Absolute Quantification of Oncogene Expression by qPCR: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomarker Validation and Precision Oncology

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing absolute quantification methods in qPCR for precise measurement of oncogene expression.

Absolute Quantification of Oncogene Expression by qPCR: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomarker Validation and Precision Oncology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing absolute quantification methods in qPCR for precise measurement of oncogene expression. It covers the foundational principles that distinguish absolute from relative quantification, detailing why this is critical for reproducible cancer biomarker research. The content explores established and novel methodological approaches, including the standard curve and Single Standard for Marker and Reference (SSMR) methods, alongside digital PCR. A strong emphasis is placed on troubleshooting and optimization to overcome common pitfalls like amplification efficiency variability and suboptimal primer design. Finally, the article validates these techniques through comparative analysis with RNA-Seq and digital PCR, highlighting their indispensable role in clinical applications such as minimal residual disease monitoring and the development of robust prognostic models.

Why Absolute Quantification? Establishing the Need for Precision in Oncology

In the field of oncology research, accurate quantification of gene expression is paramount. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) serves as a gold standard technique for detecting and quantifying nucleic acids, with its utility broadly divided into two methodological approaches: absolute and relative quantification [1] [2]. The choice between these methods has profound implications for data comparability, interpretation, and subsequent scientific conclusions, particularly in sensitive applications like oncogene expression profiling. Absolute quantification provides concrete copy numbers of a target sequence, while relative quantification expresses changes relative to a control sample [3] [4]. This article delineates the core concepts, applications, and practical protocols for both methods, framed within the context of oncogene research.

Core Conceptual Distinctions

The fundamental distinction between absolute and relative quantification lies in the nature of the result. Absolute quantification determines the exact number of target DNA or RNA molecules in a sample, expressed as copy number, mass, or concentration [3] [4]. This method requires a calibration curve from standards of known concentration. In contrast, relative quantification measures the change in target gene expression in a test sample relative to a reference sample (calibrator), typically normalized to one or more reference genes, and reports the result as a fold-change [3] [5].

This core difference dictates their respective applications. Absolute quantification is indispensable in virology (e.g., determining viral load), microbiology (e.g., quantifying microbial adulterants), and clinical diagnostics where a precise numerical value is critical [1]. Relative quantification is the preferred method in functional genomics and transcriptomics, where the primary interest lies in understanding changes in gene expression under different experimental conditions, such as comparing oncogene expression levels between tumor and normal tissue [3] [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between Absolute and Relative Quantification

| Feature | Absolute Quantification | Relative Quantification |

|---|---|---|

| Output | Exact copy number or concentration | Fold-change relative to a calibrator |

| Standard Requirement | External standards with known concentration | Internal reference/reference gene(s) |

| Primary Application | Viral load, microbiological count, copy number variation | Differential gene expression studies |

| Key Assumption | Standard and target amplify with equal efficiency | Reference gene expression is stable across samples |

| Data Normalization | Not required; result is intrinsic | Essential; normalized to reference gene(s) |

Methodological Approaches and Protocols

Absolute Quantification Protocols

Protocol 1: Absolute Quantification Using the Standard Curve Method

This is the most common method for absolute quantification in qPCR [3] [4].

- Standard Preparation: Generate a serial dilution (at least 5 points, 10-fold recommended) of a standard with a known concentration. The standard must be identical or highly similar to the target in terms of amplicon sequence, length, and amplification efficiency [4] [6]. Common standards include:

- Plasmid DNA: Clone the target amplicon into a plasmid. Linearize the plasmid before use. Quantify concentration via spectrophotometry (A260) and calculate copy number using the formula: (X g/µl DNA / [plasmid length in bp x 660]) x 6.022 x 10²³ = Y molecules/µl [4].

- In vitro Transcribed RNA: For mRNA quantification, use RNA standards to account for reverse transcription efficiency. After DNase treatment to remove plasmid DNA, quantify by A260 and calculate copy number with: (X g/µl RNA / [transcript length in nucleotides x 340]) x 6.022 x 10²³ = Y molecules/µl [4].

- qPCR Run: Amplify the standard dilution series and the unknown samples in the same run.

- Standard Curve Generation: Plot the Ct values of the standards against the logarithm of their known concentrations. The software will generate a line of best fit with a slope and R² value.

- Calculation of Unknowns: The qPCR software interpolates the Ct value of the unknown sample against the standard curve to determine its absolute concentration.

Critical Guidelines: The DNA/RNA standard must be pure and accurately quantified. Pipetting for serial dilutions must be precise. Diluted standards should be aliquoted and stored at -80°C to avoid degradation [3].

Protocol 2: The One-Point Calibration (OPC) Method

The standard curve method assumes the amplification efficiency (E) of the standard and the sample are identical, which can lead to significant quantification errors if false [6]. The OPC method corrects for these differences.

- Efficiency Determination: Determine the amplification efficiency (E) for each sample from the fluorescence data using the linear regression method on the dilution series or other software algorithms [5] [6].

- Calibration Point: Use a single known standard concentration.

- Calculation: The target concentration in the sample (N0,sample) is calculated relative to the standard (N0,standard) using the formula: N0,sample = N0,standard × (Estandard)^(Ct,standard) / (Esample)^(Ct,sample) This method has been shown to provide higher accuracy when sample and standard efficiencies differ [6].

Relative Quantification Protocols

Protocol 3: The Comparative Cт (ΔΔCт) Method

This method, popularized by Livak and Schmittgen, is simple but relies on a critical assumption [5] [7].

- Validation Experiment: Before proceeding, it must be verified that the amplification efficiencies of the target gene and the reference gene are approximately equal (within 5%) and close to 100% (E ≈ 2) [5]. This is done by generating a standard curve for both genes with a serial dilution of cDNA. The slope of the curve should be <-3.1 or >-3.6, with an efficiency between 90-110% [5].

- qPCR Run: Amplify the target gene and reference gene for all test and calibrator samples. This can be done in separate wells or, with optimization, in a multiplex reaction.

- Calculation:

Protocol 4: The Pfaffl Method (Efficiency-Corrected Calculation)

When the amplification efficiencies of the target (Etarget) and reference (Eref) genes are not equal, the Pfaffl method must be employed for accurate results [5] [7].

- Efficiency Determination: Calculate the amplification efficiency for both the target and reference gene primers from standard curves as described in Protocol 3 [5].

- qPCR Run: As in Protocol 3.

- Calculation:

This method is more robust as it incorporates actual reaction efficiencies, making it the preferred choice for rigorous gene expression studies, including oncogene research [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Relative Quantification Calculation Methods

| Aspect | Comparative Cт (ΔΔCт) Method | Pfaffl Method |

|---|---|---|

| Core Formula | 2^–ΔΔCт | (Etarget)^(ΔCтtarget) / (Eref)^(ΔCтref) |

| Key Assumption | Etarget = Eref ≈ 2 (100% efficiency) | Accounts for different Etarget and Eref |

| Validation Need | Must demonstrate equal efficiency | Must determine precise efficiency for both genes |

| Advantage | Simplicity, no standard curve needed | Accuracy, flexible for suboptimal efficiencies |

| Limitation | Inaccurate if efficiency assumption is violated | Requires more initial validation and setup |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for qPCR Quantification

| Reagent/Material | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Gene Primers | Normalization control in relative quantification. | Must exhibit stable expression across all experimental conditions. Validation with algorithms like geNorm or NormFinder is crucial [5] [2]. |

| Validated Primers/Probes | Specific amplification and detection of the target oncogene. | High amplification efficiency (90-110%), specificity confirmed by melt curve or probe detection. |

| Standard (Plasmid DNA/RNA) | For generating the standard curve in absolute quantification. | Sequence identity to target, accurate initial quantification, and purity are essential [4]. |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Converts RNA to cDNA for gene expression studies. | Consistent efficiency is critical; use the same kit and protocol for all samples in a study. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer for amplification. | Choice of chemistry (SYBR Green vs. TaqMan) depends on need for specificity and multiplexing. |

| Low-Binding Tubes & Tips | Handling of standards and samples, especially for digital PCR. | Prevents loss of low-concentration nucleic acids by adhesion to plastics, reducing variability [3]. |

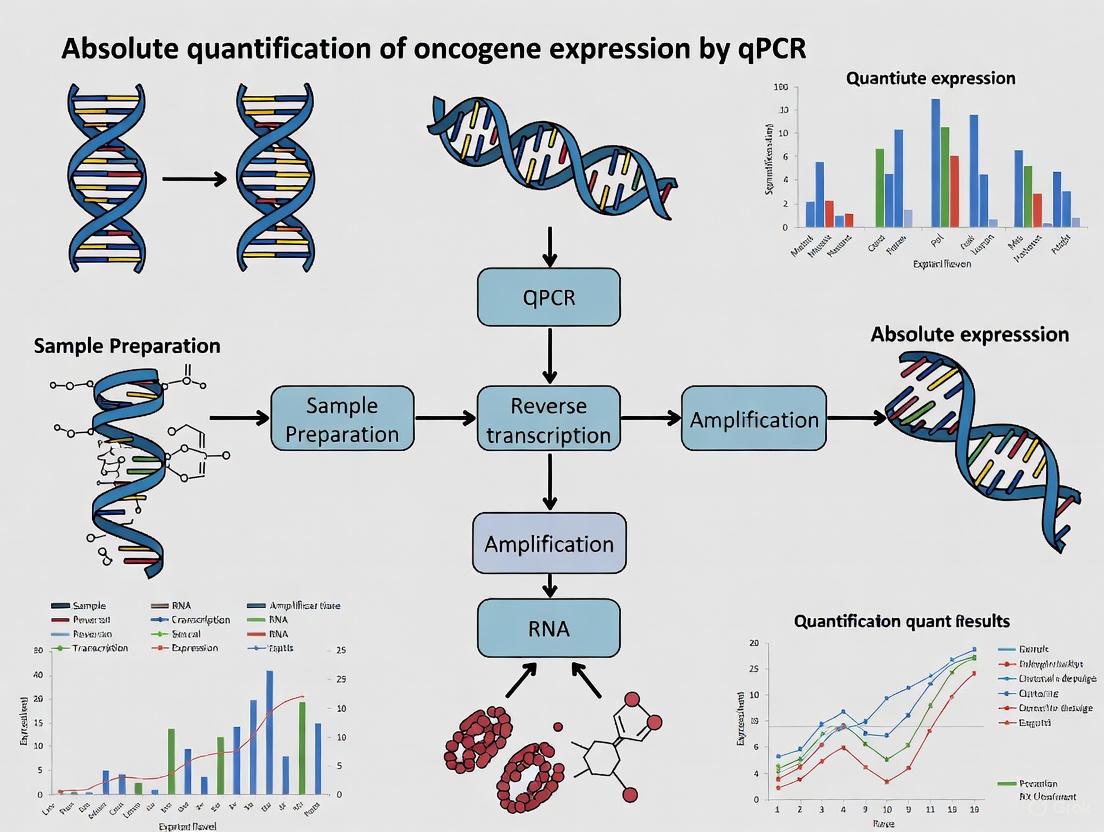

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting and executing the appropriate quantification method in a qPCR experiment, such as one designed to measure oncogene expression.

qPCR Quantification Method Decision Workflow

Implications for Data Comparability in Oncogene Research

The choice of quantification method directly impacts the nature and comparability of data in oncogene research. Absolute quantification provides a concrete value, such as the number of HER2 transcripts per nanogram of RNA, which can be directly compared across laboratories if standards are harmonized [4]. However, its accuracy is entirely dependent on the quality and accuracy of the external standards.

Relative quantification, while not providing an absolute number, is often more practical for studying expression changes, for instance, in response to a drug treatment. The fold-change result is robust against variations in sample input and RNA quality, as these are normalized by the reference gene [3] [5]. The primary challenge for data comparability here lies in the selection and validation of stable reference genes. Using an inappropriate reference gene whose expression varies with the experimental condition (e.g., a housekeeping gene affected by the cancer phenotype) is a major source of error and invalidates any comparative analysis [5] [2]. It is therefore strongly recommended to validate multiple candidate reference genes and use a geometric mean of several stable genes for normalization [5].

Furthermore, the mathematical approach (ΔΔCт vs. Pfaffl) influences comparability. Data generated using the ΔΔCт method under non-validated efficiency conditions are not comparable to data generated with the more rigorous, efficiency-corrected Pfaffl method [5] [7] [6]. For credible and comparable results in oncogene research, the Pfaffl method is generally advised. Modern statistical packages in R, such as the rtpcr package, facilitate the implementation of these efficiency-corrected models and robust statistical testing, thereby enhancing data reliability and comparability [7].

Both absolute and relative quantification are powerful tools in the molecular oncologist's arsenal. Absolute quantification is unmatched when a definitive copy number is required, but demands scrupulous attention to standard preparation. Relative quantification, particularly the efficiency-corrected Pfaffl method, offers a robust and practical framework for the majority of gene expression studies, such as tracking oncogene modulation. The key to generating comparable, high-quality data lies in transparent reporting of the methods, rigorous validation of reagents (especially reference genes), and the use of appropriate, efficiency-informed calculation models. By adhering to these detailed protocols and understanding the implications of each methodological choice, researchers can ensure their qPCR data on oncogene expression is both reliable and meaningful.

The pursuit of personalized oncology hinges on the discovery and rigorous validation of molecular biomarkers that can accurately predict disease progression and therapeutic response. Within this paradigm, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) has emerged as a cornerstone technology for the absolute quantification of oncogene expression, enabling the transition of research findings from the laboratory to the clinical setting. The establishment of reliable prognostic models is critically dependent on the initial identification of candidate genes and their subsequent validation through precise experimental methodologies. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for this multi-faceted process, providing researchers with a structured framework for biomarker development. The following sections detail the integrative bioinformatics and experimental pipeline, from high-throughput data analysis to final qPCR validation, with a specific focus on hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and breast cancer (BC) as exemplars [8] [9].

Biomarker Discovery & Integrative Bioinformatics Analysis

The initial phase of prognostic model development involves the identification of candidate genes from large-scale transcriptomic datasets.

Data Acquisition and Processing

- Data Sources: Transcriptomic, clinical, survival, and mutation data should be sourced from public repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [8] [9]. For example, the TCGA-HCC dataset includes 363 HCC and 49 normal samples, while the TCGA-BRCA dataset includes 1,096 BC and 113 normal samples [8] [9].

- Gene Lists: Curate disease-specific gene sets from published literature, such as 200 epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related genes (EMTRGs) and 35 anoikis-related genes (ARGs) for HCC, or 781 cytochrome c-related genes (CCRGs) for breast cancer [8] [9].

Identification of Candidate Genes

A multi-step analytical approach is employed to filter and identify robust candidate genes, as visualized in the workflow below.

Diagram 1: Bioinformatics workflow for biomarker discovery.

The key steps involve:

- Differential Expression Analysis: Utilizing tools like DESeq2 to identify genes significantly differentially expressed between tumor and normal tissues (e.g., |log2 Fold Change| > 0.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.05) [8] [9].

- Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA): Constructing a co-expression network to identify modules of highly correlated genes significantly associated with clinical traits of interest, such as EMT or anoikis scores [8].

- Candidate Gene Selection: Selecting the overlapping genes from the differential expression analysis and the key modules identified by WGCNA as high-priority candidates for further analysis [8].

- Prognostic Model Construction: Applying univariate Cox regression and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) analysis to the candidate genes to build a multi-gene signature for prognosis prediction [9].

Functional Enrichment Analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses are performed on the candidate genes using the clusterProfiler package to elucidate their biological functions and involvement in cancer-related pathways [8] [9].

Absolute quantification by RT-qPCR is a critical technique for validating the expression levels of identified biomarkers, providing a precise measure of transcript copy number in a sample.

Core Principles and Workflow

The process involves converting RNA to cDNA, followed by qPCR amplification with reference to an absolute standard curve. The key components of the qPCR amplification curve are illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Phases of a qPCR amplification curve.

- Baseline: The initial cycles where fluorescence is background noise [10].

- Exponential Phase: The phase where amplification is most efficient and reproducible [10].

- Threshold: The fluorescence level set above the baseline to define the Ct value [10].

- Ct (Cycle Threshold): The cycle number at which the sample's fluorescence intersects the threshold; it is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target transcript [10].

- Plateau Phase: The final phase where reaction components become limited and amplification efficiency drops [10].

Absolute vs. Relative Quantification

The choice between absolute and relative quantification depends on the research question.

Table 1: Comparison of qPCR Quantification Methods

| Feature | Absolute Quantification | Relative Quantification |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Question | How many target transcripts are in the sample? [10] | What is the fold-change in gene expression between samples? [10] |

| Requirement | A standard curve with known copy numbers [10] | A stable reference gene (e.g., Actin, GAPDH) [10] |

| Key Output | Exact copy number of the target gene [10] | Fold-change (e.g., 2.5x upregulation) [10] |

| Common Use Cases | Viral load testing, determining gene copy number [10] | Gene expression studies, developmental biology, diagnostic research [10] |

Experimental Protocol: Absolute Quantification for Biomarker Validation

This protocol is designed to validate the expression of prognostic genes, such as STMN1 and SF3B4 in HCC or CETP and PLAU in breast cancer, using absolute quantification by RT-qPCR [8] [9].

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

- Obtain matched tumor and adjacent normal tissue samples from patients, with informed consent.

- Extract total RNA using a commercial kit, ensuring an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8.0 for high-quality samples.

- Quantify RNA concentration and purity using a spectrophotometer (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0).

cDNA Synthesis

- Use 1 µg of total RNA for reverse transcription with a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit.

- Include a no-reverse transcriptase control (-RT) for each sample to assess genomic DNA contamination.

Standard Curve Preparation for Absolute Quantification

- Clone Target Sequence: Clone the PCR amplicon of the target gene (e.g., STMN1) into a plasmid vector.

- Linearize Plasmid: Linearize the purified plasmid to facilitate in vitro transcription.

- In Vitro Transcription: Synthesize RNA from the linearized template using a T7 or SP6 RNA polymerase kit.

- Purify and Quantify RNA: Purify the transcript and determine its concentration accurately using a fluorometer. Calculate the copy number using the formula:

Copy number/µL = (Concentration (g/µL) / (Transcript length (bp) × 660)) × 6.022 × 10^23 - Create Serial Dilutions: Perform a 10-fold serial dilution of the RNA standard (e.g., from 10^7 to 10^1 copies/µL) in nuclease-free water. Use these to generate the standard curve in the qPCR run.

qPCR Reaction Setup and Data Acquisition

- Reaction Mix: Prepare reactions in triplicate for each standard, sample, and no-template control (NTC). A typical 20 µL reaction contains: 10 µL of 2X SYBR Green Master Mix, 1 µL of forward and reverse primer (10 µM each), 2 µL of cDNA (or standard RNA dilution), and 6 µL of nuclease-free water.

- Thermocycling Conditions:

- Step 1: 95°C for 10 minutes (polymerase activation)

- Step 2: 40 cycles of:

- 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation)

- 60°C for 1 minute (annealing/extension)

- Melting Curve Analysis: 65°C to 95°C, increment 0.5°C for 5 seconds.

Data Analysis and Validation

- Standard Curve and Efficiency: The qPCR software will generate a standard curve by plotting the Ct values against the log of the starting copy number. The slope of the curve is used to calculate PCR efficiency:

Efficiency (%) = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) × 100. An efficiency between 90% and 105% is considered optimal [10]. - Determine Unknowns: The software will interpolate the copy number in unknown samples from the standard curve.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare the absolute copy numbers of the target genes between tumor and normal groups using an unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05 [8] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR-based Biomarker Validation

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | For high-purity, intact total RNA isolation from tissue samples (e.g., TRIzol-based or column-based kits). |

| High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit | Contains all components (reverse transcriptase, buffers, dNTPs, random hexamers) for efficient synthesis of first-strand cDNA from RNA templates. |

| SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (2X) | A ready-to-use mix containing hot-start DNA polymerase, dNTPs, SYBR Green dye, and optimized buffer for robust and sensitive qPCR amplification. |

| Validated Primer Pairs | Target-specific forward and reverse primers designed to amplify a unique 75-200 bp region of the prognostic gene. Must be tested for specificity and efficiency. |

| In Vitro Transcription Kit | For generating large amounts of specific RNA transcripts from a DNA template to be used as standards for absolute quantification. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Certified free of nucleases to prevent degradation of RNA and cDNA samples during reaction setup. |

| Plasmid Vector System | For cloning the PCR amplicon to create a template for generating the absolute standard. |

Construction and Application of a Prognostic Risk Model

The validated gene expression data is instrumental in building models to predict patient outcomes.

Risk Score Calculation

A risk score for each patient is calculated using a formula derived from the multivariate Cox regression or LASSO analysis [9]:

Risk score = Σ (Coef_i × Expr_i)

Where Coef_i is the risk coefficient for gene i, and Expr_i is its expression level (e.g., the absolute copy number determined by qPCR).

Model Validation

- Patients are stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score or an optimal cutoff value.

- Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank tests are performed to assess the difference in overall survival between the two groups [8] [9].

- The predictive power of the model is evaluated using time-dependent Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for 1, 3, and 5-year survival [9].

Integration with Clinical Variables

A nomogram can be constructed to integrate the genetic risk score with key clinical parameters (e.g., TNM stage, age) to provide a quantitative tool for predicting individual patient survival probability [8] [9].

Signaling Pathways and Functional Mechanisms

The prognostic genes often cluster within key oncogenic pathways. For instance, in breast cancer, cytochrome c-related genes may be enriched in pathways like "cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction," which influences apoptosis, immune response, and cell proliferation [9]. The diagram below illustrates a simplified network of transcriptional regulation involving prognostic genes.

Diagram 3: Transcriptional network regulating prognostic genes.

In the field of oncology research, the absolute quantification of oncogene expression via quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) is a cornerstone for understanding tumorigenesis, patient stratification, and therapy development. The translational value of this research, however, is critically dependent on the achievement of two key types of comparability: sample-to-sample comparability within a single study and cross-study comparability across different laboratories and research initiatives. Inconsistencies in methodology and data analysis can lead to significant discrepancies in published results, undermining the reliability of molecular findings and their application in drug development. This application note details the standardized protocols and analytical frameworks essential for ensuring rigorous, reproducible, and comparable qPCR data in oncogene research.

The Critical Role of Housekeeping Gene Selection

A foundational element for achieving sample-to-sample comparability is the accurate normalization of target gene expression (e.g., oncogenes) against stably expressed internal controls, known as housekeeping genes (HKGs). The improper selection of HKGs is a major source of error and variability in qPCR data [11].

Pitfalls of Commonly Used Housekeeping Genes

Historically, genes like Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-actin (ACTB) have been used as HKGs based on the assumption of constitutive expression. However, extensive evidence now shows that this assumption is often flawed, particularly in cancer biology [11] [12]. GAPDH, for instance, is not a neutral control but a "pan-cancer marker" whose transcription is influenced by a multitude of factors including insulin, growth hormone, oxidative stress, and tumor protein p53 [11]. Its use for normalization in endometrial cancer and many other tissues is strongly discouraged [11]. Similarly, the expression of ACTB (a cytoskeletal protein) and genes encoding ribosomal proteins (e.g., RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A) can undergo dramatic changes in specific experimental conditions, such as in cancer cells treated with mTOR inhibitors, rendering them categorically inappropriate for normalization in those contexts [12].

Guidelines for Optimal HKG Selection

To ensure robust sample-to-sample comparability, the following practices are recommended:

- Validation is Mandatory: The stability of candidate HKGs must be empirically validated for each specific tissue type, cancer model, and experimental treatment [11] [12].

- Use Multiple HKGs: Relying on a single HKG is a high-risk strategy. Using a combination of at least two validated HKGs for normalization significantly improves the accuracy and reliability of gene expression recalculation [11].

- Identify Condition-Specific Optimal HKGs: Research has demonstrated that the optimal HKG can vary between different cancer cell lines. For example, in mTOR-inhibited A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells, B2M and YWHAZ were the most stable, whereas TUBA1A and GAPDH were best for T98G glioblastoma cells under the same conditions [12]. No single optimal HKG was identified for PA-1 ovarian teratocarcinoma cells, highlighting the necessity for line-specific validation [12].

Table 1: Stability of Candidate Housekeeping Genes in mTOR-Inhibited Cancer Cell Lines

| Cell Line | Most Stable HKGs | Unstable HKGs (to avoid) |

|---|---|---|

| A549 (Lung) | B2M, YWHAZ | ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A |

| T98G (Brain) | TUBA1A, GAPDH | ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A |

| PA-1 (Ovary) | Not determined (validation required) | ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A |

Technical Considerations for qPCR Data Analysis

The method of data analysis following qPCR amplification is another critical determinant of data quality and cross-study comparability.

Accurate Baseline and Threshold Setting

The initial cycles of a qPCR reaction establish the baseline fluorescence, which must be correctly defined to avoid distorting the quantification cycle (Cq) values. The baseline should be set within the early cycles where the fluorescence signal is stable and above any initial reaction stabilization artifacts [13]. The threshold, set within the exponential phase of all amplification plots, must be at a fixed fluorescence intensity for all samples in an experiment. Incorrect baseline or threshold settings can lead to significant inaccuracies in Cq values and, consequently, in fold-change calculations [13].

Choosing a Quantification Method

While the comparative Cq (2−ΔΔCT) method is widely used, its assumption of 100% amplification efficiency for all assays is a major limitation. Variability in amplification efficiency can introduce substantial errors [14]. Alternative methods offer improved accuracy:

- Efficiency-Adjusted Model (Pfaffl Model): This method incorporates the actual, experimentally determined PCR efficiency for each assay, leading to more accurate relative quantification [13].

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA): A flexible linear modeling approach that offers greater statistical power and robustness compared to the 2−ΔΔCT method and is not affected by variability in qPCR amplification efficiency [15].

- Relative Standard Curve Method: This method uses a serial dilution of a reference sample to create a standard curve, against which unknown samples are quantified. It has been shown to provide high accuracy [14].

Table 2: Comparison of qPCR Relative Quantification Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Cq (2−ΔΔCT) | Assumes perfect (100%) and equal PCR efficiency for all assays. | Simple, fast, no standard curve needed. | Prone to error if efficiency deviates from 100%. |

| Efficiency-Adjusted (Pfaffl) | Uses actual, calculated PCR efficiencies for target and reference genes. | More accurate than 2−ΔΔCT when efficiencies differ. | Requires determination of individual assay efficiencies. |

| Relative Standard Curve | Quantifies unknowns against a serial dilution standard curve. | High accuracy, does not assume equal efficiency. | Requires running additional standard curves. |

| ANCOVA | Uses a flexible multivariable linear model on raw fluorescence data. | High statistical power, robust to efficiency variance. | Requires raw fluorescence data and more complex analysis. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Validation of Housekeeping Gene Stability

This protocol is designed to identify the most stable HKGs for a specific experimental system.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- RNA Extraction Kit: For high-quality, genomic DNA-free total RNA.

- Reverse Transcription Kit: Includes reverse transcriptase, primers, and buffers for cDNA synthesis.

- qPCR Master Mix: Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBR Green).

- Primers: Validated, sequence-specific primers for all candidate HKGs and target oncogenes.

II. Procedure

- Experimental Design: Include a range of biological replicates that represent all experimental conditions (e.g., control vs. treated, different cancer cell lines, various tumor grades).

- RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis: Isolate total RNA from all samples, ensuring high purity (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8-2.0). Treat with DNase I to remove genomic DNA. Synthesize cDNA using a fixed amount of total RNA (e.g., 1 µg) per reaction.

- qPCR Run: Perform qPCR for all candidate HKGs (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB, B2M, YWHAZ, HPRT, etc.) across all cDNA samples. Include no-template controls (NTCs) for each primer set. Run reactions in technical duplicate or triplicate.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Cq values for each reaction. Use dedicated algorithms such as geNorm, NormFinder, or BestKeeper to analyze the Cq values and rank the candidate genes based on their expression stability (M-value in geNorm). A lower M-value indicates greater stability.

- Selection: Select the top two or three most stable genes for use in subsequent normalization of oncogene expression.

Protocol: Absolute Quantification of Oncogene Expression Using a Standard Curve

This protocol enables the determination of the exact copy number of an oncogene transcript.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Standard Template: A known quantity of purified PCR product, in vitro transcript, or plasmid containing the oncogene amplicon sequence.

II. Procedure

- Standard Curve Preparation: Prepare a serial dilution (e.g., 5-6 logs) of the standard template with known concentrations (e.g., copies/µL).

- qPCR Run: Amplify the standard dilutions alongside the experimental cDNA samples in the same qPCR run.

- Data Analysis:

- Generate a standard curve by plotting the Cq values of the standards against the logarithm of their known concentrations.

- Determine the PCR efficiency from the slope of the standard curve: Efficiency = [10(−1/slope)] - 1. Ideal efficiency is 90-110%.

- Use the linear equation from the standard curve to calculate the initial concentration (copy number) of the oncogene in each unknown sample.

- Normalization: Normalize the absolute oncogene copy number to the quantity and quality of input RNA. This is optimally achieved by also performing absolute quantification for the validated HKGs and expressing the oncogene data as a ratio (e.g., oncogene copies per copy of HKG).

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical workflows for the key protocols described.

Title: Workflow for validating housekeeping gene stability

Title: Workflow for absolute quantification using a standard curve

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for qPCR in Oncogene Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| DNase I Treatment Kit | Degrades contaminating genomic DNA during RNA preparation, preventing false-positive amplification. |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Converts purified mRNA into stable complementary DNA (cDNA) for use in qPCR amplification. |

| qPCR Master Mix (SYBR Green) | Provides all components necessary for the PCR reaction, including the fluorescent dye that intercalates with double-stranded DNA, allowing for real-time detection. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Short oligonucleotides designed to flank the target oncogene or HKG amplicon; critical for specificity and efficiency. |

| Validated HKGs | A panel of pre-tested primer sets for common housekeeping genes to facilitate the initial stability validation screen. |

| Standard Curve Template | A plasmid or purified amplicon of known concentration for generating standard curves in absolute quantification. |

Absolute quantification by qPCR is a powerful method that determines the exact copy number or concentration of a specific nucleic acid target, making it indispensable in oncogene expression studies for precise biomarker quantification and therapeutic monitoring [3] [4]. Unlike relative quantification, which expresses target amount as a ratio to a reference gene, absolute quantification relies on external standards of known concentration to generate a standard curve, enabling direct calculation of target copy numbers in experimental samples [3]. This precision is crucial in oncogene research where subtle expression differences may have significant clinical implications. However, two fundamental challenges critically impact the accuracy and reliability of this approach: significant variability in amplification efficiency across reactions and the complex, resource-intensive process of standard preparation [16]. This article addresses these challenges within the context of oncogene expression analysis, providing detailed protocols and analytical frameworks to enhance data quality and experimental reproducibility.

Challenges in Amplification Efficiency and Standard Preparation

Variability in Amplification Efficiency

Amplification efficiency (E) represents the proportion of template molecules amplified during each PCR cycle, ideally approaching 100% (doubling with each cycle) [17]. In practice, efficiency varies significantly due to multiple factors:

Primary Causes of Efficiency Variation:

- Sample-specific inhibitors that compromise polymerase activity [16]

- Reaction component quality including master mix performance and primer quality [17]

- Template quality and integrity, particularly critical for RNA templates in reverse transcription [4]

- Instrumentation and thermal uniformity across the sample block [18]

The exponential model of PCR amplification has been fundamentally challenged by sigmoidal analysis, which demonstrates that amplification efficiency is not constant but dynamically decreases as amplicon DNA accumulates throughout the reaction [16]. This understanding reframes efficiency as the maximal efficiency (Emax) generated at the onset of thermocycling, requiring revised approaches to efficiency determination and quantification mathematics.

Standard Preparation Complexities

Absolute quantification relies critically on the accuracy and stability of quantitative standards, presenting multiple preparation challenges:

Key Standard Preparation Challenges:

- Accurate initial quantification of stock nucleic acids, particularly vulnerable to contaminants that inflate spectrophotometric measurements [3]

- Precise serial dilution over several orders of magnitude (typically 106-1012-fold), requiring meticulous pipetting technique [3]

- Standard stability, especially for RNA standards which are prone to degradation [3] [4]

- Sequence identity between standards and target to ensure equivalent amplification efficiency [4]

The choice of standard type introduces specific considerations. Plasmid DNA offers production convenience but may not reflect reverse transcription efficiency when quantifying RNA targets. In vitro transcribed RNA standards address this limitation but require stringent DNase treatment to remove template DNA contamination [4]. Each standard type demands specific handling protocols to maintain quantitative integrity throughout the experimental workflow.

Quantitative Comparison of Efficiency Determination Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Amplification Efficiency Determination Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Resource Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Curve Method [16] | Positional analysis of serially diluted standards | Current gold standard; high quantitative reliability | Assumes equivalent efficiency in samples; resource intensive | High (multiple reactions per standard) |

| Log-Linear Region Analysis [16] | Exponential mathematics applied to amplification profile | Assesses individual reaction kinetics | Potentially large efficiency underestimations | Low (uses existing amplification data) |

| Linear Regression of Efficiency (LRE) [16] | Sigmoidal analysis of amplification profiles | Accounts for dynamic efficiency; correlates with standard curve | Requires high-quality fluorescence data; less established | Moderate (specialized analysis tools) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Amplification Efficiency via Standard Curve

Principle: This method determines amplification efficiency by analyzing the relationship between threshold cycle (Ct) values and the logarithm of known template concentrations in a serial dilution series [16] [17].

Procedure:

- Standard Preparation: Prepare a 5-10 point serial dilution (typically 10-fold dilutions) of your standard material (plasmid DNA containing oncogene insert or in vitro transcribed RNA)

- qPCR Amplification: Amplify the entire dilution series using the same thermal profile as experimental samples

- Data Analysis: Plot average Ct values against the logarithm of the initial template concentration

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate efficiency using the slope of the standard curve: Efficiency (%) = (10-1/slope - 1) × 100 [17]

Validation Criteria:

- Efficiency Range: 90-110% considered acceptable [17]

- Linearity: Correlation coefficient (R²) ≥ 0.985 [18]

- Slope: -3.1 to -3.6 representing 90-110% efficiency

Protocol 2: Preparation of Plasmid DNA Standards for Absolute Quantification

Principle: Generate quantifiable standards with identical sequence composition to the target oncogene to ensure equivalent amplification efficiency [4].

Procedure:

- Vector Preparation: Clone the target oncogene amplicon into a standard cloning vector containing an RNA polymerase promoter (T7, SP6, or T3)

- Linearization: Linearize the plasmid upstream or downstream of the target sequence to mimic amplification efficiency of genomic DNA or cDNA

- Quantification: Measure DNA concentration by spectrophotometry (A260)

- Copy Number Calculation: Calculate molecular copies using the formula: (X g/μl DNA / [plasmid length in bp × 660]) × 6.022 × 1023 = Y molecules/μl [4]

- Dilution Series: Prepare 5-10 serial dilutions covering the expected target concentration range in experimental samples

- Aliquoting and Storage: Divide diluted standards into small single-use aliquots and store at -80°C to prevent degradation

Critical Considerations:

- Verify insert identity by sequencing

- Ensure spectrophotometric measurements are not inflated by RNA or chemical contaminants

- Use low-binding tubes and tips during dilution to minimize sample loss

Research Reagent Solutions for Absolute Quantification

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cloning Vector with Promoter | Standard production | Enables in vitro transcription for RNA standards; provides primer binding sites identical to target [4] |

| RNA Polymerase (T7, SP6, T3) | In vitro transcription | Generates RNA standards for gene expression analysis; accounts for reverse transcription efficiency [4] |

| RNase-free DNase | DNA removal | Eliminates template DNA contamination from in vitro transcribed RNA standards [4] |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Fluorescent detection | Binds double-stranded DNA during amplification; requires optimization of primer concentrations [7] |

| TaqMan Hydrolysis Probes | Target-specific detection | Provides enhanced specificity through hybridization; suitable for multiplex reactions [7] |

| Low-Binding Plasticware | Sample handling | Minimizes nucleic acid loss during serial dilution preparation; critical for accurate quantification [3] |

Workflow Visualization

Absolute Quantification Workflow

Addressing variability in amplification efficiency and standard preparation represents a foundational requirement for reliable absolute quantification of oncogene expression by qPCR. The integration of robust efficiency determination methods, particularly the standard curve approach as the current gold standard, with meticulous standard preparation protocols provides a framework for enhancing data quality and experimental reproducibility. The implementation of sigmoidal analysis approaches, such as LRE analysis, offers promising alternatives to traditional exponential models by accounting for the dynamic nature of amplification efficiency throughout the reaction profile. For oncogene research applications, where quantitative accuracy directly impacts biological interpretation and potential clinical applications, rigorous attention to these fundamental methodological elements remains essential for generating scientifically valid and translationally relevant data.

Implementing Absolute Quantification: From Standard Curves to Digital PCR

Absolute quantification by quantitative PCR (qPCR) is a powerful method that determines the exact copy number of a specific nucleic acid sequence in a sample, providing crucial data for oncogene expression studies in cancer research and drug development. This approach relies on constructing a standard curve using samples of known concentration, against which unknown samples are quantified [3] [4]. Unlike relative quantification, which expresses gene expression as a fold-change relative to a reference sample, absolute quantification provides concrete copy numbers, enabling direct comparison of results across different experiments and laboratories [3]. This is particularly valuable in preclinical drug efficacy testing, where precise measurement of oncogene expression changes in response to therapeutic compounds is essential [19].

The reliability of absolute quantification hinges entirely on the accuracy and integrity of the standards used. Two of the most common standards are plasmid DNA and in vitro transcribed RNA, each with distinct advantages and appropriate applications [4]. When properly designed and validated, standard curves enable researchers to quantify gene expression with high sensitivity over a wide dynamic range, as demonstrated in drug discovery assays against Leishmania tropica, where standard curves showed linearity over a 9-log concentration range [19]. This technical note details best practices for preparing and using these standards to generate publication-quality data in oncogene expression studies.

Principles of Standard Curve Design

The fundamental principle underlying the standard curve method is the relationship between the quantification cycle (Cq) value and the initial template concentration in the qPCR reaction [3]. During amplification, the point at which the fluorescence signal crosses a predetermined threshold (Cq) is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the initial template concentration. A series of standard dilutions with known concentrations is amplified alongside experimental samples, generating a standard curve from which the concentration of unknowns can be extrapolated [4].

Critical parameters for a reliable standard curve include:

- Linear Dynamic Range: The standard curve should cover the entire expected concentration range of the target in experimental samples [4].

- Amplification Efficiency: Ideally between 90-110%, indicating that the template doubles with each amplification cycle [20] [5].

- Coefficient of Determination (R²): Should be ≥0.985, demonstrating a strong linear relationship between Cq and log concentration [19].

For optimal results, standard curves should consist of at least five data points spanning several orders of magnitude (typically 5- to 10-fold dilutions) to establish a robust linear relationship [21]. Each standard dilution should be run in multiple replicates to account for technical variability, with a minimum of three replicates recommended for reliable quantification [22].

Table 1: Optimal Parameters for Standard Curve Performance

| Parameter | Optimal Value | Acceptable Range | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification Efficiency | 100% | 90-110% | E = 10^(-1/slope) |

| Slope | -3.32 | -3.1 to -3.6 | Linear regression of standard curve |

| R² Value | 1.000 | ≥0.985 | Linear regression of standard curve |

| Dynamic Range | >6 logs | Minimum 5 logs | Concentration range of standards |

| Number of Data Points | 5-7 | Minimum 5 | Serial dilutions of standard |

Plasmid DNA Standards

Preparation of Plasmid DNA Standards

Plasmid DNA is a widely used standard for absolute quantification due to its stability, ease of production, and ability to be accurately quantified [4]. The preparation process begins with cloning the target sequence, including the amplicon and flanking regions, into an appropriate vector. For optimal accuracy, the insert should be generated by RT-PCR from total RNA or mRNA, or by PCR from cDNA, ensuring it includes at least 20 bp upstream and downstream of the primer binding sites used in the qPCR assay [4].

A critical step in preparation is the linearization of plasmid DNA. Supercoiled plasmid conformation can exhibit different amplification efficiency compared to genomic DNA or cDNA, potentially leading to quantification inaccuracies [20] [4]. Linearization with restriction enzymes upstream or downstream of the target sequence produces a template that more closely mimics natural DNA substrates and provides more consistent amplification [4]. After linearization, plasmid concentration should be determined by spectrophotometry at A260, ensuring the A260/A280 ratio is between 1.8-2.0, indicating pure nucleic acid preparation free from protein or RNA contamination [20].

Copy Number Calculation and Dilution Scheme

The copy number of plasmid DNA standards is calculated from the spectrophotometric concentration measurement using the formula:

Copy number/μL = (X g/μL DNA / [plasmid length in bp × 660]) × 6.022 × 10^23 [4]

Where X g/μL is the mass concentration determined by spectrophotometry, plasmid length is in base pairs, 660 Da is the average molecular weight of one base pair, and 6.022 × 10^23 is Avogadro's number. This calculation is essential for converting mass-based concentration measurements to copy numbers relevant for molecular quantification [4].

Serial dilutions should be prepared over a range covering the expected target concentrations in experimental samples, typically spanning 5-6 orders of magnitude [21]. To minimize pipetting error in large dilution series, prepare an initial high-concentration stock and perform sequential dilutions rather than diluting from the original stock each time. Dilution stability must be considered, with aliquots stored at -80°C and subjected to a single freeze-thaw cycle to prevent degradation [3].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Plasmid DNA Standards

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor amplification efficiency | Supercoiled plasmid conformation | Linearize plasmid before use |

| Inconsistent standard curve | Residual RNA contamination | Treat with RNase during purification |

| 10-fold discrepancy in copy number | Using plasmid size instead of amplicon size in calculation | Use amplicon length for copy number calculation [20] |

| High variability between replicates | Plasmid carryover contamination | Use dedicated areas for pre- and post-PCR work |

| Non-linear standard curve | Primer-dimer formation | Redesign primers or add dissociation curve step |

In Vitro Transcribed RNA Standards

Preparation of RNA Standards

In vitro transcribed RNA standards are essential for absolute quantification of gene expression when measuring RNA targets, as they account for the efficiency of the reverse transcription step [4]. To create these standards, the target sequence is first cloned into a vector containing a bacteriophage RNA polymerase promoter (T7, SP6, or T3). The orientation of the insert must be verified to ensure that in vitro transcription produces the sense transcript [4].

Following in vitro transcription, complete removal of template DNA is critical, as residual plasmid DNA will lead to overestimation of RNA concentration and serve as an efficient template in subsequent PCR reactions, skewing quantification results [4]. Treatment with RNase-free DNase is essential, followed by purification of the transcript. RNA integrity should be confirmed by gel or capillary electrophoresis, showing a single discrete band without degradation products or aberrant transcripts [4].

Quantification and Stability of RNA Standards

The concentration of purified RNA is determined by spectrophotometry, and the copy number is calculated using a modified formula that accounts for the different molecular weight of RNA:

Copy number/μL = (X g/μL RNA / [transcript length in nucleotides × 340]) × 6.022 × 10^23 [4]

Here, 340 Da represents the average molecular weight of one ribonucleotide, and transcript length is in nucleotides. RNA standards are particularly labile compared to DNA, requiring careful handling to prevent degradation. Diluted standards should be divided into small single-use aliquots and stored at -80°C to preserve integrity [3]. The inclusion of RNase inhibitors in dilution buffers may enhance stability, though this should be validated to ensure it doesn't interfere with subsequent reverse transcription or PCR reactions.

Alternative Standard Templates

gBlocks Gene Fragments as Standards

Double-stranded gBlocks Gene Fragments offer a versatile alternative to traditional plasmid standards, particularly when rapid standard development or multiplex quantification is required [21]. These synthetic DNA fragments, up to 3000 bp in length, can be designed to incorporate multiple control amplicon sequences into a single construct, enabling quantification of several targets from the same standard [21].

Key advantages of gBlocks Gene Fragments include:

- Design Flexibility: Sequences can be customized with necessary overlaps or restriction sites for downstream applications [21].

- Multi-Target Standards: Multiple control sequences can be combined on a single fragment, reducing pipetting steps and experimental variability in multiplex experiments [21].

- Rapid Production: Compared to cloning, gBlocks fragments can be produced quickly, facilitating assay optimization [21].

- Contamination Control: Artificial sequences distinguishable from wild-type sequences can be designed, enabling detection of contamination through melt curve analysis [21].

When designing gBlocks with multiple targets, sequences should be separated by several intervening T bases, but not more than 9, as this may interfere with manufacturing [21].

PCR Products and Genomic DNA as Standards

Purified PCR products can serve as practical alternatives to plasmid standards, particularly when rapid standard preparation is prioritized [4]. The PCR product should include the target amplicon plus at least 20 bp of flanking sequence on either side to ensure native amplification efficiency [4]. While quicker to produce than cloned standards, PCR products may contain unidentified sequence errors that could affect amplification efficiency and quantification accuracy [21].

Genomic DNA is appropriate as a standard only when the target is present as a single-copy gene per haploid genome and amplification of pseudogenes or related sequences can be excluded [4]. For example, in mouse models, 1 µg of genomic DNA corresponds to approximately 3.4 × 10^5 copies of a single-copy gene, based on the known genome size of Mus musculus (2.7 × 10^9 bp) [4].

Experimental Protocol: Absolute Quantification of Oncogene Expression

Standard Curve Setup and Validation

This protocol outlines the steps for implementing plasmid DNA and RNA standards for absolute quantification of oncogene expression in drug efficacy studies, adapting approaches validated in anti-parasitic drug discovery [19].

Materials Required:

- Linearized plasmid DNA or in vitro transcribed RNA standard

- RNase-free water for dilutions

- qPCR master mix with appropriate chemistry (SYBR Green or probe-based)

- Primers validated for efficiency and specificity

- Nuclease-free low-binding tubes and pipette tips

Procedure:

- Prepare Stock Solution: Resuspend standard in appropriate buffer and quantify by spectrophotometry. Verify purity (A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0).

- Calculate Copy Number: Use the appropriate formula for DNA or RNA standards as described in sections 3.2 and 4.2.

- Serial Dilutions: Prepare a 10-fold serial dilution series covering at least 5 orders of magnitude, with concentrations spanning the expected range in experimental samples.

- qPCR Setup: Aliquot appropriate volume of each standard dilution into qPCR plates, with a minimum of three replicates per dilution.

- Amplification: Run qPCR with optimized cycling conditions including a dissociation curve step for SYBR Green assays.

- Standard Curve Analysis: Plot Cq values against log copy number to generate standard curve. Validate using parameters in Table 1.

Data Analysis and Quality Control

For absolute quantification, the standard curve is used to determine the copy number of unknown samples by interpolating their Cq values against the curve [4]. Several quality control measures must be implemented:

- Efficiency Validation: Amplification efficiency should be calculated from the slope of the standard curve (Efficiency = 10^(-1/slope)) and fall within 90-110% [5].

- Negative Controls: Include no-template controls to detect contamination and no-reverse-transcriptase controls for RNA quantification to assess genomic DNA contamination [20].

- Melt Curve Analysis: For SYBR Green assays, perform dissociation curve analysis to verify amplification of a single specific product and absence of primer-dimers [20].

When quantifying oncogene expression in response to drug treatments, include appropriate controls such as untreated cells and calibrator samples to enable both absolute and relative comparison of expression levels [19].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Absolute Quantification

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Templates | gBlocks Gene Fragments, Plasmid Vectors | Provide known copy number references for standard curve generation [21] [4] |

| Polymerase Systems | Hot Start Taq Polymerase, One-Step RT-qPCR Kits | Enzymatic amplification of target sequences with minimal background |

| Detection Chemistries | SYBR Green, TaqMan Probes | Fluorescent detection of amplified DNA in real-time |

| Nucleic Acid Purification Kits | Plasmid Prep Kits, RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality nucleic acids for standard preparation |

| Quality Control Tools | DNase I (RNase-free), RNase Inhibitors | Maintain integrity of standards and prevent degradation |

Application in Oncogene Expression Studies

In oncogene expression research within drug development, absolute quantification provides critical data on transcript copy number changes in response to therapeutic compounds [19]. The standard curve method enables precise measurement of even small expression differences, which is particularly valuable when assessing drug efficacy against low-abundance targets [22]. The high sensitivity of properly validated standard curves allows detection of expression changes earlier in treatment, accelerating preclinical decision-making.

The selection of appropriate standards depends on the specific application: plasmid DNA standards are suitable for DNA targets or when reverse transcription efficiency is accounted for separately, while RNA standards are essential when quantifying RNA expression levels and incorporating reverse transcription efficiency into the quantification [4]. For multiplex studies assessing multiple oncogenes or resistance markers, gBlocks Gene Fragments incorporating multiple target sequences provide consistent quantification while reducing experimental variability [21].

Regardless of the standard chosen, rigorous validation following the best practices outlined in this document ensures generation of reproducible, publication-quality data that meets the stringent requirements of drug development pipelines and regulatory submissions.

The imperative for precise, comparable gene expression data in oncology research is paramount, particularly in the development of prognostic and predictive models for cancer patients. Traditional relative quantification by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR), which relies on separate standards for marker and reference genes, introduces variability that compromises data integrity and cross-study comparability. This Application Note details the methodology and advantages of the Single Standard for Marker and Reference genes (SSMR) approach, an absolute quantification system designed to overcome these critical limitations. Framed within the context of absolute quantification of oncogene expression, we provide a detailed protocol for implementing SSMR-based qRT-PCR, present quantitative data demonstrating its superior comparability, and equip researchers with the necessary tools to enhance the rigor of their gene expression analyses.

In the shift towards personalized cancer medicine, molecular variables such as gene expression levels are increasingly used alongside clinical variables to model prognosis and explain variations in survival and therapeutic response [23]. While genome-wide studies identify candidate genes, their validation and inclusion in robust prognostic models often employ qRT-PCR due to its sensitivity and quantitative nature [23].

A pivotal challenge in qRT-PCR analysis is data normalization to account for variations in sample input. Traditional relative quantification methods use a reference gene (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH) for normalization, with the expression of both the marker gene and the reference gene quantified using separate, independent standard curves [23] [2]. This approach is fundamentally flawed because it relies on the assumption that the molar concentrations of the two external standards are accurately known and equal. Any inequality, as pointed out in foundational SSMR research, directly translates into incomparable gene expression data, akin to "taking a half-foot ruler as one foot to measure the same person’s height" [23]. This lack of comparability is a significant barrier to establishing prognostic models, a process that often requires combining independent datasets to achieve statistically meaningful sample sizes [23].

The SSMR approach addresses this by enabling absolute quantification through a multigene DNA standard containing the amplicon sequences for both the marker and reference genes ligated together in a single fragment at a one-to-one ratio [23]. This ensures that any variation in the quantity of the standard or the sample affects both genes equally, thereby eliminating a major source of bias and ensuring that normalized gene expression data are directly comparable across different experiments and laboratories.

Theoretical Foundation and Advantages of the SSMR Approach

Pitfalls of Relative Quantification and Conventional Normalization

Traditional relative quantification is susceptible to several sources of error that can distort biological conclusions:

- Inequality of Standards: The core issue is the use of two distinct physical standards for quantification. Any inaccuracy in the quantification or dilution of either standard introduces a systematic error into the final normalized expression value [23].

- Instability of Reference Genes: The expression of commonly used reference genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH, various ribosomal proteins) can be highly variable under different experimental conditions, such as pharmacological inhibition of key cellular pathways. For instance, the expression of ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, and RPL13A undergoes dramatic changes in cancer cells treated with dual mTOR inhibitors, rendering them "categorically inappropriate" for normalization [12]. Similar instability has been observed for reference miRNAs like SNORD48 and U6 in endometrial cancer studies [24].

- Assumption of 100% PCR Efficiency: Early relative quantification models assumed perfect PCR efficiency, which is often not the case in practice. While efficiency-adjusted models (e.g., Pfaffl method) exist, they still rely on the integrity of separate standard curves [25].

The SSMR Solution: Conceptual Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual difference between the traditional relative quantification method and the SSMR approach, highlighting how SSMR ensures a fixed 1:1 ratio for quantification.

The SSMR method provides two key mechanistic advantages:

- Elimination of Standard-Derived Error: By using a single standard, the quantitative relationship between the marker and reference gene is fixed and known, removing the variability introduced by preparing and quantifying two independent standards [23].

- Independence from Sample and Standard Variation: SSMR-based quantification produces normalized gene expression data that are independent of variations in both the concentration of the cDNA sample and the absolute quantity of the standard used to generate the standard curve. The relative expression ratio remains constant even if the nominal concentration of the standard is miscalculated [23].

Detailed SSMR Protocol for Absolute Quantification of Oncogenes

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials required for implementing the SSMR protocol.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for SSMR-based qRT-PCR

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Comment |

|---|---|---|

| SSMR DNA Standard | Multigene DNA fragment for absolute quantification. | Clone PCR amplicons of target oncogenes (e.g., PAX6, PTEN) and reference genes (e.g., ACTB, RPS9) into a single plasmid. Amplify, purify, and quantify accurately [23]. |

| Primer Design Software | To ensure specific amplification. | Use software (e.g., PrimerDesigner) to design primers that avoid genomic DNA amplification and processing pseudogenes [23]. |

| qPCR Instrument | Real-time fluorescence detection. | Platforms such as Roche LightCycler or Applied Biosystems StepOne are suitable [23]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescent dye. | FAST-START DNA Master SYBR Green I mix or equivalent TaqMan master mixes [23] [26]. |

| Template cDNA | Reverse-transcribed RNA from tumor samples. | Synthesize from high-quality, DNase I-treated total RNA. Use consistent reverse transcription protocols across samples [23]. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Workflow

The complete experimental procedure, from standard preparation to data analysis, is outlined below.

Step 1: SSMR Construct Generation

- Procedure: Select target oncogenes (e.g., VEGFA, EGFR, MMP2) and a validated reference gene (see Section 3.3). Generate PCR amplicons for each gene and ligate them sequentially into a single plasmid vector using standard molecular cloning techniques. The final construct should contain all amplicon sequences in a contiguous fragment.

- Critical Note: The accuracy of the entire assay depends on the precise quantification of this SSMR standard. Use high-precision methods like spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) or fluorometry (Qubit) to determine DNA concentration and calculate molar concentration based on the molecular weight of the construct [23].

Step 2: Primer Design and Validation

- Procedure: Design primers with software to produce amplicons 75-200 bp in length. Crucially, design primers to span exon-exon junctions where possible to prevent amplification of genomic DNA. Validate primer specificity by analyzing melt curves for a single peak and ensure PCR efficiency is between 90% and 110% (slope of -3.6 to -3.1) using a dilution series of the SSMR standard [23] [26].

Step 3: SSMR Standard Dilution

- Procedure: Serially dilute the SSMR stock in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) or a similar low-buffer solution to create a standard curve. A typical 6-point curve from 1x10^6 to 1x10^1 molecules per 4 μL is recommended. Prepare fresh dilutions for each run or aliquot and store at -20°C to avoid freeze-thaw cycles.

Step 4: qPCR Plate Setup

- Reaction Mix (Example for 10 μL):

- 4 μL SSMR standard, cDNA sample, or Nuclease-Free Water (for NTC)

- 1 μL 10X Primer-MgCl2 mix (final: 0.5 μM primers, 2.5-4 mM MgCl2)

- 1 μL FAST-START DNA Master SYBR Green I mix (2X)

- 4 μL Nuclease-Free Water

- Plate Layout: Include the SSMR standard curve in duplicate on every plate. Run all cDNA samples in at least duplicate. Include NTCs for each primer set to check for primer-dimer or contamination [23] [26].

Step 5: qPCR Run

- Cycling Conditions (SYBR Green I, Roche LightCycler):

- Enzyme Activation: 95°C for 10 min

- Amplification (40 cycles): 95°C for 15 sec (denaturation), 60°C for 30-60 sec (annealing/extension with fluorescence acquisition)

- Melt Curve Analysis: 65°C to 95°C with continuous fluorescence acquisition.

Step 6: Data Analysis

- The qPCR software generates a standard curve for each gene by plotting the Cq value against the logarithm of the known starting quantity.

- The absolute copy number for both the marker gene and the reference gene in each cDNA sample is calculated directly from their respective Cq values using the formula:

Quantity (copies) = 10^( (Cq value - Y-intercept) / Slope )[26]. - The final, normalized oncogene expression value is expressed as the ratio of the absolute copy number of the oncogene to the absolute copy number of the reference gene.

Selection and Validation of Reference Genes

The SSMR method, while correcting for standard-related errors, does not negate the need for a stably expressed reference gene. The choice of reference gene is critical and must be empirically validated for your specific cancer model and experimental conditions.

- Commonly Unstable Genes: Genes like ACTB (cytoskeleton) and RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A (ribosomal proteins) have been shown to be unstable in dormant cancer cells induced by mTOR inhibition [12].

- Candidate Genes: Potential stable genes for cancer studies include B2M, YWHAZ, TUBA1A, GAPDH, TBP, and CYC1, but their stability is context-dependent [12].

- Validation: Use algorithms such as geNorm, NormFinder, or BestKeeper to evaluate the expression stability of multiple candidate reference genes across all experimental conditions before selecting the most stable one for your SSMR construct [2].

Experimental Validation and Data Comparison

Quantitative Demonstration of SSMR Robustness

To demonstrate the robustness of the SSMR approach, a foundational study quantified gene expression under two different conditions: using a truthfully diluted SSMR standard and a "falsely" diluted SSMR standard (with half the denoted quantity). The results, summarized below, validate the method's independence from standard concentration errors.

Table 2: SSMR Robustness Against Standard Variation [23]

| Gene Target | SSMR Standard Condition | Calculated Gene Expression in cDNA Sample | Observed Fold-Change | Expected Fold-Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAX6 | Truthful (T) Dilution | Value = X | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| False (F) Dilution (½ Quantity) | Value = 2X | |||

| RPS9 | Truthful (T) Dilution | Value = Y | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| False (F) Dilution (½ Quantity) | Value = 2Y | |||

| PAX6/RPS9 Ratio | Truthful (T) Dilution | X / Y | 1.0 (Equivalent) | 1.0 (Equivalent) |

| False (F) Dilution (½ Quantity) | 2X / 2Y |

As illustrated, while the absolute expression values for individual genes doubled with the erroneous standard, the normalized ratio (PAX6/RPS9) remained identical. This confirms that the final, biologically relevant result is independent of inaccuracies in the absolute quantification of the standard itself [23].

Cross-Study Comparability in Glioma Research

The critical advantage of the SSMR approach was demonstrated in a study analyzing glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) samples processed in two different laboratories (Lab I and Lab II). Gene expression data were generated using both traditional relative quantification and the SSMR-based absolute quantification. The comparability of the normalized data (log10 ratios) between the two labs was evaluated using statistical equivalence testing (TOST procedure).

Table 3: Comparability of GBM Gene Expression Data Between Two Labs [23]

| Gene Target | Quantification Method | Statistical Equivalence Between Labs? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncogene A | Relative qRT-PCR | No | Incomparable results due to inequality in molar concentration of two separate standards. |

| Oncogene B | Relative qRT-PCR | No | Incomparable results due to inequality in molar concentration of two separate standards. |

| Oncogene C | SSMR-based qRT-PCR | Yes | Approximate comparability achieved. Normalized data is independent of variations in sample and standard quantity. |

The study concluded that while relative quantification failed to produce comparable data, the SSMR-based system ensured the comparability of gene expression data, which is essential for combining independent datasets to build powerful prognostic models with large sample sizes [23].

The SSMR approach represents a significant methodological advancement for the absolute quantification of gene expression in oncology research. By replacing the multiple, independent standards of relative quantification with a single, unified standard, it eliminates a fundamental source of technical variability. This protocol provides researchers with a detailed roadmap to implement this robust method, thereby enhancing the integrity, reliability, and cross-study comparability of their qPCR data. The adoption of SSMR is particularly crucial for the rigorous validation of oncogene expression and the development of robust, clinically relevant prognostic and predictive models in cancer.

The precise measurement of oncogene expression levels is a cornerstone of modern cancer research and therapeutic development. For years, quantitative PCR (qPCR) has been the established method for nucleic acid quantification, providing both relative and absolute quantification approaches. Relative quantification determines the ratio between the amount of target gene and a reference gene, typically a stably expressed endogenous control present in all samples [4]. This method is invaluable for comparing gene expression across different tissues or experimental conditions, such as stimulated versus unstimulated cells. In contrast, absolute quantification measures the exact amount of a target nucleic acid sequence, expressed as copy number or concentration, rather than a ratio [4]. This approach relies on external standards of known concentration to generate a standard curve, against which unknown samples are compared.

While qPCR has proven immensely valuable, absolute quantification using this method presents significant challenges for oncogene research. The requirement for precisely calibrated standard curves introduces variability, and quantification accuracy is highly dependent on logarithmic amplification efficiency during each PCR cycle [27] [28]. When amplification is inhibited by sample impurities or when primer/probe binding is suboptimal due to sequence mismatches, quantification can be significantly underestimated [27]. These limitations become particularly problematic when measuring low-abundance oncogene transcripts or rare mutations, where the highest level of precision is required.

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents a transformative approach that addresses these fundamental limitations. By partitioning a sample into thousands of individual reactions, dPCR enables absolute quantification without standard curves, offering superior precision and sensitivity for critical applications in cancer research and molecular diagnostics [27] [28]. This application note explores the technical foundations, performance advantages, and practical implementation of dPCR for absolute quantification of oncogene expression, providing researchers with comprehensive protocols and analytical frameworks to enhance their quantitative gene expression studies.

Fundamental Principles of Digital PCR

Core Technological Framework

Digital PCR operates on a fundamentally different principle than qPCR. Rather than monitoring amplification in real-time through a bulk reaction, dPCR partitions the PCR mixture into thousands to millions of individual reactions [27]. Through this partitioning, the template molecules are randomly distributed across the reactions such that each partition contains zero, one, or a few target molecules. Following end-point PCR amplification, each partition is analyzed for fluorescence [27]. Partitions containing the target sequence (positive) fluoresce, while those without it (negative) do not. The ratio of positive to negative partitions enables absolute quantification of the target molecules in the original sample through Poisson statistics [27].

This partitioning-based approach provides dPCR with several inherent advantages. First, by eliminating the need for standard curves, dPCR removes a major source of inter-laboratory variability and eliminates the requirement for well-characterized reference materials [27]. Second, because quantification is based on endpoint detection rather than amplification efficiency during the exponential phase, dPCR is less affected by PCR inhibitors that may be present in clinical samples [27] [29]. Third, the partitioning effect enhances the detection of rare mutations by effectively enriching low-abundance targets within individual partitions [29].

Practical Workflow Implementation

The typical dPCR workflow involves several key steps that distinguish it from conventional qPCR. First, nucleic acids are extracted from patient samples using standard methods. The sample is then prepared in a master mix containing primers, probes, and PCR reagents, similar to qPCR preparations. This mixture is partitioned into thousands of individual reactions using microfluidic technology—either through water-in-oil droplet systems (ddPCR) or nanoplate-based systems (ndPCR) [27] [30]. The partitioned samples undergo conventional PCR amplification to endpoint. Following amplification, each partition is analyzed for fluorescence using specialized readers that detect positive versus negative reactions [27]. Finally, the results are analyzed using Poisson statistics to determine the absolute copy number of the target sequence in the original sample [27].