2D-QSAR vs. 3D-QSAR: A Comprehensive Performance Comparison for Glioblastoma Drug Discovery

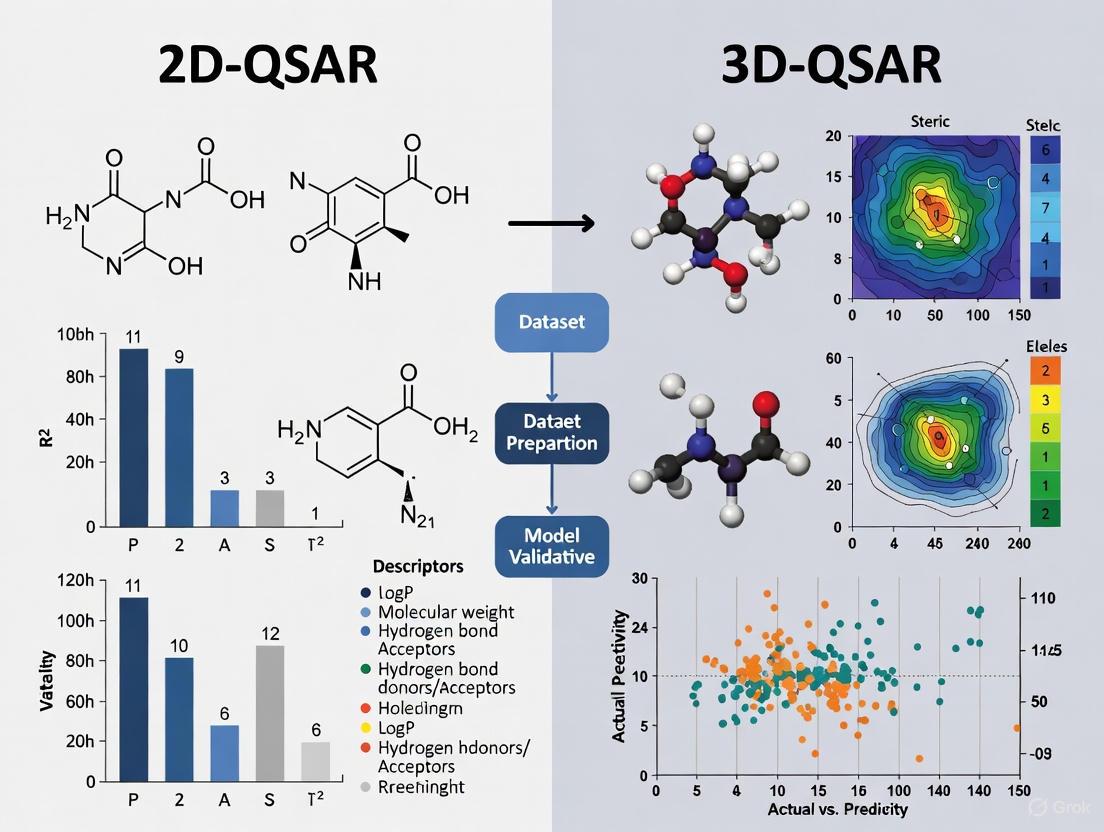

This article provides a detailed comparison of 2D and 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models in the context of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) therapeutics.

2D-QSAR vs. 3D-QSAR: A Comprehensive Performance Comparison for Glioblastoma Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of 2D and 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models in the context of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) therapeutics. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, methodological applications, common troubleshooting strategies, and validation techniques. By synthesizing current research and case studies, the article guides the selection and optimization of QSAR approaches to enhance predictive accuracy and efficiency in anti-glioblastoma compound design, ultimately supporting accelerated drug discovery efforts.

Understanding QSAR Fundamentals: Why 2D and 3D Approaches Matter in Glioblastoma Research

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most prevalent and aggressive primary malignant brain tumor in adults, characterized by wide inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity, rapid proliferation, and diffuse infiltration into surrounding brain tissue. [1] [2] Despite standard-of-care treatment involving maximal safe surgical resection, radiotherapy, and temozolomide chemotherapy, the prognosis for GBM patients remains dismal, with a median overall survival of only 12 to 18 months. [1] [2] [3] The highly infiltrative nature of GBM makes complete surgical eradication challenging, and the tumor develops robust resistance to conventional therapies, leading to nearly universal recurrence. [4] [1] This dire clinical outlook underscores the urgent need for innovative therapeutic strategies and efficient drug discovery platforms to combat this devastating disease.

Performance Comparison of 2D-QSAR vs. 3D-QSAR in Glioblastoma Research

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of 2D- and 3D-QSAR Models from GBM Studies

| Model Type | Specific Method | Statistical Performance | Dataset Size (Compounds) | Key Molecular Descriptors/Fields Analyzed | Reference Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-QSAR (Linear) | Heuristic Method (HM) | R² = 0.6682, R²cv = 0.5669 [4] | 34 Dihydropteridone derivatives [4] | Min exchange energy for a C-N bond (MECN), among 5 others [4] | Dihydropteridone PLK1 inhibitors [4] |

| 2D-QSAR (Nonlinear) | Gene Expression Programming (GEP) | R²training = 0.79, R²validation = 0.76 [4] | 34 Dihydropteridone derivatives [4] | Information not specified in study [4] | Dihydropteridone PLK1 inhibitors [4] |

| 3D-QSAR | CoMSIA | Q² = 0.628, R² = 0.928, F-value = 12.194, Standard Error of Estimate (SEE) = 0.160 [4] | 34 Dihydropteridone derivatives [4] | Steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor & acceptor fields [4] | Dihydropteridone PLK1 inhibitors [4] |

| Machine Learning (2D) | LightGBM (FAK inhibitors) | R² = 0.892, MAE = 0.331, RMSE = 0.467 [5] | 1,280 FAK inhibitors [5] | CDK fingerprints, CDK extended fingerprints, substructure counts [5] | FAK inhibitors for GBM [5] |

The comparative analysis of model performance reveals a clear hierarchy. The 3D-QSAR model, particularly the CoMSIA approach, demonstrated superior predictive capability and statistical robustness, as indicated by its high R² and Q² values, and low standard error. [4] The nonlinear 2D-QSAR model (GEP) showed intermediate performance, a significant improvement over the linear HM model, highlighting the value of advanced algorithms for capturing complex structure-activity relationships. [4] Modern 2D machine learning models, built on very large datasets, can achieve performance metrics that rival or even exceed traditional 3D-QSAR, underscoring the impact of data volume and advanced learning techniques. [5]

Detailed Experimental Protocols for QSAR Model Development

Protocol 1: 2D-QSAR Modeling for Dihydropteridone Derivatives

This protocol outlines the process used to develop both linear and nonlinear 2D-QSAR models for a series of dihydropteridone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors for GBM. [4]

- Dataset Curation and Preparation: A set of 34 dihydropteridone derivatives with known anti-glioma activity (IC50 values) was compiled. [4] The set was randomly partitioned into a training set (26 compounds) for model construction and a test set (8 compounds) for external validation. [4]

- Molecular Structure Optimization and Descriptor Calculation: The 2D chemical structures were sketched using ChemDraw and subsequently optimized for geometry and energy using HyperChem software. The optimization process involved:

- Initial optimization using the molecular mechanics force field (MM+).

- Further optimization using semi-empirical methods (AM1 or PM3 models) until the root mean square gradient reached 0.01. [4]

- A wide range of molecular descriptors (quantum chemical, structural, topological, geometrical, electrostatic) were calculated using the CODESSA program. [4]

- Linear Model Construction (Heuristic Method): The Heuristic Method in CODESSA was used to rapidly screen all calculated descriptors. It selected the optimal set of six descriptors that effectively represented the chemical structure while excluding those with minimal impact. The model was iteratively refined by adding descriptors until further additions provided negligible improvement, with correlation evaluated using the F-test, R², and R²cv. [4]

- Nonlinear Model Construction (Gene Expression Programming): The GEP algorithm was employed. This involved:

- Generating an initial population of chromosomes from a predefined function set and terminal set (including the molecular descriptors).

- Encoding these chromosomes into Expression Trees (ETs) to represent mathematical equations.

- Iteratively applying fitness functions, selection (elite roulette wheel), and genetic operations (mutation, transposition, recombination) to evolve the population until a model with satisfactory predictive performance for the training and validation sets was achieved. [4]

Protocol 2: 3D-QSAR Modeling Using CoMSIA

This protocol details the development of a 3D-QSAR model using the Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) method on the same dataset of dihydropteridone derivatives. [4]

- Molecular Alignment and Field Calculation: The 3D structures of all 34 compounds were aligned in space based on a common template or pharmacophoric core. This critical step ensures that the comparative analysis is conducted in a consistent molecular frame of reference. [4]

- Similarity Indices Probe Interaction: A common probe atom was used to calculate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor and acceptor fields around each aligned molecule. These fields collectively represent the molecular interaction characteristics with a hypothetical receptor. [4]

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis: The CoMSIA field values were used as independent variables, and the biological activity (pIC50) was used as the dependent variable in a Partial Least Squares regression analysis. PLS effectively handles the high collinearity between the many field descriptors. [4]

- Model Validation: The model was rigorously validated internally using leave-one-out cross-validation (yielding Q²) and externally by predicting the activity of the test set compounds that were excluded from the model building process. [4]

Visualizing QSAR Workflows and GBM Signaling Pathways

QSAR Model Development Workflow

Key Signaling Pathways as GBM Therapeutic Targets

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GBM QSAR and Experimental Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use in Context |

|---|---|---|

| CHEMBL Database | A curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, providing chemical structures and bioactivity data. [5] | Sourcing chemical structures and IC50 values for Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) inhibitors and compounds tested on U87-MG glioma cells to build large training sets for machine learning models. [5] |

| CODESSA Software | A comprehensive program for calculating a wide range of molecular descriptors essential for 2D-QSAR analysis. [4] | Calculating quantum chemical, topological, and electrostatic descriptors for dihydropteridone derivatives to correlate structure with PLK1 inhibitory activity. [4] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor Software | An open-source software used to calculate molecular fingerprints and descriptors directly from chemical structures. [5] | Generating CDK and substructure fingerprint counts for thousands of compounds, enabling the conversion of chemical structures into numerical vectors for machine learning algorithms. [5] |

| HyperChem | A molecular modeling environment used for molecular mechanics and semi-empirical geometry optimization. [4] | Energy minimization and 3D structure preparation of compounds prior to 3D-QSAR field calculation or descriptor computation. [4] |

| SYBYL (CoMFA/CoMSIA) | A commercial software suite containing the CoMFA and CoMSIA modules for performing 3D-QSAR studies. [4] | Analyzing the influence of steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields around aligned dihydropteridone derivatives on their anti-glioma activity. [4] |

| Patient-Derived Glioma Stem Cells (GSCs) | In vitro models that recapitulate the molecular and cellular heterogeneity of human GBM better than traditional 2D cell lines. [1] [2] | Used for high-throughput phenotypic drug screening to identify patient-specific vulnerabilities and validate compounds identified in silico. [2] |

| 3D Cell Culture Systems | In vitro models that mimic the tumor microenvironment more accurately than 2D monolayers, leading to more physiologically relevant drug response data. [6] | Evaluating the cytotoxicity and apoptotic effects of combination therapies (e.g., Erlotinib and Imatinib), where 3D cultures often show different drug sensitivity compared to 2D cultures. [6] |

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling is a computational approach that mathematically links a chemical compound's structure to its biological activity [7]. In the critical field of glioblastoma (GBM) research, where developing effective chemotherapeutic agents remains a pressing challenge due to the highly invasive nature of the tumor and limitations of current treatments, QSAR models provide an efficient in-silico method for prioritizing promising drug candidates and guiding chemical modifications [8] [7]. The "two-dimensional" (2D) in 2D-QSAR refers to models that utilize molecular descriptors derived from the two-dimensional chemical structure, without considering spatial conformation. These models operate on the fundamental principle that structural variations influence biological activity, using physicochemical properties and molecular descriptors as predictor variables, while biological activity serves as the response variable [7]. For glioblastoma research, this approach has been successfully applied to various compound classes, including dihydropteridone derivatives and nitrogen-mustard compounds, to predict their anti-tumor efficacy and inform the design of more potent therapeutics [8] [9].

Fundamental Components of 2D-QSAR

Molecular Descriptors: The Numerical Representation of Chemistry

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations that quantify the structural, physicochemical, and electronic properties of molecules, forming the foundational variables in any QSAR model [7]. They serve as predictive inputs that correlate with the biological output, typically expressed as IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) or pIC50 values. In 2D-QSAR, these descriptors are calculated from the compound's two-dimensional structure and can be broadly categorized into several classes:

- Constitutional descriptors: Reflect molecular composition without connectivity (e.g., atom counts, bond counts, molecular weight)

- Topological descriptors: Encode connectivity patterns within the molecule (e.g., molecular connectivity indices, path counts)

- Geometrical descriptors: Capture shape characteristics from 2D coordinates

- Electrostatic descriptors: Quantify charge distribution and polarity

- Quantum chemical descriptors: Derived from electronic structure calculations (e.g., orbital energies, partial charges) [7] [9]

For glioblastoma-targeted compounds, specific descriptors have demonstrated particular significance. In dihydropteridone derivatives studied as PLK1 inhibitors, the "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN) descriptor was identified as the most significant in a 2D model containing six descriptors [8]. Similarly, in research on dipeptide-alkylated nitrogen-mustard compounds for osteosarcoma (a context methodologically relevant to GBM research), "Min electroph react index for a C atom" was found to have the greatest effect on compound activity [9].

Linear Modeling Techniques in 2D-QSAR

Linear QSAR models assume a straightforward mathematical relationship between molecular descriptors and biological activity, expressed in the general form:

Activity = w₁(Descriptor₁) + w₂(Descriptor₂) + ... + wₙ(Descriptorₙ) + b

Where wi represents the model coefficients, b is the intercept, and the activity is typically log-transformed (e.g., pIC50 = -logIC50) to normalize the distribution [7]. The Heuristic Method (HM) is a commonly employed technique for constructing these linear models, implemented in software packages like CODESSA [8] [9]. This method systematically evaluates descriptor pools through a multi-step process:

- Initial screening: All calculated descriptors are evaluated for their correlation with the activity

- Descriptor selection: Pairs of descriptors with the best statistical characteristics are identified

- Stepwise expansion: Additional descriptors are iteratively added to improve model performance

- Model refinement: The process continues until the optimal number of descriptors is reached [9]

Statistical measures including the coefficient of determination (R²), cross-validated R² (R²cv), F-test, and t-test are employed to evaluate descriptor significance and model robustness throughout this process [8] [9].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Comparison

Detailed Methodology for 2D-QSAR Model Development

Building a reliable 2D-QSAR model requires a systematic workflow with careful attention to each step:

Step 1: Dataset Curation and Preparation The initial phase involves compiling a dataset of chemical structures with associated biological activities from reliable sources such as literature or databases like ChEMBL [7] [10]. For glioblastoma research, this typically involves compounds with demonstrated activity against GBM cell lines or specific molecular targets like PLK1 or acid ceramidase (ASAH1) [8] [11]. Standardization of chemical structures follows, including removal of salts, normalization of tautomers, and handling of stereochemistry [7]. Biological activities (e.g., IC50 values) are converted to a common unit and scale, typically through logarithmic transformation to pIC50 values to normalize the distribution [12].

Step 2: Molecular Structure Optimization and Descriptor Calculation 2D chemical structures are sketched using software such as ChemDraw [8] [9]. While 2D-QSAR doesn't utilize 3D conformation, structure optimization ensures proper bond lengths and angles. Subsequently, molecular descriptors are calculated using specialized software packages including CODESSA, PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, or RDKit [8] [7] [9]. These tools can generate hundreds to thousands of descriptors encompassing constitutional, topological, geometrical, electrostatic, and quantum chemical properties.

Step 3: Dataset Partitioning The compiled dataset is divided into training and test sets, typically with 75-80% of compounds allocated to training and 20-25% to testing [8] [9]. Random partitioning is commonly employed, though methods like Kennard-Stone algorithm may be used to ensure representative chemical space coverage [7]. The training set builds the model, while the test set provides an external validation of predictive performance.

Step 4: Feature Selection and Model Construction Feature selection techniques identify the most relevant molecular descriptors, reducing dimensionality and minimizing overfitting [7]. The Heuristic Method systematically evaluates descriptor combinations, adding descriptors iteratively until model performance plateaus or declines [9]. Alternative feature selection approaches include:

- Filter methods (descriptor ranking based on individual correlation)

- Wrapper methods (using the modeling algorithm to evaluate descriptor subsets)

- Embedded methods (feature selection during model training) [7]

Step 5: Model Validation Robust validation employs both internal and external techniques. Internal validation uses cross-validation methods like leave-one-out (LOO) or k-fold cross-validation on the training set [7]. External validation assesses the model on the untouched test set, providing a realistic estimate of predictive performance on new compounds [7] [12].

Table 1: Performance Metrics for QSAR Model Validation

| Validation Type | Common Methods | Key Metrics | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation | Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation, k-Fold Cross-Validation | Q², R²cv | Estimates model performance on similar chemical space |

| External Validation | Test Set Prediction | R²pred, RMSEpred | Assesses predictive power on new compounds |

| Randomization Test | Y-Randomization | - | Confirms model isn't based on chance correlation |

Comparative Performance: 2D-QSAR vs. 3D-QSAR

Direct comparisons between 2D and 3D-QSAR approaches in glioblastoma research reveal distinct strengths and limitations for each methodology:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of 2D vs. 3D-QSAR Models in Glioblastoma Compound Studies

| Aspect | 2D-QSAR Models | 3D-QSAR Models |

|---|---|---|

| Model Performance (R²) | 0.6682 (HM linear model) [8] | 0.928 (CoMSIA model) [8] |

| Predictive Ability (Q²) | 0.5669 (R²cv) [8] | 0.628 (CoMSIA) [8] |

| Descriptor Interpretation | Direct chemical meaning (e.g., MECN) [8] | Field contributions (steric, electrostatic) [8] |

| Spatial Information | None | Comprehensive 3D molecular fields |

| Structural Requirements | No alignment needed | Requires molecular alignment |

| Application Scope | Broad chemical screening | Lead optimization |

In a study on dihydropteridone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors for glioblastoma, the Heuristic Method linear model achieved an R² of 0.6682 with a cross-validated R²cv of 0.5669 [8]. A nonlinear Gene Expression Programming (GEP) model demonstrated improved performance with R² values of 0.79 and 0.76 for training and validation sets respectively [8]. However, both were outperformed by the 3D-QSAR CoMSIA model, which exhibited superior fit with Q² = 0.628 and R² = 0.928 [8]. Similar trends were observed in studies on nitrogen-mustard compounds, where 3D-QSAR models generally provided higher predictive accuracy and more detailed structural insights for optimization [9].

Workflow Visualization: 2D-QSAR Modeling Process

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing 2D-QSAR models, highlighting the sequential steps from data preparation to model deployment:

2D-QSAR Modeling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for 2D-QSAR Research in Glioblastoma Drug Discovery

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Resource | Primary Function | Application in Glioblastoma Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Drawing | ChemDraw [8] [9] | 2D molecular structure creation | Initial compound design and representation |

| Structure Optimization | HyperChem [8] [9] | Molecular mechanics and semi-empirical optimization | Energy minimization and geometry optimization |

| Descriptor Calculation | CODESSA [8] [9], PaDEL-Descriptor [7], Dragon [7] | Computation of molecular descriptors | Generation of constitutional, topological, quantum chemical descriptors |

| Linear Modeling | CODESSA (Heuristic Method) [8] [9] | Construction of linear QSAR models | Developing predictive models for anti-glioma activity |

| Nonlinear Modeling | Gene Expression Programming [8] [9] | Development of nonlinear QSAR models | Capturing complex structure-activity relationships |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL [10] [11], PubChem [13] | Source of compound activity data | Access to experimental bioactivity data for model training |

| Programming Frameworks | KNIME [10], R [10] | Workflow automation and statistical analysis | Building automated QSAR modeling pipelines |

2D-QSAR modeling, with its foundation in molecular descriptors and linear modeling techniques like the Heuristic Method, remains a valuable approach in glioblastoma drug discovery despite the superior predictive performance often shown by 3D-QSAR methods [8] [9]. The strength of 2D-QSAR lies in its computational efficiency, straightforward interpretability of descriptors with direct chemical meaning, and ability to rapidly screen large compound libraries [7]. For glioblastoma researchers, these models provide actionable insights into the structural features governing anti-tumor activity, guiding the design of novel dihydropteridone derivatives, nitrogen-mustard compounds, and other chemotherapeutic agents [8] [9]. While 3D-QSAR excels in lead optimization by providing detailed spatial guidance, 2D-QSAR maintains its relevance in early-stage screening and when combined with 3D approaches in integrated workflows, offering a complementary perspective that continues to advance the development of much-needed therapeutic options for this challenging disease [8] [10].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a predictive framework to correlate the chemical structure of compounds with their biological activity [14]. While traditional 2D-QSAR uses numerical descriptors that are invariant to a molecule's conformation, 3D-QSAR extends this concept by treating molecules as three-dimensional objects with specific shapes and interaction potentials [14]. This transition from a "flat" to a spatial representation allows medicinal chemists to understand how a molecule's 3D shape, steric bulk, and electrostatic properties influence its binding to a biological target and its overall activity.

The application of these techniques is particularly valuable in challenging research areas such as glioblastoma (GBM) therapy development. GBM is the most common and malignant glial tumor of the central nervous system, characterized by rapid progression, resistance to conventional therapies, and a poor patient prognosis with a median overall survival of only 15-18 months post-diagnosis [15]. This review will objectively compare the performance of 2D and 3D-QSAR approaches within the context of glioblastoma compound research, providing experimental data and methodologies to guide researchers in selecting appropriate computational tools for their drug discovery projects.

Theoretical Foundations: From 2D Descriptors to 3D Molecular Fields

2D-QSAR: Classical Descriptors and Linear Models

Classical 2D-QSAR describes molecules using summary descriptors that do not depend on the molecule's three-dimensional orientation. These include fundamental physicochemical properties such as logP for hydrophobicity, molecular weight, or counts of specific atom types [14]. The mathematical models built using these descriptors establish a correlation between the molecular descriptors' quantity and class on drug activity [8].

A common approach in 2D-QSAR modeling is the Heuristic Method (HM), which is employed to construct linear models by extracting all molecular descriptors and conducting feature selection to determine the optimal number of descriptors that effectively represent the chemical structure while excluding those with minimal impact [8]. These models are evaluated using objective measures such as the F-test, coefficient of determination (R²), cross-validated R² (R² cv), and t-test [8].

3D-QSAR: Spatial Considerations and Field Analysis

In contrast, 3D-QSAR derives descriptors directly from the spatial structure of the molecule [14]. This approach explicitly considers the bioactive conformation—the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms believed to correspond to how the molecule binds to its protein target [14]. A 3D-QSAR model typically quantifies two primary types of molecular fields:

- Steric fields: Represent regions where molecular bulk may clash or accommodate other structures, typically measured using van der Waals or Lennard-Jones potentials.

- Electrostatic fields: Map areas of positive or negative electrostatic potential around the molecule, usually calculated using Coulombic potentials.

More advanced field methods such as Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extend this approach by incorporating additional fields including hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bond donor and acceptor properties [8] [14]. The core premise of 3D-QSAR is that differences in biological activity between compounds can be correlated with differences in their steric and electrostatic fields surrounding them, provided the molecules are properly aligned in what is presumed to be their bioactive conformation.

Critical Methodological Components

The Challenge of Conformational Analysis

One of the most critical and technically demanding aspects of 3D-QSAR is conformational analysis—the process of identifying the biologically active conformation of flexible molecules [16]. The main requirement of traditional 3D-QSAR methods is that molecules should be correctly overlaid in what is assumed to be their bioactive conformation [16]. However, identifying this active conformation for a flexible molecule is technically difficult and has been a bottleneck in the application of the 3D-QSAR method [16].

The selected conformation critically influences molecular alignment and descriptor calculation [14]. Since biologically active molecules for the same active site should share common interactions, their active conformations should possess common three-dimensional arrangements of pharmacophores—defined as an ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary to ensure optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target [16].

Molecular Alignment Strategies

Molecular alignment constitutes one of the most critical steps in 3D-QSAR, with the objective being to superimpose all molecules within a shared 3D reference frame that reflects their putative bioactive conformations [14]. This alignment assumes that all compounds share a similar binding mode. Common alignment strategies include:

- Bemis-Murcko Scaffold: Defines a core structure by removing all side chains and retaining only ring systems and linkers.

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS): Identifies the largest substructure shared among a set of molecules.

- Pharmacophore-based alignment: Uses common 3D arrangements of pharmacophore features to guide molecular overlay.

A poor alignment undermines the entire modeling process by introducing inconsistencies in descriptor calculations [14]. This challenge has led to the development of automated methods like AutoGPA, which uses pharmacophore queries to objectively select conformations and align them prior to 3D-QSAR modeling [16].

Field-Based Descriptor Calculation

Following alignment, 3D molecular descriptors are computed to numerically represent the steric and electrostatic environments of each molecule. The classic Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) method uses a lattice of grid points surrounding the aligned molecules [14]. At each point, a probe atom (typically an sp³ carbon with a +1 charge) measures steric (van der Waals) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies with the molecule [16] [14].

CoMSIA extends this approach by using Gaussian-type functions to evaluate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields, which smooth out abrupt field changes and enhance interpretability, especially across structurally diverse compounds [8] [14]. While CoMFA is highly sensitive to alignment quality, CoMSIA offers more tolerance to minor misalignments, thereby expanding its applicability to datasets with broader chemical diversity [14].

Experimental Comparison in Glioblastoma Research

Case Study: Dihydropteridone Derivatives as PLK1 Inhibitors

A recent study directly compared 2D and 3D-QSAR approaches for dihydropteridone derivatives, a novel class of PLK1 inhibitors exhibiting promising anticancer activity against glioblastoma [8]. The researchers developed multiple QSAR models using a dataset of 34 compounds and evaluated their predictive performance using standard statistical metrics. The experimental workflow and comparative results provide valuable insights into the relative strengths of each approach.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for comparative QSAR analysis of dihydropteridone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors for glioblastoma treatment.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The study directly compared the performance of 2D and 3D-QSAR models using multiple statistical metrics, providing objective data for evaluating each approach's effectiveness in predicting anti-glioma activity.

Table 1: Statistical Comparison of 2D vs. 3D-QSAR Models for Glioblastoma Compounds

| Model Type | Specific Method | Training R² | Validation Q² | Standard Error of Estimate (SEE) | F-Value | Key Descriptors/Fields |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-QSAR | Heuristic Method (HM) Linear | 0.6682 | 0.5669 | 0.0199 | Not Reported | Min exchange energy for C-N bond (MECN) [8] |

| 2D-QSAR | GEP Algorithm Nonlinear | 0.79 | 0.76 | Not Reported | Not Reported | Multiple descriptors including MECN [8] |

| 3D-QSAR | CoMSIA | 0.928 | 0.628 | 0.160 | 12.194 | Hydrophobic field combined with MECN descriptor [8] |

The performance data clearly demonstrates the superior statistical quality of the 3D-QSAR model, which achieved an exceptional fit characterized by a high R² value of 0.928 and a substantial F-value of 12.194 [8]. Empirical modeling outcomes underscored the preeminence of the 3D-QSAR model, followed by the GEP nonlinear model, while the HM linear model manifested suboptimal efficacy [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

2D-QSAR Methodology

For the 2D-QSAR analysis, the chemical structures were initially sketched using ChemDraw and subsequently optimized using HyperChem [8]. The optimization process employed molecular mechanics field (MM+) for initial optimization, followed by selection of the AM1 or PM3 model based on the presence or absence of S and P atoms [8]. The structure was cyclically optimized using the Polak-Ribiere method until the root mean square gradient reached a threshold of 0.01 [8]. The CODESSA program was utilized to compute molecular descriptors encompassing quantum chemistry, structure, topology, geometry, and electrostatic properties [8].

To mitigate the risk of overfitting, a random partitioning was applied to the set of 34 compounds at a ratio of 1:3, resulting in 8 compounds assigned to the test set and 26 compounds allocated to the training set [8]. The Heuristic Method was employed to extract all molecular descriptors, followed by feature selection to determine the optimal number of descriptors [8].

3D-QSAR Methodology

The 3D-QSAR analysis employed the CoMSIA approach to investigate the impact of drug structure on activity [8]. The process began with molecular alignment, where all compounds were superimposed in a shared 3D reference frame based on their putative bioactive conformations. The CoMSIA method then calculated similarity indices using a Gaussian-type functional form to evaluate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor and acceptor fields [8] [14].

A regular three-dimensional grid with a 2.0 Å separation surrounding all molecules was created [16]. Molecular fields around each molecule were evaluated by calculating interaction energies between the molecule and probe atoms placed at each grid point [16]. The partial-least-squares (PLS) analysis was used to derive the 3D-QSAR models, with the optimal number of components identified by leave-one-out cross-validation [8] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for QSAR Studies in Glioblastoma Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Modeling | ChemDraw | Chemical structure sketching and representation | Initial 2D structure creation [8] |

| Structure Optimization | HyperChem | Molecular mechanics and semi-empirical optimization | Geometry optimization using MM+, AM1, or PM3 models [8] |

| Descriptor Calculation | CODESSA | Computation of quantum chemical and topological descriptors | 2D-QSAR descriptor calculation [8] |

| 3D-QSAR Analysis | CoMSIA | Calculation of steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields | 3D-QSAR model development [8] [14] |

| Statistical Analysis | Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Multivariate regression for high-dimensional data | 3D-QSAR model building [16] [14] |

| Model Validation | Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation | Internal validation of model predictive ability | Determining optimal number of components [16] |

| Experimental Verification | Molecular Docking | Validation of predicted active compounds | Confirming binding affinity for designed compounds [8] |

Performance Assessment and Research Implications

The comparative analysis reveals distinct advantages and limitations for both 2D and 3D-QSAR approaches in glioblastoma compound research. The 2D-QSAR methods offer computational efficiency and simpler interpretation, with the heuristic linear model achieving moderate predictive ability (R² = 0.6682, Q² = 0.5669) [8]. The identification of "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN) as the most significant molecular descriptor provides concrete, actionable insight for medicinal chemists [8].

In contrast, 3D-QSAR approaches demonstrated superior statistical performance with exceptional model fit (R² = 0.928) and robust predictive capability (Q² = 0.628) [8]. The integration of the MECN descriptor with hydrophobic field information from the 3D-QSAR model led to the design and identification of compound 21E.153, a novel dihydropteridone derivative that exhibited outstanding antitumor properties and docking capabilities [8]. This successful application demonstrates the power of combining insights from both 2D descriptors and 3D field-based methods.

The 3D-QSAR contour maps provide visual guidance for rational drug design, indicating spatial regions where specific molecular modifications would enhance or diminish biological activity [14]. These maps translate the raw data of a 3D-QSAR model into an intuitive 'activity atlas' for medicinal chemists, showing where adding bulky groups increases (green contours) or decreases (yellow contours) activity, and which regions benefit from electronegative (red) or electropositive (blue) groups [14].

Diagram 2: Comparative analysis of 2D and 3D-QSAR approaches showing strengths, limitations, and research applications in glioblastoma drug discovery.

The comparative analysis of 2D and 3D-QSAR approaches for glioblastoma compound research demonstrates that each method offers distinct advantages depending on the research context. 2D-QSAR provides computationally efficient models with straightforward interpretation of key molecular descriptors, making it valuable for initial compound screening and prioritization. Meanwhile, 3D-QSAR approaches, particularly CoMSIA methods, deliver superior predictive performance and provide visual guidance for rational drug design through contour maps that highlight critical molecular regions for activity optimization.

The integration of both approaches—combining the descriptor-based insights from 2D-QSAR with the spatial field information from 3D-QSAR—proved particularly powerful in the design of novel dihydropteridone derivatives with enhanced anti-glioma activity [8]. This synergistic application offers a robust framework for advancing glioblastoma drug discovery, potentially contributing to the development of more effective chemotherapeutic agents for this challenging malignancy. As computational methods continue to evolve, the combination of these QSAR strategies with other in silico approaches such as molecular docking and dynamics simulations presents a promising path forward for addressing the critical unmet need in glioblastoma therapy.

The Importance of Comparing 2D and 3D-QSAR in Oncology Drug Discovery

In the relentless pursuit of effective oncology therapeutics, particularly for complex malignancies like glioblastoma (GBM), quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling has emerged as an indispensable tool for accelerating drug discovery. These computational approaches efficiently correlate the structural features of compounds with their biological activity, enabling the prediction of compound efficacy before costly synthesis and experimental testing. However, a critical question persists in modern cheminformatics: which QSAR paradigm—traditional 2D-QSAR or spatially informed 3D-QSAR—offers superior performance for specific oncology applications? The strategic comparison of these methodologies is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for optimizing resource allocation, improving predictive accuracy, and ultimately designing more effective cancer treatments. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of 2D and 3D-QSAR performance, leveraging experimental data from recent glioblastoma research to inform selection criteria for drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Divergence

2D-QSAR: Descriptor-Driven Predictive Modeling

2D-QSAR relies on molecular descriptors derived from the two-dimensional chemical structure, encompassing physicochemical properties (e.g., logP, molecular weight), electronic features, and topological indices [17]. These descriptors are numerically encoded and correlated with biological activity using statistical or machine learning methods such as Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), or more advanced algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forests (RF) [18] [19]. The primary strength of 2D-QSAR lies in its computational efficiency and its ability to handle large chemical datasets without requiring molecular alignment or conformational analysis.

3D-QSAR: Incorporating Spatial Molecular Fields

In contrast, 3D-QSAR methodologies, such as Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), consider the three-dimensional arrangement of molecules [8] [20]. These techniques calculate steric (shape), electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields around a set of aligned molecules. The core hypothesis is that a molecule's biological activity is dependent on its interaction with a receptor, which is profoundly influenced by these spatial characteristics [21]. While more computationally intensive and sensitive to molecular alignment, 3D-QSAR provides直观的 visual contour maps that offer direct structural guidance for molecular optimization.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of 2D and 3D-QSAR Approaches

| Feature | 2D-QSAR | 3D-QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representation | Topological descriptors, physicochemical properties | 3D steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic fields |

| Key Descriptors | Molecular weight, logP, HOMO/LUMO energies, topological indices [17] | Field values at grid points surrounding aligned molecules |

| Common Algorithms | MLR, PLS, SVM, Random Forests [18] [19] | PLS, CoMFA, CoMSIA [8] [20] |

| Alignment Dependent | No | Yes |

| Primary Output | Mathematical equation correlating descriptors to activity | 3D contour maps indicating favorable/unfavorable regions for substitution |

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Evidence from Glioblastoma Research

Direct comparative studies and individual case applications in oncology provide compelling data on the relative performance of 2D and 3D-QSAR models.

A Direct Comparative Study on Dihydropteridone Derivatives

A 2023 study investigating dihydropteridone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors for glioblastoma treatment offers a direct, quantitative comparison. The researchers constructed multiple QSAR models and evaluated their performance using standard statistical metrics [8].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of QSAR Models for Dihydropteridone Derivatives [8]

| Model Type | Specific Method | R² (Training) | Q² (Cross-Validation) | Standard Error of Estimate (SEE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-QSAR (Linear) | Heuristic Method (HM) | 0.6682 | 0.5669 | - |

| 2D-QSAR (Non-Linear) | Gene Expression Programming (GEP) | 0.79 | 0.76 | - |

| 3D-QSAR | CoMSIA | 0.928 | 0.628 | 0.160 |

The data demonstrates a clear performance hierarchy. The 3D-QSAR (CoMSIA) model achieved a superior fit for the training data, as indicated by the highest R² value (0.928), signifying it explains over 92% of the variance in biological activity. It also exhibited a strong cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²=0.628) and a low standard error of estimate [8]. The study authors concluded that "the 3D paradigm evinced an exemplary fit," outperforming the non-linear 2D model, while the linear 2D model showed suboptimal efficacy [8].

Performance in Other Oncological Targets

Evidence from other cancer types reinforces this trend. A study on EGFR inhibitors found that a 2D-QSAR model using SVM excelled in binary classification (predicting inhibitor vs. non-inhibitor) with an accuracy exceeding 97% [19]. However, for predicting the continuous value of inhibitory activity (IC50), the 3D-QSAR (Topomer CoMFA) model provided a high non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (r² = 0.888), demonstrating its strength in quantifying potency [19]. This highlights a key differentiator: 2D-QSAR can be highly effective for classification tasks, while 3D-QSAR often excels at predicting precise activity levels, which is critical for lead optimization.

Conversely, a study on histamine H3 receptor antagonists found that 2D methods (MLR and ANN) performed equally well or even better than the 3D-HASL method in predicting receptor binding affinities [18]. This indicates that the superiority of either approach can be context-dependent, influenced by the specific target and chemical series under investigation.

Experimental Protocols for QSAR Model Construction

The construction of robust QSAR models follows a systematic workflow. The general process and methodological differences between 2D and 3D approaches are outlined below.

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

Step 1: Dataset Curation and Preparation A series of compounds with known biological activities (e.g., IC50 or Ki values) is collected. For the dihydropteridone study, 34 compounds were used [8]. The dataset is typically partitioned into a training set (~75-80%) for model building and a test set (~20-25%) for external validation [8] [19].

Step 2: Molecular Structure Optimization and Alignment

- 2D-QSAR: Molecular structures are sketched and energetically minimized using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., MM+). Further optimization may employ semi-empirical methods (AM1 or PM3) [8].

- 3D-QSAR: This critical additional step involves superimposing (aligning) all molecules based on a common scaffold or pharmacophore. The most active molecule is often used as a template for alignment [20].

Step 3: Descriptor Calculation and Field Generation

- 2D-QSAR: Software like CODESSA or DRAGON calculates thousands of molecular descriptors encompassing constitutional, topological, geometrical, and quantum-chemical features [8] [17]. Feature selection algorithms (e.g., CfsSubsetEval with Greedy Stepwise) are then used to identify the most relevant descriptors and avoid overfitting [19].

- 3D-QSAR: Programs like SYBYL compute steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies at thousands of grid points surrounding the aligned molecules. CoMSIA can additionally calculate hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding fields [20].

Step 4: Model Construction and Validation

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is the standard algorithm for 3D-QSAR due to the high collinearity of field descriptors [8] [20]. For 2D-QSAR, PLS, MLR, and machine learning methods like SVM are common [19].

- Models are rigorously validated. Key metrics include:

- R²: Coefficient of determination for the training set.

- Q² (or q²): Cross-validated correlation coefficient (e.g., from Leave-One-Out), assessing predictive reliability. A Q² > 0.5 is generally considered acceptable [19].

- External Validation: Predictive power on the independent test set, confirming model robustness [10].

Application in Glioblastoma Research: A Case Study

The integrated application of 2D and 3D-QSAR is powerfully illustrated in the discovery of novel dihydropteridone derivatives for glioblastoma.

The study began by developing both 2D and 3D models, confirming the higher statistical performance of the 3D-CoMSIA model [8]. The 2D model identified the most significant molecular descriptor as "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN), providing an initial structural insight. However, the 3D-CoMSIA model generated visual contour maps that graphically illustrated regions around the molecular scaffold where specific chemical modifications would enhance or diminish activity [8].

By combining the quantitative descriptor from the 2D model with the qualitative, spatial guidance from the 3D contour maps, the researchers designed 200 novel compounds in silico. They predicted their activity and selected the most promising candidate, compound 21E.153, for synthesis and experimental testing. This compound demonstrated outstanding antitumor properties and strong binding affinity in molecular docking studies, validating the synergistic power of the combined QSAR approach [8].

This workflow, integrating the broader screening capability of 2D-QSAR with the precise optimization guidance of 3D-QSAR, is a hallmark of modern computer-aided drug design for challenging oncology targets [10] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Tools for QSAR Modeling in Oncology Drug Discovery

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in QSAR | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CODESSA | Software | Calculates a wide range of 2D molecular descriptors [8]. | Essential for generating input variables for 2D-QSAR models. |

| SYBYL | Software Suite | Provides a environment for molecular modeling, alignment, and performing 3D-QSAR (CoMFA, CoMSIA) [20] [19]. | Industry-standard platform for constructing and visualizing 3D-QSAR models. |

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints; used for data preprocessing and model building, often within KNIME [10] [17]. | A versatile and accessible tool for descriptor calculation and integration into data pipelines. |

| KNIME / scikit-learn | Data Analytics Platform / ML Library | Provides workflows (KNIME) and algorithms (scikit-learn) for data preparation, feature selection, and machine learning model construction [10] [17]. | Crucial for building, validating, and deploying modern 2D-QSAR models using ML algorithms. |

The empirical evidence from oncology drug discovery clearly indicates that 3D-QSAR methodologies often provide a more accurate and visually interpretable model for optimizing compound potency, as demonstrated by superior R² and Q² values in direct comparisons [8]. However, 2D-QSAR remains a highly valuable, computationally efficient approach for rapid virtual screening of large compound libraries and for classification tasks [18] [19].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the following strategic recommendations are proposed:

- Use 2D-QSAR for: Initial screening of large virtual libraries, identifying key physicochemical properties governing activity, and classification problems (e.g., active/inactive prediction).

- Use 3D-QSAR for: Lead optimization stages where understanding the spatial requirements of the target binding site is crucial, and for generating visual guides for medicinal chemists.

- Adopt an Integrated Approach: The most effective strategy leverages the strengths of both. Use 2D-QSAR to narrow the field of candidates and then apply 3D-QSAR to refine and optimize the most promising leads, as exemplified in the glioblastoma case study [8].

Ultimately, the choice between 2D and 3D-QSAR is not a binary one. A synergistic workflow that integrates both approaches, alongside other computational techniques like molecular docking and ADMET prediction, creates a powerful engine for driving innovation in oncology therapeutics, offering new hope for treating devastating diseases like glioblastoma [10] [22].

Implementing QSAR Models: Step-by-Step Methods for Glioblastoma Compound Analysis

Data Collection and Preprocessing for 2D and 3D-QSAR Studies

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a fundamental methodology in modern computational drug discovery, establishing mathematical relationships between chemical structures and their biological activities. In the challenging field of glioblastoma (GBM) research, where therapeutic options remain limited, QSAR approaches provide valuable tools for rational drug design. GBM, as the most aggressive and treatment-resistant variant of brain tumors, presents formidable therapeutic challenges due to its high complexity, protective blood-brain barrier, and rapid progression dynamics [22]. The resistance of GBM to conventional treatments stems from its internal subpopulations of stem cells and highly mutated genome, complicating treatment strategies and creating an urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches [5].

QSAR methodologies have evolved significantly from classical approaches to modern artificial intelligence-integrated frameworks, offering powerful means to accelerate the discovery of potential GBM therapeutics. These computational approaches significantly accelerate the preclinical stage of drug discovery by reducing costs, minimizing attrition, and expediting the identification of viable candidates [17]. For glioblastoma research specifically, QSAR models have been successfully applied to various promising targets, including Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibitors like dihydropteridone derivatives and Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) inhibitors, both representing innovative strategies in GBM treatment [4] [5]. This guide systematically compares the data collection and preprocessing requirements for 2D and 3D-QSAR studies, providing researchers with practical protocols and experimental frameworks tailored to glioblastoma compound research.

Fundamental QSAR Concepts and Definitions

At its core, QSAR is defined as a methodology to associate the chemical structure of a molecule with its biochemical, physical, pharmaceutical, or biological effects [23]. The fundamental equation can be summarized as: Biological activity = f(physicochemical parameters) [23]. This mathematical framework enables researchers to predict compound behavior without extensive laboratory experimentation, creating significant efficiencies in the drug discovery pipeline.

QSAR techniques are systematically classified based on the dimensionality of molecular descriptors used in model construction. Two-dimensional (2D) QSAR focuses on molecular descriptors derived from the compound's topological structure without considering spatial orientation, while three-dimensional (3D) QSAR incorporates the molecule's spatial configuration and interaction potentials into the modeling approach [24]. The progression from 2D to 3D-QSAR represents an evolution from considering molecules as flat structural diagrams to treating them as three-dimensional objects with specific shapes and interaction fields [14].

The motivation behind developing QSAR models in glioblastoma research encompasses several critical objectives: predicting biological activity of novel compounds, rationalizing mechanisms of action within chemical series, reducing compound development expenses, minimizing animal testing requirements, and advancing greener chemistry approaches by eliminating unlikely leads early in the discovery process [23]. For GBM specifically, where blood-brain barrier penetration represents a critical additional hurdle, QSAR models can incorporate parameters predicting this crucial property alongside anti-tumor efficacy [22].

Data Collection Protocols for QSAR Modeling

Compound Selection and Activity Data Acquisition

The foundation of any robust QSAR model lies in the quality and relevance of the underlying dataset. For glioblastoma-focused studies, researchers typically assemble compounds with experimentally determined activity values against specific GBM-related targets or cell lines. The integrity of this dataset is paramount, requiring selection of molecules that are structurally related to ensure coherent modeling, yet sufficiently diverse to capture meaningful structure-activity relationships [14]. All activity data must be acquired under uniform experimental conditions, as variability in assay protocols introduces unwanted noise and systemic bias that compromises predictive value [14].

Specific protocols for GBM-targeted datasets have been demonstrated in recent studies. For FAK inhibitors targeting glioblastoma, researchers retrieved molecular structures and corresponding inhibitory activity (expressed as half-maximal inhibitory concentration IC50) from the CHEMBL database (CHEMBL2695), initially comprising 4730 entries [5]. The base-10 logarithm of IC50 (represented as -logIC50, denoted as pIC50) typically serves as the dependent variable rather than raw IC50 values. For compounds displaying varying IC50 values within a narrow range (10 μM), the average is calculated as the final IC50 value to ensure data consistency [5]. Similarly, for PLK1 inhibitors like dihydropteridone derivatives, studies have obtained structures and corresponding activity values from published research, with one study utilizing 34 compounds for initial model development [4].

Table 1: Standardized Activity Data Format for QSAR Modeling

| Field Name | Data Type | Description | Example Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound ID | String | Unique identifier | CMPD-001 |

| SMILES | String | Structural representation | C1=CC(=CC=C1F) |

| IC50 (nM) | Numeric | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration | 125.0 |

| pIC50 | Numeric | -log10(IC50) | 6.90 |

| Target | String | Biological target | PLK1 kinase |

| Assay Type | String | Experimental method | Cell-based U87-MG |

| Reference | String | Data source | CHEMBL2695 |

Dataset Partitioning Strategies

To mitigate overfitting risks and ensure model generalizability, randomized partitioning of compounds is essential. Studies typically employ a ratio of approximately 1:3, allocating a smaller subset (e.g., 8 compounds from a set of 34) to the test set and the majority (e.g., 26 compounds) to the training set [4]. The training set serves to establish and refine the model, encompassing construction, calibration, and identification of key variables and algorithms. Meanwhile, the test set provides unbiased assessment without parameter modification, with decisions regarding algorithm adjustments or model retraining contingent upon evaluating the overall model fit [4].

For larger datasets, such as those comprising 1280 FAK inhibitors, researchers may implement more sophisticated splitting strategies, including an 80:20 ratio for training and independent test sets, with ten-fold cross-validation during model training to mitigate the impact of random data partitioning [5]. Optimization techniques such as hyperparameter tuning using grid search methodology further enhance model performance, with optimal parameters determined specifically for each algorithm employed [5].

Preprocessing Methodologies for 2D-QSAR

Molecular Structure Optimization and 2D Descriptor Calculation

The performance of 2D-QSAR models relies heavily on appropriate selection of molecular descriptors, necessitating careful structural optimization of investigated compounds. In standard protocols, the chemical structure is initially sketched using ChemDraw and subsequently optimized using HyperChem [4]. The optimization process typically employs molecular mechanics field (MM+) for initial optimization, followed by selection of the AM1 or PM3 model based on the presence or absence of S and P atoms. The structure is cyclically optimized using the Polak-Ribiere method until the root mean square gradient reaches a threshold of 0.01 [4].

Following structural optimization, computational programs like CODESSA calculate molecular descriptors encompassing quantum chemistry, structure, topology, geometry, and electrostatic properties [4]. These 2D descriptors include pure topological descriptors, connectivity indices, walk and path counts, information indices, and 2D-autocorrelations [24]. Alternatively, researchers may utilize PaDEL-Descriptor, an open source software capable of generating 1875 descriptors including 1D, 2D, and 3D types, along with 12 types of fingerprints [24]. Dragon represents another option, capable of generating more than 4000 descriptors for a single molecule, with a web-based version available for limited use [24].

Descriptor Selection and Linear Model Construction

In constructing linear 2D-QSAR models, the Heuristic Method (HM) is frequently employed to extract all molecular descriptors, followed by feature selection to determine the optimal number of descriptors that effectively represent chemical structure while excluding descriptors with minimal impact [4]. Objective measures, such as the F-test, R², R²CV, and t-test, evaluate correlation coefficients between parameters. Additional descriptors are iteratively added until further inclusion has negligible influence on results [4]. Through this procedure, linear models typically incorporate multiple descriptors, with studies identifying "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN) as particularly significant for dihydropteridone derivatives against GBM [4].

For nonlinear 2D-QSAR modeling, Gene Expression Programming (GEP) has emerged as a powerful technique rooted in programming and algorithms [4]. Unlike coding numbers or analyzing trees, GEP utilizes linear chromosomes as candidates, with coding of constant-length linear symbols and derivation of individual phenotypes similar to coding codes and expression trees [4]. The candidate chromosomes are generated from the feature set and the end set, then encoded into an expression tree (ET) format to calculate the equation, with fitness functions applied to a random number of chromosomes until termination conditions are met [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of 2D-QSAR Modeling Approaches for Glioblastoma Compounds

| Model Type | Statistical Metric | Performance Value | Dataset Characteristics | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heuristic Method (Linear) | R² | 0.6682 | 34 dihydropteridone derivatives | PLK1 inhibitors [4] |

| R²cv | 0.5669 | |||

| Residual sum of squares (S²) | 0.0199 | |||

| Gene Expression Programming (Nonlinear) | Training set R² | 0.79 | 34 dihydropteridone derivatives | PLK1 inhibitors [4] |

| Validation set R² | 0.76 | |||

| LightGBM (Machine Learning) | R² | 0.892 | 1280 FAK inhibitors | FAK inhibitors for GBM [5] |

| MAE | 0.331 | |||

| RMSE | 0.467 |

Preprocessing Methodologies for 3D-QSAR

Molecular Modeling and Conformational Analysis

Three-dimensional QSAR begins with generating 3D molecular structures by converting 2D representations into three-dimensional coordinates using cheminformatics tools like RDKit or Sybyl [14]. These initial 3D structures undergo geometry optimization using molecular mechanics such as the universal force field (UFF) or, for higher accuracy, quantum mechanical methods [14]. Optimization ensures each molecule adopts a realistic, low-energy conformation, which critically influences subsequent alignment and descriptor calculation steps.

The selected conformation must reflect the putative bioactive orientation, with prioritization of structural accuracy at this stage being essential for model quality. Since small molecules often exhibit conformational flexibility, some advanced 3D-QSAR approaches incorporate multiple low-energy conformations to account for this variability, though this increases computational complexity significantly [24]. For glioblastoma-targeted compounds, particular attention must be paid to conformations that potentially facilitate blood-brain barrier penetration alongside target binding.

Molecular Alignment Techniques

Molecular alignment constitutes one of the most critical and technically demanding steps in 3D-QSAR, with the objective of superimposing all molecules within a shared 3D reference frame that reflects their putative bioactive conformations [14]. This alignment assumes that all compounds share a similar binding mode and can be accomplished through manual approaches or algorithmic methods.

Common alignment strategies include Bemis-Murcko scaffolding, which derives scaffolds by removing side chains and retaining only ring systems and linkers, and maximum common substructure (MCS), which identifies the largest shared substructure among a set of molecules [14]. Tools like RDKit's AllChem.ConstrainedEmbed() can generate 3D conformations that match scaffold atoms to a reference, ensuring accurate alignment. A poor alignment undermines the entire modeling process by introducing inconsistencies in descriptor calculations, which is why some modern methods aim to bypass alignment altogether, though traditional approaches such as Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) remain alignment-dependent [14].

Diagram 1: 3D-QSAR Preprocessing Workflow. This workflow illustrates the sequential steps in 3D-QSAR preprocessing, from initial 2D structures through model building and prediction.

3D Molecular Descriptor Computation

Following alignment, researchers compute 3D molecular descriptors that numerically represent steric and electrostatic environments of each molecule. The classic Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) method uses a lattice of grid points surrounding the molecules, where a probe atom measures interaction energies at each point - typically steric (van der Waals) and electrostatic (Coulomb) interaction energies [14]. This approach essentially maps how a tiny test probe "feels" the presence of the molecule at various locations, detecting bulky groups or attractive positive charges [14]. The collection of all field values forms a fingerprint-like descriptor for the molecule's 3D shape and electrostatic profile.

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extends this approach by using Gaussian-type functions to evaluate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields, which smooth out abrupt field changes and enhance interpretability, especially across structurally diverse compounds [14]. While CoMFA is highly sensitive to alignment quality, requiring precise spatial congruence across molecules, CoMSIA offers more tolerance to minor misalignments, thereby expanding applicability to datasets with broader chemical diversity [14].

Model Building and Validation in 3D-QSAR

With 3D descriptors calculated for a series of molecules and their known biological activities, the next step establishes a mathematical relationship linking 3D descriptor values to biological activity. Statistical regression techniques like partial least squares (PLS) regression are standard in CoMFA and many 3D-QSAR studies, as PLS can handle the large number of highly correlated descriptors by projecting them to a smaller set of latent variables [14]. The outcome is a mathematical model capable of predicting biological activity from 3D field data.

Model validation represents a crucial step, typically employing cross-validation techniques such as leave-one-out (LOO), where each compound is sequentially excluded from the training set and predicted by a model built from the remaining data [14]. Researchers quantify model performance using statistical metrics: Q² for cross-validated predictivity and R² for goodness-of-fit. A robust model should exhibit high values for both metrics, indicating capture of meaningful biological trends without overfitting. For glioblastoma-focused 3D-QSAR, exemplary models have demonstrated exemplary fit with formidable Q² (0.628) and R² (0.928) values, complemented by impressive F-value (12.194) and minimized standard error of estimate (SEE) at 0.160 [4].

Table 3: Performance Metrics for 3D-QSAR Models in Glioblastoma Research

| Model Type | Statistical Metric | Performance Value | Dataset | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | Q² | 0.528 | 22 FAK inhibitors | Steric/electrostatic field analysis [5] |

| R²pred | 0.7557 | |||

| CoMSIA | Q² | 0.757 | 22 FAK inhibitors | Additional hydrophobic/H-bond fields [5] |

| R²pred | 0.8362 | |||

| Advanced 3D-QSAR | Q² | 0.628 | 34 dihydropteridone derivatives | Excellent fit statistics [4] |

| R² | 0.928 | |||

| F-value | 12.194 | |||

| SEE | 0.160 |

Comparative Performance Analysis for Glioblastoma Applications

Predictive Accuracy and Model Robustness

Direct comparison of 2D and 3D-QSAR approaches reveals distinct performance characteristics relevant to glioblastoma drug discovery. Empirical modeling outcomes consistently underscore the preeminence of 3D-QSAR models, followed by nonlinear 2D models, while linear 2D approaches often manifest suboptimal efficacy [4]. Specifically, for dihydropteridone derivatives targeting PLK1 in GBM, the 3D-QSAR paradigm demonstrated exemplary fit characterized by formidable Q² (0.628) and R² (0.928) values, complemented by an impressive F-value (12.194) and minimized standard error of estimate (SEE) at 0.160 [4]. In contrast, the heuristic 2D linear model achieved an R² of 0.6682 with R²cv of 0.5669, while the GEP nonlinear 2D model showed improved performance with coefficients of determination for training and validation sets at 0.79 and 0.76, respectively [4].

For FAK inhibitors targeting glioblastoma, machine learning-enhanced 2D approaches have demonstrated strong predictive capability, with models based on 1280 FAK inhibitors achieving R² of 0.892, MAE of 0.331, and RMSE of 0.467 using combined CDK, CDK extended fingerprints, and substructure fingerprint counts [5]. Another model based on IC50 data from 2608 compounds tested on U87-MG cells achieved an R² of 0.789, MAE of 0.395, and RMSE of 0.536 [5]. These results suggest that while 3D-QSAR generally offers superior performance for congeneric series, advanced 2D approaches with large datasets can achieve competitive predictive accuracy.

Interpretability and Design Guidance

A critical distinction between 2D and 3D-QSAR lies in their interpretability and capacity to guide molecular design. 3D-QSAR models excel in providing visual guidance through contour maps that identify spatial regions where specific molecular features enhance or diminish activity [14]. For example, steric contour maps show where adding bulky groups is favorable (green regions) or should be avoided (yellow regions), while electrostatic maps indicate regions that benefit from electronegative (red) or electropositive (blue) groups [14]. These visual cues directly inform rational chemical modifications by highlighting structural regions amenable to optimization.

In contrast, 2D-QSAR models identify significant molecular descriptors that influence activity but provide less direct spatial guidance for molecular design. The most significant molecular descriptors in 2D models, such as "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN) identified for dihydropteridone derivatives, offer important insights into electronic properties affecting activity but lack the three-dimensional context of contour maps [4]. However, by combining key 2D descriptors with hydrophobic field information, researchers can generate valuable suggestions for novel drug design, as demonstrated by the identification of compound 21E.153, a novel dihydropteridone derivative with outstanding antitumor properties and docking capabilities [4].

Diagram 2: QSAR Approach Selection Guide. This decision diagram illustrates key factors influencing the choice between 2D and 3D-QSAR approaches for glioblastoma compound research.

Software Solutions for QSAR Modeling

The successful implementation of QSAR studies requires specialized software tools for descriptor calculation, model building, and validation. Multiple commercial and open-source options exist, each with particular strengths for glioblastoma research applications. For 2D-QSAR, PaDEL-Descriptor represents a popular open-source choice, capable of generating 1875 descriptors including 1D, 2D, and 3D types alongside 12 fingerprint types [24]. Dragon offers even more extensive descriptor calculation, generating over 4000 descriptors for a single molecule, with a freely available web-based version for limited use [24].

For 3D-QSAR studies, specialized software includes Pentacle from Molecular Discovery, which implements the GRIND approach, and Schrodinger's AutoQSAR for automated 3D-QSAR modeling [24]. Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) remain cornerstone methodologies, available in commercial packages like Sybyl and open-source alternatives [24] [14]. Workflow automation tools such as Taverna, Pipeline Pilot, Galaxy, and KNIME provide platforms for developing complete QSAR workflows, integrating data retrieval, descriptor calculation, model building, and validation into streamlined processes [24].

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for QSAR Studies in Glioblastoma Research

| Software Tool | License Type | Primary Function | Application in GBM Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Free | Molecular descriptor calculation | Generate 2D descriptors for blood-brain barrier penetration prediction |

| Dragon | Commercial/Free limited | Molecular descriptor calculation | Comprehensive descriptor calculation for machine learning QSAR |

| AutoQSAR | Commercial | Automated 3D-QSAR model creation | Rapid screening of GBM compound libraries |

| CODESSA | Commercial | QSAR modeling and descriptor calculation | Heuristic method implementation for PLK1 inhibitors |

| KNIME | Free | Workflow automation | Building complete QSAR pipelines for FAK inhibitors |

| RDKit | Free | Cheminformatics and 3D alignment | Molecular conformation generation and scaffold-based alignment |

| QSARpro | Commercial | QSAR modeling and activity prediction | Toxicity prediction for GBM drug candidates |

Experimental Protocols for Specific GBM Targets

For researchers targeting specific glioblastoma pathways, tailored QSAR protocols have demonstrated particular success. For PLK1 inhibitors like dihydropteridone derivatives, studies have established optimized protocols involving the Heuristic Method for linear 2D-QSAR with six descriptors, GEP for nonlinear modeling, and CoMSIA for 3D-QSAR with integrated electrostatic, steric, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields [4]. The most significant molecular descriptor identified (MECN - Min exchange energy for a C-N bond) combined with hydrophobic field information provides specific design guidance for novel compounds [4].

For FAK inhibitors targeting glioblastoma, machine learning-enhanced protocols utilizing LightGBM, Random Forest, and XGBoost algorithms with molecular fingerprints have proven effective for large-scale virtual screening [5]. These approaches leverage extensive datasets (1280+ compounds) from CHEMBL, employing CDK fingerprints, CDK extended fingerprints, substructure fingerprints, and substructure fingerprint counts as molecular descriptors [5]. Subsequent ADMET analysis and molecular dynamics simulations further refine candidate selection, providing a comprehensive framework for FAK inhibitor development specific to GBM therapeutic needs [5].

The comparative analysis of data collection and preprocessing methodologies for 2D and 3D-QSAR studies reveals a complementary relationship between these approaches in glioblastoma drug discovery. While 3D-QSAR generally offers superior predictive accuracy and provides visual guidance through contour maps, it demands careful conformational analysis and alignment, making it particularly suitable for congeneric series with established binding modes. Conversely, 2D-QSAR approaches, especially when enhanced with machine learning algorithms, demonstrate robust performance with large, diverse datasets and offer implementation advantages through simpler preprocessing requirements.

For glioblastoma researchers, the selection between 2D and 3D-QSAR should be guided by specific research contexts: dataset characteristics, computational resources, target knowledge, and desired output. The integration of both approaches, leveraging 2D-QSAR for initial large-scale screening and 3D-QSAR for detailed optimization of promising leads, represents a powerful strategy for advancing GBM therapeutics. Furthermore, the emerging integration of AI methodologies with both 2D and 3D-QSAR promises enhanced predictive capability and efficiency, potentially accelerating the development of critically needed novel treatments for this challenging disease. As QSAR methodologies continue evolving, their application in glioblastoma research will undoubtedly expand, offering increasingly sophisticated tools for addressing one of oncology's most formidable challenges.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of computer-aided drug design, enabling researchers to predict the biological activity of compounds through mathematical relationships derived from their chemical structures. In the context of glioblastoma research—an area with urgent unmet therapeutic needs—QSAR methodologies provide valuable tools for accelerating the identification of novel chemotherapeutic agents. While 3D-QSAR approaches offer insights into spatial molecular interactions, 2D-QSAR remains widely utilized for its computational efficiency, interpretability, and effectiveness, particularly in early-stage drug discovery campaigns [8] [25]. The robustness of a 2D-QSAR model hinges critically on two fundamental components: the judicious selection of molecular descriptors that encode crucial structural information, and the implementation of appropriate algorithms that can accurately capture the relationship between these descriptors and biological activity [26] [25].

The evolution of QSAR from classical statistical methods to modern machine learning-based approaches has significantly expanded its predictive capabilities. Traditional methods like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) remain valued for their interpretability, while contemporary machine learning algorithms can capture complex, non-linear relationships in high-dimensional chemical data [26] [18]. This comparative guide examines the construction of robust 2D-QSAR models, with particular emphasis on descriptor selection strategies and algorithm implementation, while objectively evaluating its performance relative to 3D-QSAR approaches in the context of glioblastoma therapeutic development.

Theoretical Foundations of 2D-QSAR

Molecular Descriptors: Encoding Chemical Information

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations of a compound's structural and physicochemical properties that serve as the independent variables in QSAR models. These descriptors are broadly classified based on the dimensions of chemical information they encode. 1D descriptors represent bulk properties like molecular weight and atom count; 2D descriptors capture topological features derived from molecular connectivity; while 3D descriptors quantify spatial characteristics such as shape and electrostatic potential [26]. For 2D-QSAR, topological descriptors are particularly relevant as they can be calculated directly from molecular structure without requiring conformational analysis or alignment [25].

The appropriate selection and interpretation of these descriptors is paramount for developing predictive, robust QSAR models. As noted in studies of dihydropteridone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors for glioblastoma, the most significant molecular descriptor in a 2D model was identified as "Min exchange energy for a C-N bond" (MECN), which contributed substantially to predicting anticancer activity [8]. Modern descriptor calculation tools like PaDEL software, DRAGON, and RDKit can generate thousands of molecular descriptors encompassing quantum chemical, structural, topological, geometry, and electrostatic properties [26] [5]. To mitigate overfitting and enhance model interpretability, dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), and LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) are routinely employed to identify the most relevant descriptor subsets [26].

Algorithm Selection: From Classical Statistics to Machine Learning