A Comprehensive 2025 Guide: Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Protein-Ligand Complexes from Setup to Validation

This article provides a current and comprehensive methodology for conducting molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

A Comprehensive 2025 Guide: Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Protein-Ligand Complexes from Setup to Validation

Abstract

This article provides a current and comprehensive methodology for conducting molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of MD, including force fields and system preparation. The guide then details advanced application techniques, from running simulations to analyzing trajectories for binding affinity and kinetics. It addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as handling system instability and improving computational efficiency. Finally, it explores critical validation strategies and compares MD approaches with emerging AI-based co-folding tools like AlphaFold 3, offering a balanced perspective on integrating physics-based simulations with machine learning for robust drug discovery.

Understanding the Core Principles and System Setup of Protein-Ligand MD Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is an indispensable computational technique for exploring the physical motions of atoms and molecules over time. For protein-ligand complexes, MD provides atomic-level insights into dynamic behavior, binding interactions, and conformational changes that are difficult to capture through experimental methods alone. By applying Newton's equations of motion to biological systems, researchers can simulate molecular processes at femtosecond resolution, revealing mechanistic details critical for understanding biological function and guiding drug discovery efforts. This protocol outlines established methodologies for simulating protein-ligand complexes, enabling researchers to capture the dynamic nature of biomolecular recognition and binding.

The characterization of protein-ligand binding is fundamental to pharmaceutical development, as the binding affinity and kinetics directly influence drug efficacy. Molecular dynamics simulations address this need by providing a dynamic view of the binding process, complementing static structures obtained from crystallography. Modern enhanced sampling methods have overcome traditional limitations in simulating rare events like ligand dissociation, making it feasible to calculate binding free energies and elucidate dissociation pathways within reasonable computational timeframes [1]. This article details protocols for running MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes, from basic setup to advanced binding free energy calculations.

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Enhanced Sampling for Binding Free Energy Calculation

Accurate determination of standard binding free energies remains challenging due to the large changes in configurational enthalpy and entropy during ligand association. The dPaCS-MD/MSM (dissociation Parallel Cascade Selection Molecular Dynamics/Markov State Model) protocol addresses this by combining enhanced sampling with trajectory analysis to generate dissociation pathways and calculate binding free energies [1]. This method efficiently samples the unbinding process without applying bias forces, making it suitable for diverse protein-ligand systems.

dPaCS-MD/MSM Protocol Workflow:

- System Preparation: Obtain the initial protein-ligand structure from crystallography or docking. Set up the system in a solvated simulation box with appropriate ions.

- dPaCS-MD Simulation: Run cycles of multiple parallel short MD simulations (typically ~0.1 ns). After each cycle, select snapshots with longer protein-ligand distances as starting points for the next cycle. Repeat until sufficient dissociation sampling is achieved.

- Trajectory Analysis with MSM: Discretize the generated trajectories into conformational states. Construct a Markov state model to identify metastable states and transition probabilities between them.

- Free Energy Calculation: Calculate the free energy profile along the dissociation coordinate from the MSM. Determine the standard binding free energy (ΔG°) using the relationship: ΔG° = -ΔG + ΔGv, where -ΔG is the free energy difference between bound and unbound states, and ΔGv is a correction term for the standard state volume [1].

This protocol has demonstrated strong agreement with experimental binding free energies for several benchmark systems, including trypsin/benzamidine, FKBP/FK506, and the adenosine A2A receptor/T4E complex [1].

Standard MD Simulation of a Protein-Ligand Complex

For researchers requiring equilibrium simulations or system equilibration prior to free energy calculations, a standard MD protocol provides a foundational approach. The following workflow, utilizing tools like OpenFE and OpenMM, outlines the key steps [2]:

Standard MD Protocol Workflow:

- System Setup: Define the

ChemicalSystemcontaining theProteinComponent,SmallMoleculeComponent, andSolventComponent. - Parameterization: Assign force field parameters to all components. For the protein, commonly used force fields include AMBER ff14SB. For small molecules, GAFF with AM1-BCC partial charges is often employed. Solvent is typically represented by models like TIP3P [2].

- Solvation and Ionization: Place the solutes in a solvent box (e.g., cubic or dodecahedral) with a specified padding distance (e.g., 1.0 nm). Add ions to neutralize the system and achieve a physiological concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) [2].

- Energy Minimization: Run an energy minimization to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts, typically for 5,000 steps or until convergence [2].

- System Equilibration:

- NVT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system in the canonical ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) for a short time (e.g., 10 ps) to stabilize the temperature [2].

- NPT Equilibration: Further equilibrate in the isothermal-isobaric ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) for a short time (e.g., 10 ps) to stabilize the density [2].

- Production MD: Run the final, unrestrained simulation in the NPT ensemble to collect data for analysis. The length of this simulation depends on the scientific question, ranging from nanoseconds to microseconds [2].

Web-Based Platform for MD Simulations

For users seeking a more streamlined approach without local software installation, web platforms like PlayMolecule offer integrated pipelines [3]. These platforms interconnect specialized applications to guide users through the preparation and simulation process directly from a browser.

PlayMolecule Workflow:

- Protein Preparation: Use the

ProteinPrepareapplication to protonate and optimize the protein structure from a PDB file. - Ligand Parameterization: Use the

Parameterizeapplication to generate AMBER-compatible parameters for the ligand, including partial charges (e.g., via AM1-BCC) and dihedral fittings using methods like ANI-1x neural network potential [3]. - System Building: Use the

SystemBuilderapplication to solvate the protein-ligand complex, add ions for neutralization, and generate force field parameters for the entire system [3]. - Simulation Execution: Use the

SimpleRunapplication to perform a multi-stage simulation: energy minimization, equilibration with constraints, and a production run [3].

Experimental Setup and Data Presentation

Quantitative Analysis of Binding Free Energies

The dPaCS-MD/MSM method has been quantitatively validated against experimental data for multiple protein-ligand systems. The following table summarizes the binding free energy results, demonstrating the method's accuracy across different protein and ligand sizes [1].

Table 1: Standard Binding Free Energies (ΔG°) Calculated by dPaCS-MD/MSM for Various Protein-Ligand Complexes [1]

| Complex | -ΔG (kcal/mol) | ΔGv (kcal/mol) | Calculated ΔG° (kcal/mol) | Experimental ΔG° (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin/Benzamidine | -6.6 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | -6.1 ± 0.1 | -6.4 to -7.3 |

| FKBP/FK506 | -14.2 ± 1.5 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | -13.6 ± 1.6 | -12.9 |

| Adenosine A2A Receptor/T4E | -15.5 ± 1.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | -14.3 ± 1.2 | -13.2 |

Simulation System Configurations

Different protein-ligand complexes require specific simulation system setups. The table below details the configurations used in the dPaCS-MD study for the three benchmark systems [1].

Table 2: Simulation System Details for Benchmark Protein-Ligand Complexes [1]

| Complex (PDB ID) | Force Field | Water Model | Solvation Box | Ions | Approximate System Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin/Benzamidine (3ATL) | CHARMM36 | SPC/E | Cubic (111 Ã… edge) | 150 mM KCl | ~140,000 atoms |

| FKBP/FK506 (1FKF) | AMBER ff14SB | SPC/E | Cubic (117 Ã… edge) | 150 mM NaCl | ~120,000 atoms |

| Adenosine A2A Receptor/T4E (3UZC) | AMBER ff14SB | SPC/E | Rectangular (82×82×138 ų) w/ DMPC membrane | Not Specified | Not Specified |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful execution of molecular dynamics simulations relies on a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources. The following table catalogues key solutions used in the protocols discussed herein.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool/Solution | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [4] | MD Engine | High-performance software for simulating Newtonian equations of motion. | Used for MD simulations, including membrane protein systems like A2A receptor [1]. |

| OpenMM [2] | MD Engine | Toolkit for molecular simulation with hardware acceleration. | Used in the OpenFE plain MD protocol for running simulations [2]. |

| AMBER [1] | MD Suite | Suite of programs for simulating biomolecular systems. | Used for simulations of soluble protein-ligand complexes (e.g., with PMEMD module) [1]. |

| CHARMM36 [4] | Force Field | Set of parameters for potential energy calculations. | Used for defining energy terms for atoms in the system [4]. |

| AMBER ff14SB [1] | Force Field | Protein force field within the AMBER family. | Used for simulating proteins in several benchmark studies [1]. |

| GAFF (General Amber Force Field) [1] | Force Field | Force field for small organic molecules. | Used for generating parameters for ligands [1]. |

| BFEE2 [5] | Software Package | Application for automated absolute binding free energy calculation. | Guides user through setup and simulation for binding free energy protocols [5]. |

| PlayMolecule [3] | Web Platform | Integrated suite of web applications for simulation preparation and execution. | Provides ProteinPrepare, Parameterize, SystemBuilder, and SimpleRun for a streamlined workflow [3]. |

| HTMD [3] | Python Framework | Environment for handling molecular systems and simulation setup. | Underpins the SystemBuilder application on the PlayMolecule platform [3]. |

| Doryx | Doryx (Doxycycline Hyclate) | Doryx (doxycycline hyclate) is a tetracycline-class antibiotic for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Edtah | Edtah, CAS:38932-78-4, MF:C10H20N6O8, MW:352.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

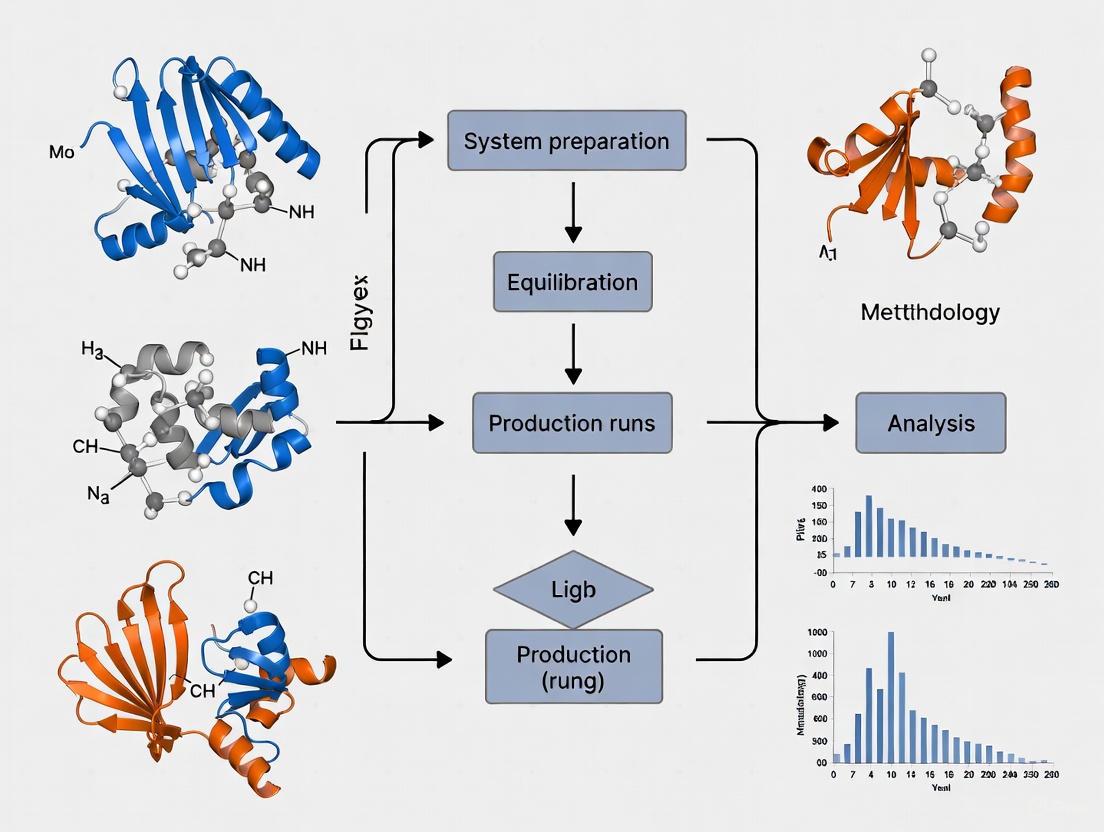

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of a standard molecular dynamics simulation protocol for a protein-ligand complex, integrating steps from the methodologies described above.

Standard MD Simulation Workflow

For advanced studies focusing on binding free energies, the dPaCS-MD/MSM method provides a specialized workflow, depicted below.

Enhanced Sampling for Binding Free Energy

Key Force Fields for Protein-Ligand Interactions (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM)

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in structural biology and computer-aided drug design, providing atomic-level insight into protein-ligand interactions that is difficult to obtain through experimental methods alone. The accuracy of these simulations critically depends on the empirical force fields used to represent the potential energy surface of the molecular system. Force fields are mathematical representations of the potential energy of a system of particles, comprising parameters for bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals, electrostatics). For protein-ligand interactions, the choice of force field significantly impacts the reliability of binding mode predictions, binding affinity estimates, and conformational sampling. The most widely used force families for biomolecular simulations are AMBER (Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement) and CHARMM (Chemistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics), which have been continuously refined over decades to improve their accuracy for proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, carbohydrates, and small molecules. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of these key force fields, their performance characteristics, and detailed protocols for their application in studying protein-ligand interactions.

AMBER Force Field Family

The AMBER force field family includes several specialized parameter sets for biomolecules. The protein force fields, particularly AMBER ff14SB and ff19SB, are optimized for simulating proteins and are often combined with the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF and GAFF2) for small molecules. GAFF2 is specifically designed to provide atom types and parameters needed to parameterize most pharmaceutical molecules and maintains compatibility with traditional AMBER force fields for proteins [6]. For charge assignment, the AM1-BCC method provides an inexpensive and fast approach for calculating partial charges, which is particularly useful for high-throughput applications [6] [7].

The AMBER force field functional form includes terms for bonds, angles, dihedrals, and non-bonded interactions similar to CHARMM, though it does not include explicit Urey-Bradley terms for angle compensation [8]. In benchmark studies, AMBER ff14SB has demonstrated excellent performance in representing protein side chain ensembles, showing particularly high accuracy for buried residues compared to surface-exposed ones [9].

CHARMM Force Field Family

The CHARMM force fields encompass multiple generations of parameter sets for different biomolecular classes. CHARMM36 is the current standard for proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, while CHARMM36m represents an improved version for proteins that better captures intrinsically disordered regions [10] [11]. For drug-like molecules, the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) provides broad coverage of chemical groups present in biomolecules and pharmaceuticals [8] [10].

The CHARMM potential energy function includes distinctive terms not present in all force fields:

[ \begin{aligned} V = &\sum{bonds}k{b}(b-b{0})^{2} + \sum{angles}k{\theta}(\theta-\theta{0})^{2} + \sum{dihedrals}k{\phi}[1+\cos(n\phi-\delta)] \ &+ \sum{impropers}k{\omega}(\omega-\omega{0})^{2} + \sum{Urey-Bradley}k{u}(u-u{0})^{2} \ &+ \sum{nonbonded}\left(\epsilon{ij}\left[\left(\frac{R{min{ij}}}{r{ij}}\right)^{12}-2\left(\frac{R{min{ij}}}{r{ij}}\right)^{6}\right]+\frac{q{i}q{j}}{\epsilon{r}r{ij}}\right) \end{aligned} ]

The Urey-Bradley term specifically contributes to angle vibrations, while the improper term accounts for out-of-plane bending [8]. CHARMM also includes developing polarizable force fields using both the fluctuating charge (CHEQ) and Drude shell models to more accurately represent electronic polarization effects [10].

Comparative Performance in Protein-Ligand Studies

Recent benchmarking studies provide quantitative comparisons of force field performance for protein-ligand interactions. In side chain conformation studies, AMBER and CHARMM force fields clearly outperform OPLS and GROMOS in estimating rotamer populations, with AMBER14SB, AMBER99SB*-ILDN, and CHARMM36 identified as the best performers [9].

For binding free energy calculations, comprehensive assessments have evaluated various parameter combinations. The table below summarizes performance metrics for different force field and water model combinations in Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) calculations on eight benchmark test cases (BACE, CDK2, JNK1, MCL1, P38, PTP1B, Thrombin, TYK2) [7]:

Table 1: Force Field Performance in Binding Free Energy Prediction

| Force Field | Water Model | Charge Model | Mean Unsigned Error (kcal/mol) | RMSE (kcal/mol) | R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER ff14SB | SPC/E | AM1-BCC | 0.89 | 1.15 | 0.53 |

| AMBER ff14SB | TIP3P | AM1-BCC | 0.82 | 1.06 | 0.57 |

| AMBER ff14SB | TIP4P-EW | AM1-BCC | 0.85 | 1.11 | 0.56 |

| AMBER ff15ipq | SPC/E | AM1-BCC | 0.85 | 1.07 | 0.58 |

| AMBER ff14SB | TIP3P | RESP | 1.03 | 1.32 | 0.45 |

| AMBER ff15ipq | TIP4P-EW | AM1-BCC | 0.95 | 1.23 | 0.49 |

| OPLS2.1 (FEP+) | - | - | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.66 |

| AMBER (TI) | - | - | 1.01 | 1.30 | 0.44 |

These results demonstrate that the combination of AMBER ff14SB with TIP3P water and AM1-BCC charges provides the best balance of accuracy among the open-source options tested, with performance approaching that of commercial implementations like OPLS2.1 used in Schrödinger's FEP+ [7].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Ligand Parameterization Protocol for AMBER/GAFF2

Accurate parameterization of small molecule ligands is essential for reliable MD simulations. The following protocol uses AmberTools programs to generate parameters for non-conventional residues [6]:

Input Preparation: Prepare a 3D structure of the ligand in PDB or MOL2 format with correct protonation states and stereochemistry.

Atom Typing and Charge Calculation:

This command assigns GAFF2 atom types and calculates AM1-BCC partial charges for the neutral molecule[-] [6]. The

-ncoption specifies the net molecular charge, which should be adjusted according to the ligand's protonation state.Parameter Checking:

This step identifies missing force field parameters and provides reasonable approximations by analogy to similar parameters [6]. The resulting

frcmodfile should be carefully inspected, particularly for any parameters marked with "ATTN: needs revision" which require manual parameterization.File Integration in tLEaP:

These commands load the generated parameters into the AMBER simulation environment [12].

System Assembly and Simulation Setup

The workflow below illustrates the complete process for building and simulating a protein-ligand complex:

Diagram 1: MD Setup Workflow (65 characters)

For CHARMM simulations, the CHARMM-GUI platform provides a robust alternative for system building, offering automated parameter assignment through its Ligand Reader & Modeler module [10]. This web-based interface can generate input files for multiple simulation packages including CHARMM, NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, and OpenMM.

Virtual Screening Enhancement Protocol

Molecular docking followed by MD refinement has emerged as a powerful approach for improving virtual screening results. The following protocol demonstrates this integrated methodology [11]:

Initial Docking: Perform molecular docking with AutoDock Vina or similar software to generate initial protein-ligand poses.

High-Throughput MD Setup:

- Convert docked poses to MD-ready systems using automated tools like CHARMM-GUI's Input Generator.

- Employ a python script to automate browser actions for batch system preparation.

Short MD Simulations:

- Solvate systems in a cubic TIP3P water box with 10 Ã… padding.

- Neutralize with appropriate ions (K+, Cl-).

- Use the CHARMM36m force field for proteins and CGenFF for ligands.

- Minimize (5,000 steps), equilibrate (1 ns NVT), and run production simulations (10-50 ns).

Trajectory Analysis:

- Calculate ligand RMSD relative to the initial docked pose after aligning the protein.

- Identify stable binding modes based on RMSD convergence.

- Use binding stability to discriminate active from decoy compounds, significantly improving enrichment over docking alone [11].

This approach has demonstrated a 22% improvement in ROC AUC (from 0.68 to 0.83) compared to docking alone across 56 protein targets from the DUD-E dataset [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Protein-Ligand MD Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| AmberTools | Software Suite | Ligand parameterization with antechamber/parmchk2, system building with tLEaP | AMBER force fields |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web Portal | Automated system building for membrane and soluble proteins | CHARMM, AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD |

| CGenFF | Force Field | Parameterization of drug-like molecules | CHARMM force fields |

| GAFF/GAFF2 | Force Field | Parameterization of pharmaceutical molecules | AMBER force fields |

| OpenMM | MD Engine | High-performance GPU-accelerated simulations | Multiple force fields |

| CHARMM | MD Engine | Comprehensive biomolecular simulation package | CHARMM force fields |

Advanced Applications and Methodological Developments

Free Energy Perturbation for Binding Affinity Prediction

Free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations have become increasingly reliable for predicting relative binding affinities of congeneric ligands. The automated FEP workflow implemented in tools like Alchaware using OpenMM provides open-source access to this methodology [7]. Key considerations for FEP setup include:

- Force Field Selection: AMBER ff14SB with GAFF2 and TIP3P water provides a well-validated combination.

- Charge Model: AM1-BCC charges generally outperform RESP for relative binding free energy calculations [7].

- Enhanced Sampling: Hamiltonian replica exchange with solute tempering (REST) improves convergence by enhancing conformational sampling [7].

Validation on eight benchmark targets demonstrated mean unsigned errors of 0.82-0.89 kcal/mol for binding affinity prediction, approaching chemical accuracy [7].

Specialized Force Fields for Membrane Proteins

Simulating membrane protein-ligand interactions requires additional considerations for the lipid environment. The AMBER LIPID21 force field provides parameters for various lipid types that are compatible with the protein ff14SB and GAFF2 small molecule force fields [13]. For complex membrane systems containing glycolipids or glycoproteins, the GLYCAM_06j force field can be combined with AMBER parameters for comprehensive coverage [13].

Emerging Methodologies

Recent developments in force fields include the creation of residue-specific parameters for intrinsically disordered proteins (CHARMM36IDPSFF) which improve agreement with experimental NMR chemical shifts [10]. The continued refinement of polarizable force fields, particularly the CHARMM Drude model, promises more accurate representation of electronic effects in heterogeneous binding environments [10].

Integration of MD with experimental structural biology approaches has also shown promise, as demonstrated in studies where enrichment of chemical libraries docked to protein conformational ensembles from MD simulations led to successful identification of novel aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 inhibitors with IC50 values below 5 μM [14].

The accuracy of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the initial structural models. Preparing and refining protein-ligand complexes represents a critical first step in any MD pipeline, as errors introduced at this stage propagate through subsequent analysis, compromising biological interpretations and drug discovery applications. Current research emphasizes that widely-used datasets often contain structural artifacts in both proteins and ligands, which undermine the accuracy and generalizability of resulting scoring functions and dynamic profiles [15]. This application note details standardized protocols for structure preparation, highlighting integrated computational workflows that transform raw coordinate data into simulation-ready systems, while providing metrics for quality assessment throughout the process.

Key Challenges in Initial Structure Preparation

Common Structural Artifacts and Data Issues

Protein-ligand complexes derived from experimental sources, particularly crystallography, frequently contain imperfections that necessitate correction before MD simulation. Analysis of popular datasets like PDBbind reveals several recurring issues that require systematic addressing [15]:

Table 1: Common Structural Artifacts in Protein-Ligand Complexes

| Category | Specific Issues | Impact on Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Issues | Incorrect bond orders, unrealistic protonation states, missing hydrogen atoms, improper aromaticity | Compromised electrostatic interactions, inaccurate binding energy calculations, distorted binding poses |

| Protein Issues | Missing heavy atoms in residues, unresolved loops, incorrect side chain rotamers, missing disulfide bridges | Altered protein flexibility, non-physical conformational sampling, distorted binding pocket geometry |

| Complex Issues | Severe steric clashes between protein and ligand, covalently bonded ligands misclassified as non-covalent, unrealistic binding orientations | Simulation instability, need for excessive equilibration, fundamentally incorrect binding mechanism |

| Data Organization | Sub-optimal organization of protein-ligand classes, inconsistent curation protocols | Limited training and validation capabilities for scoring functions |

The presence of these artifacts underscores why a robust preparation workflow is indispensable. As one study notes, "a significant portion of the PDBbind dataset contains structural errors, statistical anomalies, and a sub-optimal organization of protein-ligand classes that can limit SF training and validation" [15].

Workflow for Structural Preparation and Refinement

A semi-automated workflow approach ensures reproducibility while minimizing manual intervention. The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive pipeline for converting raw structural data into simulation-ready systems:

Standardized Protocols for Structure Preparation

Integrated Protein-Ligand Preparation Workflow

Objective: Transform raw PDB structures into simulation-ready systems with corrected chemistry and complete atom representation.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Input Data: Protein-ligand complex structure in PDB format

- Structure Preparation Tools: Chimera, Schrodinger Maestro, MOE, or similar

- Ligand Parameterization: LigParGen server, CGenFF, ACPYPE, AnteChamber

- Force Fields: OPLS-AA, CHARMM, AMBER, or GROMOS families

- MD Engines: GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, or CHARMM

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Structure Cleaning and Validation

- Download PDB structure and separate protein, ligand, and additive components (ions, cofactors, solvents)

- Remove alternative conformations, retaining only the highest occupancy atoms

- Validate ligand geometry against chemical component dictionary

- Check for structural completeness using visual inspection and validation servers

Protein Structure Preparation

- Add missing heavy atoms using loop modeling approaches (e.g., Dunbrack rotamer library)

- Correct histidine protonation states based on local environment and predicted pKa values

- Add disulfide bonds where appropriate based on cysteine proximity

- Optimize side-chain rotamers for residues outside binding pocket

Ligand Structure Preparation

- Correct bond orders and aromaticity using chemical knowledge

- Determine appropriate protonation states at physiological pH (considering local environment)

- Perform geometry optimization with quantum mechanical methods or molecular mechanics

- Generate topology files with appropriate charge models (e.g., 1.14*CM1A for neutral ligands)

Complex Reassembly and Validation

- Recombine corrected protein and ligand structures

- Add missing hydrogen atoms to entire system

- Perform constrained energy minimization to relieve steric clashes

- Validate final structure against experimental electron density where available

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For ligands with unusual chemistry, consider manual parameterization using quantum mechanical approaches

- If severe clashes persist after minimization, consider alternative ligand binding poses

- For membrane proteins, include membrane environment during preparation stages

Practical Application: GROMACS Protein-Ligand System Setup

Case Study: T4 Lysozyme L99A with Benzene (PDB ID: 4W52)

This protocol provides a specific implementation for GROMACS simulations [16]:

Structure Preparation

This produces

protein_clean.pdbandligand_wH.pdbLigand Parameterization

- Upload

ligand_wH.pdbto LigParGen server with residue number set to 1 - Select appropriate charge model (1.14*CM1A for neutral ligands)

- Download GROMACS files:

BNZ.gro(coordinates) andBNZ.itp(topology)

- Upload

System Assembly

Topology Integration

- Add

#include "BNZ.itp"totopol.topafter forcefield inclusion - Add

BNZ 1to[molecules]section

- Add

The resulting system is then ready for solvation, ionization, and energy minimization according to standard MD protocols [16].

Quality Assessment and Validation Metrics

Validation Framework for Prepared Structures

Quality validation should employ multiple complementary metrics to assess different aspects of structural integrity. The Metrics Reloaded framework provides a paradigm for multi-dimensional assessment, recommending against reliance on single metrics [17].

Table 2: Quality Metrics for Prepared Protein-Ligand Structures

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Optimal Range | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steric Quality | Clash score, Ramachandran outliers, Rotamer outliers | Clash score < 10, Ramachandran favored > 95% | MolProbity, WHAT_CHECK |

| Geometry Quality | Bond length deviations, Bond angle deviations, RMSZ scores | RMSZ < 1.0 for bonds and angles | REFMAC, Phenix validation |

| Ligand Chemistry | Planarity violations, Chirality errors, Bond length outliers | No violations | Privateer, Grade Web Server |

| Electronic Properties | Partial charge rationality, Dipole moment consistency | Comparable to QM calculations | Quantum mechanical calculations |

| Complex Compatibility | Complementarity statistics, Interface voids | Sc > 0.60, minimal voids | SC, PISA, 3D-surfer |

The importance of multi-metric validation is emphasized by recent research: "By definition, each metric comes with specific, task-dependent pitfalls. An overlap-based metric... is not able to capture the object shape properly. On the other hand, a boundary-based metric... may miss holes inside an object. Both metrics combined would complement each other" [17].

Advanced Refinement Techniques

For challenging cases where standard preparation yields unsatisfactory results, advanced refinement techniques can be employed:

Ensemble Refinement: This method accounts for ligand flexibility in crystal structures by generating multiple conformations, providing insights beyond standard refinement. Research shows that "ensemble refinement sometimes indicates that the flexibility of parts of the ligand and some protein side chains is larger than that which can be described by a single conformation" [18].

Molecular Dynamics with Enhanced Sampling: Short simulations with accelerated sampling (e.g., Gaussian accelerated MD, metadynamics) can explore alternative binding modes and identify the most stable conformation before production runs.

QM/MM Refinement: For critical ligand interactions, quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical optimization of the binding site provides superior electronic structure description compared to force field methods alone.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Protein-Ligand Structure Preparation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigParGen | Web Server | OPLS-AA parameter generation for organic ligands | https://ligpargen.scs.illinois.edu |

| HiQBind-WF | Workflow | Data cleaning and structural preparation pipeline | Open-source [15] |

| Chimera | Desktop Software | Structure visualization, analysis, and initial preparation | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera |

| PDB2GMX | GROMACS Tool | Protein topology generation with hydrogens | Part of GROMACS suite |

| BioLiP | Database | Protein-ligand interactions with functional annotations | https://bindingdb.org/bind/BioLiP3 |

| MolProbity | Web Service | All-atom structure validation | http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu |

| Grade | Web Server | Ligand geometry evaluation and idealization | https://grade.globalphasing.org |

Proper preparation of initial protein-ligand structures remains a non-negotiable prerequisite for reliable molecular dynamics simulations. By implementing the standardized protocols and validation metrics outlined in this application note, researchers can significantly enhance the accuracy and interpretability of their simulation results. The integration of automated workflows like HiQBind-WF with careful manual inspection represents the current state-of-the-art approach, balancing efficiency with rigorous quality control. As MD simulations continue to play an increasingly central role in drug discovery and structural biology, robust preparation methodologies will only grow in importance for generating biologically meaningful insights.

The accuracy of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes is critically dependent on the faithful representation of the simulation environment. Solvation, ion concentration, and system neutralization are not merely procedural steps but foundational aspects that govern the electrostatic and steric interactions central to biomolecular function and ligand binding [19]. An improperly solvated system or an imbalanced ionic atmosphere can lead to simulation artifacts, unreliable trajectories, and ultimately, incorrect biological inferences. The environment must be modeled to mimic the physiological conditions relevant to the system under study, whether for fundamental research or computer-aided drug discovery. This document outlines the core concepts, quantitative parameters, and detailed protocols for defining a physiologically realistic simulation environment, framed within the broader methodology for MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes.

Core Concepts and Solvation Models

The first and most significant choice in defining the environment is how to represent the solvent, which is typically water in biological systems. Solvation models fall into two primary categories: explicit and implicit, each with distinct advantages and computational trade-offs [20].

Explicit Solvent Models

Explicit solvent models treat solvent molecules as individual, discrete entities with defined coordinates and degrees of freedom. This approach provides a physically intuitive and spatially resolved picture of the solvent, allowing for the specific study of water structure, hydrogen-bonding networks, and solvent-mediated interactions.

- Physical Realism: Explicit models can capture specific solute-solvent interactions, such as water bridges between a protein and a ligand, which can be critical for accurate binding affinity predictions [21].

- Common Water Models: The TIP3P water model is a standard choice in many MD suites and is often a component of broader force fields like AMBER [2]. Other models, such as SPC (Simple Point Charge), are also widely used [20].

- Computational Cost: The primary disadvantage is computational expense, as the solvent molecules can constitute over 80% of the particles in a system, drastically increasing the computational resources required for the simulation.

Implicit Solvent Models

Implicit solvent models, also known as continuum models, replace explicit solvent molecules with a homogeneously polarizable medium characterized primarily by its dielectric constant (ε) [20]. The solute is embedded in a cavity within this continuum, and the model calculates the free energy of solvation based on the solute's charge distribution.

The solvation free energy (ΔGsolv) in these models is typically decomposed into several components [20]: ΔGsolv = Gcavity + Gelectrostatic + Gdispersion + Grepulsion

Where:

- Gcavity: Energy required to create a cavity in the solvent for the solute.

- Gelectrostatic: Energy from polarization of the solvent by the solute's charge distribution.

- Gdispersion and Grepulsion: Non-electrostatic contributions from van der Wa forces and exchange repulsion.

Popular implicit models include the Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM), the Solvation Model based on Density (SMD), and the COSMO (COnductor-like Screening MOdel) model [20] [22] [23]. The SMD model, for instance, is a "universal" model applicable to any solute in any solvent for which key descriptors like the dielectric constant and surface tension are known [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Implicit Solvation Models.

| Model | Theoretical Basis | Key Features | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCM [20] | Poisson(-Boltzmann) Equation | Solute in a tiled cavity within a dielectric continuum; highly configurable. | Geometry optimizations, frequency calculations in solution. |

| SMD [23] | IEF-PCM / Universal | Uses full solute electron density; parametrized for a wide range of solvents and solutes. | Hydration free energy predictions, quantum chemical calculations. |

| COSMO [22] | Conductor-like Screening | Fast, robust approximation to dielectric equations; reduces outlying charge errors. | Self-consistent reaction field calculations in quantum chemistry. |

Hybrid and Advanced Models

For specific applications, hybrid approaches are available. QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) methods allow a section of the system (e.g., a ligand in a binding site) to be treated with quantum mechanical accuracy, while the rest of the protein and solvent is handled with a classical MM force field [20] [19]. Furthermore, a new generation of polarizable force fields, such as the AMOEBA (Atomic Multipole Optimised Energetics for Biomolecular Applications) force field, is being developed to account for changes in molecular charge distribution, providing a more accurate representation of electrostatic interactions in explicit solvent simulations [20].

Ion Concentration and System Neutralization

In a physiological environment, proteins and ligands exist in a solution containing ions. Omitting ions from a simulation can lead to severe electrostatic artifacts, especially when the protein-ligand complex carries a net charge.

Purpose of Ions in MD Simulations

- Charge Neutralization: The primary role of ions is to neutralize the net charge of the system. Most MD simulation codes, including GROMACS, require the total system charge to be zero to avoid infinite electrostatic self-energies in periodic boundary conditions. This is achieved by adding counter-ions (e.g., Na⺠for a negatively charged system, Cl⻠for a positively charged one) [24].

- Physiological Ionic Strength: Beyond neutralization, ions are added to achieve a specific physiological concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl). This creates an ionic atmosphere that screens electrostatic interactions, mirroring real biological conditions and improving the realism of the simulation [2] [25].

Practical Implementation

The process typically involves two steps:

- Neutralization: Adding the minimal number of counter-ions to bring the total system charge to zero.

- Salting: Adding additional pairs of cations and anions to reach a desired ionic concentration (e.g., 0.15 M for physiological saline) [25].

The ion concentration is usually specified in molar (M) units. The number of ions to add is calculated automatically by the MD software based on the volume of the simulation box and the number of water molecules present [25].

Table 2: Common Ion Types and Parameters in MD Simulations.

| Ion Type | Force Field Parameters | Common Concentration | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na⺠| Included in major force fields (CHARMM36, AMBER) | 0.15 M [2] | Physiological salt concentration (as NaCl) |

| K⺠| Included in major force fields (CHARMM36, AMBER) | 0.15 M [25] | Physiological salt concentration (as KCl); often used as default [25] |

| Clâ» | Included in major force fields (CHARMM36, AMBER) | 0.15 M [2] | Counter-ion for positive systems; physiological salt |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for setting up a simulation environment for a protein-ligand complex, leveraging tools like GROMACS and OpenFE [24] [2].

Comprehensive Setup Workflow

The following diagram outlines the complete workflow for defining the simulation environment, from initial structure preparation to a production-ready system.

Detailed Protocol for System Setup

The following steps provide a command-line-centric protocol using GROMACS, a widely used MD software package [24].

Step 1: Obtain and Prepare Protein and Ligand Coordinates

- Input: A protein structure file in PDB format. If the structure contains a ligand of interest, its coordinates must be present.

- Action: Visually inspect the structure using a molecular viewer (e.g., RasMol). Pre-process the PDB file to remove extraneous water molecules and other non-essential components. For ligands not recognized by the force field, separate topology files must be created manually [24].

- Command (GROMACS): This command generates the molecular topology and coordinate file in GROMACS format, prompting the user to select an appropriate force field.

Step 2: Define the Simulation Box and Apply Periodic Boundary Conditions

- Purpose: To create a finite simulation cell that can be replicated infinitely in space, thus avoiding artificial surface effects.

- Action: Define a box (e.g., cubic, dodecahedron) around the protein with a sufficient margin (e.g., 1.4 nm) from the protein surface to ensure the solute does not interact with its own periodic images [24].

- Command (GROMACS):

Step 3: Solvate the System

- Purpose: To immerse the protein-ligand complex in a solvent environment.

- Action: Fill the simulation box with water molecules. This updates the topology file to include the water molecules.

- Command (GROMACS):

- Alternative (OpenFE): In modern workflows using tools like OpenFE, the

SolventComponentis defined with parameters for the solvent model (e.g.,tip3p) and solvent padding (e.g.,1.0 nm), which automates this step [2].

Step 4: Add Ions for Neutralization and Physiological Concentration

- Purpose: To neutralize the system's net charge and establish a physiologically relevant ionic strength.

- Prerequisite: Generate a pre-processed input file (

*.tpr) using thegromppcommand and a parameter file (*.mdp). - Action: Use the

genioncommand to replace water molecules with ions. - Command (GROMACS):

This example adds 3 chloride ions (CL) to neutralize a system with a net charge of -3. The

-pnameand-nnameflags specify the cation and anion types, respectively [24]. - Alternative (OpenFE): The

SolventComponentcan be initialized with anion_concentrationparameter (e.g.,0.15 * unit.molar) and anions_type(e.g.,KClorNaCl), which handles this process during system setup [2] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table catalogs key software tools and "reagents" essential for setting up a simulation environment for protein-ligand complexes.

Table 3: Essential Software and Parameters for Simulation Environment Setup.

| Item Name | Type / Category | Function in Setup Process | Example Parameters / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [24] | MD Software Suite | Performs all steps: file conversion, solvation, ion addition, minimization, equilibration, and production MD. | Open-source; high performance; supports major force fields. |

| OpenFE/OpenMM [2] | MD Automation & Engine | Python-based toolkit for setting up and running simulation workflows, including complex protein-ligand systems. | Simplifies setup via ChemicalSystem and settings objects; uses OpenMM as a backend. |

| CHARMM36 [25] | Force Field | Provides molecular mechanics parameters for proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and small molecules. | Commonly used with GROMACS; includes TIP3P water model parameters. |

| AMBER ff14SB [2] | Force Field | Provides molecular mechanics parameters for proteins. Often used with TIP3P water. | Default in some OpenFE protocols [2]. |

| TIP3P [2] | Explicit Water Model | A 3-site model for water molecules. Used to solvate the system explicitly. | Standard choice for simulations with AMBER and CHARMM force fields. |

| SMD Model [23] | Implicit Solvent Model | A universal solvation model for calculating solvation free energies in quantum chemical calculations. | Uses solute electron density; parametrized for a wide range of solvents. |

| Na+/K+/Cl- [25] | Ion Parameters | Pre-defined parameters within force fields for adding ions for neutralization and physiological concentration. | ions_type=NaCl or ions_type=KCl; ions_conc=0.15 (for 0.15 M) [25]. |

| Yrgds | Yrgds, MF:C24H36N8O10, MW:596.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Dmbap | Dmbap, MF:C19H28N2O5, MW:364.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The careful definition of the simulation environment is a critical, non-negotiable step in generating reliable and meaningful MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes. The choice between explicit and implicit solvation involves a strategic trade-off between computational cost and the level of physical detail required. The subsequent steps of system neutralization and the establishment of a physiological ion concentration are essential for creating a stable, electrostatically realistic system. By adhering to the detailed protocols and utilizing the tools outlined in this document, researchers can ensure that their simulations are built upon a solid foundation, thereby increasing the credibility of their scientific findings in the broader context of drug development and biomolecular research.

Energy Minimization and Equilibration Protocols for Stable Starting Points

Within the broader methodology for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes, the establishment of a stable and physically realistic starting point is a critical prerequisite for obtaining reliable results. Energy minimization and equilibration protocols serve as the foundational steps that transition a system from its initial, potentially strained coordinates to a stable, equilibrium state representative of the biological conditions under investigation. Without proper minimization and equilibration, simulations can exhibit unrealistic atomic clashes, high-energy conformations, and unstable trajectories that compromise the validity of subsequent production runs and binding free energy calculations [5] [26]. This application note details comprehensive protocols for preparing stable systems, drawing from established methodologies in the field [2] [27] [28].

The necessity of these steps stems from several inherent issues in initial protein-ligand complex structures. These may include steric clashes introduced during docking or homology modeling, deviations from ideal bond geometries, and the abrupt introduction of solvent molecules and counterions into the system [29] [27]. Energy minimization gradually relieves these steric strains and geometric distortions by iteratively adjusting atomic coordinates to find a local minimum on the potential energy surface. Subsequent equilibration then allows the system to adopt appropriate thermodynamic properties—including correct temperature, density, and pressure—through carefully controlled dynamics that prevent the collapse of the protein structure or premature dissociation of the ligand [2] [28].

Theoretical Framework

The Role of Energy Minimization

Energy minimization in molecular dynamics functions as a corrective process that resolves structural imperfections in the initial molecular system. By employing algorithms such as steepest descent, conjugate gradient, or limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (L-BFGS), minimization progressively reduces the total potential energy of the system until a convergence threshold is met [29]. This process is essential for removing unphysical atomic overlaps that would otherwise create enormous forces and numerical instabilities if directly subjected to dynamics.

The mathematical foundation of minimization relies on the calculation of the potential energy function, typically represented by a molecular mechanics force field:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{torsion}} + E{\text{electrostatic}} + E{\text{van der Waals}} ]

where the various terms represent bond stretching, angle bending, torsional rotations, electrostatic interactions, and van der Waals forces, respectively [26]. Minimization algorithms iteratively adjust atomic coordinates to locate minima on this multidimensional energy surface, ensuring the system begins dynamics from a stable configuration.

Equilibration Principles

Equilibration bridges the gap between a statically minimized structure and a system ready for production MD under the desired thermodynamic ensemble. This phase allows for the gradual relaxation of solvent molecules around the solute, proper distribution of kinetic energy among all degrees of freedom, and establishment of correct system density and temperature [2] [28]. A well-designed equilibration protocol typically follows a sequential approach:

- Position-restrained equilibration: Initially, heavy atoms of the protein and ligand are harmonically restrained while allowing solvent and ions to move freely. This enables water and ions to reorganize around the solute without destabilizing the protein-ligand complex.

- Gradual heating: The system temperature is progressively increased from a low value (e.g., 0-100K) to the target temperature (e.g., 300K) while maintaining restraints on solute heavy atoms.

- Pressure equilibration: Once the target temperature is reached, pressure coupling is introduced to achieve the correct system density, typically using a barostat for the NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensemble.

This staged approach prevents the "shocking" of the system with full dynamics immediately after minimization, which could lead to unrealistic structural deformations or ligand dissociation [28].

Computational Toolkit

Successful implementation of minimization and equilibration protocols requires specific computational tools and resources. The selection of software, force fields, and hardware configurations significantly impacts the efficiency and reliability of the preparatory stages.

Table 1: Essential Software Tools for Minimization and Equilibration

| Software | Version | Primary Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | 2023.4 [27] | Molecular dynamics simulation engine | Performing energy minimization, heating, equilibration, and production MD |

| AMBER | 14+ [28] | Molecular dynamics suite | System preparation, parameterization, and initial minimization |

| OpenMM | 7.6+ [2] | High-performance MD toolkit | Customizable MD protocols with GPU acceleration |

| AutoDock Tools | 4.2 [27] | Docking and preparation software | Ligand preparation and parameterization |

| PyMOL | 2.5 [27] | Molecular visualization | Structure analysis and validation |

| VMD | 1.9.4 [27] | Visualization and analysis | Trajectory analysis and structure quality checks |

| MODELLER | 10.7 [27] | Homology modeling | Protein structure completion for missing residues |

| CoPoP | CoPoP Liposome|Cobalt Porphyrin-Phospholipid|RUO | CoPoP (Cobalt Porphyrin-Phospholipid) for his-tagged antigen display in vaccine research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| bPiDI | bPiDI, MF:C22H34I2N2, MW:580.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Table 2: Recommended Hardware Configurations

| Component | High-Performance Workstation | Standard Research Computer |

|---|---|---|

| Processor | Intel Core i9-14900K × 32 [27] | AMD Ryzen 5 5600x 6-core [27] |

| Memory | 32 GB RAM [27] | 32 GB RAM [27] |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 [27] | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 [27] |

| Storage | 5.9 TB [27] | 2.5 TB [27] |

| Operating System | Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS [27] | Ubuntu 22.04.3 LTS [27] |

Specialized force fields provide the fundamental parameters governing atomic interactions during minimization and equilibration. For protein-ligand systems, recommended force fields include:

- AMBER ff14SB [2]: For protein parameters, offering improved side chain torsions and backbone adjustments.

- OpenFF-2.2.1 [2]: For small molecule force fields, providing accurate ligand parameterization.

- TIP3P [2]: For water models, balanced between computational efficiency and accuracy.

Additional specialized force fields like CHARMM36 and GAFF may be selected based on specific system requirements and research group experience [27] [26].

Core Methodological Framework

The following section outlines a comprehensive, step-by-step protocol for energy minimization and equilibration of protein-ligand complexes, synthesizing best practices from established methodologies [2] [27] [28].

Figure 1: Complete workflow for energy minimization and equilibration of protein-ligand complexes, showing the sequential steps from initial structure to stable system ready for production MD.

System Preparation and Parameterization

A. Initial Structure Preparation

Begin with a high-resolution structure of the protein-ligand complex, preferably from crystallography or cryo-EM. For modeled complexes, ensure the binding pose is validated through docking scores and interaction analysis [27] [28].

Structure Processing:

- Remove crystallographic water molecules except those forming critical bridging interactions with the ligand (typically within 5Ã…) [28].

- Add missing hydrogen atoms using tools like PyMOL or CHARMM-GUI, adjusting protonation states to match physiological pH (e.g., GLU, ASP deprotonated; LYS, ARG protonated) [27].

- For histidine residues, determine the appropriate protonation state (HID, HIE, or HIP) based on the local hydrogen bonding environment.

Ligand Parameterization:

- Generate ligand parameters using appropriate tools:

- Assign partial charges using AM1-BCC [2] or higher-level quantum mechanical methods for critical interactions.

B. Solvation and Ion Placement

Solvation:

Ion Addition:

Staged Energy Minimization Protocol

A multi-stage minimization approach gradually relaxes the system while maintaining structural integrity [27] [28]. The following protocol employs sequentially decreasing restraint weights:

Table 3: Staged Energy Minimization Parameters

| Stage | Restraints Applied | Force Constant | Algorithm | Convergence Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Heavy Restraint | All protein and ligand heavy atoms | 500 kcal/mol/Ų [28] | Steepest Descent | Maximum force < 1000 kJ/mol/nm |

| 2. Backbone Restraint | Protein backbone atoms only | 50 kcal/mol/Ų [28] | Conjugate Gradient | Maximum force < 500 kJ/mol/nm |

| 3. Full System | No restraints | Not applicable | L-BFGS | Maximum force < 100 kJ/mol/nm |

Implementation Notes:

- Stage 1: This strong restraint stage relieves severe steric clashes while maintaining the overall protein-ligand structure.

- Stage 2: With reduced restraints on side chains, this allows side chain rearrangements and relief of localized strains.

- Stage 3: The final stage allows the entire system to relax to a local energy minimum without constraints.

Monitor convergence through the evolution of the potential energy and the maximum force. The minimization should proceed until the energy change between steps becomes negligible and forces fall below the specified thresholds.

System Equilibration Procedure

Following minimization, the system requires careful equilibration to reach the target thermodynamic state. The protocol below describes a multi-stage approach:

Table 4: Detailed Equilibration Protocol Parameters

| Stage | Ensemble | Restraints | Temperature | Duration | Thermostat/Barostat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heating | NVT | Protein and ligand heavy atoms (force: 50 kcal/mol/Ų) [28] | 0K → 100K → 200K → 300K | 50-100 ps per step | Langevin (collision frequency: 1 psâ»Â¹) [2] |

| Density Equilibration | NPT | Protein and ligand heavy atoms (force: 10 kcal/mol/Ų) [28] | 300K | 100-200 ps | Berendsen [28] → Parrinello-Rahman [2] |

| Unrestrained Equilibration | NPT | None | 300K | 500 ps - 1 ns | Nosé-Hoover [2] |

Critical Steps:

Heating Phase:

- Gradually increase system temperature in steps while maintaining strong positional restraints on protein and ligand heavy atoms.

- Use a Langevin thermostat with a collision frequency of 1.0 psâ»Â¹ for efficient temperature coupling [2].

Density Equilibration:

- Switch to NPT ensemble with moderate positional restraints (10 kcal/mol/Ų) on solute heavy atoms.

- Use semi-isotropic pressure coupling for membrane systems or isotropic for soluble proteins.

- Initially use Berendsen barostat for rapid equilibration, then switch to Parrinello-Rahman for production dynamics [2].

Unrestrained Equilibration:

- Remove all positional restraints for final equilibration.

- Monitor system stability through potential energy, temperature, pressure, density, and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of protein backbone and ligand heavy atoms.

Validation and Quality Assessment

Before proceeding to production MD, validate the equilibrated system through multiple checks to ensure stability and proper equilibration.

A. Stability Metrics

- Energy Stability: The total potential energy should fluctuate steadily around a stable average without drifts.

- Temperature and Pressure: These should oscillate around the target values (300K, 1 bar) with reasonable fluctuations.

- Density: For aqueous systems, the density should converge to approximately 1000 kg/m³ for TIP3P water models.

B. Structural Integrity

- RMSD Analysis: Calculate the backbone RMSD relative to the minimized structure. The system is considered equilibrated when RMSD plateaus, typically within 1-3 Ã… for most globular proteins.

- Ligand Pose Stability: Monitor ligand RMSD to ensure it remains bound in the initial binding mode with minimal deviation.

- Secondary Structure Preservation: Verify that α-helices and β-sheets maintain their proper geometry through tools like DSSP.

C. Equilibration Duration Determination

The required equilibration time varies by system size and complexity. Use the following criteria to determine sufficient equilibration:

- Potential energy, temperature, and pressure show stable fluctuations around their averages.

- System density has stabilized to the expected value for the water model and conditions.

- Protein backbone RMSD has reached a plateau phase.

For typical protein-ligand systems (20,000-50,000 atoms), complete equilibration generally requires 1-5 ns total simulation time across all stages [2] [28].

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Membrane Protein Systems

For membrane-embedded proteins such as GABA (A) receptors [27], additional considerations apply:

- Membrane Embedding: Use tools like CHARMM-GUI to properly orient and embed the protein in a lipid bilayer (e.g., POPC membrane).

- Extended Minimization: Implement additional minimization steps with strong restraints on lipid headgroups to prevent membrane deformation.

- Staged Membrane Equilibration: Equilibrate the membrane with progressively decreasing restraints on lipid molecules while maintaining protein restraints.

Enhanced Sampling Preparations

When preparing systems for advanced sampling techniques like umbrella sampling or free energy perturbation:

- Extended Equilibration: Run longer equilibration phases (5-10 ns) to ensure thorough sampling of the bound state.

- Multiple Replicas: Generate multiple independent equilibration trajectories from different initial velocities to confirm convergence.

- Collective Variable Stability: Monitor proposed collective variables during equilibration to ensure they adequately describe the system dynamics.

Robust energy minimization and equilibration protocols provide the essential foundation for reliable molecular dynamics simulations of protein-ligand complexes. The staged approach outlined here—progressing from strongly restrained minimization through gradual heating and finally to unrestrained equilibration—ensures system stability while maintaining structural integrity. Through careful parameter selection, systematic execution, and rigorous validation, researchers can establish physically realistic starting points for subsequent production simulations and binding free energy calculations. This methodological framework supports accurate investigation of protein-ligand interactions across diverse biological systems, from soluble enzymes to membrane-bound receptors, advancing both fundamental understanding and drug discovery efforts.

Advanced Simulation Protocols and Analysis for Binding Kinetics and Energetics

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in structural biology and drug discovery, providing atomic-level insights into the behavior of biomolecular systems over time. For the study of protein-ligand complexes, MD simulations offer a dynamic perspective that static crystal structures cannot, revealing conformational changes, binding pathways, and residence times critical for understanding drug action [30]. The configuration of production simulations—particularly the careful selection of timescales and parameters—represents a pivotal phase that directly determines the reliability and biological relevance of the simulation outcomes. Properly configured production runs can capture functionally relevant motions, quantify binding energetics, and provide insights into mechanisms of action, thereby bridging the gap between structural data and biological function [31] [32].

This protocol outlines a comprehensive methodology for configuring and executing production-level MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes, with emphasis on parameter selection, timescale considerations, and validation metrics appropriate for drug discovery research.

Fundamental Concepts and Simulation Timescales

Timescales of Biomolecular Processes

Different biological processes occur across vastly different timescales, which must be matched with appropriate simulation durations to obtain statistically meaningful results [30] [32]. The table below summarizes key protein-ligand dynamic events and their characteristic timescales:

Table 1: Characteristic Timescales for Protein-Ligand Dynamic Processes

| Dynamic Process | Typical Timescale | Simulation Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Side chain rotations | Picoseconds (10â»Â¹Â² s) to nanoseconds (10â»â¹ s) | Local flexibility, minor binding site adjustments |

| Loop motions | Nanoseconds to microseconds (10â»â¶ s) | Gating of binding sites, accessible conformations |

| Ligand binding/unbinding | Microseconds to seconds | Residence time, binding affinity, drug efficacy |

| Large domain movements | Microseconds to milliseconds (10â»Â³ s) | Allosteric regulation, major conformational changes |

| Protein folding | Milliseconds to seconds | Not typically addressed in ligand-binding studies |

Evolution of Accessible Simulation Times

The trajectory of MD simulation capabilities shows exponential growth in accessible timescales:

Table 2: Historical Progression of MD Simulation Capabilities

| Time Period | Typical Simulation Duration | System Size | Notable Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970s | Picoseconds (10â»Â¹Â² s) | ~500 atoms | First protein simulation (BPTI, 9.2 ps) [32] |

| 1990s | Nanoseconds (10â»â¹ s) | ~10,000 atoms | Protein folding simulations, solvation studies |

| 2000s | Tens to hundreds of nanoseconds | ~100,000 atoms | Membrane protein simulations, ligand binding |

| 2010s | Microseconds (10â»â¶ s) to milliseconds | Millions of atoms | GPCR activation, protein folding, viral capsids |

| Present (2020s) | Milliseconds and beyond | Hundreds of millions of atoms | Entire organelles, gene simulation (1 billion atoms) [30] |

Modern research demonstrates that long-timescale simulations (hundreds of microseconds) can reveal critical functional insights. For example, simulations aggregating 400-500 μs revealed how different protein kinase C activators (bryostatin, phorbol esters) differentially position the complex in membranes—a finding with profound implications for drug design [31].

System Configuration and Parameterization

Force Field Selection

The choice of force field constitutes a fundamental parameter that determines the accuracy of your simulation. Force fields provide the mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of a molecular system [33] [32].

Table 3: Comparison of Common All-Atom Force Fields for Protein-Ligand Simulations

| Force Field | Proteins | Lipids | Nucleic Acids | Small Molecules | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM | CHARMM36m | CHARMM36 | CHARMM36 | CGenFF | Optimized for membrane systems; accurate lipid/protein interactions [32] |

| AMBER | ff19SB/ff14SB | LIPID21 | OL15/OL3 | GAFF | Balanced accuracy for proteins & nucleic acids; widely used [34] [32] |

| OPLS-AA | OPLS-AA/M | OPLS/L | - | - | Optimized for thermodynamic properties; good for peptides [32] |

| GROMOS | 54A8 | 54A8 | 54A8 | - | United-atom approach; faster calculations [32] |

Simulation Parameters and Their Physical Significance

Production simulations require numerous parameters that collectively define the thermodynamic state and numerical integration scheme:

Integration Algorithms

- Velocity Verlet: Most common; numerically stable; good energy conservation

- Leap-frog: Computationally efficient; slightly less accurate [30]

- Time step: Typically 2 fs for all-atom simulations with constrained bonds involving hydrogens [34]

Thermodynamic Ensembles

- NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, Temperature): Most common for biomolecular simulations; mimics experimental conditions

- NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature): Useful for specific properties; less common for production

- Temperature coupling: Langevin thermostat or Nosé-Hoover chains maintain constant temperature [34]

- Pressure coupling: Parrinello-Rahman or Berendsen barostat maintain constant pressure (1 atm) [32]

Long-Range Electrostatics

- Particle Mesh Ewald (PME): Gold standard; accounts for long-range electrostatic interactions in periodic systems

- Cut-off methods: Less accurate but computationally cheaper; not recommended for production simulations [30]

Production Simulation Protocol

Pre-Production System Validation

Before initiating production simulations, thorough system validation is essential:

- Energy Minimization: 500-5000 steps of steepest descent or conjugate gradient to remove bad contacts [34]

- Equilibration Protocol:

- Stage 1: 100 ps NVT simulation with positional restraints on protein and ligand (5 kcal molâ»Â¹ Ã…â»Â²)

- Stage 2: 500 ps NPT simulation with restraints on ligand and protein backbone only [34]

- Equilibration Validation:

- Stable potential energy (drift < 1-2%)

- Protein backbone RMSD plateau (< 1.5-2 Ã… from starting structure)

- Proper density convergence (~1 g/cm³ for aqueous systems)

Production Run Configuration

The production phase involves parameter choices that balance computational cost with scientific rigor:

Duration Guidelines

- Minimal sampling: 100 ns per system for initial assessment

- Adequate sampling: 500 ns - 1 μs for most protein-ligand conformational changes

- Comprehensive sampling: >1 μs for large-scale motions, binding/unbinding events [31]

System Sizing and Boundary Conditions

- Periodic Boundary Conditions: Standard approach to minimize edge effects

- Water padding: Minimum 10-15 Ã… between protein and box edge

- System size: Typically 50,000-200,000 atoms for a solvated protein-ligand complex [30]

Data Collection Parameters

- Trajectory saving frequency: Every 10-100 ps (balances resolution with storage)

- Energy data: Every 1-10 ps for thermodynamic analyses

- Checkpoint files: Frequent saves (every 1-5 ns) for simulation restart capability

Workflow for production MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Software and Tools for Production MD Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Software | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Engines | GROMACS [30] [32] | High-performance MD simulation | Excellent parallelization; widely used in academia |

| AMBER [30] [32] | MD simulation and analysis | Comprehensive toolset; strong force field development | |

| NAMD [30] [32] | Scalable MD simulations | Excellent for large systems; familiar interface | |

| System Preparation | CHARMM-GUI [32] | Membrane system building | Streamlines complex system setup |

| PACKMOL [34] | Initial system configuration | Solvation and ion placement | |

| Force Fields | CGenFF/GAFF [32] | Small molecule parameters | Ligand parameterization for drug-like molecules |

| Analysis Tools | VMD [34] [32] | Trajectory visualization and analysis | Extensive plugin ecosystem |

| MDTraj [30] | High-throughput analysis | Python-based; programmable analysis | |

| Specialized Methods | Thermal Titration MD [34] | Binding stability assessment | Qualitative estimation of protein-ligand stability |

| Citfa | Citfa, MF:C25H35NO2, MW:381.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| C-Gem | C-Gem Prodrug|Thioredoxin Reductase-Actated | C-Gem is a gemcitabine prodrug activated by thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Validation and Analysis Metrics

Simulation Stability Assessment

A production simulation must demonstrate physical stability before subsequent analysis:

- Potential Energy: Stable with fluctuations < 1-2% of total value

- Temperature and Pressure: Stable at target values (fluctuations < 5-10%)

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD):

- Protein backbone: Should plateau, typically < 2-3 Ã…

- Binding site residues: < 1.5 Ã… for reliable binding mode analysis

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF):

- Should reflect expected flexibility (loops > secondary structure)

- Compare with B-factors from crystal structures when available

Advanced Analysis for Protein-Ligand Complexes

- Interaction Fingerprints: Hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, salt bridges [34]

- Binding Free Energy Calculations: MM-PBSA, MM-GBSA, or free energy perturbation [30]

- Residence Time Estimation: Markov State Models or specialized sampling [31]

- Cluster Analysis: Identify predominant conformational states

Configuring production MD simulations for protein-ligand complexes requires careful consideration of timescales, force field parameters, and sampling protocols. The guidelines presented here provide a framework for generating statistically robust simulations that can capture biologically relevant phenomena. As MD simulations continue to evolve with advancing computational resources and more accurate force fields, their role in drug discovery and structural biology will further expand, offering unprecedented insights into the dynamic nature of protein-ligand interactions [31] [30] [32]. Properly configured production simulations serve as a critical methodology for connecting structural information to biological function and therapeutic intervention.

Within the framework of a broader thesis on methodology for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes, the analysis of trajectories using Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) stands as a cornerstone for evaluating structural stability, flexibility, and conformational changes. These metrics provide indispensable quantitative insights into biomolecular behavior at the atomic level, forming a critical bridge between simulated dynamics and biological function interpretation. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, proficiency in RMSD and RMSF analysis is fundamental for validating simulation stability, identifying flexible protein regions, assessing ligand binding stability, and ultimately informing rational drug design strategies. This protocol details the theoretical foundations, practical computational methodologies, and interpretive frameworks for applying RMSD and RMSF analysis within protein-ligand MD simulation research.

Theoretical Foundations

Mathematical Definitions

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) quantifies the average deviation of atomic positions in a structure compared to a reference conformation over time. It is calculated using the equation:

[ RMSD = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N}\deltai^2} ]

where (N) represents the number of atoms, and (\delta_i) is the distance between atom (i) and the corresponding atom in the reference structure after optimal superposition [35] [36]. The most commonly used unit in structural biology is the Ångström (Å) [36].

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) measures the deviation of atomic positions from their average structure over time, characterizing the flexibility of individual residues or atoms. While mathematically related to RMSD, RMSF focuses on fluctuations around the mean position rather than deviation from a specific reference structure [36].

Biological Significance in Protein-Ligand Complexes

In protein-ligand studies, RMSD provides crucial information about system stability and conformational changes. A low RMSD (typically < 2-3 Ã…) indicates structural stability, suggesting the simulation has reached equilibrium and the protein-ligand complex remains stable. A high RMSD (>3 Ã…) suggests significant conformational changes, which could indicate structural instability, domain movements, or ligand dissociation [35]. RMSF analysis reveals flexible regions of the protein, often highlighting loop regions, terminal ends, or binding sites that undergo conformational adjustments upon ligand binding [37]. Comparing RMSF profiles between apo and ligand-bound proteins can identify residues whose flexibility is modulated by ligand interaction, providing insights into binding mechanics and allosteric effects [37].

Computational Protocols

RMSD Analysis Workflow

Table 1: Key Steps in RMSD Analysis Workflow

| Step | Description | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Reference Selection | Choose appropriate reference structure (often the initial frame or experimental structure) | Initial frame (t=0) typically used |

| 2. Atom Selection | Select atoms for calculation (backbone, Cα, or heavy atoms) | Backbone atoms recommended for protein stability assessment [35] |

| 3. Trajectory Superposition | Align trajectories to reference structure to remove global translation/rotation | Optimal rigid body superposition using Kabsch algorithm [36] |

| 4. RMSD Calculation | Compute RMSD for each frame against reference | GROMACS: gmx rms; MDAnalysis: rms.RMSD() [35] [38] |

| 5. Visualization | Plot RMSD vs. time to assess stability | Python: matplotlib; Grace: xmgrace [35] |

GROMACS Implementation

For MD trajectories analyzed using GROMACS, the RMSD calculation protocol is as follows:

This command generates RMSD values for each time point, which can be plotted to visualize structural stability over time [35].

Python MDAnalysis Implementation

For custom analysis or integration into analysis pipelines, Python's MDAnalysis package provides flexible RMSD calculation:

This approach allows for customized atom selections and seamless integration with other analysis methods [35] [38].

RMSF Analysis Workflow

Table 2: Key Steps in RMSF Analysis Workflow

| Step | Description | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Average Structure | Generate average structure from aligned trajectory | MDAnalysis: align.AlignTraj() [38] |

| 2. Atom Selection | Select specific atoms (typically Cα or backbone) | Cα atoms recommended for residue-level flexibility [37] |

| 3. RMSF Calculation | Compute fluctuation of each atom around mean position | GROMACS: gmx rmsf; MDAnalysis: rms.RMSF() |

| 4. Per-Residue Analysis | Calculate RMSF per residue for protein flexibility | Use -res flag in GROMACS [37] |

| 5. Visualization | Plot RMSF per residue; map to structure | Python: matplotlib; PDB output for visualization [37] |