A Modern Virtual Screening Workflow for Oncology Drug Discovery: From AI-Acceleration to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the contemporary virtual screening (VS) workflow tailored for identifying novel oncology drug candidates.

A Modern Virtual Screening Workflow for Oncology Drug Discovery: From AI-Acceleration to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the contemporary virtual screening (VS) workflow tailored for identifying novel oncology drug candidates. It covers the foundational principles of VS, including target selection and library preparation, and delves into advanced methodological applications such as structure- and ligand-based screening, AI-accelerated platforms, and drug repurposing. The content addresses key challenges in scoring function accuracy, data management, and model interpretability, offering strategies for optimization. Furthermore, it details rigorous validation protocols involving molecular dynamics, experimental assays, and the emerging role of digital twins. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices and future directions to enhance the efficiency and success rate of oncological drug discovery.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Concepts and Target Identification in Oncology

Virtual screening (VS) represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, employing computer-based methods to rapidly evaluate large chemical libraries and identify compounds most likely to bind to a therapeutic target. In oncology, where traditional drug development faces challenges of high costs, lengthy timelines, and frequent failure rates, virtual screening provides a powerful strategy to accelerate the identification of novel anticancer agents. By leveraging computational power to prioritize candidates for experimental testing, researchers can significantly reduce the number of compounds requiring costly and time-consuming laboratory validation, streamlining the early drug discovery pipeline [1] [2].

The relevance of virtual screening in oncology continues to grow with advances in computational power, algorithmic sophistication, and the availability of high-resolution structural data for cancer-relevant targets. This approach is particularly valuable for targeting difficult-to-drug oncoproteins, understanding polypharmacology in cancer pathways, and repurposing existing drugs for new oncological indications—a strategy that can dramatically shorten development timelines by leveraging existing safety and pharmacokinetic data [1].

Key Principles of Virtual Screening

Virtual screening methodologies generally fall into two main categories: ligand-based and structure-based approaches, which can be used independently or in an integrated fashion.

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening relies on known active compounds (ligands) to identify new candidates with similar structural or physicochemical properties. This approach utilizes techniques such as:

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling

- Pharmacophore modeling (identification of spatial arrangements of chemical features essential for biological activity)

- Molecular similarity searching and machine learning models trained on known active/inactive compounds [3] [4]

Structure-Based Virtual Screening utilizes the three-dimensional structure of the target protein to identify potential binders. Key methods include:

- Molecular docking to predict how small molecules bind to the target's active site

- Scoring functions to rank compounds based on predicted binding affinity

- Molecular dynamics simulations to assess binding stability and interaction dynamics [1] [5]

Table 1: Comparison of Virtual Screening Approaches

| Screening Type | Required Data | Key Methods | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Based | Known active compounds | Pharmacophore modeling, QSAR, similarity search | Effective when target structure unknown; Fast screening of large libraries | Limited to chemical space similar to known actives |

| Structure-Based | 3D protein structure | Molecular docking, scoring functions | Can identify novel scaffolds; Provides structural insights | Dependent on quality of protein structure; Computationally intensive |

| Hybrid Methods | Both protein structures and known actives | Combined workflows, machine learning | Leverages strengths of both approaches; Higher prediction accuracy | Increased complexity in implementation |

Recent advances incorporate artificial intelligence and deep learning to enhance both approaches. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), for instance, can directly learn from molecular structures represented as graphs, capturing complex patterns that relate to biological activity [2]. Methods such as conformal prediction also provide uncertainty quantification, giving researchers confidence measures for virtual screening predictions [3].

Virtual Screening Workflows in Oncology: Case Studies

Drug Repurposing for PAK2 Inhibition in Cancer

A 2025 study demonstrated the power of structure-based virtual screening for drug repurposing in oncology. Researchers screened 3,648 FDA-approved drugs against p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2), a serine/threonine kinase involved in cell motility, survival, and proliferation, making it a promising target for cancer therapy. The workflow included:

- Target Preparation: The 3D structure of PAK2 was retrieved from AlphaFold and optimized via energy minimization.

- Compound Library Preparation: FDA-approved drugs from DrugBank were prepared with appropriate ionization states.

- Molecular Docking: Blind docking was performed using AutoDock Vina with a grid covering the entire PAK2 structure.

- Interaction Analysis: Binding poses were analyzed using PyMOL and LigPlus to identify key interactions.

- Validation: Molecular dynamics simulations of 300 ns assessed binding stability [1].

This approach identified Midostaurin and Bagrosin as top candidates with high predicted binding affinity and specificity for PAK2. Molecular dynamics confirmed stable binding with minimal structural perturbations compared to the known inhibitor IPA-3. The study highlights how virtual screening can rapidly identify repurposing opportunities for oncology targets [1].

Novel Tubulin Inhibitor Discovery

Another 2025 study showcased virtual screening for novel anticancer agent discovery targeting tubulin. Researchers screened 200,340 compounds from the Specs library against taxane and colchicine binding sites:

- Library Preparation: Commercial Specs library compounds were prepared for docking.

- Molecular Docking: Glide software was used to dock compounds against both binding sites.

- Hit Selection: Top 300 structures per site were selected, with 93 candidates advancing after clustering and visual inspection.

- Experimental Validation: Purchased compounds were tested for antiproliferative activity against cancer cell lines [5].

This workflow identified a nicotinic acid derivative (compound 89) as a potent tubulin inhibitor that demonstrated significant antitumor efficacy in vitro and in vivo, including activity in patient-derived organoids. Mechanism studies confirmed it inhibits tubulin polymerization via binding to the colchicine site and modulates PI3K/Akt signaling [5].

Deep Learning-Accelerated Screening for Cancer Targets

A 2024 study introduced VirtuDockDL, a deep learning pipeline that combines ligand- and structure-based screening with graph neural networks (GNNs). The platform demonstrated exceptional performance in benchmarking, achieving 99% accuracy, F1 score of 0.992, and AUC of 0.99 on the HER2 dataset—surpassing both DeepChem (89% accuracy) and AutoDock Vina (82% accuracy). The workflow includes:

- Molecular Representation: SMILES strings are transformed into molecular graphs using RDKit.

- Feature Extraction: The GNN model extracts structural features and combines them with molecular descriptors.

- Activity Prediction: The model predicts biological activity based on learned patterns.

- Virtual Screening: High-scoring compounds are prioritized for docking studies [2].

This approach was successfully applied to identify inhibitors for cancer-related targets including HER2 (breast cancer), demonstrating how AI integration can enhance virtual screening accuracy and efficiency [2].

Experimental Protocols for Virtual Screening in Oncology

Structure-Based Virtual Screening Protocol

Objective: To identify potential inhibitors for an oncology target using molecular docking.

Materials and Software:

- Target protein structure (from PDB, AlphaFold, or homology modeling)

- Compound library (e.g., ZINC, DrugBank, in-house collections)

- Docking software (AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD)

- Visualization tools (PyMOL, Chimera)

- Computing infrastructure (high-performance computing cluster recommended)

Methodology:

Target Preparation

- Obtain 3D structure of target protein

- Remove water molecules and add hydrogen atoms

- Assign partial charges and optimize hydrogen bonding

- Define binding site (known active site or via blind docking)

- For PAK2 screening: Grid box centered at X: -4.62 Å, Y: 1.396 Å, Z: -1.185 Å with dimensions 69×63×73 Å [1]

Ligand Library Preparation

- Obtain structures in appropriate format (SDF, MOL2)

- Generate 3D conformations

- Assign correct ionization states at physiological pH

- Energy minimize structures using molecular mechanics

Molecular Docking

- Run docking simulations with appropriate sampling

- Score compounds using scoring functions

- Cluster results and analyze binding poses

- Select top candidates based on docking scores and interaction patterns

Post-Docking Analysis

- Visualize binding modes of top hits

- Analyze key protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts)

- Filter based on drug-like properties and structural diversity

Validation (Optional but Recommended)

- Molecular dynamics simulations to assess binding stability

- Binding free energy calculations (MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA)

- Experimental validation via biochemical or cell-based assays

AI-Enhanced Virtual Screening Protocol

Objective: To leverage deep learning for accelerated virtual screening of large compound libraries.

Materials and Software:

- Curated dataset of active/inactive compounds for target of interest

- Deep learning framework (PyTorch, TensorFlow)

- RDKit for cheminformatics

- PyTorch Geometric for graph neural networks

- VirtuDockDL or similar platforms [2]

Methodology:

Data Preparation

- Collect known active and inactive compounds for target

- Standardize structures and remove duplicates

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets

- Generate molecular descriptors and fingerprints

Model Training

- Represent molecules as graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges)

- Implement Graph Neural Network architecture:

- Graph convolution layers for feature extraction

- Batch normalization for training stability

- Residual connections to prevent vanishing gradients

- Dropout for regularization

- Train model to predict activity based on structural features

Virtual Screening

- Apply trained model to screen large compound libraries

- Generate activity scores for each compound

- Select top-ranking compounds for further analysis

Integration with Structure-Based Methods

- Subject AI-prioritized compounds to molecular docking

- Analyze binding poses and interactions

- Select final candidates for experimental testing

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Virtual Screening in Oncology

| Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | FDA-approved drugs, SPECS library, ZINC database, DrugBank | Source of small molecules for screening | Screening of 3,648 FDA-approved drugs [1]; SPECS library (200,340 compounds) [5] |

| Target Structures | PDB, AlphaFold, ModelArchive | Source of 3D protein structures for structure-based screening | PAK2 structure from AlphaFold (AF-Q13177) [1] |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD | Predict binding poses and affinity | AutoDock Vina for PAK2 screening [1]; Glide for tubulin inhibitor discovery [5] |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Assess binding stability and dynamics | 300 ns MD simulations for PAK2 complexes [1] |

| Cheminformatics | RDKit, OpenBabel, KNIME | Process and analyze chemical structures | RDKit for molecular graph construction [2] |

| AI/ML Platforms | VirtuDockDL, DeepChem, PyTorch Geometric | Implement deep learning for VS | VirtuDockDL with Graph Neural Networks [2] |

| Activity Prediction | SwissTargetPrediction, PASS Online | Predict potential biological activities | SwissTargetPrediction for target identification [4] |

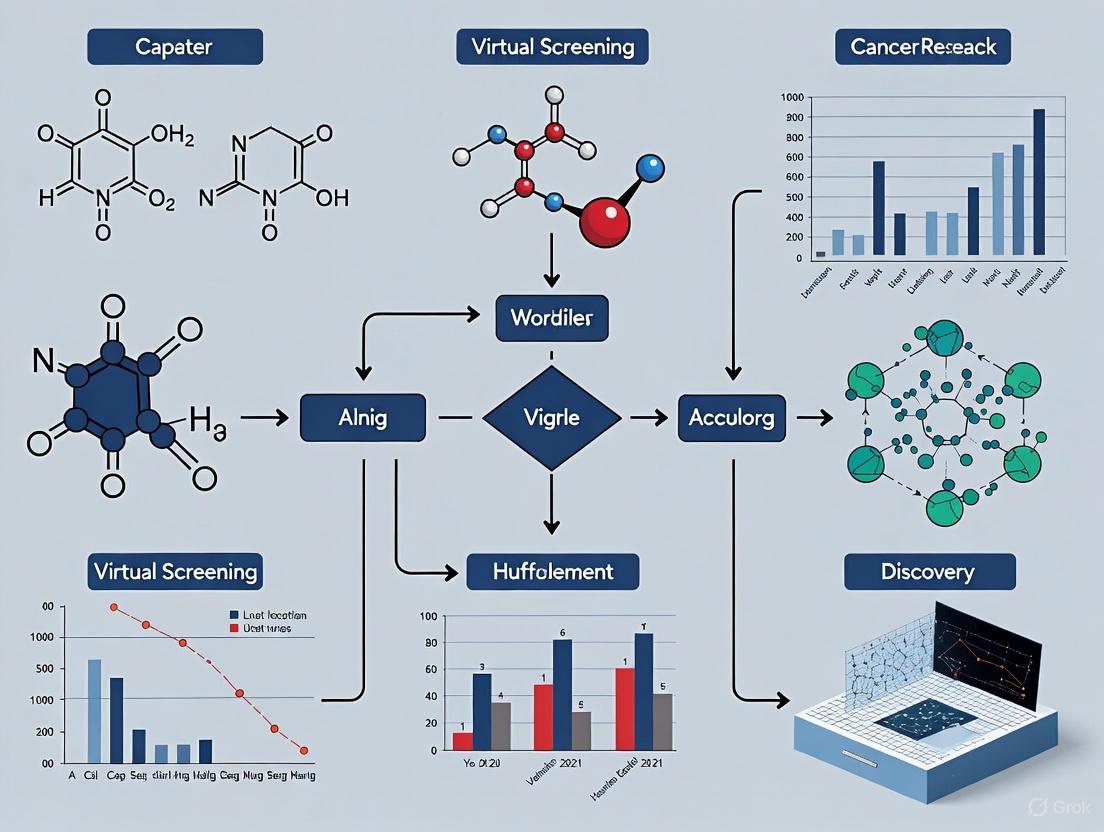

Workflow Visualization

Virtual Screening Workflow Diagram Showing Multiple Computational Approaches

AI-Enhanced Screening Pipeline Using Graph Neural Networks

Relevance and Future Perspectives in Oncology Drug Discovery

Virtual screening has become an indispensable tool in oncology research, directly addressing several key challenges in cancer drug discovery:

Accelerating Targeted Therapy Development The ability to rapidly screen compound libraries against specific cancer targets enables researchers to keep pace with the growing number of oncogenic drivers being identified through genomic studies. For precision oncology, virtual screening facilitates the identification of compounds targeting specific mutations or aberrant pathways in cancer subtypes [6].

Drug Repurposing Opportunities As demonstrated by the PAK2 study, virtual screening can identify new anticancer applications for existing drugs, potentially shortening development timelines by 5-7 years compared to novel drug development [1]. This approach leverages existing safety and pharmacokinetic data, reducing regulatory hurdles.

Addressing Tumor Heterogeneity and Resistance Advanced virtual screening approaches can model complex tumor microenvironment interactions and address mechanisms of drug resistance. Quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) models and virtual patient simulations help account for inter-patient and intra-tumoral heterogeneity, enabling the identification of compounds effective across diverse cancer populations [6].

The future of virtual screening in oncology will likely see increased integration of multi-omics data, AI methods, and digital twin technologies that create virtual representations of individual patients' tumors for personalized therapy optimization. As computational power grows and algorithms become more sophisticated, virtual screening will play an increasingly central role in overcoming the persistent challenges of cancer drug development [6] [2].

The selection and validation of cancer-relevant protein targets represents the foundational step in any successful oncology drug discovery pipeline, particularly within virtual screening workflows for identifying novel therapeutic candidates. This initial phase determines the eventual success or failure of drug development programs, as an improperly chosen target can lead to costly late-stage failures. Proteins such as the serine/threonine kinase PAK2 and the mutant epidermal growth factor receptor EGFR L858R serve as exemplary models for understanding target selection criteria, demonstrating both the challenges and opportunities in contemporary cancer drug discovery. PAK2 has emerged as a significant driver of cancer progression through its involvement in critical processes including angiogenesis, metastasis, cell survival, metabolism, immune response, and drug resistance [7]. In contrast, EGFR L858R represents a clinically validated target with established therapeutic approaches, providing a benchmark for successful target characterization [8] [9].

The complexity of cancer biology demands rigorous methodological approaches for target identification and validation. Currently, no single method proves universally satisfactory for this task, necessitating integrated strategies that combine complementary techniques [10]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for selecting and validating cancer-relevant proteins, with specific protocols for assessing targets like PAK2 and EGFR L858R within virtual screening workflows for oncology drug candidates. By establishing standardized criteria and methodologies, researchers can systematically evaluate potential targets before committing substantial resources to compound screening and optimization phases.

Target Selection Criteria: From Biological Rationale to Druggability Assessment

The selection of viable protein targets for oncology drug discovery requires a multi-factorial assessment that balances biological relevance with practical therapeutic considerations. The following criteria provide a structured framework for evaluating potential targets early in the discovery pipeline.

Established vs. Emerging Cancer Targets: A Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cancer Target Selection Criteria

| Selection Criteria | EGFR L858R (Established Target) | PAK2 (Emerging Target) |

|---|---|---|

| Oncogenic Mechanism | Gain-of-function mutation causing constitutive kinase activation [9] | Overexpression/hyperactivation driving tumor progression [7] |

| Evidence Level | Clinically validated with multiple approved therapies [8] [9] | Preclinical evidence with no clinical inhibitors yet [7] |

| Therapeutic Targeting | FDA-approved TKIs (osimertinib, erlotinib, etc.) [8] | Limited selective inhibitors; research stage [1] |

| Resistance Mechanisms | Well-characterized (T790M, C797S mutations) [9] | Emerging understanding of role in multi-drug resistance [7] |

| Clinical Testing | Standard biomarker testing (NGS) [8] | Not yet clinically validated as biomarker |

| Druggability | High (proven tractable with small molecules) [8] | Moderate (kinase domain targetable) [1] |

Comprehensive Target Selection Criteria

Beyond the comparative analysis of specific targets, a systematic evaluation framework should incorporate the following key criteria:

- Genetic Evidence: Prioritize targets with genomic alterations (mutations, amplifications) in specific cancer types and evidence from loss-of-function studies demonstrating essentiality for cancer cell survival [11].

- Functional Role in Hallmarks of Cancer: Assess involvement in established cancer processes including sustained proliferation, evasion of cell death, activation of invasion and metastasis, and induction of angiogenesis [7] [12].

- Expression Patterns: Evaluate overexpression in tumor versus normal tissues, with correlation to advanced disease stages and poor clinical outcomes [7].

- Druggability Assessment: Determine presence of well-defined binding pockets (e.g., ATP-binding site for kinases) and feasibility of developing small-molecule inhibitors or biologic therapeutics [1].

- Therapeutic Index Potential: Consider differential expression or essentiality between cancer and normal cells, potential compensatory mechanisms, and overall safety profile [7].

Experimental Protocols for Target Validation

Robust target validation requires integrated experimental approaches that collectively build evidence for therapeutic relevance. The following protocols provide methodologies for establishing confidence in selected targets.

Protocol 1: Genetic Validation of Target Essentiality

Objective: To determine whether a candidate protein is essential for cancer cell survival and proliferation using genetic perturbation methods.

Materials:

- Cancer cell lines with target overexpression (e.g., pancreatic, ovarian for PAK2) [7]

- Control cell lines with normal expression levels

- siRNA/shRNA constructs or CRISPR-Cas9 components for gene knockdown/knockout

- Cell viability assays (MTT, CellTiter-Glo)

- Apoptosis detection kits (Annexin V staining)

- Cell cycle analysis reagents (propidium iodide)

Procedure:

- Transfect/transduce candidate cancer cell lines with target-specific siRNA/shRNA or CRISPR-Cas9 constructs.

- Include appropriate negative controls (non-targeting sequences) and positive controls (essential genes).

- Confirm knockdown/knockout efficiency via Western blotting or qRT-PCR at 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Assess functional consequences:

- Measure cell viability at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours using CellTiter-Glo luminescent assay.

- Analyze apoptosis induction via Annexin V/propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry at 48 hours.

- Evaluate cell cycle distribution through propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry.

- For metastatic potential, perform migration/invasion assays (Transwell with Matrigel).

- Validate specificity through rescue experiments with cDNA constructs resistant to silencing.

Interpretation: Significant reduction in viability (>50%), increased apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest indicate target essentiality. Correlation with baseline target expression levels strengthens validation.

Protocol 2: Affinity-Based Target Identification

Objective: To identify direct protein targets of bioactive small molecules using affinity purification methods.

Materials:

- Biotin-tagged small molecule probe (retaining biological activity)

- Streptavidin/avidin-conjugated resins

- Cell lysates from relevant cancer models

- Competitive free compound (untagged)

- Mass spectrometry equipment and analysis software

- Western blotting equipment for validation

Procedure:

- Prepare cell lysates from cancer cell lines or tumor tissues under non-denaturing conditions.

- Incubate lysates with biotin-tagged compound-bound streptavidin resin:

- Experimental condition: lysate + compound-resin

- Competition condition: lysate pre-incubated with excess free compound + compound-resin

- Wash resins extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specific binders.

- Elute bound proteins using Laemmli buffer or excess free compound.

- Analyze eluates by SDS-PAGE and silver staining to visualize specific binding proteins.

- Identify specific binders (present in experimental but reduced in competition condition) by mass spectrometry.

- Validate interactions through Western blotting for candidate proteins.

Interpretation: Proteins specifically competed by free compound represent high-confidence direct targets. Functional relevance should be established through follow-up studies [10].

Protocol 3: Computational Target Identification and Validation

Objective: To identify and validate potential drug targets through proteogenomic analysis and virtual screening.

Materials:

- Public proteogenomic databases (e.g., CPTAC)

- Protein structure databases (AlphaFold, PDB)

- Molecular docking software (AutoDock Vina, GROMACS)

- FDA-approved compound libraries (DrugBank)

Procedure:

- Data Mining: Interrogate proteogenomic databases for targets with:

- Cancer-specific alterations (overexpression, mutations)

- Correlation with poor survival outcomes

- Association with therapeutic resistance

- Structure Preparation: Obtain 3D protein structures from AlphaFold or PDB; perform energy minimization and quality validation (e.g., Ramachandran plots) [1].

- Virtual Screening:

- Prepare library of 3,648 FDA-approved compounds from DrugBank.

- Perform molecular docking with grid covering entire protein structure.

- Select top candidates based on binding affinity and interaction analysis.

- Validation:

- Conduct molecular dynamics simulations (300 ns) to assess complex stability.

- Perform principal component analysis to examine conformational changes.

- Compare with reference inhibitors (e.g., IPA-3 for PAK2) [1].

Interpretation: Compounds with high binding affinity, stable dynamics, and specific interactions represent repurposing candidates for experimental validation.

Signaling Pathway Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathways associated with PAK2, a promising cancer-relevant kinase target, showing its position within cellular signaling networks and potential points for therapeutic intervention.

Research Reagent Solutions for Target Validation Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Target Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Purification | Biotin-streptavidin systems, affinity resins | Immobilize compounds for pull-down assays to identify direct binding proteins [10] |

| Genetic Perturbation | siRNA/shRNA, CRISPR-Cas9 systems | Knockdown/knockout target genes to assess essentiality for cancer cell survival |

| Computational Tools | AutoDock Vina, GROMACS, AlphaFold | Molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and protein structure prediction [1] |

| Proteogenomic Databases | CPTAC, TCGA | Access multi-omics data linking genomic alterations to protein expression [11] |

| Cell-Based Assays | Viability, apoptosis, migration kits | Evaluate functional consequences of target modulation |

| Validated Inhibitors | IPA-3 (PAK2 reference), Osimertinib (EGFR L858R) | Benchmark compounds for experimental controls [1] [9] |

The systematic selection and validation of cancer-relevant proteins represents a critical prerequisite for successful virtual screening campaigns in oncology drug discovery. The integrated approaches outlined in this application note—combining genetic, biochemical, and computational methodologies—provide a robust framework for establishing confidence in targets such as PAK2 and EGFR L858R before committing to resource-intensive screening efforts. As the field advances, emerging technologies including AI-based drug candidate design [13] and expansive proteogenomic datasets [11] promise to further streamline this essential phase of drug discovery. By applying these standardized protocols and criteria, researchers can enhance the efficiency of their virtual screening workflows and increase the probability of identifying viable oncology drug candidates with genuine therapeutic potential.

The efficacy of any virtual screening (VS) campaign for oncology drug candidates is fundamentally dependent on the quality and composition of the initial chemical library. A well-sourced and meticulously curated compound library provides the essential chemical space from which potential hits are identified, serving as the foundation for discovering novel therapeutics or repurposing existing drugs. For oncology-focused research, this necessitates the strategic integration of diverse compound classes, including FDA-approved drugs for repurposing, natural products for their privileged structural diversity, and microbial extracts for novel bioactivity. This application note details standardized protocols for sourcing and curating these critical compound libraries, framed within a robust virtual screening workflow aimed at accelerating oncology drug discovery.

Sourcing Strategic Compound Libraries

The first phase involves the strategic acquisition of compounds from diverse sources to ensure broad coverage of chemical and biological space. The quantitative overview of core library types essential for an oncology VS campaign is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Core Compound Libraries for Oncology Virtual Screening

| Library Type | Exemplary Size | Key Sources & Composition | Primary Application in Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDA-Approved & Drug Repurposing | ~3,400 - 3,648 compounds [14] [15] | Drugs from FDA, EMA, and other major regulators; compounds from pharmacopoeias (USP, JP) [14]. | Rapid identification of new anti-cancer indications for known drugs; excellent starting points due to known safety profiles [16] [15]. |

| Commercial Drug-like/Diversity | >200,000 - 500,000 compounds [16] [17] | Cherry-picked compounds from vendors (e.g., ChemDiv, Maybridge); includes targeted libraries (e.g., kinase-focused, epigenetic) [16] [18]. | De novo discovery of novel oncology hits; targeting specific pathways or protein families. |

| Natural Products & Microbial Extracts | >45,000 extracts; >420 pure natural products [16] [19] | Pure natural products from microbial strains (e.g., actinomycetes); fractionated extracts from global ecological niches [16] [19]. | Discovery of unique scaffolds with novel mechanisms of action; targeting challenging protein-protein interactions. |

Protocol: Library Acquisition and Initial Processing

Materials:

- Commercial Libraries: Sourced from specialized providers (e.g., TargetMol, MedChemExpress, Selleckchem) [18] [14] [19].

- Natural Product Repositories: Academic and institutional collections (e.g., University of Kentucky CTCB, University of Michigan LSI) are valuable sources for unique compounds [16] [19].

- Data Files: For virtual screening, ensure libraries are obtained with associated structural data files (SDF, SMILES) and annotated with known biological activities where available [18] [14].

Procedure:

- Library Selection: Select libraries based on the oncology target and screening strategy. For novel target deorphanization, large diversity libraries (>200,000 compounds) are appropriate [17] [18]. For repurposing, focused FDA-approved libraries (~3,400 compounds) are optimal [15].

- Data Procurement: Download or request the structural data file (SDF) for the entire library. For physical screening, compounds are typically received as 10 mM DMSO solutions in 96- or 384-well plates [14].

- Initial Registration: Register each compound using a database system (e.g., ActivityBase) to auto-generate unique identifiers. This links the compound structure, source, and source sample identifier [20].

- Structural Standardization: Process structural files to standardize chemical representations. This includes:

- Salts Stripping: Remove common counterions to generate the parent neutral structure [20].

- Tautomer Standardization: Generate a canonical tautomeric form for each molecule.

- Stereochemistry: Clearly define stereocenters; register racemic mixtures or enantiomers as separate entities if specified.

Curating Libraries for Virtual Screening

Curating a library ensures its chemical integrity and prepares it for computational interrogation. The workflow for library curation and screening is multi-staged.

Protocol: Computational Curation of a Screening Library

Materials:

- Software: Cheminformatics toolkits (e.g., RDKit, OpenBabel), KNIME, or commercial platforms.

- Hardware: Standard computer workstation; high-performance computing (HPC) cluster for large-library processing.

Procedure:

- Property Filtering: Apply drug-likeness filters to focus on compounds with favorable physicochemical properties.

- Standard filters include molecular weight (MW) ≤ 500, calculated LogP (cLogP) ≤ 5, hydrogen bond donors ≤ 5, and hydrogen bond acceptors ≤ 10 [17].

- These criteria ensure compounds occupy a chemical space more likely to result in successful oral drugs.

- Pan-Assay Interference Compound (PAINS) Removal: Screen the library against a filter of known PAINS substructures to remove compounds with a high probability of nonspecific assay interference, a critical step to reduce false positives.

- Redundancy and Diversity Analysis:

- Remove Tautomers and Duplicates: Ensure each unique chemical structure is represented once.

- Diversity Analysis: Use molecular fingerprints (e.g., MACCS, ECFP4) and clustering algorithms (e.g., k-means) to assess the library's structural diversity. A high-quality library, such as the FDA-Approved & Pharmacopeia Library, can be classified into thousands of distinct categories, indicating broad coverage of chemical space [14].

- Oncology-Focused Annotation (Optional but Recommended):

- Annotate compounds with known or predicted activity against oncology-relevant targets (e.g., kinases, epigenetic regulators, apoptosis proteins) using public databases (e.g., ChEMBL, DrugBank) or predictive models.

- This enables the creation of targeted sub-libraries for specific oncology pathways.

Experimental Protocol: Structure-Based Virtual Screening with an FDA-Approved Library

This protocol details a representative VS campaign for identifying inhibitors of an oncology target, p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2), from an FDA-approved library [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Virtual Screening Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item/Resource | Function/Description | Exemplary Source |

|---|---|---|

| FDA-Approved Drug Library | A curated collection of ~3,648 approved drugs for repurposing screens. | DrugBank [15] |

| Protein Structure | 3D atomic coordinates of the target protein for docking. | AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [15] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Predicts the binding pose and affinity of small molecules to the target. | AutoDock Vina [15] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates the stability and dynamics of the protein-ligand complex over time. | GROMACS [15] |

| Visualization Software | Analyzes and visualizes molecular interactions and docking poses. | PyMOL [15] |

Materials

- Compound Library: A library of 3,648 FDA-approved compounds in SDF format, sourced from DrugBank [15].

- Target Protein Structure: The 3D structure of PAK2 (AlphaFold ID: AF-Q13177), retrieved from the AlphaFold database [15].

- Software:

Procedure

- Data Preparation:

- Protein Preparation: Load the PAK2 structure into AutoDock Tools. Add polar hydrogens, compute Gasteiger charges, and define the torsional degrees of freedom for flexible residues if needed. Energy minimization may be performed to remove steric clashes [15].

- Ligand Preparation: Process the FDA-approved compound library. Convert structures to PDBQT format, setting appropriate torsion trees and charges [15].

- Molecular Docking:

- Grid Box Setup: Define a grid box large enough to encompass the entire protein or a specific binding site of interest. For a blind docking screen of PAK2, a grid with dimensions 69 Å x 63 Å x 73 Å was used [15].

- Docking Execution: Run AutoDock Vina to dock each compound in the library against the prepared PAK2 structure. The output is a ranked list of compounds based on predicted binding affinity (in kcal/mol) [15].

- Post-Docking Analysis:

- Pose Inspection: Visually inspect the top-ranking compounds (e.g., the top 50-100) in PyMOL. Analyze key molecular interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-stacking) with critical residues in the PAK2 active site [15].

- Interaction Analysis: Use LigPlus to generate detailed 2D interaction diagrams for the top candidates [15].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations (For Hit Validation):

- System Setup: Solvate the top protein-ligand complexes (e.g., PAK2-Midostaurin, PAK2-Bagrosin) in a cubic water box. Add ions to neutralize the system's charge [15].

- Production Run: Perform an all-atom MD simulation for a significant duration (e.g., 300 ns) using GROMACS. This assesses the stability of the protein-ligand complex over time [15].

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the simulation trajectories for key parameters, including root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), and the stability of key hydrogen bonds. This step provides critical validation beyond static docking scores [15].

The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow, from library preparation to experimental follow-up.

A meticulously prepared chemical space is the critical first step in a successful virtual screening pipeline for oncology drug discovery. By systematically sourcing and curating compound libraries—from repurposable FDA-approved drugs to structurally unique natural products—researchers can ensure their screening efforts are both efficient and effective. The standardized protocols and illustrative case study provided here offer a roadmap for constructing high-quality, oncology-focused libraries and executing a structure-based virtual screen, ultimately accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic candidates.

In modern oncology drug discovery, virtual screening has emerged as a powerful strategy to efficiently identify promising therapeutic candidates from vast chemical libraries [1]. This computational approach is particularly valuable given the high costs and time-intensive nature of traditional high-throughput screening methods [2]. The core of an effective virtual screening workflow comprises three fundamental computational components: molecular docking, which predicts how small molecules bind to a protein target; scoring functions, which estimate binding affinity; and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which assess the stability of these interactions over time [21] [1] [22]. When properly integrated, these methods form a robust pipeline for prioritizing compounds with the highest potential to become effective oncology therapeutics, ultimately accelerating the drug discovery process for cancers such as liposarcoma and other malignancies [23].

Core Computational Components

Molecular Docking

Molecular docking computationally predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to its target protein. The process involves a search algorithm that explores possible binding poses and a scoring function that ranks these poses based on predicted binding affinity [24]. In structure-based virtual screening, docking serves as the primary workhorse for rapidly evaluating thousands to billions of compounds [24].

Successful docking relies on proper system preparation. Proteins typically require hydrogen atom addition, hydrogen bond optimization, and removal of atomic clashes before docking [25]. Ligands must be prepared with correct bond orders, tautomeric states, and 3-dimensional geometries [25] [22]. The accuracy of docking screens can be significantly improved by using multiple protein structures when available, including holo, apo, and modeled conformations [24].

Table 1: Common Docking Software and Their Applications

| Software Tool | Key Features | Common Applications in Oncology |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [21] [1] | Efficient optimization, multithreading | Drug repurposing screens, β-lactamase inhibitors [21] |

| DOCK3.7 [24] | Physics-based scoring, grid-based | Large-scale library screening, GPCR targets |

| Glide [25] | Hierarchical screening, precise scoring | High-accuracy pose prediction, database enrichment |

| CB-Dock2 [23] | Template-independent and template-based blind docking | Carcinogen-target interaction studies |

Scoring Functions

Scoring functions are mathematical models used to predict the binding affinity between a protein and ligand. They are typically classified into three main categories: force-field-based, empirical, and knowledge-based functions [22]. Recent advances include the development of machine learning-based scoring functions that combine physics-based terms with sophisticated algorithms to improve binding affinity prediction [22].

The performance of scoring functions varies significantly across different target classes, leading to the development of target-specific scoring functions for particular protein families such as proteases and protein-protein interactions [22]. These specialized functions often achieve better affinity prediction than general scoring functions trained across diverse protein families [22].

Key physical interactions considered in modern scoring functions include:

- Van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions [22]

- Solvation effects and lipophilic interactions [22]

- Hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions [26]

- Ligand torsional entropy contribution to binding [22]

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Scoring Functions on DUD-E Datasets

| Scoring Function | Type | Binding Affinity Prediction (R²) | Enrichment Factor (EF₁%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DockTScore (MLR) [22] | Physics-based + ML | 0.61 | 32.5 |

| DockTScore (RF) [22] | Physics-based + ML | 0.65 | 35.8 |

| DockTScore (SVM) [22] | Physics-based + ML | 0.63 | 34.1 |

| Traditional Empirical [22] | Empirical | 0.45-0.55 | 20-28 |

| Vina [2] | Empirical | 0.51 | 26.3 |

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations model the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing atomic-level insights into protein-ligand interactions that are difficult to obtain experimentally [27]. By solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system, MD simulations can capture conformational changes, binding/unbinding events, and solvation effects critical for understanding drug mechanism of action [21] [1].

In virtual screening workflows, MD serves as a valuable validation tool following docking studies. While docking provides static snapshots of binding, MD simulations assess the temporal stability of protein-ligand complexes through trajectory analyses including root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), and hydrogen bond monitoring [21]. Typical production simulations for drug discovery applications now range from 100 ns to 300 ns, providing sufficient sampling for meaningful thermodynamic analysis [21] [1].

MD simulations have become particularly valuable in optimizing drug delivery systems for cancer therapy, offering insights into drug encapsulation, carrier stability, and release mechanisms for systems including functionalized carbon nanotubes, chitosan-based nanoparticles, and human serum albumin [27].

Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow

A robust virtual screening protocol for oncology drug discovery integrates all three computational components into a cohesive workflow. The process typically begins with target identification and preparation, proceeds through compound screening and docking, and culminates in molecular dynamics validation of top hits.

Virtual Screening Workflow

Protocol: Structure-Based Virtual Screening for Oncology Targets

Objective: To identify potential inhibitors for an oncology target using integrated computational approaches.

Materials and Methods:

Target Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from PDB or AlphaFold (e.g., AF-Q13177 for PAK2) [1].

- Perform protein preprocessing: add hydrogen atoms, optimize hydrogen bonds, remove atomic clashes via energy minimization [25] [1].

- Validate protein structure quality using Ramachandran plots, ERRAT analysis, and per-residue confidence scores (pLDDT) [1].

- Define the binding site coordinates based on known active sites or literature data.

Compound Library Preparation:

- Curate a library of compounds from databases like DrugBank, ZINC, or BIOFACQUIM [1] [28].

- Prepare ligands: generate 3D geometries, assign proper bond orders, and determine correct ionization states at physiological pH using tools like Epik [25] [22].

- Filter compounds based on drug-likeness rules and pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) filters [28].

Molecular Docking:

- Set up docking grid to encompass the entire binding site or specific residues of interest [1].

- Perform docking simulations using software such as AutoDock Vina with appropriate parameters [21] [1].

- Generate multiple poses per ligand (typically 20-30) to ensure adequate sampling of binding modes [28].

- Rank compounds based on docking scores and visual inspection of binding modes.

Post-Docking Analysis:

- Select top candidates based on docking scores and interaction patterns with key residues.

- Analyze protein-ligand interactions using tools like PyMOL and LigPlus to identify hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and π-π stacking [1].

- Filter compounds based on interaction profiles, drug-likeness, and potential toxicity using SwissADME or similar tools [28].

Molecular Dynamics Validation:

- Set up MD system: place the protein-ligand complex in a solvation box, add ions to neutralize the system [1] [23].

- Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes using steepest descent or LBFGS algorithms [23] [28].

- Equilibrate the system in NVT and NPT ensembles for 100-300 ps [23] [28].

- Run production MD simulation for 100-300 ns using GROMACS, AMBER, or Desmond [21] [1].

- Analyze trajectories for RMSD, RMSF, radius of gyration, hydrogen bonding, and binding free energy calculations (MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Virtual Screening

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina [21], DOCK3.7 [24], Glide [25] | Predict protein-ligand binding poses and affinity | Primary virtual screening |

| MD Software | GROMACS [1] [23], Desmond [28] | Simulate temporal behavior of protein-ligand complexes | Binding stability assessment |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36 [23], OPLS 2005 [28], GROMOS 54A7 [1] | Define potential energy functions for atoms | MD simulations |

| Analysis Tools | PyMOL [1], LigPlus [1], RDKit [2] | Visualize and analyze molecular interactions | Post-docking/MD analysis |

| Preparation Tools | Protein Preparation Wizard [25] [22], AutoDock Tools [1] | Prepare protein and ligand structures for calculations | Pre-processing step |

| Machine Learning | VirtuDockDL [2], DockTScore [22] | Enhance scoring and prediction accuracy | Improved virtual screening |

Advanced Applications in Oncology

The integration of docking, scoring, and MD simulations has enabled significant advances in oncology drug discovery. Researchers have successfully applied these methods to identify repurposed drugs for various cancer targets. For instance, a systematic virtual screening of FDA-approved drugs identified Midostaurin and Bagrosin as potential inhibitors of p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2), a serine/threonine kinase involved in cell motility, survival, and proliferation [1]. Similarly, compounds including zavegepant, tucatinib, atogepant, and ubrogepant were identified as promising candidates for repurposing as New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM-1) inhibitors through comprehensive virtual screening and MD simulations [21].

Machine learning approaches are increasingly being integrated into virtual screening workflows. Tools like VirtuDockDL employ graph neural networks to predict the biological activity of compounds based on their structural data, achieving 99% accuracy on the HER2 dataset in benchmarking studies [2]. These approaches can significantly enhance the efficiency and accuracy of virtual screening for oncology targets.

Molecular dynamics simulations have also proven valuable in understanding the mechanisms of environmental carcinogens in cancer development. Studies have explored the toxicological effects of dioxin-like pollutants on liposarcoma, identifying key protein targets and proposing potential therapeutic interventions through integrated computational approaches [23].

The integration of molecular docking, scoring functions, and molecular dynamics simulations creates a powerful pipeline for oncology drug discovery. While each component has its strengths and limitations, their combined use provides a more comprehensive approach to identifying and validating potential therapeutic candidates. As these computational methods continue to evolve, particularly with the integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence, virtual screening workflows will become increasingly accurate and efficient. This progress will further accelerate the discovery of novel oncology therapeutics, ultimately contributing to improved treatment options for cancer patients.

Executing the Screen: Advanced Strategies and Practical Applications

Structure-based virtual screening (VS) has become a cornerstone in modern oncology drug discovery, enabling the rapid and cost-effective identification of novel therapeutic candidates. This approach leverages three-dimensional structural information of defined oncogenic targets to computationally screen vast libraries of small molecules, prioritizing compounds with a high probability of binding and modulating the target's activity. The integration of molecular docking, which predicts the binding orientation and affinity of a small molecule within a target's binding site, has proven particularly valuable for initial hit identification. This protocol details the application of molecular docking within a virtual screening workflow aimed at discovering oncology drug candidates, providing a structured framework from target selection to experimental validation.

Key Applications in Oncology

The following case studies illustrate how molecular docking has been successfully applied to discover inhibitors against various high-value oncogenic targets.

Table 1: Recent Case Studies of Molecular Docking in Oncology Drug Discovery

| Oncogenic Target | Cancer Type | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human αβIII tubulin isotype | Various Carcinomas (Taxol-resistant) | Four natural compounds (e.g., ZINC12889138) identified with exceptional binding affinity and ADMET properties; demonstrated structural stability in MD simulations. | [29] |

| p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2) | Various Cancers (e.g., Breast) | FDA-approved drugs Midostaurin and Bagrosin identified as potent repurposed inhibitors; 300ns MD simulations confirmed stable binding and thermodynamic properties. | [1] |

| Androgen Receptor (AR) | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) | Phytochemical 2-hydroxynaringenin discovered as a potential lead; showed structural stability and high binding affinity in MD and MM-GBSA studies. | [30] |

| PKMYT1 Kinase | Pancreatic Cancer | HIT101481851 identified as a promising inhibitor; stable interactions with key residues (CYS-190, PHE-240) confirmed by MD simulations and in vivo validation. | [31] |

| Multi-Target (PD-L1, VEGFR, EGFR, HER2, c-MET) | Gallbladder Cancer | Natural compound 13-beta, 21-Dihydroxyeurycomanol identified as a common, promising multi-targeted agent with strong binding affinities. | [32] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This section provides a step-by-step methodology for a structure-based virtual screening campaign, drawing from the best practices outlined in the case studies.

Target Selection and Protein Preparation

Objective: To select a clinically relevant oncogenic target and prepare its three-dimensional structure for docking.

- Target Identification: Select a protein target based on its validated role in oncogenesis and disease progression (e.g., βIII-tubulin in taxane resistance [29], PKMYT1 in pancreatic cancer [31]).

- Structure Acquisition: Obtain a high-resolution 3D structure of the target from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). If an experimental structure is unavailable, generate a homology model using tools like Modeller [29].

- Protein Preparation:

- Remove crystallographic water molecules and heteroatoms that may interfere with docking [30].

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign appropriate protonation states at physiological pH (e.g., using Schrodinger's Protein Preparation Wizard [31] or AutoDock Tools [1]).

- Fill in missing loops or side chains if necessary [31].

- Perform energy minimization to relieve steric clashes and optimize the geometry using a force field like AMBER ff14SB [30] or OPLS 2005 [31].

Binding Site Definition and Grid Generation

Objective: To define the spatial coordinates of the binding site for docking calculations.

- Site Identification: The binding site is typically the active site (e.g., the ATP-binding pocket for a kinase like PKMYT1 [31]) or a known allosteric site. The co-crystallized ligand can be used to define the site's center.

- Grid Box Setup: Define a 3D grid box that encompasses the entire binding site and provides sufficient space for ligand movement. The box is characterized by:

- Center Coordinates: The X, Y, Z coordinates at the center of the binding site.

- Box Dimensions: The size of the box in Ångstroms (e.g., 22.5 Å in each direction [33]) or the number of grid points along each axis.

- Example parameters from a study on natural compounds:

Center: X=15.0, Y=12.5, Z=18.3; Dimensions: 60x60x60 points; Spacing: 0.375 Å[33].

Ligand Library Preparation

Objective: To prepare a library of small molecules for docking.

- Library Acquisition: Source compounds from databases such as ZINC (for natural compounds [29]), DrugBank (for FDA-approved drugs [1]), or PubChem [30].

- Ligand Preparation:

Molecular Docking and Pose Prediction

Objective: To computationally screen the ligand library against the prepared target.

- Docking Software Selection: Choose an appropriate docking program such as AutoDock Vina [29] [1] [30], Glide (Schrodinger) [31], or others.

- Parameter Settings:

- Set the exhaustiveness (AutoDock Vina parameter) to a sufficiently high value (e.g., 100-500) to ensure a comprehensive search of the conformational space [30] [33].

- Use a hierarchical docking approach if screening a very large library: first use a fast High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) mode, followed by Standard Precision (SP) and Extra Precision (XP) modes for top hits [31].

- Execution: Run the docking simulation. The output will be a set of predicted binding poses for each ligand, each with an associated docking score (e.g., binding affinity in kcal/mol).

Post-Docking Analysis and Hit Selection

Objective: To analyze docking results and select the most promising hit compounds for further investigation.

- Pose Analysis: Visually inspect the top-ranking poses of the best-scoring ligands. Use visualization software like PyMOL [1] or Biovia Discovery Studio [33] to analyze key interactions (hydrogen bonds, π-π stacking, hydrophobic contacts) with critical amino acid residues in the binding pocket.

- Consensus Scoring: Consider using multiple scoring functions or methods to improve the reliability of hit selection and mitigate the limitations of any single function [34].

- Hit Prioritization: Prioritize compounds based on a combination of factors:

- Favorable docking score (binding affinity).

- Formation of key interactions with residues known to be important for function.

- Desirable physicochemical properties and drug-likeness.

Experimental Validation

Objective: To confirm the predicted activity of the virtual hits through experimental assays.

- In Vitro Testing: Subject the top-ranked virtual hits to biochemical or cell-based assays to determine their half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) and evaluate their ability to inhibit the target or cancer cell proliferation [31].

- In Vivo Validation: For the most promising candidates, proceed to animal models to assess efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity [31].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Virtual Screening Workflow

The following diagram outlines the core computational and experimental stages of a structure-based virtual screening campaign.

Oncogenic Signaling Pathway

This diagram provides a simplified view of key oncogenic targets and their broader signaling context, illustrating the potential for multi-targeted therapy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Structure-Based Virtual Screening

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Application in Workflow | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular Docking Software | Predicts binding poses and affinities of ligands to the protein target. | [29] [1] [35] |

| PyMOL | Molecular Visualization System | Used for protein structure analysis, binding site visualization, and rendering interaction diagrams. | [29] [1] |

| Schrodinger Suite | Integrated Software Suite | Provides tools for protein prep (Protein Prep Wizard), ligand prep (LigPrep), docking (Glide), and MD simulations (Desmond). | [31] |

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics Simulation Package | Simulates the physical movement of atoms over time to assess complex stability and dynamics. | [1] |

| PyRx | Virtual Screening Platform | Integrates docking and screening tools; facilitates batch docking of large compound libraries. | [30] |

| PROCHECK | Structure Validation Tool | Assesses the stereo-chemical quality of protein structures (e.g., homology models). | [29] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Molecular Descriptor Calculator | Generates chemical descriptors and fingerprints for machine learning-based activity prediction. | [29] |

| ProTox-II | Toxicity Prediction Server | Predicts various toxicity endpoints for small molecules using machine learning models. | [30] |

Table 3: Key Databases and Compound Sources

| Resource Name | Content | Use Case | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | 3D Structures of Proteins and Nucleic Acids | Primary source for obtaining the 3D structure of the oncogenic target. | [29] [30] |

| ZINC Database | Commercially Available Compounds for Virtual Screening | Source for large libraries of natural products or drug-like molecules. | [29] |

| DrugBank | FDA-approved Drugs and Drug Targets | Library for drug repurposing studies via virtual screening. | [1] |

| PubChem | Database of Chemical Molecules and Their Activities | Source for bioactive phytochemicals and other compounds. | [30] |

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | Functional Genomics Data Repository | Used for identifying differentially expressed genes as potential novel targets in cancer. | [30] |

In the absence of a three-dimensional (3D) structure for a target protein, ligand-based drug design (LBDD) serves as a fundamental approach for identifying and optimizing oncology drug candidates. [36] This methodology leverages the known chemical and biological information of active ligands that interact with the therapeutic target of interest. By studying these molecules, researchers can infer the structural and physicochemical properties necessary for desired pharmacological activity, creating predictive models to guide the discovery of novel compounds. [36] [37] Within computer-aided drug design (CADD), ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) has become an indispensable frontline tool for efficiently triaging large compound libraries, helping to focus experimental resources on the most promising hits. [38]

The core ligand-based techniques discussed in this application note—Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, pharmacophore modeling, and 2D similarity searching—are particularly powerful for oncology research. They enable the identification of new chemical entities targeting critical pathways in cancer proliferation, survival, and metastasis. These methods excel at pattern recognition and generalization across diverse chemistries, making them invaluable for enriching screening libraries with compounds that have a higher probability of activity. [39] As drug discovery evolves, integrating these ligand-based approaches with structure-based methods and artificial intelligence (AI) is creating more robust and predictive virtual screening workflows. [37]

Core Methodologies and Theoretical Foundations

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR is a computational methodology that quantifies the correlation between the chemical structures of a series of compounds and a specific biological activity. [36] The underlying hypothesis is that similar structural or physiochemical properties yield similar biological effects. [36] The general QSAR workflow involves consecutive steps: First, a set of ligands with experimentally measured biological activity (e.g., IC50 for enzyme inhibition) is identified. The biological activity values are converted to pIC50 (-logIC50) to normalize the data for modeling. [40] Next, molecular descriptors representing various structural and physicochemical properties are calculated for all compounds. Statistical methods are then employed to discover a mathematical correlation between these descriptors and the biological activity. Finally, the developed model is rigorously validated for its statistical stability and predictive power. [36]

Statistical Tools and Validation: The success of a QSAR model depends heavily on the choice of molecular descriptors and the statistical method used to relate them to activity. Common linear regression methods include Multivariable Linear Regression (MLR), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Partial Least Squares (PLS). [36] For non-linear relationships, artificial neural networks, including Bayesian Regularized Artificial Neural Networks (BRANN), can be applied. [36] Model validation is a critical step, typically involving both internal validation (e.g., leave-one-out or k-fold cross-validation to calculate Q²) and external validation using a test set of compounds not used in model building. [36] [40]

Pharmacophore Modeling

A pharmacophore model is an abstract representation of the steric and electronic features that are necessary for molecular recognition of a ligand by its biological target. [36] In ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, the common chemical features from a set of known active ligands are identified and aligned in 3D space. These features typically include hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrophobic areas (H), aromatic moieties (Ar), and charged/ionizable groups. [41] The model captures the essential interaction capabilities of active ligands, independent of their exact molecular scaffold.

This model can then be used as a query to screen large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC) to identify new compounds that possess the same arrangement of chemical features, and are therefore likely to be active. [40] [41] This approach is highly valuable for scaffold hopping—identifying novel chemotypes with potential activity against the same target, which is crucial for overcoming patent restrictions or optimizing drug-like properties. [37]

2D Similarity Searching

2D similarity searching is a foundational LBVS method that operates on the two-dimensional molecular structure, typically represented by a molecular fingerprint—a bit string encoding the presence or absence of specific substructures, atom pairs, or other topological features. The principle is straightforward: molecules that are structurally similar are likely to have similar biological activities. To conduct a search, a known active compound (the "query") is selected, and its fingerprint is compared to the fingerprints of every molecule in a database. Similarity is quantified using metrics like Tanimoto coefficient, with values closer to 1.0 indicating higher similarity. The top-ranked compounds are proposed as potential hits. [37]

Table 1: Key Ligand-Based Virtual Screening Methods and Their Applications

| Method | Core Principle | Primary Use Case in Oncology | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D QSAR | Correlates 2D molecular descriptors with biological activity. | Lead optimization for congeneric series. | Establishes a quantitative and interpretable model for activity prediction. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Identifies essential 3D chemical features for bioactivity. | Scaffold hopping to identify novel chemotypes for a known target. | Not limited to a single scaffold; provides a 3D hypothesis for binding. |

| 2D Similarity Search | Compares molecular fingerprints to find structurally similar compounds. | Identifying close analogs of a known active compound or expanding structure-activity relationships. | Computationally fast, easy to implement, and effective for finding close analogs. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing a validated 2D QSAR Model

This protocol outlines the steps for creating and validating a 2D QSAR model to predict the activity of novel compounds, using a dataset of 4-Benzyloxy Phenyl Glycine derivatives as an example. [40]

Materials and Software:

- Dataset: Curated set of compounds with consistent experimental IC50 values (e.g., from DenvInD database). [40]

- Structure Drawing/Editing: ChemSketch, ACD/Labs. [40]

- Descriptor Calculation: PaDEL-Descriptor software. [40]

- QSAR Model Building: BuildQSAR tool or comparable software (e.g., MATLAB, R). [40]

Procedure:

- Data Curation and Preparation:

- Collect a congeneric series of 80-100 compounds with reliably measured IC50 values from a consistent biological assay. [40]

- Draw the 2D structures of all compounds and perform energy minimization using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., MMFF94). [40]

- Convert IC50 values to pIC50 using the formula: pIC50 = -log10(IC50). This serves as the dependent variable for the model. [40]

Dataset Division:

- Split the dataset randomly into a training set (~80% of compounds) used to build the model and a test set (~20%) used for external validation. Ensure both sets cover a similar range of pIC50 values. [40]

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection:

- Calculate a comprehensive set of 1D and 2D molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, electronic, and physicochemical descriptors) for all compounds in the training set using PaDEL-Descriptor. [40]

- Pre-process descriptors: remove constants and near-constants, and reduce inter-correlated descriptors.

- Select a subset of descriptors that show good correlation with the pIC50 values for model development.

Model Building and Internal Validation:

- Use the BuildQSAR tool with the Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) method to construct models using various combinations of the selected descriptors (typically a maximum of 3-4 to avoid overfitting). [40]

- Select the best model based on statistical parameters: high correlation coefficient (R), low standard error of estimate (s), high Fischer's value (F-test), and statistical significance (p < 0.05). [36]

- Perform internal validation via Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation. Calculate the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) to ensure the model's robustness and predictive power within the training set. [36]

External Model Validation:

- Use the finalized model to predict the pIC50 of the test set compounds, which were not used in model building.

- Calculate the correlation coefficient (R²) between the experimental and predicted pIC50 values for the test set. A high R² indicates a strong predictive model. [40]

Protocol 2: Ligand-based Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

This protocol details the generation of a pharmacophore model from known active ligands and its application in screening compound databases for novel hits.

Materials and Software:

- Active Ligands: 3-5 known high-affinity ligands with diverse structures within the same chemotype. [40]

- Energy Minimization: Avogadro or similar software with MMFF94 force field. [40]

- Pharmacophore Modeling: PharmaGist web server. [40]

- Virtual Screening: ZINCPharmer web server. [40]

Procedure:

- Ligand Selection and Preparation:

- Select the top 3-5 compounds with the highest activity (e.g., pIC50) from your dataset. [40]

- Sketch their 2D/3D structures and perform energy minimization using Avogadro with the steepest descent algorithm and MMFF94 force field to obtain low-energy conformations. Export the final structures in

.mol2format. [40]

Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- Submit the prepared

.mol2files of the active ligands to the PharmaGist server. - Set the maximum number of output pharmacophores to 5. The server will align the input molecules and identify common pharmacophore features (HBA, HBD, H, Ar, etc.). [40]

- Analyze the output and select the highest-ranked pharmacophore model (based on alignment score) that best represents the essential features of all active ligands.

- Submit the prepared

Database Screening with the Pharmacophore:

- Use the selected pharmacophore model as a query in the ZINCPharmer web server to screen the ZINC database or other compatible compound libraries. [40]

- Set appropriate search constraints (e.g., limit molecular weight or logP) to focus on drug-like compounds.

- Execute the search and download the resulting "hit" compounds (those matching the pharmacophore query) in SDF format for further analysis. [40]

Post-Screening Analysis:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Ligand-Based Screening

| Category / Item | Specific Example(s) | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | ZINC Database, Enamine REAL | Sources of commercially available, synthetically accessible compounds for virtual screening. [40] [37] |

| Chemical Structure Tools | ChemSketch (ACD/Labs), Avogadro | Used for drawing, editing, and energy minimization of 2D/3D molecular structures. [40] |

| Descriptor Calculation | PaDEL-Descriptor | Calculates 1D & 2D molecular descriptors from chemical structures for QSAR modeling. [40] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | PharmaGist, ZINCPharmer | Aligns active ligands to generate a shared-feature pharmacophore and screens databases for matches. [40] [41] |

| QSAR Model Building | BuildQSAR Tool | Statistical software for developing and validating multiple linear regression QSAR models. [40] |

| Force Field | MMFF94 (Merck Molecular Force Field) | Used for energy minimization and geometry optimization of small molecules. [40] |

Integrating LBVS into an Oncology Drug Discovery Workflow

Ligand-based approaches are most powerful when integrated into a larger, iterative drug discovery pipeline. The following workflow diagram illustrates how QSAR, pharmacophore models, and 2D similarity can be synergistically combined with structure-based methods and experimental validation to efficiently identify and optimize oncology drug candidates.

This integrated workflow begins with known active ligands derived from experimental screening or literature. Parallel ligand-based screens (2D similarity, pharmacophore, and QSAR) are performed to generate initial virtual hit lists from large compound databases. [39] The results from these different methods are then merged and prioritized using consensus scoring, which helps mitigate the inherent limitations of any single approach. [37] [39] The top-ranking compounds proceed to structure-based refinement, such as molecular docking, to analyze potential binding modes and interactions within the target's active site (if a 3D structure is available). [40] [37] Promising compounds are then filtered using in silico ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) and drug-likeness rules (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) to prioritize molecules with a higher probability of success. [40] [38] Finally, the computationally selected compounds are procured or synthesized and subjected to experimental validation to confirm activity and selectivity, feeding back into the cycle for further optimization.

Ligand-based approaches remain a cornerstone of modern oncology drug discovery, providing powerful, efficient, and cost-effective means to navigate vast chemical spaces. QSAR modeling, pharmacophore screening, and 2D similarity searching each offer unique strengths, from quantitative activity prediction to scaffold hopping and rapid analog identification. As the field progresses, the integration of these classical methods with AI-driven platforms, structure-based design, and robust experimental validation creates a synergistic workflow that significantly enhances the probability of identifying high-quality, novel oncology therapeutics. [38] [37] [39] By adhering to the detailed protocols and strategic workflows outlined in this document, researchers can systematically leverage ligand-based virtual screening to accelerate their oncology drug discovery programs.

In modern oncology drug discovery, the integration of diverse screening technologies and data modalities has become paramount for identifying effective therapeutic candidates. The complexity of cancer biology, characterized by multifaceted signaling pathways, tumor heterogeneity, and evolving resistance mechanisms, demands a holistic approach that transcends traditional single-method screening [42]. Virtual screening technology has emerged as a cornerstone of this integrated approach, enabling researchers to computationally sift through vast compound libraries to identify promising candidates before moving to costly laboratory testing [43]. This paradigm shift accelerates innovation while reducing time-to-market and cutting development costs.

The evolution toward consensus workflows represents a fundamental change in how researchers approach lead compound identification. By developing structured frameworks that combine computational predictions with experimental validation, scientists can achieve higher confidence in candidate selection [44]. This application note details established protocols and methodologies for implementing integrated virtual screening workflows specifically tailored for oncology drug discovery, providing researchers with practical guidance for enhancing their screening capabilities.

Integrated Screening Platforms and Technologies

Core Screening Technologies Comparison

The contemporary oncology drug screening landscape encompasses three primary technological approaches, each with distinct advantages and applications within integrated workflows.

Table 1: Core Screening Technologies in Integrated Oncology Drug Discovery

| Technology | Key Features | Applications in Oncology | Throughput | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Virtual Screening | Computational prediction of compound binding to target structures [43] | Target-specific lead identification, binding affinity prediction [44] | Ultra-high (billions of compounds) | Dependent on quality of target structures |

| Ligand-Based Virtual Screening | Identifies compounds similar to known active ligands [45] | Scaffold hopping, lead optimization, drug repurposing [1] | High (millions of compounds) | Requires known active compounds |

| Pharmacotranscriptomics Screening (PTDS) | Detects gene expression changes after drug perturbation [46] | Mechanism of action analysis, traditional medicine screening | Medium (thousands of compounds) | Requires specialized bioinformatics expertise |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing robust screening workflows requires carefully selected reagents and computational resources that ensure reproducibility and accuracy.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Screening Workflows

| Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function in Workflow | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Resources | AlphaFold Database, RCSB PDB [1] | Provides 3D protein structures for docking | Experimentally validated and predicted structures with quality metrics |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC20, DrugBank FDA-approved compounds [1] [47] | Sources of screening compounds | Curated chemical information, drug-like properties |

| Virtual Screening Software | AutoDock Vina, RosettaVS, Schrödinger Glide [1] [44] | Molecular docking and binding affinity prediction | Flexible receptor handling, consensus scoring |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER, Desmond [1] [47] | Simulation of protein-ligand interactions | Force field parameters, binding stability analysis |

| Specialized Oncology Models | Patient-derived organoids, PDX models [48] | Experimental validation of computational hits | Preservation of tumor microenvironment, clinical relevance |

Integrated Virtual Screening Protocol for Oncology Targets

This section provides a detailed experimental protocol for implementing an integrated virtual screening workflow targeting oncology-related proteins, incorporating both computational and experimental validation components.

The following diagram illustrates the complete integrated screening workflow, showing the sequential relationship between computational and experimental phases:

Stage 1: Target Preparation and Compound Library Curation

Protein Target Preparation

- Objective: Generate a high-quality, biologically relevant protein structure for docking studies

- Procedure:

- Retrieve the target protein structure from RCSB PDB (e.g., PDB ID: 7DY7 for PD-L1) or AlphaFold database (e.g., AF-Q13177 for PAK2) [1] [45]

- Perform protein preprocessing using Maestro Protein Preparation Wizard or similar tools:

- Add missing hydrogen atoms

- Assign correct bond orders

- Fill missing loops and side chains using homology modeling (e.g., MODELLER software) [47]

- Optimize hydrogen bonding networks

- Conduct energy minimization to remove steric clashes using steepest descent algorithm (5,000 steps maximum)

- Validate structure quality using:

Compound Library Preparation

- Objective: Curate diverse, drug-like compound libraries for screening

- Procedure:

- Source compounds from DrugBank (FDA-approved drugs), ZINC20 (lead-like compounds), or in-house libraries [1] [47]

- Prepare ligands using LigPrep or similar tools:

- Generate possible tautomers and protonation states at pH 7.0 ± 2.0

- Generate stereoisomers (up to 32 per compound)

- Optimize 3D geometry using OPLS3 or similar force fields [45]

- Filter compounds based on drug-likeness using Lipinski's Rule of Five and Veber's criteria