evaporation |

| Volume Range | 5-125 µL [24] | Accommodates low-volume reactions (15 µL typical for qPCR) |

| Cap Seal | Attached flat caps or domed strip caps [23] [24] | Ensures leak-proof seal during thermal cycling |

Tube Selection Guidelines

- Thermal Conductivity: Prioritize thin-walled tubes specifically designed for optimal heat transfer in thermal cyclers to ensure uniform temperature distribution across all samples [23] [24].

- Evaporation Prevention: Select tubes with secure, leak-proof caps; for instruments without heated lids, consider a mineral oil overlay to prevent evaporation during cycling [25].

- Sample Identification: Utilize color-coded caps or strips for efficient sample tracking in high-throughput environments [23].

Centrifugation Protocols: Optimal Processing Parameters

Differential centrifugation protocols are critical for separating ctDNA from cellular components in blood samples, preventing contamination from genomic DNA released by lysed blood cells.

Blood Processing Workflow for ctDNA Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the sequential centrifugation approach for optimal plasma and ctDNA recovery:

Centrifugation Parameters

- Initial Centrifugation: Process whole blood within 2 hours of collection at 1,600-2,000 × g for 10-20 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from cellular components while minimizing cell lysis.

- Secondary Centrifugation: Transfer plasma supernatant to a new tube and centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove remaining platelets and cellular debris.

- Plasma Storage: Aliquot cleared plasma into low-protein-binding tubes and store at -80°C if cfDNA extraction cannot be performed immediately.

Storage Conditions: Maintaining Sample Integrity

Storage conditions and stability timelines significantly impact ctDNA recovery and the sensitivity of subsequent qPCR detection. Systematic evaluation of reagent stability enables workflow optimization while maintaining analytical fidelity.

DNA and Reagent Stability Parameters

Table 2: Stability of qPCR Reagents and DNA Templates for ctDNA Analysis

| Component | Storage Condition | Stability Duration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracted DNA | -20°C (short-term) [26] | Weeks to months | For long-term storage, purify and resuspend in standard buffer [26] |

| Primer-Probe Mixes | -20°C, protected from light [27] | ≥5 months with monthly freeze-thaw cycles | Aliquot to minimize freeze-thaw cycles [27] |

| Prepared qPCR Plates | 4°C [27] | 3 days before thermocycling | Maintains detection fidelity for low and high DNA copies [27] |

| Synthetic DNA Standards | -20°C with stabilizer (e.g., tRNA) [27] | ≥3 months | Aliquot to reduce freeze-thaw impacts; maintains standard curve linearity [27] |

| Whole Blood | Room temperature | Process within 2-6 hours | Use stabilizer-containing tubes if delayed processing is unavoidable |

Factors Contributing to DNA Degradation

DNA degradation profoundly impacts PCR efficiency and must be minimized throughout storage and handling:

- Temperature Fluctuations: Repeated freezing and thawing introduces strand breaks; aliquot samples to avoid more than 3-5 freeze-thaw cycles [28].

- Nuclease Contamination: Residual nucleases from inefficient purification degrade DNA; use nuclease-free consumables and include EDTA in storage buffers [28].

- Physical Shearing: Vortexing or pipetting generates hydrodynamic shear forces; gently mix by inversion and use wide-bore tips for DNA handling [28].

- Environmental Exposure: UV radiation and elevated temperatures accelerate degradation; store DNA in amber tubes at -20°C or below with consistent temperatures [28].

Experimental Protocols: Validation Methodologies

Protocol: Stability Testing of qPCR Reagents

Objective: Systematically evaluate the effects of storage conditions on qPCR reagent performance for ctDNA detection [27].

Materials:

- Validated qPCR assays (primers, probes)

- Synthetic DNA templates (gBlocks)

- QIAcuity Probe Master Mix (or equivalent)

- Low-protein-binding tubes (e.g., Corning Eppendorf tubes)

- Thermal cycler with real-time detection capability

Methodology:

- Primer-Probe Mix Stability:

- Prepare primer-probe mixes containing 7 µM each of forward and reverse primers and 1 µM TaqMan probe

- Aliquot mixes and subject to freeze-thaw cycles (monthly for 5 months)

- Store at -20°C in manual defrost freezer protected from light

- Compare Cq values and amplification efficiency monthly using synthetic DNA templates

Prepared qPCR Plate Stability:

- Prepare qPCR reactions containing master mix, primer-probe, and DNA template (4-20 copies/reaction)

- Prepare identical plates: one run immediately, another stored at 4°C for 3 days before running

- Use 8 technical replicates per condition to ensure statistical power

- Compare DNA copy estimates between plates using Wilcoxon Signed Rank test

Synthetic DNA Template Stability:

- Prepare gBlocks dilution series (1010 to 0.016 copies/µL) in tRNA stabilizer (10 ng/µL)

- Aliquot and store at -20°C for 0-3 months

- Calculate limits of detection (LOD) and limits of quantification (LOQ) using eLowQuant or equivalent software

- Assess PCR efficiency via linear regression of standard curves

Statistical Analysis:

- Use R Studio or equivalent for statistical analysis

- Test data normality with Shapiro-Wilk test and homogeneity of variance with Levene's test

- Apply non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon Signed Rank, Friedman repeated measures) for copy number comparisons

- Present data as median values with median absolute deviation error

Protocol: Assessment of DNA Degradation

Objective: Determine DNA integrity and its suitability for long-target amplification in ctDNA research [28].

Methodology:

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis:

- Prepare 1-2% agarose gel in TAE or TBE buffer with ethidium bromide or alternative stain

- Load 100-200 ng DNA alongside high molecular weight ladder

- Electrophorese at 5-6 V/cm for 45-60 minutes

- Visualize under UV transillumination

- Interpretation:

- Intact DNA: Tight band of high molecular weight with minimal smearing

- Degraded DNA: Smearing pattern with reduction in high molecular weight band intensity

- Impact on PCR: As average DNA fragment size approaches target amplicon length, PCR efficiency decreases due to reduced intact templates

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Pre-Analytical ctDNA Workflows

| Item | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Stabilized Blood Collection Tubes | Preserves cell-free DNA profile prevents leukocyte lysis during transport | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT or PAXgene Blood cDNA tubes |

| Polypropylene PCR Tubes | Reaction vessels for qPCR amplification | Thin-walled, DNase/RNase-free, 0.1-0.2 mL capacity [23] [24] |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for PCR amplification | Thermostable, 5'→3' polymerase activity, supplied with optimized buffer [25] |

| dNTPs | Building blocks for DNA synthesis | Purified, nuclease-free, neutral pH, quality verified for PCR |

| Primer-Probe Mixes | Target-specific amplification and detection | HPLC-purified, sequence-verified, optimized concentrations [27] [29] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides optimized reaction components | Contains buffer, dNTPs, polymerase, reference dye (e.g., ROX) [27] [29] |

| DNA Quantification Standards | Standard curve generation for absolute quantification | Synthetic DNA (gBlocks) with target sequences, suspended in stabilizer [27] |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Diluent for reagents and reactions | Molecular biology grade, certified free of nucleases and contaminants |

Mastering pre-analytical variables in ctDNA research requires meticulous attention to sample tube selection, centrifugation parameters, and storage conditions. The protocols and stability data presented herein provide evidence-based frameworks for optimizing liquid biopsy workflows, enabling researchers to maintain the integrity of precious samples throughout processing and storage. Implementation of these standardized approaches ensures the reliability, reproducibility, and sensitivity required for robust circulating tumor DNA detection and quantification in both basic research and drug development contexts.

The analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has emerged as a pivotal tool in precision oncology, enabling non-invasive detection of oncogenic mutations that drive cancer progression. This technical guide focuses on assay design strategies for five critical oncogenic targets—EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and ESR1—within the context of real-time PCR protocols for ctDNA research. These genes represent frequently mutated drivers in major cancer types, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), colorectal cancer, melanoma, and breast cancer, making them prime targets for therapeutic development and monitoring.

ctDNA refers to fragmented DNA molecules released into the bloodstream by tumor cells through apoptosis and necrosis, carrying the same genetic alterations present in the tumor tissue. Compared to traditional tissue biopsies, liquid biopsy offers distinct advantages: it is minimally invasive, captures tumor heterogeneity, enables real-time monitoring of treatment response, and facilitates detection of resistance mechanisms. The half-life of ctDNA is remarkably short (approximately 16 minutes to several hours), allowing researchers to monitor dynamic changes in tumor burden almost in real-time [30].

The effective design of assays for ctDNA analysis must account for several technical challenges, primarily the low abundance of ctDNA in plasma, especially in early-stage disease or low-shedding tumors, where it can constitute less than 0.1% of total cell-free DNA. This necessitates highly sensitive detection methods capable of identifying rare mutant alleles against a background of wild-type DNA. Additional considerations include pre-analytical variables (blood collection, processing, and DNA extraction), assay specificity, and standardization across laboratories [30].

Molecular Pathways and Biological Significance

Oncogenic mutations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and ESR1 converge on a limited number of critical signaling pathways that control cellular proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Understanding these pathways is essential for appropriate assay design and interpretation of results.

The EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor) gene encodes a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase. Upon ligand binding, EGFR activates downstream signaling cascades, primarily the RAS-RAF-MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways, which promote cell growth and inhibit apoptosis. Oncogenic EGFR mutations, particularly in NSCLC, often occur in the tyrosine kinase domain (exons 18-21) and lead to constitutive kinase activity independent of ligand binding. The most common sensitizing mutations include exon 19 deletions and the L858R point mutation in exon 21, both predicting response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Conversely, the T790M mutation in exon 20 is a well-characterized resistance mechanism to first-generation TKIs [31] [32].

The KRAS (Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog) gene encodes a small GTPase that acts as a critical signal transducer between activated cell surface receptors (including EGFR) and intracellular effectors. KRAS alternates between GTP-bound (active) and GDP-bound (inactive) states. Oncogenic mutations, most frequently at codons 12, 13, and 61, impair GTP hydrolysis, resulting in constitutive signaling through effectors like RAF and PI3K. KRAS mutations are prevalent in pancreatic, colorectal, and lung cancers and have historically been difficult to target therapeutically, though recent drugs target specific variants like KRAS G12C [33] [31].

The BRAF (B-Raf Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase) gene encodes a serine/threonine-protein kinase that is a key component of the MAPK signaling pathway. The most common oncogenic mutation, BRAF V600E, results in constitutive kinase activity and continuous stimulation of MAPK signaling, promoting uncontrolled cell proliferation. BRAF mutations are particularly prevalent in melanoma, where they serve as predictive biomarkers for BRAF inhibitor therapies [33].

The PIK3CA (Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha) gene encodes the catalytic subunit of PI3K. Oncogenic mutations, frequently found in hotspots within the helical (exon 9) and kinase (exon 20) domains, lead to hyperactivation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway, enhancing cell survival, growth, and metabolism. PIK3CA mutations are common in breast, colorectal, and other solid tumors and have emerged as biomarkers for PI3K inhibitors, such as alpelisib in PIK3CA-mutant breast cancer [34].