A Comprehensive Guide to Molecular Dynamics Simulation Setup for Protein-Ligand Complexes

This article provides a comprehensive guide to setting up and running molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for protein-ligand complexes, a critical technique in structural biology and drug discovery.

A Comprehensive Guide to Molecular Dynamics Simulation Setup for Protein-Ligand Complexes

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to setting up and running molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for protein-ligand complexes, a critical technique in structural biology and drug discovery. It covers foundational principles, from system preparation and force field selection to solvation and neutralization. The guide details step-by-step methodological workflows using popular tools like GROMACS and OpenFE, including energy minimization and equilibration protocols. It addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for enhanced sampling. Furthermore, it explores validation techniques through trajectory analysis and discusses emerging AI-enhanced methods for improving accuracy and efficiency, offering researchers a complete framework for conducting reliable MD simulations.

Understanding the Core Principles of Protein-Ligand MD Simulations

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation has established itself as a foundational technique in computational structural biology, often described as a "computational microscope." It provides atomic-level resolution into the dynamic processes that govern biomolecular function, far beyond the static snapshots available from experimental techniques like X-ray crystallography. For protein-ligand complexes, which are central to drug discovery, MD offers unparalleled insights into binding mechanisms, conformational changes, and allosteric regulation, ultimately guiding the rational design of more effective therapeutics [1] [2].

The power of MD lies in its ability to simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. By solving Newton's equations of motion for every atom in a system, MD trajectories reveal the intricate dance of biomolecules, capturing rare events, transient states, and the fundamental energetics that underlie biological activity [3]. This application note details a standardized protocol for setting up, running, and analyzing MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes, providing researchers with a robust framework to leverage this computational microscope in their work.

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide for Protein-Ligand MD

This section provides a comprehensive methodology for running an MD simulation of a protein-ligand complex, from initial system construction to production simulation.

System Setup and Parameterization

The initial steps involve defining the molecular components and preparing them for simulation with appropriate force fields.

- Component Definition: The system is defined as a

ChemicalSystemcomprising three parts: aProteinComponent(from a PDB file), aSmallMoleculeComponent(the ligand, from an SDF file), and aSolventComponent(specifying ion concentration) [4]. - Force Field Assignment: The protocol uses a hybrid force field approach. The protein is typically parameterized with AMBER forcefields (e.g.,

ff14SB), while the small molecule is assigned parameters using theOpenFFforcefield (e.g.,openff-2.1.1). The solvent model is typically TIP3P water [4]. - Ligand Parameterization: For ligands not covered by standard force fields, AMBER parameters can be derived using the

antechambertool (e.g., with the-cflag for the AM1-bcc charge method). Theparmchk2utility is then used to identify and generate any missing parameters, producing.frcmodand.prepifiles [5]. - System Solvation: The complex is placed in an explicit solvent box (e.g., a cubic box with a 1.2 nm padding distance) using a tool like

OpenMM's Modeller. The system is neutralized with ions (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) [4].

Simulation Configuration and Execution

With the system prepared, the simulation parameters are defined in a series of steps that gradually equilibrate the system before production data is collected. The workflow is designed to relax the system and bring it to the correct thermodynamic state.

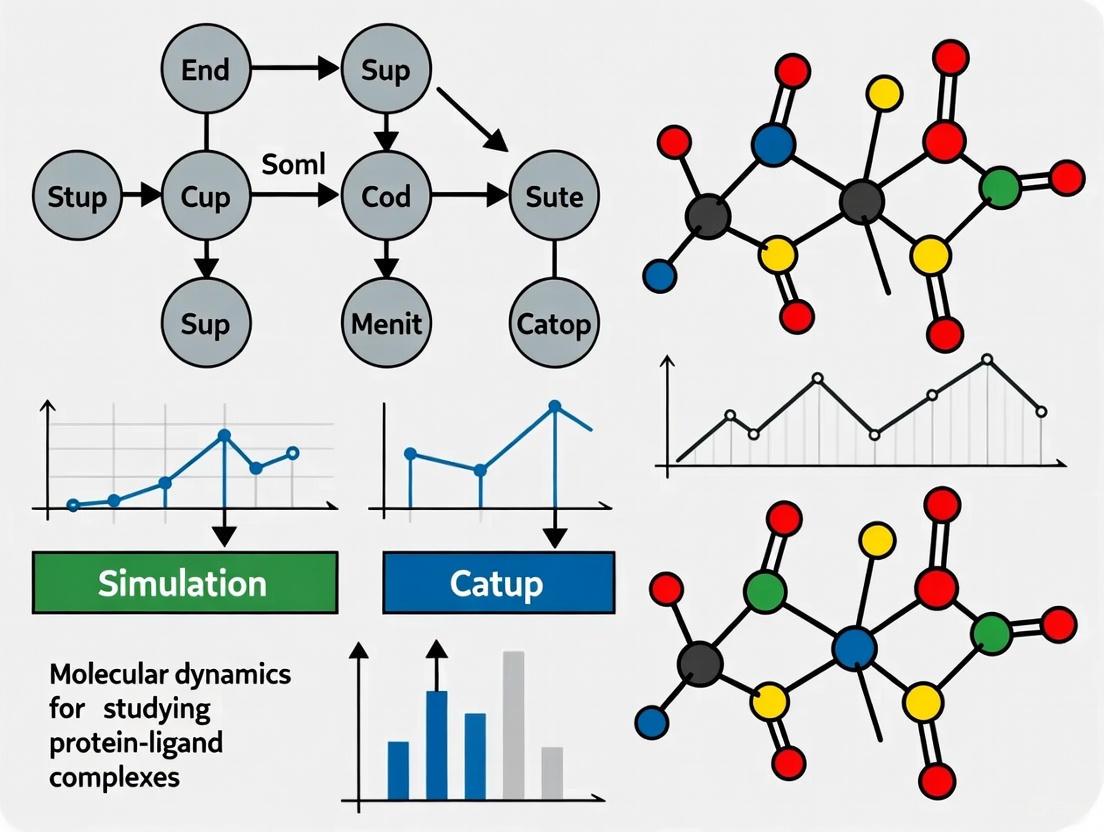

The following diagram illustrates the sequential steps of the MD simulation protocol:

Table 1: Key Settings for MD Simulation Protocol

| Setting Category | Parameter | Typical Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Settings | Minimization Steps | 5000 | Steps for initial energy minimization [4] |

| NVT Equilibration Length | 0.01 ns | Equilibration in the NVT ensemble (constant volume) [4] | |

| NPT Equilibration Length | 0.01 ns | Equilibration in the NPT ensemble (constant pressure) [4] | |

| Production Length | Varies (ns-µs) | Length of the production simulation for analysis [4] | |

| Integrator Settings | Timestep | 4.0 fs | Integration timestep (can be increased with hydrogen mass repartitioning) [4] |

| Temperature | 298.15 K | Simulation temperature [4] | |

| Pressure | 1.0 atm | Simulation pressure (for NPT) [4] | |

| Collision Rate | 1.0 ps⁻¹ | Langevin thermostat collision frequency [4] | |

| Forcefield Settings | Nonbonded Method | PME | Method for handling long-range electrostatics [4] |

| Nonbonded Cutoff | 1.0 nm | Cutoff for short-range nonbonded interactions [4] |

Post-Simulation Analysis and Visualization

After completing the production simulation, the resulting trajectory must be analyzed to extract biologically meaningful insights. A suite of standard analyses can be employed to assess system stability, flexibility, and compactness, and to uncover collective motions.

Table 2: Essential Metrics for MD Trajectory Analysis

| Analysis Metric | Acronym | Description | Biological Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Mean Square Deviation | RMSD | Measures the average change in atom positions relative to a reference structure. | Overall system stability and convergence [6]. |

| Root Mean Square Fluctuation | RMSF | Quantifies the fluctuation of each residue around its average position. | Local flexibility, often of loop regions and binding sites [6]. |

| Radius of Gyration | Rg | Measures the compactness of a protein structure. | Global structural stability and folding [6]. |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area | SASA | Calculates the surface area accessible to a solvent probe. | Changes in solvent exposure, e.g., upon ligand binding. |

| Hydrogen Bond Analysis | H-Bond | Identifies and counts hydrogen bonds over time. | Stability of specific interactions within the complex. |

| Principal Component Analysis | PCA | Identifies large-scale, collective motions in the trajectory. | Functional dynamics and dominant conformational changes [6]. |

| Dynamic Cross-Correlation Matrix | DCCM | Analyzes correlated and anti-correlated motions between residues. | Communication networks within the protein [6]. |

Contact Frequency Analysis withmdciao

Beyond the standard metrics, residue-residue contact frequency is a powerful and intuitive analysis for understanding protein-ligand interactions and binding interfaces. The mdciao Python package specializes in this analysis, providing both a command-line interface and an API for easy, production-ready analysis and visualization [1] [2].

The core of mdciao involves computing the distance between residues (e.g., between the protein binding pocket and the ligand) for every frame of the trajectory. A contact is registered if the distance falls below a cutoff (default: 4.5 Å between heavy atoms). The contact frequency ( f{AB,δ}^i ) for a residue pair (A,B) in trajectory *i* is calculated as:

[

f{AB,δ}^i = \frac{\sum{j=0}^{Nt^i} Cδ[d{AB}^i(tj)]}{Nt^i}

]

where ( Cδ ) is the contact function (1 if ( d{AB} ≤ δ ), 0 otherwise), and ( N_t^i ) is the number of frames in trajectory i [2]. This allows researchers to quickly identify which protein residues consistently interact with the ligand throughout the simulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Successful execution of an MD project relies on a suite of specialized software tools and libraries. The table below catalogs the essential "research reagents" for a typical MD workflow.

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Biomolecular MD Simulations

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenFE | Simulation Setup | Creates, parameterizes, and simulates complex chemical systems. | [4] |

| AmberTools/antechamber | Parameterization | Derives force field parameters for small molecules (ligands). | [5] |

| GROMACS | Simulation Engine | High-performance MD simulation software. | [7] |

| OpenMM | Simulation Engine | Hardware-accelerated MD toolkit, often used via other front-ends. | [4] |

| VMD/Chimera/PyMOL | Visualization | Visual inspection of structures, trajectories, and analysis results. | [7] [2] |

| MDtraj/MDanalysis | Trajectory Analysis | Python libraries for efficient analysis of MD data. | [1] [2] |

| mdciao | Specialized Analysis | User-friendly analysis and plotting of residue-residue contacts. | [1] [2] |

| Matplotlib/Grace | Plotting & Graphing | Creation of publication-quality figures from analysis data. | [7] |

Concluding Remarks

Molecular Dynamics simulations serve as a powerful computational microscope, revealing the dynamic nature of biomolecular complexes that is often invisible to other techniques. The standardized protocol outlined here—from system setup with OpenFE and AmberTools, through simulation with OpenMM or GROMACS, to analysis with mdciao and other tools—provides a robust and reproducible framework for researchers. By applying this protocol, scientists in drug development can gain deep insights into mechanisms of action, identify key interaction residues, and ultimately accelerate the design of novel therapeutics.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes, the biological system is represented by several key components that together create a computationally tractable model mimicking a physiological environment. A typical system includes the protein macromolecule, the small molecule ligand, water solvent molecules, and ions to neutralize the system's charge and establish physiological ionic strength. Properly defining and parameterizing each of these components is essential for simulating biologically relevant behavior and obtaining accurate insights into binding mechanisms, dynamics, and energetics. MD simulations provide a powerful approach for investigating the structural and dynamical properties of a protein-ligand system, capturing interactions and energy exchanges between the protein, ligand, and solvent that dictate the binding event through both long-range and short-range interactions [8]. The setup process involves carefully preparing each component, assigning appropriate force field parameters, solvating the system in a periodic box, and adding ions to achieve electrochemical stability before embarking on energy minimization and equilibration phases.

Component Specifications and Parameters

Quantitative System Parameters

Table 1: Standard Force Field Parameters for System Components

| Component | Force Field | Parameter Source | Water Model | Ionic Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | AMBER ff14SB [9] [8] | Internal to force field | TIP3P [9] [8] | 0.15 M NaCl [4] |

| Ligand | GAFF2 [8] | Antechamber [8] | TIP3P | Neutralizing ions + 0.15 M NaCl |

| Cofactors | GAFF2 [9] | Antechamber [8] | TIP3P | System-dependent |

| Solvent (Water) | - | - | TIP3P [9] [4] [8] | - |

| Ions | - | Built-in ion parameters | - | 0.15 M NaCl or system-specific |

Table 2: System Setup and Simulation Parameters

| Parameter | Minimization | Equilibration (NVT) | Equilibration (NPT) | Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Time | 1000-5000 steps [4] [8] | 10-100 ps [4] [8] | 10 ps-2 ns [4] [8] | 20 ps-4 ns+ [4] [8] |

| Temperature Control | - | Langevin thermostat [8] | Langevin thermostat [8] | Langevin thermostat [8] |

| Temperature | - | 50-300 K [8] | 300 K [4] [8] | 300 K [4] |

| Pressure Control | - | - | Monte Carlo barostat [8] | Monte Carlo barostat [8] |

| Pressure | - | - | 1 atm [8] | 1 atm [8] |

| Constraints | Backbone (10 kcal/mol/Ų) [8] | Backbone atoms [8] | Possibly none | None |

| Timestep | - | 2 fs [8] | 2-4 fs [4] [8] | 2-4 fs [4] [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure File (PDB) | Starting conformation of the macromolecule | PDB file with missing residues completed, alternative locations resolved, and protonation states checked [9] |

| Ligand Structure File (SDF/MOL) | Small molecule whose binding is being investigated | Structure aligned with protein coordinates, parameterized with GAFF2 [9] [8] |

| Force Fields (AMBER ff14SB, GAFF2) | Mathematical representation of interatomic forces | AMBER ff14SB for proteins [9] [8], GAFF2 for ligands [8] |

| Water Model (TIP3P) | Solvent representation with specific electrostatic properties | Explicit water molecules added to solvate the system [9] [4] [8] |

| Ions (Na+, Cl-) | Neutralize system charge and mimic physiological conditions | Added to achieve 0.15 M ionic concentration [4] |

| Cofactors | Essential non-protein components required for function | Parameterized with GAFF2 and included in the system [9] |

| Protonation State Tools | Determine correct ionization states at specific pH | H++ server for physiological pH 7.4 [8] or pdb2gmx for histidine protonation [9] |

Experimental Protocol: System Setup

Step-by-Step Methodology

The following protocol describes the comprehensive setup of a protein-ligand complex system for molecular dynamics simulations, incorporating best practices from established methodologies and tools.

Step 1: Initial System Preparation

- Obtain the protein structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and perform necessary preprocessing:

- Complete missing residues and reconstruct missing loops using tools like UCSF Chimera [8]

- Resolve alternative residue locations and remove co-crystallized ligands and water molecules [9]

- Protonate the protein at physiological pH (7.4) using H++ server [8] or

gmx pdb2gmx[9] - Explicitly check and set protonation states of histidine residues (HIE, HID, or HIP) [9]

- Prepare the ligand structure in MOL or SDF format with coordinates aligned to the protein [9]

Step 2: Force Field Assignment and Parameterization

- Assign AMBER ff14SB force field to the protein [9] [8]

- Parameterize the ligand using General AMBER Force Field (GAFF2) via antechamber program [8]

- For systems with cofactors, assign parameters using GAFF2 [9]

- Assign partial charges to the ligand using AM1-BCC method [4]

Step 3: Solvation and Ion Addition

- Solvate the complex in an orthorhombic TIP3P water box with a 10-12 Å extension from the protein surface [4] [8]

- Add counter ions to neutralize the system charge [8]

- Add additional ions to achieve physiological ionic concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) [4]

Step 4: Energy Minimization

- Perform minimization using the L-BFGS minimizer [8]

- Apply a harmonic potential to protein backbone atoms (force constant: 10 kcal/mol/Ų) [8]

- Conduct 1000-5000 minimization steps, gradually reducing restraint force [4] [8]

- Perform additional minimization without restraints [8]

Step 5: System Equilibration

- Gradually heat the system from 50 K to the target temperature (300 K) while maintaining backbone restraints [8]

- Perform NVT equilibration for 10 ps-1 ns at the target temperature [4] [8]

- Conduct NPT equilibration for 10 ps-2 ns at target temperature and pressure (1 atm) [4] [8]

- Use a Langevin thermostat with a friction coefficient of 5 ps⁻¹ [8] and Monte Carlo barostat [8]

- Apply constraints to bonds involving hydrogen atoms [8]

Step 6: Production Simulation

- Run production simulation in the NPT ensemble at 300 K and 1 atm pressure [8]

- Use a 2-4 fs timestep [4] [8]

- Save trajectories at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) for analysis [8]

Workflow Visualization

MD System Setup Workflow

Advanced Applications and Methodologies

Binding Affinity Calculation Protocol

For researchers interested in computing protein-ligand binding affinities from MD simulations, the following protocol based on the Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MMPBSA) method can be implemented:

Step 1: Simulation Preparation

- Follow the standard system setup protocol outlined in Section 3.1

- Run multiple independent production simulations (typically 5) for each protein-ligand complex [8]

- Ensure sufficient sampling with production runs of at least 4 ns per replicate [8]

Step 2: Trajectory Processing

- Extract snapshots from trajectories at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) [8]

- Ensure consistency in frame selection across all replicates

Step 3: MMPBSA Calculation

- Use the single trajectory approach where receptor and ligand contributions are computed from each individual trajectory [8]

- Calculate the binding affinity using the equation: ΔGbind = ΔEMM + ΔGsol [8] where:

- Consider explicit water molecules near the active site in calculations [8]

Step 4: Result Interpretation

- Average binding affinities across all independent simulations [8]

- Compare with experimental values where available

- Use results for machine learning applications or drug discovery prioritization [8]

High-Throughput and Automated Approaches

For research requiring higher throughput, automated pipelines like StreaMD can significantly streamline the process:

- Distributed Computing: Utilize Dask library for parallel execution across multiple servers or clusters [9]

- Automated Processing: The tool automatically handles file hierarchy, checkpointing, and continuation of interrupted runs [9]

- Batch Processing: Run multiple protein-ligand systems simultaneously with efficient resource allocation [9]

- Integrated Analysis: Direct computation of MM-GBSA/PBSA binding free energies and interaction fingerprints [9]

High-Throughput MD Screening

In the realm of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes, the selection of appropriate force fields (FFs) is a foundational step that directly influences the physical accuracy and predictive power of the computational study. For researchers in structural biology and drug development, this choice dictates the reliability of insights into molecular recognition, binding affinity, and dynamics. The force field provides the mathematical model that describes the potential energy of the system as a function of the nuclear coordinates, encompassing terms for bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals, electrostatics). The central challenge lies in selecting and applying a combination of protein and ligand force fields that are thermodynamically consistent with each other and with the chosen water model, ensuring a balanced representation of all components in the simulation. This application note provides a structured framework, supported by recent benchmarking data and practical protocols, to guide this critical selection process for protein-ligand systems.

Performance Comparison of Major Force Field Combinations

Systematic evaluations of popular force fields provide essential guidance for selection. A study on the flavodoxin/flavin mononucleotide system compared several force fields for their ability to reproduce experimental NMR data (³J couplings) and relative binding free energies [10].

Table 1: Performance of Protein Force Fields in Reproducing Backbone and Side Chain ³J Couplings (RMSD in Hz) [10]

| Protein Force Field | All Residues (Backbone) | Residues within 7.5 Å of Ligand (Backbone) | All Residues (Side Chain χ₁) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS-AA/M | ~0.6 – 0.8 | ~0.6 – 0.8 | ~1.0 – 1.1 |

| AMBER ff14SB | ~0.6 – 0.8 | ~0.6 – 0.8 | ~1.0 – 1.1 |

| CHARMM36 | ~0.6 – 0.8 | Markedly higher | ~1.0 – 1.1 |

| AMBER ff99SB-ILDN | Good | Good | Good |

| CHARMM22/CMAP | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive |

| OPLS-AA (original) | Significantly less well | Significantly less well | Significantly less well |

The table shows that newer force fields (OPLS-AA/M, AMBER ff14SB, CHARMM36) generally perform well for the overall protein structure. However, OPLS-AA/M and AMBER ff14SB demonstrated superior performance for protein residues in the immediate vicinity of the ligand, a critical region for binding interactions [10].

The same study also evaluated the accuracy of relative binding free energy (ΔΔG) calculations for protein mutants, with key results summarized below.

Table 2: Accuracy in Relative Binding Free Energy (ΔΔG) Calculations (kcal/mol) [10]

| Force Field Combination (Protein//Ligand) | WT → G61A | G61A → G61L | G61A → G61V | Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.0 |

| OPLS-AA/M//OPLS/CM5 | 0.55 ± 0.76 | 0.27 ± 0.77 | 0.11 ± 1.32 | 0.36 |

| C22 CMAP//CGenFF | 1.53 ± 0.98 | 0.30 ± 0.77 | 0.52 ± 0.81 | 0.37 |

| OPLS-AA/M//OPLS/CM1A | -0.04 ± 0.66 | 1.01 ± 0.85 | -0.02 ± 1.09 | 0.63 |

| CHARMM36//CGenFF | 2.26 ± 0.75 | 1.00 ± 0.62 | -0.89 ± 0.94 | 1.12 |

| OPLS/AA//OPLS/CM1A | -2.81 ± 0.61 | -1.03 ± 1.52 | 2.49 ± 1.12 | 2.38 |

A larger-scale study systematically tested 12 different AMBER force field combinations for relative binding free energy calculations across 80 alchemical transformations [11]. The results indicated that while no single combination was statistically superior, the combination of ff14SB for the protein, GAFF2.2 for the ligand, and the TIP3P water model performed best, yielding a mean unsigned error (MUE) of 0.87 kcal/mol and a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 1.22 kcal/mol [11]. Consensus scoring, which averages results from multiple force fields, was also shown to improve accuracy and robustness [11].

Practical Application and Workflow Protocols

A Protocol for MD Simulation of a Protein-Ligand Complex

The following protocol, based on the OpenFE PlainMDProtocol, outlines the key steps for setting up and running an MD simulation for a protein-ligand complex [4].

Diagram: Workflow for Protein-Ligand MD Simulation

The workflow involves several key steps, from system definition to production simulation [4]:

- Define the Chemical System: The protein, ligand, and solvent are defined as separate components and combined into a

ChemicalSystemobject. - Configure Force Field and Simulation Settings: Critical settings include:

forcefield_settings: Specifies the protein force field (e.g.,amber/ff14SB.xml), small molecule force field (e.g.,openff-2.1.1orGAFF), water model (e.g.,amber/tip3p_standard.xml), and non-bonded treatment (e.g., PME with a 1.0 nm cutoff) [4] [12].thermo_settings: Sets the temperature (e.g., 298.15 K) and pressure (e.g., 1 atm).simulation_settings: Determines the length of minimization and equilibration phases, and the production run.integrator_settings: Defines the timestep (e.g., 4 fs with hydrogen mass repartitioning) and barostat frequency [4].

- Parameterization: The chosen force fields are applied to the system components. Tools like

GAFFTemplateGeneratorcan be used to generate parameters for the ligand on the fly if they are not pre-parameterized [12]. - Minimization and Equilibration: The system's energy is minimized, followed by equilibration first in the NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) and then in the NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensemble to stabilize temperature and density.

- Production MD and Analysis: The production phase is run, and trajectories are analyzed for properties of interest.

Force Field Selection and Compatibility Guidelines

Diagram: Force Field Selection and Compatibility Logic

The decision logic emphasizes the paramount importance of force field compatibility. It is strongly advised to use protein and ligand force fields developed within the same ecosystem [13]. For example:

- CHARMM Ecosystem: Use the CHARMM36 protein force field with the CGenFF force field for ligands and the TIP3P water model [10] [14].

- AMBER Ecosystem: Use the AMBER ff14SB or ff19SB protein force field with the GAFF (Generalized Amber Force Field) for ligands, alongside a compatible water model like TIP3P or OPC [11] [12].

Mixing force fields from different ecosystems, such as applying CHARMM36 to a protein and GAFF to a ligand, is not recommended as they have different parameterization philosophies and may lead to physically inaccurate results [13].

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Resources for Force Field Application

| Tool / Resource | Primary Function | Relevant Force Field Ecosystem |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM-GUI | Web-based platform for building complex simulation systems, including membranes and ligands. Supports AMBER and CHARMM force fields. [11] [15] | CHARMM, AMBER |

| OpenMM ForceFields | Python package providing AMBER, CHARMM, and Open Force Fields for use with OpenMM. Includes generators for GAFF and SMIRNOFF small molecule parameters. [12] | AMBER, CHARMM, OpenFF |

| GAFFTemplateGenerator | A tool for on-the-fly parameterization of small molecules using GAFF within OpenMM workflows. [12] | AMBER |

| AmberTools antechamber | A suite of programs, including antechamber, used to parameterize small molecules with GAFF and assign AM1-BCC partial charges. [12] |

AMBER |

| CGenFF Program | Web-based and standalone program for generating CHARMM-compatible parameters and topology files for small molecules. [13] | CHARMM |

| GROMACS | A versatile MD simulation package supporting AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS force fields with specific .mdp parameter settings. [14] |

Multiple |

The careful selection of compatible force fields is a critical determinant of success in MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes. Benchmarking studies indicate that modern force fields like ff14SB, CHARMM36, and OPLS-AA/M, when paired with their corresponding ligand force fields (GAFF2.2 and CGenFF, respectively), can yield highly accurate results for both structural dynamics and binding free energies. The provided protocols, decision logic, and toolkit offer a practical roadmap for researchers to implement these best practices, thereby enhancing the reliability of their computational findings in drug discovery and structural biology.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in computational biophysics and drug discovery, enabling researchers to study protein-ligand interactions at an atomic level with high temporal resolution [16] [17]. The reliability of these simulations critically depends on the initial setup phase, where the molecular system is prepared, parameterized, and solvated before production runs can begin. This application note provides a detailed, practical protocol for setting up MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes, framed within the context of a broader thesis on advancing computational methodologies for drug development. We present a standardized workflow from initial Protein Data Bank file to a fully solvated simulation system, incorporating best practices for force field selection, topology generation, and system equilibration.

The intricate process of system setup requires careful attention to numerous technical details that can significantly impact simulation outcomes. Proper parameterization of ligands, compatibility between force field components, adequate solvation, and appropriate ion concentration represent just a few of the critical considerations that researchers must address [18] [19]. This protocol aims to demystify this process by providing a comprehensive, step-by-step guide that integrates current methodologies and addresses common pitfalls encountered when preparing biological systems for molecular dynamics simulations.

Theoretical Background

Molecular Dynamics Principles

Classical all-atom molecular dynamics simulations solve Newtonian equations of motion for each atom in the system, requiring three fundamental components: initial coordinates, a potential energy function, and algorithms for numerical integration [16]. The potential energy is described by a force field, which contains parameters for bonded interactions and non-bonded interactions. Modern force fields have evolved through years of refinement to accurately represent complex biomolecular systems, with the most widely used being CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, and OPLS-AA [16] [19].

The simulation process begins with energy minimization to relieve steric clashes and improper geometries, followed by gradual heating and equilibration to bring the system to the target temperature and density. Only after proper equilibration should production simulations begin, as starting from an unrelaxed system can lead to unrealistic dynamics or simulation instability [16]. Throughout this process, various algorithms maintain constant temperature and pressure, with particle mesh Ewald methods typically handling long-range electrostatic interactions in periodic systems [16].

The Critical Role of Water in Protein-Ligand Interactions

Water molecules play an essential role in mediating protein-ligand interactions through bridging hydrogen bonds and contributing to ligand solvation [20]. The behavior of water molecules in binding sites ranging from highly mobile to tightly bound makes accurate binding free-energy estimation challenging in MD simulations. Inadequate sampling of water reorganization can bias computed affinities and obscure key interactions [20]. Advanced sampling techniques and polarizable force fields are increasingly being employed to better capture these complex solvation dynamics, though explicit solvent models remain the gold standard for conventional MD simulations [16] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for setting up a molecular dynamics simulation system for a protein-ligand complex, from initial structure preparation to a production-ready solvated system.

Materials and Methods

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential software tools, force fields, and resources required for setting up molecular dynamics simulations of protein-ligand complexes.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Simulation Setup

| Category | Item | Function/Description | Examples/Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Suites | Simulation Packages | Core engines for running MD simulations | CHARMM [16], AMBER [16], GROMACS [16] [18], NAMD [16] |

| Visualization Tools | Molecular visualization and analysis | VMD [16] [21], PyMOL [22] [21] | |

| Force Fields | Protein Force Fields | Parameters for protein energetics and connectivity | CHARMM36 [16], AMBER [16], GROMOS 54A7 [18] |

| Ligand Force Fields | Specialized parameters for small molecules | CGenFF [19], GAFF [19], ATB [18] [19] | |

| Parameterization Tools | Automated Servers | Web-based ligand parameterization | CGenFF Server [19], ATB [18] [19], PRODRG [19] |

| Standalone Programs | Local parameterization tools | Antechamber [19], Acpype [19] | |

| Solvent Models | Explicit Solvent | Explicit water molecules | SPC [18], TIP3P, TIP4P |

| Implicit Solvent | Continuum dielectric models | Generalized Born [16] |

Force Field Selection Guidelines

Choosing an appropriate force field is crucial for obtaining physically meaningful simulation results. The following table compares major force fields and their characteristics to guide selection.

Table 2: Force Field Comparison and Selection Guidelines

| Force Field | Class | Ligand Parameterization | Strengths | Compatible Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM [16] [23] | All-atom | CGenFF Server [19] | Optimized for biomolecules; polarizable versions available | CHARMM, NAMD, GROMACS |

| AMBER [16] | All-atom | GAFF/Ante-chamber [19] | Excellent for nucleic acids; widely used | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD |

| GROMOS [18] [19] | United-atom | ATB [18] [19] | Computational efficiency; validated for condensed phase | GROMACS |

| OPLS-AA [19] | All-atom | LigParGen [19] | Optimized for liquids; good for organic molecules | GROMACS, NAMD |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Initial Structure Preparation

Protein Preparation from PDB File

- Obtain initial coordinates from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through homology modeling [16].

- Remove unwanted heteroatoms (non-studied ligands, crystallographic additives) while preserving essential cofactors.

- Add missing residues or side chains using modeling tools if necessary.

- Assign appropriate protonation states for histidine residues and other ionizable groups based on physiological pH and local environment.

Ligand Preparation

- Extract ligand coordinates from the complex or obtain them from chemical databases.

- Add hydrogen atoms using molecular building software such as Avogadro [19].

- Generate a Sybyl Mol2 file format with correct atom types and bonding, ensuring consistent residue naming and numbering [19].

- For the OPLS, AMBER, and CHARMM force fields, partial charges are typically derived from quantum mechanical calculations, while GROMOS force fields rely on empirical fitting of condensed-phase behavior [19].

Topology Generation and Parameterization

Protein Topology Generation

- Use the

pdb2gmxtool in GROMACS or equivalent functionality in other MD packages with the selected force field. - This step generates the protein topology containing atom types, masses, charges, and bonded parameters.

- Use the

Ligand Parameterization

- For CHARMM force fields, use the CGenFF server to obtain topology and parameter files for the ligand [19].

- For GROMOS force fields, use the Automated Topology Builder (ATB) with the specific GROMOS54A7_ATB version to ensure atom type compatibility [18].

- Carefully review the penalty scores for assigned parameters when using CGenFF, with values >10 indicating potential need for manual optimization [19].

- Include the ligand topology in the main topology file after the protein topologies, following the sequence defined in the

[molecules]section [18].

System Solvation and Ion Addition

Solvent Model Selection

- Choose between explicit solvent models (e.g., SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P) or implicit solvent models (Generalized Born) based on the research objectives [16].

- For explicit solvation, use a triclinic or dodecahedral box with a minimum 1.0 nm distance between the protein and box edges.

- Utilize tools like VMD's solvate package or GROMACS'

solvateto add water molecules [16].

System Neutralization and Ion Concentration

- Add counterions to neutralize the system net charge using tools like VMD's autoionize or GROMACS'

genion[16]. - Include additional ions to achieve physiological concentration (typically 0.15 M NaCl).

- Replace water molecules with ions rather than adding them to vacant spaces to maintain proper system density.

- Add counterions to neutralize the system net charge using tools like VMD's autoionize or GROMACS'

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Energy Minimization Protocol

- Use steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm for 5,000-50,000 steps until the maximum force drops below 1000 kJ/mol/nm.

- This step relieves steric clashes and improper geometry introduced during system setup.

System Equilibration

- Perform equilibration in two phases: NVT (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) followed by NPT (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature).

- Apply position restraints on protein heavy atoms during equilibration to allow solvent relaxation without protein deformation.

- Gradually heat the system to the target temperature (typically 310 K for physiological conditions) over 100-500 ps.

- Use a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) to maintain constant temperature and pressure [16].

Troubleshooting and Validation

Common Issues and Solutions

Several common issues may arise during system setup that can affect simulation stability and results:

Force Field Atom Type Errors: The error "Atomtype CAro not found" indicates incompatibility between ligand parameters and the chosen force field [18]. This frequently occurs when using ligand topologies from servers like ATB with standard force field versions rather than the specifically adapted versions. Solution: Ensure you download and use the force field version specifically designed for use with the parameterization server (e.g., GROMOS54A7_ATB for ATB-generated ligands) [18].

Topology Sequence Errors: Incorrect ordering of topology file inclusions can cause simulation failures. Solution: List molecules in the

[molecules]section in the same order they appear in the coordinate file, with ligand topology files included after protein topologies if the ligand appears after the protein in the[molecules]section [18].Charge Neutralization Issues: Systems with significant net charge may exhibit unstable behavior during equilibration. Solution: Always neutralize system charge with counterions before adding salt ions, and verify the final system charge is zero unless specifically studying charged systems.

System Validation

Before proceeding to production simulations, validate the prepared system through several checks:

- Energy Minimization Convergence: Confirm the potential energy and maximum force have plateaued to low values.

- Equilibration Stability: Monitor temperature, pressure, and density during NVT and NPT equilibration to ensure stable fluctuations around target values.

- Structural Integrity: Calculate the root-mean-square deviation of protein backbone atoms relative to the starting structure to verify the protein maintains its fold during equilibration [16].

- Solvation Shell: Visualize the system to ensure complete solvation without undesired voids, particularly in the binding site region.

Advanced Applications

Enhanced Sampling for Binding Studies

Advanced sampling techniques can be employed to study protein-ligand binding mechanisms more efficiently:

Lambda-ABF-OPES: This integrated enhanced-sampling framework combines λ-dynamics, multiple-walker adaptive biasing force, and on-the-fly probability enhanced sampling to enable efficient rehydration of the binding site and robust sampling of water exchange events without explicitly including water-related collective variables [20].

Brownian Dynamics-Molecular Dynamics Multiscale Approaches: Combining BD and MD simulations enables accurate calculation of association rate constants (k~on~) while accounting for induced fit during binding [24]. This approach uses BD to simulate long-range diffusion and encounter complex formation, followed by MD to capture short-range interactions and molecular flexibility [24].

Visualization and Analysis

High-quality visualization is essential for interpreting and presenting simulation results:

PyMOL Rendering Techniques: Utilize commands like

set ray_trace_mode=1for black outlines,set ray_shadows=0to remove shadows, andutil.performance(0)for highest quality rendering [22]. Employray 2400,2400followed bypng filename.png, dpi=1000, ray=1to generate high-resolution images [22].Trajectory Analysis in VMD: Align structures using the RMSD Trajectory Tool, visualize multiple frames simultaneously through the Representations menu, and use different coloring methods like "Timestep" to highlight conformational changes [21].

Defining Simulation Box Size and Shape with Appropriate Margin (e.g., 10 Å padding)

In the context of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for protein-ligand complex research, the initial setup of the simulation system is a critical determinant of success. Properly defining the simulation box size and shape with appropriate margins represents a foundational step in this process, directly influencing simulation stability, accuracy, and computational efficiency. An optimally constructed box ensures sufficient solvation of the biomolecular complex while minimizing unnecessary computational overhead from excessive solvent molecules. For protein-ligand systems, this balance is particularly crucial as it affects the accurate representation of solvent-mediated interactions and binding thermodynamics. This protocol outlines evidence-based methodologies for determining optimal simulation box parameters, with specific attention to the requirements of protein-ligand systems in drug development research.

Quantitative Guidelines for Box Size Determination

Systematic analysis of ligand binding poses generated by molecular docking software reveals a direct correlation between ligand size and optimal search space dimensions. Research demonstrates that the highest accuracy in binding pose prediction is achieved when the dimensions of the search space are approximately 2.9 times larger than the radius of gyration (Rg) of the docking compound [25]. This optimized docking box size has been shown to improve not only pose prediction but also compound ranking in virtual screening benchmarks [25].

Table 1: Key Box Size Parameters for Molecular Simulations

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Box size to Rg ratio | 2.9 × Rg | Optimal ligand docking accuracy [25] |

| Minimum box size | 22.5 Å (default in AutoDock Vina) | Default protocol for ligand docking [25] |

| Solvent padding | 1.0 - 1.2 nm | Typical MD setup for protein-ligand systems [4] |

| Ionic concentration | 0.15 M NaCl | Physiological conditions in MD setup [4] |

For molecular dynamics simulations, practical implementation typically involves adding a solvent padding region around the solute. The OpenFE MD protocol, for instance, utilizes a default solvent padding of 1.2 nanometers [4]. This ensures that the protein-ligand complex remains properly solvated throughout the simulation while maintaining manageable system size.

Table 2: Recommended Padding Guidelines for Different Simulation Types

| Simulation Type | Recommended Padding | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-ligand MD (explicit solvent) | 1.0 - 1.2 nm | Balances solvation with computational efficiency [4] |

| Docking simulations | 2.857 × Rg | Maximizes pose prediction accuracy [25] |

| Membrane protein systems | Varies by bilayer thickness | Accommodates lipid bilayer and hydration layers |

Experimental Protocols for Box Size Implementation

Protocol 1: Determining Optimal Docking Box Size

Principle: This protocol leverages the relationship between ligand radius of gyration and optimal search space size to maximize docking accuracy for protein-ligand systems [25].

Methodology:

- Ligand Preparation: Generate a single low-energy conformer of the query ligand. Studies show that the radius of gyration calculated from a single low-energy conformer highly correlates (Pearson correlation coefficient: 0.89) with the average Rg computed from multiple random rotamers [25].

- Radius of Gyration Calculation: Compute the radius of gyration (Rg) of the prepared ligand using standard computational chemistry tools. The radius of gyration describes the dimensions and mass distribution of the molecule [25].

- Box Size Calculation: Calculate the optimal box edge length using the formula: Box Size = 2.857 × Rg [25].

- Box Placement: Center the cubic box on the binding site of interest, whether defined by experimental complex structures or predicted binding pockets [25].

Validation: Benchmarking against a non-redundant dataset of 3,659 protein-ligand complexes from the Protein Data Bank showed this protocol improves average RMSD from 4.9 Å (default protocol) to 4.0 Å, increases the fraction of recovered binding residues from 0.78 to 0.92, and enhances the fraction of recovered specific contacts from 0.44 to 0.58 [25].

Protocol 2: MD System Setup with Appropriate Solvation

Principle: This protocol outlines comprehensive steps for setting up a solvated simulation system for protein-ligand complexes using modern MD workflow tools [4].

Methodology:

- System Definition: Create a

ChemicalSystemobject containing the protein, ligand, and solvent components [4]. - Forcefield Selection: Apply appropriate force fields (e.g., AMBER ff14SB for proteins, openff-2.1.1 for small molecules, TIP3P for water) [4].

- Solvation: Add solvent water molecules with a padding of 1.0-1.2 nm around the solute, employing a cubic box shape for isotropic systems [4].

- Neutralization: Add ions to achieve physiological concentration (typically 0.15 M NaCl) and neutralize system charge [4].

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization (typically 5,000 steps) to relieve steric clashes [4].

- Equilibration: Conduct stepwise equilibration beginning with NVT ensemble (typically 10 ps) followed by NPT ensemble (typically 10 ps) to stabilize temperature and density [4].

- Production MD: Run production simulation with appropriate parameters (timestep of 4 fs, temperature of 298.15 K, pressure of 1 atm) [4].

Diagram 1: MD System Setup Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential steps for preparing a solvated simulation system for protein-ligand complexes, highlighting the critical solvation step where box size and padding are determined.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Simulation Box Setup

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking with customizable box size | Ligand pose prediction and virtual screening [25] |

| OpenFE | Automated setup of MD simulations | End-to-end workflow management for protein-ligand MD [4] |

| AMBER/AmberTools | MD simulation package with pdb4amber utility | System preparation and topology building [26] |

| GROMACS | High-performance MD simulation package | Production MD simulations with various box types [27] |

| BioExcel Building Blocks | Workflow components for biomolecular simulation | Automated system setup pipelines [26] |

Proper definition of simulation box size and shape with appropriate margin represents a critical parameter in molecular dynamics studies of protein-ligand complexes. The guidelines presented here, based on systematic benchmarking studies, provide researchers with evidence-based protocols for optimizing this fundamental aspect of simulation setup. Implementation of these standards across drug discovery research programs promises to enhance the reliability and accuracy of molecular simulations in structure-based drug design.

A Step-by-Step Workflow for Running Protein-Ligand MD Simulations

Within the framework of molecular dynamics (MD) simulation setup for protein-ligand complexes, initial structure preparation forms the critical foundation for all subsequent computational analysis and drug discovery efforts. The accuracy of simulations predicting ligand binding affinities, protein flexibility, and molecular recognition events depends entirely on the quality and physicochemical correctness of the starting atomic coordinates and force field parameters. Researchers often obtain initial protein-ligand structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB); however, these structures frequently contain various issues that must be remediated before they can be used in reliable MD simulations. These issues include missing atoms, non-standard residue naming, spatial errors, incomplete ligand descriptions, and improper protonation states. This application note provides a comprehensive guide to navigating the PDB remediation landscape and details robust protocols for ligand parameterization, enabling researchers to generate simulation-ready systems for studying protein-ligand interactions.

Understanding and Correcting PDB File Issues

The worldwide PDB (wwPDB) actively maintains and improves the structural archive through systematic remediation projects. Understanding these efforts helps researchers anticipate and correct common issues in PDB files before employing them in MD simulations.

Common PDB Remediation Initiatives

The wwPDB has undertaken numerous remediation projects to address specific categories of errors and inconsistencies within the archive [28]. These remediations provide valuable insight into the types of issues that may be present in structures downloaded from the PDB.

Table 1: Major wwPDB Remediation Projects Impacting MD Simulations

| Remediation Project | Year | Key Improvements | Impact on MD Setup |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metalloprotein Remediation | 2026 (Planned) | Improved metal-containing ligand definitions and polyatomic metal annotations [28]. | Ensures proper metal coordination geometry and charge parameters in simulations. |

| Post-Translational Modification (PTM) Remediation | 2024-2025 | Updated ~76,821 entries with new PTM/PCM annotations [28]. | Correctly parameterizes phosphorylated, glycosylated, or other modified residues. |

| Peptide Residues Chemical Component Dictionary Remediation | 2023 | Standardized atom naming and annotation for peptide residues [28]. | Ensures backbone and terminal atoms are consistently named for force field assignment. |

| Carbohydrate Remediation | 2020 | Standardized atom nomenclature and data representation for glycans [28]. | Enables accurate simulation of protein-carbohydrate complexes and glycan shields. |

| Mutation Annotation Remediation | 2021 | Standardized "engineered mutation" annotation in ~11,000 entries [28]. | Clarifies which residues are engineered, informing simulation system design. |

PDB File Format Fundamentals

The PDB file format uses specific record types to convey structural information. Understanding these records is essential for identifying and correcting issues during structure preparation [29].

- ATOM Records: Define the X, Y, Z orthogonal coordinates (in Ångströms) for atoms in standard residues (amino acids and nucleic acids) [29].

- HETATM Records: Define coordinates for atoms in nonstandard residues, including inhibitors, cofactors, ions, and solvent molecules. The functional difference is that HETATM residues are not connected to other residues by default [29].

- TER Record: Indicates the end of a chain of residues, preventing incorrect connections between separate polymeric chains [29].

- HELIX and SHEET Records: Define the location and type of secondary structure elements, which can be useful for structural analysis [29].

- SSBOND Records: Define disulfide bond linkages between cysteine residues, which are critical for maintaining correct protein folding [29].

Standardized PDB Remediation Workflow

The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach for correcting a raw PDB file to create a simulation-ready structure. This process addresses common issues such as missing atoms, incorrect protonation states, and non-standard residue names.

Ligand Parameterization Methods and Protocols

Ligand parameterization is the process of deriving force field parameters (atom types, partial charges, bond lengths, angles, and dihedrals) for molecules not explicitly defined in standard biomolecular force fields. Accurate parameterization is crucial for obtaining meaningful simulation results for protein-ligand complexes.

Ligand Parameterization Approaches

Several methods exist for generating force field parameters for small molecules, each with varying levels of computational cost and accuracy.

Table 2: Comparison of Ligand Parameterization Methods

| Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Suitable Force Fields |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Force Fields (GAFF) | Applies general atom types and parameters based on chemical environment [30]. | Fast, automated, covers broad chemical space. | Less accurate for specific electronic properties. | AMBER (GAFF, GAFF2) |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Derivation | Derives parameters ab initio from QM calculations [30]. | High accuracy, system-specific parameters. | Computationally expensive, requires expertise. | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS |

| PEOE_PB Method | Uses Partial Equalization of Orbital Electronegativity with Poisson-Boltzmann correction for charges [31]. | Efficient charge calculation, good for drug-like molecules. | Limited validation for diverse molecular sets. | AMBER, CHARMM |

Integrated Ligand Parameterization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for parameterizing a ligand and integrating it with a prepared protein structure to create a complete simulation system. This process ensures compatibility between the protein and ligand force fields.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Correcting PDB Files Using PDB2PQR

PDB2PQR is a widely used tool for automating many aspects of PDB file correction, particularly for preparing structures for electrostatic calculations and MD simulations [31].

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Obtain your protein PDB file. If the structure contains a ligand that you wish to parameterize separately, note its residue name.

- Server Access: Navigate to the PDB2PQR web server.

- Structure Input: Enter the PDB ID or upload your PDB file.

- Force Field Selection: Choose the target force field for your MD simulation (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM).

- Option Selection:

- Select "Ensure that new atoms are not rebuilt too close to existing atoms" (debumping).

- Select "Optimize the hydrogen bonding network".

- Select "Use PROPKA to assign protonation states at pH" and set the desired pH (e.g., 7.0) [31].

- If ignoring a ligand for now, leave the ligand parameterization options unchecked. The server will generate warnings about the unknown residue, which can be addressed later.

- Execution and Output: Submit the job. Upon completion, download the generated PQR file, which contains the corrected atomic coordinates, added hydrogens, and assigned charge and radius parameters.

Notes: The PQR format is similar to PDB but includes atomic charge and radius information essential for subsequent solvation and simulation steps. Always visually inspect the output structure in a molecular viewer like PyMOL or VMD to verify the corrections, paying special attention to the protonation states of key residues like histidines, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid.

Protocol 2: Ligand Parameterization with the AMBER Toolchain

This protocol describes parameterizing a ligand using the antechamber and tleap modules of the AMBER molecular dynamics package [30].

Required Files and Software:

- Ligand structure file (e.g., MOL2, SDF)

- AMBER tools (antechamber, tleap)

- General Amber Force Field 2 (GAFF2)

Procedure:

Ligand Preparation:

- Begin with a 3D structure of your ligand in MOL2 format. Ensure the bond orders and atom types are correct.

- If starting from a 2D structure, use tools like Open Babel to generate a 3D conformation.

Run Antechamber:

This command assigns GAFF2 atom types and calculates partial charges using the AM1-BCC method.

Generate FRCMOD File:

This step checks for missing force field parameters and generates a supplemental parameter file (

GWS.frcmod).Integrate Ligand and Protein in tLEaP:

- Create a

leap.infile with the following commands [30]: - Execute the script:

tleap -f leapin

- Create a

Validation: Always use the check command in tLEaP to inspect the system for close contacts and missing parameters. Visually inspect the final solvated system to ensure the ligand is correctly positioned in the binding site and that solvation is appropriate.

Protocol 3: Ligand Handling with PDB2PQR

For workflows that require direct ligand parameterization within PDB2PQR, follow this protocol [31].

Procedure:

- Prepare Ligand MOL2 File: Generate a MOL2-format file for your ligand with correct bonding and atom types using a tool like PRODRG or molecular editing software.

- Access PDB2PQR Server: Navigate to the PDB2PQR web server.

- Input Structure: Enter the PDB ID or upload your file for the protein-ligand complex.

- Select Parameterization Options:

- Choose your desired force field and naming scheme.

- Under options, select "Assign charges to the ligand specified in a MOL2 file".

- Upload your prepared ligand MOL2 file.

- Also select standard options like debumping and hydrogen bonding network optimization.

- Run and Download: Submit the job. The server will parameterize the ligand using the PEOE_PB.CRC method and integrate it into the final PQR output file [31].

Note: A significant limitation of PDB2PQR is that it processes only a single ligand molecule per structure. For systems with multiple identical ligands, only one will be parameterized [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Structure Preparation and Parameterization

| Tool Name | Function | Application Context | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB2PQR | Adds missing hydrogens, assigns protonation states, and assigns atomic charges/radii [31]. | Preparing proteins for electrostatics calculations and MD simulations. | Web server / Standalone |

| AMBER tLEaP | Integrates components, solvates systems, adds ions, and generates topology/coordinate files [30]. | Final assembly of simulation systems with parameterized ligands. | Standalone software |

| antechamber | Automatically generates force field parameters for small organic molecules [30]. | Ligand parameterization for GAFF/GAFF2 force fields. | Part of AMBER tools |

| PyMOL | Molecular visualization, structure analysis, and script-based automation of corrections [32]. | Visual inspection, mutation, and manual editing of structures. | Commercial / Educational |

| VMD | Visualization, analysis, and packing of molecular systems; supports plugins like PACKMOL-GUI [33] [34]. | System building and trajectory analysis. | Free software |

| PACKMOL | Packing molecules in defined regions to create solvated systems or complex assemblies [34]. | Building initial configurations for MD simulations. | Standalone / VMD plugin |

| PRODRG | Automated topology generation for small molecules, producing MOL2 files for ligands [31]. | Creating initial ligand input files for parameterization servers. | Web server |

Robust initial structure preparation is a non-negotiable prerequisite for generating reliable and scientifically valid molecular dynamics simulations of protein-ligand complexes. By systematically addressing common issues in PDB files through informed correction workflows and applying rigorous ligand parameterization protocols, researchers can establish a solid foundation for their simulation studies. The integrated use of specialized tools like PDB2PQR for protein correction, antechamber for ligand parameterization, and tLEaP for system assembly creates a streamlined pipeline from a raw PDB entry to a fully parameterized simulation system. Adherence to these detailed protocols empowers drug development researchers to minimize structural artifacts and force field inaccuracies, thereby maximizing the predictive power of their computational investigations into molecular recognition and binding events.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes, accurate topology and parameter generation is foundational for obtaining physiologically relevant results. The fundamental distinction lies in whether the ligand forms a covalent bond with the protein target or interacts through non-covalent interactions [35]. This distinction dictates every subsequent step in the simulation setup, from the source of parameters to the simulation protocol itself. Covalent ligands form direct, electron-pair-sharing bonds with amino acid residues like cysteine, serine, or lysine, resulting in strong, often irreversible binding. In contrast, non-covalent ligands rely on a combination of weaker, reversible interactions, including electrostatic forces, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects, to bind their targets [36] [35]. This article details the specific strategies and methodologies required for the accurate parameterization of both ligand classes within the context of a broader thesis on MD simulation setup.

Fundamental Interactions and Implications for Parameterization

Covalent Ligands

Covalent ligands are characterized by their ability to form a covalent bond with the target protein, typically through electrophilic functional groups like acrylamide, epoxyethane, or ethylene sulfonylamide that react with nucleophilic residues (e.g., cysteine, lysine) [35]. This results in a stable, often long-lasting complex. From a topology perspective, this means the ligand must be treated as an integral part of the protein structure. A new residue, representing the covalently modified amino acid (e.g., a cysteinyl-acrylamide adduct), must be defined. The parameters for this new residue—including bond, angle, and dihedral terms—must be derived to be consistent with the chosen force field.

Non-Covalent Ligands

Non-covalent interactions, which are critical for the binding of most traditional drugs, can be classified into several categories [36]:

- Electrostatic Interactions: These include ionic interactions between fully charged species and hydrogen bonding, a strong dipole-dipole interaction where a hydrogen atom is shared between an electronegative donor (like O or N) and an acceptor.

- Van der Waals Forces: This subset includes permanent dipole-dipole interactions (Keesom force), dipole-induced dipole interactions (Debye force), and induced dipole-induced dipole interactions (London dispersion forces).

- π-Effects: These involve interactions with aromatic systems, such as π-π stacking, cation-π, and anion-π interactions.

- Hydrophobic Effect: The tendency of non-polar surfaces to aggregate in an aqueous solution to minimize disruptive interactions with water, thereby increasing entropy.

The binding energy for non-covalent interactions is typically in the range of 1–5 kcal/mol [36]. Accurately capturing these subtle but collectively significant forces requires precise assignment of atomic partial charges and van der Waals parameters for the ligand. The ligand is treated as a separate molecule from the protein in the topology, with interactions governed by the force field's non-bonded potential functions.

Parameter and Topology Generation Strategies

The generation of topologies and parameters is a critical step that ensures the molecular mechanics representation of the system is consistent with the underlying force field philosophy. The approaches for covalent and non-covalent ligands differ significantly.

Table 1: Comparison of Parameter Generation Strategies for Different Ligand Types

| Ligand Type | Key Characteristic | Topology Consideration | Recommended Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent | Forms a covalent bond with a protein residue (e.g., Cys, Lys). | Treated as a new, covalently modified protein residue. | Manual creation based on QM-derived parameters; PolType for tripos mol2 files. |

| Non-Covalent | Binds via reversible, non-covalent interactions. | Treated as a separate molecule within the complex. | Automated servers: CGenFF, LigParGen, ATB, Antechamber/acpype. |

For Non-Covalent Ligands

For non-covalent ligands, automated servers are the preferred tool for generating parameters that are consistent with a specific force field. The general workflow involves preparing a molecular structure file (typically a .mol2 file with correct atom types and bond orders) and submitting it to a server [19]. The following table summarizes common tools aligned with major force fields:

Table 2: Automated Topology Generation Tools for Non-Covalent Ligands

| Force Field | Tool / Server | Description | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM | CGenFF Server | The official server for the CHARMM General Force Field. Requires a Sybyl .mol2 file as input. |

Topology file with parameters and partial charges. |

| OPLS-AA | LigParGen Server | A server from the Jorgensen group to produce OPLS topologies. | GROMACS topology file (.itp). |

| AMBER/GAFF | Antechamber/acpype | Antechamber parametrizes molecules using GAFF; acpype is a Python interface that writes GROMACS topologies. | AMBER-style parameter and coordinate files. |

| GROMOS | ATB (Automated Topology Builder) | A server for topology generation using the GROMOS 54A7 parameter set. | Molecular topology in GROMOS format. |

A critical step in preparing the input for these servers, such as CGenFF, is ensuring the initial molecular file is correct. This often involves:

- Adding Hydrogens: Using a molecule editor like Avogadro to add all hydrogen atoms, as crystal structures typically do not include them [19].

- File Format Correction: Manually editing the resulting

.mol2file to ensure a consistent residue name and number for all atoms in the ligand [19].

For Covalent Ligands

Parameterizing a covalent ligand is more complex because it creates a new chemical entity—the protein-ligand adduct. The standard approach involves:

- Define the Covalent Link: The ligand and the relevant protein residue (e.g., CYS) are combined into a single new residue definition in the topology.

- Derive New Parameters: The new bonds, angles, and diomers formed at the linkage site require specific parameters. These are typically derived from quantum mechanical (QM) calculations to ensure accuracy, as they are not available in standard force field libraries. This process involves optimizing the geometry of the molecular fragment containing the linkage and performing frequency calculations to fit the parameters.

- Charge Reconciliation: The partial charges for atoms involved in the new covalent bond must be adjusted, often by performing a QM calculation on the entire adduct fragment and deriving charges using a method like RESP (for AMBER) or the standard charge assignment procedure for the chosen force field.

Force Field Selection and Benchmarking for Affinity Prediction

The choice of force field is a critical determinant of the accuracy of binding affinity predictions in MD simulations. A recent benchmark study evaluated six different small-molecule force fields for their ability to predict experimental protein-ligand binding affinities using Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations on a set of 598 ligands and 22 protein targets [37].

Table 3: Performance of Open-Source Force Fields in Binding Affinity Prediction [37]

| Force Field | Reported Accuracy | Notes and Context |

|---|---|---|

| OPLS3e | Significantly more accurate | Proprietary force field; highest accuracy in the study. |

| Consensus (Sage, GAFF, CGenFF) | Comparable to OPLS3e | Combining multiple public force fields achieves high accuracy. |

| OpenFF Sage | Comparable to GAFF and CGenFF | Performing comparably based on aggregated statistics. |

| GAFF | Comparable to Sage and CGenFF | General AMBER Force Field. |

| CGenFF | Comparable to Sage and GAFF | CHARMM General Force Field. |

| OpenFF Parsley | Comparable to Sage | Differences observed in outlier behavior. |

The study concluded that while OPLS3e was significantly more accurate, a consensus approach using the public force fields Sage, GAFF, and CGenFF could achieve comparable accuracy [37]. It also highlighted that lower accuracy could not only be attributed to force field parameters but also to factors like input structure preparation and insufficient sampling convergence, especially for large conformational perturbations.

For those seeking near-quantum accuracy, extended tight-binding methods like g-xTB have shown promising results. In a benchmark against the PLA15 dataset, g-xTB achieved a mean absolute percent error of 6.1% in predicting protein-ligand interaction energies, outperforming a range of neural network potentials (NNPs) and other semiempirical methods [38].

Practical Protocol: Ligand Topology Generation with CGenFF

This protocol details the steps for generating a topology for a non-covalent ligand using the CGenFF server, a common task in setting up a simulation [19].

Step 1: Ligand Preparation

- Obtain the initial ligand structure, often from a crystal structure (

jz4.pdb). - Open the

.pdbfile in a molecule editor like Avogadro. - From the "Build" menu, select "Add Hydrogens" to add all hydrogen atoms explicitly.

- Save the structure as a Sybyl Mol2 file (e.g.,

jz4.mol2).

Step 2: File Correction

- Open the

jz4.mol2file in a plain-text editor. - In the

@<TRIPOS>MOLECULEsection, replace the default name with the ligand name (e.g., "JZ4"). - Correct the residue names and numbers in the

@<TRIPOS>ATOMsection so that all atoms belong to the same residue (e.g., all residue name "JZ4" and number "1").

Step 3: Server Submission and Parameter Retrieval

- Access the CGenFF server and log in with a registered account.

- Upload the corrected

.mol2file. - The server will generate a topology file containing the necessary

[ atoms ],[ bonds ],[ angles ], and[ dihedrals ]sections, along with the corresponding parameters and partial charges. The server also provides a penalty score that indicates the quality and reliability of the assigned parameters; low penalties are desirable.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 4: Key Software Tools for Topology Generation and Simulation

| Tool Name | Type / Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| CGenFF Server | Web Server | Generates CHARMM-compatible ligand topologies and parameters. |

| LigParGen | Web Server | Generates OPLS-AA and other force field compatible topologies. |

| ATB (Automated Topology Builder) | Web Server | Generates GROMOS-compatible molecular topologies. |

| Antechamber/acpype | Standalone Program / Script | Parametrizes molecules for AMBER/GAFF and converts topologies to GROMACS format. |

| Avogadro | Desktop Application | Molecule editor used for building, visualizing, and adding hydrogens to ligand structures. |

| GROMACS | Software Suite | A versatile package for performing MD simulations and analysis. |

| OpenMM | Software Suite | A high-performance toolkit for MD simulation, often used as an engine in other pipelines. |

| g-xTB | Standalone Program | A semiempirical quantum chemistry program for accurate interaction energy calculations. |

The reliable setup of MD simulations for protein-ligand complexes hinges on a correct initial classification of the ligand as covalent or non-covalent. This classification dictates the entire parameterization pathway. Non-covalent ligands can be efficiently handled through automated servers, provided input files are carefully prepared. In contrast, covalent ligands demand a more rigorous, manual approach involving the creation of a new residue type and the derivation of quantum mechanics-based parameters for the covalent linkage. The continued development and benchmarking of force fields and parameterization tools are crucial for enhancing the predictive power of molecular simulations in drug discovery and basic research.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes, the accurate representation of the solvent environment is not merely a computational detail but a fundamental determinant of success. Water molecules and ions are direct participants in biological processes, influencing protein structure, mediating binding events, and modulating conformational dynamics. The choice of water model and the proper implementation of ion concentration can significantly impact the outcome of simulations, from the stability of the simulated system to the quantitative prediction of binding affinities. This application note provides a structured guide and set of protocols for making informed decisions in solvation and neutralization, framed within the context of setting up reliable MD simulations for protein-ligand research.

A Comparative Analysis of Explicit Water Models

Explicit water models, which represent individual water molecules, are the gold standard for MD simulations due to their ability to capture specific solvent-solute interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and the presence of interfacial water molecules that can be crucial for defining ligand binding poses [39].

Properties and Performance of Common Water Models

The table below summarizes key properties and recommended use cases for several widely used explicit water models.

Table 1: Comparison of Explicit Water Models for Biomolecular Simulations

| Water Model | Number of Sites | Key Characteristics | Performance Notes | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIP3P [40] | 3 | Standard, computationally efficient model; CHARMM-compatible parameters: O charge = -0.834 e, H charge = 0.417 e, OH bond = 0.9572 Å, HOH angle = 104.52° [40]. | Most common in historical GAG studies; overestimates self-diffusion; poor reproduction of temperature-dependent properties [41]. | General-purpose simulations where computational speed is prioritized; compatibility with CHARMM force field. |

| SPC/E [42] | 3 | An "extended" Simple Point Charge model; polarizable. | Superior to SPC; better for ion distribution studies in confined environments [42]. | Studies of ion permeability and distribution in nanopores or channels. |

| OPC [39] | 4 | Optimal Point Charge model; geometry unconstrained by traditional assumptions. | Excellent agreement with experiment for local and global structural features of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs); predicts intrinsic charge hydration asymmetry accurately [39] [41]. | High-accuracy simulations requiring superior electrostatic properties; modeling of highly charged systems like protein-GAG complexes. |

| OPC3 [41] | 3 | 3-point variant of OPC; optimized electrostatic multipole moments. | Significantly more accurate than TIP3P/SPC/E for bulk properties and charge hydration asymmetry; approaches accuracy limit for 3-point models [41]. | When seeking a balance between the computational efficiency of 3-point models and high accuracy. |

| TIP4P-Ew [43] | 4 | Re-parameterized TIP4P for use with Ewald summation methods. | Used in advanced binding free energy calculations and charge optimization studies [43]. | Free energy calculations (FEP, ABFE) and explicit solvent charge optimization. |

| TIP5P [39] | 5 | 5-site model with an additional lone-pair site. | Among the best performance for studying GAG properties in MD simulations [39]. | Systems where an accurate description of water's electronic structure is critical. |

Impact of Water Model Choice on Biological Outcomes

The selection of a water model can directly influence the interpretation of biological mechanisms. For instance:

- Protein-GAG Complexes: A systematic study found that the choice of water model (TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P, TIP4PEw, OPC, TIP5P) significantly affected the descriptors used to study binding in protein-GAG complexes. Notably, the OPC and TIP5P models provided the best agreement with experimental data for these highly charged, periodic systems [39].

- Enzyme Tunnels: Simulations of haloalkane dehalogenase LinB revealed that while the overall tunnel topology was similar between TIP3P and OPC, the geometrical characteristics of auxiliary tunnels and the stability of their open states were sensitive to the water model. OPC was deemed preferable for accurate transport kinetics [44].

- Ligand Binding Affinity: Inaccuracies in common water models can lead to substantial errors (exceeding 10 kcal/mol) in protein-ligand binding energy estimates, which is unacceptable for quantitative drug design [41].

Protocol: System Solvation with a Chosen Water Model

The following protocol outlines the steps for solvating a prepared protein-ligand complex, using AMBER tools as a common example.

- Prerequisite: Ensure your protein-ligand complex has been pre-processed (hydrogen atoms added, protonation states assigned, missing residues filled) and energy-minimized.

- Create a Solvation Box: Use the

tleapprogram (or equivalent in other MD packages) to immerse the complex in a box of water molecules.- Example

tleapcommand for TIP3P: This command creates a rectangular box of TIP3P water extending 15.0 Å from the surface of the solute in all directions. ThesolvateBoxcommand is used for a predefined box shape, whilesolvateOctcan be used to create an octahedral box, which can be more efficient for spherical systems.

- Example

- Verify Solvation: Visually inspect the resulting system using molecular visualization software (e.g., VMD, PyMOL) to ensure the entire complex is adequately solvated and there are no artificial voids in the solvent box.

Ion Concentration: Neutralization and Physiological Conditions

Beyond pure water, biological systems contain ions. In MD, ions are added for two primary reasons: to neutralize a charged simulation cell and to mimic a physiological ion concentration.

The Role of Ion Concentration in Simulations

- Neutralization: A system with a net charge (e.g., a protein with a net charge of +8) will experience unphysical electrostatic forces in periodic boundary conditions. Adding counterions (e.g., 8 Cl⁻ ions) neutralizes the system, which is essential for energy minimization and stable dynamics.