3D-QSAR in Cancer Drug Discovery: Techniques for Optimizing Anticancer Compounds

This article provides a comprehensive overview of 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) techniques and their pivotal role in optimizing anticancer compounds.

3D-QSAR in Cancer Drug Discovery: Techniques for Optimizing Anticancer Compounds

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) techniques and their pivotal role in optimizing anticancer compounds. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational principles, key methodological approaches including CoMFA, SOMFA, and Topomer CoMFA, and their practical applications against targets like HER2, EGFR, and aromatase. The content also addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for common challenges such as molecular alignment and model overfitting, and outlines robust validation protocols to ensure predictive reliability. By integrating 3D-QSAR with modern computational methods like machine learning and molecular docking, this guide serves as a strategic resource for accelerating the rational design of more effective and targeted cancer therapies.

Understanding 3D-QSAR: A Foundational Guide for Cancer Drug Optimization

Fundamental Concepts: From 2D-QSAR to 3D-QSAR

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of computational drug design, founded on the principle that variations in biological activity can be correlated with changes in molecular structure [1]. Classical 2D-QSAR approaches utilize physicochemical parameters—including hydrophobicity (logP), electronic properties (σ), and steric properties (Taft's Es, molar refractivity)—in a mathematical relationship, typically through multiple regression analysis [2]. The general form of a 2D-QSAR equation is Activity = A*P1 + B*P2 + C, where P1 and P2 are physicochemical properties, A and B are fitted coefficients, and C is a constant [2].

3D-QSAR extends this paradigm by incorporating the three-dimensional structural and interaction properties of molecules [1]. Instead of relying on simplistic parameters, 3D-QSAR techniques sample steric and electrostatic fields around aligned molecules within a 3D lattice, correlating these interaction fields with biological activity using robust statistical methods like Partial Least Squares (PLS) [3] [1]. This fundamental shift allows 3D-QSAR to model biomolecular recognition more directly, as it accounts for the spatial arrangement of functional groups and their complementary interactions with biological targets.

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Performance and Strategic Advantages

Direct comparisons of 2D and 3D-QSAR methodologies consistently demonstrate the superior descriptive and predictive power of 3D approaches in most scenarios, particularly when modeling ligand-protein interactions.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of 2D-QSAR vs. 3D-QSAR Models

| Model Type | Dataset | Key Statistical Metrics | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-QSAR [3] | 36 HDAC inhibitors | R² up to 0.937 | Limited to parameter coefficients |

| 3D-QSAR (CoMFA) [3] | 36 HDAC inhibitors | 86.7% variance explained (steric), 82.3% variance explained (electrostatic) | High - 3D contour maps |

| 2D-QSAR (Machine Learning) [4] | 76 SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors | Test set R² = 0.72 (best model) | Limited - "Black box" concerns |

| 3D-QSAR (Field-based) [4] | 76 SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors | Test set R² = 0.71-0.72 | High - Visual field coefficients |

A comprehensive 2023 study directly addressing this comparison concluded that "many more significant models were obtained when combining 2D and 3D descriptors," attributing this improvement to the ability of "2D and 3D descriptors to code for different, yet complementary molecular properties" [5]. However, the unique strength of 3D-QSAR lies not only in its predictive accuracy but particularly in its interpretative capability through visual representation.

Key Strategic Advantages of 3D-QSAR

Spatial Understanding of Activity: 3D-QSAR provides visual contour maps that highlight regions where specific molecular properties enhance or diminish biological activity [1] [4]. For example, a study on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors identified favorable steric interactions near a chlorobenzyl moiety and favorable electrostatic contributions from specific carbonyl groups [4].

Handling of Conformational Dependence: Unlike 2D methods, 3D-QSAR explicitly accounts for molecular conformation and alignment, which is critical for modeling interactions with structurally defined binding sites [5].

Guidance for Molecular Design: The visual output of 3D-QSAR directly suggests structural modifications—such as adding, removing, or repositioning functional groups—to optimize activity [4].

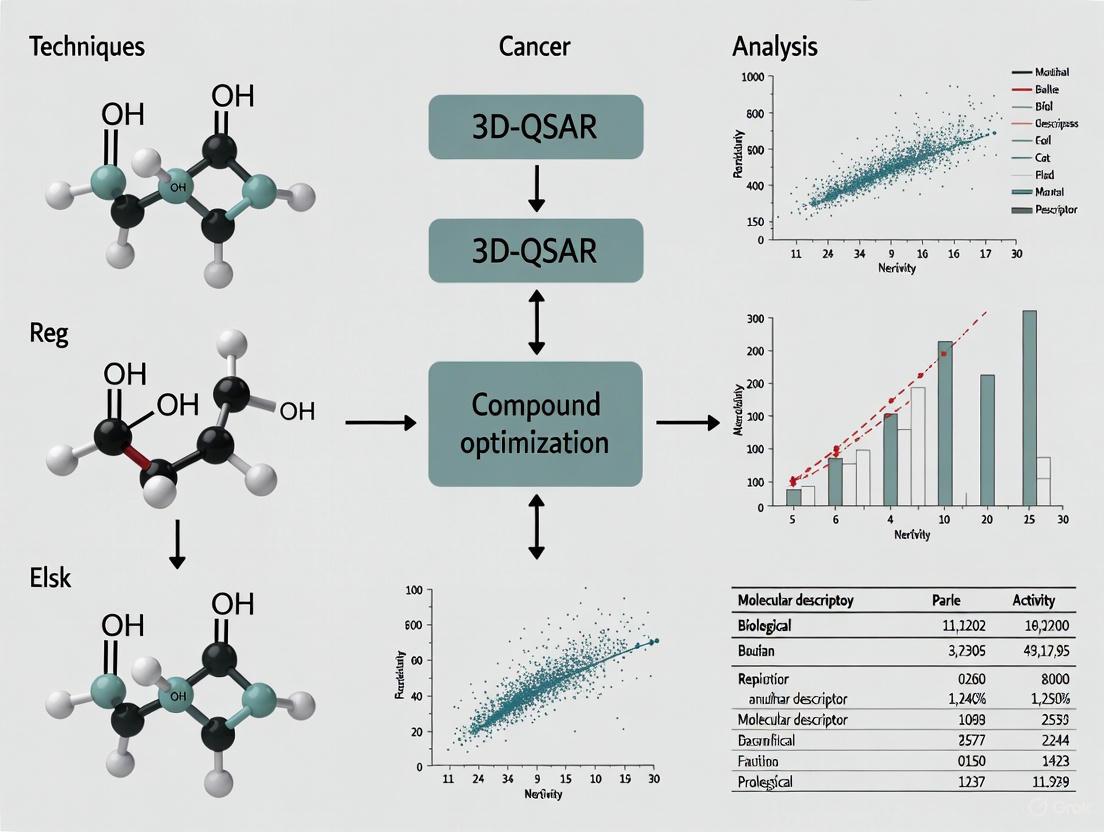

Diagram 1: 3D-QSAR Workflow for Cancer Compound Optimization

Core Methodologies and Protocols in 3D-QSAR

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA)

CoMFA, the pioneering 3D-QSAR technique, follows a standardized protocol [1]:

- Conformation Determination: Identify bioactive conformations, typically through crystallographic data or molecular docking.

- Molecular Alignment: Superimpose molecules using a common scaffold or pharmacophoric pattern.

- Grid Placement: Surround aligned molecules with a 3D lattice (typically 2.0 Ã… spacing).

- Field Calculation: Compute steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies at each grid point using a probe atom.

- Statistical Analysis: Apply PLS regression to correlate field values with biological activity.

- Validation: Use leave-one-out cross-validation to determine model robustness (q²).

- Visualization: Generate 3D contour maps showing regions where specific fields enhance or reduce activity.

A CoMFA study on PDE4 inhibitors demonstrated this protocol's effectiveness, achieving a cross-validated q² of 0.565 and a conventional R² of 0.867, successfully guiding the design of more potent inhibitors [1].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA)

CoMSIA addresses several CoMFA limitations by employing Gaussian-type distance functions and incorporating additional molecular fields [1]:

- Similarity Field Calculation: Computes steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor fields using a Gaussian function to avoid singularities.

- No Cut-off Requirements: The smooth distance dependence eliminates the need for arbitrary energy cut-offs.

- Enhanced Interpretation: The additional fields, particularly hydrophobicity and explicit hydrogen bonding, provide a more comprehensive interaction profile.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Primary Function in 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | SYBYL [1], Chem-X [3], Flare [4] | Provides integrated environment for CoMFA/CoMSIA calculations |

| Field Calculation | Cresset FieldStere [4], OpenEye ROCS & EON [6] | Generates molecular interaction fields and shape descriptors |

| Statistical Analysis | PLS (Partial Least Squares) [3] [1] | Correlates field variables with biological activity |

| Alignment Tools | Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) [4], Database Alignment | Superimposes molecules for field comparison |

| Docking Software | Molecular docking algorithms [7] | Determines putative bioactive conformations |

Applications in Cancer Compound Optimization

3D-QSAR has demonstrated significant utility in optimizing anticancer agents, with several case studies highlighting its practical impact:

Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitors

A seminal study on 36 indole amide hydroxamic acids as HDAC inhibitors established robust 2D and 3D-QSAR models [3]. While the 2D-QSAR achieved a high R² of 0.937, the 3D-QSAR CoMFA model provided spatial insights into steric and electrostatic requirements, explaining 86.7% and 82.3% of variance in respective fields. Docking simulations complemented these findings by highlighting critical interactions with the catalytic Zn²⺠ion. Based on these models, researchers proposed three novel compounds predicted to possess enhanced biological activity [3].

Kinase-Targeted Therapies

Receptor-based 3D-QSAR approaches have proven particularly valuable in kinase studies, combining molecular docking for pose prediction with conventional 3D-QSAR for activity correlation [8]. This hybrid methodology leverages structural information from kinase-inhibitor complexes to generate more reliable alignments and interpret results within a structural context, accelerating the optimization of selective kinase inhibitors for cancer therapy.

Adenosine A1 Receptor Antagonists

In a comprehensive drug discovery campaign for breast cancer therapeutics, researchers employed 3D-QSAR as part of an integrated computational workflow [7]. After identifying the adenosine A1 receptor as a promising target through bioinformatics analysis, the team utilized 3D-QSAR to guide the rational design of a novel compound (Molecule 10) that exhibited remarkable potency against MCF-7 breast cancer cells (IC₅₀ = 0.032 µM), significantly outperforming the positive control 5-FU [7].

Diagram 2: 3D-QSAR in Cancer Drug Discovery Pipeline

Protocol Implementation: Practical Guide for Cancer Research Applications

Standard CoMFA Protocol for Kinase Inhibitor Optimization

Based on established methodologies [1] [4], the following protocol provides a framework for implementing 3D-QSAR in cancer compound optimization:

Dataset Curation

- Collect 20-50 compounds with measured ICâ‚…â‚€ or Ki values against the cancer target

- Ensure structural diversity while maintaining a common scaffold

- Divide compounds into training (70-80%) and test sets (20-30%) using activity stratification

Molecular Alignment

- Identify maximum common substructure (MCS) using tools in SYBYL or Flare

- Align molecules based on MCS or pharmacophoric features

- Validate alignment quality through visual inspection and RMSD calculations

Field Calculation Parameters

- Grid spacing: 2.0 Ã… in x, y, z directions

- Probe atom: sp³ carbon with +1 charge

- Steric field: Lennard-Jones 6-12 potential

- Electrostatic field: Coulombic potential with distance-dependent dielectric

Statistical Analysis and Validation

- Perform PLS regression with leave-one-out cross-validation

- Require q² > 0.5 for predictive models

- Use bootstrapping or Y-scrambling to assess model robustness

- Validate with external test set (predicted R² > 0.6)

Model Interpretation and Design

- Generate steric and electrostatic contour maps at 80% and 20% contribution levels

- Identify regions where bulky substituents enhance (green) or diminish (yellow) activity

- Locate areas favoring electron-donating (blue) or electron-withdrawing (red) groups

- Propose structural modifications based on contour guidance

This protocol, when applied to a series of choline kinase inhibitors, yielded models with exceptional predictive power (q² > 0.99 for CoMFA and CoMSIA), enabling rational design of potent anticancer agents [2].

3D-QSAR represents a significant advancement over traditional 2D-QSAR methods by incorporating the critical third dimension of molecular structure and interaction fields. While 2D descriptors maintain utility for rapid screening and preliminary analysis, 3D-QSAR provides superior interpretability and direct structural guidance for molecular optimization. The technique's demonstrated success across multiple cancer drug discovery programs—from HDAC inhibitors to kinase-targeted therapies—confirms its enduring value in the medicinal chemist's toolkit. As 3D-QSAR methodologies continue to evolve through integration with machine learning and enhanced receptor-based approaches, their impact on cancer compound optimization is poised to expand further, accelerating the development of novel therapeutic agents against this complex disease.

The Critical Role of 3D-QSAR in Modern Cancer Drug Discovery

Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has emerged as a transformative computational approach in modern anticancer drug discovery. By correlating the three-dimensional molecular properties of compounds with their biological activities, 3D-QSAR provides critical insights that guide the rational design and optimization of novel therapeutic agents. This application note explores the fundamental principles, methodological workflows, and successful implementations of 3D-QSAR techniques specifically in cancer research contexts. We present comprehensive protocols for building, validating, and applying 3D-QSAR models, along with detailed case studies demonstrating their efficacy in optimizing compounds against various cancer targets, including dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and breast cancer targets. The integration of 3D-QSAR with complementary computational methods such as molecular docking and ADMET profiling creates a powerful framework for accelerating anticancer drug development while reducing experimental costs.

Fundamental Principles

Traditional Two-Dimensional QSAR (2D-QSAR) methods utilize numerical descriptors derived from molecular structure to predict biological activity but lack consideration of the spatial orientation of molecules [9]. In contrast, 3D-QSAR incorporates the three-dimensional structural properties of ligands, providing a more comprehensive analysis of ligand-receptor interactions [10]. This approach is particularly valuable in cancer drug discovery, where understanding the spatial and electrostatic complementarity between potential drug candidates and their target binding sites is crucial for designing effective therapeutics.

The underlying hypothesis of 3D-QSAR is that differences in the three-dimensional structural properties of molecules are responsible for variations in their biological activities [10]. By quantifying these spatial relationships, researchers can identify key molecular features that contribute to anticancer efficacy and optimize lead compounds accordingly. 3D-QSAR has evolved into an indispensable predictive tool in the design of pharmaceuticals, significantly decreasing the number of compounds that need to be synthesized by facilitating the selection of the most promising candidates [10].

Key Methodological Approaches

Two primary computational techniques dominate the 3D-QSAR landscape: Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) [11]. CoMFA calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulomb) fields on a 3D grid surrounding aligned molecules, using a probe atom to measure interaction energies at each grid point [9]. This method provides detailed maps of regions where steric bulk or electrostatic charges influence biological activity.

CoMSIA extends this approach by employing Gaussian-type functions to evaluate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields, which results in smoother potential maps and reduced sensitivity to molecular alignment [9]. The enhanced descriptor set in CoMSIA provides more comprehensive insights into structure-activity relationships, particularly for structurally diverse datasets. Both methods utilize statistical techniques, primarily Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, to correlate field descriptors with biological activity values [11].

Computational Workflows and Protocols

Molecular Modeling and Alignment

The initial phase in 3D-QSAR model development involves preparing high-quality three-dimensional molecular structures. This process begins with converting two-dimensional chemical representations into three-dimensional coordinates using cheminformatics tools such as RDKit or Sybyl [9]. The resulting 3D structures undergo geometry optimization through molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., UFF) or quantum mechanical methods to ensure they adopt realistic, low-energy conformations [9].

Molecular alignment represents the most critical step in 3D-QSAR and demands meticulous attention. As noted by Cresset, "The majority of the signal is in the alignments, so you need to get those right. If your alignments are incorrect your model will have limited or no predictive power" [12]. Alignment can be achieved through several approaches:

- Common Scaffold Alignment: Using the Bemis-Murcko method to define a core structure by removing side chains and retaining only ring systems and linkers [9]

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS): Identifying the largest substructure shared among a set of molecules, useful for comparing diverse chemotypes [9]

- Field and Shape-Guided Alignment: Employing molecular field similarity to align compounds based on their electrostatic and shape properties [12]

A recommended protocol involves selecting a representative, highly active compound as an initial reference, aligning the dataset to this reference, identifying poorly aligned molecules, promoting well-aligned examples to additional references, and iterating until satisfactory alignment is achieved for all compounds [12].

Figure 1: Comprehensive 3D-QSAR Workflow for Cancer Drug Discovery. This flowchart illustrates the iterative process of model development, validation, and application in designing novel anticancer agents.

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building

Following molecular alignment, the next critical step involves calculating 3D molecular descriptors that numerically represent the steric and electrostatic environments of each molecule. In CoMFA, this is achieved by placing a lattice of grid points around the aligned molecules and using a probe atom (typically an sp³ carbon with a +1 charge) to measure steric (van der Waals) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies at each grid point [9]. This process effectively maps how a molecular probe "feels" the presence of the molecule at various locations, identifying regions where steric bulk or electrostatic properties influence binding.

CoMSIA extends this approach by calculating similarity indices using a Gaussian-type function for steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor fields [9]. The Gaussian function prevents singularities at atomic positions and provides smoother sampling of the molecular fields, making CoMSIA less sensitive to alignment variations than CoMFA.

With descriptors calculated, model building employs Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate the 3D field descriptors with biological activity values [11]. PLS is particularly suited for 3D-QSAR as it handles the large number of highly correlated descriptors by projecting them onto a smaller set of latent variables. The model undergoes cross-validation, typically using Leave-One-Out (LOO) methodology, to optimize the number of components and prevent overfitting [11].

Model Validation and Interpretation

Rigorous validation is essential to ensure model reliability and predictive power. Internal validation employs LOO cross-validation, where each compound is sequentially excluded from the training set and predicted by a model built from the remaining molecules [13]. The cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) provides the first indicator of model predictivity, with q² > 0.5 generally considered acceptable [11].

External validation using a test set of compounds not included in model development offers a more robust assessment of predictive ability [11]. Additional statistical measures include the conventional correlation coefficient (r²), Fisher ratio (F), standard error of estimate, and bootstrapping analysis [11]. The model's contour maps are then interpreted to identify spatial regions where specific molecular features enhance or diminish biological activity, providing visual guidance for structural optimization [9].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Software Tools for 3D-QSAR in Cancer Research

| Tool Category | Representative Software | Primary Function | Application in Cancer Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | Sybyl [11], ChemBio3D [13], RDKit [9] | 3D structure generation and optimization | Convert 2D chemical structures to 3D representations for cancer targets |

| Conformational Analysis | FieldTemplater [13], Py-ConfSearch [14] | Bioactive conformation identification | Determine likely binding conformations for anticancer compounds |

| Molecular Alignment | Py-Align [14], Forge [12] | Spatial superposition of molecules | Align compound series to common reference frame for field calculation |

| Field Calculation | Py-CoMFA [14], CoMSIA [11] | Steric/electrostatic field computation | Quantify molecular interaction fields around anticancer agents |

| Statistical Analysis | PLS algorithms [11], Py-ComBinE [14] | Model building and validation | Correlate field descriptors with anticancer activity data |

| Visualization | Py-MolEdit [14], Contour maps [9] | Interpretation of results | Visualize regions for structural modification to enhance anticancer activity |

Case Studies in Cancer Drug Discovery

DMDP Derivatives as Dihydrofolate Redase Inhibitors

A seminal application of 3D-QSAR in cancer drug discovery involved a series of 78 DMDP (2,4-diamino-5-methyl-5-deazapteridine) derivatives as potent anticancer agents targeting dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) [11]. DHFR represents a validated anticancer target as it catalyzes the reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate, an essential cofactor in thymidylate and purine synthesis required for DNA replication and cell proliferation [11].

Researchers developed both CoMFA and CoMSIA models, with the CoMFA standard model demonstrating strong predictive power (q² = 0.530, r² = 0.903) and the CoMSIA model showing slightly improved statistics (q² = 0.548, r² = 0.909) [11]. The models successfully predicted the activities of a test set of ten compounds, producing predictive r² values of 0.935 and 0.842, respectively [11]. Contour map analysis revealed that highly electropositive substituents with low steric tolerance were required at the 5-position of the pteridine ring, while bulky electronegative substituents were favored at the meta-position of the phenyl ring [11].

Table 2: Statistical Parameters of 3D-QSAR Models for DMDP Derivatives as Anticancer Agents [11]

| Statistical Parameter | CoMFA Model | CoMSIA Model |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-validated q² | 0.530 | 0.548 |

| Non-cross-validated r² | 0.903 | 0.909 |

| Number of Components | 6 | 6 |

| F-value | 94.349 | Not specified |

| Standard Error of Estimate | 0.386 | Not specified |

| Predictive r² (Test Set) | 0.935 | 0.842 |

| Steric Field Contribution | 52.2% | Not specified |

| Electrostatic Field Contribution | 47.8% | Not specified |

Maslinic Acid Analogs Against Breast Cancer

Another significant application involved 3D-QSAR studies on maslinic acid analogs for anticancer activity against the breast cancer cell line MCF-7 [13]. Maslinic acid, a triterpene derived from olive oil extraction byproducts, demonstrates promising anticancer properties, though no comprehensive 3D-QSAR study had been reported previously [13].

Researchers developed a field-based 3D-QSAR model using 74 compounds with known IC₅₀ values against MCF-7 cells [13]. The derived QSAR model showed excellent statistical parameters (r² = 0.92, q² = 0.75) following leave-one-out cross-validation [13]. The model identified key structural features controlling anticancer activity and toxicity, enabling virtual screening of the ZINC database which yielded 593 initial hits [13]. Subsequent filtering through Lipinski's Rule of Five and ADMET risk assessment identified 39 promising candidates, with compound P-902 emerging as the most promising hit after docking studies against multiple breast cancer targets [13].

Benzimidazole Derivatives as Estrogen Alpha Receptor Antagonists

A recent study demonstrated the integration of 3D-QSAR with other computational methods for identifying novel benzimidazole derivatives as potential treatments for breast cancer targeting the estrogen alpha receptor (ERα) [15]. Researchers developed a pharmacophore model followed by an atom-based 3D-QSAR model with high correlation coefficients (R² = 0.9, Q² = 0.8) [15].

Virtual screening of benzimidazole scaffolds from PubChem, followed by molecular docking against ERα (PDB ID: 3ERT) and ADMET profiling, identified five promising compounds [15]. The top candidate (PubChem ID 3074802) demonstrated a binding affinity of -9.842 kcal/mol, significantly higher than the standard drug tamoxifen (-5.357 kcal/mol), along with favorable pharmacokinetic and low toxicity profiles [15]. This case study exemplifies how 3D-QSAR can be integrated into a comprehensive computational workflow for efficient anticancer lead identification and optimization.

Advanced Protocols and Implementation

Integrated Computational Workflow Protocol

The most effective implementation of 3D-QSAR in cancer drug discovery involves its integration within a broader computational framework:

Data Curation Protocol: Collect a minimum of 20-30 compounds with consistently measured biological activities (e.g., ICâ‚…â‚€ values) against a specific cancer target or cell line. Ensure structural diversity while maintaining a common scaffold for meaningful alignment [9].

Conformational Sampling Protocol: Generate low-energy conformations for each compound using systematic search or stochastic methods. Select the putative bioactive conformation using field-based similarity to known active compounds or through docking into the target protein when available [13].

Alignment Refinement Protocol: Implement the multi-reference alignment strategy described in Section 2.1, spending significant time on alignment quality before any model building activities. Critically, "Once you've hit the QSAR button, you're tainted, and are not allowed to tweak the molecules any more" to avoid statistical bias [12].

Model Optimization Protocol: Calculate both CoMFA and CoMSIA descriptors using a 2Ã… grid spacing. Optimize the region focusing and column filtering parameters to enhance signal-to-noise ratio. Build PLS models with component optimization based on LOO cross-validation [11].

Validation Protocol: Employ both internal (LOO) and external (test set) validation, with the test set comprising 15-20% of the total dataset selected to represent structural diversity and the entire activity range [11].

Figure 2: Molecular Alignment Protocol for 3D-QSAR. This specialized workflow highlights the critical alignment process that significantly influences model quality and predictive power.

Contour Map Interpretation Protocol

The practical application of 3D-QSAR models relies on accurate interpretation of contour maps:

Steric Map Interpretation: Green contours indicate regions where increased steric bulk enhances activity, while yellow contours denote regions where steric bulk decreases activity [9].

Electrostatic Map Interpretation: Blue contours represent regions where positive charge enhances activity, and red contours indicate regions where negative charge enhances activity [9].

Hydrophobicity Map Interpretation (CoMSIA): Yellow contours signify regions where hydrophobic groups favor activity, while white contours indicate regions where hydrophobic groups disfavor activity [13].

Hydrogen Bonding Map Interpretation (CoMSIA): Magenta contours (donor) and cyan contours (acceptor) identify regions where hydrogen bonding capabilities enhance activity [13].

These visual representations translate complex statistical models into intuitive guidance for medicinal chemists, directly suggesting structural modifications to enhance anticancer activity.

3D-QSAR continues to evolve as an indispensable tool in cancer drug discovery, enabling researchers to extract critical structure-activity insights and accelerate the optimization of anticancer agents. The case studies presented demonstrate how 3D-QSAR successfully identifies key structural features influencing anticancer activity across diverse chemical scaffolds and biological targets.

Future developments in 3D-QSAR methodology include the integration of advanced machine learning techniques such as Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), which process molecular graphs as inputs and synthesize atomic information into predictive features [14]. Additionally, network explainability methods are being developed to address the "opaqueness" of complex models, helping researchers understand which molecular regions contribute most significantly to predicted activity [14].

When properly implemented with rigorous alignment protocols and comprehensive validation, 3D-QSAR provides powerful insights that guide medicinal chemistry efforts in cancer drug discovery. By reducing the number of compounds requiring synthesis and testing through informed candidate selection, 3D-QSAR significantly enhances the efficiency of the anticancer drug development pipeline. The continued integration of 3D-QSAR with complementary computational approaches promises to further accelerate the discovery of novel, effective cancer therapeutics.

Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) represents a fundamental advancement over classical QSAR by exploiting the three-dimensional properties of molecules to predict biological activities using robust chemometric techniques [10]. In the context of cancer therapy research, these methods have become indispensable tools for optimizing compound efficacy and overcoming drug resistance. The core principles of molecular fields, conformational analysis, and molecular alignment form the foundational triad of 3D-QSAR, enabling researchers to translate structural information into predictive models for anticancer drug design [16] [10]. The proper application of these principles allows medicinal chemists to identify critical structural features required for biological activity, thereby facilitating the rational design of novel therapeutic agents with enhanced potency and selectivity.

Molecular Fields and Descriptors

Molecular fields describe the spatial distribution of physicochemical properties around molecules, providing quantitative descriptors that correlate with biological activity [10]. These fields capture the essential interaction forces between a ligand and its biological target, including steric bulk, electrostatic potential, hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen-bonding capabilities [16].

The primary 3D-QSAR techniques utilizing molecular fields include Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) [11]. CoMFA calculates steric and electrostatic fields using Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials, typically with a cutoff value of 30 kcal/mol to avoid energy singularities [11]. In contrast, CoMSIA employs a Gaussian-type function to eliminate singularities and incorporates additional fields including hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor properties [16]. The selection of appropriate molecular fields depends on the specific biological target and the nature of ligand-receptor interactions being modeled.

Table 1: Key Molecular Field Types in 3D-QSAR

| Field Type | Physical Significance | Probe Atoms | Application in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steric | Measures shape and bulk constraints | sp³ carbon atom | Optimizing substituents to fit binding pockets [11] |

| Electrostatic | Characterizes charge distribution | +1 charge | Enhancing selectivity through charge complementarity [16] |

| Hydrophobic | Quantifies lipophilicity | Atom-based hydrophobicity | Improving membrane permeability and bioavailability [16] |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | Identifies H-bond donation sites | H-bond donor probe | Targeting key polar interactions in enzyme active sites [16] |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Identifies H-bond acceptance sites | H-bond acceptor probe | Exploiting complementary acceptor regions in targets [16] |

Conformational Analysis in 3D-QSAR

Conformational analysis aims to identify all possible minimum-energy structures of a molecule and establish the relationship between conformational flexibility and biological activity [17]. For flexible drug molecules, this process is critical because the bioactive conformation may not correspond to the global energy minimum, and different conformations can exhibit significantly different binding affinities to biological targets [18].

Several computational approaches exist for conformational sampling, each with distinct advantages:

- Systematic Search Method: Systematically rotates rotatable bonds through defined intervals to explore conformational space [17]

- Random Search Methods: Use stochastic algorithms to generate diverse conformational sets [17]

- Molecular Dynamics: Simulates molecular motion under physiological conditions to identify biologically relevant conformations [17]

- Neural Networks: Employ machine learning to predict stable conformations based on training data [17]

Following conformational generation, energy minimization is performed using force field methods to refine geometries. Subsequent cluster analysis groups similar conformations using root-mean-square distance (RMSD) as a similarity metric, with the lowest-energy representative from each cluster selected for further analysis [17]. In cancer drug discovery, this process is particularly important for designing compounds that target specific conformations of proteins involved in cell cycle regulation, such as CDK2 and tubulin [16].

Molecular Alignment Methodologies

Molecular alignment represents perhaps the most critical step in 3D-QSAR model development, as the results are highly sensitive to the alignment rules and overall orientation of the aligned compounds [11]. Proper alignment ensures that molecules are compared in a biologically relevant manner, mimicking their common binding mode to the target protein.

Table 2: Molecular Alignment Techniques in 3D-QSAR

| Alignment Method | Key Features | Advantages | Statistical Performance (q²/r²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid-Body Fit | Superposition based on common substructure or pharmacophore [17] | Intuitive, preserves structural similarity | Varies by dataset |

| Receptor-Based Alignment | Uses docking poses or co-crystallized conformers [17] | Biologically relevant orientation | CoMFA: q²=0.530, r²=0.903 [11] |

| Pharmacophore-Based Alignment (PBA) | Aligns molecules based on pharmacophoric features [19] | Focuses on key interaction elements | CoMSIA: q²=0.548, r²=0.909 [11] |

| Co-crystallized Conformer-Based Alignment (CCBA) | Uses experimentally determined bound conformation [19] | Highest biological relevance | Superior performance in case studies [19] |

| Distill Alignment | Template-based alignment using most active compound [16] | Optimizes for activity correlation | CoMSIA/SEHDA: Q²=0.814, R²=0.967 [16] |

Selection of the appropriate alignment method depends on available structural information. When available, co-crystallized conformer-based alignment (CCBA) generally provides the most reliable results, as demonstrated in a case study on PTP1B inhibitors where it generated CoMFA models with q²=0.694 and r²=0.992 [19]. For targets without experimental structural data, pharmacophore-based or receptor-based alignments using homology models offer viable alternatives [17].

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol: CoMSIA Model Development for Cancer Therapeutics

This protocol outlines the development of a 3D-QSAR model using CoMSIA, based on a recent study of phenylindole derivatives as multitarget inhibitors in breast cancer therapy [16].

Step 1: Dataset Preparation and Biological Data Curation

- Compile a dataset of compounds with measured biological activities (e.g., ICâ‚…â‚€ values against cancer cell lines)

- Convert concentration values to pICâ‚…â‚€ (-logICâ‚…â‚€) to ensure linear relationship with free energy changes

- Divide dataset into training set (80-85%) for model development and test set (15-20%) for external validation

- Apply diversity analysis to ensure structural and activity ranges are represented in both sets

Step 2: Conformational Analysis and Molecular Alignment

- Generate low-energy conformations using systematic search or molecular dynamics

- Select the most active compound as template for alignment

- Align all molecules using the distill alignment method in SYBYL or similar software

- Verify alignment quality through visual inspection and RMSD calculations

Step 3: CoMSIA Field Calculations

- Create a 3D cubic grid with 2Ã… spacing extending beyond all aligned molecules

- Calculate five CoMSIA fields (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, H-bond donor, H-bond acceptor)

- Use a probe atom with charge +1, radius 1.0Ã…, hydrophobicity +1, and hydrogen bonding properties +1

- Set attenuation factor α to 0.3 for the Gaussian-type distance dependence

Step 4: Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis and Model Validation

- Perform leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation to determine optimal number of components (N)

- Conduct non-cross-validated analysis with optimal N to generate final model

- Validate model using external test set predictions and bootstrapping analysis

- Accept models with q² > 0.5 and r² > 0.8 for reliable predictive capability

Application Note: Alignment Strategies for Flexible Molecules

For datasets containing flexible molecules with high Kier Flexibility Indices (>5.0), traditional alignment methods may prove suboptimal. Recent studies demonstrate that for certain nuclear receptors, including the androgen receptor, non-aligned 2D>3D conversion of structures can produce models with R²Test = 0.61, superior to energy-minimized and conformation-aligned approaches [18]. This alignment-independent 3D-QSDAR technique achieves this performance in only 3-7% of the computational time required for other conformational strategies, making it particularly valuable for large virtual screening campaigns in early-stage anticancer drug discovery [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR in Cancer Research

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Platform | Key Functionality | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | SYBYL [16] [11] | Structure building, optimization, force field calculations | Molecular sketching and Tripos force field optimization |

| 3D-QSAR Development | OpenEye Orion 3D-QSAR [6] | Consensus modeling with shape and electrostatic descriptors | Predict binding affinity using multiple similarity descriptors |

| Online QSAR Platforms | 3D-QSAR.com [20] | Web-based QSAR model development | Ligand-based and structure-based 3D-QSAR modeling |

| Visualization & Analysis | UCSF Chimera [16] | Protein-ligand interaction analysis | Visualization of docking poses and binding interactions |

| Activity Analysis | Flare QSAR [21] | Activity Atlas and Activity Miner components | SAR interpretation through Bayesian analysis of active molecules |

Visualization of Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for 3D-QSAR model development in cancer therapeutic optimization:

The integration of molecular fields, conformational analysis, and alignment methodologies forms the cornerstone of successful 3D-QSAR applications in cancer drug discovery. Recent advances in these areas, particularly the development of robust CoMSIA models and alignment strategies adapted for flexible molecules, have demonstrated significant potential for optimizing anticancer agents [16] [18]. The continued refinement of these core principles, coupled with emerging technologies such as graph neural networks and machine learning approaches, promises to further enhance the predictive power of 3D-QSAR models [20]. For cancer researchers, mastering these fundamental techniques provides a powerful framework for addressing the persistent challenges of drug resistance and selectivity in oncology therapeutics, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective and targeted cancer treatments.

Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) techniques represent a cornerstone of modern computational drug design, particularly when the three-dimensional structure of the biological target remains unknown. These methodologies establish correlations between the biological activities of structurally characterized compounds and the spatial characteristics of their molecular field properties, including steric demand, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobicity [22]. In the specific context of cancer research, 3D-QSAR has emerged as an indispensable tool for optimizing lead compounds against various oncology targets, enabling researchers to understand the structural determinants of anticancer activity and rationally design more potent derivatives. The exponential increase in 3D-QSAR applications over recent decades underscores their value in supporting medicinal chemistry within drug discovery projects focused on oncology [22].

The fundamental premise of 3D-QSAR lies in the concept that differences in biological activity between compounds correlate with changes in their three-dimensional molecular interaction fields. Unlike traditional 2D-QSAR approaches that utilize physicochemical parameters, 3D-QSAR techniques analyze the spatial distribution of molecular properties, providing visual contour maps that directly suggest structural modifications to enhance potency [22]. This spatial understanding is particularly valuable in cancer drug discovery, where researchers can pinpoint specific structural features that influence binding to cancer-related targets such as kinase domains, hormone receptors, and apoptotic pathway components. This article provides a comprehensive overview of three pivotal 3D-QSAR techniques—CoMFA, CoMSIA, and SOMFA—with specific emphasis on their application in cancer compound optimization, complete with experimental protocols and implementation guidelines for research scientists.

Fundamental Techniques and Their Applications in Oncology

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA)

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), pioneered by Cramer et al. in 1988, constitutes the most established 3D-QSAR technique [22]. The method operates on the principle that drug-receptor interactions are primarily governed by non-covalent forces that can be approximated by steric and electrostatic fields. In practice, CoMFA involves placing aligned molecules within a 3D grid and calculating steric (Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (Coulombic potential) energies at each grid point using a probe atom [23]. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression then correlates these field values with biological activity, generating predictive models and visual contour maps that highlight regions where specific molecular modifications would enhance activity.

In cancer drug discovery, CoMFA has demonstrated exceptional utility across multiple target classes. A recent study on quinazoline-4(3H)-one analogs as EGFR inhibitors for breast cancer treatment developed a CoMFA model with strong statistical parameters (R² = 0.872, Q² = 0.597), successfully identifying critical structural features responsible for inhibitory potency [23]. Similarly, CoMFA applications to pyrimidine-based adenosine A2A receptor antagonists for Parkinson's disease treatment (a relevant approach for managing cancer-related fatigue) yielded models with q² = 0.475 and r² = 0.977, enabling the rational design of novel antagonists with improved binding characteristics [24]. The region focusing variation of CoMFA further enhanced predictive ability (q² = 0.637), demonstrating the method's flexibility [24].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA)

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extends beyond CoMFA by incorporating additional molecular fields and employing a Gaussian function type to avoid singularities at atomic positions [22]. While CoMFA considers only steric and electrostatic fields, CoMSIA typically includes hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields in addition to the fundamental steric and electrostatic components. This comprehensive approach often provides more interpretable models, particularly for cancer targets where hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding play critical roles in ligand binding.

The enhanced capability of CoMSIA is evident in a recent study on triazolopyrazine derivatives as VEGFR-2 inhibitors for resistant breast cancer treatment. The CoMSIA model incorporating steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields (CoMSIASEH) demonstrated excellent predictive power (Q² = 0.575, R² = 0.936, R²pred = 0.847) [25]. Similarly, research on quinazoline-based EGFR inhibitors revealed that a CoMSIA model combining steric, hydrophobic, and electrostatic fields (CoMSIASHE) achieved outstanding statistical parameters (R² = 0.982, Q² = 0.666) [23]. In studies of adenosine derivatives as antiplatelet aggregation inhibitors—particularly relevant for cancer patients at risk of thrombosis—CoMSIA yielded a significant model (q² = 0.528, r² = 0.943) that guided the design of novel therapeutic candidates [26]. The additional field types in CoMSIA provide a more nuanced understanding of structure-activity relationships, which is crucial when optimizing compounds for complex cancer targets.

Self-Organizing Molecular Field Analysis (SOMFA)

Self-Organizing Molecular Field Analysis (SOMFA) represents a simpler yet effective 3D-QSAR approach that utilizes molecular shape and electrostatic potential as primary descriptors [27]. Unlike CoMFA and CoMSIA, which rely on grid-based probe interactions, SOMFA calculates a master grid that encapsulates the average molecular properties of all compounds in the dataset. This method directly computes molecular shape and electrostatic potential without requiring probe atoms, potentially offering more intuitive interpretations, though it may capture fewer subtleties in molecular interactions.

In oncology applications, SOMFA has demonstrated robust performance in analyzing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitory activity—a relevant target for cancer prevention and treatment. A SOMFA study on stilbene analogs as COX-2 inhibitors produced a model with substantial statistical quality (r² = 0.806, r²cv = 0.799), which was successfully validated using an external test set (r²Test = 0.651) [28]. Research on adenosine derivatives as antiplatelet agents achieved a SOMFA model with r² = 0.615 and r²cv = 0.577, further confirming the method's utility in drug optimization workflows [26]. While SOMFA models generally exhibit lower statistical parameters than CoMFA or CoMSIA, their computational simplicity and straightforward interpretation make them valuable for initial analyses in cancer drug discovery programs.

Table 1: Comparison of Key 3D-QSAR Techniques in Cancer Research

| Technique | Molecular Fields | Statistical Performance | Advantages | Cancer Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | Steric, Electrostatic | CoMFA_S: R²=0.872, Q²=0.597 [23] | Established method, robust performance | EGFR inhibitors, VEGFR-2 inhibitors, A2A antagonists |

| CoMSIA | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-bond Donor, H-bond Acceptor | CoMSIA_SHE: R²=0.982, Q²=0.666 [23] | Multiple field types, avoids singularities | Breast cancer agents, kinase inhibitors, antiplatelet agents |

| SOMFA | Shape, Electrostatic | r²=0.806, r²cv=0.799 [28] | Simple interpretation, intuitive maps | COX-2 inhibitors, anti-inflammatory agents |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Molecular Alignment Protocols

Proper molecular alignment constitutes the most critical step in 3D-QSAR model development, as the resulting models are highly sensitive to the relative orientation and conformation of the molecules. Several alignment strategies have been developed, each with specific advantages for different scenarios in cancer drug discovery.

The common scaffold-based alignment approach is particularly useful when analyzing congeneric series with shared structural frameworks. In a study on quinazoline-4(3H)-one analogs as EGFR inhibitors, researchers employed the "distill rigid" module in SYBYL-X 2.1.1 software to align molecules based on their quinazolin-4-one common core, using the most active compound (compound 20) as a template [23]. Similarly, research on triazolopyrazine derivatives for breast cancer treatment utilized molecule 22 (the most active compound) as a reference structure for alignment [25]. This method ensures that the fundamental molecular skeleton is consistently positioned across all compounds, allowing the 3D-QSAR model to focus on the effects of substituent variations.

For structurally diverse compounds or when the bioactive conformation is unknown, pharmacophore-based alignment and docking-guided alignment offer viable alternatives. In a study on maslinic acid analogs for breast cancer, researchers used the FieldTemplater module in Forge software to generate a pharmacophore hypothesis from the most active compounds, then aligned all molecules to this template [29]. Docking-guided alignment leverages computational docking to generate putative binding poses, which are then used as alignment references. A study on stilbene analogs as COX-2 inhibitors employed this approach, superposing docked conformations to develop predictive SOMFA models [28]. For cancer targets with available crystal structures, this method can provide more biologically relevant alignments that approximate the true binding mode.

Model Building and Validation Procedures

Robust model building and validation are essential for developing reliable 3D-QSAR models with predictive value in cancer drug discovery. The standard workflow begins with dataset preparation, typically involving 20-50 compounds with measured biological activity (e.g., ICâ‚…â‚€, Ki) against a specific cancer target. Activity values are converted to logarithmic scales (pICâ‚…â‚€ = -logICâ‚…â‚€) to normalize the data distribution [23]. The dataset is then divided into training and test sets, typically using a 70-80%/20-30% ratio, with the test set selected randomly or through sphere exclusion methods to ensure structural and activity diversity [30].

Following molecular alignment, field calculations are performed specific to each 3D-QSAR technique. For CoMFA, steric and electrostatic fields are computed at grid points using a sp³ carbon probe with +1.0 charge and standard energy cutoff of 30 kcal/mol [25]. CoMSIA calculations incorporate additional similarity fields (hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, hydrogen bond acceptor) using a Gaussian function with attenuation factor α = 0.3 [23]. SOMFA computations directly calculate shape and electrostatic potential grids without probe atoms [28].

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression serves as the core statistical method for correlating field values with biological activity. The optimal number of components is determined through leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation, maximizing the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) while minimizing overfitting [29]. The model undergoes multiple validation steps, including:

- Internal validation: Assessed by Q² > 0.5, non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.6, and low standard error of estimate (SEE) [25]

- External validation: Evaluated using the test set with predicted correlation coefficient (R²pred) > 0.6 [28]

- Y-randomization: Confirms model robustness by scrambling activity values and demonstrating significantly worse performance in randomized models [25]

- Applicability domain: Assessed through William's plot (standardized residuals vs. leverage) to identify influential compounds and structural outliers [23]

Table 2: Statistical Parameters for Validated 3D-QSAR Models in Cancer Research

| Parameter | Symbol | Threshold | Example Values | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-validated correlation coefficient | Q² | > 0.5 | 0.560 (CoMFA) [26] | Internal predictive ability |

| Non-cross-validated correlation coefficient | R² | > 0.6 | 0.940 (CoMFA) [26] | Goodness of fit |

| Predicted correlation coefficient | R²pred | > 0.6 | 0.657 (CoMFA) [23] | External predictive ability |

| Standard error of estimate | SEE | Lower is better | 0.097 (CoMFA) [26] | Model precision |

| F-value | F | Higher is better | 71.850 (CoMFA) [26] | Statistical significance |

Model Interpretation and Compound Design

The primary value of 3D-QSAR in cancer drug discovery lies in interpreting contour maps to guide rational compound design. CoMFA steric contours indicate regions where bulky substituents enhance (green) or diminish (yellow) activity, while electrostatic contours highlight areas favoring electron-donating (blue) or electron-withdrawing (red) groups [23]. CoMSIA contours provide additional information on favorable hydrophobic (yellow/unfavorable white), hydrogen bond donor (cyan/unfavorable purple), and acceptor (magenta/unfavorable red) regions [25].

In a practical application, researchers analyzing quinazoline-4(3H)-one EGFR inhibitors used CoMSIA contour maps to identify specific structural modifications that would enhance potency [23]. Similarly, studies on triazolopyrazine VEGFR-2 inhibitors designed six novel compounds based on 3D-QSAR guidance, resulting in predicted improved binding affinities (-8.9 to -10.0 kcal/mol) compared to the reference drug Foretinib [25]. These examples demonstrate how contour map interpretation directly translates to molecular design decisions in cancer drug optimization.

Following compound design, virtual screening filters assess drug-likeness and synthetic feasibility. Standard approaches include Lipinski's Rule of Five for oral bioavailability, ADMET risk assessment for pharmacokinetic properties, and synthetic accessibility scoring [29]. Molecular docking further validates designed compounds by examining binding modes and interactions with key residues in the target protein's active site [23]. For promising candidates, molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns) with MM-PBSA calculations provide additional confirmation of binding stability and affinity [25].

Research Reagent Solutions and Technical Specifications

Successful implementation of 3D-QSAR in cancer research requires specific software tools and computational resources. The following table details essential research reagents and their applications in typical workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Category | Specific Tools | Function in 3D-QSAR Workflow | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Suites | SYBYL-X, Forge, Spartan | Structure building, energy minimization, molecular alignment | SYBYL-X used for CoMFA/CoMSIA on quinazoline derivatives [23] |

| Quantum Chemical Software | Gaussian, DFT packages | Geometry optimization, charge calculation | DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* for quinazoline energy minimization [23] |

| Docking Software | Molegro Virtual Docker, AutoDock, GOLD | Binding pose generation, docking-guided alignment | MVD used for EGFR inhibitor docking studies [23] |

| ADMET Prediction | SwissADME, pkCSM | Drug-likeness screening, pharmacokinetic profiling | SwissADME used for triazolopyrazine derivative screening [25] |

| Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER | Molecular dynamics simulations, binding free energy calculations | MM-PBSA calculations for VEGFR-2 inhibitors [25] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the standard integrated protocol for 3D-QSAR-based cancer compound optimization, incorporating key decision points and validation steps:

Diagram 1: 3D-QSAR Cancer Compound Optimization Workflow

CoMFA, CoMSIA, and SOMFA represent powerful complementary techniques in the cancer drug discovery arsenal, each offering unique advantages for different optimization scenarios. CoMFA provides robust, interpretable models based on fundamental steric and electrostatic principles; CoMSIA delivers nuanced insights through multiple interaction fields; while SOMFA offers simplicity and directness in model interpretation. The integration of these 3D-QSAR approaches with molecular docking, ADMET prediction, and molecular dynamics simulations creates a comprehensive framework for rational drug design in oncology. As demonstrated through numerous cancer-focused applications, these methodologies successfully guide the transformation of lead compounds into optimized drug candidates with enhanced potency and improved pharmacological profiles. The continued refinement of 3D-QSAR protocols, coupled with advances in computational power and algorithmic sophistication, promises to further accelerate cancer drug discovery in the coming years.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Oncology

Within the framework of cancer compound optimization, Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) analysis serves as a pivotal computational method for correlating the three-dimensional spatial and electronic properties of molecules with their biological activity against cancer targets. This protocol details a comprehensive, step-by-step workflow for constructing robust 3D-QSAR models, from the initial critical stage of data set curation to the final model building and validation. The integration of this workflow into cancer drug discovery pipelines enables researchers to predict the activity of novel compounds, understand key interaction features, and rationally optimize lead compounds for enhanced potency, thereby accelerating the development of new oncology therapeutics [31] [32].

Protocol: Data Set Curation and Preparation

The foundation of a predictive and reliable 3D-QSAR model lies in the quality and consistency of the underlying data set. This initial phase demands meticulous attention to detail.

Data Acquisition and Initial Processing

- Source Selection: Begin by acquiring biological activity data (e.g., ICâ‚…â‚€, Ki) from publicly available databases like ChEMBL or through in-house experimental assays [33] [34]. For cancer research, ensure data is relevant to the target of interest (e.g., MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cell line inhibition [31]).

- Data Curation: Implement an automated curation workflow to standardize the data. This includes:

- Removing records with missing activity values.

- Handling duplicates by retaining the most reliable measurement or averaging replicates.

- Filtering out salts and standardizing tautomeric forms to ensure a consistent set of molecular structures [34].

- Modelability Assessment: Before proceeding, estimate the data set's "modelability" (MODI index). This step evaluates the feasibility of the data set to produce a predictive model, preventing unnecessary resource expenditure on non-modelable data [34].

Molecular System Preparation

- 3D Conformer Generation: Convert 2D structures (e.g., SMILES) into 3D conformations. This can be achieved using tools available in software packages like Orion, PharmQSAR, or Open Babel [35] [32] [33].

- Geometry Optimization and Charge Assignment: Minimize the energy of the generated 3D structures. Subsequently, assign partial atomic charges using appropriate methods such as AM1-BCC, Gasteiger, or semi-empirical Quantum-Mechanics (QM) approaches, which are critical for accurately describing electrostatic interactions [35] [32].

- Molecular Alignment: This is a critical step for 3D-QSAR. Align all molecules to a common reference frame based on:

- A shared, rigid scaffold (pharmacophore-based alignment).

- The predicted binding pose from molecular docking into a protein target.

- Field-based alignment using steric and electrostatic potentials [32].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Data Curation and Molecular Preparation

| Step | Key Parameter | Description/Recommended Value |

|---|---|---|

| Data Curation | Activity Data Type | ICâ‚…â‚€, Ki, log-based potency values [35] |

| Duplicate Handling | Retain consensus value or most reliable measurement [34] | |

| Conformer Generation | Method | Posit, FlexiROCS, or force-field based minimization [35] [32] |

| Charge Assignment | Charge Method | AM1-BCC, Gasteiger, or semi-empirical QM [35] [32] |

| Molecular Alignment | Alignment Rule | Pharmacophore, docking-based, or field-based [32] |

| Minimum Posit Probability (if applicable) | ≥ 0.5 for docking-derived poses [35] |

Protocol: 3D-QSAR Model Building

With a curated and aligned set of molecules, the process moves to calculating molecular descriptors and constructing the computational model.

Descriptor Calculation and Field Analysis

Calculate 3D molecular descriptors that encapsulate the steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic properties of the aligned molecules. Modern approaches extend beyond traditional CoMFA/CoMSIA fields to include more advanced descriptors:

- Interaction Fields: Calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) potential fields around each molecule using a probe atom [32].

- Quantum Chemical Descriptors: For enhanced accuracy, compute 3D electron density features via Density Functional Theory (DFT), which can be encoded into multi-scale descriptors like radial distribution functions and spherical harmonic expansions for a richer representation of electronic structure [33].

- Shape and Electrostatic Similarity: Utilize industry-leading tools like ROCS and EON for shape-based and electrostatic similarity descriptors, which serve as powerful inputs for machine learning models [35] [6].

Data Set Splitting and Model Training

- Training and Validation Sets: Split the curated data set into training and test sets. Common methods include:

- Model Construction: Apply machine learning algorithms to the training set to build a relationship between the 3D descriptors and biological activity. Common methods include:

- k-Partial Least Squares (k-PLS): Used for models like ROCS-kPLS and EON-kPLS, where the optimal number of features is determined via cross-validation [35].

- Gaussian Process Regression (GPR): Used for ROCS-GPR and EON-GPR models, which provides a measure of prediction confidence [35].

- Consensus (COMBO) Model: A robust approach where the final prediction is a weighted average of multiple individual models (e.g., 2D-GPR, ROCS-kPLS, ROCS-GPR, EON-kPLS, EON-GPR), with weights based on their individual prediction confidences [35].

Model Validation and Interpretation

- Statistical Validation: Evaluate model performance using multiple statistical metrics from cross-validation and external validation. Key metrics include:

- Pearson’s correlation coefficient squared (r²)

- Cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²)

- Median absolute error (MAE)

- Coefficient of Determination (COD) [35]

- Domain of Applicability: Analyze the model's applicability domain to ensure subsequent predictions are made for compounds within the chemical space of the training set [33].

- Model Interpretation: Visualize the 3D-QSAR contour maps (e.g., using PyMOL). These maps highlight regions in 3D space where specific chemical features (e.g., electron-donating groups, bulky substituents) favorably or unfavorably influence biological activity, providing direct, actionable insights for lead optimization [6] [32].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the entire process from data curation to a validated, interpretable model.

Diagram 1: A complete 3D-QSAR workflow for cancer compound optimization, from data sourcing to a validated predictive model.

Table 2: Core Statistical Metrics for 3D-QSAR Model Validation [35]

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| R² | Pearson’s correlation coefficient squared for training set. | Goodness-of-fit of the model. |

| q² | Cross-validated correlation coefficient (from LOO or other). | Indicator of model predictive ability. |

| COD | Coefficient of Determination from external validation. | Can be negative if worse than a baseline model predicting the average. |

| Median Absolute Error (MAE) | Median of absolute prediction errors. | Robust measure of prediction error magnitude. |

| Fraction Accurate vs. Confidence | Plot of accuracy versus model-estimated confidence. | Assesses correlation between confidence and accuracy. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Successful implementation of the 3D-QSAR workflow relies on a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR Analysis

| Tool/Resource Name | Type/Function | Relevance in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Orion 3D-QSAR Floes [35] | Automated Workflow Modules | Provides "3D QSAR Model: Builder" and "Predictor" floes for end-to-end model building and prediction using consensus models (ROCS-GPR, EON-kPLS, etc.). |

| PharmQSAR [32] | 3D QSAR Software Package | Builds statistical models (CoMFA, CoMSIA, HyPhar) using high-quality 3D molecular fields derived from semi-empirical QM calculations. |

| KNIME with Cheminformatics Extensions [36] [34] | Automated Workflow Platform | Enables the creation of fully automated, customizable workflows for data curation, descriptor calculation, machine learning, and validation. |

| 3D-QSAR.com [20] | Web Application Platform | Offers user-friendly, web-based tools for developing both ligand-based and structure-based 3D QSAR models. |

| Open Babel, RDKit [33] [34] | Cheminformatics Toolkits | Used for fundamental tasks like file format conversion, 2D to 3D structure conversion, and descriptor calculation within automated pipelines. |

| GROMACS [31] | Molecular Dynamics Simulation Software | Used for simulating the stability of protein-ligand complexes, which can inform the selection of biologically relevant conformers for 3D-QSAR. |

| Multiwfn [33] | Wavefunction Analyzer | Aids in calculating advanced quantum chemical descriptors, such as 3D electron density features, for enhanced model accuracy. |

| RN941 | RN941 (N-Phenylmaleimide) | High-purity RN941 (N-Phenylmaleimide), CAS 941-69-5. A key building block for polymer and bioconjugation research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| MMGP1 | MMGP1 Antifungal Peptide | MMGP1 is a marine metagenome-derived cell-penetrating peptide with potent activity againstCandida albicans. It is for Research Use Only. |

Application Note: A Case Study in Breast Cancer

A recent study on breast cancer treatment exemplifies this workflow. Researchers identified the adenosine A1 receptor as a key target via bioinformatics. After curating a set of active compounds, they performed molecular docking and dynamics simulations to study binding stability. A pharmacophore model was then constructed based on this binding information, which guided the virtual screening and rational design of a novel compound, Molecule 10. Subsequent synthesis and in vitro evaluation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells revealed potent antitumor activity (IC₅₀ = 0.032 µM), significantly outperforming the positive control 5-FU. This success underscores how a computational 3D-QSAR-driven workflow can efficiently deliver highly active therapeutic candidates [31].

The human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is a major oncogenic driver in approximately 20-30% of breast cancers and other carcinomas, where its overexpression portends poor clinical outcome [37] [38]. This receptor tyrosine kinase, a member of the ErbB family, exists as an orphan receptor with no known ligand but serves as the preferred dimerization partner for other HER family members [37] [39]. When dimerized, particularly with HER3, it activates potent downstream signaling through the MAPK and PI3K-Akt pathways, promoting uncontrolled cell growth and survival [38] [39]. Targeting the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain of HER2 has emerged as a validated therapeutic strategy, complementing antibody-based approaches that target the extracellular domain [40] [38].

Within cancer drug discovery, Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) techniques represent powerful computational approaches for optimizing lead compounds when the correlation between molecular structure and biological activity must be understood in three-dimensional space [41]. Unlike classical 2D-QSAR that uses molecular descriptors independent of x,y,z coordinates (e.g., logP, molar refractivity), 3D-QSAR employs a set of values measured at different locations in the space around molecules [41] [42]. Self-Organizing Molecular Field Analysis (SOMFA) is one such grid-based, alignment-dependent 3D-QSAR method that simplifies the relationship between molecular properties and biological activity by using molecular shape and electrostatic potential to construct predictive models [43] [37]. This case study details the application of SOMFA to design novel quinazoline-based HER2 kinase inhibitors, demonstrating its utility within a broader thesis on structure-based drug design for oncology targets.

HER2 Signaling Pathway and Therapeutic Significance

The HER2 signaling axis represents a critical vulnerability in HER2-positive cancers. The following diagram illustrates the key components and interactions in the HER2 signaling pathway that make it a compelling drug target.

Diagram 1: HER2-HER3 signaling pathway driving oncogenesis. The pathway initiates when neuregulin (NRG) binds HER3, promoting heterodimerization with HER2. This triggers autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues, creating docking sites for adaptor proteins that activate downstream MAPK (proliferation) and PI3K-Akt (survival) signaling cascades. HER2's role as the preferred dimerization partner, despite having no known ligand, makes it a pivotal therapeutic target in HER2-positive cancers [37] [38] [39].

While monoclonal antibodies like trastuzumab target the extracellular domain of HER2, small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) offer a complementary approach by competing with ATP for binding at the intracellular catalytic kinase domain [38]. This blocks HER2 autophosphorylation and subsequent activation of downstream proliferative and survival signals. However, the high degree of structural conservation among kinase domains presents a challenge for achieving specificity, and drug resistance often emerges through mutations or activation of alternative signaling pathways [37] [40]. These limitations underscore the need for sophisticated structure-based design approaches like SOMFA to develop more potent and specific HER2 inhibitors.

SOMFA Methodology in 3D-QSAR

SOMFA operates on the fundamental principle that differences in biological activity between compounds can be correlated with differences in their molecular interaction fields - primarily steric (shape) and electrostatic (charge distribution) properties [43] [37]. The method is alignment-dependent, meaning that the accuracy of the model heavily relies on the correct spatial superposition of the molecules being studied, typically based on a common scaffold or pharmacophoric features [37] [41].

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the SOMFA workflow as applied to HER2 inhibitor design.

Diagram 2: SOMFA workflow for HER2 inhibitor optimization. The process begins with curating a congeneric series of compounds with known biological activities, followed by generating their bioactive conformations through molecular docking. After spatial alignment, steric and electrostatic fields are calculated at grid points surrounding the molecules. Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis then correlates field values with biological activity to generate a predictive model, validated through statistical measures, which guides the design of novel inhibitors with enhanced potency [43] [37].

In SOMFA, the molecular shape and electrostatic potential are calculated at numerous points within a 3D grid encompassing the aligned molecules. The steric field describes van der Waals interactions (both attractive and repulsive), while the electrostatic field captures Coulombic interactions between the molecule and a probe [41]. These fields are then correlated with biological activity using Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis, a statistical technique particularly suited for datasets with many collinear variables [43] [37]. The resulting model generates contour maps that visually identify regions where specific molecular properties (bulk, positive/negative charge) would enhance or diminish biological activity, providing medicinal chemists with clear design guidance [43] [37] [41].

Case Study: SOMFA Application to Quinazoline-Based HER2 Inhibitors

Dataset and Molecular Alignment

The foundational study applied SOMFA to a series of 24 quinazoline derivatives reported as multi-acting inhibitors targeting histone deacetylase (HDAC), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and HER2 [43] [37]. The biological activity data consisted of ICâ‚…â‚€ values measured against the HER2 kinase domain using the HTScan HER2/ErbB2 Kinase Assay Kit, which were converted to pICâ‚…â‚€ (-logICâ‚…â‚€) for QSAR analysis [37]. This dataset provided an ideal structural diversity and activity range for robust model development.

Molecular alignment, a critical step in SOMFA, was performed using an atom-based approach with compound 1 as the reference structure. The researchers investigated three independent conformational sets generated by different docking tools: AutoDock 4.2, HyperChem 8.0, and AutoDock Vina [37]. This comparative approach ensured that the resulting models were not biased by the selection of a single conformational generation method. The alignment aimed to minimize the root-mean-square (RMS) differences in the fitting of selected atoms relative to the reference molecule, ensuring consistent spatial orientation of the common quinazoline scaffold while allowing variation in substituent positions.

SOMFA Model Development and Statistical Validation

For each conformational set (AutoDock4, HyperChem, and AutoDock Vina), independent SOMFA models were generated and evaluated using PLS analysis. The models were assessed using several statistical measures, with cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) indicating predictive ability, non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (r²) measuring goodness-of-fit, and F-test values reflecting overall statistical significance [43] [37].

Table 1: Statistical Parameters of Generated SOMFA Models for HER2 Inhibition

| Conformation Source | Cross-validated q² | Non-cross-validated r² | F-test Value | Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | 0.767 | 0.815 | 97.22 | Not specified |

| AutoDock4 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not specified |

| HyperChem | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not specified |

The model derived from AutoDock Vina-generated conformations demonstrated superior statistical quality with a cross-validated q² of 0.767, non-cross-validated r² of 0.815, and F-test value of 97.22, indicating a highly predictive and statistically significant model [43] [37]. The reasonable difference between q² and r² values suggests the model was not overfitted and possessed genuine predictive capability for novel quinazoline derivatives.

Key Structural Insights from SOMFA Contour Maps

Analysis of the SOMFA contour maps provided crucial insights into the structural requirements for potent HER2 inhibition:

- Steric Field Contours: Identified specific regions where bulky substituents either enhanced or diminished activity, guiding optimal placement of aromatic rings and alkyl chains.

- Electrostatic Field Contours: Revealed areas where positive or negative charge characteristics correlated with improved potency, informing the selection of electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituents.

These contour maps effectively visualized the architecture of the HER2 kinase active site, highlighting favorable and unfavorable interaction regions without requiring explicit protein structural information. The models suggested specific molecular modifications to the quinazoline core structure that would enhance HER2 inhibitory potency while potentially maintaining activity against other targets (HDAC, EGFR) for multi-acting therapeutic effects.

Experimental Protocols

HER2 Kinase Inhibition Assay Protocol

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the inhibitory potency (ICâ‚…â‚€) of quinazoline derivatives against the HER2 kinase domain.

Materials:

- HTScan HER2/ErbB2 Kinase Assay Kit (Cell Signaling Technology)

- Test compounds (quinazoline derivatives in DMSO stock solutions)

- Active HER2/ErbB2 kinase (GST fusion protein)

- Biotinylated peptide substrate

- Phospho-tyrosine antibody for detection

- ATP solution

- Reaction buffer

- Stop solution

- Microplate reader capable of fluorescence detection

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a 96-well plate, prepare reaction mixtures containing HER2 kinase, biotinylated peptide substrate, and varying concentrations of test compounds in reaction buffer.

- Reaction Initiation: Start the kinase reaction by adding ATP to each well.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction plate at 30°C for 1 hour.

- Reaction Termination: Add stop solution to each well to terminate the kinase reaction.

- Detection: Transfer reaction mixtures to streptavidin-coated plates and detect phosphorylated substrate using phospho-tyrosine antibody and fluorescent immuno-detection.

- Data Analysis: Calculate percentage inhibition relative to controls (no inhibitor) and determine ICâ‚…â‚€ values using non-linear regression analysis.

- Data Conversion: Convert ICâ‚…â‚€ values to pICâ‚…â‚€ (-logICâ‚…â‚€) for QSAR analysis.