Advanced 3D-QSAR and Virtual Screening Strategies for Novel Glioblastoma Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of virtual screening utilizing 3D-QSAR models for the discovery of glioblastoma therapeutics.

Advanced 3D-QSAR and Virtual Screening Strategies for Novel Glioblastoma Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of virtual screening utilizing 3D-QSAR models for the discovery of glioblastoma therapeutics. It covers the foundational principles of 3D-QSAR, including CoMFA and CoMSIA, and their application against key glioblastoma targets like PLK1, mIDH1, and FAK. The content details methodological workflows integrating machine learning for enhanced predictive accuracy and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. Furthermore, it examines rigorous validation protocols involving molecular docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulations to assess binding stability and drug-likeness. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current computational strategies to accelerate the design of effective, targeted therapies for this aggressive brain cancer.

Glioblastoma's Urgent Challenge and 3D-QSAR's Foundational Role in Target Identification

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive and lethal primary malignant brain tumor in adults, presenting significant challenges to patient survival and treatment efficacy [1]. Despite extensive research, the median survival remains a dismal 12 to 15 months, with a five-year survival rate of only 7.2% [1] [2]. The current standard of care includes maximal safe surgical resection followed by radiotherapy with concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide (TMZ) chemotherapy, with or without Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) [3] [4]. This aggressive multimodal approach provides only modest survival benefits, highlighting the critical need for advanced therapeutic strategies.

GBM's treatment resistance stems from three interconnected biological challenges: intrinsic tumor aggressiveness, pronounced therapeutic resistance, and the restrictive blood-brain barrier (BBB). GBM exhibits remarkable molecular heterogeneity, both between patients and within individual tumors, with distinct transcriptional subtypes (proneural, neural, classical, and mesenchymal) that demonstrate differential therapeutic responses [1] [5]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) fosters immunosuppression through tumor-associated macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and regulatory T cells, creating a niche conducive to tumor growth and immune evasion [1]. Additionally, glioma stem-like cells (GSCs) with self-renewal capabilities contribute to tumor persistence, recurrence, and resistance [1] [5].

The BBB represents a fundamental obstacle to effective drug delivery, excluding approximately 98% of small molecules and almost all macromolecular agents from the brain [6] [7]. While GBMs exhibit regions of BBB disruption visible as contrast enhancement on MRI, clinically significant tumor burden persists behind an intact BBB in areas of invasive margins and non-enhancing edema, protecting infiltrating cells from therapeutic exposure [7]. Overcoming these interconnected challenges requires innovative approaches that address GBM's complex biology while ensuring adequate drug delivery to all tumor regions.

Molecular Characterization and Therapeutic Targets

Key Molecular Alterations in Glioblastoma

GBM is characterized by diverse molecular alterations that drive tumorigenesis, progression, and therapeutic resistance. The 2021 WHO classification of CNS tumors recognizes GBM as a grade IV IDH-wildtype glioma with specific molecular features including TERT promoter mutations, EGFR amplification, and the combined gain of chromosome 7 and loss of chromosome 10 [4]. Molecular profiling has identified several critical pathways and alterations that represent promising therapeutic targets, summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Molecular Targets in Glioblastoma and Experimental Therapeutic Approaches

| Target/Pathway | Alteration Frequency | Biological Consequence | Targeted Agents in Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | Amplified in ~40-60% of GBMs [1] | Enhanced proliferation, survival, and invasion through RTK/MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling [1] | Antibody-drug conjugates, CAR-T therapies (e.g., CART-EGFR-IL13Ra2) [8] |

| IDH1 | Mutated in ~10% of GBMs (secondary GBM) [1] | Production of oncometabolite 2-HG, leading to epigenetic dysregulation and blocked differentiation [9] | Ivosidenib, olutasidenib, vorasidenib [9] [8] |

| MGMT | Promoter methylated in ~35-50% of GBMs [3] | Predictive of response to temozolomide; methylated tumors have better survival (18.4 vs. 10.8 months) [3] | - |

| PTEN | Lost in ~25-40% of GBMs [1] | Constitutive PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activation, promoting growth and survival [1] | mTOR inhibitors, PI3K/AKT pathway inhibitors |

| PDGFR-α | Amplified/overexpressed in ~15% of GBMs [1] | Enhanced proliferative signaling, particularly in proneural subtype [1] | Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| TERT promoter | Mutated in ~60-80% of primary GBMs [4] | Telomerase reactivation and cellular immortalization [4] | - |

Signaling Pathways as Therapeutic Targets

Several oncogenic signaling pathways are recurrently dysregulated in GBM and represent rational targets for therapeutic intervention. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is a central regulator of tumor growth and survival, frequently activated through EGFR amplification or PTEN loss [1]. Despite being a promising target, clinical trials with mTOR inhibitors have shown limited success, highlighting the need for combination approaches and better patient stratification [1]. The RTK/RAS/MAPK pathway is another critical signaling cascade, often driven by EGFR, PDGFR, or MET alterations, making it a compelling target for multi-RTK inhibition strategies [5].

Metabolic reprogramming represents an emerging targeting opportunity, with mutant IDH1 (mIDH1) being a particularly validated target. mIDH1 acquires a neomorphic activity that converts α-ketoglutarate to the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), which competitively inhibits α-KG-dependent dioxygenases, leading to histone and DNA hypermethylation and subsequent changes in gene expression that drive tumorigenesis [9]. Targeting this pathway with specific inhibitors such as ivosidenib (AG-120) has shown clinical efficacy, particularly in IDH-mutant secondary GBMs and other IDH-mutant cancers [9].

Computational Approaches: Virtual Screening with 3D-QSAR Models

Foundation of 3D-QSAR in Glioblastoma Drug Discovery

Virtual screening using three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) models represents a powerful computational approach for identifying and optimizing novel therapeutic compounds against glioblastoma targets. This method establishes a mathematical correlation between the three-dimensional structural features of molecules and their biological activity, enabling the rational design of compounds with improved efficacy and selectivity [9] [10]. The primary 3D-QSAR techniques include Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), which analyze steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields around aligned molecules [9].

Recent applications of 3D-QSAR in glioblastoma drug discovery have demonstrated promising results. For mIDH1 inhibitors, studies utilizing pyridin-2-one-based compounds have yielded highly predictive CoMFA (R² = 0.980, Q² = 0.765) and CoMSIA (R² = 0.997, Q² = 0.770) models, enabling the design of novel structures with enhanced predicted activity [9]. Similarly, for dihydropteridone derivatives targeting Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1), 3D-QSAR models have shown excellent predictive power (Q² = 0.628, R² = 0.928), facilitating the identification of critical structural features responsible for anti-glioma activity [10].

Experimental Protocol: 3D-QSAR Model Development and Virtual Screening

Protocol Title: Development and Validation of 3D-QSAR Models for Virtual Screening of Glioblastoma Therapeutics

Objective: To create predictive 3D-QSAR models for identifying novel compounds with potential efficacy against glioblastoma molecular targets.

Materials and Software:

- Chemical structure drawing software (ChemDraw)

- Molecular modeling suite (HyperChem, SYBYL, Schrodinger)

- Statistical analysis software (CODESSA, R, Python)

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

Data Set Curation and Preparation

- Collect a structurally diverse set of compounds with known biological activity (IC₅₀ or EC₅₀ values) against the glioblastoma target of interest

- Divide compounds into training set (≈80%) for model development and test set (≈20%) for validation [10]

- Sketch 2D chemical structures using ChemDraw and convert to 3D representations

- Perform geometry optimization using molecular mechanics (MM+ force field) followed by semi-empirical methods (AM1 or PM3) until root mean square gradient reaches <0.01 kcal/mol·Å [10]

Molecular Alignment

- Identify common structural features or pharmacophores for alignment

- Utilize field-fit, database, or receptor-based alignment methods

- Ensure consistent orientation of all molecules in the dataset

3D-QSAR Model Construction

- Calculate interaction fields using CoMFA (steric and electrostatic) and CoMSIA (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor) [9]

- Set grid spacing to 2.0 Å extending 4.0 Å beyond all molecules

- Apply standard scaling options (e.g., block-centered) to normalize field values

Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis

- Perform cross-validated PLS analysis to determine optimal number of components

- Use leave-one-out or bootstrapping methods for internal validation

- Generate final non-cross-validated model using optimal component number

Model Validation and Visualization

- Assess model quality using statistical parameters: R² (goodness of fit), Q² (predictive ability), F-value (statistical significance), standard error of estimate [10]

- Validate model externally using test set compounds not included in training

- Generate coefficient contour maps to visualize regions where specific molecular properties enhance or diminish biological activity

Virtual Screening and Compound Design

- Apply validated model to screen virtual compound libraries

- Design novel compounds by scaffold hopping and structural modification based on contour map insights [9]

- Predict activity of newly designed compounds using the established model

- Select top candidates for synthesis and biological evaluation

Quality Control:

- Ensure chemical diversity in both training and test sets

- Verify absence of chance correlation through Y-scrambling

- Confirm model robustness through multiple validation techniques

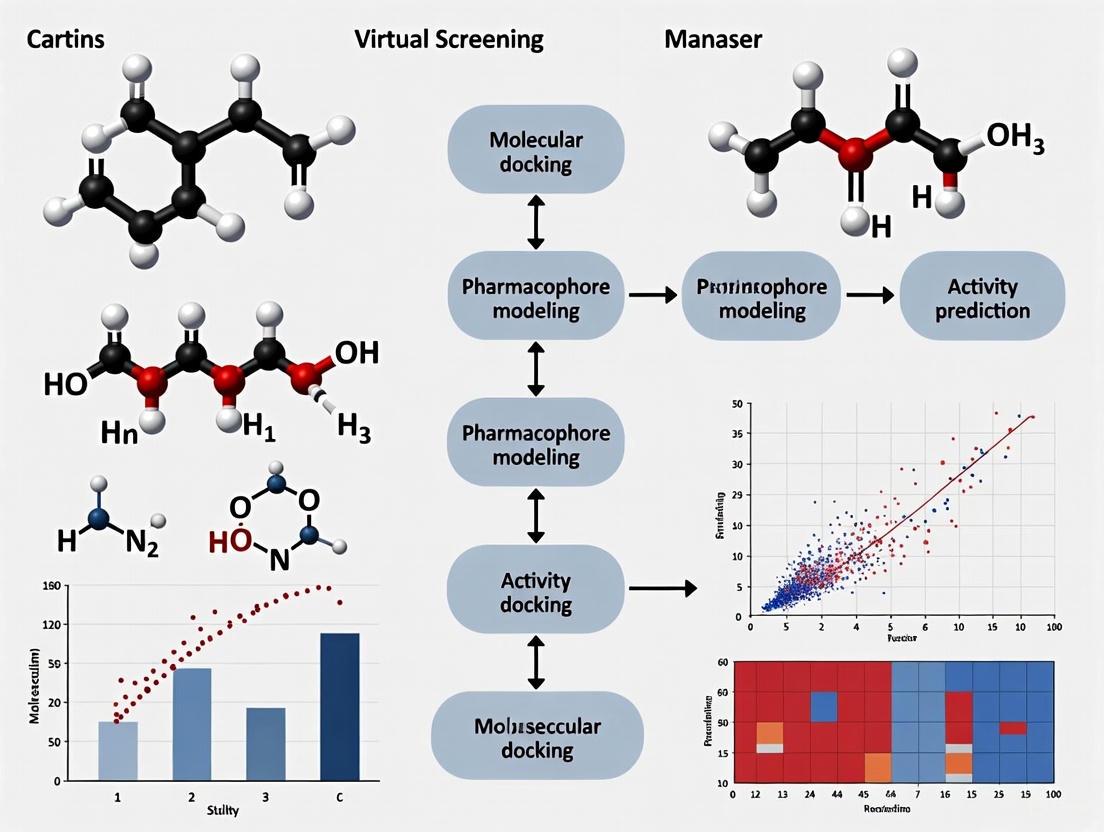

Diagram 1: 3D-QSAR Virtual Screening Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the comprehensive process for developing and applying 3D-QSAR models in glioblastoma drug discovery, from initial data collection to final candidate selection.

Advanced Therapeutic Delivery Strategies

Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration Technologies

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) and blood-brain tumor barrier (BBTB) represent significant obstacles for glioblastoma therapy, restricting delivery of both conventional chemotherapeutics and novel targeted agents to tumor sites [5] [6]. While contrast-enhancing regions of GBM exhibit some BBB disruption, infiltrating tumor cells in non-enhancing regions remain protected by an intact BBB, creating therapeutic sanctuaries that contribute to treatment failure and recurrence [7]. To address this challenge, numerous innovative strategies are being developed to enhance drug delivery across the BBB, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Advanced Strategies for Enhanced Drug Delivery Across the BBB in Glioblastoma

| Strategy Category | Specific Approach | Mechanism of Action | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Barrier Modulation | Focused Ultrasound with Microbubbles [6] | Temporary BBB disruption through acoustic cavitation | Early-phase clinical trials |

| Optical BBB Modulation (optoBBTB) [6] | Light-activated gold nanoparticles target tight junctions | Preclinical (mouse models) | |

| Hyperosmolar Agents (Mannitol) [6] | Osmotic shrinkage of endothelial cells opens tight junctions | Clinical use | |

| Nanotechnology-Based Delivery | Gold Nanoparticles [6] | Target tight junction proteins (e.g., JAM-A) for reversible BBB opening | Preclinical |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles [3] | Protect payload, enhance circulation time, and enable functionalization | Preclinical to early clinical | |

| Exosome-Mediated Delivery [3] | Exploit natural vesicle trafficking for enhanced brain penetration | Preclinical | |

| Biological Transport Mechanisms | Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis [6] | Utilize endogenous transport systems (e.g., transferrin receptor) | Preclinical to clinical |

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides [5] | Facilitate cellular uptake through membrane interaction | Preclinical | |

| Trojan Bacteria [6] | Engineered bacteria as drug carriers that cross BBB | Preclinical | |

| Localized Delivery Systems | Convection-Enhanced Delivery (CED) [8] | Direct infusion into brain tissue under positive pressure | Clinical trials |

| Implantable Wafers (Gliadel) [5] | Local sustained release of chemotherapeutics | FDA-approved | |

| Intrathecal Administration [5] | Direct administration into cerebrospinal fluid | Clinical use |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating BBB Penetration Using Advanced Models

Protocol Title: Assessment of Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration in Preclinical Glioblastoma Models

Objective: To evaluate the ability of therapeutic compounds to cross the BBB and reach tumor tissue using physiologically relevant models.

Materials:

- In vitro BBB models (primary human brain endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes)

- Transwell culture systems

- Glioblastoma mouse models (genetically engineered, patient-derived xenografts)

- Microdialysis systems

- LC-MS/MS for drug quantification

- Fluorescent or radiolabeled compounds

- MRI with contrast agents

Procedure:

In Vitro BBB Model Establishment

- Culture primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells on Transwell inserts

- Add primary human astrocytes and pericytes to basolateral chamber

- Monitor transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) daily until >150 Ω·cm²

- Validate barrier integrity with sodium fluorescein (0.3-0.5% leakage acceptable)

Compound Permeability Assessment

- Apply test compound to apical (blood) compartment

- Sample from basolateral (brain) compartment at timed intervals

- Quantify compound concentration using LC-MS/MS

- Calculate apparent permeability coefficient (Papp)

- Include control compounds with known BBB penetration (e.g., caffeine, loperamide)

In Vivo Evaluation in Glioblastoma Models

- Establish orthotopic glioblastoma models using patient-derived cells or genetically engineered systems

- Administer test compound via appropriate route (IV, oral)

- Collect plasma and brain samples at multiple time points

- Separate brain into different regions: enhancing tumor, non-enhancing tumor, normal brain

- Quantify drug concentrations in each compartment

- Calculate brain-to-plasma ratio (Kp) and unbound partition coefficient (Kp,uu)

Advanced Imaging and Distribution Analysis

- Utilize fluorescently labeled compounds with confocal microscopy

- Employ matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) imaging mass spectrometry

- Perform microdialysis to measure free drug concentrations in brain extracellular fluid

- Use positron emission tomography (PET) with radiolabeled compounds for real-time tracking

Functional Efficacy Assessment

- Correlate drug concentrations with pharmacodynamic markers (target engagement)

- Evaluate antitumor efficacy in relation to achieved brain concentrations

- Assess survival benefit in treated versus control animals

Data Analysis:

- Compare brain penetration parameters across different compound formulations

- Establish correlation between in vitro permeability and in vivo brain distribution

- Determine whether therapeutically relevant concentrations are achieved at target site

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Glioblastoma Therapeutic Development

| Reagent/Material | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | U87-MG, U251, T98G [5] | In vitro screening of compound efficacy | Well-characterized, easy to culture |

| Patient-derived GSCs [3] | Study therapy resistance and screening | Maintain tumor heterogeneity, stem-like properties | |

| Animal Models | Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) [6] | Preclinical efficacy studies | Recapitulate human tumorigenesis, intact immune system |

| Patient-derived xenografts (PDX) [6] | Personalized therapy testing | Maintain original tumor characteristics | |

| Molecular Biology Tools | IDH1 R132H mutation inhibitors [9] | Target validation and compound screening | Specific for neomorphic activity of mutant IDH1 |

| EGFRvIII-targeting agents [1] | Study of classical GBM subtype | Target common EGFR variant in GBM | |

| BBB Penetration Assessment | In vitro BBB models [5] | Preliminary screening of BBB penetration | High-throughput capability, reduced animal use |

| Gold nanoparticles (JAM-A targeted) [6] | Optical modulation of BBB | Reversible, region-specific BBB opening | |

| Computational Tools | CoMFA/CoMSIA software [9] [10] | 3D-QSAR model development | Relationship between structure and activity |

| Molecular docking programs | Virtual screening | Prediction of ligand-target interactions |

Emerging Clinical Approaches and Future Perspectives

The glioblastoma therapeutic landscape is rapidly evolving with numerous innovative approaches entering clinical development. Immunotherapy strategies, including checkpoint inhibitors, dendritic cell vaccines, and CAR-T therapies, are being actively investigated, though their efficacy remains limited by the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and poor trafficking to tumor sites [3] [8]. Recent clinical trials reflect a trend toward combination therapies that target multiple resistance mechanisms simultaneously, such as the combination of TTFields with immune checkpoint inhibitors [8].

Metabolic targeting represents another promising avenue, with drugs like atovaquone being evaluated in combination with radiation therapy for pediatric high-grade gliomas [8]. The recognition that a significant proportion of GBMs exhibit MTAP deletion has led to the development of selective therapeutic agents such as TNG456, currently in phase I/II trials for solid tumors with MTAP loss [8]. Additionally, advanced delivery systems including convection-enhanced delivery (CED) of radionuclides (186RNL) and locally administered immunotherapies (D2C7-IT) are being explored to overcome BBB limitations [8].

The integration of computational approaches like 3D-QSAR with experimental validation holds significant promise for accelerating the discovery of effective glioblastoma therapies. As our understanding of GBM biology deepens, future therapeutic strategies will likely involve personalized combination approaches that simultaneously target driver pathways, modulate the immunosuppressive microenvironment, and overcome BBB restrictions, ultimately leading to improved outcomes for this devastating disease.

Diagram 2: Multifaceted Approach to Overcoming GBM Therapeutic Resistance. This diagram illustrates the interconnected resistance mechanisms in glioblastoma and corresponding strategic approaches to overcome them, culminating in an integrated treatment paradigm.

Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) is an advanced computational method that correlates the three-dimensional molecular properties of compounds with their biological activity. Unlike traditional 2D-QSAR, which uses molecular descriptors invariant to conformation (e.g., logP, molecular weight), 3D-QSAR utilizes descriptors derived from the spatial structure of molecules, particularly their steric and electrostatic fields [11] [12]. This approach is grounded in the principle that biological binding occurs in three dimensions; a receptor perceives a ligand not as a set of atoms, but as a shape carrying complex interaction forces [12]. The method is especially valuable when the three-dimensional structure of the target receptor is unknown [12]. Within glioblastoma research, 3D-QSAR has been successfully applied to identify and optimize inhibitors for key targets such as acid ceramidase (ASAH1) and Chitinase-3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1), demonstrating its critical role in advancing therapeutic discovery [13] [14].

Core Theoretical Principles

Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs)

The foundational concept of 3D-QSAR is the Molecular Interaction Field (MIF). An MIF represents the spatial distribution of a specific molecular property or interaction potential around a molecule. The biological receptor does not see a ligand as a set of atoms and bonds; rather, it perceives a shape that carries complex forces, which are quantified as MIFs [12]. These fields are typically calculated using a probe atom or group placed at numerous points on a 3D lattice grid surrounding the molecule.

- Steric Field: This field represents regions of molecular bulk and is probed using a neutral atom, typically an sp3 carbon. The interaction energy is often calculated using a Lennard-Jones potential, which describes repulsive (due to electron cloud overlap) and attractive (dispersion) forces [11] [12]. Repulsive steric interactions can clash with the receptor, while attractive interactions can indicate complementary shape matching.

- Electrostatic Field: This field maps the distribution of positive and negative electrostatic potentials around the molecule. It is probed using a charged atom (e.g., a +1 charged sp3 carbon) and calculated using Coulomb's law [11] [12]. Electrostatic interactions act over longer distances and guide the initial approach and orientation of the ligand towards the receptor site.

- Additional Fields: Modern 3D-QSAR methods extend beyond steric and electrostatic fields. The Comparative Molecular Similarity Index Analysis (CoMSIA) method, for example, can additionally calculate hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor and acceptor fields, providing a more comprehensive profile of a molecule's interaction potential [11] [15].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow involved in creating and using these molecular fields for 3D-QSAR analysis.

The Critical Role of Molecular Alignment

A pivotal and often challenging step in 3D-QSAR is molecular alignment, which involves superimposing all molecules in a dataset into a common 3D coordinate system [11]. The underlying assumption is that the molecules share a similar binding mode to the biological target. A poor alignment can introduce significant noise and undermine the predictive power of the model [16].

Common alignment strategies include:

- Template-based Alignment: Molecules are superimposed onto a common reference structure, often a high-affinity ligand or a crystallographically determined bioactive conformation [11] [15].

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS): The largest substructure shared among all molecules is identified and used as the alignment framework [11] [17].

- Pharmacophore-based Alignment: Molecules are aligned based on key pharmacophoric features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, aromatic rings, hydrophobic centers) [13].

- Field-based Alignment: Advanced methods bypass atom-to-atom matching and instead align molecules by maximizing the overlap of their molecular interaction fields, which is particularly useful for structurally diverse datasets [16].

Table 1: Common Molecular Alignment Methods in 3D-QSAR

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template-Based | Superposition on a reference molecule (e.g., a known active) [15]. | Simple, intuitive, good for congeneric series. | Highly dependent on the choice and conformation of the template. |

| Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) | Identifies the largest shared substructure for alignment [11] [17]. | Objective, automatable, preserves core geometry. | Less effective for datasets with high structural diversity. |

| Pharmacophore-Based | Alignment based on key functional features essential for binding [13]. | Focuses on biologically relevant points. | Requires prior knowledge or hypothesis about the pharmacophore. |

| Field-Based | Optimizes overlap of steric/electrostatic fields rather than atoms [16]. | Handles structurally diverse molecules effectively. | Computationally intensive. |

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA)

CoMFA was the first widely adopted 3D-QSAR method. Its protocol involves several defined stages [11] [15] [18]:

- Data Preparation: A set of molecules with known biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) is compiled. Activity values are typically converted to pIC₅₀ or pKi for analysis.

- Molecular Modeling and Alignment: 3D structures are generated, energy-minimized, and aligned using one of the methods described in Section 2.2.

- Field Calculation: The aligned molecules are placed into a 3D grid. A probe atom (e.g., an sp³ carbon with a +1 charge) is used to calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies at each grid point.

- Model Building: The calculated field energies for all molecules become the independent variables (X), and the biological activities are the dependent variables (Y). Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is used to correlate the fields to the activity, handling the high dimensionality and collinearity of the data [19] [11].

- Validation: The model is validated using techniques like leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation ( yielding Q²) and an external test set ( yielding R²ₚᵣₑd) to ensure its predictive robustness and avoid overfitting [11] [15].

- Visualization: The results are presented as 3D coefficient contour maps. These maps show regions in space where specific steric or electrostatic features are associated with increased or decreased activity, providing an intuitive guide for chemists [11].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Index Analysis (CoMSIA)

CoMSIA was developed to address some limitations of CoMFA, particularly its sensitivity to molecular alignment and the abrupt changes in its fields [11] [15]. The CoMSIA protocol is similar to CoMFA but with a key difference in field calculation.

Instead of using Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials, CoMSIA uses Gaussian-type functions to calculate similarity indices for different fields at grid points [11] [15]. This approach has two major benefits:

- It results in smoother potential maps that are less sensitive to small changes in molecular orientation.

- It can easily incorporate additional interaction fields beyond steric and electrostatic, such as hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields, offering a more nuanced view of structure-activity relationships [11] [15].

Table 2: Comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA Methods

| Feature | CoMFA | CoMSIA |

|---|---|---|

| Fields | Steric, Electrostatic [15]. | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, Hydrogen Bond Donor, Hydrogen Bond Acceptor [11] [15]. |

| Potential Function | Lennard-Jones (Steric), Coulomb (Electrostatic) [11]. | Gaussian-type [11] [15]. |

| Sensitivity to Alignment | High [11]. | Moderate; more robust [11]. |

| Contour Maps | Can have abrupt boundaries [11]. | Smoother, more interpretable boundaries [11]. |

Application Note: 3D-QSAR in Glioblastoma Therapeutic Research

Case Study: Discovery of ASAH1 Inhibitors

Acid Ceramidase (ASAH1) is a promising therapeutic target for glioblastoma. A recent study employed an innovative machine learning-based 3D-QSAR approach to discover novel ASAH1 inhibitors [14].

- Objective: To build a predictive model for ASAH1 inhibition and identify new lead compounds.

- Methodology: The study utilized a dataset of 103 known inhibitors and 431 3D descriptors. An Extra Trees Regressor (ETR) algorithm was used to construct the model, which achieved high predictive performance (R² = 0.867, RMSE = 0.248) [14].

- Key Insights: Descriptor analysis identified the Radial Distribution Function (RDF20s) as a critical structural descriptor influencing inhibitory activity [14].

- Outcome: Virtual screening of compound libraries using the validated model identified 77 promising candidates, with N-hexylsalicylamide emerging as the top hit. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed its stable binding to the ASAH1 active site, involving a key interaction with residue Cys143, and calculated a favorable binding free energy [14].

Case Study: Development of CHI3L1 Inhibitors

Chitinase-3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1) is another glioblastoma target implicated in tumor progression and immune evasion. A 2025 study applied 3D-QSAR in a virtual screening campaign [13].

- Objective: Identify small-molecule CHI3L1 inhibitors with functional activity in glioblastoma spheroids.

- Methodology: A structure-based 3D pharmacophore model was developed and used to screen over 4.4 million compounds [13].

- Experimental Validation: From 35 selected candidates, two compounds (8 and 39) showed dose-dependent binding to CHI3L1 in Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) assays, with dissociation constants (Kd) of 6.8 μM and 22 μM, respectively [13].

- Functional Efficacy: In 3D glioblastoma spheroid models, compound 8 reduced spheroid viability and attenuated phospho-STAT3 levels, demonstrating on-target activity and establishing it as a translationally viable scaffold [13].

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for a 3D-QSAR-driven drug discovery project in glioblastoma, integrating the principles and case studies discussed.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Software (e.g., Flare, SYBYL) | Provides an environment for generating 3D structures, performing energy minimization, and conducting molecular alignments [17]. | Essential for the preparatory steps of 3D model building and visualization of contour maps. |

| 3D-QSAR Algorithms (CoMFA, CoMSIA) | Integrated modules within larger software suites that perform the specific calculations for field generation and PLS regression [17] [15] [18]. | The core computational engine for deriving the quantitative structure-activity model. |

| Cheminformatics Toolkits (e.g., RDKit) | Open-source libraries for cheminformatics. Can generate 2D and 3D molecular descriptors and handle file format conversions [11] [17]. | Used for descriptor calculation and integrating 2D and 3D QSAR approaches. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | A database of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and protein-ligand complexes [17]. | Source of template structures for alignment and for structure-based pharmacophore generation. |

| Compound Databases (e.g., ZINC20, ChemDiv) | Public and commercial libraries of purchasable compounds with associated structures [20]. | The source of molecules for virtual screening after a 3D-QSAR model is built. |

| Validation Assays (e.g., MST, SPR) | Biophysical techniques (Microscale Thermophoresis, Surface Plasmon Resonance) to validate binding of virtual screening hits [13]. | Critical for experimental confirmation of computational predictions in vitro. |

Advanced Topics and Future Directions

Addressing the Alignment Challenge

The critical dependence on molecular alignment has driven the development of alignment-independent 3D-QSAR techniques. Methods like 3D-SDAR (Spectral Data-Activity Relationship) use descriptors based on inter-atomic distances and chemical shifts, which are inherently independent of a global molecular frame [19]. Remarkably, studies have shown that for some targets, models built from simple 2D->3D converted structures (without elaborate energy minimization or alignment) can perform on par with or even superior to more computationally intensive approaches, drastically reducing model development time [19].

Integration with Machine Learning and Dynamics

The field of 3D-QSAR is evolving through integration with other computational disciplines:

- Machine Learning (ML): As demonstrated in the ASAH1 case study, ML algorithms like Extra Trees Regressor can be trained on 3D molecular descriptors to build highly predictive models, often outperforming traditional statistical methods [14].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD simulations are used to study the stability and detailed binding modes of hits identified from 3D-QSAR. Analysis of parameters like Radius of Gyration (Rg) and binding free energy via MM/PBSA calculations provides deeper insights into the dynamic behavior of ligand-receptor complexes, validating and refining the static pictures provided by QSAR [15] [18] [14].

Glioblastoma (GBM) remains one of the most aggressive and treatment-resistant primary brain tumors, characterized by high heterogeneity, invasive potential, and poor survival rates. The current standard of care, including surgical resection, radiotherapy, and temozolomide chemotherapy, provides limited benefit, with median survival typically not exceeding 15 months [21]. This dire prognosis has accelerated research into targeted therapeutic approaches, with virtual screening employing three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) models emerging as a powerful computational strategy for efficient drug discovery [10] [9]. This protocol focuses on four promising glioblastoma drug targets—PLK1, mutant IDH1 (mIDH1), FAK, and ASAH1—and details the application of 3D-QSAR models for the identification and optimization of novel inhibitors against these targets.

Target Profiles and Quantitative Activity Data

Table 1: Key Glioblastoma Drug Targets and Inhibitor Profiles

| Target | Biological Role in GBM | Exemplary Inhibitors | Reported Potency (IC50) | QSAR Model Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLK1 | Regulates cell division, DNA checkpoint, microtubule dynamics; overexpressed in GBM [10] | Dihydropteridone derivatives [10] | 0.18-1.07 μM [10] | 3D-QSAR: Q²=0.628, R²=0.928 [10] |

| mIDH1 | Gain-of-function mutation causes 2-HG accumulation, driving epigenetic dysregulation [9] [22] | Ivosidenib (AG-120); Pyridin-2-one derivatives [9] | 0.035-4.200 μM [9] | CoMFA: R²=0.980, Q²=0.765; CoMSIA: R²=0.997, Q²=0.770 [9] |

| FAK | Mediates tumor progression, invasion, and resistance via integrin signaling [21] | VS4718; Novel compounds from ML screening [23] [21] | Varies by compound (pIC50 4.00-10.00) [21] | ML Model: R²=0.892, MAE=0.331 [21] |

| ASAH1 | Lysosomal enzyme regulating ceramide/S1P balance; overexpression in GSCs confers poor prognosis [14] [24] | Carmofur; N-hexylsalicylamide; Novel ML-derived inhibitors [14] | 11-104 μM (carmofur vs. GSCs) [24] | ML-QSAR (ETR): R²=0.867, RMSE=0.248 [14] |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: 3D-QSAR Model Development for PLK1 Inhibitors

Application Note: For Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibitors, particularly dihydropteridone derivatives, the integration of 2D and 3D-QSAR approaches has proven valuable for understanding critical structural features influencing anticancer activity [10].

Experimental Protocol:

Compound Preparation:

- Sketch 2D structures of dihydropteridone derivatives using ChemDraw [10].

- Perform initial geometry optimization using molecular mechanics (MM+ force field) in HyperChem [10].

- Conduct semi-empirical quantum mechanical optimization (AM1 or PM3 method) using the Polak-Ribiere algorithm until the root mean square gradient is below 0.01 [10].

Descriptor Calculation & Model Construction:

- Calculate molecular descriptors (quantum chemical, topological, geometrical, electrostatic) using CODESSA software [10].

- For the 3D-QSAR model, utilize the Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) method. The model should be constructed and validated using a dataset of at least 34 compounds, randomly split into training (≈26 compounds) and test (≈8 compounds) sets [10].

- For the 2D-linear model, apply the Heuristic Method (HM) to select optimal descriptors. For the 2D-nonlinear model, employ the Gene Expression Programming (GEP) algorithm [10].

Model Validation:

- Validate models using internal cross-validation (e.g., leave-one-out) and external test set prediction.

- Acceptable models should have a cross-validated R² (Q²) > 0.5 and a high conventional R². The 3D-QSAR model for dihydropteridone derivatives demonstrated Q²=0.628 and R²=0.928, indicating excellent predictive power [10].

Activity Prediction & Design:

- Analyze contour maps (e.g., steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic) from the CoMSIA model to identify favorable and unfavorable regions for substitution [10].

- Use the "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN) descriptor from the 2D model, combined with hydrophobic field information, to propose novel structures with predicted high activity [10].

Protocol 2: Virtual Screening for Mutant IDH1 Inhibitors using CoMFA/CoMSIA

Application Note: Mutant IDH1 (mIDH1) produces the oncometabolite 2-HG, and its inhibition is a validated strategy in GBM and AML. 3D-QSAR models like CoMFA and CoMSIA are highly effective for scaffold hopping and activity prediction of pyridin-2-one based inhibitors [9].

Experimental Protocol:

Data Set Curation & Alignment:

- Curate a set of 47 known pyridin-2-one based mIDH1 inhibitors with associated IC50 values [9].

- Divide compounds into a training set (≈38 compounds) for model building and a test set (≈9 compounds) for validation [9].

- Perform molecular alignment, which is critical for 3D-QSAR, using the common scaffold or a pharmacophore-based method.

CoMFA & CoMSIA Modeling:

- Calculate steric and electrostatic field energies for CoMFA using a Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potential, respectively, with a sp³ carbon probe atom [9].

- For CoMSIA, calculate similarity indices using five different fields: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor [9].

- Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to build relationships between the molecular fields and biological activity (pIC50).

Virtual Screening & Scaffold Hopping:

- Use the validated CoMFA/CoMSIA models to predict the activity of virtual compound libraries (e.g., natural product databases like Coconut) [25].

- Perform scaffold hopping to design novel chemotypes while maintaining key interactions identified in the contour maps.

- Select top-ranked compounds (e.g., C3, C6, C9) with higher predicted pIC50 than reference compounds (e.g., AGI-5198) for further study [9].

Validation via Molecular Dynamics (MD):

- Subject the top virtual hits to MD simulations (e.g., 100-200 ns) to assess complex stability.

- Analyze parameters like Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Radius of Gyration (Rg), and calculate binding free energies using methods like MM/PBSA. A stable RMSD profile and high negative binding free energy (e.g., -93.25 ± 5.20 kcal/mol for a hit compound) confirm stable binding [9] [25].

Protocol 3: Machine Learning-QSAR for FAK and ASAH1 Inhibitor Screening

Application Note: For targets like FAK and ASAH1, where larger datasets are available, Machine Learning-based QSAR (ML-QSAR) offers a robust framework for activity prediction and high-throughput virtual screening [14] [21].

Experimental Protocol:

Data Collection and Curation:

- For FAK inhibitors, extract IC50 data and structures for ~1280 compounds from the ChEMBL database (Target:CHEMBL2695). For cell-based activity, use data from ~2608 compounds tested on U87-MG glioblastoma cells (Cell Line: CHEMBL3307575) [21].

- For ASAH1 inhibitors, compile a dataset of 103 inhibitors from ChEMBL and literature [14].

- Express activity as pIC50 (-logIC50) for model regression.

Descriptor Calculation and Feature Selection:

Machine Learning Model Building and Validation:

- Train multiple ML algorithms (e.g., LightGBM, Random Forest, XGBoost, Extra Trees Regressor) on the training set (80% of data) using 10-fold cross-validation [21].

- Optimize hyperparameters via grid search.

- Validate models on a held-out test set (20% of data). A robust FAK model achieved R²=0.892 and MAE=0.331, while an ASAH1 model achieved R²=0.867 and RMSE=0.248 [14] [21].

Virtual Screening and ADMET Filtering:

- Apply the trained model to screen large virtual libraries (e.g., 5107 compounds for FAK) [21].

- Filter top predictions (e.g., 275 compounds for FAK) based on drug-likeness rules and predictive ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) profiles to shortlist a final set of promising candidates (e.g., 16 for FAK) for experimental validation [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Virtual Screening

| Category | Item/Software | Specific Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Algorithms | HyperChem | Molecular structure optimization using MM+ and semi-empirical methods (AM1/PM3) [10] |

| CODESSA | Calculation of quantum chemical, topological, and electrostatic molecular descriptors for 2D-QSAR [10] | |

| SYBYL (CoMFA/CoMSIA) | Performing 3D-QSAR analyses, generating steric/electrostatic contour maps [9] | |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Computing molecular fingerprints and descriptors for ML-QSAR models [21] | |

| Scikit-learn (Python) | Building and validating ML models (LightGBM, Random Forest, etc.) for activity prediction [21] | |

| Databases | ChEMBL | Sourcing bioactivity data (IC50) and structures for targets like FAK (CHEMBL2695) and ASAH1 [21] |

| Coconut Database | Natural product library for virtual screening of novel mIDH1 inhibitors [25] | |

| Experimental Reagents | Patient-derived GBM Stem Cells (GSCs) | In vitro validation of candidate inhibitors, particularly for ASAH1 targets [24] |

| U87-MG Cell Line | Standard glioblastoma cell line for initial 2D cytotoxicity and viability assays [21] | |

| 3D Spheroid Models | Advanced in vitro model for assessing compound efficacy against tumor invasion and migration [26] |

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow for Glioblastoma Therapeutics. This diagram outlines the key stages in a computational drug discovery pipeline, from target selection to experimental validation, highlighting the iterative nature of model refinement.

Diagram 2: mIDH1 Pathogenic Signaling and Inhibitor Mechanism. This pathway illustrates the consequence of mIDH1 mutation, leading to 2-HG-driven tumorigenesis, and the point of intervention for small molecule inhibitors.

In the pursuit of novel glioblastoma (GBM) therapeutics, virtual screening using 3D-QSAR models has emerged as a powerful strategy to accelerate drug discovery. The reliability of these computational models is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the underlying data. This Application Note provides a detailed protocol for curating the essential components for robust model building: compound structures and their corresponding biological activity data (IC50 values). Proper data curation ensures that predictive models are accurate, generalizable, and capable of identifying promising therapeutic candidates with a higher probability of success in pre-clinical validation [27] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources required for the data curation and modeling workflow.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Data Curation and 3D-QSAR Modeling

| Resource Name | Type/Description | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| LigPrep [29] | Software Module | Used for generating and optimizing 3D molecular structures, including energy minimization and generating possible stereoisomers and ionization states at a physiological pH. |

| RDKit [27] | Open-Source Cheminformatics Library | Facilitates molecular representation conversion (e.g., to SMILES), descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, and substructure searching during data filtering. |

| Phase [29] | Software Module | Used specifically for generating 3D-QSAR pharmacophore models, aligning molecules, and performing statistical analysis to build the predictive model. |

| PubChem/ ZINC/ DrugBank [27] | Public Chemical Databases | Primary sources for acquiring initial 2D and 3D compound structures for virtual screening. |

| CancerRxTissue [30] | Computational Tool | Provides pre-processed drug sensitivity data (e.g., predicted IC50 values) which can be used for model training, especially in oncology targets like glioblastoma. |

| IBScreen Database [29] | Chemical Database | An example of a database that can be screened using a generated pharmacophore model to identify novel hit compounds. |

| OPLS_2005 [29] | Force Field | Used during ligand preparation for energy minimization of 3D structures to ensure they represent low-energy, physically realistic conformations. |

Data Curation Workflow: A Step-by-Step Protocol

The foundation of a reliable 3D-QSAR model is a meticulously curated dataset. The workflow below outlines the comprehensive process from data collection to final model-ready dataset.

Figure 1: Data Curation Workflow for 3D-QSAR Modeling

Protocol: Data Collection and Sourcing

Objective: To gather a comprehensive and relevant set of chemical structures and their associated biological activity data against glioblastoma or related targets.

- Identify Compound Sources: Access large-scale public and commercial chemical databases.

- Public Databases: Utilize sources like PubChem, ZINC, and DrugBank to acquire initial 2D compound structures [27].

- Specialized Oncology Resources: For GBM research, leverage resources like CancerRxTissue, which provides predicted drug sensitivity data (e.g., ln(IC50)) for a wide array of compounds across cancer types, including GBM [30].

- Extract Activity Data: Collect half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values from scientific literature or experimental results. Ensure data is generated from consistent bioassays (e.g., the same cell line, such as A2780 human ovarian carcinoma or patient-derived GBM stem cells, and assay type) to maintain data integrity [29] [31].

- Record Metadata: Document critical experimental conditions for each data point, such as the cell line used, assay type, and source publication. This facilitates later data integration and analysis.

Protocol: Data Cleaning and Annotation

Objective: To ensure data accuracy, consistency, and readiness for computational analysis.

- Data Cleaning:

- Remove Duplicates: Identify and eliminate duplicate compound entries to prevent model bias [28].

- Handle Missing Values: Develop a strategy for entries with missing IC50 values or structural information. Options include removal or imputation using validated methods, with clear documentation of the approach.

- Standardize Formats: Ensure chemical structures are represented consistently, for example, by using a standard molecular representation format like SMILES [27].

- Data Annotation:

- Calculate pIC50: Convert IC50 values to pIC50 using the formula: pIC50 = -log10(IC50). This transformation creates a more linear and model-friendly scale for the response variable [29].

- Categorize Activity: For certain analyses (e.g., defining actives for pharmacophore generation), classify compounds into categories. A common practice is to define compounds as "active" (e.g., pIC50 > 5.5), "inactive" (e.g., pIC50 < 4.7), and potentially "moderately active" for the training set [29].

- Assign Unique Identifiers: Tag each compound with a unique ID to track it through the entire workflow.

Protocol: Data Transformation and Integration

Objective: To convert the curated data into a format suitable for 3D-QSAR modeling.

- Ligand Preparation and 3D Conversion:

- Use specialized software like LigPrep (Schrödinger) to generate 3D structures from 2D inputs [29].

- Perform energy minimization using a force field such as OPLS_2005 to ensure the 3D conformations are physically realistic and represent low-energy states [29].

- Generate a set of likely conformers for each molecule to account for flexibility.

- Dataset Partitioning:

Table 2: Quantitative Data Summary from a Representative 3D-QSAR Study on Quinolines [29]

| Parameter | Value / Description | Context in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Total Compounds | 62 cytotoxic quinolines | Example dataset size for model building. |

| Training Set Size | 50 compounds | Used for pharmacophore hypothesis generation and QSAR model building. |

| Test Set Size | 12 compounds | Used for independent model validation. |

| Activity Threshold (Active) | pIC50 > 5.5 | Used to categorize compounds for the training set. |

| Activity Threshold (Inactive) | pIC50 < 4.7 | Used to categorize compounds for the training set. |

| Best Pharmacophore Model | AAARRR.1061 | Result of the protocol; a hypothesis with 3 Acceptor (A) and 3 Aromatic Ring (R) features. |

| Model Correlation (R²) | 0.865 | Indicator of the model's goodness-of-fit for the training set. |

| Cross-validation (Q²) | 0.718 | Indicator of the model's internal predictive ability and robustness. |

Application in Glioblastoma Therapeutic Research

The curated data serves as the direct input for building predictive computational models for GBM drug discovery. The workflow below integrates data curation with model application, highlighting its role in a virtual screening pipeline for glioblastoma.

Figure 2: Virtual Screening Workflow for GBM Therapeutics

Protocol: Building and Validating the 3D-QSAR Model

Objective: To create a predictive model that correlates the 3D molecular features of compounds with their anti-GBM activity.

- Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation:

- Use the curated training set and software like Phase (Schrödinger) [29].

- Define pharmacophore features (e.g., Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (A), Aromatic Ring (R), Hydrophobic group (H)) based on the active compounds.

- Generate multiple hypotheses and select the best one based on a high survival score, which considers alignment, selectivity, and how well it explains the activity data [29]. An example is the AAARRR.1061 hypothesis [29].

- 3D-QSAR Model Development:

- The selected pharmacophore serves as the alignment rule for the compounds.

- A Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression analysis is performed to build the quantitative model that predicts pIC50 values based on the spatial arrangement of molecular features.

- Model Validation:

- Internal Validation: Use the test set to determine the model's predictive power (reported as Q²) [29].

- Statistical Robustness: Perform Y-Randomization tests to ensure the model is not based on chance correlation [29].

- ROC-AUC Analysis: Evaluate the model's ability to classify active vs. inactive compounds correctly [29].

Protocol: Virtual Screening and Hit Prioritization for GBM

Objective: To use the validated model to discover new potential GBM therapeutics.

- Database Screening: Screen large, drug-like databases (e.g., IBScreen, ZINC) against the validated pharmacophore model to identify compounds that match the essential 3D feature arrangement [29].

- GBM-Focused Filtering: Apply critical filters specific to brain cancers [30]:

- Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Permeability: Use computational tools (e.g., ADMETlab3.0) to predict which hits are likely to cross the BBB.

- Target Expression in GBM: Check the expression levels of the candidate drug's target in GBM versus normal brain tissue using databases like TCGA and GTEx. Prioritize targets that are overexpressed in tumors [30] [31].

- Prognostic Relevance: Assess the association between the target's expression and patient survival (Overall Survival, Progression-Free Interval) via TCGA data. Targets whose high expression correlates with poor prognosis are often ideal candidates [30].

- Hit Selection: Select top-ranking compounds that pass these filters for further experimental validation in GBM cellular models (e.g., patient-derived GBM stem cells) [30] [31].

Building and Applying High-Performance 3D-QSAR Models and Screening Workflows

Step-by-Step Guide to Developing CoMFA and CoMSIA Models with Exemplary Performance Metrics (R², Q²)

Integrating Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) models like Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) into virtual screening pipelines represents a powerful strategy for modern drug discovery, particularly for complex diseases like glioblastoma. These methods move beyond traditional 2D descriptors by quantifying how a molecule's three-dimensional steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields influence its biological activity [11]. The predictive models generated allow researchers to prioritize synthesis and testing toward compounds with higher predicted potency, significantly accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic candidates, including glioblastoma therapeutics [33]. This guide provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for developing robust CoMFA and CoMSIA models, complete with exemplary performance metrics and contextualized within glioblastoma research.

Theoretical Background

CoMFA, the pioneering 3D-QSAR method, calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies between a molecular ensemble and a probe atom at thousands of points in a regularly spaced grid [34] [11]. The core output is a model that visually maps regions where specific molecular properties enhance or diminish biological activity.

CoMSIA extends this concept by employing a Gaussian-type function to eliminate singularities and incorporate additional physicochemical properties. Beyond steric and electrostatic fields, CoMSIA typically evaluates hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields [34] [11]. This provides a more holistic view of ligand-target interactions and is often more robust to minor alignment discrepancies.

The statistical engine for both methods is Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, which correlates the vast descriptor matrix with biological activity data (e.g., IC₅₀, pIC₅₀) [35] [11]. Model quality is judged by several key metrics: R² (non-cross-validated correlation coefficient) indicates the goodness-of-fit, Q² (cross-validated correlation coefficient, typically via Leave-One-Out) measures internal predictive ability, and R²ᵩᵣₑ𝒹 (predicted R²) validates the model against an external test set [36] [35].

Step-by-Step Protocol for Model Development

Step 1: Data Set Curation and Preparation

- Activity Data Collection: Assemble a congeneric series of compounds (typically 20-50) with consistent, experimentally determined biological activity values (e.g., IC₅₀) from a uniform assay. For glioblastoma research, this could involve activity against glioblastoma cell lines or specific targets like CHI3L1 or VEGFA [13] [20].

- Activity Conversion: Convert IC₅₀ values to pIC₅₀ (−log₁₀IC₅₀) for a more linear relationship with free energy changes.

- Data Set Division: Split the data set into a training set (~80%) for model development and a test set (~20%) for external validation. Ensure both sets represent a wide range of activity and structural diversity. The test set compounds should be excluded from the model building process [36].

Step 2: Molecular Modeling and Conformational Analysis

- 3D Structure Generation: Build 3D molecular structures from 2D representations using software like SYBYL/X or RDKit [37] [36].

- Geometry Optimization: Minimize molecular energy using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., Tripos Force Field) with Powell's method and calculate partial atomic charges (e.g., Gasteiger-Hückel) [37] [36] [35].

- Active Conformation Selection: For ligand-based approaches, identify a low-energy bioactive conformation, often from the most active compound, via systematic or grid searches [37].

Step 3: Molecular Alignment

Alignment is a critical step that assumes all compounds share a similar binding mode. Several strategies exist:

- Common Substructure-Based: Align molecules based on a shared scaffold or maximum common substructure (MCS) identified from the training set [35] [11].

- Database Alignment: Use a module in software like SYBYL to automatically align molecules to a template structure [35].

- Pharmacophore-Based: Use a hypothesized or known pharmacophore model for alignment.

- Protein-Based (if structure available): Superimpose molecules based on their docked conformations within the target's binding site [34].

Step 4: Descriptor Field Calculation

Place the aligned molecules inside a 3D grid that extends typically 4 Å beyond the molecular dimensions in all directions. A grid spacing of 2.0 Å is standard [35].

- CoMFA Descriptors:

- CoMSIA Descriptors:

Step 5: Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis and Model Validation

- PLS Regression: Use the PLS algorithm to correlate the field descriptors (independent variables) with the biological activity (dependent variable). The goal is to determine the Optimal Number of Components (ONC) that maximizes predictivity without overfitting [35].

- Internal Validation:

- External Validation:

- Model Fitness: Calculate the non-cross-validated correlation coefficient R² and the Standard Error of Estimate (SEE). A high R² and low SEE indicate a good fit to the training set data [36].

Step 6: Model Interpretation and Application

- Contour Map Analysis: Visualize the results as 3D contour maps. These maps show regions where specific molecular properties are favorably or unfavorably associated with biological activity.

- Design New Compounds: Use the contour maps as a guide to design new analogs. Introduce bulky groups in green steric regions, or electron-withdrawing groups in red electrostatic regions, to potentially enhance activity [37] [11].

- Virtual Screening: The validated model can be used to predict the activity of virtual compound libraries, prioritizing high-scoring candidates for synthesis and biological testing in glioblastoma models [13] [33].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps in developing CoMFA and CoMSIA models.

Exemplary Performance Metrics from Case Studies

The table below summarizes performance metrics from published 3D-QSAR studies, providing benchmarks for successful models.

Table 1: Exemplary Performance Metrics from 3D-QSAR Case Studies

| Study Context | Model Type | Training Set (n) | Test Set (n) | Q² | R² | R²ᵩᵣₑ𝒹 | ONC | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pteridinones as PLK1 Inhibitors (Anti-cancer) | CoMFA | 22 | 6 | 0.67 | 0.992 | 0.683 | * | [36] |

| CoMSIA/SEAH | 22 | 6 | 0.66 | 0.975 | 0.767 | * | [36] | |

| 1,2-dihydropyridine derivatives (Anti-cancer) | CoMFA/CoMSIA | 30 | 5 | 0.70/0.639 | * | 0.65/0.61 | * | [37] |

| Ionone-based Chalcones (Anti-prostate cancer) | CoMFA | 33 | 10 | 0.527 | 0.636 | 0.621 | * | [35] |

| CoMSIA | 33 | 10 | 0.550 | 0.671 | 0.563 | * | [35] |

Information not provided in the source material.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Essential Tools and Software for CoMFA/CoMSIA Modeling

| Tool Category | Example | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling & QSAR Suites | SYBYL/X (Tripos) | Industry-standard software for comprehensive 3D-QSAR, including structure building, alignment, CoMFA/CoMSIA, and PLS analysis [37] [36] [35]. |

| Open-Source Tools (e.g., RDKit, PyMOL) | For generating 3D structures, performing molecular alignments, and visualizing final contour maps [33] [11]. | |

| Cheminformatics & Scripting | Python (with libraries like scikit-learn) | For data preprocessing, descriptor management, and implementing custom machine-learning algorithms alongside classical QSAR [33]. |

| Validation & Analysis | Built-in PLS & Statistical Modules | For performing leave-one-out cross-validation, external validation, and calculating key metrics (Q², R², R²ᵩᵣₑ𝒹) [36] [35]. |

Application in Glioblastoma Therapeutic Research

The application of 3D-QSAR is highly relevant in glioblastoma research, where identifying new therapeutic options is urgent. For instance, virtual screening guided by structure-based pharmacophore models has successfully identified novel small-molecule binders of CHI3L1, a promising glycoprotein target in glioblastoma, with binding affinity validated by biophysical methods [13] [26]. Similarly, 3D-QSAR models can be built around inhibitors of other glioblastoma-relevant targets like VEGFA, which was targeted in a virtual screening study that discovered novel inhibitors with potential to overcome drug resistance [20]. By applying the CoMFA/CoMSIA protocol outlined above to datasets of compounds screened against glioblastoma cell lines or specific molecular targets, researchers can efficiently optimize lead compounds and contribute to the development of much-needed therapies.

The integration of advanced machine learning (ML) algorithms with Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling has significantly accelerated the discovery of novel therapeutics, particularly for complex diseases like glioblastoma. Traditional QSAR approaches, while valuable, often struggle with the nonlinear relationships between molecular structure and biological activity in large, complex chemical spaces. The incorporation of ML techniques such as Extra Trees Regressor (ETR) and Gene Expression Programming (GEP) has demonstrated remarkable improvements in predictive accuracy and model interpretability for virtual screening applications. These methods enable researchers to efficiently identify and optimize lead compounds by leveraging both labeled and unlabeled chemical data, which is particularly valuable in glioblastoma research where experimental data can be scarce and expensive to obtain [38]. This protocol details the application of ETR and GEP in building robust QSAR models within a virtual screening pipeline for glioblastoma therapeutic development, providing researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these powerful computational approaches.

Theoretical Foundation and Key Algorithms

Machine Learning-Enhanced QSAR Framework

QSAR modeling quantitatively correlates molecular descriptors with biological activity using mathematical and statistical methods. The integration of machine learning has transformed QSAR from traditional linear models like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) to advanced algorithms capable of capturing complex, nonlinear relationships [33]. This evolution is particularly crucial for targeting protein kinases and other complex biological targets relevant to glioblastoma, where selectivity and overcoming resistance mechanisms are significant challenges [39].

The predictive performance of ML-QSAR models depends heavily on appropriate molecular descriptors that encode various chemical, structural, and physicochemical properties. These descriptors range from 1D (molecular weight) to 2D (topological indices), 3D (molecular shape), and even 4D descriptors that account for conformational flexibility [33]. For glioblastoma research, where blood-brain barrier permeability is essential, descriptors related to molecular polarity, size, and charge distribution are particularly important for predicting central nervous system exposure.

Extra Trees Regressor Algorithm

Extra Trees Regressor (ETR) is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs the average prediction of the individual trees. Key characteristics include:

- Random Feature Selection: At each split, ETR randomly selects a subset of features, reducing variance and computational complexity.

- Bootstrap Aggregation: Utilizes the entire dataset rather than bootstrap samples, further decreasing variance.

- Uncorrelated Trees: The randomness in feature selection produces largely uncorrelated trees, enhancing ensemble performance.

ETR demonstrates particular strength in handling high-dimensional descriptor spaces and noisy data, common challenges in chemoinformatics [14] [40].

Gene Expression Programming Framework

Gene Expression Programming (GEP) is a evolutionary algorithm that evolves computer programs of different sizes and shapes encoded in linear chromosomes. Unlike traditional regression methods, GEP automatically generates mathematical expressions that describe structure-activity relationships without pre-specified model forms [41]. Key advantages include:

- Nonlinear Modeling: Naturally captures complex nonlinear relationships between descriptors and activity.

- Interpretable Results: Produces explicit mathematical formulas that provide mechanistic insights.

- Feature Selection: Inherently identifies the most relevant molecular descriptors through the evolutionary process.

GEP has demonstrated superior performance over linear methods for modeling complex biological activities, particularly in cancer drug discovery [41].

Case Study 1: Extra Trees Regressor for ASAH1 Inhibitors in Glioblastoma

Background and Objective

Acid ceramidase (ASAH1) has emerged as a promising therapeutic target in glioblastoma due to its role in regulating ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate balance. Inhibition of ASAH1 elevates ceramide levels, inducing apoptosis in glioblastoma cells [14]. This case study demonstrates the application of ETR-QSAR modeling to identify novel ASAH1 inhibitors with improved efficacy and stability profiles compared to existing compounds like carmofur.

Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Data Curation and Preparation

- Compound Collection: Curate 103 ASAH1 inhibitors with experimental IC50 values from ChEMBL database.

- Data Standardization: Apply rigorous filtering to remove compounds with ambiguous activity measurements or structural errors.

- Activity Conversion: Convert IC50 values to pIC50 (-logIC50) for normalized distribution.

- Dataset Splitting: Implement random stratified splitting (70:15:15) for training, validation, and test sets.

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- Descriptor Generation: Compute 431 3D molecular descriptors using RDKit or PaDEL descriptor software.

- Descriptor Filtering: Apply variance thresholding and remove highly correlated descriptors (r > 0.95).

- Data Normalization: Standardize descriptors to zero mean and unit variance using z-score normalization.

Step 3: ETR Model Training and Optimization

- Parameter Grid Definition:

- nestimators: [100, 200, 500]

- maxdepth: [10, 20, None]

- minsamplessplit: [2, 5, 10]

- minsamplesleaf: [1, 2, 4]

- max_features: ['auto', 'sqrt', 'log2']

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Implement 5-fold cross-validation with Bayesian optimization for 100 iterations.

- Model Training: Train ETR with optimal parameters on full training set.

Step 4: Model Validation

- Internal Validation: Calculate leave-one-out (Q2(LOO) = 0.792) and leave-many-out (Q2(LMO) = 0.769) cross-validation metrics.

- External Validation: Evaluate model on held-out test set (R² = 0.867, RMSE = 0.248).

- Applicability Domain: Define using leverage approach and Williams plot to identify interpolation space.

Step 5: Virtual Screening and Compound Prioritization

- Database Screening: Apply trained model to screen ZINC15 library (~1 million compounds).

- ADMET Prediction: Filter top candidates using SwissADME and pkCSM for blood-brain barrier penetration and toxicity profiles.

- Molecular Dynamics Validation: Perform 100ns MD simulations with MM/PBSA binding free energy calculations for top candidate (N-hexylsalicylamide).

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ETR Model for ASAH1 Inhibition Prediction

| Validation Method | R² Score | RMSE | MAE | Q² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Fold CV | 0.841 | 0.291 | 0.225 | 0.801 |

| Leave-One-Out CV | 0.829 | 0.301 | 0.234 | 0.792 |

| External Test Set | 0.867 | 0.248 | 0.191 | - |

Table 2: Key Molecular Descriptors Identified by SHAP Analysis

| Descriptor | SHAP Value Impact | Chemical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RDF20s | 0.324 | Radial Distribution Function describing molecular geometry |

| DPSA-1 | 0.287 | Charged partial surface area related to polarity |

| TDB2p | 0.251 | 3D topological descriptor capturing molecular branching |

| MW | 0.198 | Molecular weight influencing membrane permeability |

| LogP | 0.176 | Lipophilicity affecting cellular uptake |

Results and Implementation Workflow

The ETR model successfully identified N-hexylsalicylamide as a promising ASAH1 inhibitor candidate with superior predicted binding affinity compared to carmofur. SHAP analysis revealed that radial distribution function descriptors (RDF20s) and charged partial surface area (DPSA-1) were the most significant determinants of inhibitory activity, providing actionable insights for further structural optimization. The candidate demonstrated favorable ADMET properties, including predicted blood-brain barrier penetration essential for glioblastoma therapy [14].

Case Study 2: Gene Expression Programming for Osteosarcoma Therapeutics

Background and Objective

While this case study focuses on osteosarcoma, the methodological framework is directly applicable to glioblastoma research, particularly for optimizing compound series with complex structure-activity relationships. The study addressed the challenge of predicting IC50 values for 2-Phenyl-3-(pyridin-2-yl) thiazolidin-4-one derivatives with potent antiproliferative activity [41]. GEP was employed to capture nonlinear relationships that traditional linear QSAR methods failed to adequately model.

Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Dataset Preparation

- Compound Set: 39 compounds with experimental IC50 values against osteosarcoma cell lines.

- Activity Transformation: Convert IC50 to pIC50 (-logIC50) for normalized distribution.

- Data Splitting: Random allocation of 31 compounds to training set and 8 to test set.

Step 2: Descriptor Calculation and Selection

- Descriptor Generation: Calculate 2D molecular descriptors using CODESSA PRO software.

- Heuristic Reduction: Apply correlation-based feature selection to identify most relevant descriptors.

- Final Descriptor Set: 4 key descriptors identified through iterative refinement.

Step 3: GEP Model Configuration

- Chromosome Structure: Set head size = 7, number of genes = 3.

- Function Set: {+, -, *, /, √, x², x³, exp, ln}

- Genetic Operators: Mutation rate = 0.1, inversion rate = 0.3, IS/RS transposition rate = 0.3.

- Population Evolution: Run for 5000 generations with population size = 100.

- Fitness Function: Minimize mean squared error on training set predictions.

Step 4: Model Validation and Interpretation

- Internal Validation: Calculate R² and Q² for training set performance.

- External Validation: Evaluate predictive performance on test set compounds.

- Model Interpretation: Analyze evolved mathematical expression for mechanistic insights.

Step 5: Virtual Compound Design

- Scaffold Optimization: Use GEP-derived equation to guide structural modifications.

- Activity Prediction: Apply model to newly designed analogs for activity prioritization.

- Synthetic Planning: Select top candidates for synthesis based on predicted potency and synthetic accessibility.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of GEP vs. Linear QSAR Models

| Model Type | Training R² | Training Q² | Test R² | Test RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear QSAR | 0.603 | 0.482 | 0.554 | 0.307 |

| GEP Model | 0.839 | 0.760 | 0.801 | 0.157 |

Table 4: Key Descriptors in GEP Osteosarcoma Model

| Descriptor | Relative Importance | Role in Bioactivity |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO-LUMO Gap | 0.381 | Electronic properties influencing target interaction |

| Molecular Polarizability | 0.295 | Membrane permeability and binding affinity |

| Topological Complexity | 0.227 | Molecular shape complementarity with target |

| Hydrophobic Surface Area | 0.197 | Solubility and cellular uptake characteristics |

Results and Implementation Workflow

The GEP approach significantly outperformed traditional linear QSAR, achieving R² values of 0.839 and 0.760 for training and test sets respectively, compared to 0.603 and 0.554 for the linear model [41]. The evolved mathematical expression provided interpretable insights into the nonlinear relationships between molecular descriptors and antiproliferative activity, enabling rational design of novel analogs with predicted enhanced potency. This methodology demonstrates particular value for optimizing lead series in glioblastoma drug discovery where complex structure-activity relationships often challenge traditional QSAR approaches.

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-QSAR Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Application Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem | Source of bioactive compounds and experimental IC50 values | Publicly available |

| Descriptor Calculation | RDKit, PaDEL, DRAGON | Generation of molecular descriptors from compound structures | Open-source and commercial |

| Machine Learning Libraries | scikit-learn, XGBoost | Implementation of ETR, GEP, and other ML algorithms | Open-source |

| Model Interpretation | SHAP, LIME | Explainable AI for feature importance analysis | Open-source |

| Molecular Modeling | GROMACS, AMBER | Molecular dynamics simulations and binding free energy calculations | Academic licensing available |

| ADMET Prediction | SwissADME, pkCSM | Prediction of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity | Web-based and open-source |

| Cloud Platforms | Google Colab, AWS | Computational resources for intensive ML-QSAR calculations | Commercial with free tiers |

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

The integration of machine learning algorithms like Extra Trees Regressor and Gene Expression Programming with QSAR modeling represents a transformative advancement in virtual screening for glioblastoma therapeutics. The case studies presented demonstrate that these methods significantly enhance predictive accuracy and provide interpretable insights that guide rational drug design. ETR excels in handling high-dimensional descriptor spaces and identifying complex feature interactions, while GEP automatically discovers nonlinear structure-activity relationships through evolutionary computation.

Future developments in ML-QSAR will likely focus on semi-supervised approaches that leverage both labeled and unlabeled data [38], multi-task learning for polypharmacology prediction, and integration with deep learning architectures for enhanced feature representation. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating the discovery of effective glioblastoma therapies, ultimately contributing to improved outcomes for this devastating disease.

Leveraging Contour Maps and Key Descriptors for Rational Compound Design and Scaffold Hopping

Glioblastoma (GBM) remains one of the most aggressive primary brain malignancies with a dismal prognosis, necessitating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents [26] [42]. In this context, virtual screening using three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) models has emerged as a powerful strategy for accelerating drug discovery. These computational approaches are particularly valuable for designing blood-brain barrier (BBB)-permeant compounds and overcoming treatment resistance through multi-targeting strategies [42]. The integration of contour map analysis with key molecular descriptors provides a rational framework for compound optimization and scaffold hopping—the strategic replacement of core molecular structures while preserving biological activity [9] [43]. This application note details protocols for leveraging these computational techniques specifically for glioblastoma therapeutic research, enabling researchers to efficiently identify and optimize novel drug candidates with improved efficacy and pharmacokinetic properties.

Computational Methodologies and Key Descriptors

3D-QSAR Model Development

The foundation of rational compound design lies in robust 3D-QSAR models, particularly Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA). These methods establish correlations between molecular fields and biological activity through the following process: