3D-QSAR in Anticancer Drug Design: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive overview of 3D-Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) methodologies and their pivotal role in modern anticancer drug discovery.

3D-QSAR in Anticancer Drug Design: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of 3D-Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) methodologies and their pivotal role in modern anticancer drug discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of 3D-QSAR, detailing advanced methodological approaches like CoMFA and CoMSIA. The content addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, presents rigorous validation protocols, and examines the synergistic integration of 3D-QSAR with molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and ADMET profiling. Through illustrative case studies targeting specific cancer pathways and proteins, this guide serves as a practical resource for leveraging 3D-QSAR to efficiently design and optimize novel, potent anticancer agents.

Understanding 3D-QSAR: The Cornerstone of Modern Cancer Drug Discovery

The transition from two-dimensional to three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in computational drug design. While traditional 2D-QSAR models correlate biological activity with physicochemical parameters and structural features encoded in molecular graphs, they fundamentally lack the spatial resolution to account for the three-dimensional nature of molecular recognition and binding [1] [2]. This limitation became increasingly apparent as medicinal chemists sought to optimize complex drug-target interactions, particularly in anticancer drug development where precise steric and electrostatic complementarity often dictates therapeutic efficacy.

The emergence of 3D-QSAR methodologies in the 1980s-1990s marked a revolutionary advance by incorporating the essential third dimension of molecular structure [1]. These approaches recognize that biological activity depends not merely on a molecule's constituent atoms and bonds, but on its specific three-dimensional conformation and the spatial distribution of its molecular fields [3]. By quantifying and correlating these 3D properties with biological responses, 3D-QSAR enables researchers to visualize and interpret the structural determinants of biological activity in a spatially meaningful context, providing powerful insights for rational drug design in oncology and beyond [4].

This evolution from 2D to 3D-QSAR has proven particularly valuable in anticancer drug discovery, where researchers must often optimize compounds against complex molecular targets such as kinases, nuclear receptors, and other signaling proteins [5] [6]. The three-dimensional steric and electrostatic features that govern these interactions can now be systematically mapped and quantified, accelerating the development of targeted therapies with improved potency and selectivity.

Fundamental Principles: From 2D Descriptors to 3D Molecular Fields

The 2D-QSAR Foundation

Traditional 2D-QSAR establishes mathematical relationships between biological activity and molecular descriptors derived from two-dimensional structural representations [4]. These models are built upon several categories of numerical descriptors:

- Physicochemical descriptors: Including lipophilicity (LogP), molecular weight, polar surface area, and hydrogen bonding capacity, which influence absorption, distribution, and binding [7].

- Topological descriptors: Encoding molecular connectivity patterns, branching, and atomic environments through indices such as Wiener, Randić, and Kier-Hall indices [8].

- Electronic descriptors: Characterizing charge distribution, polarizability, and reactivity through Hammett constants, dipole moments, and frontier orbital energies [7].

The fundamental 2D-QSAR equation takes the general form: Activity = f(physicochemical properties and/or structural properties) + error [3]. These linear free-energy relationship (LFER) models, pioneered by Hansch and Fujita, successfully predict activity for congeneric series but are limited by their inability to account for stereochemistry and three-dimensional molecular shape [2] [4].

The 3D-QSAR Advancement

3D-QSAR methodologies address the critical limitations of 2D approaches by incorporating the spatial characteristics of molecules [1]. The core principle is that biological recognition depends on the complementary fit between a molecule and its binding site in three-dimensional space, mediated by steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding interactions [3] [6].

The key conceptual advances of 3D-QSAR include:

- Molecular alignment: Compounds are superimposed in 3D space based on their putative bioactive conformations, establishing a common reference frame for comparison [5] [6].

- Field analysis: Molecular interaction fields are calculated at regularly spaced grid points surrounding the aligned molecules, quantifying steric, electrostatic, and other physicochemical properties [3].

- Spatial correlation: These field values are correlated with biological activity using multivariate statistical methods, typically Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression [5] [6].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of 2D vs. 3D QSAR Approaches

| Feature | 2D-QSAR | 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representation | Constitutional formulas, connectivity | Three-dimensional structures, conformations |

| Descriptors | Count-based, topological indices | Spatial fields (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic) |

| Alignment Requirement | Not required | Critical step based on pharmacophore or docking |

| Handling of Stereoisomers | Limited discrimination | Explicitly accounts for chirality and conformation |

| Visualization | Coefficient plots, correlation graphs | 3D contour maps showing favorable/unfavorable regions |

| Primary Applications | Property prediction, toxicity assessment | Lead optimization, structure-based design |

Methodological Framework: Core 3D-QSAR Techniques

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA)

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), introduced by Cramer et al. in 1988, represents the pioneering 3D-QSAR methodology [3]. The CoMFA approach operates on the fundamental principle that biological differences between molecules stem from variations in their non-covalent interaction fields, particularly steric and electrostatic properties [1].

The standard CoMFA protocol comprises several critical steps:

- Molecular Modeling and Conformational Analysis: Generate low-energy 3D structures for each compound, typically through molecular mechanics or quantum chemical calculations.

- Molecular Alignment: Superimpose all molecules according to a defined pharmacophore or based on their alignment to a common reference structure. This represents the most critical step, as the quality of alignment directly determines model significance [6].

- Interaction Field Calculation: Place each aligned molecule within a 3D grid and calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) potentials at each grid point using a probe atom [3].

- Statistical Correlation: Apply Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate the field values with biological activity, generating a predictive model [5].

- Visualization: Interpret results through 3D coefficient contour maps that highlight regions where specific molecular properties enhance or diminish biological activity [6].

CoMFA has demonstrated particular utility in kinase inhibitor development, as evidenced by studies on Bcr-Abl inhibitors for chronic myeloid leukemia, where models achieved strong predictive power (q² > 0.5) guiding the design of purine-based therapeutics [5].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA)

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extends beyond CoMFA by incorporating additional molecular fields and employing a Gaussian function to calculate similarity indices, thereby addressing several CoMFA limitations [9]. Unlike CoMFA's Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials, which can produce extreme values near molecular surfaces, CoMSIA's Gaussian function provides smoother sampling of molecular similarities [9].

CoMSIA typically evaluates five distinct similarity fields:

- Steric (shape and size)

- Electrostatic (charge distribution)

- Hydrophobic (lipophilicity)

- Hydrogen bond donor

- Hydrogen bond acceptor

This comprehensive field assessment provides a more holistic view of molecular interactions relevant to biological activity. A recent application to monoamine oxidase B inhibitors demonstrated the power of this approach, with the resulting CoMSIA model exhibiting excellent statistical characteristics (r² = 0.915, q² = 0.569) [9]. The inclusion of hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding fields proved particularly valuable for optimizing neuroprotective agents targeting neurodegenerative diseases.

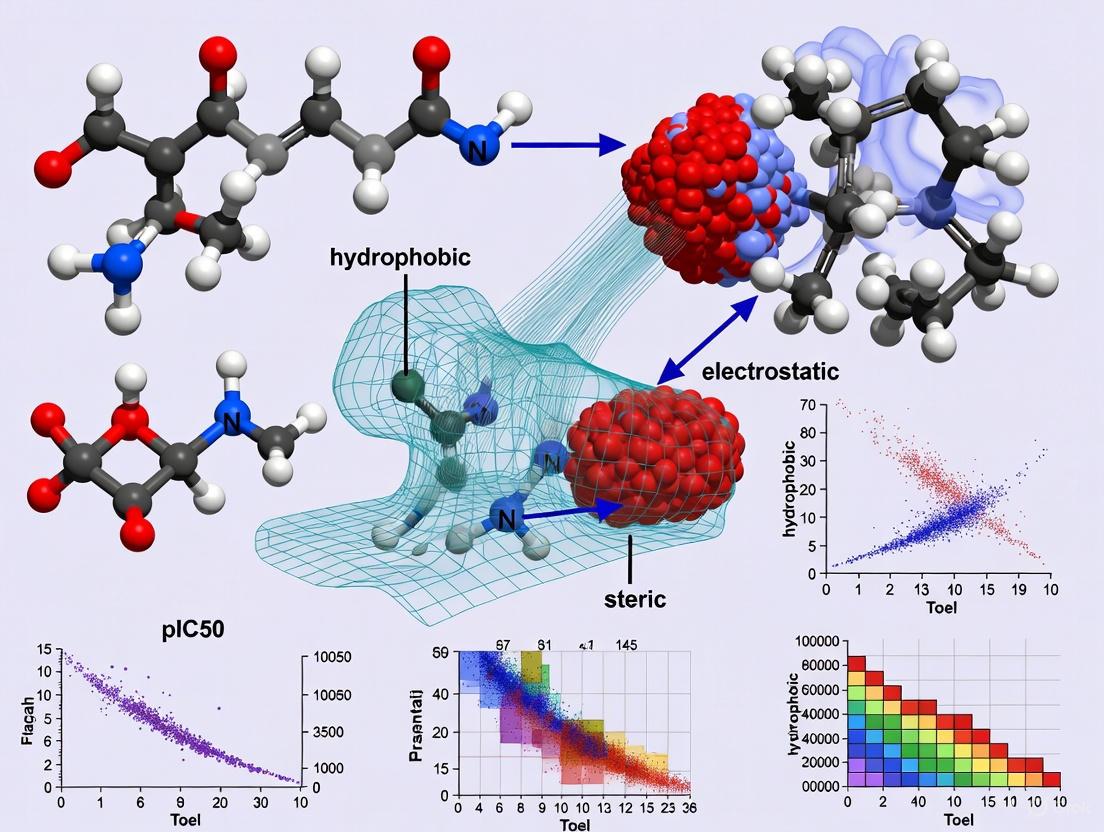

Diagram 1: Standard 3D-QSAR workflow encompassing conformation generation, molecular alignment, field calculation, and model validation.

Experimental Protocols: Implementing 3D-QSAR in Anticancer Drug Design

Data Set Preparation and Molecular Modeling

The foundation of any robust 3D-QSAR model lies in careful data set curation and preparation. For anticancer applications, this typically involves:

Compound Selection and Activity Data

- Compile 20-100 congeneric compounds with consistent biological activity data (e.g., ICâ‚…â‚€, GIâ‚…â‚€) from published literature or experimental results [6].

- Ensure adequate structural diversity while maintaining a common scaffold to explore structure-activity relationships.

- Convert activity values to pICâ‚…â‚€ or pGIâ‚…â‚€ using the formula: pICâ‚…â‚€ = -log(ICâ‚…â‚€) for regression analysis [6].

- Divide compounds into training (70-80%) and test sets (20-30%) using activity-stratified selection to ensure representative distribution [6].

Structure Preparation and Optimization

- Generate initial 3D structures using molecular modeling software (ChemBio3D, Sybyl) [6].

- Perform geometry optimization using molecular mechanics (MMFF94, AMBER) or semi-empirical methods (AM1, PM3) to obtain low-energy conformations [6].

- For maslinic acid analogs studied against breast cancer MCF-7 cells, researchers minimized all conformers using the XED force field with a gradient cut-off of 0.1 [6].

Molecular Alignment Strategies

Proper molecular alignment is arguably the most critical step in 3D-QSAR model development. Common approaches include:

Pharmacophore-Based Alignment

- Identify common structural features presumed essential for biological activity using FieldTemplater or similar software [6].

- For triterpene maslinic acid analogs, a field-based template was derived from the most active compounds (M-159, M-254, M-286, M-543, M-659) to represent the putative bioactive conformation [6].

- Align all compounds to this pharmacophore template based on field and shape similarity.

Structure-Based Alignment

- When target protein structure is available, dock compounds into the binding site and use the docking poses for alignment.

- For Bcr-Abl inhibitors, molecular docking was performed against the ABL kinase domain to generate consistent binding modes for CoMFA analysis [5].

RMS-Based Alignment

- Superimpose structures by minimizing root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of common atom positions, typically applied to rigid analogs.

Model Validation and Quality Assessment

Rigorous validation is essential to ensure model reliability and predictive power:

Internal Validation

- Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation: Iteratively remove one compound, rebuild model, and predict its activity. Calculate cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) - values >0.5 indicate good internal predictability [6].

- Leave-Multiple-Out Cross-Validation: Remove multiple compounds (e.g., 20%) repeatedly to assess model stability.

External Validation

- Predict activity of test set compounds not included in model building.

- Calculate predictive r² (r²pred) between predicted and experimental activities - values >0.6 indicate good external predictability.

Statistical Parameters

- Non-cross-validated r²: >0.8 indicates good model fit [9].

- Standard Error of Estimate (SEE): Lower values preferred.

- F-value: Higher values indicate statistical significance.

The CoMSIA model for MAO-B inhibitors demonstrated excellent statistics with q²=0.569, r²=0.915, SEE=0.109, and F-value=52.714 [9]. Similarly, the 3D-QSAR model for maslinic acid analogs showed strong performance with r²=0.92 and q²=0.75 [6].

Table 2: Statistical Parameters for 3D-QSAR Model Validation

| Parameter | Symbol | Acceptable Range | Excellent Performance | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOO Cross-validated Correlation Coefficient | q² | >0.5 | >0.7 | Internal predictive ability |

| Non-cross-validated Correlation Coefficient | r² | >0.8 | >0.9 | Goodness of fit for training set |

| Standard Error of Estimate | SEE | Small value | <0.1 | Precision of model predictions |

| F-value | F | Higher value | >30 | Overall statistical significance |

| Predictive r² for Test Set | r²pred | >0.6 | >0.8 | External predictive ability |

| Number of Components | ONC | Optimal value | Avoid overfitting | Model complexity |

Research Applications: 3D-QSAR in Anticancer Drug Discovery

Bcr-Abl Inhibitors for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) treatment has been revolutionized by Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors, but drug resistance remains a significant challenge, particularly with the T315I "gatekeeper" mutation [5]. 3D-QSAR has played a crucial role in developing inhibitors effective against both wild-type and mutant forms.

In a recent study, researchers developed CoMFA and CoMSIA models for 58 purine-based Bcr-Abl inhibitors to guide the design of novel compounds overcoming resistance [5]. The resulting models identified critical steric and electrostatic requirements for potency, leading to designed compounds 7a and 7c with IC₅₀ values of 0.13 and 0.19 μM, respectively - superior to imatinib (IC₅₀ = 0.33 μM) [5]. Importantly, compounds 7e and 7f showed significant activity against T315I mutant cells (GI₅₀ = 13.80 and 15.43 μM) where imatinib was ineffective (GI₅₀ > 20 μM) [5].

The 3D contour maps revealed that:

- Sterically favorable regions near specific substituents accommodate mutation-induced structural changes.

- Electron-withdrawing groups at critical positions enhance interactions with the ATP-binding site.

- Hydrophobic substituents of optimal size improve affinity while maintaining selectivity.

Maslinic Acid Analogs for Breast Cancer Therapy

Maslinic acid, a natural triterpenoid, shows promising anticancer activity but requires optimization for therapeutic application. A comprehensive 3D-QSAR study on analogs tested against MCF-7 breast cancer cells demonstrated the power of field-based approaches for natural product optimization [6].

The derived model (r²=0.92, q²=0.75) identified key structural features controlling activity:

- Positive electrostatic potential regions where electron-withdrawing groups enhance activity.

- Bulky substituents in specific areas create favorable steric interactions.

- Hydrophobic groups in defined regions improve membrane permeability and target binding.

Virtual screening of the ZINC database using the pharmacophore model identified 593 initial hits, which were filtered to 39 top candidates using:

- Lipinski's Rule of Five for oral bioavailability assessment.

- ADMET risk assessment for drug-like properties.

- Synthetic accessibility evaluation [6].

Compound P-902 emerged as the most promising candidate, showing strong predicted affinity for multiple targets including AKR1B10, NR3C1, PTGS2, and HER2 through docking studies [6].

Diagram 2: Application of 3D-QSAR in addressing Bcr-Abl inhibitor resistance in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML).

Table 3: Essential Software and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR Research

| Tool Category | Representative Software | Primary Function | Application in Anticancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | ChemBio3D, Sybyl-X | 3D structure generation, conformational analysis, geometry optimization | Preparation of cancer therapeutic candidates like kinase inhibitors [6] |

| Force Fields | XED, MMFF94, AMBER | Calculation of molecular energies, interaction potentials | Determination of bioactive conformations for alignment [6] |

| Field Calculation | Forge, Open3DQSAR | Computation of steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic fields | Generation of CoMFA/CoMSIA interaction fields for QSAR modeling [6] |

| Statistical Analysis | SIMPLS, R/Python libraries | Partial Least Squares regression, model validation | Correlation of molecular fields with biological activity [6] |

| Visualization | PyMOL, Discovery Studio | 3D contour map visualization, structure-activity interpretation | Mapping favorable/unfavorable regions for compound optimization [5] [6] |

| Docking & Scoring | AutoDock, GOLD, Glide | Protein-ligand docking, binding pose prediction | Structure-based alignment, binding mode analysis for molecular targets [5] |

The evolution from 2D to 3D-QSAR represents a transformative advancement in computational drug design, particularly for complex challenges in anticancer therapy development. By incorporating the essential third dimension of molecular structure, these methodologies enable researchers to visualize and quantify the spatial features governing biological activity, providing powerful insights for rational compound optimization.

The continued development of 3D-QSAR approaches, including the integration with machine learning algorithms, molecular dynamics simulations, and structural biology data, promises to further enhance their predictive power and applicability [4]. As these methods become more sophisticated and accessible, they will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel anticancer therapeutics, ultimately contributing to more effective and personalized cancer treatments.

For drug development professionals, mastery of 3D-QSAR techniques now represents an essential skill set, enabling more efficient navigation of complex structure-activity relationships and more informed decision-making throughout the drug discovery pipeline. The evolutionary leap from 2D to 3D-QSAR has firmly established spatial molecular design as a cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry, particularly in the ongoing battle against cancer.

Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling represents a pivotal computational approach in modern anticancer drug design. By quantifying how the three-dimensional molecular fields and steric/electronic descriptors of compounds correlate with their biological activity, 3D-QSAR enables the prediction of anticancer efficacy and the rational optimization of lead compounds. This technical guide delves into the core principles of molecular field analysis and 3D descriptor utilization, detailing the experimental protocols for model development and validation. Framed within the context of anticancer drug discovery, this review provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for applying these computational techniques to advance the development of novel oncotherapeutic agents.

The global burden of cancer, characterized by uncontrolled cell proliferation, necessitates the continuous discovery of novel therapeutic agents [10]. In anticancer research, microtubules, composed of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers, represent a critical target for antitumor therapy, as impairing their dynamic equilibrium leads to mitotic arrest and apoptosis [10]. However, the traditional process of drug discovery is often hampered by time-consuming and expensive experimental evaluations, compounded by ethical limitations in animal studies [10].

3D-QSAR methodologies have emerged as powerful in silico tools that significantly reduce the time and cost of drug development by establishing relationships between the three-dimensional structural properties of compounds and their biological activities [10] [6]. Unlike conventional 2D approaches, 3D-QSAR considers spatial molecular configurations, providing insights into the specific steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic requirements for biological activity. This is particularly valuable in anticancer research for understanding tubulin inhibition and other mechanisms targeting uncontrolled cell proliferation [10].

The fundamental premise of 3D-QSAR is that biological activity can be correlated with interactive molecular field values calculated at numerous grid points surrounding a set of aligned molecules [6]. This approach allows for the identification of critical structural regions that influence potency, thereby guiding the rational design of more effective analogs.

Core Principles: Molecular Fields and 3D Descriptors

Molecular Fields and Their Physicochemical Significance

Molecular fields are computational representations of the spatial distribution of physicochemical properties around a molecule. These fields are crucial for understanding how a ligand interacts with its biological target at the molecular level.

Key Molecular Field Types:

- Electrostatic Fields: Represent the distribution of positive and negative electrostatic potentials around the molecule, calculated using the eXtended Electron Distribution (XED) force field [6]. These fields identify regions where charge-charge interactions with the target protein may occur.

- Hydrophobic Fields: Represent the density function correlated with steric bulk and hydrophobicity [6]. These fields identify regions where hydrophobic interactions with the target protein may occur.

- Shape/van der Waals Fields: Represent the molecular shape and van der Waals interactions [6]. These fields identify regions where steric complementarity with the target protein is essential.

These field points provide a condensed representation of a compound's shape, electrostatics, and hydrophobicity, forming the basis for molecular alignment and similarity comparisons in 3D-QSAR modeling [6].

3D Molecular Descriptors

3D molecular descriptors are numerical quantities that capture the three-dimensional characteristics of molecules. In the context of 3D-QSAR, these descriptors are typically derived from the molecular fields and include:

- Field-Based Descriptors: Calculated at grid points surrounding aligned molecules, representing potential interaction energies with a hypothetical probe [6].

- Geometrical Descriptors: Encoding information about molecular size, shape, and symmetry.

- Surface-Based Descriptors: Describing properties of the molecular surface, such as charged surface areas.

The identification of relevant molecular descriptors is critical for improving the accuracy and reliability of QSAR models, as it enables better model interpretability and understanding of how structural changes affect biological endpoints [11].

Theoretical Foundation: The Relationship Between Structure and Activity

The foundational principle underlying 3D-QSAR is that differences in biological activity among compounds correlate with changes in their molecular field patterns. This relationship is quantified through statistical methods, primarily Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, which handles the high dimensionality and collinearity of field descriptor data [10] [6].

The molecular field similarity method assumes that compounds with similar field patterns will exhibit similar biological activities, as they likely interact with the target protein in analogous ways. This approach is particularly valuable when structural information about the target is unavailable, as it allows for the elucidation of structure-activity relationships directly from ligand properties [6].

Methodological Framework: Developing 3D-QSAR Models

Data Collection and Structure Preparation

The initial step in 3D-QSAR model development involves curating a dataset of compounds with reliably measured biological activities, typically expressed as ICâ‚…â‚€ or pICâ‚…â‚€ values. For anticancer applications, this may include cytotoxic quinolines as tubulin inhibitors or maslinic acid analogs tested against specific cancer cell lines like MCF-7 [10] [6].

Protocol:

- Data Compilation: Collect 2D chemical structures from literature or experimental data.

- 3D Conversion: Transform 2D structures into 3D models using molecular modeling software (e.g., ChemBio3D Ultra) [6].

- Energy Minimization: Optimize 3D structures using force fields (e.g., OPLS_2005, XED) to obtain low-energy conformations [10] [6].

- Activity Expression: Convert ICâ‚…â‚€ values to pICâ‚…â‚€ (pICâ‚…â‚€ = -logICâ‚…â‚€) for linear modeling [10].

Conformational Analysis and Pharmacophore Generation

As structural information for targets may be unavailable, determining the bioactive conformation is crucial. The FieldTemplater module in software like Forge uses field and shape information to develop a pharmacophore hypothesis representing the essential 3D features required for biological activity [6].

Protocol:

- Template Selection: Identify active compounds to serve as templates for hypothesis generation [6].

- Field Point Calculation: Generate field points (electrostatic, hydrophobic, shape) using the XED force field [6].

- Hypothesis Annotation: Annotate the derived hypothesis with calculated field points, creating a 3D field point pattern [6].

- Feature Identification: Define pharmacophore features such as hydrogen bond acceptors (A), donors (D), hydrophobic groups (H), and aromatic rings (R) [10].

Table 1: Common Pharmacophore Features in 3D-QSAR

| Feature | Symbol | Description | Role in Molecular Recognition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | A | Atom that can accept hydrogen bonds | Forms specific interactions with donor groups in target |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | D | Atom that can donate hydrogen bonds | Forms specific interactions with acceptor groups in target |

| Hydrophobic Group | H | Region of hydrophobic character | Drives interactions through desolvation effects |

| Aromatic Ring | R | Planar conjugated ring system | Enables π-π and cation-π interactions |

| Positively Charged Group | P | Region with positive charge | Facilitates electrostatic interactions |

| Negatively Charged Group | N | Region with negative charge | Facilitates electrostatic interactions |

Molecular Alignment and Descriptor Calculation

Molecular alignment is the most critical step in 3D-QSAR, as it determines the accuracy of subsequent field comparisons. Compounds are aligned based on their similarity to the pharmacophore template or through field-based fitting [6].

Protocol:

- Template Transfer: Transfer the pharmacophore template to alignment software (e.g., Forge) [6].

- Compound Alignment: Align training set compounds with the identified template using field and shape similarity metrics [6].

- Grid Generation: Surround the aligned molecules with a 3D grid with specified spacing (e.g., 1.0-2.0 Ã…) [6].

- Field Descriptor Calculation: Compute interaction energies at each grid point using appropriate probes [6].

Statistical Analysis and Model Validation

PLS regression is the standard statistical method for correlating field descriptors with biological activity due to its ability to handle numerous, collinear descriptors [10] [6].

Protocol:

- Data Splitting: Divide compounds into training and test sets using activity-stratified methods [6].

- PLS Regression: Apply the SIMPLS algorithm to develop the QSAR model with specified maximum components [6].

- Model Validation:

Table 2: Key Statistical Parameters for 3D-QSAR Model Validation

| Parameter | Symbol | Acceptable Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficient | R² | >0.7 | Goodness of fit for the training set |

| Cross-Validation Coefficient | Q² | >0.5 | Predictive ability of the model |

| F Value | F | Higher is better | Statistical significance of the model |

| Standard Deviation | SD | Lower is better | Precision of the model estimates |

| Pearson R | R | Close to 1 | Correlation between predicted and observed activities |

| Root Mean Square Error | RMSE | Lower is better | Average prediction error |

Case Studies in Anticancer Research

3D-QSAR of Cytotoxic Quinolines as Tubulin Inhibitors

A study developing 3D-QSAR for sixty-two cytotoxic quinolines as anticancer agents with tubulin inhibitory activity demonstrates the practical application of these methods [10].

Experimental Protocol:

- Dataset: 62 quinolines with cytotoxic activity against A2780 (human ovarian carcinoma) cell line [10].

- Ligand Preparation: 3D structures generated using Maestro builder panel and optimized with LigPrep module using OPLS_2005 force field [10].

- Pharmacophore Modeling: 279 hypotheses generated using Phase module; best model identified as AAARRR.1061 with three hydrogen bond acceptors and three aromatic rings [10].

- Model Statistics: High correlation coefficient (R² = 0.865), cross-validation coefficient (Q² = 0.718), and F value (72.3) [10].

- Validation: Y-Randomization test and ROC-AUC analysis confirmed model robustness [10].

- Application: Generated 3D contour maps revealed structure-activity relationship; virtual screening identified potential leads with high docking scores [10].

3D-QSAR of Maslinic Acid Analogs Against Breast Cancer

A study on maslinic acid analogs for anticancer activity against breast cancer cell line MCF-7 illustrates the use of field-based 3D-QSAR in natural product optimization [6].

Experimental Protocol:

- Dataset: 74 compounds of triterpene maslinic acid and its analogs with known ICâ‚…â‚€ values [6].

- Template Development: FieldTemplater module used with compounds M-159, M-254, M-286, M-543, and M-659 to determine bioactive conformation [6].

- Alignment and Modeling: Compounds aligned with pharmacophore template; field point-based descriptors used for 3D-QSAR model [6].

- Model Performance: Leave-one-out validated PLS regression model showed acceptable R² (0.92) and Q² (0.75) [6].

- Virtual Screening: ZINC database screened (593 compounds); 39 top hits selected after Lipinski's Rule of Five, ADMET risk, and synthetic accessibility filters [6].

- Target Identification: Docking screening performed against AKR1B10, NR3C1, PTGS2, and HER2 targets; compound P-902 identified as best hit [6].

Table 3: Comparison of 3D-QSAR Applications in Anticancer Research

| Parameter | Cytotoxic Quinolines Study [10] | Maslinic Acid Analogs Study [6] |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Target | Tubulin inhibition | Multiple targets (AKR1B10, NR3C1, PTGS2, HER2) |

| Cancer Type | Ovarian carcinoma (A2780 cell line) | Breast cancer (MCF-7 cell line) |

| Dataset Size | 62 compounds | 74 compounds |

| Best Pharmacophore | AAARRR.1061 | Field-based template from 5 compounds |

| Model Statistics | R² = 0.865, Q² = 0.718 | R² = 0.92, Q² = 0.75 |

| Validation Methods | Y-Randomization, ROC-AUC | LOO cross-validation, test set prediction |

| Key Structural Features | Three H-bond acceptors, three aromatic rings | Electrostatic, hydrophobic, and shape features |

Advanced Computational Approaches

Counter-Propagation Artificial Neural Networks (CPANN)

Counter-Propagation Artificial Neural Networks represent an advanced approach to QSAR modeling that can handle complex nonlinear relationships. The CPANN architecture consists of two layers: the Kohonen layer for unsupervised learning and grouping of similar molecules, and the Grossberg layer for supervised prediction of target properties [11].

A novel modification of CPANN dynamically adjusts molecular descriptor importance during model training, allowing different importance values for structurally different molecules. This increases adaptability to diverse compound sets and improves classification performance for endpoints like enzyme inhibition and hepatotoxicity [11].

Algorithm Implementation:

- Network Structure: Nx × Ny neurons with Ndesc weights on each neuron in Kohonen layer [11].

- Central Neuron Identification: Euclidean distance used to find most similar neuron to input molecule [11].

- Weight Correction: Neuron weights corrected using neighborhood function that decreases with topological distance from central neuron [11].

- Descriptor Importance Adjustment: Modified algorithm adjusts relative importance during training, resembling model weight correction in standard CPANN [11].

Activity-Atlas Modeling and 3D Visualization

Activity-Atlas models provide a qualitative, three-dimensional understanding of structure-activity relationships by combining multiple computed properties into comprehensive visualizations [6].

Key Components:

- Average of Actives: Reveals common structural and field features among active compounds [6].

- Activity Cliff Summary: Identifies regions where small structural changes cause significant activity differences [6].

- Regions Explored Analysis: Maps chemical space covered by the training set to identify unexplored regions [6].

These models help researchers visualize favorable and unfavorable regions for steric bulk, positive and negative electrostatics, and hydrophobicity, providing intuitive guidance for molecular design [6].

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR in Anticancer Research

| Tool/Software | Function | Application in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Schrödinger Suite (Phase, LigPrep) | Molecular modeling, pharmacophore generation, ligand preparation | 3D structure optimization, pharmacophore hypothesis generation [10] |

| Forge (FieldTemplater) | Field-based alignment and 3D-QSAR | Template generation, molecular alignment, field point calculation [6] |

| ChemBio3D Ultra | 3D structure generation and visualization | 2D to 3D structure conversion, preliminary conformational analysis [6] |

| CPANN Algorithms | Neural network-based QSAR modeling | Handling nonlinear relationships, adaptive descriptor weighting [11] |

| ZINC Database | Virtual compound library | Source of candidate compounds for virtual screening [6] |

| QuBiLS-MIDAS | Molecular descriptor calculation | Generation of 3D molecular descriptors for QSAR modeling [11] |

Molecular fields and 3D descriptors provide a powerful framework for predicting biological activity in anticancer drug design. The core principles outlined in this guide—from molecular field calculation and pharmacophore generation to statistical modeling and validation—enable researchers to extract critical structure-activity relationships and design optimized compounds with enhanced therapeutic potential. As computational methods continue to advance, particularly with adaptive algorithms like modified CPANN that dynamically adjust descriptor importance, 3D-QSAR approaches will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating the discovery of novel anticancer agents. The integration of these computational predictions with experimental validation remains essential for translating in silico insights into clinically effective therapeutics.

Why 3D-QSAR? Addressing the Limitations of Classical QSAR in Oncology

In the relentless pursuit of effective anticancer therapies, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling stands as a pivotal computational tool for lead compound optimization. While classical (2D) QSAR has contributed significantly to drug discovery, its limitations in addressing the three-dimensional structural nuances critical for target binding are increasingly apparent in oncology. This technical guide delineates the theoretical and practical advantages of 3D-QSAR methodologies over classical approaches within the context of anticancer drug design. We provide a comprehensive comparison of both techniques, detail experimental protocols for implementing 3D-QSAR studies, and present case studies demonstrating its successful application in identifying novel oncology therapeutics. The integration of 3D-QSAR into modern computational workflows promises to enhance the efficiency and efficacy of cancer drug discovery by providing superior insights into the stereoelectronic determinants of biological activity.

Cancer remains one of the most formidable challenges in modern medicine, with breast cancer alone accounting for nearly 1 in 3 cancers diagnosed in women worldwide [6]. The inherent heterogeneity of malignant cells, coupled with the rapid development of drug resistance, necessitates the continuous development of novel chemotherapeutic agents [12] [6]. In silico methods, particularly Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR), have emerged as indispensable tools in early drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict compound activity and prioritize synthesis candidates [13].

Classical QSAR, also known as Hansch Analysis, operates on the principle that biological activity correlates with physicochemical properties and structural descriptors derived from molecular formula [14]. These models utilize calculated descriptors such as log P (lipophilicity), molar refractivity, and electronic parameters to build statistical correlations with biological endpoints [13]. However, this approach contains a fundamental limitation: it reduces complex three-dimensional molecular interactions to one- or two-dimensional descriptors, potentially overlooking critical stereoelectronic features governing ligand-receptor interactions in cancer biology [14].

Three-dimensional QSAR (3D-QSAR) methodologies address this limitation by incorporating the spatial and electronic properties of molecules as they interact with biological targets [14]. By analyzing molecular force fields, shape characteristics, and electrostatic potentials, 3D-QSAR provides a more physiologically relevant representation of the ligand-target interface, offering distinct advantages for optimizing anticancer compounds where precise molecular complementarity often dictates therapeutic efficacy [12] [6].

Theoretical Foundations: Classical vs. 3D-QSAR

Fundamental Principles of Classical QSAR

Classical QSAR formalizes the relationship between chemical structure and biological activity using mathematical models based on physicochemical descriptors and topological parameters [13]. The approach originated with the seminal work of Hansch and Fujita, who extended Hammett's equation to biological systems with the formulation:

log(1/C) = bâ‚€ + bâ‚σ + bâ‚‚logP

where C represents the molar concentration required to elicit a biological response, σ represents electronic effects of substituents, and logP represents the lipophilicity of the compound [13]. These linear free-energy relationship (LFER) models assume that biological activity can be correlated with substituent parameters that account for hydrophobic, electronic, and steric effects.

The primary strength of classical QSAR lies in its computational efficiency and ability to rapidly screen large chemical libraries using easily calculable descriptors [14]. However, this approach suffers from the critical limitation of being unable to account for stereochemistry, conformational flexibility, and three-dimensional molecular interactions—factors particularly relevant in drug design for cancer targets where enantioselectivity often significantly impacts biological activity [15].

Fundamental Principles of 3D-QSAR

3D-QSAR methodologies, including Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), are founded on the principle that differences in biological activity correspond to changes in the shapes and strengths of non-covalent interaction fields surrounding molecules [14]. These techniques calculate steric (van der Waals) and electrostatic (Coulombic) potentials at regularly spaced grid points around aligned molecules, then correlate these field values with biological activity using statistical methods like Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression [12] [16].

The CoMSIA approach extends beyond CoMFA by incorporating additional similarity indices, including hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields, providing a more comprehensive description of ligand-receptor interactions [14]. A key advantage of 3D-QSAR is its ability to visualize results as three-dimensional coefficient contour maps, which directly indicate regions where specific structural modifications may enhance or diminish biological activity—information that is inaccessible through classical QSAR approaches [12] [6].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Classical and 3D-QSAR Approaches

| Feature | Classical QSAR | 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representation | 1D/2D descriptors (e.g., logP, molar refractivity) | 3D molecular fields and spatial descriptors |

| Structural Alignment | Not required | Critical step requiring bioactive conformation |

| Stereochemistry | Generally not accounted for | Explicitly considered |

| Output Visualization | Statistical plots and equations | 3D contour maps showing favorable/unfavorable regions |

| Information Content | Global molecular properties | Local molecular interaction fields |

| Computational Demand | Lower | Higher |

| Interpretation | Statistical relationships between descriptors and activity | Spatial understanding of structure-activity relationships |

Critical Limitations of Classical QSAR in Anticancer Drug Design

Inability to Capture Three-Dimensional Molecular Interactions

Classical QSAR methodologies rely primarily on descriptors derived from molecular connectivity or two-dimensional representations, fundamentally limiting their ability to account for spatial orientation and stereoelectronic effects in ligand-target interactions [14]. This represents a significant shortcoming in oncology drug design, where the precise three-dimensional arrangement of functional groups often determines binding specificity and potency against cancer-related targets such as kinase domains, nuclear receptors, and epigenetic regulators.

For example, in the development of dihydropteridone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors for glioblastoma treatment, classical QSAR models demonstrated substantially lower predictive capability (R² = 0.6682) compared to 3D-QSAR approaches (R² = 0.928), highlighting the critical importance of spatial molecular features in optimizing anticancer activity [12]. The inability of classical QSAR to differentiate enantiomers—particularly problematic given the frequent enantioselectivity of drug-target interactions—further underscores its limitations for modern anticancer drug development [15].

Limited Insight for Structural Optimization

While classical QSAR can identify which molecular descriptors correlate with biological activity, it provides limited guidance on how to structurally modify lead compounds to improve their pharmacological profile [14]. The statistical relationships between global molecular properties and activity offer little insight into the specific spatial locations where introducing bulky groups might enhance steric complementarity or where incorporating hydrogen bond donors/acceptors might improve binding affinity.

In the optimization of maslinic acid analogs for breast cancer therapy, researchers found that 3D-QSAR contour maps precisely identified regions where structural modifications would enhance activity against MCF-7 cell lines—information that was unobtainable through classical QSAR approaches [6]. The activity-atlas models generated through 3D-QSAR revealed positive and negative electrostatic regions, favorable and unfavorable hydrophobicity patterns, and shape requirements that directly informed the design of novel analogs with improved anticancer properties [6].

Challenges in Applicability Domain Definition

The applicability domain (AD) of a QSAR model defines the chemical space within which the model can make reliable predictions [17]. Classical QSAR approaches typically define applicability domain based on the ranges of descriptor values in the training set, which may not adequately capture the complexity of chemical space relevant for anticancer compounds [17] [15].

The "fuzzy" nature of chemical space boundaries in classical QSAR often leads to unreliable predictions for structurally novel scaffolds, a significant limitation when exploring new chemotypes for oncology applications [15]. In contrast, 3D-QSAR models incorporate alignment rules and field constraints that provide a more robust definition of the applicability domain based on molecular similarity in three-dimensional space, offering greater confidence when extrapolating to new compound classes [17] [6].

3D-QSAR Methodologies: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Compound Selection and Data Preparation

The foundation of any robust 3D-QSAR model is a carefully curated dataset of compounds with reliably measured biological activities. For anticancer applications, typically 20-50 compounds with activity values (ICâ‚…â‚€, ECâ‚…â‚€, or Káµ¢) spanning at least three orders of magnitude are recommended to ensure sufficient structural and activity diversity [12] [6]. The biological data should be obtained using consistent experimental protocols to minimize noise from assay variability.

The dataset is divided into training and test sets using activity stratification to ensure both sets represent similar ranges of activity and structural diversity. A common practice allocates 80-85% of compounds to the training set for model development and 15-20% to the test set for external validation [16] [6]. For the dihydropteridone derivatives study, 26 compounds were used for training and 8 for testing, resulting in a model with excellent predictive capability [12].

Molecular Alignment and Conformational Analysis

Proper molecular alignment is the most critical step in 3D-QSAR model development, as the quality of alignment directly determines model performance [6]. Several alignment strategies are employed:

- Pharmacophore-based alignment: Uses common structural features assumed essential for biological activity

- Database alignment: Aligns molecules to a known active compound with established bioactive conformation

- Field-based alignment: Maximizes similarity of molecular interaction fields

In the absence of target structural information, as with maslinic acid analogs, the FieldTemplater module (Forge software) can determine the bioactive conformation hypothesis using field and shape information from highly active compounds [6]. The XED (eXtended Electron Distribution) force field generates field points representing positive/negative electrostatic, van der Waals shape, and hydrophobic properties to create a 3D field point pattern template for alignment [6].

Diagram 1: Classical QSAR Workflow - A sequential process focusing on descriptor calculation and statistical modeling.

Field Calculation and Statistical Analysis

Following molecular alignment, steric and electrostatic fields are calculated at grid points surrounding the molecules using appropriate probes. In CoMFA, a sp³ carbon atom with +1 charge serves as the probe for both steric (Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (Coulombic potential) fields [14]. CoMSIA extends this approach by calculating similarity indices for steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor fields [12] [14].

The resulting field values serve as independent variables for Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression analysis, which correlates the field values with biological activity while addressing multicollinearity [6]. The model is validated using Leave-One-Out (LOO) or Leave-Group-Out cross-validation to determine the optimal number of components and avoid overfitting. The cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²) and conventional correlation coefficient (r²) serve as key metrics of model robustness and predictive capability [16] [6].

Diagram 2: 3D-QSAR Workflow - An integrated process emphasizing spatial alignment and 3D field analysis for structure-based design.

Model Validation and Application

Rigorous validation is essential to ensure model reliability for prospective compound design. The following validation criteria should be satisfied:

- Internal validation: q² > 0.5 for leave-one-out cross-validation

- External validation: Predictive r² > 0.6 for test set compounds

- Randomization tests: Y-scrambling to confirm model non-randomness

The validated model generates 3D coefficient contour maps that visualize regions where specific structural modifications may enhance activity [6]. For example, in the dihydropteridone derivative study, the "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN) descriptor combined with hydrophobic field information guided the design of compound 21E.153, which exhibited outstanding antitumor properties and docking capabilities [12].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR in Oncology

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | ChemDraw, ChemBio3D | 2D structure drawing and 3D structure generation |

| Geometry Optimization | Gaussian, HyperChem | Energy minimization and conformational analysis using methods like AM1/PM3 |

| Descriptor Calculation | CODESSA, Dragon | Computation of quantum-chemical and structural descriptors |

| 3D-QSAR Specific | Forge, SYBYL | Molecular field calculation, alignment, and PLS analysis |

| Validation Tools | QSARINS | Internal and external validation of model robustness |

| Database Screening | ZINC, PubChem | Source of compounds for virtual screening and similarity search |

Case Studies: Successful Application of 3D-QSAR in Oncology

3D-QSAR for Dihydropteridone Derivatives as PLK1 Inhibitors in Glioblastoma

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) represents one of the most aggressive and treatment-resistant brain cancers, with a 5-year survival rate below 5% [12]. Researchers developed both 2D and 3D-QSAR models for a series of dihydropteridone derivatives exhibiting promising PLK1 inhibitory activity, a key regulator of cell division frequently overexpressed in glioblastoma [12].

The heuristic method (HM) yielded a linear 2D-QSAR model with R² = 0.6682, while the 3D-QSAR CoMSIA model demonstrated superior performance with Q² = 0.628 and R² = 0.928 [12]. The 3D-QSAR model identified specific hydrophobic and electrostatic requirements for potency, enabling the design of novel compound 21E.153, which showed outstanding predicted activity and binding affinity in molecular docking studies [12]. This case highlights how 3D-QSAR can provide spatial insights that directly facilitate lead optimization for challenging oncology targets.

3D-QSAR Modeling of Maslinic Acid Analogs for Breast Cancer Therapy

With breast cancer accounting for 27% of all cancers in Indian women and emerging as the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women globally, developing novel therapeutics remains a critical priority [6]. Researchers performed a field-based 3D-QSAR study on maslinic acid, a natural triterpenoid with demonstrated anticancer activity, to guide analog design [6].

The derived PLS regression QSAR model showed excellent statistical parameters (r² = 0.92, q² = 0.75) following leave-one-out cross-validation [6]. Activity-atlas models revealed key structural requirements against MCF-7 breast cancer cells, including specific hydrophobic regions and electrostatic patterns. Virtual screening of the ZINC database identified 39 top hits from 593 initial compounds after applying Lipinski's Rule of Five and ADMET filters [6]. Compound P-902 emerged as the most promising candidate, showing favorable docking interactions with multiple breast cancer targets including AKR1B10, NR3C1, PTGS2, and HER2 [6].

Integrated 3D-QSAR and Molecular Docking for Shikonin-Based Anticancer Agents

Natural products continue to serve as valuable scaffolds for anticancer drug discovery, with shikonin and its derivatives demonstrating diverse biological activities against various cancer types [18]. Researchers implemented an integrated in silico framework to evaluate 24 acylshikonin derivatives, combining 3D-QSAR modeling with molecular docking against the cancer-associated target 4ZAU [18].

The Principal Component Regression (PCR) model demonstrated exceptional predictive performance (R² = 0.912, RMSE = 0.119), highlighting the significance of electronic and hydrophobic descriptors in cytotoxic activity [18]. Docking simulations identified compound D1 as the most promising derivative, forming multiple stabilizing hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with key residues of the target protein [18]. This case study illustrates the power of integrating 3D-QSAR with structure-based design approaches to accelerate natural product-based anticancer drug discovery.

Integrated Approaches: Combining 3D-QSAR with Complementary Methods

3D-QSAR in Multi-Method Drug Discovery Workflows

Modern anticancer drug discovery increasingly employs integrated computational workflows that combine 3D-QSAR with complementary techniques to leverage their respective strengths [19]. A representative workflow includes:

- 3D-QSAR for initial lead optimization based on known active compounds

- Molecular docking to validate binding modes and interactions with target proteins

- ADMET prediction to assess pharmacokinetic properties and toxicity risks

- Molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate complex stability and binding mechanics

- Retrosynthetic analysis to assess synthetic feasibility of proposed compounds

In a comprehensive study targeting aromatase for breast cancer treatment, researchers applied a combined strategy of 3D-QSAR, artificial neural networks (ANN), molecular docking, ADMET analysis, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and retrosynthesis to design novel anti-breast cancer agents [19]. This integrated approach identified candidate L5 as a promising aromatase inhibitor with significant potential compared to the reference drug exemestane [19].

3D-QSAR and Pharmacophore Modeling

Pharmacophore modeling represents a natural complement to 3D-QSAR by identifying the spatial arrangement of features essential for biological activity [13]. In a study on 2-nitroimidazooxazines as anti-tubercular agents (methodologically relevant to anticancer applications), researchers combined atom-based 3D-QSAR with six-point pharmacophore (AHHRRR) generation [16]. The resulting 3D-QSAR model showed excellent statistical significance (R² = 0.9521, Q² = 0.8589), while the pharmacophore model guided virtual screening of the PubChem database to identify novel multi-targeted inhibitors [16].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of QSAR Methodologies from Case Studies

| Case Study | Classical QSAR Performance | 3D-QSAR Performance | Key Advantages of 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dihydropteridone Derivatives (Glioblastoma) | R² = 0.6682 (Heuristic Method) | R² = 0.928, Q² = 0.628 (CoMSIA) | Superior predictive power and spatial guidance for optimization |

| Maslinic Acid Analogs (Breast Cancer) | Not reported | r² = 0.92, q² = 0.75 (Field-based) | Identification of specific hydrophobic and electrostatic requirements |

| Shikonin Derivatives (General Anticancer) | Multiple Linear Regression compared | R² = 0.912 (PCR model) | Integration with docking revealed key interaction residues |

| Fullerene Derivatives (Methodological Study) | Limited by descriptor representation | Comprehensive field analysis | Better description of ligand-receptor interactions |

The limitations of classical QSAR approaches—particularly their inability to account for three-dimensional molecular features, provide spatial guidance for structural optimization, and adequately define applicability domains—present significant challenges in anticancer drug design. 3D-QSAR methodologies directly address these limitations by incorporating stereoelectronic properties, molecular interaction fields, and spatial alignment into the modeling process.

The case studies presented demonstrate that 3D-QSAR consistently outperforms classical approaches in predictive accuracy and, more importantly, provides actionable insights for lead optimization through visualization of favorable and unfavorable interaction regions. When integrated with complementary methods such as molecular docking, pharmacophore modeling, ADMET prediction, and molecular dynamics simulations, 3D-QSAR becomes an indispensable component of modern oncology drug discovery workflows.

As the field advances, the integration of 3D-QSAR with artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches promises to further enhance its predictive power and utility in developing novel therapeutics against challenging oncology targets. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting 3D-QSAR methodologies represents a strategic imperative for advancing anticancer drug discovery in the era of precision medicine.

The rational design of anticancer drugs relies on a fundamental understanding of the molecular forces that govern the interaction between a ligand (typically a potential drug molecule) and its biological target (often a protein or enzyme). The biological receptor does not perceive a ligand as a simple set of atoms and bonds; rather, it interacts with a three-dimensional shape that carries a complex distribution of molecular forces [20]. These interactions are determined predominantly by steric (van der Waals), electrostatic (Coulombic), and hydrophobic effects, which collectively determine the binding affinity and specificity of a ligand for its target. Within the framework of Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling, these forces are quantified as molecular fields surrounding the ligand molecules. This methodology is particularly powerful in situations where the detailed three-dimensional structure of the receptor is unknown, as it allows for the correlation of these computed fields with experimentally measured biological activities to guide the optimization of novel therapeutic agents [21] [20].

Fundamental Force Fields and Their Origins

The Steric (Van Der Waals) Field

Steric effects arise from the spatial arrangement of atoms within molecules. When atoms come into close proximity, a rise in the energy of the molecule occurs due to steric hindrance, which is a consequence of the repulsive forces between overlapping electron clouds [22]. These nonbonding interactions profoundly influence the molecular conformation and reactivity. In the context of ligand-target binding, steric forces can be either repulsive or attractive. At very short distances, significant repulsion occurs due to the interpenetration of electronic clouds. At slightly longer ranges, attractive dispersion forces prevail [20]. The steric potential describes these non-electrostatic interactions between non-bonded atoms and is critically important for the final step of binding, as it controls how well the ligand fits into the binding pocket of the target. The associated energy is often calculated using a Lennard-Jones potential, which captures both the repulsive and attractive components of the van der Waals interaction [20].

Table 1: Characteristics of Steric Interactions

| Feature | Description | Impact on Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Spatial arrangement of atoms and electron clouds [22] | Determines shape complementarity |

| Repulsive Component | Electron cloud overlap at short distances [20] | Prevents unfavorable clashes |

| Attractive Component | Dispersion forces (London forces) at intermediate distances [20] | Provides stabilization energy |

| Distance Dependency | Inverse 12th power (repulsive) [20] | Very short-range effect |

| Probe for 3D-QSAR | Carbon sp³ atom [20] | Maps shape and bulk requirements |

The Electrostatic (Coulombic) Field

Electrostatic interactions occur between polar or charged groups on the ligand and the target. These interactions are governed by Coulomb's law and can be either attractive (between opposite charges) or repulsive (between like charges) [20]. Since the electrostatic energy is expressed as the inverse of the distance between interacting atoms, the electrostatic field exerts influence over relatively long ranges (e.g., 10 angstroms or more). This long-range character means that electrostatic forces often drive the initial approach and orientation of the ligand toward the binding site. The treatment of these interactions in computational models can vary in complexity, from mean-field approaches like Debye-Hückel theory, which uses an implicit screening length, to explicit modeling of all ionic species in solution, with the latter providing more accurate but computationally expensive results [23].

Table 2: Characteristics of Electrostatic Interactions

| Feature | Description | Impact on Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Charges and polar groups [20] | Guides initial ligand approach |

| Attractive/Repulsive | Opposite charges attract; like charges repel [20] | Provides directionality |

| Distance Dependency | Inverse of the distance (râ»Â¹) [20] | Long-range effect |

| Solvent/Salt Effect | Screening by ionic strength [23] | Modulates interaction strength |

| Probe for 3D-QSAR | Carbon sp³ atom with a +1 charge [20] | Maps charge and polarity requirements |

The Hydrophobic Field

Hydrophobic interactions are a driving force in biomolecular recognition, primarily due to the entropic gain associated with the release of ordered water molecules from hydrophobic surfaces upon ligand binding. These interactions are not attractions between hydrophobic groups per se, but rather the thermodynamic consequence of water molecules reorganizing to minimize their contact with non-polar surfaces. Hydrophobic interactions are a major contributor to binding affinity, and systematic analyses of protein-ligand complexes have shown that hydrophobic contacts are the most common interactions, and are generally enriched in high-efficiency ligands [24]. In fact, the frequency of hydrogen bonds is reduced from 59% to 34% of that of hydrophobic contacts in efficient binders, highlighting the critical role of hydrophobicity in achieving potent binding [24]. The extent of a molecule's hydrophobicity is determined by the number, size, and distribution of hydrophobic patches on its surface, which are special characteristics of each individual protein or ligand [25].

Table 3: Characteristics of Hydrophobic Interactions

| Feature | Description | Impact on Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Entropic gain from water displacement [25] | Major driving force for binding |

| Solvent Role | Water molecules form cages around non-polar surfaces [25] | The interaction is mediated by solvent |

| Salt Effect | High salt concentration promotes hydrophobic interaction (salting-out) [25] | Can be used to modulate binding |

| Distance Dependency | Complex, based on solvent reorganization | Effective at short to intermediate ranges |

| Prevalence | Most common interaction type in PDB complexes [24] | Critical for high ligand efficiency |

Quantifying Molecular Fields in 3D-QSAR

The Molecular Interaction Field (MIF) Framework

The core principle of 3D-QSAR is the mapping and statistical comparison of the molecular fields surrounding a set of ligand molecules to establish a quantitative relationship with their biological activities [20]. This is achieved by calculating Molecular Interaction Fields (MIFs), which are 3D distributions of interaction energies between a molecule and a chosen probe. To compute these fields, a 3D lattice of grid points is superimposed around the molecule, and the interaction energy between the molecule and the probe is calculated at each grid point using appropriate potential energy functions [20]. This lattice sampling allows for the finite and manageable calculation of MIFs. The resulting fields can be visualized as iso-potential surfaces, which are 3D surfaces connecting all points of the same interaction energy value, providing intuitive, visual insights into the regions where specific interactions favorably or unfavorably influence biological activity.

Diagram 1: 3D-QSAR Field Calculation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the standard computational workflow for deriving a 3D-QSAR model, from ligand preparation through field calculation and statistical analysis.

The Probe Concept and Field Calculation

A probe is a conceptual or computational entity used to test for the presence and strength of a specific molecular field. It is placed at numerous points in the space around a molecule to quantitatively measure the value of the field created by the molecule at each location [20]. The probe must be of the same type as the field to be measured.

- Probing the Steric Field: The steric field is typically probed using a neutral carbon sp³ atom. The interaction energy is calculated at each grid point using a potential function such as the Lennard-Jones 6-12 potential, which captures both the attractive and repulsive components of the van der Waals interaction [20].

- Probing the Electrostatic Field: The electrostatic field is measured using a carbon sp³ atom with a charge of +1. The interaction energy is calculated using Coulomb's law, summing the interactions between the point charge on the probe and the point charges on the atoms of the molecule [20].

- Probing the Hydrophobic Field: While steric and electrostatic probes are standard, the concept can be extended to other fields. Hydrophobic fields, or Molecular Lipophilicity Potentials (MLP), can be calculated using probes representing hydrophobic fragments or based on empirical methods like HINT, which calculates a hydrophobic field from atom-based parameters [20].

The probe concept has been significantly expanded in sophisticated methods like the GRID approach, developed by Peter Goodford. GRID utilizes dozens of chemically realistic probes, including single atoms, water, functional groups (methyl, amine, carbonyl), and even metal cations, to explore the interaction potential of a binding site in great detail [20].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Comparative Molecular Similarity Index Analysis (CoMSIA)

The CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Index Analysis) method is a powerful and popular 3D-QSAR technique that improves upon earlier methods like CoMFA. A recent study on novel 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives as MAO-B inhibitors for neurodegenerative diseases provides an excellent example of a modern CoMSIA application [21].

Protocol:

- Ligand Preparation: A set of compounds with known biological activity (e.g., ICâ‚…â‚€ values) is collected. Their 2D structures are drawn and converted to 3D structures using software like ChemDraw and Sybyl-X. The 3D structures are then energy-minimized to obtain their most stable conformations [21].

- Molecular Alignment: All molecules are superimposed onto a common reference scaffold or a hypothesized pharmacophore model. This alignment is critical, as it assumes that all molecules bind to the target in a similar orientation [21].

- Field Calculation: The CoMSIA method calculates several similarity indices using a common probe. Typically, these include steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond donor and acceptor fields [21].

- Statistical Analysis: The calculated field values for all compounds are compiled into a data matrix. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is used to correlate the field descriptors with the biological activity values. The model is validated using techniques like leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation, yielding predictive metrics such as q² (cross-validated correlation coefficient) and r² (non-cross-validated correlation coefficient) [21]. In the cited study, the CoMSIA model exhibited a q² of 0.569 and an r² of 0.915, indicating a model with good predictive ability and high statistical significance [21].

Molecular Docking and Dynamics

Molecular docking and dynamics (MD) simulations are complementary techniques used to understand the stability and detailed mechanics of ligand-target interactions predicted by 3D-QSAR models.

Protocol:

- Molecular Docking: The most promising compounds identified from the 3D-QSAR analysis are subjected to molecular docking into the binding site of the target protein (e.g., MAO-B). Software such as Discovery Studio (LigandFit, CDOCKER) or AutoDock is used for this purpose. Docking predicts the preferred orientation (pose) of the ligand and provides a docking score representing the estimated binding affinity [21] [26].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: To assess the stability of the docked complex under more realistic conditions, MD simulations are performed (e.g., for 100 nanoseconds). The complex is solvated in a water box, ions are added to neutralize the system, and Newton's equations of motion are solved over time. Key analyzed parameters include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the stability of the protein-ligand complex. Stable binding is indicated by RMSD values fluctuating within a small range (e.g., 1.0-2.0 Ã…) [21].

- Binding Free Energy Calculations: Methods like Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) are used to calculate the binding free energy, decomposing it into contributions from van der Waals, electrostatic, and solvation energies [21].

- Energy Decomposition: This analysis reveals the contribution of key amino acid residues to the total binding energy, identifying which residues are most critical for stabilizing the complex through various interaction types [21].

Analysis of Protein-Ligand Interaction Databases

A systematic, large-scale analysis of experimentally determined protein-ligand structures provides statistically robust insights into the real-world prevalence and impact of different interaction types.

Protocol:

- Data Curation: A non-redundant set of high-resolution (e.g., ≤2.5 Å) X-ray structures of protein-ligand complexes is compiled from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Ligands are filtered to include only medicinally relevant small molecules, excluding buffers and crystallization additives [24].

- Interaction Detection: Software tools and algorithms (e.g., PDBeMotif, PELIKAN) are used to automatically identify and classify atomic interactions (e.g., hydrophobic, hydrogen bond, salt bridge, π-stacking) based on predefined geometric criteria (e.g., atom pairs within 4.0 Å) [24].

- Frequency and Efficiency Analysis: The frequency of each interaction type is calculated across the entire dataset. To understand which interactions correlate with strong binding, ligands can be ranked by a Fit Quality (FQ) score (a size-adjusted measure of ligand efficiency), and the interaction patterns of the top and bottom performers are compared [24]. This analysis quantitatively demonstrates that hydrophobic interactions are more frequent in high-efficiency ligands [24].

Table 4: Essential Resources for 3D-QSAR and Interaction Analysis

| Category | Item / Software | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software Suites | Sybyl-X [21] | Comprehensive molecular modeling and 3D-QSAR (e.g., CoMSIA). |

| Discovery Studio (LigandFit, CDOCKER) [26] | Molecular docking and simulation studies. | |

| GRID [20] | Structure-based analysis of binding sites using multiple probes. | |

| Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [24] | Source of 3D protein-ligand complex structures for analysis and docking. |

| PDBbind [24] | Curated database of binding affinities for structures in the PDB. | |

| Computational Probes | C sp³ (neutral) [20] | Standard probe for calculating steric molecular fields. |

| C sp³ (+1 charge) [20] | Standard probe for calculating electrostatic molecular fields. | |

| Water, Methyl, Amine, Carboxylate [20] | Multi-atom probes in GRID for mapping specific functional group interactions. | |

| Analysis Tools | LigPlot [26] | Generates 2D diagrams of ligand-protein interactions. |

| VMD [20] | Visualization and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectories. |

Steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields form the foundational triad of molecular interactions that control ligand-target recognition and binding affinity. In the context of anticancer drug design, the ability to quantify and model these forces through 3D-QSAR approaches like CoMSIA provides a powerful, rational framework for optimizing lead compounds. Integrating these methods with molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and large-scale bioinformatic analyses of structural databases creates a robust pipeline for modern drug discovery. The insights gained—such as the primacy of hydrophobic interactions in high-efficiency binders and the critical balance between long-range electrostatic steering and short-range steric complementarity—provide medicinal chemists with a strategic roadmap. By systematically applying these principles, researchers can more efficiently navigate the chemical space toward novel, potent, and selective anticancer therapeutics.

The Critical Role of 3D-QSAR in Targeting Key Cancer Proteins and Pathways

In modern anticancer drug design, the complexity of cancer biology demands strategies that can overcome the limitations of single-target therapies, which often fail due to compensatory pathways and drug resistance. Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has emerged as a pivotal computational approach that addresses this challenge by enabling the rational design of multi-target inhibitors. Unlike traditional QSAR methods that rely on two-dimensional molecular descriptors, 3D-QSAR incorporates the critical three-dimensional structural characteristics of molecules, providing superior predictive ability for biological activity based on conformational and steric properties [9]. This advanced methodology allows medicinal chemists to visualize the interaction fields between ligands and target proteins, facilitating the optimization of compound structures for enhanced potency and selectivity against key cancer targets.

The foundational 3D-QSAR techniques, primarily Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), have revolutionized computer-aided drug design by establishing reliable correlations between molecular structure variations and biological activity [27] [9]. These approaches have become indispensable in oncology drug discovery, particularly for designing compounds that simultaneously inhibit multiple cancer-related proteins and pathways. By leveraging 3D-QSAR insights, researchers can efficiently prioritize the most promising candidate molecules for synthesis and biological testing, significantly accelerating the drug development pipeline while reducing associated costs and resource expenditures [9].

Key Cancer Targets and Multi-Target Inhibition Strategies

Critical Proteins in Cancer Progression

Cancer pathogenesis involves multiple interconnected signaling pathways and regulatory proteins that collectively drive tumor development and progression. Key among these are cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), which regulates cell cycle progression; epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a critical mediator of cell proliferation and survival signals; and tubulin, whose polymerization dynamics are essential for mitotic spindle formation and cell division [28]. Simultaneous inhibition of these strategically selected targets presents a powerful approach to disrupt cancer cell viability while mitigating the development of resistance commonly observed with single-target agents [28].

Other significant targets in cancer therapy include glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), which is implicated in multiple signaling pathways and represents a promising target particularly in therapeutic areas beyond oncology, and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B), which has been explored in neurodegenerative diseases but demonstrates the broader applicability of 3D-QSAR methodologies [27] [9]. The multi-target inhibition strategy leverages the polypharmacology concept, where single chemical entities are designed to interact with multiple specific targets simultaneously, providing enhanced therapeutic efficacy compared to monotherapies or drug combinations [28].

Established Multi-Target Inhibitors in Cancer Research

Table 1: Representative Multi-Target Inhibitors Designed Using 3D-QSAR Approaches

| Compound Class | Key Targets | Cancer Type | Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) | Reference Compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylindole derivatives | CDK2, EGFR, Tubulin | Breast Cancer (MCF-7) | -7.2 to -9.8 | Molecule 39 |

| 6-Hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamides | MAO-B | Neurodegenerative diseases (demonstrating methodology) | N/A | Selegiline, Rasagiline |

| Oxadiazole derivatives | GSK-3β | Alzheimer's disease (demonstrating methodology) | N/A | N/A |